Abstract

The European Union Council’s zero vision aims to eliminate workplace fatalities, while Industry 4.0 presents new challenges for occupational safety. Despite HR professionals assessing managers’ and employees’ competencies, no system currently exists to evaluate the competencies of workers’ representatives in occupational safety and health (OSH). It is crucial to establish the necessary competencies for these representatives to avoid their selection based on personal bias, ambition, or coercion. The main objective of the study is to identify the competencies and their components required for workers’ representatives in the field of occupational safety and health by following the steps of the DACUM method with the assistance of OSH professionals. First, tasks were identified through semi-structured interviews conducted with eight occupational safety experts. In the second step, a focus group consisting of 34 OSH professionals (2 invited guests and 32 volunteers) determined the competencies and their components necessary to perform those tasks. Finally, the results were validated through an online questionnaire sent to the 32 volunteer participants of the focus group, from which 11 responses (34%) were received. The research categorized the competencies into the following three groups: core competencies (occupational safety and professional knowledge) and distinguishing competencies (personal attributes). Within occupational safety knowledge, 10 components were defined; for professional expertise, 7 components; and for personal attributes, 16 components. Based on the results, it was confirmed that all participants of the tripartite system have an important role in the training and development of workers’ representatives in the field of occupational safety and health. The results indicate that although OSH representation is not yet a priority in Hungary, there is a willingness to collaborate with competent, well-prepared representatives. The study emphasizes the importance of clearly defining and assessing the required competencies.

1. Introduction

In the member states of the European Union, during 2021, there were 2,780,440 accidents resulting in recovery periods exceeding four days and 3271 fatal accidents [1]. In order to establish the conditions for safe and healthy working environments and to implement the European Union’s 2021–2027 Strategic Framework on Health and Safety at Work—which calls on member states to commit to eliminating work-related fatalities by 2030 and reducing work-related illnesses by 2030 [2]—the tripartite system of OSH must engage all participants. This system, first introduced by the ILO (International Labour Organization) during its inaugural Governing Body meeting in Washington on 27 November 1919, emphasizes that occupational safety relies on the shared responsibilities and duties of the following three pillars: the state, the employer, and the employee. In this context, workers’ representatives play a crucial role in fulfilling these responsibilities [3]. In addition to mandatory tasks, the Fourth Industrial Revolution [4] presents significant challenges for OSH organizations [5], as the applied procedures and technologies are becoming increasingly complex and require a broader range of knowledge. Participants in OSH can acquire this knowledge through continuous training and education. This knowledge is essential for measuring and developing the skills necessary to perform their tasks effectively. An important consideration is that the type of education, in this case vocational training, determines the goal of the education, and it can be said that the quality of education depends on the implemented curriculum [6].

Hungarian OSH professionals have divided opinions on the activities of workers’ representatives in the OSH field, or as they are more commonly known in Hungary, OSH representatives. While some consider them useful, others view them as a necessary evil [7]. What should these employee-elected representatives do, how should they behave, and what professional OSH knowledge and workplace familiarity should they possess to gain acceptance from OSH professionals, make correct decisions, act effectively, and thus become valuable members of a company’s OSH organization?

A systematic literature review of the competencies of workers’ representatives, conducted using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) protocol methodology [8] on the Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus databases for the period between 2013 and 2023 under predetermined conditions, did not find any comprehensive English-language journal articles on the subject. Consequently, based on the literary definition of competencies and with the help of experts, the expected competencies and their components for workers’ representatives in the field of OSH were compiled.

2. Workers’ Representative in the Field of OSH, OSH Representative

The Lisbon Treaty, amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community, addresses occupational safety in Article 153, specifically focusing on informing workers and consulting with them [9]. The European Union defines the concept of workers’ representatives in various regulations, including those related to collective redundancies [10], transfer of undertakings or businesses [11], the establishment of community-level enterprises [12], and workplace safety and health [13]. While these regulations identify them as representatives of the workers, other terms have also become prevalent. For example, in some Eurofound studies, they are referred to as “employee representatives” [14], or in Hungarian regulations, as “OSH representatives” [15].

According to the European Union directive on improving the safety and health protection of employees, workers’ representatives are employees selected by their peers. These representatives address issues related to worker safety and health in accordance with European and national legislation or practice. This directive defines the minimum rights of employees and workers’ representatives in occupational safety through the employers’ obligations to inform and consult. Member states may establish stricter requirements within their own regulations [13].

3. DACUM (Developing a Curriculum) Process

One approach to defining the necessary competencies and their components is the DACUM process and method, which can be used in the design of educational programs and curricula. The DACUM process is employed to develop educational and training content, along with the supporting curriculum. The goal of the method is to ensure that educational programs focus on the knowledge, skills, and abilities that participants will actually use [16]. It provides information about the knowledge, professional knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for an individual to achieve the performance required to complete a task [17]. During the DACUM process, a group of experts in the specific activity must reach a consensus on the tasks involved in the activity, as well as on the competencies, knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to perform those tasks [18].

The typical steps in the DACUM process generally include the following:

- Selection of participants: Individuals who are most familiar with the target group of the planned educational program or course are selected.

- Identification of job roles: Participants thoroughly study the characteristics, requirements, and tasks of the defined job roles. This helps to identify the skills and knowledge necessary for these positions.

- Identification of skills and knowledge: Through group work, a list of skills and knowledge required to perform the identified job roles is compiled.

- Curriculum and content development: Based on the identified skills and knowledge, the group develops the content of the educational program or course, along with the supporting curriculum.

- Evaluation and feedback: The completed curriculum and content are evaluated, and feedback from participants is used for further refinement.

4. Fundamental and Distinctive Competencies

Nowadays, the term “competence” carries a dual meaning: on the one hand, it signifies authority, entitlement, and jurisdiction, while on the other hand, it denotes professional knowledge, proficiency, and suitability [19].

Even during the English Industrial Revolution, Lyard, a member of the House of Commons, adopted as his motto the now commonplace slogan, “the right man in the right place.” [20]. Despite this, it was not until the 1990s that competency assessment was first applied in practice in the United States, after more than 30 years of research [21].

According to McClelland (1973), competencies are better predictors of workplace performance than IQ (intelligence quotient) or academic achievements [22].

According to Boyatzis (1982), workplace success depends on the alignment between an individual’s competencies and environmental demands. His theory categorizes competencies into three main groups: cognitive, emotional, and behavioral competencies [23].

Spencer and Spencer (1993), in their research, identified the critical competencies required in various professions and the factors that best determine individual performance [24].

Tucker and Cofsky (1994) identified the five main components of competence: knowledge and professional knowledge, skills, traits, self-concepts, and motives [25].

These levels can be further grouped into the following two categories: fundamental competencies, which include knowledge, skills, and professional knowledge; and distinctive competencies, which encompass traits, self-concepts, and motives [26]. Fundamental competencies are often acquired through training and development, while distinctive competencies are generally more difficult to develop [25].

The aim of this research is to identify the fundamental and distinctive competencies of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH, in order to enable them to perform their duties effectively [27]. By defining these components, their suitability can be assessed even before their election, enabling targeted development and subsequent evaluation of their effectiveness.

