2.1. Sweden—A Multiethnic and Multiracial Country

Except for five historical minority groups—the indigenous Samis, the Finns, the Tornedalians, the Jews and the Roma (Travellers)—Sweden was a rather ethnically and racially homogenous country compared to most other Western countries until the end of the 20th century. Sweden was rather a country of emigration until the 1950s when labor immigration to Sweden from other Nordic and European labor became prominent. Sweden today has transformed into a multiethnic and multiracial nation as a result of the non-European migration flows that started in the mid-1970s onwards, and increased in particular after the end of the Cold War, consisting mainly of refugees and their family members.

Today, Sweden is a country of immigration. Immigration from the non-Western world has increased steadily in the past decades, with 2015 being the highest ever recorded immigration year. In 2016, some 18 per cent of the 10 million residents of Sweden were born abroad. In total, 5 per cent of those born in Sweden had two foreign-born parents, while another 7 per cent were the children of one Sweden-born parent and one foreign-born parent (Statistics Sweden). As both the category of immigration and the country of origin of the immigrants have shifted, Sweden has faced different challenges concerning integration and discrimination.

With regards to the number of residents under 18 years of age in Sweden’s three largest cities, the ethnic and racial diversity is evident and is on pair with countries like the UK, France and the Netherlands. At the end of 2016, a total of 54 per cent, 49 per cent, and 36 per cent of all inhabitants in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö respectively had two parents who were born in Sweden, while 29 per cent, 35 per cent, and 47 per cent had a foreign background have foreign backgrounds (that is, either themselves or both of their parents were born abroad). In all three cities, around 17 per cent were born in Sweden, with one parent born in Sweden and one parent born outside Sweden (

Statistics Sweden 2017). In 2015 a record high 163,000 asylum seekers arrived in Sweden whereof the majority received residency permit, which means that the racial and ethnic landscape of the country will continue to be affected in the coming future.

With the fast changing racial and ethnic landscape of Sweden, integration of the newly arrived and problems of discrimination and socioeconomic inequality faced by migrant groups are evident in Sweden. Swedish researchers have tried to explain and understand the increasing inequalities between the white majority and the non-white minority through the concepts of ethnicity and culture. However, during recent years voices have been raised claiming that ethnic and cultural differences are not sufficient to explain the levels of racial segregation and discrimination in Sweden (see e.g.,

Hübinette 2017;

Hübinette and Wasniowski 2018;

Osanami Törngren 2015). Inspired by critical race and whiteness studies in the English speaking countries, these scholars argue that it is not only the individuals’ ethnicity and culture that matter but also how they are perceived racially and how visible phenotypical differences shape the definitions of Swedishness and non-Swedishness (

Hübinette and Lundström 2011;

Kalonaityté et al. 2007;

Khosravi 2006;

Mattsson 2005;

Runfors 2006). These scholars demonstrate in their studies that non-whites who grow up and live in Sweden are rarely seen and treated as being “fully Swedish” due to the strong legacy of equalizing Swedishness with whiteness.

2.2. Race, Ethnicity, Whiteness and Transracial Families

Race is a product of scientific thought that is culturally, socially, and historically determined. Up to the late 19th to the early 20th century, European researchers, including prominent Swedish scholars, were engaged in studies dividing human beings into different races. Initially, this was conducted, supposedly, without any racist implications. However, a racist ideology was introduced into the division of human “races” by names such as Arthur de Gobineau and others who promoted social Darwinism. Inspired by social Darwinism, cultural, social, and moral differences were explained by biological racial differences which entailed hierarchical ideas of superiority and inferiority. Swedish involvement in this development of the idea of race and so-called race science was substantial. In 1922, Sweden established the world’s first state run and state funded race science institute.

Maja Hagerman (

2006) has pointed out that through the dissemination of so-called scientific knowledge of race, ordinary Swedes were taught to be able to differentiate between the white Swedish majority population i.e., “the Nordic race”, and those inhabitants that were deemed to be inferior and undesirable. During the first half of the 20th century, it was the Samis, the Finnish speakers, the Roma and the Jews who were often regarded to be non-Swedish and not fully white, therefore preventing further mixing with the majority Swedes was regarded as being in the national interest national interest (

Hagerman 2006). The legacy of Sweden’s racialized nation-building process during the last century even excluded representatives from historical minorities that today would pass as white such as the Finnish-speaking minority.

