Abstract

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a global issue that is particularly prevalent among women of color. Many providers in GBV-based organizations are also survivors of GBV, which affects the way these providers lead social service and social justice organizations. Yet, many institutions at the intersections of GBV fail to address the impact that GBV has on the mind, body, and spirit of the women who work there. Using historical trauma as a lens, this qualitative study incorporates semi-structured interviews with women of color in leadership to explore the various ways trauma manifests itself among survivors of GBV. Thematic analysis with 10 women of color survivors of GBV in leadership revealed four ways trauma manifests itself, how it impacts the women who have experienced it, and survivors’ need for personal and organizational healing. In addition, a conceptualization of a healing justice model that these findings inform is presented. This article has implications for GBV survivors working on the frontlines of GBV-based organizations along with implications for how the organization can facilitate healing among employees.

1. Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) is one of the world’s greatest public health and human rights violations. GBV is a global epidemic with devastating consequences, affecting millions of women and girls a year (United Nations 2020). GBV involves a range of sexual assaults such as child sexual abuse, forced prostitution, sex trafficking, femicide, rape, and domestic violence (Edleson et al. 2015) as well as sexual exploitation during and after conflicts and natural disasters (Sprechman et al. 2014). However, the burden of GBV is not equally shared across racial and ethnic groups. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that intimate partner violence is the number one cause of death for young Black, Hispanic, and Native American women of color under 30 (as cited in Jeltsen 2017). Furthermore, women and girls of color are at greater risk for domestic violence, sexual assault, intimate partner homicide, and near homicide (Women of Color Network 2006). The prevalence of GBV occurrs in the context of historical trauma and oppression (Hamby et al. 2020).

Women constitute half of the world’s population and comprise a large majority of workers and leaders in social service and social justice organizations (Maternal and Child Health Bureau 2012). Young and adult women of color are more likely to experience GBV (Jeltsen 2017); thus, any response, prevention, and intervention effort to end GBV must consider women of color. In addition, women of color in social service and social justice organizations may also be survivors of some form of GBV, although this is an understudied phenomenon. Studies document the presence of trauma and “burn-out” among healthcare staff such as nurses, doctors, and social workers (Gorski and Erakat 2019). Additionally, there is extensive research regarding the trauma histories and needs of workers in domestic violence intervention (Wathen et al. 2015). Moreover, the impact of GBV on women’s social, psychological, and economic survival is well known (Tsirigotis and Luczak 2015); however, the mental, spiritual, and emotional effects of GBV on the health and well-being of women survivors of color who lead organizations are lesser known. Additionally, there is a lack of research that specifically explores the relationship between survivors in leadership, their healing needs, and organizational trauma. Therefore, more research must be dedicated to the development of a survivor-centered, culturally competent, and spiritually-responsive healing approach for women of color in leadership (Dutton and Kropp 2000). While the strengths of women of color are relevant for their leadership, so is their survivorhood. The focus of this paper is on the pain and harm that oftentimes goes unaddressed (Lorde 1984).

In this study, the needs and experiences of 10 women of color in leadership across the United States, who are also GBV survivors will be presented. The four central questions that guided the study were (1) How did you come into your leadership position? (2) What were the strengths, challenges, costs or benefits of being a woman of color, survivor and leader? and (3) What healing needs and practices did you incorporate in your work or life, if any? and (4) Why was it important for you to create healing spaces in your lives, if those existed. The study was situated in and contributed to GBV and historical trauma literatures. The goals of the interviews were to (1) give voice to survivors on the frontlines, (2) allow survivors to identify the impact of GBV, and (3) identify survivors’ healing needs on a leadership- and organizational-level.

The remaining sections will review prior literature on GBV among women of color, detail the methodology and findings of the current study, and present a discussion of the findings along with recommendations for future practice.

2. Background of the Problem

2.1. Gender Based Violence and the Cost to Women of Color

In 2010, women comprised 50.8% or half of the 308,000,000 total U.S. population (Maternal and Child Health Bureau 2012). A woman in the United States experiences some form of sexual assault every 98 seconds, accounting for over 32,100 victims a year (Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network 2020). Twenty women in the United States experience intimate partner violence every minute, one in three women have been victims or survivors of domestic violence in their lifetime, and 20,800 calls are made to domestic violence hotlines daily (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence 2020). This number is increasing for women of color, thus increasing the probability that women in caregiving and social justice organizations and institutions—such as social workers, service providers, clinicians, consultants, advocates, organizers, activist, and executive directors—are also survivors themselves.

Thirty-six percent of women who reside in the United States belong to a racial or ethnic minority group, the most vulnerable target for GBV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021). In a report for the CDC, Petrosky et al. (2017) confirmed that the leading cause of death for young Black, Hispanic, Asian Pacific Islander and Native American women of color under 30 is homicide and near homicide by intimate partner violence. In addition, African American women experience intimate partner violence at 2.5 times the rate of White women. Thus, Black, Hispanic, Asian Pacific Islander and Native American women of color are the most disproportionately affected and vulnerable population in the world.

Women of color who have experienced GBV have few places to heal, recover, build resilience, and maintain their health and wellbeing; therefore, women of color might be leading these institutions, servicing clients, and creating programs from a place of spiritual and emotional deficit. These women’s experiences, compounded with historical trauma, can result in depression, self-destructive behavior, numbing, co-dependent relationships, and poor tolerance (Brave Heart 2000). It is assumed that these women are engaged in healing or therapy or have it “together” because they are leading prominent social justice organizations in the grassroots or social sector. Therefore, many workplaces do not have policies or processes to address trauma responses and do not consider the personal and organizational cost of gender-based violence.

