Procedure Negligence in Coastal Cargo: What Can Be Done to Reduce the Gap between Formal and Informal Aspects of Safety?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Previous Research

2.1. Formal and Informal Aspects of Safety

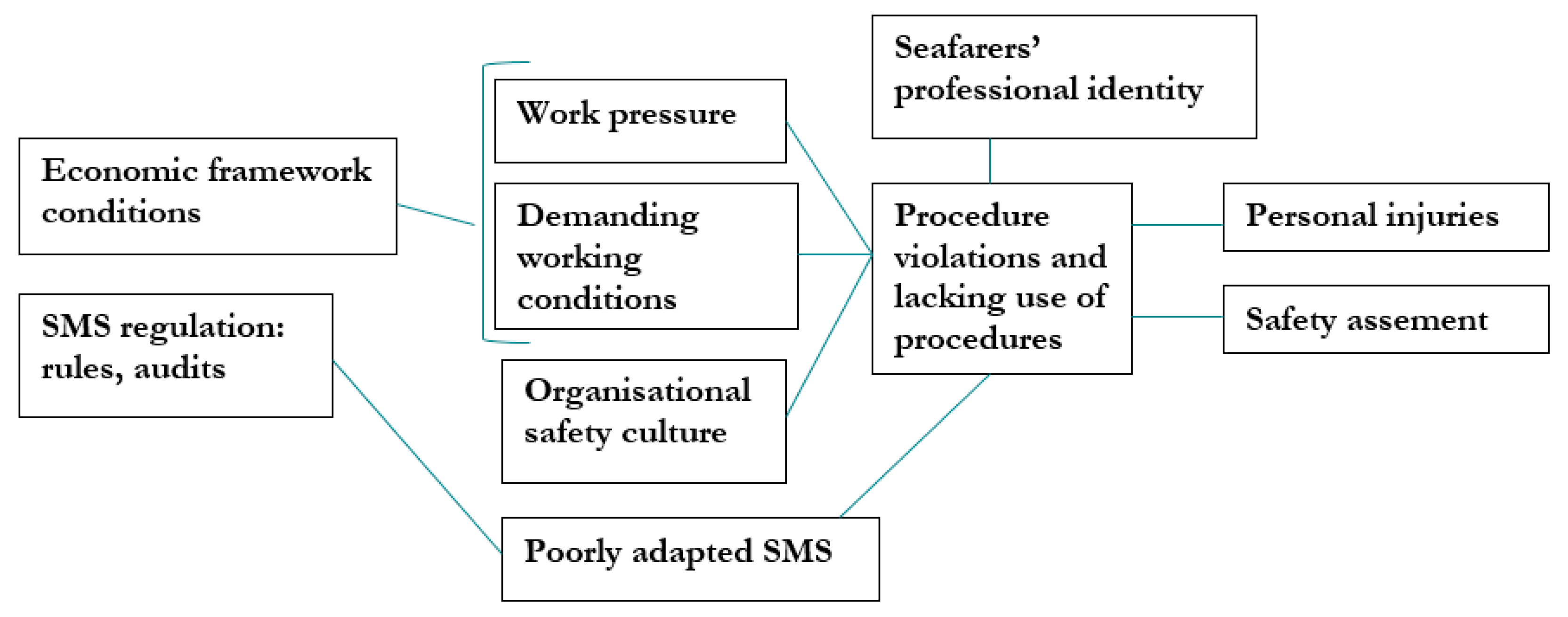

2.2. Causes of Procedure Negligence

2.3. Human Error

2.4. Organizational Causes

3. Methodological Approach

3.1. Interviews

3.2. Survey

3.2.1. Recruitment of Respondents

3.2.2. Sample

3.2.3. Survey Measures

- Background variables related to respondents: 7 questions.

- Organizational safety culture: 18 questions.

- Nationality, language, communication, and safety: 9 questions.

- Manning level and fatigue: 19 questions.

- Economy, efficiency, competition, and safety: 5 questions.

- Vessel characteristics, technology, and safety: 6 questions.

- Port calls and time pressure: 3 questions.

- Competence, nationality, and safety: 3 questions.

