Abstract

Every European region and country has some specific heraldry. In this paper, we will consider heraldry in the People’s/Socialist Republic of Macedonia, understood by the multitude of coats of arms, and armorial knowledge and art. Due to historical, as well as geographical factors, there is only a small number of coats of arms and a developing knowledge of art, which make this paper’s aim feasible. This paper covers the earliest preserved heraldic motifs and coats of arms found in Macedonia, as well as the attributed arms in European culture and armorials of Macedonia, the кing of Macedonia, and Alexander the Great of Macedonia. It also covers the land arms of Macedonia from the so-called Illyrian Heraldry, as well as the state and municipal heraldry of P/SR Macedonia. The paper covers the development of heraldry as both a discipline and science, and the development of heraldic thought in SR Macedonia until its independence in 1991.

1. Introduction

Macedonia, as a region, is situated on the south of Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe. The traditional boundaries of the geographical region of Macedonia are the lower Néstos (Mesta in Bulgaria) River and the Rhodope Mountains to the east; the Skopska Crna Gora and Shar mountains, bordering Southern Serbia, in the north; the Korab range and Ohrid and Prespa Lakes in the west; the Pindus Mountains and the Aliákmon River in the south. Including the Chalcidice Peninsula, this stretch of land covers about 25,900 square miles (67,100 square km) (Danford n.d.).

The Latin kingdom in the first half of the 13th century included the southern part of Macedonia with Thessaloniki, which was under heavy influence from western culture, and might have also had an heraldic influence; however, this is a topic for another paper.

At the time of the birth of heraldry, Macedonia was part of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, and at the end of the 13th century, was incorporated into the Serbian Kingdom. Here, we find the first reflections of European heraldic practice, emerging among several nobleman that ruled the parts of this region. As Acovic notes, this was more “heraldry of emblems, not of rules.” (Aцoвић 2008, p. 71). However, by the end of the 14th century, Macedonia came under the control of the Ottoman Empire and, due to the Islamic proscription of the use of images, any real possibility of bearing arms was soon eliminated.

The heraldry connected to Macedonia was then further developed in European culture, more as an idea than a real territory or administration with real heraldry. This was first done through the attributed arms of Alexander the Great of Macedonia, seen as a symbol rather than a historical figure. Alexander III, the son of Philip II, lived in the 4th century BC, a millennium and a half before heraldry was even conceived in the 11th century. As with other attributed arms, he never bore any of the arms attributed to him some 1500 years later. Later, this was achieved through the fantastic land arms in the Illyrian Armorials, which showed Macedonia as the part of a Slavic kingdom. In practice, heraldry only returned to the region in the 19th century.

The Macedonian national movement started in the second part of the 19th century, with several uprisings against Ottoman rule, with no overall success. The Ottoman period ended with the Balkan wars (1912–1913) and the partition of the region of Macedonia between Greece (Aegean Macedonia), Serbia (Vardar Macedonia), and Bulgaria (Pirin Macedonia), with a small part being given to Albania. Macedonians, longing for freedom, considered the fight for liberty as an occupation. The “Vardar Macedonia” as “Newly liberated territory“ became Southern Serbia and, after the First World War, it became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later renamed Yugoslavia in 1929), known as Vardar Banovina.

During WWII, the Anti-Fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) on its second session, held in Jajce on 29 November 1943, made the creation of the Macedonian state within Yugoslavia possible. The Democratic Federal Macedonia was formed during the first session of the Anti-Fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) on 2 August 1944 (this later became the People’s Republic of Macedonia, a federal unit of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia). In 1963, the name was changed to the Socialist Republic of Macedonia and, during the struggle for independence in 1991, “Socialist” was dropped from its name. The Republic of Macedonia became independent with the referendum of 8. September 1991. In February 2019, with the Prespa agreement, in a highly controversial process, the name was changed to the Republic of North Macedonia. This paper discusses the processes prior to the name change, and so the historic names are herein used.

Heraldry is a phenomenon in Western European feudal society, based on its characteristics, where communication was practically reduced to only verbal and symbolic means due to the level and nature of literacy. Heraldry is an interdisciplinary phenomenon that encompasses elements of history, art, law, and philosophy; therefore, it is difficult to give it a single comprehensive definition (Joнoвcки 2015, p. 32).

Ottfried Neubecker provides the following definition: “Everything connected with arms is called ‘heraldic’, and the whole complex of armorial knowledge and art is called heraldry” (Neubecker 1997, p. 10). We agree with this continental understanding of heraldry, as Stoyan Antonov gives the heraldry at least five meanings: (1) the multitude of coats of arms, which are governed by certain criteria; (2) the system of rules for creation and usage of the coats of arms; (3) the science of researching that system and its history; (4) the system of symbols of identification of individuals and communities; (5) the combination of a symbol with an image associated with heraldry with both science and art (Antonov 2007).

V.I. Adamushko and M.M. Elinskaya emphasize the semiotic side of heraldry, defining it as “the science of symbols and allegories, and its practical part is the art of devising coats of arms—a field with various signs and figures that need to be deciphered”. This definition enters into the symbolic understanding of coats of arms, which can be seen as images that have multiple meanings, not just for identification, but to send a message that the observer should perceive (Aдaмyшкo 2012, p. 7).

In the United Kingdom, the oldest functions of the heralds are still preserved—organizing ceremonies, recording pedigrees, and, thus, defining the order of succession to the throne, the inheritance of noble titles and the correct seating plans for ceremonies. Fox-Davis distinguishes between armory: “the science of the rules and laws governing the use, display, meaning and knowledge of the pictured signs and emblems appertaining to shield, helmet or banner” and heraldry as a wider term that includes armory and more “all that is under the jurisdiction of the herald … regulation of ceremonies and matters of pedigree” (Fox-Davis 1978, p. 1). This distinction is made by Stephen Friar (Friar 1987, p. 183), but in the rest of the world, heraldry means armory.

In this paper we will consider the heraldry in the P/SR Macedonia, as understood by Neubecker; that is, the multitude of coat of arms, and armorial knowledge and associated art. (Neubecker 1997, p. 10). Owing to historic as well as geographical reasons, the number of coats of arms is limited and the scope of allied fields narrow, which makes this paper’s aim practicable. It covers the earliest preserved heraldic motifs and coat of arms found in Macedonia, as well as the attributed arms in European culture and armorials to Macedonia, King of Macedonia, and Alexander the Great of Macedonia. It also covers the State and municipal heraldry of the P/SR Macedonia, as well as the development of heraldry as a discipline and a science, and also the development of heraldic thought in SR Macedonia.

2. Beginnings

The oldest proto-heraldic motifs in P/S/R Macedonia are found in the monastery church of St Pantelejmon in Nerezi, in the vicinity of Skopje, built in 1164 by the Byzantine nobleman Alexis Comnène. There is a presentation of six Holy Warriors depicted with shields. On both sides of the entrance to the main sanctuary, there are frescoes of three Holy Warriors each. The text with their names on the frescos did not survive, but the identities of the Warriors could be established, by analogies (Бapџиeвa-Tpajкoвcкa 2004).

On the left side, there are representations of St. Mercurius where only the reverse of the shield is visible; St. Theodor Stratilat with shield per cross Vert and Gules, fields diapered with floral patterns; and St. Theodor Tyron: the color of the shield did not survive, but on the shield there is a golden demi-centaur and several small eight-pointed suns, which either indicate that the field is semée of suns Or, or more probably, diapering.

On the right side (Figure 1a) are St. George: only the reverse of the shield is visible; St. Demetrius’ color of his shield did not survive, but is probably Azure, and the charge is a lion Or. The lion’s posture could not be determined since no parts of the body survived. On the field there are several small eight-pointed suns, which either indicate that the field is semée of suns Or or, more probably, diapering. Third is St Nestorius: shield is per fess (or per cross) Gules and Vert (Jonovski 2009a; 2009b, p. 24).

Figure 1.

(a) Right wall of the entrance of the main sanctuary of monastery church of St Pantelejmon in Nerezi, Skopje; (b) Angelino Dulcert map of 1339, and reconstruction by Stamatovski.

The next oldest heraldic representation connected with Macedonia surviving to the present time, or discovered so far, is the banner of Skopje, on the map of Angelino Dulcert from 1339 (Dulcert 1339), with the blazon: Or, a double-headed eagle Gules. Above it the name of the city “Scopi” is written “Servia”. It should be noted that this presentation is different from the traditional arms of Serbia with the blazon, Gules, double-headed eagle Argent (Figure 1b). The double-headed eagle is a universal symbol across many cultures. The earliest image appears in Sumeria around 2500 BC. It is also found in Persia and the Hittites used it in the 15–12 centuries BC. It is most commonly known as a symbol connected with the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire representing the symphony between Church and State, or as a symbol of the Eastern and Western parts of the Roman Empire. It entered European heraldry in the coat of arms of Count Ludwig von Sarwarden in 1185. Later it was used as a coat of arms of the Holy Roman Empire. Today it is on the coat of arms of Russia, Serbia, Albania, and Montenegro (for more information see (Phillips 2014)).

