The Historical Trauma and Resilience of Individuals of Mexican Ancestry in the United States: A Scoping Literature Review and Emerging Conceptual Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose

1.2. Contribution of This Review & Overview of the Selected Literature

1.3. Population Demographics

1.4. IMA-US: Shared and Differential Social Experiences

1.4.1. IMA-US: Within Group Differences

1.4.2. Shared Experiences and the Broad Spectrum of Mestizaje

1.5. Prior Research: A Decontextualized Perspective

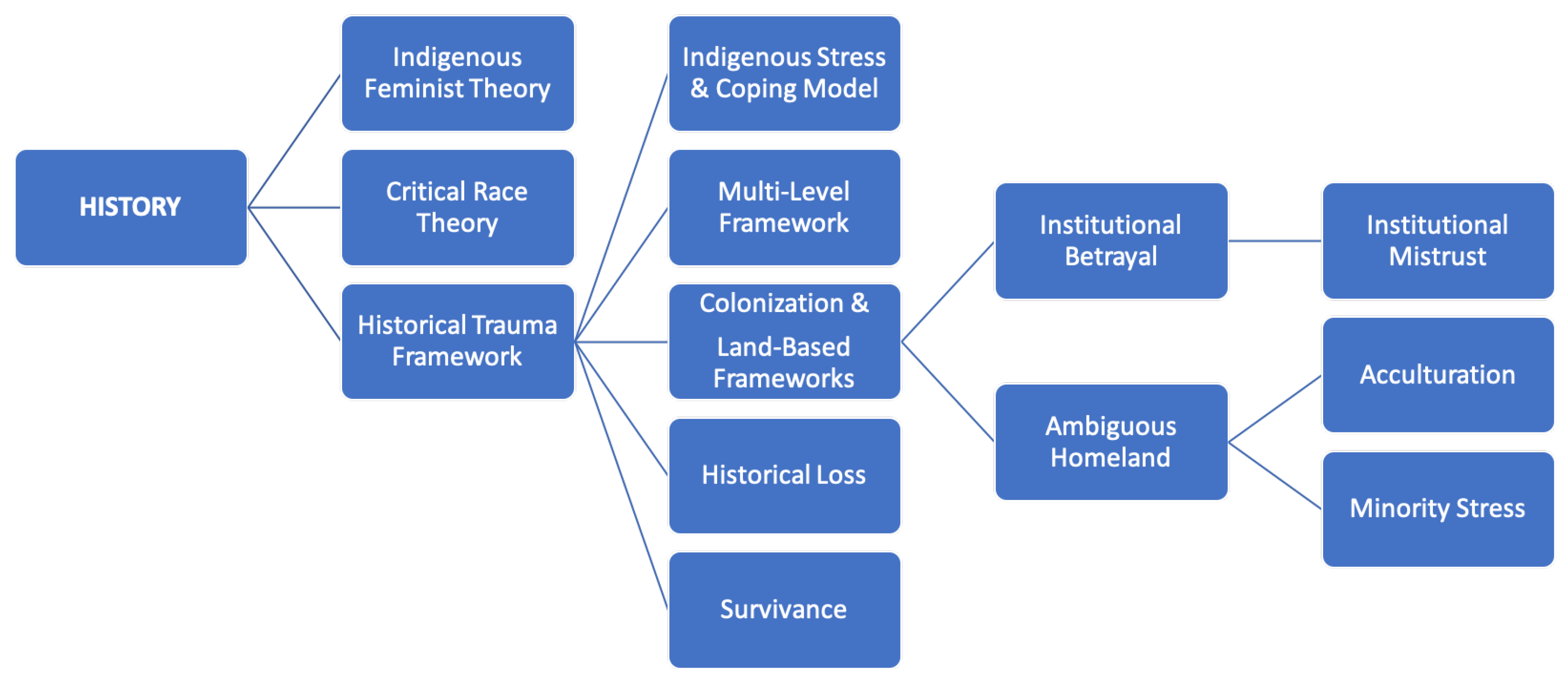

2. Conceptual Framework: A Contextualized Perspective

2.1. Historical Perspective

2.2. Historical Trauma Framework

2.2.1. Historical Trauma Concept, HTEs, and Adaptive Responses

2.2.2. Inter-Generational Transmission of Trauma

2.2.3. Colonial Trauma Response

2.2.4. Resistance through Collective Strength

2.3. Application of Conceptual Framework to the Lived Experiences of IMA-US

2.3.1. Understanding the Social Context: Health Vulnerabilities

2.3.2. Understanding Political Context: Social Vulnerabilities

2.3.3. Health Advantages: Community Resources and Collective Strength

2.3.4. Mexican Values and Philosophies

2.3.5. Mobilization for Social Change: Legacy of Resistance and Self-Determination

2.3.6. Historical Trauma Framework

2.4. Colonial Trauma Responses

Limitations in Using Historical Trauma Framework on IMA-US

3. Methods

3.1. Philosophical Framework

3.1.1. Interdisciplinary Approach

3.1.2. Reflexivity Statement

3.2. Scoping Review Methodological Framework

Contextual Literature: Complementary Narrative Reviews

3.3. Thematic Analysis

3.4. Discourse Analysis

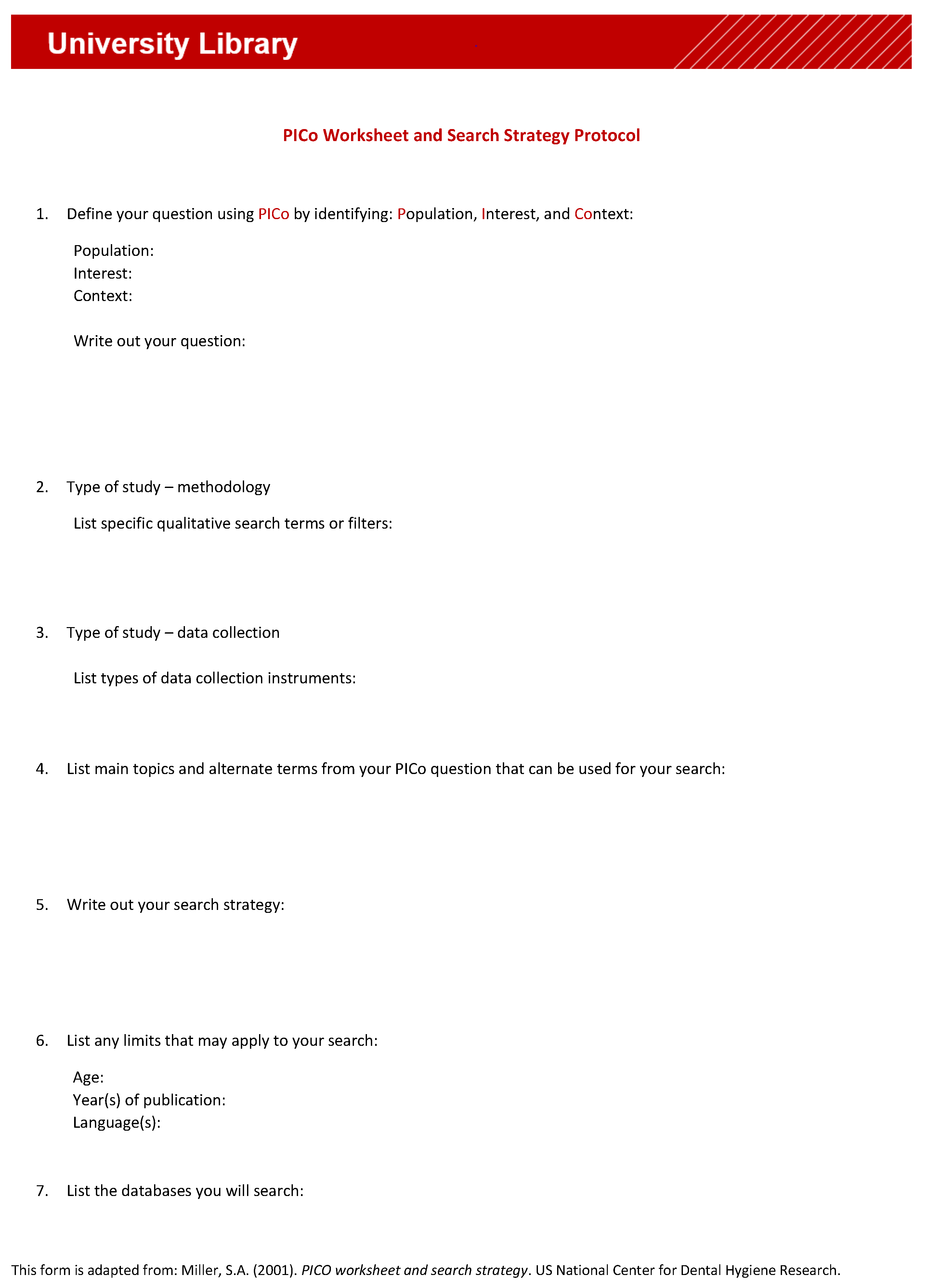

3.5. The PICo Framework

3.6. Search Strategy

3.7. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

- Population. Eligible sources included or mentioned Mexican and/or Mexican Indigenous in the sample population, or a discussion about this population was included in the body of the paper.

- Topic of Study. Eligible sources discussed behavioral health issues (i.e., depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, other mood and adjustment disorders).

- Context. Eligible sources had to discuss the behavioral health of IMA-US in the context of HTEs or a historical trauma and/or related frameworks (as seen in Table 2).