- National safety culture: 7 questions.

- Safety outcomes: 6 questions.

- Risk analyses and procedures: 4 questions.

3.2.4. Analysis of Quantitative Data

4. Results

4.1. Procedure Negligence

4.1.1. Survey Results

- Violation of procedures seldom has consequences (53% disagree, 24% neither/nor, 23% agree)

- The competition between shipping companies means that we sometimes have to violate safety procedures (77% disagree, 12% neither/nor, 11% agree)

- I never use written procedures in the work I perform on board (69% disagree, 17% neither/nor, 15% agree)

4.1.2. Interviewees’ Experience of Procedure Negligence

We take short cuts; we don’t have manning to get everything formally right. As we see it, we have done it a thousand times, and it has never been a problem.Captain, general cargo vessel

If a hydraulic hose snaps on the unloading crane while we lie working, we might need to change it in an unfavorable situation. Bad weather and darkness. We need to climb. It can’t be ideal conditions, and we will take a calculated risk. And it’s not always we can finish. We could take better measures. […] In a perfect situation you’d stop and sail to quay and rent a lift. […] You don’t do that.Mate, fodder vessel

If you’re to do a crane lift, you just do it, without thinking more about it. Ideally it should’ve been analyzed, but the conclusion’s that we did it the same way, because it’s only one way to do it.Captain, general cargo vessel

ISM isn’t just positive. Is it good safety culture? I don’t know. It’s often lack of time, plus the fact that you get sick of it. For instance, it says you’re to test the emergency radio every day. That’s something you just don’t bother.Mate, bulk vessel

4.2. Causes of Procedure Negligence

4.2.1. Survey Results

4.2.2. Interviewees’ Experience of Work Pressure

Sometimes you feel it. Maybe when you’re approaching the quay, “will this work or not”, but usually it works okay. You have to use your common sense, and know your limitations. You can lie at sea until the conditions are better. Even if someone stands at shore and waits, they just have to wait. But you do feel it. But in the end, you don’t care, even though you think about it afterwards.Captain, bulk vessel

You have chosen an occupation and it’s been like this since I started at sea. Since I started as a deck boy. Everyone had to chip in when we loaded, and we could relax when the ship was at sea. It’s a culture that … It’s not possible to change a culture that’s been there forever. When the load’s ready: “Oh, no, I have to sleep ten hours, I can’t work”, right. I will not make money and the company will not make money. Then I’d have to quit. I’d have to go home and stay on welfare, that’s next.Captain, bulk vessel

Particularly on timber runs, some ports are close to each other. You get two–three hours on the pillow before it’s up again. And we load for four-five hours and continue. Four–five hours to next port, and loading again. And maybe you have four ports like that after each other. Then you’ll be tired when you’re finished.Captain, bulk vessel

It’s awful, just prices. It’s nothing to ask about, just price and price and price. They don’t look at what’s in the dock, just as long as it floats it’s okay. [If there were more audits, something could change.] But it’s price. If they get someone to transport the cargo, they’d run with it. It’s just prices. That’s how all cargo transport is. Also, trucks—they’re also out in the cold.Captain, bulk vessel

4.2.3. Interviewees’ Experience of Impracticable Procedures

It’s pretty good now. HSE meetings … I don’t think any industry in the world focus more on safety. It’s almost like you can’t go to the loo without asking for replacement. The risk’s if it becomes too much. But it’s pretty good now.Mate, live fish carrier

The problem is that the ISM-system’s too big and extensive for the ordinary man to take the trouble to get to know it. So, it’s usually the ship management that knows what it’s about. This is an overstatement, because most [crewmembers] know the basics, but not more than that.Mate, bulk vessel

It’s normal to buy a system and start to use it immediately. That leads to frustration and theater acting. And people loose motivation. […] It’s not sure the company was so thorough. They buy a commodity, and it was made for an offshore vessel, and it’s us that get the requirements. That’s the tendency: that we get that requirement, and we don’t have a system and training that harmonizes.Mate, fodder vessel

4.2.4. Interviewees’ Diagnosis of Auditable Systems

It’s the Maritime Authority’s fault. They gave all of the ISM to the recognized companies. They love it! Every non-conformity gives income.Captain, general cargo vessel

