1. The Queerness of Genealogy

There is something queer about genealogy. It is often considered as a seemingly neutral method of identifying kinship and ancestry. Yet, the conventional practice of genealogy establishes a form of familial continuity that has historically been the prerogative of whiteness and which is still dominantly naturalized as heterosexual procreation. Miscegenation and homosexuality have thus traditionally posed a breach in the continuum of American family. In fact, until rather recently, racial mixing and queerness have constituted two fundamental taboos in the law of kinship. This applies in a literal sense because both taboos used to represent transgressions against legal codification of marriage and family in terms of anti-miscegenation policies until the US Supreme Court’s decision of

Loving v. Virginia in 1967 as well as with regard to heteronormative definitions up to

Obergefell v. Hodges in 2016. In a figurative sense, this legacy of prohibition extends into ongoing social rules. Because the institution of family functions as a site of ‘reproducing’ and transmitting a culture including its power hierarchies, racial mixing and queerness have often been demonized as threatening the nation by undermining its family structure (cf.

Hill Collins 1998).

In this article, I examine the ideological and aesthetic labor that goes into reconciling queerness and interraciality with genealogy, a practice that originally stands in an antithetical relation to these two categories. I do so by turning to a new development of autobiographical works that establish narratives of origin across the color line as well as beyond the longstanding benchmark of heterosexual reproduction. A number of predominantly white queer parents of black adoptees have turned their family histories into children’s read-along books as a medium for pedagogical empowerment that employs first-person narration in the presumable voice of the adoptee. My analysis understands these objects as verbal-visual narratives of family formation that render intelligible a conversion from differently racialized strangers into kin. I examine the mode of narration as a dynamic of ‘adoptee ventriloquism’ that reveals more about adult desires of queers for familial recognition than about the needs of their adopted children.

In order to unfold the cultural work that these narratives perform across a heteronormative color line, I first contextualize them against the backdrop of a larger rise of multiracialism whose struggle for public acknowledgment has implicitly marginalized queerness. In addition, I briefly sketch a ‘genealogy of genealogy’ in the US. The documentation of one’s family history has emerged as a biologistic instrument in the service of nationalist white supremacy. Since the 1970’s, however, genealogy has expanded formally as well as ideologically and also seen multiculturalist and queer appropriations. Along these lines, Americans increasingly construct a sense of personal and familial beginnings through everyday practices such as autobiographical storytelling, from Barack Obama’s bestseller memoir Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance to the picture books on gay adoption that I discuss in this article. My engagement with this material is invested in two main objectives. On the one hand, I aim to make space for queerness in an often-unmarked heteronormative framework of genealogy, multiracialism, and children’s literature. On the other hand, I critically investigate what might remain in the ‘closet’ for queer interraciality to ‘come out as family.’ I illustrate my theses via three picture books that each represent a different, significant type in the formation of gay interracial familiality. I move my analytical lens from formalized to non-formalized adoption in the US and end by focusing transnational adoption to show how queer genealogies not only stretch across the color line into children’s literature, but also beyond the Atlantic in unexpected ways.

2. The Reproductive Utopia of Multiracialism

The 1990’s witnessed a paradigm shift toward the cultural legitimization of interraciality in the US. This crossover manifested itself, for instance, in the formation of multiracial associations and activism, in the reform of the census that now allows respondents to check multiple racial affiliations, and it showed in the unprecedented rise of autobiographical works that address interracial kinship. Perhaps most prominently, it registered in Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign that translated his interracial background from a taboo of miscegenation into the alleged fulfillment of America as a democratizing melting pot:

“I am the son of a black man from Kenya and a white woman from Kansas. … I am married to a black American who carries within her the blood of slaves and slaveowners—an inheritance we pass on to our two precious daughters. I have brothers, sisters, nieces, nephews, uncles and cousins, of every race and every hue, scattered across three continents, and for as long as I live, I will never forget that in no other country on Earth is my story even possible.”

Obama’s campaign, as well as that of the multiracial movement, frequently sought to authorize interraciality by turning it from one “American exceptionalism” (

Sollors 2000, p. 12) into another. Whereas miscegenation once represented a longstanding taboo and even a supposed threat to national integrity, it was now promoted as the realization of the civil religious myth of the melting pot. The heterosexual interracial family became envisioned as a transcendent site of intimacy that could be extended as a model for national reconciliation. In particular, the mixed race(d) child—previously conceptualized as a notoriously ‘tragic mulatto/a’ in American thought—was idealized as a “harbinger of a transracial future” (

Nyong’o 2009, p. 176) who would function as a bridge across the historic color line. This scenario is embedded in multiracialism’s own proclaimed genealogy, the progressive and revolutionary origin story it tells about itself. This foundational narrative begins in 1967 with the legalization of heterosexual interracial marriage in

Loving v. Virginia and leads to a “biracial baby boom” whose supposed melting-pot effect will eventually reduce racial hierarchies and usher in a more egalitarian era (cf.

Root 1999, pp. xiii–14).

1In this fashion, the interracial family has been celebrated, time and again, as an allegory of national unity, although it is just as much one of exclusion and historical obfuscation. Not only does the metaphor of the melting pot eclipse the violent conditions of racial mixing in America’s past, but it also represents a biologistic program that discounts those who do not participate in a reproductive endeavor of national belonging. From this critical vantage, it does not come as a surprise that affirmations of queerness have been conspicuously absent from mainstream self-representations in the multiracial movement, until recently. In a trenchant diagnosis about the genesis of multiracialism, Tavia Nyong’o writes, “By aligning itself with the heterosexual norm racial hybridity seeks to cast off its own history of stigma” (

Nyong’o 2009, p. 177). Yet, this absence of queerness also goes beyond respectability politics. Multiracialism’s aspiration toward cultural legitimacy has dominantly revolved around the family as a concept of selfless, child-centered care and biological reproduction, a norm that has traditionally been conceived in a binary opposition to queerness. In particular, gay men have been hegemonically constructed as a “nonprocreative species,” pathologized as narcissist, hypersexualized, pedophile as well as associated in proximity to premature death through a legacy of AIDS (cf.

Weston 1991, p. 23). In tacit ways, queerness in the hegemonic cultural order is imagined as a “culture of death” (

Edelman 2004, p. 39). It negates the familial continuity of reproductive life that builds the foundational premise of standard genealogical practices.

3. (Dis)Continuities of Genealogy in America

The practice of genealogy remains extraordinarily popular in US culture because of simultaneous mechanisms of continuity and change in the politics of documenting and narrativizing family history. Across various revisions that I sketch in this section, one fundamentally conservative element has persisted in mainstream designs of genealogy, biological lineage as an authoritative referent of individual, social status. As Julia Watson puts it, “Its fundamental assumption is categorical: Humans are defined by who and where we are ‘from’” (

Watson 1996, p. 297). This logic becomes explicit in the title of the genealogy show

Who Do You Think You Are (2010–2018) and it governs popular formats with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., such as

Finding Your Roots (2012–2019) or

Faces of America (2010), where the revelation of distant blood lineage is staged as a spectacle that (re)defines self-worth (cf.

Rak 2017, pp. 7–11).

The popularity of genealogy in the US context partially lies in a compensatory function. The practice counteracts a “radical discontinuity of [the] American experience” that results from forced and voluntary transoceanic migration as well as inland mobility, colonial genocide, displacement, and enslavement within the imperial project of ‘America’: “It establishes ‘descent’ where it is most in question” (

Watson 1996, p. 299). An ideological investment in genealogy may seem to contradict the country’s foundational ideal of overcoming a lineage-based system in favor of an egalitarian democracy. And as historian François Weil shows, genealogical activities were initially criticized by politicians in post-revolutionary America as an illegitimate identification with the values of the British Empire (cf.

Weil 2013, pp. 42–47). However, research has reconstructed three subsequent phases in the “Americanization” (

Weil 2013, p. 41) of this practice.

In the first phase over the first half of the nineteenth century, genealogy becomes re-conceptualized as participating in a national enterprise when public figures and institutions urge citizens to record and study their ancestry to preserve American history. The aristocratic custom of genealogy is thus seemingly democratized as “a patriotic hobby” (

Jackson 2014, p. 8). In fact, commercially produced family tree templates from this era usually begin with an immigrant ancestor in the colonial era as the trunk so that one’s lineage “becomes temporally and spatially coextensive with the emergent United States” (

Jackson 2014, p. 10). On the one hand, such genealogical inscriptions of citizenship operate on an ableist-heteronormative principle where unmarried and non-reproductive individuals are represented as “stumps or branches that break off precipitously” (

Jackson 2014, p. 60). On the other hand, genealogy at large is embedded in a project of white supremacy that denies familial recognition to Native Americans and African Americans whose ties of kinship and descent are systematically destroyed through enslavement and removal.

A supremacist framework also shapes a second phase in the aftermath of the Civil War where genealogical pedigree functions as evidence of national affiliation in synonymy with racial purity. Ancestral documentation here serves as a consolidation of whiteness that works in concert with other legal, cultural, and social forms of anti-black oppression and exclusion that replace the institution of slavery. Likewise, in the first half of the twentieth century, genealogy becomes a tool of nativist and eugenic ideologies as well as of white lineage-based organizations (cf.

Weil 2013, pp. 78–142).

Genealogy’s third phase begins with multiculturalist appropriations in the 1970’s (cf.

Weil 2013, pp. 180–218). This paradigm shift is usually associated with the success of Alex Haley’s family saga

Roots (1976) and its television adaptation (1977), which reconstructs an African American family heritage across the disruptions and fissures of enslavement and the Middle Passage.

Roots has not only been identified as a catalyst for a renewed and enduring interest in genealogical research across various racial, ethnic, and class communities (cf.

Jacobson 2006;

Hirsch and Miller 2011). For life writing scholar Watson,

Roots anticipates a development in which the function of genealogy has been increasingly transferred into autobiographical storytelling since the 1990’s as a form of “autobiographical pedigree”: “a collective record that establishes a vital connection to a personal past.” (

Watson 1996, pp. 298). The rise of autobiographical works on interracial kinship—from Barack Obama’s

Dreams from My Father (1995) and Bliss Broyard’s

One Drop (2007) to Lacey Schwartz’s

Little White Lie (2014), is firmly placed in this paradigm. Nonetheless, in my view, they represent a fourth phase in the history of genealogy wherein subjects now publicly trace kinship and ancestry across the color line. The ‘autobiographical pedigrees’ that I now identify in a set of children’s picture books might further constitute a fifth phase where genealogies are not only drawn across color lines, but also beyond the longstanding imperative of heterosexual-biological descent as the only basis for understanding the formation and continuity of familial ties. Interestingly, despite this radical revision, these objects come full circle in genealogy’s history by relying on the visual to construct and conserve family history.

4. The Cultural Work of Autobiographical Picture Books about Queer Family Formation

Since childhood is conventionally constructed as a phase of innocence, scholarship is often met with affective resistance when it calls attention to ideologies that shape the allegedly equally innocent literature designed for children (cf.