Interestingly enough, Sweden was also one of the first countries to dismiss the ideas of race science after World War Two and Swedish scholars were involved in the various declarations on race made by UNESCO in the 1950s. These declarations affirmed that there were no superior or inferior human races (

Jacobsson 1999).

Even though the country was heavily involved in the development of race science, Swedes and Swedish society are reluctant to admit that racism and discrimination exist and ideas of race play a part still today in Sweden. Within the critical race and whiteness studies, this attitude towards race is known as color-blindness which Ruth Frankenberg has described as “a mode of thinking about race organized around an effort to not ‘see’, or, at any rate, not to acknowledge, race differences” (

Frankenberg 1993, p. 142). While

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (

2010) sees color-blindness as a specific expression of racism which he calls color-blind racism,

Alana Lentin (

2018) analyzes color-blindness as a reflection of a “not racism”-attitude within the context of an hyperindividualistic and ahistorical Western culture which is becoming increasingly blind to power asymmetries. David Theo Goldberg conceptualizes color-blindness as “antiracialism” and defines; “Antiracialism is to take a stand, instrumental and institutional, against a concept, a name, a category, a categorizing (

Goldberg 2009, p. 10). The Swedish version of color-blindness is arguably closest to Goldberg’s antiracialism as Sweden also became the first country to abolish the concept of race in the beginning of the 2000s. This is similar to what Jan-Paul Brekke and Tordis Borchgrevink (

Brekke and Borchgrevink 2007) write about the ambiguous categorization of people in Sweden according to skin color. They state, “[t]he sensible approach to the issue, which is also the official Swedish approach, is to consider color irrelevant to the appraisal of an individual” (

Brekke and Borchgrevink 2007, p. 79). The authors suggest that Swedes generally do not consider skin color to be relevant or crucial to an individual’s characteristics or value.

Generally speaking, Swedes understand themselves as being democratic, liberal, equal, tolerant and individualistic. Moreover, they highly value antiracism, gender equality, secularism and universalism. It is not only that Swedes understand themselves as such but also that they express and practice these values to a large extent (

Johansson Heinö 2009). These core values, which are also seen as Swedish values, are reflected in the Swedish integration policy which is based on a color-blind ideology that revolves around the idea that everybody is equal regardless of his or her background (

Schierup and Ålund 2010). The principles of equality, freedom of choice, and partnership—which correspond to the principles of liberal modernity in its Swedish version—have formed the basis for Swedish integration policy since 1975. The latest integration reform, made in 2009, states that the objectives of integration are equal rights, equal obligations and equal opportunities for all inhabitants of Sweden regardless of ethnic and cultural background (

Johansson Heinö 2009). Access to the labor market is a central feature of Swedish integration policy, which derives from a strong belief that the labor market is color-blind and rational (

Johansson Heinö 2009;

Mattsson 2005;

Rakar 2010). It is a paradox that color-blindness is so embedded in the integration policy of Sweden, considering that the country at the same time officially embraces multiculturalism. Swedish multiculturalism has for example centered around the idea of “positive” measures, that is providing minorities the right to state support rather than promoting “negative” measures that give minorities the right to exemptions from state intervention (

Borevi 2013). However as Swedish multiculturalism is based on the idea that everybody should be able to participate in Swedish society and that all should be treated equally, multiculturalism can co-exist with Swedish color-blindness.

