The United States has a long and well-documented history of genocide against Native Peoples. Central to this violence was the forced removal of Native children to federal Indian boarding schools and the use of assimilationist land policies to fracture the kinship networks essential to Indigenous family life (

Adams 1995;

Bussey and Lucero 2013;

Crofoot and Harris 2012;

Rocha Beardall 2016). The effects of these policies are still felt today. Native children continue to be overrepresented at every stage of the child welfare system, from initial reporting and investigation to foster care placement and the termination of parental rights (

Cross 2021;

Edwards et al. 2023;

Grinnell Davis et al. 2022;

Rocha Beardall and Edwards 2021;

Sinha et al. 2021). In response, Native nations have continuously asserted their sovereign right to protect the integrity of their families through legal advocacy, caregiving practices, and community-driven systems of support.

Yet, dominant narratives continue to frame Indian child welfare as a crisis to be managed through state intervention. These frameworks obscure Indigenous governance and reduce survivance to reactive struggle, sidelining the proactive ways Native nations assert authority over family and community life. This article takes a different approach by asking: What becomes possible when we understand Indigenous child welfare as a space where law, care, and collective belonging are continuously redefined on Indigenous terms?

Building on Indigenous Studies and postcolonial theory, I introduce the concept of the Third Space of Indian child welfare to theorize how Indigenous Peoples navigate, contest, and transform the legal, political, and cultural terrain of child welfare. The Third Space foregrounds Indigenous governance as a dual practice that rejects colonial domination while cultivating community-rooted systems of care and accountability. It captures how Native nations simultaneously engage settler structures to assert jurisdiction and revitalize kinship-based practices of belonging. Rather than framing Indigenous child welfare as a crisis of deficiency, I analyze this space as a dynamic field of sovereign governance in motion (

Bussey and Lucero 2013;

California Courts 2025;

Cross and Fox 2014).

Specifically, I examine three (of many) interrelated processes that give form to the Third Space and challenge settler assumptions about kinship and belonging. First, Strategic Legal Engagement involves Native nations asserting jurisdiction through tribal family codes, court systems, and advocacy within the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (ICWA). Tribes intervene in state custody cases and defend sovereignty in federal court to protect Native children and families. Second, Kinship-Based Care prioritizes extended family networks and customary caregiving practices that foster cultural connection and collective responsibility. Programs supporting kin-first placement, community caregiving, and intergenerational mentoring keep children rooted in language, ceremony, and community life. Third, Tribally Controlled Family Collectives embed Indigenous knowledge, legal traditions, and relational accountability into everyday care infrastructures. This work manifests through family preservation initiatives, wraparound services, and tribal customary adoption practices that strengthen family well-being.

In addition to fostering robust Indigenous sovereignty, the Third Space reflects abolitionist principles by dismantling carceral logics of family separation and advancing community-rooted alternatives. For instance, strategic legal engagement disrupts assimilationist frameworks and asserts tribal governance, while kinship-based caregiving fosters relational care over punitive intervention. Throughout, tribally governed collectives envision new forms of justice by embedding Indigenous law into institutional practice. Framing these efforts within the Third Space positions Indigenous governance as both resistance and abolitionist worldbuilding.

The Third Space of Indian child welfare is not unique to the United States and can be found across the globe. Diverse Indigenous nations are creating care-based systems that challenge settler-colonial child welfare regimes and advance relational jurisdiction. From tribally administered family healing courts in North America to customary caregiving practices in Aotearoa and Indigenous-led social work in Australia (

Libesman 2014;

Majumdar et al. 2023), these movements exemplify a global Indigenous politics of care. From an abolitionist perspective, they also offer living alternatives to the logics of separation, surveillance, and punitive intervention.

This article unfolds in four parts. First, I situate U.S. child welfare within a longer history of settler colonialism, tracing how boarding schools and assimilationist policies intentionally fractured Indigenous kinship systems. Second, I engage Indigenous Studies to theorize the Third Space as a site of legal, cultural, and political formation. Third, I examine how these values are institutionalized through ICWA, a landmark site of Indigenous legal resistance and worldbuilding. Finally, I analyze contemporary legal challenges to ICWA as part of an ongoing settler-colonial backlash against Native sovereignty and abolitionist care. These sections advance a framework for understanding Indigenous child welfare as a dynamic field of sovereign governance and legal innovation rooted in relationality.

1. The Settler Colonial Roots of Native Family Separation

Understanding Indigenous movements for family justice requires a clear examination of settler colonialism’s foundational role in shaping U.S. systems of domination and Indigenous resistance. Settler colonialism refers to the ongoing occupation of Indigenous lands by Euro-American settlers for the seizure and commodification of resources for profit (

Rocha Beardall 2022;

Wolfe 2006). Central to this project was a “logic of elimination” that sought to displace, erase, and replace Indigenous Peoples through land theft and family separation (

Wolfe 2006).

Indigenous lands were taken using a variety of tactics, including physical violence, manipulation, bribery, and corruption (

Wilkinson and Biggs 1977). Settlers solidified their dispossession by creating institutions that concentrated financial, social, legal, and political power in the hands of settlers and their descendants. To legitimize their claims, settlers relied on the Doctrine of Discovery, which portrayed Native Peoples as “savages” and Europeans as uniquely “civilized” and entitled to govern Indigenous lands (

Mills 1997;

Rocha Beardall 2022). This legal fiction became the foundation for U.S. policies that dismantled Indigenous land ownership by reducing Indigenous rights to temporary use and occupancy. It also facilitated the forced relocation of Indigenous Peoples to reservations, often through treaties imposed under coercive conditions (

Nichols 2014).