- Peer-Reviewed these selected studies were peer-reviewed, written in English and published from 2008 through 2018.

- Exceptions to inclusion criteria of publication period were adjusted for some sources because the work was either a seminal paper that was highly cited across the selected sources (Anzaldúa et al. 2003), or because other studies in the same series of papers by an author were included in the selected sources (Zentella 2004). The criteria for inclusion of IMA-US was slightly modified for a few studies, because even though these sources did not explicitly mention inclusion of IMA-US in the sample, their presence was implied in the body of the paper (Brave Heart et al. 2011; Cromer et al. 2018; Grayshield et al. 2015; Mohatt et al. 2014; Whitbeck et al. 2004); for example, these studies indicated that the geographical location in which the study took place is highly populated by IMA-US, such studies mentioned the inclusion of unaffiliated indigenous tribes, which are often Mexican communities. In one study, a co-author identified as an IMA-US, and included a positionality statement regarding her heritage (Grayshield et al. 2015) as motivation for the study (see bottom of Table 1).

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Selected Sources

4.2. Theoretical Characteristics

4.3. Thematic Summary

4.4. Historical Traumatic Events and Impacts

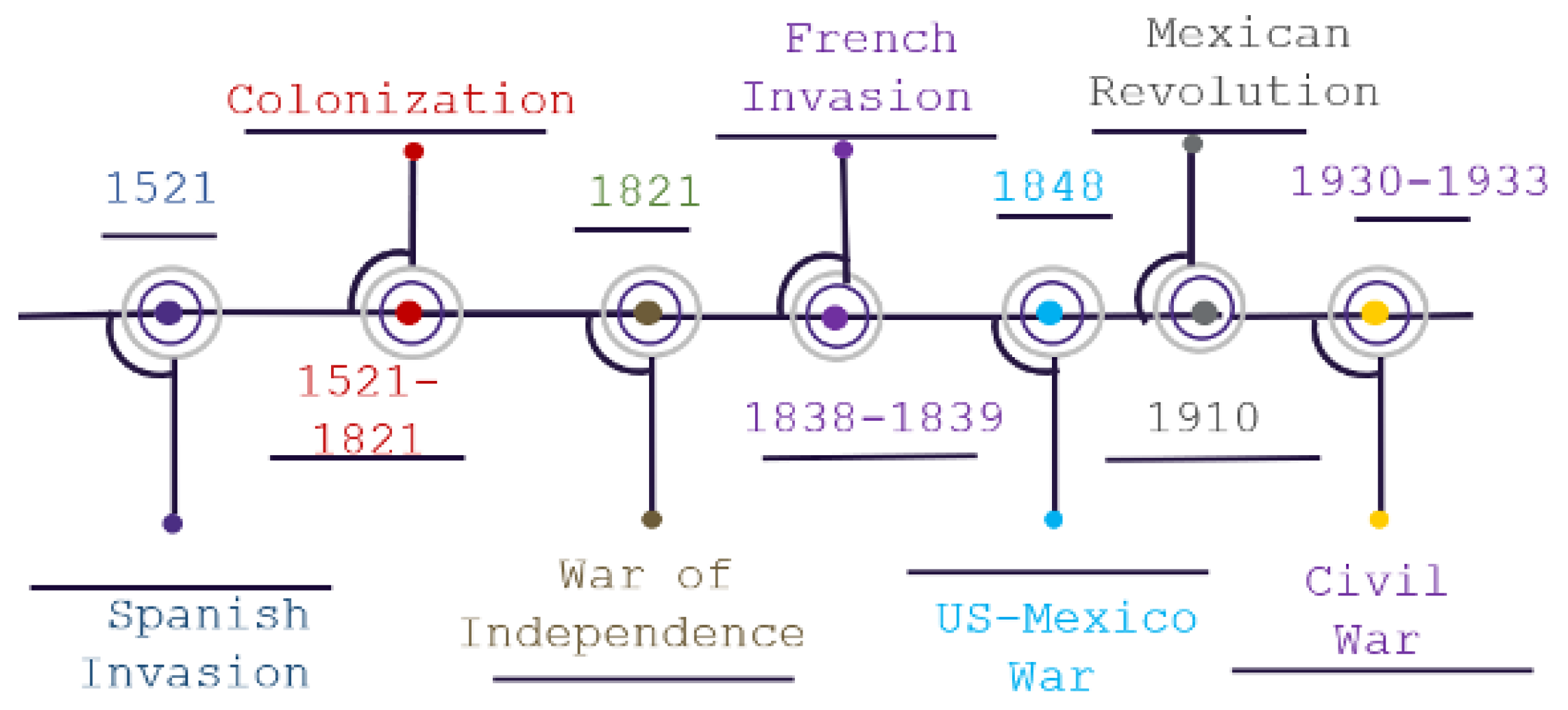

- The invasion and colonisation of pre-colonial México (1519–1521)The first major chapter of adversity for Mexican people started with the Spanish invasion (1519–1521). This period was characterized by their decimation, forced slavery, and the destruction of their cultural legacy, including writings, architecture, and artifacts (De la Peña 2006; Zentella 2009). This epistemicide also involved the suppression of mother tongues, culture, Indigenous identity, and wellness traditions. This invasion was followed by the colonial period, which lasted over 300 years, resulting in new mixed races, namely the Spanish-Indigenous, among many others (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Hoskins and Padrón 2017; Zentella 2014).

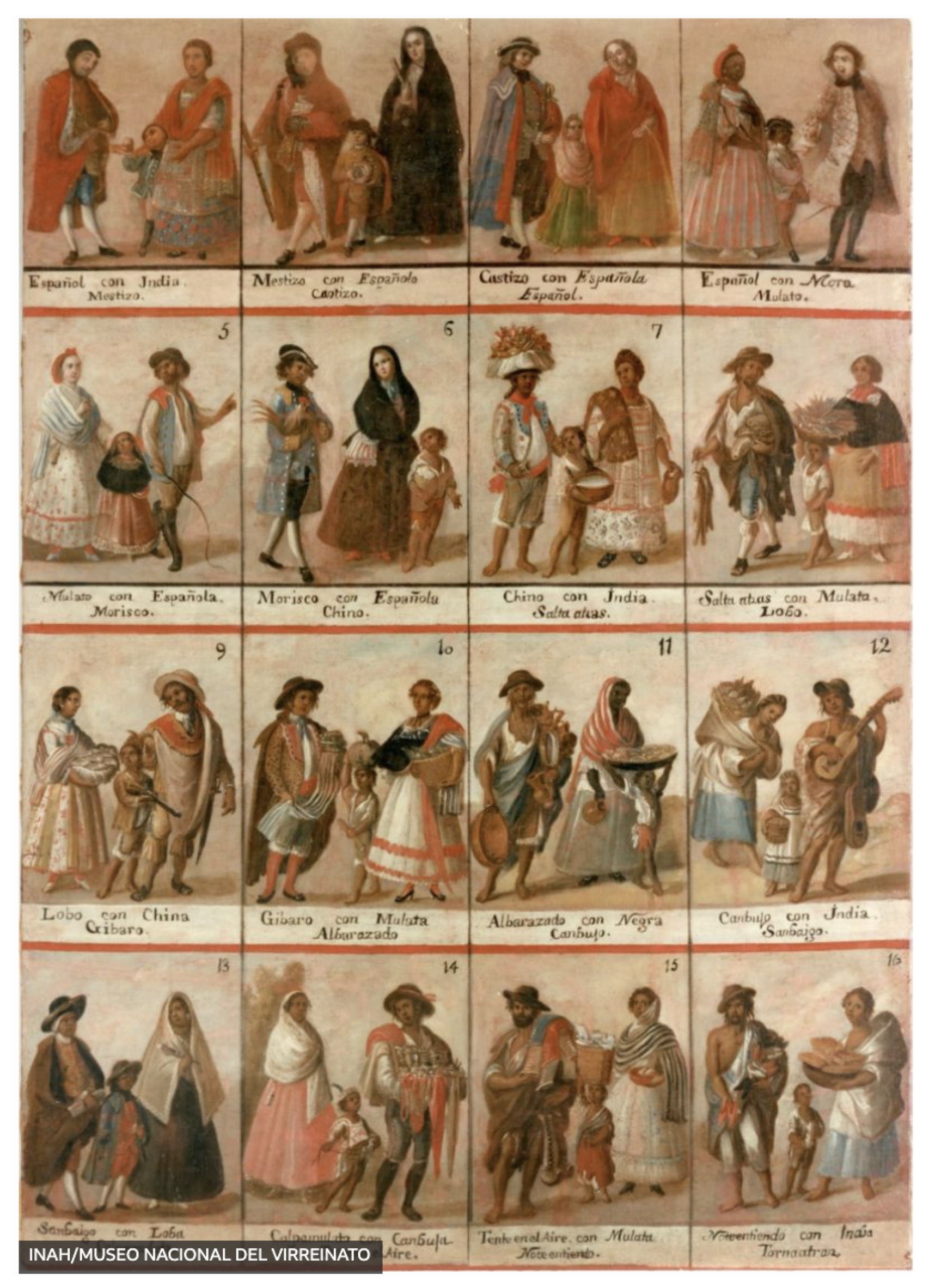

- The colonization (1521–1821)After the invasion, the process of forced slavery ensued with the surviving indigenous peoples and the new racially mixed groups (e.g., Criollo, Mestizo, Castizo, Mulato) (see Appendix B Figure A2). These groups were forced to assimilate into Spanish culture, religion, and values; a process that promoted the erasure of their own indigenous heritage and identities (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; De la Peña 2006; Leon-Portilla 2011; Talebreza-May 2015; Zentella 2014). The erasure of indigenous ways of being and knowing (Smith 1999) did not end with the war of independence from Spain (1821) (De la Peña 2006). This process lasted thorough the colonial period and still prevails today. When México became a republic, the public educational system promoted the idea that the indigenous people had been largely eliminated during the Spanish invasion (Churchill 2000; Gutiérrez 2015). Even though Mexican Indigenous communities have made great advances to re-affirm their presence with the movement titled “estamos vivos/we are alive” (Morales 1989), much work still needs to be done to protect their rights, and validate their legacy and ways of knowing.