The antiracial attitudes and color-blindness have had such a deep impact on Sweden that the very concept of race has been erased completely from official language of public administrations. A parliamentary decision in 2001 to abolish the concept of race from public language was followed by the removal of the word “race (ras)” as the basis for discrimination in 2009 (

Hübinette and Hyltén-Cavallius 2014). In 2014, the Swedish government announced that the last vestiges of the word race should be removed from all existing legislation in Sweden (

Hambraeus 2014). Even in everyday language, the word is avoided, and the bulk of the antiracist movement in Sweden of today refuses to use the word race. Most Swedes associate the concept of race and racial groups with biology and not how the concept is used to describe a socially constructed category and groups of people who experience inequality. Even though the contemporary and postmodern way of understanding race is far from the understanding of the biological race, the term has such a negative connotation in Sweden that people are afraid to use it, fearing that it will be misunderstood or misused. Hübinette and Hyltén-Cavallius write:

Colorblindness in the Swedish contemporary context means that for many Swedes it is even difficult to utter the word “race” in everyday speech, and it is equally uncomfortable to talk about white and non-white Swedes.

Despite this Swedish color-blind discourse which might well be the most extreme in the world, it is clear that the social reality and meaning of race—that is, the idea of race and stereotyping of, and prejudice against certain groups of people—lives on even in contemporary Sweden. In this article, we understand race in contemporary Sweden as a socially constructed idea evoked by perceived visible phenotypical differences. Race is not a biological reality but a social reality, because racism and discrimination based on the idea of race still prevail widely. Race as a social construct means that the meanings and categories of race are constructed in a specific context, and it varies according to place, society, and over time. Although race is a social construction and racial categories and understandings of race vary according to place, society, and over time, race is socially real for many people and “affect[s] their social life whether individual members of the races want it or not” (

Bonilla-Silva 1997, p. 473). Race is a social reality because the lives of the people who are categorized as different according to their visible differences are manifested through discrimination and racism.

Ethnicity, which is the more preferred term in Sweden is defined in various ways, does not always capture the reasons of inequality and discrimination. Ethnicity is built on the notion of shared culture (e.g.,

Cornell and Hartmann 2007;

Fenton 2003). However, as

Cantle (

2005) argues, an ethnic difference may not explain a difference in culture, unless culture is treated and perceived as something fixed and essential to each ethnic group. Ethnicity can also be symbolic (

Gans 1979) and people may pick and choose certain aspects of culture. Ethnicity should therefore be understood as an identification of cultural origin and heritage independent of if the individuals practice the culture or not. Many researchers and ordinary people alike tend to conflate the concepts of race and ethnicity. On a general level, the two concepts are distinct from each other as race is perceived to be visible while ethnicity is not always visible. Race is also often an ascribed category while ethnicity is often an acquired category by the individuals of a certain group.

To sum up, Sweden is an interesting case and context in relation to issues of race and whiteness as the country played an important role in the scientific construction of race, as it is today one of the world’s more or even most color-blind countries. The majority of Swedes are harboring relatively strong antiracist and progressive opinions and values while at the same time Swedishness is still very much equal to whiteness.

2.3. Study 1: The Stranger

The first study which this article is based on analyzes official norms and values surrounding the family as reflected in Swedish transnational adoption policies. By investigating policy texts related to transnational adoption, the study seeks to understand changing perceptions of what is considered natural, normal, good and ethically sound in relation to kinship and family building. The empirical data consist of so-called Official Government Reports on transnational adoption published between 1967 and 2009. Official Government Reports are interdisciplinary and cross-sectorial efforts to prepare the government’s legislative proposals, thus reflecting different views on a certain political issue, but with the overarching aim to obtain a consensus and present a set of policy proposals and legislative recommendations. For this study, six reports were selected for in-depth analysis. The theoretical framework of the study combines insights from feminist and postcolonial studies to explore how notions of family, kinship, race, ethnicity, national belonging and origin influence and are influenced by political rhetoric and practice. Consequently, the methodological approach is concerned with deconstructing knowledge and power relations. The study is performed as a governmentality and discourse analysis, which assumes that the law has a special position as a normative statement in a society and thereby affects all inhabitants in a country. By studying Official Government Reports and the law, it is not only possible to get a deeper understanding of the prevailing norms and values of a society, but also an understanding of in which direction the government is steering a nation and its citizens. For example, by indicating what is normal and what is not, or who belongs and who does not, the law both reflects and structures how people think and act (

Jonsson Malm 2011).