It’s easy for the company to get no non-conformities, and follow what’s to be followed. So [the system] won’t be adjusted. Just buy the service and get it over with. […] You bring apples to school for the teacher to be satisfied, but you don’t get full yourself. It doesn’t help yourself.Mate, fodder vessel

What we did in our daily business was going to be documented. But it’s grown so crazy. The largest problem is the possibility for interpretations—it’s like reading the Bible. And there’s a new meaning every time a new auditor comes. […] If we’re to increase safety, we have to remove the possibility for companies to [financially] profit on safety. Like [consultants], that thrives on safety. That’s the problem with ISM. It’s become business, rather than a resource for safety.Captain, general cargo vessel

4.3. Survey Results on the Relationship between Procedure Negligence and Safety Outcomes

4.4. Suggestions on How to Close the Gap between Formal and Informal Safety Management

4.4.1. Reduction of Work Pressure

Then the government has to come in and regulate how it should be. And everyone would have to comply. Then everyone would be equal, right.Captain, dry cargo vessel

On one of the former vessels I drove a digger. It was stressful to sit there and hear the ropes start breaking, and then have to run from the digger to the bridge [to navigate the loose vessel into safety]. Now we all work inside, dry, and almost always with coffee in our mugs.Mate, fodder vessel

4.4.2. Improving Formal Procedures

4.4.3. Made by the Practitioners for the Right Activities

I swear that the ones in the field, the ones performing the job, are best fitted to assess the situation and the risk. They must be more involved, get more to say […].Mate, fodder vessel

An alternative is that the decision-makers should come out in the field, see how the job’s done in practice. Many onshore think that things are like this and that, and when they come out they see that it’s not like that at all.Mate, fodder vessel

4.4.4. Make Changes along the Way

When we get the system on board it’s often written for another vessel. It’s the same about the procedures. So, we get a job to do, to get the procedures to correspond with reality. […] Adjust the system to vessel, equipment and manning. So, the map and the terrain match. […] We do that onboard, we send feedback to the company and point out that this is nothing we can be acquainted with, because it isn’t correct.Mate, fodder vessel

4.4.5. Simplify

On my last vessel I made a safety manual, where I extracted what they need to follow on a daily basis—work procedures and risk considerations - a small binder that was supposed to be easy to get familiarized with. I don’t know if it worked, but at least it got more interest than the ugly large ISM binder.Mate, bulk vessel

It’s okay to have the ISM [safety management system] as a guide, but it’s also something about using your head and think rationally outside what’s written. It’s not always that what’s written is very rational.Captain, bulk vessel

4.4.6. In-House Competence Auditing

If you’re a small company and outsource your ISM. It doesn’t give our kind of follow-up. […] If they could be together, several companies, and hired someone to be responsible for it. You could get a consultant, from DNV or someone, but that won’t be follow-up, you’ll get a new guy everytime.Management, bulk vessel company

4.4.7. Lessons from an Aligned Safety Management System

5. Concluding Discussion

5.1. Factors Influencing Procedure Negligence

5.2. How to Reduce the Discrepancy between Formal and Informal Safety Management?

5.3. Methodological Weaknesses and Questions for Future Research

5.4. Finalizing Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Measures

Appendix A.1. Background Variables

Appendix A.2. Procedure Violations, Sleeping Rules, and Lacking Use of Procedures

- Violation of procedures seldom has consequences

- The competition between shipping companies means that we sometimes have to violate safety procedures

- I never use written procedures in the work I perform on board

Appendix A.3. Organizational Safety Culture

- The shipping company regards safety to be a very important part of all work activities

- The shipping company is aware of the most important safety problems that we have on board

- Ship management regards safety to be a very important part of all work activities

- Ship management is aware of the most important safety problems that we have on board

- Ship management stops unsafe operations and activities

- Ship management detects crew members who work unsafely

- Ship management often praises crew members who work safely

- My colleagues on board usually report all safety problems and unsafe situations that they experience in their work

- My colleagues on board do all they can to prevent accidents and unwanted incidents

