The Illusive Pipedream of Zero Harm: A South African Mining Industry Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. OHS Performance Metrices

1.2. Business Ethics and OHS Regulation

1.3. Decent Work, and Views from a South African Regulatory Context

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Reporting Context and Format

3.2. OHS Performance

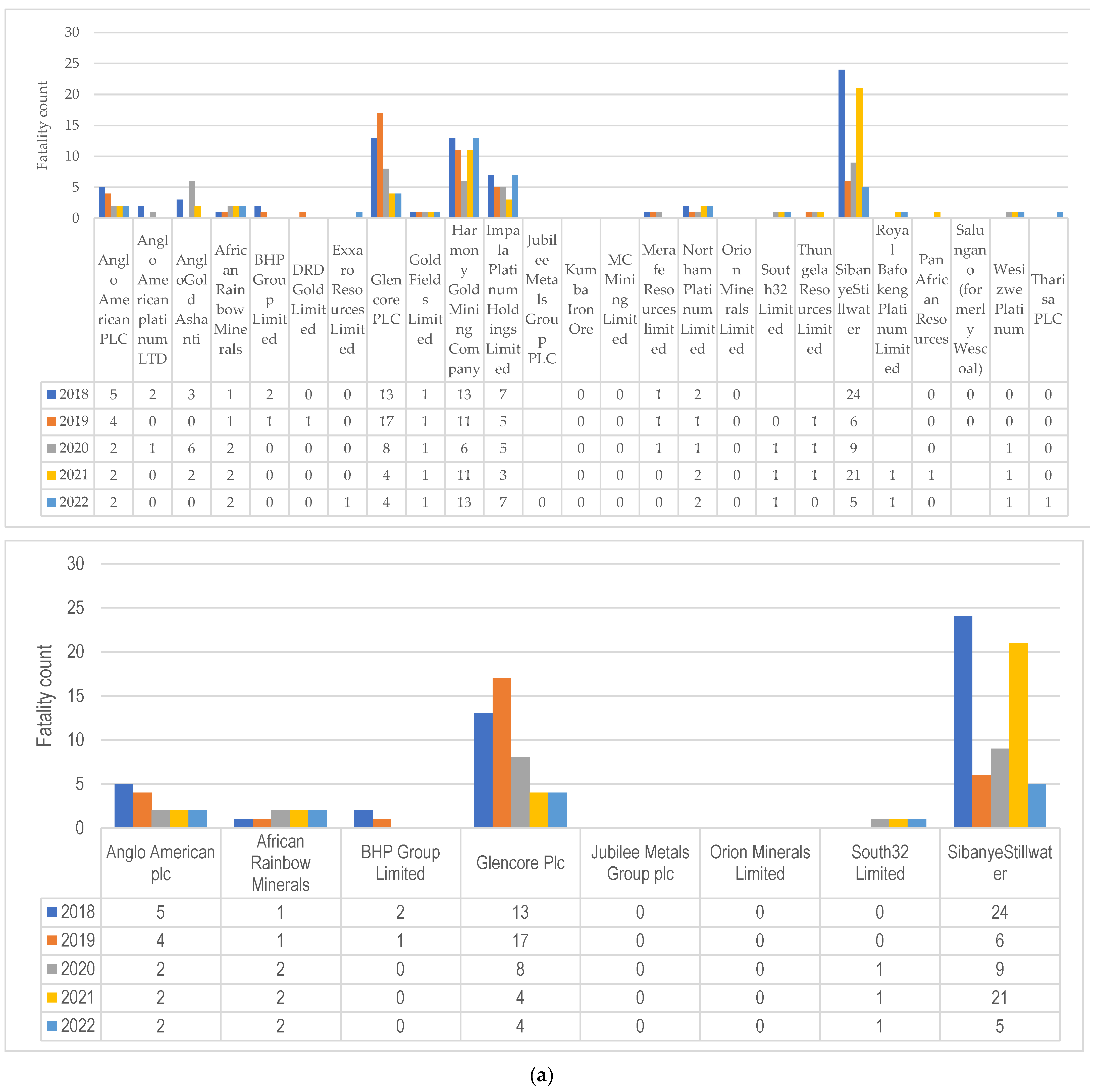

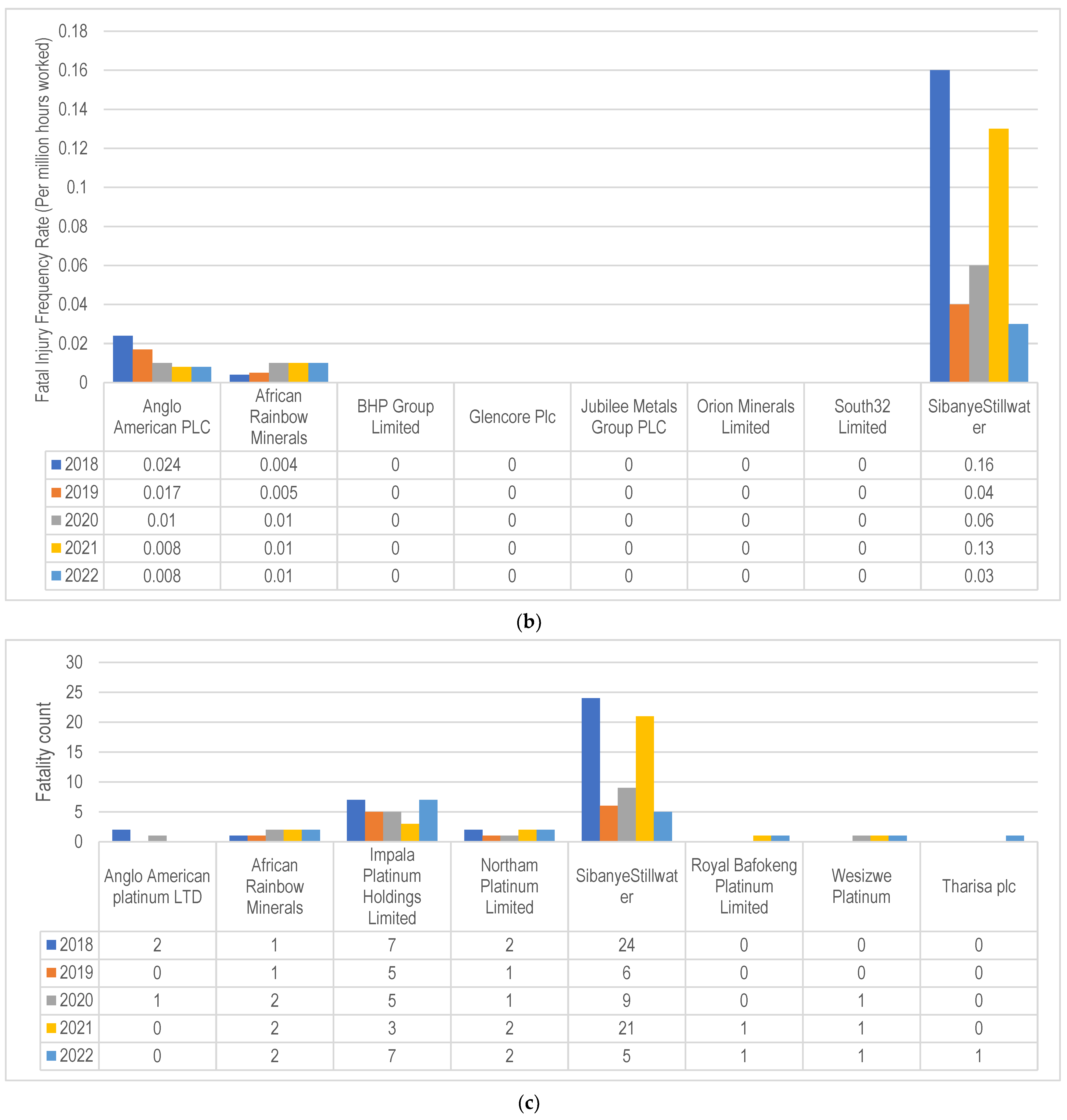

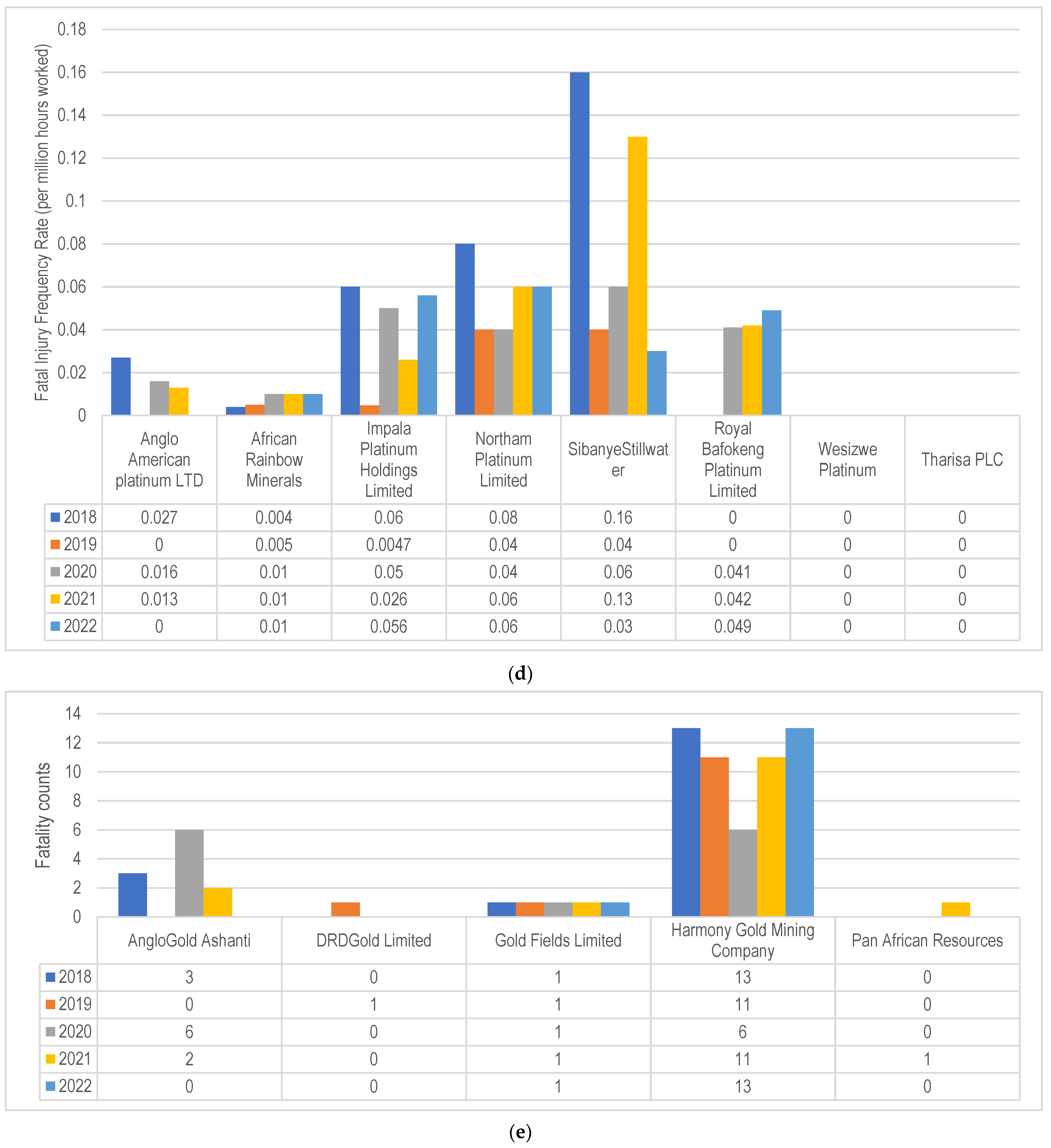

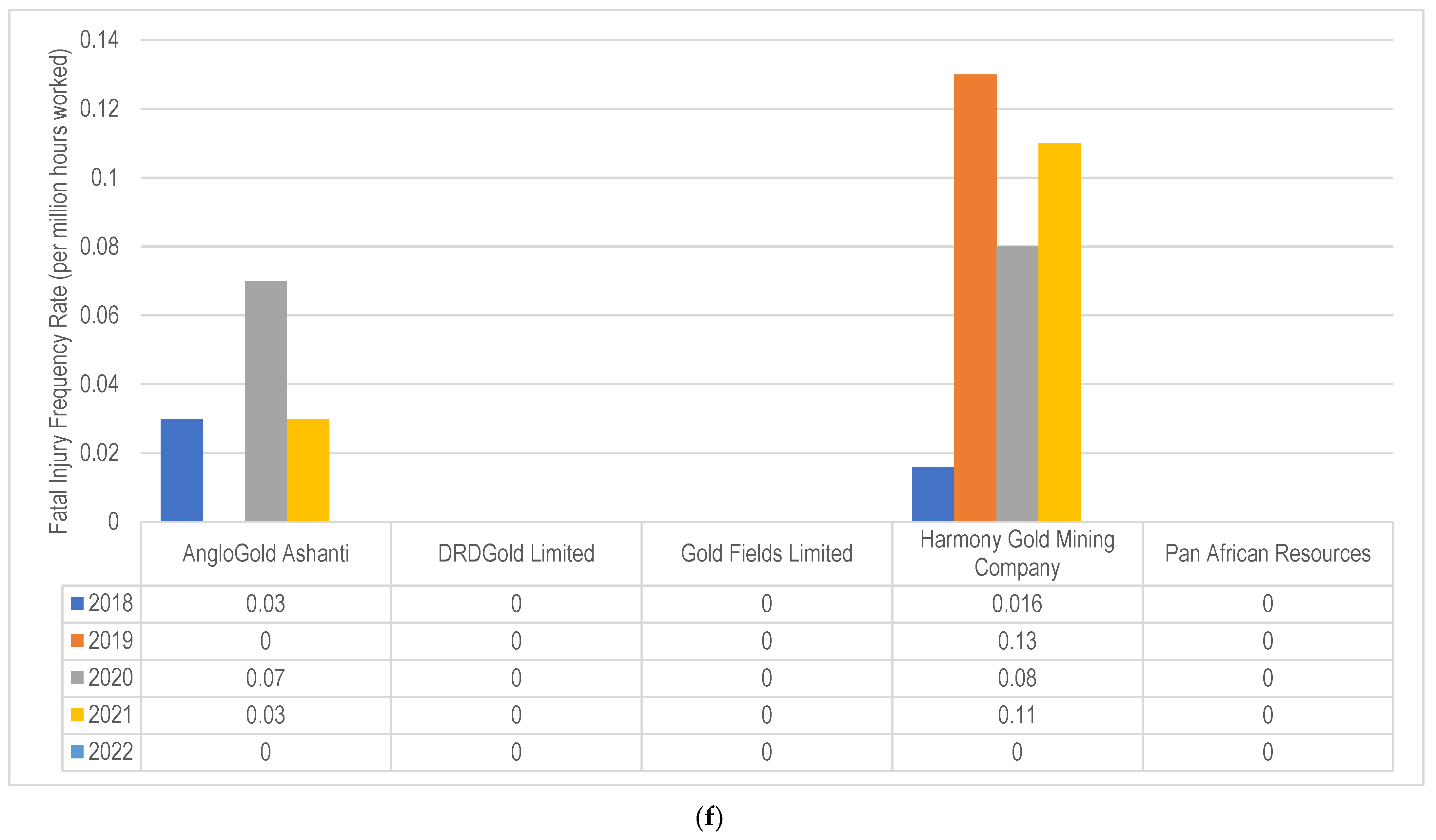

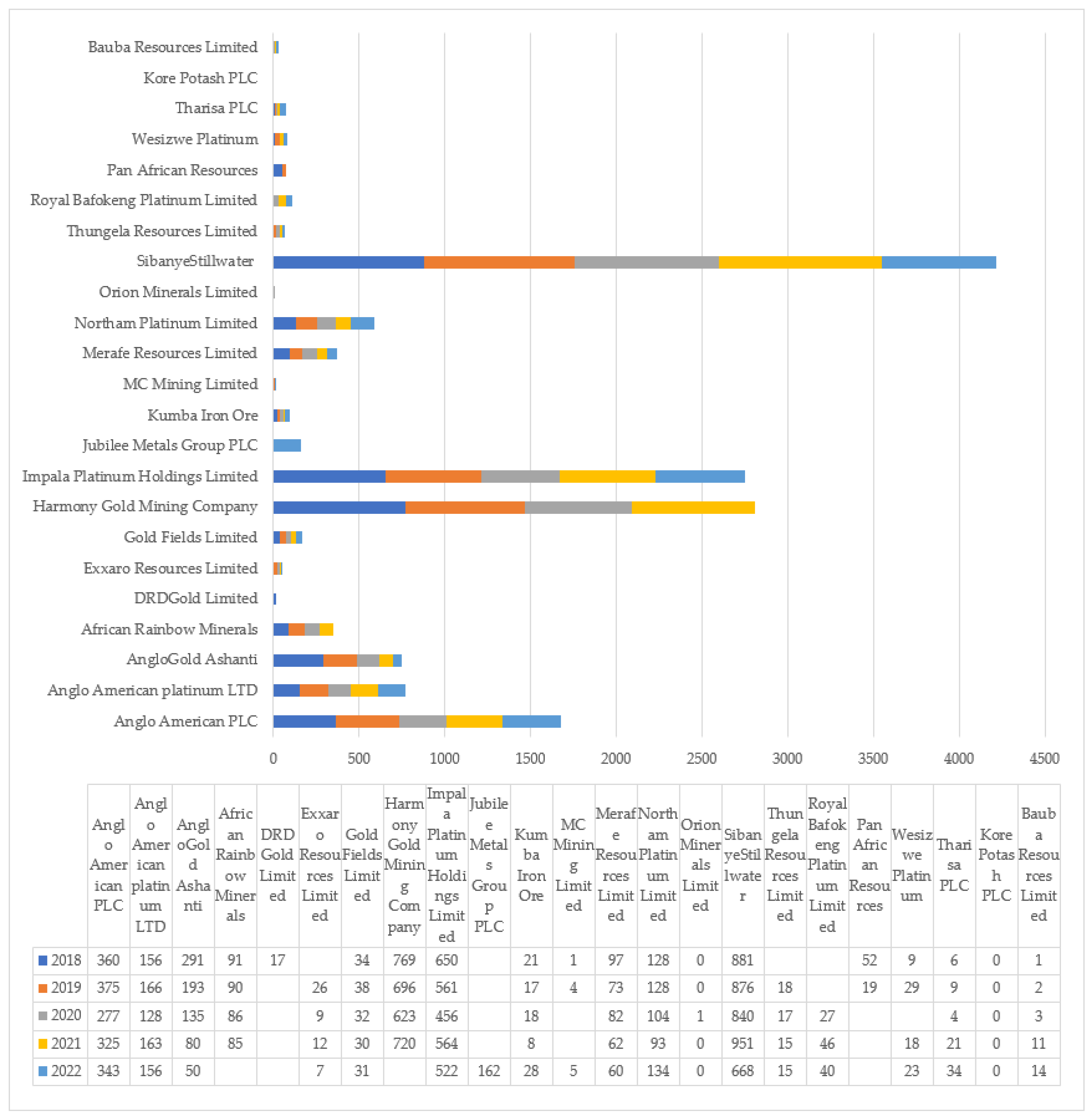

3.2.1. Fatalities

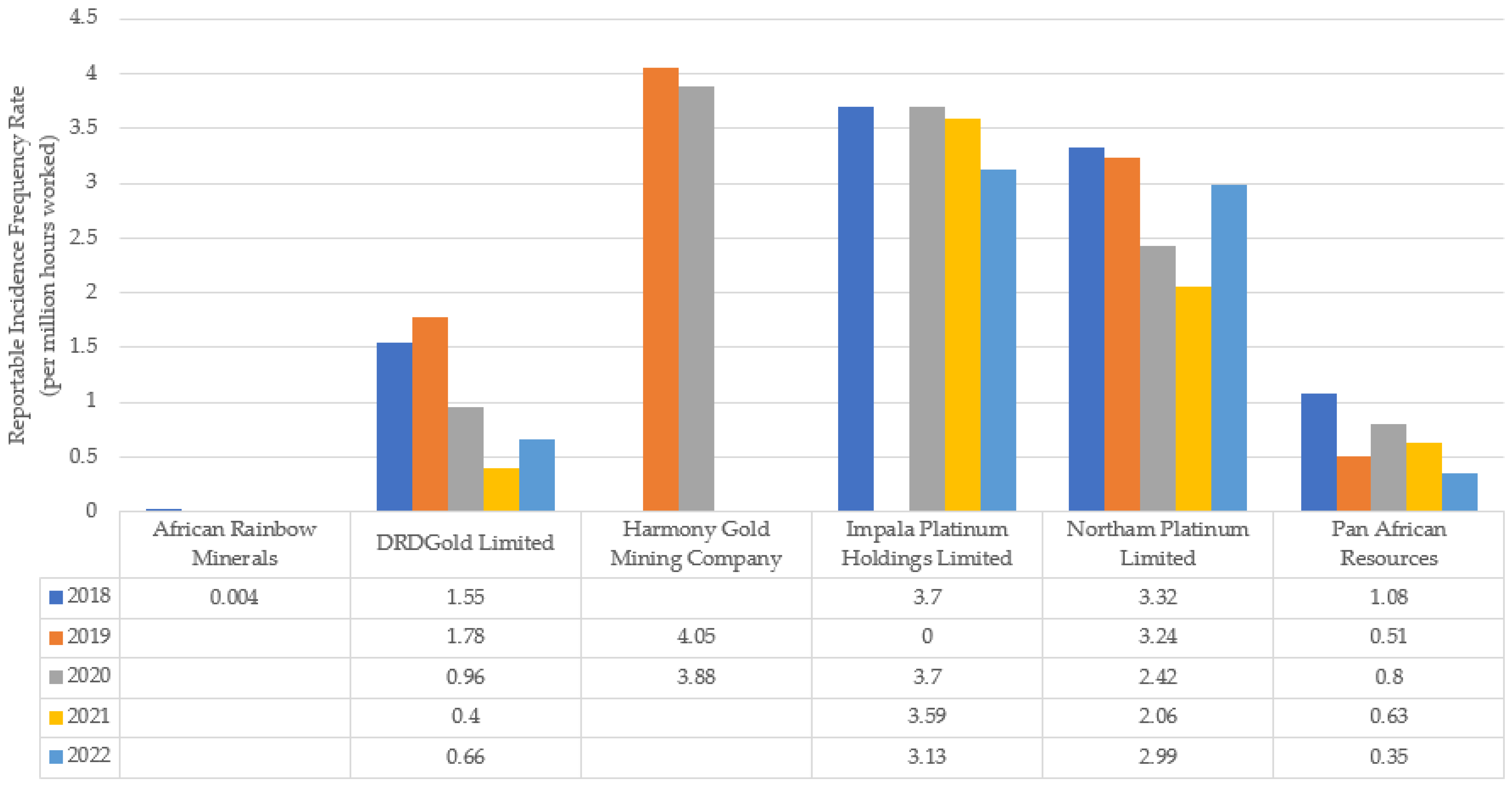

3.2.2. Reportable Incidence Frequency Rate (RIFR)

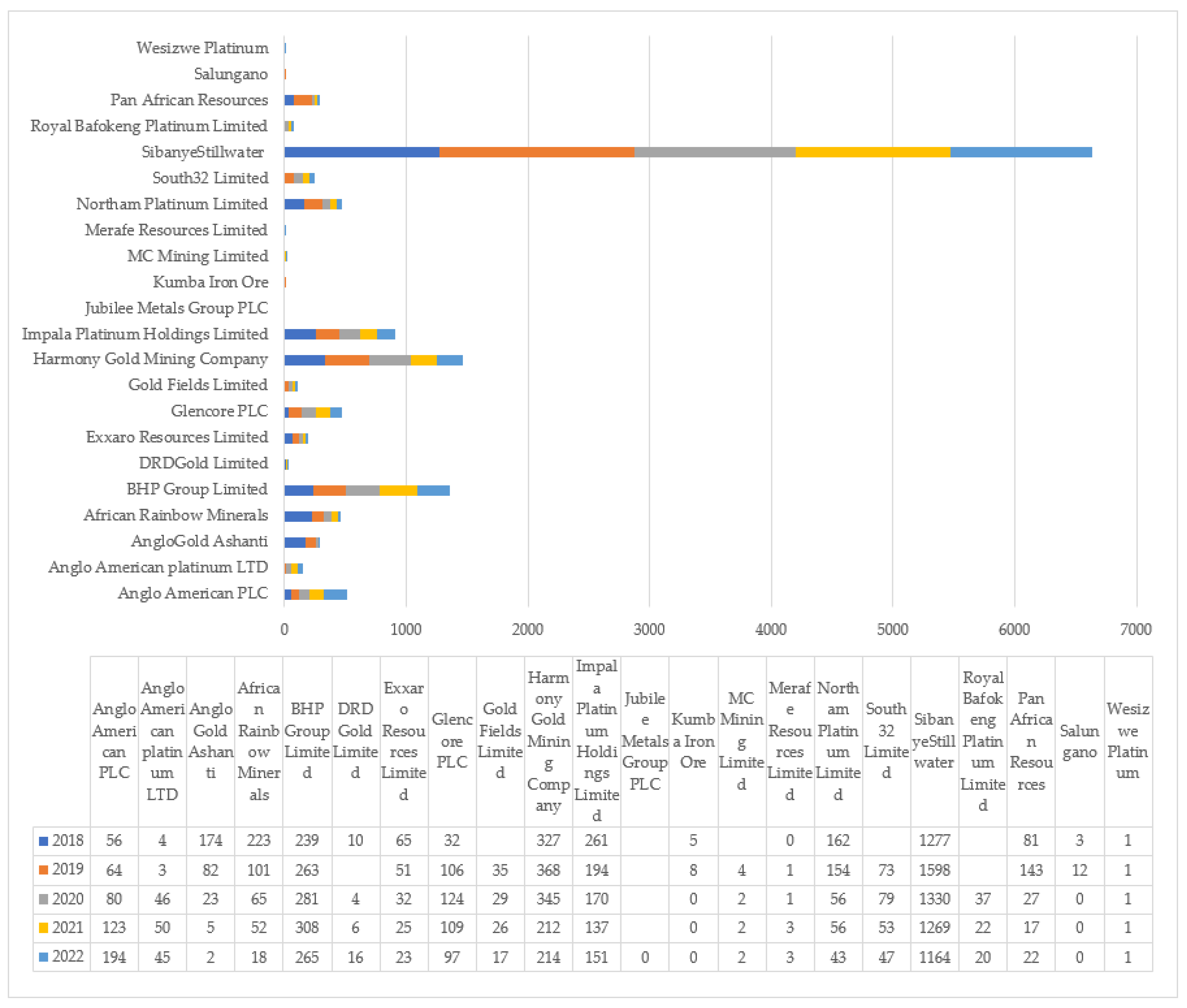

3.2.3. Lost Time Injury (LTI)

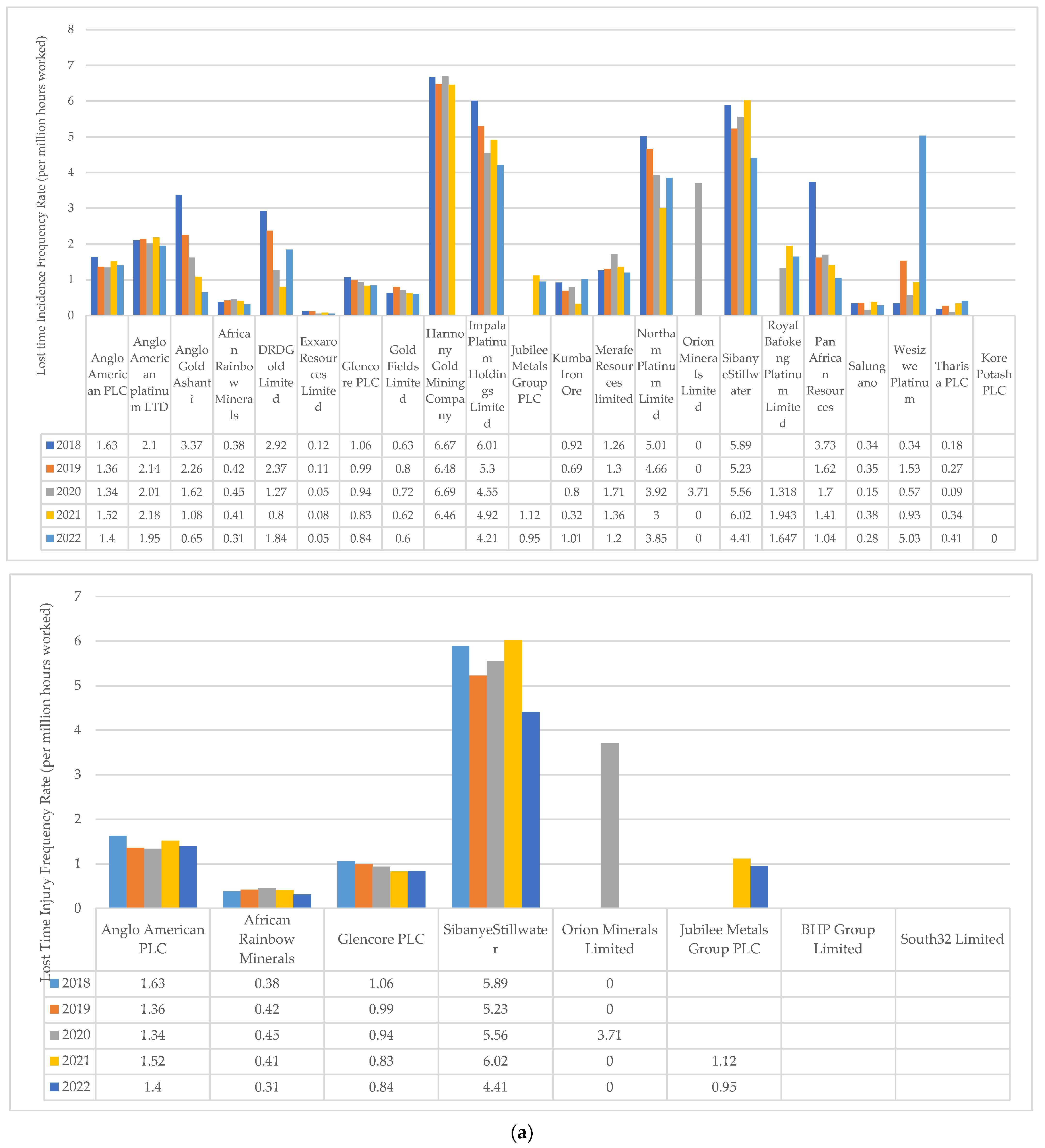

3.2.4. Lost Time Injury Frequency Rate (LTIFR)

3.2.5. Medical Treatment Cases (MTCs)

3.2.6. Total Recordable Case Frequency Rate (TRCFR) or Total Recordable Injury Frequency Rate (TRIFR)

3.2.7. Occupational Diseases

4. Discussion

4.1. Reporting Context and Format

4.2. Company OHS Performance

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

