King Béla III of the Árpád Dynasty and Byzantium—Genealogical Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

- (a)

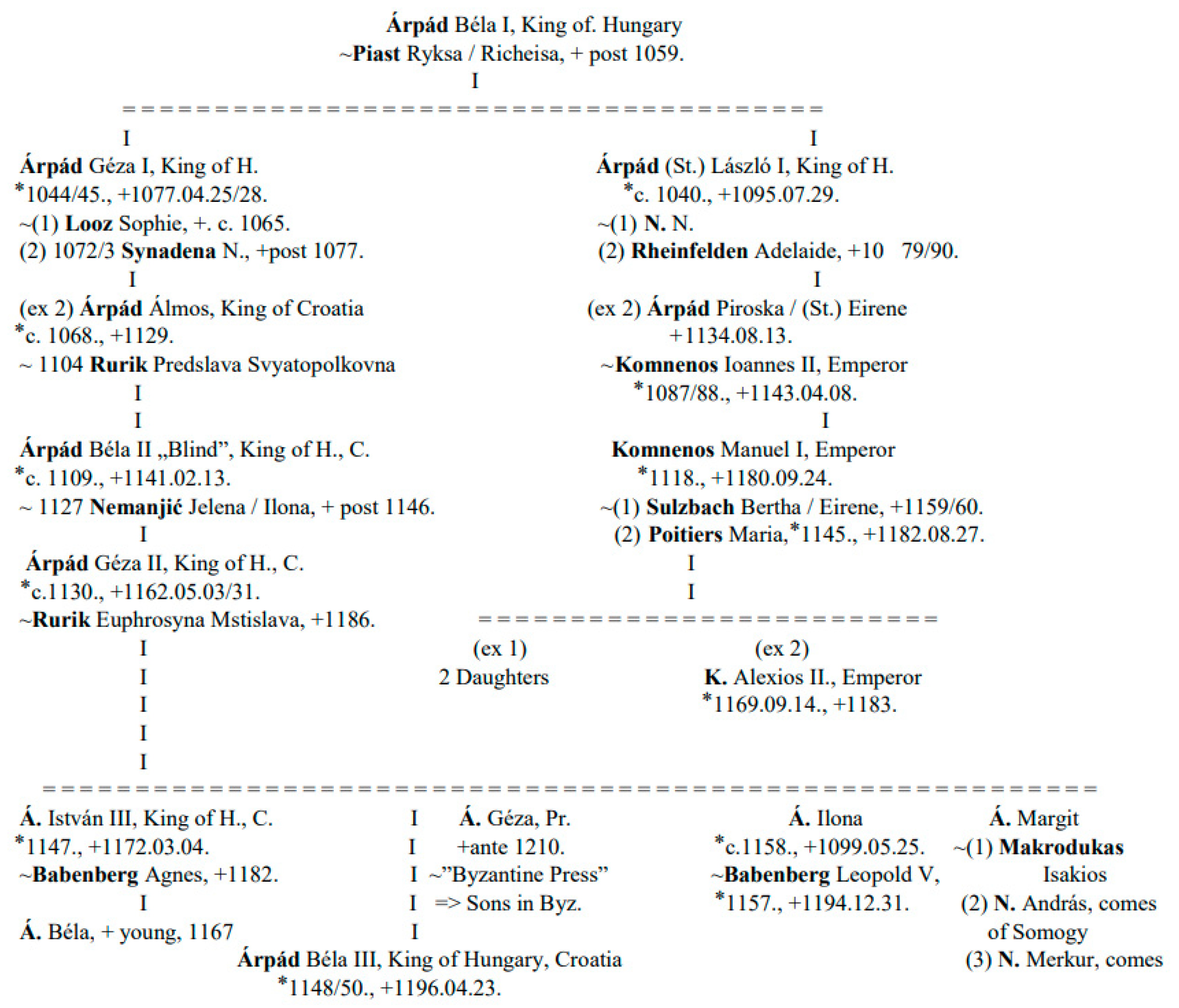

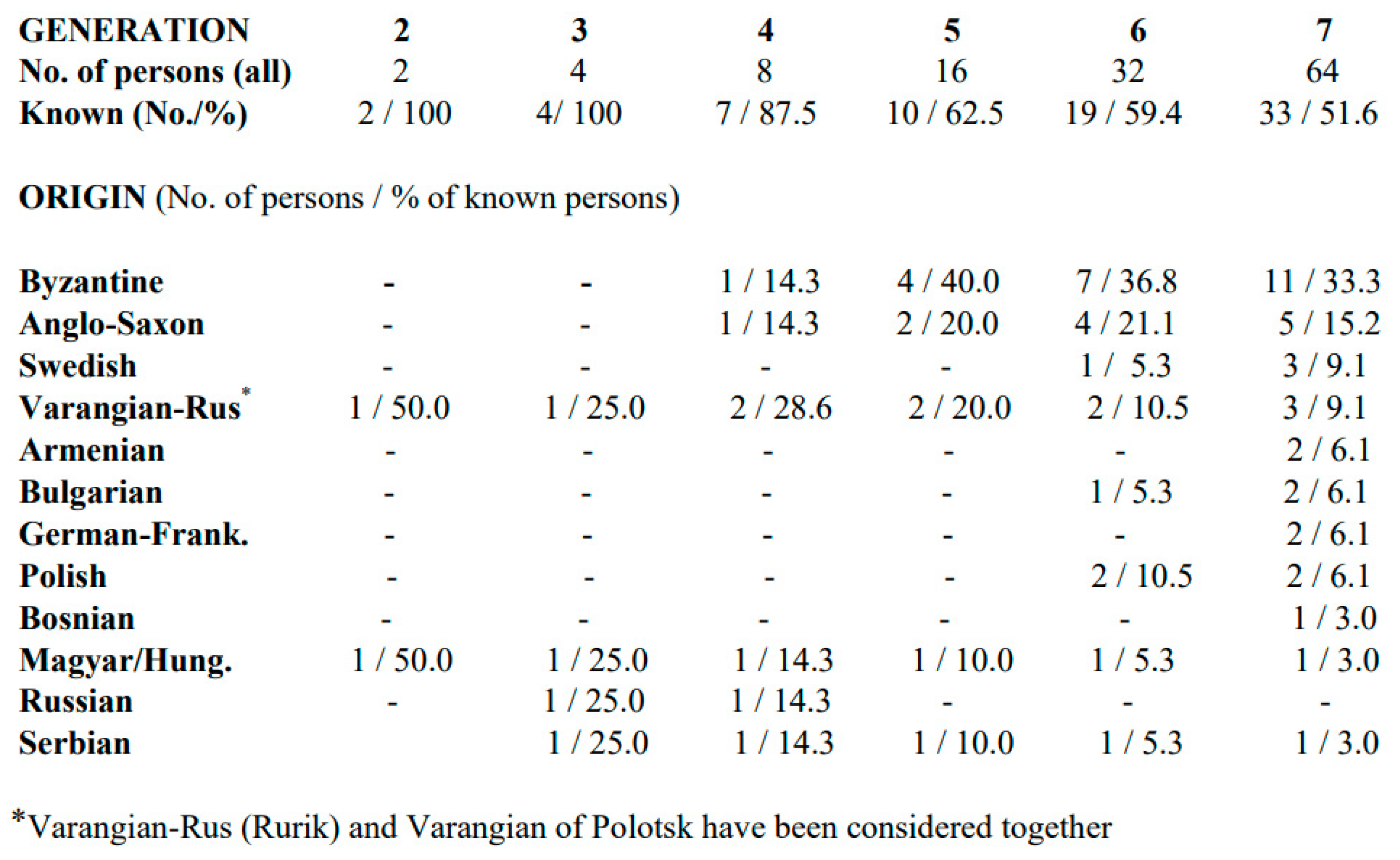

- Árpád Béla III, the son of Árpád Géza II (ES.II.T.154), a Magyar/Hungarian father and a Rurik-Kiev mother (Euphrosyna Mstislava, ES.II.T.135). At this level, he can be regarded as being apparently a 50—50% descendant of Hungarian and Rurik/Viking (Varangian-Rus) (Franklin and Shephard 1996; Raffensperger and Ingham 2007; Magocsi 2010; Häkkinen 2012; Volkov and Seslavin 2019) parents.

- (b)

- The situation becomes more complicated in the 5th generation. Here, from the 16 possible great-great grandfathers and -mothers, 10 (62.50%) are known. From the 10 known progenitors we found the highest number, 4 (40.00%), to be of Byzantine progenitors, together with 2 (20.00%) from the Rurik (Varangian-Rus) family, and an additional 2 (20.00%) from Anglo-Saxon families, as well as 1—1 (10.00% each) of Hungarian and Serbian origins.

- (c)

