Abstract

For more than 3500 years, since Olmec times (1500–400 BC), the peoples of Mesoamerica have shared with one another a profound way of living involving a deep understanding of the human body and of land and cosmology. As it stands, healing ways of knowing that depend on medicinal plants, the Earth’s elements, and knowledge of the stars are still intact. The Indigenous Xicana/o/xs who belong to many of the mobile tribes of Mesoamerica share a long genealogical history of cultivating and sustaining their Native American rituals, which was weakened in Mexico and the United States during various periods of colonization. This special edition essay sheds light on the story of Quetzalcoatl and the Venus Star as a familial place of Xicana/o/x belonging and practice. To do so, we rely on the archaeological interpretation of these two entities as one may get to know them through artifacts, monuments, and ethnographic accounts, of which some date to Mesoamerica’s Formative period (1500–400 BC). Throughout this paper, ancestral medicine ways are shown to help cultivate positive health, learning, and community. Such cosmic knowledge is poorly understood, yet it may further culturally relevant education and the treatment of the rampant health disparities in communities of Mesoamerican ancestry living in the United States. The values of and insights into Indigenous Xicana/o/x knowledge and identity conclude this essay.

1. Introduction: The Indigenous Xicana/o/x Identity

In the process of cultivating their relationship to both the land and cosmology, Indigenous Xicana/o/x educators (IXEs) have wrestled with how to effectively engage the fast-growing and heterogeneous Latina/o population (Flores 2017) while considering the group’s high prevalence for mental health disparities (Diaz and Fenning 2017; Lisotto 2017; Lopez et al. 2012), as well as their own health and well-being challenges while working in spaces of learning (see Caballero 2019; Toscano 2016; Urrieta 2017, 2019; Zepeda 2020). To offer novel solutions for both IXEs and their learners, we add to an ongoing body of work (Garcia 2014, 2019; Garcia et al. 2018; Márquez and Garcia forthcoming) on a more ancestral teaching tradition that will better serve the diverse Native American identities that cross paths in schools, homes, and communities. We draw inspiration from the work of IXEs (e.g., Arce 2016; Cuauhtin 2016; Luna and Galeana 2016; Rodríguez 2017; Toscano 2016; Zepeda 2020), from the insights of the late healthcare practitioner Elena Avila (see Avila and Parker 1999), and most recently, the authors in Medina and Gonzales (2019), who, through various practices, address the mind, body, and spiritual challenges of the day. As previously noted by Garcia (2019), teachers spend a great deal of time with students and, as a result, we stand in a position to model healthy ways of belonging alongside teaching and mentoring. This added teaching duty requires our attention, as students of Mesoamerican ancestry (commonly labeled Hispanic/Latino) have yet to achieve healthy milestones in the areas of health and well-being when compared to Caucasian descent, privileged learners. Specifically, keen knowledge of the Earth and the cosmos, the heart of traditional ritual and ceremony, offer historically marginalized students real-time aid for the prevention and treatment of health disparities, in addition to relevant learning. We embrace ritual and ceremony, as the act of summoning one’s ancestors, along with observing and acknowledging land and cosmology to advance a greater understanding of the human body and its relationship to the Earth’s elements alongside animal relatives. This is a basic human right of Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

In this essay, we begin by highlighting the racist legacy of white supremacy and colonialism in the United States, Mexico, and Central America (e.g., Sánchez 2020) that resulted in the loss of Indigenous peoples’ self-determination through persistent waves of trauma and violence. We argue that it is through the building and sustainment of ancestral knowledge of land and cosmology that we can re-embrace our Indigenous Xicana/o/x identity (e.g., Zepeda 2020), and we wish to further the intersectional learning and the in situ ritual and performance of teachers who embrace such an identity in line with the teachings that surface when humans and the land are in equilibrium. Throughout these passages, we authors write about Mesoamerican ritual and ceremony to reaffirm the Indigenous Xicana/o/x identity, and its tenacity of achieving ancestral and living knowledge to live healthily. From this point on, we shall use Xicana/o/x interchangeable with Xicanx, whereby the big X signifies an Indigenous consciousness, and the little x signifies a full awareness of energies, and expressions regardless of sex, sexuality, and gender (see Medina and Gonzales 2019, p. 3 Introduction, for most recent use).

Thereby, we aspire to reach Native family groups in the USA and Mexico who were forced to rapidly assimilate while enduring the loss of their land and resources. We focus on one area that is important to the Xicanx experience and that has received little attention in spaces of learning––the story of Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, and their conjunction with the planet Venus. The result of this paper proves the vitalness of this knowledge to inform learning content and to build community consciousness, and it highlights the linkages made in ceremony that promote positive identity and good health. We shed light on the origins of ancient sacred tools. We point out that, through time and space, generations of Xicanx individuals have kept their understanding of the human body and how to care for it (at times, unknowingly). This paper stands as one interpretation of our long healing innovations that are critical to our Native American identity.

In moving forward, it is also important to clarify that despite criticism from Natives and non-Natives who refuse to acknowledge the Xicanx tribe as a Native American group (see Cotera and Saldaña-Portillo 2015; Pulido 2015), Xicanx indigeneity rests firmly on four criteria: (1) a significant genetic association with Native American mtDNA haplogroups (A–D and X) (Kumar et al. 2011); (2) a reliance on a maíz diet and the relevant stories of creation (Rodríguez 2014, 2017); (3) familial and ceremonial ties to tribal peoples of the Americas (Avila and Parker 1999; Forbes 1973; Gonzales 2012); and (4) a continuous and intimate relationship with land and cosmology through ritual and ceremony (Medina and Gonzales 2019; Toscano 2016). These tenets should be embraced, studied, and modeled to help all people live better lives. Through interregional interaction, from Perú to Alaska, Indigenous peoples of the Americas share many common ways of being.

2. Native Sources of Knowledge: I/We/Us as a Way of Belonging and Practice

Throughout this paper, we use an I/We/Us Indigenous way of knowing and being (Urrieta 2017) to understand the ancestral and living experiences that Xicanx people share and have in common with other Indigenous groups of the Americas. Such a lens informs and allows us to further our teaching practices that are both traditional and modern. As highlighted by teachers working closely with—and on the ground with—urban school youth, the IXE: (1) is grounded in ritual and ceremony (Toscano 2016; Zepeda 2020); (2) walks with his or her own mirror for constant self-reflection (Acosta 2007); (3) is a cultivator of Panche Be (profound knowledge) (Rodríguez 2017); and (4) serves the Hispanic-Latino community through an Indigenous lens (Cuauhtin 2016; Garcia 2019; Garcia et al. 2018), all while being mindful of the Native peoples whose traditional lands they live in and work on. Most importantly, we engage with the reclaiming and sustainment of the good health stripped from Indigenous peoples through generations of violence. The IXE integrates land-based ways of living, taking care of the body, and passing this knowledge on as learning outcomes. As a research method, Indigenous educators use keen observation, participation, self-reflection, autoethnography, activism, organizing, ritual, and ceremony to achieve positive human health and community. Doing so begins to nurture relationships to ancestral homelands (Moreno-Sandoval et al. 2016). The Caxcan Xicanx scholar Cueponcaxochitl D. Moreno-Sandoval et al. (2016) call on the reawakening of this connection, and the accountabilities to the Earth, and to each other, that come along with it. Thereby, in this essay, our sources of information include history, community, land and cosmology, plants and animals, sacred sites, dreams, ceremony, the archaeological record, codices, traditional language, and colonial documents that allow us insights into who we are and what we can become as Indigenous people.

Cultivating an Indigenous Xicana/o/x sense of self and community grounded in keen ancestral knowledge enriches positive learning and good health outcomes. The richness often stems from a schooling context where IXEs find themselves under attack from the very institutions they work in. In Arizona, for example, parents and high school teachers of the Mexican American Studies (MAS) Program improved classroom attendance, GPAs, and graduation rates (Cabrera et al. 2014). They did so by incorporating the practice of self-reflection through the plight of Tezcatlipoca the Smoking Mirror (Acosta 2007), a philosophy that leads to the acquisition of deep knowledge and the realignment of just values. The entire time, local and state politicians called their curriculums anti-American, and successfully banned books and materials where ancestral knowledge of the Americas was a central theme. Likewise, in Austin, Texas, teachers, students, and Elders created the Academia Cuauhtli (the Eagle Academy), a Saturday morning school that revitalized reciprocal relationships between students, teachers, and community (Valenzuela et al. 2015). This after a call to action by students and teachers to create a more culturally relevant and sustaining learning experience missing in the San Antonio community. The academy modeled curriculums from the eagle’s 360-degree view of the land and the concept of the circle asks that those involved commit to flor y canto (flower and song). This meant beginning units from a place of mutual understanding, dialogue through circular communication, and acknowledging the role that cosmology (i.e., the Sun, Moon, Earth, Venus, etc.) plays in the preservation of human health and wellness. In our present learning community of the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Valley (Gabrielino/Tongva/Kizh territory), teachers from Pre-K to college level, have successfully developed Indigenous teaching materials, i.e., ethnic studies programs with sustained community components. Despite these gains, we are constantly having to justify our content, and effectiveness as urban educators, against a backdrop of right-wing attacks.

