Female Connectors in Social Networks: Catharine Minnich (Died 1843, Pennsylvania)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

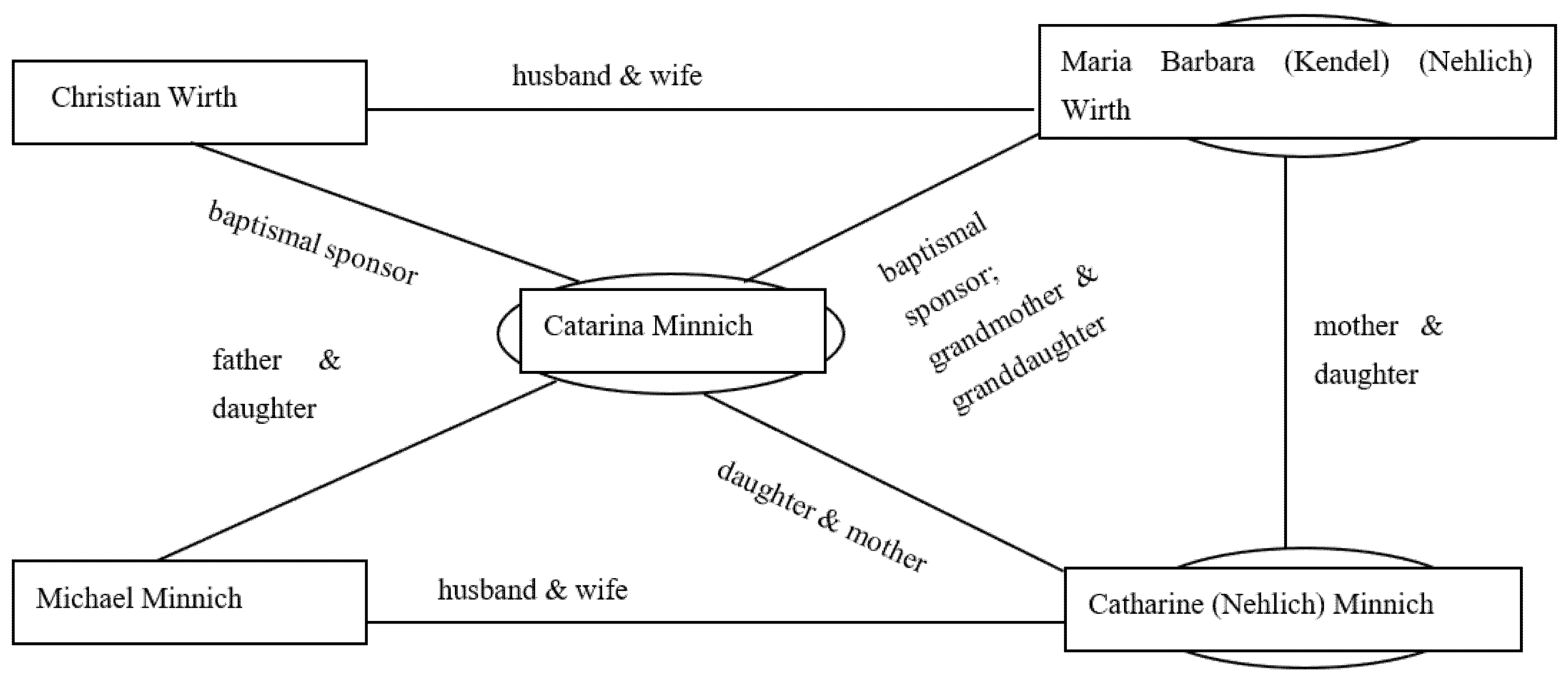

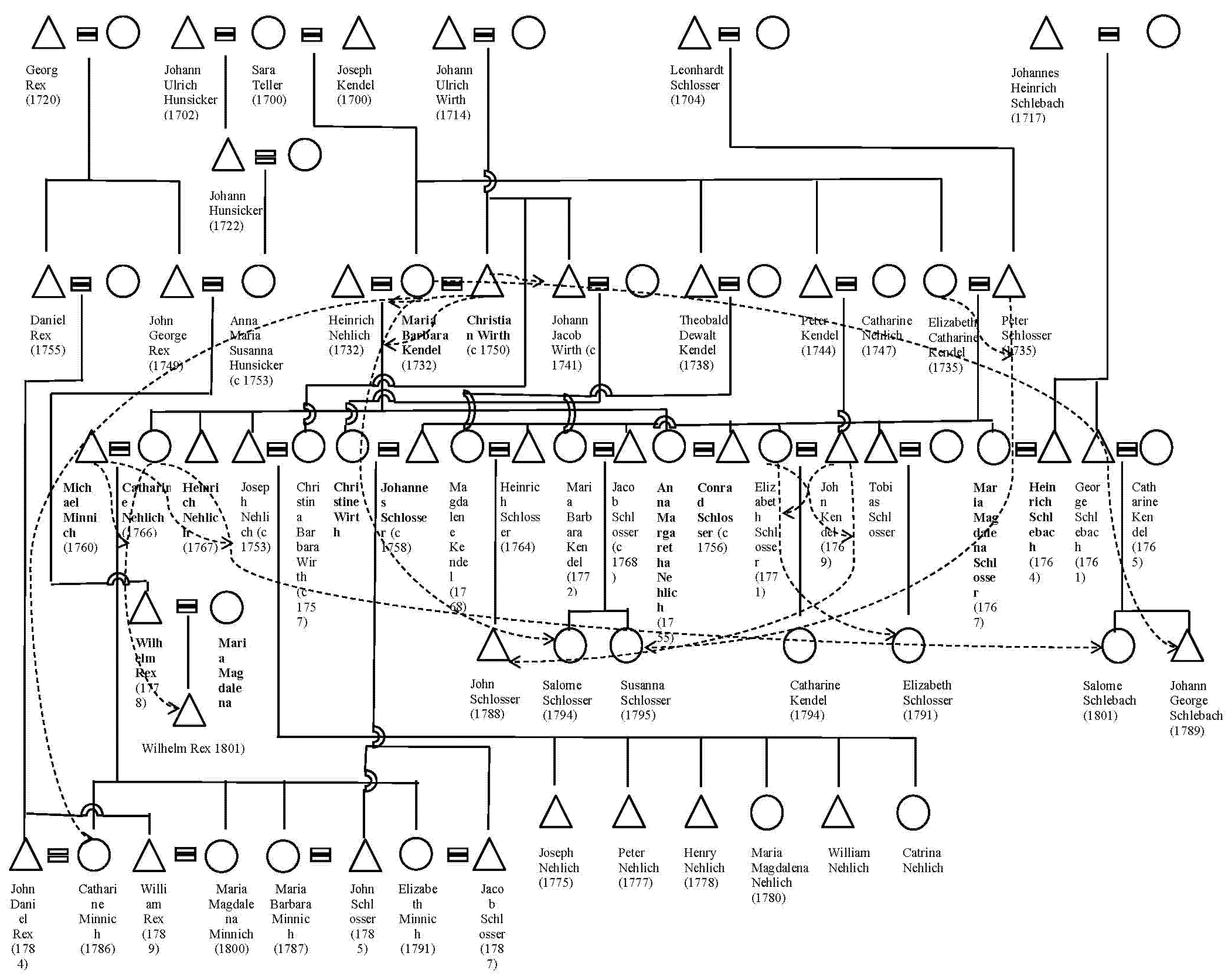

2. Theory and Methodological Practice

2.1. Networks, Female Connectors, and 18th-Century German Kinship

2.2. Networks

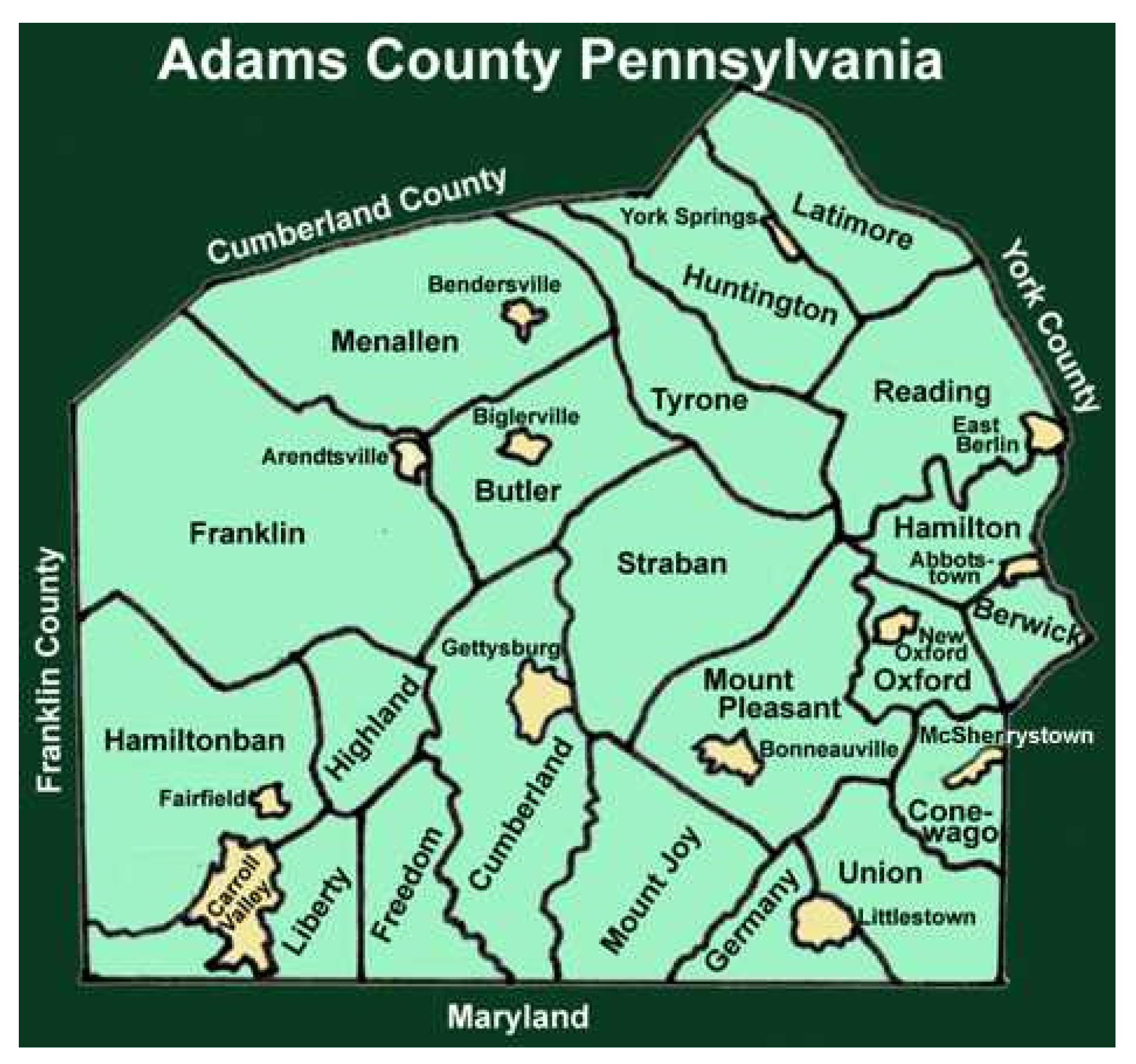

3. Case Study: Catharine Minnich (Died 1843) of Adams County, Pennsylvania

3.1. Introductory Remarks

3.2. Early-Marriage Social Interactions

3.3. Northampton County: Initial Research

3.4. Sponsors

3.5. Marriages

3.6. Revisiting the Initial Network

3.7. Network Reconstruction Observations

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Antonucci, Toni C. 2001. Social Relations: An Examination of Social Networks, Social Support and Sense of Control. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, 5th ed. Edited by James E. Birren and K. Warner Schaie. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Appeal Tyrone. 1784. Appeal Warrant for Supplies, Michl Minich. 1784. Tyrone Township, York County, Pennsylvania. Family History Library (FHL), Salt Lake City, UT. Microfilm #22,243.

- Bamford, Sandra, and James Leach. 2009. Introduction: Pedigrees of Knowledge: Anthropology and the Genealogical Model. In Kinship and Beyond: The Genealogical Model Reconsidered. Edited by Sandra Bamford and James Leach. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Battersby, Christine. 1998. The Phenomenal Woman: Feminist Metaphysics and the Patterns of Identity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bender. 1786–1860. Allgemeines Tauf Brodogolum in dem Stadt Pensilvania in der Graffschaft Yorck in dem Taunschip Menellen. Lancaster: Evangelical and Reformed Historical Society.

- Blumer, Rev. Abraham. 1773–1787. Records: Marriages and Burials, Allentown, Pennsylvania. FHL Microfilm #1,305,842, item 5.