Sarland 1999, “The Impossibility of Innocence”). From my German perspective, this conflict has played out most visibly in a nationwide controversy in 2013 when black activism succeeded in prompting some publishers to replace racist terms in classic children’s literature such as Astrid Lindgren’s book series

Pippi Longstocking. A number of influential white journalists vehemently spoke out against these revisions as oppression and censorship by political correctness. In fact, they defended narratives as ideologically innocent in which, for instance, the protagonist Pippi celebrates how her white Swedish father set out to explore the South Pacific, became the ‘N*könig’ (‘King over N*word’)

2 on the island of ‘Takatukaland,’ and affirmed her place as the succeeding ruler over black people. Such widespread refusal to recognize the coloniality of a traditional canon of European children’s literature is nothing other than an attempt to uphold one’s own childhood as innocent in which one has unconsciously entered into a racist symbolic order of the world through children’s literature as a central form of everyday cultural instruction.

My local anecdote serves to illustrate how social forces and histories are negotiated in and around children’s literature, even when they may not be as straightforwardly problematic as in the example invoked above. My analyses seek to uncover these forces and histories with regard to race as well as sexuality. A mandate of putative innocence in children’s literature has been complicit in making queerness culturally illegitimate by rendering homosexuality invisible in story lines. The genre is often presumed to be free of a discourse about sexual orientation. However, as Tison Pugh demonstrates, “Children cannot retain their innocence of sexuality while learning about normative heterosexuality” (

Pugh 2011, p. 1). Writers and readers of children’s literature have long been involved in a learning and internalization process of heteronormativity, a dynamic of covert disciplining wherein a heterosexual family background and an implied heterosexual future of the protagonist as well as the child-reader is presented as the only viable imaginary (cf.

Pugh 2011, pp. 1–20).

The material I examine in this article participates in a broader intervention into anti-queerness in children’s literature. Perhaps the most prominent example is the gay-bunny-romance bestseller A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo (2018) that has emerged from the HBO show Last Week Tonight with John Oliver as a parodic stance against Vice-President Mike Pence’s heterosexist politics and his daughter’s picture book Marlon Bundo’s Day in the Life of the Vice President (2018). The texts to which I now turn have not risen to the same fame, but the cultural work they perform might be as audacious because their narrators try to resolve the tenacious, antithetical relation between homosexuality and family formation. In the following, I theorize these narratives as multilayered acts of queer empowerment that operate on autobiographical discourse and a familial reading practice.

The blurbs on the back cover of my three cases studies

Daddy, Papa and Me (2003),

My Two Uncles & Me (2016), as well as

Arwen and Her Daddies (2009) explicitly frame the books as autobiographical works by the adoptive parent-author. Yet, the books contain narratives that are presented in the adoptee child’s voice and act in similar ways as recent fictional, first-person children’s literature about queer-interracial families, such as Vanita Oelschlager’s

A Tale of Two Mommies (2011) or Carolyn Robertson’s

Two Dads (2014). Whether factual or fictional, the text functions as an intimate encounter through first-person narration as an established literary strategy for effectuating a reader’s identification with the narrating protagonist—in contrast to omniscient, impersonal storytelling about someone else. First-person narration sets up an aesthetics of intimacy and immediacy in which the narrator discloses their own story to an implied reader who witnesses events from their point of view. For this reason, children’s literature often employs autobiographical discourse as a technique to draw in the reader/listener. Affective involvement in the storyline can even be heightened through “active narration” (

Schwenke Wyile 1999, p. 198) by way of an explicit address to the reader. It is along these lines that the narrator-protagonist Arwen appears in a form of a frontal shot on the first page of her ‘own’ narrative and implicates the reader into a verbal-visual narrative of familial beginnings: “Hi, My Name is Arwen. […] Do you know How My Dads and I became a family?” Such illustrations work to emphasize the quality of a personal encounter. We are not literally seeing events through the protagonist’s eyes in correspondence with first-person narration. Instead, the onlooker assumes a visual third-person position from which we enter the scene and become spectators within diegetic world-making. See

Figure 1.

The narrative worlds these children’s books create pursue two forms literacy. On the one hand, these books become instruments in the attainment of linguistic proficiency through simple language and bold, large letters. On the other hand, children’s literature has always also been a tool of cultural and behavioral training. Yet, whereas most children’s books indirectly promote a heteronormative social order and its ‘reproduction,’ LGBT picture books provide children with the visual education to decode queerness in terms of familiality. These books may be primarily conceived to instill self-esteem in children of queer parents who thus find themselves reflected and legitimized as part of an extended concept of family. However, I would argue that the act of identification and validation becomes a practice of the entire family. Due to the limited reading skills of the main intended audience, these objects usually function in dynamics of reading along and being read to, thereby creating another level of intimacy and identification. Queer parents who read the story aloud in bodily proximity to the child also find themselves reflected and validated, especially because they understand it as an autobiographical representation of the author via the blurbs on the dust jacket—such blurbs, directed at potential adult buyers, are usually not vocalized when reading to children. My analysis now turns to those adult producers and consumers of queer children’s picture books. Since the autobiographical story is not the narration of an actual child, but that of an adult queer adoptive parent, I frame these narratives as ‘adoptee ventriloquism.’ This framing is based on the premise that children’s literature is primarily revelatory of adult investments in children and childhood and that these investments obliquely manifest themselves as “shadow texts,” in other words, as these narratives’ “unconscious” (

Nodelman 2008, p. 200). I zoom in on the “hidden adult” of these picture books and ask what cultural labor the ventriloquist’s puppet might be asked to perform (cf.

Nodelman 2008, p 206).

I think that that the child functions as a trope of innocence whose properties are sought to be conferred onto the entire family unit through verbal and visual narration. If multiracialism’s discursive emphasis on the mixed race(d) child has functioned to “retroactively” exonerate the straight couple for transgressing the taboo of interracial sex (

Sexton 2008, p. 38), the adopted child in this scenario may be redemptive with regard to a different taboo of corporal intimacies: Homosexuality. The trope of the child as an established symbol of futurity resurrects a presumed ‘culture of death’ and domesticates queerness, literally as well as figuratively, by endowing it with a desexualizing, valorizing, and recognizable sign of family life. This public recognition as family indirectly comes at the expense of previous politics of queer kinship. Kath Weston’s study

Families We Choose demonstrates how diverse queer relationships between adults in the 1980’s were claimed as family in an effort to transform the state’s policies of kinship regulations with the goal of extending rights and resources such as shared health insurance beyond the heterosexually married household. For a range of queer studies critics, the eventual abandonment of families of friends in favor of an activist focus on marriage and adoption represents a collective turn toward ‘homonormativity.’ From this angle, integration into the state institution of family is understood as assimilationist complicity with a heteronormative regime that continues to pathologize those queers who do not commit to an ideology of privatized, child-centered family. Yet, adoption cannot exclusively be understood as relenting to respectability politics because intrinsic aspirations of queer subjects and those of families of friends do not necessarily exclude the wish of raising children. Moreover, striving for marriage and adoption can be read as the attempt to compensate for bonds of kinship that have been severed by the deaths of the 1980’s AIDS epidemic (cf.

Butler 2002, p. 25–26), by the rejection of one’s own birth family, or by various political frictions that have obstructed quests for “the holy grail” of unified queer community (

Weston 1991, p. 206).

Along with previous politics and histories of queer kinship, autobiographical picture books for LGBT families usually overwrite the relevance of race. This equally applies to the majority of life writing about queer adoption—from memoirs and auto-documentaries to blogs—that conspicuously often feature interracial constellations, but are dominantly silent about race and racism or even explicitly downplay its significance. In part, I understand the reluctance to address race as a subconscious maneuver to repress the preconditions of interracial adoption. White couples are often matched with non-white adoptees because racial profiling in the state’s practices of penalization and incarceration particularly undercuts the custody rights of parents of color and especially those of African Americans, which ultimately leads to a disproportionate number of black children in the adoption system (cf.

Briggs 2012). Yet, as David Eng shows in

The Feeling of Kinship, queer empowerment at the turn of the twenty-first century is often shaped by “the active management, repression, and subsuming of race” (

Eng 2010, p. 17) because it prioritizes queerness as a putatively single-issue matter. In this vein, autobiographical narratives about gay and lesbian adoption are often put forward as part of LGBT activism and as a celebration of its progress. But they rarely acknowledge the racial dimension of what at first glance might appear as an innocent milestone of queer civil rights success. A very particular form of displacing race in claims to queer kinship recognition manifests itself in the series of self-published autobiographical picture books that are the focus of this article. Whereas same-sex constellations are explicitly addressed through narration and the peritextual apparatus, race becomes a hypervisible but muted part of images that accompany the text.

In what follows, I elucidate the theses outlined above with three picture books that each stand in for a specific type of queer family formation across the color line. The ‘autobiographical pedigree’ of Andrew R. Alrich,

Daddy, Pappa, and Me: How My Family Came to Be, delineates a family history that originates in state-recognized adoption. Jeff Rivera’s

My Two Uncles & Me (

Rivera 2013) documents the development of queer interracial kinship as the extension of a heterosexual family unit and thus sheds light on a form of adoption that is not formalized or recognized by the state and which usually goes unaddressed in discussions and research on gay family caregiving. Finally, Jarko De Witte van Leeuwen’s

Arwen and Her Daddies (

De Witte van Leeuwen 2009) drafts genealogies of queer interracial adoption in Europe that are intimately interwoven with the US context.

