Abstract

Occupational accidents are a serious public health issue. In this retrospective observational study, we examined all injuries involving healthcare workers of the Abruzzo Local Health Authority No. 1 (Italy) during the three years 2019–2021. Data were collected by tracing the injury reports filed by the emergency service during the workers’ admission and analyzing the cause, type, distribution by sex, and geographical district to which they belonged, taking into account the period before and during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Most injuries (45.7%) were reported in the Marsica area; the most common cause was commuting accidents (10.7%). Assaults were more common among men (8.6%), while commuting accidents were more common among women (11.8%). In 36% of cases, the upper limbs were affected. The most common type of injury was contusions (22.2%). When the frequency of reports was compared between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, there was an increase in injuries in healthcare assistants (p = 0.052), while the percentage of injuries in administrative (p = 0.056) and other categories decreased (p = 0.002). This analysis allows us to identify points of interest relating to the Marsica area, to specific types of accidents, such as aggression and commuting accidents, and to specific duties.

Keywords:

workplace; occupation; accident; healthcare workers; injury; local health authority; COVID-19; pandemic 1. Introduction

There are several hazards that healthcare professionals are exposed to, and these risks are quite concerning. These risks include accidents, hygienic-environmental risks, and transversal risks, which encompass various aspects of work organization, with a particular emphasis on psychological and ergonomic factors [1].

The variables that can contribute to creating conditions that put healthcare workers’ safety at risk are numerous and are inherent in the characteristics of the population being studied (level of training, age, sex) and of the patients (clinical conditions, type of pathology, level of assistance required), as well as the hospital structure (organization, shifts, workload). This makes healthcare workers the category of workers that are most vulnerable to accidents, both in the EU and the US [2].

The most frequently reported injuries among healthcare personnel are accidental puncture wounds and cuts, contact with infected material, trauma, and musculoskeletal problems due to patient handling and lifting [3,4,5,6].

Moreover, as the pandemic progressed, healthcare workers were affected by several work challenges [7] and at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 due to their proximity to infected individuals. Furthermore, the strain placed on the healthcare system only served to exacerbate the heavy workload and psychological burden on these vulnerable individuals. Because stress can be an indirect determinant of occupational issues [8,9], a thorough investigation into the indirect effects of the pandemic on healthcare workers and other similarly vulnerable populations is critical [10,11].

The present study examines the occupational accidents reported between 2019 and 2021 by healthcare workers from Abruzzo Local Health Authority No. 1, considering the period before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through a comparison of injuries that occurred in the pre-COVID and the COVID periods, we aim to identify possible changes in injured workers’ characteristics or in the frequency and types of injuries. The relevant scientific literature is investigated to further characterize the phenomenon and to better understand the results. Implementing preventive and improvement strategies can help achieve the goal of minimizing the frequency of occupational accidents, thus safeguarding worker health and safety, mitigating the socioeconomic impact on the organization, and managing issues such as absenteeism and staff turnover.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective study examines all of the accidents that occurred to workers in the various districts of the Abruzzo Local Health Authority No. 1 (L’Aquila, Marsica, and Peligno-Sangrina areas). This study was authorized by the Ethics Committee (EC) of the Local Health Authority Avezzano-Sulmona-L’Aquila, Abruzzo Region, Italy (minutes dated 16 July 2020, n° 21); it covers a period of three years between 2019 and 2021 and includes accidents that were reported by the emergency room where the injured workers were treated. The collected data provided demographic information about the injured healthcare workers, including their age, sex, and details about the injury itself, such as the type and cause of injury and the affected body part (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification by body part affected, type of injury, and causes of injury.

Based on the emergency care accessed after the injury (which, in almost all cases, corresponded to the workplace), workers were divided into the districts of L’Aquila, Marsica, and Peligno-Sangrina. As for their duties, workers were divided into nurses, chief physicians, healthcare assistants, administration staff, and other roles (drivers, physiotherapists, midwives, biologists, and more). Briefly, the three involved areas have the following characteristics:

- The L’Aquila area is mainly characterized by service enterprises. It hosts the University of l’Aquila and the regional hospital, which is a university hospital. The city of l’Aquila is the regional capital of Abruzzo;

- The Marsica area is mainly characterized by manufacturing and agricultural enterprises. It hosts a 250-bed hospital;

- The Peligno-Sangrina area hosts a small hospital and is characterized by agricultural and service businesses.