- At the 7th generation, from the possible 64 progenitors, 33 (51.57%) are known. From these 33 persons, the predominant majority (11/33.33%) were Byzantine, followed by 5 (15.15%) Anglo-Saxon, 3—3 (9.09% each) Varangian-Rus and Swedish, 2—2—2—2 (6.06% each) Armenian, Bulgarian, German-Frankish, and Polish, as well as by 1—1 (3.03% each) Bosnian and Serbian ancestors, together with the representative of the Hungarian paternal line: 1 (3.03%).

- (α)

- Moving further back in time, the “original” Asiatic lineages (Nagy et al. 2021) brought by the paternal forefathers, together with those of the Hungarian conquerors, becomes more “diluted” by the politically induced inter-dynastic marriages (obviously: in genealogical tables of ascendence, as Table A1, this effect is observed going “back” in time). Very recently, in the archaeogenetic DNA study of samples obtained from the bones of Árpád (Saint) László I (ES.II.T.154, Kristóf et al. 2017; Varga et al. 2022), the brother of the great-great grandfather of Béla III and, thus, who appears five generations earlier in the family tree of the Árpáds (ES.II.T.153/155, Glatz 2006; Zsoldos 2022; see also Chart A1), the typical “Árpád” (Asiatic) elements in the DNA (Olasz et al. 2019; Nagy et al. 2021) of King (Saint) László I were found to be more concentrated (Varga et al. 2022) than those in the samples obtained from the bones of King Béla III.

