4.1. Chronological Study

Many different disciplines employ chronological study techniques. In their most basic form, information is organized in chronological order throughout a specified period of time—over a period of employment, government service, an artistic career, or a lifetime (

Grasselli 1993;

Clifford 2001). For instance, art historians studying the career of a particular artist might employ a chronological study to detect patterns in the artist’s career and to explain the causes of those changes (

Kitson 1957) while a historical biographer might employ a similar technique to analyze an individual’s motivations (

Rutman and Rutman 1984).

What might the chronological study method offer in cases such as Allen’s? Assembling all known information in chronological order might reveal patterns in property accumulation, geographical movements, and family associations that might provide clues in tracing Allen before he appeared in Walton County records (

Clifford 2001).

To this end, property records, probate documents, census enumerations, and tax digests were studied to trace Allen throughout his residence in Walton Co., GA. Allen is a common surname of British origin most often derived from the given name Allen or Alan, which, in turn, developed from older Gaelic and Celtic words meaning “little rock”, “harmony”, and “handsome” (

Hanks and Hodges 1989). In addition, William is one of the most common British-American given names (

Hanks et al. 2016). Even within Walton County, census data showed that several men with this name lived in the area. The 1830 census showed two men named William Allen living in Walton County, while the 1840 census showed William A. Allen, William Young Allen, William Allen, and Sarah Allen, who was the widow of a fourth William Allen. Even in a comparatively small geographical area, then, several men with the same name lived contemporaneously, and in order to trace this particular William Allen it became necessary to distinguish him from these other individuals (

United States 1830,

1840).

Following this process, a composite portrait of William Allen’s activities in Walton County emerged. Legal documents showed that William Allen lived in Walton County by 1826, when he appeared in the tax digest. Importantly, in that year he paid tax on 250 acres in Land District 1, Land Lot 11, on the waters of Hard Labor Creek, and on land in Henry County, Georgia (

Walton 1826). He also paid tax “as agent for William Tomason”, a potentially significant discovery given the statement by Sams that his first wife was Sarah Thomason (

Walton 1826). Although paying tax as agent for another individual did not necessarily indicate a family connection, most of the time close relatives—siblings and in-laws—represented one another in such matters (

Hudson 1996). The tax digest thus provided two important identifiers—an association with William Thomason and identification of land owned by William Allen himself. The land itself lay within a mile of the boundary between Walton and Morgan Counties, and William Allen seems to have lived in this general area for the rest of his life. He bought and sold additional acreage nearby in 1828 (

Cleveland 1828;

Allen 1828a,

1828b). The 1830 census showed him aged 60–70 years with a wife aged 40–50 and 10 children ranging in age from under five years to a son aged 20–30 years old (

United States 1830). Allen still owned the land on Hard Labor Creek in 1831, when his son Gideon paid poll tax near him (

Walton 1831). He sold land in 1834 (witnessed by Charles Allen, Justice of the Peace) and also appeared in the 1840 census a few miles away, in Allen’s District, when his name was shown as William A. Allen (

Allen 1834;

United States 1840). At that time, he gave his age as 70–80 and his wife’s age as 40–50. The household contained nine children, including four under age 10 who might have been children born in late in life or perhaps grandchildren. Allen sold the land on Hard Labor Creek in District 1 in 1843 (

Allen 1843).

Allen’s wife likely died between 1840 and 1849, for on 11 June 1849 he married Margaret Ritch in neighboring Newton County (

Allen 1849). The 1850 Walton Co., GA, census showed Allen as William A. Allen, age 82, a farmer with

$1200 in property who was born in Virginia. Wife Margaret was 33 and born in Georgia. Shown with the family was Margaret’s son Samuel Ritch, age 5, and born in Georgia (

United States 1850). Allen continued to own land in Land District 1 throughout the 1850s, and he was taxed in Georgia Militia Districts 416 (

Walton 1852,

1853). In addition, as William A. Allen, he sold additional land in 1852 with his son William Y. Allen, Justice of the Peace, as witness (

Allen 1852). He was still living in the area at the time of the 1860 census, which showed him as W. A. Allen, age 100, a native of North Carolina, with property valued at

$4825. Living with him was wife Margaret, now shown as 40 years old, and children Samuel Ritch, age 12, and Nancy Allen, age 8 (

United States 1860). Both age and nativity differed from the 1850 census, but such conflicting information is common in census records and may also reflect a phenomenon called age-heaping by historians and demographers (

United States 1850,

1860;

Fischer 1989).

William A. Allen wrote his will in late 1863. He was deceased by 7 December 1863, when his sons Gideon H. Allen and William Y. Allen posted a

$9000 bond to administer his estate, and an inventory dated 12 December 1863 included five slaves valued at

$6050 along with stock, household furniture, and other personal belongings (

Allen 1863).

This summarizes the contours of Allen’s life in Walton, a period of nearly 40 years out of a lifespan of perhaps a century or more.

From the 1860 census, it would seem that William A. Allen was about 104 years old when he died in late 1863. This corresponds closely to the statement by Sams, although it is possible that she based the information in her book from the 1860 census and probate date of Allen’s estate (

United States 1860;

Sams 1967).

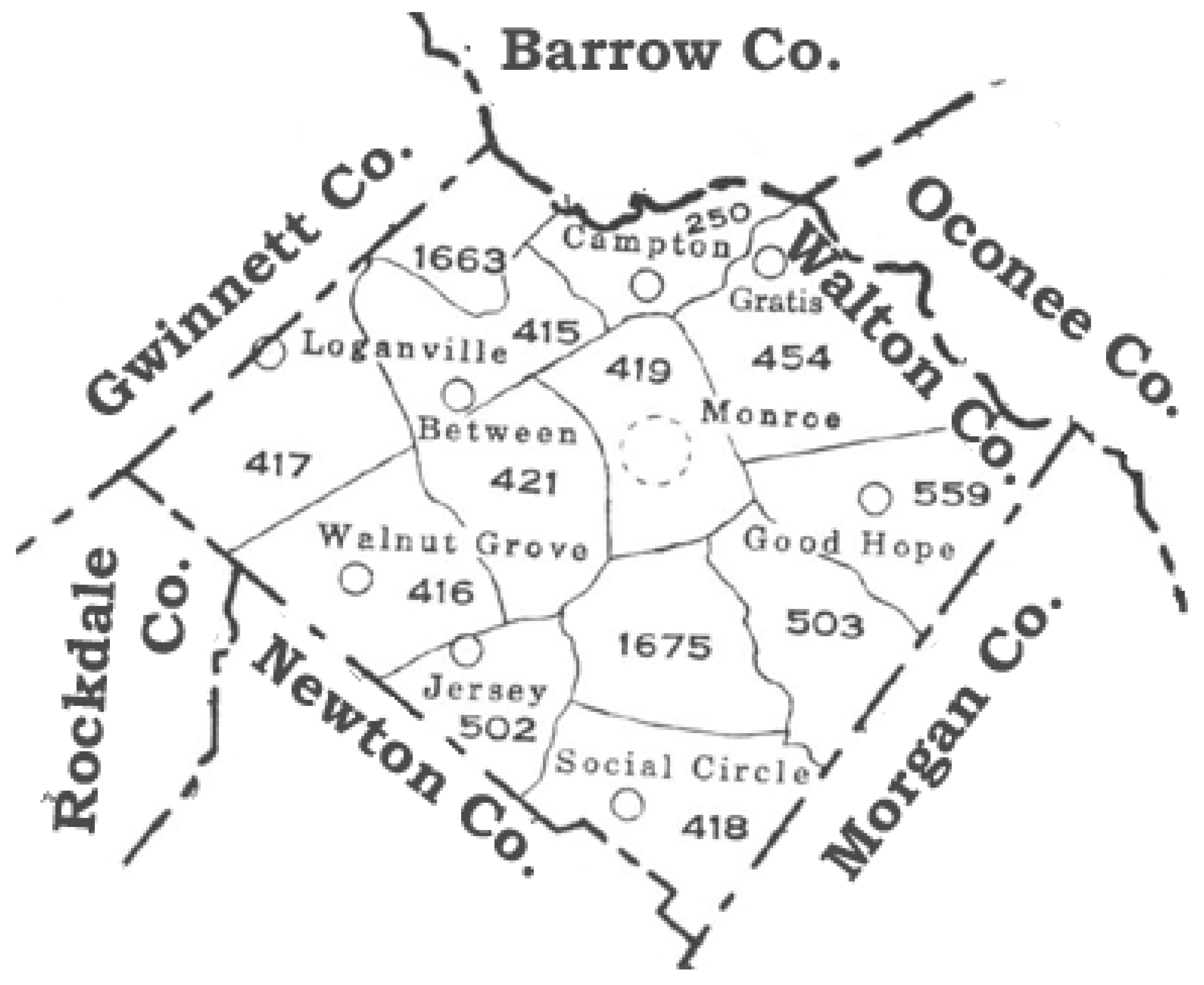

Cumulatively, a chronological study of Allen’s life in Walton County shows that he was in Walton County by 1826, that he owned land and a few slaves, that he lived on Hard Labor Creek near the county line with Morgan County, and that he remained in the area for almost 40 years. Census and tax digests placed him variously in Georgia Militia District 418, located in southwestern Walton County and bordering both Morgan and Newton Counties, and in adjoining Jersey District on the Newton County line. Land and tax records also provided evidence of association with Charles Allen, J.P., and William Thomason, in addition to revealing that his own son William Y. Allen also served as a local justice. The area in which Allen lived was sometimes called Allen’s District, a sign of the family’s importance locally.

Although the life and activities of William Allen during his residence in Walton County come into focus after such a study, the records reveal little that helps document William Allen’s movements prior to his first appearance in Walton County in 1826. Might he have lived in Morgan County as Sams stated, or did he come from elsewhere? To research this, it became necessary to employ a different research method—family reconstitution (

Sams 1967).