5. Daddy, Pappa, and Me: How My Family Came to Be

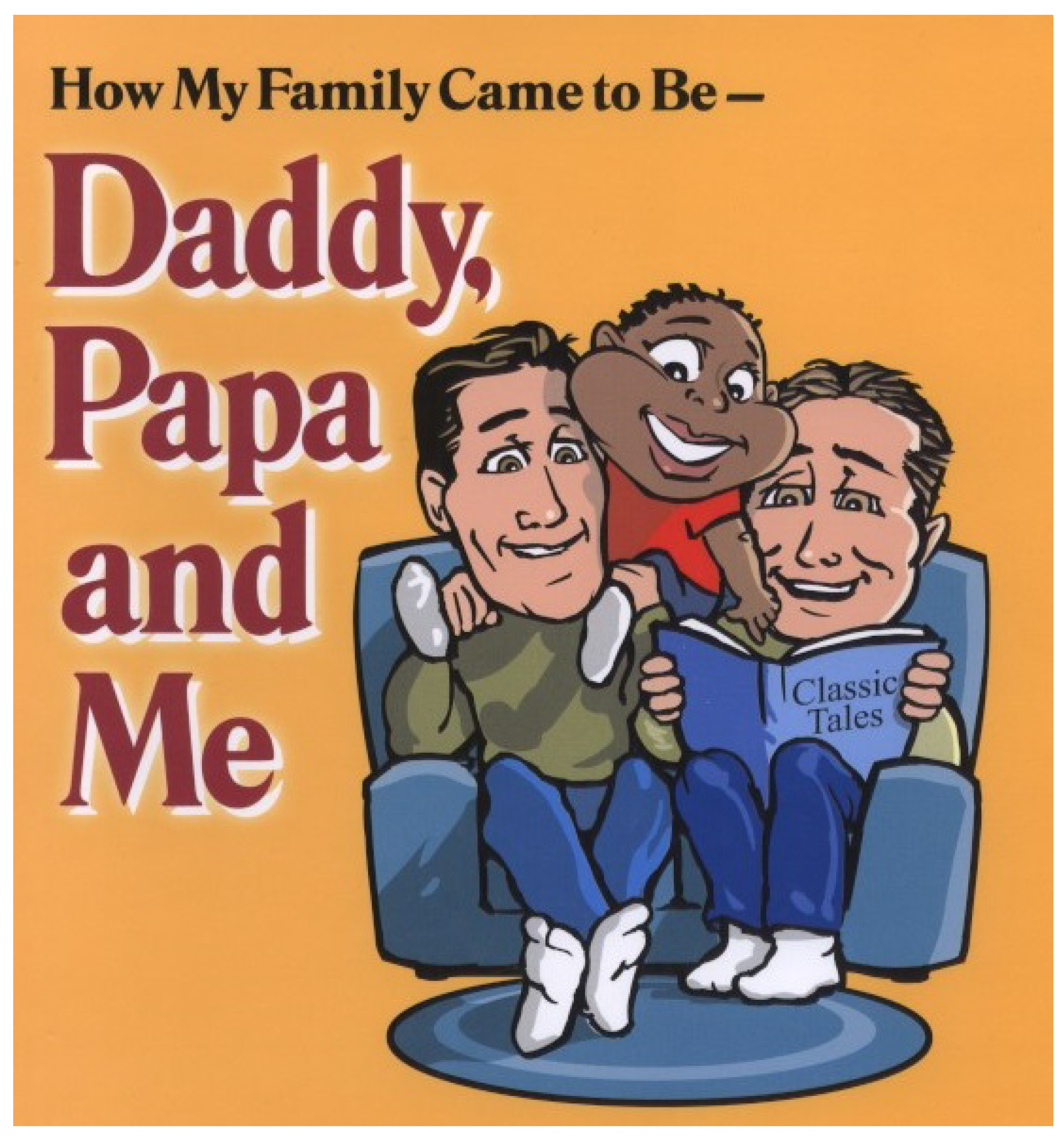

The title of Aldrich’s self-published read-along book announces a story that brings queerness into a familial frame of reference as well as into one of genealogy, i.e., a narrative of family formation:

Daddy, Papa and Me: How My Family Came to Be (

Aldrich and Motz 2003). However, queer genealogies are not drawn as bloodlines to construct familial origins and continuity as the conventional practice would have it. ‘Autobiographical pedigrees’ like this one pursue multiple, alternative strategies to convey a coherence of familiality. In this case, mediating gay family history already begins on the cover where image and title demand the recognition of a queer plural of fatherhood: “Daddy, Papa, and Me.” Rendering queer interracial familiality intelligible and coherent is implicitly reinforced by framing this kinship claim within the acoustic unity of an end-rhyme “How My Family Came to

Be/Daddy, Papa, and

Me.” At first, this aspect might sound irrelevant. But these objects are generically embedded in practices of reading out aloud to children, where recurrent rhyming works as a mnemonic strategy of narrative and ideological retention. Aldrich’s book thus adopts a catchy mode of normalizing queer family through the de-stigmatizing innocence of a child’s rhyming voice. See

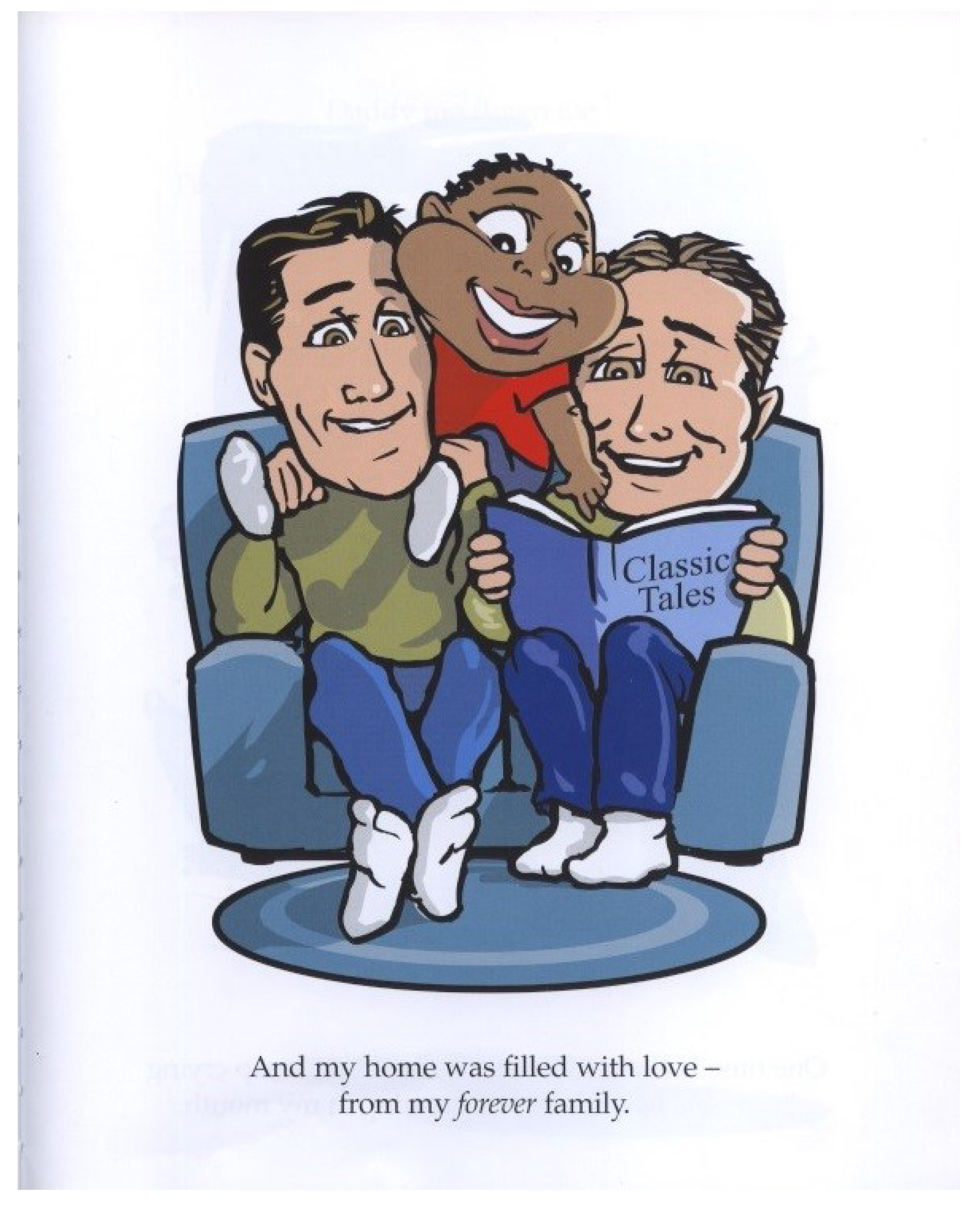

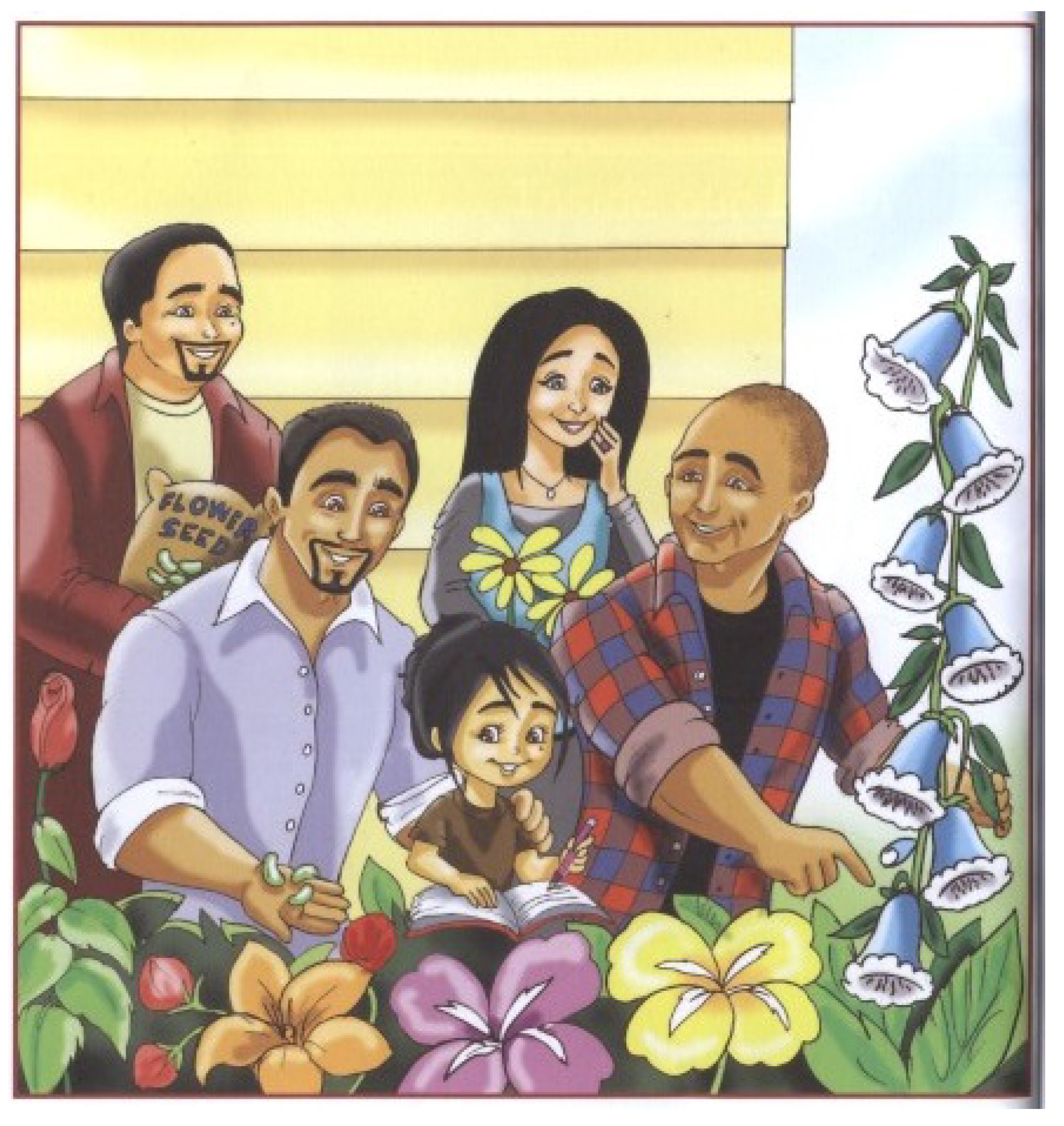

Figure 2.