- (β)

- The most characteristic example of the influence of the trans-continental inter-dynastic marriages appeared as the relatively high proportion of (well-documented, e.g., Sisam 1953; Bassett 1989; Yorke 1995; Baxter 2007) five Anglo-Saxon progenitors (15.15% from the known persons). Interestingly, this is not a unique example of such “long-distance” marriages between the Árpáds and the Anglo-Saxon Wessex-England dynasty (Cornides 1778; Malcolmes 1937; Fest [1940] 2020; Pályi 2022).

- (γ)

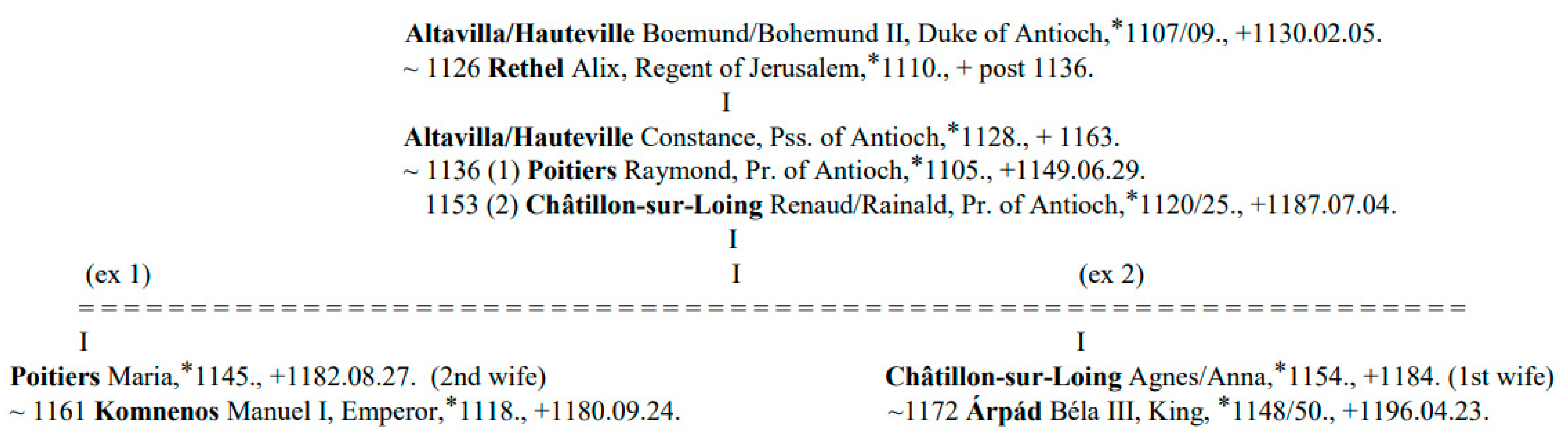

- Perhaps the most interesting result of the present study is that the Byzantine progenitors were represented already in the 5th generation by a high percentage (40.00% of the 11 known persons), which also remained high in the 7th generation: 33.33% of the known persons (33), but still 17.19% of all possible (64) ancestors. This situation can perhaps be experimentally demonstrated if a characteristic “Byzantine” DNA fragment could be identified (this option, however, still needs much work: e.g., Ottoni et al. 2011; Yardumian and Schurr 2011). On the other hand, the multi-sided Byzantine kinship of Prince Béla could have been known to Emperor Manuel I and his advisers, when he/they reached the very unusual decision to, as, heir of the imperial throne, invite a member of a foreign dynasty, even if this family was closely related to the ruling Emperor.

3. Data Acquisition

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 Árpád Béla III, King of Hungary and Croatia, * (1148/50), +1196.04.23, 1163–69: Heir to the Emperor of Byzantium, 1172: King. ES.II.T.154. |

| 2 Árpád Géza II, King of Hungary and Croatia, * (1130), +1182.05.03. 3 Rurik-Kiev Euphrosina Mstislava, +1186. ES.II.T.135. |

| 4 Árpád Béla II, “the Blind”, King of Hungary and Croatia, * (1109), +1141.02.13. 5 1127.04.29. (Nemanjić) Jelena/Ilona, +after 1146. ES.III/1.T.181. 1,2 6 Rurik-Kiev Mstislav II Vladimirovich, Grand Prince of Kiev, * 1076, +1132.04.15. 7 Saviditsova/Zavidich N. (Lyubava?) Dmitrieva, + after 1168, ES.II.T.135. 3 |