Federal policies like the Indian Removal

Act (

1830) and the General Allotment Act of 1887 expanded Native displacement. These laws privatized Indigenous lands and opened “surplus” lands to settlers, resulting in the loss of 90 million acres between 1887 and 1934 (

U.S. Department of the Interior, Indian Affairs 2025). By the end, nearly 2.4 billion acres of land—93.9% of Indigenous homelands—had been stolen (

Farrell et al. 2021). This systematic land theft is directly tied to the state’s intentional erosion of tribal sovereignty as the loss of land disrupted the sociocultural relationships essential to maintaining Indigenous ways of life. Nowhere was this more evident than in the case of Indian boarding schools.

1.1. Indian Boarding Schools

The boarding school system targeted Indigenous kinship networks and communal practices of caregiving to sever intergenerational ties, disrupt the tribal stewardship of children, and refuse communal land stewardship in a symbiotic and cyclical process (

Rocha Beardall 2016). As a result, systematic efforts to dismantle Native Peoples’ physical connection to their homelands laid the groundwork for a broader campaign of cultural genocide (

Adams 1995;

Rocha Beardall 2016) by targeting the very foundation of Indigenous life: Native children (

Trennert 1988).

The dual goal was to subordinate Natives individually and collectively as nations. Specifically, boarding schools helped to “decrease the military threat of American Indian nations” (

Crofoot and Harris 2012, p. 1668) under the belief that an assimilated Native person would be less threatening to settler society than one who maintained their cultural ties. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Thomas Morgan applauded this assimilationist agenda, announcing proudly that “the Indians are not only becoming Americanized, but they are…gradually being absorbed, losing their identity as Indians, and becoming an indistinguishable part of the great body politic” (

Jacobs 2004, p. 33).

The

Indian Civilization Act (

1819) provided a legal framework for this campaign, forcibly removing Native children from their families to indoctrinate them with Christian values (

Cross 1999;

DeJong 1993). However, assimilationists understood that to fully integrate Native Peoples into settler society, strictly policing Native children would not be enough, and “the cohesiveness of the Indian family would need to be destroyed” (

Graham 2008, p. 52). Christian missions played a central role in this process, supported by federal funds and framed as a moral imperative to civilize those deemed “savage” and without salvation. The economic and human cost of this endeavor was enormous, yet considered necessary to eliminate fears about Native dependency on government resources. By 1926, over a century after the Indian Civilization Act was passed, this effort had grown so expansive that an estimated four out of five school-age Native children were enrolled in boarding schools (

Adams 1995).

Boarding schools were a traumatic experience for many of the students who survived them. These institutions prioritized labor over critical thinking, often reducing children to a skilled and semi-skilled workforce tasked with maintaining their schools by sewing uniforms, performing agricultural labor, or working in white households for little or no pay (

Adams 1995;

Trennert 1983;

Jacobs 2004). In addition to extensive labor, schools often isolated children from their families and tried to strip children of their cultural teachings and identities. Schoolteachers prevented students from engaging in acts of Native culture, such as speaking their Native language or practicing their beliefs, such as wearing their hair long. The harsh living conditions of boarding schools exacerbated the harm. Tuberculosis epidemics and other illnesses swept through the overcrowded, unsanitary dormitories. Students also suffered malnutrition and military-style discipline (

Child 1998;

DeJong 2007). Native parents, alarmed by the conditions, increasingly resisted sending their children to these institutions. Tribal nations and families’ resistance to the boarding school system took many forms. For instance, after decades of clashing between Hopi and government officials, when it was made abundantly clear that the education of Hopi children would require their removal from families, some Hopis quietly refused to send their children to boarding schools. At the same time, nearby Diné parents hid their children to protect them from being forcibly taken to school (

Jacobs 2004).

Indian boarding schools and their legacy of intergenerational trauma and family separation are not unique to the U.S. Across Canada, and Australia, policies framed as child welfare reflected a global settler-colonial strategy to erode tribal sovereignty by severing kinship ties and assimilating Indigenous youth into settler society (

Bombay et al. 2014;

Engel et al. 2012;

Guenther and Fogarty 2020;

Woolford 2015). In Canada, the residential school system was explicitly designed to assimilate Native children into settler culture under the stated goal of “killing the Indian in the child” (

Bombay et al. 2014). While these schools were officially run by the state, churches often managed daily operations and prioritized religious indoctrination over education. In Australia, children from the Stolen Generation endured similar settler logics and were sent to boarding schools, foster placements, or adopted into white families (

Silburn et al. 2006).

In the U.S., public scrutiny of the boarding school system began in earnest with the publication of the

Meriam (

1928) Report, which exposed the dire poverty, poor health conditions, and substandard living environments endured by Native children (

Watras 2004). The report criticized the federal government’s outdated “conception of education…[and called] to end the backward, out-of-date, and inefficient approach that characterized Indian schools” (

Watras 2004, p. 84) in favor of modern reforms that embraced child development within the contexts of family and community. Among its recommendations was the establishment of more on-reservation day schools, a proposal that gained traction during President Hoover’s administration and expanded significantly under President Roosevelt, including the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (

Watras 2004). Sparking an era known as the Indian New Deal, legislation limited federal oversight and increased self-governance for Native nations (

Rocha Beardall and Escobar 2016). This policy shifted centralized Indian education efforts to day schools. By 1935,

$1.5 million had been allocated to build dozens of day schools in Diné Country, increasing their number from six to forty-five (

Jacobs 2004;

Watras 2004).