- The US-Mexican war (1846–1848)Another chapter in their lifetime trauma is described in the works that discuss the appropriation of the Mexican territory by the U. S. (see Appendix C Figure A3). This territorial transaction recorded in the Treaty of Guadalupe (Estrada 2009; Talebreza-May 2015) led to many historical losses for Mexican and Indigenous communities: the loss of land, original identities, language, cultural knowledge, and family relationships, and brought about forced assimilation, and marginalization (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Zentella 2009). Historical records report that the original inhabitants of the present-day U.S. Southwest were allowed to either keep their land and become U.S. citizens, or to relocate to Mexico across the the new border between the two countries (Massey and Denton 1993). The majority of Mexican nationals stayed in their residences and were granted U.S. citizenship, but their new citizenship was of a nominal nature, and property rights were violated for many, which led to the loss of their land and cultural resources (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Estrada 2009; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Talebreza-May 2015; Zentella 2004). Although the U.S. government promised to safeguard the property rights, language, and culture of the displaced communities, it did not uphold this part of the treaty (Estrada 2009).During this this period, the cultural identities of the original inhabitants from the appropriated territory were fractured once again. Now the imposed identity was not indigenous versus Spaniard, or mestizo versus criollo, but Hispanic versus Chicano/Mexican-American. Even though these fractures to the collective identity have further suppressed their origin stories (Anzaldúa et al. 2003), throughout history, many of Mexican Indigenous communities have resisted assimilation. They have fought to retain their native identities and culture, often resorting to syncreticism. Syncreticism is the process of blending cultural practices from various traditions to ensure the continuity and transfer of knowledge (Cromer et al. 2018; Grayshield et al. 2015; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Talebreza-May 2015). As result, current cultural traditions may resemble a fusion of elements taken from American Indians, Mexican immigrants, Spaniards, and Anglo Americans (Talebreza-May 2015).

- Post–US-México War Era/ California Gold Rush.The California Gold Rush is the saddest chapter in the history of adversity for Mexican descendants of the original inhabitants of present day Southwest (Ramirez and Hammack 2014). The California Indians endured colonial violence three times. First by Spain, then by the postcolonial government of México, and later by the U. S. (Estrada 2009; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Talebreza-May 2015). When México lost roughly half of its territory to the United States, many of the native communities that had been already displaced and colonized by Spain faced a new wave of displacement and forced assimilation (Estrada 2009; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Talebreza-May 2015). This time, they were forced to mirror the values and culture of the Anglo population (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Talebreza-May 2015; Zentella 2009). They were persecuted and almost exterminated by brutal forms. However, elders in that community have preserved and transmitted narratives of survivance to younger generations, these inter-generational transmissions that have strengthen the Indigenous and resilient identity (Ramirez and Hammack 2014).

4.5. Mechanisms of Transmission of Historical Trauma for IMA-US

- Popular CultureExamples of transmission of both historical trauma and intergenerational resilience are readily evident in popular culture, such as art, dance, and music Zentella (2004, 2009, 2014). Episodes from the Spanish invasion, colonization, and wars have been depicted in the muralismo movement. Muralismo is an artistic expression that typically depicts historical struggles as well as the resistance from Mestizo/Mexican and Indigenous groups Zentella (2004, 2009, 2014). This art movement originated before the Mexican Revolution (1910), and included prominent Mexican painters such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco (Folgarait et al. 1998). Much of the work depicts the struggles of indigenous groups; and some work also addresses the pain associated with the traumatic origin of the Mexican people, the offspring of both aggressor and survivor (Anzaldúa et al. 2003). Additionally, this genre has also depicted a variety of social rights movements (Zentella 2004).

- Collective Strength and Social MovementsAn extensive list of social movements carried out by IMA-US has been provided in Section 2.3.3. The movements cited in this literature included those led by Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez Zentella (2004, 2009, 2014). These activists opened up spaces to promote policy changes and raise awareness to the occupational injustices suffered by farm workers, a group composed mainly of mixed and non-mixed Indigenous Mexican families (Estrada 2009; Zentella 2004); however this group have also include people from other countries, such as Jamaica, the Philippines, Guatemala, Honduras (Johnson 1999; La Torre 2016). Additional sources capturing elements of the collective strength exhibited by this binational population includes local newsletters and newspapers. These include accounts of historical and contemporary oppression, as well as narratives of resistance and self-determination. Similar their stories have also been immortalized in the corridos Mexicanos. These are ballads that herald the actions of heroes/heroines who valiantly outwit the enemy, and the lyrics emphasize the resilient and humorous spirit of the Mexican people (Zentella 2004). The tradition of the corridos dates back several hundred years. This musical genre is mainly concerned with narrating traumatic events that affected large communities or groups by outsider agents (e.g., conquest/colonization, appropriation of Mexican territory, and struggles with border patrol) (Zentella 2004).

- Family Systems/ParentingStevens et al. (2015) builds on the literature that examines the transmission of historical trauma through parenting (Evans-Campbell 2008; Prussing 2014). Prior research has predominantly discussed links between intergenerational transmission of trauma and substance use problems (Corvo and Carpenter 2000; Evans-Campbell 2008; Walters and Simoni 2002). However, the authors cited here also discuss how parenting practices can convey to their offspring their sense of self-worth, mental health patterns, and behaviors. When the parents have been affected, directly or indirectly, by experiences resulted from traumatic events, such as child removal (Carvajal and Young 2009; Hanna et al. 2017; Stevens et al. 2015), land displacement (Estrada 2009; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Talebreza-May 2015; Zentella 2004), and suppression of their native language, cultural beliefs and values (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Brave Heart et al. 2011; Cromer et al. 2018; Estrada 2009).According to the literature cited here, the impacts from these events, as well as the impacts and lessons during this era have been transmitted across generations; however, the stories associated with these transmissions have not always been transmitted. The disconnect in the stories shared between those affected communities and younger generations has been linked to psychological distress in current generations, which is harder to treat because these symptoms include an unidentified etiology. However, these family-level transmissions in research with related populations, have been discussed in terms of unresolved and disenfranchised grief disorders (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Perez and Arnold-Berkovits 2018; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Stevens et al. 2015; Talebreza-May 2015; Zentella 2014). The most recent chapter of adversity for IMA-US includes traumatic experiences due to forced family separation (Hondagneu-Sotelo and Avila 1997; Wells 2017), immigration related detention (Brabeck and Xu 2010), and deportation (Silver 2014). These disruptions in the parent-child relationship have been associated with a number of mental and behavioral health problems including depressive symptoms, health problems, decreased sense of wellness, guilt, anger and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (Carvajal and Young 2009; Hanna et al. 2017; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Stevens et al. 2015). These negative impacts are complex and not well understood, although the dynamics of powerlessness, self-worth, health problems, and substance use have been noted in the literature (Evans-Campbell 2008; Prussing 2014; Stevens et al. 2015). Less attention has been given to the review of positive cultural exchanges are disrupted when the bond between families is lost. This link is worth investigating because the impact does not only extend to parents and their offspring, but also to the parenting practices passed down across generations (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Evans-Campbell 2008; Yehuda et al. 2001).

4.6. Responses to Historical Trauma Events and Narratives for IMA-US

- Mistrust in Social Welfare AgenciesMistrust in governmental institutions was linked to both risk and protective health factors. In general, avoidance of services provided by social welfare agencies can lead to worsening health and unfulfilled social needs. However, when these services include a negative bias towards some population, this avoidance behavior may also serve as a protective factor (Estrada 2009; Talebreza-May 2015). Similarly to the way in which IMA-US are known to seek community and family bonds to enhance their well-being, they have also avoided contact with governmental welfare institutions to prevent harm (Carvajal and Young 2009; Estrada 2009; Hanna et al. 2017; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Stevens et al. 2015). Several sources outlined a history of mistreatment towards IMA-US by social agencies and the medical industry (Estrada 2009; Ramirez and Hammack 2014; Talebreza-May 2015; Zentella 2004). This mistreatment was portrayed as disenfranchisement of basic human and property rights (Estrada 2009; Zentella 2014), inadequate health care services (Carvajal and Young 2009; Stevens et al. 2015; Talebreza-May 2015), and epistemological violence (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Cromer et al. 2018; Grayshield et al. 2015). Whereas these sources did not present compelling empirical evidence to sustain these claims, other research has shown that when conditions of inequality and injustice are embedded in welfare institutions, the delivery of services become iatrogenic, worsening health outcomes for the affected populations (Battiste 2011; Suleman et al. 2018).

