Abstract

Aboriginal communities in Australia have long advocated for self-determination in child protection. This includes appeals for greater structural authority in systems of care and protection, with Aboriginal children in the care of Aboriginal agencies. Advocacy from agencies, including the Victorian Aboriginal Child and Community Agency (VACCA), has resulted in legislative and funding reforms in Victoria that place Victorian Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (ACCOs) at the forefront of responses supporting Aboriginal children and families. This article provides an overview of that advocacy, the context in which the reform arose. Then, it details how VACCA has implemented the reforms by developing a model for Aboriginal child protection centred on culture, self-determination and human rights. Importantly, it discusses the process and negotiation of transferring authority exercised by the government to ACCOs and offers insights for the system and practice transformation. This article outlines how ACCOs like VACCA are shifting the language, culture and practice of child protection.

1. Introduction

The term “Aboriginal” applies to people from a diverse range of communities and around 400 distinct countries within Australia, including Torres Strait Islanders1 that reflect considerable variation in history, language, experiences of colonisation, parenting practices and cultural mores (Horton 1994; Bamblett et al. 2010). Colonisation has impacted communities in varying degrees, ranging from severe cultural and land disconnection to some communities retaining language and land but with ongoing disempowerment (Bamblett et al. 2010). Australia was colonised by Great Britain without any formalised treaties with Aboriginal peoples (Bamblett et al. 2010), and this has contributed to poorer health outcomes and disproportionate involvement in child protection and justice systems (The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2009; Bamblett et al. 2010).

Under the guise of “protection “and “assimilation”, successive Australian governments have made official policies that denied Aboriginal people’s agency and control over their destiny, lands and children. These policies enabled the systematic removal of children from their families and community, including the children of the Stolen Generation (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023). This was premised on the mistaken belief that Aboriginal communities cannot be self-determining, leading to children suffering abuse, losing connection to their families and experiencing alienation from their own culture and unable to fit into a white culture (Bamblett and Lewis 2006a, 2006b). The 2023 Yoorrook Justice Commission examined the individual and collective impact of systemic injustice and the intergenerational trauma that has flowed from colonisation. The Commission found that Aboriginal children were taken away from Aboriginal families for the purpose of assimilation (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023).

For Aboriginal people in Victoria, the Yoorrook Justice Commission reported an unbroken connection between their experiences with colonial child removal practices and the current Victorian child protection system. The inquiry stated that the “child protection system was an instrument of colonisation and still is”, and while the present system is not assimilationist in law, it does not operate as it should (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023, p. 178). To avoid the current child protection system operating as assimilationist in fact, genuine self-determination in child protection must be embedded.

Self-determination of Aboriginal peoples is a collective right under international law and essential for realising human and cultural rights (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023). Research tells us that self-determination is the only policy approach that produces effective and sustainable outcomes for Aboriginal people (Behrendt et al. 2016) and that self-determination is necessary if our children are to have a future (Bamblett and Lewis 2006b). The Yoorrook Justice Commission reinforced that meaningful, transformative change requires genuine self-determination in Victoria’s child protection and criminal justice systems and “this is what our people seek” (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023, p. 10). This call echoes those of the Bringing Them Home (BTH) report, a landmark inquiry into the historic and ongoing separation of Aboriginal children from their families, more than 25 years earlier (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC 1997) which emphasised that consultation with, and participation of Aboriginal families is insufficient. Self-determination requires the transfer of decision making and resources to Aboriginal communities to effectively implement decisions for their children, families and communities (Libesman and Gray 2023). Furthermore, Aboriginal communities in Victoria are moving towards a Treaty as a mechanism to further support self-determination (Treaty Authority n.d.).

Self-determination is a key focus for Aboriginal advocacy in child protection systems nationally (Commonwealth of Australia 2022; Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care, SNAICC 2024). However, the system has been characterised by cycles of government reviews without substantial action for change (Davis 2019). A lack of meaningful self-determination in child protection is seen as a critical issue in need of transformation if improved outcomes for Aboriginal children are to be achieved (Libesman and Gray 2023). Appropriate governance structures are essential for reducing the over-representation of Aboriginal children in child protection and ensuring these systems are culturally relevant (Bamblett and Lewis 2006a).