1.2. Federal Termination and Adoption

The federal government entered the Termination Era in the 1950s, reversing progressive reforms in favor of conservative policies aimed at assimilating Native children and families into mainstream American culture (

Burt 1986;

Watras 2004). Under Termination Era legislation, the U.S. federal government sought to terminate Native nations, dismantle federal recognition, and deny Native Peoples their rights established through treaties and other formal agreements (

House Resolution No. 108 1953). To aid the termination process, the U.S. formed urban relocation programs to encourage Native People to take up jobs in cities far away from their tribal communities under the belief that distance from their culture and homelands would hasten their assimilation into white culture.

In addition to relocating adults, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) was instrumental in separating Native children from their parents and families through the use of out-of-home care and adoption. In 1958, the BIA launched the Indian Adoption Project (IAP) with the explicit goal “to make Indian children desirable for adoption by white middle class families” (

Crofoot and Harris 2012, p. 1669). This practice was often achieved through coercion, with social workers pressuring Native mothers to relinquish their parental rights (

Jacobs 2014). In contrast to the Indian Boarding Schools, the IAP cost very little to the taxpayers, as the financial burden of assimilation was placed mainly on the children’s adoptive families (

Jacobs 2014).

The impact of these policies was devastating. A 1976 report from the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA) provided grim findings: upwards of 25 to 35% of all Native children were being placed in out-of-home care, and 85% of those children were placed in non-Native homes (

Rocha Beardall and Edwards 2021;

U.S. Congress, Senate, Select Committee on Indian Affairs 1977). These records underscore that family separation was, and remains, a core mechanism of U.S. settler colonialism, designed to dismantle Indigenous kinship systems and assert control over Native Peoples and their lands. Similar efforts seen in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand further demonstrate the impact that control over Indigenous child welfare has on Indigenous sovereignty (

Libesman 2014).

Contemporary statistical evidence underscores the depth of this violence. Approximately 15% of American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) children can expect to enter foster care before their 18th birthday, a rate far exceeding that of other racial and ethnic groups (

Wildeman and Emanuel 2014, p. 536). Native children are also 60% more likely than white children to experience foster care and 46% more likely to have their parents’ rights terminated (

Rocha Beardall and Edwards 2021, p. 555;

Wildeman et al. 2020). State-level data reveal further disparities. In Minnesota, for example, Native children are 8.3 times more likely to be removed from their families, and an estimated 44% will experience family separation by age 18 (

Rocha Beardall and Edwards 2021).

Historical trauma continues to affect Native families today, reinforcing cycles of family separation and disruption of kinship ties. Despite the violence, Native communities remain resilient. They are reclaiming and revitalizing their cultural identity and kinship systems to resist policies that separate them from their children and ensure just family futures within the Third Space of Indian child welfare.

