Abstract

Sodium–ion battery capacitors (SIBatCs) synergistically combine battery–type and capacitor–type components in an inter–parallel configuration, simultaneously delivering high energy and power densities. We pioneer the development of quasi–commercial pouch SIBatCs using Na3V2(PO4)3/activated carbon (NVP/AC) hybrid cathodes and hard carbon anodes. The hybrid design utilizes NVP as an intrinsic sodium source, eliminating complex anode presodiation—an obstacle to industrialization. The AC component fulfills multiple roles—contributing capacitive capacity, enhancing conductivity, and acting as an electrolyte reservoir, which decreases electrode resistivity as well as polarization. In full cells, an optimal NVP/AC mass ratio range of 10:1–2:1 is identified, enabling balanced low resistance, high energy density, exceptional power density, and long cycle life. SIBatCs incorporating R10/1 (mNVP:mAC = 10:1) and R4/1 (mNVP:mAC = 4:1) achieve energy densities of 148.9 Wh kg−1 (81.0 W kg−1) and 120.6 Wh kg−1 (79.3 W kg−1), respectively. Even at ultrahigh power densities of 30.53 and 29.81 kW kg−1, they retain corresponding energy densities of 50.4 and 39.6 Wh kg−1. They exhibit excellent capacity retentions of 32.8% and 41.6% after 5000 cycles—significantly outperforming pure NVP–based cells (18.0%). The hybrid architecture ensures robust performance across a wide temperature range (−30–60 °C). This work presents a scalable solution for high–performance sodium–ion EES hybrid systems.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of increasingly pressing energy shortages and climate change, the widespread deployment of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, is of vital significance to the global community [1]. To address the intrinsic intermittency and unpredictability of renewable power generation, developing advanced electrochemical energy storage (EES) systems has become a critical research priority [2]. Among EES technologies, the integration of battery and capacitor systems has garnered substantial attention. In particular, internal parallel battery capacitors (BatCs) have emerged as a promising solution, capable of simultaneously delivering high energy and power densities, overcoming the limitations of individual components [3,4]. Lithium–ion BatCs (LIBatCs) have demonstrated notable success through various combinations, including (LiCoO2/AC)//Gr [5], (Li2Mn2O4/AC)//HC [5], (LiFePO4/AC)//Gr [6], and (LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2/AC)//Gr [7], among others [8]. These systems leverage synergistic effects arising from the complementary energy storage mechanisms of constituent materials. Several LIBatC configurations have already reached commercialization, finding practical applications such as fast–charging city buses, regenerative energy recovery, and grid frequency regulation [9,10]. However, the growing escalating cost of lithium resources since 2020 have underscored the need for sustainable and economically viable alternatives [11].

In response to these challenges, sodium–ion EES systems have advanced rapidly, leveraging sodium’s natural abundance, lower material cost, and compatibility with existing lithium–ion manufacturing infrastructure [12]. Furthermore, Na+ demonstrates superior transport kinetics compared with Li+, characterized by a smaller Stokes radius and lower desolvation energy, contributing to improved power capability and enhanced low–temperature performance [12,13]. Capitalizing on these advantages, sodium–ion battery capacitors (SIBatCs) have emerged as a logical and promising extension of LIBatC systems. Compared with conventional SIBs, SIBatCs demonstrate distinct performance advantages of superior fast–charging capability and extended cycle life under high–power conditions. These characteristics make them particularly suitable in scenarios requiring medium–to–high power outputs such as low–temperature startup, frequency regulation in smart grids, and regenerative braking energy recovery in vehicles. A critical challenge during SIBatCs’ development lies in the rational selection and integration of electrode materials, particularly in the design and fabrication of hybrid electrodes that combine battery–type and capacitor–type components. The architecture and composition—especially the mass ratio between faradaic and capacitive materials—play a decisive role in determining electrochemical behavior. Achieving an optimal balance between energy density, power density, and cycle life requires precise control over interfacial properties, charge storage kinetics, and structural stability [14].

The polyanion–type cathodes possess the benefits of high–voltage structural stability, minimal volume change, high reversibility, and superior thermal safety compared with other cathodes [15,16]. Among available sodium–ion materials, Na3V2(PO4)3 (NVP) is particularly notable due to its robust NASICON framework, high operating voltage, and high ionic conductivity. Nevertheless, its low intrinsic electronic conductivity often leads to sluggish reaction kinetics and rapid capacity fading under high–rate operation, limiting practical deployment [17]. In addition to conventional approaches such as nanostructuring, carbon coating, and conductive agent optimization, recent research has increasingly focused on hybridizing NVP with capacitive materials like activated carbon (AC) to construct hybrid electrodes, a strategy that should be carefully considered when developing novel SIBatCs with “double–high” (high energy and high power) attributes [18,19,20]. For example, Mainul Akhtar et al. [21] reported the synthesis and electrochemical properties of NVP@C/AC bi–material electrodes in the LIBatC system, and revealed that the synergistic effect is closely associated with a reduction in charge–transfer resistance (Rct) and an increase in Li+ diffusion coefficient with increasing AC content. The optimized NVP@C/AC40 electrode delivered a capacity of 40 mAh g−1 at 1000 mA g−1, retaining 67% after 500 cycles. In a sodium–ion system, Xu et al. [22] fabricated an NVP/AC bi–material cathode and proposed the “Nano Reservoir” concept. The resulting (AC/NVP)//Bi full–cell achieved an energy density of 218.6 Wh kg−1 and a power density of 22.7 kW kg−1 under presodiation conditions. Zhang et al. [19] further demonstrated that AC incorporation effectively alleviated polarization at high rates. With an NVP/AC mass ratio of 3:1, the hybrid cathode retained 82% capacity after 2000 cycles at 5 A g−1, far exceeding 56% retention of the pure NVP. Similarly, Li et al. [23] reported that a hybrid electrode containing 20 wt.% AC maintained 70% capacity at 50 C, compared with only 45% for NVP alone, further validating the effectiveness of hybrid design.

Despite these advances, critical challenges persist in developing SIBatCs. Previous studies have largely relied on presodiated anodes involving complex, environmentally burdensome processes, high costs, and limited scalability—posing major barriers to commercialization. Furthermore, existing efforts in component optimization often lack systematic variation in material ratios, and detailed evaluations under realistic conditions (e.g., in pouch full cells) remain scarce. Therefore, a more thorough investigation into the effect of NVP/AC mass ratios and the role of AC in practical pouch configurations is urgently needed.

