Empirical Evaluation of UNet for Segmentation of Applicable Surfaces for Seismic Sensor Installation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology of the Research

- The following spectral band combinations of Sentinel-2 multispectral bands: RGB (3 bands with 10 m/pix spatial resolution), RGB+NIR (4 bands with 10 m/pix spatial resolution), all bands with 10 and 20 m/pix spatial resolution (10 bands), and full spectrum of Sentinel-2 (13 bands with 10, 20, and 60 m/pix resolution).

- Two values of the input convolutional layer strides (stride = 1 and stride = 2) in order to evaluate a technique for small object segmentation improvement, that will be thoroughly described in Section 3.6: “Improving small object segmentation”.

- The impact of a pretrained encoder used for feature extraction. In order to do this, we consider all possible band and stride combinations and search for the best encoder for each of the surface classes according to each metric.

- The impact of different multispectral band combinations. In order to do this, we compare results of the corresponding classes for combinations of encoders and input the convolutional layer stride. First, we compare results with each encoder, then we summarize the results of the considered encoders.

3.2. Dataset Description

3.3. UNet Encoder–Decoder Architecture

3.4. Description of Encoders

3.4.1. EfficientNetB2

3.4.2. CSPDarkNet53

3.4.3. MAxViT

3.5. Input Layer Adaptation

3.6. Improving Small Object Segmentation

3.7. Experimental Setup

3.8. Assessment Metrics

- Intersection over Union (IoU):