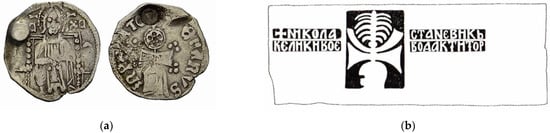

The existence of personal heraldry of the 14th and 15th centuries in the region is proven by material artefacts. The oldest heraldic representation on the arms on coins is of King Stefan Dushan Nemanjic (Skopje was his capital where he was crowned in 1346), and a helmet with a crest of a feather is presented. King Stefan Urosh IV Dushan (c.1308–1355) was 11th ruler of the Nemanjic dynasty. His son Stefan Urosh V the Weak was the last ruler of the Nemanjic dynasty. He died in 1371, soon after much of the Serbian nobility was killed in Battle of Maritsa by the Ottomans. The coins were minted somewhere between 1335 and 1345 (Figure 2a). The arms of the Nemanjic dynasty are found in the Illyrian armorials (end of 16th century) with blazon Gules, a double headed-eagle each head crowned Argent. This differs from the heraldry used on his coins.

Figure 2.

(a) Coin of King Stefan Dushan (minted 1335–1345); (b) Tombstone of Nikola Stanjevic (1346–1371).

On the tombstone of the great duke and general of King Dushan, Nikola Stanjevic (1346–1371), the founder of the monastery of St. Stephen in Konche near Radovish, there is a helmet with a pillow and feather (Figure 2b).

After the disintegration of Dusan’s Empire, the territories of Skopje, Prizren, Pristina, the Albanian mountains, Debar, Ohrid, Prespa and Kostur were under the rule of Volkashin, who in 1365 was promoted to king. His son King Marko was his co-ruler until the death of Volkashin in 1371 at the Battle of Maritsa. They came from the Mrnjavcevic family, whose coat of arms is present in the Illyrian armorials (Figure 3a). The crest is a girl holding a flag per Pale Argent and Gules with an eagle countercharged. On coins which he minted and on a seal preserved on a charter from 1370 in Dubrovnik, there is a helmet with a crest with the head of a princess with a crown. Two branches emerge from the helmet, which may be part of the mantling (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Mrnjavcevic coat of arms (London Armorial); (b) Volkashin seal from charter of 1370 (Dubrovnik).

Another ruler after the disintegration of Dushan’s Empire, situated north of Volkashin, was Vuk Brankovic, who in 1377 captured Skopje from King Marko. Brankovic’s family coat of arms is found in the Illyrian armorials with a lion between two horns (Figure 4a). The same motif is found on a seal of Vuk Brankovic, depicting an entire coat of arms, with a shield, helmet and crest (Figure 4b). The shield depicts a lion between two horns, a motif repeated on the crest (Ивaнишeвић 2004, p. 227).

Figure 4.

(a) Brankovici’s family coat of arms (London Armorial); (b) a seal of Vuk Brankovic.

At the end of the 14th century even lesser nobles also had coats of arms. This is confirmed by the rings with heraldic motifs, usually with double-headed eagles, but also with a dragon. A ring from the necropolis in Vodocha shows a whole coat of arms with a shield, helmet and crest. The shield is checky and the crest is probably a wolf. Around the ring there is a text “Respect the slave of God Hlpen” which may be related to Radoslav Hlapen, ruler of Ber and Voden, the father of Jelena, the wife of King Marko (Maнeвa 2007, cat no 40).

Soon under the Ottoman Empire and its Islamic conception of art, heraldry in the area ceased to exist. Some of the families migrated abroad and acquired coats of arms, as part of the local society. Some of them retained memories of the “old land”. One such family was the Maczedoniai, mentioned in 1439 in Vojvodina. Its most prominent member was Ladislav Maczedoniai, who in 1533 was appointed bishop of Veliki Varazhdin. The familly used a seal from 1525 and is registered in the coat of arms of Siebmacher from 1605. Only the small coat of arms with an eagle, without colors or heraldic crest is shown. Jovan Monastirli, probably from Bitola, received a coat of arms on 11 April 1691. The coat of arms has a lion statant with a sword and a dragon on the crest.

Others wanted to build on the glorious history of the ancient Macedonian kings, such as the Macedonio family of Naples. According to family legend, they originated from Thessaloniki, descending from the half-sister of Alexander the Great, the wife of Cassander. At that time it was not uncommon for family legends to be filled with mythological connections to old noble and royal families; something we will see in more detail with the history of the Ohmucevic family.

3. Indirect Heraldry

With the incorporation of Macedonia, at the end of the 13th century into the Serbian Kingdom, we have the first reflections of European heraldic practices emerging among several noblemen that ruled parts of this region. This will be elaborated in the next section about real heraldry. By the end of the 14th century, Macedonia was already under the control of the Ottoman Empire, and, as mentioned above, heraldic practice died out. Further development of heraldry connected to Macedonia went into a different realm, that of strong symbolic meaning, with only an imaginary connection to the reality. To be more precise, into the world of heraldry of fantasy and attributed arms in European medieval culture and literature.

3.1. Attributed Arms from European Sources

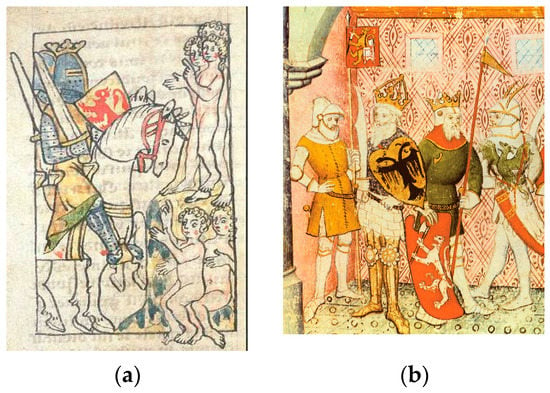

The idea or image of Macedonia came into medieval European culture and heraldry, represented through the attributed arms of: Macedonia; a king of Macedonia, attributed to a king of Macedonia as an idea, not to a real person from history; the mythical prince or king Makedon of Eamhtia, and Alexander the Great. The image of Alexander the Great of Macedonia was very popular in medieval Europe; it was the image of a great conqueror and a symbol of virtue and chivalry. These qualities can be found in several works on his life and accomplishments—the Alexander Romances. This led to arms being attributed (he did not actually bear them, but they are fanciful products of the developed heraldic period) to Alexander, illuminating the Alexander Romances, and found in general stories and histories and armorials. These coats of arms and armorial flags were not permanent, but various interpretations appeared depending on the region. From the 13th century, 36 original works in French and English are known, and all of them show the arms with a lion. In German works other symbols also appear in the attributed coat of arms of Alexander (Nacevski 2016, p. 12).

The first arms attributed to Alexander the Great appeared in the early 13th century (perhaps 1210) in the work of Roger IV of Lille, Histoire ancienne jusqu’à César, and in its illustrated version, the manuscript of Dijon (Cesar 1260). In it, Alexander’s coat of arms is Gules a lion Argent; in the general history of Lambertus de Sancto Audomaro, Liber Floridus (de Audomaro 1250–1270, p. 71v), Argent a lion Gules. The same blazon is found several times in the illustrated manuscript of the 14th-century novel by Thomas de Kent Le roman de toute chevalerie by Jehan de Grise (Figure 5a) (de Kent 1338–1410). Selovski counts 29 illustrations with the blazon Or a lion Gules, and in three Gules a lion Or (Ceлoвcки 2016). These crossed over into the coats of arms of Macedonia, as discussed later.

Figure 5.

(a) Alexander from Le roman de toute chevalerie; (b) Alexander as a part of the three good pagans from Nine Worthies, Le Chevalier Errant.

Most important are “the Nine Worthies” from Jacques de Longuyon’s epic poem Les Voeux du Paon, (de Longuyon 1350, p. 69v) performed before the Bishop of Liege in 1312. The Nine Worthies were a triad of triads: the “Good Pagans”: Hector of Troy, Alexander the Great, and Julius Caesar; the “Good Jews”: Joshua, King David, and Judas Maccabeus, and the “Good Christians”: King Arthur, Charlemagne, and Godfrey of Bouillon, King of Jerusalem. Armorials often included the arms of the Nine Worthies. For the first time they appeared in the Armorial von den Ersten, called the Codex Seffken in 1379. In an 1893 edition by Adolf Matthias Hildebrandt and Gustav Seyler, Alexander’s coat of arms is blazoned Gules a lion Or, bordure engrailed (Hildebrandt and Seyler 1893). Gules a lion Or also appears in the 14th century work Mare historiarum ab orbe condito ad annum Christi 1250 by Joanne de Columna (de Columna n.d.).

Coats of arms and armorial flags of the Nine Worthies can be found in stone, frescoes, tapestries, etc.; often the coats of arms show some inconsistency, sometimes transposed with each other. The three “Good Pagans”: Hector, Julius Caesar, and Alexander are shown on a wool tapestry from southern Holland from about 1380. The blazon for Alexander’s arms is a Gules a lion Or holding a long battle axe [(Nine Worthies Tapestry n.d.)]. A similar blazon appears in Le Chevalier Errant by Thomas III of Saluzzo, 1394 (Figure 5b) (Saluzzo 1394, p. 125r). In other arms, the axe is replaced by a halberd and sometimes the colors are inverted.