In this work, we designed a series of hybrid cathodes with finely tuned NVP/AC mass ratios and fabricated corresponding quasi–commercial pouch SIBatCs. The NVP acts not only as a capacity contributor but also as an in situ sodium source, circumventing complex anode presodiation—a key distinction from conventional SICs. The role of AC in contributing to capacitive capacity, enhancing electrical conductivity, and acting as an electrolyte reservoir was demonstrated. Comprehensive evaluations revealed that the optimal NVP/AC mass ratio in hybrid cathodes ranged from 10:1 to 2:1. Specifically, SIBatCs incorporating hybrid cathodes with NVP/AC mass ratios of 10:1 (R10/1) and 4:1 (R4/1) achieved exceptional overall performance, balancing low internal resistance, high energy output, excellent rate performance, and long cycle life.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of Hybrid Cathodes and SIBatCs

All materials were used as received without further pretreatment. These include Na3V2(PO4)3 (NVP, Hubei Ennaiji Technology Co., Ltd., Guangshui, China), activated carbon (AC, Kuraray Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), hard carbon (HC, Kuraray Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), cellulose/PET composite separator (Nippon Kodoshi Corporation, Kochi, Japan), sodium–ion electrolyte (1 M NaPF6 in EC/DMC/DEC with 2 wt.% additives, Huzhou Kunlun Enchem Battery Materials Co., Ltd., Huzhou, China), and conductive agents (Super P (SP) and multi–walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) with a mass ratio of 3:1, Jiangsu Cnano Technology Co., Ltd., Zhenjiang, China). Hybrid cathodes were prepared by first dry–mixing NVP and AC powders through a double–cone powder mixer at mass ratios of 10:1, 4:1, 2:1, 1:1, and 1:2, with resulting composites denoted as R10/1, R4/1, R2/1, R1/1, and R1/2, respectively. For comparison, pure NVP (RNVP, representing SIB) and pure AC (RAC, representing SIC) cathodes were fabricated. The active materials, conductive agents, and binder were mixed at a mass ratio of 90:5:5. A slurry was formed by adding NMP followed by rapid mixing. After homogenization, the slurry was coated onto aluminum foil using a blade, followed by vacuum drying at 120 °C for 8 h. The anode was prepared similarly with 95 wt.% HC and 5 wt.% PVDF on copper foil. The mass loadings of cathode and anode were controlled at 12.0 mg cm−2 and 5.6 mg cm−2, respectively. Note that the anode–to–cathode (N/P) capacity ratio was left unbalanced in this work. Both CR2025 coin cells and pouch full cells were assembled. Coin cells employed sodium metal as the counter/reference electrode. Pouch cells were constructed in a stacked sandwich configuration (cathode/separator/anode) with aluminum–plastic film packaging.

2.2. Characterizations

The crystal structure was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a BRUKER D8 Discover X-ray diffractometer (Bruker Corporation, Walzbach, Germany) with a Cu–Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å). The measurements were performed over a 2θ range of 5–80° at a scanning rate of 5° min−1. The surface morphologies were observed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a ZEISS Sigma 300 microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). The electrical resistivity of electrode slices was measured using an ACCFILM tester (TT–ACCF–G2R) (Chuanyuan Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China) under the constant–pressure mode with an applied pressure ranging from 5 to 60 MPa. The electrolyte–uptake capability was measured via the weighing method, while the gas production behavior was characterized using the water displacement method. Electrochemical performance tests were conducted using ARBIN (Arbin Instruments Inc., Houston, TX, USA) and NEWARE (Neware Technology Ltd., Shenzhen, China) equipment. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed using a Gamry R3000 (Gamry Instruments Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA) electrochemical workstation. Performance evaluations under extreme conditions were performed in constant–temperature environmental chambers.

2.3. Electrochemical Testing

For half cells, CV measurements were performed at scan rates of 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mV s−1 within the voltage window of 1.8–3.8 V (vs. Na/Na+). EIS was conducted at 3.2 V with an applied amplitude of 5 mV over a frequency range of 0.05 Hz to 100 kHz. Galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) tests were carried out at a constant current of 0.2 mA. To assess rate performance, the cells were charged at 0.2 mA and discharged at currents ranging from 0.2 to 6.0 mA. Regarding full cells, CV was performed at scan rates of 0.1–0.5 mV s−1. Direct current internal resistance (DCR) was determined from the instantaneous IR drop during the charge/discharge transition at 100 mA. To evaluate rate performance, asymmetric charge–discharge protocols—including slow charge–fast discharge and fast charge–slow discharge—were implemented at different currents ranging from 100 mA to 20 A. Low–temperature discharge capability was assessed by placing fully charged cells in a temperature–controlled chamber set between −30 and 25 °C. After an 8 h thermal equilibration period, cells were discharged to 1.8 V at 1 A. For high–temperature stability tests, fully charged cells were stored at 60 °C for 28 days, while open–circuit voltage (OCV) was periodically recorded. After storage, changes in DCR and discharge capacity were measured. Cycle life was evaluated using a constant current–constant voltage–constant current (CC–CV–DC) protocol, with a current of 2 A and a constant–voltage hold time of 60 s. EIS was performed at 3.0 V with an amplitude of 5 mV over a frequency range of 0.05 Hz to 100 kHz. Unless otherwise stated, all C–rates were calculated based on the cell’s capacity measured at 100 mA. Current density, specific capacity, energy density, and power density were normalized to the mass of active materials.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Material Information and Electrode Slice Characterization

The physicochemical and structural properties of electrode materials are summarized in Table 1. The AC, synthesized via vapor activation, displays a median particle size (D50) of 5.9 μm and possesses a high specific surface area (SSA) of ~1600 m2 g−1 with a well–defined mesoporous structure. In contrast, the NVP exhibits a D50 of 5.1 μm and a much lower SSA of ~15 m2 g−1. The HC shows a D50 of 5.4 μm and an SSA of ~7 m2 g−1. The surface of NVP is coated with ~2.0 wt.% amorphous carbon, improving electrical conductivity and facilitating homogenized interfacial contact with AC and conductive agents. Compared with AC and HC, NVP shows significantly higher electrical resistivity and tap density.

Table 1.

Key parameters of the electrode materials.

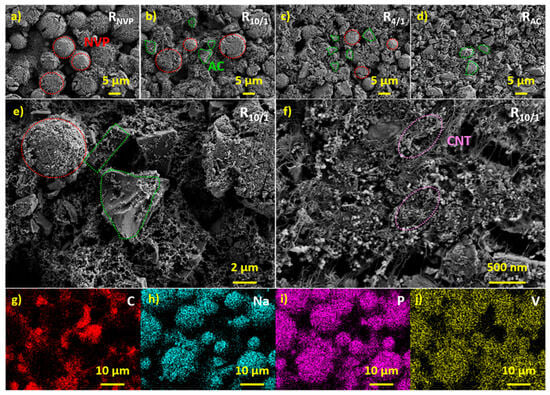

The surface morphologies of cathode slices were characterized via SEM. Figure 1a–d display the images of RNVP, R10/1, R4/1, and RAC at a magnification of 2k×, where NVP appears as regular spherical particles, while AC presents as irregular lumpy particles. To optimize electrochemical performance, a dual conductive agent system was employed. Higher–magnification SEM images of R10/1 (Figure 1e,f) demonstrate that long–range conductive MWCNTs form percolating networks bridging AC and NVP particles, while short–range conductive SP fills interparticle voids. Their incorporation significantly improves electrical conductivity of both the horizontal and vertical surfaces of electrode slices. Elemental mapping (Figure 1g–j) confirms the homogeneous distribution of C, Na, P, and V throughout the R10/1 slice. Round NVP particles and irregularly shaped AC particles can be distinguished using their color–coded positions. The uniform element distribution across the slice not only confirms the homogeneous mixing of active materials, conductive agents, and binder but also validates the effectiveness of our slurry preparation.

Figure 1.

(a–d) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the RNVP, R10/1, R4/1, and RAC cathode slices at 2k× magnification; (e,f) higher–magnification SEM images of the R10/1 cathode slice at 5k× and 20k×, respectively; (g–j) corresponding elemental mapping of the R10/1 slice, showing the spatial distribution of C, Na, P, and V.