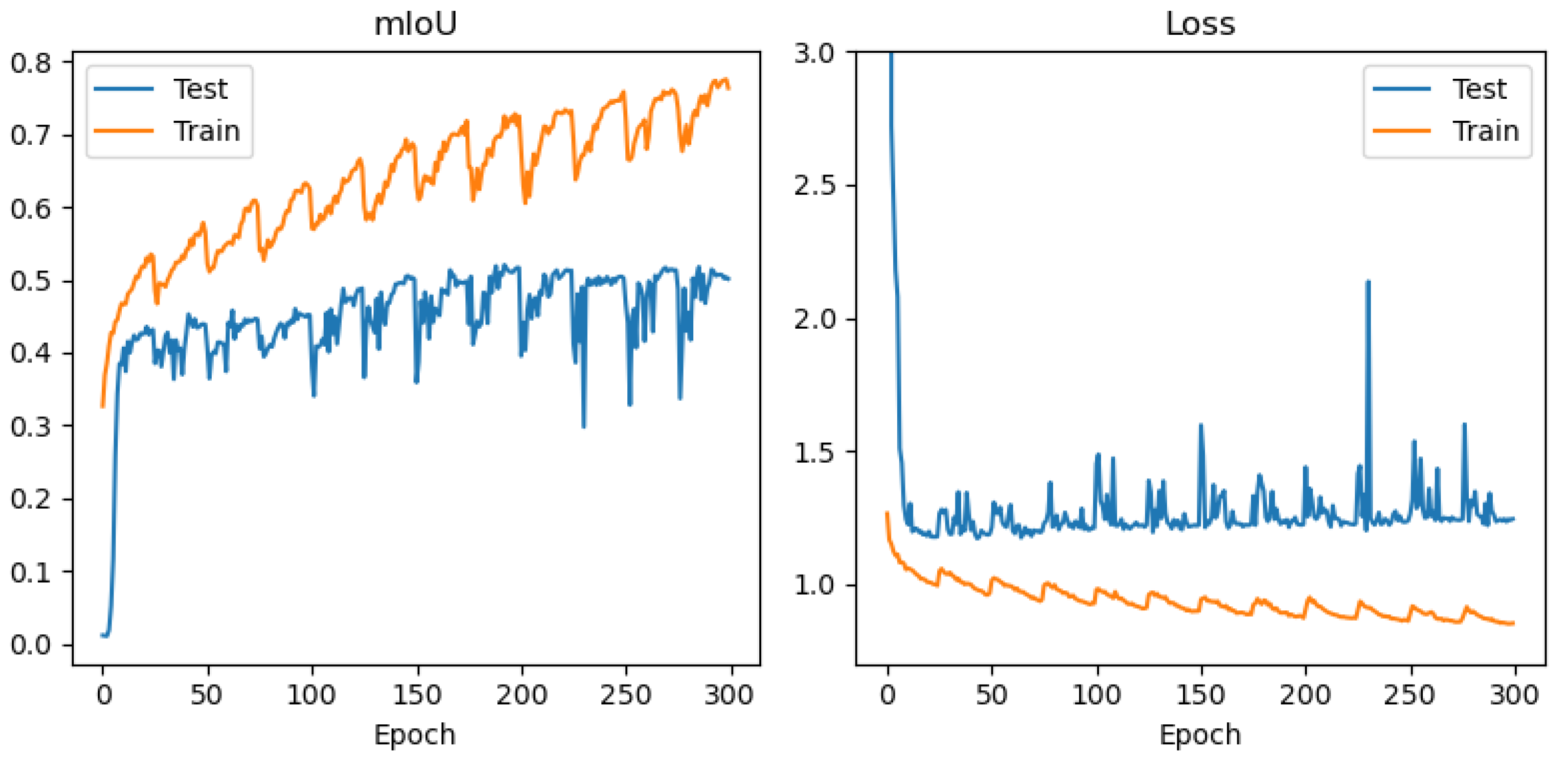

4. Results

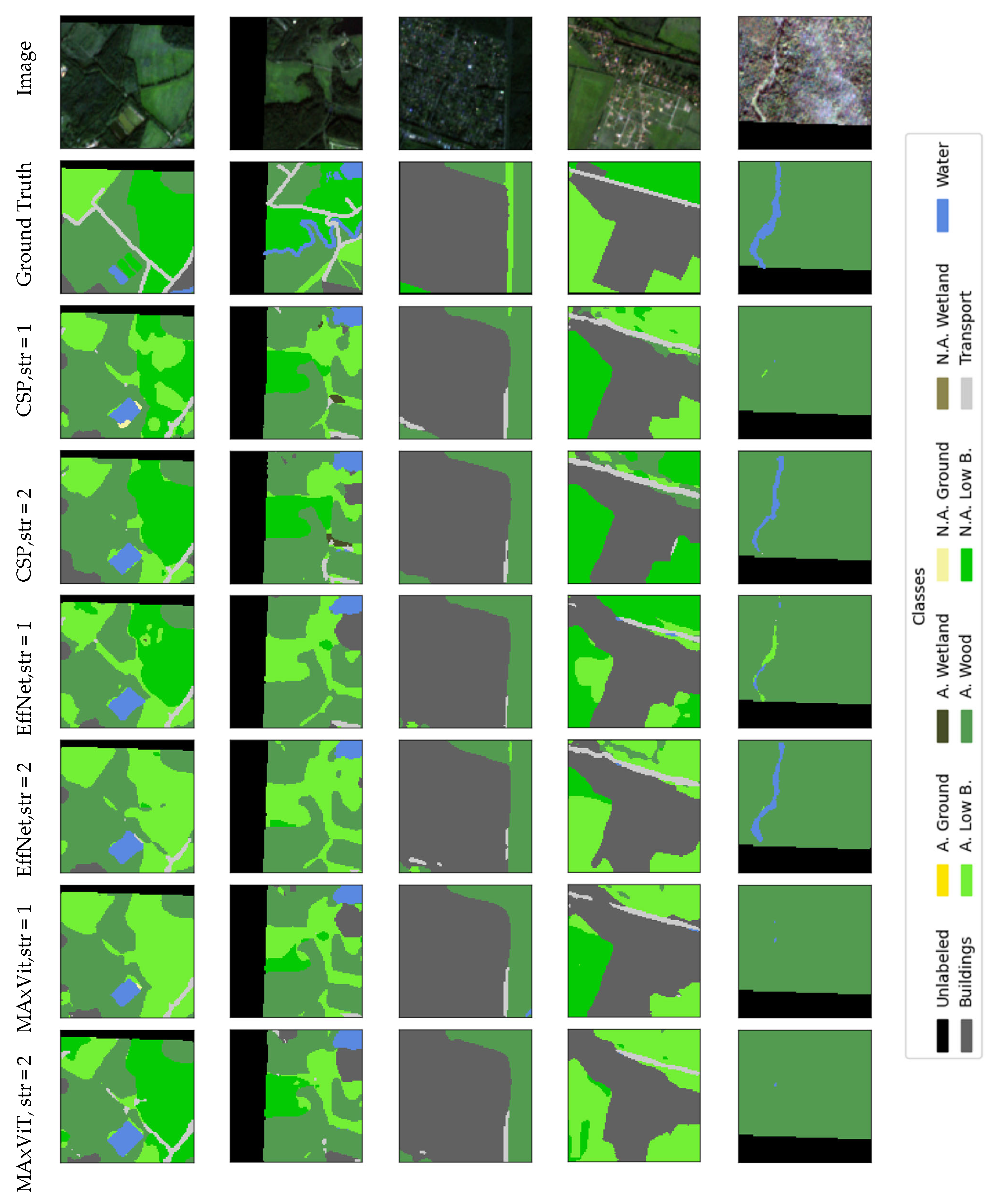

Visualization

5. Discussion

5.1. Encoder Impact

5.2. Spectral Band Impact

5.3. Input Convolution Stride Impact

5.4. Misclassification Analysis

5.5. Limitations

5.6. Generalizations of the Results

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

| L2A | Level-2A (Sentinel-2 atmospheric correction level) |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue (spectral bands) |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| m/pix | Meters per pixel |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| MAxViT | Multi-Axis Vision Transformer |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| SE | Squeeze-and-Excitation (module) |

