Dynamic Estimation of Load-Side Virtual Inertia with High Power Density Support of EDLC Supercapacitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. System-Level Coordination and Learning-Based Frequency Regulation

1.1.2. Distributed Secondary Control Under Communication Constraints

1.1.3. Converter-Side Frequency Support and Parameter Adaptation

1.1.4. Resource-Side Fast Support from Storage, Converter-Interfaced Links, CSP, Demand Response, and PV–Storage Coordination

1.1.5. Fault-Driven Frequency Dynamics and Experimental Platforms

1.1.6. Demand-Side Frequency Control with Flexible Loads and Consumer-Centric Constraints

1.1.7. Gap Statement and Positioning

1.2. Research Problem

2. Framework for Research Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Demand Forecast Based on Wide Neural Networks

3.2. Conceptualization of the Virtual Inertia Model

3.3. Dynamic Model with Virtual Inertia and Demand Prediction

3.3.1. Incorporating Demand Prediction

3.3.2. Estimation of Virtual Inertia

3.3.3. Interpretation

3.4. EDLC Supercapacitor Support Power

- Determine for the worst-case scenario of frequency variation.

- Multiply by the required support time ().

- Calculate the necessary capacitance:

- Select the number of cells in series/parallel to achieve the desired voltage and energy.

3.5. Case Study

3.6. Energy Storage System Sizing Criteria

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Training and Validation of Demand Forecasting

