Abstract

Due to the advancements in real-time information communication technologies and sharing economies, rideshare services have gained significant momentum by offering dynamic and/or on-demand services. Rideshare service companies evolved from personal rideshare, where riders traveled solo or with known individuals, into pooled rideshare (PR), where riders can travel with one to multiple unknown riders. Similar to other shared economy services, pooled rideshare is beneficial as it efficiently utilizes resources, resulting in reduced energy usage, as well as reduced costs for the riders. However, previous research has demonstrated that riders have concerns about using pooled rideshare, especially regarding personal safety. A U.S. national survey with 5385 participants was used to understand human factor-related barriers and user preferences to develop a novel Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM). This model used a covariance-based structural equation model (CB-SEM) to identify the relationships between willingness to consider PR factors (time/cost, privacy, safety, service experience, and traffic/environment) and optimizing one’s experience of PR factors (vehicle technology/accessibility, convenience, comfort/ease of use, and passenger safety), resulting in the higher-order factor trust service. We examined the factors’ relative contribution to one’s willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR. Privacy, safety, trust service, and convenience were statistically significant factors in the model, as were the comfort/ease of use factor and the service experience, traffic/environment, and passenger safety factors. The only two non-significant factors in the model were time/cost and vehicle technology/accessibility; it is only when a rider feels safe that individuals then consider the additional non-significant variables of time, cost, technology, and accessibility. Privacy, safety, and service experience were factors that discouraged the use of PR, whereas the convenience factor greatly encouraged the acceptance of PR. Despite the time/cost factor’s lack of significance, individual items related to time and cost were crucial when viewed within the context of convenience. This highlights that while user perceptions of privacy and safety are paramount to their attitude towards PR, once safety concerns are addressed, and services are deemed convenient, time and cost elements significantly enhance their trust in pooled rideshare services. This study provides a comprehensive understanding of user acceptance of PR services and offers actionable insights for policymakers and rideshare companies to improve their services and increase user adoption.

1. Introduction

Vehicle ridesharing as a service was first documented in the U.S. during World War I (1914–1918) [1]. During WWI, the U.S. was in a recession, and as a result, individuals used jitney. Jitney is an unregulated taxi or bus service that carries travelers over a regular route on a flexible schedule [2]. Jitney’s popularity grew because of its affordability, and this mode of transportation was faster than a streetcar [3]. As the number of jitney vehicles increased, there were concerns about overcrowding, safety, volatility of the service, and fares [4]. After WWI, ridesharing lost popularity due to increased personal vehicle availability and growing concerns about sharing a ride. The second noticeable rideshare increase was during World War II (1939–1945). There was a push from the U.S. federal government for citizens to use ridesharing to conserve resources for the war effort [5]. In the workplace, forming ridesharing committees was encouraged, as well as keeping work shifts flexible to allow employees to find and use rideshares to reduce traffic congestion and resources. The government educated carpoolers to be aware of the impact of their individual behaviors, such as being late, poor manners, or a lack of personal hygiene, which could lead to the failure of rideshare [6]. Similar to the period following WWI, rideshare lost its popularity after WWII. For several decades, from the late 1960s to early 1980s, rideshare usage or carpooling was stable due to high fuel price hikes, but by 1990, there was a decline in rideshare usage. The decline was primarily due to a decrease in fuel prices and, consequently, an increase in personal vehicles [7].

Due to advancements in information and communication technologies, rideshare services have become a more reliable form of transportation. During the 1980s and 1990s, there was a rise in the number of personal computers in the U.S. In 1985, about 9% of households had computers, whereas by the year 2000, more than 50% of American families had a computer in their homes [8]. Along with the rise of personal computers, Internet usage also increased. Later, there was an increase in smartphone usage and advancements in GPS services. Apple sold approximately 1.4 million iPhones worldwide in its first year, 2007, and 11.6 million more iPhones were sold in 2008 [9]. By 2018, the percentage of Americans who owned smartphones grew to 81% compared to 35% in 2011 [10]. The technological advancements associated with smartphones and wireless information communication provided the foundation for the transmission of real-time information through smartphones, which had a significant impact in enabling a sharing economy in transportation.

A sharing economy, or collaborative consumption, is “the peer-to-peer-based activity of obtaining, giving, or sharing access to goods and services, coordinated through community-based online services” [11]. According to a comprehensive literature review on sharing economy by Hossain [12], the concept of a sharing economy has received significant attention from scholars, practitioners, and policymakers. A sharing economy helps to efficiently utilize the available resources and therefore improves sustainability. Some of the attributes of a sharing economy are a lack of ownership (in this case, of one’s own vehicle), temporary access, and the reallocation of physical goods or tangible assets such as time or money [13]. A Pew Research Center survey of 4787 U.S. participants highlights that 72% of adults have used some form of shared economy service [14]. Sharing economies are made possible through multiple technological developments that have simplified the sharing of both physical and nonphysical goods and services through the availability of various internet-based information systems [11]. For example, for several decades, Blockbuster was known for its movie rental retail operation, where movies were shared by multiple users. However, the rise in shared access using digital media, such as Netflix, has vastly increased the sharing economy [15]. The integration of the sharing economy with information communication technologies created new business opportunities and companies, such as Airbnb and Uber, which are widely used worldwide [12]. Airbnb, which started in 2008, is a digital marketplace in which individuals share rooms in their homes, where Airbnb profits from the brokerage fee [16]. Similarly, in the transportation domain, the integration of the internet, GPS-based location services, and software Apps in smartphones enabled third-party service providers to develop innovative services for transportation options including internet-based, dynamic ridesharing systems (Feldman, 2002).

Using the advancement of information communication technologies and end-users’ growing familiarity with smartphone applications, rideshare service companies first started offering on-demand personal rideshare services. Then, pooled rideshare (PR) on-demand services were offered. With a personal rideshare, the user can travel solo or with individuals they know, whereas with pooled rideshare, the user may travel with one or multiple individuals whom they do not know with multiple pick-up and/or drop-off locations. There are numerous rideshare platforms available throughout the world, including, but not limited to, Uber and Lyft in the U.S., DiDi in China [17], Ola cabs in India [18], Grab in Southeast Asia [19], and Chauffeur Privé in France [20]. Uber offers services worldwide and is currently the largest rideshare service provider [21]. According to Uber’s 2022 annual report, their services are available in more than 10,000 cities across 72 countries [22]. There was a 31% increase in the number of bookings from 2018 to 2019 [23]. The number of trips increased annually, with the exception of 2020, the year of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a 57% increase in Uber’s gross bookings in 2021 compared to the year 2020.

User motivation, which includes, but is not limited to, convenience, flexibility, interaction, time, and economic benefits are important for the success and sustained growth of sharing economies such as rideshare services [12,24]. Hossain [12] highlights that other factors can be economic, political, environmental, social, and technological factors, and for the service providers, the motivations are earning profit and, in some instances, contributing to sustainability. Rideshare services can help to reduce traffic congestion and lower the environmental impact; however, there are challenges in ridesharing [25]. Travelers have concerns about using rideshare services due to privacy and safety [26]. Rideshare service providers must ensure that these critical items are prioritized in their service experience. Due to the increase in safety concerns using rideshare, policymakers worldwide are trying to establish proper guidelines for rideshare service companies. For example, in the U.S., Sami’s Law was enacted in 2023 [27], which ensures that rideshare service companies follow government safety requirements. The legislation mandates that the Government Accountability Office must provide Congress with a report every two years containing findings from a study on: (1) the occurrence of deadly and non-deadly physical and sexual assaults on rideshare drivers by passengers and on passengers by drivers during the previous two years; (2) the details and scope of the background checks performed on potential rideshare drivers; and (3) the safety measures implemented by ridesharing businesses to ensure the wellbeing of both riders and drivers.

