Abstract

The Killing Fields call into question my very being. How are we to live in and with the aftermath of an estimated 1.7 million people perishing? How are we, the survivors of this calamity, to discern our family (hi)stories and ourselves in the face of these irreparable genealogical fractures? This paper begins with stories—co-constructed with my father—about the Killing Fields, a genocide orchestrated by the Khmer Rouge and from which humanity appears to suffer a collective amnesia. The latter half of this paper turns to my engagements with ethical-political philosophy as a means to comprehend and make meaning of the atrocities described by my father. Drawing principally on the Yin-Yang philosophy and Thai considerations of the face, I respond to keystone Khmer Rouge ideas and strategies that “justified” the murder of over one million people. Philosophy teaches me to learn from and how to live with the Killing Fields. It offers me routes to make sense of my roots in the absence of treasure troves that would typically inform the writing of genealogies and family (hi)stories. This paper gives testimony to a tragedy of the past that is inscribed in the present and in the yearning for a better tomorrow.

1. Introduction

For the members of my family (whose faces I have never seen) and all those who suffer(ed) from the same, yet different, hatred of the other. As with all I do, my motivation is you.

Thursday 17 April 1975 began as a day of celebration for residents of Phnom Penh, the capital city of Cambodia. For years, the nation had been embroiled in a bloody civil war between the country’s military government (supported by the US) and the communist Khmer Rouge. The echoes of gunfire and bombs that became commonplace had disappeared around Phnom Penh, one of the military government’s last strongholds. Residents waved white flags and celebrated in the streets (Phnom Penh Post 2018). The war was over, and peace and unity were finally upon the nation, or so it seemed.

Heavily armed Khmer Rouge soldiers in black uniforms swept into the streets of Phnom Penh that day, met by cheering residents. Little did the city-dwellers realize that the soldiers were about to usher in one of the darkest chapters in Cambodia’s (hi)story1. The soldiers evacuated the city a few hours later and forced residents on a death march to rural parts of the country where they were imprisoned in communal agricultural labor communes. Other cities suffered the same fate. Over the next four years, around 1.7 million people were estimated to have died at the hands of the Khmer Rouge—a third to half by execution—some of whom are members of my family. One is hard-pressed to encounter a Cambodian today who did not lose loved ones in what has come to be known as the Cambodian genocide/Killing Fields2.

Survivors of the Killing Fields are still mourning to this day, and families are fractured beyond repair. The exact number of fatalities may never be known, as unidentifiable skeletal remains continue to be uncovered from Cambodia’s many Killing Fields, while the fates of others remain a mystery. Yet, there is another eerie silence that haunts the Killing Fields. Only three Khmer Rouge have been convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity3, while proceedings against two others were terminated following their deaths by natural causes4 (Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia n.d.). Also deeply troubling is the fact that few across the globe know of the Killing Fields.

This paper offers personal testimonies of the Killing Fields and a philosophical response to this atrocity. I begin with some remarks on the importance of stories and storytelling as means to document, critically understand, and make meaning of profound human experiences. The subsequent two sections are stories of the Killing Fields that I co-constructed with my father, an eyewitness and survivor. These stories, inevitably partial and subjective, provide the contexts through which my genealogy is irreparably fractured. In the latter half of this paper, I turn to my engagements with ethical-political philosophy to comprehend and make meaning of the atrocities described by my father. Drawing principally on the Yin-Yang philosophy and Thai considerations of the face, I respond to two keystone Khmer Rouge ideas and strategies that “justified” the murder of over one million people: self-sufficiency and the extermination of the (ethnic) other as a means to “purify” the populace. I argue that no identity is “pure” because nothing can be in and of itself. All identities presuppose and come into being in relation to the other—the other to whom we are bound by ethical-political responsibility. These philosophical expositions offer me routes to make sense of my roots in the absence of archival treasure troves that would typically inform the writing of genealogies and family (hi)stories. Philosophy, as unfolded here, is itself a form of postmemory—it is a living connection to traumatic experiences of the Killing Fields that preceded my birth but nevertheless shape my be(com)ing5.

2. What Is the Story with Stories?

I was born in Aotearoa-New Zealand on 24 August 1991 to a Thai mother and a Cambodian-born Chinese father. Listening to my parents tell stories are some of my earliest and fondest memories of life. I inherited the art of storytelling from them. Growing up, my parents told me stories of life and death that were profoundly distressing. I learned through some stories that members of my family were executed by the Khmer Rouge or were taken away, never to be seen again. Others survived the Killing Fields but died before their stories could be recorded. In all of these cases, my family’s (hi)stories vanished with them. I inherited a family archive in part without archives.

In this paper, I emphasize the importance of stories and storytelling—particularly the genre of testimony—as an ethical-political enterprise6. Narrative scholars remind us that stories do work; in particular, they enable people, communities, and nations to share, record, and make sense of wide-ranging human experiences (Farquhar and Fitzpatrick 2019; Frank 2010; Hancock 2019). As a form of narrative work, Hackett and Rolston (2009) suggest that, “Testimony is not just a simple exercise, ‘allowing victims to get things off their chest’… [it is] not only about individual healing; it is also about shared responsibility for societal change” (pp. 360–61).

Storytelling is a matter of survival and a means of scholarly work. The haunting presence of absence, loss, and death prompts me to record—and attempt to make meaning of—the testimonies told here. I (re)tell these stories for two purposes: first, to begin to preserve my family’s (hi)stories and, especially, to leave traces for the generations to come so that they may grow up with a better understanding of their/our genealogy and of the context in which it was almost destroyed and irrevocably shaped, and second, to educate myself and others about these atrocities, as well as employ philosophical ideas to understand more deeply their significance. My work here is, in effect, one of postmemory, that is, a living connection to the past through bearing witness to the cultural and collective trauma suffered by those who precede me (Hirsch 2012; Hoffman 2005). Narrative work facilitates, for me, a living, affective connection to the Killing Fields and to family members whose faces I may/will never see.