In any case, it is common knowledge among urban educators that sustaining ancestral knowledge and culture in both classrooms and community settings, such as the above mentioned, leads to high academic standards and positive social values (Sleeter 2011). Even more so, in Land as Pedagogy, Simpson (2014, p. 23) advocates, “we [should] grow and nurture a generation of people that can think within the land and have tremendous knowledge and connection to aki [land].” Land is both context and process, she tells us, a place where we hold the responsibility to generate meaning in our own lives. Specifically, when recovering from trauma, generating new health is often, though not exclusively, done through ceremony (Simpson 2014). Treatment depends on mediation by way of the Earth’s elements, animal relatives, and cosmos.

Thus, a stronger comprehension of the Mesoamerican material world and of the nuances behind ritual and ceremonial programs (ancient and modern) would grow and benefit community health and schooling programs tremendously.

3. Intergenerational Trauma in the Classroom and the Loss of Native Identity

Early schooling in the Americas physically and mentally harmed the Aboriginal peoples of Canada, Native Americans, and Mesoamerican children and adolescents (Gonzales 2015; Kirmayer et al. 2003; Quijada Cerecer 2013). Spanish missions, Indian boarding schools, and public schooling saw Indigenous ways of living as inferior. Whites framed natives as lesser humans and their cultural ways as less civilized than the “superior” white-European way of life. Sandra M. Gonzales (2015) reminds us that Xicanx individuals had to forcibly uphold not one but two different racial ideologies—the first imposed by Spanish priests and conquistadores, and the second by English settlers and imperialists. Loss of identity through Western schooling prompted Native people to rapidly lose control of their health and spiritual values. Learning conditions for students of Native ancestry throughout the early 1900s favored harsh reprimands, physical violence, and unthinkable crimes. It was common for students to be unwillingly prepared for service in the military and dangerous vocations. As a result, families lost land, resources, and their tribal identities. The reciprocal relationships that their ancestors had created with tribes from distant places became severed. Mothers, fathers, and children became disconnected from the land knowledge of their ancestors. For generations, mobile peoples of Mesoamerica, Xicana/o/xs among them, have endured high rates of stress, anxiety, depression, susto (fear), and severe mental health disorders. These include substance addiction, alcoholism, diabetes, and various forms of cancer (Avila and Parker 1999; Garcia 2019; Garcia et al. 2018). As a community college instructor of ten years, the first author has seen how symptoms of trauma and violence impede student learning and, as a result, destroy critical understandings of who they are. Xicanx students inherit family trauma, unknowingly share it with other students, and experience their own forms of loss and confusion. The severed connection to an Indigenous way of life permeates what Gonzales (2012) refers to as post-Indian stress disorder (PISD), a disordering that she argues strips Native people of their ability to connect with their ancestors’ knowledge needed for their own positive health. Thus, IXEs look in the direction of our most sacred ancestral practices to share with our students and relative communities.

In the following paragraphs, we write about the earliest evidence of Quetzalcoatl and the Venus Star (the planet Venus), which have a history throughout parts of Mesoamerica beginning with the Formative period (1200–400 BC). We shift through the archaeological interpretation of stone monuments, sculptures, and clay pottery of the period that depict the Quetzalcoatl and Venus Star conjunction. The text is anthropological in form. In other words, we emphasize first accounts, and humanistic observations of their unearthing, as a baseline for future interpretations not entirely obvious. Our hope is that by bringing attention to this ancient data, partially found in outdated archaeology books and articles, Indigenous authors can begin to write about them through their own gaze. In addition, we model these sacred material artifacts while considering the emerging social complexity of the Formative period that characterizes this time when life was becoming stratified and advancements in culture noticeable throughout the Mesoamerican region. In addition, we are interested in the large assemblage of portable artifacts that may evince evidence of ritual and ceremonial activities and behavior.

Toward the end of the essay, we draw on a more modern interpretation of combating illness provided by the healing work of María Sabina and the ingestion of the psilocybin mushroom. Sabina, a highland Mazatec curandera of Oaxaca, is credited with introducing the Western world to the mushroom ceremony, and her place in Mesoamerica is widely written and talked about (Martinez-Cruz 2011). We find it beneficial to highlight the health benefits and the research behind psilocybin-assisted therapy. It shows the long-standing medical intelligence underlining certain Mesoamerican curing rituals. As an IXE and anthropologist (first author) and a Xicana art therapist (second author), we concern ourselves with how the ancestral knowledge behind the Quetzalcoatl and Venus story promotes positive health practice, reciprocity, and community interaction. These behaviors, we attest, would be most beneficial to young families and school-age learners. Or, as, the interdisciplinary scholar Paloma Martinez-Cruz (2011) writes, “Mesoamerican and North American spiritualities provide strategies for the decolonial projects of Chicanos and Chicanas” (p. 97), Xicanx individuals included.

4. Introduction to Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, and Venus

On the many horizons of Mesoamerica, from Olmec to Aztec, there lived a patron(s) Quetzalcoatl (Figure 1) whose main avatar was the feathered serpent (Garcia 2011). In Nahua, quetzalli means bird and coatl means serpent (Florescano 1999). In the known iconography of Quetzalcoatl, the elements, and qualities of these two animals significantly stand out. Thus, Quetzalcoatl the feathered serpent stands as a symbol of Earth and sky, time and space, fertility, and creation. A union of all things amazingly human and animal. Scholars of Mesoamerican studies agree that Quetzalcoatl, the masculine, and its various anthropomorphic expressions, played a significant role in the spread of culture and material wealth. Among the Olmec he stood out as a divine person, well garbed, and a guardian of snake medicine. In Classic times (300–700 AD), Quetzalcoatl legitimized the rulership, timekeeping, and creation stories in the modern city of Teotihuacan. In Epi-Classic times (700–1100 AD), it was Cē Ācatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl of Toltec-Tula who introduced different trades and arts to his people and neighbors. Topiltzin was a pillar that promoted peace, non-violence, and self-sacrifice. Later in this epoch, he lost a moral battle with his brother Tezcatlipoca, committed incest with his sister, and, in doing so, taught his community about the coming of age, redemption, and reconciliation. It is said that he vanished to the east and would one day return. Among the Mexica, high priests inherited the title of Quetzalcoatl, and in their everyday lives, they strove to live according to the teachings of the once and future Lord. Today in the sierras of Jalisco, Mexico, traditional healers of the Wixárika community stay devout to the plumed serpent through song, dance, and observations of the Venus Star. In the US, Xicanx artists use Quetzalcoatl as a symbol of precious knowledge in murals, and in the Tucson Arizona MAS program Quetzalcoatl the feathered serpent stood as one of four cultural bearers (Acosta 2007; see also Garcia et al. 2018), among Tezcatlipoca, Xipe Totec, and Huitzilopochtli.

Figure 1.

Quetzalcoatl emanating from the maws of the feathered serpent. Photo taken by 1st author at the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico.

The admiration that the peoples of Mesoamerica had for Quetzalcoatl can be seen materialized in stone. In all major archaeological sites of the Mesoamerican region, Quetzalcoatl and the feathered serpent appear together on sculptures, monuments, and architecture. Inclusively, the feathered serpent was, on occasion, depicted alongside abstract images of the planet Venus—the Venus Star. This union between serpents and stars dates far back into the Formative period, where we can see the two entities carved abstractly on various forms of pottery (Garcia 2011). The archaeological examples of this union appear consistently and are loaded with vast understandings of past human life and how the Earth works. We also see serpents and Venus imagery in a number of Maya codices, interpreted as planting almanacs (Milbrath 2017). These Native American symbols require interpretation by Indigenous intellectuals for a greater good outside of the academy. We stand to learn from the daily interregional interactions that surround the early manifestations of Quetzalcoatl and the feathered serpent—that is, trade, gift-giving, depositing offerings, intimate exchanges, and healing activities. Because Xicanx people are a mobile, varied, and historically displaced population, our replenishment of all things good depends on the recovery of this ancestral knowledge.

In this essay, we focus on three, rare, nevertheless, informing, Formative period Quetzalcoatl sculptures whose symbolism allows insight into the probable role of traditional healers and their associations with serpents and cosmology. We model these sculptures alongside ritual and ceremonial tools of the same period as evidence of the practices of those seeking new values and healthcare. In addition, the second author has made a series of drawings, that we believe bring this forgotten, sacred, ancestral, and historical material to life. Our hope is that we can re-ignite a way of being in all things ancestral where intimacy with the land and cosmos is central to living a healthy life. The first recorded instances of Quetzalcoatl and Venus, we believe, bring about intense thought and medical innovations that the Xicanx community has not fully embraced. Health, healing, and medicine permeated the daily lives of our ancestors, as seen on codices, sculptures, and monuments.