User acceptance of personal rideshare is still lower compared to the use of one’s own personal vehicle. According to the 2018 American Community Survey (ACS), 76.3% of Americans used their personal vehicle when commuting to work, in comparison to only 9% who shared a vehicle for their commute [28]. Research has been conducted on users’ motivational factors, as well as the barriers, in using pooled rideshare [21,24,29,30,31,32,33].

The purpose of this study was to develop a model to predict the user acceptance of pooled rideshare by understanding users’ concerns and preferences. The investigation was based on a national survey, with a robust sample of over 5000 U.S. participants, where the data were analyzed using structural equation modeling. The following sections present the factors influencing the utilization of pooled rideshare (PR) services. The model builds on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) models, defining the user trust in service, attitudes, and acceptance of PR. Then, our lab’s previous research concerning the factors influencing users’ willingness to consider pooled rideshare services and factors that contribute to enhancing users’ experiences are described. The following sections will summarize 14 hypotheses that connect these factors to users’ trust, attitudes, and acceptance of pooled rideshare, using responses from 5385 participants in a national online survey. This study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of user acceptance of PR services and to offer actionable insights for policymakers and rideshare companies to improve their services and increase user adoption.

3. Methods

3.1. Survey Design

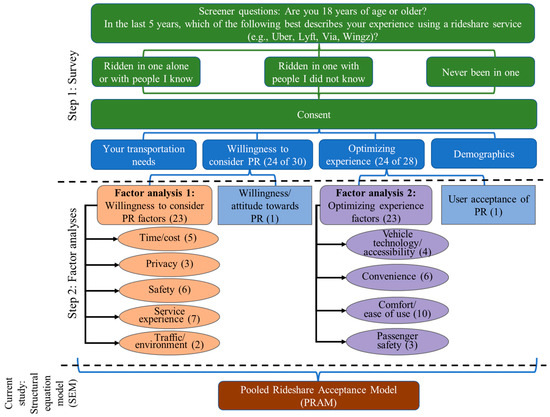

This study was part of a larger U.S. Department of Energy survey study. The online survey was conducted across the U.S., with seven targeted cities plus a national sample. The total number of participants was 5385. There were 2000 participants’ data collected from the national sample, and 3385 participants’ data obtained from Atlanta (500), Austin (501), Chicago (500), Detroit (500), New York City (500), San Francisco (500), and Upstate of South Carolina (384). As shown in Figure 2, in the survey’s design, screening questions ensured that potential participants were 18 years of age or older and their consent was obtained. A baseline of their experience of using rideshare services was recorded. Data were collected from participants who have ridden with individuals they know (46.6%), ridden with individuals whom they do not know (14.1%), or have never used rideshare services (39.3%) in the last 5 years.

Figure 2.

Step 1 displays the structure of the survey. The numbers in parentheses are the number of survey items used in each section of the Structural Equation Model (SEM). Step 2 shows the factors identified from the two factor analyses and the two items (willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR) used as response variables in the SEM. The SEM analysis led to the creation of the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM).

The your transportation needs section of the survey explored participants’ needs, as well as their experiences with various transportation services, including personal and pooled rideshares. Then, participants reported their willingness to consider utilizing a pooled rideshare in the willingness to consider PR section. Participants determined which factors influence their decisions to utilize or not utilize pooled rideshare. Then, questions about optimizing one’s experience were completed in the optimizing experience section to provide insight into which factors will influence their decisions to utilize pooled rideshare in the future. The final section related to demographics. See Figure 2 an overview of the survey structure, and for more detailed information on the survey, see [62,63].

This study focuses on structural equation model (SEM) analysis, where the inputs were extracted from two sections of the survey, as shown in Figure 2. The willingness to consider PR and optimizing experience sections were used to develop the SEM’s conceptual model. Based on our team’s previous research [62], from the willingness to consider PR section, the 23 items that were included in the factor analyses were used for the current SEM analysis, and 1 question was used as a response variable. Similarly, from the optimizing experience section [63], all 23 items included in the factor analyses were used for the current SEM analysis, and 1 question was used as a response variable.

3.2. Data Analysis Process

Structural equation modeling (SEM) includes various statistical methodologies that aim to estimate a network of causal relationships among latent variables/factors and response variables [75]. The analysis for this study is based on covariance-based (CB) SEM, using maximum likelihood estimation. Maximum likelihood is a method of estimating the parameters of the model based on the probability distribution of the given data. CB-SEM is appropriate when the goal is theory-based hypotheses exploration, theory confirmation, or comparison of alternative theories [76,77]. Given the large sample size and based on the central limit theorem, where the distribution of sample means is close to a normal distribution, univariate and multivariate normality may be less of a concern [78,79]. However, to be conservative, we used the bootstrapping technique with 1000 random samples for the maximum likelihood estimation. Bootstrap sampling is a technique that involves drawing sample data repeatedly [80].

SEM is a two-step process consisting of a measurement model and a structural model [81]. The measurement model examines the relationship between factors and their measures. The structural model examines the relationship between the different factors and response variables. The measurement model was analyzed before proceeding to the structural model. This study focuses on the structural model, which makes use of measurement models that have already been examined in the previous two factor analysis papers [62,63]. The previous measurement models used covariance-based techniques, so it was logical to use a covariance-based technique for the additional SEM analysis.

The CB-SEM analysis was conducted in R, a statistical computing platform, using the lavaan package [82,83]. To evaluate the model fit, various goodness-of-fit indices were used. Based on the existing literature, the goodness-of-fit indices should meet the following criteria: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.8 [48], Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 [84], Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.08 [85], Goodness-of-fit Index (GFI) > 0.93 [85], and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.8 [48].

As the study included a large and diverse sample of 5385 participants from across seven targeted cities, plus a national sample, the data set provided a variety of perspectives and backgrounds, thereby ensuring heterogeneity in the responses. This broad scope captured a certain degree of heterogeneity regarding geography, ridesharing experiences, and demographic characteristics. Moreover, applying the CB-SEM technique allowed for the exploration of the complex network of relationships among latent variables, providing a more in-depth understanding of the underlying factors. The bootstrapping technique with 1000 random samples for maximum likelihood estimation added further robustness to the analysis by considering the potential variability within the sample.

4. Results of the Structural Model

4.1. Fitting the Model

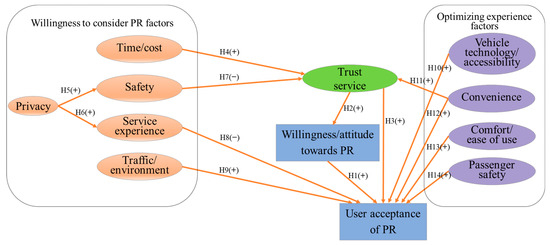

The conceptual model, shown in Figure 1, was considered a baseline to conduct exploratory SEM rather than confirming a conceptual model fit. The goal of the SEM was to obtain a model that determined the best model fit indices using the most optimal path relationships. The SEM was conducted using multiple iterations to obtain the best model fit. The SEM fit indices criteria were met after five iterations, at which point the model fit met the goodness-of-fit measurement criterion. The fifth iteration model was statistically significant (χ2 (1041) = 16347.1, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.893, RMSEA = 0.052, SRMR = 0.055, GFI = 0.946, TLI = 0.884).