In 2017, the National Coalition on Domestic Violence confirmed that 57% of employees who had experienced GBV were distracted, 45% of employees feared discovery, and two in five employees feared that their partner would show up at work (The National Domestic Violence Hotline 2020). Sixty percent of victims of intimate partner violence missed a total 8,000,000 days of work and often lost their jobs as a result (NDVH 2020). Furthermore, 78% of workplace homicide is committed by a women’s intimate partner (NCADV 2020), yet more than 70% of U.S. workplaces do not have a policy in place for domestic violence (NDVH 2020). These numbers become exacerbated for women of color survivors working in grassroots organizations that have small budgets and lack resources. In the context of the organization’s minimal capacity there is a lack of sustainable leadership challenging productivity and program effectiveness. A deficit of responsive policies becomes more evident in grassroots organizations that cannot provide health insurance or other cultural and spiritual incentives that improve their employee’s mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual health, which could contribute to a survivor’s ability to heal and lead.

2.2. Historical Trauma: The Social, Emotional, and Spiritual Impact of GBV

The current political climate of the world demands a resilient individual at the forefront of social justice and social service organizations. However, as more women in leadership disclose that they are survivors, a need for healing is being identified for both the survivor and the organization for which they work. Studies have shown a correlation between domestic violence and a woman’s (a) emotional and cognitive functioning, (b) ability to maintain well-being, (c) access to interpersonal skills, problem solving, and creative thinking, and (d) ability to cope and adapt to one’s environment, including an ever-changing organization environment, leadership position, and rotating staff who may have their own trauma and experience of GBV (Tsirigotis and Luczak 2015; Zamir and Lavee 2015).

Results from the CDC Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study revealed that 64% of people have experienced at least four events of childhood trauma, and the cycle of violence continues well into adulthood (Stevens 2017). Likewise, adults with a history of abuse in childhood have a hard time accessing social cues to produce intimate relationships; as a result, these individuals might develop other coping mechanisms such as disassociation, fear, denial, avoidance, anxiety, and an inability to identify emotions (Zamir and Lavee 2015). This proves difficult for leaders who have experienced GBV because leaders must demonstrate a mastery of social cues, such as being able to identify and communicate feelings, to develop healthy intimate relationships with staff and clients in caregiving organizations. In addition, victims of GBV can develop co-occurring mental health and substance abuse disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder over their lifetime (Mackintosh 2009).

Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart (2000) identified and linked historical trauma to the embodiment and the eventual manifestation of a trauma response of victims and survivors across their lifetime. Brave Heart developed historical trauma response theory (HTR) in 1998 to understand her own unresolved historical trauma as a Lakota clinician and the manifested signs of trauma among the community leaders with whom she worked (Brave Heart 1998). Brave Heart defined historical trauma response as a survivor’s ability to live both in the present and the past while managing depression, anger, and suicidal ideations because they do not feel worthy of living or have survivor’s guilt.

Walters et al. (2011) posited that historical trauma is linked to the concept of embodiment, acknowledging “that bodies tell (his)stories and reveal stories that are not conscious, hidden, forbidden, or even denied by individuals or groups” (p. 184). Specifically, Walters et al. (2011) stated that historical trauma gets imprinted on a cellular level through DNA. This historical trauma is passed down from parent to child, affecting the neurobiology and neurodevelopment of humans (Walters et al. 2011). The effects of historical trauma and emotional wounding can be compounded for survivors of GBV (Holder 2015).

Additionally, historical trauma has been conceptualized as the embodiment of GBV in survivors as internalized oppression (Muid 2006). Historical trauma and violence could thwart a survivor’s ability to be mentally, physically, and emotionally authentic; thus, survivors could develop self-destructive habits and lifestyles wherever they go (Muid 2006). The healing and full recovery of women of color survivors depends on their access to cultural and spiritual practices to heal and grieve (Brave Heart 2000).

Despite remarkable resilience in survivors among women of color in leadership, the effects of historical trauma can last for decades. The effects may not be immediate for someone who after an assault may be vulnerable to later assaults because they take longer to notice threats (Hamby et al. 2020).

Domestic violence survivors can benefit from a culturally safe work environment where they can build enough trust to fully express themselves, disclose any personal trauma, and explain how their work is impacting them (Slattery and Goodman 2009). This expression and disclosure is a necessary part of personal development (Slattery and Goodman 2009). A survey participant from Wathen et al. (2015)’s study stated that “we bring to work everything that happens at home. We can’t compartmentalize or mentally separate these different aspects of our lives” (p. 65). While, Gone (2014) argues that disclosure of historical trauma can lead to more trauma, Beltrán and Begun (2014) report that traditional cultural practices like narrative therapy in relation to historical trauma are important practices for survivors to tell their stories and build resiliency.

The experience is GBV and trauma impacts the physical, mental, spiritual well-being of women of color. Unacknowledged historical trauma in social justice leadership can keep survivors disconnected and disembodied which threatens the mission of the organizations they work in to dismantle violence in their community organizing efforts (Chavez-Diaz and Lee 2015). Section 3 discusses my positionality in regard to the study topic, along with the data collection and data analysis procedures used to explore the perspectives of women of color who lead in the GBV field while being a GBV survivor.