5. Materials and Methods

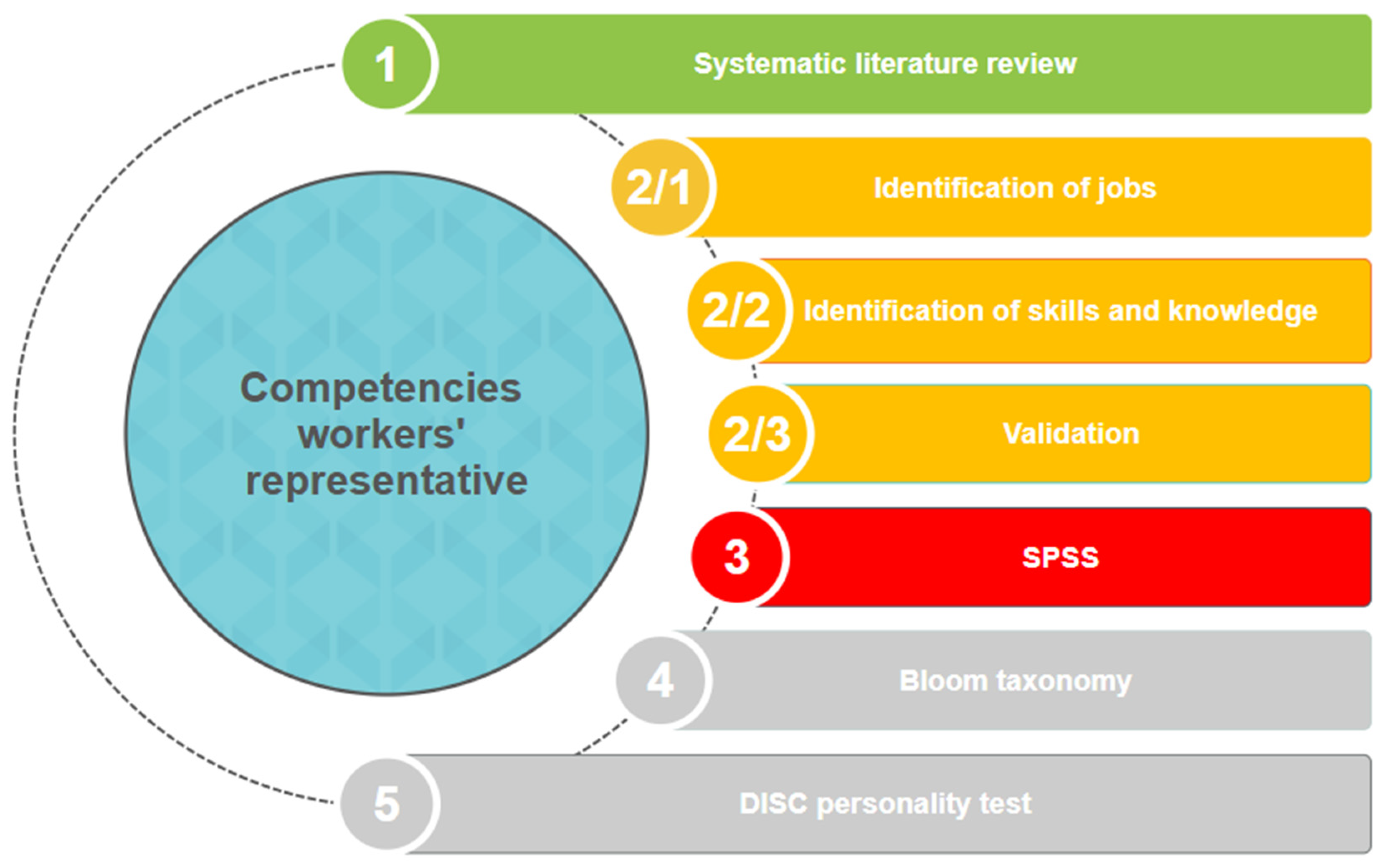

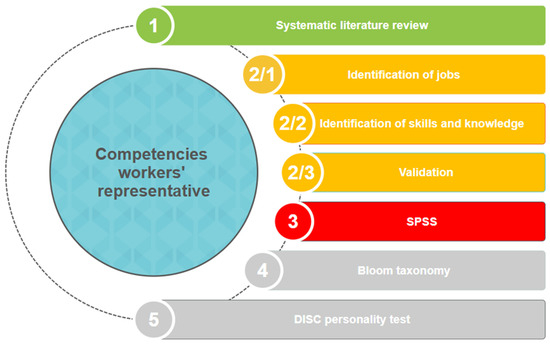

The research was conducted in multiple phases. The steps of the research are presented in Figure 1. First, a systematic literature review was performed using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) method to identify the competencies and their components as expected by professionals. The tasks of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH were identified based on the results of the systematic literature review and relevant legislation [28].

Figure 1.

The research process, source: editing by the authors.

Second, following the first three steps of the DACUM process, the tasks were defined, and research was carried out with the involvement of Hungarian experts.

The research questions were as follows:

- Can the competencies and their components of worker representatives in the field of OSH be determined?

- Are the training tasks of the participants in tripartism distinct?

This article discusses the research series highlighted in orange. In the first phase (the first two steps of the DACUM process) of the current research, the participants were selected based on their in-depth knowledge of the role of workers’ representatives in the field of occupational safety and health. To identify the skills and knowledge required, semi-structured interviews [29] were conducted with eight OSH experts who hold advanced degrees and have over 20 years of professional experience. The experts were selected to represent both the government (2 individuals), employer (4 individuals), and employee (2 individuals) sides. All eight selected experts are Hungarian citizens, work in Hungary, are over 40 years old, and only one of them is a woman.

The interviews aimed to explore their subjective experiences [30]. Originally, 8 questions were compiled in the interview guide [24] based on the literature and preliminary data collection [31]. Based on the feedback, the topic list had been revised based on consultations with professionals within the network [30], resulting in only 5 questions being posed during the interviews. The interviews were conducted via online platforms (such as BBB, Microsoft TEAMS) [7] through individual invitations, and were recorded in both audio and video formats. This method was necessary to prevent obstruction to the interactive component and to enable immediate response to unexpected topics [30]. The participants thoroughly studied the characteristics, requirements, and responsibilities of the role of workers’ representatives in the field of occupational safety and health.

The recorded interviews were transcribed into text using an online speech-to-text program (https://www.textfromtospeech.com/hu/voice-to-text/, accessed on 4 February 2023). Each transcription was listened to multiple times to correct any errors and to mark emotions conveyed in the text [31]. These documents underwent qualitative content analysis [32], also known as thematic analysis, to extract the skills and knowledge expected by the professionals. The abilities identified by the experts were categorized by AI (Artificial Intelligence (https://openai.com/chatgpt/, accessed on 13 October 2024).

In the second phase (the third step of the DACUM process) the identified soft skills and abilities were summarized in a table as part of the competencies. They were complemented with tasks specified in the legislation and were discussed at an online OSH event, where 2 invited guests (one of whom participated in the interview series) and 32 voluntary participants (all of them were employed either as employees or contractors by employers. The distribution by sector was as follows: 6 participants from manufacturing, 4 from trade and motor vehicle repair, 3 from public administration, defense, and compulsory social security, 6 from electricity, gas, steam supply, and air conditioning, 1 from professional, scientific, and technical activities, 3 from human health and social work activities, 5 from construction, 3 from transportation and storage, and 1 from the field of education), acting as a focus group (which is a proven method in organizational development) [33], deliberated on the components of the competencies. At this stage, the focus group compiled a list of the skills and knowledge required to fulfill the identified occupational roles through collaborative group work. Audio and visual recordings were made at the event for later analysis.

In the third phase, accordingly the focus group research, a quantitative questionnaire was compiled using a Google Form, in which the skills and abilities previously determined together were checked with the respondents. This questionnaire was exclusively sent to the members of the focus group.