The presentation of continuous variables is given as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Numbers and percentages are used to represent categorical variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to evaluate the normality of the distribution of continuous variables, and, according to its results, the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney test was used for variable comparison. To compare three or more groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used, and Dunn’s test was used to perform pairwise comparisons. To evaluate the link between continuous variables, Spearman’s rank correlation was utilized. p-values less than 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using STATA 18.0 software.

3. Results

From 2019 to 2021, 722 injuries were reported over a population of approximately 3774 workers (data from 2021), consisting of 2702 females (71.6%) and 1072 males (28.4%). Of the accidents concerned, 197 (27.3%) occurred in male workers, and 525 (72.7%) occurred in female workers. No significant difference existed in the percentage of injuries (27.3% affecting males and 72.7% affecting females) between the two groups (p = 0.4583). The percentage of injuries in males and females for both groups amounted to 18.4% for males (197 injured in a sub-sample of 1072) and 19.4% for females (525 injured in a sub-sample of 2702). These data are consistent with the gender distribution of the analyzed population. The mean age of the injured workers was 49.9 ± 9.6 years.

The highest percentage of injuries was reported in the Marsica area (330; 45.7%), followed by the L’Aquila area (230; 31.9%) and the Peligno-Sangrina area (162; 22.4%). Such a different geographic distribution was statistically significant (p < 0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of the injuries by district and percentage of the injuries by workers.

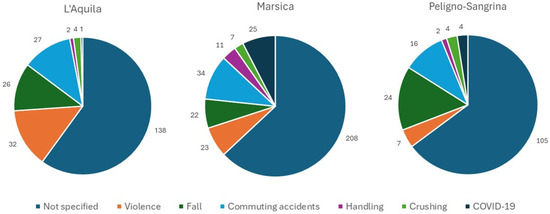

In most reports drafted by the emergency department, the cause of injury was not specified. Thus, without considering the unspecified cases, commuting accidents were the most frequent cause of injury (10.7%). The least frequent causes were handling and crushing. As shown in Figure 1 and in Table 3, the most common cause of injury was significantly different for each area (p < 0.0001): violence for the L’Aquila area (13.9%); commuting accidents for the Marsica area (10.3%); and falls for the Peligno-Sangrina area (14.8%) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the causes of injury by district.

Table 3.

Distribution of the causes of injury by district.

In addition, the distribution of the causes of injuries was different between the female and male groups, with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.008). Without considering the injuries for unspecified causes, Table 4 shows that violence was the most common cause of injury among men (8.6%), while commuting accidents were the most frequent cause of injury among women (11.8%).

Table 4.

Percentage of the causes of injury between males and females.

The upper extremities were the most affected body part (36.0%), while the trunk was the least affected part (3.3%) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of the body parts affected.

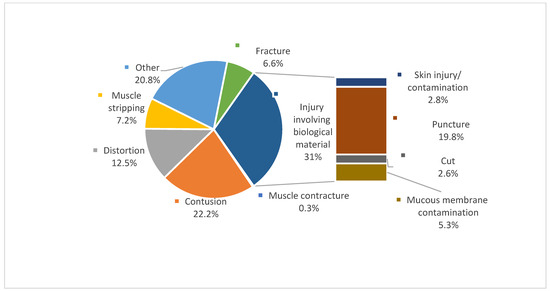

Figure 1 reports the types of injuries. Contusion was the most frequently reported injury (22.2%), while muscle contractures were the least frequently reported injury (0.3%).

The mean recovery time estimate was 7.2 ± 8.2 days; however, there were differences in the mean recovery time estimate by district: the L’Aquila area: 6.7 ± 8.5 days, the Marsica area: 7.6 ± 7.8 days, and the Peligno-Sangrina area: 7.2 ± 8.6. Such differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.1603). No significant differences existed between women and men in the estimated recovery time (p = 0.9257). However, a significant difference existed in the estimated recovery time for each body part affected (p = 0.001) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Median recovery time estimate for body part affected.