2. Features and Foundations of the Third Space

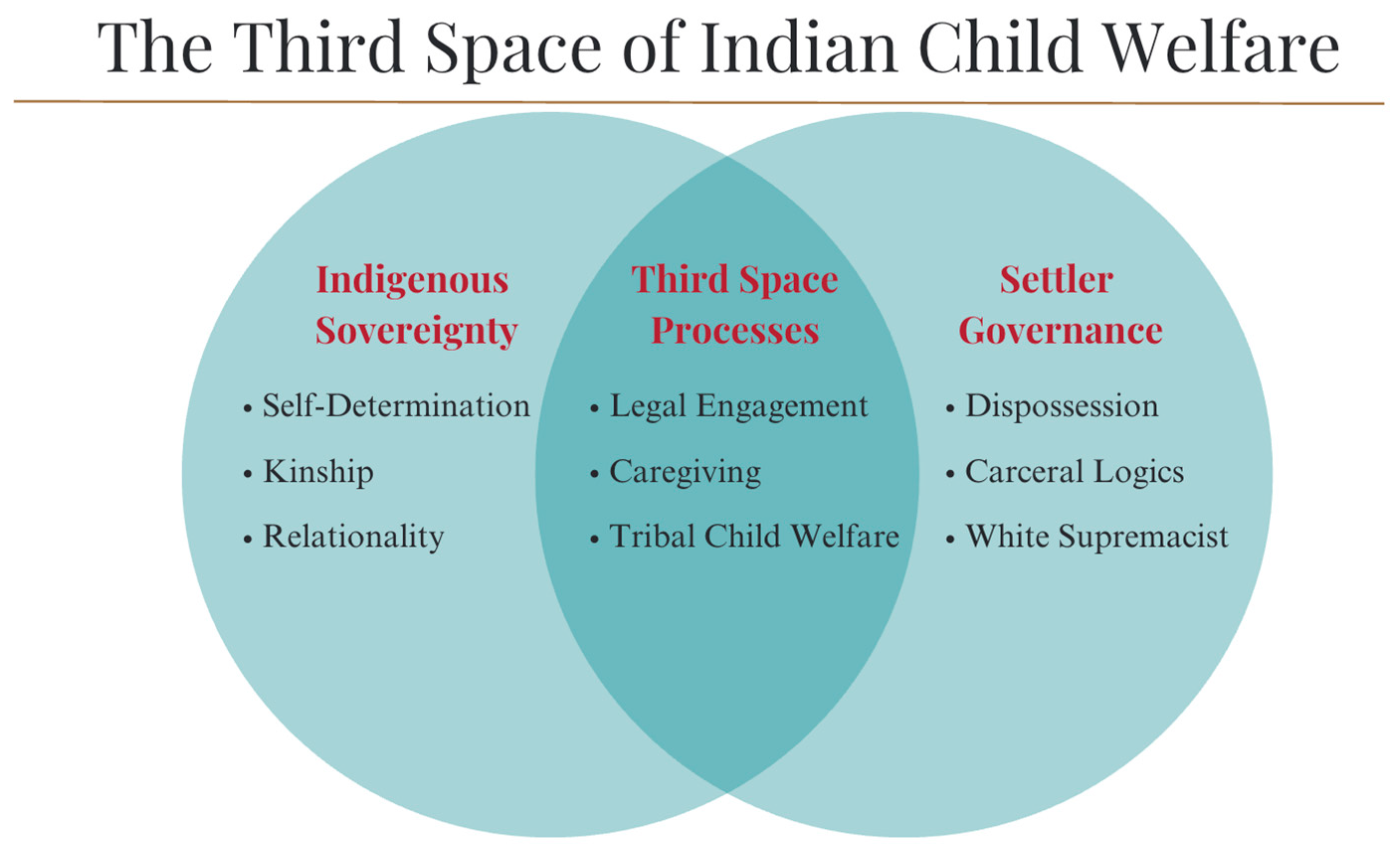

Indigenous child welfare governance unfolds in contested spaces where tribal nations confront settler colonial systems while advancing their own practices of care and belonging. This dynamic terrain is shaped by two overlapping but distinct domains: the Indigenous Sovereign Space and the Settler Governance Space (see

Figure 1). The Indigenous Sovereign Space reflects governance on Native terms, sustained through relational obligations, land-based practices, and cultural continuity. Through customary caregiving, language revitalization, and clan-based responsibility, Indigenous Peoples enact law and care independent of settler validation. Importantly, such kinship systems are cultivated both within and against structures designed to eliminate them.

In contrast, the Settler Governance Space imposes systems designed to surveil, assimilate, and fracture Indigenous families through foster care pipelines, termination proceedings, and punitive legal standards. Here, child welfare functions as a tool of colonial power, reframing cultural difference and structural inequality as individual and familial pathology.

At the intersection of Indigenous Sovereign Space and Settler Governance Space lies the Third Space of Indian Child Welfare: a site of active engagement and creative resistance where Indigenous nations engage settler systems to reclaim governance over family and community life. Rather than a compromise between the two, the Third Space is a generative field where tribal nations assert jurisdiction, redesign care infrastructures, and redefine the meaning of safety and belonging through sovereign practice. In this space, legal pluralism becomes lived experience, and the work of care is inseparable from the work of governance. Third Space interventions disrupt rather than reconcile settler norms and refuse imposed definitions of risk and fitness.

This framework builds on the work of Indigenous Studies scholars Kevin Bruyneel, Audra Simpson, and Sheryl Lightfoot, who examine how Native nations assert sovereignty across overlapping and contested terrains.

Bruyneel’s (

2007) theory of the “third space of sovereignty” describes how Indigenous claims-making refuses “to accommodate itself to the political choices framed by the imperial binary: assimilation or secession, inside or outside, modern or traditional” (p. 217). The false choices, he argues, obscure the complex ways Indigenous Peoples enact authority within and beyond settler-imposed boundaries. In the child welfare context, for instance, tribal nations often reject state-defined pathways of family intervention and opt to cultivate kinship systems grounded in responsibility and culture. When tribes intervene in state custody cases while simultaneously strengthening tribal courts and family codes, they enact this refusal of binary choices.

Building on Audra

Simpson’s (

2014) concept of nested sovereignty, the Third Space captures how Indigenous political orders endure and adapt within the structures of settler states without being subsumed by them. Nested sovereignty describes a layered governance arrangement where tribal nations simultaneously engage settler legal systems to assert jurisdiction or access resources while revitalizing internal kinship systems and governance protocols. The dual modes of engagement overlap and reinforce each other, enabling Indigenous nations to navigate state institutions on their own terms. In child welfare, this dual strategy allows tribes to defend their rights under federal laws like the ICWA while sustaining caregiving practices rooted in Indigenous epistemologies of family, responsibility, and relationality.

Sheryl

Lightfoot’s (

2016) work on Indigenous rights and self-determination expands this analysis by showing how Native nations assert sovereignty both within and beyond settler colonial legal systems. For instance, in Global Indigenous Politics: A Subtle Revolution, Lightfoot examines the dual nature of Indigenous political movements, arguing that they simultaneously operate within the existing international order while also transforming them, acting as a “norm vector” that shifts global expectations (

Lightfoot 2016, p. 8). Her analysis of the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) underscores a pivotal shift in global politics from individual rights to collective, relational, and sustainable interconnected Indigenous cultures. This mirrors the logic of the Third Space, where Native child welfare efforts cultivate interdependent family systems, cultural practices, and tribal sovereignty and become global norm-challenging acts of Indigenous self-determination beyond settler structures.

Together, these frameworks provide the foundation for the Third Space of Indian child welfare as a relational, legal, and political terrain where Indigenous nations engage settler systems without being defined by them. While Bruyneel names the ambivalence of state recognition, and Simpson insists on the sovereignty embedded in Indigenous practices, this article builds on both to theorize the Third Space as a site of structured counter-governance. This framework is not confined to U.S. tribal contexts. It resonates with a broader “global Indigenous politics of care,” which I define as the transnational, relational, and place-based practices through which Indigenous nations reclaim family governance and resist carceral child welfare regimes.

In addition to the overlapping structure seen in

Figure 1, the Third Space of Indian Child Welfare takes shape through three interconnected processes: Strategic Legal Engagement, Kinship-Based Care, and Tribally Controlled Family Collectives. Each represents an expression of Indigenous sovereignty that challenges settler-colonial infrastructures while advancing community-rooted systems of care, governance, and belonging.