During the focus group interview, using a descriptive research method [34] and involving OSH experts, the components of the fundamental and distinctive competencies of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH were identified. These components were ranked and validated through a questionnaire with the participants [35].

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Óbuda University (protocol code: OE-SI-BT,42; approved in 2021). All the participants in this study gave their explicit consent. Before agreeing to volunteer, they were given a thorough explanation of the research to ensure they understood the aims, procedures, potential risks, and benefits of the study. They were also told that data processing at this stage would anonymize or de-identify data to ensure secure digital storage and restrict access to sensitive information to authorized individuals. The researchers aim to make the research transparent and reduce the risks to participants.

6. Results

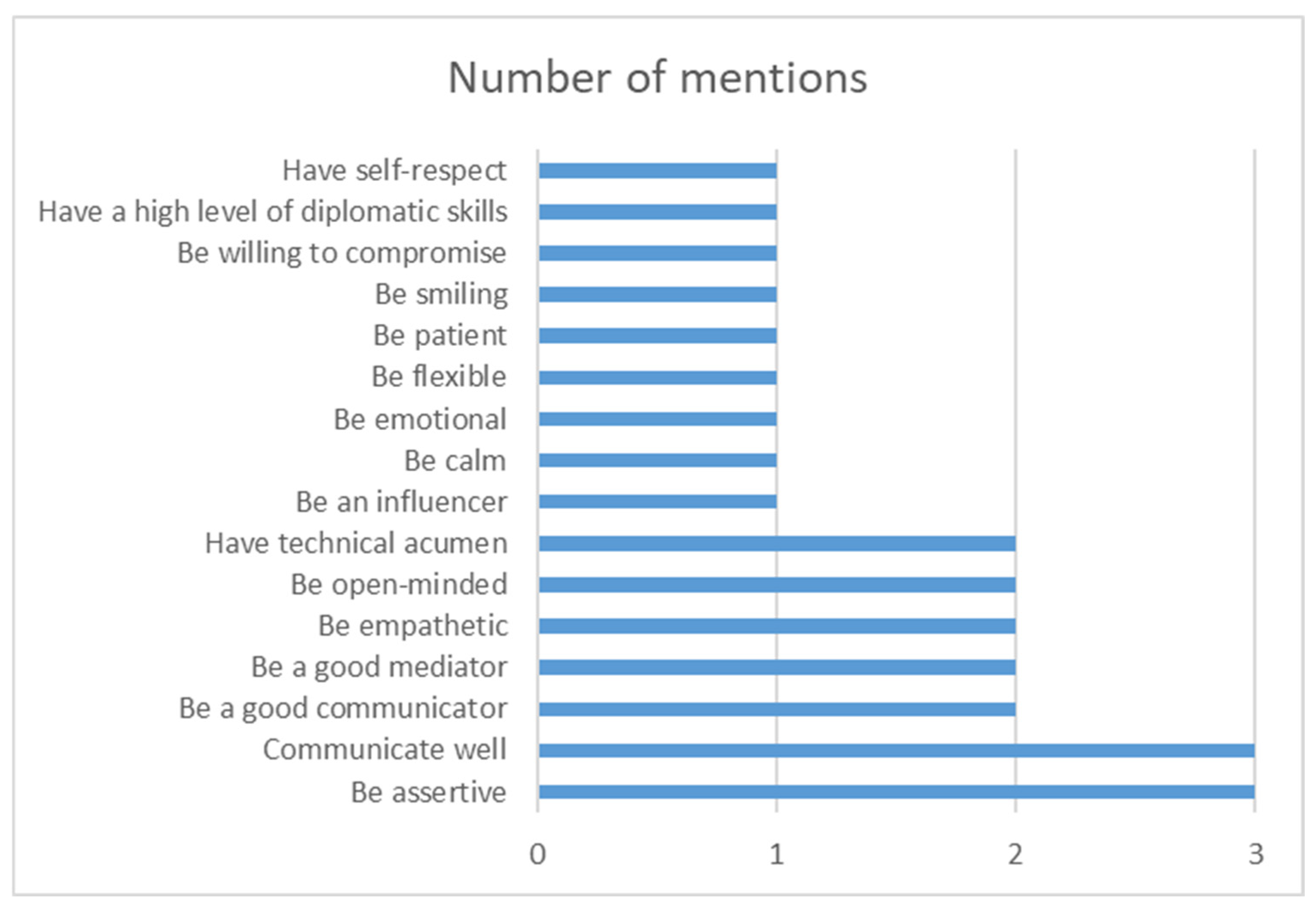

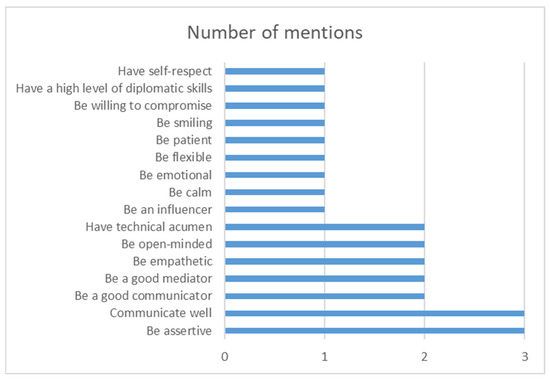

According to the opinions of the eight experts, the OSH knowledge of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH is considered insufficient by OSH specialists. They believe it requires improvement, emphasizing the need for substantial workplace familiarity among them [7]. The qualitative text analysis revealed the soft skills identified by the experts as crucial components of distinctive competencies. These soft skills are presented in Figure 2. It is also evident that these skills are largely related to communication, a finding that reinforces the conclusions of the systematic literature review.

Figure 2.

Components of distinguishing competencies expected by OSH professionals for workers’ representatives in the field of OSH [7].