Finally, we compared the pre-pandemic period (January 2019–February 2020) with the pandemic period (March 2020–November 2021), excluding COVID-19-related injuries (n. 30). Throughout this period, 692 injuries were reported, of which 301 (43.5%) were reported in the pre-pandemic period and 391 (56.5%) during the pandemic. The monthly average number of injuries decreased from 21.6 to 20.0; however, this difference was not significant (p = 0.4574). The average age of the workers who sustained an injury (50.0 vs. 50.1; p = 0.8520) and the sex distribution (p = 0.163) remained unchanged over the two periods. Most injuries were recorded in the Marsica area in both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. However, no difference existed in the injury distribution by area over the two periods studied despite the decrease in the percentage of injuries reported in areas with a higher concentration of workers (the L’Aquila and Marsica districts).

Regarding the leading causes of injuries, we observed an increase in the percentage of falls over the pandemic period and a decrease in the percentage of workplace violence and commuting accidents. However, none of these differences were significant (Table 7).

Table 7.

Distribution of the causes of injuries over the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods.

Additionally, we observed some significant differences in the distribution of injuries caused by different occupations over the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods (p = 0.003) (Table 8). Injuries among nurses and healthcare assistants increased (p = 0.052), while the percentage of injuries among the administration personnel (p = 0.056) and other categories (p = 0.002) decreased. Though not significant, we observed an increase in the percentage of injuries among nurses (p = 0.187). The percentage of injuries sustained by chief physicians remained unchanged.

Table 8.

Distribution of injuries caused by duty over the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods.

4. Discussion

Healthcare workers might be exposed to several occupational health and safety hazards that may have a substantial clinical, economic, and human burden. Healthcare workers face a wide range of hazards, including bloodborne pathogens, violence at work, exposure to harmful chemicals and drugs, excessive physical stimulation, infectious diseases, and shift work. In Western countries, occupational injury rates are higher among healthcare workers than employees working in other industries [12,13]. Healthcare workers have direct contact with infected patients and with their body fluids. In addition, they often perform procedures that expose them to possible lesions. Other hazards involve ergonomic/physical injuries. Musculoskeletal injuries resulting from patient-handling tasks and from overexertion are the most common traumas sustained by healthcare workers. Musculoskeletal injuries, which may involve muscles, nerves, tendons and ligaments, joints, and cartilage, result from repetitive movements, awkward postures, contact stress, or vibration [3]. Physical violence is a further occupational hazard that has a serious impact on the well-being and job satisfaction of healthcare workers, thus affecting job performance and the quality of care delivered. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), between 8% and 38% of health workers suffer physical violence at some point in their careers [14]. Violence and aggression against healthcare workers seem to be particularly high in emergency departments [15]; previous research reported that up to 75% of violence cases occurred in emergency departments, in the intermediate care, psychiatry, and geriatric units [16,17].

An analysis of the accident reports issued by the emergency department allows us to promptly collect data in order to detect any emerging phenomena. The goal of defining the evolution of phenomena—including those in relation to the pandemic period—can be considered fulfilled.

Our research highlights a relevant aspect regarding the causes of injuries: for 451 cases, accounting for 62.5% of the overall cases, the cause of injury was not reported. In addition, in 133 cases, accounting for 18.4% of the overall cases, we had to classify the body parts injured under the item ‘other’ because the description was incomplete and injuries were ascribed to generic causes; in 150 cases, accounting for 20.8% of the overall cases, we had to classify the type of injury under the item ‘other’ because the description was generic and incomplete. As stated, our analysis highlights relevant missing or incomplete information, especially in the “injury cause” reporting. This result may be interpreted as an alarm for healthcare management. However, emergency department information collection may be challenging. According to Murphy et al. [18], information mistakes may occur during clinical practice in an emergency department. They found that information accuracy, completeness, or availability may be affected by several problems during the patient-care process and healthcare workflow. Similar issues are highlighted by the same authors in different, more recent research [19]. Some hospital departments, including emergency departments and surgical wards, may have a bad reputation for collecting inadequate documentation, and the data they gather are frequently incomplete or unclear.