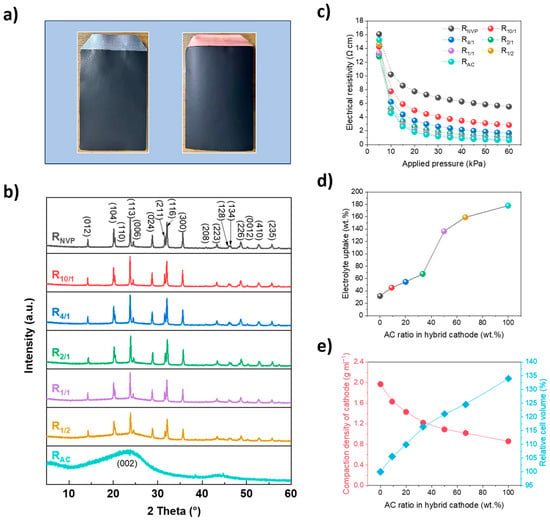

The digital images of cathode and anode slices are presented in Figure 2a, where both samples exhibit a uniform, smooth, and dense morphology after the rolling process. XRD analysis (Figure 2b) reveals the crystallographic features of cathode slices with varying NVP/AC mass ratios. The RNVP slice exhibits characteristic diffraction peaks corresponding to a rhombohedral structure with an R3c space group, consistent with that of pure NVP (JCPDS No. 53–0018) [24]. For RAC, the broad diffraction peaks centered at 23.4° (002) and 43.5° (100) exhibit typical amorphous carbon features [25]. Hybrid cathodes demonstrate superimposed diffraction patterns containing both crystalline NVP and AC components, with AC–derived features being most pronounced in R1/1 and R1/2 configurations where AC ratio is ≥50 wt.%. Progressive attenuation of amorphous carbon signatures occurs with increasing NVP content, becoming negligible at AC ratios of ≤20 wt.% due to the dominant signal contribution from the highly crystalline NVP.

Figure 2.

(a) Digital photographs of the R10/1 hybrid cathode and hard carbon (HC) anode slices; (b) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of various cathode slices; (c) electrical resistivity as a function of applied pressure; (d) electrolyte–uptake behavior of different cathode slices; (e) compaction density and relative cell volume versus AC ratio in hybrid cathode.

The incorporation of AC significantly modifies both electrical and electrochemical properties. Figure 2c demonstrates a pronounced pressure–dependent resistivity behavior, where increasing applied pressure from 5 to 60 MPa reduces electrical resistivity across all cathode slices. This highlights the critical role of particle–to–particle contact in establishing effective conductive networks during slice preparation. However, the competing effects between enhanced interparticle contact versus reduced electrode porosity should be considered carefully, which would influence the electrode stability [26]. The AC component contributes to both conductivity enhancement and electrolyte accessibility. At an applied pressure of 60 MPa, R10/1 and R4/1 exhibit significant resistivity reductions of 48.6% and 75.2%, respectively, compared with RNVP. The conductivity enhancement nearly saturates at an NVP/AC mass ratio of 2:1, suggesting the threshold of AC addition.

The marked difference in SSA between AC and NVP fundamentally governs the electrolyte–uptake behavior. As shown in Figure 2d, a strong correlation exists between AC ratio and electrolyte–uptake capability, with values ranging from 31.7 wt.% for RNVP to 177.8 wt.% for the RAC slice. This enhancement results from the tenability of slice porosity and AC’s hierarchical pore structure: micropores providing high surface areas for electrolyte wetting; mesopores facilitating rapid ion transport; macropores serving as electrolyte reservoirs [27]. Improving electrolyte–uptake capability is generally conducive to mitigating polarization and preventing electrolyte depletion during long–term cycling.

Moreover, the intrinsic tap density difference between active materials affects the electrode slice compaction behavior. As shown in Figure 2e, RNVP achieves the highest compaction density of 1.97 g cm−3, approximately 2.3 times that of the RAC slice (0.86 g cm−3). With increasing AC content, the compaction density progressively decreases from 1.63 g cm−3 for R10/1 to 1.02 g cm−3 for R1/2. Notably, under equivalent areal loading conditions, RAC (SIC) exhibits a 34.0% larger cell volume than RNVP (SIB). In contrast, hybrid cathodes demonstrate tunable volume efficiency, with R10/1 and R4/1 only showing 5.6% and 9.9% relative volume increases relative to RNVP, respectively. This hybrid design with balance between volume density and slice porosity offers a critical advantage for space–constrained applications compared with traditional SICs.

3.2. Electrochemical Performance Evaluation in Half Cells

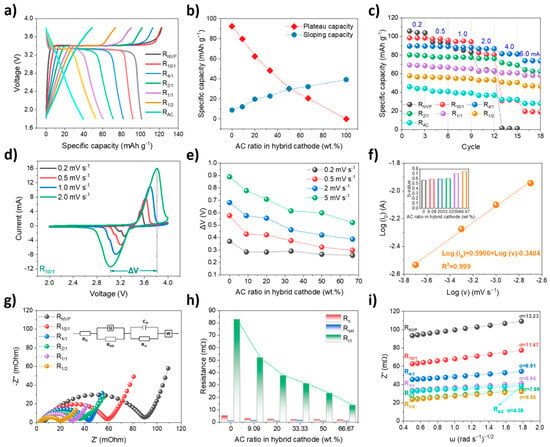

Prior to full–cell assembly, the electrochemical properties of various cathodes were evaluated in half cells within 1.8–3.8 V. As shown in Figure 3a, RAC exhibits near–liner GCD profiles, indicative of dominant capacitive behavior. In contrast, NVP–containing cathodes display a combination of flat redox plateaus and sloping regions, suggesting a hybrid EES mechanism involving both Faradaic Na+ intercalation/deintercalation from NVP and non–Faradaic ion adsorption/desorption on AC. A clear correlation is observed between cathode composition and specific capacity (Figure 3b). RNVP and RAC deliver specific capacities of 101.4 and 39.3 mAh g−1, with capacitive contributions (quantified via sloping regions) accounting for 5.8% and 100% of the total capacity, respectively. As the NVP/AC mass ratio decreases from 10:1 to 1:2, the cathodic capacity declines from 92.1 to 52.8 mAh g−1, with the capacitive contribution increasing from 8.4% to 35.4%, highlighting the growing role of capacitive controlled processes. Note that the corresponding N/P capacity ratios are 1.46, 1.61, 1.80, 2.08, 2.44, 2.80, and 3.76, respectively, according to the specific capacities of the various cathodes and hard carbon anode (300 mAh g−1). A near–linear relationship between the sloping capacity and AC ratio confirms the tunability of the storage mechanism through compositional design. The influence of AC on electrochemical kinetics was investigated through rate tests, as shown in Figure 3c. Increasing the AC content significantly improves capacity retention at high currents, particularly in cells with AC ratios of ≥20 wt.%. This trend underscores the superior rate capability of capacitive–dominated materials. Under a symmetric charge–discharge current regime, RNVP exhibits a sharp capacity drop to negligible values even at a moderate current of 0.4 mA (6.45 A g−1), with retention far below other cathodes. Although R10/1 shows improved performance over RNVP—delivering 19.2 mAh g−1 with 19.5% retention at an elevated current of 0.6 mA (9.68 A g−1)—it is substantially outperformed by R4/1, which achieves the highest capacity of 73.9 mAh g−1 with 82.2% retention. This result emphasizes the limited effectiveness of insufficient AC addition in improving rate performance. The hybrid cathodes demonstrate a clear synergistic effect, significantly exceeding pure AC, pure NVP, and their capacity sum at high currents.