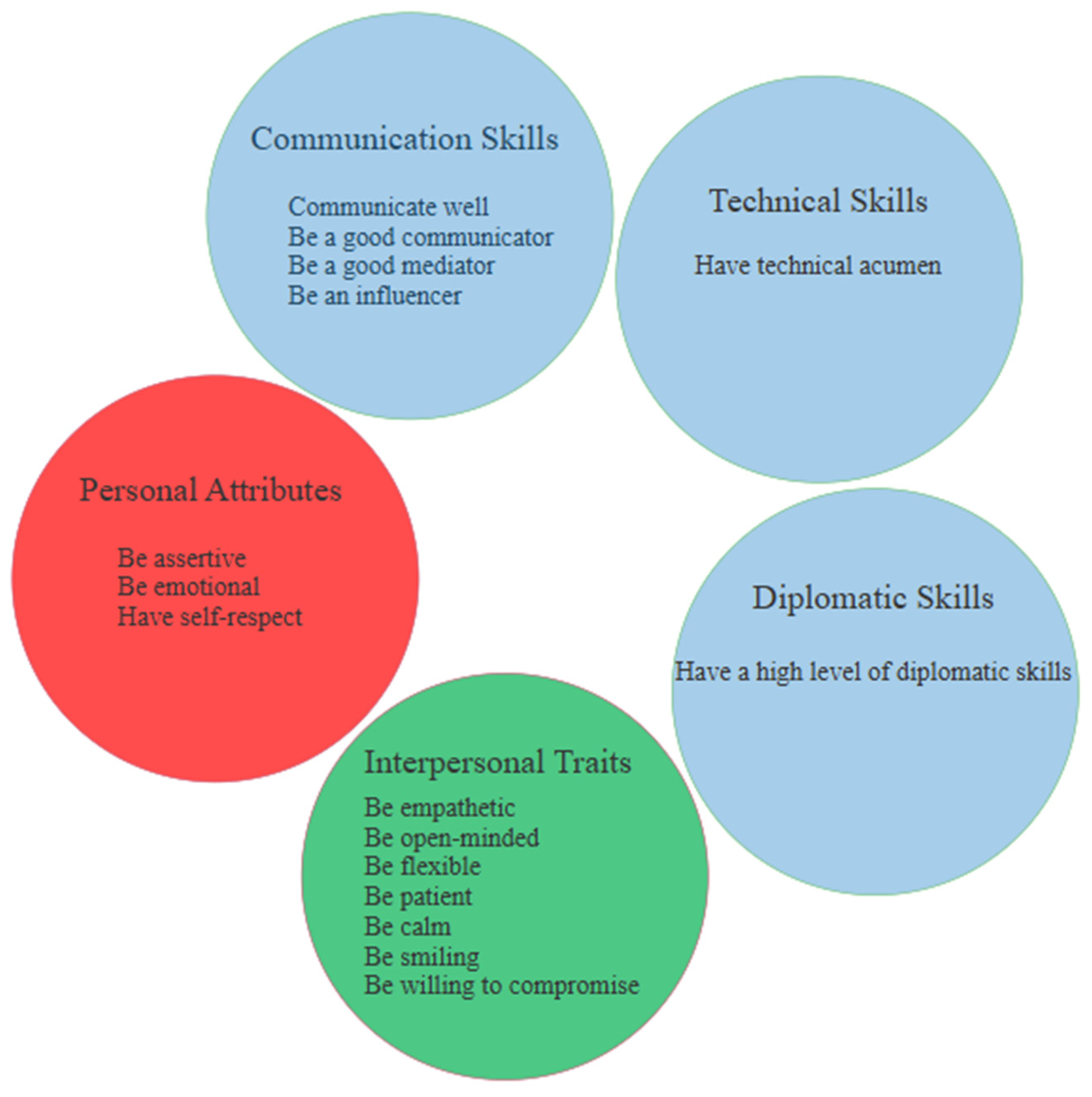

The AI categorized abilities identified by the experts into three major groups: skills (communication, technical, and diplomatic), interpersonal traits, and personal attributes. The categories and category elements created by the AI are shown in Figure 3. These competency components were identified as elements of distinctive competencies.

Figure 3.

The categorization of the said abilities according to the categories selected by AI, source: editing by the authors.

During the focus group research, the OSH and professional knowledge were identified as components of fundamental competencies and skills and traits were refined and confirmed as components of distinctive competencies.

A total of 11 responses were received to the questionnaire sent to the 32 participants of the focus group, representing a response rate of 34%. Upon accessing the form, participants were first required to accept the privacy policy regarding the use of their submitted responses for research purposes. The next option provided was to enter the respondent’s email address, which was not a mandatory field, but providing it would ensure that the respondent received notification about the results. Among the 11 completed forms, only 5 respondents (45%) provided their email addresses.

Among the respondents, seven individuals (64%) were between 28 and 45 years old, while two individuals each (18–18%) were between 46 and 65 years old, and over 65 years old, respectively. In terms of gender, three respondents (27%) were female, while eight respondents (73%) were male. Regarding education, 10 respondents (91%) had higher education qualifications, while only 1 respondent (9%) had intermediate-level occupational health and safety training.

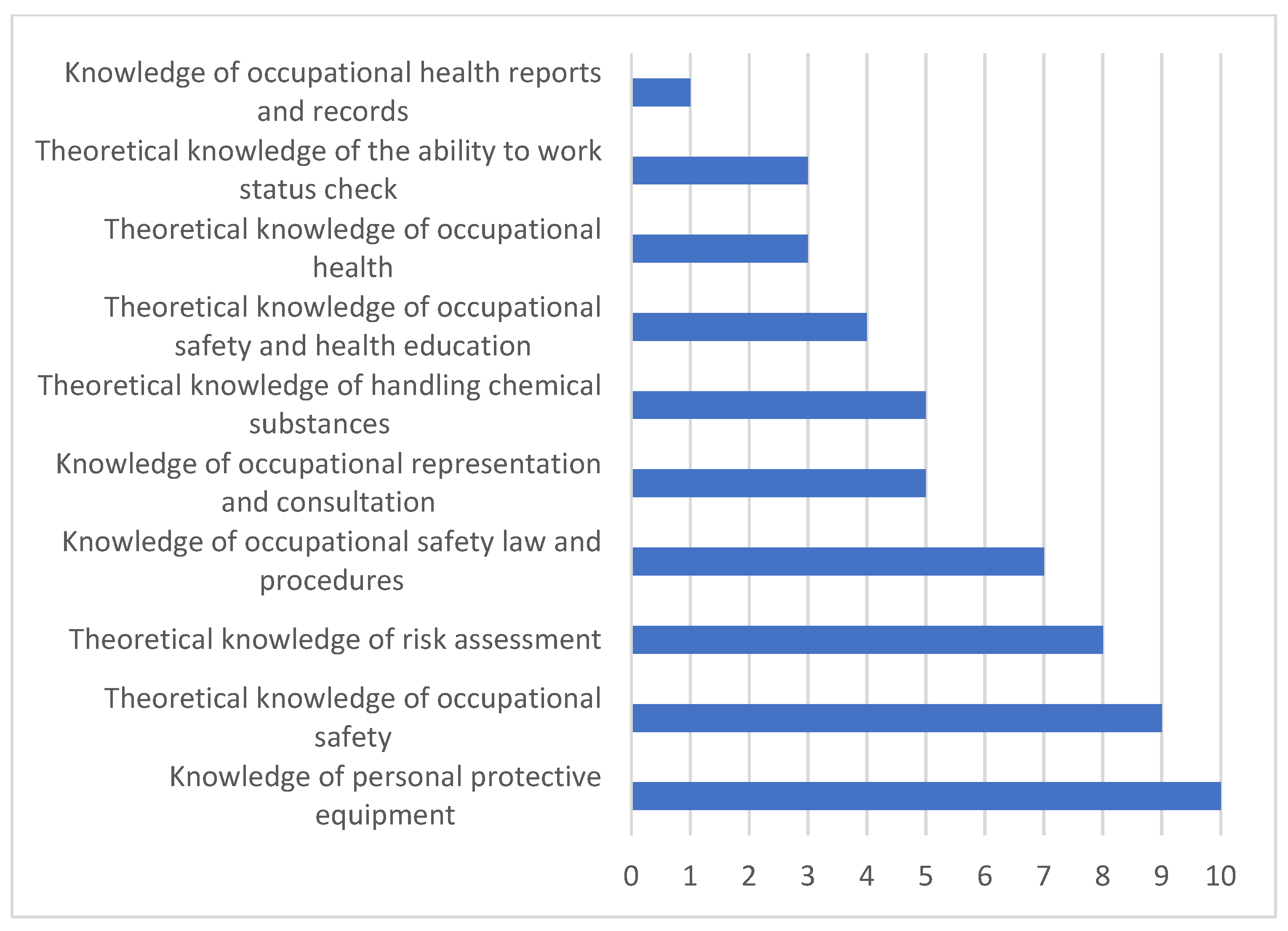

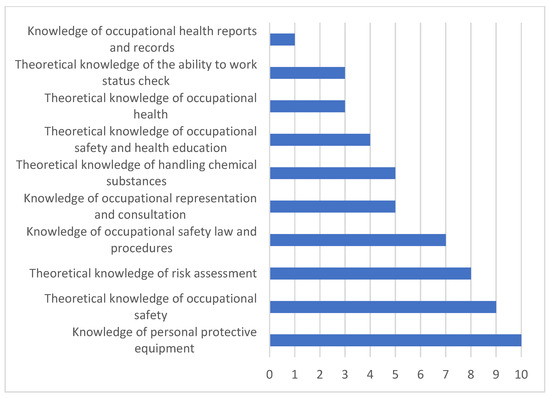

For the occupational safety knowledge components, respondents were asked to select 5 out of 10 options that they consider important. Since each area of knowledge received votes, and no significant additional information was provided in the free-text responses (such as “Fire and environmental safety knowledge”, “Practical skills”, “Psychology”, “Negotiation techniques”), all skills remained unchanged as components of knowledge as a fundamental competency.