- There are routines (procedures) on board for reporting safety problems

- All defects or hazards that are reported are corrected promptly

- After an accident has occurred, appropriate actions are usually taken to reduce the chance of reoccurrence

- Everyone has sufficient opportunity to make suggestions regarding safety

- All crew members on board receive adequate training to work in a safe way

- All newly employed are provided with sufficient training for their work activities

- Everyone on board is kept informed of any changes which may affect safety

- Safety on board is generally well controlled

- Safety on board this vessel is better than on other vessels

Appendix A.4. Working Conditions

- Please specify total manning on board the vessel

- Sometimes I feel pressured to continue working, even if it is not perfectly safe

- Number of port calls per week

- Your shift change is delayed because of work operations, for instance port calls?

- You work more than 16 h in the course of a 24 h period?

- You are interrupted when you are off duty?

Appendix A.5. Safety Outcomes

- Have you been injured in your work on board in the course of the last two years?

- Has the vessel been involved in a shipping accident (e.g., grounding, collision, contact injury, fire) in the two last years?

- To what extent do you worry about risk aboard?

- All in all, how do you assess the safety of your work place situation?

References

- Alderton, T.; Winchester, N. Globalisation and de-regulation in the maritime industry. Mar. Policy 2002, 26, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, M.; Jensen, H.J. Merchant seafaring: A changing and hazardous occupation. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nævestad, T.-O.; Phillips, R.O.; Elvebakk, B.; Bye, R.J.; Antonsen, S. Work-Related Accidents in Road Sea and Air Transport: Prevalence and Risk Factors; TØI Report 1428/2015; Transportøkonomisk Institutt: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA). European Statistics from the European Maritime Safety Agency; EMSA: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen, F.J.; Kuronen, J.; Tapaninen, U. Evaluation of the ISM Code in the Finnish shipping companies. J. Marit. Res. 2014, 9, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kongsvik, T.; Gjøsund, G. HSE culture in the petroleum industry: Lost in translation? Saf. Sci. 2016, 81, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek Å Runefors, M.; Borell, J. Relationships between safety culture aspects—A work process to enable interpretation. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M.J.W. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Safety Management Systems; No. AR-2011-148; Australian Transport Safety Bureau: Canberra, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Størkersen, K.V.; Bye, R.J.; Røyrvik, J.O.D. Sikkerhet i fraktefarten. Analyse av drifts- og arbeidsmessige forhold på fraktefartøy. In NTNU Samfunnsforskning AS; Studio Apertura: Trondheim, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsen, S. The relationship between culture and safety on offshore supply vessels. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nævestad, T.-O. Cultures, Crises and Campaigns: Examining the Role of Safety Culture in the Management of Hazards in a High Risk Industry. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nævestad, T.-O. Safety in Maritime Transport: Is Flag State Important in an International Sector? TØI-Rapport 1500/2016; Transportøkonomisk Institutt: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nævestad, T.-O. Occupational Safety and Work-Related Factors in Norwegian Maritime Transport; TØI Rapport 1501/2016; Transportøkonomisk Institutt: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nævestad, T.-O. Safety culture, working conditions and personal injuries in Norwegian maritime transport. Mar. Policy 2017, 84, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A. Editorial: Culture’s Confusions. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.J.; Flin, R. Safety Culture: Philopher’s Stone or a Man of Straw? Work Stress 1998, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. Safety climate: Conceptualization, measurement, and improvement. In Oxford Handbook of Organizational Climate and Culture; Oxford University Press: Oxford, GB, 2014; pp. 317–334. [Google Scholar]