The National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, for example, is full of ancient Mesoamerican libraries that speak of our ancestral daily lives, intellectual pursuits, and medical advancements. Non-Indigenous scholars of Caucasian descent have for the past one-hundred years excavated Mesoamerican cities and households and published in depositories only accessible to scholars with academic privilege, while leaving out Native understandings. Why are these sources of knowledge overlooked in teaching and learning spaces when uplifting our most vulnerable learners? For the Xicanx community, the question of identity, of autonomy, is a question of how the Earth and cosmos, and their material manifestations, kept us alive and well.

5. Quetzalcoatl, the Venus Star, and the Hallucinogenic Mushroom

5.1. Three Rare Quetzalcoatl Sculptures of the Formative Period (1500–400 BC)

In Mesoamerican archaeology, most scholars refuse to use the nahuatl name, Quetzalcoatl, in the Formative period context because the language of the period is not known. In this paper, the name implies a once-living persona(s) who had reached a high degree of knowledge across different horizons. Moreover, as Indigenous authors we are accepting of having to use a nahuatl name to describe deep ancestral knowledge, if it means revitalizing culture from which our children, and students may learn from.

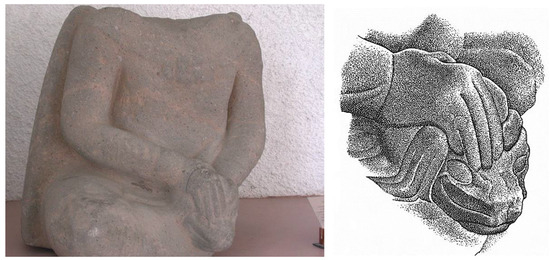

One of the earliest depictions of Quetzalcoatl and the feathered serpent dates to the Early Formative period (1500–900 BC). Unearthed in 1967 and described by Coe and Diehl (1980), San Lorenzo Monument 47 (SLM-47) (Figure 2) portrays the body of an individual who wears two armbands and an elaborate cape that passes below the waistline. The head of the sculpture is missing, and someone has fractured the left knee. Coe and Diehl (1980) unearthed the sculpture, along with other monuments, while conducting excavations in the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan area of the Gulf Coast region. The person shown is a male figure due to his robust upper body. Both hands of the individual are holding the head of a serpent along with the plumes of a bird. San Lorenzo, the site where archaeologists unearthed SLM-47, was the center of early complex life in Mesoamerica (Cyphers 1996). It was home to the Gulf Coast Olmec elite, and, at its height, it was surrounded by sites where commoners lived (Wendt 2010, 2017). During this time, people of all backgrounds from all places of Mesoamerica traveled to and from San Lorenzo exchanging food, pottery, obsidian, greenstone, and massive amounts of basalt.

Figure 2.

Left—San Lorenzo Monument 47 (SLM-47). The first known sculpture of Quetzalcoatl and the feathered serpent in the Americas. Found at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan in the Gulf Coast of Mexico. Museo Comunitario de San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan. Photo taken by the Olmec archaeologist Hirokazo Kotegawa. Right—Close-up of the serpent and its “hand-paw-wing” as seen on SLM-47 in Coe and Diehl (1980). Take notice of the feathers intentionally placed above the head of the serpent. Why this conjunction? Why join feathers and serpents?

One of the most unique pieces of information that stems from SLM-47 is the carved snake head cradled by the hands of the sculpted figure. A detailed drawing in the Coe and Diehl (1980) volume reveals the head of the snake topped with the feathers of an unknown species of bird: perhaps the quetzal bird. Thus, we have an early bird–serpent conjunction present with the likes of someone special. It is well known that the snakes of the Gulf Coast, the fer-de-lance particularly, are among the deadliest in the world. Their venom causes severe tissue necrosis, and bite victims often lose body parts, if not their lives. Snake handling is typical around the world, although it is usually associated with well-trained specialists and people with keen knowledge of snake behavior and of the potent venom. In Mesoamerica, it is highly likely that training with snakes and birds began early and was practiced by a select few.

The feathered serpent and Quetzalcoatl also appear on La Venta Monument 19 (LVM-19) (Figure 3). On this monument, you can see both entities suspended in flight whereby the avian serpent cradles the patron in midair. Quetzalcoatl wears a serpent headpiece, a multilayered faja (belt), fitted huipil (shirt), and an elaborate cape. He carries a medicine bag in his right hand (Drucker et al. 1959). Karl A. Taube (1995) argues that the two birds facing two cross bands above the persona represent a name glyph signifying Earth and sky, and, in turn, an avian serpent. Unlike San Lorenzo, La Venta dates to about 900 to 400 BC, and stood as the Olmec civic-ceremonial center of the period. Like its predecessor, San Lorenzo, La Venta and its area was an Olmec site of complexity and emergence. Crafts people from all over Mesoamerica took precious goods to the site, and excavations have revealed sophisticated mounds, stone monuments, precious greenstones, and obsidian deposits. During this period, people carved and painted images of winged serpents and their close human counterparts deep inside caves and on rock walls in key sites, such as Juxtlahuaca and Oxtotitlán.

Figure 3.

Left—The feathered serpent and Quetzalcoatl as seen on LVM-19. Photo taken by 1st author at the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico. Right—Rendition of Quetzalcoatl and the feathered serpent. Take notice of the name glyph made up of two Xs and two birds. Taube (1995) believes this stands for an early writing script associated with avian serpents. Abstract Xs and birds we also see them on pottery of the same period. Drawing by 2nd author.

We believe that a major theme behind LVM-19 suggests travel, reciprocity, and medical innovations not yet understood. Why off his feet? What does he carry? Where is he going? Whoever carved LVM-19 was intent on showing him as well adorned, well dressed, and carrying an assortment of sacred tools. The details express a time of exchange, learning, and innovation.

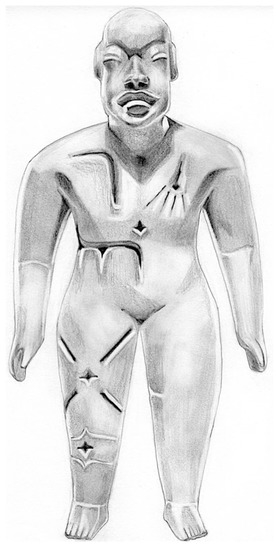

One can also see the union between power, status, and serpents on Laguna de los Cerros Monument 19 (LCM-19). LCM-19, a sculpture carved in the round Olmec style (Figure 4), depicts a male figure standing in an upright position with his arms crossed. He wears an elaborate belt and an elongated cape that surpasses the knees. The cape is an early hallmark of the Quetzalcoatl tradition, and, in this case, it has three serpent heads carved on its right side. The person(s) that carved the serpents did so in a style distinct to the Early Formative period, found on the pottery of San Lorenzo and at the site of Tlatilco. Based on the large amount of basalt found at Laguna de los Cerros and its surrounding cites, archaeologists believe it served as an important administration and basalt-carving center between the larger San Lorenzo and the key Olmec sites of Las Limas, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes. The unknown identity of the person embodied on LCM-19 is a question of interest and is necessary to understanding the relationships between people of status and commoners during the Formative period. Specifically, we highlight here the shared clothing styles seen on SLM-47, LVM-19, and the LCM-19 monument. Fajas, capas, y serpientes (belts, capes, and serpents) dominate the dress of Quetzalcoatl. In Garcia (2011), the first author noted that Susan Gillespie (2008) also pointed out the relationship between “bird-serpents” and men of status carved on monuments from Guerrero and Chalcatzingo, which are key sites and regions outside of the Olmec Heartland. One of these, but not the only one, the San Miguel Amuco Stela, shows a male figure wearing a bird-mask, a long cape, and both holding with his arms and carrying on his back bundles of feathers. The imagery of LCM-19, again, we believe, shows the role of serpents in their ability to legitimize divine status, medicine, and authority.

Figure 4.

Left—Laguna de los Cerros Monument 19. An early representation of how people used serpents to legitimize their status and identity. Photo taken by Hirokazo Kotegawa at the National Museum of Anthropology, Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico. Right—Rendition of LCM-19 showing three serpent heads carved on the right-side view of elongated cape. A head added to the drawing brings the full character of Quetzalcoatl to life. Drawing by 2nd author.