Regarding the causes of injury, further relevant data are represented by commuting accidents (10.7%) and violence-related injuries (8.6%). For these injuries, the causes were clearly reported, yet some important details useful for risk assessment were lacking. Indeed, it was not always clear whether violence-related injuries were perpetrated by patients, visitors, colleagues, chief physicians, etc. According to what we stated in the previous paragraph, deficient information is a relevant problem in healthcare facilities, especially in emergency departments [18,19]. Several injuries were caused by falls (10% of the overall cases), almost as many as commuting accidents.

Another significant datum concerns the types of injuries; in fact, 30.5% of these injuries were associated with biohazards. In particular, of the overall injuries, 5.3% were from mucous membrane contamination; 2.8% were from skin contamination; 2.6% were from cuts; and 19.8% were from needlesticks. Partially comparable research points out that biohazards represent a major issue in occupational prevention and control in the healthcare sector [20]. In accordance with our findings, a puncture is considered the most common biologically related injury. With regard to the remaining types of injuries identified in our study (Figure 2), a recent study [21] confirmed that muscular issues, distortions, and fractures are frequent among healthcare workers.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the injuries by type.

Information derived from the emergency department only describes the body part affected without reporting the use of PPEs, equipment, or the type of procedure performed at the moment of the injury. Such information would be relevant to improve specific training programs or to identify a shortcoming in healthcare facility risk management.

Our results are not consistent with the results of several studies in that female workers are more vulnerable to injuries [17,22,23].

Likewise, the data obtained by dividing the causes of injuries by district are particularly relevant. The most common causes of injuries were violence in the L’Aquila district (13.9%), commuting accidents in the Marsica district (10.3%), and falls in the Peligno-Sangrina district (14.8%). Below, we highlight some useful advice or preventive measures that may be executed by the local health authority in order to reduce the most frequent injuries on the basis of a specific geographical district. For the area of L’Aquila, considering that injuries related to violence reached a high percentage, it would be desirable to strengthen the security service. In addition, according to the scientific literature [24], the visible presence of security staff may increase the safety perception of healthcare practitioners. For the Marsica district, where commuting accidents are the most common cause of injury, providing a bus service supplementary to public transport, an on-site canteen, theoretical/practical safe driving training programs, awareness-raising campaigns, etc., might be a possible solution. As suggested by Delgado-Fernandez et al. [25], some policy interventions promoted by regional governments and institutions, including road safety education programs, may help reduce driving-related occupational injuries. The Peligno-Sangrina district is characterized by its almost 15% rate of fall-related injuries. According to Italian occupational health and safety regulations [26], fall prevention in occupational settings may be achieved through compliance with business safety procedures and rules. Such an assertion implies that the use of PPEs, the effective use of training courses, and the workplace’s suitability are ensured by enterprise management.

Limited to the pandemic’s impact on injury trends in the studied facility, our data show that there were notable variations in the distribution of injuries among various occupations between the pre-pandemic and pandemic eras. The percentage of injuries among administrative staff and other categories decreased, whereas injuries among nurses and healthcare assistants increased. We saw an increase in nurses’ injury percentage, but the chief physicians continued to sustain the same percentage of injuries. However, as shown in the Results section, we observed a declining trend in the number of injuries weighted as a monthly average. Such findings are comparable to a similar study carried out by Diktas et al. [27]. They observed that total injuries decreased from the pre-COVID period to the COVID period; task-specific injuries decreased, too. In the cited research, biological accidents decreased in the considered period, but this datum differs from our findings: we observed an increase in biological injuries. Diktas et al. interpreted these results to be a consequence of effective training courses and an increased availability of PPEs.

In relation to the pre-COVID and COVID periods, we observed an increase in fall injuries. As is known, facing the COVID-19 pandemic requires massive use of PPEs by health professionals. A recent study [28] highlighted that “A person who has impaired peripheral vision may compensate with an altered posture and gait, increasing the likelihood of falls.” According to the cited research, vision restrictions may be due to the PPEs used in the healthcare sector. Such an explanation of our findings should be further investigated through an “on the field” investigation in the studied workplaces.