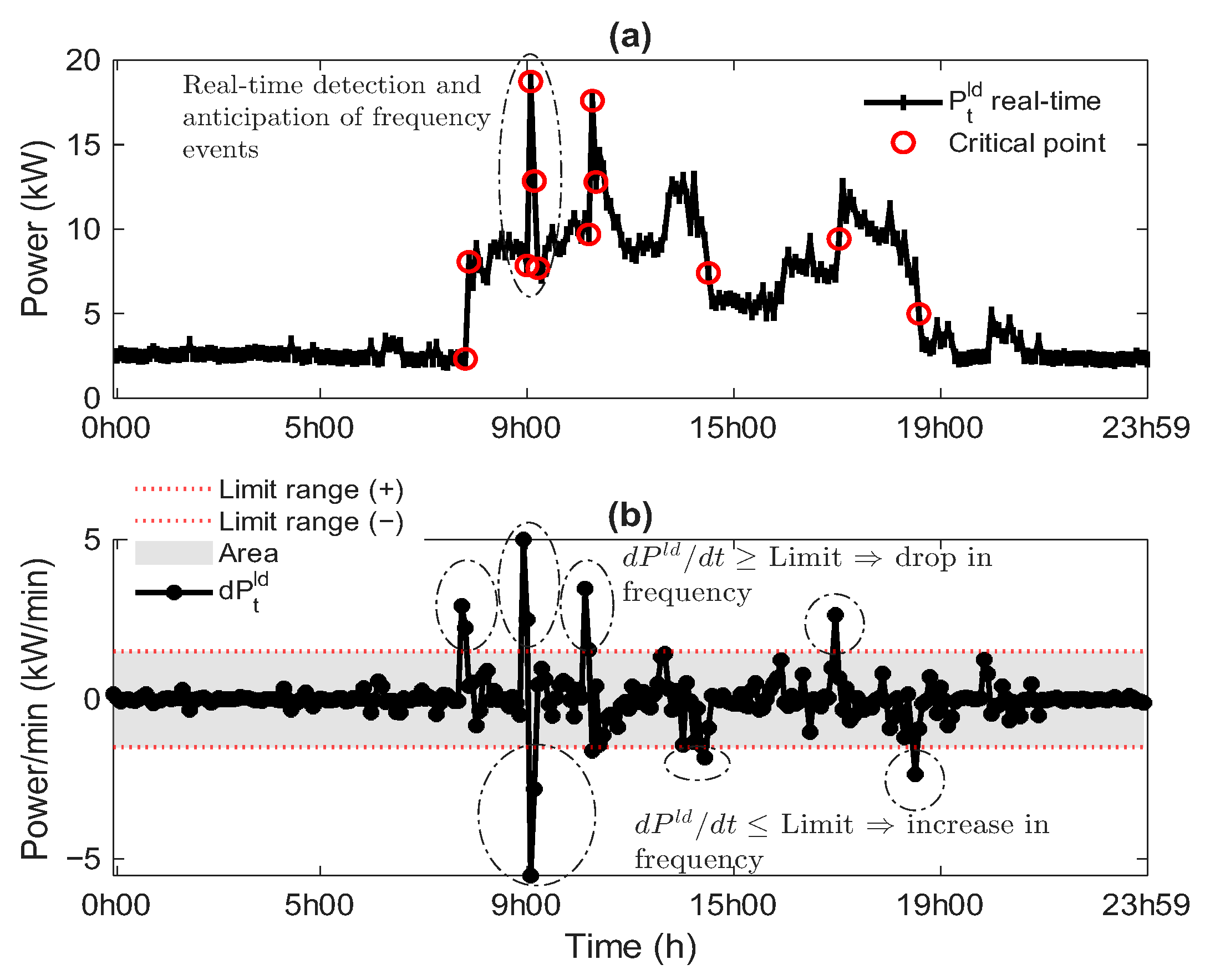

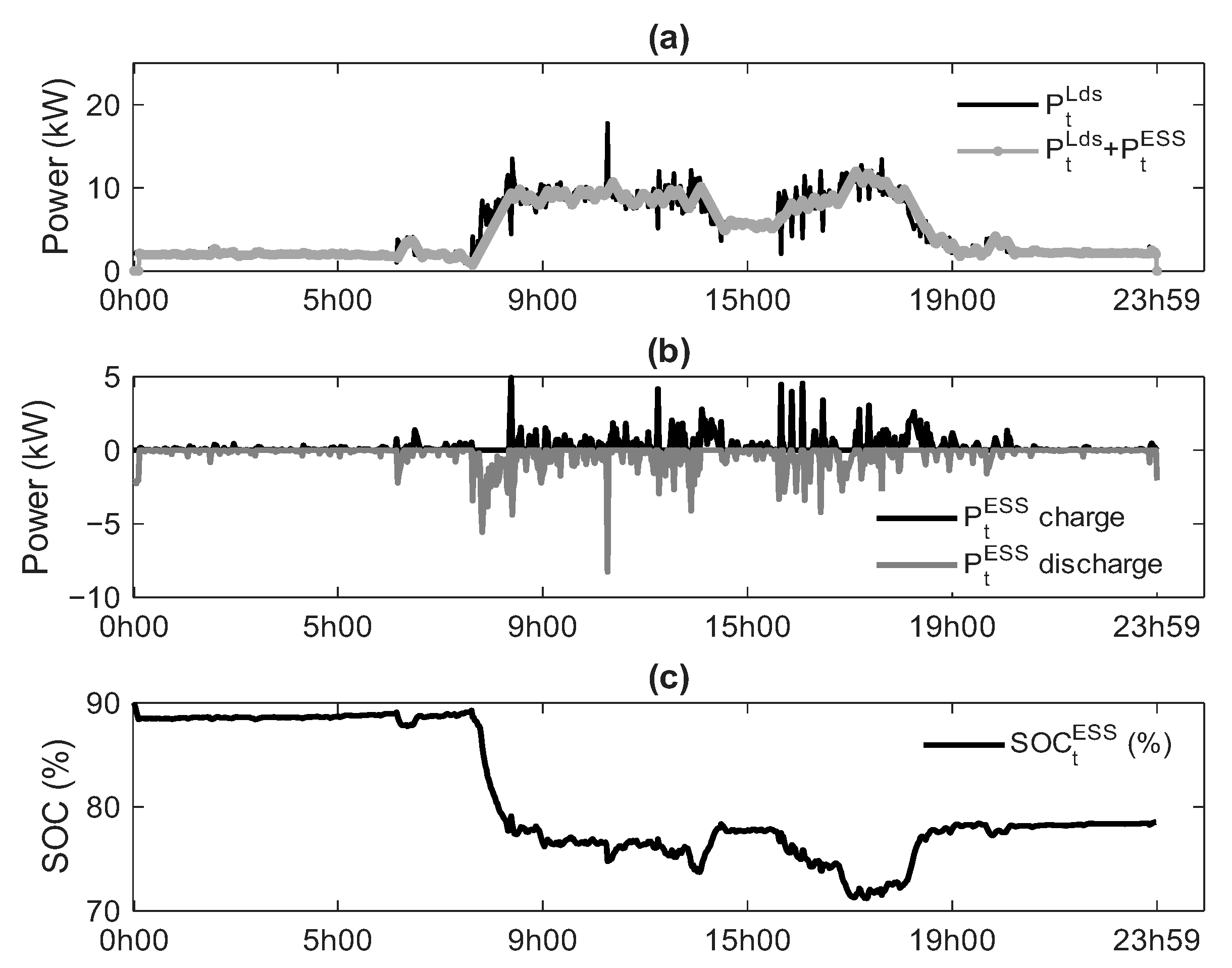

4.2. Analysis of Real-Time Frequency Deviation Estimation

4.3. Comparison Between Scenarios with and Without Virtual Inertia Support

4.4. Energy Storage System Sizing

4.5. Comparison to Other Storage Technologies

4.6. Sensitivity Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RESs | Renewable energy sources |

| FFR | Fast frequency response |

| DSFRs | Demand-side flexible resources |

| EV | Electrical vehicle |

| VSGs | Virtual synchronous generators |

| RPS | Rapid power support |

| BESSs | Battery energy storage systems |

| LFC | Load frequency control |

| EDLCs | Electrical double layer supercapacitors |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| WT | Wind turbine |