5.2. The Venus Star of the Formative Period (1500–400 BC)

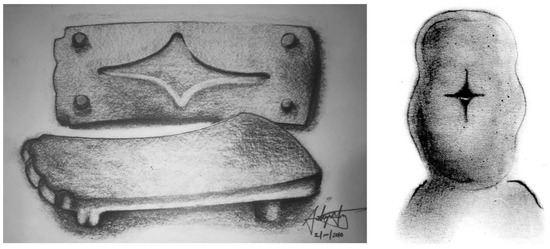

In a talk given at Cal State LA (Garcia 2012), the first author showed that the name glyph pointed out by Taube (1995) on LVM-19 can also be seen on clay pottery of the period, and that it may have been part of a medical tradition associated with observations of the planet Venus. Like abstract images of the feathered serpent, people of early Mesoamerica carved Venus on serving ware, clay figurines, and stone paraphernalia (Figure 5). We suggest that these concerned an assemblage of ritual and ceremonial ware dedicated to night-time cosmology. Jeffrey P. Blomster (1998) argues that Olmec-style baby figurines that had the Venus motif carved on the posterior part of the head may belong to a regional cult that connected important centers of the Early Formative period. Blomster (1998, 2002, 2010) notes that regional cults, unlike major religions, own no permanent structures, gather in remote sacred sites, adopt people of all ethnic and racial backgrounds, and spread their values through mobile objects.

Figure 5.

Left—Rendition of portable metate with the carved Venus Star on its underside. Drawing by 1st author after Guthrie (1995, p. 291). Right— Rendition of Olmec-style figurine head with the Venus Star carved on its posterior part. Drawing by 2nd author after Coe and Diehl (1980, p. 267).

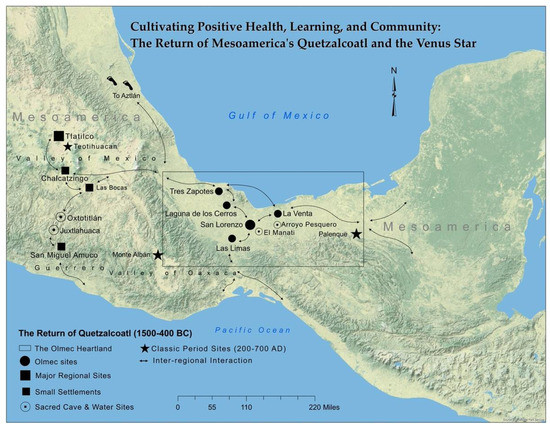

During the Formative period, a part of the interregional interaction between people included making long voyages to deliver offerings, gift-giving, trading goods, making alliances, and obtaining medicine, of which there exists widespread evidence. Sites lacking permanent living structures, such as El Manatí (Ortíz and Rodríguez 2000), Arroyo Pesquero (Wendt and Reyes 2011; Wendt et al. 2014), and the cave sites of Juxtlahuaca and Oxtotitlán outside the Olmec Heartland, hold ritual deposits (i.e., human bones, polished stone masks, maíz artifacts, etc.), and evidence of winged serpents in the form of murals and carvings. In Garcia (2011), the first author describes the assemblage of “cult ceramics” as part of a multi-regional network of people with winged serpents, the two-way exchange of gifts, and the exchange of medicine as its central philosophy (Figure 6). A significant survey of artifact illustrations in Guthrie’s (1995) Olmec catalog attests to the extent of this healthcare movement. Items include unique spoons, containers in the shape of plants and animals, perforators, incised celts, gemstones, pestles, grinders, mirrors, metates, and fetus figurines. Gone from the record, but highly valued in curing ceremonies, medicine people would have also carried feathers belonging to eagles, hawks, and owls, in addition to handkerchiefs, medicine bags, and baskets made of natural materials.

Figure 6.

During the Formative period (1500–400 BC) the return of Quetzalcoatl involved a multi-regional network of wing-serpents, accountabilities, and the exchange of medicine. Best described as a healthcare movement, through inter-regional interaction people exchanged an assortment of portable and precious objects. Taking advantage of archaic trading routes, they effectively traveled prolonged periods and fulfilled local and regional responsibilities. Along the way, they left offerings at sacred sites, hunted for survival, and gained a keen understanding of the land and cosmology. Quetzalcoatl, in the role of medicine man, artisan, and custodian of the land, offered spiritual guidance, comfort, and traditional healing ways. This story informs all Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Regional map showing corridors of human interaction created by 1st author using ArchMap™.

The interaction of communities from different regions alongside the veneration of the feathered serpent and Venus played a significant part in the lives of people beyond the Formative period. Ringle et al. (1998) have shown that the spread of a regional cult based on the return of Quetzalcoatl and his association with power, time, and space may have been behind the spread of culture after the fall of Teotihuacan (c. 600 AD) during the Epi-Classic period (700–950 AD). Ringle et al. (1998) suggest that, during this time, leaders of important sites began to revitalize and reanalyze Quetzalcoatl’s primordial role as a creator. In Teotihuacan, the Temple of the Feathered Serpent shows the deity submerged in the watery underworld and wearing the headdress of the cipactli (primordial crocodile), associated with calendrics (Sugiyama 2005). In the many story lines of how Mesoamerica came to be, Quetzalcoatl helps to create the world, and is therefore associated with time, space, and calendrics. In one example, Quetzalcoatl journeys to the watery underworld to retrieve the bones of once-living people. There he asks the Lord of the Underworld Mictlantecuhtli for the bones of earlier people only to find himself having to run off with the bones without permission. Stopped in his tracks as he flees, he drops the bones, causing them to break into pieces. His quick and savvy thinking leads him to sprinkle the bones with his own blood and thus that is why humans are born in all shapes and sizes. Illustrations from the Epi-Classic period from various sites show Quetzalcoatl in different forms, parting the heavens and the Earth and sustaining daily and nightly intervals. He stands in proximity to the symbol for Ollin (movement) and the stylized Venus glyph.

But why the planet Venus? Why did Mesoamerican people choose to materialize Venus and aspects of Quetzalcoatl next to one another? Venus appears on the Western horizon, never veering farther than 47° from the base of a sunset. To the observant sky watcher, Venus then disappears with the movement of the Earth, only to reappear in the Eastern horizon, two hours before sunrise. The planet Venus stands out from smaller true stars as a larger, twinkling, and four-cornered “star” with a clear brightness. In astronomical terms, the brighter the object, the lower the magnitude, and on a scale of 1 to 6, Venus is a −4.8 at her maximum. Venus’s observational parameters are posted and updated online (https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/venusfact.html accessed on 12 March 2021) by Dr. David R. Williams of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. In the material culture of Formative Mesoamerica, the brightness of Venus is shown as an incised line, or sometimes carved, immediately following the four ends of the abstract Venus Star. The female clay-figurine from Las Bocas (Figure 7) in Guthrie’s (1995) catalog materializes these early morning and evening phenomena. Serpents, stars, and comets, together, on small objects, are suggestive of talks and human activities that placed a high value on the sacred and natural landscape. Richard L. Lesure (2004) makes the point that Olmec-style objects do not simply evince a two-way relation between a person and their gods, but a three-way conversation between a person, the gods, and other people. When in unison, winged serpents and Venus legitimize the empathy and admiration present during important exchanges between people, taking place during scheduled intervals, and marked by the different phenomena that one sees when looking at the night and early morning sky.

Figure 7.

A rendition of the female clay-figurine from Las Bocas in the Valley of Mexico (see Guthrie 1995, p. 314) showing multiple forms of night and early morning imagery. We see stars, comets, and full constellations. Among these are the Venus Star. Such pieces of pottery represented both planting guides, and precious gifts, shared among early Mesoamerican people. Drawing by 2nd author.

There is more. Anthropology and Xicana/o/x Studies Professor Gerardo Aldana (2005) notes that one single sky watcher, over an eight-year period, could gather enough data on Venus to plan ceremonies that would have fallen in line with the observable phases of the planet. In times of need, one looked toward the sky for answers (Aldana 2005), surely after a long and emotional journey, after one has wept, and a new life begins. In this regard, with the aid of mind-altering plants and drinks, and knowledge of the stars, Quetzalcoatl may have led ceremonies where new meanings and experiences overtook the body, and old ones left forgotten (Figure 8). Portable archaeological evidence pointing to such a tradition beginning during the Early Formative period (1500–900 BC), supports this as having been practiced. In other aspects, the Madrid Codex of the late fifteen century informs us that ancient Maya agriculturalists saw Venus cycles and phases as indicators of when to plant corn (Milbrath 2017). By studying Madrid pages 12b to 18b, Susan Milbrath (2017) found a 260-day planting cycle spanning from February to October, marked by Venus phases, a rain-making God, and a serpent known as Chicchan. The months available to plant coincide with those of modern Maya planting months, and current understandings of Venus needed to figure out the number of crops to plant per season, according to Milbrath. Still, among the Wixárika, Venus and plant knowledge intimately guide ceremonial life. The name for the squash flower is xewa, the same name for Venus. Stacy B. Schaefer (2015) tells us that women elders speak of the rising of Venus at dawn, in the east, just as squash flowers start to bloom in the middle of August. Such land and cosmic observations are crucial to the naming of newborn children. Our son, for example, was given the Wixárika name Tutukila by his grandfather elder Matsiwa de La Cruz. The name signifies all of the elements, the winds, the smells, the thunder, that come before the rain. It came to Matsiwa in a dream, after a night of stargazing, before the fire, and just before our son was born in early February, during the rainy season in California. The naming ceremony was video recorded to conserve the coming-of-age story of our newborn son. It may be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s_sIaG2NJH8 (accessed on 28 March 2021).