| NAS | Neural Architecture Search |

| SMP | Segmentation Models Pytorch (library) |

| EfficientNetB2 | EfficientNet Backbone, version B2 |

| CSPNet | Cross-Stage Partial Network |

| CSPDarkNet53 | CSP-based DarkNet-53 backbone |

| VGGNet-16 | Visual Geometry Group Network, 16 layers |

| UNetFormer | UNet-like Transformer model |

| U-TAE | Time-Attention Encoder (temporal segmentation model) |

| Sen4x | Sentinel-2 Super-Resolution Model |

| Swin2SR | SwinV2 Transformer for Super-Resolution |

| MSNet | Multispectral Semantic Segmentation Network |

| PSNet | Multispectral Universal Segmentation Network |

| SGDR | Stochastic Gradient Descent with Warm Restarts |

| Adam | Adaptive Moment Estimation (optimizer) |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| CE | Cross-Entropy (loss) |

| FN | False Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| TP | True Positive |

| FLAIR | French Land-cover from Aerial Imagery Repository |

| PEER | Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center |

| QGIS | Quantum Geographic Information System |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| A. | Applicable |

| N.A. | Non-Applicable |

References

- Makama, A.; Kuladinithi, K.; Timm-Giel, A. Wireless geophone networks for land seismic data acquisition: A survey, tutorial and performance evaluation. Sensors 2021, 21, 5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudero, S.; Costanzo, A.; D’Alessandro, A. Urban Seismic Networks: A Worldwide Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Song, J.; Mo, W.; Dong, K.; Wu, X.; Peng, J.; Jin, F. A seismic data acquisition system based on wireless network transmission. Sensors 2021, 21, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, H.; Gaya, S.; Alamoudi, A.; Alshehri, F.M.; Al-Suhaimi, A.; Alsulaim, N.; Al Naser, A.M.; Jamal Eddin, M.; Alqahtani, A.M.; Prieto Rojas, J.; et al. Wireless geophone sensing system for real-time seismic data acquisition. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 81116–81128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzdiaev, M.Y.; Astapova, M.A.; Ronzhin, A.L.; Saveliev, A.I.; Agafonov, V.M.; Erokhin, G.N.; Nenashev, V.A. A methodology for automated labelling a geospatial image dataset of applicable locations for installing a wireless nodal seismic system. Comput. Opt. 2025, 49, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajedi, S.O.; Liang, X. Optimal Sensor Placement for Seismic Damage Diagnosis Leveraging Thompson Sampling and Deep Generative Bayesian Statistics. In Proceedings of the 12th U.S. National Conference on Earthquake Engineering (12NCEE), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 27 June–1 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Lin, R.; Sacchi, M.D. Optimal Seismic Sensor Placement Based on Reinforcement Learning Approach: An Example of OBN Acquisition Design. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Krestovnikov, K. Aerial Manipulation System for Automated Installation of Seismic Activity Sensors. In Interactive Collaborative Robotics; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14983, pp. 368–380. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Ma, L.; He, G.; Johnson, B.A.; Yan, Z.; Chang, M.; Liang, Y. Transformers for Remote Sensing: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clabaut, É.; Foucher, S.; Bouroubi, Y.; Germain, M. Synthetic Data for Sentinel-2 Semantic Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B. Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Image Based on Convolutional Neural Network and Mask Generation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 2472726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilay, M.Y.; Taye, G.D. Semantic segmentation model for land cover classification from satellite images in Gambella National Park, Ethiopia. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, G.; Chen, W.; Chen, R.; Gao, D.; Wu, Y. Semantic Segmentation of China’s Coastal Wetlands Based on Sentinel-2 and SegFormer. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yifter, T.; Razoumny, Y.; Lobanov, V. Deep transfer learning of satellite imagery for land use and land cover classification. Inform. Autom. 2022, 21, 963–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukač, N.; Kavran, D.; Ovčjak, M.F.; Bizjak, M. Genetic Algorithm for Optimizing Meteorological Sensors Placement Using Airborne LiDAR Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 24th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Informatics (CINTI), Budapest, Hungary, 19–21 November 2024; pp. 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sharafkhani, F.; Corns, S.; Seo, B.C. Graph-Based Preprocessing and Hierarchical Clustering for Optimal State-Wide Stream Sensor Placement in Missouri. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 388, 125963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, C.; Gioia, A.; Iacobellis, V.; Manfreda, S. Detection of Surface Water and Floods with Multispectral Satellites. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9351, pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Ventura, C.E.; Li, T. Sensor Placement and Seismic Response Reconstruction for Structural Health Monitoring Using a Deep Neural Network. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 4513–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research (PEER) Center. PEER NGA-West2 Database. Available online: https://ngawest2.berkeley.edu/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Francini, M.; Salvo, C.; Viscomi, A.; Vitale, A. A Deep Learning-Based Method for the Semi-Automatic Identification of Built-Up Areas within Risk Zones Using Aerial Imagery and Multi-Source GIS Data: An Application for Landslide Risk. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semantic Segmentation Dataset. Available online: https://humansintheloop.org/semantic-segmentation-dataset/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Nagel, A.M.; Webster, A.; Henry, C.; Storie, C.; Sanchez, I.S.M.; Tsui, O.; Dean, A. Automated Linear Disturbance Mapping via Semantic Segmentation of Sentinel-2 Imagery. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.12817. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Hong, X.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Q. Infrared Image Segmentation for Photovoltaic Panels Based on Res-UNet. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision, PRCV 2019, Xi’an, China, 8–11 November 2019; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11858, pp. 611–622. [Google Scholar]