- Mental Health Issues and SUDsIn general, historical trauma research has discussed the impacts of historical trauma events on mental health and substance use for AIAN, however, this work is still developing. Empirical research addressing this topic for IMA-US is almost non-existent. As whole, the sources cited here do not present a coherent coverage on this subject. A few sources report behavioral health issues affecting IMA-US. When these findings were compared with supplementary literature, it was noted that prevalence rates between IMA-US and AIAN are similar. These complementary works also revealed a frequent theme: the uneven distribution of disease within IMA-US. The most marked differences were found between those born in the United States vs. foreign born. Similar patterns of difference were also identified between indigenous people of Mexican descent and their counterparts. Several studies found that indigenous people exhibit higher prevalence of behavioral health problems. The pronounced behavioral health issues for indigenous Mexican people is not surprising given that historically these groups have faced significantly greater barriers to public health programs compared with the mainstream population and other racial and ethnic groups (Fernandez 2019; Wallace and Castañeda 2010).The average lifetime prevalence of any psychiatric or substance abuse disorder for individuals of Mexican descent was estimated at 36.7%. The prevalence rate for those born in the US was higher, with an estimated rate of 47.6%, compared to 28.5% for those born in México (Grant et al. 2004). Similarly, the prevalence of anxiety disorders was estimated at 16.3% for the US-born group, while the foreign-born reported a prevalence of 9.1% (Grant et al. 2004). The average prevalence rate of alcohol use disorders across U.S. and Mexican born groups was estimated at 21.9%. The prevalence for those born in the US was estimated at 30.5% and for the Mexican foreign-born population, this rate was reported at 15.3% (Grant et al. 2004). This pattern of increased vulnerability for US-born people of Mexican descent is also observed in the lifetime prevalence of any drug use disorders: the rate for people of Mexican descent born in the US was estimated at 12.0%, while for foreign-born individuals the rate was estimated at 1.7%, with an average rate across groups of 6.1% (Grant et al. 2004). Prior studies have reported similar findings in the Mexican population living in the US (Kessler et al. 2006). Research conducted in México yielded similar findings, with Mexican-born individuals reporting only half of the mental disorders reported by US-born people of Mexican descent (Breslau et al. 2007) Several studies report that the prevalence of alcohol and substance abuse disorders for Mexican migrant workers is higher for indigenous workers (9.9%) than non-Indigenous workers (6.2%) (Catalano et al. 2000; Fernandez 2019; Zúñiga et al. 2014). Complementary studies examining the health of migrant populations report similar findings in the patterns of substance use among Mexican migrants (Borges et al. 2016; Fernandez 2019; Zhang et al. 2015).

4.7. Recommendations for Healing Historical Trauma

- Reconstructing Narratives of SurvivalRecent Indigenous scholarship highlights the importance of recreating narrative from traumatic historical events to disrupt the transmission of intergenerational trauma in Indigenous populations (Beltrán and Begun 2014; Evans-Campbell et al. 2006; Ortega-Williams et al. 2021). By recreating these stories, an opportunity arises to highlight the resources, allies, and resilience responses involved when confronting these stressful conditions (Cohen et al. 2012; White 1998). The sources cited here illustrate how the process of creating and sharing narratives of trauma and survival can be an effective way to elicit and appreciate adaptive responses (Cromer et al. 2018; Grayshield et al. 2015; Ramirez and Hammack 2014).These works indicate that art, storytelling, and oral tradition are all ways in which IMA-US have preserved and transmitted these narratives. These narratives recount their history of adversity and collective strength, as well as vehicles of recovery from the effects of HTEs, with emphasis on traditional medicine and kinship (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Grayshield et al. 2015; Hoskins and Padrón 2017). These cultural vehicles also have been used to retrace origin stories (Anzaldúa et al. 2003), and to reclaim indigenous identities and knowledge (Ramirez and Hammack 2014). The reviewed body of literature, and indeed this review itself, can also be seen as a contribution to this narrative. By tracing our own origin and synthesising traditional knowledge we are creating a new understandings about how our past has influenced our present (Pereyra 1980); especially the dynamics of health exchanges between IMA-US and social and healthcare organizations (Estrada 2009).

- Community Engagement in the Development of Resilience-based InterventionsThe recommendations for healing from historical trauma include the importance of partnership with affected communities. Prior research has shown that community engagement in research process yields more comprehensive and sustainable interventions (Wallerstein and Duran 2010). These sources recommend engaging key stakeholders (i.e., parents, grandparents, local leaders) in the development of resilience-based interventions for younger generations (Cromer et al. 2018; Grayshield et al. 2015; Ramirez and Hammack 2014). Customarily, elders have played a vital role in the preservation and dissemination of cultural practices, including indigenous knowledge and traditions (Cromer et al. 2018; Grayshield et al. 2015; Ramirez and Hammack 2014). They also have played a role in the socialization of younger generations, particularly in nurturing intergenerational connections and fostering healing. These wellness, spiritual and traditional values and practices, have been disseminated through oral tradition. Findings from a small qualitative study conducted by Ramirez and Hammack (2014) suggest that the connection between the grandmothers and the youth was critical in the preservation of Indigenous identity.The cited sources argue that elders possess a rich memory of the strengths and coping skills that have been crafted for many generations to deal with colonial oppression (Cromer et al. 2018; Grayshield et al. 2015; Ramirez and Hammack 2014). The authors hold that implementing engagement strategies rooted in the history, traditional beliefs, and health practices may result in higher retention rates in healthcare services, because these practices have a greater chance to be adopted by the users, since these have been embraced by these communities for many generations (Cromer et al. 2018; Grayshield et al. 2015; Ramirez and Hammack 2014).

- Designing Therapeutic Spaces to Heal from Historical TraumaAnother recommendation to recover from the consequences of historical trauma is through engagement of these communities in culturally appropriate treatment settings and modalities. Talebreza-May (2015) emphasized the need to design sanctuary spaces that are free from artifacts and behaviors resembling colonial ideology. Examples of elements that can foster safe spaces include the use of language, images, and concepts resembling the sentiments of the population for any significant historical events or milestones relevant to the target population. Most importantly, these therapeutic spaces must be created engaging expert knowledge on the historical experiences of the target population Hanna et al. (2017); Talebreza-May (2015); Zentella (2014).

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations of This Review

5.2. Conclusions

5.3. Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. PICo Framework for Qualitative Studies, Adapted by Murdoch University

Appendix B. The PostColonial Caste System

Appendix C. Map of the Mexican Territory’s Cessation to the United States

References

- Aguilar, Mauricio Domínguez, Federico Dickinson Bannack, and Ana García de Fuentes. 2013. Climate Change and Water Access Vulnerability in the Human Settlement Systems of Mexico: The Merida Metropolitan Area, Yucatan. Realidad, Datos y Espacio Revista Internacional de Estadística y Geografía 4: 14–41. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón, Renato D., Amrita Parekh, Milton L. Wainberg, Cristiane S. Duarte, Ricardo Araya, and María A. Oquendo. 2016. Hispanic immigrants in the USA: Social and mental health perspectives. The Lancet Psychiatry 3: 860–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertani, Claudio. 1999. Los pueblos Indígenas y la ciudad de México. una aproximación. Política y Cultura 12: 195–221. [Google Scholar]

- Alegría, Margarita, Norah Mulvaney-Day, Maria Torres, Antonio Polo, Zhun Cao, and Glorisa Canino. 2007. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 97: 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegría, Margarita, and Meghan Woo. 2009. Conceptual Issues in Latino Mental Health. Los Angeles and Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Josefina, Bradley D. Olson, Leonard A. Jason, Margaret I. Davis, and Joseph R. Ferrari. 2004. Heterogeneity Among Latinas and Latinos entering substance abuse treatment: Findings from a National Database. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 26: 277–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antebi, Susan. 2008. A Tiger in the Tank: A Literary Genetics of the Mexican Axolotl. Latin American Literary Review 36: 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, Gloria E., Simon J. Ortiz, Inéz Hernández-Avila, and Domino Perez. 2003. Speaking across the divide. Studies in American Indian Literatures 15: 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhardt, Ray. 2005. Indigenous knowledge systems and alaska native ways of knowing. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 36: 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Barocas, Harvey A., and Carol B. Barocas. 1979. Wounds of the fathers: The next generation of holocaust victims. International Review of Psycho-Analysis 6: 331–40. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, Irán, and Denise Longoria. 2018. Examining cultural mental health care barriers among Latinos. CLEARvoz Journal 4: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Battiste, Marie. 2011. Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, Ramona, Antonia R. G. Alvarez, Angela R. Fernandez, Xochilt Alamillo, and Lisa Colón. 2021. Salud, cultura, tradición: Findings from an Alcohol and other drug and HIV needs assessment in Urban “Mexican American Indian” communities. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work 30: 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, Ramona, and Stephanie Begun. 2014. ‘It is medicine’ narratives of healing from the aotearoa digital storytelling as indigenous media project (adsimp). Psychology and Developing Societies 26: 155–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfil Batalla, Guillermo. 2020. México Profundo: Una Civilización Negada. Tlalpan: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, Guilherme, Cheryl J. Cherpitel, Ricardo Orozco, Sarah E. Zemore, Lynn Wallisch, Maria-Elena Medina-Mora, and Joshua Breslau. 2016. Substance use and cumulative exposure to American society: Findings from both sides of the US–México border region. American Journal of Public Health 106: 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borjas, George J., and Lawrence F. Katz. 2007. The evolution of the Mexican-born workforce in the United States. In Mexican Immigration to the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 13–56. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell, Luisa N., and Elizabeth A. Lancet. 2012. Race/ethnicity and all-cause mortality in US adults: Revisiting the Hispanic paradox. American Journal of Public Health 102: 836–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabeck, Kalina, and Qingwen Xu. 2010. The impact of detention and deportation on latino immigrant children and families: A quantitative exploration. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 32: 341–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, Stanley. 1998. The day of the dead, halloween, and the quest for mexican national identity. Journal of American Folklore 111: 359–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brave Heart, Maria Yellow Horse. 1998. The return to the sacred path: Healing the historical trauma and historical unresolved grief response among the Lakota through a psychoeducational group intervention. Smith College Studies in Social Work 68: 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brave Heart, Maria Yellow Horse, Josephine Chase, Jennifer Elkins, and Deborah B. Altschul. 2011. Historical trauma among Indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 43: 282–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslau, Joshua, Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, Guilherme Borges, Ruby Cecilia Castilla-Puentes, Kenneth S. Kendler, Maria-Elena Medina-Mora, Maxwell Su, and Ronald C. Kessler. 2007. Mental disorders among english-speaking mexican immigrants to the us compared to a national sample of mexicans. Psychiatry Research 151: 115–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broda, Johanna. 2003. La ritualidad mesoamericana y los procesos de sincretismo y reelaboración simbólica después de la conquista. Graffylia 2: 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, Christina. 2015. Indigenismo. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Hoyos, Ramiro, Alberto Villasenor-Sierra, Rebeca Millán-Guerrero, Benjamín Trujillo-Hernández, and Joel Monárrez-Espino. 2013. Sexual risk behavior and type of sexual partners in transnational indigenous migrant workers. AIDS and Behavior 17: 1895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabassa, Leopoldo J., Roberto Lewis-Fernández, Shuai Wang, and Carlos Blanco. 2017. Cardiovascular disease and psychiatric disorders among Latinos in the United States. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 52: 837–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacari-Stone, Lisa, and Magdalena Avila. 2012. Rethinking research ethics for latinos: The policy paradox of health reform and the role of social justice. Ethics & Behavior 22: 445–60. [Google Scholar]