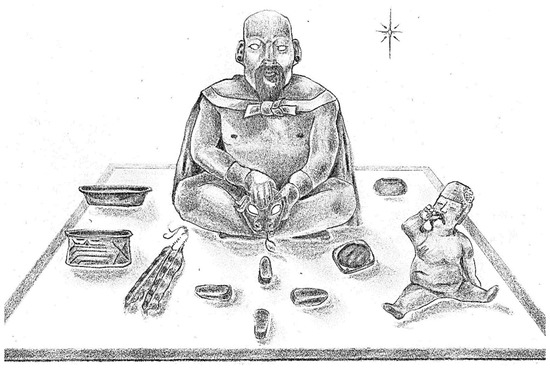

Figure 8.

Rendition of Quetzalcoatl and the feathered serpent as the two may have led ceremonies during the Formative period, shown with an array of Native tools and medicine (i.e., carved pottery, raptor feathers, greenstones, mirrors, and hollow clay figurines) mentioned in this paper. In Márquez and Garcia (forthcoming) we write how such sacred tools are used at the modern household and family level. Drawing by 2nd author after observing a series of Early Formative artifacts.

5.3. Quetzalcoatl, María Sabina, and the Hallucinogenic Mushroom

In Mesoamerica, the healing of the human body through the ingestion of medicinal plants, and cactus, has deep roots and continues to the modern day. Archaeological research in Texas and Mexico on the mind-altering peyote cactus and its related tool kit shows that it was in use 7000 years ago. In the Gulf Coast specifically, Kent, F. Reilly (1995) has pointed to a large ritual and ceremonial complex of sculptures, pottery, and portable greenstones that evinces the “trance journey” associated with healing activities of the Formative period. Upon his arrival to the Americas, the Franciscan Friar, Bernardino de Sahagún (1950), noted a vast number of plants and animals used in the curing of certain aliments. Regarding mushrooms, the friar wrote that they grew beneath the hay in fields, were round with tall stems, that people should not eat more than three, and that ingestion caused drunkenness, visions, and a rapid heartbeat.

Mushroom use and Quetzalcoatl have a history together. In the Codex Vindobonensis, folio twenty-four shows a procession of prominent ancestors (i.e., Xochipilli, Quetzalcoatl, and Tezcatlipoca), each one holding their own “offering” of hongos and water lilies (Emboden 1982). In the group, one can see a fellowship of prominent relatives and their distinct expressions. During the ritual, people gather medicine, exchanges take place, and Quetzalcoatl, wearing an ehecatl-wind mask, carries a woman believed to have been unresponsive. Gastón Guzmán (2016) believes the participants tell of a tradition that used mushrooms of the zapotecorum species. In a separate example, Guzmán (2012) found Psilocybe zapotecorum symbolism on clay-figurines from the Capacha culture of Colima, where individuals with serpent-like arms stand together venerating the mushroom and a traditional healer, which Guzmán identifies as Quetzalcoatl. The Capacha figures stand interlocked at the arms, their eyes sit above their orbits, and they overly stare at an oversized capped fungus. Guzmán (2012) interprets the behavior displayed by these figurines as classic symptoms of neurotrophic mushroom use among community.

More modern examples of mushroom healing are known. In the May 1957 issue of Life, Robert G. Wasson published the details of his own mushroom experience with the Mazatec healer María Sabina. Although not the first recorded mushroom ceremony, Wasson’s story allowed us insight into one of the world’s most sacred ways of combating illness. The first accounts published in the Life publication reads as follows: “The Indians were wearing their best clothes, the women dressed in their huipil or Native costumes, the men in clean white trousers tied around the waist with strings and their best serapes over their clean shirts” (Wasson 1957, p. 109). Prior to the ingestion, the group of twenty drank chocolate. In the presence of mushrooms, no one spoke vulgarities, and all was silent and sacred. At about 22:30, Sabina began to clean the mushrooms of their dirt. With chants and copal smoke, she blessed the medicine and handed it to the group in pairs of two. At midnight, Sabina put out the last of the candle fire with flowers pulled from the altar and all became dark. Wasson wrote that although he was determined to fight the effects of the medicine, at about half an hour post-ingestion, the visions began:

They emerged from the center of the field of vision, opening up as they came, now rushing, now slowly, at the pace that our will chose. They were in vivid color, always harmonious. They began with art motifs, angular such as might decorate carpets or textiles or wallpaper or the drawing board of an architect. Then they evolved into palaces with courts, arcades, gardens—resplendent palaces all laid over with semiprecious stones.(Robert G. Wasson 1957, p. 109)

Over the course of two nights, Wasson ate mushrooms and saw visions to the sound of Sabina’s singing and hand clapping. She intensified the ceremony with an invocation to the medicine, the land, and nighttime cosmology (Wasson 1957), first announcing her own good intentions, then continuing to antagonize faulty spirits. In the 1957 article, Wasson notes that no science of the day spoke of the mushrooms’ qualities that cause one to see visions. A part of his testimony only details how mushrooms must be treated with great reverence, and even among the Mazatec, he notes that they are not to be eaten for excitement, and that their use was delicate.

In Women and Knowledge in Mesoamerica: From East LA to Anahuac, Paloma Martinez-Cruz (2011) published a similar but more extensive account of the mushroom ritual, as officiated by the Mazatec chamana Doña Augustina Martinez, in the context of globalized flows of culture, money, and people of Caucasian descent seeking God, noting further a key aspect of the mushroom’s curative ability to help people surrender the ego and selfhood. Moreover, the text explores the impact of colonial Spanish and Indian invasions, and men-centered notions of female Indigeneity, on woman healers of Mesoamerica, analyzing further the ethical challenges and complexities of Sabina and Martinez who thrived in the modern world, despite abuse and attacks on their personhood.

5.4. The Therapeutic Benefits of Mushroom Medicine (What Our Ancestors Already Knew)

More than 60 years after the 1957 Wasson article, a host of pharmacological and therapeutic knowledge concerning mushroom use has surfaced. Psilocybin is the main compound in neurotrophic mushrooms (Guzmán et al. 1998). Upon ingestion, conversion into psilocin occurs, which then bonds to serotonin (5-HT) neurotransmitters found in the gastrointestinal tract (the stomach), blood, and nervous system. The bonding evinces neurotrophic effects (Nichols 2004). A summary of intoxication by Tylš et al. (2014) describes changes in belief, changes in body image, impaired feeling of time and space, thought content disorder, and symptoms of anxiety or elation. A study of fifty individuals by Kometer et al. (2015) found psilocybin to affect portions of the brain that induce insightfulness and spiritual experiences. This may be linked to the increased retrieval and reattribution of autobiographical information during visual hallucinations (Kometer et al. 2015). In a second study of thirty-two individuals, Pokorny et al. (2017) found that psilocybin significantly increased emotional empathy. All subjects scored high on the Interpersonal Reactivity Index questionnaire that measures trait empathy through four subscales: perspective taking, fantasy, empathetic concern, and personal distress. Of significance was that “Posthoc tests revealed that participants had slightly higher scores in their second test session compared with the first test session independently of drug condition and administration order” (Pokorny et al. 2017, p. 753). The findings are in line with those of Zamaria (2016), who reported persisting positive changes in the mood, and behavior of individuals fourteen months after first consuming psilocybin. Brain studies using MRI technology show that psilocin, when coupled with psychotherapy, is effective in treating moderate to severe depression (Carhart-Harris et al. 2012; Roseman et al. 2018). Psilocybin and psychotherapy provide relief for anxiety, depression, and end-of-life feelings associated with cancer (Belser et al. 2017; Swift et al. 2017). Quitting alcohol and tobacco may also be progressed with psilocybin-assisted treatment models (Bogenschutz et al. 2015; Johnson et al. 2014). In a study of 21,967 respondents, its findings concluded that mushrooms and peyote are not a risk factor for mental health problems (Krebs and Johansen 2013) but are tied to positive health outcomes.