- Jindgar, K.; Lindsay, G.W. Improving Satellite Imagery Segmentation Using Multiple Sentinel-2 Revisits. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.17363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnanto, A.; Le, S.; Mueller, S.; Leitner, A.; Schindler, K.; Iddawela, Y.; Riffler, M. Beyond Pretty Pictures: Combined Single-and Multi-Image Super-Resolution for Sentinel-2 Images. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.24799. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, M.V.; Choi, U.J.; Burchi, M.; Timofte, R. Swin2SR: Swinv2 Transformer for Compressed Image Super-Resolution and Restoration. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022 Workshops, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13807, pp. 669–687. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Loy, C.C. ESRGAN: Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018 Workshops, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11133, pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrovski, I.; Spasev, V.; Kitanovski, I. Deep Multimodal Fusion for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Earth Observation Data. In Proceedings of the ICT Innovations 2024, Ohrid, North Macedonia, 28–30 September 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 106–120. [Google Scholar]

- FLAIR #2 Dataset. Available online: https://github.com/IGNF/FLAIR-2 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, C.; Fang, S.; Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Atkinson, P.M. UNetFormer: A UNet-Like Transformer for Efficient Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Urban Scene Imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnot, V.S.F.; Landrieu, L. Time-Space Trade-off in Satellite Image Time Series Classification with Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2021), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 4872–4881. [Google Scholar]

- Favorskaya, M.; Pakhira, A. Restoration of Semantic-Based Super-Resolution Aerial Images. Inform. Autom. 2024, 23, 1047–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, C.; Yu, J.; Ge, D.; Yang, L.; Xi, L.; Pang, Y.; Wen, Y. TransLandSeg: A Transfer Learning Approach for Landslide Semantic Segmentation Based on Vision Foundation Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.10127. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Girshick, R. Segment Anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Bijie Landslide Dataset. Available online: https://gpcv.whu.edu.cn/data/Bijie_pages.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Soni, P.K.; Rajpal, N.; Mehta, R.; Mishra, V.K. Urban Land Cover and Land Use Classification Using Multispectral Sentinel-2 Imagery. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 36853–36867. [Google Scholar]

- Gannod, M.; Masto, N.; Owusu, C.; Brown, K.; Blake-Bradshaw, A.; Feddersen, J.; Cohen, B. Semantic Segmentation with Multispectral Satellite Images of Waterfowl Habitat. In Proceedings of the 36th International FLAIRS Conference (FLAIRS-36), Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 14–17 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, C.; Meng, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, B.; Hu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. MSNet: Multispectral Semantic Segmentation Network for Remote Sensing Images. GIScience Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1177–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Kotaridis, I.; Lazaridou, M. Semantic Segmentation Using a UNet Architecture on Sentinel-2 Data. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 43, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dabbagh, A.M.; Ilyas, M. Uni-Temporal Sentinel-2 Imagery for Wildfire Detection Using Deep Learning Semantic Segmentation Models. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2196370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, T.; Tian, C.; Dong, W. PSNet: A Universal Algorithm for Multispectral Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, M.; Martinis, S.; Kiefl, R.; Gstaiger, V. Semantic Segmentation of Water Bodies in Very High-Resolution Satellite and Aerial Images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 287, 113452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, R.; Puissant, A.; Weber, J.; Idoumghar, L.; Forestier, G. Multimodal and Multitemporal Land Use/Land Cover Semantic Segmentation on Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Imagery: An Application on a Multisenge Dataset. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favorskaya, M.; Nishchhal, N. Verification of Marine Oil Spills Using Aerial Images Based on Deep Learning Methods. Inform. Autom. 2022, 21, 937–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtik, P.; Molek, V.; Hula, J.; Vajgl, M.; Vlasanek, P.; Nejezchleba, T. Poly-YOLO: Higher Speed, More Precise Detection and Instance Segmentation for YOLOv3. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.13243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M.; Wu, Y.H.; Chen, P.Y.; Hsieh, J.W.; Yeh, I.H. CSPNet: A New Backbone That Can Enhance Learning Capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 390–391. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Z.; Talebi, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, F.; Milanfar, P.; Bovik, A.; Li, Y. MaxViT: Multi-Axis Vision Transformer. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13684, pp. 459–479. [Google Scholar]