The limitations of our research are mainly due to the lack of data related to COVID-19 injuries, to the difficult analysis and reconstruction of the causes of injuries from the reports drafted by the emergency department (the data collected did not allow us to correlate the injuries with the type of patients treated, or with the work shift at the time of the injury), and to the difficult retrieval of the total number of workers for each year because in the three years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the healthcare turnover was particularly dynamic.

5. Conclusions

The COVID pandemic impacted trends in accidents among healthcare workers. This survey of healthcare injuries shed some light on the criticalities of this sector in order to expand our knowledge and plan possible corrective actions both to implement monitoring and preventive strategies for the protection and safety of workers [29] and monitor the costs of work-related injuries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization L.F., C.C. and P.G.; methodology M.M., P.G. and L.F.; software R.M., M.M., C.C. and P.G.; validation L.F.; formal analysis M.M.; investigation, S.F., P.G., C.C. and R.M.; resources L.F., S.F. and C.C.; data curation R.M., M.M., C.C. and P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C. and P.G.; writing—review and editing G.M. and R.M.; visualization, M.M., R.M. and G.M.; supervision L.F. and S.F.; project administration L.F.; funding acquisition not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Local Health Authority Avezzano-Sulmona-L’Aquila, Abruzzo Region, Italy (minutes dated 16 July 2020, n° 21).