4.2. Family Reconstitution

Demographers, historians, and genealogists employ the family reconstitution method when studying particular individuals or groups of people. Through careful analysis, individual family profiles can be documented that identify the parents and children in particular families. This method, heavily reliant on chronological research but with a focus that extends beyond a single individual, has been employed by those studying age at marriage, family size, and age at childbirth, among other issues. Historians such as E. A. Wrigley, Darrett and Anita Rutman, and Lawrence Stone have employed the method as well as organizations like the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, whose York County Project was developed to amass the demographic profiles upon which the foundation’s historical interpretation is based (

Wrigley et al. 1997;

Rutman and Rutman 1984;

Stone 1965;

Manning 2005). The method works best when ample records exist to document births, deaths, marriages, and other relationships. Such records often include parish registers or town records such as those kept in colonial New England, but the method can be used in other situations as well.

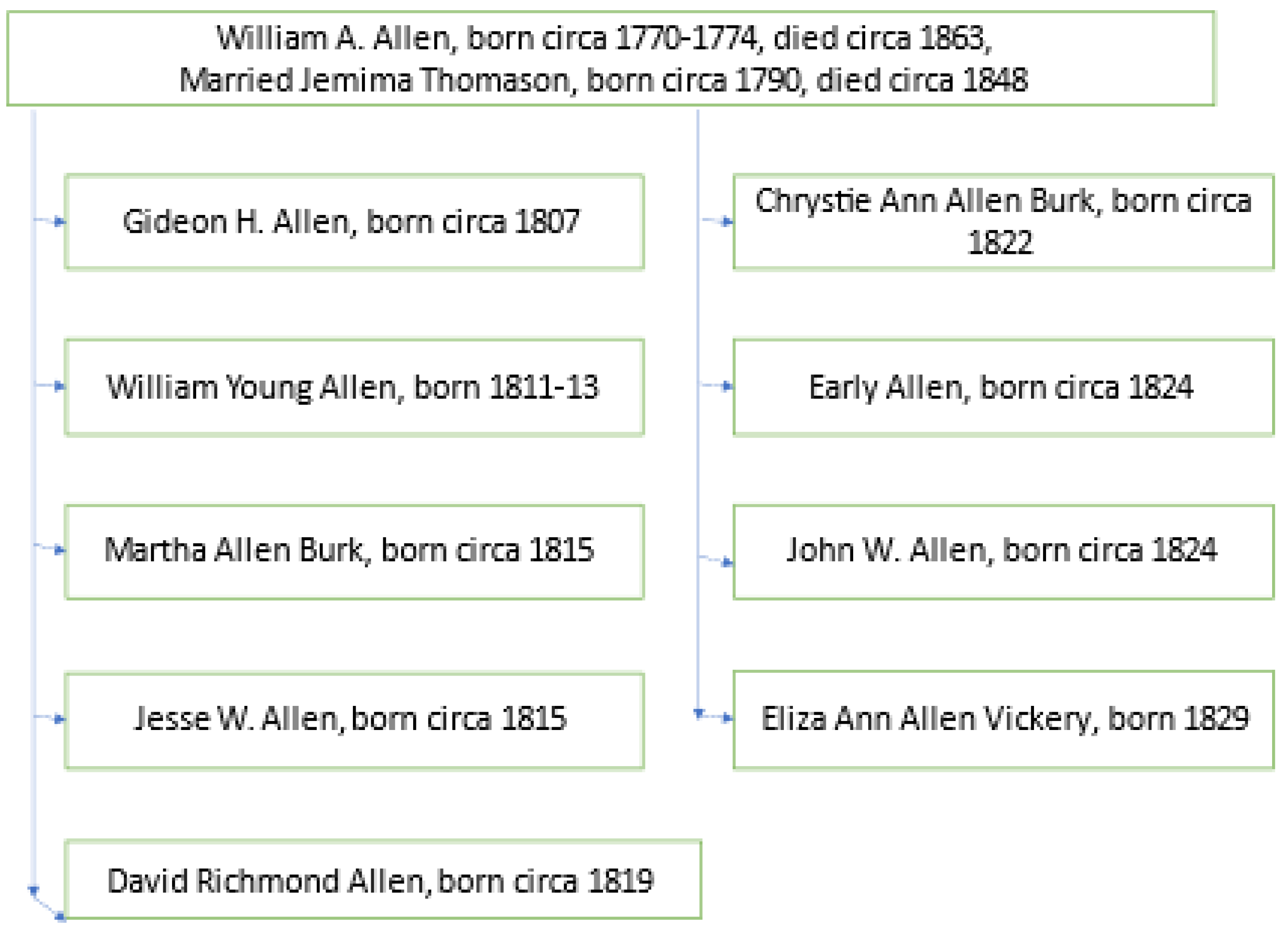

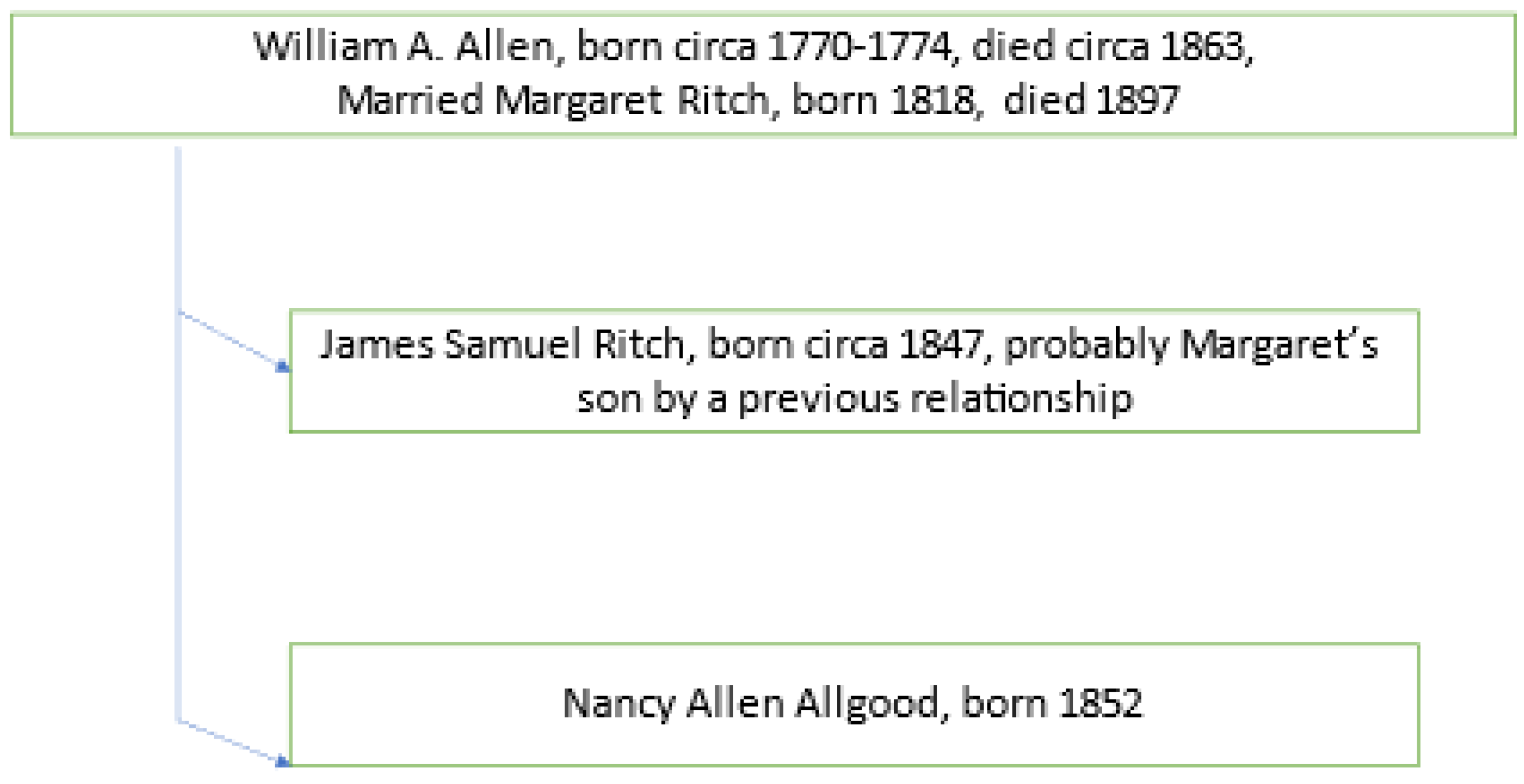

In William Allen’s case, the short sketch provided by Sams named some of his offspring: “His children were Gideon, William Young, Early, John, Jesse, Kittie Ann, Eliza and Linda”. The chronological study of Allen assembled in the previous section supported this list with one exception: no trace of a daughter named Linda was found, although it is possible that she died young or for other reasons did not appear in surviving records. Beyond this, however, the chronological study method indicated that William had a number of other children not mentioned by Sams, and deeds, wills, tax digests, and census records helped identify them. Cumulatively, it appears that William Allen had a large family by his first marriage and at least one child by his second marriage to Margaret Ritch. There is no evidence that, as stated by Sams, Allen married second a “Miss Burke”, but two of his children did marry into the Burke family, which could be the source of that name (

Sams 1967).

Overall, it seems that Allen and his first wife—identified by Sams as Sara Thomason—had Gideon (born about 1807), William Young (born about 1810), Martha (born about 1815), Jesse (born about 1817), David Richmond (born about 1817), John W. (born about 1824), Christie Ann (born about 1822), Early (born about 1824), and Eliza (born about 1829). Christie Ann was apparently the child Sams called Kittie Ann, and the gap in births between William Young and Martha provides a space into which the daughter called Linda might have belonged. If there were children by this marriage after Eliza, their names have not been discovered (

Sams 1967;

United States 1850). As previously noted, William married Margaret Ritch in 1849. She already had a son Samuel Ritch when they married. William and Margaret Ritch Allen had one child, Nancy F. Allen (1852–1937). (See

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). If the age given for William in the 1860 census was correct, William would have been over 90 when Nancy was born (

United States 1860). While this is suspect, documents reveal that she was regarded as his biological daughter, and her paternity seems never to have been questioned within the family. Interestingly, Nancy’s youngest child died in Walton County in 1970, three years after Sams published her work and about 200 years after William Allen’s birth, and may have been the source of the account Sams provided (

Sams 1967;

Findagrave 2013).