- QGIS Geographic Information System. Available online: https://qgis.org/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Google Earth Pro. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Retromap—Historical Maps Online. Available online: https://retromap.ru/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11045, pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Rethinking Semantic Segmentation from a Sequence-to-Sequence Perspective with Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 6881–6890. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12346, pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11211, pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Segmentation Models Pytorch Library. Available online: https://github.com/qubvel-org/segmentation_models.pytorch (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Li, F.F. ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Caballero, J.; Huszár, F.; Totz, J.; Aitken, A.P.; Bishop, R.; Wang, Z. Real-Time Single Image and Video Super-Resolution Using an Efficient Sub-Pixel Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1874–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, P.; Uszkoreit, J.; Vaswani, A. Self-Attention with Relative Position Representations. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.02155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. SGDR: Stochastic Gradient Descent with Warm Restarts. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.03983. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-Net: Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Volumetric Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X.; Kolesnikov, A.; Houlsby, N.; Beyer, L. Scaling Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 12104–12113. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, S.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Kouno, N.; Takasawa, K.; Ishizu, K.; Akagi, Y.; Hamamoto, R. Comparison of Vision Transformers and Convolutional Neural Networks in Medical Image Analysis: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2024, 48, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Surface Class | Number of Pixels, M | Area Portion, % | Area Portion Train, % | Area Portion Test, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buildings | 2.75 | 12.9 | 13.1 | 12.6 |

| Transport | 0.54 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.3 |

| Water | 1.07 | 5.0 | 5.9 | 5.4 |

| Non-applicable Ground | 0.14 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Non-applicable Low Bushes | 1.95 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 9.6 |

| Non-applicable Wetlands | 0.13 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Applicable Ground | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Applicable Low Bushes | 1.91 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 8.7 |

| Applicable Wetlands | 1.61 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.5 |

| Applicable Wood | 10.23 | 48.2 | 48.2 | 48.0 |

| Unlabeled Area | 0.87 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 4.6 |

| Enc | Sp | Stride | Mean | N.A. Mean | A. Mean | Build. | Transp. | Water | N.A. Gnd. | N.A. Low B. | N.A. Wtl. | A. Gnd. | A. Low B. | A. Wtl | A. Wood | Ulbl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSP | RGB | 1 | 0.513 | 0.474 | 0.497 | 0.722 | 0.353 | 0.76 | 0.038 | 0.459 | 0.511 | 0.529 | 0.234 | 0.434 | 0.79 | 0.817 |

| 2 | 0.501 | 0.486 | 0.446 | 0.719 | 0.334 | 0.761 | 0.068 | 0.489 | 0.543 | 0.392 | 0.204 | 0.406 | 0.781 | 0.817 | ||

| 10 m | 1 | 0.528 | 0.509 | 0.484 | 0.726 | 0.374 | 0.86 | 0.038 | 0.479 | 0.578 | 0.46 | 0.234 | 0.443 | 0.799 | 0.817 | |

| 2 | 0.534 | 0.528 | 0.471 | 0.716 | 0.358 | 0.857 | 0.055 | 0.506 | 0.678 | 0.415 | 0.242 | 0.431 | 0.798 | 0.817 | ||

| 10–20 m | 1 | 0.513 | 0.488 | 0.474 | 0.717 | 0.365 | 0.823 | 0.052 | 0.47 | 0.5 | 0.431 | 0.247 | 0.421 | 0.798 | 0.817 | |

| 2 | 0.503 | 0.484 | 0.452 | 0.721 | 0.352 | 0.817 | 0.029 | 0.483 | 0.504 | 0.397 | 0.188 | 0.429 | 0.795 | 0.817 | ||

| All | 1 | 0.529 | 0.51 | 0.486 | 0.729 | 0.368 | 0.831 | 0.062 | 0.495 | 0.576 | 0.454 | 0.242 | 0.451 | 0.797 | 0.817 | |

| 2 | 0.507 | 0.482 | 0.467 | 0.686 | 0.35 | 0.764 | 0.043 | 0.456 | 0.596 | 0.445 | 0.214 | 0.427 | 0.782 | 0.817 | ||

| EffNet | RGB | 1 | 0.499 | 0.472 | 0.462 | 0.71 | 0.355 | 0.742 | 0.017 | 0.363 | 0.644 | 0.424 | 0.232 | 0.408 | 0.782 | 0.817 |

| 2 | 0.494 | 0.475 | 0.442 | 0.716 | 0.314 | 0.752 | 0.012 | 0.444 | 0.609 | 0.414 | 0.187 | 0.373 | 0.792 | 0.816 | ||

| 10 m | 1 | 0.519 | 0.504 | 0.468 | 0.713 | 0.336 | 0.872 | 0.02 | 0.436 | 0.648 | 0.448 | 0.233 | 0.402 | 0.789 | 0.816 | |

| 2 | 0.513 | 0.498 | 0.461 | 0.72 | 0.339 | 0.85 | 0.008 | 0.435 | 0.633 | 0.417 | 0.226 | 0.411 | 0.79 | 0.816 | ||

| 10–20 m | 1 | 0.52 | 0.493 | 0.487 | 0.729 | 0.36 | 0.874 | 0.031 | 0.478 | 0.489 | 0.483 | 0.228 | 0.436 | 0.8 | 0.816 | |

| 2 | 0.495 | 0.461 | 0.467 | 0.715 | 0.315 | 0.842 | 0.015 | 0.454 | 0.426 | 0.415 | 0.246 | 0.418 | 0.789 | 0.816 | ||

