Identifying a Framework for Implementing Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Vision Zero Approach

- Political commitment to prioritize safety over mobility

- Speed management to reduce crash severity

- Vehicle design and safety technologies that protect all road users

- Shared responsibility between system designers and road users

1.2. Conditions for Implementing Vision Zero Approach

1.3. Road Safety Strategy Implementation Frameworks

1.4. Factors Influencing Implementation of the Vision Zero Approach

1.4.1. Quantified Targets and Strategic Planning

1.4.2. Governance and Institutional Capacity

1.4.3. Road Safety Measures

1.4.4. Data and Research

1.4.5. Monitoring and Evaluation

1.4.6. Cultural Factors

1.4.7. Contextual Relevance

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Trustworthiness

3. Results

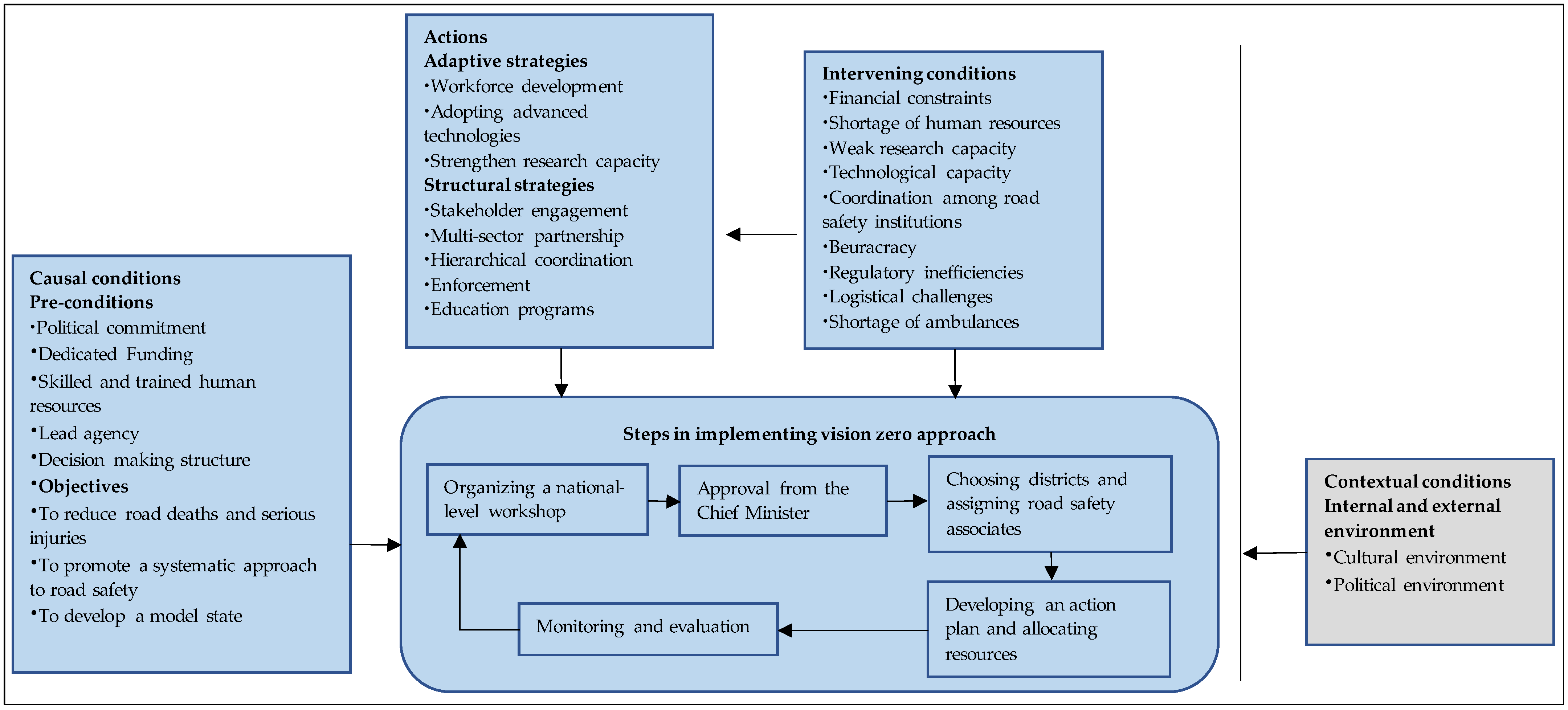

3.1. Vision Zero Implementation Processes in India

3.1.1. Core Category: Steps in Implementing Vision Zero Approach

3.1.2. Causal Conditions

3.1.3. Intervening Conditions

3.1.4. Actions or Interaction Strategies

“In the first year, we saw a 5% decline in road traffic fatalities in first 10 districts of implementation. The remaining 13 districts of Haryana where vision zero was not implemented saw a 5% increase in road traffic fatalities in the same year. Therefore, the vision zero project was expanded to all 23 districts of Haryana.” [IP11]

3.1.5. Contextual Conditions

3.2. Vision Zero Implementation Process Steps in Sweden

3.2.1. Core Category: Steps in Implementing Vision Zero Approach

3.2.2. Causal Conditions

3.2.3. Intervening Conditions

3.2.4. Actions or Interaction Strategies

3.2.5. Contextual Conditions

3.3. Comparative Analysis of the Implementation Processes in Sweden and India

3.3.1. Steps in Implementing Vision Zero Approach

- Develop the road safety agenda;

- Seek approval from the Parliament and other relevant authorities;

- Develop a flexible and phased action plan;

- Resource planning and allocation;

- Establish a monitoring and evaluation framework;

- Use monitoring data to inform continuous improvements.