4.4. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, G.D. The global threats to workers’ health and safety on the job. Soc. Justice 2002, 29, 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, M. The toll from toil does matter: Occupational health and labour history. Labour Hist. 1997, 73, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. Occupational injury prevention. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 1992, 41, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zwi, A.; Fonn, S.; Steinberg, M. Occupational health and safety in South Africa: The perspectives of capital, state and unions. Soc. Sci. Med. 1988, 27, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinson, C. The malevolent workplace. Ambio 1975, 4, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Geldart, S. Health and Safety in Today’s Manufacturing Industry. 2014. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080965321008165?via%3Dihub (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Burdoft, A. Do costs matter in occupational health? Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 68, 707–708. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, W.G.; Henenberg, C. Social justice at the workplace: The political economy of occupational health and safety laws. Soc. Justice 1989, 16, 124–140. [Google Scholar]

- Health and Safety Executive. Defining Best Practice in Corporate Occupational Health and Safety Governance (Research Report 506). 2006. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/Research/rrhtm/rr506.htm (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Leger, J.P. Trends and causes of fatalities in South African mines. Saf. Sci. 1991, 14, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organisation. Occupational Safety and Health Statistics (OSH Database)—ILOSTAT. 2023. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/resources/concepts-and-definitions/description-occupational-safety-and-health-statistics/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Government of South Africa, Department of Mineral Resources and Energy. Mine Health and Safety Inspectorate—Annual Reports. 2024. Available online: https://www.dmr.gov.za/resources (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Gomes, R.F.S.; Lacerda, D.P.; Camanho, A.S.; Piran, F.A.S.; Silva, D.O. Measuring efficiency of safe work environment from the perspective of the decent work agenda. Saf. Sci. 2023, 167, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organisation. Decent Work Indicators: Guidelines for Producers and Users of Statistical and Legal Framework Indicators. 2013. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---integration/documents/publication/wcms_229374.