- Butler, Judith. 2007. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge. First published 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten, Janet. 2001. Introduction: Cultures of Relatedness. In Cultues of Relatednewss: New Approaches to the Study of Kinship. Edited by Janet Carsten. Cambidge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cavarero, Adriana. 1995. Spite of Plato: A Feminist Rewriting of Ancient Philosophy. Translated by Serena Anderlini-D’Onofrio, and Áine O’Healy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cavarero, Adriana. 2014. A Child Has Been Born unto Us. Translated by Silvia Guslandi and Cosette Bruhns. Philosophia 4: 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chodorow, Nancy. 1978. The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Karen S. 1982. Network Structures from an Exchange Perspective. In Social Structure and Network Analysis. Edited by Peter V. Marsden and Nan Lin. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cornett, Judy M. 1997. Hoodwink’d by Custom: The Exclusion of Woman from Juries in Eighteenth-Century English Law and Literature. William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice 4: 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cott, Nancy F. 1997. The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman’s Sphere” in New England, 1780–835, 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Beauvoir, Simone. 1949. The Second Sex. Translated by Constance Borde, and Sheila Malovany-Chavallier. Reprinted 2011. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- De Nooy, Wouter, Andrej Mrvar, and Vladimir Batagelj. 2005. Exploratory Social Network Analysis with Pajek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Debray, Régis. 2000. Transmitting Culture. Translated by Eric Rauth. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diedendorf. 1698–1794. Baptisms, Marriages, Deaths. FHL Microfilm #742,362, items 1–3.

- Durkheim, Émile. 1965. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by Joseph Ward Swain. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Estate File Henry Neile. 1774. Estate file #613. Northampton County Archives, Forks Township, Easton, Pennsylvania.

- Estate File Joseph Kennel. 1767. Estate file #447. Northampton County Archives, Forks Township, Easton, Pennsylvania.

- Farber, Bernard. 1981. Conceptions of Kinship. New York: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Feeley-Harnik, Gillian. 2001. The Ethnography of Creation: Lewis Henry Morgan and the American Beaver. In Relative Values: Reconfiguring Kinship Studies. Edited by Sarah Franklin and Susan McKinnon. Durham: Duke University Presss, pp. 54–84. [Google Scholar]

- FindAGrave. 2021. Available online: www.findagrave.com (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Fortes, Meyer. 1969. Introduction. In The Developmental Cycle in Domestic Groups. Edited by Jack Goody. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, George M. 1969. Godparents and Social Networks in Tzintzuntzan. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 25: 261–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1982. The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. In Social Structure and Network Analysis. Edited by Peter V. Marsden and Nan Lin. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, pp. 105–30. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, Lisa. 2006. The Gift of the Other: Levinas and the Politics of Reproduction. Albany: Stater University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzi-Heeb, Sandro. 2009. Kinship, Ritual Kinship and Political Milieus in an Alpine Valley in 19th Century. History of the Family 14: 107–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. 1986. The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helmreich, Stefan. 2001. Kinship in Hypertext: Transubstantiating Fatherhood and Information Flow in Artificial Life. In Relative Values: Reconfiguring Kinship Studies. Edited by Sarah Franklin and Susan McKinnon. Durham: Duke University Presss, pp. 116–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hinke, William J. 1765–1841. Records of Schlosser’s or Union Reformed Church, Unionville, North Whitehall Township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania. FHL Microfilm #20,352, item 2.

- Hollenbach, Raymond E. 1740–1978. Lutheran Church Record Book. In Heidelberg Church, Heidelberg Township, Lehigh County, PA: A History and the Church Records, 1740–1978. Available online: https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/records/item/62081-redirection (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Kadushin, Charles. 2012. Understanding Social Networks: Theories, Concepts, and Findings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Anne-Marie. 2011. Kinship, Afffinity and Connectedness: Exploring the Role of Genealogy in Personal Lives. Sociology 45: 379–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, Connie. 1994. Proving a Maternal Line: The Case of Francis B. Whitney. National Genealogical Society Quarterly 82: 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti, Donna L., and Benjamin Chabot-Hanowell. 2011. The Foundation of Kinship: Households. Human Nature 22: 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lévy-Bruhl, Lucien. 1985. How Natives Think. Translated by Lilian A. Clare. Princeton: Princeton University Press. First published 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Litchman, William M. 2007. Using Cluster Methodology to Backtrack an Ancestor: The Case of John Bradbery. National Genealogical Society Quarterly 95: 103–16. [Google Scholar]

