Carbon-Based Anode Materials for Metal-Ion Batteries: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

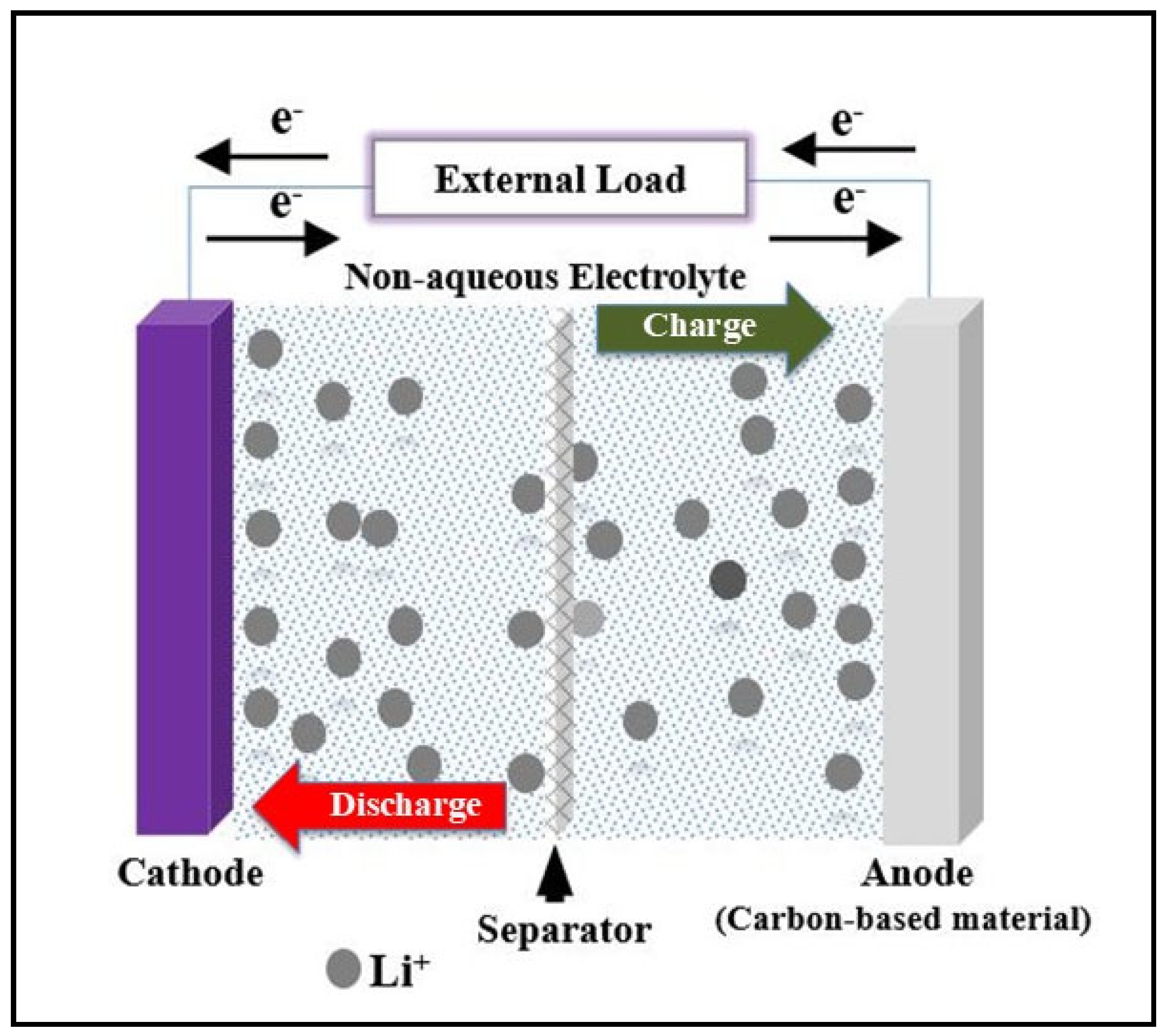

2. Batteries

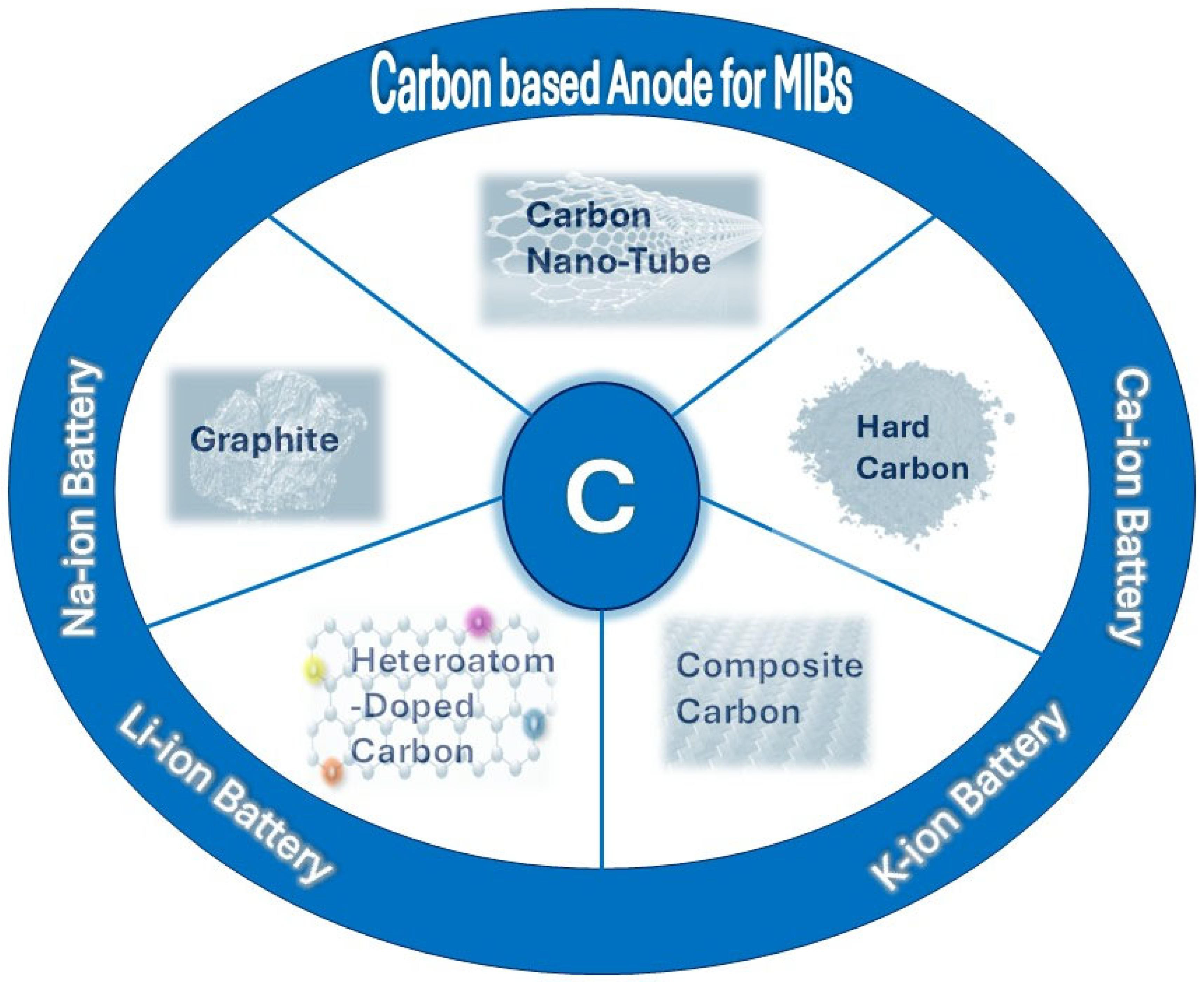

3. Anode in MIBS

4. Carbon-Based Anode Materials

5. Graphite-Based Materials as Anode for MIBS

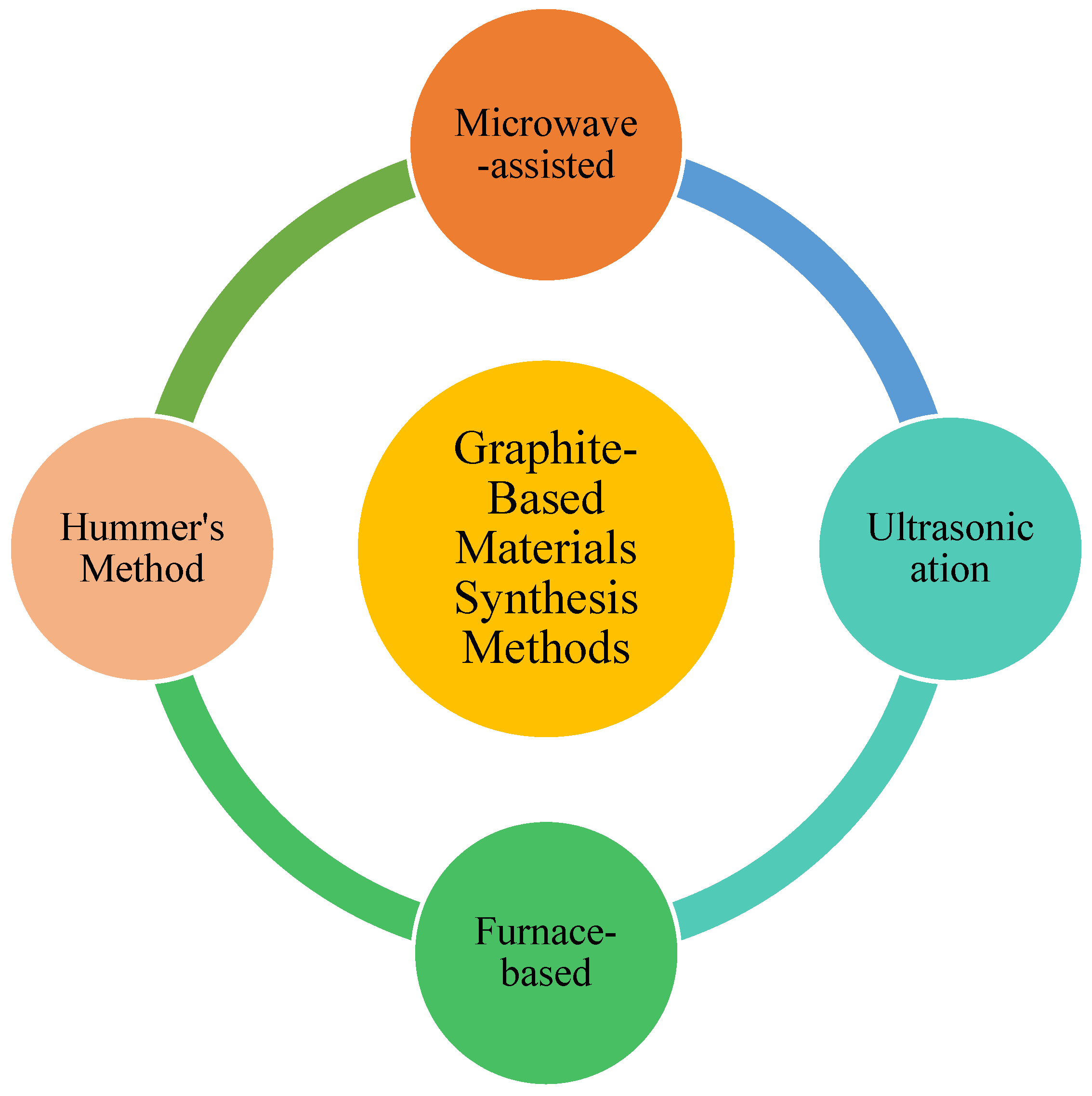

5.1. Synthesis of Graphitic Materials

5.1.1. Microwave-Assisted Method

5.1.2. Ultrasonication Method

5.1.3. Furnace-Based Method

5.1.4. Hummer’s Method

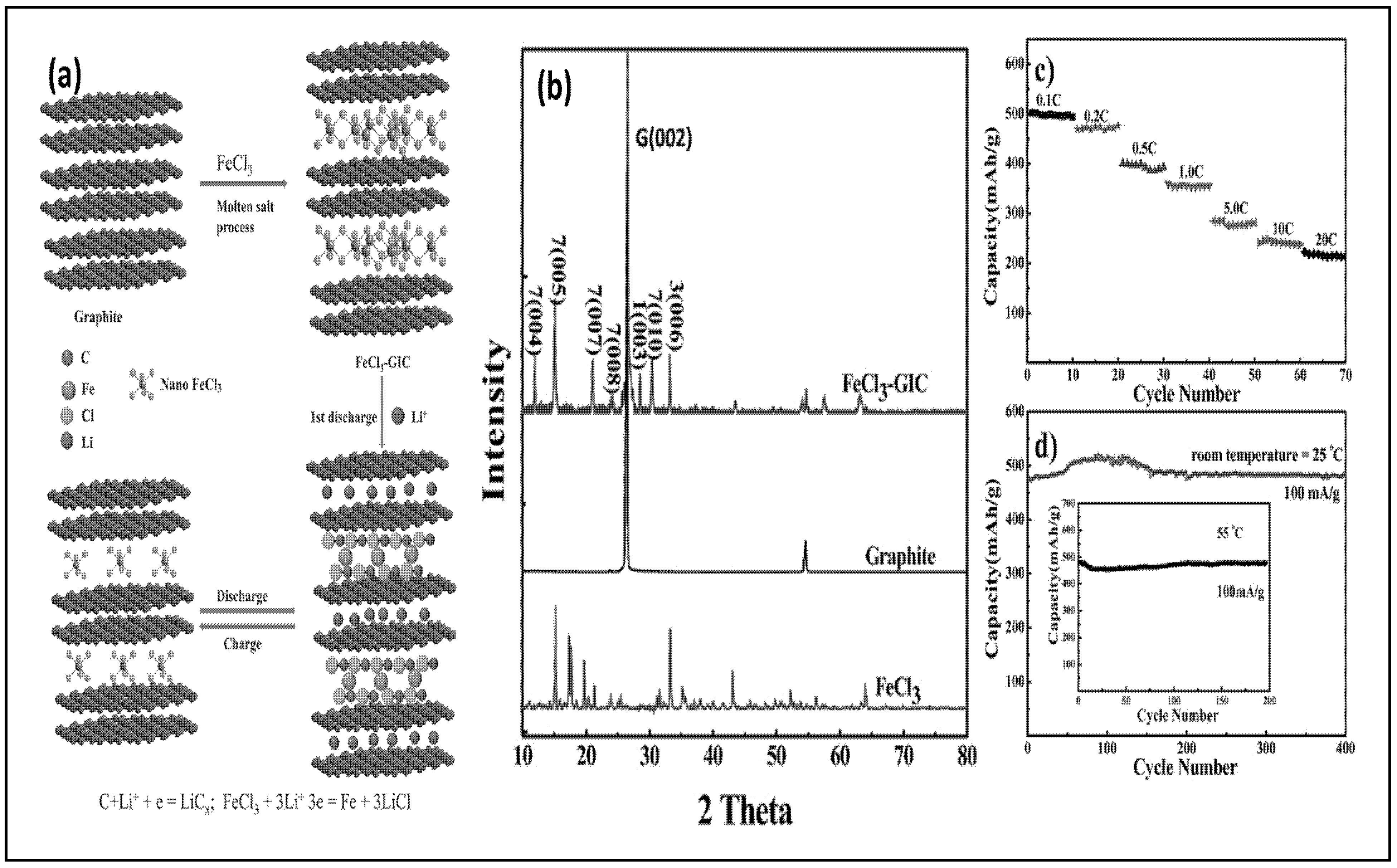

5.2. Graphite-Based Anode for LIBs

5.3. Graphite-Based Anode for SIBs

5.4. Graphite-Based Anode for KIBs

5.5. Graphite-Based Anode for Calcium-Ion Batteries (CIBs)

6. CNT-Based Materials as an Anode for MIBs

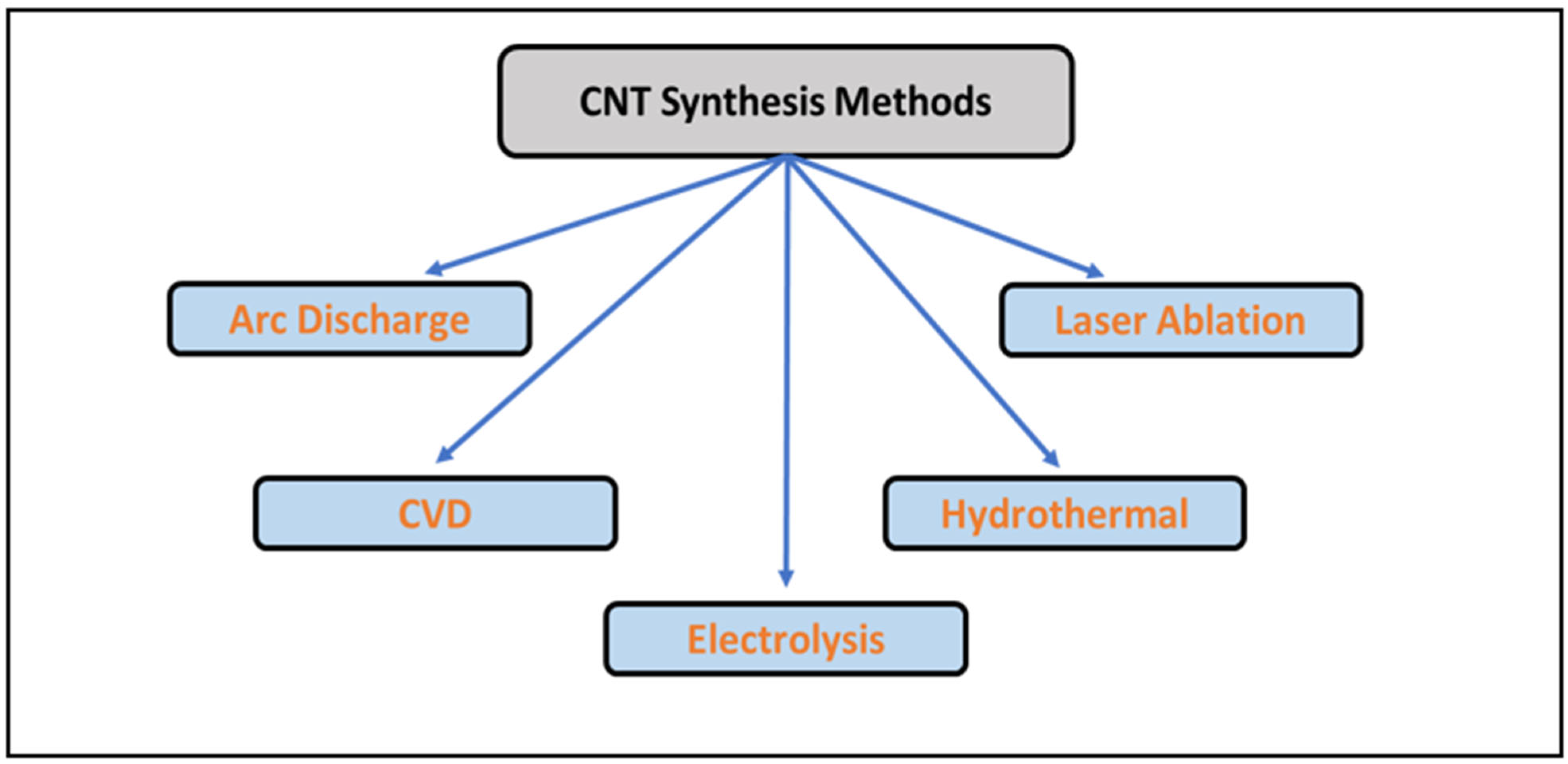

6.1. Synthesis of CNT-Based Materials

6.1.1. Arc Discharge Method

6.1.2. Laser Ablation Method

6.1.3. CVD Method

6.1.4. Hydrothermal Method

6.1.5. Electrolysis Method

6.2. CNT-Based Anode for LIBs

6.3. CNT-Based Anode for SIBs

6.4. CNT-Based Anode for KIBs

7. Hard Carbon Material as an Anode for MIBs

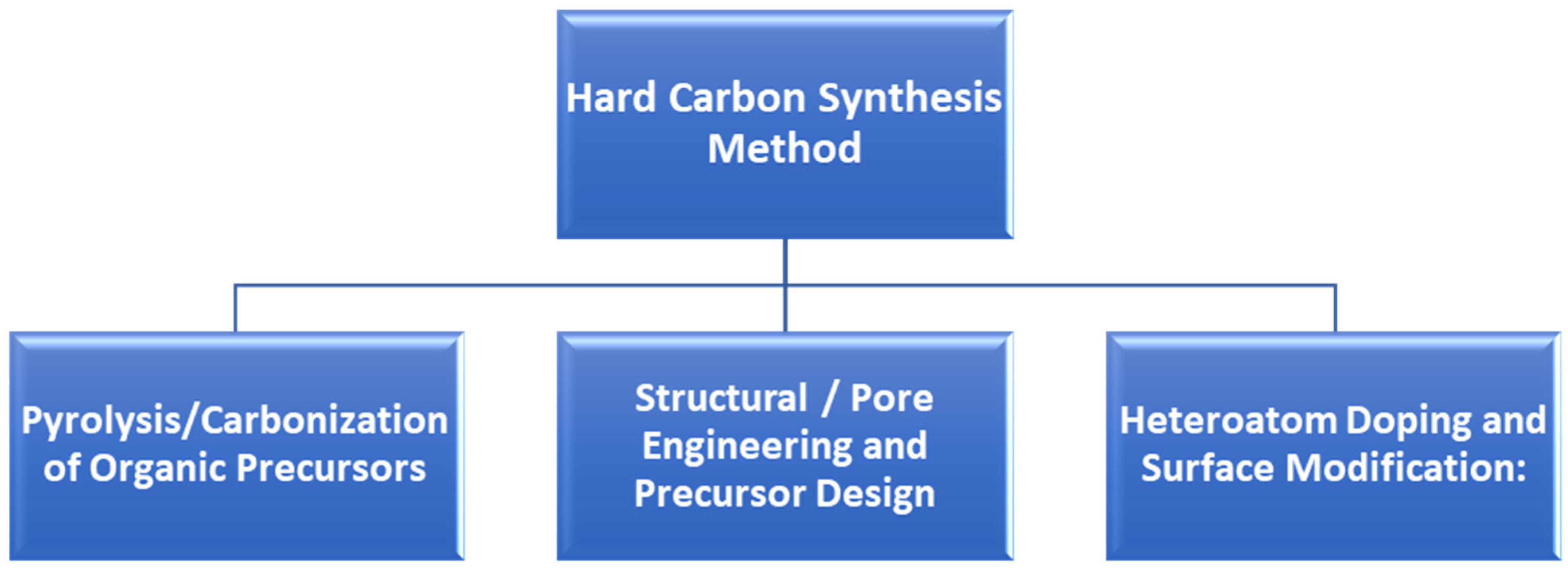

7.1. Synthesis of Hard Carbon Materials

7.1.1. Pyrolysis/Carbonization of Organic Precursors

7.1.2. Structural/Pore Engineering and Precursor Design

7.1.3. Heteroatom Doping and Surface Modification

7.2. Hard Carbon-Based Anode for LIBs

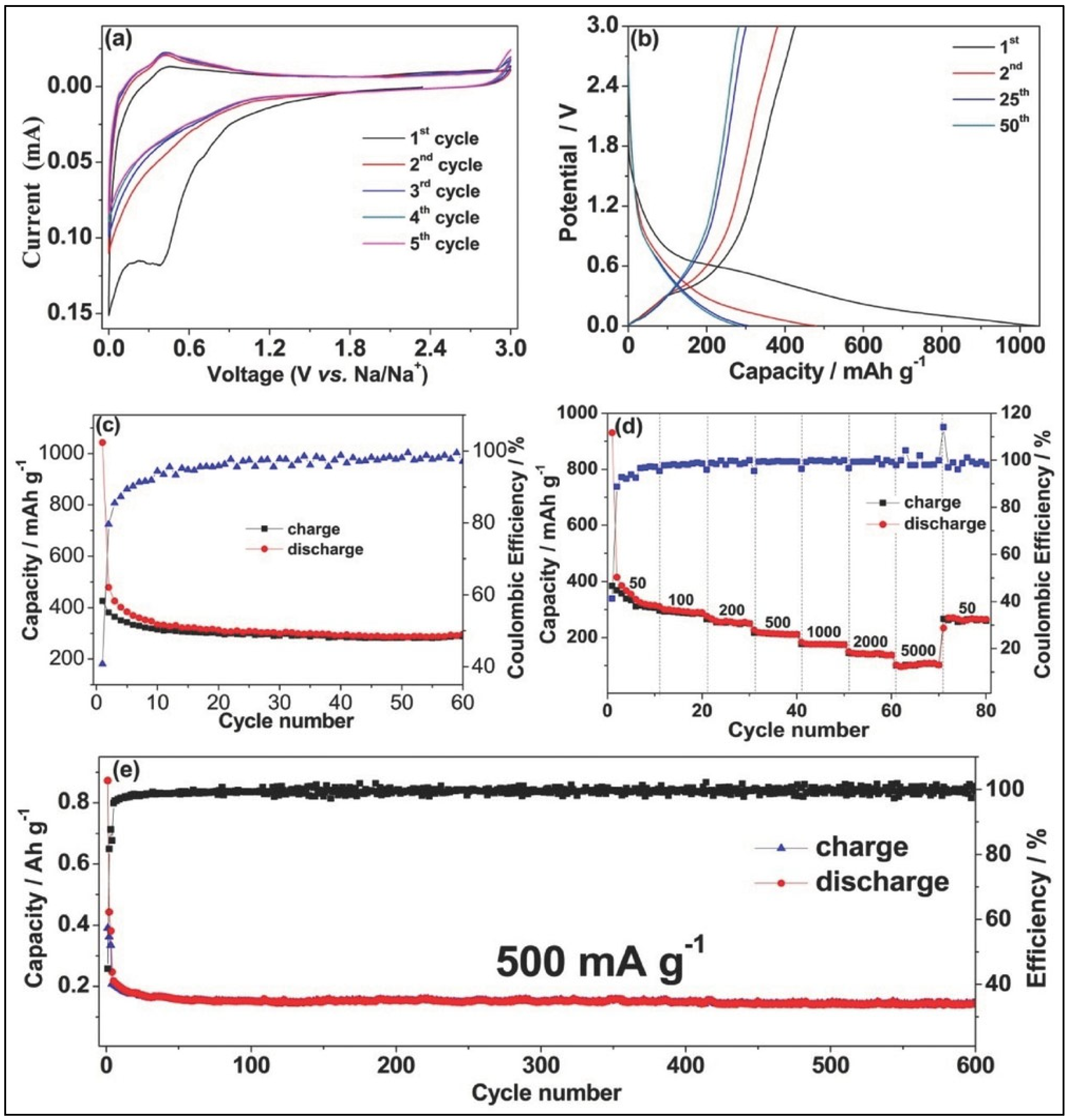

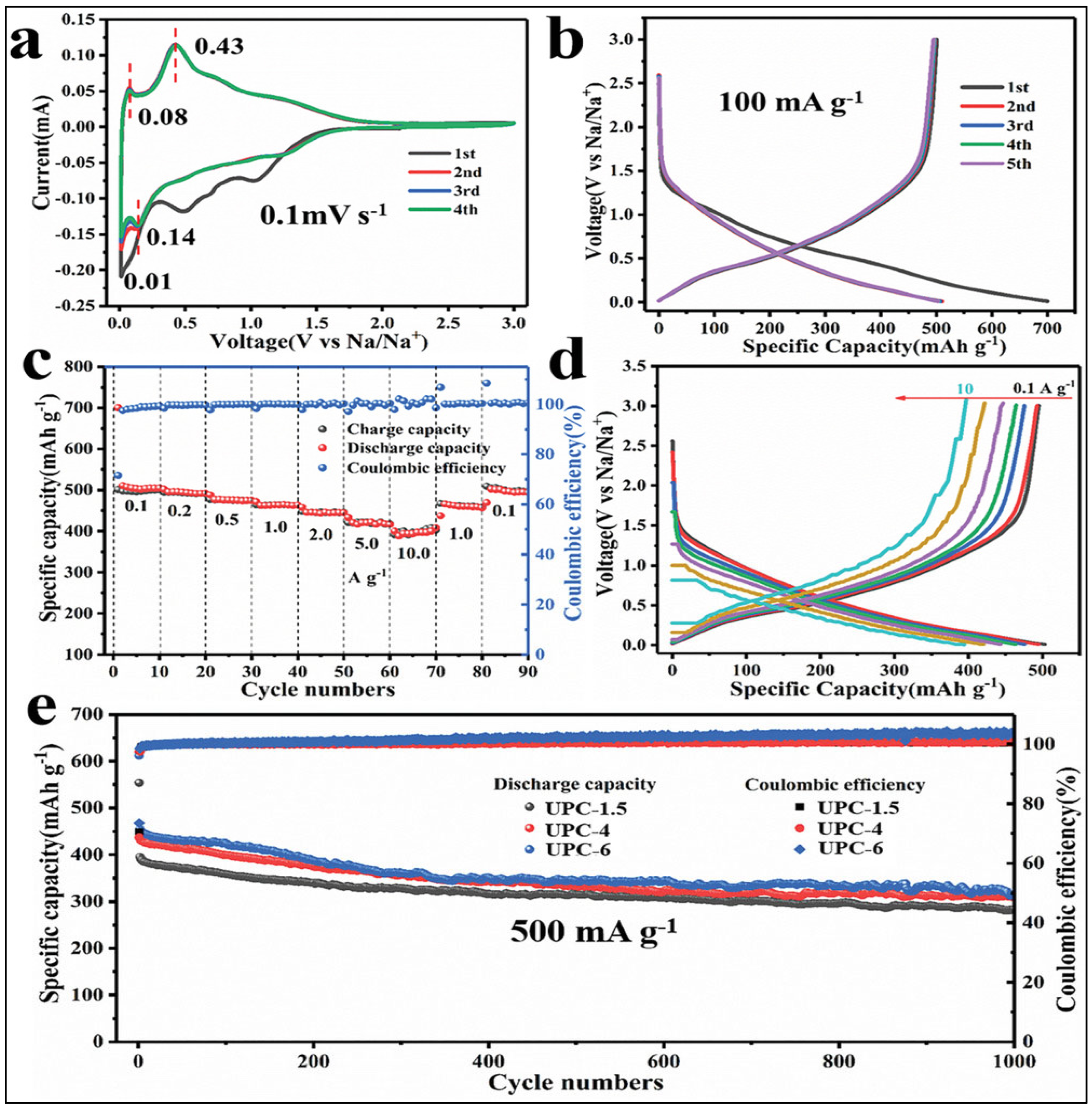

7.3. Hard Carbon-Based Anode for SIBs

7.4. Hard Carbon-Based Anode for KIBs

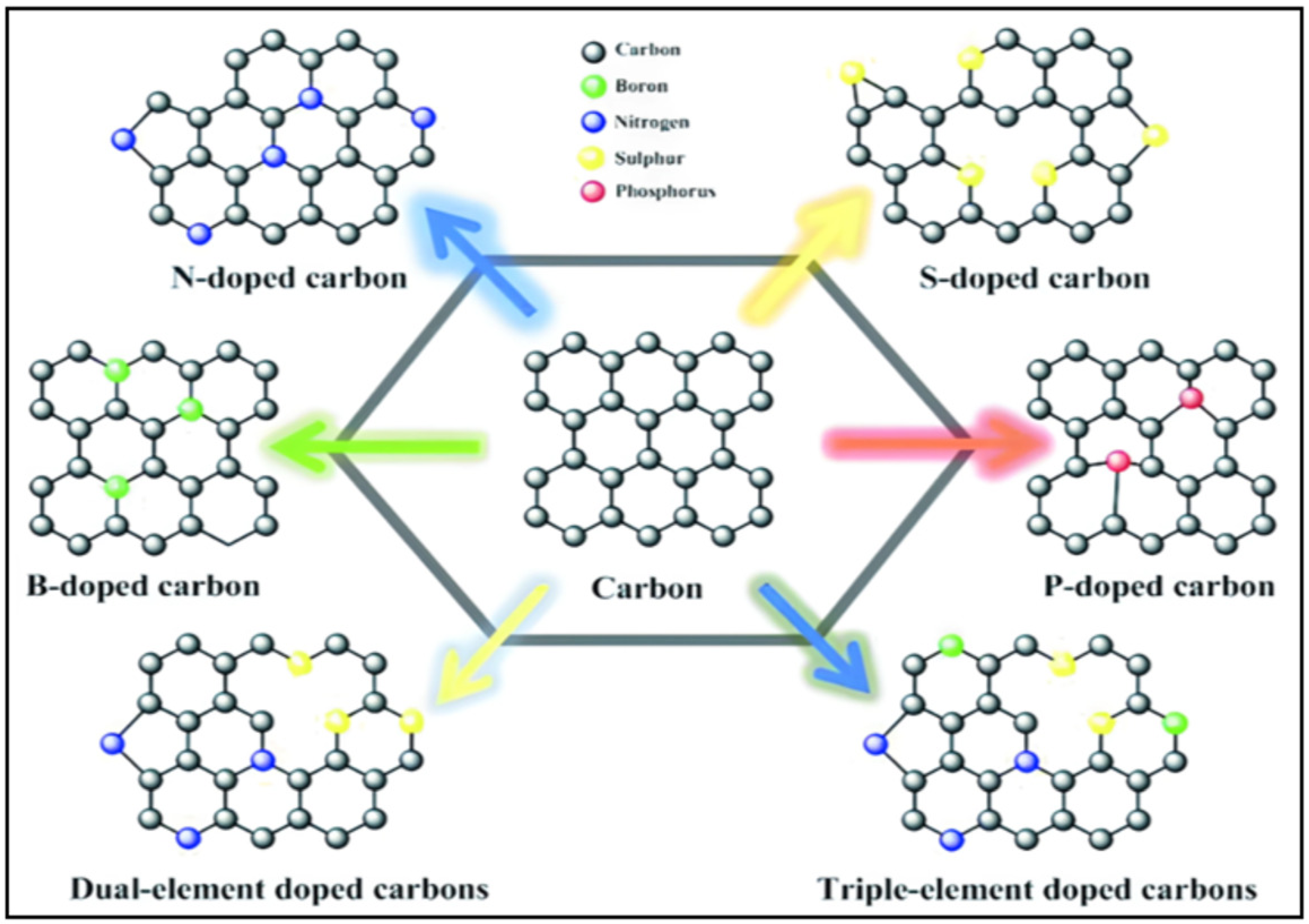

8. Heteroatom-Doped Carbon Materials as an Anode

8.1. Synthesis of Heteroatom-Doped Carbon-Based Materials

8.1.1. Pyrolysis Method

8.1.2. Carbonization of Mixed Precursors

8.1.3. CVD Method

8.1.4. Electrospinning Method

8.1.5. Post-Doping Method

8.2. NC as Anode

8.3. SC as Anode

8.4. Boron-Doped Carbon (BC) as an Anode

8.5. PC as an Anode

9. Carbon-Based Composite Materials as an Anode for MIBs

9.1. Synthesis of Carbon-Based Composite Materials

9.1.1. CVD Method

9.1.2. Hydrothermal Method

9.1.3. Ball Milling Method

9.1.4. Arc-Discharge Method

9.2. Carbon-Based Composite Anode for LIBs

9.3. Carbon-Based Composite Anode for SIBs

9.4. Carbon-Based Composite Anode for KIBs

10. Summary and Future Prospects

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amiri, N.; Yacoubi, M.; Messouli, M. Population projections, food consumption, and agricultural production are used to optimize agriculture under climatic constraints. In Intelligent Solutions for Optimizing Agriculture and Tackling Climate Change: Current and Future Dimensions; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 169–192. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee, S.; Topal, E. When will fossil fuel reserves be diminished? Energy Policy 2009, 37, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, D.; Eby, M.; Brovkin, V.; Ridgwell, A.; Cao, L.; Mikolajewicz, U.; Caldeira, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Munhoven, G.; Montenegro, A.; et al. Atmospheric Lifetime of Fossil Fuel Carbon Dioxide. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2009, 37, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, W.F.; Wiedmann, T.; Pongratz, J.; Andrew, R.; Crippa, M.; Olivier, J.G.J.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Mattioli, G.; Al Khourdajie, A.; House, J.; et al. A review of trends and drivers of greenhouse gas emissions by sector from 1990 to 2018. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 073005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.G.; Xiao, Y.; Zou, Y.Q.; Dai, L.M. Carbon-Based Metal-Free Electrocatalysis for Energy Conversion, Energy Storage, and Environmental Protection. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2018, 1, 84–112, Correction in Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2018, 1, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellabban, O.; Abu-Rub, H.; Blaabjerg, F. Renewable energy resources: Current status, future prospects and their enabling technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.; Brodd, R.J. What are batteries, fuel cells, and supercapacitors? Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4245–4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.W.; Li, W.C.; Ju, M.H.; Liu, Y.; Rao, Q.Q.; Zhou, K.; Ai, F.R. Nitrogen-Rich Multilayered Porous Carbon for an Efficient and Stable Anode. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xi, G. Preparation and electrochemical performance of LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries from spent mixed alkaline batteries. J. Electron. Mater. 2016, 45, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.; Li, L.; Xia, Y.; Huang, H.; Gan, Y.; Liang, C.; He, X.; Tao, X.; Zhang, W. Unraveling the intra and intercycle interfacial evolution of Li6PS5Cl-based all-solid-state lithium batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1903311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhu, B.; Lu, Z.; Liu, N.; Zhu, J. Challenges and recent progress in the development of Si anode for lithium-ion battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinadh, S.V.; Phanendra, P.V.R.L.; Anoopkumar, V.; John, B.; Mercy, T.D. Progress, challenges, and perspectives on alloy-based anode materials for lithium ion battery: A mini-review. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 17253–17277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Yan, B.; Xiong, D.; Li, D.; Lawes, S.; Sun, X. Recent developments and understanding of novel mixed transition-metal oxides as anode in lithium ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1502175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Han, J.; Zhang, C.; Ling, G.; Kang, F.; Yang, Q.H. Dimensionality, function and performance of carbon materials in energy storage devices. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Shi, H.; Das, P.; Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Su, F.; Wen, P.; Li, S.; Lu, P. The chemistry and promising applications of graphene and porous graphene materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Fang, S.; Hu, Y.H. 3D graphene materials: From understanding to design and synthesis control. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 10336–10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Roy, S.; Hou, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y. Recent progress in amorphous carbon-based materials for anode of sodium-ion batteries: Synthesis strategies, mechanisms, and performance. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 3693–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Shao, Y.; Mei, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Sun, J.-k.; Matyjaszewski, K.; Antonietti, M.; Yuan, J. Polymer-derived heteroatom-doped porous carbon materials. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 9363–9419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Dai, L. Doping of carbon materials for metal-free electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1804672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Wang, Y.T.; Xu, T.J.; Chang, P. Research progress on carbon materials as negative electrodes in sodium-and potassium-ion batteries. Carbon Energy 2022, 4, 1182–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, E.N.; Bobyleva, Z.V.; Drozhzhin, O.A.; Abakumov, A.M.; Antipov, E.V. Hard carbon as anode material for metal-ion batteries. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Xue, Y.-H. Carbon nanomaterials for stabilizing zinc anode in zinc-ion batteries. New Carbon Mater. 2023, 38, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.; Hou, H.; Foster, C.W.; Banks, C.E.; Guo, T.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, X. Advanced Hierarchical Vesicular Carbon Co-Doped with S, P, N for High-Rate Sodium Storage. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.; Dahn, J. High capacity anode materials for rechargeable sodium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2000, 147, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yu, M.; Feng, X. Carbon materials for ion-intercalation involved rechargeable battery technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2388–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, L.; Chen, W.; Xiong, X.; Hu, C.; Zou, F.; Hu, P.; Huang, Y. Sulfur-doped carbon with enlarged interlayer distance as a high-performance anode material for sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 2015, 2, 1500195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; He, K.; Zhu, Y.; Han, F.; Xu, Y.; Matsuda, I.; Ishii, Y.; Cumings, J.; Wang, C. Expanded graphite as superior anode for sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, A.; Sanechika, K.; Nakajima, T. Secondary Battery. U.S. Patent 4,668,595, 26 May 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Adelhelm, P.; Titirici, M.-M.; Hu, Y.-S. Intercalation chemistry of graphite: Alkali metal ions and beyond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4655–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurbach, D.; Markovsky, B.; Shechter, A.; Ein-Eli, Y.; Cohen, H. A comparative study of synthetic graphite and Li electrodes in electrolyte solutions based on ethylene carbonate-dimethyl carbonate mixtures. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1996, 143, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Subramanyam, S. Properties, and Applications. In Electrical and Optical Polymer Systems: Fundamentals: Methods, and Application; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998; p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Zhuang, Q.; Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Chen, J.; Lu, F.; Sun, S. Mechanism of intercalation and deintercalation of lithium ions in graphene nanosheets. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 56, 3204–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qiu, L.; Cheng, H.-M. Carbon-based fibers for advanced electrochemical energy storage devices. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 2811–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothandam, G.; Singh, G.; Guan, X.; Lee, J.M.; Ramadass, K.; Joseph, S.; Benzigar, M.; Karakoti, A.; Yi, J.; Kumar, P. Recent advances in carbon-based electrodes for energy storage and conversion. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2301045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Dou, Y.; Wei, Z.; Ma, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Dou, S. Recent progress in graphite intercalation compounds for rechargeable metal (Li, Na, K, Al)-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1700146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, P.; Zheng, C.; He, J.; Tu, X.; Sun, W.; Pan, H.; Zhou, Y.; Rui, X.; Zhang, B.; Huang, K. Structural engineering in graphite-based metal-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Zhou, X. The preparation of porous graphite and its application in lithium ion batteries as anode material. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2016, 20, 2613–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Peng, K.; Ji, N.; Zhang, W.; Tian, W.; Gao, Z. Advanced mechanisms and applications of microwave-assisted synthesis of carbon-based materials: A brief review. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, A.; Latifi, M.; Chaouki, J. Electrification of materials processing via microwave irradiation: A review of mechanism and applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 193, 117003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, P.; Gurzęda, B.; Bachar, A.; Buchwald, T. Formation of a N2O5—Graphite intercalation compound by ozone treatment of natural graphite. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 5463–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Sundararajan, A.; Omprakash, P.; Panemangalore, D.B. Energy Storage through Graphite Intercalation Compounds. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 040541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Sahoo, S.; Joanni, E.; Singh, R.K.; Kar, K.K. Microwave as a tool for synthesis of carbon-based electrodes for energy storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 14, 20306–20325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, C.; Huang, H.; Guo, W.; Zhao, C.; Ren, W.; Xie, Y.; Qiu, J. Energy accumulation enabling fast synthesis of intercalated graphite and operando decoupling for lithium storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priecel, P.; Lopez-Sanchez, J.A. Advantages and limitations of microwave reactors: From chemical synthesis to the catalytic valorization of biobased chemicals. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 7, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumdani, M.; Islam, M.; Yahaya, A.; Safie, S. Recent advances of the graphite exfoliation processes and structural modification of graphene: A review. J. Nanopart. Res. 2021, 23, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, R.; Bhattacharya, M.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Bhowmick, A.K. A review on the mechanical and electrical properties of graphite and modified graphite reinforced polymer composites. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 638–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viculis, L.M.; Mack, J.J.; Mayer, O.M.; Hahn, H.T.; Kaner, R.B. Intercalation and exfoliation routes to graphite nanoplatelets. J. Mater. Chem. 2005, 15, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Xing, L.; Zhang, Q.; Pu, J. Ultrasonic-assisted method of graphite preparation from wheat straw. Bioresources 2017, 12, 6405–6417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Duarte, J.; Robles-Hernández, F.C.; Gomez-Esparza, C.D.; Miranda-Hernández, J.G.; Garay-Reyes, C.G.; Estrada-Guel, I.; Martínez-Sánchez, R. Exfoliated graphite preparation based on an eco-friendly mechanochemical route. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Ahmed, H.; Adebayo, P.; Carter, R.; Khanal, L. Mechanical properties and application of graphite and graphite-based nanocomposite: A review. Chem. Mater. Res. 2023, 15, 10–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cravotto, G.; Cintas, P. Sonication-assisted fabrication and post-synthetic modifications of graphene-like materials. Chem. A Eur. J. 2010, 16, 5246–5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y. Energy consumption calculation and energy-saving measures of substation based on Multi-objective artificial bee colony algorithm. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 2024, 25, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevalov, Y.; Kozulina, T.; Yermekova, M.; Demidovich, V. Digital Shadow Induction Furnace for Heating Carbon Fibers. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ElConRus), St. Petersburg, Russia, 26–29 January 2021; pp. 1027–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Yao, Z.; Shi, Y.; Hu, J. Study on temperature field induced in high frequency induction heating. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2006, 19, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A.; Ziegler, K.; Amsharov, K.Y.; Jansen, M. In Situ Synthesis of Chlorinated Fullerenes by the High-Frequency Furnace Method; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, B.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y. Synthesis of high-quality single-walled carbon nanotubes by high-frequency-induction heating. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2008, 40, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Abuzairi, T. Sustainable graphene production: Flash joule heating utilizing pencil graphite precursors. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Gu, J.; Kang, D.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, D. Highly porous graphitic materials prepared by catalytic graphitization. Carbon 2013, 64, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, X.; Gan, L.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Du, H. Design and Numerical Study of Induction-Heating Graphitization Furnace Based on Graphene Coils. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adham, K.; Bowes, G. Natural graphite purification through chlorination in fluidized bed reactor. In Proceedings of the Extraction 2018: First Global Conference on Extractive Metallurgy, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 26–29 August 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Feng, H.; Li, J. Graphene oxide: Preparation, functionalization, and electrochemical applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 6027–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Qu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ren, G. Mechanism of oxidization of graphite to graphene oxide by the hummers method. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 23503–23510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, W.C.H.; Zafar, M.A.; Allende, S.; Jacob, M.V.; Tuladhar, R. Sustainable synthesis of graphene oxide from waste sources: A comprehensive review of methods and applications. Mater. Circ. Econ. 2024, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannov, A.; Manakhov, A.; Shibaev, A.; Ukhina, A.; Polčák, J.; Maksimovskii, E. Synthesis dynamics of graphite oxide. Thermochim. Acta 2018, 663, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Iwashita, N.; Kouno, E. Potential change with intercalation of sulfuric acid into graphite by chemical oxidation. Carbon 1990, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin-Lopez, M.d.P.; Romero, A.; Garrido, J.; Sanchez-Silva, L.; Valverde, J.L. Influence of different improved hummers method modifications on the characteristics of graphite oxide in order to make a more easily scalable method. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 12836–12847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuanyshbekov, T.; Akatan, K.; Kabdrakhmanova, S.; Nemkaeva, R.; Aitzhanov, M.; Imasheva, A.; Kairatuly, E. Synthesis of Graphene Oxide from Graphite by the Hummers Method. Oxid. Commun. 2021, 44, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, N.; Lochab, B. A comparative study of graphene oxide: Hummers, intermediate and improved method. FlatChem 2019, 13, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.-Z.; Zhao, D.-L.; Zhang, T.-M.; Xie, W.-G.; Zhang, J.-M.; Shen, Z.-M. A comparative study of electrochemical performance of graphene sheets, expanded graphite and natural graphite as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 107, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yi, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y. Graphite Intercalation Compounds (GICs): A New Type of Promising Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2014, 4, 1300600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, H.; Wu, Z.-S. Recent status, key strategies and challenging perspectives of fast-charging graphite anode for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 4834–4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Xu, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, S.; Fang, S.; Li, Y.; Sun, X. Holey graphite: A promising anode material with ultrahigh storage for lithium-ion battery. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 346, 136244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhao, R.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Sun, Y.; Wu, F.; Wu, C. Multi-ion strategies toward advanced rechargeable batteries: Materials, properties, and prospects. Energy Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 0109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, B. Decoupling KOH Activation Path to Construct Graphitic Porous Carbon Anode for Enhanced Potassium Ion Storage. Small 2025, 21, 2505910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Dou, S. Activated carbon from the graphite with increased rate capability for the potassium ion battery. Carbon 2017, 123, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.-H.; Lee, S. Characterization of graphite etched with potassium hydroxide and its application in fast-rechargeable lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2016, 324, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiboure, A.; Delmas, C.; Hagenmuller, P. Electrochemical intercalation and deintercalation of NaxMnO2 bronzes. J. Solid State Chem. 1985, 57, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.L.; Nazar, L.F. Sodium and sodium-ion energy storage batteries. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2012, 16, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liang, X.; Xiang, H. Recent developments in carbon-based materials as high-rate anode for sodium ion batteries. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 4089–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayambuka, K.; Mulder, G.; Danilov, D.L.; Notten, P.H. From li-ion batteries toward Na-ion chemistries: Challenges and opportunities. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2001310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chua, D.H.; Lee, P.S. The advances of metal sulfides and in situ characterization methods beyond Li ion batteries: Sodium, potassium, and aluminum ion batteries. Small Methods 2020, 4, 1900648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, H.M.; Cai, Q. Atomic-scale design of anode materials for alkali metal (Li/Na/K)-ion batteries: Progress and perspectives. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Dou, S.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Deng, Y.; Chen, Y. Development of metal and metal-based composites anode materials for potassium-ion batteries. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2021, 27, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nason, C.A.; Vijaya Kumar Saroja, A.P.; Lu, Y.; Wei, R.; Han, Y.; Xu, Y. Layered potassium titanium niobate/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite as a potassium-ion battery anode. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, T.; Guo, Z. Metal chalcogenides for potassium storage. InfoMat 2020, 2, 437–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Schwingenschlögl, U. Exploration of the two-dimensional transition metal phosphide MoP2 as anode for Na/K ion batteries. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2024, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, Y.; Xing, Z.; Lam, C.W.K.; Pang, S.S.; Zhang, W.; Ju, Z. Advanced carbon-based anode for potassium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1900343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, G.; Soomro, R.A.; Sun, N.; Xu, B. Advancements and prospects of graphite anode for potassium-ion batteries. Small Methods 2023, 7, 2300708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Lu, S.; Xiang, Y. Carbon anode materials: A detailed comparison between Na-ion and K-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P.; Das, A.; Jabeen Fatima, M.J. Advanced Technologies for Rechargeable Batteries: Metal Ion, Hybrid, and Metal-Air Batteries; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrato, J.M.; Barrows, C.J.; Blue, L.Y.; Lezama-Pacheco, J.S.; Bargar, J.R.; Giammar, D.E. Effect of Ca2+ and Zn2+ on UO2 dissolution rates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 2731–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurbach, D.; Skaletsky, R.; Gofer, Y. The electrochemical behavior of calcium electrodes in a few organic electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1991, 138, 3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponrouch, A.; Frontera, C.; Bardé, F.; Palacín, M.R. Towards a calcium-based rechargeable battery. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Gao, X.; Chen, Y.; Jin, L.; Kuss, C.; Bruce, P.G. Plating and stripping calcium in an organic electrolyte. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard Prabakar, S.; Ikhe, A.B.; Park, W.B.; Chung, K.C.; Park, H.; Kim, K.J.; Ahn, D.; Kwak, J.S.; Sohn, K.S.; Pyo, M. Graphite as a long-life Ca2+-intercalation anode and its implementation for rocking-chair type calcium-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1902129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Cao, F.; Pan, G.X.; Lid, C.; Chen, M.H.; Zhang, Y.Q.; He, X.P.; Xia, Y.; Xia, X.H.; Zhang, W.K. Carbon materials for metal-ion batteries. Chemphysmater 2023, 2, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Kang, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.L.; Li, Y.X.; Liang, Z.; He, X.M.; Li, X.; Tavajohi, N.; et al. A review of lithium-ion battery safety concerns: The issues, strategies, and testing standards. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 59, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Lv, C.; Bai, G.D.; Yin, Z.W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.T. A review on applications and challenges of carbon nanotubes in lithium-ion battery. Carbon Energy 2025, 7, e643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, B.J.; Ganter, M.J.; Cress, C.D.; DiLeo, R.A.; Raffaelle, R.P. Carbon nanotubes for lithium ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 638–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Kretschmer, K.; Zhang, J.; Sun, B.; Su, D.; Wang, G. Sn@ CNT nanopillars grown perpendicularly on carbon paper: A novel free-standing anode for sodium ion batteries. Nano Energy 2015, 13, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qin, R.; Liu, X.; Fang, P.; Zheng, D.; Tong, Y.; Lu, X. Dendrite-free zinc deposition induced by multifunctional CNT frameworks for stable flexible Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1903675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Han, G.; Mazari, S.A. Carbon nanotubes-based anode materials for potassium ion batteries: A review. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 907, 116051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, A.; Perri, C.; Csató, A.; Giordano, G.; Vuono, D.; Nagy, J.B. Synthesis methods of carbon nanotubes and related materials. Materials 2010, 3, 3092–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journet, C.; Maser, W.K.; Bernier, P.; Loiseau, A.; de La Chapelle, M.L.; Lefrant, D.S.; Deniard, P.; Lee, R.; Fischer, J.E. Large-scale production of single-walled carbon nanotubes by the electric-arc technique. Nature 1997, 388, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Nikolaev, P.; Rinzler, A.G.; Tomanek, D.; Colbert, D.T.; Smalley, R.E. Self-assembly of tubular fullerenes. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 10694–10697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, J.H.; Bronikowski, M.J.; Azamian, B.R.; Nikolaev, P.; Rinzler, A.G.; Colbert, D.T.; Smith, K.A.; Smalley, R.E. Catalytic growth of single-wall carbon nanotubes from metal particles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 296, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnott, S.B.; Andrews, R. Carbon nanotubes: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2001, 26, 145–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José-Yacamán, M.; Miki-Yoshida, M.; Rendón, L.; Santiesteban, J.G. Catalytic growth of carbon microtubules with fullerene structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1993, 62, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, K.B.; Singh, C.; Chhowalla, M.; Milne, W.I. Catalytic synthesis of carbon nanotubes and nanofibers. Encycl. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2003, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Journet, C.; Bernier, P. Production of carbon nanotubes. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 1998, 67, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breczko, J.; Wysocka-Żołopa, M.; Grądzka, E.; Winkler, K. Zero-Dimensional carbon nanomaterials for electrochemical energy storage. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202300752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, N.; Sakaushi, K.; Yu, L.; Giebeler, L.; Eckert, J.; Titirici, M.M. Hydrothermal carbon-based nanostructured hollow spheres as electrode materials for high-power lithium–sulfur batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 6080–6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogotsi, Y.; Libera, J.A.; Yoshimura, M. Hydrothermal synthesis of multiwall carbon nanotubes. J. Mater. Res. 2000, 15, 2591–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogotsi, Y.; Naguib, N.; Libera, J. In situ chemical experiments in carbon nanotubes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 365, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyazadeh, A.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K. Carbon nanotubes: A review of synthesis methods and applications. Reactions 2024, 5, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I.; Falath, W. Nanomaterials: A review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1821–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manafi, S.; Nadali, H.; Irani, H. Low temperature synthesis of multi-walled carbon nanotubes via a sonochemical/hydrothermal method. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 4175–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.M.C.; Swamy, S.S.; Fujino, T.; Yoshimura, M. Carbon nanocells and nanotubes grown in hydrothermal fluids. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 329, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.G.; Subramoney, S.; Foley, H.C. Spontaneous formation of carbon nanotubes and polyhedra from cesium and amorphous carbon. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 292, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.; Hare, J.; Terrones, M.; Kroto, H.; Walton, D.; Harris, P. Condensed-phase nanotubes. Nature 1995, 377, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Hamon, A.-L.; Marraud, A.; Jouffrey, B.; Zymla, V. Synthesis of SWNTs and MWNTs by a molten salt (NaCl) method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 365, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y. Synthesis and application of carbon nanotubes. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2006, 15, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobert, N. Carbon nanotubes–becoming clean. Mater. Today 2007, 10, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselova, I.; Oliinyk, N.; Volkov, S.; Konchits, A.; Yanchuk, I.; Yefanov, V.; Kolesnik, S.; Karpets, M. Electrolytic synthesis of carbon nanotubes from carbon dioxide in molten salts and their characterization. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2008, 40, 2231–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusman, E.; Nulu, A.; Sohn, K.Y. N-doped CNT assisted GeO-Ge nanoparticles as a high-capacity and durable anode material for lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 28841–28852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Sun, X.L.; Liao, Z.Q.; Lu, X.Y.; Zhang, L.; Hao, G.P. Nitrogen and boron doped carbon layer coated multiwall carbon nanotubes as high performance anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samet, M.A.M.M.; Burgaz, E. Improving the lithium-ion diffusion and electrical conductivity of LiFePO4 cathode material by doping magnesium and multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Alloy Compd. 2023, 947, 169680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, S.A.; Mohajerzadeh, S.; Sanaee, Z. Flaky sputtered silicon MWCNTs core-shell structure as a freestanding binder-free electrode for lithium-ion battery. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Deng, K.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, T.T.; Liu, P.; Lv, X.B.; Tian, W.; Ji, J.Y. One-step growth of the interconnected carbon nanotubes/graphene hybrids from cuttlebone-derived bi-functional catalyst for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 149, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doñoro, A.; Muñoz-Mauricio, A.; Etacheri, V. High-Performance Lithium Sulfur Batteries Based on Multidimensional Graphene-CNT-Nanosulfur Hybrid Cathodes. Batteries 2021, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Gao, J.; Sun, X.L.; Zhao, Q.; Si, W.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhao, F.H.; Ohsaka, T.; et al. Synergistic Defect Engineering and Interface Stability of Activated Carbon Nanotubes Enabling Ultralong Lifespan All-Solid-State Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 40496–40507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.Z.; Chen, M.X.; Cheng, L.F.; Hu, Z.Y.; Guo, S.Y.; Yuan, Y.B.; Ren, S.X.; Yu, Z.X.; Chai, Y.L.; Huang, X. Multidimensional, Superflexible, and Binder-free CNT-rGO/Si Buckypaper as Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries and Electrochemical Performance. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 9194–9206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, C.; Fan, Z.; Hao, L.; Pan, L.J. Facile fabrication of binder-free carbon nanotube-carbon nanocoil hybrid films for anode of lithium-ion batteries. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2024, 28, 3325–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Baek, I.G.; Nyamaa, O.; Goo, K.M.; Uyanga, N.; Kim, K.S.; Nam, T.H.; Yang, J.H.; Noh, J.P. Flexible, binder-free, freestanding silicon/oxidized carbon nanotubes composite anode for lithium-ion batteries with enhanced electrochemical performance through chemical reduction. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 313, 117971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.; Han, J.H.; Seo, S.B.; Choi, Y.R.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.A. Perspective on carbon nanotubes as conducting agent in lithium-ion batteries: The status and future challenges. Carbon Lett. 2023, 33, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Sheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Ni, J.F.; Li, Y. Carbon nanotubes for flexible batteries: Recent progress and future perspective. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwaa261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wu, N.N.; Yu, G.C.; Li, T. Recent Advances in Anode Materials for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Inorganics 2023, 11, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, S.Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Zhang, D.D.; Jiang, G.D.; Xiong, J.; Yuan, S.D. Co-oxidation GN/CNT 3D network enhances the cathode performance of NVPF@O-GN/CNT sodium-ion battery. Ionics 2025, 31, 10449–10460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, T.R.; Zettsu, N. Conductive 3D SW-/MW-CNTs hybrid frameworks for ultra-high-content Prussian white cathodes in sodium-ion batteries. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 6931–6943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.R.; Zhang, Z.H.; Chen, D.Q.; Yu, H.S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.F. Spray-Drying Synthesis of Na4Fe3(PO4)2P2O7@CNT Cathode for Ultra-Stable and High-Rate Sodium-Ion Batteries. Molecules 2025, 30, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, H.; Liu, L.X.; Yan, X.C.; Long, Y.Z.; Han, W.P. Amorphous FeO Anchored on N-Doped Graphene with Internal Micro-Channels as an Active and Durable Anode for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.G.; Lu, Z.Y.; Guo, S.H.; Yang, Q.H.; Zhou, H.S. Toward High Performance Anode for Sodium-Ion Batteries: From Hard Carbons to Anode-Free Systems. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.X.; Li, Z.Y.; Ruan, H.L.; Luo, D.W.; Wang, J.J.; Ding, Z.Y.; Chen, L.N. A Review of Carbon Anode Materials for Sodium-Ion Batteries: Key Materials, Sodium-Storage Mechanisms, Applications, and Large-Scale Design Principles. Molecules 2024, 29, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Saleem, S.; Ali, S.; Abbas, S.M.; Choi, M.; Choi, W. Recent advances in alloying anode materials for sodium-ion batteries: Material design and prospects. Energy Mater. 2024, 4, 400068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.X.; Liu, C.F.; Neale, Z.G.; Yang, J.H.; Cao, G.Z. Active Materials for Aqueous Zinc Ion Batteries: Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Morphology, and Electrochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7795–7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Tao, Y.; Fei, H.; An, Y.; Tian, Y.; Feng, J.; Qian, Y. Recent advances and perspectives in stable and dendrite-free potassium metal anode. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 30, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.M.; Huang, Z.Q.; Sun, S.Q.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, W.J.; Yu, G.X.; Chen, J. A Flexible Multi-Channel Hollow CNT/Carbon Nanofiber Composites with S/N Co-Doping for Sodium/Potassium Ion Energy Storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 44369–44378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Qi, E.; Sun, M.Z.; Wei, Z.X.; Jiang, H.; Du, F. Unlocking the potential of potassium-ion batteries: Anode material mechanisms, challenges, and future directions. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 19021–19054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.L.; Zhao, H.P.; Lei, Y. Recent Research Progress of Anode Materials for Potassium-ion Batteries. Energy Environ. Mater. 2020, 3, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Li, Y.A.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.J.; Wang, H.; Wang, B.; Wu, Y.S.; Wu, Y.M.A. A comprehensive review of carbon anode materials for potassium-ion batteries based on specific optimization strategies. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 2547–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Wang, H.W.; Zang, X.B.; Zhai, D.Y.; Kang, F.Y. Recent Advances in Stability of Carbon-Based Anode for Potassium-Ion Batteries. Batter. Supercaps 2021, 4, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.K.; Ahmed, M.S.; Park, J.; Prabakaran, R.; Sidney, S.; Sathyamurthy, R.; Kim, S.C.; Periasamy, S.; Kim, J.; Hwang, J.Y. A review on carbon nanomaterials for K-ion battery anode: Progress and perspectives. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 4033–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Q.; Sun, D.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H. Improving the initial coulombic efficiency of carbonaceous materials for Li/Na-ion batteries: Origins, solutions, and perspectives. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2023, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ji, C.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, X. Red@ Black phosphorus core–shell heterostructure with superior air stability for high-rate and durable sodium-ion battery. Mater. Today 2022, 59, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, X.; Pan, Z.; Rao, X.; Gu, Y. The progress of hard carbon as an anode material in sodium-ion batteries. Molecules 2023, 28, 3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Jin, Y.; Sun, S.; Huang, Y.; Peng, J.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Fang, C.; Han, J. Low-cost and high-performance hard carbon anode materials for sodium-ion batteries. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 1687–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dai, G.; Yang, H.; Luo, Z. Lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis mechanism: A state-of-the-art review. Progress Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 62, 33–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, B.; Xie, W.-l.; Jiang, X.-y.; Liu, J.; Lu, Q. Recent progress in quantum chemistry modeling on the pyrolysis mechanisms of lignocellulosic biomass. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 10384–10440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahbi, M.; Kiso, M.; Kubota, K.; Horiba, T.; Chafik, T.; Hida, K.; Matsuyama, T.; Komaba, S. Synthesis of hard carbon from argan shells for Na-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 9917–9928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Lu, H.; Fang, Y.; Sushko, M.L.; Cao, Y.; Ai, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, J. Low-defect and low-porosity hard carbon with high coulombic efficiency and high capacity for practical sodium ion battery anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Guo, Z.; Hong, Z.; Titirici, M.-M. Ultrafast synthesis of hard carbon anode for sodium-ion batteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2111119118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Chen, Y.; Tong, L.; Cao, Y.; Jiao, H.; Qiu, X. Biomass hard carbon of high initial coulombic efficiency for sodium-ion batteries: Preparation and application. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 410, 140017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchamsetti, N.; Kim, K.-H.; Han, H.; Mhin, S. Biomass-Derived Hard Carbon Anode for Sodium-Ion Batteries: Recent Advances in Synthesis Strategies. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X. A sustainable route from corn stalks to N, P-dual doping carbon sheets toward high performance sodium-ion batteries anode. Carbon 2018, 130, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ghimbeu, C.M.; Laberty, C.; Vix-Guterl, C.; Tarascon, J.M. Correlation between microstructure and Na storage behavior in hard carbon. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1501588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, X.; Qiu, X.; Cao, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Y. Extended low-voltage plateau capacity of hard carbon spheres anode for sodium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2020, 476, 228550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhang, R.; Luo, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, J. Epoxy phenol novolac resin: A novel precursor to construct high performance hard carbon anode toward enhanced sodium-ion batteries. Carbon 2023, 205, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Qi, X.; Qi, Y.; Li, H.; Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Hu, Y.S. Pre-oxidation-tuned microstructures of carbon anode derived from pitch for enhancing Na storage performance. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1800108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tian, J.; Li, P.; Fang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liang, X.; Feng, J.; Dong, J.; Ai, X.; Yang, H. An overall understanding of sodium storage behaviors in hard carbons by an “adsorption-intercalation/filling” hybrid mechanism. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Q.; Liu, D.; Wang, B. Unraveling the mechanism of sodium storage in low potential region of hard carbons with different microstructures. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 67, 103269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-W.; Lv, W.; Luo, C.; You, C.-H.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Z.-Z.; Kang, F.-Y.; Yang, Q.-H. Commercial carbon molecular sieves as a high performance anode for sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2016, 3, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, A.; Kubota, K.; Igarashi, D.; Youn, Y.; Tateyama, Y.; Ando, H.; Gotoh, K.; Komaba, S. MgO-template synthesis of extremely high capacity hard carbon for Na-ion battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 5114–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Lu, Z.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Roy, S.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Enabling fast Na+ transfer kinetics in the whole-voltage-region of hard-carbon anode for ultrahigh-rate sodium storage. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Duan, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Engineering ultrathin carbon layer on porous hard carbon boosts sodium storage with high initial coulombic efficiency. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 19063–19075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Guo, Y.; Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Qin, L.; Ning, T.; Tan, L.; Li, L.; Zou, K. Heteroatom doping strategy of advanced carbon for alkali Metal-Ion capacitors. Batteries 2025, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Lei, C.; Qiu, H.; Jiang, W.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, W. P-doped hard carbon material for anode of sodium ion battery was prepared by using polyphosphoric acid modified petroleum asphalt as precursor. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 477, 143812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Tang, C.; Bi, Z.; Song, M.; Fan, Y.; Yan, C.; Li, X.; Su, F.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, C. Hard carbon anode for next-generation Li-ion batteries: Review and perspective. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zheng, J.; Adams, D.; Zheng, J.P. Comparative study of the power performance for advanced Li-ion capacitors with various carbon anode. ECS Trans. 2014, 61, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tian, Y.; Abdussalam, A.; Gilani, M.R.H.S.; Zhang, W.; Xu, G. Hard carbons as anode in sodium-ion batteries: Sodium storage mechanism and optimization strategies. Molecules 2022, 27, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, T.; Zhou, S.; Yang, S.; Ismail, S.A.; Ali, T.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Gao, L. Progress in 3D-MXene electrodes for lithium/sodium/potassium/magnesium/zinc/aluminum-ion batteries. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2023, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.; Fouletier, M. Electrochemical intercalation of sodium in graphite. Solid State Ion. 1988, 28, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaalma, C.; Buchholz, D.; Weil, M.; Passerini, S. A cost and resource analysis of sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 18013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Luo, K.; Song, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhong, B.; Wu, Z.; Guo, X. Hard carbon for sodium storage: Mechanism and optimization strategies toward commercialization. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 2244–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, J.; Biney, B.W.; Yan, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Xia, W.; Liu, D.; Chen, K. Innovative synthesis and sodium storage enhancement of closed-pore hard carbon for sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2025, 74, 103867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhang, B. Advanced lignin-derived hard carbon for Na-ion batteries and a comparison with Li and K ion storage. Carbon 2020, 157, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; Qi, J.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, G. Hard Carbon as Anode for Potassium-Ion Batteries: Developments and Prospects. Inorganics 2024, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hyun, J.C.; Jung, J.I.; Lee, J.B.; Choi, J.; Cho, S.Y.; Jin, H.-J.; Yun, Y.S. Potassium-ion storage behavior of microstructure-engineered hard carbons. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 2055–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Zhang, W.; Sun, S.; Zhao, L.; Jian, W.; He, X.; Xing, Z.; Shi, Z.; Chen, Y.; Alshareef, H.N. Engineering of the crystalline lattice of hard carbon anode toward practical potassium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2211872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Ji, Z.; Wang, Z.; Pan, L.; Tan, S.; Mai, W. A review of hard carbon anode: Rational design and advanced characterization in potassium ion batteries. InfoMat 2022, 4, e12272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Dong, R.Q.; Bai, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, G.H.; Wang, Z.H.; Wu, C. Phosphorus-Doped Hard Carbon Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning as an Anode in Sodium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 21335–21342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, M.H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, X.Q.; Xia, X.H. Heteroatom Doping: An Effective Way to Boost Sodium Ion Storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2000927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.M.; Wan, M.; Liu, Q.; Xiong, X.Q.; Yu, F.Q.; Huang, Y.H. Heteroatom-Doped Carbon Materials: Synthesis, Mechanism, and Application for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Small Methods 2019, 3, 1800323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, X.; Xu, J.T.; Liu, H.K.; Ma, J.M.; Dou, S.X. Growth of Highly Nitrogen-Doped Amorphous Carbon for Lithium-ion Battery Anode. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 188, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, C.L.; Dou, S.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, J.T.; Gao, X.; Ma, J.M.; Yu, Y. Nitrogen-doped hierarchically porous carbon networks: Synthesis and applications in lithium-ion battery, sodium-ion battery and zinc-air battery. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 219, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, U.; Sogabe, T.; Sakagoshi, H.; Ito, M.; Tojo, T. Anode property of boron-doped graphite materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. Carbon 2001, 39, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.Y.; Xiang, Z.H.; Huang, K.S.; Ju, Z.C.; Zhuang, Q.C.; Cui, Y.H. Graphene-Based Phosphorus-Doped Carbon as Anode Material for High-Performance Sodium-Ion Batteries. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2017, 34, 1600315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.M.; Zhuang, R.; Du, Y.X.; Pei, Y.W.; Tan, D.M.; Xu, F. Advances in sulfur-doped carbon materials for use as anode in sodium-ion batteries. New Carbon Mater. 2023, 38, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, H.; Meng, X.B.; Yang, J.L.; Geng, D.S.; Wang, D.N.; Li, R.Y.; et al. High concentration nitrogen doped carbon nanotube anode with superior Li storage performance for lithium rechargeable battery application. J. Power Sources 2012, 197, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, M.; Ghazvini, A.A.S.; Shahalizade, T.; Gaho, M.A.; Mumtaz, A.; Javanmardi, S.; Riahifar, R.; Meng, X.M.; Jin, Z.; Ge, Q. A review of nitrogen-doped carbon materials for lithium-ion battery anode. New Carbon Mater. 2023, 38, 247–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, H.M.; Wang, K.L.; Jin, Q.Z.; Lai, C.L.; Wang, R.X.; Cao, S.L.; Han, J.; Zhang, Z.C.; Su, J.Z.; et al. Ultrahigh Phosphorus Doping of Carbon for High-Rate Sodium Ion Batteries Anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommier, C.; Mitlin, D.; Ji, X.L. Internal structure—Na storage mechanisms—Electrochemical performance relations in carbons. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 97, 170–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, T.; Hessdörfer, J.; Bilican, A.; Kolb, L.; Reinert, F.; Krueger, A. Superior sulfur-doped carbon anode for sodium-ion batteries through incorporation of onion-like carbon. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 537, 146912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.X.; Pan, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.J.; Peng, H.S. The recent progress of nitrogen-doped carbon nanomaterials for electrochemical batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 12932–12944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, I.Y.; Noh, H.J.; Baek, J.B. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Characteristics and Applications. Chem-Asian J. 2020, 15, 2282–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D.C.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Huang, L.P.; Yu, G. Synthesis of N-Doped Graphene by Chemical Vapor Deposition and Its Electrical Properties. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, F.Z.; Li, S.K.; Shen, Y.H.; Xie, A.J. Novel porous starfish-like Co O @nitrogen-doped carbon as an advanced anode for lithium-ion batteries. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 3457–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Martin, A.; Martinez-Fernandez, J.; Ruttert, M.; Winter, M.; Placke, T.; Ramirez-Rico, J. An electrochemical evaluation of nitrogen-doped carbons as anode for lithium ion batteries. Carbon 2020, 164, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.P.; Ren, X.H.; Ai, Q.; Sun, Q.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Peng, R.Q.; Si, P.C.; Lou, J.; et al. Facile Fabrication of Nitrogen-Doped Porous Carbon as Superior Anode Material for Potassium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1802386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.D.; Wang, S.Q.; Lian, P.C.; Zhu, X.F.; Li, D.D.; Yang, W.S.; Wang, H.H. Superhigh capacity and rate capability of high-level nitrogen-doped graphene sheets as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 90, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Kohandehghan, A.; Cui, K.; Xu, Z.; Zahiri, B.; Tan, X.; Lotfabad, E.M.; Olsen, B.C. Carbon nanosheet frameworks derived from peat moss as high performance sodium ion battery anode. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 11004–11015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, Y.J.; Kim, S.O.; Lee, J.K. Employment of boron-doped carbon materials for the anode materials of lithium ion batteries. J. Alloy Compd. 2014, 582, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshio, M.; Wang, H.Y.; Fukuda, K.; Hara, Y.; Adachi, Y. Effect of carbon coating on electrochemical performance of treated natural graphite as lithium-ion battery anode material. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2000, 147, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.C.; Pei, Y.; Yang, Z.H.; Wang, X.Y. Ab initio study of graphene-like monolayer molybdenum disulfide as a promising anode material for rechargeable sodium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 43183–43188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.J.; Hou, Z.F.; Gao, B.; Frauenheim, T. Doped graphenes as anode with large capacity for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 13407–13413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadie, N.P.; Billeter, E.; Piveteau, L.; Kravchyk, K.V.; Döbeli, M.; Kovalenko, M.V. Direct Synthesis of Bulk Boron-Doped Graphitic Carbon. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 3211–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.P.; Ozdemir, B.; Barone, V.; Peralta, J.E. Hexagonal BC: A Robust Electrode Material for Li, Na, and K Ion Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 2728–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Fujino, T.; Hayashi, T.; Endo, M.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Structural and electrochemical properties of pristine and B-doped materials for the anode of Li-ion secondary batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2000, 147, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Mizuno, F. Boron-doped graphene as a promising anode for Na-ion batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 10419–10424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, W.; Wang, H.D. First-Principles Investigation of Adsorption and Diffusion of Ions on Pristine, Defective and B-doped Graphene. Materials 2015, 8, 6163–6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buqa, H.; Würsig, A.; Vetter, J.; Spahr, M.E.; Krumeich, F.; Novák, P. SEI film formation on highly crystalline graphitic materials in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2006, 153, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, E.G.; Tilley, R.D.; Jefferson, D.A.; Zhou, W. Size-controlled short nanobells: Growth and formation mechanism. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 77, 4136–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurel, D.; Orayech, B.; Xiao, B.W.; Carriazo, D.; Li, X.L.; Rojo, T. From Charge Storage Mechanism to Performance: A Roadmap toward High Specific Energy Sodium-Ion Batteries through Carbon Anode Optimization. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.S.; Zhen, Y.C.; Ruan, Y.R.; Kang, M.L.; Zhou, K.Q.; Zhang, J.M.; Huang, Z.G.; Wei, M.D. Rational Design and General Synthesis of S-Doped Hard Carbon with Tunable Doping Sites toward Excellent Na-Ion Storage Performance. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; El-Demellawi, J.K.; Sheng, G.; Bjoerk, J.; Zeng, F.S.; Zhou, J.; Liao, X.X.; Wu, J.W.; Rosen, J.; Liu, X.J.; et al. Pseudocapacitive Heteroatom-Doped Carbon Cathode for Aluminum-Ion Batteries with Ultrahigh Reversible Stability. Energy Environ. Mater. 2024, 7, e12733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.N.; Zhao, J.M.; Li, L.L.; Dong, W. Sodium Adsorption and Intercalation in Bilayer Graphene Doped with B, N, Si and P: A First-Principles Study. J. Electron. Mater. 2020, 49, 6336–6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, W.; Feng, P.Y.; Wang, R.X.; Jiang, M.; Han, J.; Cao, S.L.; Wang, K.L.; Jiang, K. Enhanced Na pseudocapacitance in a P, S co-doped carbon anode arising from the surface modification by sulfur and phosphorus with C-S-P coupling. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.G.; Zhao, J.H.; Yao, H.; He, X.X.; Zhang, H.; Qiao, Y.; Wu, X.Q.; Li, L.; Chou, S.L. P-doped spherical hard carbon with high initial coulombic efficiency and enhanced capacity for sodium ion batteries. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 8478–8487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.H.; Shi, Q.T.; Ullah, S.; Yang, X.Q.; Bachmatiuk, A.; Yang, R.Z.; Rummeli, M.H. Phosphorus-Based Composites as Anode Materials for Advanced Alkali Metal Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2004648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.B.; Li, W.J.; Miao, Z.C.; Chou, S.L.; Liu, H.K. Phosphorus and phosphide nanomaterials for sodium-ion batteries. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 4055–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.Q.; Wei, Q.L.; Zhang, G.X.; Wang, X.M.; Zhang, J.H.; Hu, Y.F.; Wang, D.N.; Zuin, L.C.; Zhou, T.; Wu, Y.C.; et al. High-Performance Reversible Aqueous Zn-Ion Battery Based on Porous MnO Nanorods Coated by MOF-Derived N-Doped Carbon. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.Y.; Yan, B.Y.; Yu, J.; Jin, J.; Tao, Y.; Mu, C.; Wang, S.C.; Xue, H.G.; Pang, H. Phosphorus-based materials for high-performance rechargeable batteries. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 1424–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.-L.; Zhang, C.; Dong, W.-S. Synthesis of carbon/tin composite anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 159, A91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.P.; Sougrati, M.T.; Feng, Z.; Leconte, Y.; Fisher, A.; Srinivasan, M.; Xu, Z. A review on design strategies for carbon based metal oxides and sulfides nanocomposites for high performance Li and Na ion battery anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Liang, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhong, B.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, T.; Kong, Q.; Liu, Y.; Asiri, A.M. Progress and perspective of metal phosphide/carbon heterostructure anode for rechargeable ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 11879–11907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, C.; Xiong, Z.; Wu, J.; Bai, Z.; Yan, X. Scalable synthesis of a porous structure silicon/carbon composite decorated with copper as an anode for lithium ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 620, 156843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ge, R.; Lu, M.; Xu, R.; Zhang, Z. Graphene-based nano-materials for lithium–sulfur battery and sodium-ion battery. Nano Energy 2015, 15, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xu, R.; Lu, M.; Ge, R.; Iocozzia, J.; Han, C.; Jiang, B.; Lin, Z. Graphene-containing nanomaterials for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zhou, J.; Ullah, S.; Yang, X.; Tokarska, K.; Trzebicka, B.; Ta, H.Q.; Ruemmeli, M.H. A review of recent developments in Si/C composite materials for Li-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 34, 735–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.-c.; Sun, Q.; Wang, J.-t.; Ma, C.; Ling, L.-c.; Qiao, W.-m. Preparation and electrochemical properties of novel silicon-carbon composite anode materials with a core-shell structure. New Carbon Mater. 2021, 36, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.; Chae, S.; Ma, J.; Kim, N.; Lee, H.-W.; Cui, Y.; Cho, J. Scalable synthesis of silicon-nanolayer-embedded graphite for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.; Lee, C.; Tai, N. High retention supercapacitors using carbon nanomaterials/iron oxide/nickel-iron layered double hydroxides as electrodes. J. Energy Storage 2022, 46, 103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyan, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B. Tailoring carboxyl tubular carbon nanofibers/MnO2 composites for high-performance lithium-ion battery anode. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 1402–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Liu, Z.; Xu, C.; Huang, J.; Fang, H.; Chen, Y. High-rate-induced capacity evolution of mesoporous C@SnO2@C hollow nanospheres for ultra-long cycle lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2019, 414, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordyuk, B.; Prokopenko, G. Mechanical alloying of powder materials by ultrasonic milling. Ultrasonics 2004, 42, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapeng, W.; Xiaodong, L.; Minggang, Z.; Wei, L.; Min, Q. Anisotropic Sm2Co17 nano-flakes produced by surfactant and magnetic field assisted high energy ball milling. J. Rare Earths 2013, 31, 366–369. [Google Scholar]