Because psilocybin works in the treatment of illness and trauma symptoms, its controlled prescription may develop as a culturally relevant form of mental health care. Such prescribed treatments are still rare in the United States, widely available in Europe, and common in Mesoamerica. Sorting through the ethical challenges may prove difficult, however the benefits of seeing such through would be a breakthrough in battling sickness among Indigenous peoples. Emotional empathy, for example, the ability to understand the mental states of others, is important in the maintenance of relationships, and plays a key role in prosocial behavior (Pokorny et al. 2017). According to Baron-Cohen (2012), those of us who lack empathy may often withdraw and have difficulties in interactions that involve communication and reciprocity. Empathy promotion through psilocybin medication, thus, may serve mental health services in clinical and non-clinical settings, where communication, understanding, and reciprocity are favored traits of getting well. In Zamaria’s (2016) study of the positive and persisting effects of psilocybin, six of the eight participants described experiences in which there was a dissolution of the ego toward a greater connection to other people, along with profound shifts in attention and increased introspection. Even though clinical studies prove psychedelics do not cause mental health problems (Krebs and Johansen 2013), in the United States, the DEA lists psilocybin as a controlled substance, alongside cocaine and heroin.

6. Conclusions: The Values and Insights Gathered from the Return of Quetzalcoatl

By generating interpretations of how the peoples of Mesoamerica partook in certain rituals and ceremonies, one uncovers a host of important values and insights. We find the details of long-held Indigenous knowledge useful in the cultivation and sustainment of good health, learning, and community. At this point in our Xicana/o/x history, we are certain of having to re-create our ancient stories if it means better learning and health outcomes for school-age learners. Rodríguez (2019) made this point at a Los Angeles Association of Raza Educators meeting when talking to a cohort of teachers. This meeting is available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZCBG67yZpCs (accessed on 18 March 2021), and it occurred on June 9, 2019. Surprisingly, the maíz scholar was talking about Quetzalcoatl, and how, when instructing children, he generates his own parts of the story to achieve certain lessons. He said:

All storytelling, I’m sure you all know. It’s not one story; it’s adapted everywhere. You know, wherever you are. Throughout the ages. And so, the issue here was about the ants. Is how come they refuse the maize to Quetzalcoatl. And I asked all the elders that I’ve ever met, that told me the story, and the elders said nobody ever told us why the ants said no. And then I said, well, I’m going to give the answer. Nobody has ever told me that I couldn’t give the answer. But I asserted it because I said I am part of this culture, I’m part of maíz culture. And the simple answer was that the ants were worried that we were going to capitalize on the maize. That we were going to sell it, store it, be greedy with it. And then make monster corn out of it. You know. So, the little kids they performed that.(Rodríguez 2019, 0:23–1:14)

To this end, we authors believe the responsibility rests with each IXE, in their own schooling context, to adapt and interpret our ancient stories and materials in a positive and polite manner. In 2015, for example, the first author and a cohort of community college students started the Mesoamerican Figurine Project of Rio Hondo College. Through a learning of Mesoamerican clay-figurines students embarked on a series of assignments that bridged ancient clay-work and therapeutic models, all while meeting the required classroom learning outcomes. Since the project’s first start, the work has gained major funding through a Mellon/ACLS grant, and the teaching strategies have grown to include the importance of sustaining Indigenous life ways outside of the classroom. The project website (http://www.mesofigurineproject.org/ accessed on 28 March 2021) houses a growing list of co-authored publications, and examples of Indigenous Xicana/o/x Educator practices.

Through the return of Quetzalcoatl, learners engage the supernatural, an impossible animal made real. We learn of the values concerning flight—the cape, the faja, and the fitted huipil—of the relationship between the healing body, birds, and serpents, and the bond that this medicine fosters. Evidence of long travels, gift-giving, sacrifices, and medicine are at the heart of this story. Through Quetzalcoatl, we see an admiration for the planet Venus in its bright life-giving form, deep on the horizon: once as the evening star appearing in the West, and later as the morning star appearing in the East. We learn to gather at night before the fire, in front of altars, to look beyond ourselves, to see ourselves as one. In doing so, we welcome the promises of good health, witness miracles, and in the morning sunrise, invite a new day. Quetzalcoatl breathes learning, is the one who secures medicine, is a cantador like María Sabina, and sometimes stands the most hurt from prolonged walks and sleepless nights. The healer is erratic and troublesome, but a reminder of what Indigenous people stand to lose, or not to learn, when we do not have a relationship with the land. When talked about collectively, Quetzalcoatl encourages learning, mobility, interaction, and the exchange of medicine. In the classroom, Quetzalcoatl serves to both fit and realign specific learning goals.

When Gordon G. Wasson (1957) published his accounts of the velada ceremony in Life, the Western world knew little about the benefits of the Psilocybe mushroom and of psilocybin, its main neurotrophic compound. What scientists in laboratories found groundbreaking and true, Indigenous peoples of the Americas had in store for thousands of years; certain plants allow us, as they did our ancestors, clarity, mindfulness, and new avenues to thrive on. María Sabina shared important protocols concerning ceremony: the preparation and blessing of the medicine, the summoning of ancestors, and the aggressive combating of illness, the role of the community in getting well, how we dress in our best to hold space, how we scold one another for our drunkenness, and how we uplift each other with a smoke before denouncing the pain. María Sabina, shot, ripped off, and beaten, paid a heavy price when taking on the healing work. Though she was also a victim of Indigenous, and modern forms of violence at the hands of men. (see María Sabina—Mujer Espíritu in English: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-yGNWBEwvlU).

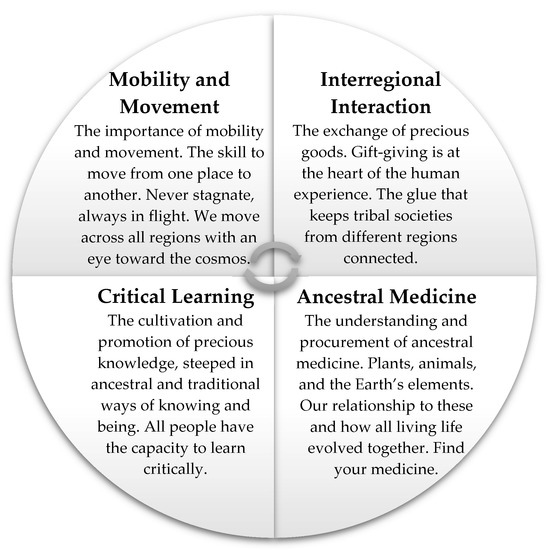

These values and insights—the ritual and ceremonial knowledge that we write about in this paper—inherently fall under the care of the Indigenous Xicanx community, and relevant Native groups. By not embracing sacred knowledge now, we lose it forever, further undermining our health, and well-being. These provide: (1) critical learning content required to build individual aptitude; (2) an understanding of mobility and movement to sustain keen knowledge of the land and cosmos; (3) the benefits of interregional interaction (carrying cargo responsibilities); and (4) real-life thought and practice concerning ancestral medicines. We refer to these four values as the Wheel of Quetzalcoatl (Figure 9). They stand for the nuances of an Indigenous education that sustain culture in the home, in the community, and in schools, outside of monocultural norms of achievement (Paris and Alim 2014). To aid learners with problems beyond the classroom, one can recite narratives of the ancient past, share personal stories, draw from metaphors, and explain the potential for peace, new meaning, and how to reconcile. When in need, our ancestors may be summoned for help, and both teachers and students can expect a response. Such as with the feathered serpent, many of us embody an array of feminine and masculine energies, anatomies, and expressions. Such keen ways allow us the ability to contact our ancestors in the spirit world and to talk with animal relatives. For an in-depth read concerning the fluidity of gender, and the complementary feminine and masculine energies in the realm of healing, and medicine, see Medina and Gonzales (2019). At times, the prescription of plant medicine surfaces in a safe way. Only the fire is above us, under the stars we are all one, and no one’s pain is greater than anyone else’s. These values and insights serve the Xicana/o/x community in regaining a grip on their healthcare and on who they are.

Figure 9.

The Wheel of Quetzalcoatl revolves critical learning, mobility and movement, interregional interaction, and ancestral medicine. These stand for an array of teaching units (a familial place of belonging and practice) that cultivate positive health, learning, and community. The model is culturally relevant, encourages healing ways, and revitalizes and sustains the ancestral outside of the classroom.