Identifying William’s children and their families through the family reconstitution method provided several useful pieces of information that aided in identifying William Allen prior to his arrival in Walton County. First, census records indicated that all of the children were born in Georgia. If correct, this means that William Allen and family lived in Georgia for 20 or more years before he first appeared in Walton County in 1826. This, in turn, means that it should be possible to locate William Allen in Georgia records between about 1806 and 1826, even though he did not appear in Walton County documents prior to that date and could not be clearly identified in other Georgia documents.

More particularly, however, studying the lives of Allen’s children to document their own births and life trajectories led to new and valuable information. Allen himself died during the middle of the American Civil War, and all of his sons lived into that era. Many Confederate service records, pension records, and other documents created as part of the wartime provisional effort contain ages and sometimes birthdates and birthplaces. The true purpose of these records was to document the ages of men eligible for military service, but the records provide a valuable resource for those researching a range of issues (

Eales and Kvasnicka 2000).

Allen’s oldest son Gideon H. Allen appeared in an 1827 Morgan County, Georgia, roster of people eligible to draw in the state land lottery, thus supporting the statement by Sams that William Allen had settled first in Morgan County. Gideon He listed as a “single” man, and lottery requirements meant that as such Allen was at least 18 years old to qualify to draw. Although the list was prepared for the 1827 lottery, the list of eligible individuals was dated September 1825—meaning that Gideon Allen was born in or before September 1807 (

Morgan 1825). In 1864, when Allen was enumerated in a Georgia state census, he also stated that he was born in Morgan County, Georgia (

Georgia 1864). Together, these two pieces of information are critical, for they indicate that William Allen should have been living in the Morgan County area around the year of 1807.

Allen’s son David Richmond Allen served as a Confederate soldier and died while in service on 28 July 1862 of disease at Augusta, Georgia. His age is harder to document than Gideon’s. The 1850 Walton County census indicated that he was 31 years old, which places his birth around 1818–1819. The 1860 Walton census gave his age as 40, indicating a birthdate around 1819–1820 (

United States 1850,

1860,

1861–1865). Following Allen’s death, on 7 March 1863 his widow, Nancy Mayo Allen, signed a “Register of Claims of Deceased Officers and Soldiers” in which she stated that David Richmond Allen was born in “Walton Co., Ga”. An earlier statement, dated 25 July 1862 by James P. Wilkerson, Allen’s commanding officer, relating to Allen’s illness and subsequent death, indicated that Allen was “aged 45 years” and that he was born in “Monroe Co. in the State of Georgia”. Wilkerson’s information would place Allen’s birthdate a bit earlier than reported in census enumerations, about 1817. Nancy’s statement placed his birth in Walton County. Wilkerson’s information seems to place Allen’s birth in Monroe County, a county about 60 miles to the south that was not formed until May 1821. This may seem puzzling, but the county seat of Walton is a town called Monroe, founded in 1818 as the seat of the newly created county. Henderson was completing a pre-printed form that read “born in ____________ in the State of Georgia, aged ___”. Into this he wrote “Monroe Co”. and “45”. It seems likely that he inadvertently wrote “Co”. after the name of Monroe, the county seat of Walton County. If this was so, then taken together the information supplied by Allen’s widow Nancy Mayo Allen and his commanding officer Capt. James P. Wilkerson, along with the census data, suggests David Allen was likely born in Walton County at some point between 1817 and 1820. Although William Allen did not appear in tax or land records at this time, he may have come to the county to visit relatives or prospecting with a view towards future settlement (

United States 1861–1865).

Confederate records for William A. Allen’s son John W. Allen, one of his younger children, also revealed valuable information. Allen—who survived the war and lived for many years afterwards—stated on one document that he was born on 27 December 1824 in Morgan County, Georgia (

United States 1861–1865).

Using the family reconstitution method to identify and document Allen’s offspring thus revealed three particularly valuable pieces of information. The first indicated that Allen’s oldest known son was born about 1807 in Morgan County. The second indicated that Allen’s son David Richmond was born about 1817–1820 in Walton County. The third indicated that Allen’s son John W. Allen was born 27 December 1824 in Morgan County. Information about William Allen’s life and activities in Walton County assembled using the chronological study method revealed that he owned property on Hard Labor Creek in southern Walton County near the boundary with Morgan County, and that many of his neighbors and associates had lived in Morgan County prior to moving into Walton. Morgan was formed by the Georgia legislature on 10 December 1807 from Baldwin County, created in 1805. Land in Baldwin—and thus in future Morgan—was distributed through the 1805 land lottery (

Williams 2018). Walton County was formed in 1818 from Creek and Cherokee lands (

Cooksey 2018). Settlers began moving into both regions at or just before the counties were created, and William Allen may have settled in Baldwin County prior to Morgan County’s formation. He may then have moved into or visited newly created Walton County about the time of David Richmond Allen’s birth but returned to Morgan County, where he lived until at least 1824, before John W. Allen was born. From 1826 onwards, he left a clearly documented trail in Walton County, where he died about 1863.

Returning to the chronological study method, the search refocused on Morgan County records between 1807 and 1824—the years during which information on Gideon, David Richmond, and John W. Allen indicated William A. Allen must have been in the area. Morgan County has an excellent span of early tax digests that cover this entire period, and Georgia law required that white males over age 21 pay poll tax regardless of whether they owned land or slaves. Early Georgia tax digests, when they have survived, thus comprise an important source for studying migration in early Georgia (

Hudson 1996) Every adult white male of taxable age living in Morgan County during this period should have appeared in the tax digests. In addition, Morgan County deeds, wills, and court minutes provide additional documents from this time period. Searching these records showed the presence of at least three adult men named William Allen in Morgan County prior to 1826. One of these was William Allen, husband of Mary Phillips, who died with a will probated in 1816 that identified his wife and children. Another of these was his son, William Allen, Jr., who owned property and often appeared in connection with his mother and siblings.

The third of these was a William Allen who lived on Hard Labor Creek in northern Morgan County between 1812 and 1824. He is probably the William Allen who did not own property but paid poll tax in the area as early as 1809 (

Morgan 1809). By 1812, he had acquired 140 acres in Land District 20, Land Lot 150, located on Hard Labor Creek (which flows through both Morgan and Walton) and joining Noel Nelson, whose family also moved into Walton County and were neighbors and associates of William A. Allen and his children there (

Morgan 1812). This William Allen—who never used a middle initial in Morgan County documents—paid poll tax each year and also owned several tracts of land that help to identify him conclusively throughout his residence in Morgan. One of these was the 140-acre tract on Hard Labor Creek in Morgan County and another was a 250-acre tract on Hard Labor Creek in

Walton County, on which he paid tax in 1822 (

Morgan 1822). Allen sold the 250 acres in Walton County in 1824, while still living in Morgan County, but this may have been the event that precipitated his move into Walton (

Allen 1824). On 5 September 1825, three commissioners returned to the Morgan Co., GA, Inferior Court “the names of persons entitled to draws in the present contemplated Land Lottery in Major John C. Reese’s Battalion”, the district in which William Allen of Hard Labor Creek had lived (

Morgan 1825). Allen’s name did not appear on the list, although several neighbors—including men named David Allen and Charles Allen—and his own son Gideon H. Allen did (

Morgan 1825). Walton County tax records show that William Allen of Hard Labor Creek in Walton County was taxed there in 1826 and appeared regularly thereafter (

Walton 1826). After 1824, William Allen of Hard Labor Creek in Morgan County was not taxed again, although deed records do not show what became of the 140-acre tract on Hard Labor Creek in Morgan.

Comparing the chronological study records from Morgan County with those from Walton County and analyzing both in terms of the critical facts garnered from the family reconstitution method, it seems that William Allen moved into Morgan County around the time it was created. He lived in the area continuously until about 1825, when he moved a couple of miles northward—still on Hard Labor Creek—into Walton County. He remained in Walton County, among friends and associates from Morgan County, for the rest of his life.

The chronological study of Allen’s activities in Morgan County also revealed several key pieces of information. Men named David Allen and Charles Allen lived in the same district of Morgan County as did William Allen of Hard Labor Creek. David Allen never owned property, but he routinely paid poll tax. Charles Allen did own property and later became a Justice of the Peace; at one point he witnessed a legal document for William A. Allen in Walton County (

Allen 1843). Records show that this David Allen was a Revolutionary soldier and was still alive as late as 1827, at which time he drew in the Georgia Land Lottery with eligibility based on his Revolutionary war service (

Houston 1986). The 1812 Morgan County, Georgia, tax digest showed that David Allen paid tax poll tax for himself and also paid tax “as agent for Wm. Allen”. On Allen’s behalf, he paid tax on the 140-acre tract on Hard Labor Creek. This is critical information (

Morgan 1812). Agents were legal representatives for a particular individual who were authorized by them to conduct business on their behalf. They were not necessarily relatives, but they often were (

Hudson 1996). If David Allen had entered the Revolutionary service in 1776 at age 21 or more, this would mean he was likely born in or before 1755. Charles Allen appeared for the first time in the digests paying poll tax in the same district in 1812; this means he was born in or before 1791 (

Morgan 1812). Five years later, in 1817, William Allen of Hard Labor Creek paid his own tax on the 140-acre tract but also paid tax as “Agent of Charles Allen”, who then owned 75 acres of an adjoining land lot, also on Hard Labor Creek and also bordering Nelson’s land (

Morgan 1817). This Charles Allen remained in Morgan County, where he became a leading citizen. The 1850 census showed that he was born in Virginia about 1790 (

United States 1850).

Cumulatively, then, not only did a chronological study of William Allen’s activities in Morgan County place him in the area at the times indicated by the family reconstitution study of William A. Allen’s children, but it also documented his presence through the ownership of land on Hard Labor Creek between 1812 and 1824 and, through association with the same tract of land on Hard Labor Creek, proved that he was the same William Allen for whom David Allen, Revolutionary soldier, paid tax as agent in 1812 and who represented Charles Allen as agent in 1817. Further analysis of these documents suggests that David Allen, born by 1755, might have been the father of Charles Allen, born in Virginia about 1790–1791. William Allen of Hard Labor Creek in Morgan, apparently the same individual as William A. Allen of neighboring Walton County, might have been a brother of David if he was born about 1760 or perhaps a son if he was born nearer to 1770.