- Gorrasi, G.; Sorrentino, A. Mechanical milling as a technology to produce structural and functional bio-nanocomposites. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 2610–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. Microwave-assisted synthesis of vanadium and chromium carbides nanocomposite and its effect on properties of WC-8Co cemented carbides. Scr. Mater. 2016, 120, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, B.; Zou, W.; Dong, L. Facile ball-milling synthesis of CuO/biochar nanocomposites for efficient removal of reactive red 120. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 5748–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bor, A.; Jargalsaikhan, B.; Lee, J.; Choi, H. Effect of different milling media for surface coating on the copper powder using two kinds of ball mills with discrete element method simulation. Coatings 2020, 10, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, J.; Krishnamoorthy, A.; Tanna, A.; Kamathe, V.; Nagar, R.; Srinivasan, S. Recent developments on the synthesis of nanocomposite materials via ball milling approach for energy storage applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, J. SnSe/carbon nanocomposite synthesized by high energy ball milling as an anode material for sodium-ion and lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 176, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charinpanitkul, T.; Soottitantawat, A.; Tonanon, N.; Tanthapanichakoon, W. Single-step synthesis of nanocomposite of copper and carbon nanoparticles using arc discharge in liquid nitrogen. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 116, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivani, D.A.; Retnosari, I.; Saraswati, T.E. Influence of TiO2 addition on the magnetic properties of carbon-based iron oxide nanocomposites synthesized using submerged arc-discharge. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, A. Nanostructured transition metal oxides as advanced anode for lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Bull. 2015, 60, 823–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, F.; Shi, L.; Chen, G.; Zhang, D. Silicon/carbon composite anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2019, 2, 149–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Cheng, Y.J.; Zhu, J.; Xia, Y.; Müller-Buschbaum, P. A chronicle review of nonsilicon (Sn, Sb, Ge)-based lithium/sodium-ion battery alloying anode. Small Methods 2020, 4, 2000218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchsbichler, B.; Stangl, C.; Kren, H.; Uhlig, F.; Koller, S. High capacity graphite–silicon composite anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 2889–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Quan, Z.; Wang, F.; Lu, A.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, W.; Tang, Z.; Dang, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C. Scalable synthesis of nano silicon-embedded graphite for high-energy and low-expansion lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 656, 238022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.G.; Wu, Q.H.; Hong, G.; Zhang, W.J.; Wu, H.; Amine, K.; Yang, J.; Lee, S.T. Silicon–Graphene Composite Anode for High-Energy Lithium Batteries. Energy Technol. 2013, 1, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Jin, H.; Zong, P.; Bai, Y.; Lian, K.; Xu, H.; Ma, F. A robust hierarchical 3D Si/CNTs composite with void and carbon shell as Li-ion battery anode. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 974–981. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, M.K.; Maranchi, J.; Chung, S.J.; Epur, R.; Kadakia, K.; Jampani, P.; Kumta, P.N. Amorphous silicon–carbon based nano-scale thin film anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 4717–4723. [Google Scholar]