The results of the analysis show that the attitudes towards transnational adoption were complex and changed between 1967 and 2009. The attitudes were influenced by the dramatic increase in transnational adoptions in the 1960s and 1970s, which made Sweden the world’s leading adopting country per head in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as by the gradual decrease in the number of adoptions from the 1990s and onwards, which has continued until today. During this period of time, because of the almost lack of domestic children available for adoption due to a combination of women’s liberation, the legalization of free abortion and the de-stigmatization of single and unmarried mothers, thousands upon thousands of foreign-born children were adopted to Swedish homes. Almost all of these adoptions involve white parents living in Sweden and non-white children from countries in the Global South. In total, about 60,000 foreign-born children have been adopted to Sweden and out of whom well over half derive from Asia and mainly from East Asia (with South Korea and China being the biggest countries of origin) as well as from South Asia, while the rest come from Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, the Middle East and partly also from Eastern Europe. According to Statistics Sweden, around 60 percent of transnational adoptees derive from Asia, 25 percent from South America, 10 percent from Europe and 5 percent from Africa. This mixing of nations and races on a mass scale given the small population of Sweden plays a crucial role in the attitudes toward transnational adoption. The design of Swedish adoption policies is very much grounded on whether transnational adoptions are regarded as positive or negative. Three possible approaches were observed in the reports: an advocating attitude, an antagonistic attitude, and a pragmatic attitude. Advocates are positive to transnational adoption and want to increase the number of adoptions and facilitate the adoption process. Antagonists are negative towards transnational adoptions and see them as problematic and as something that should be limited or even prevented and prohibited. The pragmatics are to be found somewhere in between these two positions as they do not want to ban transnational adoptions, but they believe that the adoption industry must be regulated by strict legislation and that there should be no major increase in adoption cases (

Jonsson Malm 2011).

Furthermore, the analysis of the government reports also shows that between 1967 and 2009 the attitudes toward transnational adoption were expressed in different ways and had different degrees of influence on the legislation. In the beginning, there were strong opinions against transnational adoptions, with some arguments based in so-called race science. However, the government reports from that time were more concerned about the well-being of the child and feared that being adopted transnationally is not in “the child’s best interest”. The perceived problem had mostly to do with the child’s ethnic background and physical appearance. In the early government reports, the underlying assumption was that a child adopted from another country is different from white Swedish people in terms of culture and race and therefore would grow up as an “outsider” or a “stranger”, which could lead to social and emotional complications. Being different was not solely described as something negative, the adoptees were also appraised for their exotic looks and attributes, which some people found “interesting” and “fascinating”. However, the assumption was that most Swedes carry racist attitudes towards people who do not look like them. The answer to this problem, according to the reports, was a two-way solution: the adopted children should become “Swedish” and be assimilated into Swedish society, and the Swedes and the Swedish society should be “fostered to color-blindness” to facilitate this process (

Jonsson Malm 2011).

The reports’ pragmatic approach resulted in a more favorable legislation contributing to the increase in transnational adoptions in the 1960s and 1970s. During this period of time, adopting a child from a so-called developing country in the non-Western world was primarily regarded as a good act and as a form of humanitarian aid. The general opinion was that the child would always have a better life in Sweden than in its country of origin. That opinion started to change in the late 1980s, with raised concerns over the adoption industry’s role in child trafficking, and in the exploitation of the Third World. The decrease in the number of transnational adoptions, which took hold after the Cold War, is a complex issue and can partly be explained by nationalist sentiments and even anti-Western attitudes in many countries of origin and partly by a growing middle-class in many Asian and Latin American countries, as well as in some African countries, wanting to adopt the children that once were sent to the West. The decrease is also a consequence of a growing number of reproduction techniques, which has made transnational adoption more and more obsolete, such as egg and sperm donations and surrogacy arrangements (

Jonsson Malm 2011).