Another way in which the cover indirectly sets up a framework of familial recognizability for this modern constellation begins by encoding the story as merely a novel variant of an old story of mutual love between parents and children. This group of individuals may not be endowed with the familial norm of physical resemblance or the symbolic capital of heterosexuality, but they cohere as a unit through affectionate proximity that is amplified through similar clothing. The fathers wear identical apparel that partially matches the child’s appearance through a blue coloring that not only frames the entire group but also the domestic background of couch and carpet. In fact, blue coloring pervades the entire verbal-visual narrative as a leitmotif to produce an abstract, visual continuity, and coherence that resembles the function of ancestral lines of a genealogical chart. Moreover, the family members are united by an act of reading as their gaze is collectively directed at the book

Classic Tales. The attempt to legitimize new family formations by promoting them in relation to old cultural templates is a popular strategy in multiracialism. Most prominently, racial mixing across the color line has been sought to be valorized by declaring it as nothing other than the fulfillment of the centuries-old foundational myth of America as a melting pot. A similar dynamic can be observed in other self-representations of queer interracial families that have come forward over the last two decades. In the autobiographical documentary

Off and Running (

Opper and Klein-Cloud 2010), for instance, a white, Jewish, lesbian-headed, multiracial household is supposed to be normalized as simply another

American Coming of Age in the subtitle. In a similar way, the subtitle of the filmic anthology

Daddy & Papa implicitly seeks cultural authorization by the following rhetorical question that challenges the notion of queer adoption as something radically new:

What if your most controversial act turned out to be the most traditional thing in the world?Yet, all of these works set out to affirm definitions of family that deviate from ‘classical tales’ of family, so to speak. In the opening flap text of Aldrich’s cover we are informed that “[t]he story grew out of the author’s need to explain to his son how their family came to be and what ‘family’ means. […] the book shows how his family was created and that families are made up of people who love each other.” Within this autobiographical framing of the text, Aldrich dedicates the book to his son “Nehemiah, and other kids lucky enough to have both a Daddy and a Papa.” He thus articulates a kinship claim that implicitly revokes a hegemonic definition of family in favor of reciprocal affection as a foundational and shared substance instead of blood. The narrative of Nehemiah’s queer genealogies further becomes envisioned as a tool of empowerment and intervention for an imagined community of LGBT families. Aldrich’s dedication and aspiration additionally dovetails with testimonial endorsements on the back cover, where, for instance, the prominent gay activist Dan Savage envisions: “this is a book that will make a difference in the lives of children adopted by gay couples.” Ultimately, this book inscribes Aldrich’s own political genealogies when putting forward the text as a commitment “to advocating for families with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender members.”

In the narrative itself, Aldrich speaks through a young black protagonist—presumably Nehemiah—who begins to retrospectively tell an origin story about gay interracial familiality: “The day I was born was a

happy day” (emphasis original, See

Figure 3). Having started on a positive and empowering note, the narrator tells the reader on the following page about the history behind his adoption by explaining: “My birth mom was too sick to take care of children, but Daddy and Papa wanted a baby

just like me!” (emphasis original). This narrative explains a transition from birth family to adoptive family as a valorizing inversion, in which the child that had been given up for adoption re-emerges as a ‘planned child,’ with an emphasis of italics and an exclamation mark. I understand this emphasis to contain a muted racial dimension of empowerment for the adoptee. Whereas other white couples involuntarily found interracial families out of structural reasons, this couple appears to actively seek to form a family across the color line in a culture that favors white over black infants.

In line with this discourse of devotion, the picture book reveals the labor that goes into rendering queerness into a normatively viable kinship model. At first, the two men seem to become legal guardians through “

lots and lots of paperwork” (emphasis original). More importantly, they become culturally legitimate through a process of domestication and de-sexualization. A series of verbal and visual sequences demonstrates their exhausting efforts of caregiving within a nuclear, middle-class household, but never shows them exchanging physical affections with each other. I do not necessarily point this out as a critique of Aldrich but rather in order to identify the stakes of queer family validation in the public sphere, where particularly gay men have to perform as über-fathers to be recognized as acceptable parents to a heteronormative “familial gaze” (

Hirsch 1999) that has been instructed to associate homosexuality with hypersexuality and a threat of pedophilia. The vectors of this hegemonic gaze became very clear to me when I first presented this material to an academic audience. After my talk at an American Studies conference, one professor approached me to bewilderedly point out: “Of course one cannot show two men share a kiss in the proximity of a child. Everybody would be anxious about what they might do to that child.”

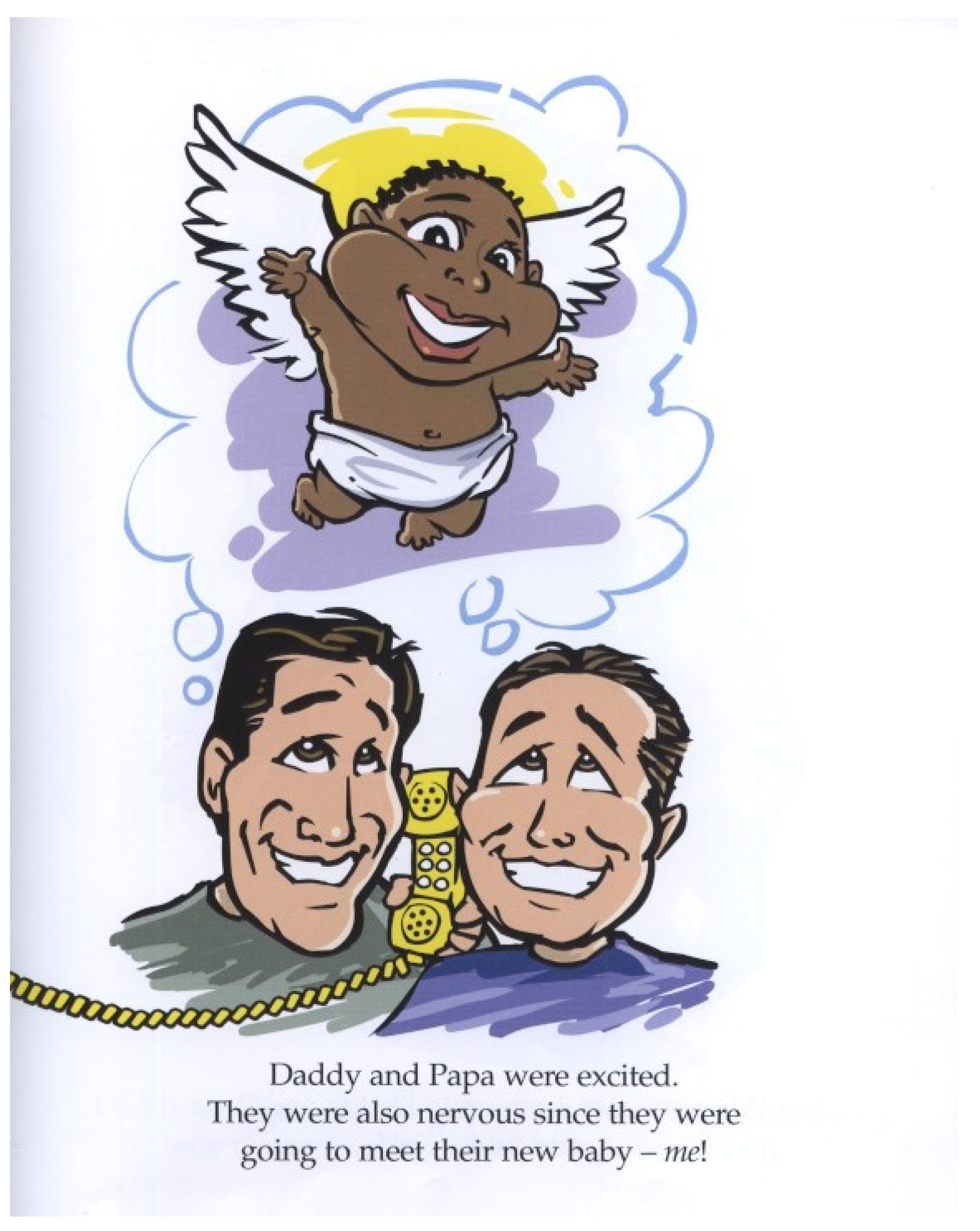

A discourse of innocence also materializes in the peculiar way this ‘autobiographical pedigree’ constructs the foundational moment in the making of queer interracial genealogies by anticipating the moment of adoption as an angelic arrival See

Figure 4. Even as a humorous gesture, I find this image striking because it implies a form of immaculate conception for this queer interracial family. However, the black child of white adoptive parents usually does not come out of the blue but is often placed there by the combined conditions of a racialized punishment system and white, middle-class couples who actively search for children. The family memoir neutralizes the former dynamic through a display of colorblind love and inverts the latter by turning the actual agents into passively (a)waiting figures while the action seemingly unfolds from an infant child that descends from the sky and then runs toward his designated parents. He embodies the trope of the child as a savior figure by which queerness is redeemed from cultural stigma and converted into nuclear family. A ‘culture of death’ comes alive. In a following repetition of the cover image, the act of adoption is enshrined as founding a “forever family,” which is a term that pervades the parental memoirs by queer men. It bespeaks a desire for familial continuity that has often been disrupted through anti-queer rejection by their own birth families and the fragmentation of queer families of friends through the deaths of AIDS. Queerness here affirms familial bonds as a nuclear, child-centered formation that is demanded to be recognized as a “classic” family, or as the final sentence of the book puts it, “just like other families.”

This claim of recognition is interestingly framed through two meta-textual forms of mise en abyme. Opening Aldrich’s read-along book, we encounter an autobiographical reflection of kinship that is designed for a familial practice of reading and identification. Its central image features parents reading out aloud to their son who points at the book in which he might see himself reflected, just like the child to which

Daddy, Pappa, and Me is supposed to be read to as a main target audience See

Figure 5. If this narrative of family formation began with an image of the narrator-protagonist alone, he re-appears at the end by looking back at a reflection of his family in a framed picture as a metaphor for the retrospective narrative family portrait he has now completed. See

Figure 6.