This approach aligns with abolitionist praxis. Abolition involves dismantling harmful systems, building alternatives, and reimagining care and justice grounded in community-defined values. Indigenous nations practicing child welfare governance in the Third Space embody similar commitments. Through legal advocacy, caregiving, and institutional innovation, tribes reclaim the terms of family, safety, and belonging. These practices transform child welfare from a tool of settler control into a dynamic field of Indigenous governance and world-building.

- (1)

Strategic Legal Engagement reflects the abolitionist imperative to dismantle settler systems rooted in domination and erasure by asserting tribal jurisdiction and reshaping legal governance. Across the U.S., tribes have developed children’s codes, established tribal courts to protect their families, and built legal teams to defend their rights under the ICWA. They intervene in state custody cases, file amicus briefs in federal courts, and negotiate government-to-government agreements affirming their authority in child welfare. These actions expose the assimilationist foundations of U.S. child welfare law and create spaces for Indigenous self-determination. Engaging settler legal systems becomes an expression of care and governance rooted in Indigenous values.

- (2)

Kinship-Based Care reflects the abolitionist commitment to building community-driven alternatives to settler interventions. This care is rooted in extended family systems, customary caregiving, and collective responsibility that prioritize the child’s relationship to culture and community rather than compliance with settler definitions of permanency and placement. Tribes prioritize kin-first placements, customary caregiving, and intergenerational support systems that sustain cultural connection and collective responsibility. Programs like home-visiting, language revitalization, cultural mentorship, and ceremony maintain children’s ties to their communities, even within formal custody arrangements. These practices resist punitive models and cultivate life-affirming pathways of care grounded in relational accountability.

- (3)

Tribally Controlled Family Collectives reflect the abolitionist imperative to imagine new forms of care and justice. Through tribally licensed foster homes, community-run service agencies, and culturally grounded family courts, Native nations develop sovereign child welfare systems that reflect Indigenous law and cultural resurgence. Practices such as customary adoption, which do not require terminating parental rights, demonstrate how tribes build institutions centered on kinship, continuity, and collective governance.

Table 1 illustrates how processes within the Third Space align with abolitionist praxis, advancing Indigenous sovereignty by dismantling settler systems, building community-rooted care, and imagining relational futures.

The Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 offers a clear example of how the Third Space operates as a site of Indigenous governance. Often portrayed as a federal safeguard, ICWA also exemplifies how tribal nations have used the law as a strategic lever for Indigenous worldbuilding. By asserting jurisdiction in custody cases, defending ICWA in court, and embedding its principles into tribal codes and courts, Native nations have turned a contested federal law into a platform for revitalizing Indigenous care systems. As the next section illustrates, ICWA reflects the dynamic interplay between Indigenous sovereignty, settler law, and kinship restoration, exemplifying how Third Space governance confronts settler colonial violence while constructing sovereign futures for Native families and communities.

3. The Indian Child Welfare Act and Indigenous Resistance as Abolitionist Praxis

The passage of

ICWA (

1978) marked a pivotal moment in the resistance of Native nations in the U.S. within the Third Space of Indian child welfare. The ICWA codified tribal authority within federal law, directly challenging frameworks that sought to separate Native children from their communities. For generations, Indigenous Peoples resisted state control over their children by drawing on cultural teachings and embedding justice into both federal and tribal law. The ICWA, the result of tireless advocacy by Native families and allies, sought to preserve Native kinship networks and protect the integrity of tribal families. To this end, the Act emphasized the central role of children to tribal survival, stating that “no resource is more vital to the continued existence and integrity of Indian tribes than their children” and acknowledging the U.S. government’s historic failure to respect “the essential tribal relations of Indian people and the cultural and social standards prevailing in Indian communities and families” (§1901).

ICWA established federal standards for the removal and placement of Indian children, to “protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families” (§1902). It also defined key terms such as “Indian”, “Indian child”, and “Indian tribe” and included provisions for child custody proceedings, such as requiring notification to tribes when a child is taken into foster care and ensuring active efforts to keep Indigenous families together. The ICWA also made clear that Indian tribes have jurisdiction over cases involving children living on reservations. For Indian children living off-reservation, the state is required to transfer jurisdiction to the tribe unless there are legitimate reasons not to (

Crofoot and Harris 2012;

Williams et al. 2015). Additionally, the ICWA prioritizes placing children with extended family members, other tribal citizens, or Native families who reflect “the unique values of Indian culture” (§1902).

Early research highlights the ICWA’s success when implemented effectively. For instance, a California study from 1988–1992 found that Native children had the highest rates of kinship adoption among all racial and ethnic groups (

Barth et al. 2002). However, the study also found that Native children’s adoption rates were much lower than white or Latinx children and that it was rare for Native children to be adopted by Native couples (

Barth et al. 2002). Another study on frontline child welfare workers found that explicit training on the ICWA’s requirements improved workers’ cultural competence and understanding of the law (

Lawrence et al. 2012). Further evidence shows that the ICWA is particularly effective in reducing out-of-home placements when supports are in place, such as tribal-state agreements, culturally competent training, and additional support for kinship placements (

Bussey and Lucero 2013;

Trope and O’Loughlin 2014;

Haight et al. 2018). Such disparities emphasize the enduring importance of the ICWA and demonstrate why Indigenous Peoples continue to build culturally informed systems of care within the Third Space of Indian child welfare.