In the reports from the latter time period, the growing antagonistic attitudes towards transnational adoption were also related to changing attitudes towards the child’s right to know its origins, as stated in the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, which by many is interpreted as the child’s right to stay in its birth country. The reports refer to the adoptees’ so-called “psychological vulnerability”, which is assumed to be the result of their separation from their biological, ethnic, racial and national origin, which is described as “a trauma”. The solution is therefore to encourage the adoptees to affirm their ethnic origins by visiting their birth country and by seeking their roots instead of discouraging them to do so, which had more or less been the norm before the 1990s when nurture was seen as trumping nature. In that way, the adoptees would learn to accept that they are different from the majority Swedes, and they would embrace their dual ethnic identities, rather than being “fully” Swedish. Learning to live with this duality would help adoptee’s struggling with psychological distress. The idea that the adoptees’ psychological vulnerability could be caused or affected by racial discrimination is, however, dismissed thereby placing the responsibility for integration solely at the individual level rather than at the societal level. The underlying assumption is that race and racism is not an issue in today’s modern and multicultural Swedish society as the majority Swedes have, at least according to the government reports, been fostered to color-blindness (

Jonsson Malm 2011).

2.4. Study 2: Color-Blind Love?

The second study which this article is based on examines attitudes among white majority Swedes on interracial relationships including on dating, marrying, and having children with someone whose background is from Africa, Central/Eastern Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, South/East Asia, South/Western Europe, or Scandinavia. The study also investigates the attitudes towards having a relationship with non-white adoptees from Africa, Latin America and East Asia. The attitudes interracial relationships were examined by the way of a quantitative questionnaire, which was followed up with qualitative interviews with some of the questionnaire respondents. The survey was sent to 2000 randomly selected residents in the city of Malmö out of which 620 responded. Among these, 30 people were selected for a follow-up interview.