| All | 1 | 0.512 | 0.491 | 0.466 | 0.73 | 0.354 | 0.844 | 0.053 | 0.469 | 0.495 | 0.384 | 0.245 | 0.438 | 0.799 | 0.817 | |

| 2 | 0.502 | 0.477 | 0.462 | 0.72 | 0.328 | 0.813 | 0.027 | 0.485 | 0.488 | 0.381 | 0.229 | 0.446 | 0.792 | 0.817 | ||

| MaxViT | RGB | 1 | 0.492 | 0.455 | 0.468 | 0.726 | 0.33 | 0.74 | 0.029 | 0.415 | 0.489 | 0.447 | 0.194 | 0.432 | 0.799 | 0.816 |

| 2 | 0.493 | 0.467 | 0.453 | 0.729 | 0.333 | 0.755 | 0.026 | 0.422 | 0.535 | 0.417 | 0.214 | 0.385 | 0.795 | 0.816 | ||

| 10 | 1 | 0.509 | 0.492 | 0.459 | 0.727 | 0.361 | 0.856 | 0.045 | 0.432 | 0.528 | 0.372 | 0.217 | 0.444 | 0.802 | 0.817 | |

| 2 | 0.517 | 0.505 | 0.46 | 0.715 | 0.346 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.455 | 0.594 | 0.385 | 0.209 | 0.443 | 0.804 | 0.816 | ||

| 10–20 m | 1 | 0.502 | 0.477 | 0.464 | 0.722 | 0.327 | 0.86 | 0.034 | 0.437 | 0.482 | 0.465 | 0.221 | 0.383 | 0.79 | 0.798 | |

| 2 | 0.509 | 0.487 | 0.466 | 0.717 | 0.342 | 0.862 | 0.003 | 0.449 | 0.547 | 0.414 | 0.22 | 0.435 | 0.797 | 0.817 | ||

| All | 1 | 0.514 | 0.49 | 0.476 | 0.732 | 0.335 | 0.874 | 0.006 | 0.457 | 0.534 | 0.405 | 0.225 | 0.468 | 0.804 | 0.817 | |

| 2 | 0.508 | 0.491 | 0.456 | 0.72 | 0.334 | 0.856 | 0.025 | 0.462 | 0.55 | 0.343 | 0.212 | 0.465 | 0.802 | 0.817 |

| Enc | Sp | Stride | Mean | N.A. Mean | A. Mean | Build. | Transp. | Water | N.A. Gnd. | N.A. Low B. | N.A. Wtl. | A. Gnd. | A. Low B. | A. Wtl | A. Wood | Ulbl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSP | RGB | 1 | 0.679 | 0.65 | 0.647 | 0.839 | 0.573 | 0.936 | 0.132 | 0.662 | 0.755 | 0.748 | 0.38 | 0.615 | 0.846 | 0.982 |

| 2 | 0.672 | 0.664 | 0.607 | 0.848 | 0.565 | 0.885 | 0.186 | 0.658 | 0.843 | 0.674 | 0.361 | 0.54 | 0.851 | 0.983 | ||

| 10 m | 1 | 0.697 | 0.683 | 0.646 | 0.86 | 0.594 | 0.953 | 0.179 | 0.664 | 0.847 | 0.702 | 0.402 | 0.635 | 0.845 | 0.983 | |

| 2 | 0.716 | 0.704 | 0.666 | 0.833 | 0.557 | 0.939 | 0.382 | 0.69 | 0.824 | 0.721 | 0.426 | 0.674 | 0.841 | 0.983 | ||

| 10–20 m | 1 | 0.692 | 0.66 | 0.666 | 0.82 | 0.577 | 0.924 | 0.196 | 0.69 | 0.755 | 0.797 | 0.389 | 0.622 | 0.855 | 0.982 | |

| 2 | 0.674 | 0.637 | 0.653 | 0.822 | 0.57 | 0.898 | 0.105 | 0.631 | 0.795 | 0.752 | 0.379 | 0.636 | 0.847 | 0.982 | ||

| All | 1 | 0.686 | 0.664 | 0.645 | 0.851 | 0.573 | 0.901 | 0.195 | 0.688 | 0.776 | 0.703 | 0.417 | 0.605 | 0.856 | 0.982 | |

| 2 | 0.67 | 0.635 | 0.644 | 0.82 | 0.558 | 0.856 | 0.176 | 0.658 | 0.741 | 0.736 | 0.366 | 0.632 | 0.839 | 0.981 | ||

| EffNet | RGB | 1 | 0.644 | 0.625 | 0.588 | 0.822 | 0.545 | 0.894 | 0.052 | 0.656 | 0.783 | 0.588 | 0.368 | 0.551 | 0.844 | 0.982 |

| 2 | 0.664 | 0.639 | 0.623 | 0.798 | 0.546 | 0.948 | 0.049 | 0.63 | 0.863 | 0.677 | 0.351 | 0.63 | 0.834 | 0.981 | ||