A Note on Method

Crafting my genealogy and family (hi)stories was no easy task due to the presence of absence. The Khmer Rouge cremated the treasure trove of official archives that would typically inform the writing of genealogies and family (hi)stories, such as birth, death, and marriage records and immigration documents. Family photographs, diaries, letters, and other records were left behind when the Khmer Rouge swiftly evacuated Cambodia in 1975. These archives, too, have since perished. All personal belongings carried on the body, such as watches, were confiscated upon arrival at the labor communes. The precise dates of events were consequently lost with the passage of time. My father and I relied on personal memories and the stories of others—such as memoirs, (documentary) films, scholarly research, and newspaper articles—to piece together the testimonies presented here.

Over several months, my father and I co-constructed the two testimonies that immediately follow: The Khmer Rouge: Executors and Executioners of the Killing Fields and Survival: Stories from my Father. We engaged in a series of face-to-face conversations that took place in the familiar surroundings and safety of our family home, sitting at our dining table or in the lounge opposite our family shrine. Some days, we spent long hours trawling through my father’s personal and deeply painful memories. On other days, our engagements were more fleeting as we wrestled with the demands of our lives. Our initial conversations began, I later realized, in the middle of my father’s experiences in the labor communes. We then traced back and forth between events leading to the Killing Fields and life immediately after.

My father’s personal memories of the Killing Fields are recorded in writing for the first time here. My father remembered other important details as he (re)read my work-in-progress text and as we researched and read other accounts of the Killing Fields. I also recalled stories that he told when I was younger, which interanimated our conversations and enabled me to recraft the text. The text presented here is inconclusively conclusive/conclusively inconclusive7. It reflects where my father and I have arrived to date and constitutes points of departure for future lines of enquiry and more extensive considerations than what has been possible here.

I employed ambiguity as a narrative device to obscure certain identifying details. This device enabled me to respect the wishes of family members who requested that they and others not be explicitly identified for various reasons, while still giving me permission to include their stories. Some family members continue to live in fear of persecution knowing there are still (former) Khmer Rouge soldiers in the world—one of the facets of what Hackett and Rolston (2009) call “the unspeakability of suffering” (p. 358). Elsewhere, however, such ambiguity and silences were inevitable given the aforementioned fractures in my genealogy. With the above sentiments in mind, I now offer the following testimonies of a tragedy of the past that is inscribed in the present and in the yearning for a better tomorrow.

3. The Khmer Rouge: Executors and Executioners of the Killing Fields

17 April 1975 is a date seared into the memories of many Cambodians. Only days after the Cambodian New Year, guerrilla soldiers in black uniforms and checkered krama (scarfs) swept into the streets of Phnom Penh. Armed with AK-47s, RPGs, tanks, and other weapons, the soldiers shortly began evicting residents of the city and forcing them into the countryside under the façade of further US bombings. The threat of bombings did not seem farfetched. Cambodia had endured years of warfare and bloodshed, not least as a result of US aerial bombings which spilled over to Cambodian soil during the Vietnam War (Kiernan 2004). Other cities in Cambodia followed suit. Most city dwellers made the journey to the countryside on foot in the searing April sun. Many perished along the way. Cambodia had suddenly fallen captive to the Khmer Rouge, members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, led by Pol Pot.

The evacuation(s) marked the beginnings of the Khmer Rouge’s social engineering project. The Khmer Rouge believed that the population comprised two groups: Neak Chas (literally “Old People”) and Neak Thmei (“New People”). Old People were supporters of the Khmer Rouge and/or inhabitants of rural communities (villagers, farmers, and those who did not receive formal education) liberated by the Khmer Rouge before 1975 (Chigas and Mosyakov n.d.; Mam 1999). New People were inhabitants of areas controlled by the military government prior to April 1975 (Kiernan 2008). New People were formally educated, city dwellers, and “traitors” who did not participate in the struggle to overthrow the US-supported military government during the Cambodian civil war (Chigas and Mosyakov n.d.). The Khmer Rouge systematically forced the entire nation into rural, communal agricultural labor communes. The Khmer Rouge hoped that an agrarian, “self-sufficient”/self-reliant8 utopia of equality would ensue, but that did not transpire (Ciorciari 2006, p. 11).

The Khmer Rouge sought a clean slate. The country’s antecedents were to be eradicated to clear the path for the “revolution”. New People were subject to harsher treatment than their counterparts. Teachers, intellectuals, students, doctors, and those who could speak a foreign language were asked to identify themselves and promised better living conditions than those in the labor communes. Little did they realize that they were to be purged. Those associated with the previous administration, too, were executed en masse. Borders were closed, and ties to the outside world were severed in the name of (national) self-sufficiency. Banks and currency were abolished. Hospitals and factories were closed. Religion was banned, and monks forced to disrobe (Di Certo 2012). Places of worship and schools were destroyed or converted into repositories, prisons, or torture and execution centers. Family members were separated from one another in order to dismantle traditional family structures. Children and teenagers—considered by the Khmer Rouge as more ruthless towards others (Boyden 2003)—were stolen from their parents and forced into concentration camps where they were brainwashed into becoming Khmer Rouge soldiers. Traces of the past were cremated. “Year Zero” had begun and, with it, one of the bloodiest massacres of the twentieth century and in the history of humankind.

In early 1976, “Democratic Kampuchea” was born with Pol Pot as its Prime Minister. Conditions in Democratic Kampuchea grew increasingly intolerable. As Thoun Cheng, a survivor, recounts: “Everybody was now obliged to work in the fields or dig reservoirs from 3 or 4 a.m. until 10 p.m…One day in ten was a rest day” (in Kiernan 2004, p. 364). Food was rationed, with New People receiving less food, despite excruciating labor on the fields (Mam 1999; Tryner and Rice 2015). Executions continued. Those who did not meet labor quotas were deemed “enemies” of the state and were purged. So, too, were innumerable others who fell within the Khmer Rouge’s broad scope of “enemies”, including Khmer Rouge cadres irrespective of their rank (Cruvellier 2018). Enemies were ubiquitous—“lurking behind every tree”—in the eyes of the Khmer Rouge (Ciorciari 2006, p. 11).