One mystery associated with William A. Allen was the inability to place him in the 1820 Georgia census. Although several men named William Allen did appear, no one named William A. Allen was shown. However, the chronological study method, coupled with family reconstitution analysis, suggested that William Allen must have been in Morgan County at this time. In fact, the 1820 Morgan Co., GA, Tax Digest, Capt. Ramey’s District, showed William Allen and Charles Allen (and their neighbor Noel Nelson) all paying tax for land on Hard Labor Creek (

Morgan 1820).

When searching the 1820 Morgan County, Georgia, census equipped with these facts, several pertinent entries appeared (

United States 1820). Prior to 1850, U.S. census enumerations did not list names of every individual in the household but only the head of household’s name and statistical information for those living within. Allen’s neighbors from the tax digest—including Noel Nelson—appeared in Captain Chisholm’s district in the 1820 census. David Allen’s household included one male aged over 45 years, one female aged 10 or fewer years, 1 female aged 16–26, 1 female aged 26–45, and one female aged over 45 years. Charles Allen appeared a few lines later. His entry showed one male aged 26–45 and one female aged 16–26. No children were shown. Immediately after David Allen’s entry, and just before Charles Allen’s entry, came that for William Allen. Due to its relevance, it will be listed in more detail:

3 males aged 0–10 years

1 male aged 10–16 years

1 male aged 16–18 years

1 male aged 16–26 years

1 male aged 26–45 years

No males aged 45 years and over

2 females aged 0–10 years

1 female aged 26–45 years

William Allen was enumerated with a wife, at least five sons, and two daughters (

United States 1820). Based on all the available evidence, this must be the demographic profile of William Allen of Hard Labor Creek in 1820. His age was reported as 26–45 (placing his birth in or after 1775). His wife was aged 26–45, and hence born 1775–1794. The male aged 16–26, who was probably the same male aged 16–18, is not identified and might have been an older son who died young. The male aged 10–16 (born 1804–1810) fits to be Gideon H. Allen, born about 1807. The males aged 0–10 (born 1810–1820) fit to be William Young Allen (born 1811–1813), Jesse Allen (born c. 1815) and David Richmond Allen (born c. 1819). The two females born 1810–1820 fit to be Martha (born c. 1815) and Linda, the daughter identified by Sams. Ages in historical documents can be wrong, and census records are often inaccurate. Historical demographers write about a process called age heaping whereby individuals often overestimated their ages, usually in particular ways that contrast with the modern-day youth culture. Historian David Hackett Fischer has written about a process he called “veneration of the elderly” that may have been responsible for this (

Fischer 1989). William A. Allen, for instance, had been shown as 83 in 1850 and 100 in 1860 (

United States 1850,

1860). The 1820 census would suggest that he was somewhat younger, possibly born around 1775 (

United States 1820). This is further supported by poll tax records, for while white men over age 60 became exempt from poll tax in 1826, William Allen continued to pay that tax for several additional years (

Georgia Archives 2022).

To summarize, the family reconstitution method provided helpful information. Specifically, it indicated that Allen had lived in Georgia between about 1807 and 1826, before he appeared in Walton County. More specifically, it indicated that he had lived in Morgan County about 1807, in Walton County about 1818 or 1819, and in Morgan County about 1824. This method also produced the names and demographic profiles of Allen’s known children. Since this suggested that Allen had lived in Morgan County during most of the period before he appeared in neighboring Walton County, chronological studies of men named William Allen who lived in Morgan County during this period were developed. At least three such men were identified. Two of these, William Allen who died in 1816 and his son William Allen, Jr., were eliminated because historical documents clearly showed that they were different individuals. This left William Allen of Hard Labor Creek. A chronological study of this man fits perfectly with known facts from the chronological study of William A. Allen of Walton County. Moreover, it agreed with the family profile developed using the family reconstitution method. In addition, valuable data emerged to suggest a connection between William A. Allen—whose birth the 1820 census placed around 1775—and David Allen, a Revolutionary soldier probably born before 1755, and Charles Allen, who was born about 1790–1791 in Virginia. This suggested a valuable path for further research, although Allen’s life and activities prior to first appearing in Morgan County, Georgia, around 1809 remained completely unknown.

4.3. Community Study

Interestingly, the chronological study of William A. Allen’s activities in Walton County revealed that he had paid tax for William Thomason in 1826. This was significant because of the statement by Sams that William A. Allen had married Sarah Thomason. William’s role as agent hinted at the possibility, still to be explored, of a family connection. Research on this William Thomason, also using the chronological study method, indicated that he was born prior to 1760 and that he had lived in Laurens County, South Carolina, before moving to Georgia. William Thomason and Bartlett Thomason were both taxed in Walton County in 1819, and the 1820 Walton County census showed Bartlett aged 26–45 and William aged above 45 years (

Walton 1819;

United States 1820). While it is speculative at this point, if a pre-existing family connection existed between William Allen and William Thomason by virtue of Allen’s putative marriage into the Thomason family, this might explain why Allen went into Walton County—where Bartlett and William Thomason had settled—about 1819–1820, a date that coincides with the statements placing David Richmond Allen’s birth in Walton County about this time (

Sams 1967;

United States 1861–1865).

This analysis suggests the value of looking more broadly at wider associations within the local neighborhood to better understand the historical community in which a given individual lived. As a historical methodology, the community study flourished in the 1970s as part of the “new social history”. The methodology derives in part from historical sociology in the early 20th century that looked at community studies as a means of understanding contemporary issues and the problems that generated them. An early example is Louis Wirth’s

The Ghetto (

Wirth 1928), while William Foote Whyte’s

Street Corner Society: The Structure of An Italian Slum (

Whyte 1943) became a classic ethnographic study of a modern urban neighborhood. The method has also been employed by anthropologists, whose work has extended beyond the confines of the physical community to the process called community development and recognizable today by those who identify as part of a particular “community” regardless of location (

Schwartz 1981).

Within the historical field, many classic community studies appeared in the 1970s and 1980s that borrowed from anthropological and sociological methodologies as well as from other social sciences. Kenneth Lockridge’s

A New England Town examined Dedham, Massachusetts, from its inception in the early days of New England until its fragmentation and decline more than a century later (

Lockridge 1970). Boyer and Nissenbaum, in

Salem Possessed, found the roots of the outbreak of witchcraft accusations at Salem in the early 1690s in social and economic tensions that had developed decades earlier (

Boyer and Nissenbaum 1974). Darrett and Anita Rutman applied this method profitably to a different type of community, the southern county, in their study

A Place in Time: Middlesex County, Virginia (

Rutman and Rutman 1984). In addition, John Demos has brilliantly utilized the methodology in his numerous works, including

Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England (

Oxford, Demos 2004). In this work, Demos employed a mixed method analysis of his own that drew insights from biography, sociology, psychology, and history. His essay on Lawrence and Rachel Clinton (“A Desolate Condition”) involved aspects of chronological study, family reconstitution, and community analysis. Sociological and anthropological modes of analysis strongly influenced his case studies of communities in New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Long Island, along with a more comprehensive overview titled “Communities: The Social Matrix of Witchcraft” (

Demos 2004).

The central relevance of these works to this study is the premise that to understand fully the social world in which historical actors functioned it is necessary to look at the broader communities of which they were a part. Individuals, even those on the most remote frontier regions, were not solitary actors. They were usually part of physical communities—such as the loose “neighborhoods” the Rutmans examined in Middlesex County, Virginia—and players within intersecting webs of relationships (

Rutman and Rutman 1984). In addition, they were sometimes part of imagined communities such as those described in Benedict Anderson’s classic study. This might include affiliation with political, religions, military, or educational organizations (

Anderson 1983).

What might this approach contribute to studying individuals such as William A. Allen? This article has shown that the chronological study method and the family reconstitution method document and analyze an individual’s life from the micro perspective of her or his individual activities and the development of a very intimate community, the family. How did an individual such as Allen fit into the wider community, and how might that play a role in identifying him and tracking his historical origins? The community study method and related techniques focusing on social network analysis and cluster analysis can provide answers (

Mills 2012a,

2012b,

2012c;

Hatton 2021).

A partial response has already been suggested through utilizing the chronological study methodology. Studying William Allen’s life in Morgan and Walton Counties revealed that he owned land along Hard Labor Creek and that when he moved from Morgan County into Walton County he continued to live along Hard Labor Creek. Throughout the colonial and antebellum south, watercourses were important sites of transportation and also association since the local water supply was vital for agriculture and livestock. In this sense, they played a role comparable to that of “the road” critical in the Rutmans’ study of Middlesex County (

Rutman and Rutman 1984). As has already been noted, many of the same families from northern Morgan moved into southern Walton about the same time as William Allen did, including the family of Noel Nelson, who were his neighbors in both locations.

Beyond local geographical features like rivers and mountains that shaped access and helped determine patterns of local association, in antebellum Georgia the two important jurisdictions were the county and the militia district. Officials such as the sheriff and Superior and Inferior Court justices were elected or appointed at the county level. Each county as divided into several militia districts, each of which was headed by a district captain. This practice dated to the days of the colonial, and later state, militia that was necessary for local defense, and long after the local militia ceased to exist, the Georgia Militia District organization structure still exists today. Tax digests, census enumerations, poor school distributions, and a host of other functions were divided by militia district, and each district had one or more justices of the peace who could perform marriages and assist with other legal business (

Hitz 1956). In Morgan County, Allen lived in Georgia Militia District (hereafter GMD) 283, which borders Walton, while in Walton County he lived first in GMD 503, known as Blassingame’s District and bordering Morgan County’s GMD 283, before moving northwest into GMD 502—known as Allen’s District—and GMD 416, known as Broken Arrow. Although four different districts were involved, it is important not to overestimate the geographical distance. The location of the Hard Labor Creek tract where Allen lived from about 1812 to 1824 is only about 14 miles from the location of the land near the boundary of districts 502 and 416, where Allen lived at the end of his life in 1863, and many of the same families resided throughout these districts. (See

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.)

A key feature of life in this region was the high geographical mobility. The land that formed Morgan County was not open for settlement until 1805, and that that formed Walton County was not opened for settlement until 1818 (

Cooksey 2018;

Williams 2018). Many families stayed only a few years before moving elsewhere, but a core group of families remained in the area and continued to associate for generations as suggested by legal documents and census records. Examining these associates provided insight into the migration paths that brought many of Allen’s neighbors and associates into the area.