Similar structural legacies are found across settler colonial contexts where Indigenous families still endure the long-term impacts of family separation, cultural erasure, and institutional neglect. In Canada, the legacy of residential schools is evident in the disproportionate number of Indigenous children in foster care. Native youth represent only 7.7% of the child population, yet they account for 53.8% of children in care (

Indigenous Services Canada 2025). Structural inequities also shape the broader social context. Nearly 38% of Indigenous children in Canada live in poverty, compared to just 7% of non-Indigenous children (

Indigenous Services Canada 2025). Further, First Nations’ youth face significant barriers to educational attainment as 63% graduate from high school compared to 91% of non-Indigenous youth (

Indigenous Services Canada 2025).

In Australia, similar disparities persist. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children represent 41% of all children in out-of-home care, despite making up only 6% of the total child population (

SNAICC 2025). They are 10.8 times more likely to be placed in care than non-Indigenous children and 11.5 times more likely to be removed as infants. Modern boarding schools, particularly in remote areas, continue to reproduce disconnection by isolating Indigenous youth from their families, cultures, and communities (

SNAICC 2025). These institutions often fail to meet students’ emotional, cultural, and developmental needs and contribute to students leaving school and long-term harm to family integrity (

Guenther and Fogarty 2020;

Benveniste 2018).

In response, Indigenous rights movements emphasize decolonization as a necessary step toward justice. Research on Indigenous child welfare globally highlights the need to shift authority away from colonial institutions and back into the hands of Native nations to ensure that child welfare systems serve Indigenous communities (

Libesman 2014). The Third Space of Indian child welfare names this global imperative: to move beyond symbolic reforms and return decision-making power to Indigenous communities. It offers a model for building child welfare systems rooted in cultural continuity, collective care, and Indigenous sovereignty.

3.1. The Indian Child Welfare Act Is Abolitionist Praxis

While

Section 3 introduces the legal foundation and contested application of the ICWA, this subsection focuses on how the law functions as an abolitionist tool of Indigenous governance within the Third Space. The Indian Child Welfare Act demands an end to the systemic removal of Native children while empowering Native communities to implement tribally-led solutions to issues surrounding their children’s health and well-being. In addition to making significant strides toward creating more just family futures for Indigenous children, the ICWA is a landmark example of abolitionist praxis because it directly challenges the carceral logics of settler colonialism and calls out the state’s systemic abuse of Native families. By embedding Indigenous kinship models into law, the ICWA also counters the settler-colonial erasure of Native family structures and reaffirms relational accountability and collective care as foundational principles of Indigenous child welfare.

Operating within the Third Space of Indian child welfare, tribal nations assert their sovereignty by maintaining extended family networks rather than removing children from them. The ICWA prioritizes placing Native children with extended kin or within their tribal communities, ensuring their connection to cultural identity and tribal governance. These placements challenge settler definitions of family, which prioritize nuclear and state-sanctioned forms of guardianship over Indigenous frameworks of collective caregiving.

In doing so, Indigenous nations highlight the coexistence of two parallel systems: one rooted in Indigenous sovereignty and collective care, and the other entrenched in punitive settler-state frameworks. This structural divide reflects broader tensions between Indigenous self-determination and the continued dominance of colonial legal mechanisms.

3.2. Indigenous-Led Child Welfare Practices

While the previous section emphasized how ICWA interrupts settler legal authority, this section centers the ways Indigenous nations reimagine care through culturally grounded practices and tribal institutions. Recognizing the challenges of implementing the ICWA, Native nations and advocates have expanded upon its principles to develop culturally specific child welfare initiatives. At the tribal level, many tribal legal codes redefine “extended family” to align with Indigenous conceptions of kinship, reinforcing care systems that extend beyond the nuclear family (

Starks et al. 2015). For example, the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe established

Noojimo’wiigamig Inaawanidiwag, meaning (Healing Journey), a Family Healing Wellness Court designed to protect their way of life by keeping families together, fostering intergenerational healing, and restoring community balance.

1 Similarly, tribal child welfare systems connect families with culturally grounded services, which help strengthen kinship ties and reduce the need for state intervention (

Berger 2019).

Tribal customary adoption exemplifies this approach by rejecting the settler requirement to sever legal ties with biological families. Instead, customary adoption formalizes Indigenous models of care and maintains the child’s connections to their culture and community. As Terry Cross and Kathleen Fox explain, “Customary adoption fits culturally with the extended family concept and it formalizes and protects ongoing care of the child by an extended family member or other recognized potential parents” (

Cross and Fox 2014, p. 427). In California, the State Court System has recognized tribal customary adoptions for over 15 years, acknowledging its role in providing permanency and stability for dependent Native children who cannot be reunified with their biological parents (

California Courts 2025). This recognition is particularly salient because formal adoption is often seen as the ideal form of permanency over other formal options such as guardianship (

Albert and Mulzer 2022). This practice contrasts dramatically with the historical trauma of Native children’s forced removal into white, middle-class nuclear families (

Jacobs 2013).

In addition to changing adoption processes, scholars and advocates working with and alongside Native Peoples generally agree on the necessity of integrating Indigenous cultures and worldviews into child welfare and family health practices to better support Native families. A 2020 report on the National Needs Assessment of American Indian/Alaska Native Child Welfare Programs (NRC4Tribes) confirmed the frequency and value of this work. NRC4Tribes found that many tribal child welfare programs and workers frequently adopt a relational worldview and reported that practices rooted in relationships with one another, the environment, emotional and mental well-being, and spirituality are all deeply valued (

Cross 1986;

Lucero 2007). For example, tribal programs often prioritize cultural values, such as the protection of tribal relationships; they allow more time to address complex issues, such as unemployment and addiction compared to state and county programs; and they engage more frequently with families, thus reducing the distance between tribal workers and the families they serve (

National Child Welfare Resource Center for Tribes 2011).