| 8 Árpád Álmos, Hungarian Prince, King of Croatia, * (1068), +1129. 9 Rurik-Kiev Predeslava Svyatopolkovna, ES.II.T.130. 10 (Nemanjić) Uros I, Duke of Serbia (Hung, later Byzantine vasall), * (1080.), +after 1130. 11 Diogenissa Anna 4 12 Rurik-Kiev (Saint) Vladimir Vsevolodovich Monomaches, Grand Prince of Kiev, * 1053, +1125.05.19. 13 (1) Wessex-England Gythe ES.II.T.78. 14 Savidich/Zavidich Dimitrij, nobelman of Novgorod, +1167. 15 N. N. |

| 16 Árpád Géza I /Magnus, * King of Hungary, 1044/45, +1077.04.25. 17 1065/73 (2) Synadena N. 1074: Queen, 1080: goes back to Byzantinum (according to ES.II.T.154.), * 1058.05.12, +1082.12.20. 5,6,7 18 Rurik-Kiev Svyatopolk II Michail Iziaslavich, Grand Prince of Kiev, * 1050.11.08, +1113.04.16. 19 (1) N. N. (concubine) 20 (Nemanjić) N. (Marko?) 21 N. N. 22 Diogenes Konstantinos, + (battle) 1074. 23 Komnene Theodora (sister of Emperor Komnenos Alexios I), ES.II.T.174. 24 Rurik-Kiev Vsevolod Yaroslavich, Grand Prince of Kiev, +1093.04.13. 25 Monomaches Maria, +1067. 8,9 26 Wessex-England Harold, King of England, * (1020), +(battle) 1066.10.14. 27 Mercia Ealgydth/Edith, +1066.10.14, ES.II.T.78. 10 28 …… 31 N. N. |

| 32 Árpád Béla I, King of Hungary, +1063.12 … 33 Piast Ryksa/Richeisa, * (1018.), +after 1059. ES.II.T.120. 34 Synadenos Theodoulos, Byzantine military officer, * ca. 1020, +1050. 2 35 (2) Botaneiataina/Botaneiatissa N. (Sister of Emperor Botaneiates Nikephoros III, 1002–1081, Emp.: 1078.01.07–1081.04.01) 11,12 36 Rurik-Kiev Izaislav I Yaroslavich, Grand Prince of Kiev, +(battle) 1078.10.03. 37 Piast Gertruda, +1108.01.04, ES.II.T.120. 38 N. N. 39 N. N. 40 (Nemanjić) N. (Petrislav?, assumed: son of Liubomir, Grand Župan and Bosnia N.) 41 …… 43 N. N. 44 Diogenes Romanos IV, Byzantine Emperor, * c. 1030, +(blinded) 1072.08.04. 13, Emp.: 1068–1071. 45 (1) Cometopuli N (Anna?). (daughter of C. Alusian from Bulgaria) 46 Komnenos Ioannes, patrikios, kuroplates, +1067.07.12. 47 1042 Charon-Dalassene Anna, Regent of the Byzantine Empire, * c.1025,+(nun) 1100/1101. 48 Rurik-Kiev Yaroslav I Vladimirovich “the Wise”, Grand Prince of Kiev, * (978)/980, +1054.02.20. 49 Sweden Ingegerd/Anna, +1050.02.10. ES.II.T.114. 50 Monomachos Konstantinos IX, Byzantine Emperor, * 1000, +1055.01.11, Emp.: 1042.06.11–1055.01.11. 14,15 51 ante 1025. (1) Skeraina N. (Maria/Elena?), * 1001, +1033/45. 52 Wessex Godwin, Earl of Wessex, +1053.04.15. 16,17,18 53 Sparkalegg Gytha Torkelsdottir, ES.II.T.78. 19 54 Mercia Alfgar, Earl of Mercia and of East Anglia, + c. 1060. 55 Malet Aelfgifu (Sister of M. William, Lord of Eye) 56 …… 63 N. N. |