Based on the responses, the five most important components were knowledge of personal protective equipment, theoretical knowledge of occupational safety, theoretical knowledge of risk assessment, knowledge of occupational safety law and procedures, and an equal number of votes for knowledge of occupational representation and consultation, as well as for theoretical knowledge of handling chemical substances. The order of the votes received for all components of occupational safety knowledge is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The components of the fundamental competence: occupational safety knowledge of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH, as determined by the focus group, and the number of votes cast in the questionnaire survey, source: editing by the authors.

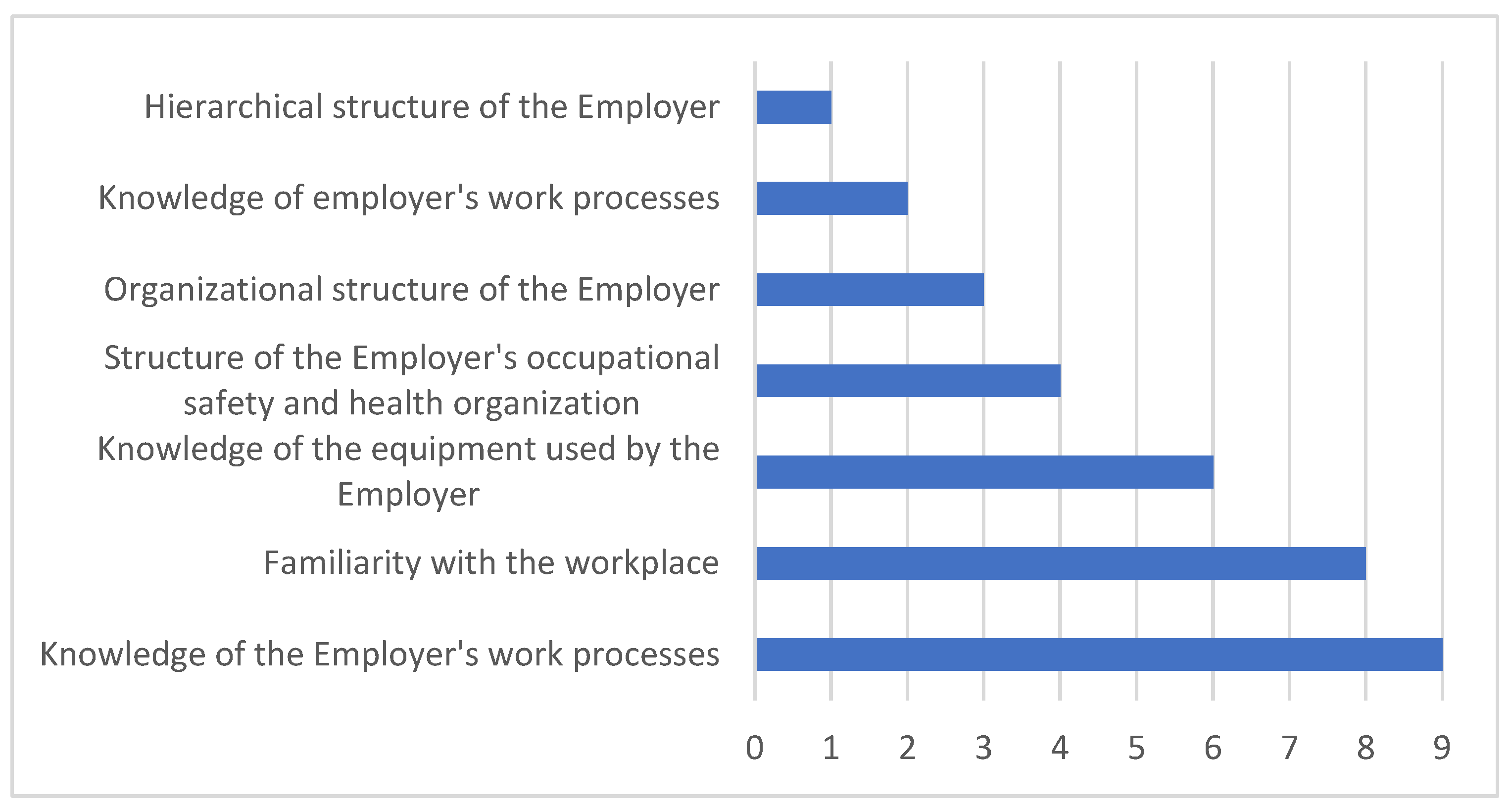

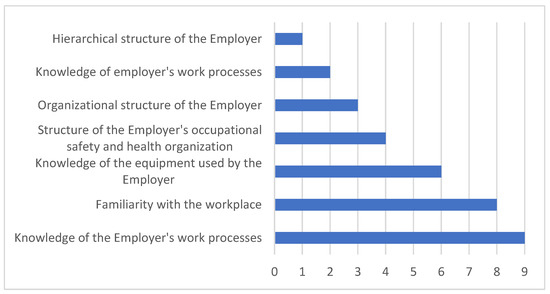

For the professional knowledge components, respondents could select the top three out of seven options. All predefined knowledge received votes, so they remained unchanged as components of professional knowledge.

After processing, it was determined that the three most important workplace skills were knowledge of employer’s work processes, familiarity with the workplace, and knowledge of equipment used by the employer. The order of the votes received for all components of professional knowledge is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The components of the fundamental competence: professional knowledge of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH, as determined by the focus group, and the number of votes cast in the questionnaire survey, source: editing by the authors.