3. Methods

3.1. Positionality

This study was informed by my positionality as a Latina, lesbian woman of color survivor, healer, community organizer, and advocate for over 25 years. The priority questions I began with were informed by my positionality and experiences in the GBV movement. I have personally engaged in my own healing as a survivor and examined the impact of healing on the mind, body, and spirit of survivors in leadership. I have been the executive director of a healing organization led by and for other women of color survivors and have had the honor to lead, participate in, and be a witness to the personal healing and transformation of other women survivors on the frontlines.

Over the past 10 years, I have immersed myself in national organizations and coalitions at the intersections of social justice as an executive coach and self-healing consultant, providing personal and leadership development, capacity building, and training for survivors in leadership. In accordance to best practices in qualitative research, I kept track of my own experiences and reactions in the form of journaling and memo-writing (Kafle 2011). I used my writing and reflection process to uncover and notice the differences between what I was observing, describing, and interpreting and my own lived experiences (Creswell 2013; Van Manen 1997).

3.2. Data Collection and Procedures

Study participants were required to meet each of the following inclusion criteria: (a) identify as a woman in leadership in the GBV field, (b) be between the ages of 30–65 years old, and (c) identify as a survivor of GBV. Participants included people of various sexual orientations, racial, and ethnic identities (see Table 1). Participants filled various professional roles, such as organizers, consultants, healers, social workers, and executive directors. Over the span of 2 months in 2019, I used my personal and professional contacts, including previous organizational clients, to recruit participants that met the criteria. Additionally, participants were asked to refer others through word of mouth (snowball sampling) to ensure a diverse group. I asked each interviewee to recommend three people who met the criteria. No incentives were provided.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

I began the interview process by explaining the study and reviewing the consent form. The semi-structured interview protocol consisted of ten pre-planned question prompts with sub-questions, if needed. I asked participants about their experience in leadership as a survivor, including how they began their journey into leadership and changes they experienced. I also asked participants questions about their healing journey, spiritual practices, challenges and successes. The discussion during the interview was reflexively probed as unanticipated or emergent information arose during the interview. Interviews were conducted over the phone and were 2 hours in length. Interviews were not audio recorded but extensive notes were taken during the conversation, which served as the dataset.

3.3. Data Analysis

Following a thematic analysis approach (Creswell 2013), I read and reread the data to generate initial themes. Participant terminology and quotations were clearly captured, and I used the central research questions to begin analysis. I referenced the emerging themes within and across interviews to identify categories. The relationship between categories became four overarching super-themes that described the impact and cost of trauma as well as the need for personal and organizational healing practices. Quotations that best represented the themes across organizational affiliation, professional role, race, gender, and age were selected for the findings. Section 4 provides the study findings and four overarching themes.

4. Findings

4.1. Overview

The analysis revealed four main themes: (a) shame as a primary example of the ways trauma manifests itself, (b) the personal cost of being survivors in leadership, (c) the need for personal healing, and (d) the need for organizational healing.

The main themes are presented in the sections below. Participants are identified by professional role and age, with minimal participant-specific information to protect the identities of the participants. Additionally, the identities listed next to each quote were those that were most important to the participant. Although it was very clear that the participants followed their hearts into the leadership positions they are in today, they were not aware that being a survivor themselves was going to cost them so much. Participants described the challenges they faced as survivors in leadership, the trauma of shaming they would experience from other co-workers in the field, and the burden of having to manage their own shame endemic to survivorhood. In addition, participants shared the burden of having to confront the additional judgement because they were women of color.

4.1.1. Shame

The leaders interviewed in this study indicated that shame existed as a result of the trauma of GBV as well as experiences of harm in their workplaces. All 10 participants described shame as an internal dialogue that affected their ability to lead; for example, participants thought that they did not belong, that they were not good enough, or that the experience of GBV was their fault. Participants also mentioned being shamed by colleagues when having a trauma response or taking time to heal, such as crying in the workplace. All 10 participants referred to a moment of not being extended the same grace as a leader that a client or staff member-survivor would have received. One participant shared that leading an agency looked differently than when she was a front-line staff.

Similarly, another participant who has worked in coalitions across the United States still holds a lot of feelings from the shame she experienced being the only woman of color survivor in her job.As a front-line staff accountability and responsibility is not on you. As a leader, there is shame to talk about what is going on in your life.(Black, Executive Director, 45)

I was told that as a survivor, I could not be a volunteer and as a survivor I could not be professional. So, depending on what hat I was wearing, I always felt like I was making things up, like I was an imposter constantly asking myself why are these people are listening to me?(Latina, Director, 50)

Consistent with the findings in the study, one participant shared that women of color need an intimate leadership circle of other women around them, which is why she created a board of directors where she could exist without shame. She said that having this level of support around her helped her be a better leader.

I knew I needed a board that had no judgment or made me feel shameful if I needed to cry or felt depleted or if I made a mistake.(Black, Executive Director, 45)

A recent major shift in how women manage and disclose stories of GBV has occurred due to changes in the current social, economic, and political landscape. The shift has encouraged more women in leadership to disclose their own stories; however, participants in this study identified shame as a barrier. One participant affirmed that the “biggest change is that the folks doing the work are survivors themselves” (Black, Queer, Training Coordinator, 35). However, leaders who are GBV survivors are often unable to share their stories due to the shame of being a survivor in leadership and the stigma attached to being a professional that may also need services.

4.1.2. Personal Costs of GBV

For some participants, the cost of GBV has been too high. Participants were asked about the impact that being a survivor in leadership had on them. Participants reflected back on how their minds, bodies, and spirits had changed. Participants also discussed the impact of trauma in their lives and leadership. They described their regrets and parts of themselves that they felt were lost during their journey as leaders. One participant articulated a very personal cost that she still is grappling with after being in the leadership for 20 years.