| ESS | Energy storage system |

| RoCoF | Rate of change of frequency |

| VIC | Virtual inertia controller |

| WNNs | Wide neural networks |

| ReLU | Rectified linear unit |

| SOC | State of charge |

References

- Yan, K.; Li, G.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, T.; Li, X. Frequency Control and Optimal Operation of Low-Inertia Power Systems with HVDC and Renewable Energy: A Review. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 4279–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazon, M.N.H.; Jawad, A. Frequency control challenges and potential countermeasures in future low-inertia power systems: A review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 6191–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, A.; Abouyehia, M.; Ahmed, K.H. Resilience and Frequency Control in Low-Inertia Power Systems: Challenges and Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 13th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Nagasaki, Japan, 9–13 November 2024; pp. 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therapontos, P.; Tapakis, R.; Aristidou, P. Assessing the Impact of Primary Frequency Support from IBRs in Low Inertia Isolated Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Orlando, FL, USA, 16–20 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerci, T.; Hurtado, M.; Gjergji, M.; Tweed, S.; Kennedy, E.P.; Milano, F. Frequency Quality in Low-Inertia Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Orlando, FL, USA, 16–20 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Geng, H. Frequency Stability of Renewable Energy Integrated Low-Inertia Power Systems During Grid Faults. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), Shanghai, China, 9–12 June 2023; pp. 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, D.; Martinez, S. Fast-Frequency Response Provided by DFIG-Wind Turbines and Its Impact on the Grid. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 4002–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizipanah-Abarghooee, R.; Malekpour, M.; Sun, M.; Marshal, B.; Karimi, M.; Terzija, V.V. Enhanced Fast Frequency Control Scheme and Wide-Area Monitoring for Low Inertia Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT-Europe), Grenoble, France, 23–26 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagi, S.; Aristidou, P. Sizing of Fast Frequency Response Reserves for improving frequency security in low-inertia power systems. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 42, 101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Masood, N.A.; Saha, T.K. Investigation of Frequency Response in a Low Inertia Power System and its Improvement. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA/IAEAC), Chongqing, China, 12–14 March 2021; pp. 1771–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, S.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z. Fast power correction based transient frequency response strategy for energy storage system in low-inertia power systems. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, S.; Meng, F. Rapid Power Support-based Frequency Response Strategy for Grid Forming Inverter in Low-Inertia Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Power Engineering Technology (ICPET), Tianjin, China, 27–30 July 2023; pp. 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Haokun, L.; Miao, M.; Guo, C. A New Grid Connection Mode of Low Inertia Power System. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Power Electronics and Smart Applications (ICoPESA), Singapore, 25–27 February 2022; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Geng, H.; Rajashekara, K.S.; Chandra, A. Analysis and Control of Frequency Stability in Low-Inertia Power Systems: A Review. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 2363–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Li, X.; Chen, T.; Liu, J. Load Frequency Control via Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning and Consistency Model for Diverse Demand-Side Flexible Resources. Processes 2025, 13, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosaletsi, O.E.T.; Cronjé, W.A.; Masisi, L.M. Demand Side Frequency Control in Low Inertia Power System. In Proceedings of the ICPEE 2023, Bhubaneswar, India, 3–5 January 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Ding, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhang, K. Robust H∞ load frequency control of power systems considering intermittent characteristics of demand-side resources. Electronics 2020, 9, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, G.; Geng, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, K.; Zhang, K. Load Frequency Robust Control Considering Intermittent Characteristics of Demand-Side Resources. Energies 2022, 15, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shan, X.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K. Coordinated Frequency Control of Generation and Demand Side Considering Demand Side Resource Callback Characteristic. In Proceedings of the AUTEEE 2020, Shenyang, China, 20–22 November 2020; pp. 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, T.; Hill, D.J. Switched distributed load-side frequency control of power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 105, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Chi, M.; Zhang, Y. Demand-Side Frequency Control in Power Network Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the IAI 2023, Shenyang, China, 21–24 August 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasola-Aignesberger, L.; Wiegel, F.; Waczowicz, S.; Hagenmeyer, V.; Martinez, S. Experimental validation of demand side response rates for frequency control. In Proceedings of the eGrid 2023, Karlsruhe, Germany, 16–18 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, S.; Nee Dey, S.H.; Paul, S. Role of Demand Side Management in Automatic Load Frequency control. In Proceedings of the ICEFEET 2020, Patna, India, 10–11 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, J.; Gao, L.; Ning, L. The output flexibility optimization control of load-side wind turbine considering client demand response. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2876, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shi, R.; Jia, L.; Lee, K. An innovative coordinated control strategy for frequency regulation in power systems with high renewable penetration. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Wajid, K.; Aziz, A.; Yousaf, M.Z.; Zhang, W.; Cai, Z.; Khan, B.; Ali, A.A.Y.; Mabunda, N.E.; Rajkumar, S. A deep recurrent neural network-based droop control strategy for frequency stabilization in low-inertia power systems with high renewable energy penetration. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, G.; He, J. Dual-Mode Laguerre MPC and Its Application in Inertia-Frequency Regulation of Power Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Yongliang, Z.H.; Yukun, T.A.; Xinyan, L.I.; Jingjing, S.H. Frequency control strategy of microgrid distributed virtual synchronous generator based on asynchronous event triggered communication protocol. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 168, 110666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Tan, Y.; Xie, Y. Collaborative adaptive inertia and damping control for virtual synchronous generator in low-inertia systems. Energy 2025, 287, 129186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. A Synergetic Control-Based Dynamic Frequency Control Strategy for VSG in Microgrid. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Control Science (IC2ECS), Hangzhou, China, 29–31 December 2023; pp. 594–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qin, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. Cooperative Control Strategy for Virtual Inertia Based on Fuzzy Control. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Control Science and Systems Engineering (ICCSSE), Guangzhou, China, 14–16 July 2022; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, M.G.; Deepak, M.V.; Mathew, A.T. A Coordinated Frequency Control Strategy for Low Inertia Power System Incorporating Fractional-Order Controllers, Inertia Emulation and Plug-in Electric Vehicle. IET Energy Syst. Integr. 2025, 7, e70021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Liu, P.; Sun, J. Active support control of multi-winding power electronic transformer for inertia emulation in renewable systems. Appl. Energy 2025, 357, 122101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.K.; Haque, M.H.; Mahfuzul Aziz, S. Enhancing Frequency Response Characteristics of Low Inertia Power Systems Using Battery Energy Storage. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 116861–116874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ren, W.; Li, C.; Dong, H.; Cao, H.; Li, P.; Wang, Z. Coordinated Control Strategy of Inertia Support for MMC-HVDC Connecting Offshore Wind Farms Considering Frequency Secondary Drop. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Shenyang, China, 29 November–2 December 2024; pp. 3924–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Du, E.; Wang, H.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, N. Dynamic frequency control strategy for the CSP plant in power systems with low inertia. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2023, 17, 3063–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoy, N.I.; Mortuza, M.G.; Hossain, M.I.; Mohammad, N. Rate of Change of Frequency (RoCoF) Improvement of Low Inertia Power System by Using Refrigerated Warehouse. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Power System (ICPS), Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 13–15 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, H.; Fu, G.; Xin, Y.; Wang, L. Coordinated Control Strategies for Enhancing Frequency Stability of Photovoltaic and Storage Networking Systems. Dianli Jianshe/Electr. Power Constr. 2025, 46, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, P. Research on source-load frequency response control strategy of distributed generation system. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2021, 16, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosaletsi, O.E.; Cronjé, W.A.; Masisi, L.M. Design and Implementation of a Low-Inertia Microgrid Platform with Real-Time Inertia Adjustment for Frequency Stability Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2025 33rd Southern African Universities Power Engineering Conference (SAUPEC), Pretoria, South Africa, 29–30 January 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Penetration of Power Electronic Interfaced Power Sources and the Potential Contribution of Grid Forming Converters; Technical Report; ENTSO-E Technical Group on High Penetration of Power Electronic Interfaced Power Sources: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Tielens, P.; Van Hertem, D. The relevance of inertia in power systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criollo, A.; Minchala-Avila, L.I.; Benavides, D.; Arévalo, P.; Tostado-Véliz, M.; Sánchez-Lozano, D.; Jurado, F. Enhancing Virtual Inertia Control in Microgrids: A Novel Frequency Response Model Based on Storage Systems. Batteries 2024, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, D.; Arévalo-Cordero, P.; Ochoa-Correa, D.; Torres, D.; Ríos, A. Predictive Energy Storage Management with Redox Flow Batteries in Demand-Driven Microgrids. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.L.; González, L.G.; Sempértegui, R. Micro grid laboratory as a tool for research on non-conventional energy sources in Ecuador. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Autumn Meeting on Power, Electronics and Computing (ROPEC), Ixtapa, Mexico, 8–10 November 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, D.; Arévalo-Cordero, P.; Espinosa Domínguez, J.; Ochoa-Correa, D.; Torres, D.; Ríos, A. Smart meter-based demand forecasting for energy management using supercapacitors. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1681139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Reference | Main Contribution | Improvement Opportunity | Relation to This Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| System-level adaptive control | Zhang et al., 2025 [25] | DRL-based DSCS for coordinated frequency regulation in high-RES systems. | No inertia estimation or EDLC modeling. | System-level view; this work focuses on inertia estimation and EDLC actuation. |