| 10 m | 1 | 0.707 | 0.71 | 0.636 | 0.847 | 0.596 | 0.944 | 0.309 | 0.655 | 0.906 | 0.705 | 0.374 | 0.629 | 0.835 | 0.979 | |

| 2 | 0.692 | 0.684 | 0.63 | 0.807 | 0.551 | 0.93 | 0.263 | 0.68 | 0.876 | 0.684 | 0.388 | 0.608 | 0.842 | 0.98 | ||

| 10–20 m | 1 | 0.686 | 0.654 | 0.662 | 0.834 | 0.622 | 0.942 | 0.081 | 0.654 | 0.788 | 0.741 | 0.404 | 0.657 | 0.846 | 0.981 | |

| 2 | 0.654 | 0.608 | 0.64 | 0.825 | 0.566 | 0.909 | 0.078 | 0.706 | 0.562 | 0.686 | 0.411 | 0.629 | 0.836 | 0.981 | ||

| All | 1 | 0.692 | 0.676 | 0.645 | 0.834 | 0.61 | 0.947 | 0.177 | 0.695 | 0.791 | 0.698 | 0.407 | 0.631 | 0.844 | 0.983 | |

| 2 | 0.675 | 0.658 | 0.625 | 0.82 | 0.552 | 0.895 | 0.163 | 0.676 | 0.84 | 0.625 | 0.418 | 0.61 | 0.848 | 0.981 | ||

| MaxViT | RGB | 1 | 0.664 | 0.638 | 0.622 | 0.855 | 0.569 | 0.916 | 0.096 | 0.599 | 0.794 | 0.699 | 0.343 | 0.601 | 0.847 | 0.98 |

| 2 | 0.674 | 0.656 | 0.625 | 0.813 | 0.556 | 0.951 | 0.14 | 0.64 | 0.834 | 0.646 | 0.368 | 0.654 | 0.833 | 0.98 | ||

| 10 | 1 | 0.688 | 0.66 | 0.658 | 0.816 | 0.58 | 0.944 | 0.107 | 0.67 | 0.844 | 0.766 | 0.377 | 0.639 | 0.848 | 0.982 | |

| 2 | 0.711 | 0.672 | 0.701 | 0.814 | 0.56 | 0.942 | 0.215 | 0.664 | 0.838 | 0.885 | 0.377 | 0.702 | 0.841 | 0.981 | ||

| 10–20 m | 1 | 0.681 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.85 | 0.591 | 0.935 | 0.058 | 0.651 | 0.937 | 0.6 | 0.407 | 0.698 | 0.818 | 0.946 | |

| 2 | 0.674 | 0.644 | 0.642 | 0.822 | 0.584 | 0.943 | 0.015 | 0.666 | 0.836 | 0.689 | 0.376 | 0.659 | 0.842 | 0.981 | ||

| All | 1 | 0.672 | 0.664 | 0.606 | 0.838 | 0.621 | 0.943 | 0.042 | 0.655 | 0.886 | 0.569 | 0.39 | 0.604 | 0.86 | 0.983 | |

| 2 | 0.686 | 0.665 | 0.644 | 0.829 | 0.571 | 0.922 | 0.086 | 0.653 | 0.932 | 0.658 | 0.387 | 0.687 | 0.843 | 0.981 |

| Enc | Sp | Stride | Mean | N.A. Mean | A. Mean | Build. | Transp. | Water | N.A. Gnd. | N.A. Low B. | N.A. Wtl. | A. Gnd. | A. Low B. | A. Wtl | A. Wood | Ulbl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSP | RGB | 1 | 0.613 | 0.563 | 0.635 | 0.838 | 0.478 | 0.802 | 0.05 | 0.599 | 0.613 | 0.643 | 0.613 | 0.563 | 0.635 | 0.838 |

| 2 | 0.603 | 0.579 | 0.582 | 0.825 | 0.45 | 0.845 | 0.097 | 0.655 | 0.604 | 0.484 | 0.603 | 0.579 | 0.582 | 0.825 | ||

| 10 m | 1 | 0.622 | 0.591 | 0.615 | 0.823 | 0.503 | 0.898 | 0.046 | 0.633 | 0.645 | 0.572 | 0.622 | 0.591 | 0.615 | 0.823 | |

| 2 | 0.629 | 0.625 | 0.584 | 0.836 | 0.501 | 0.907 | 0.06 | 0.655 | 0.793 | 0.494 | 0.629 | 0.625 | 0.584 | 0.836 | ||

| 10–20 m | 1 | 0.609 | 0.582 | 0.594 | 0.851 | 0.498 | 0.883 | 0.066 | 0.596 | 0.596 | 0.484 | 0.609 | 0.582 | 0.594 | 0.851 | |

| 2 | 0.598 | 0.588 | 0.556 | 0.854 | 0.481 | 0.9 | 0.039 | 0.674 | 0.579 | 0.457 | 0.598 | 0.588 | 0.556 | 0.854 | ||

| All | 1 | 0.635 | 0.612 | 0.622 | 0.836 | 0.507 | 0.915 | 0.084 | 0.638 | 0.692 | 0.562 | 0.635 | 0.612 | 0.622 | 0.836 | |