Jehan Wauquelin’s (†1457) Les Faicts et les conquestes d’Alexandre le Grand, illustrations of Willem Vereland (†1481) shows Alexander’s coat of arms appearing as Or a lion Gules (Figure 6a). This same blazon is repeated in the Blason des Armoiries by Jerome de Bara (1540–1600) (Figure 6b), published in Geneva in 1572, and in that of Jean Robin in 1639. Coats of arms with reversed colors appear in three more instances: the Spanish armorial of Garcia Alonso de Torres from 1496, the general armorial of Lauren of the 15th century, and the 1543 Armorial of Noel Bocode (Ceлoвcки 2016).

Figure 6.

(a) Alexander, Les Faicts et les conquestes d’Alexandre le Grand; (b) Arms of the nine worthies, Blason des Armoiries.

The heraldic flag with a lion is found on frescoes at Monti Castle in Italy, dating from 1430 (Figure 7a). Alexander is holding a heraldic flag of Gules a lion seated on a throne holding an axe all Or. Similar frescoes from the same period are found in the Château de Valère, in Sion, Switzerland, but Alexander is represented there by Or a lion Gules (Norris 1997, p. 199).

Figure 7.

(a) Monti Castle, Italy; (b) Arms of King of Macedonia, High Almain Roll.

The majority of these depict lions in one of the three heraldic poses: a lion rampant (including holding an axe) is the most frequent; then a lion seated on a throne holding an axe; or, most rarely, two lions combatant. The color of the shield is usually red or gold, sometimes blue or silver. The lion, however, usually appears in gold, then red, and least often silver, blue, or black. Nacevski considered 35 works with heraldic illustrations for Alexander the Great; 21 are coats of arms. (Nacevski 2016). The most common depiction is a lion rampant (with or without an axe), and in a combination of red and gold, with slightly more occurrences of Gules a lion Or (Јoнoвски 2019).

The heraldic representations of the King of Macedonia in European armorials are idealistic representations to glorify the “glorious” past. The first mention of the arms of a king of Macedonia is found in the High Almain Roll c. 1447–1455 (Figure 7b) (High Almain Roll 1447, fol 9) where the blazon is Azure three crowns Gold with caps Gules; Crest: out of a crown Gold a conical cap Argent tipped with a ball; mantling: Azure doubled Argent. This blazon is not found again.

Chronologically, the next representation of the king of Macedonia is in Randle Holme, of 1448, with blazon Or, four bars embattled on both sides, and voided Gules (Holme 1448). The same blazon with some variation appears in 1593 in Robert Cook’s, Two Tudor books of arms (Cook 1593, p. 110). Similar blazon Gules three bars embattled on both sides Argent, fimbriated Or (Figure 8), appears in Sammelband mehrerer Wappenbücher of 1530 (Sammelband 1530, p. 56).

Figure 8.

(a) King of Macedonia in Sammelband mehrerer Wappenbücher 1530; (b) same.

The most frequent blazon is with three crowns in a two-colour combination. Argent three bels Gules is found in 1495 in Jörg Rugen: Wappenbuch Innsbruck (Rugen 1495). The same blazon is found in 1501–1550 in Wappenbuch, (Wappenbuch 1501, 55r), and in 1576 in Silbereisen: Chronicon Helvetiae (Silbereisen 1567, p. 570). The blazon Gules three bels Argent, (Rugen 1495) and in 1638 in Silvestro Pietrasanta, Tesserae gentilitiae (Pietrasanta 1638, p. 13).

There are other blazons for the attributed arms of the king of Macedonia. In the Roll of Arms of the Bavarian Library of 1530, two other arms are represented with the blazons Or, three crossbows Or in Pale (Figure 8b) (Sammelband 1530, p. 66).

In the 16th c. Joachim Windhag’s Kolorierte Wappenbücher the blazon of the arms of Macedonia is Vert a goat Argent (Figure 9a) (Windhag 16hc, p. 2).

Figure 9.

(a) Arms of Macedonia, Joachim Windhag (b) Arms of Macedonia, Hieronymus Henninges.

In 1598 in Hieronymus Henninges, Theatrum genealogicum ostentans omnes omnium aetatum familias heroum et heroinarum, the blazon of arms of Macedonia is a club between two horns; the colours are not indicated (Figure 9b) (Henninges 1598).

In 1658 in Phillipe- Nicolas d’Aumale’s CHAROLAIS, the blazon of the arms of Macedonia is Gules a lion Or (d’Aumale 1658, 75r).

Apart from the king of Macedonia, there are arms of Macedon, king of Emathia, a Region around Thessalonica and Berea, regarded by some as the old name for Macedonia. In 1586 John Fern gives the blazon of the Arms of: Sable, a wolf Argent (Fearn 1586, p. 155). In 1598 in Hieronymus Henninges, the blazon is a wolf passant; no colours are given (Henninges 1598).

3.2. Land Arms of Macedonia in Ilyrian Heraldry

The lion from the coat of arms of Alexander the Great of Macedon would later cross into the “land” coats of arms of Macedonia in armorials and Stemmatographias. The Gules a lion Or most commonly appears in handwritten armorials, while Or a lion Gules appears most often in printed editions.

A “land coat of arms” refers not to a specific administrative territorial unit with defined rulers and borders, but rather to broad geographical regions, or even an idea. This is not a straight heraldic idea, but resulted from a specific historical process, that later led to some of them becoming “real” coats of arms. The land coat of arms appears in the “Illyrian heraldry” and the Stemmatographias.

“Illyrian heraldry” refers to several transcriptions of a fictitious Armorial “Genealogies ... of the Illyrian Kingdom” from 1340, allegedly created during the reign of the Illyrian King Stefan (Dushan) Nemanjic. The author of the 14th-century work was the fictional priest Stanislav Rupchic, the herald of King Dushan. Actually, the oldest copies are from the end of the 16th century, mainly containing arms of about 130 families from the town of Slano and its surroundings in the tiny maritime Ragusa (Dubrovnik) Republic on the eastern Adriatic coast. Several of these families, Ohmuchevic, Korenic- Neoric, Jerenic and others, became prominent in the Spanish navy, achieving high status and wealth.

The movement of those families between heraldic jurisdictions (which regulated the possession of arms and their status in society) led to the creation of genealogies and armorials documenting existing and newly created arms. Dubrovnik, like Venice, did not grant or confirm coats of arms, as anyone could bear a family coat of arms, which did not prove noble status in society. In the 15th century, many prominent citizens, merchants, citizens, and priests in the rural areas surrounding the Dubrovnik Republic began to adopt coats of arms based on examples seen in Dubrovnik (Ćosić 2015, p. 20).

In order to prove their noble origins they created a series of documents including armorials. Those armorials included real and fictitious arms of the family members and ancestors and other unrelated families (Coлoвjeв 2000, p. 128). In order to prove the age and importance of the “original armorial” of Stanislav Rupcic of 1340, the Illyrian Armorials included nine Land arms and 13 arms of prominent ruling families of the 14th century (Illyrian Armorial 2005). The armorials were handwritten and hand-illustrated transcriptions. Through the many subsequent copies, additional arms were added, in order to give them legitimacy or simply to supplement a family genealogy or were only partially copied. There are 23 such transcripts known, later called the “Illyrian Armorials,” of which seven have been lost (Aцoвић 2008, pp. 219–20).

The Illyrian Armorials, in fact, constitute successive editions of an armorial of Slano families, created in the last decades of the 16th century. The arms used for the Balkan lands especially Macedonia, Serbia and Bulgaria, were long considered, the first representation of those arms, and therefore the Illyrian Armorials are very important to them.

The coat of arms of Macedonia, depicted as Gules a lion Or, is located in the first field of the dominion coat of arms of Stefan Dushan Nemanjic, which consisted of nine quarters with land arms. Following this, the coats of arms of these lands were also shown individually. Macedonia’s coat of arms has the same blazon as one of the most common of the coats of arms attributed to Alexander the Great. At the time of the Slano armorial creation, other armorials including the coat of arms of Alexander of Macedon were circulating in Europe. Thus, the coat of arms of Macedonia was most likely inspired by the coat of arms of Alexander, which appears as Gules a lion Or, or Or a lion Gules (Joнoвcки 2015, p. 171; Ćosić 2015, p. 129; Ceлoвcки 2016). This blazon, with some changes in the secondary attributes of the lion, remained the same in most of the later copies.

One of the oldest known versions of the Slano “Illyrian” Armorials is the London Armorial, dating from around 1590. The armorial’s structure shows the influence of Virgil Solis’ armorial from 1555, with the coat of arms of the cardinals replaced by images of saints, and the dominion coat of arms of the Holy Roman Empire replaced by the coat of arms of the mythical Illyrian empire. The arms on the dominion coat of arms appear instead of the kingdoms under the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor. Furthermore, the arms of 141 families replace the arms of the knights and other noblemen (Filipović 2009).

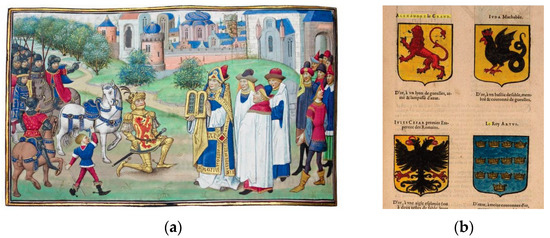

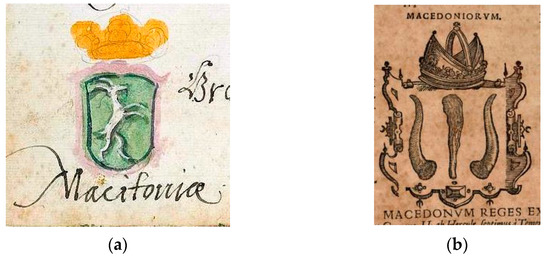

In the London Armorial the image for Macedonia shows, on a German-type shield, the arms Gules a lion Or the shield ensigned with a crown. The lion has a single tail. The shield is crowned with five-pointed ancient crown (Figure 10a).