- Guldenmund, F.W. The Nature of Safety Culture: A Review of Theory and Research. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 215–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidgeon, N.; O’Leary, M. Man-Made Disasters: Why technology and organisations (sometimes) fail. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, S.L.; Travaglione, A. Organizational Behaviour on the Pacific Rim; McGraw-Hill Higher Education: Sydney, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Snook, S.A. Friendly Fire: The Accidental Shootdown of U.S. Black Hawks over Northern Iraq; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. Human error: Models and management. Br. Med. J. 2000, 320, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostad, L.T. Håndtering av Målkonflikter I Bøyelast: ET Casestudie av Hvordan Rederi og Oljeselskap Tilrettelegger for at Sikkerhet kan Prioriteres av Ledende Offiserer Ombord PÅ Bøyelastere. Master’s Thesis, Senter for Teknologi, Innovasjon og Kultur, Universitetet i Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Perrow, C. Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. Managing the Risk of Organisational Accidents; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fourie, C.; Holmes, A.; Hildritch, C.; Bourgeois-Bougrine, S.; Jackson, P. Interviews with Operators, Regulators and Researchers with Experience of Implementing Fatigue Risk Management Systems; Road Safety Research Report; Department for Transport: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Almklov, P.G.; Rosness, R.; Størkersen, K.; Almklov, P.G.; Rosness, R.; Størkersen, K. When safety science meets the practitioners: Does safety science contribute to marginalization of practical knowledge? Saf. Sci. 2014, 67, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieder, C.; Bourrier, M. Trapping Safety into Rules: How Desirable or Avoidable Is Proceduralization? Ashgate: Farnnham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, S. The bureaucratization of safety. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeskog, B. The Legitimacy of Safety Management Systems in the Minds of Norwegian Seafarers. TransNav Int. J. Mar Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2015, 9, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, F. Paperwork at the service of safety? Workers’ reluctance against written procedures exemplified by the concept of ‘seamanship’. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Størkersen, K.V. Bureaucracy Overload Calling for Audit Implosion A Sociological Study of how the International Safety Management Code Affects Norwegian Coastal Transport. Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian University of Science, Trondheim, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2017, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.P.; Lane, T.; Bloor, M.; Allen, P.H.; Burke, A.; Ellis, N. Fatigue Offshore: Phase 2 The Short Sea and Coastal Shipping Industry; Seafarers International Research Centre/Centre for Occupational and Health Psychology, Cardiff University: Cardiff, Wales, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Starren, A.; van Hooff, M.; Houtman, I.; Buys, N.; Rost-Ernst, A.; Groenhuis, S.; Dawson, D. Preventing and Managing Fatigue in the Shipping Industry TNO-Report 031.10575; TNO: Hoofddorp, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- GAIN. ”Operator’s Safety Handbook”. 2001. Available online: https://flightsafety.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/OFSH_english.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Reason, J. Achieving a safe culture: Theory and practice. Work Stress 1998, 12, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edkins, G.D. The INDICATE safety program: Evaluation of a method to proactively improve airline safety performance. Saf. Sci. 1998, 30, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskau, T.; Longva, F. Torkel Bjørnskau, Frode Longva, Sikkerhetskultur i Transport; TØI Rapport 1012/2009 Oslo; Transportøkonomisk Institutt: Oslo, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nævestad, T.-O.; Bjørnskau, T. Kartlegging av Sikkerhetskultur i tre Godstransportbedrifter; TØI Rapport 1300/2014; Transportøkonomisk Institutt: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Age Group | Position | Experience | Vessel Type | Year the Vessel Was Built | Vessel Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Younger than 31 years | Captain | Less than one year | Bulk | Before 1980 | <500 DWT |

| 31% | 28% | 4% | 34% | 16% | 19% | |

| 2 | 31–40 | Deck officer | 1–3 years | General cargo | 1980–1985 | 500–3000 DWT |

| 17% | 24% | 9% | 14% | 8% | 79% | |

| 3 | 41–50 | Deck crew | 4–10 years | Tank vessel | 1986–1991 | >3000 DWT |

| 23% | 20% | 24% | 4% | 3% | 2% | |

| 4 | 51–60 | Chief engineer | 11–15 years | Live fish carrier | 1992–1997 | - |

| 23% | 7% | 7% | 34% | 16% | - | |

| 5 | Older than 60 years | Engine officer | More than 15 years | Stand by vessel | 1998–2003 | - |