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Government of South Africa, Department of Mineral Resources and Energy. Mineral Resources on Occupational Health and Safety Summit. 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.za/speeches/mine-health-and-safety-19-nov-2016-0000 (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- LaDou, J.; London, L.; Watterson, A. Occupational health: A world of false promises. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikhotso, O.; Morodi, T.J.; Masekameni, D.M. Occupational health hazards: Employer, employee, and labour union concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikhotso, O.; Morodi, T.J.; Masekameni, D.M. Occupational health and safety statistics as an indicator of worker physical health in South African industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health and Safety Executive. Directors’ Responsibilities for Health and Safety: The Findings of Two Peer Reviews of Published Research (Research Report 451). 2006. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/Research/rrpdf/rr451.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2018).

- Business & Human Rights Navigator. Occupational Safety and Health. 2023. Available online: https://bhr-navigator.unglobalcompact.org/issues/occupational-safety-and-health/ (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Tidwell, A. Ethics, safety and managers. Bus. Prof. Ethics J. 2000, 19, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization and United Nations Global Compact. Nine Business Practices for Improving Safety and Health through Supply Chains and Building a Culture of Prevention and Protection. 2021. Available online: https://ungc-communications-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/docs/publications/OSH%20Brief_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Lorenzo, O.; Esqueda, P.; Larson, J. Safety and ethics in the global workplace: Asymmetries in culture and infrastructure. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organisation. Decent Work: Report of the Director General to the 87th Session of the International Labour Conference. 1999. Available online: www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc87/rep-i.htm (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- International Labour Organization. ILO Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work. 2019. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/tokyo/WCMS_711674/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Rantanen, J.; Muchiri, F.; Lehtihen, S. Decent work, ILO’s response to the globalization of working life: Basic concepts and global implementation with special reference to occupational health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization. Convention No. 161 on Occupational Health Services. 