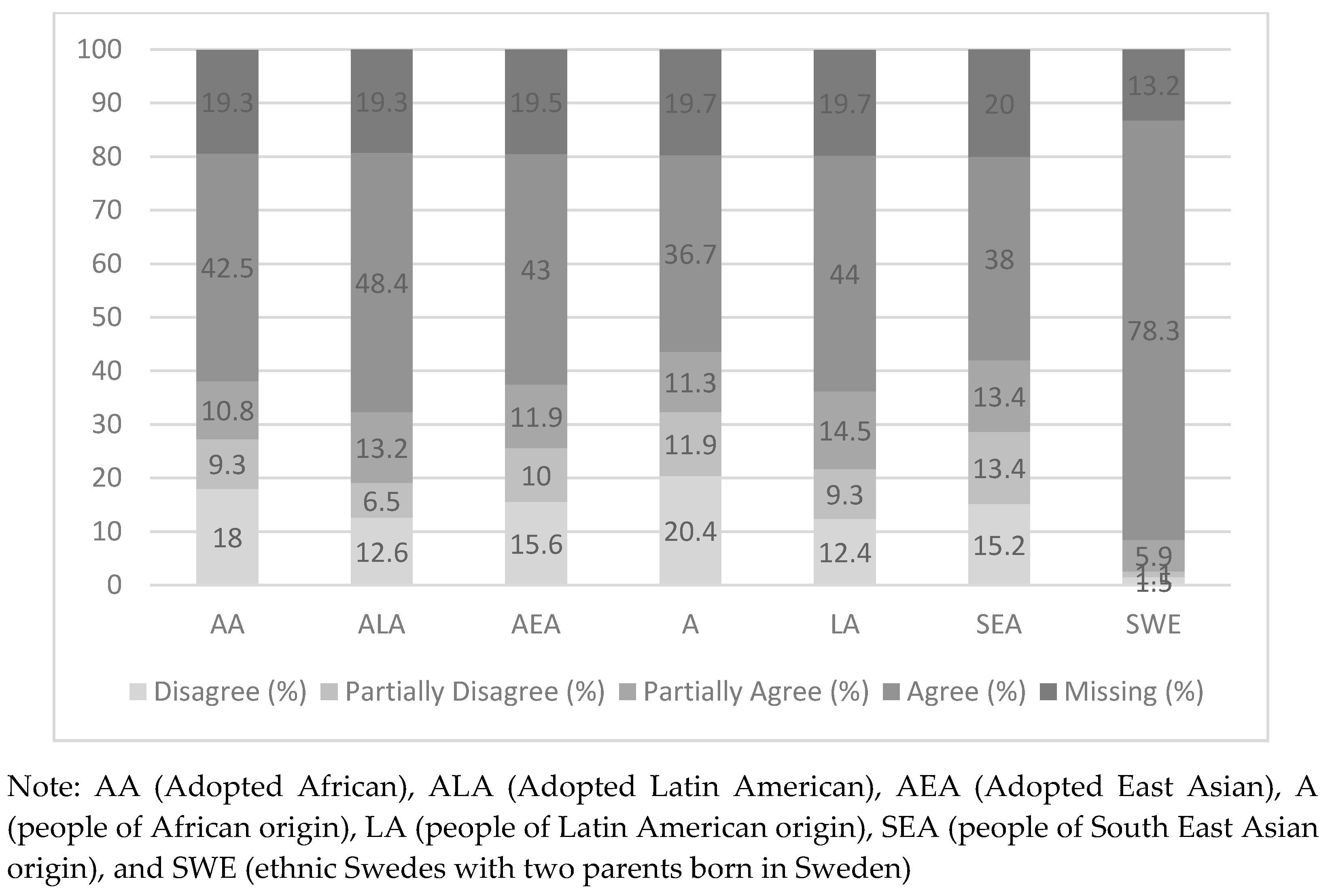

The survey and interview results show that the majority of the participants could imagine dating, marrying, or having children with someone with a different background than themselves. However, there was a clear hierarchical preference for different racial and ethnic backgrounds of the imagined partner (See

Figure 1). White Swedes preferred having intimate relationships with people with a background from Scandinavia, Western Europe, or Southern Europe. Thereafter, they preferred partners originating in Central/Eastern Europe and Latin America. Persons with a background in South/East Asia, Africa, and the Middle East were the least desired and preferred imagined partners. The attitudes towards non-white adoptees also showed an unexpected outcome: their desirability was based on their continent of origin as adoptees from Latin America were preferred the most in comparison to adoptees from East Asia. Adoptees from Africa were the least preferred as potential intimate partners.