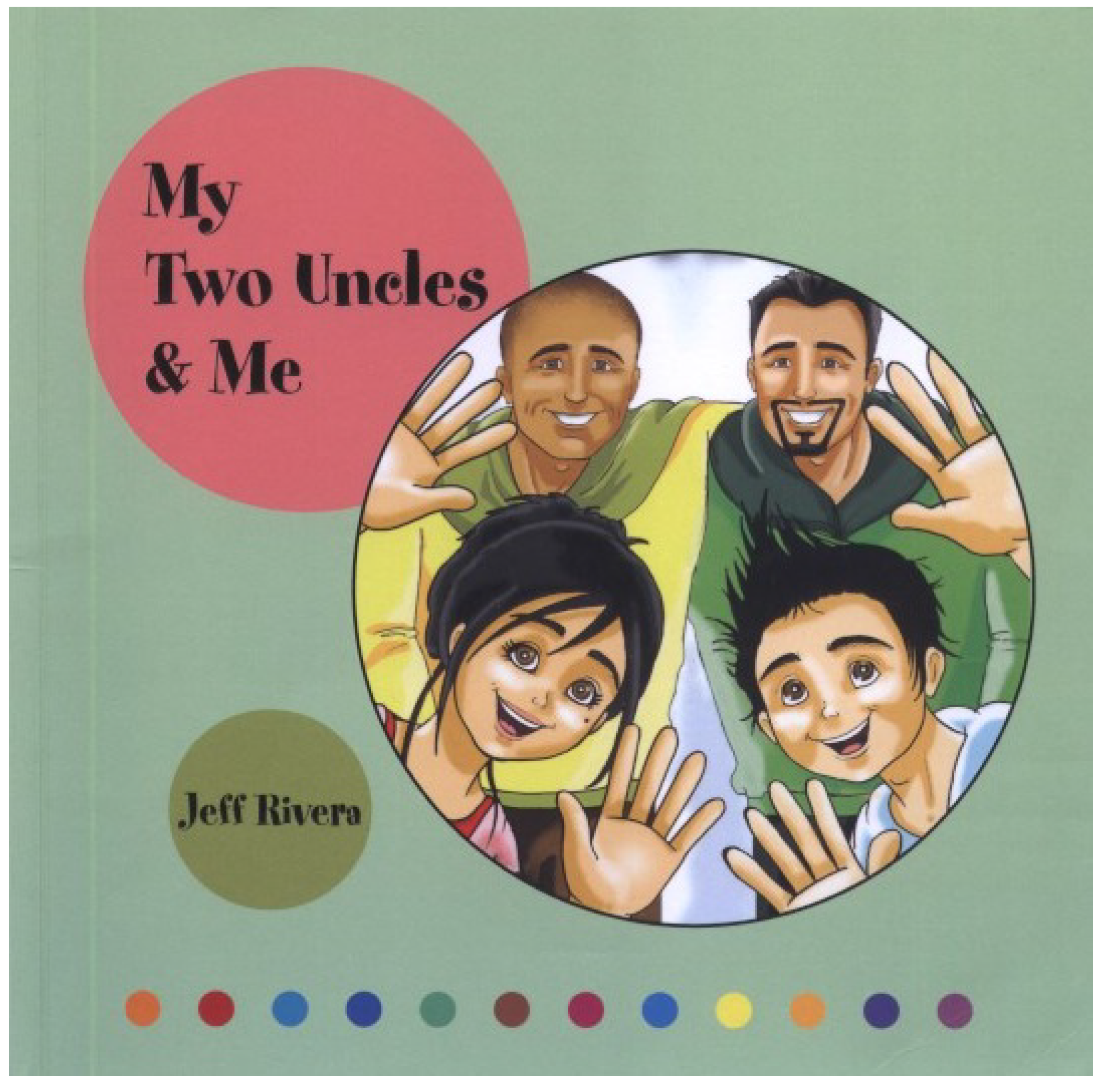

6. My Two Uncles & Me

In a context of informal adoption, artist and activist Jeff Rivera has self-published a book that brings into focus what critic Nyong’o would understand as queer family members “who dot the perimeter of” multiracialism’s “promised land of heterosexual nucleation” (

Nyong’o 2009, p. 176). The cover visually frames

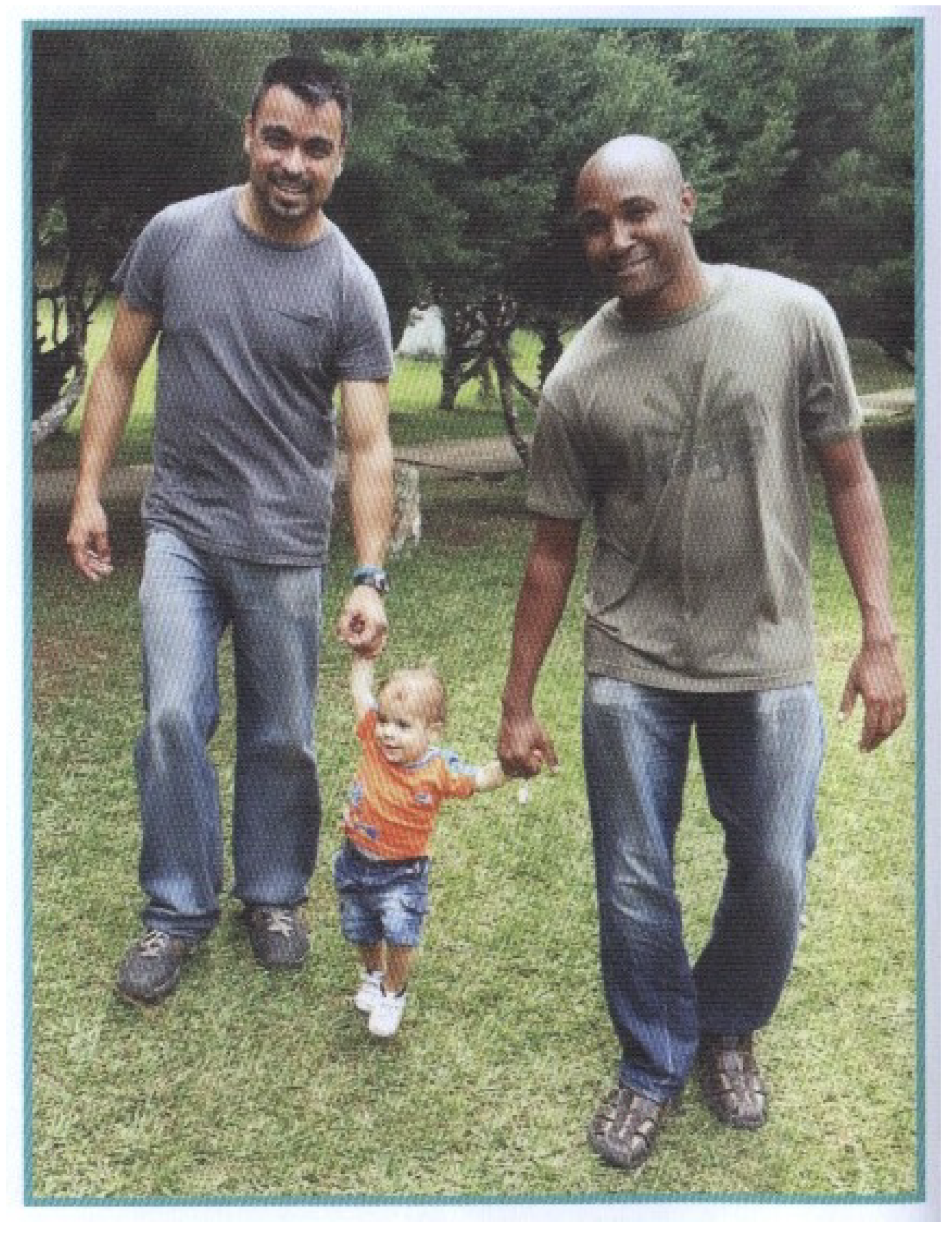

My Two Uncles & Me in the logic of an intimate encounter between the protagonists and an implied viewer who is afforded a personal glimpse into queer family life by way of the aesthetics of a sort of peephole through which this constellation greets us and awaits to be seen and recognized by a familial gaze. See

Figure 7. As one opens the book and enters into this family portrait, the text itself works as a ‘selfie’ by and about the alternating narrators of niece and nephew. They seem to provide verbal and visual snapshots of a family life that extends from nuclear heterosexuality to queer uncles as central caregivers. But after the main narrative is completed, the ventriloquist appears at the end of the book in a picture that functions as a form of documentary truth claim to the illustrated story. See

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. His voice manifests in blurbs on the back and front cover flaps to put forward the book as LGBT activism as well as in dedication to the “Delgado-Castro Family who have accepted us into the family exactly how we are with open arms.”

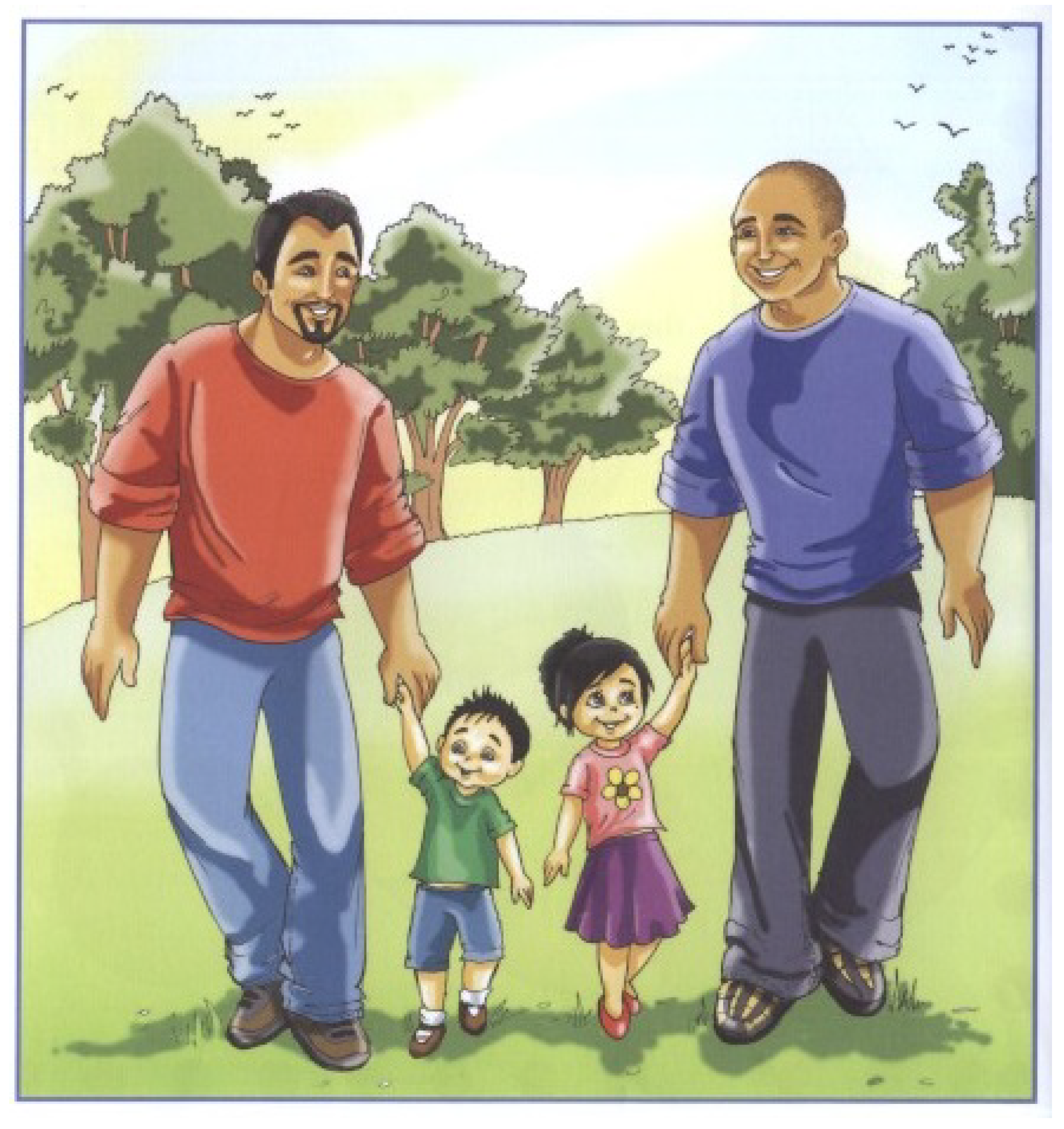

This genealogy does not unfold in a linear mode as Aldrich’s family memoir. Instead, this read-along bedtime story uses first-person nursery rhymes that produce familial affection and affiliation through a multilayered paradigm of repetition. As the opening lines attest: “My two uncles they take me out to play/they take me out to have some fun every single day” (emphasis mine). Through simple present as the tense for habitual and recurring events in tandem with the harmonizing iteration of rhyming couplets, the text affirms queer interracial kinship through routine. It is a display of domestic routine framed by acoustic routine for the sake of queer family to eventually become cultural routine. This paradigm of routine possibly extends into reading practices, wherein children tend to demand particular narratives to be read out aloud, time and again, as familiar and familial stories that lull them to sleep.