- Caminero-Santangelo, Marta. 2004. “Jasón’s indian”: Mexican americans and the denial of indigenous ethnicity in anaya’s bless me, ultima. Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 45: 115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, Scott C., and Robert S. Young. 2009. Culturally based substance abuse treatment for american indians/alaska natives and latinos. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse 8: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Castro, Felipe González, Julie Garfinkle, Diana Naranjo, Maria Rollins, Judith S. Brook, and David W. Brook. 2007. Cultural traditions as “protective factors” among latino children of illicit drug users. Substance Use & Misuse 42: 621–42. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, Ralph, Ethel Aldrete, William Vega, Bohdan Kolody, and Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola. 2000. Job loss and major depression among Mexican Americans. Social Science Quarterly 81: 477–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Lori A., Randy Jackson, Catherine Worthington, Ciann L. Wilson, Wangari Tharao, Nicole R. Greenspan, Renee Masching, Valérie Pierre-Pierre, Tola Mbulaheni, Marni Amirault, and et al. 2018. Decolonizing scoping review methodologies for literature with, for, and by Indigenous peoples and the African diaspora: Dialoguing with the tensions. Qualitative Health Research 28: 175–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Sucheng. 2000. A people of exceptional character: Ethnic diversity, nativism, and racism in the California gold rush. California History 79: 44–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, Javier Gámez. 2015. Yaquis y magonistas: Una alianza indígena y popular en la revolución mexicana. La Pacarina del Sur 3: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, Freda K., and Lonnie R. Snowden. 1990. Community mental health and ethnic minority populations. Community Mental Health Journal 26: 277–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, Nancy E. 2000. Erasing popular history: State Discourse of Cultural Patrimony in Puebla, Mexico. Paper presented at XXII International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association, Miami, FL, USA, March 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Victoria, Virginia Braun, and Nikki Hayfield. 2015. Thematic analysis. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 222–48. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, Amanda, and Paul Atkinson. 1996. Making Sense of Qualitative Data: Complementary Research Strategies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Judith A., Anthony P. Mannarino, Matthew Kliethermes, and Laura A. Murray. 2012. Trauma-focused cbt for youth with complex trauma. Child Abuse & Neglect 36: 528–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Chen, Smadar, and Martijn Van Zomeren. 2018. Yes we can? group efficacy beliefs predict collective action, but only when hope is high. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 77: 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, Diana, and Francisco Delgado. 2005. Si, Se Puede!/Yes, We Can! El Paso: Cinco Puntos Press. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Diaz, Lillian. 2001. Hispanics, Latinos, or Americanos: The evolution of identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 7: 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, Josh. 2013. Inoculation theory. In The Sage Handbook of Persuasion: Developments in Theory and Practice. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Inc., vol. 2, pp. 220–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cortázar, Julio. 2015. Axolotl. Stockholm: Modernista. [Google Scholar]

- Corvo, Kenneth, and Elizabeth H. Carpenter. 2000. Effects of parental substance abuse on current levels of domestic violence: A possible elaboration of intergenerational transmission processes. Journal of Family Violence 15: 123–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. 2017. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cromer, Lisa Demarni, Mary E. Gray, Ludivina Vasquez, and Jennifer J. Freyd. 2018. The Relationship of Acculturation to Historical Loss Awareness, Institutional Betrayal, and the Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma in the American Indian Experience. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 49: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, Laura J., David C. Aron, Rosalind E. Keith, Susan R. Kirsh, Jeffery A. Alexander, and Julie C. Lowery. 2009. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science 4: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Peña, Guillermo. 2002. La educación indígena. Consideraciones críticas. Sinéctica, Revista Electrónica de Educación 20: 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- De la Peña, Guillermo. 2006. A new Mexican nationalism? Indigenous rights, constitutional reform and the conflicting meanings of multiculturalism. Nations and Nationalism 12: 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Santos, Boaventura. 2015. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drisko, James W. 1997. Strengthening qualitative studies and reports: Standards to promote academic integrity. Journal of Social Work Education 33: 185–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, Eduardo. 1995. Native American Postcolonial Psychology. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, Eduardo, Bonnie Duran, Maria Yellow Horse Brave-Heart, and Susan Yellow Horse-Davis. 1998. Healing the American Indian soul wound. In International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 341–54. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, Todd A. 2011. Politics, Identity, and Mexico’s Indigenous Rights Movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, Javier I., Constanza Hoyos Nervi, and Michael A. Gara. 2000. Immigration and mental health: Mexican americans in the united states. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 8: 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, Antonio L. 2009. Mexican Americans and historical trauma theory: A theoretical perspective. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse 8: 330–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Campbell, Teresa. 2008. Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 23: 316–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Campbell, Teresa, Taryn Lindhorst, Bu Huang, and Karina L. Walters. 2006. Interpersonal violence in the lives of urban american indian and alaska native women: Implications for health, mental health, and help-seeking. American Journal of Public Health 96: 1416–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrega, Horacio, Jr. 1990. Hispanic mental health research: A case for cultural psychiatry. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 12: 339–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, Reynolds, and John Haaga. 2005. The American People: Census 2000. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Angela. 2019. “Wherever I Go, I Have It inside of Me”: Indigenous Cultural Dance as a Transformative Place of Health and Prevention for Members of an Urban Danza Mexica Community. Ph.D. thesis, University of Washington, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, Rossella. 2015. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing 24: 230–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriss, Susan, and Ricardo Sandoval. 1997. The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, Barbara, and A. Agresti. 1986. Statistical Methods for the Social Sciences. San Francisco: Dellen. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Antonio. 2017. How the Us Hispanic Population Is Changing. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Folgarait, Leonard, José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. 1998. Mural Painting and Social Revolution in Mexico, 1920–1940: Art of the New Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan, and Gaspar Rivera-Salgado. 2004. Indigenous Mexican Migrants in the United States. San Diego: University of California, Center for US-Mexican Studies and Center for Comparative Immigration Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, Viktor E. 2011. Man’s Search for Ultimate Meaning. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 2018. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ivis. 2020. Cultural insights for planners: Understanding the terms Hispanic, Latino, and Latinx. Journal of the American Planning Association 86: 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garduño, Everardo. 2004. Cuatro ciclos de resistencia indígena en la frontera méxico-estados unidos. Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe/European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 77: 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gee, Gilbert C., Andrew Ryan, David J. Laflamme, and Jeanie Holt. 2006. Self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: The added dimension of immigration. American Journal of Public Health 96: 1821–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimenez, Martha E. 1989. Latino/“hispanic”—Who needs a name? The case against a standardized terminology. International Journal of Health Services 19: 557–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginorio, Angela, and Michelle Huston. 2001. Si, Se Puede! Yes, We Can: Latinas in School. ERIC. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED452330 (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Glenn, Evelyn N., and Sandra Tam. 2004. Unequal freedom: How race and gender shaped american citizenship and labour. Canadian Woman Studies 23: 172. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez García, Rogelio, Margarita Alonso Sangregorio, and María Lucía Llamazares Sánchez. 2019. Factorial validity of the maslach burnout inventory-human services survey (mbi-hss) in a sample of spanish social workers. Journal of Social Service Research 45: 207–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gone, Joseph P. 2013. Redressing First Nations historical trauma: Theorizing mechanisms for Indigenous culture as mental health treatment. Transcultural Psychiatry 50: 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Barrera, Ana, and Mark Hugo Lopez. 2013. A Demographic Portrait of Mexican-Origin Hispanics in the United States. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. [Google Scholar]