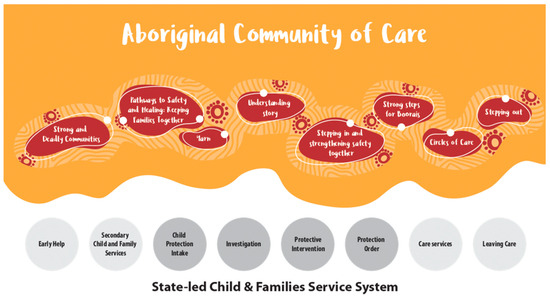

The Victorian Aboriginal Child and Community Agency (VACCA) was established in 1977 as the first statewide Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation (ACCO) in Australia. It was founded in response to the widespread removal of Aboriginal children who were at risk and without cultural support or connection back to their communities (Bamblett et al. 2010). For nearly two decades, VACCA has led the transformation of Victoria’s child protection system from a state-led approach towards an Aboriginal community of care model (see Figure 2) founded on culture, self-determination and human rights2. This advocacy has driven key legislative, funding and programme reforms, enabling ACCOs to assume greater responsibility for child protection services previously managed by the government.

In 2017, the Victorian Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH) commenced transferring statutory responsibility for Aboriginal families on children’s court protection orders to ACCOs. VACCA’s Nugel programme was the first of these “Aboriginal Children in Aboriginal Care” (ACAC) programmes to be implemented in Victoria. Since then, several other ACCOs are in the pre-authorisation phase (pilot testing, such as the VACCA “As If” programme described below) or have completed pilot testing and are now fully authorised to deliver ACAC in Victoria. In 2023, legislative reform allowed investigations to commence through VACCA’s Community Protecting Boorais pilot. The Nugel programme broadly encompasses the phases of investigation work, known as “Community Protecting Boorais”, and ongoing case management, known as “Strong Steps for Boorais”. VACCA’s Nugel programme is a demonstration of self-determination in action, challenging colonial power structures, reclaiming Aboriginal authority over the lives of children and offering a healing-centred, culturally grounded alternative to child protection systems that have historically caused harm.

Method and Purpose of Paper

This study is written from the standpoint of senior practitioners and leaders within VACCA, prioritising the voices and perspectives of Aboriginal people and their experiences providing for the safety and wellbeing of Aboriginal children. It captures the views and opinions of VACCA staff, using collective storytelling methodologies, a traditional Aboriginal method that can benefit the emancipation of Aboriginal communities (Rigney 1999).

The paper explores the work VACCA has carried out, and continues to do, to enact aspirations for self-determination in child protection. It discusses the context in which this significant reform arose, how the Nugel programme elements were developed and offers insights for broader sector system and practice transformation. Importantly, it discusses the process and negotiation of transferring authority exercised by the government to ACCOs, including resisting the imposition of settler-government interventions and advocating for systems and practices that reduce harmful interventions in the lives of Aboriginal children, families and communities.

2. Conceptualising the Challenge for Aboriginal Children and Families in Child Protection

It is widely acknowledged and recognised that the current child protection model does not respond well to Aboriginal children and families in crisis (Davis 2019; Rice and Stubbs 2023; Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023). The over-representation of Aboriginal children in child protection is largely driven by the failures of the current service system, which focuses on removing children as an intervention, only perpetuating intergenerational harm. Evidence shows that child protection involvement is associated with a range of poor outcomes for Aboriginal children (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023).

VACCA has observed first-hand the poor decisions made about Aboriginal children through settler child protection systems, including government departments and courts. The Yoorrook Justice Commission supported this view, highlighting that risk assessments of Aboriginal families undertaken by child protection authorities were often biased and racist, leading to poor decisions for families (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023).

The Yooorook Justice Commission heard that Aboriginal children suffered in key ways, including biased assessments, unnecessary removal from families in instances where caseworkers could have worked with the family to keep the children safe; and a lack of support to maintain key connection to their family, community and culture following removal (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023). Enduring connections with family, community and culture are critical to lifelong wellbeing and act as a protective factor by fostering resilience, identity and community cohesion (Gee et al. 2014). Decision making was not in Aboriginal people’s hands, contributing to decisions that devalued Aboriginal families and their cultural needs. (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023; Bamblett 2024).

To address these challenges, VACCA led the reform agenda, moving from passive actor to dynamic influencer. Reimagining a new approach involved addressing key structural foundations of legislation governing child protection, fact-finding overseas and designing cultural frameworks and new ways of practice grounded in self-determination.

3. Key Reforms—Timeline and Reflections in Moving Towards an Aboriginal-Led Community of Care

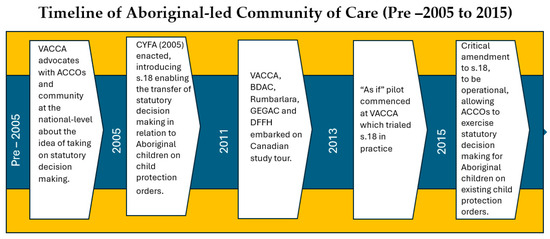

The Nugel program, integrated within the Aboriginal-led Community of Care (refer to Figure 2), emerged from a decade of advocacy for structural and legislative reforms (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

First decade of key structural, fact-finding and piloting in moving towards an Aboriginal-led Community of Care.