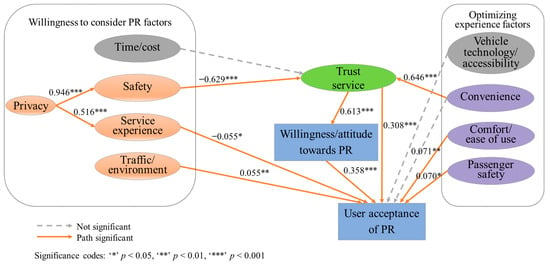

As shown in Figure 3, out of the 14 original hypotheses, the optimized model revealed that 11 of the hypothesized paths were supported. The two non-significant factors were time/cost and vehicle technology/accessibility. The time/cost factor from willingness to consider PR and vehicle technology/accessibility from optimizing experience factors showed no significance in the model. After observing the insignificance of the time/cost factor, different configurations of the model were explored to see whether time/cost had a direct/indirect significant influence on either willingness/attitude towards PR or user acceptance of PR; however, in both of those cases, the overall model did not provide a satisfactory fit.

Figure 3.

Results of SEM analysis model for user acceptance of PR.

Table 2 provides the significant regression paths of the final model. First, the significant willingness to consider PR factors were reported. The privacy factor had a significant influence on both the safety (β = 0.946, z = 23.994, p < 0.001) and service experience (β = 0.516, z = 18.884, p < 0.001) factors, indicating that privacy had a positive relationship with both safety and service experience. The safety factor (β = −0.629, z = −7.810, p < 0.001) had a significant negative influence on trust service. The service experience (β = −0.055, z = −1.977, p < 0.05) and traffic/environment (β = 0.055, z = 2.753, p < 0.01) factors had a significant influence on user acceptance of PR. In addition, service experience had a negative relationship with user acceptance of PR, while traffic/environment had a positive relationship with user acceptance of PR.

Table 2.

List of the SEM’s significant regression paths in the order in which they are explained.

Next, the significant optimizing experience factors were reported. The convenience factor (β = 0.646, z = 4.250, p < 0.001) had a significant positive influence on trust service. The comfort/ease of use (β = 0.071, z = 2.582, p < 0.01) and passenger safety (β = 0.070, z = 2.403, p < 0.05) factors had a significant influence on user acceptance of PR. The comfort/ease of use factor had a positive relationship with user acceptance of PR, and passenger safety had a positive relationship with user acceptance of PR.

Finally, the remaining factor, trust service, along with the two response variables (willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR) are discussed. The trust service factor had a significant positive influence on both willingness/attitude towards PR (β = 0.613, z = 9.674, p < 0.001) and user acceptance of PR (β = 0.308, z = 6.909, p < 0.001). The willingness/attitude towards PR (β = 0.358, z = 21.297, p < 0.001) factor had a significant positive influence on user acceptance of PR.

4.2. Effect Size Calculations

After determining the significance of each factor, it is then beneficial to evaluate the model’s explanatory power. This is accomplished by evaluating the magnitude of each factor’s influence on the next factor on its path; therefore, R2 values were calculated for the four factors with a predictive variable (privacy → safety, privacy → service experience, safety → trust service, and convenience → trust service). In addition, R2 values were calculated for the two response variables (willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR). The objective was to obtain the relationship between the factors and response variable; if a model has an R2 value greater than 0.3, then that model has good explanatory power [86].

The R2 value for safety was 0.676, where 67.6% of the variability observed in the safety factor was explained by the privacy factor. The R2 value for service experience was 0.889, where 88.9% of the variability observed in the service experience factor was explained by the privacy factor. The R2 value for trust service was 0.333, where 33.3% of the variability observed in the trust service factor was explained by the combination of the safety and convenience factors. The R2 value for willingness/ attitude towards PR was 0.375, where 37.5% of the variability was explained by the trust service factor. Finally, user acceptance of PR had an R2 value of 0.439, where 43.9% of the variability is explained by five factors (service experience, traffic/environment, comfort/ease of use, passenger safety, and trust service), as well as one response variable, willingness/attitude towards PR. These R2 values provide additional support for the user acceptance of the PR model.

The R2 values were then used to calculate the Cohen’s f2 effect sizes, as shown in Table 2. Examining Cohen’s f2 is beneficial when evaluating a model to determine the magnitude of each independent variable’s value to the model. Privacy had a large effect on safety and service experience. Safety and convenience had a large effect on trust service. Trust service, in turn, had a large effect on willingness/attitude towards PR. While there are five factors and one response variable that influence user acceptance of PR, the trust service factor and the willingness/attitude towards PR response variable had a small effect on the user acceptance of PR. The remaining four factors had a negligible impact in comparison.

4.3. Mediating (Indirect) Effects

A mediator is a variable in the causal path that helps to explain the relationship between the independent and dependent variables [87,88,89]. As summarized in Table 3, this full model has four mediators (safety, trust service, willingness/attitude towards PR, and service experience), which contributed to 12 paths. The analysis revealed that all of the possible mediated (indirect) effects were significant. The independent variables were privacy, safety, convenience, and trust service.

Table 3.

Results of mediating effects organized by each of the four independent variables: privacy, safety, convenience, and trust service.

As an independent variable, the privacy factor had a negative indirect effect on the dependent variables trust service, willingness/attitude towards PR, and user acceptance of PR. Privacy (β = −0.595, z = −6.912, p < 0.001) had a negative indirect effect on trust service, mediated through safety. Privacy (β = −0.364, z = −13.179, p < 0.001) had a negative indirect effect on willingness/attitude towards PR, mediated through safety and trust service. Privacy (β = −0.183, z = −10.231, p < 0.001) had a negative indirect effect on user acceptance of PR, mediated through safety and trust service. Privacy (β = −0.131, z = −11.211, p < 0.001) had a negative indirect effect on user acceptance of PR, mediated through safety, trust service, and willingness/attitude towards PR. Privacy (β = −0.029, z = −2.004, p < 0.05) had a negative indirect effect on user acceptance of PR, mediated through service experience.

Similar to the privacy factor, as an independent variable, the safety factor had a negative indirect effect on the dependent variables willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR. Safety (β = −0.385, z = −14.109, p < 0.001) had a negative indirect effect on willingness/attitude towards PR, mediated through trust service. Safety (β = −0.194, z = −9.886, p < 0.001) had a negative indirect effect on user acceptance of PR, mediated through trust service. Safety (β = −0.138, z = −11.992, p < 0.001) had a negative indirect effect on user acceptance of PR, mediated through trust service and willingness/attitude towards PR.

In contrast to the privacy and safety factors, as independent variables, the convenience and trust service factors had a positive indirect effect on its dependent variables. The convenience factor had a positive indirect effect on the dependent variables: willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR. Convenience (β = 0.396, z = 2.807, p < 0.01) had a positive indirect effect on willingness/attitude towards PR, mediated through trust service. Convenience (β = 0.199, z = 2.659, p < 0.01) had a positive indirect effect on user acceptance of PR, mediated through trust service. Convenience (β = 0.142, z = 2.809, p < 0.01) had a positive indirect effect on user acceptance of PR, mediated through trust service and willingness/attitude towards PR. Next, as an independent variable, the trust service factor had a positive indirect effect on the dependent variable, user acceptance of PR. Trust service (β = 0.22, z = 8.948, p < 0.001) had a positive indirect effect on user acceptance of PR, mediated through willingness/attitude towards PR.