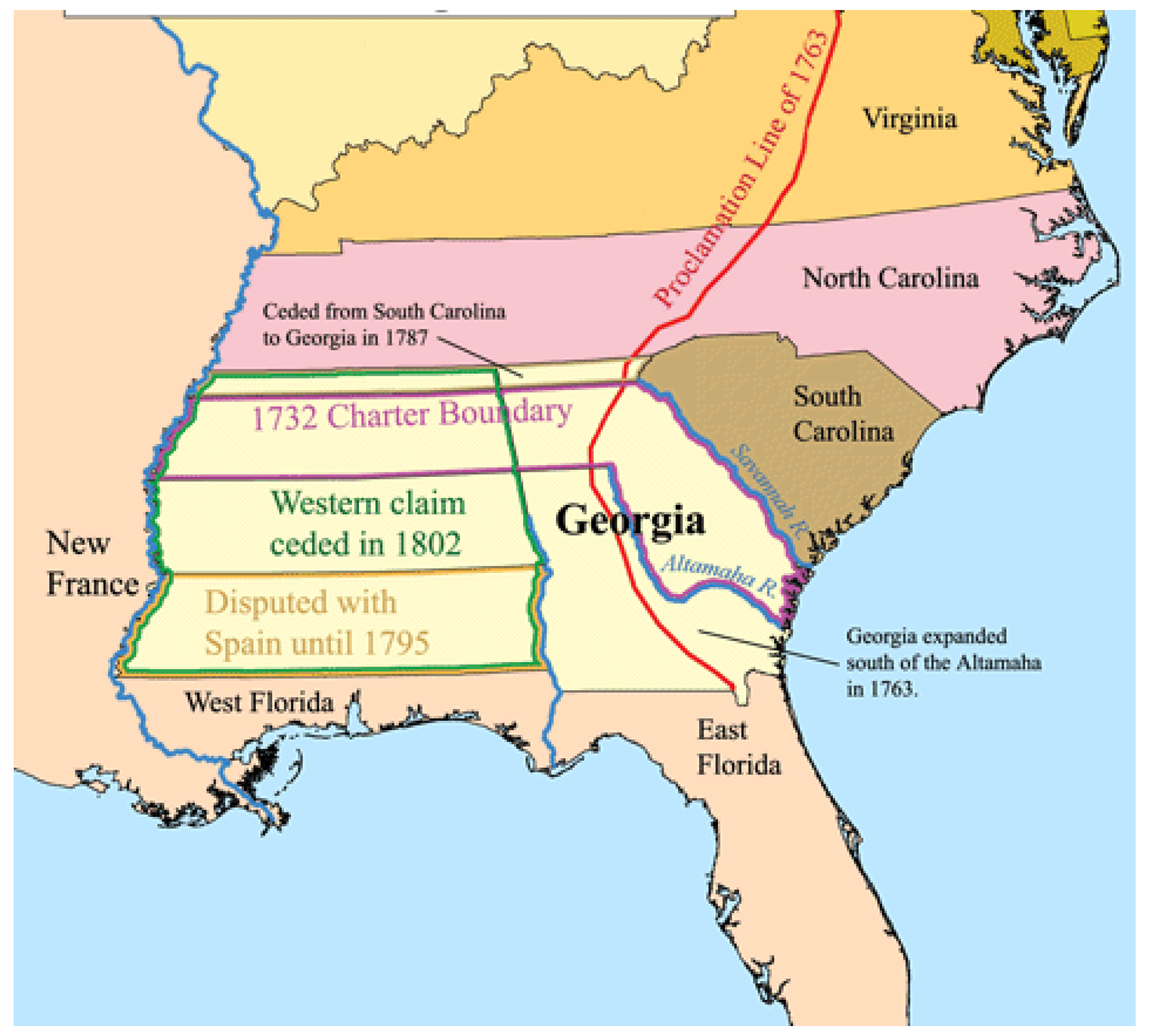

One group of local families seemed to have moved into Walton County about the time of its settlement from Laurens County, South Carolina. (See

Figure 7) Many of these families had begun to appear in neighboring Jackson County, Georgia, in the early 1800s, and the pace of migration quickened as new territory opened in Walton and adjoining counties. These included the families of Isaac Dial (1791–1864), who married Sarah Thomason (1792–1847); Martin Dial (c. 1789–1842), who married Jane Eastwood; and John Dial (c. 1782–c. 1860), who married Christie Thomason. The Dials and Thomasons had both settled in Laurens County, South Carolina, prior to 1790, along with a number of other families that moved into northern Morgan and southern Walton Counties in the 1810s and 1820s. In the next generation, Mary Ann Dial and her sister Jane Dial, daughters of Martin Dial and Jane Eastwood, married Jesse W. Allen and Early Allen, sons of William A. Allen. Their cousin Chrystie Dial married William Young Allen, another of Allen’s sons. In addition, Nancy Allen, William Allen’s youngest daughter, later married John W. Allgood, whose mother Lucinda Dial was a daughter of Isaac Dial and Sarah Thomason. Other associated families, such as the Abercrombies and Studdards, followed the same path. This migration pattern suggested the possibility of a prior connection to Laurens County, South Carolina, particularly if William A. Allen had married into the Thomason family before settling in Georgia. If so, that pre-existing connection may have played a role in the migration of one or both families into the Morgan-Walton County area (

Sams 1967).

Not all associated families followed this migration pattern, however. Several had no association with Laurens County, but, instead, had come directly to Georgia from Southside Virginia, a group of counties lying south of the James River. Most of these families came from the Piedmont counties west of the fall line. For example, Charles Allen—the Justice of the Peace and neighboring landowner for whom William Allen paid tax—may have married a daughter of Sarah Willard, with whom he was associated in several legal documents. Sarah and her husband Nixon Willard had married in Prince Edward County, Virginia, and lived there for several years before moving to Georgia in the early 1800s. The other William Allen of Morgan County, who died in 1816, had lived in Pittsylvania County, Virginia, for more than a decade before moving to Wilkes County, Georgia. James Malcom, a prominent local attorney and planter who was also an Allen associate, had been born in Albemarle County, Virginia, and had lived in Buckingham and Charlotte Counties before settling in Wilkes County, Georgia, around 1790. Woodson Allen, a Revolutionary soldier who also lived in Allen’s District of Walton County, had married Annis Palmer in Charlotte County, Virginia, and appeared variously in Powhatan, Prince Edward, Pittsylvania, and Buckingham Counties in the Southside before he moved to Clarke County, Georgia, about 1802. Noel Nelson, longtime neighbor and associate, had also lived in the region prior to 1790. This migration pattern suggested the possibility of a prior connection to Southside Virginia, particularly since William Allen reported in 1850 that he was born in Virginia, as did Charles Allen of Morgan County (

Sams 1967) (Beyond this reference, information in this paragraph is summarized based on other primary sources cited throughout the essay, which were also consulted for the individuals discussed here).

In researching Allen’s neighbors and associates, particular attention focused on families like the Thomasons and Dials, who seem to have had a close relationship with William A. Allen. This approach, influenced by the genealogical principle of examining friends, family, associates, and neighbors (

Mills 2012a,

2012b,

2012c), had added significance given the statement by Sams that Allen married Sarah Thomason. The Thomason—Dial migration to Georgia seems to have begun after 1814, and this further suggested that, if Sams was correct, any connection between the two families likely predated their settlement in Georgia (

Sams 1967).

One excellent source for tracking migrations during this period are Revolutionary War Pension applications. It is important to remember when working with historical records that they were created for a specific purpose; the information modern researchers derive from them was often generated incidental to the original purpose for which they were created. Revolutionary War Pension applications existed to prove that an individual had fought on the patriot side in the American Revolution. To do that, individuals or their families needed to document their military service and whatever family relationship might entitle them to a pension based on that soldiers’ service. This often involved proving an individual’s age and family relationships to show that that person was old enough to have fought in the Revolution or that a claimant was the widow or a minor child of a deceased soldier. Often supporting affidavits were filed by individuals who had been fellow soldiers or who otherwise had pertinent information that supported a particular claim (

Nudd 2015).

For many years, these records could only be viewed on microfilm or accessed remotely through contacting the National Archives. Now fully digitized, they can be viewed digitally. In addition, the Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters has partially transcribed thousands of pension applications for soldiers who fought in the southern campaigns. This includes the lengthy applications as well as selected supporting statements from friends, relatives, former neighbors, and other associates. Since many soldiers later moved from their original places of service, these files contain valuable information about the migration of individuals after the Revolution. Now fully searchable online, these transcriptions make it possible to locate information not previously accessible (

Graves and Harris 2022).

As part of the research strategy for studying the migrations of Allen’s neighbors and associates from the local community, the author searched these files using various keyword combinations involving the surname of an associated family and the location of the two later counties of residence, Morgan and Walton. A search for the Allen surname in these locations revealed nothing relevant, but a search for the Thomason surname revealed a potentially relevant deposition from an individual named

Sarah Thomason of Walton County, Georgia. Given its significance, it is quoted a length. This record appeared in the file of Elizabeth Thompson, widow of Flanders Thompson, who was seeking a Revolutionary War pension based on her husband’s alleged service in South Carolina. Thompson turned to a friend from her youth, Sarah Thomason, whom she had known prior to her own marriage and who, she thought, might have valuable information support of claim to be Flanders Thompson’s widow. Sarah’s statement appeared in the transcribed pension file in this way:

On 4 September 1846 in Walton County Georgia, Mrs. Sarah Thomason, 81, gave testimony that she removed to Lawrence District South Carolina previous to the Battle at Cambridge (commonly called Ninety Six) in the time of the Revolutionary War; that she removed to the immediate neighborhood of one David Green who was a Minister of the gospel and was very intimate with the family for many years; that soon after the revolutionary war, Flanders Thompson came into the neighborhood and became engaged to marry Elizabeth Green, daughter of said David Green; that David Green opposed the marriage of his daughter to Flanders Thompson; that the couple eloped and were married she believes in the year 1783 or four; that Elizabeth and Flanders were married before affiant was married in 1784; that affiant was acquainted with several of their children viz. Henry Thompson their oldest child, Polly was their youngest and five between them viz. Leana, Joel Green, John, Flanders, Jr., and Temperance. She signed her affidavit with her mark.