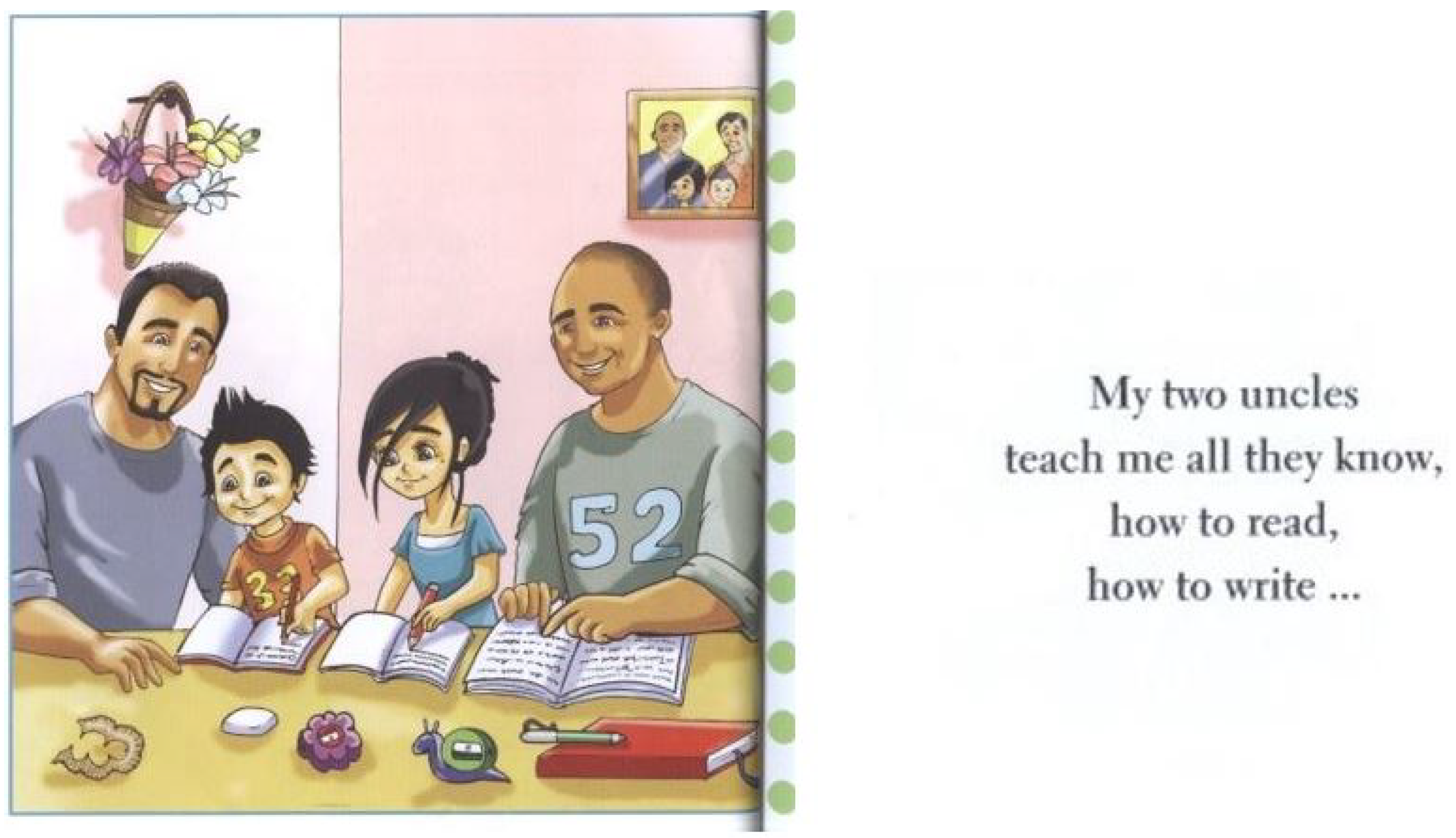

Rivera’s bedtime story showcases a queer interracial couple as exceptional caregivers who are not distinguished in terms of biological and non-biological kin. They are simply “My Two Uncles.” These uncles complement the nuclear family in terms of child-centered affection as well as through assistance in a variety of activities and household chores, from washing clothes to baking. The representation of their help with the protagonists’ homework stands out because it embodies another instance of repetition, a visual one. Behind the two uncles and the children, we can see the reflection of light on a framed picture that shows the same four in a mirror-inverted arrangement. In other words, in this mise en abyme, we see a literal reflection on the figurative reflection of a queer family in a children’s book that is produced so that other LGBT families can see themselves reflected in children’s literature and in US culture at large. See

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

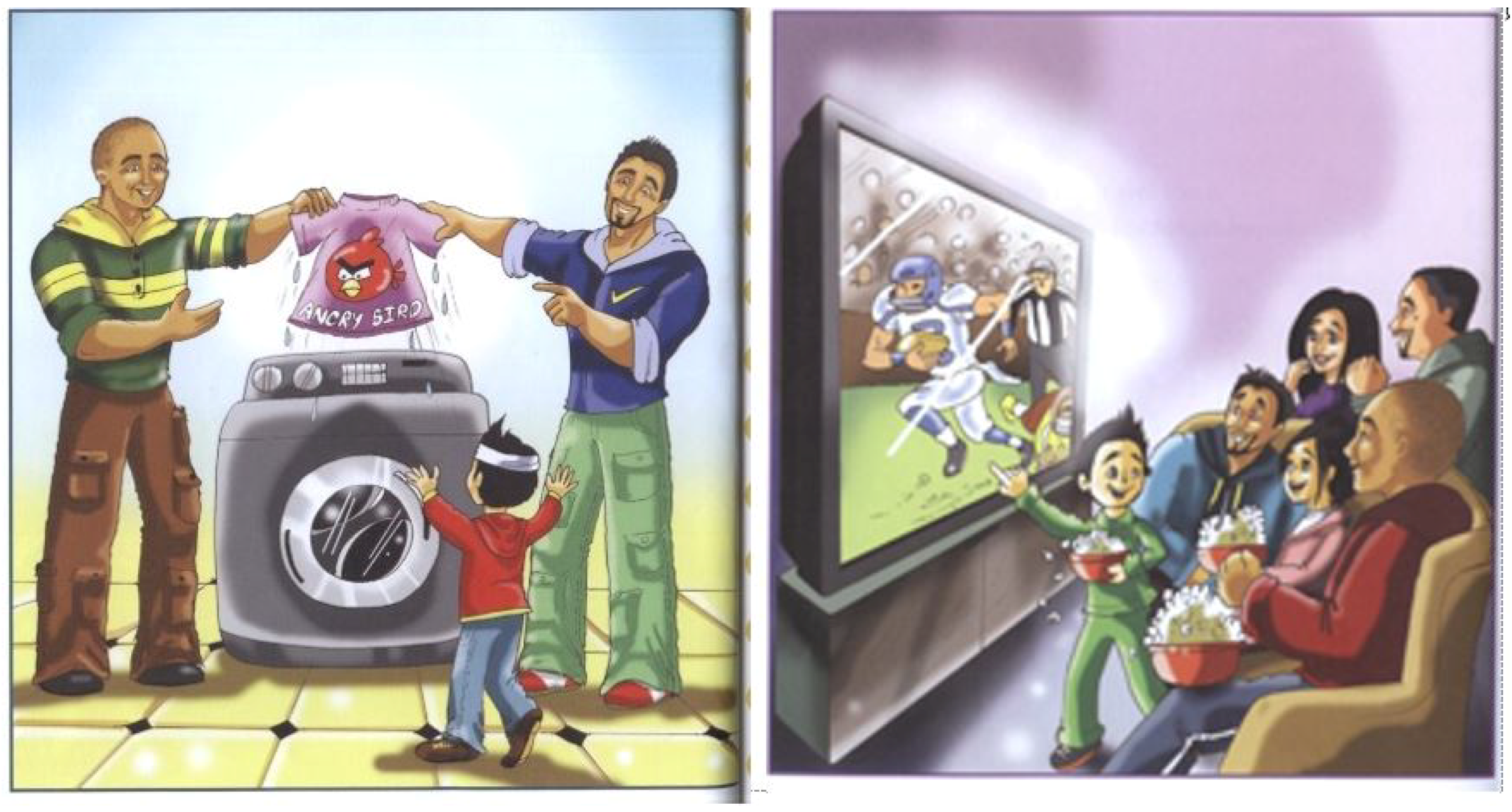

Along the trajectory of empowerment rhymes and images, the routine in

My Two Uncles & Me also works to validate this family by trying to neutralize stigma around gay sexuality. Among the various activities, a particular emphasis is placed on football through repetitive verbal and visual references: “My two uncles love their football games.” With football as a fundamentally masculine-coded sport, this has the implicit effect of countering a devaluing discourse of gay effeminacy and is underlain with an almost hypermasculine depiction of the uncles’ body language. In unspoken ways, the couple is further legitimized by inverting stereotypes about threatening gay hypersexuality. They are desexualized not only by their exclusive characterization as caregivers in the act of narration, but also by way of illustrations that insist on a conspicuously consistent physical distance between them. Either divided by an extra amount of space or separated through the insertion of the protagonists between the two, bodily proximity is even attenuated in the very few instances in which they are standing right next to each other. After a final “good night”, the narrator’s voice has faded out and the final page ends without text but with an image of the children asleep and surrounded by their family. Whereas the heterosexual parents hold each other in an intimate, caressing embrace, the queer uncles appear in an awkward pose. Their representation appears to mirror the parents’ embrace, but the depiction avoids hip contact with the result of a body language that bears a telling resemblance to the masculine football cheering from an earlier segment of the book. See

Figure 12.