3.1. Pre –2005 and 2005

In initial discussions, there was understandable caution within Aboriginal communities and their community-controlled organisations about the idea of taking on statutory decision making. Some community members were concerned about taking on greater responsibility within a system that routinely fails Aboriginal families and communities. A significant concern was whether the community would stop accessing ACCO services because of the prevailing view that child protection work was about removing children. However, VACCA felt strongly that the only way to reduce the rate of child removals and the number of Aboriginal children in Out of Home Care (OOHC) was to take on this responsibility. Doing so would enable different decisions and practices, achieving different results, including prioritising family preservation and restoration. We saw this as an opportunity to exercise responsibility differently, not be part of the settler state child protection system, but to start asserting these long-held aspirations for self-determination in the system.

In 2005, the Victorian Children Youth and Family Act (CYFA 2005) was amended to include section 18 in the CYFA, enabling statutory decision-making authority for Aboriginal children on protection orders. However, it would take another 10 years before this power would be operationalised.

3.2. In the Years 2011–2016

In 2011, a multi-agency study tour of Canada included the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario, where First Peoples’ organisations were responsible for child protection. VACCA, Bendigo and District Aboriginal Co-operation (BDAC) and Gippsland and East Gippsland Aboriginal Cooperative. (GEGAC) and the DFFH examined how First Peoples’ organisations were operating in terms of policies, practices and legal frameworks. We learned that greater decision making in child welfare enabled a different approach for their children and families, and that it is possible to successfully transfer child protection authority to Aboriginal peoples, with the right enablers in place.

In 2013, DFFH funded a pre-authorisation pilot for VACCA to act “As if” they had the authorised delegation of the Secretary of DFFH. This pilot established decision making and case management functions. The two-year “As if” pilot was a breakthrough, laying the foundation for the Nugel programme. It established decision making and case management for children in OOHC, creating robust systems for subsequent functions like investigation and assessment. By establishing case management functions first, we made a solid practice foundation. This ensured that when VACCA was authorised to undertake investigations and court-ordered interventions, we had a culturally safe programme ready to transfer children into. Importantly, it enabled us to rethink and develop our practice framework, including incorporating Cultural Therapeutic Ways (CTW), an organisational-wide approach embedded in all VACCA programmes. This approach is based on the cultural determinants of health and wellbeing and the Social, Emotional and Wellbeing (SEWB) model, prioritising Aboriginal cultural wisdom and providing staff with tools to work in a culturally therapeutic way (Gee et al. 2014).

The “As if” pilot was crucial not only for establishing our practice but also for negotiating our interface with the government. However, there were some perceptions in government that VACCA was not equipped to deliver the programme. One challenge was the onerous task of demonstrating readiness and providing strong evidence of accountability to DFFH. While we welcomed accountability for statutory services, there were inconsistent expectations from the government. For example, we were required to fulfil all specified standards and use specific assessment tools, whereas DFFH, which also has statutory authority and decision-making power for child protection, was not subject to the same level of scrutiny.

The process of transferring authority was also not an easy transition. DFFH found it difficult to relinquish control and power, and we grappled to obtain control and authority. Drip-fed funding for the programme from DFFH has also been problematic, making it difficult to obtain the required momentum and consistent overall transformational shift in the system that has historically, and continues to, fail so many Aboriginal children and families.

3.3. 2017–2025 Moving Towards an Aboriginal-Led Community of Care

In 2017, the Nugel programme (Strong Steps phase) progressed from a pre-authorisation pilot to implementation in the Northern Region of Melbourne. By 2025, it had expanded to other areas serviced by VACCA and other ACCOs in Victoria. Key milestones in this phase included legislative reform and the development and design of the Nugel programme and practice approach. In 2023, VACCA’s statutory authority expanded to undertake investigation work, bringing us closer to the Aboriginal-led Community of Care that we envisioned to ensure Aboriginal decision-making authority is applied across all aspects of child protection, from assessment to programme implementation and family supports. When the legislation was amended, VACCA had the opportunity to investigate protective concerns from an Aboriginal lens to help divert families away from the system.

The investigation phase at VACCA includes understanding the story and, if risk is substantiated, stepping in and strengthening safety together. If parents agree to address concerns and protect the child, this phase can continue without legal intervention for up to 180 days. If voluntary engagement fails or concerns persist, Nugel must take action, possibly making a protective application to the children’s court. A protective application requests protection for a child, while a protective order is the court’s legal measure to ensure safety. When the Children’s Court issues a protection order, the child is found in need of protection under the CYFA, and the child and family then transfer to Nugel’s Strong Steps for Boorais programme for case management. Direct transfers to the Strong Steps programme can also occur through a Court application when significant harm has occurred or is likely, and parents have not or are unlikely to protect the child.