Figure 10.

(a) Coat of arms of Macedonia (London Armorial); (b) Belgrade Armorial II, 1620.

Very similar to the London Armorial is the armorial of Korenic-Neoric, held by the University Library in Zagreb, and believed to date from 1595. The Macedonian coat of arms is shown three times: as the 1st (top dexter) field of the dominion coats of arms of King Stefan Nemanjic, those of King Urosh, and on a separate page. Only the lion in this armorial is armed Or. This armorial, unlike the London Armorial, also includes the arms of Spanish families into which the Korenic–Neoric daughters and other female descendants would marry after there were no male descendants (Ćosić 2015, pp. 351–61).

Many Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian, Albanian, and other families used versions of this armorial as proof of their noble descent when claiming nobility before the Austrian, Venetian, and Dubrovnik authorities (Glasnik 1938, p. 4).

In the Althan Armorial of 1614, held by the University Library in Bologna, the Macedonian land arms are shown: Gules a lion Or crowned queued forchée. For the first time, the lion has a queue forchée. The shield is of the style called “Gothic” in Macedonian heraldic dictionary. Above is the text: “Maкeдoнcкe зeмлe чимepи” (Makedonske zemle chimeri, the arms of the Macedonian land) (Maткoвcки 1970, p. 87). Very similar is the Belgrade Armorial II from 1620 (Figure 10b). The Macedonian land coat of arms contained in it is on a Renaissance shield. Similar is Marko Skorojevic’s Armorial of 1636–1638.

The Fojnica Armorial is kept in the Holy Spirit Franciscan monastery in the town of Fojnica in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Miletić 2005). Dating is difficult, but it was made sometime in the 17th century (Coлoвjeв 2000, p. 166). Here, the Macedonian coat of arms is with simplified drawing with a blazon: Gules a lion Or crowned, the shield crowned with a so-called “Eastern” (radiant) crown.

In the 1689 Olovo Armorial, from Bologna, the land arms are on a German shield with a five-pointed crown. There is only a line drawing (Maткoвcки 1970, p. 106). In the Berlin Armorial, dating from the end of the 17th century, the land arms are shown as Gules a lion Or crowned on a German shield. The lion’s tail finishes in a torch, unique to this armorial. Above the shield is a gold crown. In the 1740 Kevešić Codex the Macedonian coat of arms is on a French shield. Above the shield is a ducal crown, while below it is “Macedoniae”. Matkovski gives several more armorials containing the arms with the same blazon (Maткoвcки 1970, pp. 77–147).

The transcripts were individual copies, often landing far from the public eye in private collections, archives, and monasteries. Their impact was far smaller than heraldic works that have been printed or even reissued many times.

3.3. Land Arms of Macedonia in Stematografies

The first printed book in which the Macedonian coat of arms appears is the Benedictine Mavro Orbini’s The Kingdom of the Slavs, published in Pesaro in 1601. The illustrations are line drawings, without heraldic hatching, taken from the Slano Armorials. The Macedonian coat of arms appears as the fourth field of the marshalled arms of Stefan Nemanjic. If following all other colored versions of these arms, this should be Or a lion Gules. This is a concept similar to the European heraldic heritage for the arms attributed to Alexander the Great. Orbini does not change the color, but the position of Macedonian land arms replaces it with a Bulgarian one.

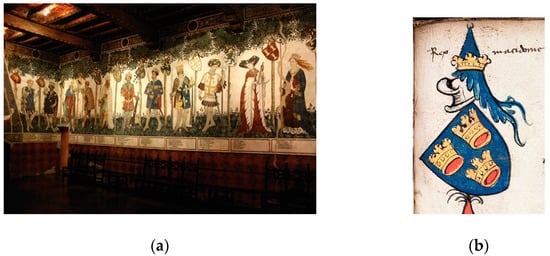

A century later, the Stemmatographia of Vitezovic appeared (Vitezović-Ritter 1701)—a collection of 54 arms of the lands (no family arms) perceived as Slavic at the earliest stage of Pan-Slavism and the Illyrian idea—to unite all the Southern Slavs in a kingdom called Illyria, as a hearkening back to glorious past of the Illyrian Kingdom that existed in pre-Roman time.

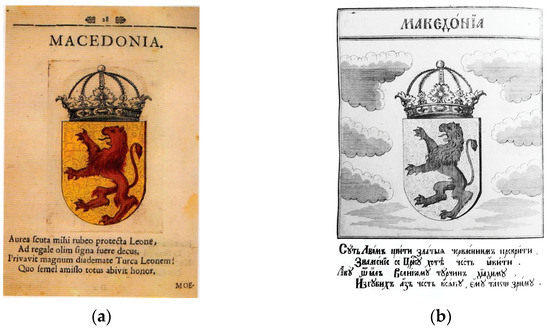

“Stemmatographia” means a collection of coats of arms. —it is a work dedicated to land arms themselves rather than a work where the coats of arms appear only as illustrations. The printed edition of the Stemmatographia of 1701 (Vitezović-Ritter 1701) is the first printed work to depict Macedonia’s coat of arms explicitly with a blazon, a Or a lion Gules, likely following Orbini.

Vitezovic probably based his work on the Münster Cosmography showing the coats of arms on Spanish shields, of the lands in alphabetical order. Four explanatory verses in Latin appear beneath each shield.

The Macedonian coat of arms is Or a lion Gules (Figure 11a). The lion is uncrowned and has a single tail. The shield is crowned with an arched ducal crown. Above the arms “Macedonia” is written, and below are the following Latin verses:

Figure 11.

(a) Macedonian coat of arms (Vitezovic Stemmatographia); (b) Zhefarovic Stemmatographia.

- My golden shield is protected by red lion/Signs of royal honor of the past

- The Turk has deprived the lion of its great crown/Once it fell, it lost its honor.

This alludes to the red lion used as a symbol by a great king in the past, most likely Alexander the Great, which points to the continuity of this symbol and its heraldic use.

Later, the prominent Macedonian heraldist, Aleksandar Matkovski gave an explanation that actually Vitezovic used Or a lion Gules for Macedonia’s coat of arms, by mistake. According to Matkovski, Vitezovic, when compiling his Stemmatographia, cut the coats of arms from another armorial without the inscriptions. When pasting them in, he mistakenly exchanged the images of the Macedonian and Bulgarian coats of arms. Thus, above the inscription “Macedonia” he put Or a lion Gules. For Matkovski, this “unintentional change of Vitezovic” was the source of all other instances wherever a red lion appears and should be considered an error (Maткoвcки 170, p. 112).

However, the second part of the Stemmatographia presents more information about each coat of arms. For the Macedonian coat of arms, it reads:

MACEDONIA is distinguished by red lion on gold; which many people think was Greece’s coat of arms. Before the time of Alexander the Great, the Epirotes had a red dog, and then they put the club of Heracles upright between bulls’ horns. The Nemanjic kings, who carefully marked their superiority over subjugated nobles and regions, used a red lion to mark Macedonia.

In addition, for the coat of arms of Bulgaria, it reads:

BULGARIA is marked with a gold crowned lion on red field. In a manuscript I found a red lion on gold, which is thought to be of Macedonia. Apostolic kings, however, made it a black lion on silver between a red mullet and crescent(others tie it to Wallachia).

The text makes clear that Vitezovic believed that Or a lion Gules was the coat of arms of Macedonia. He probably used sources in which Macedonia’s arms were a Or a lion Gules, which were abundant.

Slavic translation of Vitezovic’s Stemmatographia by Hristofor Zhefarovic (Born in Dojran, Macedonia) was published in 1741 in Vienna. Zhefarovic added 16 pages with saints and canonized rulers, at the beginning, together with the portrait of Patriarch Arsenie and his arms. Some of the texts were modified in translation. The images of arms are very similar to those of Vitezovic. Only two arms of Rasca and Hungary are different.

For the Macedonian coat of arms, the Zhefarovic Stemmatographia shows Or a lion Gules on a Spanish shield (Figure 11b). The lion has single tail and is not crowned. Above the shield is a royal five-pointed crown. Above the arms is “Maкeдoнїa.” The verses for the arms differ “The gold shield is covered by a red lion/As a sign of the church honor.”

Throughout history Macedonia’s coat of arms differed from Bulgaria’s, which, although also a lion, has most often been depicted in a different combination of colors. This is confirmed in the handwritten Illyrian armorials, where Bulgaria is Or a lion Gules crowned. However, this has had no influence on the Bulgarian national identity; according to Bulgarian heraldists the Or a lion Gules was never perceived as the national coat of arms in Bulgaria (Лaжнa 2014).

4. Real Heraldry

4.1. Influence of Zhefarovic

The imaginary heraldry of literature and works of art of European culture connected to Macedonia, especially the Illyrian heraldry and Zhefarovic’s work in particular, turned into real heraldry. The map by Johan Jakob and German Lidl (1737) shows, in the lower left corner, the coats of arms of the European countries; Macedonia is represented by Or a lion Gules.