- Long, John H. 1996. Atlas of Historical County Boundaries: Pennsylvania. New York: Simon and Schuster Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Mazey, Mary Ellen, and David R. Lee. 1983. Her Space, Her Place: A Geography of Women. Washington: Association of American Geographers. [Google Scholar]

- Medick, Hans, and David Warren Sabean, eds. 1984. Interest and Emotion: Essays on the Study of Family and Kinship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Elizabeth Shown. 2012a. QuickSheet: The Historical Biographer’s Guide to Cluster Research (The FAN Principle). Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Elizabeth Shown. 2012b. QuickSheet: The Historical Biographer’s Guide to Individual Problem Analysis. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Elizabeth Shown. 2012c. QuickLesson 11: Identity Problems & the FAN Principle. Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage. Available online: evidenceexplained.com/content/quickleson-11-identity-problems-fanprinciple (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Mitterauer, Michael. 1995. Peasant and Non-Peasant Family Forms in Relation to the Physical Environment and the Local Economy. In The European Peasant Family and Society: Historical Studies. Edited by Richard L. Rudolph. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 26–48. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Lewis Henry. 1997. Systems of Consanguinty and Affinity of the Human Family. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. First published 1870. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, Catherine. 2004. Genetic Kinship. Cultural Studies 18: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelich, Joseph. 1792. Administration Account. In Joseph Nehlich, 1786, Tyrone Township Estate File. York County Archives, York, Pennsylvania.

- Neely/Nehlich, Joseph. 1786. Will. York County, Pennsylvania Wills G: 93–94. FHL Microfilm #22,132, image 460.

- Neile, Henry. 1773–1774. [written in 1773, proved in 1774]. Will. Northampton County, Pennsylvania Wills I: 131–33. FHL Microfilm #5,554,758, images 86–87.

- Newman, Mark, Albert-László Barabási, and Duncan J. Watts, eds. 2006. The Structure and Dynamics of Networks. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nutini, Hugo G., and Betty Bell. 1980. Ritual Kinship: The Structure and Historical Development of the Compadrazgo System in Rural Tlaxcala. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Parish Register of Benders Church. n.d. Adams County Church Records of the 18th Century. Westminster: Family Line Publications.

- Quataert, Jean. 1986. A Preliminary Investigation into the Issue of Gender Work Roles. In German Women in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries: A Social and Literary History. Edited by Ruth-Ellen B. Joeres and Mary Jo Maynes. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rebel, Hermann. 1983. Peasant Classes: The Bureaucratization of Property and Family Relations under Early Habsburg Absolutism 1511–636. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, William Halse Rivers. 1900. A Genealogical Method of Collecting Social and Vital Statistics. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 30: 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robisheaux, Thomas. 1989. Rural Society and the Search for Order in Early Modern Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, Richard L. 1995. Major Issues in the Study of the European Peasant Family, Economy, and Society. In The European Peasant Family and Society: Historical Studies. Edited by Richard L. Rudolph. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 6–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rytina, Steve. 1982. Structural Constraints on Intergroup Contact: Size, Proportion, and Intermarriage. In Social Structure and Network Analysis. Edited by Peter V. Marsden and Nan Lin. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sabean, David Warren. 1998. Kinship in Neckarhausen, 1700–870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlins, Marshall. 2013. What Kinship Is—And Is Not. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, Marylynn. 1986. Women and the Law of Property in Early America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, David S. 1980. American Kinship: A Cultural Account, 2nd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, Rev. Daniel. n.d. Personal Register of the Rev. Daniel Schumacher. In Pennsylvania and New Jersey, U.S. Church and Town Records, 1669–2013 Collection. Translated by Frederick S. Weiser. Available online: www.ancestry.com (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Scott, John. 1988. Trend Report: Social Network Analysis. Sociology 22: 109–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, Georg. 1950. The Sociology of Georg Simmel. Translated by Kurt H. Wolff. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Amy M. 2008. Family Webs: The Impact of Women’s Genealogy Research in Family Communications. Ph.D. dissertation, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Linda. 2010. Kinship and Gender: An Introduction, 4th ed. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strathern, Marilyn. 1988. The Gender of the Gift: Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strathern, Marilyn. 2018. Opening up Relations. In A World of Many Worlds. Edited by Marisol de la Cadena and Mario Blaser. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Strathern, Marilyn. 2020. Relations: An Anthropological Account. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tax Menallen. 1786. Tax Assessment List. Micheal Menoch. 1786. Menallen Township, York County, Pennsylvania. FHL Microfilm # 1,449,184.