In summary, when the privacy and safety factors were considered as the independent variables, they had negative indirect effects on all their dependent variables, whereas the convenience and trust service factors had positive indirect effects on their dependent variables.

4.4. Higher-Order Factor (Trust Service) and Multicollinearity Assessment

Trust service was theorized in the conceptual model as a higher-order factor that would be identified during the SEM analysis. The higher-order factor was computed by considering the time/cost, safety, and convenience factors as indicators. As a higher-order factor, trust service needed to be treated as a measurement model, and the collinearity validation was conducted before completing the structural analysis, where trust service was considered as a dependent variable. A multicollinearity problem occurs when multiple independent variables (predictors) are highly correlated with each other. Table 4 shows the variance inflation factor (VIF) that helped to diagnose whether there were any multicollinearity problems when predicting trust service. All of the independent variable VIF values—time/cost = 2.7, safety = 2.1, and convenience = 1.9—were below 5, indicating a low correlation between them [90]. Therefore, trust service had no multicollinearity problems amongst its independent variables as a dependent variable.

Table 4.

Multicollinearity assessment when predicting trust service.

Similar to trust service, for the dependent variable user acceptance of PR, there were multiple independent variables contributing to the regression analysis. Therefore, a multicollinearity assessment was completed for the dependent variable user acceptance of PR. The VIF values for the independent variables (Table 5) were service experience = 5.6, traffic/environment = 2.8, trust service = 6.4, willingness/attitude towards PR = 1.9, comfort/ease of use = 6.4, and passenger safety = 6.4. The traffic/environment and willingness/attitude towards PR VIF values were below 5, indicating a low correlation. The service experience, trust service, comfort/ease of use, and passenger safety VIF values were below 6.5, which were below the acceptable threshold of 10. As there were seven independent variables, it was important to ensure that there was not a high correlation between these independent variables. If any VIF value were above 10, researchers would consider that to be a high correlation, and as a result, the estimation may not be reliable. That is why researchers recommend a VIF value below 10 [78,91,92,93]. Our data meet this recommendation.

Table 5.

Multicollinearity assessment when predicting user acceptance of PR.

5. Discussion

The goal of this study was to develop a model to predict U.S. travelers’ pooled rideshare (PR) acceptance using human factor considerations. The study surveyed 5385 participants across the U.S., plus seven targeted cities. This study utilized the factors identified from two of our team’s previous research papers examining users’ willingness to consider PR [62] and optimizing experience of PR [63]. The willingness to consider PR study identified five factors: time/cost, privacy, safety, service experience, and traffic/environment. The optimizing experience study identified four factors: vehicle technology/accessibility, convenience, comfort/ease of use, and passenger safety. In this study, a structural model was created to identify the causal relationships between these factors, resulting in a higher-order factor, trust service, and identifying all of the factors’ relative contributions to willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR.

A conceptual model was established using the complex relationship between the ten factors/latent variables (time/cost, privacy, safety, service experience, traffic/environment, trust service, vehicle technology/accessibility, convenience, comfort/ease of use, and passenger safety) and two response variables (willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR). While 14 potential paths were explored between the variables, the final optimized model identified 11 of the 14 paths as being significant. Further investigation of the model revealed the mediated (indirect) effects, which explain the indirect relationships that exist between the variables. Based on the model’s direct and indirect effects, the different factors’ relative contribution to the willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR can be explained. Privacy, safety, trust service, and convenience factors showed strong significance in the model. The model’s only two non-significant factors were time/cost and vehicle technology/accessibility, which suggests that their importance was relatively low compared to the other factors.

The final model explained the 11 hypotheses and met the required goodness-of-fit measurements criterion. The first hypothesis (H1) stated that users with a favorable attitude towards PR are positively correlated with the likelihood of accepting the service. The result suggested a positive direct relationship between the willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR. This finding is consistent with other studies derived from the Technology Acceptance Model, indicating that a user’s attitude generally influences their acceptance of a technology/service [32,44,46]. The second hypothesis (H2) stated that a stronger level of trust in PR services is associated with more favorable attitudes and willingness to use PR. The finding demonstrates a positive direct relationship between trust service and willingness/attitude towards PR. Trust in the rideshare services is important for the users to have a positive belief, which is also highlighted in other rideshare service studies [24,32]. Ma et al. [32] mention that trust in the rideshare service and trust in multiple drivers form a cumulative trust that is significant for the user to continue using the personal rideshare service. For the pooled rideshare service, this study found that the passengers’ trust is significant if one is to share a ride with someone they do not know, which is a critical element for pooled rideshare services.

The third hypothesis (H3) stated that greater trust in PR services results in increased adoption and acceptance of PR. The result suggested a positive direct relationship between trust service and user acceptance of PR. In sharing economy research, trust in unknown persons and services is an essential prerequisite for success in a sharing economy [16,94]. For example, Airbnb acts as a broker and operates an online marketplace focused on short-term homestays between strangers. The research on Airbnb usage suggests that trust in its service platform leads to greater usage of its service [16]. In this study, the results suggest that trusting in the service is important for user acceptance of PR. Along with directly influencing willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, the trust service factor was found to be a significant mediator. With the trust service factor as a mediator, the privacy and safety factors had a negative indirect relationship with willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR. Similarly, with the trust service factor as a mediator, the convenience factor had a positive indirect relationship with willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR. The acceptance of pooled rideshare relies on the rideshare service platform, which must ensure that riders trust its services with multiple riders and create favorable conditions [95]. If the user does not feel safe during the ride or if any safety or privacy violations occur while using the ride, it will strongly influence users not to use PR.

The next two significant hypotheses (H5 and H6) were related to the privacy factor. The fifth hypothesis (H5) stated that users who prioritize privacy will have more concerns about safety when sharing rides with unknown riders. The result suggested a positive direct relationship between the privacy and safety factors. As pooled ridesharing requires the user to travel with multiple people whom they do not know, privacy inside the vehicle will influence their perception of safety. The user expects the rideshare companies to ensure that there is no harm or danger when sharing a ride [21,32]. The sixth hypothesis (H6) stated that users who prioritize privacy will expect a higher service experience during the ride. The result suggests a positive direct relationship between the privacy and service experience factors. As the majority of travelers in the U.S. prefer a personal vehicle for commuting, this finding suggests that the user will desire privacy during PR and wants that privacy to be as similar as possible to what they experience in their own private vehicle. Rideshare companies likely need to enhance their service experience by offering better privacy options to increase PR use.

Next, the seventh hypothesis (H7) stated that users with higher concerns about safety will have lower trust in PR services. The result suggests a negative direct relationship between the safety and trust service factors. This means that safety is the primary concern for users who do not accept the PR concept. As highlighted in several studies [32,33,96,97,98] as well as in Uber and Lyft’s safety reports [99,100], physical and sexual assaults have happened in the past. These incidents tend to cause the user to have reduced trust in the rideshare service, as reflected in this study. When using pooled rideshares, it is likely that a vehicle will detour from their original path to pick up and drop off others; therefore, the user has to travel an extra distance, possibly in an unfamiliar location. With the safety factor as a mediator, the privacy factor had a negative indirect relationship with trust service. Compared to using a personal vehicle, where there is privacy and a preference for traveling alone, the pooled rideshare can create privacy concerns that negatively influence a user’s trust in the service. Feeling safe is of the highest importance for the users; therefore, rideshare companies must ensure passengers that there is a level of safety between the users and the service.