Figure 3.

(a) Galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) profiles at 0.2 mA; (b) deconvolution of specific capacities into plateau and sloping regions, corresponding to the battery–type and capacitive contribution, respectively; (c) rate capability showing specific capacities at varying current densities; (d) cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the R10/1 hybrid cathode at scan rates from 0.2 to 2.0 mV s−1; (e) potential difference (ΔV) between anodic and cathodic peaks; (f) linear dependence of oxidation peak current on the square root of scan rate (ν1/2) for the R10/1 cathode, with corresponding b–values shown in inset; (g) Nyquist plots with equivalent circuit model (inset); (h) fitted resistance components from EIS analysis; (i) relationship between Z’ and ω−1/2 (where ω is angular frequency), demonstrating Warburg diffusion behavior.

A detailed electrochemical investigation of various cathodes was conducted via CV measurements. RAC exhibits a nearly rectangular CV profile—consistent with typical capacitive charge storage behavior. While NVP–containing cathodes display pronounced redox peaks, corresponding to reversible Na+ deintercalation/intercalation in a NVP lattice [22]. Representative CV curves at scan rates ranging from 0.2 to 2 mV s−1 for the R10/1 cathode are presented in Figure 3d. With increasing scan rate, the oxidation peak shifts toward higher potentials, while the reduction peak shifts towards lower potentials, indicating enhanced cell polarization. The potential difference (ΔV) between the oxidation and reduction peaks, as derived from CV curves in Figure 3d, is used to evaluate kinetic limitations within cathodes [28]. As summarized in Figure 3e, RNVP exhibits the largest ΔV across all scan rates, indicating pronounced polarization and slow reaction kinetics. In contrast, hybrid cathodes demonstrate progressively smaller ΔV values as the AC ratio increases, confirming that AC incorporation significantly reduces electrode polarization. This improvement is particularly evident when the NVP/AC mass ratio falls below 4:1. The current response (ip) as a function of scan rate (ν) is analyzed using the power–law relationship [29], where the b–value derived from the fitting analysis serves as an indicator of the charge storage mechanism. As shown in Figure 3f, the b–value (inset) for the redox peak increases from 0.569 to 0.743 with increasing AC ratio from 0 to 66.67 wt.%, confirming enhanced contributions from the capacitive controlled processes. The b–values are comparable across samples with NVP/AC mass ratios of 10:1–2:1. However, a pronounced b–value increase occurs when the NVP/AC mass ratio decreases from 2:1 (b = 0.597) to 1:1 (b = 0.706), marking the point where capacitive contributions become more prominent.

Additionally, EIS was employed to investigate the resistance behavior, with Nyquist plots presented in Figure 3g, along with an inner equivalent circuit model for quantitative fitting. The circuit includes series resistance (Rs), solid–electrolyte interphase resistance (Rsei), charge–transfer resistance (Rct), and Warburg impedance (Zw). Clearly, the semicircle (combined Rsei + Rct) in the Nyquist plot is noticeably compressed as the AC content increases, indicating exceptionally favorable charge–transfer kinetics. This trend is corroborated by subsequent detailed EIS fitting results, as summarized in Figure 3h. Compared with Rs and Rsei, Rct constitutes the dominant component of the total resistance. The observed Rct reduction with increasing AC ratio highlights the enhanced charge–transfer kinetics, attributable to improved ionic transport at electrode–electrolyte interface and more efficient electronic percolation throughout hybrid cathode. Specifically, RNVP exhibits the highest Rct of 83.0 mΩ, with this value decreasing substantially to 52.2 mΩ for R10/1, and, ultimately, dropping to 13.8 mΩ for R1/2. This progressive Rct reduction aligns with the decreased polarization observed in CV measurements, further underscoring the beneficial role of AC in facilitating faster kinetics. Beyond mitigating charge–transfer impedance, the AC incorporation exerts a significant impact on ion diffusion behavior. As illustrated in Figure 3i, the real part of impedance (Z′) exhibits a linear dependence on the inverse square root of angular frequency (ω−1/2), allowing for the determination of Warburg diffusion factor (σ) and subsequent calculation of sodium–ion diffusion coefficients (DNa+) for each cathode [30]. With increasing AC content, σ shows a clearly decreasing trend, with R4/1 representing a critical optimization point. Specifically, σ decreases from 12.23 for RNVP to 6.91 for R4/1, corresponding to a DNa+ increase from 1.31 × 10−13 to 4.10 × 10−13 cm2 s−1. Further increasing AC ratios beyond 20 wt.% has a negligible effect on DNa+, indicating the saturated AC–facilitated diffusion–enhancing effect. Overall, the simultaneous reduction in Rct and enhancement of DNa+ are attributed to the synergistic effects arising from the NVP/AC hybrid design, including improved electrical conductivity, greater electrolyte permeability, and facilitated ion transport. The NVP/AC mass ratio of 4:1 is identified as optimal in half–cell system, as it delivers satisfactory capacity alongside superior rate performance—benefiting from significantly decreased Rct and improved DNa+. These results underscore that the strategic integration of NVP and AC creates a complementary interplay between diffusion–controlled and capacitive mechanisms, enabling hybrid cathodes with low polarization and superior kinetic performance.

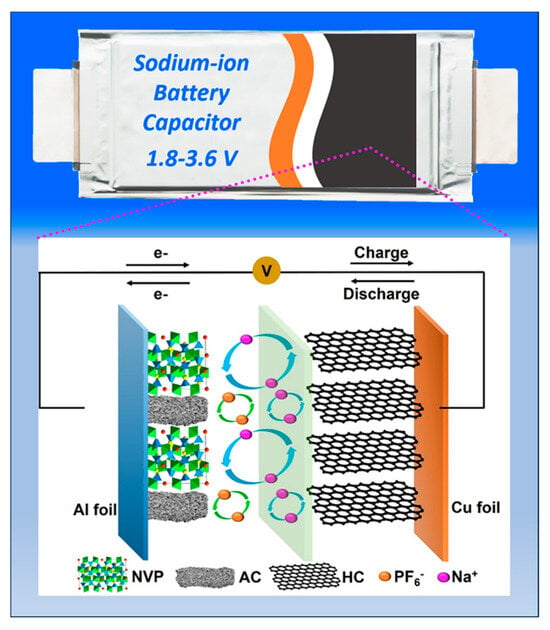

3.3. Electrochemical Performance Evaluation in Full Cells (SIBatCs)

Compared with half cells, full cells yield more convincing electrochemical data, as their performance more closely reflects the real–world operating conditions. As schematically illustrated in Figure 4, SIBatC is a hybrid EES device that integrates SIC and SIB components in an inter–parallel configuration at the electrode level. Owing to the complementary nature of NVP and AC, both Faradaic and non–Faradaic reactions occur concurrently during the entire energy storage operation [22]. Specifically, during charging and discharging, PF6− anions are adsorbed/desorbed on the AC surface, while Na+ cations are reversibly deintercalated/intercalated within the NVP framework. To enhance performance, an optimized cellulose/PET composite separator was incorporated, improving electrolyte retention and facilitating rapid ion transport [31].