VACCA’s Nugel programme is just one part of VACCA’s broader vision/agenda of Aboriginal Community of Care that aims to deliver a culturally safe and responsive service system that families feel safe in, and which is always a safety net for them. This includes prevention programmes, Strong and Deadly Communities, right through to tertiary intervention such as Strong Steps for Boorais. Figure 2 shows the Aboriginal Community of Care model, which includes the key phases of Nugel (Understanding Story, Stepping in and strengthening safety together3, Strong steps for Boorais), along with other programmes (i.e., Strong and Deadly Communities and Pathways to Safety and Healing: Keeping families together) that are part of the model. In addition, the lower half of the infographic shows the corresponding phases and programmes within the state-led service system, and this illustrates the different languages that VACCA uses in each of its phases and the wraparound services that can support the family.

Figure 2.

An Aboriginal Community of Care versus the State-led Service System.

3.4. Legislative Enablers

Over time, the legislation in the CYFA has been amended and improved, allowing for the transformation from a state-led government child protection service towards an Aboriginal-led Community of Care. There were several key milestones in the legislative reform. In 2015, the “As if” pilot highlighted the need for an amendment to the CYFA, allowing Aboriginal agencies to exercise statutory decision making in case planning and case management for Aboriginal children and young people subject to protection orders made by the children’s court. The other key amendment in 2023 was the introduction of the Statement of Recognition to the CYFA, as an important commitment towards self-determination in child protection and expansion of Aboriginal authority. This enabled ACCOs to step in at the point of ‘investigation’ to do the work of prevention and initiated the commencement of the Community Protecting Boorais pilot at VACCA and BDAC in October 2023.

3.5. Re-Imagining a New Approach Rooted in Aboriginal Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing

The VACCA model encompasses integrated child protection services, providing wrap-around culturally responsive and trauma-informed supports to children, young people and their families based on their needs, embedded within culture and Aboriginal ways of knowing. The vision of Nugel reflects the rich history within Aboriginal cultures of community, having responsibility for protecting and raising children. Nugel is based on a practice approach that is underpinned by human rights, which recognises that it is in the best interest of the child to be protected from harm and abuse and have a relationship with their parents and family.

The Nugel programme development and practice design, including case management and investigations, were guided by the practical wisdom of Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing, complemented by Aboriginal child protection research evidence contrasting with Western perspectives on attachment, stability and permanency. This research prioritises the role of family, kinship, community and cultural identity as the foundation of a child’s stability and wellbeing (Krakouer et al. 2018; Verbunt et al. 2021).

3.5.1. Re-Imagining Case Management (Strong Steps for Boorais)

The Nugel practice approach recognises that self-determination extends beyond legislative change, statutory decision making and case management. It involves embedding cultural supports and programmes that enable children to strengthen their connection to culture (Bamblett and Lewis 2007). The Nugel programme is a relational and strengths-based model that incorporates VACCA’s whole of organisation CTW framework, which is underpinned by the pillars of self-determination, trauma-informed and culturally responsive practice. This provides staff with the foundation for culturally informed casework that aims to heal, connect and protect.

3.5.2. Re-Imagining Investigations (Community Protecting Boorais Pilot)

In 2022, VACCA and BDAC rethought the business of ‘investigations’ to develop a model reflecting both statutory and cultural responsibilities. We did not want to just recreate the logics of the settler system; we wanted to create a service that meets the needs of Aboriginal children and families and responds to the challenge of child safety in a different way. We also recognised that government systems often overlook the cultural outcomes valued by Aboriginal communities, highlighting the need for us to define and develop these outcomes in partnership with families.

In rebuilding a system based on self-determination, the existing child protection logics and tools were rejected to re-develop, re-imagine and re-build the service system from a cultural standpoint. Key concepts such as risk management, safety, belonging, attachment, the centrality of culture and identity and the need for relational, strengths-based practices were critically interrogated and reimagined. Practice elements, including risk assessments, practitioner templates (i.e., court reports) and exercising of authority, were re-envisioned.

Language was considered important to influence positive change within the system and build rapport and trust with families. As shown in Figure 2, state terms like “Investigation” were replaced with “Understanding Story” and “Protective Intervention” with “Stepping in and Strengthening Safety Together” to convey a sense of partnership between VACCA and families. This is because harmful words like “protection” are linked directly to colonisation, having been “used to label the long-reaching and harmful state governance of Aboriginal people across three centuries” (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023, p. 48).

4. Nugel Program Elements and Service Delivery Approaches

Within the parameters provided by legislation, there is scope for programme elements and service delivery approaches to be enacted differently, creating opportunities for improved outcomes. This opportunity is central to the strategic approach of Aboriginal community organisations like VACCA in exercising greater authority across the system and enabling different programme approaches. The key elements of this approach are interrelated and are outlined briefly below.