Another participant reflected on her experiences working for an organization that only served survivors, and how she had to create a safe space for herself and other women of color leaders within the organization to talk about the impact of being a survivor in leadership.When I first came into the work I struggled and didn’t take a vacation for the first 3 years. I am looking back and wondering if I will ever be married and have children.(Black, Executive Director, 45)

One participant spoke about the impact of GBV manifesting in her mental health because she could not be her authentic self and did not have anyone to talk to about her trauma.My life is my work, it is all-consuming. Being the only Black woman in my coalition, I sometimes feel like I have given in to respectability politics and have lost my voice. There are times I am silent when I wish I can rage instead of swallowing my feelings.(Black, Queer, Training Coordinator, 35)

Participants shared that leading is an all-consuming job for survivors; thus, survivors who lead do not have space for healing or respite. All participants considered healing both a personal and organizational need. Participants shared that the emotional labor required to work with survivors is compounded when one is also a GBV survivor.As a survivor I have been hardened. My experience has framed how I think, the decisions I make and the expectations that folks have of me. There is not one person that I go to as my whole self. In this job you cannot have weaknesses, so I go in pieces, never as a whole person.(Black, Executive Director)

4.1.3. Need for Personal Healing

Participants were asked about their personal healing needs as survivors in leadership. In sharing their needs, some participants also shared the possibilities their healing would create for them. Additionally, participants identified the need to create space for healing for survivors in leadership. Their goals included the ability to manage their trauma, so they could have peace and sustainability. One participant spoke about how she wished someone could have told her that her spectrum of healing should match the spectrum of trauma she experienced; healing is not a one size fits all.

There is always a fear inside of me that I will get found out, so I keep my trauma separate. No one ever acknowledges that there are levels of oppression in trauma and there is a difference between healing that you have to immerse yourself in versus a process of healing you engage in in the moment.(Latina, Consultant)

This participant’s goal was to dive deep into her healing, so she could be comfortable in her skin; in her case, personal healing was about finding some level of peace and acceptance. Another participant noted that continuing to train survivors in leadership did not get at the root of their needs. Instead, more training might further perpetuate shame as opposed to fostering healing.

Training is not the answer as a survivor of trauma. I don’t know how to do this while I manage my own trauma.(Black, Coordinator, 35)

This participant recognized that organizations want to keep a professional environment where advocates and workers were experts in the field instead of being emotional; however, these environments are not conducive to the healing of survivors. Eight out of the 10 participants mentioned the need for an alternative to mainstream healing. As women of color, they described healing that would consider their cultural identity, language, and spirituality. Participants expressed wanting access to holistic healing approaches that would connect the various aspects of their identity as leaders, survivors, and women of color. One participant was concerned with the limited access survivors and leaders have to holistic support services from providers with the same lived experiences.

I was a high functioning leader because I didn’t want anyone to know. I didn’t think I was normal and was faking it. It was chaotic to watch myself all the time. I knew I had to come back to myself but trauma has a way of locking into your skin. It wasn’t till I found a holistic doctor that provided me with structure and stability because he spoke to my spirit and mind and understood that my culture and my identity were wrapped up in my trauma.(Latina, Consultant)

Healing spaces are not created by themselves or by outside facilitators; rather, healing spaces are created by the people in the space who are committed to their healing journey. Participants identified that it was imperative for their work places to consider their personal healing needs and create conditions for them to share their own stories of violence and trauma and undo patterns, so they can find freedom in personal and collective healing. Simultaneously, the majority of participants described that working with survivors saved their lives, although there has not been space in the field for them to navigate their trauma.

4.1.4. Need for Organizational Healing

Many participants expressed a deep and persistent need to create a healing space within their organizations and movements. Participants highlighted the need for survivors in leadership to create their own healing team to improve their quality of life and build their personal and organizational capacity. For example, participants stated that women of color in leadership forget about self-care because they think no one could do the work like them, especially if they birthed the organization or were a founder. Therefore, these women forget to put the infrastructure in place to sustain themselves and the organization. As one participant said,

We are in a crisis emergency as it relates to women of color. We need healing heart conversations because we are on life support.(Black, Executive Director, 45)

Participants also expressed a desire to have more healing spaces than leadership development trainings because the work is very personal and triggers women’s own story of trauma. One participant explained that she has attended leadership retreats and trainings where people were coming undone in them. She suggested that survivors in leadership needed a healing space that honored that social justice work is personal. Clients are not strangers; they are part of our community.

I have never met a survivor with only one issue, but systems are not created for that. What we need is a healing space, a place where we can build altars to honor our lives and sees promise in the revolution for those seeking justice.(Latina, Director of Training, 50)

Another participant reflected on the sacrifice that women of color make to help others while processing their lived experiences. She often heard her co-workers talking about how they needed to compartmentalize themselves because personal stories were not welcomed at their jobs.