Figure 4.

Structural diagram of the pouch SIBatC with a schematic dual–functional energy storage mechanism.

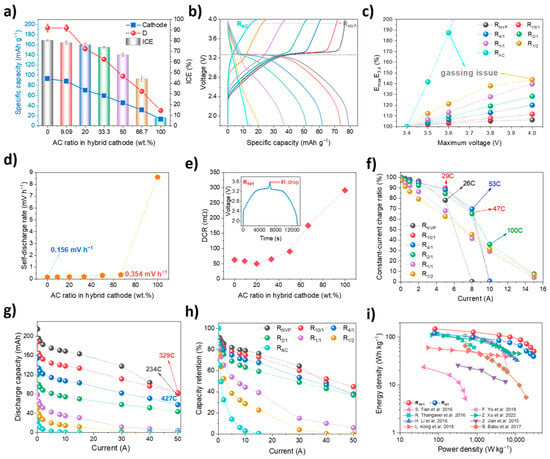

Owing to the utilization of hard carbon anodes, the electrochemical behavior of each cathode may differ between full cells and half cells, and the formation process plays a critical role in activating SIBatCs. As shown in Figure 5a, increasing AC content results in a decline in both the discharge capacity and initial coulombic efficiency (ICE). RNVP demonstrates the highest performance, with a cathodic specific capacity of 93.1 mAh g−1 and an ICE of 80.3%. As the NVP/AC mass ratio decreases from 10:1 to 1:2, the cathodic capacity drops from 88.0 to 31.3 mAh g−1, while the anodic capacity decreases from 193.0 to 68.1 mAh g−1, with the corresponding ICE declining from 77.9% to 44.1%. In contrast, RAC exhibits particularly poor performance, with a discharge capacity of only 13.2 mAh g−1 and an ICE of 7.5%, along with noticeable gas evolution. The reduced anodic capacity from 193.3 mAh g−1 for RNVP to 30.3 mAh g−1 for RAC demonstrates limited anode utilization. This imbalance forces the cathode to operate at higher potentials as the AC ratio increases within the fixed voltage window, promoting side reactions and accelerating performance degradation [32].

Figure 5.

(a) Initial coulombic efficiency (ICE) and reversible specific capacities of the cathode and anode during the first charge/discharge cycle; (b) galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) profiles at 100 mA current; (c) energy output at 100 mA current across varying cutoff voltages (3.4–4.0 V); (d) correlation between self–discharge rate and AC ratio; (e) direct current internal resistance (DCR) measured at 100 mA (inset: GCD curve of R10/1); (f) constant–current charge capacity ratio in fast–charge/slow–discharge mode; (g,h) discharge capacity and its retention in slow–charge/fast–discharge mode; (i) Ragone plots comparing R10/1, R4/1, and previously reported works [12,23,33,34,35,36,37,38].

The cathodic specific capacity (C) and cell energy density (E) are highly consistent with Equations (1) and (2) through fitting analysis, where r denotes the AC ratio (wt.%) in the hybrid cathode. The units of C and E are mAh g−1 and Wh kg−1, respectively. This provides valuable insight for estimating the capacity and energy of SIBatCs incorporating dual–functional hybrid cathodes.

The GCD curves within 1.8–4.0 V at a current of 100 mA are presented in Figure 5b. RAC exhibits a fully linear profile, whereas NVP–containing curves consist of sloping segments and a flat voltage plateau. The capacity contribution derived from sloping regions correlates positively with the AC content. For R2/1, the voltage plateau is barely discernible, suggesting dominant capacitive behavior in this hybrid configuration. Raising the operating voltage significantly improves energy output, particularly in AC–rich cathodes. As shown in Figure 5c, elevating the upper cutoff voltage from 3.4 to 4.0 V results in an 6.3% energy enhancement for RNVP, compared with 11.6–39.7% for R10/1–R1/1, in order. This underscores the voltage–sensitive energy storage behavior derived from capacitive materials, exceeding the limited voltage–dependent capacity increase in battery–type NVP. However, R1/2 and RAC exhibited severe gassing behavior above 3.6 V, mainly attributed to cathode overpotential under presodiation–free conditions [39]. To ensure comprehensive performance, an optimal voltage window of 1.8–3.6 V is selected for SIBatCs.

Rapid self–discharge is a well–known limitation for supercapacitors, while the incorporation of battery–type material effectively suppresses this behavior. As illustrated in Figure 5d, the self–discharge rate increases from 0.156 to 0.354 mV h−1 as the AC ratio rises from 0 to 66.7 wt.%, with RAC exhibiting the most rapid voltage decay. This is closely linked to the energy storage mechanism—Faradaic materials provide greater thermodynamic stability [40]. The judicious inclusion of AC also beneficially influences resistance. As observed in Figure 5e, R10/1 and R4/1 achieve the lowest DCR values of 58.9 and 50.1 mΩ, respectively, representing reductions of 6.4% and 20.3% relative to RNVP (62.9 mΩ). Notably, the DCR increases sharply from 64.7 mΩ for R2/1 to 90.7 mΩ for R1/1—marking a critical threshold (33.3 wt.% AC). Beyond this ratio, the conductivity gains from AC are offset by the increased charge–transfer resistance, as illustrated in Figure 6.

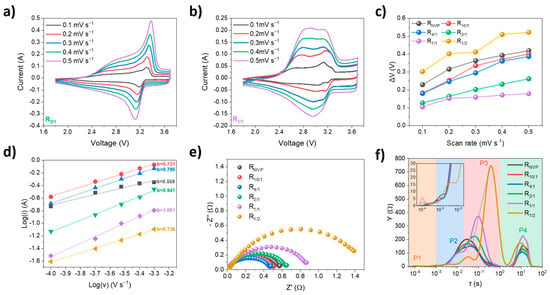

Figure 6.

(a,b) CV curves of R2/1 and R1/1 SIBatCs at scan rates ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 mV s−1; (c) potential difference (ΔV) between oxidation and redox peaks as a function of scan rate; (d) linear fitting of Log(ip) versus Log(v); (e) Nyquist plots at a frequency ranging from 100 kHz to 0.05 Hz; (f) distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis derived from EIS data.

Rate capability—encompassing both rapid charge and discharge—was evaluated under different regimes. The constant–current charge ratio (CCCR) during CC–CV process serves as a key indicator of fast–charging capability. Under fast charge–slow discharge conditions (Figure 5f), CCCR declines with increasing current, yet cells with higher AC content consistently outperform those dominated by NVP, confirming superior charge kinetics of hybrid cathodes. However, when the AC ratio is ≥50 wt.%, the capacity deteriorates and the overall competitiveness diminishes, indicating a trade–off between fast–charge acceptance and energy delivery. In the slow charge–fast discharge mode (Figure 5g,h), RNVP delivers the highest capacities at low–to–medium currents yet suffers significant degradation under high–current conditions. At a current of 50 A (329C), R10/1 delivers the highest discharge capacity and retention, with values of 82.5 mAh and 44.9%, respectively. Both metrics outperform those of the RNVP counterpart, demonstrating the excellent compatibility of R10/1 with high–power operations. Notably, even under significantly higher current rates, R4/1 and R2/1 exhibit capacity retentions of 37.9% and 36.9%, respectively—values comparable to that of RNVP (37.8%). Ragone plots derived from slow charge–fast discharge mode are presented in Figure 5i. R10/1 and R4/1 achieve energy densities of 148.9 and 120.6 Wh kg−1 at power densities of 81.0 and 79.3 W kg−1, respectively. Even at ultrahigh power densities of 30,526.6 and 29,810.6 W kg−1, they still retain energy densities of 50.4 and 39.6 Wh kg−1, outperforming reported sodium–based EES devices [12,23,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Note that the mass of active materials accounts for 23.4% and 23.0% of the total mass of R10/1 and R4/1 configurations, respectively. This superior energy–power trade–off is particularly evident within the NVP/AC mass ratio range of 10:1 to 2:1, underscoring the efficacy of hybrid cathode design. The rate enhancement predominantly stems from the multifunctional role of the hybrid cathode design: it improves electrical conductivity, reduces internal resistance and polarization, increases electrolyte accessibility and retention, and facilitates rapid ion transport. Together, these contributions enable simultaneous high energy and power densities, positioning SIBatCs as competitive EES candidates.