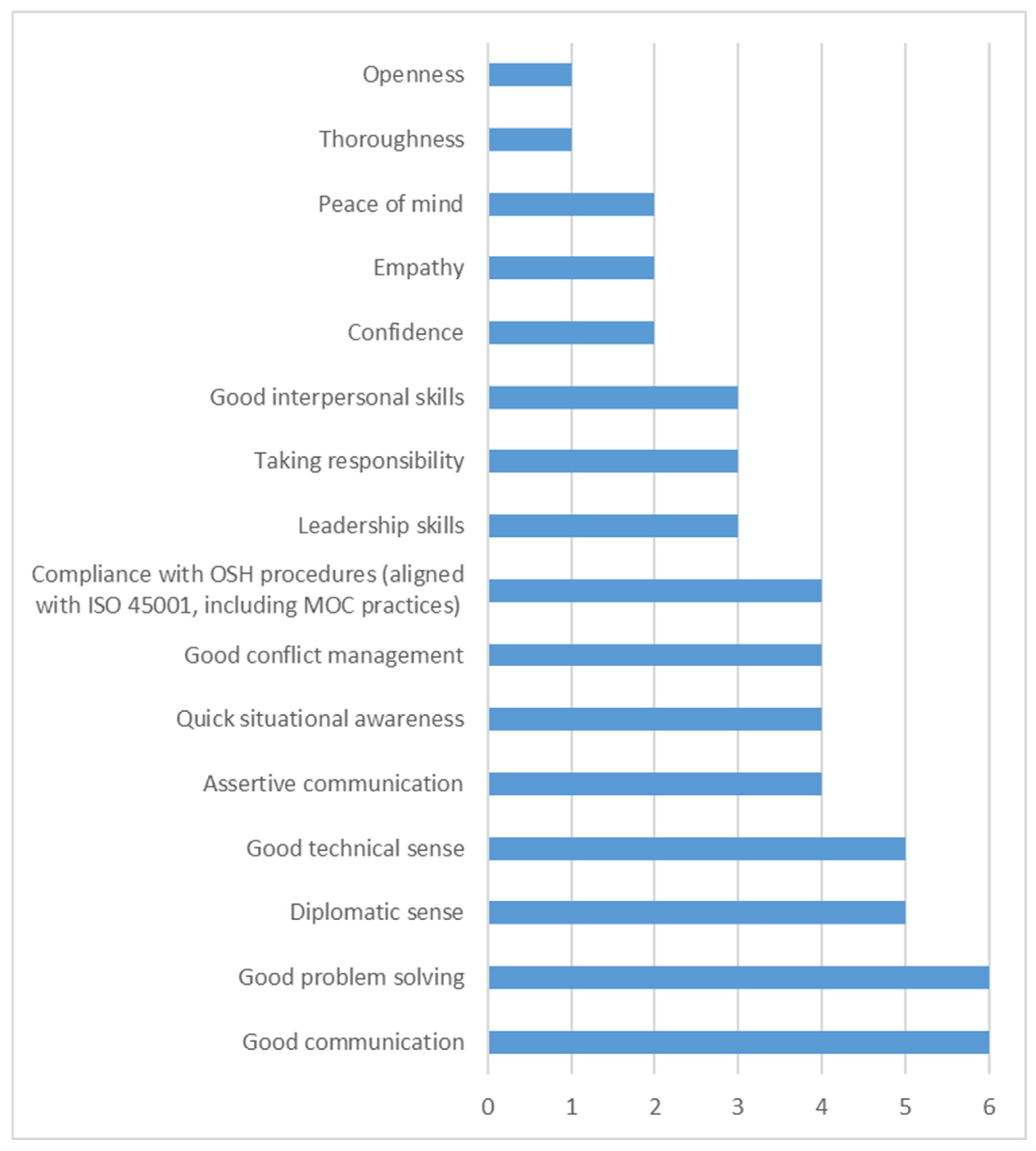

Out of the 16 skills and traits related to the representatives of workers in the field of occupational safety, respondents were asked to select their top 5 according to their opinion. Following feedback and suggestions, the trait ‘thoroughness’ was replaced with ‘accuracy and precision’ for further clarity. Other options remained unchanged. During the examination of distinctive competencies, proposals were made to include additional skills (Cooperation, Collaboration, Initiative), but these were deemed synonymous with existing skills.

The five most important traits, according to the responses, were equally rated for good communication and good problem-solving, as well as for diplomatic sense and good technical sense. The order of the votes received for all components of traits of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH is presented in Figure 6. Similarly, assertive communication, quick situational awareness, good conflict resolution, and compliance with OSH procedures (aligned with ISO 45001 [36], including MOC practices) were equally rated.

Figure 6.

The components of the distinctive competence: traits of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH, as determined by the focus group, and the number of votes cast in the questionnaire survey, source: editing by the authors.

Based on the responses, the components of basic and distinctive competencies necessary for workers’ representatives to fulfill their tasks were determined with the participants’ assistance.

7. Discussion

The competency framework for workers’ representatives in the field of OSH is a multidimensional tool that encompasses occupational safety, professional knowledge, and personal traits. By identifying and developing these competencies, organizations can ensure that representatives are equipped to handle safety-related tasks, contributing to a safer and healthier workplace environment. Their role is legally regulated in the field of OSH [37]. A trained, competent representative has greater influence, as power comes from expertise and knowledge [38].

Based on the semi-structured interviews, it seems that OSH experts would prefer to have workers’ representatives in the field of OSH with at least a secondary level qualification in OSH by their side.

The study examined the competencies expected by professionals from workers’ representatives in the field of OSH. The research highlighted that, similar to determining the competencies required for performing professional tasks, the knowledge, professional knowledge, and characteristics necessary for practicing the mandate of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH can also be identified.

During the research, a total of 33 components of competencies were identified. Out of these, 10 pertain to occupational safety knowledge, 7 to professional knowledge, and 16 to skills and traits. The identified components of competencies highlighted the tasks of the tripartite actors.

The components of occupational safety knowledge (Knowledge of personal protective equipment, Theoretical knowledge of occupational safety, Theoretical knowledge of risk assessment, Knowledge of occupational safety law and procedures, Knowledge of occupational representation and consultation, Theoretical knowledge of handling chemical substances, Theoretical knowledge of occupational safety and health education, Theoretical knowledge of occupational health, Theoretical knowledge of the ability to work status check, and Knowledge of occupational health reports and records) cover the areas required to fulfill tasks expected by the legislator, i.e., the state. These components are essential elements of OSH knowledge as well. Workers’ representatives in the field of OSH, with this knowledge, can expand employees’ understanding of OSH through these components [39].

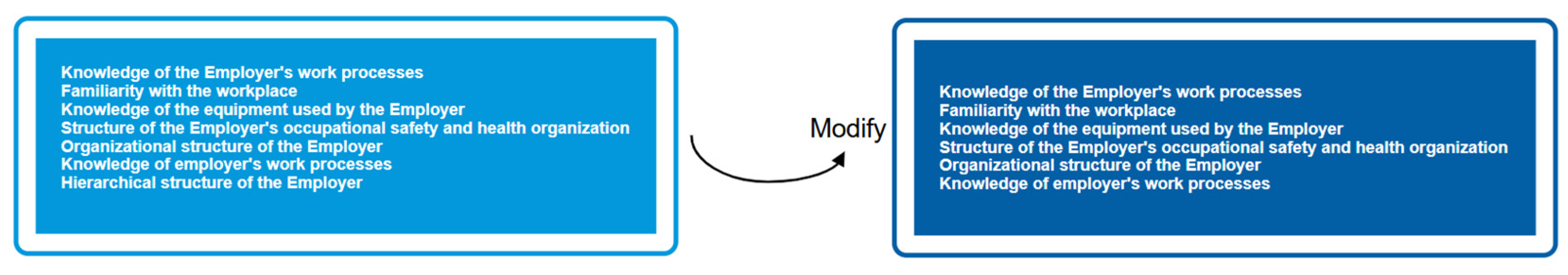

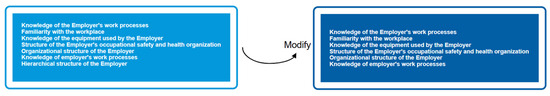

The components of professional knowledge (Knowledge of the Employer’s work processes, Familiarity with the workplace, Knowledge of the equipment used by the Employer, Structure of the Employer’s occupational safety and health organization, Organizational structure of the Employer, Knowledge of employer’s work processes, and Hierarchical structure of the Employer) identified define the training tasks of employers. Components that show a close similarity to each other should be merged, allowing for the modification of the identified elements of professional knowledge. The modification is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The modified components of the fundamental competence: professional knowledge of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH, source: editing by the authors.