1985. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:121200:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C161 (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- International Labour Organization. Recommendation No. 171 on Occupational Health Services. 1985. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:R171 (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Kubo, K. The effect of corporate governance on firms’ decent work policies in Japan. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 450–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, D. Decent work: Concept and indicators. Int. Labour Rev. 2003, 142, 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bescond, D.; Chataignier, A.; Mehran, F. Seven indicators to measure decent work: An international comparison. Int. Labour Rev. 2003, 142, 180–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Chan, K.L. The associations of decent work with wellbeing and career capabilities: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1068599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of South Africa. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (No. 108 of 1996). 1996. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/images/a108-96.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2017).

- Government of South Africa. Mine Health and Safety Act (No. 26 of 1996). 1996. Available online: http://www.dmr.gov.za/legislation/summary/30-mine-health-and-safety/530-mhs-act-29-of1996.html (accessed on 20 June 2017).

- Kanbur, R.; Ronconi, L. Enforcement matters: The effective regulation of labour. Int. Labour Rev. 2018, 157, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, T. Why wait till someone gets hurt? Safety injuctions. Soc. Lawyer 1988, 6, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Government of South Africa. Employment Equity Act (No. 55 of 1998). 1998. Available online: https://www.labour.gov.za/DocumentCenter/Acts/Employment%20Equity/Act%20-%20Employment%20Equity%201998.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Government of South Africa. Basic Conditions of Employment Act (No. 75 of 1997). 1997. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a75-97.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Government of South Africa. Labour Relations Act and Amendments (No. 66 of 1995). 1995. Available online: http://www.labour.gov/DOL/downloads/legislation/acts/labour-relations/labour-relation-act (accessed on 20 June 2016).