To elucidate the influence of NVP/AC mass ratio on SIBatC kinetics, CV and EIS were carried out. Figure 6a,b shows representative CV curves of R2/1 and R1/1 at varying scan rates. The presence of a presodiation–free HC anode significantly affects the CV shapes, which differs from those observed in half cells. As the AC content increases, the CV curves evolve continuously, with the coupling behaviors of NVP, AC, and HC becoming particularly evident in the SIBatC incorporating R1/1 (Figure 6b). Additionally, ΔV values for various SIBatCs are summarized in Figure 6c. As the AC ratio increases, ΔV decreases monotonically until the system reaches an optimal NVP/AC mass ratio of 1:1, demonstrating the continued polarization. This kinetic enhancement serves as the foundation for the improved rate capability in hybrid cathode configurations. However, further increasing the AC content leads to a rise in ΔV—even larger than that of pure NVP—a behavior not observed in half cells, which is attributed to N/P capacity mismatch in full–cell configurations. Such an imbalance forces the cathode to operate at higher potentials, which promote the over–deintercalation of Na+ from the NVP framework, ultimately resulting in structural degradation and accelerated failure. The anodic log(ip) vs. log(ν) curves for SIBatCs incorporating NVP–containing cathodes are illustrated in Figure 6d. Linear fitting results indicate that the b–value increases with rising AC ratios, ranging from 0.558 for RNVP to 1.081 for R1/1. A pronounced b–value increase is observed as the NVP/AC mass ratio shifts from 4:1 to 2:1, suggesting a notable enhancement in capacitive contribution. However, further increasing the AC ratio results in a markedly decreased b–value, indicating reduced kinetics associated with increased polarization as shown in Figure 6c. These findings highlight the critical need to optimize NVP/AC mass ratios—not only to minimize polarization and enhance kinetics but also to maintain electrode balancing in full–cell configurations.

The Nyquist plots of SIBatCs are shown in Figure 6e, with the semicircle in the high–to–medium frequency region corresponding to the combined interfacial film resistance (Rf) and charge–transfer resistance (Rct). The AC addition significantly reduces combined resistance (Rf + Rct), with the most pronounced decrease observed for R10/1 and R4/1. However, as the NVP/AC mass ratio reaches 2:1, the (Rf + Rct) exceeds that of RNVP, and further increasing the AC ratio results in a dramatical rise in (Rf + Rct). Both full cells and half cells demonstrate that the hybrid cathode design significantly reduces polarization and resistance. Notably, distinct behaviors in CV and EIS results are observed between the two configurations, which mainly stem from the coupling effect of the presodiation–free HC anode.

Distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis is a powerful deconvolution tool that resolves overlapping impedance processes into distinct, physically meaningful relaxation times, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional equivalent circuit models for complex systems like ours. To quantify polarization contributions from individual electrochemical processes, DRT analysis was employed, with results illustrated in Figure 6f. The DRT profiles reveal distinct time–constant regions corresponding to specific impedance sources: the peak in the range of 10−4–10−2 s is associated with the solid–electrolyte interphase (Rf); the peak within 10−2–1 s represents charge–transfer resistance (Rct); the peak within 1–102 s is related to solid–state ion transport in active materials (Zw) [41,42]. For RNVP and R10/1, two discernible peaks are observed near 0.03 s and 12.5 s, with charge–transfer resistance dominating the overall polarization. However, when the AC ratio increases to ≥20 wt.%, the peak near 0.03 s splits into two peaks centered near 0.01 s and 0.045 s, corresponding to Rf and Rct, respectively. Apparently, the AC incorporation reduces both Rct and Zw particularly at an NVP/AC mass ratio range of 10:1–4:1, suggesting enhanced interfacial ion transport and ion diffusion, which is attributed to AC’s superior electrical conductivity and improved electrolyte accessibility [43]. When the AC ratio further increases to ≥33.3 wt.%, τ shifts to a larger value—signaling an increased Rct, which hinders high–power operation. For R1/1 and R1/2, the larger τ values, along with markedly elevated Rct and Zw, confirm severely hindered charge––transfer and ion diffusion, explaining their inferior electrochemical performance. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing component ratios in hybrid cathodes to balance interfacial properties, charge–transfer, and diffusion—ultimately achieving lower internal resistance and reduced polarization, facilitating an enhanced rate capability [44].

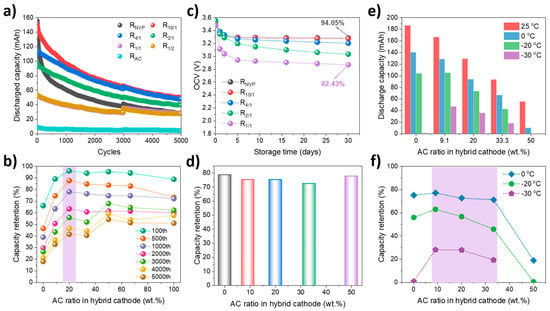

Cycling stability under high–rate conditions represents a critical advantage of SIBatCs over SIBs. As shown in Figure 7a,b, at the current of 2 A, RNVP and R10/1 deliver comparable initial discharge capacities of 155.8 and 151.9 mAh, respectively. However, RNVP exhibits a significantly accelerated capacity that fades during extended cycling compared with hybrid cathodes. Although R4/1 displays a lower initial capacity, it surpasses R10/1 after 1000 cycles due to its superior stability. After 5000 cycles, R10/1, R4/1, and R2/1 maintain discharge capacities and retentions of (49.8 mAh, 32.8%), (48.2 mAh, 41.6%), and (39.5 mAh, 40.5%), respectively, significantly outperforming both RNVP (28.1 mAh, 18.0%) and RAC (4.6 mAh, 51.1%). A positive correlation between capacity retention and AC addition can be observed with AC ratios of ≤33.3 wt.%, underscoring the critical role of capacitive materials in stabilizing long–term, high–rate performance. Among samples, R10/1 and R4/1 exhibit the highest energy efficiency of 88.2% and 87.4%, respectively, exceeding 85.8% for RNVP and ~60% for RAC. This enhanced cyclability predominantly stems from the synergistic effect of the hybrid cathode design and further validates that hybrid cathodes with NVP/AC mass ratios of 10:1 and 4:1 offer an optimal balance.

Figure 7.