The Khmer Rouge advocated an ideology of fear and hatred of the (ethnic) other. The Chinese, Thai, Vietnamese, Cham Muslims, and other (ethnic) minorities were exterminated for the “purification’ of the Khmer ‘race’” (Hannum 1989; Kiernan 2001). No one was safe. Such was the horror of Democratic Kampuchea that, by 1979, an estimated 270,000 Cambodians had fled the Khmer Rouge and sought sanctuary in Thai refugee camps (Liev and Chhun 2015). It has been estimated that 1.7 million people lost their lives in just under four years of Khmer Rouge rule (Caswell 2014; Chandler 2008; Kiernan 2008). Some perished due to malnutrition, exhaustion, and inadequate medical care, while a third to half were executed (Heuveline 2001). Victims were regularly hacked to death with axes and decapitated and dismembered with spades. Others suffered blows to the back of their heads or had their throats slit with sugar cane branches. Organs, such as livers and gallbladders, were occasionally harvested from victims and consumed by the Khmer Rouge soldiers (Campbell 2015; Wyke 2016). Bodies were discarded in mass graves. These graves were often dug by the victims themselves prior to their execution. Human life was expendable to the Khmer Rouge, a belief illustrated in their axiom: “To keep you is no gain, to lose you is no loss” (Etcheson 2004, p. 177).

Infants and children, too, were not spared. The Khmer Rouge feared that children would grow up to avenge their parents’ death. Thus, they averred, “To stop the weeds, you must also pull up their roots” (International People’s Tribunal 1965 2016). At some sites, executioners systematically grabbed infants and children by their legs and feet and bludgeoned their bodies against girthy tree trunks (Buncombe 2009; Kavoori 2016). Heads of infants and children were split open, and, in some cases, while their bodies were still convulsing, they were tossed into a nearby abyss where their parents and countless others laid. Other infants and children were murdered before their parents’ eyes. Some of these Killing Trees remain standing and draw attention to the stories of those whose blood once soaked their trunks (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Killing Tree against which babies were executed. Resource from: https://protect-au.mimecast.com/s/aXxcCGv0kQtWBvg6I0hZc8?domain=search.creativecommons.org (accessed on 25 March 2021).

On 25 December 1978, 150,000 Vietnamese troops invaded Democratic Kampuchea after the Khmer Rouge engaged in a series of border confrontations with Vietnam (Kiernan 2002). Within two weeks, the Khmer Rouge rule of Cambodia was overthrown. Pol Pot and the higher echelons of the Khmer Rouge retreated to the northern jungle bordering Thailand where they remained active for some years, though with reduced capability and influence (Kiernan 2008). With the world in the midst of the Cold War, the Khmer Rouge was supported by the US and its allies in an attempt to diminish the influence of their then-adversaries (Vietnam and the Soviet Union) in Southeast Asia (Deth 2009). The US, Britain, and China went so far as to insist that Khmer Rouge representatives occupy Cambodia’s seat at the United Nations, even after Democratic Kampuchea collapsed (Pilger 2000). Pol Pot was denounced by his former comrades in 1997 after an internal Khmer Rouge feud and was subsequently sentenced to life under house arrest (Shivakumar 1998). On 15 April 1998, Pol Pot died. He suffered an apparent heart attack, evading trial before an international tribunal.

4. Survival: Stories from My Father

My father is an eyewitness and survivor of the Killing Fields. He was born in 1961 in Battambang, a province in northwestern Cambodia. He is the fourth of six children born to immigrant parents from Hoiping, Guangdong, China. Throughout my life, my father has returned to and retraced his horrific experiences of the Killing Fields in conversations with me. These are his stories.

My father was 14 years old when the Khmer Rouge came to power. He vividly remembers the day Battambang was evacuated by armed soldiers dressed in black uniforms—not dissimilar to events that occurred in the country’s capital.

“The Khmer Rouge walked peacefully into Krong Battambang (Battambang City) … Later, they told us the Americans were going to bomb our city. Everyone had to go to the countryside where we would be safe. We can return in three days. We don’t need to take anything because the Khmer Rouge would look after our things”, my father recounted.

Those who refused to leave their homes were hauled out to the streets and shot, like the camera shop owners who lived across the road from my father. My father and his family had to follow the orders or else they, too, would be murdered.

Like fellow city dwellers, my father and his family set course for the countryside. They walked about 20 km to Sneung where they had relations. They stayed there for one or two weeks before the Khmer Rouge emptied this village. They were forced to follow the rest of the village in marching one or two days to be imprisoned in one of many rural, communal agricultural labor communes established by the Khmer Rouge. It was in these communes where my father would spend some of the most trying years of his life.

Life was unbearable in the communes. Youths and adults were separated from one another in an attempt to “clean the brains of children and to train them to be like the Khmer Rouge because children could be easily taught”, my father told me. He lived in a commune over 10 km away from his parents and was separated from his siblings. Everyone in the communes was forced into backbreaking agricultural labor, regardless of age. My father said, “People worked day and night to grow rice and dig irrigation canals but were given very little to eat. You were lucky to get a small rock of salt with borbor (congee) made of a few grains of rice…We were so hungry we ate bugs sometimes but in secret. The Khmer Rouge would kill us if they found out”. Many died of starvation, malnutrition, and exhaustion in my father’s commune and on the fields where he engaged in the backbreaking labor of rice farming. Many were executed too, particularly ethnic minorities.

My father’s commune collapsed in late 1978 or early 1979, as Vietnamese forces defeated the commune’s Khmer Rouge soldiers. My father was forced to evacuate again. He was reunited with his parents and siblings at a neighboring commune as Vietnamese forces pushed Khmer Rouge soldiers back. He never thought he would see their faces again.