4.1. Working with Families and Parents

Aboriginal families and communities continue to be concerned about how effectively child protection systems value and work with Aboriginal parents and families. VACCA views family and kinship connections as essential to the child’s identity, development and wellbeing, including efforts to promote safety and prevent harm and abuse, emphasising their cultural rights and the intent of the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle (ACPP).

The Nugel approach challenges Western child protection practices, which often prioritise legal orders that foreclose the possibility of restoration and limit a child’s contact with family to maintain placement stability. (Newton et al. 2024). We promote a broader concept of attachment and permanency that values collective caregiving, kinship networks, and enduring connections to their family, community and culture, rejecting narrow Western notions that can sever cultural ties. The Nugel programme prioritises supporting children’s rights to maintain contact with their parents and families, even in cases where non-reunification case plans are in place, through frequent visits, as well as return-to-Country programmes and other cultural experiences, grounded in relationships to kin and community. We believe that reunification should always remain an option if the family environment becomes safe because it fosters hope and strengthens opportunities for cultural restoration—an approach supported by the findings of the Yoorrook Justice Commission (2023) This requires a whole-of-service system approach, prioritising prevention and early support to avoid escalation to crisis where more intrusive interventions might be considered.

Acknowledging the history of colonial interventions in Aboriginal families, we recognise that many parents may not have experienced love, support, or care themselves and need parenting support (Bamblett and Lewis 2006a). Supporting families is a community and shared responsibility that can involve highlighting to Aboriginal parents that their strengths are deeply rooted in their cultural and relational worldviews. Unfortunately, these strengths are often misperceived by Western systems, including government and child welfare agencies, because they do not align with Western expectations of parenting (Wright et al. 2024). Working with families holistically and recognising their strengths is critical to achieving positive outcomes for children and families.

4.2. Relational, Strengths-Based and Non-Judgmental Approach

In prioritising working with parents and families, a practice philosophy is needed that is experienced as safe by families. This includes an approach that is relational, supportive and non-judgmental. While our practice benefits from smaller caseloads, it is our relational approach that truly enables VACCA to understand families’ stories and provide the family with the support they need. This support can include taking parents to appointments to help them access services and supports to address protective concerns, providing live-in supports to families, funding culturally based healing and connection supports for the whole family and using brokerage to enable children to experience return to Country.

Families are viewed non-judgmentally, with love, kindness and respect, with a focus on moving towards reunification rather than proving worthiness as parents. VACCA has characterised their relational practice approach as ‘Big Aunty Energy’, emphasising the cultural and relational components, and invoking ideas of love but also responsibility. ‘Big Aunty Energy’ reflects a cultural responsibility that includes delivering hard messages when required but conveyed with love and care for the family within their community. This was inspired by how the community has always stepped in to stand between a child and a risk. Our approach is also centred on principles of change and a spirit of hope, understanding a parent’s story while applying a fresh lens and consideration of present circumstances to assess risk and recognise the possibility of change. This supports families to be hopeful about change, including the possibility of restoration, as a foundation of effective practice.

4.3. Trauma-Informed and Holistic Approach

Aboriginal frameworks of healing and wellbeing often emphasise the important role of self-determination, culture and connections (Milroy et al. 2014; Gee et al. 2014), consistent with a multidimensional concept of wellbeing encompassing connections to body, mind, emotions, family, kinship, community, spirituality, country and culture (Gee et al. 2014).

Our approach also recognises the past and ongoing impact of colonial systems on Aboriginal communities, which often leads to environments of discrimination and cultural disconnection. Our practice is family-focused, holistic, culturally responsive and trauma-informed, prioritising spiritual, emotional and cultural wellbeing alongside physical care. VACCA aims to help break cycles of harm and promote healing by supporting families to reconnect with their cultural roots and reframe deficit-based internal narratives to a strengths-based perspective.

4.4. Cultural, Self-Determination and Identity Restoration

Consistent with these models of healing and wellbeing, supporting Aboriginal children requires culturally grounded systems that prioritise connection to culture, with interventions that nurture relationships to family, land, community and spirituality. Research supports embedding cultural frameworks in child protection practices to improve outcomes by maintaining strong cultural connections (Bamblett and Lewis 2006a, 2006b; Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023).

Culture is transmitted through everyday life, family and kinship networks, language, rituals, ceremonies and community participation. Culture is not just an add-on but is about imparting skills and beliefs onto the child in the social context in which they live (Bamblett and Lewis 2007). Aboriginal children have a right to be supported to experience their culture and build a connection to community through different mediums (such as arts, language and connection to Country), as well as through a range of programmes and activities that are developmentally and age appropriate for that child. This can include return to Country programmes, camps and cultural events as part of comprehensive cultural support plans that promote enjoyment of culture as a developmental and relational process.