With well-structured training programs, workers’ representatives in the field of OSH can more effectively participate in identifying workplace risks [40], and even in the creation of the time structure of the activities [41].

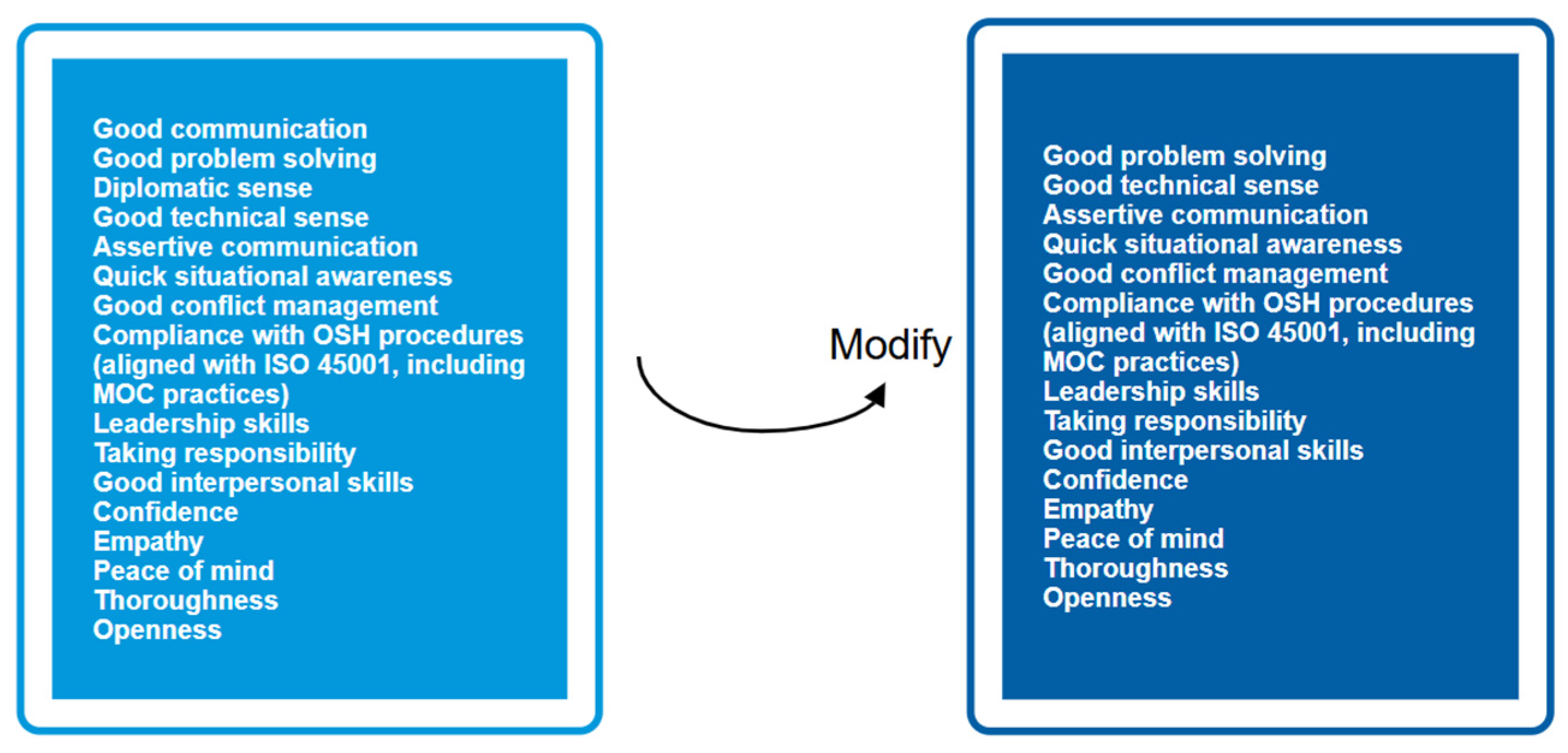

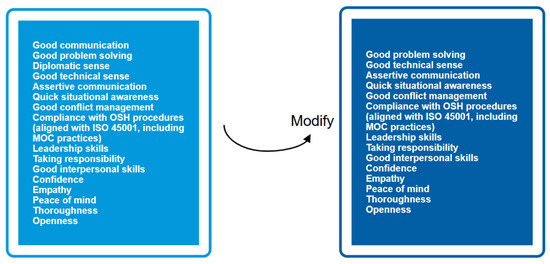

The collected elements of distinctive competencies (Good communication, Good problem solving, Diplomatic sense, Good technical sense, Assertive communication, Quick situational awareness, Good conflict management, Compliance with OSH procedures (aligned with ISO 45001, including MOC practices), Leadership skills, Taking responsibility, Good interpersonal skills, Confidence, Empathy, Peace of mind, Thoroughness, and Openness) represent the education-related tasks of employees, and through them, of representative organizations such as trade unions. In this case, it is also possible to merge components that show a strong similarity to each other. The changes are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The modified components of the distinctive competence: traits of workers’ representatives in the field of OSH, source: editing by the authors.

The components of knowledge and professional knowledge are generally attainable through training and development programs, but components of distinctive competencies are typically difficult to develop [25]. Based on all the identified competency components, it is now possible to select the most suitable workers’ representative(s) in the field of occupational safety [42].

The research was conducted in Hungary, exclusively involving Hungarian experts, so it is not possible to draw general conclusions from it. For a more comprehensive understanding, future research should expand surveys to include EU (European Union) member states or even ILO member countries.

8. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to identify the components of fundamental and distinctive competencies necessary for workers’ representatives in the field of OSH to fulfill their tasks. A competent representative plays an important role in the OSH of an organization by being aware of the professional and workplace responsibilities related to OSH, as well as the behaviors necessary to achieve the goals.

Through the identified components of competencies, a candidate’s suitability can already be assessed during the selection phase. In Hungary, occupational safety knowledge—considered a fundamental competency—can be acquired through mandatory basic and advanced training courses required for workers’ representatives in the field of occupational safety and health. For professional knowledge, it is advisable to examine the candidate’s prior education, professional background, and knowledge of the employer. However, this knowledge can still be acquired through employer-organized training. In contrast, personality traits—which are the components of distinguishing competencies and are generally difficult to develop—should be assessed in advance. A wide range of paid and free personality tests are available for this purpose (e.g., DISC, MBTI, Big Five, Thomas-Kilmann test).

With the components of occupational safety knowledge and professional knowledge as core competencies, the areas for the development of workers’ representatives in the OSH field can be identified. Beyond mandatory training, companies can focus on these areas and organize additional training themselves. In addition to creating a safe and healthy workplace that is attractive to employees, this approach can also reduce the costs associated with workforce loss due to accidents and illnesses.

For the evaluation of selection processes and the outcomes of training, it is essential to conduct performance assessments and follow-up evaluations of workers’ representatives in the OSH field. In Hungary, these representatives are elected for a five-year term, making it crucial that they use this time effectively and have the opportunity to be re-elected.

The goal of legislators in providing training for workers’ representatives in the OSH field is not to increase the number of OSH professionals within companies, but rather to establish a common language between the representatives and the professionals. This could be aided by a later study using Bloom’s taxonomy levels to define the level of knowledge expected from these employees by professionals.