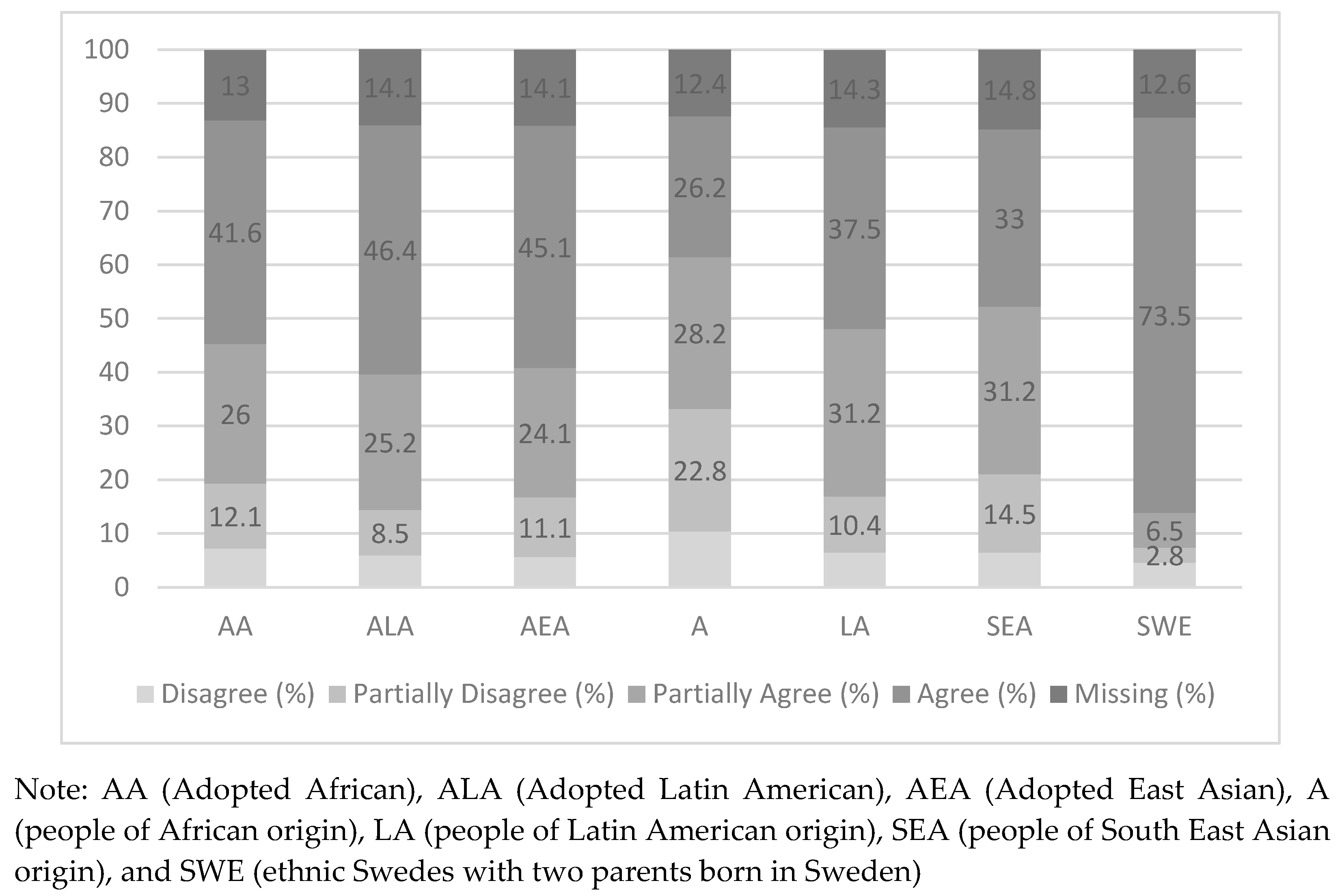

By comparing the attitudes towards non-white adoptees and the attitudes towards the equivalent immigrant groups who share the same continents or regions of origin, the differences in attitudes were not significant, while the differences were obvious and statistically significant between the attitudes toward non-white adoptees and white Scandinavians or other white Western European groups (See

Figure 2).

This result goes against the general Swedish perception that non-white adoptees are “like any other Swedes” and the fact that they are visibly different from white majority Swedes is officially seen as being of little significance. The importance of skin color and other racial markers is particularly prominent in the case of non-white adoptees, who all share the same culture as white majority Swedes (

Osanami Törngren 2011).

Furthermore, the majority of the survey respondents were positive to dating someone with a migrant background but they were at the same time less positive to be a part of a long-term and permanent relationship. When it came to childbearing, the answers were even more negative. The differences in attitudes towards dating and childbearing were statistically significant. As the interviewees suggested that children imply more responsibility, they were more reserved to having children with someone with a foreign background. However, the majority of the respondents answered that they would not react negatively if someone in their family or others in their close surroundings chose to live in a mixed marriage and interracial relationship. At the same time, they responded that not all relationships were seen as equally accepted in Swedish society at large and that a marriage with someone originating in South/East Asia, Africa, or the Middle East was less accepted than a marriage with someone originating in other regions and continents.