There still is no space in the movement to end gender-based violence for us to navigate our own story and so people are hurting and struggling.(Black, Coordinator, 35)

In the “Me Too” era, both national and local programs struggle when working with survivors who are also leading the GBV movement. As these woman’s response demonstrates, trauma is showing up in the professional space without organizational systems in place for healing. Women of color in leadership positions in this study shared that they were working in organizational cultures that bred secondary trauma, were revictimizing, and were retriggering to both employees and their clients creating more harm than the harm they have experienced in their lives. Study participants discussed the occurrence of additional damage beyond the experience of GBV participants with which they originally entered the organization. As one of the participants shared,

We have to get to the point where we can say yes, I do this professionally, but my stuff is coming up and I need some support, but what does support look like? What does it mean for women of color to lead agencies of trauma while holding their own trauma? What does it look like on a macro- and micro-level because self-care looks different for women of color.(Black, Executive Director, 45)

In summary, the research findings provided insight into the experience of women of color survivors in leadership. The themes support the need for a framework that (a) honors women of color’s stories and experiences of GBV and (b) acknowledges the personal cost GBV has on their lives and leadership. Participants also suggested that healing is necessary for the sustainability of organizations and the resiliency of people who work in them. Section 5 discusses the study findings in relation to the existing literature and my personal experience as a leader, woman of color, and survivor of GBV.

5. Discussion

If no one sees leaders as survivors, where do they go for support? Who takes care of those doing the work, day in and day out? If it is true that the trauma of GBV shapes leaders, then why is it that women of color have come this far with trauma leading, imagine what these women could do if they had spaces for personal and organizational healing?. What could they create if trauma was not present in their space and when their identity was no longer shaped by an unhealed past?

The data collected from women of color survivors in leadership is timely and pertinent to the social political discourse around the world. These data indicate that gender-based violence has an impact on survivors in leadership. Women in the sample are acutely aware of their personal healing needs as survivors in leadership. In addition, they identified the organizational healing needs necessary for their sustainability. If not addressed, these experiences could pose a threat to women of color survivors in leadership across the country and the world.

The need to understand and create innovative solutions that acknowledge the many ways that trauma manifests in women of color survivors in leadership has never been higher. The participants identified shame as a primary trauma response. Furthermore, participants defined healing to be more than a personal need; rather, healing is a process for recovery and transformation, so survivors can dare to dream, to love, and use their resiliency and power to lead in pursuit of justice.

I believe that every little girl is born powerful, worthy, belonging, and enough before something happens that shapes her identity and impacts the way she loves, lives, and leads. GBV, as described by participants in this study and related literature, harms the spirit of women all over the world. The very qualities that a survivor needs to lead are the very qualities that get diminished by continuous GBV. The study participants courageously shared how they were robbed of their innate power and leadership skills. Some chose to share specific ways that GBV depletes survivors of their spirit, thus keeping them from visioning and understanding the world outside of their own trauma. Participants discussed feelings of anger, fear, shame, and an inherent feeling of feeling like a failure, inadequate, or disappointed. Shame, in these instances, replaced leadership skills with negative self-talk, behaviors based on survival, and scarcity in an effort to find love, safety, trust, connection, and belonging. Shame impacted survivors’ most sacred spaces, such as their homes, their communities, and their workplaces. Just as people’s lives are organized by traumatic experiences, entire organizational systems can also be impacted by a groups’ collective traumatic experience, which “often occurs between traumatized clients, stressed staff, frustrated administrators and pressured organizations that result in service delivery that often recapitulates the very experiences that have proven to be so toxic for the people we are supposed to treat” (Bloom 2010, p. 300).

The personal need for cultural and holistic healing identified by the participants confirms and expands upon studies done with survivors around the world. For example, a study conducted in Sierra Leone among girl soldiers who were survivors of rape revealed that the use of traditional healing allowed the girls to shed their emotional wounds and feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness while facilitating reintegration (Stark 2006). The participants of this study defined integration as the necessary creation of healing spaces with people they trust so they can manage trauma responses and not feel shame. For some survivors, integration in the field of GBV as leaders has saved their lives and has supported their personal reckoning and reconciliation as survivors in leadership.

5.1. The Personal Cost of Being a Survivor in Leadership

As a victim, survivor, and product of GBV, I can account for how I internalized my own experience. I believed that I was at fault for what happened to me and that I deserved it. The participants in the study acknowledged the same sentiment in their sharing of feeling inadequate and carrying guilt and shame. The long history of sexual exploitation and slavery that women of color have routinely experienced has forced women of color to internalize sexual and domestic violence and develop responses that address the behaviors and the patterns that perpetuate individual, institutional, and interpersonal violence against women (Incite 2021).

GBV is deadly when the leader of an organization is also a survivor and believes that she cannot create a different world for herself or other survivors. GBV can play out as internalized oppression in advocates, social workers, providers, executive directors, management, and other staff. This level of internalization shapes how these individuals treat clients and participants, create programs, deliver services, or whether they believe their clients will change. Internalized oppression is the embodiment of trauma that occurs when survivors’ bodies biologically incorporate personal experiences, including the social and ecological context they live in (Krieger 2005). If left untreated, internalized oppression becomes interpersonal trauma that shapes personal lives, leadership skills, and organizational culture.

5.2. The Need for Personal Healing

From domestic violence and sexual assault to intimate partner violence and child sexual abuse, women survivors of GBV who work in the GBV field are coming to work with their own story and experience of GBV. In addition, they are from the very communities they work in while also experiencing firsthand the injustice, poverty, and oppression that their clients experience. Participants in this study described the goal of personal healing as the ability to have peace, acknowledgement, and sustainability in their leadership. Additionally, participants shared the need for work spaces to consider their personal healing as a pathway to liberation.

The personal needs for healing described by the study participants extends the definition of healing to include organizational healing. The description aligns with the work of Zimmerman et al. (2010), who validated the need for a movement that has healing and spirituality at the core: “many of us come into this work because we or the people we love have experienced deep injustice, without awareness, we recycle trauma and create new wounds within the movement, recycling trauma” (p. 16).