The Khmer Rouge’s animosity towards the ethnic other intensified as Vietnamese forces continued to wage war against the regime.

“One day, the Khmer Rouge pointed at my uncle and said he was Vietnamese because he had white skin, but he was Chinese…You knew you were finished. You could do nothing. You couldn’t argue with the Khmer Rouge”, my father recalled, tears gathering in his eyes.

The Khmer Rouge soldiers rounded up my father’s uncle and his immediate family. One by one they were executed right before my father’s eyes. My father’s uncle and aunt were struck at the back of their necks with a girthy tree trunk. They died instantly. My father’s young cousin was tossed in the air by a Khmer Rouge soldier. His body was in free fall when the soldier pierced his stomach with a machete. My father watched helplessly as his cousin gasped his last breaths. Their lifeless bodies were hurled into a cart overloaded with countless others, destined for disposal in one of many mass graves. These are my father’s last(ing) memories of his uncle, aunt, and cousin.

The commune where my father and his family resided was shortly liberated by Vietnamese forces. They made a month-long return journey in bare feet to Battambang. They walked at night, hid in fields, and slept beside corpses to avoid being recaptured by the Khmer Rouge. Their feet were swollen and covered in lacerations and prickles, but they felt no pain from these injuries. Nothing could be as agonizing as the previous four years.

Word spread that refugee camps had been established along the Thai-Cambodian border soon after my father and his family arrived in Battambang. They set out again on foot, arriving at Nong Chan in Thailand about two days later.

Sanctuary at Nong Chan was short-lived. A couple of weeks after their arrival, the Thai military ordered my father, his family, and tens of thousands of other Cambodian refugees to board buses9.

My father optimistically thought he and his family were finally on the road to peace, freedom, and a new life. He remembers encountering a group of Thai people at one pitstop. The Thai people offered food and water and asked my father’s family if they knew where they were going. My father recalled: “The Thai people told us the Thai army were taking us to die…They told my parents to leave the kids with them if they wanted the kids to survive. We did not believe the Thai people and continued with the bus journey”.

After two or three days on the buses, the Thai military forced everyone to disembark in the early hours. The refugees found themselves repatriated in Phnom Dângrêk, a mountain range that forms a natural border between Thailand and Cambodia. They were chased at gunpoint down the green mountain back towards Cambodia. Many struggled to make it down the steep and dense terrain. Some of the elderly, pregnant women, and those injured gave up and chose to stay in Phnom Dângrêk, where my father assumed they must have died. Others trekked down the mountain, clutching at vines, shrubs, and anything they could hold on to for their lives.

Thousands of people searched for water as they navigated their way across the steep terrain. My father recalled two men who suddenly spotted a small pool at the bottom of the mountain, and crowds rushed towards the water. They set off a series of invisible landmines, and many were blown to pieces. Others lost their limbs and died slow, painful deaths. My father will never forget the face of one child who laid on the ground while his father went in search of water. The child’s face was mutilated beyond recognition by one of the explosions. He was no more than nine years old and died of his injuries shortly after. The child’s father wrapped his son’s body in a rag and proceeded to cremate him. He said to my father that he had nothing left and was going to seek refuge in Vietnam. My father never saw him again and wondered if the man survived.

The series of explosions alerted a group of nearby soldiers. The soldiers fired several warning rounds into the air to stop the identifiable group from approaching any further. Some refugees feared the worst: that they had once again fallen captive to the Khmer Rouge. A few brave members of the group approached the soldiers and discovered that they were friendly Vietnamese forces. Some soldiers provided one spoon of rice and one spoon of flour to each member of my father’s family, which they then “cooked” using terracotta-hued water collected from craters in the ground.

My father believes that he and his family walked for at least two months after they and others were deserted in Phnom Dângrêk. They did not know where they were going. They just kept walking, blindly following those leading in the front like a herd of sheep. The crowd encountered other Vietnamese soldiers along the way who donated whatever food they could. My father credits the kindness and generosity of Vietnamese soldiers for keeping his family and many others alive.

Much to their surprise, my father and his family found themselves back at Nong Chan with other refugees in late 1979 or 1980. They were directed to board trucks upon arrival and taken to Khao-I-Dang Holding Center in Thailand, where they remained until 1981. Later in the following year, my father and his family were transferred to Phanat Nikhom Refugee Camp in Chon Buri, Thailand, where they were examined and treated by doctors while they awaited news of their impending resettlement.

In 1984, my father and his family were invited to resettle in a country that they had never heard of—New Zealand—bringing to an end a decade of unfathomable terror; however, the trauma of this period endures.

5. Learning to Live with the Killing Fields: Ethics, Politics, Relationality

I have sifted through the rubble described in the preceding testimonies for much of my life. I hoped I might find some members of my family—some whose faces I have never seen—or at least find other traces of their existence. Hope turned to despair at times as the years passed. I have learned to accept that some family members will be perpetual enigmatic figures to me, accessible only through my family’s testimonies and my own postmemory work of “imaginative investment, projection, and creation” (Hirsch 2012, p. 5).

My grandfather is one such figure. He would have been more than 105 years old at the time of the writing of this paper. I cannot tell you his exact age or his date of birth. Perhaps my grandfather survived the Killing Fields. Perhaps he remarried and I have other relations elsewhere in the world. Perhaps my grandfather’s skeletal remains have yet to be exhumed from one of the many mass graves. Perhaps his unidentifiable and dismembered skull is among those on display in the stupa at the Choeung Ek Killing Fields as testimony to the atrocities that once occurred there. Perhaps it suffices to know that I may never know.

I have found a constant companion in the excruciating and largely unsuccessful search for members of my family—a companion that I have come to know in recent years as philosophy. Philosophical inquiry, as the title of this paper suggests, teaches me to learn to live with the Killing Fields. It offers me routes to make sense of my roots; openings to comprehend—to the extent possible—this incomprehensible calamity from which my genealogy is irreparably fractured. Philosophy challenges me to question how I might live my life in light of the Killing Fields—how I might live in a manner so that the suffering of immediate survivors and the (assumed) deaths of others were not in vain.