| 64 Árpád Vazul/Vászoly, Hungarian Prince, +(blinded) 1037. Spring, ES.II.T.153. 65 Cometopuli N. katun, ES.II.T.168. 20 66 Piast Mieszko I (II?) Lambert, King of Poland, * 990, +1034.05.10. 67 Ezzonen-Lothringen Richeza, +1063.03.22, ES.I/2.T.201. 68 Synadenos N. 69 N. N. 70 Botaneiates Nikephoros 71 Dukaina N. (Sister of Emperor Dukas Michael VII, +1090, daughter of Emperor D. Konstantinos X, +1067.05.22. and Makrembolitissa Eudokia) ES.II.T.178. 72 Rurik-Kiev Yaroslav I Vladimirovich “the Wise”, Grand Prince of Kiev, * (978)/980, +1054.02.20. 73 Sweden Ingegerd (Anna), +1050.02.10, ES.II.T.114. 74 Piast Mieszko I (II?) Lambert, King of Poland, * 990, +1034.05.10. 75 Ezzonen-Lothringen Richeza, +1063.03.22, ES.I/2.T.201. 76 …… 87 N. N. 88 Diogenes Konstantinos, general, +(suicide) 1032. 89 Argyra N. (Daughter of A. Basileos, who was brother of Emperor A. Romanos III, +1034.04.11.) 90 Cometopuli Alusian, patrikios, for a short time tsar of Bulgaria in 1041. 91 N. N. (Armenian nobelwoman from Kharsianon) 92 Komnenos Manuel Erotikos, 950/1020. 93 N. (Maria?), +ca. 1015. 94 Charon Alexios, prefect of Italy 95 Dalassena N. (Daughter of Dalassenos Adrianos, uncle of D. Theophylaktos, general, military governor of Antiochia) 96 Rurik-Kiev (Saint) Vladimir Svyatoslavich, Prince of Novgorod, Grand Prince of Kiev, +1015.07.15. 97 Polock Rongned, + (nun) 1002, ES.II.T.127. 98 Sweden Olaf III, “Olaf Skotkonug”, King of Sweden, +1022. 99 N. Estrid, Princess of the Obotrites, ES.II.T.114. 100 Monomachos Theodosios, Byzantine state official 101 N. N. (Perhaps of armenian origin) 102 Skleros Basileos, governor 103 Argyra Pulcherina (Sister of Emperor Argyros Romanos III) 21,22,23 104 (Uncertain) (Wessex) Wulfnot Cild, Thegan of Sussex, +ca. 1014. 105 N. N. 106 Sparklegg (Sparkling?) Thorgil 107 (partner?) Halland Sigrid 108 Mercia Leofric, Earl of Mercia, +1057.08.31./09.30. 109 N. Godiva/Godgyfu, Lady, +1066/86. 24 110 …… 127 N. N. |

| Notes to Table A1 Main references (abbreviated as ES, followed by Vol. No, then by Table No.): Schwennicke, Detlev (Hrsg.). 1984. Europäische Stammtafeln. Neue Folge. Bd. II. Bd. III/1. Marburg: J. A. Stargardt. Schwennicke, Detlev. 1998. Europäische Stammtafeln. Neue Folge. Bd. XVIII. Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann. Schwennicke, Detlev. 1999. Europäische Stammtafeln. Neue Folge. Bd. I/2. Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann. Additional references and notes: 1 The family name “Nemanjić” was taken from ES.II.T.154, while it is lacking in ES.III/1.T.181. 2 According to recent speculations, ascendence of Queen Jelena/Ilona still needs further research: Farkas, Csaba. 2016. A Basileus unokahúga. [Niece of the Basileus, in Hung,] Fons 23 (1): 87–118. 3 freepages.rootsweb.com/~dearbornboutwell/school-alumni/fam4725.html (accessed on 17 September 2022) 4 w.genealogy.euweb.cz/balkan/balkan4.html (Marek, Miroslav. 2018) (accessed on 17 September 2022) 5 geni.com/people/Szünadéné/6000000013005079391 (accessed on 17 September 2022) 6 Vajay, Szabolcs. 2006. I Géza király családja. (The family of King Géza I, in Hung). Turul 79: 32–39. 7 According to certain opinions the mother of Prince/King Álmos was the first wife of King Géza I: Sophie von Looz (+ 1065, ES.XVIII.T.56.), e.g., Makk, Ferenc. 1989. The Árpáds and the Comneni. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 125, but Table “The Árpád dynasty” of the same book indicates Syndane as the mother of Álmos. More recently: hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Szündané_magyar_királyné (Last modification: 28 September 2021, accessed on 17 September 2022) 8 http://ciliacorte.com (acessed on 17 September 2022) 9 Kazhdan, Alexander. 1991. Monomachos. In: The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantinum (Alexander Kazhdan, Ed.). Oxford (UK)—New York (NY, USA): Oxford University Press. p. 1398. 10 Baxter, Stephen. 2007. The Earls of Mercia. Lordship and power in late Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press. 11 Curta, Florin. 2006. Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press. p. 298. 12 de Medeiros Publio Dias, J. Vicente. 2019. Der Herrscher als Versager (Nikephoros III. Botaniates, 1078–1081, der konstruierte Versager). Mainz: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. 13 Stavrakakis, N. 2016. The penality of blinding of the Emperor Romanus IV Diogenes. Archives of Hellenic Medicine 33: 675–79. 14 Kazhdan, Alexander. 1988/1989. Rus’-Byzantine princely marriages in the eleventh and twelfth century. Harvard Ukrainian Studies 12/13: 414–29. 15 Kaldellis, Anthony. 2017. Streams of gold, rivers of blood. Rise and fall of Byzantinum, 955 AD to the First Crusade. Oxford (UK)—New York (NY, USA): Oxford University Press. 16 Walker, Ian W. 1997. Harold, the last Anglo-Saxon King. Stroud (UK): Alan Sutton. 17 Mason, Emma. 2004. The House of Godwine: The history of dynasty. London: Hambledon & London. 18 Rex, Peter. 2005. Harold II: The doomed Saxon King. Stroud (UK): Tempus. 19 https://g.co/kgs/Lx6ggP (accessed on 17 September 2022) 20 According to an other view, King Béla I’s mother could have been from the (Hungarian) Tátony family. w.genealogy.euweb.cz/arpad/arpad1.html (Marek, Miroslav. 2018.) (accesed on 17 September 2022) 21 Vannier, Jean-François. 1975. Families byzantines: les Argyroi (IX—XIIesiècle). Paris: Serie Byzantina Sorbonensia, 1. 22 Kazhdan, Alexander. 1991. Argyros. In: The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantinum. Oxford (UK)—New York (NY. USA): Oxford University Press. p. 165. 23 Cheynet, Jean-Claude and Jean-François Vannier. 2003. Les Argyroi. Zbornik Radova Vizantološkog Instituta 40: 57–90. 24 Reid Boyd, Elisabeth. 2015. Lady Godiva’s revealing return to popular culture. Midwest Popular Culture Association, MP CA/ACA, 2015), Conference, 15.10.2015. Proceedings. pp. 1–17. https://www.academia.edu/34152351/NAKED_Lady_Godivas_Revealing_Return_to_Popular_culture (accessed on 17 September 2022) |