5.3. The Need for Organizational Healing

The women of color in the study expressed a deep and persistent need for the creation of healing spaces where they can build altars, have healing heart conversations, and create sacred spaces for those seeking justice. The participants’ connection to their personal need for healing to seek justice and revolution implies that cultural healing is imperative to personal and organizational transformation, recovery, and sustainability.

In this study, healing for survivors in leadership was identified as an ever-evolving process; healing cannot be done through a strategic plan, mainstream leadership staff retreats, or even by implementing health and wellness classes, training, and self-care moments. This definition is in alignment with Robertson (2015), who stated that organizations today need to create an organizational design and practices to evolve, sustain, and operate in an ever-changing political landscape so that organizational leaders can have the ability to sense dissonance and potentially reshape themselves and the organization. The study findings also expand the definition of a political landscape to include the social political landscape that individuals are located in at any given time, including the history of GBV that individuals come into the organization with. Furthermore, the participants distinguish healing that they have to immerse themselves in versus a process of healing that they engage in in the moment.

Women of color survivors introduced the need for organizational healing. Women of color’s experience with mainstream organizational and leadership development is that healing is an individual process that a survivor embarks on as part of therapy or psychological support rather than part of organizational and leadership development. In addition, the subjugation of knowledge regarding the impact of GBV in women of color leaders results in the failure to examine the manifestations of GBV, such as historical trauma and collective organizational trauma. These impacts and manifestations of GBV must be addressed in leadership development.

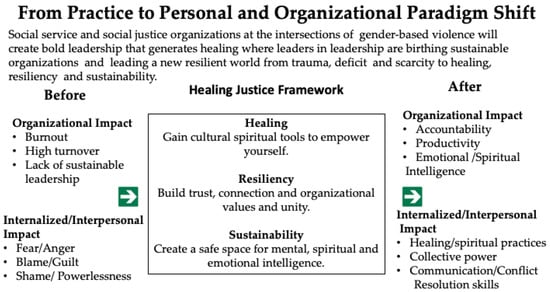

A Healing Justice Framework

Women of color survivors in leadership and the organizations they lead live at the intersections of GBV. Although common factors contribute to GBV across race and ethnicity, each population has unique circumstances that highlight the need for spiritual and culturally specific healing models that speak to women of color survivors in leadership. Therefore, any personal or organizational healing model must be grounded in the historical and generational trauma that impact women of color survivors in leadership; such healing models support individuals and facilitate organizational paradigm shifts from trauma, deficit and scarcity to healing, resiliency and sustainability.

The study findings informed the development of the healing justice framework for women of color survivors in leadership (see Figure 1). The framework counters existing mainstream models of healing and leadership development and centers the personal healing needs of survivors in leadership, making them active participants in their healing. In addition, the framework allows GBV survivors to incorporate self-healing practices into their leadership, further engage in their organizational systems and culture, and shift the cultural norms and systems that sustain violence. Although presented as separate themes in Section 4, the impact of GBV spreads across all areas of a survivor’s life, including their leadership role and their workplace. Thus, GBV is interdisciplinary, varied, and interrelated.

Figure 1.

The healing justice framework uses a multiprong approach to address the fact that survivors are workers and leaders within organizations and the major impact that GBV has on the personal and the organizational system. Bridging healing and social justice supports women in leadership in (a) telling their story of violence and trauma, (b) identifying the impact of trauma on their mind, body, and spirit, (c) identifying how GBV has shaped the way they lead, and (d) learning healing and spiritual practices that will sustain their leadership and organizations beyond funding.

This study is a direct response from a call from women of color leaders across the nation who are disclosing more and more that they, too, are survivors of GBV. From hashtags #metoo and #timesup, the current social, economic, and political landscape has encouraged more women and girls to disclose their own stories and experiences of sexual assault. The healing justice framework uses historical trauma theory to take the individual and the organization through a process of rewriting an organizational history that was created by the stories and experiences of violence, trauma, and oppression among everyone who works there, their clients, and the founding members. The reconstruction of the past is critical in reestablishing a reference point for identity and creating something new so people are not constantly blaming themselves for their conditions (Muid 2006).

When integrated within the organization, the healing justice framework will take organizations through a process of healing with accountability. Healing with accountability is a journey of evolving self-awareness that counters the effects of GBV on the individual while laying a foundation for organizations to address the many layers of internalized oppression. This ever-evolving healing supports the survivor in letting go of the shame, self-blame, and guilt that results from GBV. In addition, the healing justice framework simultaneously creates safe spaces of healing within the organization so that providers, advocates, and leaders can tell their stories of survival. Safe spaces are not created by themselves or by outside facilitators; rather, safe spaces are created by the people in the space who heal together and hold each other accountable for what they are creating.

Section 6 presents the potential limitations and directions for future research, programming, and practice.

6. Directions for Future Research

Healing justice is to organizations what social justice is to movements. We walk into spaces with a world and history behind us and we need to acknowledge that. A lack of acknowledgement creates conflicts within the individual spirit and the soul of organizations.

The results of the study helped inform the development of a healing justice framework that addresses the personal and organizational needs related to women’s experiences of abuse and neglect. The conceptual healing justice framework has a lot of implications for the field of GBV and historical trauma, specifically the focus on eradicating GBV through the healing of women of color survivors. Although participants’ stories may have motivated their career choice, the act of avoiding their own healing is costing them too much.