Culture is a protective factor (Verbunt et al. 2021) and provides the foundations for identity and self-esteem. Active connections to family and community promote an understanding of their family story, promoting a positive sense of self and pride in their family and identity. This approach prioritises a sense of belonging and healing unmet needs, rather than just focusing on protection and safety. Because of this priority, VACCA has significantly higher completion rates of cultural support plans for children in care than government child protection authorities (Bamblett 2024).

4.5. Strengthening Safety Together Versus Risk Assessment

VACCA applies statutory risk management principles to our assessment of risk to strengthen safety. However, risk frameworks employed by government agencies are biased in their assessment of Aboriginal people and include harmful language and a lack of focus on strengthening safety (Yoorrook Justice Commission 2023). Instead, VACCA developed a bespoke approach focused on understanding the family’s story and strengths, working with the family to identify and address risk and strengthen safety. This approach is intended to enable more informed, balanced, unbiased and fair assessments, avoiding assumptions while encouraging reflection on the possibility for change for more informed decision making. This framework also recognises the harm inherent in removal and disconnection (Davis 2019) as part of a balanced assessment that considers alternative actions for addressing risk.

4.6. Legal Advocacy and Court Responses

Access to legal advocacy and support is recognised as a critical component of supporting families facing child protection involvement. This advocacy should consider the human rights of Aboriginal children and families, including their rights as Indigenous peoples, as well as their legal rights (Rice and Stubbs 2023). Consistent with good legal practice as outlined in concepts of the model litigant, legal advocacy should focus on quality, timely, factual, thorough and well-prepared litigation that facilitates progress through the court (McKeown 2010).

This is critical as judicial decision making is dependent on the quality of representations made to the Court. Recognising the limited nature of filings made regarding the best interests of Aboriginal children, VACCA has developed a comprehensive court report template that elevates the cultural rights inherent in best interest determinations. Further, it guides caseworkers to consider both the harm of abuse and harm caused by removal, family separation and cultural disconnection, as well as to consider alternative approaches that minimise harm and promote wellbeing. These approaches lead to quicker resolutions, less adversarial and prolonged proceedings, reduced court costs and, most importantly, better informed decisions (Inside Policy 2020; Bamblett 2024).

Supporting our approach is Marram Ngala Ganbu (MNG), a Koorie Family Court in Melbourne, that offers a more informal and supported process before a consistent magistrate who gets to know the families. This has led to more effective, culturally appropriate and just responses to Aboriginal families that enable greater participation by family members and culturally informed decision making (Arabena et al. 2019).

While the MNG approach is still within a colonial court, this is a demonstration of how improved approaches to processes and decisions can be made when Aboriginal perspectives and voices are elevated within existing court systems and legislation. VACCA advocates expanding this approach in other Children’s Courts across Victoria. This highlights a broader role that VACCA plays in the political arena to advocate for Aboriginal rights, law reform and self-determination, which extends to a range of institutions, including courts.

4.7. Wraparound Services

VACCA delivers a suite of culturally appropriate services, providing a range of wraparound services to support families. Like-minded staff deliver these approaches, and families benefit because they are part of a broader circle of care. We also consider the broader kinship system and provide support to the extended family, as we consider that a healthy, well-functioning support network will benefit the child.

We also recognise that Nugel needs to be linked with other supports to generate improvements to the Nugel model, and this includes services such as leaving care and education programmes, working with children with disabilities, parenting programmes, family services programmes, prevention and reunification, family violence programmes and cultural strengthening programmes.

5. Insights and Future Aspirations

5.1. Insights

There were several key insights that arose from this process of reform and transformation. Of importance, VACCA built the practice approach of the model first, so that when we were able to take on investigations, it ensured we could carry that work forward. This empowered us as decision makers as opposed to advisors, a role critical for self-determination to be meaningful.

Another insight was the practical value of the “As if” pilot, and while negotiating the government interface can be challenging, a pilot in a safe testing environment helped to develop key stakeholder relationships and establish a model that reflects the values of the Aboriginal community, enabling trust and legitimacy.

Reconceptualising the work was not about taking over the settler system, as that system does not work for Aboriginal families and communities. It is about negotiating authority with the government while reforming and re-imaging the framework and programme so that the services delivered are grounded on a different logical framework. This ensures that the services achieve the outcomes that are important to Aboriginal people.

5.2. Future Aspirations and Vision

5.2.1. Early Intervention and Prevention

VACCA’s vision for an Aboriginal Community of Care is to deliver services that families feel safe in, including providing statutory interventions. We see that providing responsive services as soft entry points is also important. We want the community to know that there is support and that they can experience this safely. If families need help, they will receive support without judgment, policing or monitoring. We will only intervene when required to ensure child safety; however, we want to provide support first before that is required.