The same blazon appears in a book by Jovan Rajić (1726–1801), a monk, historian, and writer. The third volume of his work History of the Various Slavic Peoples, and Especially the Bulgarians, Croats, and Serbs, depicts the Macedonian coat of arms in a composition surrounding Tsar Dushan. The colors are denoted by heraldic hatching (Maткoвcки 1970, p. 136).

The same blazon for the Macedonian coat of arms is also used around 1851 on the Heraldic Table of Milan Simić with the local coats of arms of the Southern Slavs, placed on a tympanum with 11 columns showing 61 coats of arms and those of Tsars Dushan and Urosh—Macedonia’s arms are Or a lion Gules on both. The description reads: “On the arms a lion rampant to the left in a gold field” (Maткoвcки 1970, p. 146).

The blazon Or a lion Gules is painted on the iconostasis of the Monastery of St. Ivan of Rila in Pirin a historic part of Macedonia (currently in Bulgaria). The monastery was built by Hrelja Ohmuchevic (the mythical ancestor of Don Pedro Ohmuchevic), who built the tower in 1335 and the church in 1343. The church that stands today was built in 1834–1837, and painted in 1844–1846 by the Razlovci and Samokov painting school. On the northern part of the iconostasis four coats of arms appear: Serbian, Bulgarian, Bosnian, and Macedonian. The Macedonian coat of arms is on the lower row, right on the portal (Figure 12a).

Figure 12.

(a) Monastery of St. Ivan of Rila; (b) Flag of the Razlovci Uprising of 1876.

The same heraldic motive appears on the Macedonian flag of the Razlovci Uprising of 1876, created under the guidance of a teacher from Razlovci, Dimitar Pop Georgiev-Berovski. On it a red lion appears, uncrowned and with one tail. That lion, together with the inscription “MAKEДOHIЯ” in an arc, is set on a gold rectangle shifted toward the hoist (Figure 12b). The lion’s appearance comes from Zhefarovic’s Stemmatographia (among Georgiev-Berovski’s personal effects were several attempts to draw the Stemmatographia lion). The flag was also used in the Macedonian (Kresna) Uprising of 1878 (Mиљкoвиќ 2003, p. 23).

4.2. Serbia and Kingdom of SHS/Yugolsavia

From 1912, part of Macedonia was integrated into the Kingdom of Serbia and from 1918 into the Kingdom of Serbs Croats and Slovene (latter called Yugoslavia), and their respective coat of arms was used. The coat of arms of Serbia combines two arms: Gules a double-headed eagle Argent, which is found as the coat of arms of the Serbian ruling Nemanjic dynasty in the Illyrian armorials, beginning in the late 16th century. In them, as well in the Stemmatographias, as a coat of arms for Serbia, there is a Gules cross between four furisons all Argent. The design of the four furisons (or steels—used to strike fire from flints) actually originates from the flag of the restored Byzantine Empire when the flintsteels actually represent the letter “B”, which is probably an acrostic from the motto of the Palaiologos in translation The emperor over the emperors reigns with the emperors (Βασιλεὺς Βασιλέων Βασιλεύων Βασιλευόντων). Later, these furisons are perceived as the Cyrillic letter “S” and the four letters are believed to denote the slogan: “Only a union saves the Serbs.”

With the establishment of the Principality of Serbia in 1815, the coat of arms of Serbia from Zhefarovic Stemmatographia was taken as a state coat of arms, with a wreath of olive and oak branches. The first Serbian constitution from 1835 gives the official blazon, which says that the coat of arms of Serbia is a cross on a red field, with a furison between the arms of the cross and is facing the cross. The whole shield is surrounded with a a green wreath, on the right of oak, and on the left olive leaves.

As a result of the Great Eastern Crisis, Serbia gained the status of an independent state at the Berlin Congress. The prince Milan Obrenovic, using an opportunity to increase his influence in the country and to consolidate his power, in 1882 proclaimed himself king of Serbia, and with that came a change of coat of arms. The new coat of arms was conceived by the Serbian historian and researcher of heraldry Stojan Novakovic. His idea was that the coat of arms of the renewed Kingdom of Serbia should be based on the coat of arms of Nemanjic and arms of the Principality of Serbia, and thus establish a symbolic line of continuity (Kpаљ 2006).

The coat of arms of the Kingdom of Serbia is a double-headed white eagle on a red shield with a royal crown. At the top of both heads of the two-headed white eagle sits a royal crown; and one lily flower under each claw. On its breast is the coat of arms of the Principality of Serbia: a white cross on a red shield with one fire between each branch of the cross. The design is by the Austrian herald Ernst Krahl.

With the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in December 1918, a new coat of arms was adopted. The basis for the Kingdom’s arms was the one Serbian kingdom, whose king Peter I Karadjordjevic became the head of a new state. The new arms was to replace the Serbian with Yugoslav crown, to remove the fleur-de-lys from the base and to marshal the shield on the eagles breast with the arms of the constituent peoples. The decision was made on 28 February 1919 by the ministerial Council, and work given to the architect Pero Popovic (Joвaнoвић 2010, p. 103).

The coat of arms of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes is a double-headed eagle with a coats of arms on its chest. The shield is partitioned per fess, dexter per pale: (1) Serbia- Gules cross between four furisons all Argent, (2) Croatia–Checky Gules and Argent; (3) Slovenia–Azure, a star Or and in base a crescent Argent.

Serbian and Croatian arms are historic ones while for Slovenia a coat of arms were designed specifically for this. Later Slovenians asked for three stars in their arms, to connect to the historical coat of arms of the Counts of Celje (a town in Slovenia). This was added in 1921.

4.3. Coat of Arms of Skopje

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia, heraldically speaking, was made up of two parts, territories that were once part of Austro-Hungary, with highly developed local heraldry, and parts below the river Danube with almost no personal nor municipal heraldry. The arms of the capital, Belgrade were adopted on 10th December 1931 (Дpaжић 2009).

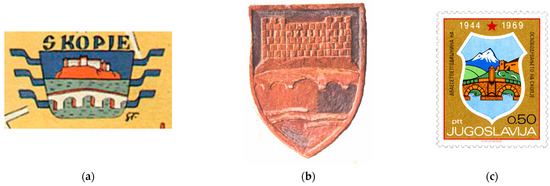

The first appearance of a coat of arms for the city of Skopje, then the capital of the Vardar Banovina region, is dated 21 February 1928, probably being a proposal. The coat of arms depicts a shield with a stone bridge, under which a river flows, as well as a landscape behind the bridge with mountains and rivers. Behind the mountain, and behind the clouds, the sun is rising. Behind the shield there is a large mantle with a crown. The coat of arms of the Kingdom of SHS is also depicted non-heraldically in the composition. The picture is in black and white and bears the author’s signature: probably “Fig. Dj. Sutulac” (Figure 13a).

Figure 13.

(a) “Proposal” for arms of the City of Skopje, 1928; (b) King Alexander Karadjordjevic collection (before 1934).

The coat of arms of the City of Skopje, together with the arms of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, appears engraved on a book cover in the private collection of King Alexander Karadjordjevic (Aцoвић 2008, p. 636). The shield is in the Spanish style and is crowned with “the crown of Tsar Dushan”. It is a landscape depicting a stone bridge fortress and a mountain (Figure 13b). These arms are used on the 1937 diploma of the Vardar Banovina fire brigade, where it shows the large arms of Skopje - the shield being borne on the breast of a double-headed eagle.

In the Second World War, during the Bulgarian administration on 12 July 1941, the following arms were adopted: “Kale fortress, a lion flying a red flag, with wheat stalks, and the Shar Mountains, with the bridge over the river Vardar; for a motto, ‘Blesti and Blagodenstvuva’ (Shines and Live Well)” (Пpoтoкoл 1941). The Ministry of the Interior and National Health granted permission on 6 October 1941 for the use of these arms, but the red flag which the lion was flying had to be replaced with the Bulgarian tricolor (Диpeкция 1941). The image was not preserved (Jonovski 2013).

The oldest representation of the arms of postwar Skopje, is from a 1950′s tourist map (Figure 14a). The Arms of Skopje have the following blazon: per fess Azure and Vert, upon a hill Gules a fortress Argent and in base a bridge Argent with five arches.

Figure 14.

(a) Coat of arms of the City of Skopje (1950s); (b) Coat of arms of the City of Skopje (1965); (c) Coat of arms of the City of Skopje (1969).

A similar representation is found in the book “Cities of Yugoslavia” (Figure 14b) (REVIEW 1965) also in “Heraldry 1” (Ćirić 1988), in the form of a line drawing.

The arms of Skopje, as registered and used in the former Yugoslavia in 6ter (WIPO section dealing with protection of regional marks) registration arms in 1967, are different and highly stylized. The shield is heater shaped with the top edge being embattled. The bridge, as well as Kale, are represented in a highly stylized manner, the latter obviously in the form of a (pre-earthquake) Skopje feudal castle. From 1969 (Figure 14c), till today, the arms of Skopje have the same composition of 1931 but on a different shield.

4.4. Coat of Arms of P/S/R Macedonia

The coat of arms of the People’s Republic of Macedonia was adopted as the first item on the agenda of the Second Extraordinary Session of the National Assembly, held in Skopje on 26 July 1946. The draft bill was presented by people’s delegate Dimche Belovski, and the debate was attended by people’s delegate Dr. Blagoj Arsov and the Minister of Education Nikola Minchev, after which the Law was passed unanimously (Hapoднoтo 1946).