This was the only statement in the transcribed file of any possible relevance to the research undertaken on William A. Allen, but it revealed the intriguing clue that an elderly woman named Sarah Thomason, born about 1765, had lived in Laurens County, South Carolina, about the time of the American Revolution and that she was living in Walton County, Georgia, in 1846, when William A. Allen and family also lived there (

Thomason 1846b).

On its own, this information supported the general migration of families from Laurens Co., SC, to Walton Co., GA, but it contained little useful information beyond the coincidence of names and locations. Since many transcriptions often omitted documents or statements not deemed critical by those transcribing the files, the author examined the handwritten pension file. This proved revealing. The file not only contained additional statements by Sarah Thomason, but it also contained a deposition by her daughter Jemima Allen and a statement by William A. Allen himself. These statements were not noted in the published transcriptions as they were deemed of no material value to documenting the Revolutionary service of Flanders Thompson, but they hold great value in terms of identifying the background of William A. Allen.

Altogether, more than a dozen statements appeared by members of the Allen, Dial, and Thomason families. These deponents all stated that they had known the Flanders Thompson family in South Carolina. In the process of providing that information and explaining how they had acquired it, those deposing provided critical facts about the Allen and Thomason families. A summary of key facts from the depositions appears below:

Sarah Thomason stated on 4 September 1846 that she was about to turn 81 in October 1846, as per her best information. This would place her birthdate in October 1765.

Sarah Thomason gave another statement on 3 February 1848 wherein she stated “that she was eighty three years old on the 22d day of October last year”. This would place her birthdate on 22 October 1764.

Sarah Thomason stated on 4 September 1846 that she removed to Lawrence District South Carolina previous to the Battle at Cambridge (“commonly called 96”) in the time of the Revolutionary War. Sarah did not give her maiden name of place or birth. The Battle of Cambridge took place 19 November 1775.

Sarah Thomason stated on 4 September 1846 that Flanders Thompson and Elizabeth Green married she “believes in the year One thousand Seven hundred and Eighty three or four that the said marriage took place previous to the time that deponent was married and that she deponent was married in the year 1784 according to her calculations and belief”. In this statement, Sarah placed her marriage date in 1784.

On 3 February 1848, Sarah Thomason stated that the marriage of Flanders and Elizabeth Thompson “took place about sixty six years ago from the age of her oldest child who is now about sixty five years old”. It is not clear whether this refers to Sarah’s oldest child or Elizabeth’s oldest child. If the former, it could mean that Sarah married as early as 1782.

On 4 September 1846, Henry Haralson, a Justice of the Peace, stated that “Sarah Thomason is from all appearances the age she represents herself to be and a person of very good intelligence considering her age Reads Print But has never been taught to write”.

On 4 September 1846, “Jemima Allen of said County Daughter of the aforesaid Sarah Thomason” also gave a deposition in Walton County. She “saith that she has no record of her age But from what she has always understood is upwards of fifty-six years of age and was Born in Laurens District South Carolina that she knew the aforesaid Flanders Thompson and Elizabeth Thompson of the same place and was school mates with their children Henry & Leana their two eldest was older than deponent and was considerably larger…” This means that Jemima Allen was a daughter of Sarah Thomason. Further, it places Jemima’s birthdate between 4 September 1789 and 3 September 1790 and her birthplace in Laurens District, South Carolina.

On 3 September 1846 Isaac Dial stated that he was “aged sixty three years past” and a former resident of Laurens District, SC. He stated that he was “personally acquainted with Sarah Thomason now a resident of Walton County from and before his first recollections and grew up playmates with her eldest children which were about the age of deponent”. He also stated that Henry Thompson, eldest reputed son of Flanders and Elizabeth, was about the same age as himself. From his own knowledge, he believed that Sarah Thomason’s statements about the wedding of Flanders and Elizabeth Thompson “are correct”. This means that Isaac Dial was born between 3 September 1782 and 2 September 1783 and that Sarah Thomason’s eldest child was born about the same time.

On 3 February 1848, the same date as Sarah Thomason’s second deposition, William A. Allen gave a deposition. He appeared before Thomas Mobley, Justice of the Peace, who stated: “Personally appeared before me an acting justice of the Peace in and for said County William A. Allen well known to me as a credible person and after being duly sworn according to law deposeth & states that he is in his eightyeth year and was well acquainted with Flanders Thompson and his wife Elizabeth in Laurence District South Carolina that they were living together as husband & wife when he moved into Laurence District S. C. fifty two years ago and never heard their marriage questioned or doubted…” If correct, this places William A. Allen’s birth between 3 February 1768 and 2 February 1769. It also indicates that he moved into Laurens County, South Carolina, in 1795 or 1796 (prior to 3 February 1796, 52 years earlier).

On 3 February 1848 Thomas Mobley stated: “I have been acquainted with Mrs. Sarah Thomason and Mr. William A. Allen a number of years and have never heard their veracity questioned therefore I consider their statements entitled to full credit and faith”. The linkage of William A. Allen’s statement and Sarah Thomason’s statement by Thomas Mobley suggests that they had probably come into court together or that Thomas Mobley himself had visited the Allen home. This is further supported by the fact that Allen’s son, Early Allen, witnessed Sarah Thomason’s deposition.

On 26 January 1849, Isaac Dial gave an additional statement that “he has been well acquainted with Mrs. Sarah Thomason of this neighbourhood from his earliest recollection and knows her to be a person whose statements are entitled to full faith and credit whose reputation as a member of the Church stands as fair as any for piety and whose recollection is very good for a person of her extreme old age”.

Sarah Thomason, the deponent, was the widow of William Thomason, the person for whom William Allen had paid tax in 1826 (

Walton 1826). Cumulatively, these statements indicate that Sarah was born somewhere other than Laurens District, South Carolina, on 22 October 1764 or 1765. She moved to Laurens County, South Carolina, prior to 19 November 1775 and knew Elizabeth Green, who was about the same age, prior to her marriage to Flanders Thompson, a Revolutionary soldier who was born in Halifax County in Southside Virginia. Sarah married William Thomason between 1782 and 1784 and had her first child soon afterwards. Sarah’s own marriage took place shortly after the marriage of Flanders and Elizabeth Thompson, and the Thomason children and the Thompson children were about the same age. Sarah’s daughter Jemima Thomason—born between September 1789 and September 1790—was a playmate of the third and fourth Thompson children. Isaac Dial, born about 1783 and the same age as the oldest Thompson and Thomason children, grew up knowing both families; he later married Sarah Thomason (1792–1847), a daughter of William and Sarah Thomason. Dial recognized his mother-in-law for her “piety”, “credit”, and “reputation” (

Allen 1846,

1848;

Dial 1846,

1849;

Thomason 1846a,

1848).

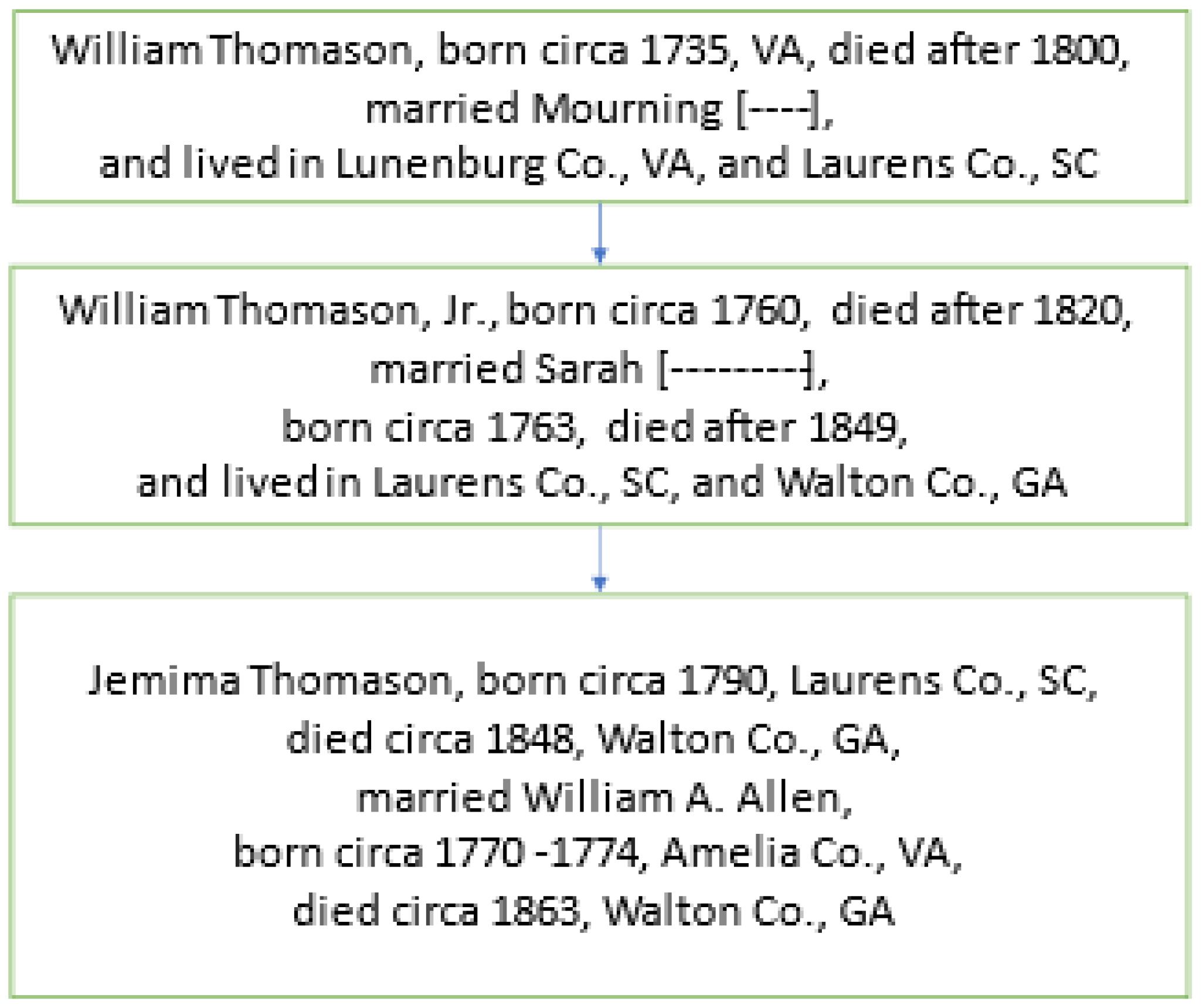

Although not specifically stated, the documents certainly imply that William A. Allen had married Jemima Thomason, the daughter of William and Sarah Thomason. (See