- González de Alba, Iván Guillermo. 2010. Poverty in Mexico from an ethnic perspective. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 11: 449–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Bridget F., Frederick S. Stinson, Deborah S. Hasin, Deborah A. Dawson, S. Patricia Chou, and Karyn Anderson. 2004. Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and relatedconditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 61: 1226–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayshield, Lisa, Jeremy J. Rutherford, Sibella B. Salazar, Anita L. Mihecoby, and Laura L. Luna. 2015. Understanding and healing historical trauma: The perspectives of Native American elders. Journal of Mental Health Counseling 37: 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Bart N., Claire D. Johnson, and Alan Adams. 2006. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 5: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Judith. 2018. Confronting Immigration Enforcement under Trump. Social Justice 45: 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Griner, Derek, and Timothy B. Smith. 2006. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 43: 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilamo-Ramos, Vincent, Andrew Hidalgo, and Lance Keene. 2020. Consideration of Heterogeneity in a Meta-analysis of Latino Sexual Health Interventions. Pediatrics 146: e20201406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, Gerardo. 2015. Identity erasure and demographic impacts of the Spanish caste system on the Indigenous populations of México. In Beyond Germs: Native Depopulation in North America. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 119–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gy, Pierre M. 1992. Sampling of Heterogeneous and Dynamic Material Systems: Theories of Heterogeneity, Sampling and Homogenizing. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, Karen B. 2017. A call for healing: Transphobia, homophobia, and historical trauma in filipina/o/x american activist organizations. Hypatia 32: 696–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, Michele D., Erin R. Boyce, and Jessica Yang. 2017. The impact of historical trauma and mistrust on the recruitment of resource families of color. Adoption Quarterly 20: 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, Sandra. 1992. Rethinking standpoint epistemology: What is “strong objectivity?”. The Centennial Review 36: 437–70. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Sandra G. 2004. The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader: Intellectual and Political Controversies. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, James Paget, and Patricia M. Stephens. 2013. Stress, Health, and the Social Environment: A Sociobiologic Approach to Medicine. New York: Springer-Verlag Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, Leandra Hinojosa. 2019. Feminist approaches to border studies and gender violence: Family separation as reproductive injustice. Women’s Studies in Communication 42: 130–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette, and Ernestine Avila. 1997. “I’m here, but i’m there” the meanings of latina transnational motherhood. Gender & Society 11: 548–71. [Google Scholar]

- Honebein, Peter C. 1996. Seven goals for the design of constructivist learning environments. In Constructivist Learning Environments: Case Studies in Instructional Design. Englewood Cliffs: Educational Technology Publications, Inc., pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, David, and Elena Padrón. 2017. The practice of curanderismo: A qualitative study from the perspectives of curandera/os. Journal of Latina/o Psychology 6: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huirimilla, Juan Paulo. 2007. “Zapatismo: Democracia, libertad y justicia”. (entrevista a amado lascar). Alpha (Osorno) 24: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humes, Karen R., Nicholas A. Jones, and Roberto R. Ramirez. 2011. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Linda M., Suzanne Schneider, and Brendon Comer. 2004. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Social Science & Medicine 59: 973. [Google Scholar]

- INEGi XII. 2001. Censo General de Población y Vivienda 2000. Available online: http://www.inegi.gob.mx/est/default.asp (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Intrator, Jake, Jonathan Tannen, and Douglas S. Massey. 2016. Segregation by race and income in the United States 1970–2010. Social Science Research 60: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Don H. 2006. Signal-to-noise ratio. Scholarpedia 1: 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Kevin R. 1999. Celebrating latcrit theory: What do we do when the music stops. UC Davis School of Law 33: 753. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Taylor N. 2019. The dakota access pipeline and the breakdown of participatory processes in environmental decision-making. Environmental Communication 13: 335–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendi, Ibram X. 2019. How to Be An Antiracist. New York: One World. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Ronald C., Hagop S. Akiskal, Minnie Ames, Howard Birnbaum, Paul Greenberg, Robert M. A. Hirschfeld, Robert Jin, Kathleen R. Merikangas, Gregory E. Simon, and Philip S. Wang. 2006. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of us workers. American Journal of Psychiatry 163: 1561–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindig, David, and Greg Stoddart. 2003. What is population health? American Journal of Public Health 93: 380–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, Laurence J., Stéphane Dandeneau, Elizabeth Marshall, Morgan Kahentonni Phillips, and Karla Jessen Williamson. 2011. Rethinking resilience from Indigenous perspectives. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 56: 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, Laurence J., Stéphane Dandeneau, Elizabeth Marshall, Morgan Kahentonni Phillips, and Karla Jessen Williamson. 2012. Toward an ecology of stories: Indigenous perspectives on resilience. In The Social Ecology of Resilience. New York: Springer, pp. 399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, Nancy, Margarita Alegría, Naomar Almeida-Filho, Jarbas Barbosa da Silva, Maurício L. Barreto, Jason Beckfield, Lisa Berkman, Anne-Emanuelle Birn, Bruce B. Duncan, Saul Franco, and et al. 2010. Who, and what, causes health inequities? reflections on emerging debates from an exploratory latin american/north american workshop. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 64: 747–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Satish, Claire Bellis, Mark Zlojutro, Phillip E. Melton, John Blangero, and Joanne E. Curran. 2011. Large scale mitochondrial sequencing in Mexican Americans suggests a reappraisal of Native American origins. BMC Evolutionary Biology 11: 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, Joanna Catalina. 2016. Decolonizing and Re-Indigenizing Filipinos in Diaspora. Master’s thesis, California State University, Sacramento, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Leaf, Philip J., Martha Livington Bruce, Gary L. Tischler, and Charles E. Holzer, III. 1987. The relationship between demographic factors and attitudes toward mental health services. Journal of Community Psychology 15: 275–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Portilla, Miguel. 2011. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levac, Danielle, Heather Colquhoun, and Kelly K. O’Brien. 2010. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science: IS 5: 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, Moira, and Brid Delahunt. 2017. Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education 9: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Coria, Ramón, and Jesús Armando Haro Encinas. 2015. Derechos territoriales y pueblos indígenas en méxico: Una lucha por la soberanía y la nación. Revista Pueblos y Fronteras Digital 10: 228–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Douglas, and Nancy A. Denton. 1993. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matamoro, Blas. 1990. Diván de octavio paz. Hispamérica 19: 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, Lauren. 2007. Explaining mass-level euroscepticism: Identity, interests, and institutional distrust. Acta Politica 42: 233–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena Robles, Jorge, and Ruth Gomberg-Muñoz. 2016. Activism after daca: Lessons from chicago’s immigrant youth justice league. North American Dialogue 19: 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Zoila. 2001. Al Son de la Danza: Identidad y Comparsas en el Cuzco. Fondo Editorial. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Syrene A. 2001. Pico Worksheet and Search Strategy. Cave Creek: National Center for Dental Hygiene Research. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Syrene A., and Jane L. Forrest. 2001. Enhancing your practice through evidence-based decision making: Pico, learning how to ask good questions. Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice 1: 136–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mines, Richard, Sandra Nichols, and David Runsten. 2010. California’s Indigenous Farmworkers. Final Report of the Indigenous Farmworker Study (IFS) to the California Endowment. Indigenous Mexicans in California Agriculture. Available online: http://indigenousfarmworkers.org (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Mingers, John. 2001. Combining is research methods: Towards a pluralist methodology. Information Systems Research 12: 240–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, Chandra. 1988. Under western eyes: Feminist scholarship and colonial discourses. Feminist Review 30: 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohatt, Nathaniel Vincent, Azure B. Thompson, Nghi D. Thai, and Jacob Kraemer Tebes. 2014. Historical trauma as public narrative: A conceptual review of how history impacts present-day health. Social Science & Medicine 106: 128–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, Daniel Eduardo Matul. 1989. Estamos vivos: Reafirmación de la cultura Maya. Nueva Sociedad 99: 147–57. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Michael W., Kwok Leung, Daniel Ames, and Brian Lickel. 1999. Views from inside and outside: Integrating emic and etic insights about culture and justice judgment. Academy of Management Review 24: 781–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Patricia McGrath. 2002. The capabilities perspective: A framework for social justice. Families in Society 83: 365–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Carlos. 2007. Youth, Identity, Power: The Chicano Movement. Brooklyn: Verso Trade. [Google Scholar]