The Law on the Coat of Arms of the People’s Republic of Macedonia, in Article 1, describes this coat of arms:

The coat of arms of the People’s Republic of Macedonia is a field surrounded by wheat stalks intertwined with poppy fruits and tobacco leaves, which at the bottom are connected with a ribbon embroidered with folk motifs. On the ribbon is written “N. R. Macedonia.” (N(arodna) R(epublika)–Peoples Republic). At the top is a five-pointed star. In the middle of the field is a mountain; a river flows at its foot. Behind the mountain the sun rises (Зaкoн 1946).

There was a purely landscape composition, with the sun rising behind the central element, a mountain, designed by Vasilije Popovic-Cico.

Two days later the newspaper Nova Makedonija, the organ of the People’s Front of Macedonia functioning as an official journal, published this law together with an image of the coat of arms and an explanation:

The coat of arms of the People’s Republic of Macedonia is a symbol of freedom and brotherhood of the Macedonian people and the wealth of the Macedonian land. The wheat stalks, poppy fruits, and tobacco leaves represent the wealth of Macedonia and the diversity of its economy. The five-pointed star symbolizes the war of national liberation through which the Macedonian people won freedom. The national motif on the ribbon expresses the richness and beauty of the national essence. In the middle of the field is Mount Pirin, the largest in Macedonian and the center of the People’s Liberation Wars in the past, and the flowing river t is the river Vardar, the most famous river in the Republic. Pirin and Vardar simultaneously represent the unity of all parts of Macedonia and the ideal of our people for national unification. The sun represents the free and creative life in Macedonia (Hapoднoтo 1946).

The arms of the People’s Republic of Macedonia are a symbol of freedom, fraternity, and the wealth of the Macedonian land. The five-pointed star is a symbol of the National Liberation War (as a means of gaining freedom rather than a symbol of Communist ideology). Among the main internal elements, the mountain and the river represent the Pirin and Vardar parts of Macedonia. The two elements together represent the “unity of all parts of Macedonia and the ideal of our people for national unification.” The ideal of national unification, was still alive with Josip Broz Tito and Georgi Dimitrov’s idea of a Balkan Federal Republic, uniting Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, which would have merged Vardar with Pirin Macedonia.

The sun symbolizes freedom and creativity, and meant that now the people could freely declare themselves Macedonian in every respect. The symbolism coincides fully with the meaning of the texts of the two anthems—the sun of freedom. The elements collectively symbolize the liberation and unification of the material and spiritually rich Macedonia through the National Liberation War.

The use of different versions of the coat of arms can be traced through its presence on the cover of the Official Gazette of the Federal Unit of Macedonia established on 18 February 1945. Until number 25 (10 August 1946) on the front page it carried the coat of arms of Democratic Federal Yugoslavia. Official Gazette number 24 (30 June 1946) published the coat of arms of the Peoples Republic of Macedonia appearing on the cover with the text of the Law alongside an image of the arms. From the next issue, number 25 (10 August 1946) it carried the new arms.

The slightly altered arms appeared in the first constitution adopted 31 December 1946. The ribbon’s text was omitted entirely (Уcтaв 1946). The wax seal attached to the constitution contains the new design of the arms, which appeared in the Official Gazette number 17 (23 April 1947), showing a design combining the old and new arms. Beginning with number 26 (6 August 1947), the new design of the arms appeared, with an elliptical instead of circular field. This design would be used for the next 62 years (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

(a) Coat of arms of NRM from Official Gazette, 1946 and 1947; (b) Colored version of Popovic-Cico’s 1946 arms.

The arms began to be used in public and also in people’s homes, appearing on a 1947 calendar published in the newspaper Nova Makedonija on 29 December 1946. The arms have a slightly different design, the sun is represented by 13 visible rays emerging from the sun and spreading beyond the arms throughout the calendar (Kaлeндap 1947).

The emblem of the People’s Republic of Macedonia was not designed according to heraldic principles and therefore is not a true heraldic coat of arms, although it may be analyzed using heraldic concepts. According to the official description, the emblem is a field surrounded by a wreath. Therefore, as a small coat of arms, the field may be considered as a shield, while all elements that are not completely on the oval shield may be considered external ornaments.

The shield is oval, one of the heraldic types of cartouche. The shield’s blazon should give the colors of the fields. The official description does not define the colors, but we can attempt to blazon the colored version on Popovic-Cico’s 1946 arms (Figure 15b). The blazon of such a composition would be: Bleu celeste, a rising sun proper, a mount Azure issuing from waves Argent (Joнoвcки 2015, p. 157).

A wreath although not unknown in classical heraldry, together with the red five-pointed star, demonstrate socialist design.

In later versions of the arms, the relationship and distribution of the elements in the field changed. The mountain on the 1946 arms is 1/4 of the height of the field, on the 1947 arms it is 5/8 of the height of the field (its area increased by 2/3). The solar disk is reduced slightly in diameter, but raised so that its upper edge moved from 1/3 to 2/3 of the height of the field. The ratio of the diameter of the sun to the field is approximately 1:2.

A more recent theory holds that Popovic-Cico knew of the 16-rayed sun and secretly included it in the arms of the People’s Republic of Macedonia. This theory is based on how eight rays are visible on the arms, leaving eight more rays in the part that is not visible. However, an extrapolation from the number of visible rays in the 1946 arms indicates that the sun has 31 rays in total. In the 1947 arms, depending on the extrapolation method, the sun has 17 or 18 rays. In no case is a 16-rayed sun hidden in the arms (Joнoвcки 2015, p. 168).

Neither the Constitution nor any other Law provided specifications for the arms of Macedonia, resulting in many variants—differing mostly in the size of the five-pointed star—which often surface when the arms are printed, embroidered, or placed on other materials. Each institution has its own version of the graphic design.

4.5. Municipal Heraldry

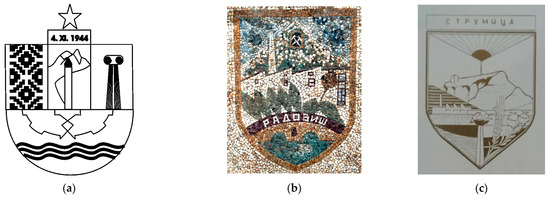

The Socialist Republic of Macedonia had several territorial divisions after the Second World War. Then, in 1965 districts were abolished and a single-level administrative system with 32 municipalities was introduced (with the capital city, Skopje, as a separate administrative unit with 5 municipalities). The territorial divisions were governed by the Constitutional Law, which made no mention of arms or flags of the municipalities, so there was no regulation at all, and some municipalities used socialist “coats of arms”.

The influence of “socialist heraldry” was strong, with the landscape as the most prevalent concept of Municipal “Coat of Arms” in the Republic of Macedonia. The core heraldic idea of the use of general symbols, as used in the heraldic tradition, to represent specific attributes and qualities is rather new and is hardly getting to its proper place. Rather, the design of Arms is more “all you can put on a shield” with specific real elements of industrial and farming objects approaching photographic presentation.

According to Milosh Konstantinov, in 1972 only seven municipalities responded positively when asked if they used a coat of arms: Skopje, Bitola (Figure 16a), Kumanovo, Krushevo, Ohrid, Struga, and Radovish (Figure 16b). All coats of arms were designed in the socialist style. Five Municipalities answered negatively, and the rest did not bother to answer (Koнcтaнтинoв 1972). Two other, Tetovo and Strumica (Figure 16c) also used arms from the 60s.

Figure 16.

(a) Arms of Bitola; (b) Arms of Radovish; (c) Arms of Strumica.

5. Heraldry as Science and Art

5.1. Beginnings

The development of interest in and the study of coats of arms and heraldry can be divided into 4 levels: recognition, collectibles, study and a developed phase (Joнoвcки 2019, p. 106). The first, stage—recognition—that is recognition of the existence of heraldic emblems and heraldic compositions, often applied to various objects. At this stage it is not possible to distinguish whether the emblem is really heraldic or an approximation.

The second stage—collecting—is “collecting images” with coats of arms where only basic information about the coat of arms is known, e.g., its bearer. The third stage is study-a study of the relationships and circumstances of obtaining, displaying, and inheriting the coats of arms and possible changes, as well as the parties involved.

The fourth, developed phase, is the study of rules and principles, for composition, ratio of Figures, etc., but also blazoning—the terminology and syntax used in the technical description of coats of arms. An important part of this phase is both the practical and the problematic approach. The practical approach is creating coats of arms, and the problematic one is what can and what cannot be used/done, or what is better to do when creating coats of arms.