It is to my intimate relationship with philosophy that I turn for the remainder of this paper as a means to comprehend and make meaning of the atrocities described by my father. The Khmer Rouge sought to be self-sufficient (in theory at least) and to exterminate the (ethnic) other as a way to “purify” the populace. The Khmer Rouge was largely successful with the latter; those of Chinese and Thai ethnicities were among the victims, some of whom are my ancestors. In the discussion that follows, I draw principally on the Chinese philosophy of Yin-Yang and Thai considerations of the “face”—both wisdoms/stories I have inherited from my ancestors—to interrogate the abovementioned Khmer Rouge ideas and strategies. I problematize the notion of self-sufficiency. I contend that there is no clean slate—nothing can be in and of itself but only in relation to what is otherwise. Consequently, I argue that our relationships should not be premised on a fear and hatred of the other, as espoused by the Khmer Rouge. At the heart of our relationships must be a fear for the other and their well-being—a fear for the other’s absolutely singular, irreplaceable face that adorns our worlds.

5.1. Yin-Yang: Separate yet Inseparable

The Yin-Yang philosophy posits that the universe and all phenomena within it are produced through the intra- and interactions of cosmic energies known as Yin and Yang. This idea is depicted in the symbolism below (Figure 2). Yin is the black side of the symbol, and Yang is the white side. Together, they form the symbol as a whole, which represents the universe and all phenomena within it. While Yin and Yang are conceived as separate forces, they are also—paradoxically—inseparable. One can only exist and be defined in relation to the other. The mutual constitution and inseparability of Yin and Yang is further portrayed by each side containing traces of the other within it (the black circle contaminating the white side and the white circle contaminating the black side).

Figure 2.

Yin Yang—symbol. Resource from: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/dda8fdd9-f083-4546-bf9b-c5f44ba59dff (accessed on 25 March 2021).

My exposition here is intentionally light and offers a partial definition of Yin and Yang. The reason is that Yin and Yang are not static concepts and, therefore, elude an absolute or neat interpretation or definition. Instead, Yin and Yang come to be defined and are redefined in the particularity of contexts. In one context, Yin might be described as death and Yang as life, which, together, constitute existence. We could not understand life without death and vice versa. Elsewhere, Yin might be described as a trough and Yang as a crest. Together, the trough and crest form a wave(s). Neither a crest nor a trough would exist without the other. Yin and Yang, however, should not be conceived as total opposites. They are relative to one another. Yin and Yang embody the philosophy they espouse: they are defined in relation to what is beyond themselves—what is otherwise—because nothing in this world is self-sufficient.

Change is an ontological and epistemological assumption of the Yin-Yang philosophy. What constitutes Yin and Yang is not only determined by perpetually changing contexts, but, in any given context, Yin also morphs into Yang and vice versa. Continuing with the examples provided above, we could interpret death (Yin) as an opening to the next life, whatever that might comprise (Yang). A crest (Yang) similarly is the beginning of the next trough (Yin). Change is constant. Rotating the Yin-Yang symbol on an axis visually reveals the incessant, cyclical metamorphosis of Yin and Yang10.

I take issue with the Khmer Rouge’s advocacy of self-sufficiency and purity through the extermination of the (ethnic) other. No identity is self-contained and uncontaminated, as encapsulated in the Yin-Yang philosophy. It is partially through the existence of an-other being(s) (human or otherwise) that any identity at all is possible. The “purity” of the populace desired by the Khmer Rouge is held captive precisely by what is radically otherwise. How could the Khmer Rouge have defined a “pure Khmer race” if not in relation to the ostensibly “impure” ethnic minorities they so barbarically sought to annihilate? Similarly, the words, arguments, and testimonies presented here are themselves an inheritance from the outside. It is only through relationships with the Khmer Rouge and others that I can (re)tell these stories about the Killing Fields, however agonizing these experiences may be. It is in relationship with the other, the constitutive outside, that I come to be—the other to whom I must exercise generosity.

Like the Yin-Yang symbol, I am always-already fractured from within. I am at once constituted and compromised by the other, the outside that is always-already partially inside. I cannot exist in and of myself but, rather, through the constellation of ineffaceable traces of the other within me. The predicament traced in preceding pages is radically exterior to me, foreign to me because I did not and cannot experience the Killing Fields firsthand. Yet, the predicament is always-already interior. The Killing Fields are inevitably a part of me, shaping and reshaping this/my life and these stories of mine. The other is implicated in my being and my stories, as am I in theirs.

I find much purchase and solace in the Yin-Yang philosophy for making sense of the Killing Fields and life thereafter. This philosophy demands that we understand subjectivities relationally. Yin and Yang encourage us to embrace and make sense of our worlds through our entanglements with the other and their differences, rather than supporting or accepting their erasure as advocated by the Khmer Rouge. These differences already exist in tension, often prior to our immediate consciousness. Tensions are not anathemas to be exterminated once and for all but are the very conditions that produce our worlds and can enable justice to arise. The Yin-Yang philosophy also challenges me to search for the goodness that exists even in the most terrible; the goodness that can only be defined in the face of the most terrible. This philosophy invites me to consider the sufferings and the deaths of over one million people at the hands of the Khmer Rouge as an opening for a more ethical, relational way of being for humanity forthwith.

5.2. The Face and Ethical Responsibility in Thai Culture

As alluded to above, I contest the fear and hatred of the (ethnic) other espoused by the Khmer Rouge. All identities presuppose otherness and come into being in relation to such alterity. It is the other to whom I owe my being and to whom I am primordially indebted. I argue, then, that a fear for the other (human) and their well-being must be at the heart of all relationships instead. A fear for—following Thai culture—the other’s face.