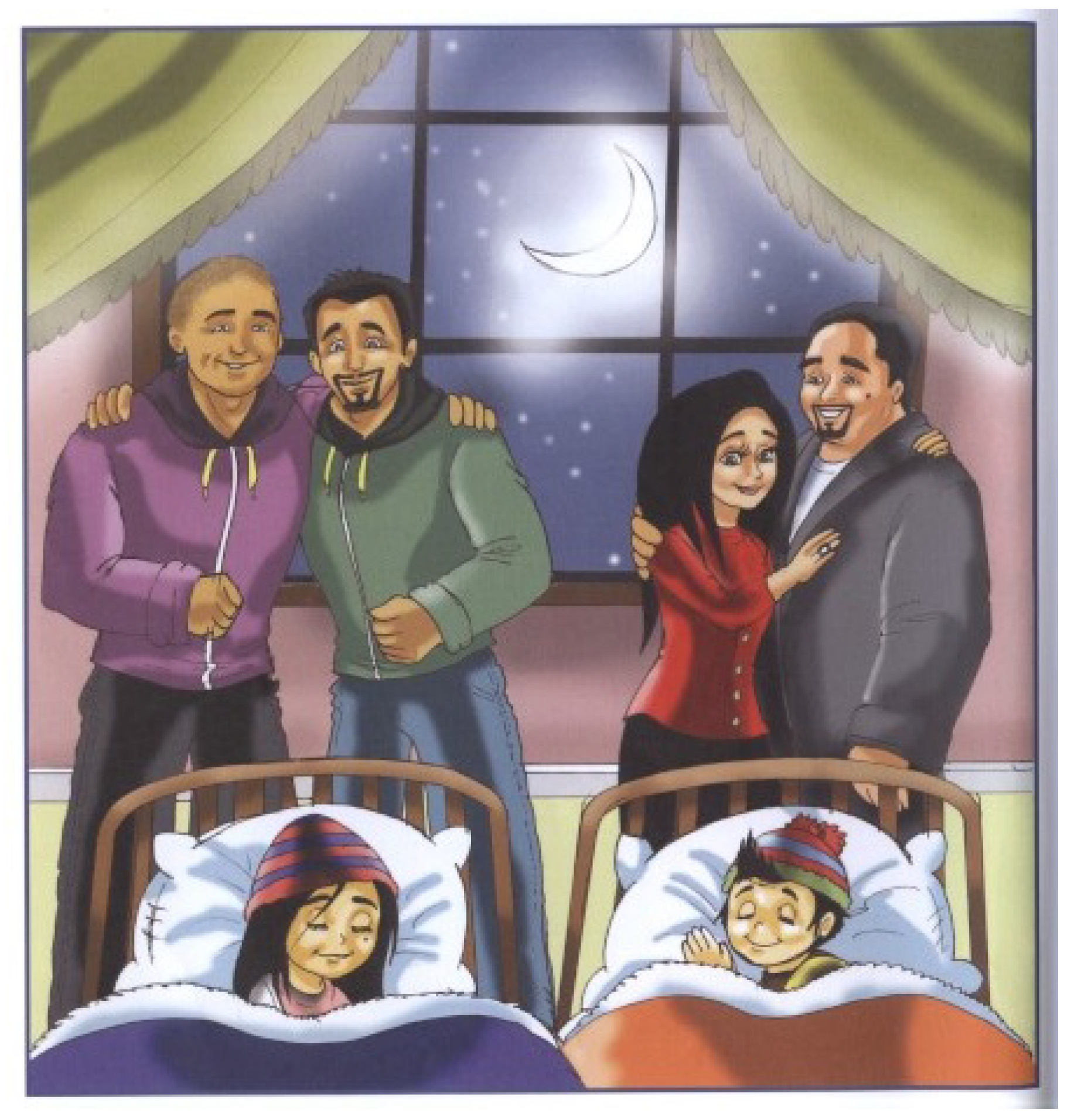

While the final image of sleep would usually be understood as the focal point of a children’s bedtime story, another image and narrative passage constitute the figurative center of

My Two Uncles & Me. Half-way through the nursery rhyme emerges a symbolic inscription of queer involvement in the management of nuclear, heterosexual family. See

Figure 13. The uncles are shown to seemingly advance the protagonist’s knowledge about the school subject of biology and plant ‘seeds’ into the garden, which come from a ‘bag’ held by the father: “My two uncles teach me all they

know/how to read, how to write/about how my flowers

grow/My two uncles help me with my

test/day and night we study so I can be the

best.” Amid a superabundance of life and reproduction via the signifiers of seeds, flowers, and children, an alleged ‘culture of death’ comes alive. Queerness is evacuated from an antithetical relation to family and converted into a surplus value for the individualist success of offspring: “day and night, we study, so I can be the best.” Again, queerness must perform exceptionally to be granted with the recognition of familial normalcy. These uncles may teach their niece and nephew how to read and write, but the more significant legacy or ‘seeds’ they pass on is the cultural literacy to recognize and claim queerness in terms of family. It is an instruction of the familial gaze that is transmitted via the medium of the read-along book in a routine of bedtime stories for reading, listening, and viewing consumers. The bonds of kinship between Rivera, his partner, niece, nephew, and biological parents may not be recognized by the state as one family unit, but the picture book itself stands in as a formalizing founding document.

7. Aarwen and Her Daddies

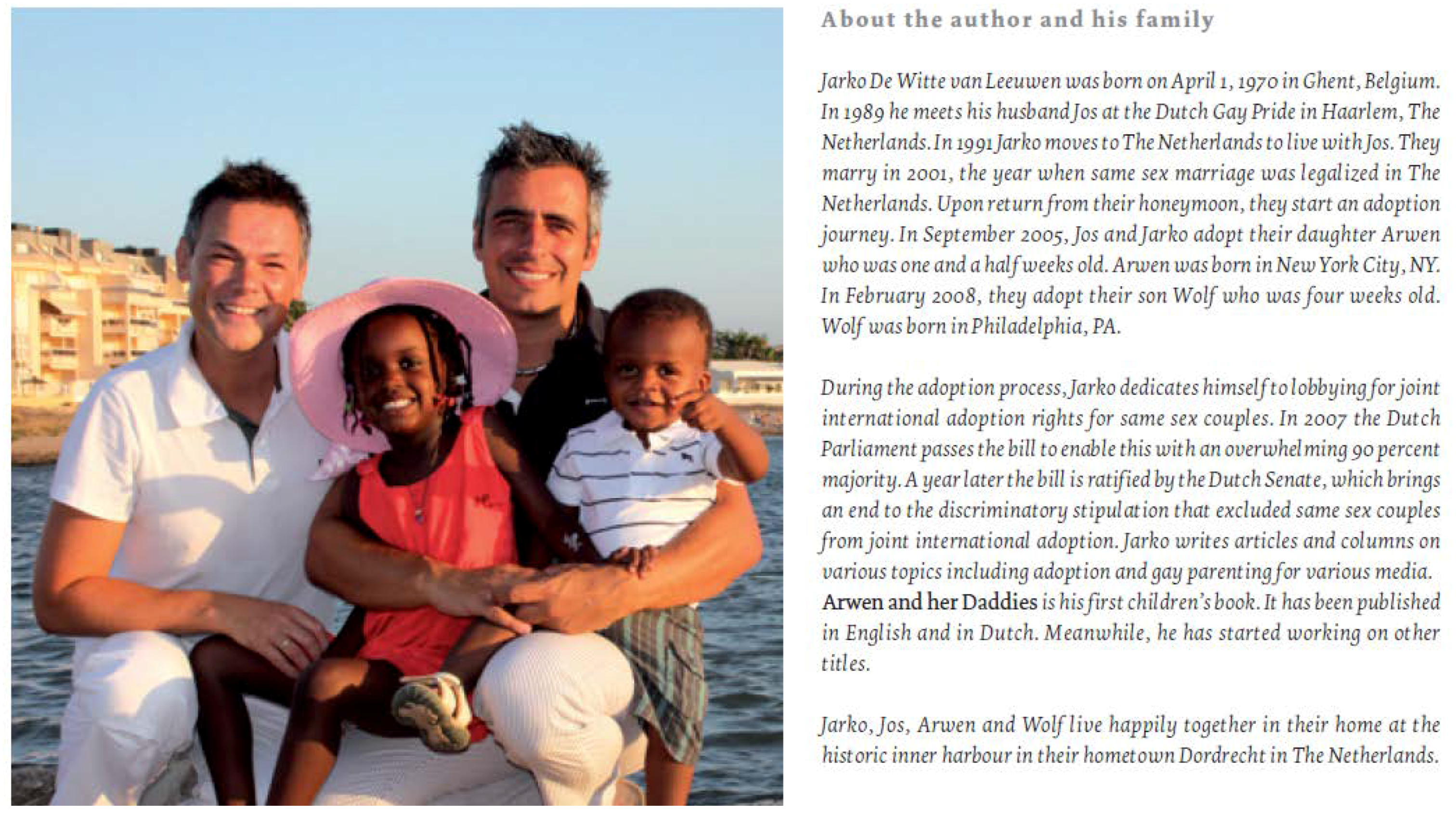

Jarko de Witte van Leeuwen’s self-published, Dutch

Arwen & Her Daddies (Arwen en haar papa’s [2009]) reveals the transatlantic dimensions of queer interracial genealogies, where African American children are also adopted by white queer couples in Europe. Racial difference, however, is only indirectly addressed in the ventriloquist’s praise of a “diverse society” and by way of illustrations. On the back cover, De Witte van Leeuwen announces the book as an autobiographical narrative of family formation and as an individual as well as collective empowerment tool against the heteronormativity of mainstream children’s literature:

Our daughter Arwen is very fond of books and having stories read to her. In all children’s books that we have read to her, sooner or later a mommy, or a mommy and a daddy, make their appearance. I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to be able to read a story to Arwen that features two daddies.’ So I started a search only to find very few children’s books featuring two daddies. Initially I had made this book just for Arwen … a single copy for our little girl to explain to her in an age appropriate manner—and when the time is appropriate for her

how we became a family. However, other families I spoke with were also interested in having a book about same sex parents and encouraged me to publish for other families to read. They too wanted a book for their children to learn about the

wonderfully diverse society that we live in. In addition, my hope is to have the book further communicate to children that it is perfectly okay to be who you are. For these reasons, I decided to publish Arwen and her Daddies for a broader audience. I wish you and your kids a lot of fun reading this book! (emphasis mine). See

Figure 14.

De Witte van Leeuwen dedicates the graphic memoir to his daughter Arwen who is morphed into the protagonist and narrator. She opens the narrative by inviting the reader into the story of her family’s origins with the following words: “Do you know how I and my Dads became a family?” The trope of the child-narrator along with colorful illustrations and photographs that display familial affection provides a powerful resource for the cultivation of self-esteem in black adoptees and their queer parents. Implicitly, the picture book furthermore negotiates transnational connections of racism and heterosexism. This particular ‘autobiographical pedigree’ not only arises from a context where a disproportionate number of black children are forced into the US adoption circuit through the state’s racial profiling of black parents. Further, because prospective white American parents often avoid the adoption of African American children—who make up a substantial percentage in the system—they are increasingly adopted by white queer couples from European countries, particularly the Netherlands and Germany (cf.

Brown 2013). Yet, queers from these nations do not necessarily turn to American agencies out of post-racial awareness, but due to structural reasons. Until recently, laws in most European countries either officially or unofficially denied or limited adoption rights to LGBT couples while policies against gay adoption remain intact in the majority of countries across the globe.