(a) Long–term cycling performance over 5000 cycles; (b) capacity retention at selected cycle intervals; (c) evolution of open–circuit voltage (OCV) during high–temperature storage at 60 °C; (d) post–storage capacity recovery after high–temperature storage; (e) discharge performance at varying temperatures (−30–25 °C); (f) temperature–dependent capacity retention.

Given the performance degradation associated with excessive AC addition, the high–temperature stability of SIBatCs with AC ratios of ≤50 wt.% was systematically evaluated. As shown in Figure 7c, after 28–day storage at 60 °C, RNVP, R10/1, and R4/1 demonstrated excellent OCV retention, maintaining 94.0%, 92.7%, and 90.1% of their initial values, respectively. In contrast, R1/1 exhibits rapid voltage decay, dropping from 3.483 V to 2.944 V within the first five days. Post–storage capacity retention is summarized in Figure 7d. As the AC ratio increases, the capacity retention decreases from 78.8% for RNVP to 72.5% for R2/1. Interestingly, R1/1 shows an improved capacity retention of 77.8%, which is attributed to its lower end–of–storage OCV resulting from higher self–discharge rates. It is well established that the capacity retention of the EES device is inversely related to both storage temperature and the operational OCV, as elevated voltages and temperatures accelerate parasitic reactions such as electrolyte decomposition and electrode passivation [45]. These results reaffirm that hybrid cathodes with AC ratios of ≤20 wt.% effectively balance energy storage and high–temperature resilience.

Low–temperature discharge capability was evaluated under a discharge current of 1 A. As shown in Figure 7e,f, R10/1 exhibits capacity retentions of 77.2%, 63.1%, and 28.3% at 0 °C, −20 °C, and −30 °C, respectively. In comparison, RNVP demonstrates retentions of 75.3% and 56.0% at 0 °C and −20 °C but fails to operate at −30 °C due to excessive internal resistance (IR) drop and sluggish ion diffusion. R4/1 and R2/1 also maintain notable capacity retentions of 28.0% and 19.5% at –30 °C, underscoring the beneficial role of moderate AC addition in enhancing kinetics under extreme conditions. To ensure balanced performance at low–temperature environments, the AC ratio should be limited to a maximum of 33.3 wt.%, which effectively mitigates the trade–off between energy retention and polarization resistance, enabling stable operation over a wide temperature range.

Regarding the role of AC in hybrid cathodes and SIBatCs, its multifunctional contributions can be summarized as follows: firstly, as a capacitive material, AC provides adsorption/desorption capacity with superior power performance; secondly, the AC incorporation enhances the electrical conductivity of the electrode slice, thereby facilitating efficient electron transfer; thirdly, owing to the ultrahigh SSA—analogous to a sponge—AC exhibits enhanced electrolyte–uptake capability, ensuring the battery–type NVP is “immersed” in an electrolyte–rich environment and enabling faster ion transport during high–power output; and finally, the presence of AC can regulate the porosity of the electrode slice, promoting electrolyte wetting and ion diffusion. These synergistic effects collectively migrate polarization and reduce resistance, thus enhancing SIBatC power performance and cycling stability. However, excessive AC content may lead to accelerated capacity fade, as well as high self–discharge rate and gas generation in full cells without presodiation. NVP/AC mass ratios within the range of 10:1–2:1 are identified as optimal to balance power density, energy density, and cycling durability. Furthermore, proper N/P capacity matching is also essential to minimize polarization and achieve stable long–term performance in SIBatC configurations, which is in progress.

4. Conclusions

A series of hybrid cathodes with varying NVP/AC mass ratios were fabricated and evaluated in both half–cell and full–cell (SIBatC) configurations. Electrochemical performance assessments revealed a distinct synergistic effect between battery–type and capacitor–type materials. The AC component played multiple critical roles in hybrid cathodes: it provided capacitive capacity via rapid anion adsorption/desorption, enhanced electrical conductivity by forming efficient percolation networks, and improved electrolyte uptake and retention owing to high SSA and porous structure. These combined effects reduced polarization and resistance, thereby enhancing rate performance.

Owing to the coupling effect of the presodiation–free anode and the mismatched configuration between anode and cathode capacities, hybrid cathodes exhibited performance differences between half cells and full cells. Balancing the benefits of AC and drawbacks of excessive AC is critical in full–cell systems. As determined in this work, an NVP/AC mass ratio of 4:1 was optimal for electrochemical kinetics in half cells. In contrast, the optimal ratio window shifted to 10:1 to 2:1 in full cells, with R10/1 and R4/1 configurations exhibiting the most balanced overall performance. They achieved high energy densities of 148.9 and 120.6 Wh kg−1 at power densities of 81.0 and 79.3 W kg−1, respectively, and retained 50.4 and 39.6 Wh kg−1 even at ultrahigh power densities of 30.5 and 29.8 kW kg−1. Furthermore, they maintained capacity retentions of 32.8% and 41.6% after 5000 cycles—significantly outperforming the pure NVP–based cell (18.0%). This work provides an effective material design strategy and evaluation framework for developing high–performance sodium–ion EES systems.

To advance SIBatCs toward commercialization, future efforts should focus on clarifying the capacity response and charge transport mechanisms of hybrid electrodes under dynamic power conditions; establishing correlations between the structural properties of AC and NVP and their electrochemical performance; optimizing N/P capacity matching and electrode slice thickness to minimize polarization; and developing functional electrolytes that enhance interfacial stability and enable wide–temperature operation.