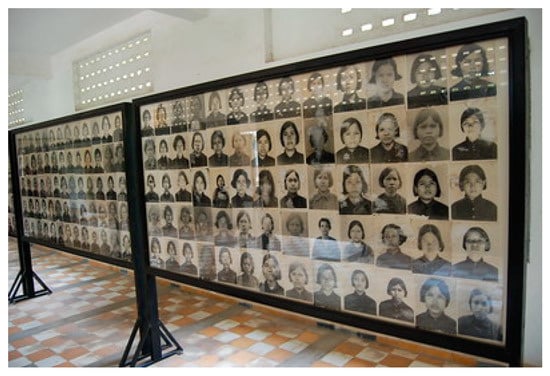

The face (หน้า) is widely regarded as sacrosanct in Thai culture (and, indeed, in other Asian cultures; see, for example, Liev 2008). To most Thais, the face serves as a metaphorical expression for one’s social standing, which must be closely guarded. The face speaks to one’s reputation, honor, integrity, authority, and influence (Komin 1990; Ukosakul 2005). As Thai scholar Sunatree Komin (1990) writes, “The ‘face’ is identical with the… ‘ego’” in Thai worldviews (p. 691). However, the metaphorical face is not dismembered or disembodied. The metaphorical face is always-already bound to, and in part revealed through, a literal face. The face, both metaphorical and literal, is absolutely singular. Each face, like those of the 1.7 million victims of the Killing Fields, expresses stories—individual stories of social standing and honor, trials and tribulations, hopes and aspirations, and so on. Each face adorns the world with its radical otherness and irreplaceability (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Female victims of the Khmer Rouge, Security Prison 21 (S-21), Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Resource from: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/607ce54b-74dd-4e44-b310-ce2a80e437f1 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

Thai considerations of the face embody relational, paradoxical, and changing qualities, in a similar vein to the Yin-Yang philosophy. The face carries traces of the other within it. The face is never one’s own alone but is always-already bound to the collective(s) to which one belongs. Nothing is self-sufficient. “My” reputation, honor, integrity, authority, and influence are derived partially from those with whom I am in relation (family members, friends, colleagues, organizations, etc.). In turn, my conduct has consequences for both “my own” face and—most critically—those of others. I am answerable to others, interrogated for my (in)actions.

The face governs sociality in Thai culture. While the face is exalted, it is also considered very “sensitive” by most Thais (Komin 1990, p. 691). The face is threatened, exposed, and vulnerable to wounding as “my” social standing and those of others are not static. One’s reputation, honor, integrity, authority, and influence can be diminished (and augmented) at any moment through one’s conduct. At the heart of all relationships for Thai people generally is an order to be ethically responsible to the face—both those of others and “my own”—given the face’s sacrosanctity and vulnerability.

The (central) Thai lexicon is rife with expressions that reveal this ethical and cultural demand. Instilled in most Thais are our primary, non-negotiable responsibilities to take care of or to preserve the face (รักษาหน้า), to love the face (รักษาหน้า), and to give face (ให้หน้า) in our face-to-face relationships with others. One must avoid at all costs conduct that might lead to losing face (เสียหน้า), tearing someone’s face (ฉีกหน้า), snapping someone’s face (หักหน้า), shattering someone’s face (หน้าแตก), not keeping face (ไม่ไว้หน้า), or displaying a thick/shameless face (หน้าหนา). I am held captive by the face, bound to it by ethical responsibility11. Ethical responsibility to the face offers a way of thinking, being, and doing that allows people to make a good life against and in response to the atrocities experienced by my family and so many others.

5.3. The Irresponsibility of Ethical Responsibility: Politics and Justice

Yet, there is also a danger that haunts ethical responsibility to the face. The Khmer Rouge exploited conceptions of the face to incite their genocidal strategies (see Hinton 1998). However, this exploitation does not constitute sufficient grounds for dismissing considerations of the face. The face offers us a compelling philosophical frame that calls people to ethical action—a life-giving impulse.

I inherited from the Yin-Yang philosophy the imperative to fracture identities that might appear as self-sufficient or pure in order to look for traces of the other within them. In so doing, an otherness that has hitherto been concealed, excluded, subjugated, ignored, or neglected within any given identity is revealed. An otherness that is in fact constitutive of the very identity that presents itself as self-sufficient. The Yin-Yang philosophy reminds us, then, that ethical responsibility cannot exist in and of itself.

Ethical responsibility is only what it is by virtue of being partially otherwise than ethical, through the unavoidable co-presence of irresponsibility that is within ethical responsibility. In other words, irresponsibility exists in the name of (within and for the sake of) ethical responsibility. Any perceived responsibility expounded by the Khmer Rouge in the pursuit of their political goals was an act of irresponsibility towards the faces of their victims. I vehemently condemn the Khmer Rouge’s practice of killing and/or torturing others. However, my point here more broadly is that ethical responsibility is always-already political, always-already irresponsible, if we are to take differences seriously (see Dam 2018).

Our ethical responsibilities to the face do not end there, however. We cannot merely dismiss our irresponsibility to other faces as a fait accompli. The unattainability of ethical responsibility for all faces necessitates the intervention of justice (Levinas 1991). Justice here is the turn towards the other faces we have inevitably excluded or betrayed. That is, justice is ethical responsibility for the “third party”, the other faces to whom I must also be in service (Levinas 1991, p. 16). These philosophical ideas challenge and remind me of my duty to turn towards the other others for they, too, have faces—literal and metaphorical—that demand my ethical responsibility. There is always more work to do, always other victims of the Killing Fields to whom I am also obliged.

6. Closing Reflections—Opening Considerations for the Future

My family and I inherit an irrevocably fractured genealogy from the Killing Fields. Its executors and executioners have robbed us of certain genealogical sources of knowing who we are, forcing us to look elsewhere to understand our be(com)ing. For me, philosophy has been a treasure trove for making sense of my relationships with those who were forced into the labor communes and, particularly, those who never returned. Philosophy, as unfolded here, is itself a form of postmemory, enabling a living connection to—and deeper understanding of—traumatic experiences of the Killing Fields that preceded my birth but nevertheless shape my be(com)ing.