The first research question, which sought to identify the competencies of worker representatives in the field of OSH and their components, has been answered, as a competency profile has been created with the help of OSH experts.

For the second research question, which sought the training tasks required for the participants in tripartism, the responsibilities of the individual actors were clearly delineated. The state is responsible for training related to OSH, which is currently regulated and conducted within the framework of adult education. Regarding professional knowledge and local knowledge, it is primarily the responsibility of employers, where good examples can be seen especially in the case of multinational companies, but it should apply to all enterprises covered by occupational safety regulations. Training for workers should be provided through their representative organizations, although undoubtedly, personality traits are the most challenging components to develop.

The research has shown that a well-trained, confident, and effective communicator as a workers’ representative in the field of OSH can be a valuable and reliable member of the enterprise’s occupational safety organization, with whom OSH professionals are more than willing to collaborate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L.; methodology, G.S.; software, P.L.; validation, G.S. and F.F.; formal analysis, P.L.; investigation, P.L.; resources, P.L.; data curation, G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.L.; writing—review and editing, G.S. and P.L.; visualization, P.L.; supervision, G.S.; project administration, G.S.; funding acquisition, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Obuda University (protocol code: OE-SI-BT,42; approved in 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are unavailable due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eurostat. Statistics Explained—Accidents at Work Statistics. 2015. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- European Commission. EU Strategic Framework on Health and Safety at Work 2021–2027 Occupational Safety and Health in a Changing World of Work; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; pp. 1–21. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0323 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- International Labour Organization. Minutes of the First Session of the Governing Body of the International Labour Office; International Labour Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Liu, T.; Zhou, L. Industry 4.0: Towards future industrial opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2015 12th International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD), Zhangjiajie, China, 15–17 August 2015; pp. 2147–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, A.; Boudreau-Trudel, B.; Souissi, A.S. Occupational health and safety in the industry 4.0 era: A cause for major concern? Saf. Sci. 2018, 109, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentot, W.B. Comparison Between the DACUM and Work Process Analysis for Vocational School Curriculum Development to Meet Workplace Need. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Vocational Education and Training (ICVET), Karang Malang, Indonesia, 14 May 2014; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Péter, L. A munkavédelmi képviselők szerepe a munkavédelmi feladatok ellátásában. Biztonságtudományi Szle. 2023, 5, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Off. J. Eur. Union 2012, 47, 47–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 98/59/EC on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to Collective Redundancies. Int. Eur. Labour Law 2018, 84, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2001/23 on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to the Safeguarding of Employees’ Rights in the Event of Transfers of Undertakings, Businesses or Parts of Undertakings or Businesses. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2018, 2000, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2009/38/EC—Works Council. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, 52, 28–44. [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 89/391/EEC on the Introduction of Measures to Encourage Improvements in the Safety and Health of Workers at Work Edoardo Ales. Int. Eur. Labour Law 2018, 42, 1210–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumayr-Pintar, C. Industrial Relations Employee Representation at Establishment or Company Level: A Mapping Report Ahead of the 4th European Company Survey. 2019. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/eurofound-paper/2020/employee-representation-establishment-or-company-level-mapping (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Évi XCIII. Törvény a Munkavédelemről. 1993. Available online: https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=99300093.tv (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Choi, S.J.; Han, J.S. Job Analysis and Curriculum Design of South Korean Animal-Assisted Therapy Specialists Using DACUM. Animals 2024, 14, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.A.; Stricklin, L.S. Lessons Learned Using the Modified DACUM Approach to Identify Duties and Tasks for CADD Technicians in North Central Idaho. Online J. Workforce Educ. Dev. 2014, 7, 1–14. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/60561442.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Halasz, I.M. Overview of DACUM Job Analysis Process; Revised by Thomas Reid [October 2003], no. September 1994; NIC Information Center: Longmont, CO, USA, 1994. Available online: http://static.nicic.gov.s3.amazonaws.com/Library/010699.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- József, N. Kompetenciamodell és nevelés. Iskolakultúra 1997, 7, 71–77. Available online: https://www.iskolakultura.hu/index.php/iskolakultura/article/view/18571 (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Szilvia, S. Kompetencia Alapú Emberi Erőforrás Gazdálkodás; Nemzeti Közszolgálati Egyetem, Közigazgatási Továbbképzési Intézet: Budapest, Hungary, 2020; Available online: https://nkerepo.uni-nke.hu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/15664/Kompetenciaalapuemberieroforras-gazdalkodas.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Matiscsákné, L.M. (Ed.) Emberi Erőforrás Gazdálkodás; Wolters Kluwer Kft.: Budapest, Hungary, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D.C. Testing for competence rather than for ‘intelligence’. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, L.M.; Spencer, P.S.M. Competence at Work Models for Superior Performance; Wiley India Pvt. Limited: New Delhi, India, 2008; Available online: https://books.google.hu/books?id=2Y8QB-6aIJMC (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Tucker, S.A.; Cofsky, K.M. Competency-based pay on a banding platform: A compensation combination for driving performance and managing change. ACA J. 1994, 3, 30. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/competency-based-pay-on-banding-platform/docview/216362458/se-2?accountid=134728 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Spencer, L.M.; McClelland, D.C.; Spencer, S.M. Competency Assessment Methods: History and State of the Art; Hay/McBer Research: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; Available online: https://books.google.hu/books?id=YgN9tAEACAAJ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Ruiz, M.J.S.; Molina, R.I.R.; Amaris, R.R.A.; Raby, N.D.L. Types of competencies of human talent supported by ICT: Definitions, elements, and contributions. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 210, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisztner, P.; Szabo, G. The competencies and tasks of workers’ representatives in the field of occupational health and safety: A systematic literature review. IETI Trans. Ergon. Saf. 2024, 8, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, E.; Kuyper, M. 4 Het half open interview als onderzoeksmethode. In Kwalitatief Onderzoek; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, H. 3 Systematiek en toepassing van de kwalitatieve survey. In Kwalitatief Onderzoek; Lucassen, P.L.B.J., olde Hartman, T.C., Eds.; Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetto, L.; Wick, W.; Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Systematic Approach. In Compendium for Early Career Researchers in Mathematics Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, R. Doing Focus Groups; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. The Basics of Social Research; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Third Edition: Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research Approach; SAGE Publications Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; 520p. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 45001; Occupational Health and Safety. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-67-10788-2.

- Majhosev, A.; Paraklieva, V. Legal and institutional framework for safety and health at work in the Republic of North Macedonia. J. Process Manag. New Technol. 2019, 7, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.B.; Munduate, L.; Elgoibar, P.; Wendt, H.; Euwema, M. Competent or Competitive? How Employee Representatives Gain Influence in Organizational Decision-Making. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2017, 10, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragó, F. A tudás, mint sikertényező a munkavédelemben Magyarországon működő vállalatok tudásmenedzsment gyakorlatának kvalitatív felmérése. Biztonságtudományi Szle. 2022, 4, 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Erazo-Chamorro, V.C.; Arciniega-Rocha, R.P.; Rudolf, N.; Tibor, B.; Gyula, S. Safety Workplace: The Prevention of Industrial Security Risk Factors. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedny, G.; Karwowski, W.; Bedny, I. Time Structure Analysis in Task with Manual Components of Work. Adv. Ergon. Des. Usability Spec. Popul. Part II 2022, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, V.; Sebt, M.H. Competency-based selection and assignment of human resources to construction projects. Sci. Iran. 2011, 18, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).