Collectively, Indigenous-led efforts reflect the Third Space of Indian child welfare in practice where kinship, community, and culture are centered over carceral interventions. A growing body of literature advocates for this more expansive understanding of family that moves beyond settler definitions of guardianship and care.

3.3. The Carceral Logic of Child Welfare and the ICWA as a Model for Abolitionist Futures

The U.S. abolitionist tradition originated as a collective resistance to the enslavement of African Peoples and expanded during Reconstruction, when prisons, convict labor systems, and other mechanisms were created to sustain racial hierarchies (

Grinnell Davis et al. 2022). Abolitionist principles reject the surveillance and punishment embedded in carceral systems and call for transformative care rooted in community empowerment (

Critical Resistance n.d.;

Gilmore 2019;

Richie and Martensen 2020). Settler institutions mark certain bodies, families, and ways of life as problematic or undeserving. Abolitionist perspectives emphasize that violent systems cannot be reformed, as they are fundamentally designed to police marginalized families (

Kim et al. 2024;

Rocha Beardall and Edwards 2021). Today, abolitionist principles continue to shape social movements that not only expose harm but also actively demand a reimagining of justice and liberation for all.

The modern child welfare system must be understood as part of this broader carceral architecture. It shares its origins and practices with racialized carceral institutions that perpetuate settler colonial and white supremacist ideals. Consequently, abolitionists also highlight how the U.S. child welfare system disproportionately targets marginalized communities based on race, class, gender, age, ability, and other social identities. These forms of state intervention are often disguised as “services” while reproducing long-standing logics of surveillance and control (

Gilmore 2019;

Richie and Martensen 2020). In response, abolitionist social workers seek to dismantle these carceral frameworks by advocating for systems that prioritize care, healing, and collective responsibility. Such biases embedded in child welfare reflect the systemic harms abolitionists aim to abolish (

Grinnell Davis et al. 2022;

Toraif and Mueller 2023).

Abolition begins with rejecting punitive systems, but it also demands that we reimagine how justice and care are defined, built, and sustained. Abolitionist movements stress the importance of expanding one’s imagination beyond white supremacy to understand the root causes of harm and to envision new systems that are not based on policing or punishment. This abolitionist imperative deeply resonates with Indigenous movements that seek to dismantle colonial family separation and to assert sovereignty through kinship, cultural identity, and relational autonomy. Both frameworks envision a world in which families are not criminalized or fragmented, but are supported through systems that uphold dignity, community-based accountability, and sovereignty.

Indigenous Peoples have long advanced abolitionist futures based on deep connections to land, kinship, and collective well-being (

Coulthard and Simpson 2016). This vision is shaped by Indigenous “dreaming,” a concept that sees the past, present, and future as entangled in ongoing practices of care and resurgence (

Bishop et al. 2012, p. 30;

Rogers 2024). Dreaming offers an alternative to punitive state interventions by affirming thriving communities rooted in interdependence and non-disposability (

Ballard 2014;

Gee et al. 2014;

Moreton-Robinson 2020;

Rogers 2024). Within this framework, children and families are seen as essential members of a community that cannot be separated or discarded (

Ballard 2014). Tribal nations enact this vision in the Third Space of Indian child welfare by asserting sovereignty over family governance, rejecting settler-imposed binaries, and revitalizing intergenerational knowledge systems that center relational accountability (

Bishop et al. 2012;

Moreton-Robinson 2020;

Rogers 2024).

ICWA serves as a critical site where Indigenous abolitionist futures move from vision to legal and institutional practice. Abolitionist principles are embodied through ICWA by offering a legal framework that resists the carceral and colonial underpinnings of the child welfare system. Scholars draw direct connections between the system’s anti-Indigenous and settler-colonial logics and its contemporary practices, including the way parental rights have been structured similarly to property rights, and how “child saving” discourses mask assimilationist policies (

van Schilfgaarde and Shelton 2021). This work aligns with broader calls to construct care systems that reflect tribal sovereignty, cultural identity, and community accountability (

Rocha Beardall and Edwards 2021).

The enduring importance of the ICWA lies in its dual role as a federal safeguard against settler erasure and a model for how tribal nations can assert sovereignty to protect their children and communities. This work highlights the deep connection between the abolitionist and Indigenous movements. Its alignment with abolitionist thought reinforces the rejection of punitive state intervention in favor of care systems based on relational accountability and collective well-being. By exposing the child welfare system as an extension of settler colonialism and racial capitalism, the ICWA presents a pathway toward liberation that resonates with abolitionist movements seeking resource-abundant, self-determined communities of care.

The ICWA exemplifies how abolitionist and decolonial frameworks converge through Indigenous legal innovation. As

Chartrand and Rougier (

2021, p. 23) argue, “abolition must be grounded in anti-colonial approaches that center Indigenous knowledge and ways of being.” ICWA demonstrates how Indigenous communities adapt legal mechanisms in ways that refuse settler definitions of family and reassert the relational values necessary for just futures. While rooted in distinct histories of struggle, both early abolitionist movements and Indigenous assertions of sovereignty have envisioned liberation as a break from systems of imposed control. For Indigenous nations, this includes the freedom to care for their children outside the authority of settler institutions. These movements share a commitment to rejecting punitive systems and to building care networks grounded in cultural identity, relational autonomy, and self-determination.