Author Contributions

H.X.: conceptualization, cell testing, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; Y.Z.: cell testing and writing—original draft; C.Y.: materials testing; J.Z.: cell testing; Y.-L.B.: supervision and review; Z.A.: resources acquisition and review; J.X.: supervision and review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Shanghai Aowei Technology Development Co., Ltd.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hengheng Xia, Yuman Zhang, Chongyang Yang, Jianhua Zhang and Zhongxun An were employed by the company Shanghai Aowei Technology Development Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Yuan, S.; Lai, Q.; Duan, X.; Wang, Q. Carbon-based materials as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries and lithium-ion capacitors: A review. J. Energy Storage 2023, 61, 106716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, T.S.; Kurra, N.; Wang, X.; Pinto, D.; Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Energy storage data reporting in perspective—Guidelines for interpreting the performance of electrochemical energy storage systems. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1902007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubal, D.P.; Ayyad, O.; Ruiz, V.; Gómez-Romero, P. Hybrid energy storage: The merging of battery and supercapacitor chemistries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1777–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatucci, G.G.; Badway, F.; Pasquier, A.D.; Zheng, T. An asymmetric hybrid nonaqueous energy storage cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148, A930–A939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarulzaman, N.; Elong, K.; Roshidah, R.; Chayed, N.F.; Badar, N.; Zainudin, L.W. Influence of carbon additives on cathode materials, LiCoO2 and LiMn2O4. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 545, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellikeri, A.; Zheng, J.-S.; Yturriaga, S.; Cao, W.; Zheng, J.P. Long cycle life LiFePO4/AC hybrid cathodes for lithium ion capacitors. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2017, MA2017-01, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.; Ma, Y. (LiNi0.5Co0.2Mn0.3O2+AC)/graphite hybrid energy storage device with high specific energy and high rate capability. J. Power Sources 2013, 243, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, E.; Ueda, T.; Ishihara, Y.; Ohshima, K.; Naoi, W.; Reid, M.T.H.; Naoi, K. High-voltage operation of Li4Ti5O12/AC hybrid supercapacitor cell in carbonate and sulfone electrolytes: Gas generation and its characterization. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 301, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Shen, G.; Chen, D. Recent progress and future prospects of sodium-ion capacitors. Sci. China Mater. 2019, 63, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, U.; Nadarajah, M.; Shah, R.; Milano, F. A review on rapid responsive energy storage technologies for frequency regulation in modern power systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Zou, K.; Deng, X.; Wang, B.; Zheng, M.; Li, L.; Hou, H.; Zou, G.; Ji, X. Comprehensive understanding of sodium-ion capacitors: Definition, mechanisms, configurations, materials, key technologies, and future developments. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 202003804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, J. Toward emerging sodium-based energy storage technologies: From performance to sustainability. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2201692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushenkov, A.M.; Ellis, A.V. Cell configurations and electrode materials for nonaqueous sodium-ion capacitors: The current state of the field. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2018, 2, 1800006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Qiu, R.; Li, G.; Shi, X.; Mao, Z.; Wang, R.; Jin, J.; He, B.; Gong, Y.; Wang, H. Electrospun Na3V2(PO4)3/carbon composite nanofibers as binder-free cathodes for advanced sodium-ion hybrid capacitors. Mater. Today Energy 2022, 30, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, T.; Yoon, M.; Li, S.; Wang, B.; Zheng, E.; Lee, J.; Sun, Y.; et al. Integrated rocksalt–polyanion cathodes with excess lithium and stabilized cycling. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganantham, R.; Chiu, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, C.; Liu, W. An efficient evaluation of F-doped polyanion cathode materials with long cycle life for Na-ion batteries applications. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Peng, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, H.; Huang, X. Research progress on Na3V2(PO4)3 cathode material of sodium ion battery. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 00635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Du, Z.; Świerczek, K.; Hou, Y. Micro/nano Na3V2(PO4)3/N-doped carbon composites with a hierarchical porous structure for high-rate pouch-type sodium-ion full-cell performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 8445–8454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hasa, I.; Buchholz, D.; Qin, B.; Passerini, S. Effects of nitrogen doping on the structure and performance of carbon coated Na3V2(PO4)3 cathodes for sodium-ion batteries. Carbon 2017, 124, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Dong, P.; Tong, H.; Zheng, J.-C.; Yu, W.; Zhang, J. CNT-decorated Na3V2(PO4)3 microspheres as a high-rate and cycle-stable cathode material for sodium ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 3590–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Chang, J.-K.; Majumder, S.B. High power Na3V2(PO4)3@C/AC bi-material cathodes for hybrid battery-capacitor energy storage devices. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 110546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Cai, J.; Sun, S.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G. “Nano reservoir” of dual energy storage mechanism for high-performance sodium ion capacitors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 27811–27821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Peng, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, G. Achieving high-energy–high-power density in a flexible quasi-solid-state sodium ion capacitor. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 5938–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cai, P.; Zou, G.-Q.; Hou, H.-S.; Ji, X.-B.; Tian, Y.; Long, Z. Ultra-stable carbon-coated sodium vanadium phosphate as cathode material for sodium-ion battery. Rare Met. 2022, 41, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Lv, Y.; Ma, C.; Pei, Y.; Liang, N.; Meng, F.; Dong, P.; Guo, J. Ultrafast activation to form through-hole carbon facilitates ion transport for high specific capacity supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2025, 644, 237129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Yang, Y.; Tan, X.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. Effects of cathode porosity on electrochemical and thermal behavior of high-rate lithium-ion batteries: Experimental and modeling study. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 537, 146814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Guo, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Rao, H.; Jian, Q.; Sun, J.; Ren, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, B.; et al. High-performance porous electrodes for flow batteries: Improvements of specific surface areas and reaction kinetics. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, B.; Li, D.; Xu, J. Mechanistic analysis on electrochemo-mechanics behaviors of lithium iron phosphate cathodes. Acta Mater. 2025, 292, 121024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Wang, T.; Shen, J.; Chen, P.; Yao, H.; Wang, Z. Na3V2(PO4)3/porous carbon skeleton embellished with ZIF-67 for sodium-ion storage. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 9252–9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yang, S.; Kim, S.; Song, J.; Park, J.; Doh, C.-H.; Ha, Y.-C.; Kwon, T.-S.; Lee, Y.M. Understanding the effects of diffusion coefficient and exchange current density on the electrochemical model of lithium-ion batteries. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2022, 34, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, W.; Xue, B.; Zhang, F.; Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Xiang, H. Ultrathin cellulose composite separator for high-energy density lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e09803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktekin, B.; Riegger, L.M.; Otto, S.-K.; Fuchs, T.; Henss, A.; Janek, J. SEI growth on Lithium metal anodes in solid-state batteries quantified with coulometric titration time analysis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, R.; Tan, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, F. Pseudocapacitance contribution in boron-doped graphite sheets for anion storage enables high-performance sodium-ion capacitors. Mater. Horiz. 2018, 5, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, R.; Kaliyappan, K.; Kang, K.; Sun, X.; Lee, Y.S. Going beyond lithium hybrid capacitors: Proposing a new high performing sodium hybrid capacitor system for next-generation hybrid vehicles made with bio-inspired activated carbon. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1502199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Raju, V.; Li, Z.; Xing, Z.; Hu, Y.S.; Ji, X. A high-power symmetric Na-ion pseudocapacitor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 5778–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.; Shaijumon, M.M. High performance sodium-ion hybrid capacitor based on Na2Ti2O4(OH)2 nanostructures. J. Power Sources 2017, 353, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Qi, L.; Wang, H. A Na+-storage electrode material free of potential plateaus and its application in electrochemical capacitors. Solid State Ion. 2016, 289, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhong, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, W.; Bu, X.-H. Ultra-small V2O3 embedded N-doped porous carbon nanorods with superior cycle stability for sodium-ion capacitors. J. Power Sources 2018, 405, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, L.; Xiao, B.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Ye, S.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Ouyang, X.; Hu, J.; et al. Revealing lithium battery gas generation for safer practical applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2208586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folaranmi, G.; Tauk, M.; Bechelany, M.; Sistat, P.; Cretin, M.; Zaviska, F. Investigation of fine activated carbon as a viable flow electrode in capacitive deionization. Desalination 2022, 525, 115500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Hu, J.; Robinson, J.B.; Rettie, A.J.E.; Miller, T.S. Predicting cell failure and performance decline in lithium-sulfur batteries using distribution of relaxation times analysis. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 101833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sullivan, N.P.; Zakutayev, A.; O’Hayre, R. How reliable is distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis? A dual regression-classification perspective on DRT estimation. interpretation, and accuracy. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 443, 141879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sediva, E.; Bonizzoni, S.; Caielli, T.; Mustarelli, P. Distribution of relaxation times as an accessible method to optimize the electrode structure of anion exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2023, 558, 232608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, A.; Salari, H.; Babaei, A.; Abdoli, H.; Aslannejad, H. Electrochemical evaluation of Sr2Fe1.5Mo0.5O6-δ/Ce0.9Gd0.1O1.95 cathode of SOFCs by EIS and DRT analysis. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 936, 117376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genieser, R.; Loveridge, M.; Bhagat, R. Practical high temperature (80 °C) storage study of industrially manufactured Li-ion batteries with varying electrolytes. J. Power Sources 2018, 386, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).