- Demirkan, M.T.; Yurukcu, M.; Dursun, B.; Demir-Cakan, R.; Karabacak, T. Evaluation of double-layer density modulated Si thin films as Li-ion battery anode. Mater. Res. Express 2017, 4, 106405. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, S.; Lu, C. Research progress of silicon/carbon anode materials for lithium-ion batteries: Structure design and synthesis method. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 4289–4302. [Google Scholar]

- You, S.; Tan, H.; Wei, L.; Tan, W.; Chao Li, C. Design strategies of Si/C composite anode for lithium-ion batteries. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2021, 27, 12237–12256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, R.; Choi, J.-Y.; Song, J.-B.; Jo, M.; Lee, H.; Lee, C.-S. Characteristics and electrochemical performances of silicon/carbon nanofiber/graphene composite films as anode materials for binder-free lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzabahimana, J.; Liu, Z.; Guo, S.; Wang, L.; Hu, X. Top-down synthesis of silicon/carbon composite anode materials for lithium-ion batteries: Mechanical milling and etching. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 1923–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Lee, H.; Chae, O.B. Synthesis Methods of Si/C Composite Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries 2024, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, D.; Hou, X.; Shi, J.; Peng, Y.; Yang, H. Scalable preparation of mesoporous Silicon@ C/graphite hybrid as stable anode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy Compd. 2017, 728, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Environment-friendly synthesis of carbon-encapsulated SnO2 core-shell nanocubes as high-performance anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Mater. Today Energy 2020, 16, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Ma, X. Encapsulated Fe3O4 into tubular mesoporous carbon as a superior performance anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy Compd. 2020, 815, 152542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommier, C.; Luo, W.; Gao, W.-Y.; Greaney, A.; Ma, S.; Ji, X. Predicting capacity of hard carbon anode in sodium-ion batteries using porosity measurements. Carbon 2014, 76, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Jian, Z.; Xing, Z.; Wang, W.; Bommier, C.; Lerner, M.M.; Ji, X. Electrochemically expandable soft carbon as anode for Na-ion batteries. ACS Cent. Sci. 2015, 1, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Xiao, L.; Sushko, M.L.; Han, K.S.; Shao, Y.; Yan, M.; Liang, X.; Mai, L.; Feng, J.; Cao, Y. Manipulating adsorption–insertion mechanisms in nanostructured carbon materials for high-efficiency sodium ion storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Song, Q.; Zhang, T.; Huo, X.; Lin, Z.; Hu, Z.; Dong, L.; Jin, T.; Shen, C.; Xie, K. Growing curly graphene layer boosts hard carbon with superior sodium-ion storage. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 9299–9309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, F.; Wang, H.; Wu, D.; Chao, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhao, G. Altering thermal transformation pathway to create closed pores in coal-derived hard carbon and boosting of Na+ plateau storage for high-performance sodium-ion battery and sodium-ion capacitor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, T.Y.; Yang, H.; Min, H.; Shen, X.; Chen, H.Y.; Wang, J. Regulating Graphitic Microcrystalline and Single-Atom Chemistry in Hard Carbon Enables High-Performance Potassium Storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2309509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.; Singh, G. Reduced graphene oxide paper electrode: Opposing effect of thermal annealing on Li and Na cyclability. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 28401–28408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Ilango, P.R.; Wang, S.; Nasir, M.S.; Li, L.; Ji, D.; Hu, Y.; Ramakrishna, S.; Yan, W.; Peng, S. Carbon-based alloy-type composite anode materials toward sodium-ion batteries. Small 2019, 15, 1900628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Hasa, I.; Passerini, S. Beyond insertion for Na-ion batteries: Nanostructured alloying and conversion anode materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1702582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Jia, Z.; Chen, Y.; Weadock, N.; Wan, J.; Vaaland, O.; Han, X.; Li, T.; Hu, L. Tin anode for sodium-ion batteries using natural wood fiber as a mechanical buffer and electrolyte reservoir. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 3093–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithya, C.; Gopukumar, S. rGO/nano Sb composite: A high performance anode material for Na+ ion batteries and evidence for the formation of nanoribbons from the nano rGO sheet during galvanostatic cycling. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 10516–10525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Obrovac, M. Alloy negative electrodes for high energy density metal-ion cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, A1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, F.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Jungjohann, K.L.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Bigio, D.; Zhu, T. In situ transmission electron microscopy study of electrochemical sodiation and potassiation of carbon nanofibers. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 3445–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Ni, C.; Tian, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, S.X.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y. Reaction and capacity-fading mechanisms of tin nanoparticles in potassium-ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 12652–12657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Mao, J.; Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Z. Phosphorus-based alloy materials for advanced potassium-ion battery anode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3316–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lin, X.; Tan, H.; Zhang, B. Bismuth microparticles as advanced anode for potassium-ion battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Mao, J.; Pang, W.K.; Zheng, T.; Sencadas, V.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z. Boosting the potassium storage performance of alloy-based anode materials via electrolyte salt chemistry. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, H.B.; Feng, Y.; Wu, Z.S.; Yu, Y. The promise and challenge of phosphorus-based composites as anode materials for potassium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1901414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loaiza, L.C.; Monconduit, L.; Seznec, V. Si and Ge-based anode materials for Li-, Na-, and K-ion batteries: A perspective from structure to electrochemical mechanism. Small 2020, 16, 1905260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, I.; Ramireddy, T.; Rahman, M.M.; Chen, Y.; Glushenkov, A.M. Tin-based composite anode for potassium-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 9279–9282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Han, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Meng, J.; Xu, X.; He, Q.; Luo, W.; Wu, L. Three-dimensional carbon network confined antimony nanoparticle anode for high-capacity K-ion batteries. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 6820–6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Precursor for SC | Discharge Capacity | Charge Capacity | Cyclic Efficiency (%) | Columbic Efficiency (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT | 655.0 mAh/g at 0.1 A/g | 482.1 mAh/g at 0.1 A/g | 73.6 | 100.0 after 700 cycles | [26] |

| Polythiophene | 714.0 mAh/g at 0.05 A/g | 491.0 mAh/g at 0.05 A/g | 69.0 | 100.0 after 500 cycles | [203] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hussain, S.; Oyebade, A.; Hossain, M.R.; Abbas, F.; Siraj, N. Carbon-Based Anode Materials for Metal-Ion Batteries: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions. Batteries 2025, 11, 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120444

Hussain S, Oyebade A, Hossain MR, Abbas F, Siraj N. Carbon-Based Anode Materials for Metal-Ion Batteries: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions. Batteries. 2025; 11(12):444. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120444

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussain, Salim, Adeniyi Oyebade, Md Riyad Hossain, Fatima Abbas, and Noureen Siraj. 2025. "Carbon-Based Anode Materials for Metal-Ion Batteries: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions" Batteries 11, no. 12: 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120444

APA StyleHussain, S., Oyebade, A., Hossain, M. R., Abbas, F., & Siraj, N. (2025). Carbon-Based Anode Materials for Metal-Ion Batteries: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions. Batteries, 11(12), 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120444