7. Final Thoughts: Cultivating Positive Health, Learning, and Community

That modern Indigenous peoples of the Americas continue to interact steadily, as our ancestors once did, throughout vast corridors, regardless of blood quantum, is evidence of our ability to adapt alongside cosmic pathways. The thought and practice of medicine in diverse contexts for thousands of years leaves us with an untapped consciousness of how to take care of the body. One might say that the sacred tools needed to study ourselves—our communities—have gone ignored. They have! The queer Xicanx Indígena, and scholar, Suzy Zepeda (2020), has argued that the school of Chicano studies suffers from susto, a form of deep fear, and that somewhere in the launch of land-based heteropatriarchal goals, structures created a “distance from knowing and working with spiritual lineages and complex historical narratives…” (p. 225). These structures, she argues, closed pathways that would have led toward healing colonial forms of violence alive in our movement. In line with the goals of this article, Zepeda argues for a “spirit praxis” of ancestral wisdom and sabiduría that was either left out of Chicano studies, or simply not considered rigorous or intellectual. These are needed for tribal conflict resolution and for community building across regions. It is our hope that students and teachers will find it worthwhile to keenly examine profound parts of the Mesoamerican body (see Garcia et al. 2018) and its relationship to the Earth and cosmos. As this way of living summons ancestors, then those involved must tread carefully by asking for permission, finding meaning in situations that hurt us, working more effectively with others, making generous offerings, and giving and receiving medicine. With vision and collaboration, the following extensions of an escuela Quetzalcoatl are foreseeable:

- The creation and furthering of community medicine (i.e., projects) where the original inhabitants and caretakers of the land are consulted and considered beneficiaries.

- The creation and furthering of Indigenous/Native centered schools where original inhabitants are acknowledged and remain part of the health and learning goals.

- The creation of undergraduate and graduate degrees in Mesoamerican studies steeped in rigorous theory and methods and made accessible to those of all backgrounds.

- The revitalization and sustainment of ritual and ceremony in line with both traditional and modern ways of getting well, alongside the proper stakeholders.

- The creation of an Indigenous Xicanx science, medicine, and technology journal for the advancement of Native American knowledge for the betterment of all living people.

In this essay, we described how an understanding of Quetzalcoatl and Venus stands supported by 3500 years of ancestral knowledge. This is not religion, nor is it mythology, but it is a way of existing where all living organisms are healthy because they are related and help one another. Within reach of the IXE lies a wealth of content helpful to create lessons, develop curriculums, and meet the related student learning outcomes. We meet our greatest challenges not only in our schools, but inside our very own homes, in the mirror of Tezcatlipoca, and in our neighborhoods. We therefore pose the question: Who intervenes, mediates, and medicates on behalf of the incarcerated, deported, unsheltered, elderly, and severely sick? As our Native children are born and families continue to grow, matters of education must encompass the intricacies of ancestral medicine, ritual, and ceremony. How shall our own households unearth and practice a more ancestral mental health model to mend and sustain their Native identities?

Lastly, and with concern to Xicana/o/x notions of Aztlán as a place of identity. It has been repeated on social media outlets that Aztlán does not exist as an Indigenous Xicana/o/x site of convergence. That such is mythology and not real. That claim is a false understanding. Let us be reminded that territories such as Aztlán (the American Southwest), similar to the Olmec Heartland (Figure 6), must not be separated from their corresponding corridors. Indigenous peoples have long relied, and still do, on the trajectory of the Sun (East to West), the positioning of the stars, along with ancient Northern and Southern trade routes for hunting, pilgrimage, and travel. Archaeologists understand keenly that Aztlán is not a mythical site but a place of migratory, cultural exchange, and linguistic interaction (Kemp et al. 2010; Smith 1984), areas where native people are born, meet, depart from, and return to. Aztlán stands as a site of diverse human creation and expression, not folklore, severed by European conquest and colonization, and severely misunderstood by scholars who rely on Western lenses.

Author Contributions

Visualization, C.I.M.; Writing—review & editing, S.A.G. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the American Council of Learned Societies through a 2019 Mellon/ACLS Community College Faculty Fellowship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editors of the special issue “Identity and Community” for their generous support to make this article available to everyone. We would also like to thank the American Council of Learned Societies for their support so that we could complete the research in this paper on time. We acknowledge our three children, and our families here in the US, and in Mexico, whom we love dearly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acosta, Curtis. 2007. Developing Critical Consciousness: Resistance Literature in a Chicano Literature Class. English Journal 97: 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldana, Gerardo. 2005. Agency and the “Star War” Glyph: A Historical Reassessment of Classic Maya Astrology and Warfare. Ancient Mesoamerica 16: 305–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, Martin Sean. 2016. Xicano/Indigenous Epistemologies: Toward a Decolonizing and Liberatory Education for Xicana/o Youth. In “White” Washing American Education: The New Culture Wars in Ethnic Studies. Edited by Denise M. Sandoval, Anthony J. Ratcliff, Tracy Lachica Buenavista and James R. Marin. Santa Barbara: Praeger, vol. 1, pp. 11–41. [Google Scholar]