5.1.1. Zhefarovic

The first person to deal with heraldry in Macedonia and beyond in this area was Hristofor Zhefarovic, Macedonian painter, icon painter, copper engraver, born in Dojran. He studied in Thessaloniki and then left for the Karlovac diocese. He achieved great fame among the South Slavs as a result of his engraving and publishing work, as well as having the first Serbian printing shop in Vojvodina, present day Serbia. He died in 1753 in Moscow. In 1741 he published the Slavic translation of the Stemmatographia of Pavle Riter Vitezovic, which was published in 1701 in Latin. Zhefarovic translation was published on 21 October 1741 in Vienna, on the day Arsenie was confirmed as a patriarch and to whom Stemmatographia was dedicated. Zhefarovic added several pages to the translation of the original book: eight engravings with two and eight engravings with one saints or rulers, as well as a portrait of Patriarch Arsenie and the coat of arms created for the Patriarch. The illustrations use heraldic hatching to indicate the colors on the coat of arms. The Viennese master Mesmer also worked on the Stemmatographia, engraving Zhefarovic’s drawings in copper. The drawings are too similar to those in Vitezovic Stemmatographia. First is given the coat of arms of the Patriarch, than the coat of arms of Illyria, of the (Serbian) Nemanjic dynasty kingdom, followed by in alphabetical order 56, coats of arms. In the second part of the Stemmatographia, an explanation is given for each coat of arms. Unlike Vitezovic’s Stemmatographia, which was written in Latin, Zhefarovic’s is written in Slavic and was available to everyone whether they were literate or not, as it was an album with pictures of coats of arms, rulers and saints (Maткoвcки 1970, p. 125).

Apart from the translation of the Stemmatographia which will become the first illustrated manual in heraldry, no other heraldic texts by Zhefarovic are known, which puts him in the first phase of knowledge of heraldry, only recognizing and transmitting images with the coat of arms.

5.1.2. Jordan Hadzi Konstantinov-Dzinot

Jordan Hadzi Konstantinov-Dzinot (1821–1882), “heraldry, as a subject, was included in the curriculum for third grade students (“The first (oldest) children”) from the educational process he performed at the school in Veles and Skopje, probably in Prilep as well” according to Shoptrajanov (Шoптpajaнoв 1999, p. 62). Dzinot was a great follower of the great Croatian revivalist Ljudevit Gaj (1809–1872), from whom he probably inherited his love of heraldry. No heraldic works of Dzinot are known. The only teaching tool available to Dzinot was presumably Zhefarovic’s Stemmatographia.

5.1.3. Diaspora

Other important figures from this period who are from Macedonia, but lived and worked in Bulgaria, are Georgi Balaschev and Stefan Badzov.

Georgi (Gjorgji) Balaschev (1869, Ohrid-1936, Sofia) was an historian and publicist. He graduated from the Thessaloniki Exarchate Gymnasium and went to Sofia where he studied history, then to Vienna where he graduated in Slavic studies. He was a teacher at the first Sofia Boys’ High School and worked at the National History Museum in Sofia. He was an acquaintance of Krste Pertkov Misirkov, the founder of the modern Macedonian language, from their joint residence in Belgrade (1889) and in Sofia (1890), and he was part of the Young Macedonian Literary Society, and of the newspaper “Loza” which he publishes under the pseudonym Ezerski. He wrote an article about the Bulgarian state coat of arms in the magazine “Minalo” in 1909 (Бaлacчeв 1909, p. 175).

Stefan Badzov (1881, Krushevo-1953, Sofia). In 1906 he finished study of decoration and fresco painting in Prague, and left for Bulgaria where in 1908 he became a professor at the National Academy of Arts in Sofia, teaching decoration. He designed medals, diplomas, banknotes, stocks, emblems, stamps and more. He was the designer of the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Bulgaria in 1927. His other works in heraldry are not known.

5.1.4. Solovjev

Alexander Vasilievich Solovyev (1890, Kalisz near Grodno, Russian Empire, now Poland-1971, Geneva) was a Russian historian specializing in medieval history and medieval heraldry. He was educated in Warsaw, then within the Russian Empire, where he graduated from the Faculty of Law in 1912, and then the Faculty of History and Philology. Then, in 1917 he fled Russia and in 1920 came to Belgrade where he worked as an assistant at the Faculty of Law. After World War II he was not accepted by the communist authorities and in 1951 fled to Geneva where he worked as professor of Slavic studies. He studied Illyrian heraldry and published many articles, the most important of which are The Origin of Illyrian Heraldry and the Ohmucevic Family, Contributions to Bosnian and Illyrian Heraldry, and History of the Serbian Coat of Arms, published in Melbourne in 1958. He was a member of the International Academy of Heraldry from 1967. He died in Geneva in 1971 (Aлeкcaндap Coлoвjeв n.d.).

His connection to Macedonia is his article “Flag of Stefan Dušan above Skopje year 1339” Published in the Journal of the Skopje Scientific Society in 1936, making it the first heraldic article published in what will become N/S/R Macedonia (Coлoвjeв 1936, p. 345).

5.1.5. Shoptrajanov

The first to deal more with heraldry was Georgi Shoptrajanov, born in Veles on 2 February 1907, a Macedonian philologist, university professor and cultural and educational figure, the first Macedonian doctor of linguistics and literature. He completed his primary education and high school in his hometown. As a student at the Faculty of Philosophy in Skopje (1926–1930), on 4 September 1927, he was elected an assistant and so became the first Macedonian with a university title. Shoptrajanov, specializing in Dijon, Geneva, Paris and Burgundy where he became interested in heraldry while working on his doctoral dissertation which he defended in 1935. In 1937 he was accepted as a corresponding member of the Société Française d’Héraldique et de Sigillographie (French Society of Heraldry and Sigillography) of Paris. After the liberation he was the first director of the National Library in Skopje until 1946, and then he was one of the first professors at the Faculty of Philology in Skopje. He died in Skopje in 2001 (Mлaдeнoвcки 2009a).

Apart from his book entitled “Heraldry, Sigillography and Exlibris”, published in 1999, in which, despite the title, he deals little with heraldry, no other works by him dedicated to this field are known.

5.2. Heraldry in SR Macedonia

5.2.1. Antoljak

Stjepan Antoljak, born in Doboj on 29 August 1909-an historian, university professor, member of the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts, dealt with heraldry on a more serious level. He graduated in history (1933) and received his doctorate (1935) from the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb. He was the director of the State Archives in Zadar (1946–1952), worked as a research associate at the State Archives in Rijeka (1953–1956), was a professor at the Faculty of Philosophy in Skopje (1956–1969, 1969–1975 part-time), in Prishtina (1963–1969). He was the head of the Department for Ancient and Medieval History of Institute of National History in Skopje (1967–1971) a member of the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts, (from 1979). He died in Zagreb on 14 May 1997 (Kopoбap 2009, p. 71).

Stjepan Antoljak taught auxiliary historical sciences and published a book of the same title at the University of Skopje, from 1966, which includes a section on heraldry. Antoljak gives an initial overview of heraldry by listing sources, briefly paying attention to the coats of arms of the republics in SFRY. He is the first to mention the Macedonian coat of arms and its two editions as a Or a lion Gules and vice versa. He was the first person who gave a definition of heraldry in Macedonia: “Heraldry is an auxiliary historical science that deals with the study of the origin and development of coats of arms according to the established rules and determines the manner of artistic and descriptive representation of the coat of arms.” (Aнтoљaк 1966, p. 268).

For Stjepan Antoljak: “The coat of arms is a permanent designation of individuals, corporations, political and ecclesiastical institutions and organizations, expressed by means of art, according to established and certain rules.” (Aнтoљaк 1980, p. 177).

5.2.2. Matkovski

Aleksandar Matkovski was an orientalist historian, born in Krushevo on 30 May 1922. He was a member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and a participant in the National Liberation War. After the Liberation he graduated from the Pedagogical Schools in Skopje and Belgrade and the Faculty of Philosophy (history group) in Skopje in 1951. In 1957, he received his doctorate at the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb and became the first Macedonian doctor of historical sciences. He also graduated from the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade-Oriental Philology Group in 1961, becoming the first Orientalist in SR Macedonia. While at university, he was employed as a teacher in several primary and secondary schools (until the end of 1954), and then began his scientific career at the Institute of National History until his retirement in 1987. He was elected a corresponding member of the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts in 1986, and a full member in 1991. He spent many years studying in Cairo, Baghdad and Istanbul. In addition to the Ottoman period, he dealt with other topics from the Macedonian past, as well as the history of the Jews in Macedonia, Macedonia in the works of foreign travel writers and others. He died on 15 April 1992 (Mлaдeнoвcки 2009b, p. 928).

Matkovski was the first to deal more seriously with heraldry. He became interested in heraldry when, according to his wife, he found out that in a monastery near Fojnica in Bosnia, there was a Roll of arms, in which, besides the other coats of arms, there was also the coat of arms of Macedonia (Maткoвcкa 2001). Sometime around 1964 he visited the Fojnica Monastery, where he photographed this coat of arms (AE 53/1-5). In 1968 he began writing articles on this topic, which he published in various magazines. His legacy at the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts, the Foundus Aleksandar Matkovski, contains manuscripts of his articles, copies of articles he used, correspondence, as well as bibliographic materials that he used or tried to find.

Thus, in the fundus there are 78 numbered sheets with data for bibliographic units, as well as their signature in the National and University Library in Skopje or in the library of Institute of National History if it is available in these libraries, i.e., it is indicated is not part of the Library (21) (AE 64/1-159). The bibliographic units are taken from other articles and books, which Matkovski thought would help him.

There are mostly old works, three from the 16th century, two from the 17th century, one from the 18th century, and 16 from the 19th century. From the 20th century onwards, 18 are from before the First World War, 18 from the interwar period, and only two from after the Second World War. Some do not have a date. The latest bibliographic unit is Aleksandar Solovjev’s book, History of the Serbian Coat of Arms, published in Melbourne in 1958, which says it should be borrowed from the Belgrade library. It is clear from this that his views were strongly influenced by the literature published before the Second World War, primarily by the works of Aleksandar Solovjev.