- Murphey, David, Lina Guzman, and Alicia Torres. 2014. America’s Hispanic Children: Gaining Ground, Looking Forward. Publication# 2014-38. Bethesda: Child Trends. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete, Federico. 2004. Las Relaciones Interétnicas en México. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete, Federico. 2005. El mestizaje y las culturas regionales. In Las Relaciones Interétnicas: Elective Course. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Available online: https://red.pucp.edu.pe/ridei/files/2012/02/120203.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Nevitte, Neil. 2017. The North American Trajectory: Cultural, Economic, and Political Ties among the United States, Canada and Mexico. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Noe-Bustamante, Luis, Antonio Flores, and Sono Shah. 2019. Facts on Hispanics of Mexican origin in the United States, 2017. Pew Research Center 16: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Tina, Paula L. Vines, and Elizabeth M. Hoeffel. 2012. The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010. Census Brief No. C2010BR-10. Available online: https://digitallibrary.utah.gov/awweb/awarchive?item=49864 (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Nurius, Paula S., and Charles P. Hoy-Ellis. 2013. Stress effects on health. In Encyclopedia of Social Work. Available online: https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Oehmichen, Cristina. 2007. Violencia en las relaciones interétnicas y racismo en la ciudad de méxico. Cultura y Representaciones Sociales 1: 91–117. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, Sumie, E. J. R. David, and Nancy Abelmann. 2008. Colonialism and psychology of culture. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2: 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva de Coll, Josefina. 1976. La Resistencia Indígena Ante la Conquista. Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J., Nancy L. Leech, and Kathleen M. T. Collins. 2012. Qualitative analysis techniques for the review of the literature. The Qualitative Report 17: 56. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Hershey, Araceli. 2019. Conditional Class Regression: A Model Derived to Examine within Group Heterogeneity in Large Scale Studies with Latinx-Hispanic Data Sets [Poster session]. Paper presented at Society for Prevention Research 27th Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, May 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Williams, Anna, Ramona Beltrán, Katie Schultz, Zuleka Ru-Glo Henderson, Lisa Colón, and Ciwang Teyra. 2021. An integrated historical trauma and posttraumatic growth framework: A cross-cultural exploration. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 22: 220–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, Laura Velasco. 2014. Transnational Ethnic Processes: Indigenous Mexican Migrations to the United States. Latin American Perspectives 41: 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, Esha. 2013. Reflexivity: Situating the researcher in qualitative research. Humanities and Social Science Studies 2: 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, Guillermo de la. 2005. Social and cultural policies toward indigenous peoples: Perspectives from Latin America. Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 717–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pereyra, Carlos. 1980. Historia, Para Qué? Mexico City: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, Rose M., and Ilona Arnold-Berkovits. 2018. A Conceptual framework for understanding Latino immigrant’s ambiguous loss of homeland. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 40: 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Micah D. J., Christina M. Godfrey, Hanan Khalil, Patricia McInerney, Deborah Parker, and Cassia Baldini Soares. 2015. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13: 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, Russell E. 1978. Impact of nazi holocaust on children of survivors. American Journal of Psychotherapy 32: 370–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihama, Leonie, Paul Reynolds, Cherryl Smith, John Reid, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, and Rihi Te Nana. 2014. Positioning historical trauma theory within aotearoa new zealand. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 10: 248–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinedo, Miguel, Yasmin Campos, Daniela Leal, Julio Fregoso, Shira M. Goldenberg, and María Luisa Zúñiga. 2014. Alcohol use behaviors among indigenous migrants: A transnational study on communities of origin and destination. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 16: 348–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, Pallav, and Thaddeus A. Herzog. 2014. Historical trauma and substance use among native hawaiian college students. American Journal of Health Behavior 38: 420–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas, Carlos A. Molina. 2012. Espacios de la mexicanidad. Espacialidades 2: 112–42. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, Enola, Hiie Silmere, Ramesh Raghavan, Peter Hovmand, Greg Aarons, Alicia Bunger, Richard Griffey, and Melissa Hensley. 2011. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 38: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prussing, Erica. 2014. Historical trauma: Politics of a conceptual framework. Transcultural Psychiatry 51: 436–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, Lucio Cloud, and Phillip L. Hammack. 2014. Surviving colonization and the quest for healing: Narrative and resilience among California Indian tribal leaders. Transcultural Psychiatry 51: 112–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revueltas, José, Andrea Revueltas, and Philippe Cheron. 1978. México 68: Juventud y Revolución. Mexico: Ediciones Era, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Rickford, Russell. 2016. Black lives matter: Toward a modern practice of mass struggle. In New Labor Forum. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, vol. 25, pp. 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rizo, Elisa. 2003. Juan rulfo y la representación literaria del mestizaje. Escritos, Revista del Centro de Ciencias del Lenguaje 28: 125–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, Maythee. 2007. Re-Membering Josefa: Reading the Mexican female body in California gold rush chronicles. Women’s Studies Quarterly 35: 126–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rundle, Christopher. 2014. Theories and methodologies of translation history: The value of an interdisciplinary approach. The Translator 20: 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahagún, Bernardino de, Arthur J. Anderson, and Charles E. Dibble. 1970. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Santa Fe: NM School of American Research. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña-Portillo, Josefina. 2001. Who’s the indian in aztlan? Re-writing mestizaje, indianism, and chicanismo from the lacandon. In The Latin American Subaltern Studies Reader. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 402–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, Anna Marie. 2009. Toward a Latina Feminism of the Americas: Repression and Resistance in Chicana and Mexicana Literature. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, Chela. 2013. Methodology of the Oppressed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Satcher, David. 2000. Mental health: A report of the surgeon general–executive summary. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 31: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semega, Jessica L., Kayla R. Fontenot, and Melissa A. Kollar. 2017. Income and poverty in the United States: 2016; Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 60–259.

- Silver, Alexis. 2014. Families across borders: The emotional impacts of migration on origin families. International Migration 52: 194–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano Hernández, Silvia. 1994. Lucha y Resistencia Indígena en el México Colonial. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Sotero, Michelle. 2006. A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice 1: 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stepler, Renee, and Anna Brown. 2016. Statistical Portrait of Hispanics in the United States. Pew Research Center. 19. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2016/04/19/2014-statistical-information-on-hispanics-in-united-states/ (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Stevens, Sally, Rosi Andrade, Josephine Korchmaros, and Kelly Sharron. 2015. Intergenerational trauma Among substance-using Native American, Latina, and White mothers living in the southwestern United States. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 15: 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, Shazeen, Kent D. Garber, and Lainie Rutkow. 2018. Xenophobia as a determinant of health: An integrative review. Journal of Public Health Policy 39: 407–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szreter, Simon. 2003. The population health approach in historical perspective. American Journal of Public Health 93: 421–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talebreza-May, Jon. 2015. Cultural trauma in the lives of men in northern New Mexico. The Journal of Men’s Studies 23: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, Richard G., and Lawrence G. Calhoun. 1996. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 9: 455–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, Wallace. 1921. The People of México: Who They Are and How They Live. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1: 1. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. 2000. Census 2000; Suitland: US Census Bureau.

- Valverde, Eduardo E., Thomas Painter, James D. Heffelfinger, Jeffrey D. Schulden, Pollyanna Chavez, and Elizabeth A. DiNenno. 2015. Migration patterns and characteristics of sexual partners associated with unprotected sexual intercourse among hispanic immigrant and migrant women in the united states. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17: 1826–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 1983. Discourse analysis: Its development and application to the structure of news. Journal of Communication 33: 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 2004. Knowledge, discourse and scientific communication. Paper presented at 8th International Public Communication of Science and Technology Conference, Barcelona, Spain, June 3–6; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 2006. Discourse, context and cognition. Discourse Studies 8: 159–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 2019. Racismo y Discurso en América Latina. Barcelona, Spain: Editorial Gedisa, vol. 311008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ee, Elisa, and Rolf J Kleber. 2013. Growing up under a shadow: Key issues in research on and treatment of children born of rape. Child Abuse Review 22: 386–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varcoe, Colleen, Annette J. Browne, and Laurie Cender. 2014. Promoting social justice and equity by practicing nursing to address structural inequities and structural violence. Philosophies and Practices of Emancipatory Nursing: Social Justice as Praxis 11: 266–84. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Hernández, José Guadalupe. 2005. Movimientos sociales para el reconocimiento de los movimientos indígenas y la ecología política indígena. Ra Ximhai 1: 453–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, José. 1993. La Raza Cósmica. Madrid: CESLA, Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos, Universidad. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, José, and Luis González. 1944. Breve Historia de México. Mexico: Editorial Polis. [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez, Melba J. T. 1998. Latinos and violence: Mental health implications and strategies for clinicians. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health 4: 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, William A., Richard L. Hough, and Manuel R. Miranda. 1985. Modeling Cross-Cultural Research in Hispanic Mental Health. Bethesda: National Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Vigil, James, and Felipe Lopez. 2004. Race and ethnic relations in Mexico. Journal of Latino/Latin American Studies 1: 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viruell-Fuentes, Edna A., Patricia Y. Miranda, and Sawsan Abdulrahim. 2012. More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social Science & Medicine 75: 2099–106. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Leite Paula, and Ximena Castañeda. 2010. Migration and Health: Mexican Immigrant Women in the United States. Joint Report. Mexico: Consejo Nacional de Populación de México. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, Nina, and Bonnie Duran. 2010. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health 100: S40–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, Karina, Selina Mohammed, Teresa Evans-Campbell, Ramona Beltrán, David Chae, and Bonnie Duran. 2011. Bodies do not just tell stories, they tell histories. Du Bois Review 8: 179–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, Karina, and Jane M. Simoni. 2002. Reconceptualizing Native women’s health: An “indigenist” stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health 92: 520–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, Karina L., Michelle Johnson-Jennings, Sandra Stroud, Stacy Rasmus, Billy Charles, Simeon John, James Allen, Joseph Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, Mele A. Look, Māpuana de Silva, and et al. 2020. Growing from our roots: Strategies for developing culturally grounded health promotion interventions in american indian, alaska native, and native hawaiian communities. Prevention Science 21: 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, Diane. 2007. On becoming a qualitative researcher: The value of reflexivity. Qualitative Report 12: 82–101. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, Hilary N. 2001. Indigenous identity: What is it, and who really has it? American Indian Quarterly 25: 240–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Thomas. 1992. Los Indios del Gran Suroeste de los Estados Unidos: Veinte Siglos de Adaptaciones Culturales, Editorial MAPFRE.