The stories and philosophy inherited from my ancestors teach me to view life after the Killing Fields as relational and premised on ethical-political responsibility. I am always-already fractured from within, like the Yin-Yang symbol. I am not self-sufficient but come into being in relation to the other. I must learn to live with the other and with my foreignness to myself, exacerbated by the aftermath of the Killing Fields. I have learned that this foreignness is the source of my ethical-political responsibility to the other, unlike the Khmer Rouge who believed that the other is expendable. I am held captive by the other, bound to them by an obligation to act righteously and with generosity to their irreplaceable face that adorns our worlds. I must justify myself to others, for my conduct has implications not only for my face but also—most critically—those of others. I must strive to be a better human being and be generous even in the face of the Khmer Rouge’s barbaric behavior—that is, to be human in the face of actions that are inhumane.

This paper shines light on one of the darkest decades in human history, from which humanity appears to suffer a collective amnesia. The paper constitutes my initial attempts to preserve and make sense of my genealogy. I hope the testimonies and ideas presented here will serve as a lasting memorial to members of my family, and to the sufferings they endured for my present and future. This paper is a cenotaph in lieu of gravesites for those whose final resting places remain a mystery. The relational, ethical-political philosophy inherited from them underpins my work as a writer-thinker and learner-teacher and the fabric of my being at large. I hope that this life that I have chosen to live is one where the sufferings of immediate survivors and the (assumed) deaths of others are not in vain. My ancestors live on posthumously through this lifework, survived by the traces left here and elsewhere (Dam 2018), and remind me of my ethical-political obligations to others. I hope that—through this exposition—I have given face to my ancestors and loved and preserved the face that they have gifted me.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as the study is a personal, family history project conducted outside of my current institution.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from my father to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Helene Connor for her conception of the Special Issue in which this paper appears and for her generous restoration of the last remaining photograph of some of my ancestors. Heartfelt thanks to Frances Hancock and Rose Yukich, who provided valuable comments on numerous drafts of this paper. I have also benefitted greatly from comments provided by Te Kawehau Hoskins and the three anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- BBC. 2008. ‘Killing Fields’ Journalist Dies. BBC. Available online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/7321560.stm (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Boyden, Jo. 2003. The moral development of child soldiers: What do adults have to fear? Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 9: 343–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buncombe, Andrew. 2009. Khmer Rouge Chief: Babies Were ‘Smashed to Death’. The Independent. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/khmer-rouge-chief-babies-were-smashed-to-death-1700196.html (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Campbell, Charlie. 2015. Cambodian Guards Drank Wine with Human Gallbladders, Says Genocide Survivor. Time. Available online: https://time.com/3677753/human-gallbladder-wine-cambodia-khmer-rouge/ (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Capra, Fritjof. 2010. The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels Between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism, 5th ed. Boston: Shambhala Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Caswell, Michelle. 2014. Archiving the Unspeakable: Silence, Memory, and the Photographic Record in Cambodia. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, David. 2008. Cambodia deals with its past: Collective memory, demonization and induced amnesia. Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 9: 355–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, David. P., Ben Kiernan, and Chanthou Boua, eds. 1988. Pol Pot Plans the Future: Confidential Leadership Documents from Democratic Kampuchea, 1976–1977; New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies. Available online: https://www.eccc.gov.kh/sites/default/files/documents/courtdoc/00103989-00104170_E3_735_EN.TXT.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Chigas, George, and Dmitri Mosyakov. n.d. Literacy and education under the Khmer Rouge. Yale University Genocide Studies Program. Available online: https://gsp.yale.edu/literacy-and-education-under-khmer-rouge (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Ciorciari, John D. 2006. Introduction. In The Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Edited by John D. Ciorciari. Phnom Penh: Documentation Center of Cambodia, pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cruvellier, Thierry. 2018. The Master of Confessions: The Making of a Khmer Rouge Torturer. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dam, Lincoln. 2018. Love and politics: Rethinking biculturalism and multiculturalism in Aotearoa/New Zealand. In Mana Tangatarua: Mixed Heritages, Ethnic Identity and Biculturalism in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Edited by Zarine L. Rocha and Melinda Webber. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Deth, Sok Udom. 2009. The geopolitics of Cambodia during the Cold War period. Explorations 9: 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Di Certo, Bridget. 2012. Buddhist Monks Disrobed to ‘Survive’ Khmer Rouge. Phnom Penh Post. Available online: https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/buddhist-monks-disrobed-survive-khmer-rouge (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Etcheson, Craig. 2004. The Cambodian genocide. In Teaching About Genocide: Issues, Approaches, and Resources. Edited by Samuel Totten. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing, pp. 169–79. [Google Scholar]

- Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. n.d. Who Has Been Prosecuted? Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. Available online: https://www.eccc.gov.kh/en/who-has-been-prosecuted (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Farquhar, Sandy, and Esther Fitzpatrick. 2019. Innovations in Narrative and Metaphor: Methodologies and Practices. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Guy Oliver, and Tony Fang. 2008. Changing Chinese values: Keeping up with paradoxes. International Business Review 17: 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Arthur. 2010. Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-Narratology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, Claire, and Bill Rolston. 2009. The burden of memory: Victims, storytelling and resistance in Northern Ireland. Memory Studies 2: 355–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, Frances. 2019. ‘Who said this?’ Negotiating the ethics and politics of co-authorship in community text-making. In Innovations in Narrative and Metaphor: Methodologies and Practices. Edited by Sandy Farquhar and Esther Fitzpatrick. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hannum, Hurst. 1989. International law and Cambodian genocide: The sounds of silence. Human Rights Quarterly 11: 82–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuveline, Patrick. 2001. The demographic analysis of mortality crises: The case of Cambodia, 1970–1979. In Forced Migration & Mortality. Edited by Holly E. Reed and Charles B. Keely. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, pp. 102–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, Alexander Laban. 1998. Why did you kill? The Cambodian genocide and the dark side of face and honor. The Journal of Asian Studies 57: 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, Marianne. 2012. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Eva. 2005. After Such Knowledge: A Meditation on the Aftermath of the Holocaust. London: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- International People’s Tribunal 1965. 2016. The Cambodian Genocide. Available online: https://www.tribunal1965.org/en/the-cambodian-genocide/ (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Kavoori, Anandam. 2016. The most peaceful place on Earth. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies 18: 116–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, Ben. 2001. Myth, nationalism and genocide. Journal of Genocide Research 3: 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, Ben. 2002. Introduction: Conflict in Cambodia, 1945–2002. Critical Asian Studies 34: 483–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, Ben. 2004. The Cambodian Genocide, 1975–1979. In Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts, 2nd ed. Edited by Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons and Israel W. Charney. New York: Routledge, pp. 339–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan, Ben. 2008. The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power and Genocide in Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–1979, 3rd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Komin, Sunatree. 1990. Culture and work-related values in Thai organizations. International Journal of Psychology 25: 681–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1969. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1991. Otherwise Than Being or Beyond Essence. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Liev, Man Hau. 2008. Adaptation of Cambodians in New Zealand: Achievement, cultural identity and community development. Ph.D. thesis, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Liev, Man Hau, and Rosa Chhun. 2015. Cambodians—Immigration: Refugees and Resettlement. In Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Available online: https://teara.govt.nz/en/cambodians/page-1 (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Mam, Teeda Butt. 1999. Worms from our skin. In Children of Cambodia’s Killing Fields: Memoirs by Supervisors. Edited by Kim DePaul. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Persons, Larry Scott. 2008. The anatomy of Thai face. MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities 11: 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phnom Penh Post. 2018. ‘That Day We Went to Hell Alive’: Remembering the Fall of Phnom Penh. Available online: https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/day-we-went-hell-alive-remembering-fall-phnom-penh (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Pilger, John. 2000. How Thatcher Gave Pol Pot a Hand. The New Statesman. Available online: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/politics/2014/04/how-thatcher-gave-pol-pot-hand (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Shivakumar, M S. 1998. Pol Pot: Death deprives justice. Economic and Political Weekly 33: 952–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sterckx, Roel. 2020. Chinese Thought: From Confucius to Cook Ding. London: Pelican Books. [Google Scholar]

- The Killing Fields. 1984. Roland, Joffé, dir. London: Goldcrest Films. [Google Scholar]

- Tryner, James A., and Stian Rice. 2015. To live and let die: Food, famine, and administrative violence in Democratic Kampuchea, 1975–1979. Political Geography 52: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukosakul, Margaret. 2003. Conceptual metaphors motivating the use of Thai ‘face’. In Cognitive Linguistics and Non-Indo-European Languages. Edited by Eugene H. Casad and Gary B. Palmer. Hawthorne: De Gruyter, pp. 275–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ukosakul, Margaret. 2005. The significance of ‘face’ and politeness in social interactions as revealed through Thai ‘face’ idioms. In Broadening the Horizon of Linguistic Politeness. Edited by Robin Tolmach Lakoff and Sachiko Ide. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 117–25. [Google Scholar]

- Unger, Daniel. 2003. Ain’t enough blanket: International humanitarian assistance and Cambodian political resistance. In Refugee Manipulation: War, Politics, and the Abuse of Human Suffering. Edited by Stephen John Stedman and Fred Tanner. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, pp. 17–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wyke, Tom. 2016. Khmer Rouge Cannibals Executed Woman Prisoner then Cut out HER liver and Ate It, Witness Tells Court. Daily Mail Australia. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3469367/Witness-recounts-Khmer-Rouge-cannibalism.html (accessed on 24 November 2020).

| 1 | Histories are themselves stories that are inevitably partial (incomplete and subjective) and fluid. My representation of the word “(hi)stories” seeks to embody this understanding. |

| 2 | “The Killing Fields” was coined by Cambodian journalist Dith Pran, who survived the genocide and was the subject of the 1984 film of the same name (BBC 2008; The Killing Fields 1984). The term typically refers to killing or grave sites from the Khmer Rouge regime. However, in this paper, I follow my father’s interpretation by referring to the Cambodian genocide in totality as “the Killing Fields”. My father considers the fields where he and other Cambodians were imprisoned and forced to work under Khmer Rouge rule as, themselves, killing fields—sites where many died (in part) as a result of excruciating labor. The term “killing fields” is also now used to describe violence and genocide in other contexts, such as in Rwanda, for example. |

| 3 | Kang Kek Iew (died of natural causes), Nuon Chea (died of natural causes), and Khieu Samphan. |

| 4 | Ieng Sary and Ieng Thirith. |

| 5 | My representation of the word “be(com)ing” seeks to convey that being is also a process of becoming. |

| 6 | In this paper, I use the terms “stories” and “testimonies”, and “storytelling” and “narrative work” interchangeably to reflect the entanglement and interplay of the past and the present. As a child, I knew the accounts shared by my parents simply as stories and the practice of sharing these accounts as storytelling. Only in recent years, through academia, have I come to understand my parents’ stories and the practice of storytelling more specifically as testimonies and narrative work. |

| 7 | I use the conjunction of opposites here as a device to draw readers’ attention to the ambiguities, uncertainties, tensions, interminability, and relationality of the stories told here. |

| 8 | See Chandler et al. (1988). |

| 9 | Through other research, we are able to estimate that my father and his family boarded buses on 8 July 1979 or thereabouts (Unger 2003). |

| 10 | For more on the Yin-Yang philosophy, see (Capra 2010; Faure and Fang 2008; Sterckx 2020). |

| 11 | For more detailed accounts of Thai considerations of the face, see (Komin 1990; Persons 2008; Ukosakul 2003, 2005). Levinas (1969, 1991) also argues that the face of the other represents an ethical demand. The convergences and divergences of Levinasian and Thai understandings of the face and ethical responsibility are the subject of my forthcoming work. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).