| Learning-based droop adaptation | Feng et al., 2025 [26] | DDRNN-based adaptive droop control using temporal frequency features. | No inertia-equivalent (H) or EDLC constraints. | Prediction motivates adaptation; this work applies physics-based estimation with EDLCs. |

| Predictive control for inertia–frequency regulation | Liu et al., 2025 [27] | Laguerre MPC separating inertia support and frequency regulation. | No online inertia identification or EDLC dispatch. | Aligned in objectives; this work avoids full MPC via online estimation. |

| Distributed secondary control/communications | He et al., 2025 [28] | Event-triggered distributed secondary frequency control for VSGs. | No inertia estimation or fast EDLC coordination. | Complementary layer; this work targets estimation + fast actuation. |

| GFM inverter transient power support | Zhang et al., 2023 [12] | Mode-switching RPS for GFM inverter transient frequency support. | Fixed inertia/damping; no estimation or EDLC focus. | Related at actuator level; this work adds estimation and EDLC viewpoint. |

| Adaptive inertia and damping scheduling (VSG) | Li et al., 2025 [29] | Rule-based adaptive inertia and damping tuning for VSGs. | No identification of inertia-equivalent needs or EDLC constraints. | Shares adaptation goal; this work estimates H online and dispatches EDLCs. |

| Dynamic frequency support under dispatch variations (VSG) | Liu et al., 2023 [30] | Synergetic control of VSG inertia and damping under dispatch changes. | No demand prediction or EDLC-based fast actuation. | Motivates dynamic support; this work adds estimation and EDLC dispatch. |

| Coordination of PV–wind–storage inertia response | Gao et al., 2022 [31] | Fuzzy coordination of RESs and storage for virtual inertia support. | No quantified inertia requirement or estimation layer. | This work provides estimated inertia needs for EDLC-based coordination. |

| PEV-based inertia emulation and real-time testing | Sony et al., 2025 [32] | PEV-based inertia emulation validated on HIL platform. | Different bandwidth/constraints than EDLCs; no inertia estimation. | Supports fast support relevance; this work targets EDLCs with estimation. |

| Power-electronics transformer as inertia-emulation interface | Li et al., 2025 [33] | PET-based inertial and voltage support via SG-based control. | No demand prediction, inertia estimation, or EDLC usage. | Alternative actuator; this work selects EDLCs with an estimation layer. |

| BESS contribution to frequency response (PV-dominated grids) | Hasan et al., 2024 [34] | BESS-based inertia and PFR enhancement in PV-dominated systems. | Lower bandwidth than EDLCs; no inertia estimation. | Confirms storage benefits; this work targets ultra-fast EDLC support. |

| Converter-interfaced inertia support and recovery | Jiang et al., 2024 [35] | MMC-HVDC inertia support with recovery-aware control. | Specific to HVDC/MMC dynamics; no load-side estimation. | Analogous energy limits; this work manages EDLCs via estimation. |

| CSP scheduling for frequency response | Fang et al., 2023 [36] | Frequency-response-aware unit commitment for CSP systems. | Planning-level only; no fast control or estimation. | Complementary at planning layer; this work targets fast device-level support. |

| Demand-side fast support (TCLs/cold storage) | Udoy et al., 2023 [37] | RoCoF mitigation via direct load control of TCLs. | Comfort constraints; no inertia estimation or EDLCs. | Shares load-side view; EDLC avoids comfort trade-offs. |

| PV–storage multi-timescale coordination | Jiang et al., 2025 [38] | Multi-timescale PV-storage frequency coordination with SOC awareness. | No explicit inertia identification or EDLC focus. | Aligned in SOC-aware control; this work adds estimation and EDLCs. |

| Source–load frequency response coupling | Zhang and Peng, 2021 [39] | Load-side converter-based auxiliary inertia provision. | No online inertia inference or EDLC constraints. | Closest conceptually; this work adds estimation and EDLC dispatch. |

| Fault-driven frequency dynamics | He and Geng, 2023 [6] | Fault-time frequency stability modeling in low-inertia systems. | No actuator design or inertia estimation. | Provides disturbance insight; this work targets post-disturbance support. |