3.3.2. Preconditions

- Mobilize political support;

- Develop a financial plan identifying sources and ensuring dedicated funding;

- Assess and strengthen the availability of highly qualified human resources;

- Constitute a lead agency with clear authority and coordination mandate;

- Establish a decision-making structure that balances consensus and urgency.

3.3.3. Objectives

- Adopt the vision zero initiative with the primary goal of reducing road deaths and serious injuries;

- Transition from traditional road safety methods to a systematic approach.

3.3.4. Intervening Conditions

- Diversify funding sources and develop a long-term financial sustainability plan;

- Ensure there is cost efficiency;

- Recruit highly qualified staff to support the implementation process;

- Provide structured training in both technical and non-technical competencies;

- Develop retention incentives.

- Assess existing technological infrastructure for enforcement and surveillance;

- Reduce reliance on manual enforcement by integrating automated systems.

- Strengthen research capacity to support evidence-based planning;

- Promote cross-sectoral collaboration in crash investigation and data sharing;

- Foster partnerships with academic institutions and industry to support innovation.

3.3.5. Actions or Interaction Strategies

- Integrate public education campaigns to shift road user behavior and build safety culture;

- Transition from manual enforcement to technology-supported systems;

- Prioritize infrastructure design that protects vulnerable road users and reduces crash zones.

- Pilot Vision Zero at subnational levels to test feasibility and generate localized insights.

- Establish multi-sector partnerships that include government, NGOs, academia and private-sector actors;

- Design a coordinating structure that enables vertical integration and role clarity;

- Constitute a lead agency.

- Use cost–benefit analysis to prioritize interventions and justify resource allocation;

- Partner with academic institutions to develop specialized road safety curricula.

3.3.6. Contextual Conditions

- Promote leadership modeling of safe behavior to build public trust;

- Challenge fatalistic narratives through community education and evidence-based messaging;

- Tailor public awareness campaigns to literacy levels and cultural beliefs;

- Address corruption in enforcement agencies through accountability mechanisms and oversight;

- Anticipate institutional resistance;

- Engage resistant professional groups through dialogue and capacity-building.

- Secure high-level political endorsement to launch and legitimize Vision Zero;

- Advocate through influential champions to build cross-sectoral political support;

- Institutionalize funding commitments to reduce dependence on political cycles;

- Monitor political engagement and adapt advocacy strategies to shifting priorities.

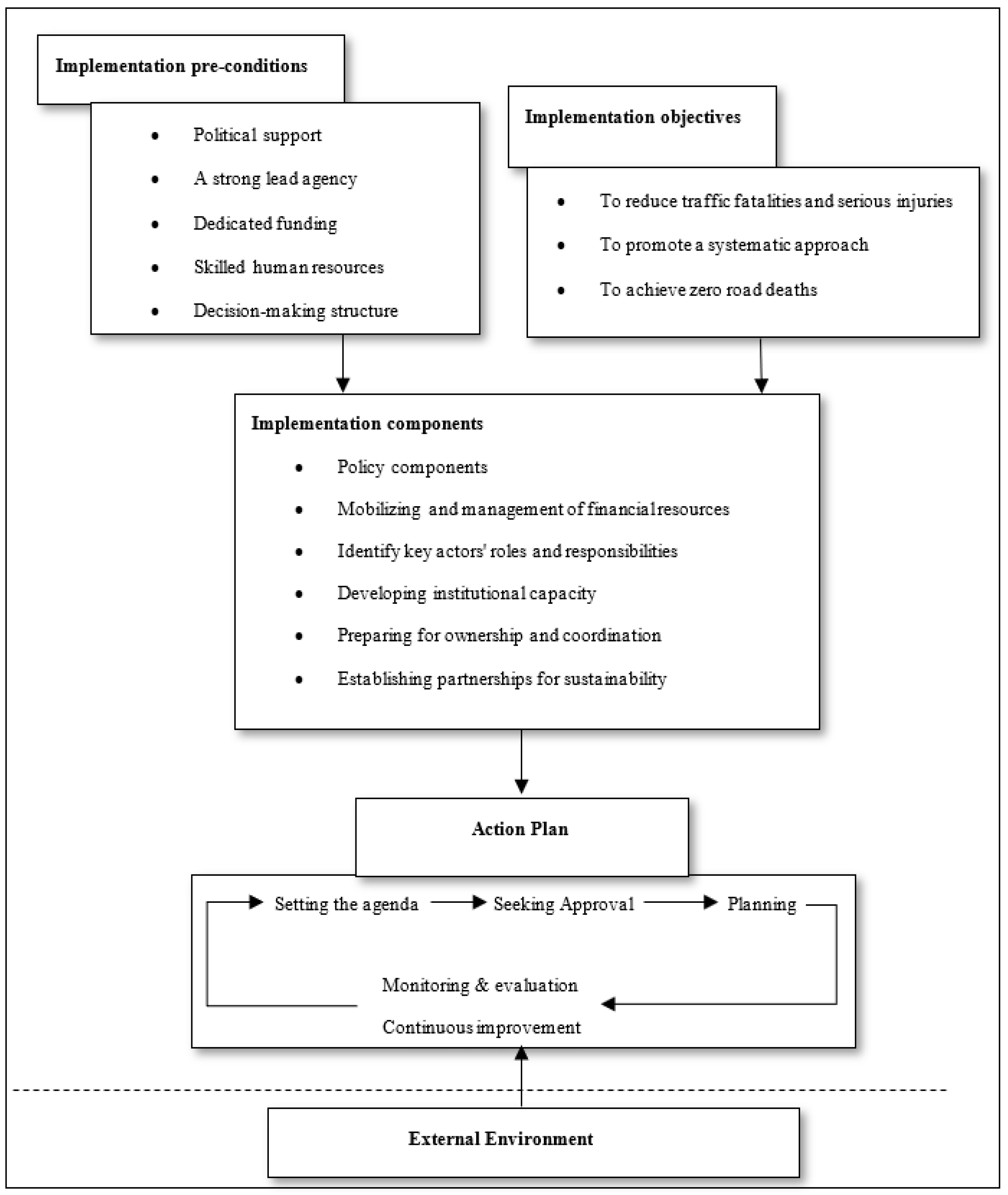

3.4. Framework for Implementing the Vision Zero Approach in LMICs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Vision Zero Implementation Processes | Sub-Components | Components Present in the Indian Context | Components Present in the Sweden Context | Proposals for LMICs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation pre-conditions | Political commitment | Political commitment is crucial, as it directly influences bureaucratic decision-making | Political support should be mobilized from the outset to ensure early buy-in and adoption | Mobilize political support early to ensure buy-in and accelerate adoption |

| × | Engagement should involve both national and local politicians to make the approach a priority at multiple governance | Ensure coordination across governance levels | ||

| Adequate financial resources | Availability of dedicated funding to ensure stability | Funding should be adequate to cover all costs | Establish dedicated funding streams within national budgets | |

| Financial plan identifying sources of funds and allocation | Funds must be allocated in a timely manner | Develop clear financial plans to ensure timely disbursement | ||

| × | Obstacles in quick funding disbursements should be removed | Simplify funding mechanisms to prevent delays | ||

| Skilled and trained human resources | Human resources should be skilled and trained in the core principles and components of vision zero. | Human resources should be highly qualified Personnel should be highly motivated and demonstrate a high level of commitment to road safety. Comprehensive training on the principles and key components of vision zero policy should be provided | Enhance technical expertise through training programs on vision zero principles Prioritize motivation and commitment | |

| Human resources should be sufficient to effectively implement vision zero | × | Ensure sufficient human resources | ||

| Lead agency | Crucial for leading vision zero implementation and coordinating all actions | Absolutely necessary to coordinate all implementation actions | Establish a lead agency to provide oversight and coordination | |

| × | Needs to be highly motivated and ambitious | Establish mechanisms for commitment | ||

| Clearly defined decision-making structure | Clearly defined structure so everyone knows their roles and responsibilities | Decision making needed to be quick, otherwise the purpose of saving lives would have been wasted. | Establish a decision-making structure to enhance efficiency and accountability | |

| Implementation objectives | To reduce road deaths and serious injuries | The primary objective was to reduce road deaths and serious injuries motivated by the rising number of fatalities and severe accidents | The primary objective was to reduce road deaths and serious injuries motivated by the rising number of fatalities and severe accidents | |

| To promote a systematic approach to road safety | Move away from a traditional user-focused approach to a systematic approach | Move away from a traditional user-focused approach to a systematic approach | Encourage a holistic approach that incorporates speed, roads, vehicles and users rather than focusing only on user behaviour | |

| Implementation process steps | National-level workshop | Engage stakeholders from multiple sectors at the national and local level to introduce vision zero | × | Leverage national-level workshops to build awareness and stakeholder commitment |

| Parliament approval | × | Prepare a proposal in consultation with the relevant government agencies Present the final proposal to parliament for approval | Seeking parliamentary approval to institutionalize vision zero policy and promote stability and continuity | |

| Approval from the Chief Minister | Presentations made to top bureaucrats and Transport minister on how vision zero could reduce road deaths | × | Engage high-ranking government officials through policy presentations to get political commitment | |

| Submit proposal to chief minister for approval | × | Establish approval processes within the executive leadership to strengthen policy legitimacy | ||

| Choosing districts and assigning road safety associates | Selecting 10 districts with the worst road safety record for intervention | × | Prioritize high-risk districts for intervention | |

| Recruiting, training and assigning road safety associates to their respective districts | Recruit and train road safety associates to improve localized efforts | |||

| Resource planning and allocation | × | Sourcing funds from the national and local government budget, private sector organizations, non-governmental organizations, and car manufacturers. | Diversifying funding sources (government funds, private sector, NGOs) | |

| Allocating funds to facilitate the recruitment of a highly qualified and motivated team of experts in road safety. | Prioritize recruitment of experts while considering cost-effective capacity-building programs | |||

| Developing an action plan and allocating resources | Developing state and district-specific program tailored to local priorities | An action plan was gradually developed by incorporating emerging insights | Design flexible plans that allow for adjustment based on real-time insights | |

| Mapping high-risk areas to strategically focus on the interventions | Mapping high-risk areas to strategically focus on the interventions | Prioritize high risk areas | ||

| The road safety associates gave recommendations and funds were allocated to implement improvements | Stakeholders proposed interventions and set individual goals | Engage multi-sector stakeholders in developing interventions | ||

| Continuous review process to ensure that the implementation evolved based on best practices and lessons learned | Establish a continuous improvement process | |||

| Monitoring and evaluation | Monthly and quarterly review meetings to track progress and follow on strategies | Monthly and quarterly review meetings to monitor progress and implementation measures | Adopt a periodic review framework to assess implementation effectiveness | |

| Implementation resources | Financial resources | |||

| availability of funds | Received funds from the national and state government, and the private sector. | Received funding from the national and local governments, the private sector, and NGOs | Diversify funding sources by engaging public and private entities to ensure financial sustainability | |

| cost efficiency | × | Cost-to-benefit analysis was done to optimize use of funds | Implement a cost-to-benefit analysis to ensure efficient allocation of funds | |

| unsustainable funding | Funds were subject to external conditions, for instance, the private-sector funds were withdrawn during the COVID-19 | Funding fluctuated based on government priorities | establishing a dedicated fund to ensure consistency. Diversify funding to mitigate financial uncertainty. Establish financial contingency plans | |

| Human resources | ||||

| Highly qualified staff | Struggled to find people qualified in road safety | Access to highly qualified, and motivated human resources | Enhance capacity-building initiatives through specialized road safety education programs Collaborate with universities and research institutions to create training programs | |

| Employee retention | Experienced high retention due to training, research opportunities and growth opportunities, and the competitive pay (Despite the high retention rate, the introduction of the integrated working concept led to staff attrition and a shift in focus from saving lives) | Struggled to retain staff due to a lack of perceived growth opportunities in the road safety | Promote road safety as a viable career with structured incentives and growth opportunities | |

| Implementation monitoring | Monitoring system (objectives, KPIs, targets, indicators, reporting) | × | Quantified targets for all vision zero components Strategies developed to achieve the specified targets KPIs established to measure impact | Develop a structured monitoring framework with clearly defined targets Develop quantified KPIs to track progress, assess effectiveness Ensure continuous evaluation to refine strategies based on performance data |

| Regular review meetings | Two monthly meetings with the head of state and district departments were held to track progress in the implementation of road safety projects | Monthly meetings were held to review performance and implementation progress Quarterly forums were organized by the national group for corporations to discuss progress, address problems, and share knowledge An annual conference was organized for all the key stakeholders to review performance by measuring and comparing key performance indicators from the previous year | Host regular review meetings with various stakeholders for continuous monitoring and to refine strategies based on performance data | |

| Dedicated team | × | Established a dedicated team of 10 to monitor and evaluate the implementation of the vision zero projects | Create dedicated teams responsible for overseeing monitoring and ensure continuous assessment and improvement of road safety initiatives | |

| Key actors’ responsibilities and ownership | Roles and responsibilities | Clear structure from the onset with the transport department leading in implementing the vision zero approach. | Initial confusion about whether the SRA or STA would take lead. Eventually, the role was assigned to STA | Establish clear leadership roles at the beginning to avoid confusion |

| Varied commitment levels | Strong support from the politicians. Approval from the chief minister encouraged all other state agencies to support vision zero | Strong political support with the minister of transport taking the lead in promoting vision zero Media coverage played a role in creating awareness about vision zero by writing articles | Mobilize political support to ensure vision zero adoption and sustained implementation Leverage media campaigns to enhance public awareness | |

| Opposition came from traditional road safety experts | Faced opposition from road engineers, cost–benefit analysis people and economists. | Establish a stakeholder engagement strategy to address any concerns and het buy-in | ||

| Coordination | Coordinating structure | Hierarchical coordinating structure led by the APEX committee. The committee had representatives from all six partners and was a decision-making body. The committee was followed by the Project Director who was the lead coordinator between knowledge partners and government departments | Networked environment where all stakeholders were involved. The lead agency coordinated activities between the stakeholder groups | Establish coordination structures suited to institutional capacity to ensure efficiency Establish a lead agency to oversee activities at the national level |

Appendix B

| Implementation Components | Implementation Proposals | Justification | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T.1. Assess implementation preconditions KPIs Political support The existence of a strong lead agency Highly qualified human resources Dedicated funding A decision-making structure | T.1.1 Determine the budget for financial resources required | Adequate and dedicated funding should be available to cover all costs and allocated in a timely manner. Funding sources include government funds, private-sector funds and NGOs. |

| T.1.2 Determine the existence of highly qualified human resources | Sufficient and highly qualified human resources are required to implement the vision zero approach. Training should be provided to give implementers full knowledge of the core principles of vision zero and its core components. | ||

| T.1.3 Mobilize political support | Political support is crucial in the implementation of the vision zero approach as it ensures that the road safety agenda is prioritized and that adequate funding is set aside to facilitate the implementation of road safety measures. | ||

| T.1.4 Constitute a lead agency | Establishing a strong lead agency is to coordinate actions between the key departments and organizations, take the lead in decision-making, and follow up on actions. | ||

| T.1.5 Establish if there is well-structured decision-making to support the process | A decision-making process should be developed to define roles and responsibilities clearly. Since the primary goal of the vision zero approach is to save lives, the structure should facilitate quick decision-making. | ||

| 2 | T.2 Formulate the implementation objectives KPIs Long-term vision Ambitious, measurable, and achievable road safety targets | T.2.1 To reduce road deaths and serious injuries | The vision zero initiative will be adopted with the primary aim of reducing road deaths and serious injuries. This will involve adopting a systematic approach. |

| T.2.2 To promote a systematic approach | Transition from traditional road safety methods to a systematic approach. This will involve strategies focusing on safer roads, safe road users, safe speed, safe vehicles and post-crash care. | ||

| 3 | National-level meetings Model project Advocacy plans (workshops and seminars) Action plans Adequate and trained human resources Adequate financial resources Progress review meetings Monitoring and evaluation framework | T.3.1 Develop the road safety agenda | In the initial phase of developing the road safety agenda, preliminary activities will be undertaken to discuss road safety issues and promote the vision zero approach. This includes national-level discussions: workshops, conferences, and forums to engage policymakers, government officials, NGOs, and other key stakeholders. Select a model state to pilot the vision zero approach, produce and apply knowledge that can be used to scale up the policy nationally. |

| T.3.2 Seek approval of the Parliament and other governing structures | Advocacy work is done to convince key stakeholders to adopt the vision zero approach and approval is sought from the relevant authorities. This may involve presenting proposals to policymakers, relevant government ministries, and key decision makers. | ||

| T.3.3 Resource planning and allocation | Financial resources are critical to the vision zero implementation process and may be sourced from the national and local government, private sector and non-governmental organisations. Highly qualified human resources are recruited, trained and assigned to their respective areas. Employee retention programs should also be supported to encourage the staff to grow within the profession. | ||

| T.3.5 Develop an action plan | Develop action plans and focus on mapping high-risk locations, consulting with stakeholders to identify innovative interventions and developing actions based on the vision zero principles and components. The implementation process and outcomes should be continuously reviewed so that the best practices and lessons learned are fed into the development of a formal action plan. | ||

| T.3.6 Monitoring and continuous improvement | Regular meetings should be held to review progress towards the achievement of the objectives. There should be a team dedicated to monitoring vision zero. | ||

| 4 | T.4 Policy components KPIs Public educational programs Road safety awareness activities (roadside events, posters, leaflets, etc.) Measures to enforce road safety rules and regulations Programs to redesign road infrastructure to include pathways designated to vulnerable users and calming measures Adequate speed cameras Vehicles fitted with safety features, e.g., intelligent speed assistance | T.4.1 Principles | Based the vision zero policy on the four guiding principles of safety first, a forgiving system, shared responsibility and coordinated action. |

| T.4.2 Core vision zero components | Policy components should incorporate five core components of vision zero such as safe roads, safe vehicles, safe speed, safe road users and post-crash response. | ||

| 5 | T.5 Management of resources targeted for implementation KPIs Dedicated funding Highly qualified and trained human resources | T.5.1 Mobilize for sufficient financial resources | The project must ensure that sufficient funds are available for the activities. There are several levels to mobilize funds including national and state government, the private sector and Non-Governmental Organizations. |

| T.5.2 Plan for sustainable funding | A contingency plan should be in place to mitigate expected and unforeseen challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic, and changes in government priorities. | ||

| T.5.3 Ensure there is cost efficiency | Cost-to-benefit analysis should be done to ensure funds are utilized efficiently. | ||

| T.5.4 Recruit highly qualified staff to support the implementation process | Vision zero project should be supported by highly qualified and motivated human resources. | ||

| T.5.5 Establish a system for employee retention | Provide training, research and growth opportunities, and the right pay to motivate and retain the staff. | ||

| 6 | T.6 Identify key actors’ roles and responsibilities KPIs Clearly defined roles and responsibilities Key actors’ analysis (support and opposition) | T.6.1 Identify and engage multi-sectoral actors. | Vision zero approach will involve actors from different sectors to leverage their unique expertise and resources. This includes government agencies, the private-sector, non-governmental organizations, academic and research institutions. Establish clear roles and responsibilities for each stakeholder group to enhance coordination and accountability. |

| T.6.2 Develop well-structured engagements between stakeholders | The involvement of stakeholders in the implementation of the vision zero approach should be well-structured to enhance commitment. Voices of reason should include a larger professional community including road engineers, cost-benefit analysis people and economists. | ||

| 7 | T.7 Develop institutional capacity KPIs Capacity-building activities Collaborations with academic and research institutions Good coordination among agencies Research studies Reliable database Adequate technology Adequate funding | T.7.1 Road safety education | Create and run public education and awareness programs in partnership with key stakeholders such as the police departments and other implementation partners. The programs will include roadside events in partnership with the police, annual road safety week, educational outreach in schools and colleges and media campaigns. |

| T.7.2 Organize training and capacity-building activities | To support the vision zero initiative, a capacity-building strategy will be undertaken, focusing on: identifying and addressing gaps in road safety skills and providing targeted training programs to develop these essential skills within the workforce. | ||

| T.7.3 Provide for research and development in road safety | Strengthening research capacity by collaborating with academic and research institutions to foster innovation and introduce best practices in road safety, conducting in-depth studies on road crashes to understand their causes and effects and developing a reliable database to support the making of evidence-based decisions and policy interventions. Collaborating with the car industry and technology providers to collect data from advanced vehicle technologies, such as event recorders, seatbelt reminders, and electronic stability control systems. Using this data to develop and implement better road safety interventions. | ||

| T.7.4 Promotion of vision zero implementation | Promote vision zero by engaging and involving political leaders, decision makers, NGOs and key stakeholders at both national and local levels. Appoint a dedicated leader, such as the minister of transport, to take a leading role in promoting vision zero. Launch national and regional public awareness campaigns to educate the public and stakeholders about vision zero. Use media platforms to ensure widespread dissemination of vision zero principles. | ||

| 8 | T.8 Preparing for ownership and coordination KPIs Appropriate coordinating structure (Hierarchical or networked) | T.8.1 Establish a coordination structure | Establish an effective coordination structure for the successful implementation of the vision zero approach. The following levels would be appropriate for a hierarchical coordination structure;

|

| T.8.2 Constitute a lead agency | Designate a lead agency to coordinate implementation activities between the core group and the stakeholders on the ground. The stakeholders will hold meetings regularly to review performance and discuss each stakeholder’s contribution toward the agreed-upon road safety indicators. | ||

| 9 | T.9 Planning for Monitoring and Evaluation KPIs Monitoring and evaluation framework Regular progress review meetings Published reports | T.9.1 Develop a monitoring and evaluation framework | Monitoring should be conducted to determine whether the implementation is as per the plan and to assess progress towards the achievement of the set objectives. It is therefore imperative to develop a monitoring and evaluation plan to aid through the process. |

| T.9.2 Hold regular review meetings with the implementing team | Hold monthly and quarterly meetings to review progress in the implementation of road safety projects. Organize annual conferences for all the key stakeholders to review performance by measuring and comparing key performance indicators from the previous year. | ||

| T.9.3 Procure a monitoring system with a layout of the objectives, KPIs, targets, indicators, reporting, and planning of the vision zero project | Establish a monitoring system to support data gathering and assess the implementation progress. The system will include clear, quantified targets for all vision zero components, key performance indicators to track progress and identify areas for improvement, regular reporting to review performance and a feedback mechanism to incorporate insights from the system into ongoing and future road safety strategies. | ||

| 10 | T.10 Establishing partnership and collaboration opportunities with stakeholders for sustainability | T.10.1 Develop a relationship with the national and local governments | Foster strong relationships with national and local government organs to ensure the vision zero approach is sustainable. |

| T.10.2 Develop a relationship with the private sector | Collaborate with the private sector, especially institutions involved in road safety. These will include car manufacturers and insurance companies. Their support will contribute to the adaptability of vision zero approach and thereby make it more sustainable. | ||

| T.10.3 Develop a relationship with the police department | Partner with the police to ensure effective enforcement of road safety rules such as wearing seat belts, using mobile phones, and controlling speeding. | ||

| T.10.4 Develop a relationship with the media | Partner with the media to ensure widespread awareness and support for vision zero. | ||

| T.10.5 Develop a relationship with Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) | Form strategic partnerships with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that provide advocacy, skills, and funding. | ||

| 11 | T.11 Assess and manage the external environment KPIs Audits of the cultural, political and legal environment | T.11.1 Assess the cultural environment | Conduct comprehensive assessments of the cultural environment to understand and manage the beliefs, values, and behaviors that impact road safety. |

| T.11.2 Assess the political environment | Conduct comprehensive assessments of the political environment to understand the dynamics, political interests and influences that impact road safety policies. | ||

| T.11.3 Assess the legal environment | Conduct comprehensive assessments of the legal environment to identify and manage existing laws, regulations and legal frameworks that impact road safety. |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Global Road Safety Facility. Annual Report 2024; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023: Country and Territory Profiles; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Haryana Transport Department. Haryana Road Safety Action Plan; Government of Haryana Transport Department: Haryana, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WRI-India. Haryana Vision Zero; WRI-India: Haryana, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/ITF. Road Safety Annual Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, K.M. Shifting Out of Neutral: A New Approach to Global Road Safety. Vand. J. Transnat’l L. 2005, 38, 743–770. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, G. Traffic Safety Dimensions and the Power Model to Describe the Effect of Speed on Safety. Ph.D. Dissertation, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koornstra, M.J. Prediction of traffic fatalities and prospects for mobility becoming sustainable-safe. Sadhana 2007, 32, 365–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R. Vision zero–Implementing a policy for traffic safety. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukrallah, R. Road Safety in Five Leading Countries; ACT Department of Territory and Municipal Services: Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Muennig, P.; Rosen, Z. Vision zero: A toolkit for road safety in the modern era. Inj. Epidemiol. 2017, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belin, M.; Tillgren, P.; Vedung, E. Vision zero–a road safety policy innovation. Int. J. Inj. Control Safe. Promot. 2012, 19, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lie, A.; Strandroth, J.; Krafft, M. Government Status Report, Sweden 2017; Swedish Transport Administration: Borlänge, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, A.; Wybourn, C.; Mendoza, M.; Cruz, M.; Juillard, C.; Dicker, R. The Worldwide Approach to vision zero: Implementing Road Safety Strategies to Eliminate Traffic-Related Fatalities. Curr. Trauma Rep. 2017, 3, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRI. Sustainable & Safe: A Vision and Guidance for Zero Road Deaths; WRI.org: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/ITF. Road Safety Annual Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Peden, M.M.; World Health Organization. World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- May, P.J. Policy Design and Implementation. In Handbook of Public Administration; Peters, B.G., Pierre, J., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2003; pp. 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Varhelyi, A. Road Safety Management—The Need for a Systematic Approach. Open Transp. J. 2016, 10, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlrad, N.; Gitelman, V.I.B. Road Safety Management Investigation Model and Questionnaire; Deliverable 1.2 of the EC FP7 project DaCoTA; IFSTTAR: Champs-sur-Marne, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Safety on Roads: What’s the Vision; OECD: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Elvik, R. Quantified road safety targets: A useful tool for policymaking? Accid. Anal. Prev. 1993, 25, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.C.; Sze, N.N.; Yip, H.F. Association between Setting Quantified Road Safety Targets and Road Fatality Reduction. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2006, 38, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvik, R.; Høye, A.; Vaa, T.; Sørensen, M. The Handbook of Road Safety Measures, 2nd ed.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Elvik, R. Does the Use of Formal Tools for Road Safety Management Improve Safety Performance? Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 2318, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, E.; Yannis, G.; Muhlrad, N.; Gitelman, V.; Butler, I.; Dupont, E. (Eds.) Analysis of Road Safety Management in the European Countries; Deliverable 1.5 Vol. II of the EC FP7 Project DaCoTA; National Technical University of Athens: Athens, Greece, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, I. Beyond ‘best practice’ road safety thinking and systems management–a case for culture change research. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannis, G.; Vasiljevic, J.; Milotti, A. Significance of the ROSEE Project–Road Safety in South East European Regions. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Road Safety in the Local Community, Valjevo, Serbia, 18–20 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khorasani-Zavreh, D.; Mohammadi, R.; Khankeh, H.; Laflamme, L.; Bikmoradi, A.; Haglund, B. The requirements and challenges in preventing of road traffic injury in Iran: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Federative Republic of Brazil: National Road Safety Capacity Review; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heydari, S.; Hickford, A.; Mcllroy, R.; Turner, J.; Bachani, A. Road Safety in Low-Income Countries: State of Knowledge and Future Directions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ODI/WRI. The Political Economy of Road Safety; ODI: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ODI/WRI. Securing Safe Roads; ODI: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hyder, A.; Vecino-Ortiz, A. BRICS: Opportunities to improve road safety. Bull. World Health Organ. 2014, 92, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wundersitz, L.; Baldock, M.R.J.; Raftery, S.J. The relative contribution of system failures and extreme behaviour in South Australian crashes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 73, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetali, S.; Josyula, L.; Gupta, S. Qualitative study to explore stakeholder perceptions related to road safety in Hyderabad, India. Injury 2013, 44, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, I.K.; Rahman, M. Predicting entry speed of traffic-calmed roads: Regression versus artificial neural network approach. Adv. Transp. Stud. 2023, 59, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Haghani, M.; Behnood, A.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. Road safety research in the context of low-and middle-income countries: Macro-scale literature analyses, trends, knowledge gaps and challenges. Saf. Sci. 2022, 146, 105–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Nunez, R.; Híjar, M.; Alfredo, C.; Hidalgo-Solórzano, E. Road traffic injuries in Mexico: Evidences to strengthen the Mexican road safety strategy. Rep. Public Health. 2014, 30, 911–925. [Google Scholar]

- Hamim, O.F.; Ukkusuri, S.V. Towards safer streets: A framework for unveiling pedestrians’ perceived road safety using street view imagery. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2023, 195, 107400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momin, K.A.; Hamim, O.F.; Hoque, M.S.; McIlroy, R.C. Integrating design and system approaches for analyzing road traffic collisions in low-income settings. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 194, 107965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghetti, F.; Marchionni, G.; De Bianchi, M.; Barabino, B.; Bonera, M.; Caballini, C. A new methodology for accidents analysis: The case of the State Road 36 in Italy. Int. J. Transp. Dev. Integr. 2021, 5, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojarro, F.; Solorzano, E.; Monreal, M. Challenges that hinder the application of the road safety regulation: A local law enforcement (LLE) officer’s perspective in Mexico. Inj. Prev. 2018, 24 (Suppl. S2), A65.2-A65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.; Poulos, R.; Rissel, C.; Hatfield, J. Exploring the Application of the Safe System Approach to a Set of Self-Reported Cycling Crashes. In Proceedings of the Australasian College of Road Safety Conference, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 9–10 August 2012. Exploring the Safe System approach to cycling (ACRS). [Google Scholar]

- McIlroy, R.C.; Plant, K.A.; Jikyong, U.; Nam, V.H.; Bunyasi, B.; Kokwaro, G.O.; Wu, J.; Hoque, M.S.; Preston, J.M.; Stanton, N.A. Vulnerable Road users in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: Validation of a Pedestrian Behaviour Questionnaire. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 131, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitelman, V.; Doveh, E. Investigating road safety management systems in the European countries: Patterns and particularities. J. Transp. Technol. 2016, 6, 378–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Yin, R.K., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar, S.; Shukla, P.R. Low carbon scenarios for transport in India: Co-benefits analysis. Energy Policy 2015, 81, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, T.K. National Road Safety Plan; Bureau of Police Research and Development: New Delhi, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Nora, J.E.; Bose, D.; Srinivasan, K.; Woodrooffe, J.H.F.; Surie, N.; Bliss, A.G. Delivering Road Safety in India: Leadership Priorities and Initiatives to 2030; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Corbin, J., Strauss, A., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 45–75. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.; Lincoln, Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 134–156. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore, R.F. Backward mapping: Implementation research and policy decisions. Polit. Sci. Q. 1979, 94, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walt, J.; Gilson, L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: The central role of policy analysis. HPP 1994, 9, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEG/World Bank. Making Roads Safer: Learning from the World Bank’s Experience; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, J.; Howard, E.; Bliss, T. An Independent Review of Road Safety in Sweden; Swedish Road Administration: Sweden, Borlänge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Augeri, M.G.; Colombrita, R.; Lo Certo, A.; Greco, S.; Matarazzo, B. Multi-criteria analysis to evaluate road safety measures and allocate available budget. In Proceedings of the SIIV 2005 International Conference, Bari, Italy, 22–23 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Safarpour, H.; Khorasani-Zavareh, D.; Soori, H.; Ghomian, Z.; Bagheri-Lankarani, K.; Mohammadi, R. The Challenges of vision zero Implementation in Iran: A Qualitative Study. Front. Future Transp. 2022, 3, 884930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Role and Organization | The Rationale for Participant Selection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IP1 | Independent researcher and academic | Professor at the Chalmers University of Technology and a Senior Consultant at ÅF Consult. | One of the main architects of vision zero and Former Director of road safety at the Swedish National Road Administration. Introduced vision zero in Sweden and was involved in the development of vision zero since the beginning. |

| IP2 | Government official | Senior Policy Advisor at Swedish Transport Administration (Trafikverket) | Safe system expert. He has seen vision zero established and flourished in Sweden since the beginning. Experience of 26 years with vision zero. Also, responsible for the development of vision zero academy. |

| IP3 | Government official and academic | Senior Advisor at Swedish Transport Administration (Trafikverket) | Safe system expert. Written numerous research reports and articles on vision zero. Involved in the development of vision zero since the beginning. |

| IP4 | Government official and academic | Associate Professor and Director of Sustainability and Traffic Safety at the Swedish Transport Administration (Trafikverket) | Involved with the development of vision zero since day one. Written numerous research reports and articles on vision zero. |

| IP5 | Independent researcher | Associate Professor at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden | An active researcher in the safe system approach in Sweden |

| IP6 | Academic and independent researcher | Professor at the Chalmers University of Technology | A researcher in the safe system approach. Written numerous research reports and articles on the vision zero approach. |

| IP7 | Government official | Senior Policy Advisor at Swedish Transport Administration (Trafikverket) | Safe system expert. Over 20 years of experience with vision zero policy. |

| Category | Role and Organization | The Rationale for Participant Selection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IP8 | Independent researcher | Director Integrated Urban Transport—WRI India | Overall responsibility of road safety section of WRI—India. Organised training for Road safety associates of Haryana vision zero. Involved in all meetings of Haryana vision zero. Written articles about Haryana vision zero. |

| IP9 | Independent researcher | Manager Sustainable cities—WRI India | Currently working on the Indian state of Haryana—vision zero program |

| IP10 | Independent researcher | Project Associate—WRI India | Currently working on Road safety projects in India |

| IP11 | Independent researcher | Manager Road Safety—WRI India | Working on Road safety |

| IP12 | Independent researcher—Global | Deputy Director WRI Global | Road safety expert and written articles and published reports on vision zero. Works on global strategy for addressing road safety issues (May have potential contacts in India) |

| IP13 | Academic and independent researcher | Professor at the Indian Institute of Technology | Expert in the safe system approach. Over 18 years of experience working closely with state governments to support road safety policies |

| IP14 | Academic and independent researcher | Professor at the Indian Institute of Technology | Safe system expert. Experience in capacity building on road safety. |

| IP15 | Government official | Senior Policy Advisor | Involved in the development of Haryana Vision Zero. Written numerous research reports and articles on vision zero. |

| IP16 | Government official | Senior Policy Advisor | Safe system expert. Written research articles and reports on the vision zero approach. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bajwa, M.U.; Saleh, W.; Fountas, G. Identifying a Framework for Implementing Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Perspective. Safety 2025, 11, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040093

Bajwa MU, Saleh W, Fountas G. Identifying a Framework for Implementing Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Perspective. Safety. 2025; 11(4):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleBajwa, Mahfooz Ulhaq, Wafaa Saleh, and Grigorios Fountas. 2025. "Identifying a Framework for Implementing Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Perspective" Safety 11, no. 4: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040093

APA StyleBajwa, M. U., Saleh, W., & Fountas, G. (2025). Identifying a Framework for Implementing Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Perspective. Safety, 11(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040093