Some of the future aspirations of VACCA are that every Aboriginal child can access a full suite of Aboriginal services, including a child protection service that is funded, because every Aboriginal child and family has a right to access services from their own community.

The vision is that if more families are referred to ACCOs during that early investigation phase (Understanding Story), we can then support families to come up with solutions to protect their own children against any alleged harms, strengthen safety and minimise the number of children entering care. Our vision is to have a smaller care system and a more holistic front-end system that can sit side-by-side in a coordinated response with our Nugel team, providing cultural and early support and prevention programmes within family services, cultural therapeutic groups and cultural events to provide early support and prevent the need for statutory interventions.

5.2.2. Expansion of Community Protecting Boorais, Equitable Funding and Research Opportunities

We aspire to expand Community Protecting Boorais beyond its pilot phase, to expand the limited number of families currently accessing the programme. Not only is the funding for Community Protecting Boorais limited, but funding for the overall Nugel programme is not sufficient to support all Aboriginal children or ensure it is available in all areas of Victoria. We aim to assess the programme’s outcomes to understand how caseworkers enact self-determination in practice and how the programme works for children and families.

5.2.3. Reducing the Number of Children Over-Represented in Child Protection

The future aspiration is that over the next 10 years we would be able to reduce the number of children on statutory orders in care and reinvest into the early prevention programmes—such as cultural support, community involvement and therapeutic interventions. For that to happen, we need the evidence to demonstrate our effectiveness to the government so that they can allocate further investment to the early phases.

5.2.4. Legislation and Data Sovereignty

We are still exercising the authority within significant barriers, including legislative barriers and Government client information systems. This work became possible with the amendments of the CFYA to include S18, but we are still dependent on DFFH’s current information management systems. The current case management system in Victoria is problematic and does not allow us to do the work that we want to, how we want to do it and record it. This means we must implement several administrative workarounds to exercise our statutory decision making. In line with the aspiration of data sovereignty, we aspire for a better shared information system with DFFH.

Furthermore, the vision is to have a standalone Aboriginal Child Protection Act, which will help us work with our Aboriginal families and influence the way that DFFH makes decisions about Aboriginal children.

5.2.5. Agreement-Making and Treaty

We see a standalone Aboriginal Child Protection Act, Treaty and agreement making between the state and Aboriginal peoples as important steps in securing better futures for our children and families and completing the full transformation to an Aboriginal Community of Care. The authority to make decisions about our children and explore how we enact self-determination in practice is likely to be a key part of Treaty conversations and is critical for future policy directions.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Self-determination is critical for improving outcomes for Aboriginal children and families; however, there has not been a lot of exploration about what true self-determination means in practice. That is the work that VACCA embarked upon. This paper explored the work that VACCA has performed, and continues to perform, as we work at the interface with the government to operationalise the aspiration for self-determination. This article discussed how VACCA is navigating statutory decision-making authority with the government, the challenges of doing that and how we took the step to lead and reconceptualise the work. However, VACCA’s Aboriginal Community of Care model is still confined within state demands, limiting Aboriginal self-determination. Therefore, for a true transition from a state-led system of child welfare to an Aboriginal Community of Care model to occur, Treaty in Victoria is required to attend to the unequal power structures and dynamics that contribute to the over-representation of Aboriginal children in care.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed to the publication in the following ways: Conceptualization, K.M., M.B., L.C., K.P., N.R., N.S. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, K.M., M.B.,L.C., K.P., N.R., N.S. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding. VACCA is an ACCO that receives funding from the State Government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was not required because this research did not involve people as participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and appreciate the support and guidance from Paul Gray, University of Technology Sydney, Jumbunna Institute of Indigenous Education and Research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors are committed to serving the interests of Aboriginal children and families.

Notes

| 1 | This article uses the term “Aboriginal” to refer to all First Nations people, as well as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander persons who are living or have lived before or since the start of colonisation. |

| 2 | United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), GA Res 61/295, UN Doc A/Res/47/1 (2007) (DRIP), adopted by Australia on 3 April 2009. |

| 3 | Understanding Story and Stepping in and strengthening safety together are two phases in the Community Protecting Boorais stage of the Nugel Programme. |