Informed Consent Statement

According to Italian law, studies based entirely on registry data are exempt from informed consent (D.Lgs 10/08/2018, n.101; Authorisation No. 9/2016—General Authorization for the Processing of Personal Data for Scientific Research Purposes 15 December 2016, https://www.garanteprivacy.it/home/docweb/-/docweb-display/docweb/5805552; accessed on 2 February 2024). Furthermore, data reported in this study cannot be linked to the involved patients.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marta Fiorenza for the English translation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Debelu, D.; Mengistu, D.A.; Tolera, S.T.; Aschalew, A.; Deriba, W. Occupational-Related Injuries and Associated Risk Factors Among Healthcare Workers Working in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. Health Serv. Res. Manag. Epidemiol. 2023, 10, 23333928231192834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Incidence Rates of Nonfatal Occupational Injuries and Illnesses by Industry and Case Types, 2022. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.bls.gov/web/osh/table-1-industry-rates-national.htm#soii_n17_as_t1.f (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Dini, G.; Parodi, V.; Blasi, C.; Linares, R.; Mortara, V.; Toletone, A.; Bersi, F.M.; D’Amico, B.; Massa, E.; et al. Protocol of a scoping review assessing injury rates and their determinants among healthcare workers in western countries. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garus-Pakowska, A.; Ulrichs, M.; Gaszyńska, E. Circumstances and Structure of Occupational Sharp Injuries among Healthcare Workers of a Selected Hospital in Central Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, J.; Magalhães, J.; Leite, M.; Aguiar, B.; Ponte, P.; Barrocas, J.; Norton, P. Musculoskeletal injuries and absenteeism among healthcare professionals-ICD-10 characterization. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, V.K.; Lavoie, M.-C.; Verbeek, J.H.; Pahwa, M. Devices for preventing percutaneous exposure injuries caused by needles in healthcare personnel. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD009740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tjasink, M.; Keiller, E.; Stephens, M.; Carr, C.E.; Priebe, S. Art therapy-based interventions to address burnout and psychosocial distress in healthcare workers—A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cremasco, M.M.; Vigoroso, L.; Solinas, C.; Caffaro, F. Discomfort in Use and Physical Disturbance of FFP2 Masks in a Group of Italian Doctors, Nurses and Nursing Aides during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Safety 2023, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, S.; Morando, M.; Caruso, A.; Scuderi, V.E. The Effect of Psychosocial Safety Climate on Engagement and Psychological Distress: A Multilevel Study on the Healthcare Sector. Safety 2022, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acito, M.; Rondini, T.; Gargano, G.; Moretti, M.; Villarini, M.; Villarini, A. How the COVID-19 pandemic has affected eating habits and physical activity in breast cancer survivors: The DianaWeb study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 17, 974–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, P.; Cipollone, C.; Martinelli, R.; Caputo, F.; Cervellini, M.; Mammarella, L.; Muselli, M.; Mastrantonio, R.; Mastrangeli, G.; Fabiani, L. Vaccination status among COVID-19 patients and duration of Polymerase Chain Reaction test positivity: Evaluation of immunization schedule and type of vaccine. Ann. Ig. Med. Prev. Comunità 2024, 36, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressner, M.A. Hospital Workers: An Assessment of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses. Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2017. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/hospital-workers-an-assessment-of-occupational-injuries-and-illnesses.htm (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Miller, K. Risk factors and impacts of occupational injury in healthcare workers: A critical review. OA Musculoskelet. Med. 2013, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dillon, B.L. Workplace violence: Impact, causes, and prevention. Work 2012, 42, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, R.A.; Morris, L.; Smith, I. A qualitative meta-synthesis of emergency department staff experiences of violence and aggression. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2018, 39, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaducci, G.; Stubbs, B.; McNeill, A.; Stewart, D.; Robson, D. Violence in mental health settings: A systematic review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sossai, D.; Molina, F.S.; Amore, M.; Ferrandes, G.; Sarcletti, E.; Biffa, G.; Accorsi, S.; Belvederi Murri, M.; Tomellini, M.J.; Copello, F. Analysis of incidents of violence in a large Italian hospital. Med. Lav. 2017, 108, 6005. (In Italian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.R.; Reddy, M.C. Identification and management of information problems by emergency department staff. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2014, 2014, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Murphy, A.R.; Reddy, M.C. Identifying patient-related information problems: A study of information use by patient-care teams during morning rounds. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 102, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengel, B.E.; Tigen, E.T.; Bilgin, H.; Dogru, A.; Korten, V. Occupation-Related Injuries Among Healthcare Workers: Incidence, Risk Groups, and the Effect of Training. Cureus 2021, 13, e14318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alharbi, S.M.; Alghanem, A.K.; Alessa, H.A.; Aldoobi, R.S.; Busayli, F.A.; Alharbi, K.S.; Alzahrani, A.S.; Kashkari, K.A.; Huraib, M.M.; Harbi, S.S.A.; et al. Most common ergonomic injuries among healthcare workers. Int. J. Commun. Med. Public Health 2021, 8, 5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofini, V.; Capodacqua, A.; Calisse, S.; Galassi, I.; Cipollone, L.; Necozione, S. Trend analysis and factors associated with biological injuries among health care workers in Southern Italy. Med. Lav. 2018, 109, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, H.; Yu, S.; Drebit, S.; Fast, C.; Kidd, C. Are female healthcare workers at higher risk of occupational injury? Occup. Med. 2009, 59, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, B.; Affleck, J. Verbal abuse and physical assault in the emergency department: Rates of violence, perceptions of safety, and attitudes towards security. Australas. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2017, 20, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Fernández, V.J.; Rey-Merchán, M.d.C.; López-Arquillos, A.; Choi, S.D. Occupational Traffic Accidents among Teachers in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Consulenze Specialistiche in Materia di Appalti per Imprese e Pubbliche Amministrazioni Negli Ambiti di (Cip Srl). Italian Legislative Decree n. 81 of 9 April 2008. Implementation of Art. 1 of Law No 123 of 3 August 2007 on the Protection of Health and Safety at Work; Official Gazette, n. 101, 30/04/2008, Ordinary Supplement n. 108; Official Gazette: Rome, Italy, 2008.

- Diktas, H.; Oncul, A.; Tahtasakal, C.A.; Sevgi, D.Y.; Kaya, O.; Cimenci, N.; Uzun, N.; Dokmetas, I. What were the changes during the COVID-19 pandemic era concerning occupational risks among health care workers? J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1334–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruskin, K.J.; Ruskin, A.C.; Musselman, B.T.; Harvey, J.R.; Nesthus, T.E.; O’Connor, M. COVID-19, Personal Protective Equipment, and Human Performance. Anesthesiology 2021, 134, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Macrì, M.; Acito, M.; Villarini, M.; Moretti, M.; Bonetta, S.; Bosio, D.; Mariella, G.; Bellisario, V.; Bergamaschi, E.; Carraro, E. DNA damage in workers exposed to pigment grade titanium dioxide (TiO2) and association with biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 105, 104328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).