References

Primary Source

Schwennicke, Detlev (Hrsg). 1984. Europäische Stammtafeln. Neue Folge. Bd. II, Bd.III/1. Marburg: J. A. Stargardt. (Indicated in the text as ES.II.T. or ES.III/1.T. plus the actual Table number). J. A. Stargard, Marburg.Schwennicke, Detlev. 1998. Europäische Stammtafeln. Neue Folge. Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann. (Indicated in the text as ES.I/1.T. plus the actual Table number). V. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main.Secondary Source

- Baják, László. 2015. A Magyar-bizánci kapcsolatokról és III. Béla királyi reprezentációjáról. [On the Hungarian-Byzantine relationships and on the regal representation of Béla III, in Hung]. Folia Historica 31: 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Baják, László. 2021. Magnus Bela Rex: III. “nagy” Béla király és Kora. [Magnus Bela Rex: King Béla III “the Great” and His Age, in Hung]. Budapest: Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum Esztergomi Vármúzeuma. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, Steven R., ed. 1989. The Origins of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Leicester: Leicester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, Stephen. 2007. The Earls of Mercia. Lordship and Power in the Late Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benda, Kálmán. 1983. Magyarország Történeti Kronológiája. A kezdetektől 1526-ig. [Historical Chronology of Hungary. From the Beginnings to 1526. in Hung]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Cornides, Daniel. 1778. Regnum Hungariae qui Seculo XI Regnavere Genealogiam Illustrat. Posonii et Cassoviae: Ioannis Michaelis Landerer. [Google Scholar]

- Dissing, Joergen, Jonas Binladen, Anders Hansen, Brigitte Sejrsen, Eske Willerslev, and Niels Lynnerup. 2007. The last Viking King: A royal maternity case solved by ancient DNA analysis. Forensic Sciences International 166: 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, Pál. 1987. Temetkezések a középkori székesfehérvári bazilikában. [Burials in the medieval Basilica of Székesfehérvár, in Hung]. Századok 121: 613–37. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, Pál. 2001. The Realm of St. Stephen. A History of Medieval Hungary. Edited by Andrew Ayton. Translated by Tamás Pálosfalvi. London and New York: I. B. Tauris Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Érdy, János. 1853. III. Béla király és nejének Székes-Fehérvárott talált síremlékei. [The tombs of King Béla III and his spouse found in Székes-Fehérvár, in Hung.]. Pest: Emmich Gusztáv. [Google Scholar]

- Éry, Kinga, ed. 2008. A Székesfehérvári Királyi Bazilika Embertani Leletei. [Anthropological Finds of the Royal Basilica of Székesfehérvár, in Hung]. Budapest: Balassi Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Fest, Sándor. 2020. The Hungarian Origin of St. Margaret of Scotland. Berkeley: University of California. First published 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, Gyula. 1900. III. Béla Magyar Király Emlékezete. [Memory of Hungarian King Béla III, in. Hung]. Budapest: Hornyánszky V. Könyvnyomdája. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Simon, and Jonathan Shephard. 1996. The emergence of Rus, 750–1200. Harlow: Longman Group Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Glatz, Ferenc. 2006. A Magyarok Krónikája. [The Chronicle of the Hungarians, in Hung]. Pécs: Helikon Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Gnecchi-Ruscone, Guido A., Anna Szécsényi-Nagy, István Koncz, and 40 Authors. 2022. Ancient genomes reveal origin and rapid trans-Eurasian migration of 7th century Avar elites. Cell 185: 1402–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnecchi-Ruscone, Guido A., Elmira Khussainova, Nurzhibek Kahbatkyzy, and 27 Authors. 2021. Ancient genomic time transect from the Central Asian Steppe unravels the history of the Scythians. Science Advances 7: eabe4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, Jaakko. 2012. Scandinavian Origin of the Rurikid N1c1 Lineage. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/3640214/Scandinavian_origin_of_the_Rurikid_N1c1_lineage (accessed on 10 December 2012).

