Recent Advances in the Catalytic Applications of Lanthanide-Oxo Clusters

Abstract

:1. Introduction

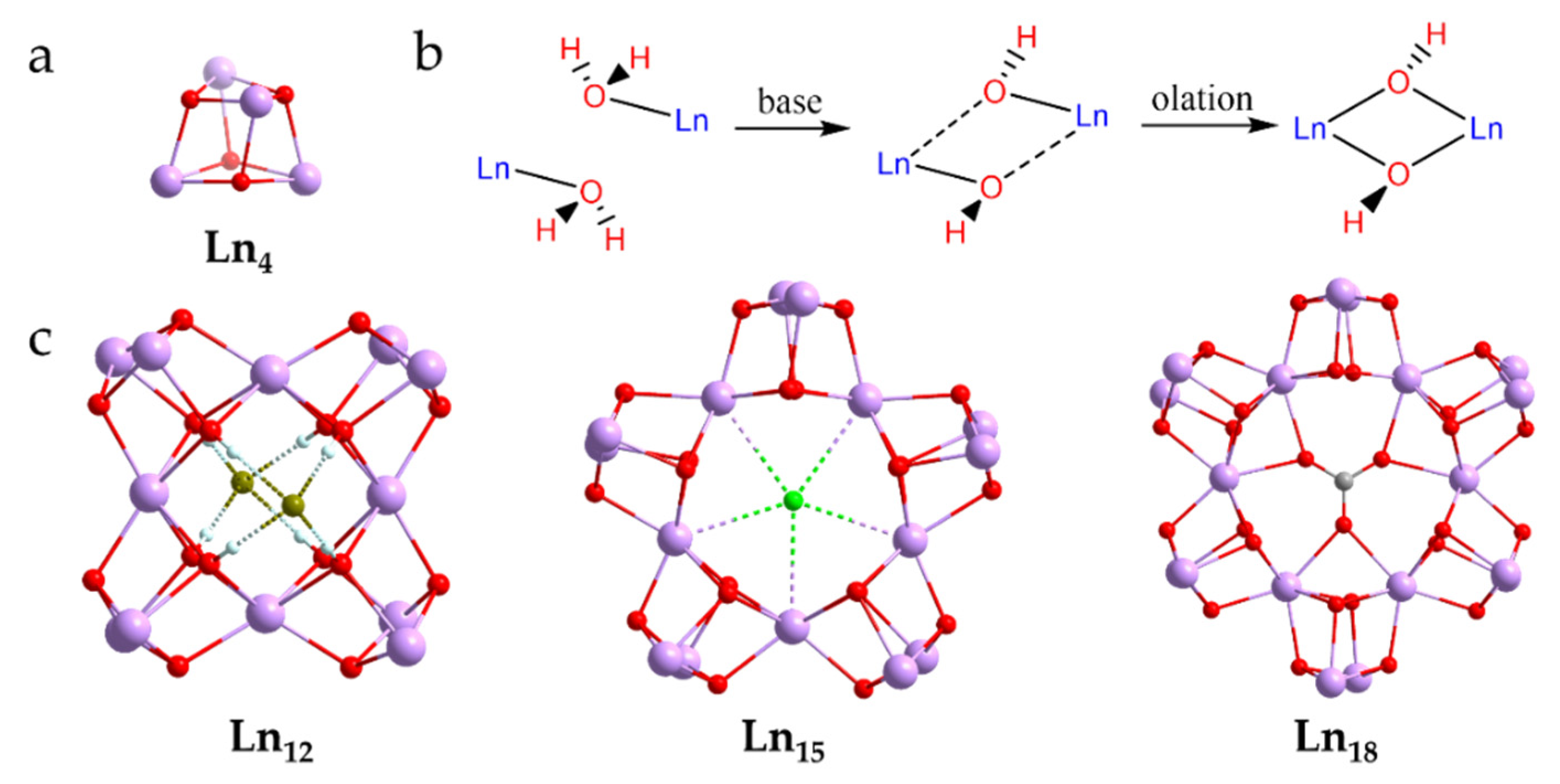

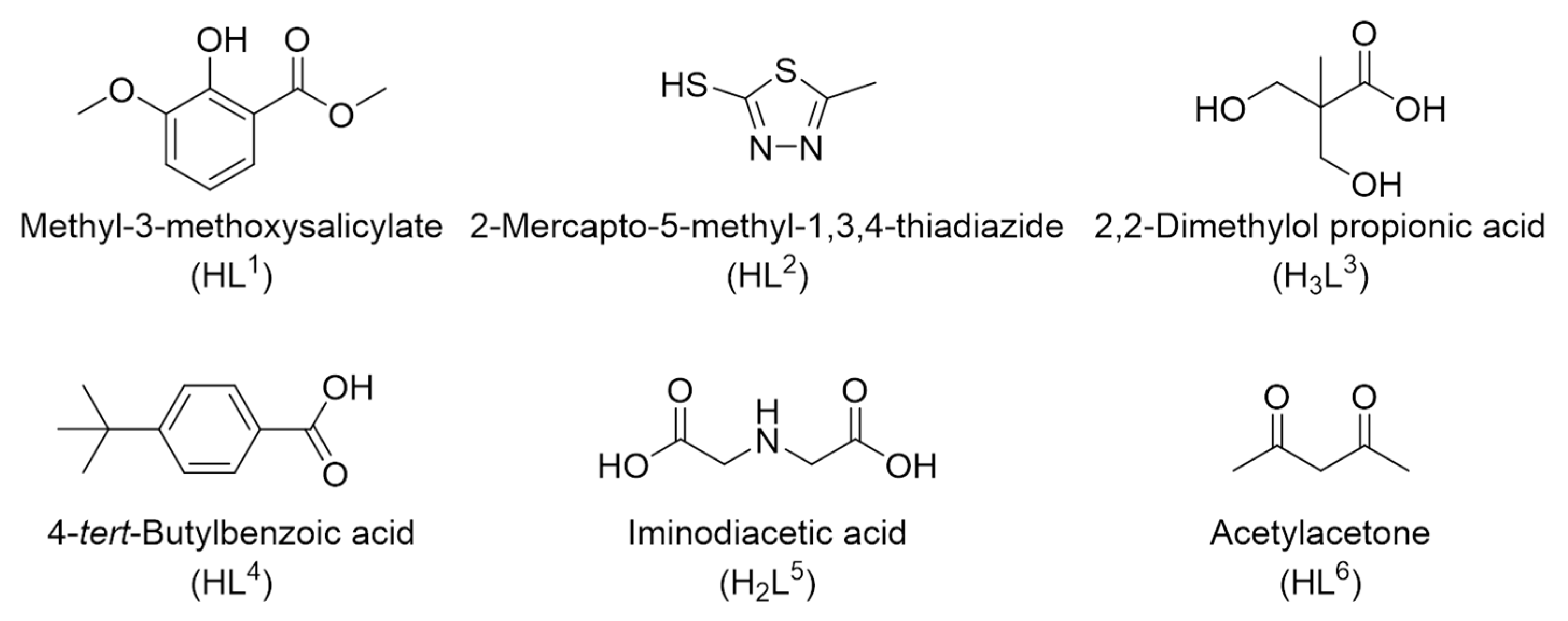