In the two subsequent hypotheses, the service experience and traffic/environment factors directly influenced the user acceptance of PR. The eighth hypothesis (H8) stated that the higher concerns regarding the service experience of PR compared to alternative transportation options result in a decrease in the user acceptance of PR. The result suggested a negative direct relationship between service experience and user acceptance of PR. In the service experience factor, the items with the highest factor loadings were related to public transportation availability. This suggests that unless there is a strong justification for the rideshare advantage, the user may still prefer public transportation over pooled rideshare, as reflected in other studies [101,102]. The ninth hypothesis (H9) stated that users with higher concerns for traffic congestion and environmental impact leads to an increase in user acceptance of PR. The result suggested a positive direct relationship between traffic/environment and user acceptance of PR. The widespread adoption of ridesharing can take vehicles off the road, reduce traffic congestion, protect air quality, lower vehicle emissions, and reduce the need for infrastructure investment [70,101,103,104]. The users’ concerns about traffic congestion and thoughts that using rideshare will improve the environment influenced their acceptance of PR directly.

The next significant hypothesis is related to the convenience factor. The eleventh hypothesis (H11) stated that the optimized convenience experience will lead to increased trust in the PR service. The result suggested a positive direct relationship between the convenience and trust service factors. Unlike the safety factor, the convenience factor can strongly influence the user to gain trust in the PR services. The increase in trust will help users to formulate a positive opinion of PR [46]. Rideshare companies need to carefully focus on the topics that fall within the convenience factor, which can increase ridership. In this study, the results suggest that ride affordability and information about the ride (e.g., cost, route, time, service transparency, and user communication with the outside world) were important. Inbar et al. [105] conducted similar research concerning passengers and found that passengers like to have continuous information about their trip as well as continuous communication with the outside world. Similar results were also found in the shared autonomous vehicle research, where multiple users share a ride without a driver [68,106]. The convenience factor indirectly influenced both willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, mediated through trust service, indicating its influence on users’ willingness to use PR. Rideshare companies should incorporate user-centered services that are reliable to provide a convenient ride.

The two remaining significant hypotheses were related to comfort/ease of use and passenger safety factors. The thirteenth hypothesis (H13) stated that optimized comfort/ease of use experience will lead to increased user acceptance of PR. The result suggested a positive direct relationship between comfort/ease of use and user acceptance of PR. As Mayr [107] suggested in the traveling comfort theory, the user should have a comfortable experience within the vehicle and a comfortable ease of use experience when scheduling a ride. The user expects a high level of physical comfort for a convenient ride [108]. Rideshare companies should focus on customized heating, ventilation, and air condition (HVAC) systems for each user, enough physical space, ergonomic seats, and in-built infotainment, as well as a better view of the outside environment. The fourteenth hypothesis (H14) stated that the passenger safety experience will lead to increased user acceptance of PR. The result suggested a positive direct relationship between passenger safety and user acceptance of PR. As seen earlier, the safety factor is the greatest priority for the user. Therefore, the safety improvement features in the rideshare service are essential for sustained service growth. Companies such as Uber and Lyft have been consistently incorporating new features to increase the safety of their users. For example, Uber has an emergency assistance button to call authorities if the user needs immediate help. Friends and family can follow the user’s route and will know when the user arrives at their destination. In addition, advanced features such as RideCheck use vehicle sensors and GPS data to detect if a trip goes off-course or if a possible crash has occurred [109].

The first non-significant factor in the model was time/cost, which is from the willingness to consider PR factors. Some studies suggest that the time and cost items are important for rideshare participation [24,70,104,110,111,112]. The previous studies have largely focused on time and cost with other factors, such as demographic features, the relationship between cost and time, vehicle automation, etc. This study focused on 46 items that were categorized into nine diverse factors to obtain the comprehensive motives of user willingness to accept PR. Given the safety and convenience factor’s significant contributions to trust service, the time/cost factor did not significantly influence trust service [24]. In this study, only the trust service factor influenced positive attitudes towards PR as it acted as a mediator for the privacy, safety, and convenience factors, which the users considered more important than the time/cost factor.

However, the survey items on the convenience factor focused on cost, travel time, wait time, and information about the ride. From the previous factor analysis, it is important to note that the items ‘The cost to share a ride is more affordable than other transportation’, ‘There is clear information about the ride (e.g., cost, route, time) before I book it’, and ‘I won’t be delayed by long detours’ had the highest factor loadings [63]. Specifically, 84% and 81.5% of the participants either ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’ with the latter two items, indicating their willingness to consider pooled rideshare services. Despite the time/cost factor’s lack of significance, the individual items related to time and cost were crucial when viewed within the context of convenience. This highlights that while users’ perceptions of privacy and safety are paramount for their attitude towards PR, once the safety concerns are addressed and the services are deemed convenient, time and cost elements significantly enhance their trust in pooled rideshare services. The findings complement the other research, which indicates that factors like reduced trip costs compared to alternatives are important in opting for pooled rideshare services [70]. Moreover, convenience features like shorter wait times and accessibility all the time, along with transparent communication and reliable services, further influence users’ decisions to share rides [25,33,64,68]. Amirkiaee et al.’s [24] rideshare acceptance model highlights that, along with trust, time and cost benefits significantly influence positive attitudes toward rideshare.

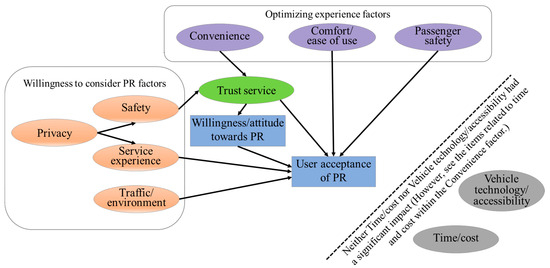

The second non-significant factor in the model was vehicle technology/accessibility, which is from the optimizing experience PR factors. This complements the findings in Amirkiaee et al.’s [24] rideshare acceptance model that the user may not be concerned about the vehicle’s energy source, whether it is propelled by electricity, gasoline, or another energy source. Regarding the automation of the vehicle, shared autonomous vehicles have found significance in autonomous vehicle development [106,110,111,113]; however, from the users’ point of view, it does not influence their acceptance of PR. Finally, after reviewing all of the hypotheses’ significances obtained from the analysis, the user acceptance pooled rideshare model using the human factors perspective, which is Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM), is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM): showing significant paths, with 10 factors (privacy, time/cost, safety, service experience, traffic/environment, vehicle technology/accessibility, convenience, comfort/ease of use, and passenger safety) and 2 response variables (willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR). Time/cost and vehicle technology/accessibility factors were not significant compared to the relative contribution of other factors.