- Hóman, Bálint, and Gyula Szekfű. 1928–1934. Magyar Történet [Hungarian History, in Hung]. Vol. 1 (1928), Vol. 2 (1930), Vol. 3 (1934). Budapest: Királyi Magyar Egyetemi Nyomda. [Google Scholar]

- Hóman, Bálint. 1943. Geschichte des Ungarischen Mittelalters. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. First published 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Kanyó, Ferenc. 2021. III. Béla, a Legnagyobb Árpád-Házi Király. [Béla III, the Greatest King from the Árpád Dynasty, in Hung]. Available online: https://ujkor.hu/content/iii-bela-legnagyobb-arpad-hazi-kiraly (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Kapitánffy, István. 2010. Hungarobyzantina. Bizánc és a Görögség Középkori Magyarországi Forrásokban. [Hungarobyzantina. Byzantinum and the Greeks in Medieval Sources from Hungary, in Hung]. Budapest: Typotex Kiadó, pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- King, Turi E., Gloria Gonzalez-Fortes, Patricia Balaresque, and 15 Authors. 2014. Identification of the remains of King Richard III. Nature Communication 5: 5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozsdi, Tamás. 2017. III. Béla Magyar Király. (Élete és Uralkodásának Ideje 1162–1196.) [Hungarian King Béla III (His Life and His Reign 1162–1196, in Hung], Private ed.

- Kristó, Gyula, and Ferenc Makk. 1981. III. Béla emlékezete. [Memory of Béla III, in Hung]. Budapest: Helikon Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Kristó, Gyula, and Ferenc Makk. 1996. Az Árpád-ház uralkodói. [Rulers of the Árpád dynasty, in Hung]. Budapest: IPC Könyvek. [Google Scholar]

- Kristó, Gyula. 2007. Magyarország Története, 895–1301. [History of Hungary, 895–1301, in Hung]. Budapest: Osiris Kiadó, pp. 175–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kristóf, Lilla Alida, Zoltán Lukács, and Lajos Patonay, eds. 2017. Szent Király, lovagkirály. A Szent László Koponyaereklye Vizsgálatai. [Saint King, Kinght King. Investigations on the Skull-Relic of Saint László, in Hung]. Győr: Győri Hittudományi Főiskola. [Google Scholar]

- Magdalino, Paul. 1993. The Empire of Manuel Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magocsi, Paul Robert. 2010. A History of Ukraine. The Land and Its People, 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Makk, Ferenc. 1982. III. Béla és Bizánc. [Béla III and Byzantinum, in Hung]. Századok 116: 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Makk, Ferenc. 1985. Hungarian-Byzantine relations in the age of Béla III. Acta Historica Scientiarum Hungaricae 31: 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Makk, Ferenc. 1989. The Árpáds and the Comneni: Political Relations between Hungary and Byzantium in the 12th Century. Chapter VIII: Béla III and Byzantium. Translated by György Novák. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, pp. 107–24. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolmes, Béla Baron. 1937. The Hungarian birthplace of St. Margaret of Scotland. The Hungarian Quarterly 3: 704–715. [Google Scholar]

- Moravcsik, Gyula. 1988. Az Árpád-Kori Magyar Történet Bizánci Forrásai. [Byzantine Sources of the Hungarian History in the Árpád-Age, in Hung]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Morozova, Irina, Pavel Flegontov, Alexander S. Mikheyev, and 12 Authors. 2016. Toward high-resolution population genomics using archaeological samples. DNA Research 23: 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Péter L., Judit Olasz, Endre Neparáczki, and 20 Authors. 2021. Determination of the phylogenetic origins of the Árpád Dynasty, based on Y-chromosome sequencing of Béla the Third. European Journal of Human Genetics 29: 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neparáczki, Endre, Luca Kis, Maróti Zoltán, and 17 Authors. 2022. The genetic legacy of the Hunyadi descendants. 2022. Helyion 8: e11731. [Google Scholar]