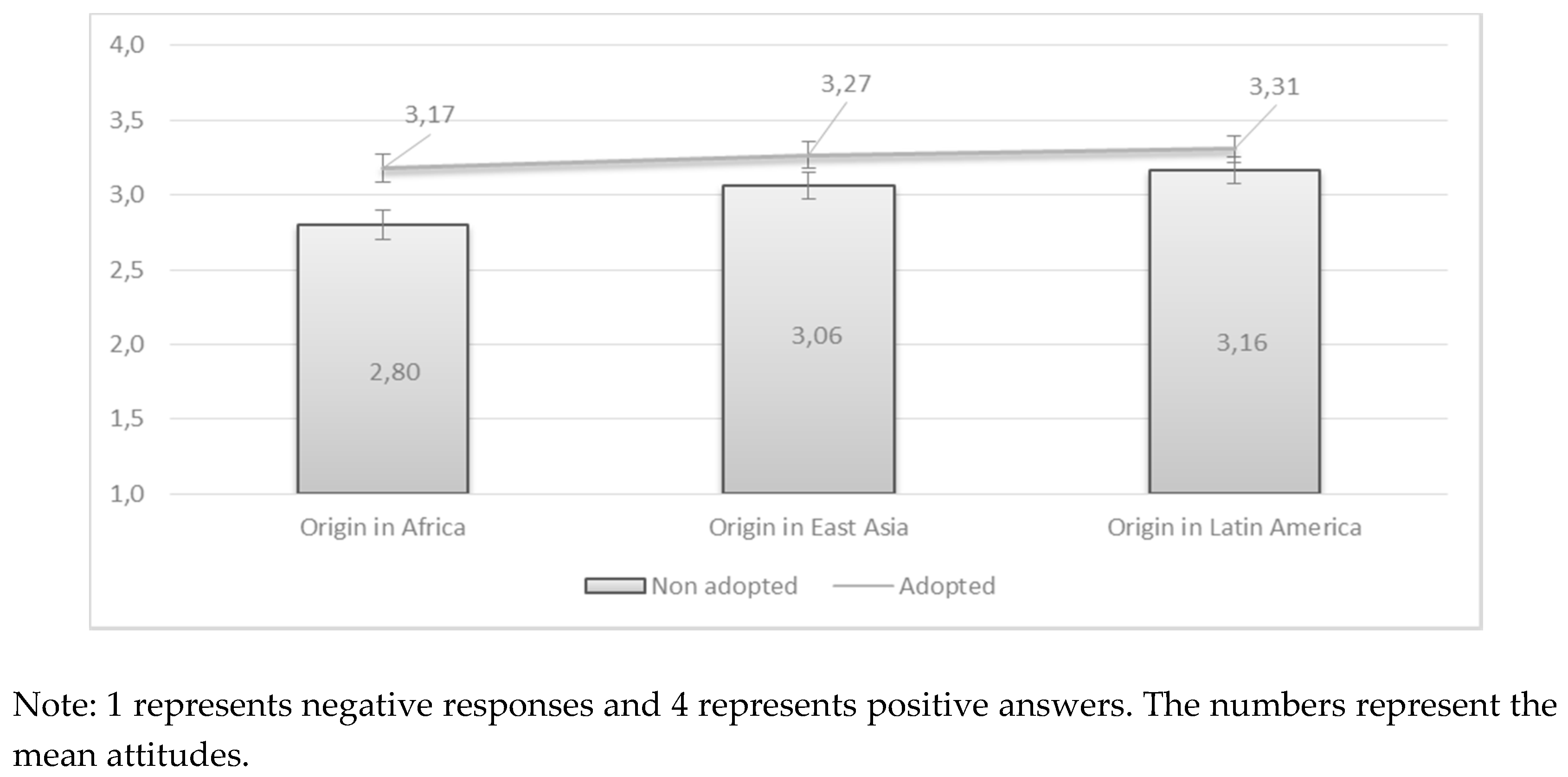

Relationships with adoptees were seen as more accepted in Swedish society than relationships with the corresponding immigrant groups (see

Figure 3). Contrary to the attitudes towards interracial marriage, there was statistically significant differences in the responses given towards non-white immigrant groups and non-white adoptees (see

Figure 4). This shows that there is on the whole a wider cultural acceptance of adoptees than of immigrants, and the responses reflect the color-blind idea that adoptees are Swedes (

Osanami Törngren 2011).

When speaking about mixed relationships, the interviewees’ choice of words and expressions strongly reflected their color-blind attitudes towards race as they had great difficulties to talk about skin color and other visible differences. In particular, they tended to highlight cultural differences that may or may not exist instead of talking about visible differences. Many interviewees stated that they preferred European partners because of cultural similarities, whereas they linked an origin from South/East Asia, Africa, and the Middle East to notions of cultural differences. Perceptions of gender equality were regarded as one particularly important cultural difference. The idea of the Swedes and of Sweden as being gender equal was contrasted with “other cultures” as being patriarchal and oppressing women. Also prominent in the interview material was the color-blind idea of making an individual choice as the interviewees tended to claim that a certain origin does not matter when it comes to love (

Osanami Törngren 2011;

Osanami Törngren 2018).