References

- Arabena, Kerry, Wendy Bunston, David Campbell, Kate Eccles, David Hume, and Sarah King. 2019. Evaluation of Marram-Ngala Ganbu: A Koori Family Hearing Day at the Children’s Court of Victoria in Broadmeadows; Dandenong: Children’s Court of Victoria. Available online: https://www.childrenscourt.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/Evaluation%20of%20Marram-Ngala%20Ganbu.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Bamblett, Muriel. 2024. Aboriginal Children in Aboriginal Care: A New Approach to Self-Determination in the Care and Protection of Children. Australian Social Work 77: 467–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamblett, Muriel, and Peter Lewis. 2006a. A Vision for Koorie Kids. Just Policy 41: 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bamblett, Muriel, and Peter Lewis. 2006b. Embedding Culture for a Positive Future for Koorie Kids. Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal 17: 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bamblett, Muriel, and Peter Lewis. 2007. Detoxifying the child and family welfare system for Australian Indigenous peoples: Self-determination, rights and culture as the critical tools. First Peoples Child & Family Review 3: 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bamblett, Muriel, Jane Harrison, and Peter Lewis. 2010. Proving Culture and Voice Works: Towards Creating the Evidence Base for Resilient Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children in Australia. International Journal of Child and Family Welfare 13: 98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, Larissa, Amanda Porter, and Alison Vivian. 2016. Indigenous Self-Determination Within the Justice Context: Literature Review. Ultimo: UTS Jumbunna. [Google Scholar]

- Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (Vic). 2005. Available online: https://content.legislation.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-05/05-96aa140-authorised.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2022. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Action Plan 2023–2026; Canberra: Department of Social Services. Available online: https://www.dss.gov.au/system/files/resources/final-first-action-plan.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Davis, Megan. 2019. Family Is Culture: Independent Review of Aboriginal Children in OOHC. Sydney: NSW Department of Communities and Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, Graham, Pat Dudgeon, Clinton Schultz, Angela Hart, and Kerrie Kelly. 2014. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. Edited by Pat Dudgeon, Helen Milroy and Roz Walker. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, David, ed. 1994. The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra: The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC). 1997. Bringing Them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Sydney. Available online: https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/bringing-them-home-report-1997 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Inside Policy. 2020. A Report Prepared by Inside Policy for the an internal report for Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), February 24. Darlinghurst: Inside Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Krakouer, Jacynta, Sarah Wise, and Marie Connolly. 2018. “We Live and Breathe Through Culture”: Conceptualising Cultural Connection for Indigenous Australian Children in Out-of-Home Care. Australian Social Work 71: 265–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libesman, Terri, and Paul Gray. 2023. Self-Determination, Public Accountability, and Rituals of Reform in First Peoples Child Welfare. First Peoples Child & Family Review 18: 81–96. Available online: https://fpcfr.com/index.php/FPCFR/article/view/587 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- McKeown, David. 2010. The Obligation to Act as a Model Litigant. Australian Institute of Administrative Law Forum 28: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Milroy, Helen, Pat Dudgeon, and Roz Walker. 2014. Community Life and Development Programs—Pathways to Healing. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. Edited by Pat Dudgeon, Helen Milroy and Roz Walker. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, B.J., Ilan Katz, Paul Gray, Solange Frost, Yalemzewod Gelaw, Nan Hud, Raghu Lingam, and Jennifer Stephensen. 2024. Restoration from Out-of-Home Care for Aboriginal Children: Evidence from the Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study and Experiences of Parents and Children. Child Abuse & Neglect 149: 106058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, Glenda, and Elizabeth Stubbs. 2023. First Nations Voices in Child Protection Decision Making: Changing the Frame. First Peoples Child & Family Review 18: 5–27. Available online: https://fpcfr.com/index.php/FPCFR/article/view/569 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Rigney, Lester-Irabinna. 1999. Internationalization of an Indigenous Anticolonial Cultural Critique of Research Methodologies: A Guide to Indigenist Research Methodology and Its Principles. Wicazo Sa Review 14: 109–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC). 2024. Family Matters Report. Available online: https://www.snaicc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/241119-Family-Matters-Report-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2009. The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples; Canberra: Government Printers.

- Treaty Authority. n.d. “How the Treaty Authority Performs Its Role”. Treaty Authority. Available online: https://treatyauthority.au/about-us/how-the-treaty-authority-performs-its-role/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Verbunt, Ebony, Joanne Luke, Yin Paradies, Muriel Bamblett, Connie Salamone, Amanda Jones, and Margaret Kelaher. 2021. Cultural Determinants of Health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: A Narrative Overview of Reviews. International Journal of Equity Health 20: 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, Ash, Paul Gray, Belle Selkirk, Caroline Hunt, and Robert Wright. 2024. Attachment and the (Mis)Apprehension of Aboriginal Children: Epistemic Violence in Child Welfare Interventions. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 32: 175–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoorrook Justice Commission. 2023. Yoorrook for Justice Report: Report into Victoria’s Child Protection and Criminal Justice Systems. Parliament of Victoria. Available online: https://yoorrookforjustice.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Yoorrook-for-justice-report.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).