- Neparáczki, Endre, Maróti Zoltán, Tibor Kalmár, and 15 Authors. 2019. Y-Chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin. Scientific Reports 9: 16569. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, Henry. 2005. Ancient DNA comes of age. PLoS Biology 3: e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olalde, Inigo, Federico Sanchez-Quinto, Debayan Datta, and 16 Authors. 2014. Genomic analysis of the blood attributed to Louis XVI (1754-1793) King of France. Scientific Reports 4: 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olajos, Terézia. 2015. Bizánci Források az Árpád-Kori Magyar Történelemhez. [Byzantine Sources to the Hungarian History of the Árpád-Age]. Szeged: Lectum Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Olasz, Judit, Verena Seidenberg, Susanna Hummel, Zoltán Szentirmay, György Szabados, Béla Melegh, and Miklós Kásler. 2019. DNA profiling of Hungarian King Béla III and other skeletal remains from the Royal Basilica of Székesfehérvár. Archaeology and Anthropological Science 11: 1345–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrogorsky, Georg. 2003. A Bizánci Állam Története. [History of the Byzantine State, in Hung]. Budapest: Osiris Kiadó, pp. 328–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ottoni, Claudio, Froancois-X Ricaut, Nancy Vanderheyden, Nicolas Brucato, Marc Waelkens, and Rouny Decorte. 2011. Mitochondrial analysis of a Byzantine population reveals the differential impact of multiple historical events in South Anatolia. European Journal of Human Genetics 19: 571–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pályi, Gyula. 2022. A new viewpoint to the Agatha problem: Who was the mother of Margaret, Queen of Scots? Genealogy 6: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamjav, Horolma, and Krisztina Krizsán. 2020. Biologia futura: Confessions in genes. Biologia Futura 71: 435–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickrell, Joseph K., and David Reich. 2014. Toward a new history and geography of human genes informed by ancient DNA. Trends in Genetics 30: 377–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffensperger, Christian, and Norman W. Ingham. 2007. Rurik and the first Rurikids. The American Genealogist 82: 1–13, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rogaev, Evgeny I., Anastasia Grigorenko, Yuri K. Moliaka, Gulnaz Faskhutdinova, Andrey Goltsov, Ariene Lathi, Curtis Hildebrandt, Ellen L. W. Kittler, and Irina Morozova. 2009. Genomic identification in the historical case of the Nicholas II royal family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106: 5258–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisam, Kenneth. 1953. Anglo-Saxon Royal genealogies. Proceedings of the British Academy 39: 287–348. [Google Scholar]

- Sokop, Brigitte. 1993. Stammtafeln Europäerischer Herrscherhäuser. 3. Wien: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Stiernon, Lucien. 1966. Notes de titulature et de prosographie byzantines: Théodore Comnène et Andronic Lapardes. Revue des Étuses Byzantines 24: 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabados, György. 2013. Egy steppe-állam Európa közepén. Magyar nagyfejedelemség. [A steppe-state in the center of Europe. Hungarian Grand Principality. in Hung]. Dolgozatok az Erdélyi Múzeum Érem- és Régiségtárából 6/7: 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Szabados, György. 2016. Könyves Béla király. Egy székesfehérvári királysír azonosításáról. [King Béla of the books. On the identification of a royal grave in Székesfehérvár, in Hung.]. Alba Regia, Seria C 44: 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Szeifert, Bea, Dániel Gerber, Veronika Csáky, and 22 Authors. 2022. Tracing genetic connections of ancient Hungarians to the 6th–14th century populations of the Volga-Ural region. Human Molecular Genetics 31: 3266–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treadgold, Warren. 1997. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 121, 646–666. [Google Scholar]

- Vajay, Szabolcs. 2006. I. Géza király családja. [The family of King Géza I, in Hung]. Turul 79: 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, Gergely I. B., Lilla Alida Kristóf, Kitti Maár, and 11 Authors. 2022. The archaeogenomic validation of Saint Ladislaus’ relic provides insights into the Árpád Dynasty’s genealogy. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. In press, corrected proof. 6 July 2022. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1673852722001795?via%3Dihub (accessed on 16 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Volkov, Vladimir G., and Andrey N. Seslavin. 2019. Genetic study of the Rurik Dynasty. Presented at Centenary of Human Population Genetics, Moscow, Russia, 29–31 May 2019; pp. 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chuan Chao, Cosimo Posth, Anja Furtwängler, Katalin Sümegi, Zsolt Bártfai, Miklós Kásler, Johannes Krause, and Béla Melegh. 2021. Genome-wide autosomal, mtDNA, and Y-chromosome analysis of King Béla III of the Hungarian Árpád Dynasty. Scientific Reports 11: 19210, (Corr.: Idem, Ibid. 2022, 12: Article No. 7157.). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardumian, Aram, and Theodore G. Schurr. 2011. Who are the Anatolian Turks? (A reappraisal of the anthropological genetic evidence). Anthropology and Archeology of Eurasia 50: 6–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, Barbara. 1995. Wessex in the Early Middle Ages. London: A & C Black. [Google Scholar]

- Zsoldos, Attila. 2022. A 800 Éves Aranybulla. [The 800 Years old Golden Bull, in Hung]. Budapest: Országház Könyvkiadó, pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berzeviczy, K.; Pályi, G. King Béla III of the Árpád Dynasty and Byzantium—Genealogical Approach. Genealogy 2022, 6, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6040093

Berzeviczy K, Pályi G. King Béla III of the Árpád Dynasty and Byzantium—Genealogical Approach. Genealogy. 2022; 6(4):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerzeviczy, Klára, and Gyula Pályi. 2022. "King Béla III of the Árpád Dynasty and Byzantium—Genealogical Approach" Genealogy 6, no. 4: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6040093

APA StyleBerzeviczy, K., & Pályi, G. (2022). King Béla III of the Árpád Dynasty and Byzantium—Genealogical Approach. Genealogy, 6(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6040093