The study results suggest that leaders who do not receive personal healing support before holding a position in a GBV-based organization would benefit from leadership and organizational development within a healing justice framework. Additionally, the framework could inform organizational sustainability at multiple levels of an organization. Organizational leaders can also use the current study findings to gain insight into working with survivors and meeting their personal healing needs.

Organizations that want to integrate the healing justice framework as a tool to meet personal and organizational healing needs must acknowledge that survivors are at different stages of personal healing and have different experiences of GBV. It is also important to note that healing is not one size fits all. The facilitation of healing needs to be built into the organization in phases through building trust, accountability, and integrity, all of which facilitate the success of the integration. Furthermore, there is a myth that organizations are separate entities from the staff, the board, and the leadership. A difference exists between organizational trauma that is created by lack of funds, policies, or strategic direction and the organizational trauma that is created by organizational leadership and staff bringing the impact of their experience of trauma and GBV into the organizations they work in.

The study also revealed that no one sees women in leadership as victims or survivors of GBV; therefore, it is unfathomable to some that women of color who lead organizations are not only survivors but have been so impacted by GBV that it impacts how they function in leadership. For example, trauma responses in leadership are often mistaken for leadership weakness. Thus, these responses are only discovered in staff evaluations and are addresses as a leadership development issue deemed to be either a punishable or rewardable behavior. Some women of color leaders are instructed to complete leadership development trainings to address the behavior or told to go to therapy; however, this does not address the root cause of the behavior, which is a trauma response as a result of GBV.

7. Limitations

There are limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results in the study.

While the diversity among the sample was a strength of the study, more investigation across each characteristic is needed. For example, although the study focused on women of color, GBV is experienced across the gender spectrum and the definition of gender is changing dramatically. More men are disclosing survivor stories and the LGBTQ community is redefining gender while creating spaces for disclosing. Additionally, the focus of the interviews was on participants’ experience of GBV and its impact to their current position within organizations; however, further study would be beneficial across other institutions and across the spectrum of violence against women.

Limitations for women of color survivors in leadership also exist. With already limited resources, women of color survivors working in small grassroots organizations are already burnt out and may see healing as another task as opposed to an opportunity for organizational sustainability and leadership development, which oftentimes is not a priority against other organizational issues. To facilitate healing among leaders, funders must center healing justice in their grantmaking as a priority for organizational and personal development.

This may pose a challenge for future research of GBV within women of color survivors because leaders who exhibit trauma responses are often stigmatized and may not disclose. These women have to cope with the shame and discrimination following their disclosure of being survivors and victims of GBV in the organizational setting. Additionally, women of color who have experienced GBV may not identify as survivors or believe that they need healing, those who do and those who cannot take the risk of opening that dialogue within the organization will experience the strongest resistance to healing.

8. Conclusions and Personal Reflections

As an example of what it looks like to ground healing into social justice, I will conclude this paper the way I would begin and end any coaching, training, or workshop session: Setting the intention with a quote that reflects the healing work of the survivors and their resilient ancestral legacy. I invoke the spirit of liberation echoed by Audre Lorde (1984): “The true focus of revolutionary change is never merely the oppressive situations that we seek to escape but that piece of the oppressor which is planted deep within us” (p. 123).

This study was inspired by my experience of serving as an executive director in the South Bronx, New York City for over 15 years. However, more broadly, this study represents the depth and breadth of the impact of GBV on women of color survivors and the invisible, insidious ways GBV shapes women’s identity and leadership without her knowing, leaving both resiliency and scarcity in its path. I have watched some of my co-workers die thinking that they were going crazy without tools to take care of themselves along their journey of social service and justice. These observations fueled my passion to conduct this research and support women of color survivors working in the field of GBV. I aim to break through the shame and stigma attached to being leaders who are also survivors and thus require healing support.

Survivors are among us; they are our family members and co-workers. Have you ever wondered who is really sitting next to you at work, in the chair in front of you in your program, or in your organization? The reality is that survivors of GBV are all around us, they are leading the most important institutions and organizations in the world and it is our duty to create safe spaces of healing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Deep appreciation to all the women who so courageously offered their story and are leading a new world anyway and to survivors all over the world.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Beltrán, Ramona, and Stephanie Begun. 2014. It Is Medicine: Narratives of Healing from the Aotearoa Digital Storytelling as Indigenous Media Project (ADSIMP). Psychology and Developing Societies 26: 155–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Sandra L. 2010. Organizational stress as a barrier to trauma-informed service delivery. In Public Health Perspective of Women’s Mental Health. Edited by Marion Ann Becker and Bruce Lubotsky Levin. Cham: Springer, pp. 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart, Maria Yellow Horse. 1998. The return to the sacred path: Healing the historical trauma and historical unresolved grief response among the Lakota through a psychoeducational group intervention. Smith College Studies in Social Work 68: 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brave Heart, Maria Yellow Horse. 2000. Wakiksuyapi: Carrying the historical trauma of the Lakota. Tulane Studies in Social Welfare 21: 245–66. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Minority Health. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/ (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Chavez-Diaz, Mara, and Nicole Lee. 2015. A Conceptual Mapping of Healing Centered Youth Organizing: Building a Case for Healing Justice. Available online: https://urbanpeacemovement.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/HealingMapping_FINALVERSION.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, Donald G., and Randall R. Kropp. 2000. A review of domestic violence risk instruments, trauma violence abuse. Trauma, Violence & Abuse 1: 171–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edleson, Jeffrey L., Taryn Lindhorst, and Valli K. Kanuha. 2015. Ending Gender-Based Violence: A Grand Challenge for Social Work: Grand Challenges for Social Work Initiatives. Working Paper No. 15. Los Angeles: American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Gone, Joseph P. 2014. Reconsidering American Indian Historical Trauma: Lessons from an Early Gros Ventre War Narrative: Historical Trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry 51: 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorski, Paul, and Noura Erakat. 2019. Racism, whiteness, and burnout in antiracism movements: How white racial justice activists elevate burnout in racial justice activists of color in the United States. Ethnicities 19: 784–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, Sherry, Katie Schultz, and Jessica Elm. 2020. Understanding the Burden of Trauma and Victimization among American Indian and Alaska Native Elders: Historical Trauma as an Element of Poly-Victimization. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 21: 172–86. [Google Scholar]