From correspondence with colleagues, the oldest preserved letter in the fundus is from 1966, sent from Sofia, Bulgaria. It says “the sender is illegible” (AE 63/I-III). However, Stojan Antonov recognizes the signature-Todor Gerasimov (1903–1974) professor of numismatics at Sofia University. In it, Gerasimov recommends to Matkovski reference works on the coats of arms of the Balkan countries: the article by Balaschev and the works of Solovjev. This determines more closely the time when Matkovski’s interest in heraldry appears, or more precisely the history of the Macedonian coat of arms, as well as its cataloguing. Starting sometime in 1968. Matkovski wrote several articles and letters in the media, several of which are preserved in his legacy from the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

There are two articles that are not dated. The first is probably from the early stage of research on this issue. They are: “The oldest Macedonian coats of arms” an article about the Macedonian coat of arms in the coat of arms of Korenic-Neoric, unknown date (AE 52/1-9). The second is from a later period-”Macedonian coats of arms in the past”-a popular text, without footnotes, which, in 12 pages, makes an inventory of the coats of arms found of Macedonia until then, an unknown date (AE 46/II/1-12).

During 1968, he worked on the book with the working title “The old coat of arms of Macedonia and other Macedonian coats of arms (Contribution to the Macedonian heraldry)” (AE 45/1-377). The text is written in pencil on paper, often in a different format. Notably, the text is written on the back of various documents such as reports, invitations, forms, etc., but also on wrapping paper, even on napkins. Often parts of the leaves are cut off that have probably fallen out of the text.

The book was then typed on a Latin typewriter, from which proof prints were made and given to the author for correction, with marked places for pictures. The Matkovski fundus also has several sets of zinc clichés needed for color printing of the coats of arms. The whole process took two years, and the book was published in 1970, it mainly deals with the presence of the lion in the Illyrian coats of arms. The book contains a modest part on theoretical heraldry and appropriate terminology, which is probably owing to the fact that Macedonian heraldic thought was in its infancy and lacked a more significant explanation for the symbolism of the lion.

The most fruitful year was 1969 for letters and articles, when Matkovski was most engaged in writing his book.

“The Macedonian coat of arms from 1340 does not exist”—a letter reacting to the article published in the Journal (Жypнaл) on 11 October 1969 (the first day of the fight against fascism in 1941). According to Matkovski, the author of this article is Slavko Dimovski, as well of other articles in daily newspaper Nova Makedonija and the magazine Macedonia on the House of Emigrants. In the letter, Matkovski mentions that he personally, and not Dimovski, was the first to see and present to the Macedonian public four years before the Fojnica Armorial and the Macedonian coat of arms. In the letter typed on five pages, Matkovski wrote about the previous knowledge of the origin and dating of the Fojnica Armorial, refuting the thesis that the Macedonian coat of arms presented there was from 1340 (AE 53/1-5).

“The oldest coat of arms of Macedonia”, published in History, year V., 1969, book 1 (AE 49/1-15). In this article, Matkovski present an overview of the beginning of heraldry in general and of the Illyrian heraldry of Ohmuchevic, and completely over took the narrative of Soloviev. Finally, he mentioned the coat of arms of Macedonia only from the armorial of Korenic-Neoric from 1595.

“Old Coat of Arms of Macedonia”, published in the Yugoslav Historical Journal 1969, 1,2. The text is on 12 typed pages, plus three pages of notes. He mostly quotes Aleksandar Soloviev and his two works: “The Origin of Illyrian Heraldry and the Ohmuchevic Family” from 1933. and “Contributions to Bosnian and Illyrian Heraldry” from 1954 (AE 47/1-15).

Matkovski did not limit his heraldic opus only to Macedonia and its heraldry. For example, he also wrote about the “Heraldic representation of the Ottoman Empire in Europe” published in Glasnik INI 1969, XII, 1-2 (AE 229/I).

Among his more important articles are “Albanian coats of arms in the past” published in Albanian in Pristina in 1969 (Matkovski 1969). Thus, Matkovski was not only founder of the Macedonian heraldry, but also Albanian heraldry. The text contains 103 typed pages, with five photos and three negatives of coats of arms from Albania (AE 68/1-103).

After publication of the book, he wrote letters of reactions. An example of a reaction is to a text published in “Borba”in Belgrade on 10 October 1971 by Kosta Timotejevic about the coats of arms of the Yugoslav republics. Matkovski reacted to the statement that Macedonia until 1945 had no arms. He explained in five pages that such a coat of arms had existed and invited him to consult his book “Coats of Arms of Macedonia” (AE 50/1-10). This is the latest article from Matkovski’s fund at the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

The same year, a collection of 21 slides from the coats of arms and a small 16-page brochure with a description of the slides were published and presented to schools. The publication is at the Institute for Cultural-Educational and Educational Film of SR Macedonia, Skopje (Maткoвcки 1972).

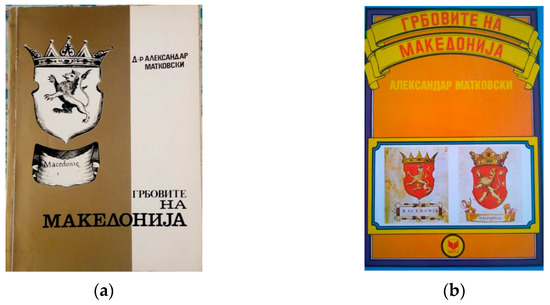

The book Coats of arms of Macedonia was republished in facsimile in 1990 (Maткoвcки 1990a) from which was inspired the interest in heraldry. Matkovski started writing letters in newspapers again in 1990, discussing a possible coat of arms for the future independent state of Macedonia (Maткoвcки 1990b). In the database of National and University Library, the search for “Aleksandar Matkovski” returns 96 bibliographies, two of which are only for heraldry, the book The Coats of Arms of Macedonia in two editions from 1970 (Figure 17a) and 1990 (Figure 17b).

Figure 17.

(a) One of the several 1970 covers; (b) 1990 Cover.

Matkovski defined heraldry as an “auxiliary historical science that aims to study the origin and historical development of the coat of arms in general or on individual coats of arms, to give established rules according to which the coats of arms should be composed, and then to be artistically made, to determine the manner of reading (blazoning) the coats of arms and investigating who owns a particular coat of arms” (Maткoвcки 1970, p. 7).

Matkovski, on the other hand, defined the coat of arms as “a special figure, or symbolic shaping, mark, emblem, i.e., an inherited, unchanged sign, composed according to the rules of heraldry that serves to distinguish a particular person, gender, society, institution, city, district, people, a state, a corporation, a political, economic or church organization” (Maткoвcки 1970, p. 14).

5.2.3. Konstantinov

Milosh Konstantinov, born in Resen on 26 March 1926—ethnologist, historian and publicist, longtime director of the city archives of Bitola and Skopje, and university professor. He finished primary school and high school in Bitola (1937–1946). After graduating from the Skopje Faculty of Philosophy-Group of Ethnology (1954), he was appointed director of the Archive in Bitola (1956). He received his doctorate from the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics in Skopje (1960). Later he was appointed director of the Archive of Skopje (1964). After retiring (1984) he was elected full professor at the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics in several subjects of ethnology. He died in Skopje on 7 June 1993 (Mлaдeнoвcки 2009c, p. 792).

Milosh Konstantinov in 1972 in the article “Seven city coats of arms” gave the first analysis of “coats of arms” (according “socialist heraldry”) of seven municipalities in SR Macedonia. He was the first in Macedonia to conduct a survey among municipalities on whether they use coats of arms, to which only seven municipalities responded positively. Coats of arms were designed in a socialist way, however Konstantinov made an analysis of the shield and other elements of the coats of arms (Koнcтaнтинoв 1972, p. 30). Konstantinov wrote a letter in the daily press in 1992 calling for the observance of heraldic rules when determining coats of arms (Koнcтaнтинoв 1992).

6. Conclusions

Heraldry in Macedonia, a region in south-east Europe, had its first reflections of European heraldic practices that are emerging among several noblemen that ruled parts of this region. By the end of the 14th century, under the control of the Ottoman Empire, any real possibility of bearing arms was soon eliminated. The heraldry connected to Macedonia, further developed in Europe through the attributed arms of: Alexander the Great of Macedonia, kings of Macedonia or Macedonia especially in the Illyrian Armorials, only to return to the region in the 19th century.

In 1944 the Vardar Macedonia became the Peoples Republic, it did not look toward a heraldic heritage for creating the arms for the newly created state but looked for Socialist style symbols. On the eve of gaining its independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, the heraldic heritage had a stronger influence, but it was not sufficient enough to prevail (Jonovski 2018).

This paper considers heraldry as a multitude of coats of arms, and the armorial knowledge and art. It covers the earliest preserved heraldic motifs and coats of arms found in Macedonia, as well as the attributed arms in European culture and armorials for Macedonia, kings of Macedonia, and Alexander the Great of Macedonia. It also covers the State and municipal heraldry of the P/SR Macedonia, as well as the development of heraldry as both a discipline and science and the development of Heraldic thought in SR Macedonia.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources