1. Introduction

The increased incidence of fatal and nonfatal occupational injuries worldwide has forced governments to devise occupational safety and health (OSH) legislation that requires the management of workplace hazards to reduce their risks to acceptable levels. These regulations lead most firms to develop OSH management systems with programs for hazard identification, evaluation, and control. These systems also help firms to define OSH performance indicators. Many factors affect the success of such OSH management systems, but the presence of qualified safety professionals is significant, since they play a crucial role in an organization’s safety culture and the lowering of injury and death rates [

1,

2,

3].

Many professionals from various backgrounds work in the field of occupational safety and health. However, only individuals whose job is primarily focused on safety are classified as safety professionals [

4]. An OSH professional is usually a university-educated employee in a managerial/professional role that influences, engages, and coaches all levels of the organization, including senior management. An OSH practitioner, on the other hand, is a professionally qualified individual who implements strategy, particularly at the site level, with a focus on cutting-edge compliance.

Numerous studies have addressed the duties of safety experts as well as the information and skills they must possess [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Their findings might be included in the creation of national and international safety professional duties and responsibility standards. The main functions of the safety professional are to (1) anticipate, recognize, and assess hazardous circumstances and activities; (2) create hazard control plans, techniques, processes, and programs; (3) implement, administer, and advise others on hazard management measures and programs; and (4) measure, audit, and assess the efficacy of hazard controls and programs [

9]. The safety professional must carry out a number of duties within each of these primary responsibilities.

The right safety professionals must be chosen if a business wants to increase its safety performance [

10]. This necessitates identifying the duties and necessary competences of each function, as well as determining the demands of safety positions. The job description often lists these criteria. Therefore, precisely designing and creating the job description is the first step in recruiting the right safety specialist.

A job description is a written document that lists the tasks, obligations, contributions, conduct, results, and qualifications needed for a particular position within an organization [

11,

12]. It is the result of a thorough job analysis. Job descriptions are essential in the recruitment and selection process. They outline the knowledge and skills needed for the job, as well as the physical and personal prerequisites. As a result, the employer can choose the best candidate, as the job applicant is aware of the appropriate personal qualifications [

13]. Organizations also use job descriptions for training and development, legal matters, performance reviews, and human resource planning. Furthermore, job descriptions may serve as a helpful resource for learning about the professional competencies that employers value. By understanding these abilities, educational institutions may create a curriculum that satisfies industrial demands.

Because of the vital role of job descriptions in performance improvement, several studies on their development were found in the literature, such as those relating to lifestyle medicine case manager nurses [

14], public health officials [

15], librarians [

16], general surgery coordinators [

17], safety professionals [

5], and project managers [

18].

Ineffective safety professionals may be hired if the job descriptions are not appropriately designed. This will have a significant impact on the OSH management system and lead to decreased performance. In light of this, an organization’s OSH performance may be passively led by the job descriptions of its safety jobs. A passive leading indicator reflects the likely safety performance of an organization [

18]. Several studies can be found in the literature regarding the leading OSH indicators of safety performance [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Nevertheless, none found that the job description of the safety professional was an indicator. The lack of research on the connection between job description quality and an organization’s safety performance may contribute to poor safety culture. Only one study in the literature has examined this link, in which it was discovered that three companies’ job descriptions enhanced safety, quality, and productivity [

23]. Aside from gaps in the literature, there are grounds to conclude that OSH performance might be affected by the job descriptions of safety positions. A job description with unclear requirements may result in inefficient candidate selection. Furthermore, the job holder’s performance will be ineffectively assessed and evaluated if the duties and objectives of the position are unclear. Additionally, role uncertainty arising from a poorly designed job description may contribute to work dissatisfaction and, consequently, lower performance.

Thus, in safety research, it is critical to view safety position job descriptions as a measure of an organization’s OSH performance. This entails examining current writing practices and suggesting qualitative and quantitative techniques that can facilitate the quality assessment of job descriptions. None of the previous studies examined job descriptions related to safety in several sectors. Therefore, the research questions and hypotheses of the current study are:

Do organizations properly design the job descriptions of safety positions? Based on research on the job descriptions in numerous other fields, it is hypothesized that many of the current job descriptions of safety positions do not follow the standard formats recommended by human resources or professional safety agencies. For instance, observation of pilot sample job descriptions revealed the absence of one or more sections or essential information, such as an inadequate description of the roles and responsibilities.

Which specific elements within safety professional job descriptions are considered most important for achieving optimal safety outcomes? It is hypothesized that safety professionals do not consider all sections or elements as equally important. Judging the quality of job descriptions may be affected by the unequal importance of the elements and attributes.

Which sectors exhibit the most comprehensive and well-aligned safety professional job descriptions? The authors believe that the proper design of these job descriptions is a leading safety performance indicator. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that high-quality job descriptions are associated with good safety performance.

What actionable recommendations can be provided to organizations in different sectors for optimizing their safety professionals’ job descriptions?

To answer these questions, it is crucial to develop a hybrid qualitative and quantitative approach to evaluate the quality of job descriptions for better analysis and decision-making. Thus, the main objective is to introduce a novel methodology for assessing the quality of safety position job descriptions using a combination of qualitative, i.e., content analysis, and quantitative methods, i.e., AHP-TOPSIS with IPA. The content analysis approach is applied to evaluate job descriptions against predefined criteria, enabling a subjective assessment. On the quantitative side, the methodology employs a hybrid multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) framework to analyze the relative weights of job description elements and attributes, determine an overall job description quality index, and analyze the relationships between job description quality, safety performance, and other relevant factors. Moreover, the hybrid MCDM model is integrated with the IPA tool to determine the major strengths and weaknesses in job descriptions for multiple sectors.

The remainder of this manuscript is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents a recent literature review of the applications of the content analysis technique and the AHP, TOPSIS, and IPA techniques.

Section 3 presents a detailed description of the qualitative and quantitative techniques used for the evaluation of job descriptions.

Section 4 presents the application of the proposed approach to a sample of job descriptions of safety positions collected from various sectors.

Section 5 concludes the study with recommendations for future research.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Proposed Approach

The proposed approach for evaluating the quality of job descriptions of OSH professions consists of the following steps, as described below.

- (1)

Identifying the criteria and sub-criteria upon which the job descriptions are evaluated. This is carried out using a Delphi methodology by a panel of experts from industry and academia who have experience in OSH and human resources. Another function of this expert panel is to reach a consensus about the pairwise comparisons among the criteria and sub-criteria of the job description evaluation.

- (2)

Performing a content analysis of the job descriptions according to the criteria selected by the expert panel to facilitate the assessment of each criterion or sub-criterion.

- (3)

Evaluating the major strengths and weaknesses of the job description in multiple sectors. This detailed analysis will help define targeted strategies for each sub-criterion in job descriptions.

3.2. Data Collection

Before sampling, it was necessary to consider the criteria to be fulfilled in the sampled job descriptions. The first criterion was the source of the sampled job descriptions. Previous research involving sampling job descriptions relied mainly on job advertisements, as described by Kim et al. [

39]. However, following the same method in the current study did not result in a sample suitable for analysis, as most of the advertisements were written in a very brief form and, consequently, much information was missing. Therefore, it was decided to collect the job descriptions sample from more reliable sources; namely, by contacting the companies’ human resources or safety departments, accessing the companies’ official websites, contacting current safety job holders, and contacting reliable recruitment agencies, as described by Teare et al. [

50]. Moreover, the job descriptions were collected from sectors such as oil, gas, petrochemicals, utilities, manufacturing, construction, and various services companies [

51,

52]. Using Cochran’s formula for sample size calculation of an infinite population [

53], the target sample size was 94 (95% confidence level and 10% error). However, among the collected job descriptions, 91 were eligible for analysis, covering various safety-related jobs. The small difference between the sample analyzed and the targeted sample had a very slight effect on the error and/or the confidence level.

Table 1 illustrates the distribution of the sample with respect to the industrial sector.

3.3. Job Description Content Analysis

Despite the absence of a regulated form of job description, some components are commonly included. In this study, the main components (or elements or main criteria) and the attributes (sub-elements or sub-criteria) were adapted from Smith [

54] and Jerabek [

55]. The details and definitions of these contents are presented in

Table 2. Content analysis was used to evaluate the attributes of each component of the collected job descriptions in light of the definitions and descriptions of the attributes as detailed in

Table 2. Each definition was associated with related keywords or expressions. The attribute was then evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale based on the existence or absence of the keywords.

3.4. Expert Judgments

A necessary step for AHP-TOPSIS calculation is to determine the relative weights of the main and sub-criteria of the handled problem. In this study, the weights of the job description elements and their attributes were determined according to the judgment of experts with experience in the OSH field. A pairwise comparison form based on Saaty was prepared and sent to 12 experts to determine the relative weights [

56]. Each number on the scale is defined in

Table 3. The judgments were subsequently averaged, and the averages were rounded to the nearest integers.

The attributes (sub-criteria) were evaluated for each job description using a 5-point Likert scale system, as described in

Table 4.

3.5. Evaluating Job Descriptions Using the AHP-TOPSIS Approach

In the current study, a hybrid AHP-TOPSIS approach was applied to evaluate the job descriptions of safety professionals in the Saudi industry. Since the job description should contain the main components and each component has attributes, the evaluation was considered to be an MCDM problem. The AHP method was used to find the weights of the job description attributes using a pairwise comparison method, since the numbers of main criteria and attributes of each criterion were limited (i.e., fewer than 7). On the other hand, since the number of alternatives (sampled job descriptions) was large, the TOPSIS method was used to calculate the closeness coefficients that could be used as indicators of the job description quality.

3.6. Determining the Weights by AHP

The AHP method was applied twice to calculate both the relative weights of the main criteria (job description elements) and those of the sub-criteria (job description attributes). In both cases, the sequence of calculations included the following steps:

Step 1: Construct the structural hierarchy.

Step 2: Construct the pairwise comparison matrix.

Assuming

n attributes, the pairwise comparison of attribute

i with attribute

j yields a square matrix

AnXn, where

aij denotes the comparative importance of attribute

i with respect to attribute

j. In the matrix,

aij = 1 when

i =

j and

aji = 1/

aij.

Step 3: Construct a normalized decision matrix.

i, and

j =

1,

2,

3, …,

n.

Step 4: Construct the weighted, normalized decision matrix.

Step 5: Calculate an eigenvector and row matrix.

Step 6: Calculate the maximum eigenvalue, λ

max.

Step 7: Calculate the consistency index and consistency ratio.

where

n and

RI denote the order of the matrix and randomly generated consistency index, respectively. The value

RI depends on

n, as proposed by Saaty [

54], and it is shown in

Table 5.

3.7. Evaluation of Job Descriptions Using TOPSIS

TOPSIS attempts to determine the optimum alternative that simultaneously has the smallest distance from the positive ideal solution and the farthest distance from the negative ideal solution. This is performed by calculating the relative closeness coefficient that is between 0 (the worst alternative) and 1.0 (the best alternative). This way, the closeness coefficient can be employed as a measure of the quality of a job description element or main component, as well as the overall quality of the job description. The TOPSIS procedures implemented are as follows:

Step 1: Construct a normalized decision matrix.

j = 1, 2, 3, …,

J;

i = 1, 2, 3, …,

nStep 2: Construct the weighted normalized decision matrix by multiplying the weights

wi of the evaluation criteria with the normalized decision matrix

rij.

j = 1, 2, 3, …,

J;

i =1, 2, 3,…,

nStep 3: Determine the positive ideal solution (PIS) and negative ideal solution (NIS).

where,

where

.

Step 4: Calculate the separation measures of each alternative from PIS and NIS.

Step 5: Calculate the relative closeness coefficient to the ideal solution of each alternative.

i = 1, 2, 3, …, J

Step 6: Based on the decreasing values of the closeness coefficient, alternatives are ranked from most valuable to least valuable. The alternative having the highest closeness coefficient (CCi) is selected as the best job description

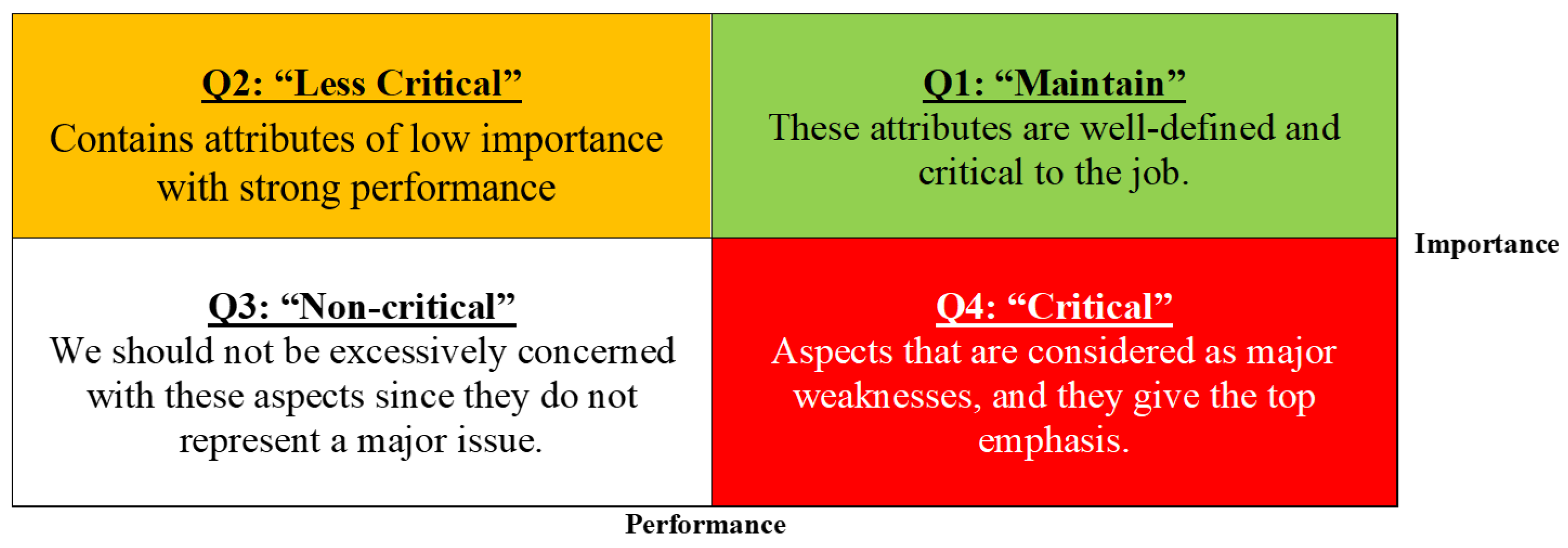

3.8. Importance–Performance Analysis

The IPA approach maps individuals’ judgments of performance and the importance of a certain component onto a two-dimensional chart, making the data easier to analyze [

57]. The chart classifies the attributes into four quadrants, as depicted in

Figure 1. Each quadrant represents a unique technique for supporting managers in understanding both the shortcomings and the essential actions for improvement. The

x-axis defines the “importance” of the aspects, which is defined as the weights obtained from the AHP method. The

y-axis represents the “performance” of the aspects, which is defined as the evaluation of the experts obtained from the TOPSIS method [

58].

3.9. Statistical Analysis

This study investigates the quality of job descriptions of safety jobs. Therefore, one-way ANOVA was used to investigate the influence of the industrial sector on the quality of job descriptions, followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis to assess the significant differences between the groups. This was accomplished by testing whether the means of job description qualities (represented by the closeness coefficients) significantly differ from one category to another within each of the studied factors. In all cases, a confidence level of 95% and a p-value of 0.05 were used in the analysis, accordingly, to test the significance of the results.

5. Discussion

Poorly designed job descriptions might lead to the wrong people being chosen for safety positions. Furthermore, the job holder’s performance will be ineffectively evaluated if the duties and objectives of the position are unclear. Additionally, role uncertainty arising from a badly drafted job description may contribute to work discontent and, consequently, lower performance. None of the previous studies evaluated in detail the job descriptions related to safety in several sectors. Therefore, this research aimed to integrate the AHP-TOPSIS-IPA techniques in assessing job descriptions in several fields. First, the AHP technique was applied to rate the weight of each sub-criterion in the job descriptions in the safety field. Then, using the TOPSIS technique, these weights combined with the evaluation scores from the content analysis were used to evaluate job descriptions in several sectors to generate an index representing the section-wise and overall quality of job descriptions of the safety positions. Moreover, the AHP-TOPSIS analysis was integrated with the IPA tool in order to dissect in detail the strengths and weaknesses of these job descriptions to form targeted strategies for improvement.

Before discussing the AHP-TOPSIS-IPA model, it is worth mentioning that the collected job descriptions were first evaluated using content analysis, as mentioned in a previous section. Content analysis was found to be a powerful tool in the primary qualitative evaluation of the job descriptions before converting the evaluations into a 1–5 score. An important feature of content analysis is its flexibility regarding the problem considered, the aim of the study, the quality of the data, and the researchers’ experience and knowledge [

59]. Accordingly, many successful applications of content analysis to job description evaluations exist [

52,

60,

61,

62,

63].

5.1. AHP-TOPSIS Evaluation

Duties and responsibilities (Criterion C) had the most valuable weight among all job description sections, followed by the qualifications section (Criterion D). This is in agreement with previous research on job role uncertainty. When this section of the job description is poorly designed, it creates role ambiguity and role conflict, resulting in stress and anxiety [

64], a lack of organizational commitment, job dissatisfaction, burnout, increased intent to leave [

65], and low performance [

66]. Additionally, job qualifications such as education, professionalism, and experience were found to affect job performance [

67]. Therefore, it can be concluded that poorly designed safety position roles and qualifications could have a negative impact on safety performance.

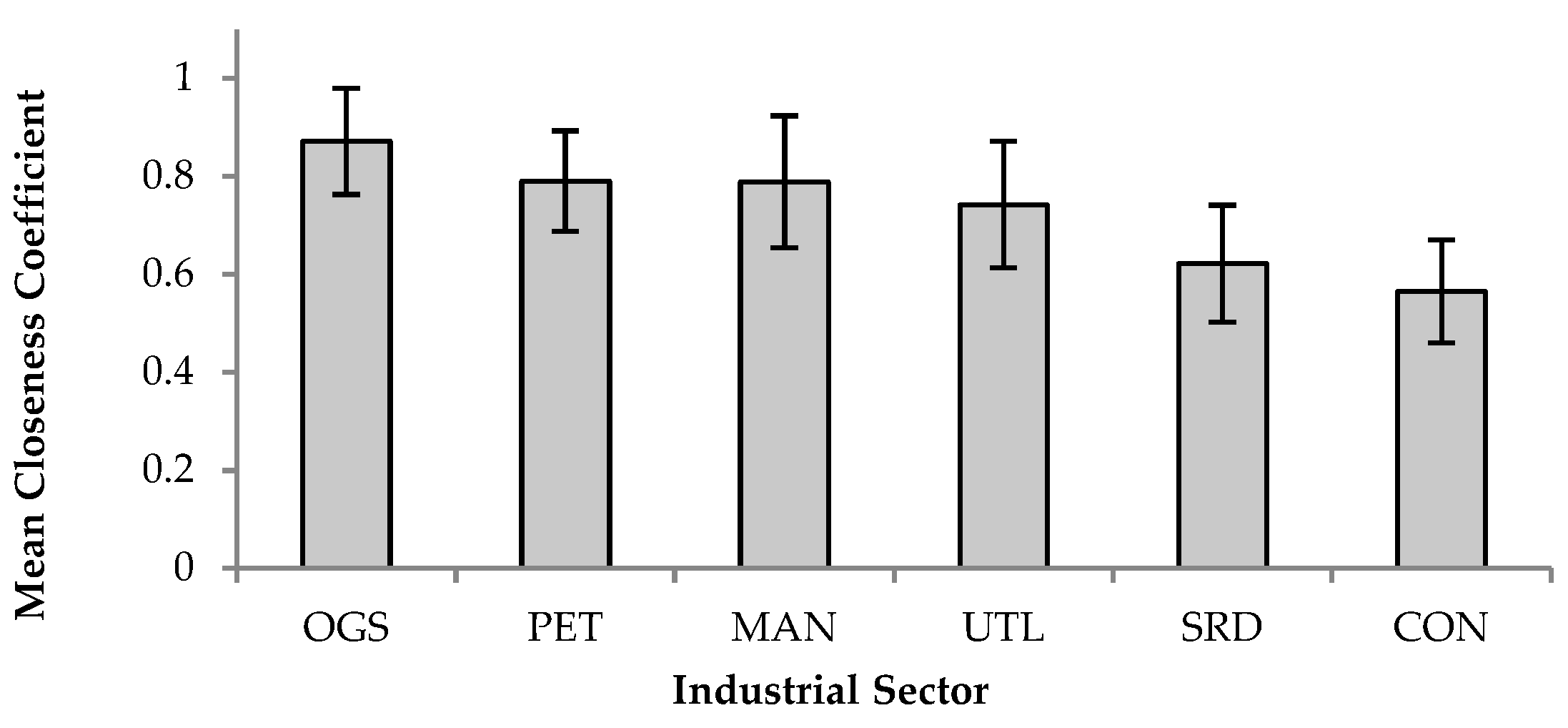

Overall, oil and gas industries had the best performance in writing safety job descriptions, whereas petrochemical, manufacturing, and utility industries had a moderate performance. On the other hand, services/retail/education and construction sectors had the poorest performance. Generally, oil and gas and petrochemicals industries performed well in preparing the safety job description. There is evidence that the two sectors, led by Saudi Aramco and SABIC, follow high-standard safety management and quality management systems [

68]. Saudi Aramco used many strategies to build a safety culture whose roles and responsibilities were emphasized to change core beliefs about safety. This was reflected in their manner of writing safety job descriptions. On the other hand, among Saudi sectors, manufacturing was known to be one of the most inclined to encourage international certification in total quality management systems, whereas service/trade sectors were the least inclined, which agrees with our evaluation. The relatively good performance of the utility sector might have been influenced by the Saudi Electricity Company’s recent interest in becoming internationally certified for its occupational safety and health management system. Safety programs in many Saudi construction companies were found to be inefficient. Al Haadir et al. [

69] reported that 38% of contractors in Saudi Arabia had no trained safety personnel. We believe that inappropriately designed or even the absence of safety job descriptions might be an important reason for that statistic. The findings of the current study indicate the low level of safety job descriptions in the construction sector, suggesting poor safety performance at least up to the near future [

69]. This discussion is supported by the data presented in

Table 9 and the subsequent regression analysis, which quantitively validates the results of the proposed model for evaluating the quality of safety position job descriptions. Integrated AHP-TOPSIS models have been applied successfully to evaluate the safety performance of industries [

38] and manufacturing firm performance [

70], among others.

The safety job descriptions of the manufacturing sector in this study were comparable to those of other sectors known for their high safety performance, e.g., oil and gas and petrochemicals. This is mainly because most of the studied safety job descriptions of this sector were from large companies, owing to the poor response from small and medium industries. Large companies were found to have better occupational safety and health performance compared to small and medium companies within the Saudi manufacturing sector and, furthermore, only 28% of small and medium manufacturing companies had safety personnel, compared to 75% of the large ones [

71]. Therefore, it is expected that the quality of safety job description in the manufacturing sector would sharply decrease if more small and medium industries were included in the study’s overall evaluation.

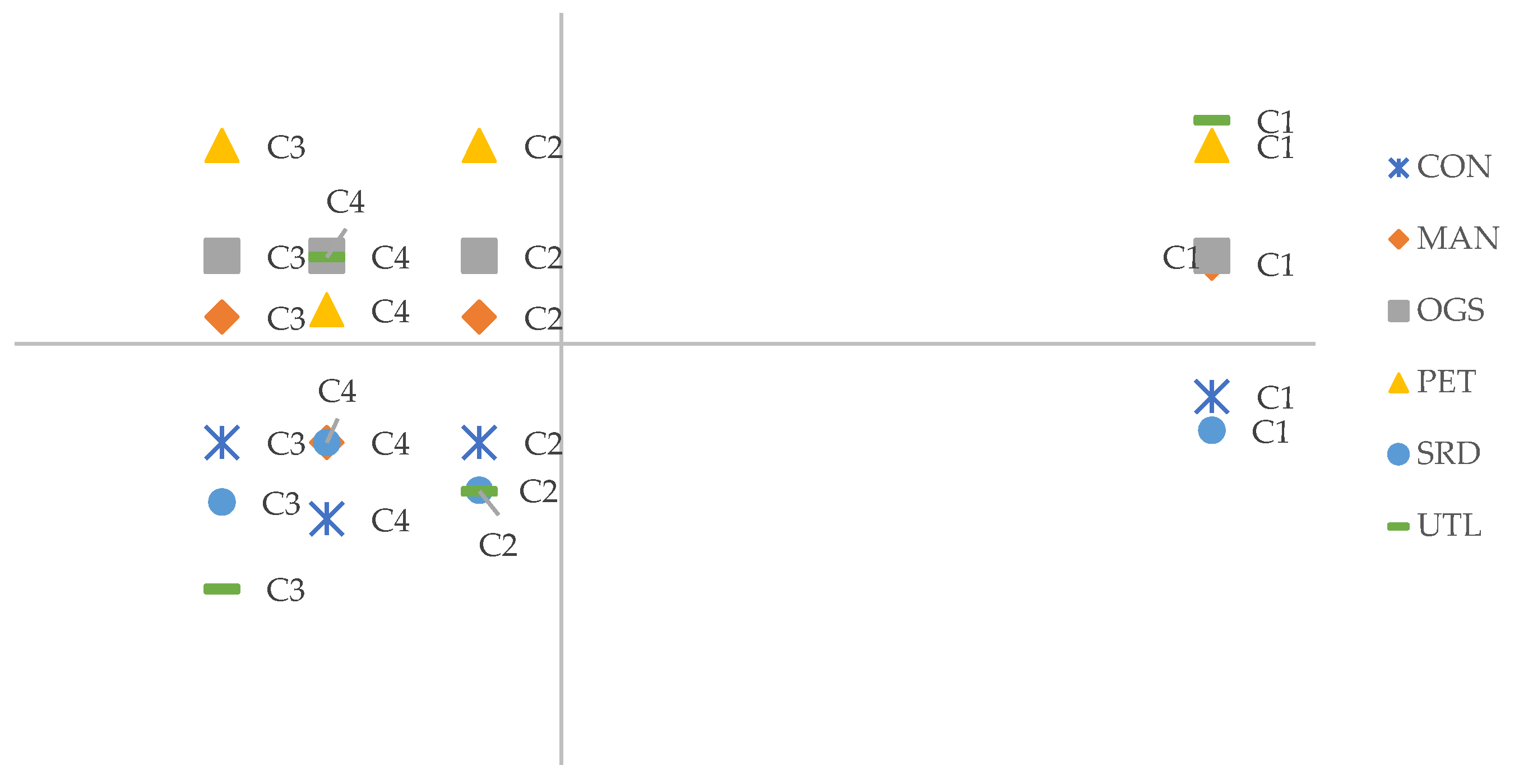

5.2. Importance–Performance Analysis

The sub-criterion “A2: Job level” was found to be a critical issue in all sectors except the oil and gas sector. Specifying job levels in safety position job descriptions is crucial for various reasons [

72]. Firstly, it clearly outlines the expected level of experience, knowledge, and skills required for the role, ensuring that candidates are appropriately qualified. This clarity helps in attracting the right talent and reduces the risk of mismatches between job expectations and candidate capabilities [

73]. Secondly, specifying job levels enables accurate compensation and benefits planning. By clearly defining the role’s level of responsibility and complexity, organizations can ensure that compensation packages are competitive and aligned with industry standards [

74]. This promotes fairness and motivates employees. Thirdly, job level specifications facilitate effective recruitment and selection processes. By clearly outlining the requirements for each level, recruiters can efficiently screen candidates and identify those who possess the necessary qualifications and experience. This streamlines the hiring process and increases the likelihood of selecting the best-suited candidates. Furthermore, job levels provide a framework for setting clear performance expectations and goals. By defining specific responsibilities and deliverables for each level, organizations can establish measurable performance standards [

75]. This promotes accountability, improves performance management, and provides a basis for career progression. Lastly, by identifying the different levels within the safety team, organizations can create clear career paths and development opportunities for their employees. Career growth was found to be a significant factor related to overworking that could improve company performance [

76].

The sub-criterion “B1: Purpose” was found to be a critical issue in the construction and service, education, and retail sectors. Specifying the overall mission of safety-related work in job descriptions is crucial for several reasons. First, it aligns individual goals with organizational objectives. A well-defined mission provides a clear sense of purpose for the role, ensuring that the individual’s efforts contribute directly to the organization’s broader safety goals [

77]. Moreover, a shared understanding of the mission fosters a sense of shared responsibility and encourages collaboration among team members [

78]. Second, a strong mission statement can boost employee morale and engagement by providing a sense of meaning and purpose in their work. In addition, a clear mission can help create a shared commitment to safety among all employees, regardless of their role [

79]. Third, a well-defined mission can be broken down into specific, measurable goals, which can be used to track progress and assess performance. Moreover, by aligning individual performance with the overall mission, organizations can hold employees accountable for their contributions to safety.

The sub-criterion “B4: Brief key responsibilities” was found to be a critical issue in the construction and utility sectors. Specifying brief key responsibilities in safety-related job descriptions is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, it provides clarity and understanding for both the employer and the employee [

80]. By outlining the core duties and expectations of the role, it ensures that both parties are aligned on the responsibilities involved. Secondly, it aids in the recruitment process by attracting qualified candidates who possess the necessary skills and experience to fulfill specific responsibilities [

81]. It helps in identifying candidates who are a good fit for the role and can contribute effectively to the safety team. Thirdly, it facilitates effective performance management by providing a clear framework for setting performance goals and expectations [

82]. By outlining the key responsibilities, it helps in evaluating employee performance and providing constructive feedback. Finally, it supports succession planning by identifying the specific skills and knowledge required for each role. This information can be used to develop training programs and career paths for employees, ensuring smooth transitions and continuity within the safety team. A previous study indicated that the presence of clearly delineated career pathways significantly influences job seekers’ occupational choices, enabling them to make selections that strategically propel them toward their ultimate professional aspirations [

83].

The sub-criterion “C1: Comprehensive” was found to be a critical issue in the construction and service, education, and retail sectors. Specifying the time-consuming tasks in safety-related job descriptions is crucial for several reasons. It helps individuals and managers realistically assess the workload and prioritize tasks effectively. It enables organizations to appropriately allocate resources, such as personnel and budget [

84]. Moreover, by identifying the most time-consuming tasks, individuals can focus their efforts on these areas and optimize their time. It helps prioritize tasks based on their urgency and importance, ensuring that critical safety activities are not neglected [

85]. Additionally, it provides a basis for setting performance metrics and evaluating an individual’s productivity and efficiency, and it helps in setting realistic and achievable performance goals. Moreover, the specific skills and experience required to handle these time-consuming tasks can be identified. Specifying the time-consuming tasks informs training and development needs to ensure smooth transitions and continuity of safety operations.

The sub-criterion “D1: Education-certification” was found to be a critical issue in the service, education, and retail sectors. Specifying minimum education levels and professional certifications in safety-related job descriptions within the service, education, and retail sectors is crucial for several reasons. In sectors that directly interact with the public, such as retail and hospitality, having staff with adequate training ensures the safety of customers and employees [

86]. In education, for instance, staff must be equipped to handle emergencies like fires, natural disasters, or medical incidents. Additionally, by understanding the baseline qualifications, organizations can tailor training programs to address specific skill gaps [

87]. Furthermore, clear education and certification requirements can create pathways for career advancement within the organization [

88]. Qualified staff can identify and mitigate potential hazards, reducing the risk of accidents and incidents.

The sub-criterion “D4: Personal Abilities” was found to be a critical issue in the service, education, and retail sectors. Specifying personal abilities such as communication skills, teamwork, and physical fitness in safety-related job descriptions within the service, education, and retail sectors is crucial for several reasons. For example, clear communication is essential for conveying safety instructions and procedures to employees and customers [

89]. Moreover, in emergency situations, effective communication is vital for coordinating responses and ensuring everyone’s safety. In addition, safety often requires teamwork, particularly in emergency situations or complex projects. A strong team culture can foster a shared sense of responsibility for safety [

90]. Furthermore, many safety-related roles, especially in retail and hospitality, require physical activity such as lifting, bending, and standing for extended periods. Physical fitness is essential for responding to emergencies such as evacuations or first aid situations [

91]. Strong interpersonal skills are necessary for building positive relationships with colleagues, supervisors, and especially in jobs that interact directly with customers.

5.3. Answers to Research Questions

Based on the discussion of the research results, the following is a summary of the answers to the research questions.

According to the TOPSIS results, job descriptions in the oil and gas, petrochemical, and manufacturing sectors are generally more aligned with ideal standards and exhibit more consistency. In contrast, job descriptions in the service/retail/distribution and construction sectors are, on average, less aligned with ideal standards and show greater variability in their assessment, with construction having the lowest overall average closeness to the ideal. This implies the need to review and improve job description quality in the latter sectors.

In the assessment of safety professional job descriptions via the AHP method and expert judgment, “Duties and Responsibilities” is deemed most crucial because it directly defines the critical actions, legal compliance, and performance metrics vital for ensuring safety outcomes. “Qualifications” is the second most important, as it guarantees that the safety professional possesses the essential competences and credibility and meets the regulatory requirements to perform these critical duties effectively. “Job Identity” ranks third, providing the crucial organizational context, scope, and authority necessary for the role’s strategic influence. Lastly, “Job Summary” is considered the least important among these, serving primarily as a high-level overview rather than offering specific, actionable details required for a thorough assessment of the safety role’s functions and effectiveness.

As validation of the proposed AHP-TOPSIS model, a safety performance indicator, namely, safety leadership, was used. Both the average closeness coefficient and the average safety leadership indicator showed a significant positive relationship between the quality of job descriptions of safety positions and the safety performance as indicated by safety leadership. According to the results, OGS had the highest safety leadership index and the highest average closeness coefficient in job descriptions.

Given that construction and service sectors often show lower mean closeness coefficients for safety job descriptions, indicating a greater need for improvement, it is crucial for them to particularly emphasize “Duties and Responsibilities.” This focus is vital because construction involves dynamic, high-risk environments demanding explicit detailing of how safety professionals manage evolving hazards and specific site accountabilities, while service sectors require clear duties to seamlessly integrate safety into diverse, often distributed, daily operations. To achieve this, companies should make duties specific and action-oriented, aligning them precisely with the sectors’ unique hazards, clearly defining the safety professional’s authority, and including responsibilities for communication and training. Moreover, service sectors should prioritize “Qualifications” in safety job descriptions. To achieve this, companies should demand highly specific certifications and training relevant to their sub-sector, emphasize industry-specific experience, and require strong knowledge of sector-specific regulations. “Job Identity” requires significant improvement in safety profession job descriptions across nearly all sectors because its current ambiguity often undermines the safety professional’s authority, creates confusion within the safety management system, hinders career progression, and impacts external credibility. Therefore, companies should integrate these roles seamlessly within the overall safety management system and consider developing a tiered progression for safety roles, all while regularly reviewing and updating these elements for clarity and effectiveness.

5.4. Research Limitations

The analyzed job descriptions were primarily sourced from organizations within Saudi Arabia. Therefore, future studies might investigate the geographical differences between countries in terms of safety professional job descriptions. Additionally, while a diverse range of sectors (oil and gas, construction, manufacturing, utilities, service, education, petrochemical) was included, the study did not encompass all industries where safety professionals play a critical role. Notably, sectors such as healthcare, transportation and logistics, mining, agriculture/agribusiness, information technology (IT), and hospitality/tourism were not within the scope of this research. Each of these sectors presents unique safety challenges, regulatory environments, and specific demands on safety professionals, which could lead to different priorities and competency requirements in their job descriptions. In addition, the assessment was primarily based on the content of publicly advertised or available job descriptions. It is acknowledged that these documents may not always fully reflect the actual day-to-day responsibilities, unwritten expectations, or practical importance assigned to certain duties within an organization. They are often crafted for recruitment purposes and may not capture the full, nuanced reality of the safety professional’s role in practice. Therefore, future studies might apply surveys or interviews with safety managers or supervisors. The IPA method might have some shortcomings, as mentioned by Sever [

92]. For instance, some points might fall in close proximity to the thresholds, making it difficult to interpret the outcomes with a desired level of confidence. Therefore, future studies might combine the IPA with other statistical or analytical methods, such as regression analysis for derived importance or cluster analysis for segmentation, to overcome these shortcomings.

6. Conclusions

Poorly drafted job descriptions for safety positions may have a detrimental influence on the OSH performance of the Saudi industrial and service sectors for various reasons. This can reduce the probability of recruiting highly skilled safety personnel, which are important to the success of firms’ OSH management systems. A poor safety culture results in hiring unqualified safety professionals which, in turn, will negatively impact safety culture in a never-ending cycle. The safety professional will be unclear about the degree of safety education or training they should obtain. The current research demonstrates that the oil and gas and petrochemical industries have better defined job descriptions than other sectors. Their practices should be publicized for the benefit of the other sectors, despite having some gaps. In conclusion, specifying job levels in safety position job descriptions is essential for ensuring clarity, fairness, and effectiveness in recruitment. Specifying brief key responsibilities in safety-related job descriptions is essential for ensuring clarity, efficiency, and effectiveness in recruitment, performance management, and succession planning. By providing a clear understanding of the role’s expectations, organizations can attract and retain top talent, improve employee performance, and build a strong safety culture. Finally, by specifying these personal abilities, organizations can attract and hire individuals who are not only technically competent, but also possess the interpersonal and physical skills needed to excel in safety-related roles. This can lead to a safer and more productive workplace. The research focus of establishing expert-validated best practices allows for the generalization of our findings. The outcomes of this study provide a robust framework that can and should be used by organizations as a guideline to professionalize their job description development and enhance their talent acquisition strategies.