6. Conclusions

This study was designed based on an online national survey in the U.S. with 5385 participants to increase the understanding of human factor- barriers and user preferences, which will provide foundational knowledge of the factors that affect individuals’ acceptance of pooled rideshare (PR). The covariance-based structural equation model (CB-SEM) was used to identify the causal relationship between the willingness to consider PR factors (time/cost, privacy, safety, service experience, and traffic/environment) and optimizing experience of PR factors (vehicle technology/accessibility, convenience, comfort/ease of use, and passenger safety), resulting in a higher-order factor, trust service, and eventually finding all of the factors’ relative contribution to willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, thereby developing a Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM). In the PRAM, the privacy, safety, trust service, and convenience factors showed significance, along with the comfort/ease of use, service experience, traffic/environment, and passenger safety factors. The only two non-significant factors in the model were (1) time/cost and (2) vehicle technology/accessibility, suggesting that users only consider the time, cost, technology, and accessibility variables when they feel safe in using it. Despite the time/cost factor’s lack of significance, individual items related to time and cost were crucial when viewed within the convenience factor [63]. This highlights that while user perceptions of privacy and safety are critical towards their attitude towards PR, once the safety concerns are addressed and the services are deemed convenient, time and cost elements significantly enhance users’ trust in pooled rideshare services. This is an important and consistent finding in the study, which makes a valuable contribution to the design of pooled rideshare services.

Privacy had a negative indirect influence on willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, mediated through safety and trust service. Privacy had a negative indirect influence on willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, mediated through service experience. Safety had a negative indirect influence on willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, mediated through trust service. The trust service factor had a positive direct influence on user acceptance of PR and a positive indirect influence, mediated through willingness/attitude towards PR. Convenience had a positive indirect influence on willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, mediated through trust service. The other factors from willingness to consider PR, such as service experience, had a negative direct influence on user acceptance of PR, and traffic/environment had a positive direct influence on user acceptance of PR. Similarly, the factors from optimizing experience, such as comfort/ease of use, had a positive direct influence on user acceptance of PR, and passenger safety had a positive direct influence on user acceptance of PR. In summary, the information about the ride (e.g., cost, route, time), service transparency, and user communication with the outside world greatly influence the acceptance of PR. The individual considers privacy, safety, and service experience as deterrent factors in using PR when compared with other modes of transportation. Rideshare service companies and policymakers must consider these factors as the highest priority in their policy to increase user acceptance of PR.

8. Future Research

In this study, the impact of the different moderators, such as gender, age, cities, educational background, prior rideshare experience, and employment status, are not considered in the pooled rideshare acceptance model. Further analysis will be conducted for these moderators’ influence on various factors contributing to the user acceptance of PR. One example of the need for this more comprehensive data analysis is the importance of examining the impact of previous rideshare experiences. Future research will examine potential variations in attitudes and acceptance levels between different groups (including but not limited to previous rideshare use, gender, age, income, location, employment status, and education) as moderators for the pooled rideshare acceptance model (PRAM). These future results may be able to highlight interventions aimed at promoting shared modes of mobility, particularly focusing on strategies to engage users who have never utilized a PR service. In particular, examining each of these groups of participants through a targeted approach will help to determine how each of the factors influence rideshare acceptance.

The model is developed based on a U.S. sample. The factors contributing to the user acceptance of PR can vary in different regions of the world. Therefore, the model can be used to further explore user acceptance of PR in different geographic areas. While this study focused on user willingness to accept pooled rideshare services, when considering different populations and ridesharing modes, governmental regulations may play a vital role in shaping perceptions and attitudes. The inclusion of such a factor in future research may offer a deeper understanding of pooled rideshare acceptance, especially considering diverse regulatory environments, the aftermath of COVID-19, and socio-economic contexts, along with the global efforts by policymakers to establish guidelines for global rideshare service companies. Given that the study employed a non-experimental design, future research may benefit from exploring alternative causal sequences and mechanisms. Such investigations could provide a deeper understanding of the dynamics influencing pooled rideshare acceptance [89,114].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J. and J.O.B.; methodology, R.G., J.O.B., H.S. and P.J.R.; software, R.G., H.S. and P.J.R.; validation, J.O.B., P.J.R., L.B., A.E. and K.K.; formal analysis, Y.J.; investigation, R.G., J.O.B., H.S., L.B. and K.K.; resources, J.O.B., R.G., H.S., L.B., A.E. and Y.J.; data curation, R.G. and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.; writing—review and editing, R.G. and J.O.B.; visualization, R.G., J.O.B. and H.S.; supervision, J.O.B.; project administration, Y.J.; funding acquisition, Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, grant number DE-EE0009205.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Clemson University (protocol code IRB2020-412 and date of approval 8 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions, e.g., privacy or ethical.

Acknowledgments

This research is based on work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) under the award DE-EE0009205. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Energy or the United States Government. The authors extend appreciation to Casey Jenkins, Timothy Jenkins, and Joseph Paul for their insights, assistance, and meticulous review of the data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

- Survey ©2023 J.D. Power. All Rights Reserved.

This appendix provides a list of the survey questions developed in collaboration with J.D. Power that allowed for the development of the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM). The following survey questions are a subset of the larger survey.

- Willingness/attitude towards PR question

- 1. Regardless of your past experience, would you be willing to consider utilizing a pooled rideshare, one in which you share the ride with people you don’t know who may join from multiple locations during the trip and drop off at different locations? (e.g., UberPool, Lyft Shared) ___Yes, ___No, ___Don’t know

- Willingness to consider PR factor questions

- (If item 1 was “Yes”, the following question was used) We would like to understand more of the reasons why you are willing to consider pooled rideshare. How important are each of the following travel time and cost factors in determining your willingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

- (If item 1 was “No” or “Don’t know”, the following question was used) We would like to understand more of the reasons why you are not willing to consider pooled rideshare. How important are each of the following travel time and cost factors in determining your unwillingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

| Rating Scale: 1 = Not at all important, 2 = Not very important, 3 = Important, 4 = Very important | ||||

| 2. Travel time from door to door (e.g., in car travel time to destination) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. Wait time (e.g., waiting for ride to arrive, another passenger pick up) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. Cost savings/incentives received for pooling the ride | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Cost of driving my personal vehicle (e.g., gas, maintenance, parking) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. On-time likelihood (e.g., risk of picking up others along the route that may modify your original arrival time) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- (If item 1 was “Yes”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following environmental factors in determining your willingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

- (If item 1 was “No” or “Don’t know”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following environmental factors in determining your unwillingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

| Rating Scale: 1 = Not at all important, 2 = Not very important, 3 = Important, 4 = Very important | ||||

| 7. Help to improve the environment (e.g., reduce pollution, reduce energy consumption) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. Help to reduce traffic congestion | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- (If item 1 was “Yes”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following social factors in determining your willingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

- (If item 1 was “No” or “Don’t know”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following social factors in determining your unwillingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

| Rating Scale: 1 = Not at all important, 2 = Not very important, 3 = Important, 4 = Very important | ||||

| 9. Chance to meet new people | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. Prefer to travel alone | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- (If item 1 was “Yes”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following personal safety factors in determining your willingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

- (If item 1 was “No” or “Don’t know”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following personal safety factors in determining your unwillingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

| Rating Scale: 1 = Not at all important, 2 = Not very important, 3 = Important, 4 = Very important | ||||

| 11. Traveling during the day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. Traveling at night | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13. Familiarity with travel vicinity | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14. Desire for privacy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15. Trust in the driver (e.g., unnecessary detour, theft, skills, physical safety) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16. Trust in other passengers (e.g., theft, illness, physical safety) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 17. I am with another person I know | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- (If item 1 was “Yes”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following reliability and accessibility factors in determining your willingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

- (If item 1 was “No” or “Don’t know”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following reliability and accessibility factors in determining your unwillingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

| Rating Scale: 1 = Not at all important, 2 = Not very important, 3 = Important, 4 = Very important | ||||

| 18. Other public transportation options are available | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 19. Trust that the rideshare will get me to my destination when I need to be there | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 20. Previous rideshare experience | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 21. Accessibility needs for passengers with disabilities | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 22. I don’t have access to other public transportation options | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- (If item 1 was “Yes”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following convenience factors in determining your willingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

- (If item 1 was “No” or “Don’t know”, the following question was used) How important are each of the following convenience factors in determining your unwillingness to utilize a pooled rideshare?

| Rating Scale: 1 = Not at all important, 2 = Not very important, 3 = Important, 4 = Very important | ||||

| 23. Convenience of driving my personal vehicle | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 24. Rideshare App ease of use to request a pooled ride | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 25. Ability to do other things during the ride | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 26. Other public transportation options are convenient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- Optimizing experience factors questions

- This next series of questions will help us understand what factors influence your willingness to utilize a pooled rideshare in the future.