| 2 | 0.614 | 0.595 | 0.589 | 0.807 | 0.485 | 0.876 | 0.053 | 0.597 | 0.753 | 0.53 | 0.614 | 0.595 | 0.589 | 0.807 | ||

| EffNet | RGB | 1 | 0.614 | 0.569 | 0.628 | 0.839 | 0.504 | 0.813 | 0.024 | 0.448 | 0.784 | 0.603 | 0.614 | 0.569 | 0.628 | 0.839 |

| 2 | 0.584 | 0.563 | 0.555 | 0.874 | 0.425 | 0.785 | 0.016 | 0.601 | 0.674 | 0.516 | 0.584 | 0.563 | 0.555 | 0.874 | ||

| 10 m | 1 | 0.607 | 0.576 | 0.599 | 0.819 | 0.434 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 0.565 | 0.695 | 0.552 | 0.607 | 0.576 | 0.599 | 0.819 | |

| 2 | 0.607 | 0.583 | 0.589 | 0.869 | 0.468 | 0.909 | 0.008 | 0.548 | 0.696 | 0.517 | 0.607 | 0.583 | 0.589 | 0.869 | ||

| 10–20 m | 1 | 0.613 | 0.581 | 0.606 | 0.852 | 0.461 | 0.924 | 0.048 | 0.64 | 0.563 | 0.581 | 0.613 | 0.581 | 0.606 | 0.852 | |

| 2 | 0.6 | 0.565 | 0.595 | 0.843 | 0.415 | 0.919 | 0.019 | 0.559 | 0.638 | 0.512 | 0.6 | 0.565 | 0.595 | 0.843 | ||

| All | 1 | 0.602 | 0.572 | 0.592 | 0.855 | 0.458 | 0.886 | 0.07 | 0.591 | 0.57 | 0.461 | 0.602 | 0.572 | 0.592 | 0.855 | |

| 2 | 0.601 | 0.567 | 0.594 | 0.855 | 0.446 | 0.899 | 0.032 | 0.632 | 0.538 | 0.494 | 0.601 | 0.567 | 0.594 | 0.855 | ||

| MaxViT | RGB | 1 | 0.588 | 0.539 | 0.6 | 0.828 | 0.439 | 0.794 | 0.04 | 0.575 | 0.56 | 0.553 | 0.588 | 0.539 | 0.6 | 0.828 |

| 2 | 0.585 | 0.55 | 0.577 | 0.877 | 0.454 | 0.786 | 0.031 | 0.553 | 0.598 | 0.541 | 0.585 | 0.55 | 0.577 | 0.877 | ||

| 10 | 1 | 0.599 | 0.578 | 0.572 | 0.87 | 0.49 | 0.902 | 0.073 | 0.549 | 0.585 | 0.42 | 0.599 | 0.578 | 0.572 | 0.87 | |

| 2 | 0.602 | 0.595 | 0.554 | 0.855 | 0.474 | 0.919 | 0.06 | 0.591 | 0.671 | 0.405 | 0.602 | 0.595 | 0.554 | 0.855 | ||

| 10–20 m | 1 | 0.596 | 0.551 | 0.604 | 0.827 | 0.424 | 0.915 | 0.075 | 0.57 | 0.498 | 0.673 | 0.596 | 0.551 | 0.604 | 0.827 | |

| 2 | 0.599 | 0.568 | 0.589 | 0.849 | 0.451 | 0.91 | 0.004 | 0.58 | 0.613 | 0.509 | 0.599 | 0.568 | 0.589 | 0.849 | ||

| All | 1 | 0.613 | 0.563 | 0.633 | 0.853 | 0.421 | 0.922 | 0.007 | 0.601 | 0.574 | 0.585 | 0.613 | 0.563 | 0.633 | 0.853 | |

| 2 | 0.594 | 0.572 | 0.567 | 0.846 | 0.447 | 0.922 | 0.035 | 0.612 | 0.573 | 0.418 | 0.594 | 0.572 | 0.567 | 0.846 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Uzdiaev, M.; Astapova, M.; Ronzhin, A.; Figurek, A. Empirical Evaluation of UNet for Segmentation of Applicable Surfaces for Seismic Sensor Installation. J. Imaging 2026, 12, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010034

Uzdiaev M, Astapova M, Ronzhin A, Figurek A. Empirical Evaluation of UNet for Segmentation of Applicable Surfaces for Seismic Sensor Installation. Journal of Imaging. 2026; 12(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleUzdiaev, Mikhail, Marina Astapova, Andrey Ronzhin, and Aleksandra Figurek. 2026. "Empirical Evaluation of UNet for Segmentation of Applicable Surfaces for Seismic Sensor Installation" Journal of Imaging 12, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010034

APA StyleUzdiaev, M., Astapova, M., Ronzhin, A., & Figurek, A. (2026). Empirical Evaluation of UNet for Segmentation of Applicable Surfaces for Seismic Sensor Installation. Journal of Imaging, 12(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010034