| Experimental platform for programmable inertia | Bosaletsi et al., 2025 [40] | Programmable inertia testbed for controlled experiments. | No EDLC support or measurement-based estimation. | Suitable for experimental validation of this work. |

| Demand-side control with reinforcement learning | Yu et al., 2025 [15] | MARL-based demand-side frequency control using inertia-like models. | No physical inertia estimation or EDLC actuation. | Supports demand-side vision; this work adds estimation + EDLCs. |

| Demand-side control as Markov game | Liu et al., 2023 [21] | MADDPG-based decentralized demand-side frequency control. | No inertia-equivalent estimation or fast actuator. | Decentralization aligned; this work provides physical estimation layer. |

| Intermittent control under time delays | Yuan et al., 2020 [17] | Intermittent LFC with delay-aware stability guarantees. | No inertia estimation or EDLC coordination. | Informs intermittency; this work adds continuous estimation + EDLCs. |

| H∞ control for intermittent demand response | Ming et al., 2022 [18] | Robust LFC with intermittent DR. | No real-time inertia estimation or EDLC stage. | Complementary robust layer; this work focuses on estimation + fast support. |

| Callback effects in DR-based regulation | Li et al., 2020 [19] | Modeling and mitigation of rebound effects in DR. | No inertia-like estimation or fast storage coupling. | Addresses rebound; this work moderates EDLCs via estimation. |

| Distributed load-side frequency control | Zhang et al., 2019 [20] | Switched consensus-based load-side frequency control. | Threshold-based; no continuous inertia estimation. | Architecture aligned; this work adds inertia estimation + EDLCs. |

| DR-induced oscillations in islanded systems | Casasola-Aignesberger et al., 2023 [22] | Experimental evidence of DR-induced frequency oscillations. | No adaptive tuning or inertia estimation. | Motivates estimation-driven moderation of EDLC support. |

| ALFC with DR in wind-integrated systems | Bhuyan and Pati, 2020 [23] | DR-enhanced ALFC in wind-integrated multi-area systems. | No RoCoF-focused inertia estimation or EDLCs. | Supports DR relevance; this work targets fast transient shaping. |

| Two-layer optimization with demand-side constraints | Huang et al., 2024 [24] | Hierarchical optimization with demand-side constraints. | No measurement-driven inertia mapping or EDLC actuation. | Motivates constraint-aware control; this work adds estimation + EDLCs. |

| DR-based frequency response with TCLs | Udoy et al., 2023 [16] | Demand-side fast frequency response using TCLs. | No inertia estimation or coordination with EDLCs. | Shares motivation; this work complements with EDLC-based support. |