- Weinick, Robin M., Elizabeth A. Jacobs, Lisa Cacari Stone, Alexander N. Ortega, and Helen Burstin. 2004. Hispanic healthcare disparities: Challenging the myth of a monolithic Hispanic population. Medical Care 42: 313–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, Karen. 2017. What does a republican government with donald trump as president of the usa mean for children, youth and families? Children’s Geographies 15: 491–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbeck, Les B., Gary W. Adams, Dan R. Hoyt, and Xiaojin Chen. 2004. Conceptualizing and Measuring Historical Trauma Among American Indian People. American Journal of Community Psychology 33: 119–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Michael. 1998. Narrative therapy. In Workshop Presented at Narrative Therapy Intensive Training. Adelaide: Dulwich Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand, Phil C., and Jay C. Fikes. 2004. Sensacionalismo y etnografía: El caso de los Huicholes de Jalisco. Relaciones. Estudios de Historia y Sociedad 25: 98. [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Washington, Kristin N., and Chmaika P. Mills. 2018. African american historical trauma: Creating an inclusive measure. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 46: 246–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, Rachel, Sarah L. Halligan, and Robert Grossman. 2001. Childhood trauma and risk for ptsd: Relationship to intergenerational effects of trauma, parental ptsd, and cortisol excretion. Development and Psychopathology 13: 733–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, Rachel, James Schmeidler, Milton Wainberg, Karen Binder-Brynes, and Tamar Duvdevani. 1998. Vulnerability to posttraumatic stress disorder in adult offspring of Holocaust survivors. American Journal of Psychiatry 155: 1163–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, Steffi. 2006. Mexican Curanderismo as Ethnopsychotherapy: A qualitative study on treatment practices, effectiveness, and mechanisms of change. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 53: 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentella, Yoly. 2004. Land loss among the Hispanos of Northern New México: Unfinished psychological business. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 9: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentella, Yoly. 2009. Developing a Multi-Dimensional Model of Hispano Attachment to and Loss of Land. Culture & Psychology 15: 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Zentella, Yoly. 2014. No lloro pero me acuerdo: Hidden voices in a psychological model. Journal of Progressive Human Services 25: 181–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xiao, Ana P. Martinez-Donate, Jenna Nobles, Melbourne F. Hovell, Maria Gudelia Rangel, and Natalie M. Rhoads. 2015. Substance use across different phases of the migration process: A survey of Mexican migrants flows. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17: 1746–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizumbo-Colunga, Daniel, and I. Martínez. 2017. Is Mexico a Post-Racial Country? Inequality and Skin Tone across the Americas. Mexico: Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE), Topical Brief. vol. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga, María Luisa, Pedro Lewin Fischer, Debra Cornelius, Wayne Cornelius, Shira Goldenberg, and David Keyes. 2014. A transnational approach to understanding indicators of mental health, alcohol use and reproductive health among Indigenous Mexican migrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 16: 329–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1. | Mestizo refers to an individual of mixed race, especially one of Spanish and indigenous descent (De la Peña 2006). |

| 2. | Pueblos Originarios is a term used to identify human groups that descended from precolombian cultures of Mesoamérica that have preserved some of their social and cultural characteristics (De la Peña 2006). |

| 3. | Amerindian descent: Individuals whose ancestors include people who lived in North, Central or South America before the Europeans arrived (Kumar et al. 2011). |

| 4. | Native American People: An individual of any of the first groups of people living in North, Central or South America. In general this terms has been used to identify members of one of these groups from the U.S, however, this terms is also used to identify members of one of these groups across the Americas Kumar et al. (2011). |

| 5. | Indigenous-Hispanic: Individuals living in the USA that trace their heritage to Native American groups from México, Central and South America and also identify as Hispanic (Fernandez 2019). |

| 6. | Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is a tradition that celebrates the lives of the deceased and honored their memories. This tradition is traced to precolonial times and is one of biggest celebrations in México (Brandes 1998). |

| 7. | Danza folklórica can be traced to ceremonial and social dances with roots in the precolonial era. Nowadays, every state has its unique dance that represents them. Sometimes a dance will depict an event, such as the conquest of México, an animal from the area, or another element of the local lifestyle (Mendoza 2001). |

| 8. | Traditional medicine, also known as medicina del campo and curanderismo, is a syncretic system of healing that involves a holistic approach to wellness (Hoskins and Padrón 2017). |

| 9. | Unresolved grief refers to forms of historical loss that emerge from the inability to voice historical trauma experiences (Brave Heart 1998). |

| 10. | Internalize oppression occurs when those affected by colonial trauma internalize the views of the oppressor (Anzaldúa et al. 2003; Estrada 2009). |

| Sources | IMA-US | Topic of Interest | Context: HTEs or Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| * Anzaldúa et al. (2003) | Yes | Anxiety, depression | Invasion of the Americas |

| Brave Heart et al. (2011) | Yes | Behavioral health | Invasion of the Americas |

| Carvajal and Young (2009) | Yes | Behavioral health | Historical Trauma |

| Cromer et al. (2018) | Yes | Behavioral health | Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma |

| Estrada (2009) | Yes | Behavioral health | Indigenous Stress and Coping Model |

| *** Grayshield et al. (2015) | Yes | Grief | Colonization of the Americas |

| Hanna et al. (2017) | Yes | Behavioral health | Historical Trauma |

| Mohatt et al. (2014) | Yes | Behavioral health | Historical Trauma |

| Perez and Arnold-Berkovits (2018) | Yes | Ambiguous grief | Ambiguous loss of Homeland |

| Ramirez and Hammack (2014) | Yes | Depression/Grief | California Gold Rush |

| Stevens et al. (2015) | Yes | Behavioral health | Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma |

| Talebreza-May (2015) | Yes | Aggression, SUDs | Treaty of Guadalupe |

| Whitbeck et al. (2004) | Yes | Behavioral health | Historical Loss |

| ** Zentella (2004) | Yes | Land-based disorders | US-México War |

| Zentella (2009) | Yes | Land-based disorders | Invasion of the Americas |

| Zentella (2014) | Yes | Unresolved grief | Colonization |

| Source | HTEs | Theoretical Framework/Concept |

|---|---|---|

| Anzaldúa et al. (2003) | Invasion of the Americas | Split-Mind and Unresolved grief |

| Brave Heart et al. (2011) | Invasion of the Americas | Historical Trauma |

| Carvajal and Young (2009) | Colonization of the Americas | Historical Trauma and Multilevel Framework |

| Cromer et al. (2018) | Invasion of the Americas | Historical Trauma and Institutional Betrayal |

| Estrada (2009) | U.S. -México War | Indigenous Stress and Coping Model |

| Grayshield et al. (2015) | Colonization of the Americas | Historical Trauma |

| Hanna et al. (2017) | Colonization of the Americas | Historical Trauma |

| Mohatt et al. (2014) | Invasion of the Americas | Historical Trauma |

| Perez and Arnold-Berkovits (2018) | Forced Relocation | Ambiguous loss of Homeland |

| Ramirez and Hammack (2014) | California Gold Rush | Historical Trauma and Survivance |

| Stevens et al. (2015) | Colonization | Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma |

| Talebreza-May (2015) | U.S.-México War | Colonialism and Cultural Trauma |

| Whitbeck et al. (2004) | Invasion of the Americas | Historical Loss |

| Zentella (2004) | US-México War | Land-based disorders |

| Zentella (2009) | Invasion of the Americas | Land-based disorders |

| Zentella (2014) | Colonization | Unresolved grief |

| Population | Description |

|---|---|

| La Raza | This term coined by Vasconcelos (1993) denotes an overarching and collective cultural orientation that describes the relationship between the indigenous ancestors of Mexico and their descendants living in both Mexico and the United States (Estrada 2009; Talebreza-May 2015; Zentella 2004). |

| Indigenous People of the Americas | Indigenous peoples from North, South and Central America and their descendants (Brave Heart et al. 2011). |

| North-American Indians | People from North America, including Canada, México and the United States (Nevitte 2017). |

| AIAN | Native American people from the United States, it can include affiliated and unaffiliated tribes (Farley and Haaga 2005), often indigenous groups from México are included as non-affilaited tribes (Fernandez 2019). |

| Mexican | People born in México, or holding Mexican nationality through naturalization or parental links. It includes White, Black, Arab, Jewish, indigenous, Indigenous-Spanish (mixed/mestizo), and non-indigenous groups (INEGi XII 2001). |

| MAI | Mexican American Indian living in the United States (Fernandez 2019; Humes et al. 2011). |

| Mexican-American | People of Mexican ancestry born in the United States (Estrada 2009). |

| Chicano/x | “Is the assertion of an Indian identity, one made problematic by the simultaneous acknowledgement of our Spanish, African, etc, heritages, our mestizaje.”(Anzaldúa et al. 2003). |

| Hispanic | People from Spain or from Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America, this term excludes people from Brazil, where Portuguese is the official language (Flores 2017). |

| Latino/a/x | People from Latin America regardless of their official language, this term includes people from Brazil but excludes individuals from Spain (Flores 2017). |

| Ethnic minority | A group that has different national or cultural traditions from the main population. Four major racial and ethnic groups include: African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asians and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics (Cheung and Snowden 1990; US Census Bureau 2000). |

| Non-white | A person whose origin is not predominantly European (Humes et al. 2011). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orozco-Figueroa, A. The Historical Trauma and Resilience of Individuals of Mexican Ancestry in the United States: A Scoping Literature Review and Emerging Conceptual Framework. Genealogy 2021, 5, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5020032

Orozco-Figueroa A. The Historical Trauma and Resilience of Individuals of Mexican Ancestry in the United States: A Scoping Literature Review and Emerging Conceptual Framework. Genealogy. 2021; 5(2):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5020032

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrozco-Figueroa, Araceli. 2021. "The Historical Trauma and Resilience of Individuals of Mexican Ancestry in the United States: A Scoping Literature Review and Emerging Conceptual Framework" Genealogy 5, no. 2: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5020032