- (MODE) Thinking about certain aspects of the vehicle or other riders using the rideshare service, please state how much you agree or disagree with the following statements: I would be more likely to choose a pooled rideshare if…

| Rating Scale: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, 4 = Strongly agree | ||||

| 27. The vehicle is automated and does not have a human driver. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 28. The vehicle is a battery-electric vehicle (only runs on electricity). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 29. The vehicle is cleaned/disinfected in between rides. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 30. The vehicle is accessible for passengers with disabilities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 31. I can ride with a person who is like me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 32. The other passenger is pre-screened by the rideshare service. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 33. A subscription service is available (i.e., fixed monthly cost for unlimited rides). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- (HMI) Considering how you might interact with the rideshare vehicle or service, please state how much you agree or disagree with the following statements: I would be more likely to choose a pooled rideshare if…

| Rating Scale: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, 4 = Strongly agree | ||||

| 34. The rideshare service app is easy to use. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 35. I can adjust the temperature in the vehicle to my liking. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 36. I can see a profile of the other passenger. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 37. I can adjust the seats in the vehicle for comfort. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 38. The vehicle design creates private spaces. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 39. I can call to request a ride instead of using the app. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 40. There is sufficient storage in the vehicle for all my belongings. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 41. I can sit where I want in the vehicle. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 42. The vehicle offers me information and entertainment throughout the experience. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 43. I had someone to help me with the service during my first time requesting a ride. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- (ROUTE) Please state how much you agree or disagree with the following statements: I would be more likely to choose a pooled rideshare if…

| Rating Scale: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, 4 = Strongly agree | ||||

| 44. The cost to share a ride is more affordable than other transportation. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 45. A ride is available 24/7. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 46. The other passenger is coming from or going to the same event/location as me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 47. I can provide information about my trip and location to my family and/or friends. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 48. There is clear information about the ride (e.g., cost, route, time) before I book it. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 49. I won’t be delayed by long detours. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- User acceptance of PR question

- 50. Assuming a pooled rideshare service meets all of your needs mentioned above, how willing are you to use a pooled rideshare when it is available to you?___Definitely will not, ___Probably will not, ___Probably will, ___Definitely will