Figure 8) Jemima was born in Laurens District between September 1789 and September 1790 and was still alive in Walton County on 3 September 1846. William Allen’s deposition places his birthdate between February 1768 and February 1769 and suggests that he was younger than shown in the 1850 or 1860 census although slightly older than indicated in the 1820 census (

Allen 1846,

1848). Although his place of origin was not stated, he had moved to Laurens District from elsewhere about 1795. Jemima Allen, born about 1789–1790, would have likely been 17 or 18 when William Allen married her, and they must soon have moved to Morgan County, Georgia, where son Gideon Allen was born about 1807 or 1808. Their son Early Allen, born about 1824, witnessed his grandmother’s signature in February 1848 (

Thomason 1848). It is notable that only one deposition from Jemima Allen appeared. In the second instance, a deposition from William A. Allen replaced hers. One possible explanation is that Jemima had recently died or was ill; further support for this comes from William A. Allen’s remarriage to Margaret Ritch on 7 June 1849. From a subsequent statement by Isaac Dial, it would appear that Sarah Thomason was still alive on 26 January 1849 in Walton County, Georgia (

Dial 1849).

Thus, the need to verify the marriage date of Elizabeth Green and Flanders Thompson in order to support Elizabeth’s claim to a widow’s pension based on her husband’s Revolutionary War service generated a host of documents that ultimately confirms several key facts concerning William Allen and his family. The 1800 Laurens County, South Carolina, census provided additional information that supports these depositions. Living in the district commanded by Capt. William Owens at the time were William Thomason, Jr.; William Thomason, the younger; John Thomason, Sr.; Martin Dial; John Dial; William Thomason, Sr.; John Thomason; David Allen; and Flanders Thompson. The census seems to have been taken in roughly residential order. David Allen’s name came nine lines after that of William Thomason, Sr., two lines after that of John Thomason, and five lines before that of Flanders Thompson (

United States 1800).

The enumeration for David Allen showed in his household two males under age 10; one male aged 16–26; one male aged 16–26; 1 male aged over 45 years; one female under age 10; and one female aged 16–26 (

United States 1800). This fits with the demographic profile for the family of David Allen in Morgan County, Georgia, and could have included Charles Allen, born about 1791 in Virginia, as well as another son, whose name may have been John. William A. Allen would likely have been the son aged 16–26 and hence born 1774–1784, a date more consistent with the 1820 census entry and less in line with what seems a tendency later in life to exaggerate his age.

To summarize, the community study method indicated that William A. Allen lived within a fairly small geographical area—stretching at most about 14 miles—between about 1809 and his death in 1863. Although many families came and went during this period, a core group of families with whom Allen and his children associated closely over many years remained. Some of these families were recent arrivals from Laurens County, South Carolina, who had moved to Georgia after about 1815—possibly in connection with the state’s geographical expansion and a wanderlust enhanced by the recent War of 1812. Others had come to Georgia around the turn of the century from the Virginia Southside, Charlotte, Buckingham, Cumberland, Powhatan, and Prince Edward Counties.

More detailed research into the particular families with whom Allen associated produced evidence that Allen had come to Morgan County from Laurens District, South Carolina, where he likely moved with his father David and siblings from Virginia about 1795. The migration trail followed by Flanders Thompson from Halifax in the Virginia Southside to Laurens suggests a possible route that Allen may have taken. The Thomasons had traveled a similar route when moving to Laurens County from Lunenburg County, Virginia, a generation earlier.

Allen seems to have married Jemima Thomason, daughter of William and Sarah Thomason, about 1806 or 1807 and to have moved to Morgan County, Georgia, shortly afterwards. About 1818–1819, just as Walton County was being settled, William and Sarah Thomason and their son Bartlett, along with a host of in-laws—including Isaac and John Dial—moved to southwestern Walton County, Georgia. In the tradition repeated by Anita Sams, the names Sarah and Jemima seem to have been confused. Allen’s wife was apparently Jemima Thomason. Jemima’s sister Sarah married Isaac Dial. The name “Sarah Thomason” recalled by family members and repeated by Sams was apparently that of family matriarch Sarah Thomason (c. 1764–1849), whom her son-in-law Isaac Dial described in 1849 as “a person whose statements are entitled to full faith and credit whose reputation as a member of the Church stands as fair as any for piety and whose recollection is very good for a person of her extreme old age”. The names of several of the Thomason children, including Gideon and Christie, were names commonly used in the Thomason family and names that appeared frequently in Southside Virginia (

Sams 1967).

Joined with the chronological study and family reconstitution methods, then, the community study method provided a useful tool that facilitated research on William A. Allen and helped to identify his marriage to Jemima Allen and his residence in Laurens County, South Carolina, prior to settling in Morgan County, Georgia. Alone, none of these methods would have been sufficient to identify Allen convincingly. Together—by tracing Allen’s movements first between 1826 and 1863 in Walton County and, after the family reconstitution method indicated prior residence from 1807 to 1824 in Morgan County, there as well—and then by examining neighbors and associates in the wider community in which he lived for nearly 60 years—they identify the contours of a profile. Allen may have been born as early as 1768 and possibly as late as 1775. He likely was born in Virginia, as indicated in his own 1850 census enumeration and that of his probable brother Charles, and as suggested by the broader migration pattern of neighbors and associates in both South Carolina and Georgia from the Virginia Southside. In addition, his father may have been a Revolutionary soldier named David Allen who was born prior to 1755.

4.4. One-Name Study

Although promising, the information located thus far still did not pinpoint William Allen’s origins or background prior to reaching Laurens County, South Carolina.

For that, a fourth method was employed—“the one-name study”. British researchers pioneered the “one-name study” approach as a means for tracing families across the centuries. Although the British Isles are small geographically, high population density and a long history has meant extensive migration both locally and throughout Britain. It is not uncommon for British researchers to discover, for instance, that a family living in Oxfordshire in the 19th century had roots in Norfolk in the 16th century, or that a South London family moved there from Cumberland centuries earlier. For modern researchers, Y-DNA analysis can provide a genetic clue to the origins of particular surnames, but in Britain—because of several factors, including regional migration within Britain, outmigration throughout the British empire, the extinction of the male line in many families, and the complex and varied history of surname development itself, Y-DNA analysis—itself a very modern tool—is sometimes of limited utility. British researchers continue to actively employ the one-name study approach to trace surname development and family origins as well as to use it as an interpretive tool to help understand DNA findings (

Adler 2002;

Palgrave 2008;

Guild of One-Name Studies 2022).

The one-name study method involves locating all references to a particular surname in a particular geographical area. This might include examining deeds, wills, marriages, parish register entries, and census enumerations. In Great Britain, the Guild of One-Name Studies, an organization dedicated to this approach, fosters and promotes the methodology (

Adler 2002;

Palgrave 2008;

Guild of One-Name Studies 2022).

The approach used here is not a full one-name study since the first three research methods employed already revealed information that might help to identify William Allen’s origins but an abbreviated one-name study of more limited dimensions. Records from Morgan Co., GA, and Laurens Co., SC, suggest that William’s father was probably David Allen, a Revolutionary soldier. If the 1850 census entries for William A. Allen and Charles Allen were correct, David was likely living in Virginia between William A. Allen’s birth between 1768 and 1775 and Charles Allen’s birth about 1791. He then seems to have moved to Laurens County, South Carolina, prior to 1795.

Hence, this profile suggests that David Allen was born prior to 1755. He participated in some way in the American Revolution between 1776 and 1783 in support of the new United States. He likely was living in Virginia at that time, and he apparently lived there as late as 1791. Although this narrowed the field from an exhaustive search for the Allen surname itself to a more limited search for men named David Allen living in Virginia at this time who fit this demographic profile, without more precise information on David’s place of origin it was still necessary to examine Virginia records broadly for the period from 1776 to 1800 for the Allen surname. Hence, deed, will, tax, and county court order records for Virginia counties during this period were examined, as well as to surviving parish registers and revolutionary war rosters, service records, and pension applications.

No 1790 or 1800 census survived for Virginia. What does exist, however, are various guides produced by means of Virginia’s extensive personal property tax records. Virginia’s tax system at the time required that white males over age 16 pay a form of poll tax. The surviving lists for most counties are extensive, although they differ slightly in nature from year to year and sometimes from county to county. In some years and locations, all white males over age 16 were identified by name. In others, only the head of household was identified by name, while the total number of white males meeting the age requirement was listed by number. In the same year, one county might employ one approach, and a neighboring county employ another one. Still, these records, which begin in 1782, provide a valuable research tool not found in other states (

Weisiger 2020).

To compensate for the absence of a surviving statewide census in 1790 and 1800, researchers have utilized these tax lists to produce census substitutes. An early version of this was created by Augusta B. Fothergill in 1942 (

Fothergill 1940), and a still earlier version, derived from 1782 and 1785 tax lists, by the U.S. Bureau of Census in 1910 (

Bureau of Census 1910). More recently, Nettie Schreiner-Yantis and Florene Love used the 1787 lists to create a three-volume statewide index estimated to list 95% of white males aged 16 and above (

Schreiner-Yantis and Love 1987). In addition, Steve and Yvonne Binns have utilized digitized tax lists on their now defunct website

Binns Genealogy to create a substitute for the lost 1790 and 1800 Virginia census by indexing the nearest tax lists to those years (

Binns 2022).