- Holder, Melissa R. 2015. Exploring the Potential Relationship between Historical Trauma and Intimate Partner Violence among Indigenous Women; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Available online: https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/28074/Holder_ku_0099D_14287_DATA_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Incite. 2021. Dangerous Intersections. Women of Color Live in the Dangerous Intersections of Sexism, Racism, and Other Oppressions. Available online: http://www.incite-national.org/page/dangerous-intersections#sthash.tTEuhEjj.dpuf (accessed on 11 March 2019).

- Jeltsen, Melissa. 2017. Who Is Killing American Women? Their Husbands and Boyfriends, CDC Confirms. HuffPost. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/most-murders-of-american-women-involve-domestic-violence_us_5971fcf6e4b09e5f6cceba87?1e8 (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Kafle, Narayan P. 2011. Hermeneutic phenomenological research method simplified. Bohdi: An Interdisciplinary Journal 5: 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, Nancy. 2005. Embodiment: A conceptual glossary for epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59: 350–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorde, Audre. 1984. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh, Margaret-Anne. 2009. Trauma-Related Treatment Gains among Women with Histories of Interpersonal Violence and Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Abuse Disorder. Ph.D. thesis, University of South California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Maternal and Child Health Bureau. 2012. Women’s Health USA. Available online: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/whusa12/pc/pages/usp.html (accessed on 10 June 2018).

- Muid, Onaje. 2006. “…Then I found my spirit:” The meaning of the United Nations world conference against racism and the challenges of the historical trauma movement with research considerations. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health 4: 30–64. [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition against Domestic Violence (NCADV). 2020. Statistics. Available online: http://ncadv.org/learn-more/statistics (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Petrosky, Emiko, Janet M. Blair, Carter J. Betz, Katherine A. Fowler, Shane P. D. Jack, and Bridget H. Lyons. 2017. Racial and ethnic differences in homicides of adult women and the role of intimate partner violenc—United States, 2003–2014. MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66: 741–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network. 2020. Scope of the Problem: Statistics. Available online: https://www.rainn.org/get-information/statistics/frequency-of-sexual-assault (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Robertson, Brian J. 2015. Holacracy: The New Management System for a Rapidly Changing World. New York: Henry Holt and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Slattery, Suzanne M., and Lisa A. Goodman. 2009. Secondary traumatic stress among domestic violence advocates: Workplace risk and protective factors. Violence against Women 15: 1358–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprechman, Sofia, Kathleen Christie, and Marcia Walker. 2014. Challenging gender-based violence worldwide: Care’s program evidence, strategies, results, and impacts of evaluations 2011–2013. Care. Available online: https://care.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Challenging-GBV-Worldwide-CARE_s-program-evidence.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Stark, Lindsay. 2006. Cleansing the wounds of war: An examination of traditional healing, psychosocial health, and reintegration in Sierra Leone. Intervention 4: 206–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Jane E. 2017. Addiction doc says: It’s not the drugs. It’s the aces-adverse childhood experiences. Aces Too High. Available online: https://acestoohigh.com/2017/05/02/addiction-doc-says-stop-chasing-the-drug-focus-on-aces-people-can-recover/ (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- The National Domestic Violence Hotline (NDVH). 2020. Domestic violence statistics. Available online: http://ncadv.org/learn-more/statistics (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Tsirigotis, Konstantinos, and Joanna Luczak. 2015. Emotional intelligence of women who experience domestic violence. The Psychiatric Quarterly 87: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. 2020. Sustainable Development Goals. “Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Van Manen, M. 1997. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. London: The Althouse Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Karina L., Selina A. Mohammed, Teresa Evans-Campbell, Ramona E. Beltran, David H. Chae, and Bonnie Duran. 2011. Bodies don’t just tell stories, they tell histories: Embodiment of historical trauma among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Du Bois Review 8: 179–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wathen, Nadine, Jennifer C. D. MacGregor, and Barbara J. MacQuarrie. 2015. The impact of domestic violence in the workplace. Results from a pan-Canadian survey. American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 57: 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Women of Color Network. 2006. Women of Color Network Facts & Stats: Domestic Violence in Communities of Color. Available online: http://www.doj.state.or.us/wpcontent/uploads/2017/08/women_of_color_network_facts_domestic_violence_2006.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Zamir, Osnat, and Yoav Lavee. 2015. Emotional awareness and breaking the cycle of re-victimization. Journal of Family Violence 30: 675–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Kristen, Neelam Pathikonda, Brenda Salgado, and Taj James. 2010. Out of the Spiritual Closet: Organizers Transforming the Practice of Social Justice. Oakland: Movement Strategy Center. Available online: https://movementstrategy.org/b/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/MSC-Out_of_the_Spiritual_Closet.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).