References

- Rideshare History and Statistics. 2009. Available online: https://ridesharechoices.scripts.mit.edu/home/histstats/ (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Definition of Jitney. 2021. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/jitney (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Eckert, R.D.; Hilton, G.W. The Jitneys. J. Law Econ. 1972, 15, 293–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, A. ‘Roping the Wild Jitney’: The jitney bus craze and the rise of urban autobus systems. Plan. Perspect. 2006, 21, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N.D.; Shaheen, S.A. Ridesharing in North America: Past, Present, and Future. Transp. Rev. 2012, 32, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Office of Civilian Defense. The Trials of Travel: Transportation at the Bursting Point. 1942. Available online: https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/exhibits/ww2/Pages/services-transportation.aspx (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Ferguson, E. The rise and fall of the American carpool: 1970–1990. Transportation 1997, 24, 349–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.; Hans, J.D. Computers, the Internet, and Families. J. Fam. Issues 2001, 22, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vailshery, L. iPhone Sales by Year|Statista. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/276306/global-apple-iphone-sales-since-fiscal-year-2007/ (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Pew Research. 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Sharing economy: A comprehensive literature review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, S.; Koul, S.; Mishra, H.G. Acceptance of Ride-sharing in India: Empirical Evidence from the UTAUT Model. Int. J. Bus. Econ. 2021, 20, 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. The New Digital Economy: Shared, Collaborative and On Demand|Pew Research Center. 2016. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2016/05/19/the-new-digital-economy/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Nadler, S. The sharing economy: What is it and where is it going? Inst. Technol. Mass. 2014. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:16259632/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Zamani, E.D.; Choudrie, J.; Katechos, G.; Yin, Y. Trust in the sharing economy: The AirBnB case. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1947–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didi. 2021. Available online: https://www.didiglobal.com/ (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Ola Cabs. 2021. Available online: https://www.olacabs.com/ (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Grab. 2021. Available online: https://www.grab.com/sg/ (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Chauffeur Privé. 2021. Available online: https://chauffeurprive.mu/ (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Pratt, A.N.; Morris, E.A.; Zhou, Y.; Khan, S.; Chowdhury, M. What do riders tweet about the people that they meet? Analyzing online commentary about UberPool and Lyft Shared/Lyft Line. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 62, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uber Annual Report. 2022. Available online: https://stocklight.com/stocks/us/transportation-and-warehousing/nyse-uber/uber-technologies/annual-reports/nyse-uber-2022-10K-22671636.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Iqbal, M. Uber Revenue and Usage Statistics-Business of Apps. 2022. Available online: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/uber-statistics/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Amirkiaee, S.Y.; Evangelopoulos, N. Why do people rideshare? An experimental study. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 55, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurlock, C.A.; Sears, J.; Wong-Parodi, G.; Walker, V.; Jin, L.; Taylor, M.; Duvall, A.; Gopal, A.; Todd, A. Describing the users: Understanding adoption of and interest in shared, electrified, and automated transportation in the San Francisco Bay Area. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 71, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotti, A. Woman Sues Uber after Fellow Passenger Allegedly Stabbed Her during Shared Ride-Chicago Tribune. 2017. Available online: https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-uber-pool-attack-lawsuit-0406-biz-20170405-story.html (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Sami’s Law. 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1082/text (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Aevaz, R. 2018 ACS Survey. 2019. Available online: https://www.enotrans.org/article/2018-acs-survey-while-most-americans-commuting-trends-are-unchanged-teleworking-continues-to-grow-and-driving-alone-dips-in-some-major-cities/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Vivoda, J.M.; Harmon, A.C.; Babulal, G.M.; Zikmund-Fisher, B.J. E-hail (rideshare) knowledge, use, reliance, and future expectations among older adults. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 55, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Mcglynn, J.; Huang, Y.; Han, A. Trust Inference for Rideshare through Co-training on Social Media Data. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 December 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2532–2541, ISBN 9781728108582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaube, V.; Kavanaugh, A.L.; Perez-Quinones, M.A. Leveraging Social Networks to Embed Trust in Rideshare Programs. In Proceedings of the 2010 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Honolulu, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Ding, X.; Wang, G. Risk perception and intention to discontinue use of ride-hailing services in China: Taking the example of DiDi Chuxing. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 66, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarriera, J.M.; Álvarez, G.E.; Blynn, K.; Alesbury, A.; Scully, T.; Zhao, J. To Share or Not to Share: Investigating the social aspects of dynamic ridesharing. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2017, 2605, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.A.; Nelson, R.R.; Todd, P.A. Perceived Usefulness, Ease of Use, and Usage of Information Technology: A Replication. MIS Q. 1992, 16, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.; Morris, M. Dead Or Alive? The Development, Trajectory And Future of Technology Adoption Research. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2007, 8, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wixom, B.H.; Todd, P.A. A Theoretical Integration of User Satisfaction and Technology Acceptance. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, G. Translation and Validation of the Technology Acceptance Model and Instrument for Use in the Arab World; ACIS 2004 Proceedings; United Arab Emirates University: Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, 2004; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2004/105 (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Ghazizadeh, M.; Peng, Y.; Lee, J.D.; Boyle, L.N. Augmenting the Technology Acceptance Model with Trust: Commercial Drivers’ Attitudes towards Monitoring and Feedback. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2012, 56, 2286–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, N.; Hook, L. Technology acceptance model for safety critical autonomous transportation systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/AIAA 36th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 17–21 September 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osswald, S.; Wurhofer, D.; Trösterer, S.; Beck, E.; Tscheligi, M. Predicting information technology usage in the car: Towards a car technology acceptance model. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications (AutomotiveUI ’12). Association for Computing Machinery, Portsmouth, NH, USA, 17–19 October 2012; pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.; Nordin, S.M.; bin Bahruddin, M.A.; Ali, M. How trust can drive forward the user acceptance to the technology? In-vehicle technology for autonomous vehicle. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, C. Assessing Public Perception of Self-Driving Cars: The Autonomous Vehicle Acceptance Model. In Proceedings of the 24th international conference on intelligent user interfaces, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 16–20 March 2019; pp. 518–527. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Tao, D.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, R.; Zhang, W. The roles of initial trust and perceived risk in public’s acceptance of automated vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 98, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debernard, S.; Chauvin, C.; Pokam, R.; Langlois, S. Designing Human-Machine Interface for Autonomous Vehicles. IFAC-Pap. 2016, 49, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jönköping, W.S. User Acceptance in the Sharing Economy 30 PROGRAMME OF STUDY: IT, Management and Innovation An explanatory study of Transportation Network Companies in China Based on UTAUT2. 2017. Available online: https://figshare.utas.edu.au/articles/journal_contribution/Using_the_Technology_Acceptance_Model_in_Understanding_Academics_Behavioural_Intention_to_Use_Learning_Management_Systems/22944263/1 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Moon, J.; Shim, J.; Lee, W.S. Exploring Uber Taxi Application Using the Technology Acceptance Model. Systems 2022, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaigham, M.; Chin, C.P.-Y.; Dasan, J. Disentangling Determinants of Ride-Hailing Services among Malaysian Drivers. Information 2022, 13, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, M.; Der, A. Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: The adoption of mobile messaging application. Megatrend Rev. 2017, 14, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAE International. J3016B: Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles-SAE International. 2018. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/j3016_201806/ (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- Lee, J.D.; Moray, N. Trust, self-confidence, and operators’ adaptation to automation. Int. J. Human-Computer Stud. 1994, 40, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Moray, N. Trust, control strategies and allocation of function in human-machine systems. Ergonomics 1992, 35, 1243–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research. 1975. Available online: http://home.comcast.net/~icek.aizen/book/ch2.Pdf/ (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kozar, K.A.; Larsen, K.R.T. The technology acceptance model: Past, present, and future. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 752–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasman, L.R.; Albarracín, D. Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 778–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, R.; Sheridan, T.B.; Wickens, C.D. Situation Awareness, Mental Workload, and Trust in Automation: Viable, Empirically Supported Cognitive Engineering Constructs. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Mak. 2008, 2, 140–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Devinney, T.M.; Pillutla, M.M.; Long, C.P.; Sitkin, S.B.; Bevelander, D.; Page, M.J.; Puranam, P.; Vanneste, B.S.; Mills, P.K.; et al. A Formal Model of Trust Based on Outcomes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.; Krischkowsky, A.; Tscheligi, M. Modelling User-Centered-Trust (UCT) in Software Systems: Interplay of Trust, Affect and Acceptance Model. In Proceedings of the Trust and Trustworthy Computing: 5th International Conference, TRUST 2012, Vienna, Austria, 13–15 June 2012; Proceedings 5. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Gangadharaiah, R.; Rosopa, E.; Brooks, J.; Boor, L.; Kolodge, K.; Rosopa, P.; Jia, Y. An Exploration of Factors that Influence Willingness to Consider Pooled Rideshare. 2023; Manuscript Submitted forPublication. [Google Scholar]

- Gangadharaiah, R.; Su, H.; Rosopa, E.B.; Brooks, J.O.; Kolodge, K.; Boor, L.; Rosopa, P.J.; Jia, Y. A User-Centered Design Exploration of Factors That Influence the Rideshare Experience. Safety 2023, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malokin, A.; Circella, G.; Mokhtarian, P.L. How do activities conducted while commuting influence mode choice? Using revealed preference models to inform public transportation advantage and autonomous vehicle scenarios. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 124, 82–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoach, S.B.; Tiemann, T.K. Not driving alone? American commuting in the twenty-first century. Transportation 2012, 39, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Wu, C. Behavioral Responses to Dynamic Ridesharing Services. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Service Operations and Logistics, and Informatics, Beijing, China, 12–15 October 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1576–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.A.; Pratt, A.N.; Zhou, Y.; Brown, A.; Khan, S.M.; Derochers, J.L.; Campbell, H.; Chowdhury, M. Assessing the Experience of Providers and Users of Transportation Network Company Ridesharing Services; Clemson University: Clemson, SC, USA, 2019; p. 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluck, A.; Boateng, K.; Huff, E.W.; Brinkley, J. Putting Older Adults in the Driver Seat: Using User Enactment to Explore the Design of a Shared Autonomous Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 12th International ACM Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, AutomotiveUI, Washington, DC, USA, 21–22 September 2020; pp. 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, S.; Spyridakis, J.; Haselkorn, M.; Goble, B.; Blumenthal, C. Assessing users’ needs for dynamic ridesharing. Transp. Res. Rec. 1994, 1459, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, X. Ridesplitting is shaping young people’s travel behavior: Evidence from comparative survey via ride-sourcing platform. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 75, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, F.-Y.; Yu, T.H.-K.; Chen, H.-H. Purchasing intention and behavior in the sharing economy: Mediating effects of APP assessments. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, H.; Lee, C.; Brady, S.; Fitzgerald, C.; Mehler, B.; Reimer, B.; Coughlin, J.F. Autonomous Vehicles, Trust, and Driving Alternatives: A survey of consumer preferences. Mass. Inst. Technol AgeLab Camb. 2016, 1, 2012–2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sami’s Law—H. R. 4686. 2019. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/116/meeting/house/110062/witnesses/HHRG-116-PW12-Wstate-S000522-20191016.pdf/ (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- Mims, L.K.; Gangadharaiah, R.; Brooks, J.; Su, H.; Jia, Y.; Jacobs, J.; Mensch, S. What Makes Passengers Uncomfortable in Vehicles Today? An Exploratory Study of Current Factors that May Influence Acceptance of Future Autonomous Vehicles. In SAE Technical Paper Series; SAE: Detroit, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; Palumbo, F. Partial Possibilistic Regression Path Modeling; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S.P. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]