Using these sources, approximately 12 men residing in Virginia between 1787 and 1800 named David Allen were identified. These included men living in Amelia, Fairfax, Goochland, Halifax, Hampshire, Henrico, Louisa, Nelson, Orange, Pittsylvania, Powhatan, and Shenandoah Counties. In addition, several of these men participated in the American Revolution from Virginia. This list included multiple men with the ranks of private as well as different men who served as corporal, ensign, second lieutenant, lieutenant. In addition, at least one man named David Allen seems to have served in a local militia unit.

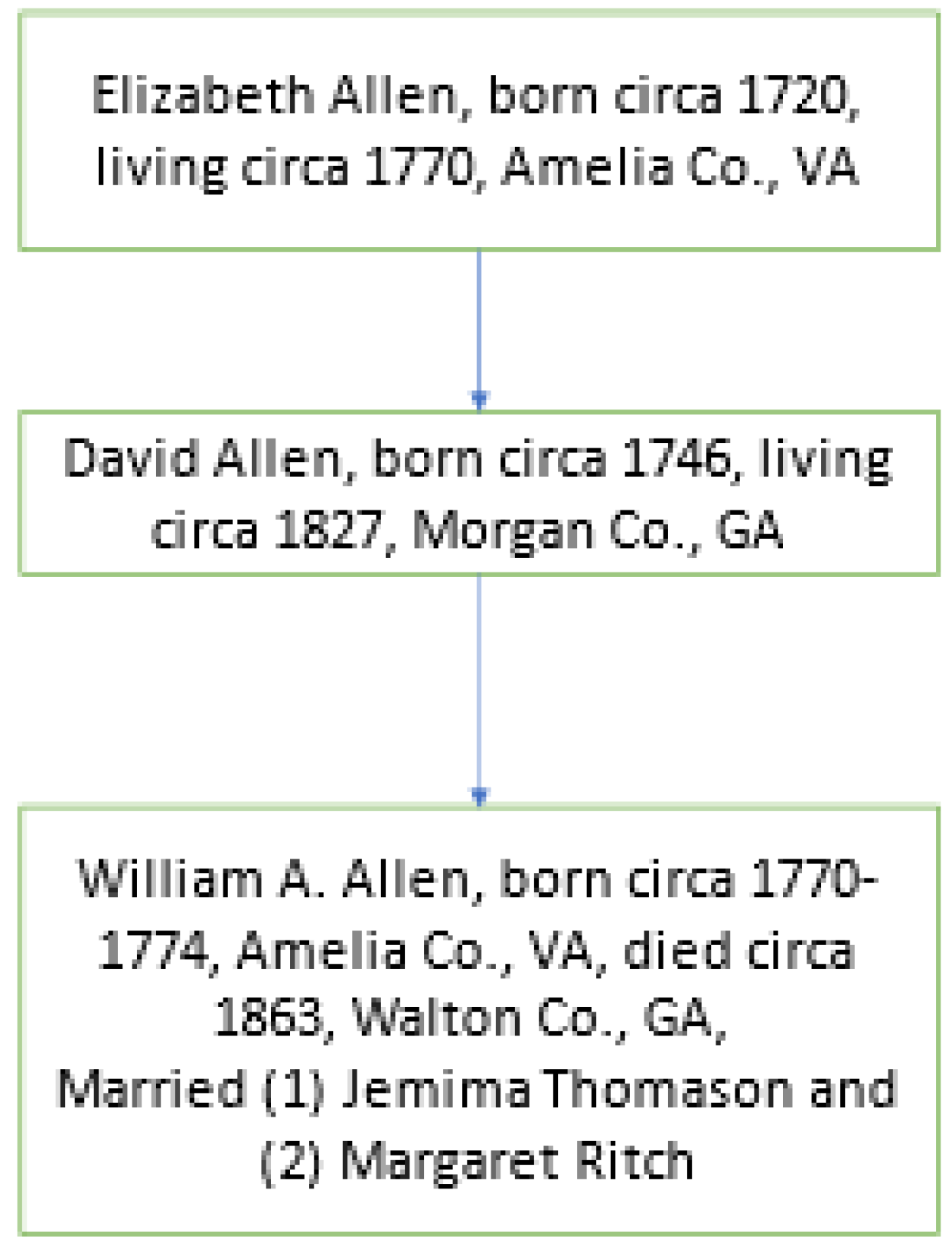

Chronological studies were developed for each of these men with the result that all of them could be eliminated based on the assembled profile but one. Several men named David Allen left the state and went places other than South Carolina and Georgia. Several others remained in Virginia and died there, leaving a clear trail through the post-Revolutionary years and into the 19th century. Of the 12 men studied, then, only one emerged that fit the known profile, which was David Allen of Amelia County, Virginia.

This David Allen first appeared on the 1762 Amelia Co., VA, tithables list, when he was taxed in the household of his mother Elizabeth Allen (

Amelia 1762). The tithable system antedated the personal property taxation system but was based on similar principles of taxation (

Library of Virginia 2021). Tithable age in Virginia was 16, which means that this David was born in or before 1746. His mother Elizabeth Allen first appeared in Amelia County in 1759, when she purchased 100 acres on the Great Bent Creek from Hector Truly and William Foster (

Truly and Foster 1759). The land joined James Hurt and Isaac Tinsley, and Elizabeth and her family seem to have had a close association with Isaac and Margaret Rucker Tinsley, who had recently moved to Amelia from Orange County, Virginia. The 1762 tithables list placed them in Thomas Tabb’s District of Raleigh Parish in the area between Flat Creek and the Appomattox River (

Amelia 1762). This was northwestern Amelia County, near the boundary with Cumberland County and, after its formation in 1777, Powhatan County. David Allen also appeared with his mother in 1763 and 1764, when a second son, Samuel Allen, appeared for the first time (

Amelia 1763,

1764). If Samuel had just reached 16 years of age, then this suggests that he was born between 1746 and 1748—although it is possible that he was older. David appeared in the same district in 1765, still in his mother’s household, and in 1767, when he appeared as an independent householder for the first time. Men usually were listed independently after reaching age 21, which supports the idea that David was born about 1746 (

Amelia 1765,

1767).

This David Allen is likely the David Allen shown with military service in the vicinity of Amelia Courthouse in 1781, and he appeared on Amelia County Personal Property tax lists for 1782 and 1784 (

Amelia 1782,

1783,

1784;

Fowler 1832). He may have been the David Allen who appeared in neighboring Cumberland and Powhatan Counties throughout the 1780s, but he was back in Amelia County by 1790. David was taxed in Amelia County from 1790 to 1798 (

Amelia 1790,

1791 1792,

1793,

1794,

1795,

1796,

1797,

1798). He appeared several times in Amelia County records during these years but vanished after 1798, although his brother Samuel remained in the area until he died in 1817.

The 1790 Amelia Co., VA, Personal Property tax list showed both head of household and, in a separate column, the names of all white males of taxable age. David Allen was shown as head of household, but his household included two white males of tithable age:

“David Allin, Wm. Allin”. This was the first and only time that William Allen appeared by name in David’s household, although David Allen paid tax for two tithables until 1792 (

Amelia 1790,

1791,

1792). Lists from 1793 to 1798 show him taxed with only one white tithable, indicating that William Allen had left the household (

Amelia 1793,

1794,

1795,

1796,

1797,

1798). Since the 1790 tax list indicates that David Allen was the father of a son named William Allen who was born in or before 1774, it may be that when William disappeared from David’s household after 1793 he had left for South Carolina. If the date provided in his 1848 deposition is correct, he arrived in Laurens County in 1795 or 1796. David and his younger children might then have joined him in 1798 or 1799 in time to be enumerated in Laurens County in 1800.

Cumulatively, this evidence suggests that William A. Allen was born in Amelia Co., VA, between 1768 and 1774, that he was a son of David Allen, and that he was a grandson of Elizabeth Allen (See

Figure 9). A 1773–1774 birthdate would fit well with the 1790 tax list data as well as with the 1800 and 1820 census enumerations, although a birthdate nearer 1769 would fit with William’s 1848 deposition as well as with the 1830, 1840, and 1850 census enumerations. Given what seems to have been a tendency later in life to exaggerate his age, William likely was born at some point between 1769 and 1773. It would seem that he left Amelia County in the early 1790s and moved to Laurens County, South Carolina, where his father joined him a few years later. Given the migration routes at the time, he may well have had extended family who had already settled there. William and his father David settled in the same neighborhood in which the Thomason and Thompson families lived, and events would draw William into the orbit of both families.

Should one wish to trace William’s origins prior to the arrival of Elizabeth Allen in Amelia County, Virginia, about 1759, a more extended one-name study approach might be necessary in order to identify Allen families throughout the region to which Elizabeth’s unknown, presumably deceased husband may have belonged. In addition to this, modern Y-DNA analysis might be used profitably to help identify David Allen’s paternal ancestry, along with onomastics and network analysis. Some of this work has already been carried out by John Barrett Robb, whose “Allen DNA Patrilineage 2 Project” study has already documented early Chesapeake Allen families whose Y-DNA places them into the Allen “Patrilineage 2” group that originated in Hanover and New Kent Counties and spread throughout Southside Virginia. This earlier research lies outside the scope of this paper, however, which focuses only on identifying William A. Allen of Walton Co., GA, and his immediate background (

Robb 2022).

In summary, the one-name study approach provided a means of tracing David Allen and family prior to their arrival in South Carolina. Virginia records were broadly examined between 1776 and 1800 to identify adult men named David Allen who might fit the demographic profile for the man who later lived in Laurens Co., SC, and Morgan Co., GA. Studying wills, deeds, court orders, parish registers, revolutionary war records, and indexed tax documents from the period between 1782 and 1800 in place of the now missing 1790 and 1800 Virginia census revealed approximately 12 adult men named David Allen living in Virginia during this period, several of whom were also Revolutionary soldiers. Examining each man in turn narrowed the field to a single individual who fit the correct demographic profile, David Allen of Amelia County. This man was born in or before 1746, participated in the American Revolution, and remained in Amelia County until 1798. Moreover, Amelia County tax records indicate that this David Allen had a son William Allen who was born between 1769 and 1774. This fits with all the known evidence concerning William A. Allen and his putative father David Allen garnered through the chronological study, family reconstitution, and community study methods. Thus, a viable solution to the problem of William A. Allen’s origins and background seems to have been reached.