- Government of South Africa. Companies Act, 2008 (No. 71 of 2008). 2009. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/321214210.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Johannesburg Stock Exchange. JSE Sustainability Recommended Disclosures and Metrics. 2022. Available online: https://www.jse.co.za/sites/default/files/media/documents/JSE%20Sustainability%20Disclosure%20Guidance%20June%202022.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- International Council on Mining & Metals. Overview of Leading Indicators for Occupational Health and Safety in Mining. 2022. Available online: https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/health-and-safety/2012/guidance_indicators-ohs.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Health and Safety Executive. Successful Health and Safety Management HSG65. 1997. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/priced/hsg65.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Moher, D.S.L.; Liberti, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Prefered reporting items for systemic review and meta-analysis: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WordItOut. Make a Word Cloud. 2023. Available online: https://worditout.com/word-cloud/create (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Mathews, D.; Franzen-Castle, L.; Colby, S.; Kattelmann, K.; Olfert, M.; White, A. Use of Word Clouds as a novel approach for analysis and presentation of qualitative data for program evaluation. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safework Australia. Lost Time Injury Frequency Rates. 2024. Available online: https://data.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/interactive-data/lost-time-injury-frequency-rates (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Government of South Africa. Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (No. 130 of 1993). 2003. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act130of1993.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Rikhotso, O.; Morodi, T.J.; Masekameni, D.M. The extent of occupational health hazard impact on workers: Documentary evidence from national occupational disease statistics and selected South African companies’ voluntary corporate social responsibility disclosures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Health. Key Performance Indicators. 2016. Available online: https://oshwiki.osha.europa.eu/en/themes/key-performance-indicators (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Standard Interpretations—Clarification How the Formula Is Used by OSHA to Calculate Incident Rates. 2016. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/2016-08-23 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Safework Australia. Measuring and Reporting on Work Health and Safety. 2017. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1802/measuring-and-reporting-on-work-health-and-safety.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- SANS 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. Standards South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018.

- International Council on Mining & Metals. Safety Performance Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/health-and-safety/2023/benchmarking-safety-data-2022.pdf?cb=60809 (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Tshiamiso Trust. Home. 2024. Available online: https://www.tshiamisotrust.com/?nopopup=true (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Balderson, D. Safety defined. A means to provide a safe work environment. Prof. Saf. 2016, 61, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ivensky, V. Safety expectations. Finding a common denominator. Prof. Saf. 2016, 61, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Health and Safety Executive. Trends and Context to Rates of Workplace Injury (Research Report 386). 2005. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/Research/rrhtm/rr386.htm (accessed on 6 November 2018).

- Wilburn, S. Health & safety: Take care of yourself. Am. J. Nurs. 2001, 101, 88. [Google Scholar]

| Company Name (City, Country) | Report Title | Supplementary Databook | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Report/ Integrated Annual Report | Sustainability Report | Environmental, Social and Governance Report | ||

| Anglo American PLC (London, UK) | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| Anglo American platinum LTD (Rosebank, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| AngloGold Ashanti (Denver, USA) | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| African Rainbow Minerals (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| BHP Group Limited (Melbourne, Australia) | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| DRDGold Limited (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Exxaro Resources Limited (Pretoria, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Glencore PLC (Baar, Switzerland) | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| Gold Fields Limited (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| Harmony Gold Mining Company (Queensland, Australia) | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ |

| Impala Platinum Holdings Limited (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - |

| Jubilee Metals Group PLC (Pretoria, South Africa) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Kumba Iron Ore (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| MC Mining Limited (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Merafe Resources Limited (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Northam Platinum Limited (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| Orion Minerals Limited (Melbourne, Australia) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| South32 Limited (Perth, Australia) | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| Thungela Resources Limited (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | - | ✔ | - |

| SibanyeStillwater (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Royal Bafokeng Platinum Limited (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Pan African Resources (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - |

| Salungano (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Wesizwe Platinum (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Tharisa PLC (Paphos, Cyprus) | ✔ | - | ✔ | - |

| Gemfields Group Limited (London, UK) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Kore Potash PLC (London, UK) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Southern Palladium Limited (Sydney, Australia) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Chrometco Limited (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Europa Metals Limited (Perth, Australia) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Randgold and Exploration Company (Johannesburg, South Africa) | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Bauba Resources Limited (Pretoria, South Africa) | ✔ | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rikhotso, O.; Shabangu, M.; Havenga, Y. The Illusive Pipedream of Zero Harm: A South African Mining Industry Perspective. Safety 2024, 10, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety10030065

Rikhotso O, Shabangu M, Havenga Y. The Illusive Pipedream of Zero Harm: A South African Mining Industry Perspective. Safety. 2024; 10(3):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety10030065

Chicago/Turabian StyleRikhotso, Oscar, Mesala Shabangu, and Yolanda Havenga. 2024. "The Illusive Pipedream of Zero Harm: A South African Mining Industry Perspective" Safety 10, no. 3: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety10030065

APA StyleRikhotso, O., Shabangu, M., & Havenga, Y. (2024). The Illusive Pipedream of Zero Harm: A South African Mining Industry Perspective. Safety, 10(3), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety10030065