| 6% | 1% | 56% | 2% | 14% | - | |

| 7 | - | Engine crew | - | Anchor handling vessel | 2004–2009 | - |

| - | 4% | - | 1% | 23% | - | |

| 8 | - | Catering | - | Fish farming vessel | 2010–2015 | - |

| - | 5% | - | 6% | 21% | - | |

| 9 | - | Apprentice | - | Other | Before 1980 | - |

| - | 9% | - | 5% | 14% | - | |

| 10 | - | Other | - | - | - | |

| - | 2 | - | - | - | ||

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Value | Age Group | Vessel Type | Position/Line of Work | Port Calls Per Week | Manning Level | Demanding Working Conditions | Work Pressure | Org. Safety Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Younger than 31 years | Bulk | Captain | 1–3 | 1–2 people | 3–4 points | Totally disagree | 18–69 |

| 6.4 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 6.6 | - | 4.8 | 4.9 | 8.8 | |

| 2 | 31–40 | General cargo | Deck personnel | 4–6 | 3–4 people | 5–6 points | Disagree somewhat | 70–75 |

| 7.3 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 7.6 | 6 | 5.9 | 8.1 | |

| 3 | 41–50 | Tank vessel | Engine personnel | 7–9 | 5–6 people | 7–8 points | Neither/nor | 76–80 |

| 6.3 | 6.3 | 6 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 8.7 | 6 | |

| 4 | 51–60 | Live fish carrier | Other | 10–12 | 7–8 people | 9–10 points | Agree Somewhat | 81–85 |

| 5.6 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 7 | 5.9 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 5.9 | |

| 5 | Older than 60 years | Other | - | 13–15 | 9–10 people | 11–12 points | Totally agree | 86–90 |

| 6.1 | 6.6 | - | 5.8 | - | 7.8 | 11.6 | 4.9 | |

| 6 | - | - | - | >15 | 11–12 people | 13–21 points | - | - |

| - | - | - | 6.7 | - | 10 | - | - | |

| p value | 0.202 | 0.698 | 0.846 | 0.053 | 0.208 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Variables | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 | Step 6 | Step 7 | Step 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | −0.140 * | −0.138 * | −0.131 * | −0.114 | −0.122 | −0.079 | −0.027 | 0.012 |

| Vessel type (Other = 1, Tank vessel = 2) | −0.033 | −0.038 | −0.063 | −0.081 | −0.077 | −0.086 | −0.113 * | |

| Position (Other = 1, Deck personnel = 2) | 0.045 | 0.052 | 0.055 | −0.007 | 0.081 | 0.059 | ||

| Port calls | 0.157 ** | 0.149 * | 0.088 | 0.066 | 0.026 | |||

| Manning level | −0.103 | −0.015 | 0.031 | 0.042 | ||||

| Org. safety culture | −0.454 *** | −0.310 *** | −0.126 * | |||||

| Demanding working conditions | 0.374 *** | 0.215 *** | ||||||

| Work pressure | 0.492 *** | |||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.023 | 0.027 | 0.215 | 0.321 | 0.468 |

| Safety Outcomes | Correlation |

|---|---|

| Personal injuries in the last two years | 0.220 *** |

| Ship accidents in the last two years | 0.095 |

| Worry about risk on board | 0.279 *** |

| Safety assessment of work place situation | −0.498 *** |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nævestad, T.-O.; Vedal Størkersen, K.; Phillips, R.O. Procedure Negligence in Coastal Cargo: What Can Be Done to Reduce the Gap between Formal and Informal Aspects of Safety? Safety 2018, 4, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety4030034

Nævestad T-O, Vedal Størkersen K, Phillips RO. Procedure Negligence in Coastal Cargo: What Can Be Done to Reduce the Gap between Formal and Informal Aspects of Safety? Safety. 2018; 4(3):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety4030034

Chicago/Turabian StyleNævestad, Tor-Olav, Kristine Vedal Størkersen, and Ross O. Phillips. 2018. "Procedure Negligence in Coastal Cargo: What Can Be Done to Reduce the Gap between Formal and Informal Aspects of Safety?" Safety 4, no. 3: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety4030034

APA StyleNævestad, T.-O., Vedal Størkersen, K., & Phillips, R. O. (2018). Procedure Negligence in Coastal Cargo: What Can Be Done to Reduce the Gap between Formal and Informal Aspects of Safety? Safety, 4(3), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety4030034