| Pseudocode |

|---|

| 1: Load database |

| 1.1: data = [] |

| 2: Input and output configuration |

| 2.1: X = data(:, 1:4) |

| 2.2: Y = data(:, 5) |

| 3: Split data into training (70%) and validation (30%) |

| 3.1: cv = cvpartition(size(X,1), ‘HoldOut’, 0.3) |

| 3.2: = [X((cv), :)] |

| 3.3: = [Y((cv), :)] |

| 3.4: = [X((cv), :)] |

| 3.5: = [Y((cv), :)] |

| 4: Execution of Wide Neural Network |

| 4.1: net = feedforwardnet(100) |

| 4.2: net.trainFcn = ‘trainlm’ |

| 4.3: net.divideParam.trainRatio = 0.7 |

| 4.4: net.divideParam.valRatio = 0.3 |

| 4.5: net.divideParam.testRatio = 0 |

| 5: Network training |

| 5.1: |

| 6: Network validation |

| 6.1: |

| 7: Select data from day 5 |

| 7.1: = data(5, 1:4) |

| 8: Demand forecasting model |

| 8.1: |

| Pseudocode |

|---|

| 1: Dynamic frequency model formulation |

| 1.1: Define swing equation: |

| 1.2: |

| 1.3: Extend with virtual inertia: |

| 1.4: |

| 2: Incorporation of demand forecasting |

| 2.1: Predicted demand: |

| 2.2: = [] (demand forecasting data from Table 2) |

| 2.3: Real demand: |

| 2.4: |

| 2.5: Prediction error: |

| 2.6: |

| 2.7: Adjusted equation: |

| 2.8: |

| 3: Estimation of virtual inertia |

| 3.1: Rearrange for : |

| 3.2: |

| 4: Interpretation and application |

| 4.1: If is large ⇒ increase to dampen frequency variations. |

| 4.2: If ⇒ minimal contribution required. |

| Factor | Description | Example/Application | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power and Energy Capacity | The system must supply sufficient active power to stabilize frequency. Stored energy must cover critical periods of load and generation variation. | Example: covering load ramps in 150 kVA systems. | Assess whether the installed capacity is sufficient for high variability scenarios. |

| Renewable Energy Penetration | The higher the percentage of renewables, the greater the need for virtual inertia support. | Case: 27% renewable penetration in the system. | Analyze the tolerable penetration limit without compromising stability. |

| Dynamic Response of Storage | Technologies such as supercapacitors (EDLCs) or lithium batteries have different response times. | EDLC: milliseconds; batteries: seconds. | Compare technologies in terms of reaction speed and cost. |

| Load and Demand Profile | Demand variability (positive and negative ramps) is analyzed. | Dampen disconnections or sudden load increases. | Identify critical hours with higher variability. |

| Duration of Virtual Inertia Support | Defines how long frequency must remain within acceptable limits. | Example: maintain a frequency close to the established limits. | Determine minimum energy required for different scenarios. |

| Location in the Grid | In distributed systems with low base power, storage must be strategically installed. | Example: microgrid of 150 kVA. | Evaluate the impact of location on overall stability. |

| Selected Storage Technology | EDLC: high power, low energy, ideal for immediate frequency support. Batteries: higher energy, slower response. | Use of EDLCs. | Analyze the advantages of the systems applied to the case study. |

| Item | Model | Abbr. | RMSE | R2 | MSE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Long Short-Term Memory | LSTM | 1.1546 | 0.89 | 1.3330 | 11.08 |

| 2 | Narrow Neural Network | NNN | 1.6042 | 0.90 | 2.5734 | 12.40 |

| 3 | Bilayered Neural Network | BNN | 1.2979 | 0.94 | 1.6844 | 8.30 |

| 4 | Wide Neural Network | WNN | 1.0310 | 0.96 | 1.0630 | 6.30 |

| System Condition | Percentage (%) | Frequency Variation (Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| RES penetration | 27% | Hz |

| Variable demand energy | 33% | Hz |

| Variable demand energy + EDLC | 33% | Hz |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Criollo, A.; Benavides, D.; Ochoa-Correa, D.; Arévalo-Cordero, P.; Minchala-Avila, L.I.; Jerez, D. Dynamic Estimation of Load-Side Virtual Inertia with High Power Density Support of EDLC Supercapacitors. Batteries 2026, 12, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12020042

Criollo A, Benavides D, Ochoa-Correa D, Arévalo-Cordero P, Minchala-Avila LI, Jerez D. Dynamic Estimation of Load-Side Virtual Inertia with High Power Density Support of EDLC Supercapacitors. Batteries. 2026; 12(2):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12020042

Chicago/Turabian StyleCriollo, Adrián, Dario Benavides, Danny Ochoa-Correa, Paul Arévalo-Cordero, Luis I. Minchala-Avila, and Daniel Jerez. 2026. "Dynamic Estimation of Load-Side Virtual Inertia with High Power Density Support of EDLC Supercapacitors" Batteries 12, no. 2: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12020042

APA StyleCriollo, A., Benavides, D., Ochoa-Correa, D., Arévalo-Cordero, P., Minchala-Avila, L. I., & Jerez, D. (2026). Dynamic Estimation of Load-Side Virtual Inertia with High Power Density Support of EDLC Supercapacitors. Batteries, 12(2), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12020042