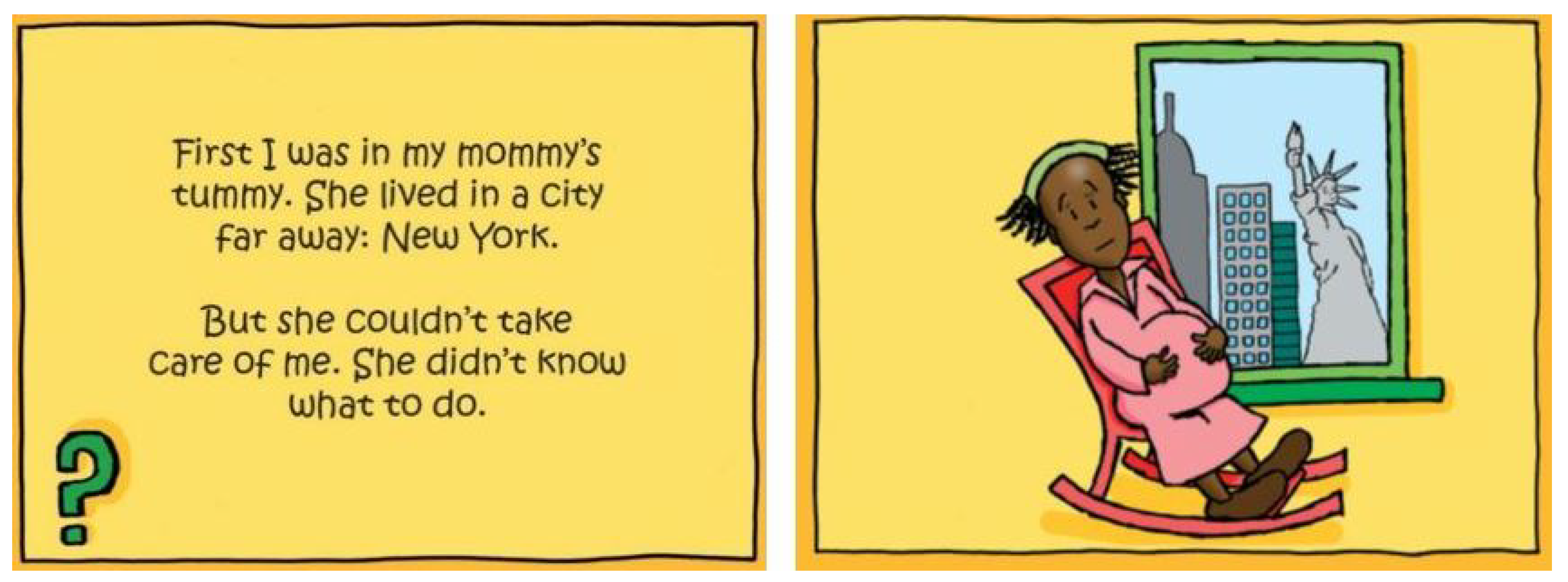

In the picture book, Arwen’s biological mother may appear in parallel diagonality to the statue of liberty (See

Figure 15 and

Figure 16) but is subsumed “in the wake of slavery” (

Sharpe 2016, p. 8), wherein the state undercuts black parental rights, commodifies black children, and circulates them across the Atlantic. Research on this phenomenon is sparse. Not only since it represents a relatively new kinship practice, but also because scholarship on LGBT kinship, here, often neglects racial aspects in their analyses. Thus, I turn to

Arwen and Her Daddies as sociological informants in my budding research project on queer transatlantic adoption.

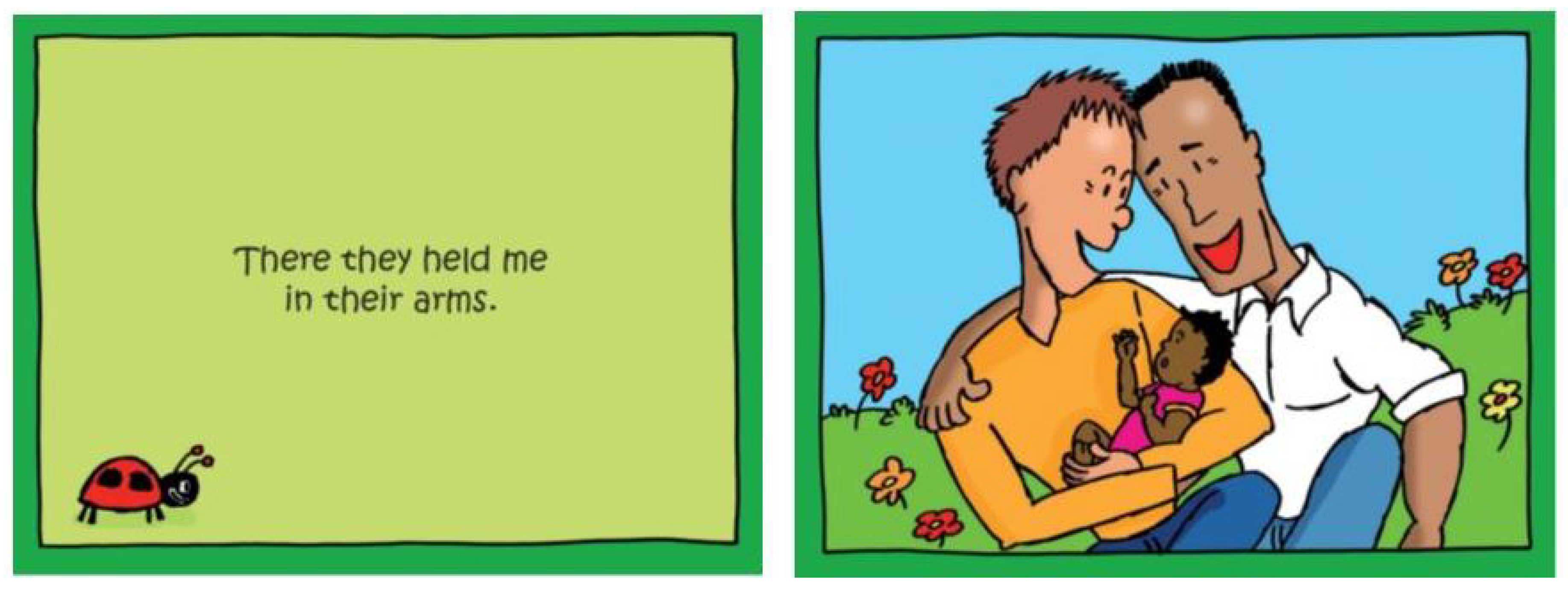

Like Nehemiah in Aldrich’s book, Arwen drafts two foundational moments in her queer genealogies. The first lies in the precarious situation of a black mother who is unable to take care of her child. De Witte van Leeuwen ventriloquizes and explains the process of adoption for other children in the voice of a fellow adoptee: “First I was in my mommy’s tummy, She lived in a city far away: New York. But she couldn’t take care of me. […] she went to people who could help her. These people work at an adoption agency.” A second foundational moment in her family history overwrites the former in terms of significance and relocates familial beginnings from “tummy” into De Witte van Leeuwen’s “arms.” Geographic distances and racial differences between Arwen and her designated parents are bridged by textually and visually foregrounding this moment in terms of effort, affection, and care. Amid the symbolism of flowers, another queer couple affirms itself as family life to the implied viewer’s gaze and emphasizes nuclear-domestic commitment to ensure their recognition as a viable family constellation: “A real family,” “Right from the start my daddies took good care of me. They bathed me, and they fed me my bottle. Then we flew home together.” I would argue that distances and differences in the making of this family are also sought to be painted over through a conspicuous coloring of the parents, where Jarko’s partner appears with a skin complexion near that of Arwen’s. From the angle of a symptomatic reading, this mode of representation seems to echo familial norms of physical resemblance. In convergence with reciprocal affection, the skin colors of these family members are radically approximated to underline the semantics of unity and continuity, “a real family.”

My point is neither to criticize gay desires for familial recognition nor to dismiss picture books such as

Arwen & Her Daddies. These primers are carrying out important interventions that enable children like Arwen and fathers like De Witte van Leeuwen to see themselves reflected in an everyday act of reading to and with one another. More than that, potentially, such books might also find their way onto the bookshelves of children with heterosexual parents to widen the focus of an established, narrow familial gaze. My analytical effort is directed at revealing adult desires that animate these books and to ask about their implications. Arwen has been given the help of a primer for an instruction in reading, writing, and cultural orientation, but what about her fathers? They might need didactic tools, too, an instruction in “racial literacy” (

Twine 2010, p. 89) that enables them to recognize the relevance of race within and beyond the family, inside and outside Europe, the insight that the activist achievement of LGBT adoption can become complicit with anti-black structures which allow them create a family across the color line and the Atlantic Ocean. White queer adoptive parents need to acquire a ‘racial literacy’ in countries like Germany where colorblindness is anchored as an allegedly anti-racist policy by the state, where the census and other state instruments refuse to account for the category and ramifications of race and racism.

8. Conclusions: Coming Out as Family

There can be something queer about genealogy. Queer in an archaic sense of the word because genealogy’s conventional designs rely on heterosexual procreation as a putatively neutral framework to determine what and who family is. In this article, I have shown that there can also be something queer about genealogies in a contemporary sense of the word by turning to ‘autobiographical pedigrees’ that are not structured around biologism as the guiding principle of family formation. Picture books such as Daddy, Papa, and Me, My Two Uncles & Me, or Aarwen and her Daddies are simultaneously intervening into the arenas of genealogy, multiracialism, as well as children’s literature and create a platform on which queer interracial constellations can ‘come out as family.’

This coming out actually begins with the conditions of publication. While memoirs about heterosexual-interracial family histories have become an unabated bestseller phenomenon since the 1990’s, the majority of autobiographical works about queer interracial adoption, including picture books, have been self-published. A number of them can only be found beyond mainstream channels of literature distribution. ‘Coming out as family,’ thus extends to an act of self-publication. It claims queer visibility in cultural moment that revolves around heterosexual family across the color line as the post-racial promise of a reproductive melting pot. The metaphor of the closet can be very useful in reviewing the cultural work of autobiographical narratives about queer interracial adoption because of the ambivalent forces of revelation and concealment, resistance, and assimilation that constitute public recognition of queer identities. Such self-representations may allow nuclear constellations to come forward as family, but they implicitly leave behind previous, broader politics of queer kinship and often end up in a “racial closet” (

Somerville 2010) whose doors block the view onto the frequently oppressive preconditions of adoption across the color line and sometimes even the Atlantic. Coming out is often propagated as an uplifting, linear action of empowerment, progress, and maturation. But that script obscures the circular temporality in which queer subjects have to come out, again and again, in various situations of their lives without ever reaching a point of arrival. The producers and target consumers of queer family picture books are equally under social pressure to render their attachments visible, intelligible, and legitimate as a family in public as part of an everyday routine. Perhaps the origin stories of gay family picture books can be best understood as an attempt to enshrine familial outness in a permanent form.

Some scholars might argue that there is nothing queer about the genealogies which are drawn across the pages of these children’s picture books or the pages of this article. That can be the case when queer is not used as a synonym for homosexuality, but in the sense of politics that radically resist heteronormativity in the guise of nuclear domesticity or the language of family itself. However, what if we engage with these autobiographical family trees in the philosophical sense of the term ‘genealogies,’ as an intellectual endeavor of critically drawing attention to the conditions under which origin is delineated (

Rak 2017, p. 3)? They can provide an excellent starting point for truly queer, entangled genealogies that ‘out’ the biologistic, hetero or homonormative ways we might understand and narrate where we are from and where we belong.