- Avila, Elena, and Joy Parker. 1999. Woman Who Glows in the Dark: A Curandera Reveals Traditional Aztec Secrets of Physical and Spiritual Health. New York: Tarcher/Putnam. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, Simon. 2012. Zero Degrees of Empathy: A New Theory of Human Cruelty. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Belser, Alexander B., Gabrielle Agin-Liebes, T. Cody Swift, Sara Terrana, Neşe Devenot, Harris L. Friedman, Jeffrey Guss, Anthony Bossis, and Stephen Ross. 2017. Patient Experiences of Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 57: 354–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomster, Jeffrey P. 1998. Context, Cult, and Early Formative Period Public Ritual in the Mixteca Alta: Analysis of a Hollow-Baby Figurine from Etlatongo, Oaxaca. Ancient Mesoamerica 9: 309–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomster, Jeffrey P. 2002. What is the Olmec Style? Regional Perspectives on Hollow Figurines in Early Formative Mesoamerica. Ancient Mesoamerica 13: 171–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomster, Jeffrey P. 2010. Complexity, Interaction, and Epistemology: Mixtecs, Zapotecs, and Olmecs in Early Formative Mesoamerica. Ancient Mesoamerica 21: 135–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenschutz, Michael P., Alyssa A. Forcehimes, Jessica A. Pommy, Claire E. Wilcox, Paolo C. R. Barbosa, and Rick J. Strassman. 2015. Psilocybin-Assisted Treatment for Alcohol Dependence: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Journal of Psychopharmacology 29: 289–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, Cecilia. 2019. The Chicana M(other)Work Anthology: Porque Sin Madres No Hay Revolución. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Nolan L., Jeffrey F. Milem, Ozan Jaquette, and Ronald W. Marx. 2014. Missing the (Student Achievement) Forest for All the (Political) Trees: Empiricism and the Mexican American Studies Controversy in Tucson. American Educational Research Journal 51: 1084–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, Robin L., David Erritzoe, Tim Williams, James M. Stone, Laurence J. Reed, Alessandro Colasanti, Robin J. Tyacke, Robert Leech, Andrea L. Malizia, Kevin Murphy, and et al. 2012. Neural Correlates of the Psychedelic State as Determined by fMRI Studies with Psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109: 2138–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, Michael D., and Richard A. Diehl. 1980. In the Land of the Olmec. 2 vols. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cotera, Maria E., and Maria J. Saldaña-Portillo. 2015. Indigenous but Not Indian? Chicana/os and the Politics of Indigeneity. In The World of Indigenous North America. Edited by Robert Warrior. New York: Routledge, pp. 549–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cuauhtin, R. Tolteka. 2016. Healing Identity: The Organic Rx, Resistance, and Regeneration in the Classroom. In “White” Washing American Education: The New Culture Wars in Ethnic Studies. Edited by Denise M. Sandoval, Anthony J. Ratcliff, Tracy Lachica Buenavista and James R. Marin. Santa Barbara: Praeger, vol. 1, pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cyphers, Ann. 1996. Reconstructing Olmec Life at San Lorenzo. In Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Edited by Elizabeth P. Benson, Beatriz De La Fuente and Marcia Castro-Leal Espino. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, Yahaira, and Pamela Fenning. 2017. Toward Understanding Mental Health Concerns for the Latinx Immigrant Student: A Review of the Literature. Urban Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, Philip, Robert F. Heizer, and Robert J. Squier. 1959. Excavations at La Venta Tabasco, 1955. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 170. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Emboden, William. 1982. The Mushroom and the Water Lily: Literary and Pictorial Evidence for Nymphaea as a Ritual Psychotogen in Mesoamerica. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 5: 139–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Antonio. 2017. How the US Hispanic Population Is Changing. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/18/how-the-u-s-hispanic-population-is-changing/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Florescano, Enrique. 1999. The Myth of Quetzalcoatl. Translated by Lysa Hochroth. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, Jack D. 1973. Aztecas Del Norte: The Chicanos of Aztlán. Greenwich: Fawcett. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Santiago Andrés. 2011. Early Representations of Mesoamerica’s Feathered Serpent: Power, Identity, and the Spread of a Cult. Master’s dissertation, ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Santiago Andrés. 2012. Formative Representations of Mesoamerica’s Feathered Serpent and the Spread of a Regional Cult in Early Formative Mesoamerica (1500–900 BC). Paper presented at the Spring 2012 CSULA Mesoamerican Society Meeting, California State University, Los Angeles, CA, USA, April 29. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Santiago Andrés. 2014. Modeling household building sustainability (HBS) with wood, stone and paint: Achieving spatial wellness in a West Walnut household of the San Gabriel Valley, USA. International Journal of Development and Sustainability 3: 865–894. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Santiago Andrés. 2019. Contesting Trauma and Violence Through Indigeneity and a Decolonizing Pedagogy at Rio Hondo Community College. Journal of Latinos and Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, Santiago Andrés, Maritza Arciga, Eva Sanchez, and Robert Arredondo. 2018. A Medical Archaeopedagogy of the Human Body as a Trauma-Informed Teaching Strategy for Indigenous Mexican-American Students. AMAE Journal 12: 128–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, Susan D. 2008. “Pájaro-Serpiente” y la Gubernatura en Mesoamérica. In Ideología Política y Sociedad en el Periodo Formativo, Ensayos en Homenaje al Doctor David C. Grove. Edited by Ann Cyphers and Kenneth G. Hirth. México City: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, Patrisia. 2012. Red Medicine: Traditional Indigenous Rites of Birthing and Healing, 1st ed. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, Sandra M. 2015. Abuelita Epistemologies: Counteracting Subtractive Schools in American Education. Journal of Latinos and Education 14: 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, Jill. 1995. The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. Princeton: Art Museum, Princeton University Press in association with Harry N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, Gaston. 2012. New Taxonomical and Ethnomycological Observations on Psilocybe S.S. (Fungi, Basidiomycota, Agaricomycetidae, Agaricales, Strophariaceae) from Mexico, Africa, and Spain. Acta Botánica Mexicana 100: 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guzmán, Gastón. 2016. Las Relaciones de los Hongos Sagrados con el Hombre a Través del Tiempo. Anales de Antropología 50: 134–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, Gaston, John W. Allen, and Jochen Gartz. 1998. A Worldwide Geographical Distribution of the Neurotropic Fungi: An Analysis and Discussion. Annali dei Musei Civici di Rovereto 14: 189–280. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Matthew W., Albert Garcia-Romeu, Mary P. Cosimano, and Roland R. Griffiths. 2014. Pilot Study of the 5-HT2AR Agonist Psilocybin in the Treatment of Tobacco Addiction. Journal of Psychopharmacology 28: 983–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Brian M., Angélica González-Oliver, Ripan S. Malhi, Cara Monroe, Kari Britt Schroeder, John McDonough, Gillian Rhett, Andres Resendéz, Rosenda I. Peñaloza-Espinosa, Leonor Buentello-Malo, and et al. 2010. Evaluating the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis with Genetic Variation Exhibited by Populations in the Southwest and Mesoamerica. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107: 6759–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, Laurence, Cori Simpson, and Margaret Cargo. 2003. Healing Traditions: Culture, Community and Mental Health Promotion with Canadian Aboriginal Peoples. Australasian Psychiatry 11: S15–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kometer, Michael, Thomas Pokorny, Erich Seifritz, and Franz X. Volleinweider. 2015. Psilocybin-Induced Spiritual Experiences and Insightfulness Are Associated with Synchronization of Neuronal Oscillations. Psychopharmacology 232: 3663–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, Teri S., and Pål-Ørjan Johansen. 2013. Psychedelics and Mental Health: A Population Study. PLoS ONE 8: e63972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Satish, Claire Bellis, Mark Zlojutro, Phillip E. Melton, John Blangero, and Joanne E. Curran. 2011. Large Scale Mitochondrial Sequencing in Mexican Americans Suggests a Reappraisal of Native American Origins. BMC Evolutionary Biology 11: 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesure, Richard G. 2004. Shared Art Styles and Long-Distance Contact in Early Mesoamerica. In Mesoamerican Archaeology. Edited by Julia A. Hendon and Rosemary A. Joyce. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lisotto, Maria J. 2017. Mental Health Disparities: Hispanics and Latinos. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (Division of Diversity and Health Equity). [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Steven R., Concepcion Barrio, Alex Kopelowicz, and William A. Vega. 2012. From Documenting to Eliminating Disparities in Mental Health Care for Latinos. American Psychologist 67: 511–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, Jennie, and Martha Galeana. 2016. Remembering Coyolxauhqui as a Birthing Text. Regeneración Tlacuilolli: UCLA Raza Studies Journal 2: 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez, Claudia Itzel, and Santiago Andrés Garcia. Forthcoming. Mom’s Healing Altar and Dad’s Obsidian Blade: Building the Indigenous Xicana/o/x Family Healthcare Kit. In Search of Our Brown Selves: A Chicano Studies College Reader, 2nd ed. Edited by Silvia E. Toscano and Enrique C. Orozco. Dubuque: Kendall Hunt Publishing.

- Martinez-Cruz, Paloma. 2011. Women and Knowledge in Mesoamerica: From East LA to Anahuac. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, Lara, and Martha R. Gonzales. 2019. Voices from the Ancestors: Xicanx and Latinx Spiritual Expressions and Healing Practices. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milbrath, Susan. 2017. Maya Astronomical Observations and the Agricultural Cycle in the Postclassic Madrid Codex. Ancient Mesoamerica 28: 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Sandoval, Cueponcaxochitl D., Lagunas Rosalva Mojica, Montelongo Lydia T., and Díaz Marisol Juárez. 2016. Ancestral Knowledge Systems: A Conceptual Framework for Decolonizing Research in Social Science. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 12: 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, David E. 2004. Hallucinogens. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 101: 131–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortíz, C. Ponciano, and Maria D. C. Rodríguez. 2000. The Sacred Hill of El Manatí: A Preliminary Discussion of the Site’s Ritual Paraphernalia. In Olmec Art and Archaeology in Mesoamerica. Edited by John E. Clark and Mary E. Pye. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, Django, and Alim H. Samy. 2014. What are we seeking to sustain through culturally sustaining pedagogy? A loving critique forward. Harvard Educational Review 84: 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorny, Thomas, Katrin H. Preller, Michael Kometer, Isabel Dziobek, and Franz X. Vollenweider. 2017. Effect of Psilocybin on Empathy and Moral Decision-Making. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 20: 747–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, Laura. 2015. Geographies of Race and Ethnicity III: Settler Colonialism and Nonnative People of Color. Progress in Human Geography 42: 309–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijada Cerecer, Patricia D. 2013. The Policing of Native Bodies and Minds: Perspectives on Schooling from American Indian Youth. American Journal of Education 119: 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, F. Kent, III. 1995. Art, Ritual, and Rulership in the Olmec World. In The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. Edited by Jill Guthrie. Princeton: The Art Museum, Princeton University, pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, William M., Tomás G. Negrón, and George J. Bey, III. 1998. The Return of Quetzalcoatl: Evidence for the Spread of a World Religion During the Epiclassic Period. Ancient Mesoamerica 9: 183–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Roberto C. 2014. Our Sacred Maíz Is Our Mother: Indigeneity and Belonging in the Americas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Roberto C. 2017. Ixiim: A Maiz-Based Philosophy. Journal of Latinos and Education 18: 126–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Roberto C. 2019. The Ants and Quetzalcoatl [Video File]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZCBG67yZpCs (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Roseman, Leor, Lysia Demetriou, Matthew B. Wall, David J. Nutt, and Robin L. Carhart-Harris. 2018. Increased Amygdala Responses to Emotional Faces after Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Neuropharmacology 142: 263–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahagún, Fray B. 1950. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Translated by Arthur J.O. Anderson, and Charles E. Dibble. Santa Fe: School of American Research and the University of Utah. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Gabriela K. 2020. Reaffirming Indigenous Identity: Understanding Experiences of Stigmatization and Marginalization among Mexican Indigenous College Students. Journal of Latinos and Education 19: 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, Stacy B. 2015. Huichol Women, Weavers, and Shamans. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Leanne B. 2014. Land as Pedagogy: Nishnaabeg Intelligence and Rebellious Transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeter, Christine E. 2011. The Academic and Social Value of Ethnic Studies: A Research Review. Washington, DC: National Educational Association Research Department. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Michael E. 1984. The Aztlan Migrations of the Nahuatl Chronicles: Myth or History? Ethnohistory 31: 153–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, Saburo. 2005. Human Sacrifice, Militarism, and Rulership: Materialization of State Ideology at the Feathered Serpent Pyramid, Teotihuacan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, Thomas C., Alexander B. Belser, Gabrielle Agin-Liebes, Neşe Devenot, Sara Terrana, Harris L. Friedman, Jeffrey Guss, Anthony P. Bossis, and Stephen Ross. 2017. Cancer at the Dinner Table: Experiences of Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Distress. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 57: 488–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taube, Karl A. 1995. The Rainmakers: The Olmec and Their Contribution to Mesoamerica Belief and Ritual. In The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. Edited by Jill Guthrie. Princeton: The Art Museum, Princeton University, pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]