- Tax Tyrone. 1783. Tax List. Joseph Neely. 1783. Tyrone Township, York County, Pennsylvania. FHL Microfilm #22,243.

- Tax Tyrone. 1785. Tax Assessment List. Michael Minigh. 1785. Tyrone Township, York County, Pennsylvania. FHL Microfilm #22,236.

- Theibault, John C. 1995. German Villages in Crisis: Rural Life in Hesse-Kassel and the Thirty Years’ War, 1580–720. Boston: Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 2015. The Relative Native: Essays on Indigenous Conceptual Worlds. Chicago: Hau Books. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick S. Weiser, trans. 1791–1874. Baptismal Records of the Upper Bermudian “Ground Oak” Church, Huntington Township, Adams County, Pennsylvania 1791–1874. p. 4. Available online: https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/records/item/115463-baptismal-records-of-the-upper-bermudian-ground-oak-church-huntingdon-township-adams-county-pennsylvania-1791-1874?offset=1 (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Wellman, Barry. 1982. Studying Personal Communities. In Social Structure and Network Analysis. Edited by Peter V. Marsden and Nan Lin. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, Barry. 1988. Structural Analysis: From Method and Metaphor to Theory and Substance. In Social Structures: A Network Approach. Edited by Barry Wellman and Stephen D. Berkowitz. Greenwich: JAI Press, pp. 19–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, Barry, Peter J. Carrington, and Alan Hall. 1988. Networks as Personal Communities. In Social Structures: A Network Approach. Edited by Barry Wellman and Stephen D. Berkowitz. Greenwich: JAI Press, pp. 130–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner-Hanks. 2013. Early Modern Europe 1450–789, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, Christian. 1784. Petition. Northampton County, Pennsylvania Orphans’ Court Records E: 43. FHL Microfilm #946,985.

| Children | Birth Date | Sponsors |

|---|---|---|

| Catarina | 3 July 1786 | Christian and Maria Barbara Wert |

| Maria Barbara | 19 October 1787 | Peter and Catarina Spengler |

| Michael | 22 August 1789 | Unknown |

| Elisabeth | 5 November 1791 | Heinrich Nehlich and wife |

| George | 22 July 1793 | Unknown |

| Rebecca | 1 October 1795 | Conrad and Anna Margaretha Schlosser |

| Michael | 27 November 1797 | John and Catharine Panter |

| Maria Magdalena | 29 November 1800 | William and Maria Magdalena Rex |

| Daniel | 28 February 1803 | George and Hanna Herzel |

| Johannes | 30 November 1805 | Johannes and Christine Schlosser |

| Henry | 3 May 1808 | Henrich and Molly Schlebach |

| Children | Birth Year | Parents |

|---|---|---|

| Catarina | 1787 | Peter and Catarina Spengeler |

| Saara | 1798 | John and Susanna Klein |

| Wilhelm | 1801 | Wilhelm and Maria Magdalena Rex |

| Salome | 1801 | George and Katharina Schlebach |

| Michael | 1806 | John and Elisabeth Klark |

| Elisabeth | 1806 | Johannes and Christina Schlebach |

| Role | Person |

|---|---|

| Executor | Christian Wirt |

| Guardian for son Joseph | Christian Wirt |

| Guardian for son Peter | Michael Minnich |

| Witness to will | Michael Minnich |

| Guardian for son William | William Miehl |

| Guardian for daughter Catrina | -ikles Dedrick Jr |

| Guardian for daughter Mary | Casper Snar |

| Guardian for son Henry | George Miehl |

| Witness to will | George Miehl |

| Pre-deceased wife | Christina Barbara |

| Witness to will | Thomas McCashlen |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hatton, S.B. Female Connectors in Social Networks: Catharine Minnich (Died 1843, Pennsylvania). Genealogy 2021, 5, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040104

Hatton SB. Female Connectors in Social Networks: Catharine Minnich (Died 1843, Pennsylvania). Genealogy. 2021; 5(4):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040104

Chicago/Turabian StyleHatton, Stephen B. 2021. "Female Connectors in Social Networks: Catharine Minnich (Died 1843, Pennsylvania)" Genealogy 5, no. 4: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040104

APA StyleHatton, S. B. (2021). Female Connectors in Social Networks: Catharine Minnich (Died 1843, Pennsylvania). Genealogy, 5(4), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040104