4. Contemporary Legal Challenges to the ICWA

Contemporary legal challenges to the ICWA abound and underscore how threatening the Indigenous Third Space of Indian child welfare is to settler systems. In 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court heard Haaland v. Brackeen, a case that consolidated multiple challenges to the ICWA. The non-Native plaintiffs argued that the ICWA violated the anti-commandeering principles of the Tenth Amendment and “infringes on the states’ authority over family law”, preventing non-Native couples from adopting Native children (

Haaland v. Brackeen 2023). While the district court initially ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, the U.S. Court of Appeals reversed the decision, upholding the ICWA’s constitutionality and reaffirming the sovereignty of tribal nations in determining the welfare of their children. Here, ICWA functions as a jurisdictional flashpoint, where competing legal orders (e.g., Indigenous sovereignty and settler-state authority) collide over the fundamental question of who has the right to define and protect Native families.

Legal challenges to the ICWA are not new, but they do reflect a longstanding pattern of settler resistance to Indigenous sovereignty. Since the ICWA’s passage in 1978, various cases have attempted to weaken its authority, arguing that it imposes racial classifications rather than recognizing tribal citizenship. For example,

Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl (

2013) sought to challenge ICWA’s placement preferences, while

Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield (

1989) affirmed the importance of tribal jurisdiction in child welfare cases. Brackeen represents the latest iteration of this backlash, using race-neutral rhetoric to undermine tribal governance while advancing settler control over Native children. This series of cases exposes the enduring tensions between Indigenous sovereignty and settler-state legal structures, demonstrating that the ICWA remains a contested site of struggle over Indigenous self-determination. Thus, engagement with settler courts operates as a strategic maneuver to fracture settler authority from within, creating openings for Indigenous governance to expand in legal and institutional spaces originally designed to suppress it.

The current legal challenges echo the mid-20th century justifications for the removal and adoption of Native children, revealing a continuity in settler colonial logics. In both eras, Native families are portrayed as inherently unfit or incapable of caring for their children, reinforcing stereotypes rooted in settler colonial ideologies. Legal and bureaucratic mechanisms continue to be deployed to erode Native self-determination, whether through assimilationist policies in the past or contemporary efforts to undermine ICWA. In many respects, Indigenous sovereignty and cultural preservation are reframed not as rights to be upheld, but as barriers to an imagined standard of equality rooted in settler norms.

5. Conclusions

Amid ongoing U.S. Supreme Court challenges to the Indian Child Welfare Act, the Third Space of Indian child welfare rejects reductive framings of Indigenous resistance as merely reactive. Instead, it reveals how tribal nations actively carve out spaces for self-determination, care, and cultural resurgence. By centering Indigenous worldviews and refusing settler-imposed binaries, such as assimilation versus independence (

Bruyneel 2007), the Third Space offers a framework for reimagining child welfare systems grounded in sovereignty and justice for Native families.

The ICWA remains a compelling case study of how Indigenous Peoples protect their children and kinship systems through active world-building. Even when misread, resisted, or unevenly implemented, the ICWA reaffirms what Native nations have long maintained: “there is no resource that is more vital to the continued existence and integrity of Indian tribes than their children” (

Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl 2013;

Rocha Beardall 2016). Within the Third Space, this resistance materializes through three (of many) interrelated strategies: strategic legal engagement, kinship-based caregiving, and tribally controlled child welfare systems that remake how care is practiced and protected on Indigenous terms.

These interventions are not symbolic. They are structural, legal, and epistemological acts of abolitionist governance. Native families and nations are not waiting for permission to care for their children. They are building systems of care that transcend colonial constraints through practices that reject surveillance, dispossession, and punitive logics, and instead enact Indigenous collective values, relational accountability, and cultural resurgence. In doing so, they challenge sociological understandings of governance by showing how Indigenous nations repurpose settler institutions as sites of counter-sovereignty and relational world-building.

This framework also extends beyond U.S. borders. Because colonial family separation is systemic and transnational, Indigenous-led responses must be equally expansive. Movements in Aotearoa, Australia, and Canada demonstrate a trans-Indigenous politics of care, where diverse nations reclaim jurisdiction over family governance through strategies rooted in place-based sovereignty and cultural resurgence (

Ghanayem and Rocha Beardall 2024). Global movements to reclaim child welfare, be they healing courts, customary adoptions, or community-based caregiving, demonstrate the urgent need to dismantle settler logics and build institutions grounded in political self-determination.

Ultimately, the Third Space of Indian child welfare is a transformative framework for engaging with other families—immigrant, queer, and otherwise minoritized—who are likewise targeted by state systems of regulation and removal. The pursuit of self-determination in raising and protecting children is not geographically bound; it is a collective, ongoing project of abolition and justice. The Third Space reminds us that kinship is not only what has been disrupted by settler colonialism but also what is being continuously remade in its wake. This framework illuminates how Indigenous peoples actively repurpose legal institutions, reconfigure care, and reclaim family governance on their own terms. In doing so, it expands how we understand sovereignty, care, and law in relation to family-making and social reproduction.

Building on this, I offer the term “global Indigenous politics of care” to name an emergent field of theory and practice grounded in Indigenous governance, relational accountability, and the refusal of carceral logics. This politics spans nations and continents, connecting diverse Indigenous struggles over land, kinship, and jurisdiction through shared commitments to care as a site of resistance and resurgence. Movements in Aotearoa, Australia, and Canada exemplify this transnational praxis, as Indigenous nations assert sovereignty through place-based systems of caregiving and cultural resurgence (

Ghanayem and Rocha Beardall 2024). As both a conceptual and political formation, a global Indigenous politics of care challenges dominant paradigms of family, law, and state legitimacy, while offering alternative frameworks rooted in interdependence and decolonial futures. Future research must continue to map, theorize, and support this politics across geographies, disciplines, and generations, as Indigenous communities build new infrastructures of care that are global in vision and grounded in local sovereignty.