2. Developments on Synthetic Strategies and Characterizations

2.1. Synthetic Strategies

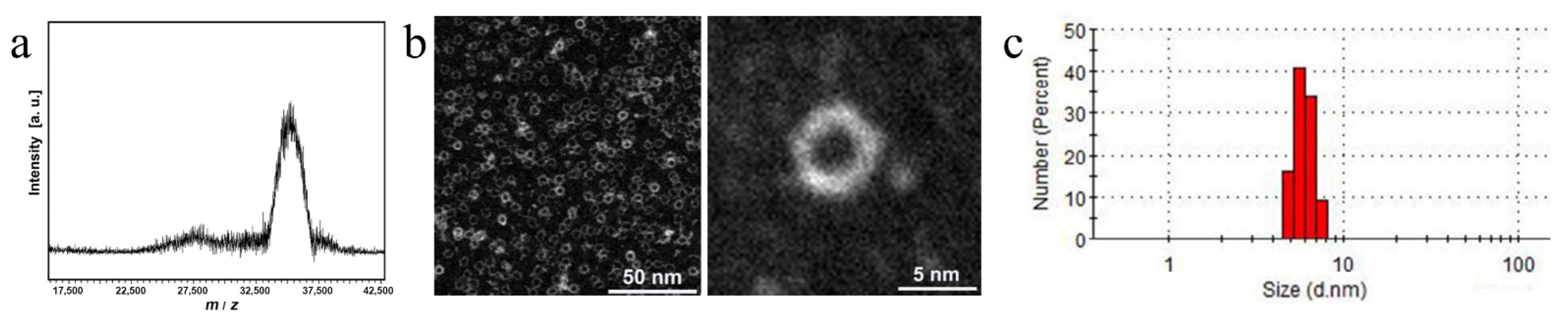

2.2. Characterizations

3. LOCs as Catalysts for CO2 Transformation into Value-Added Products

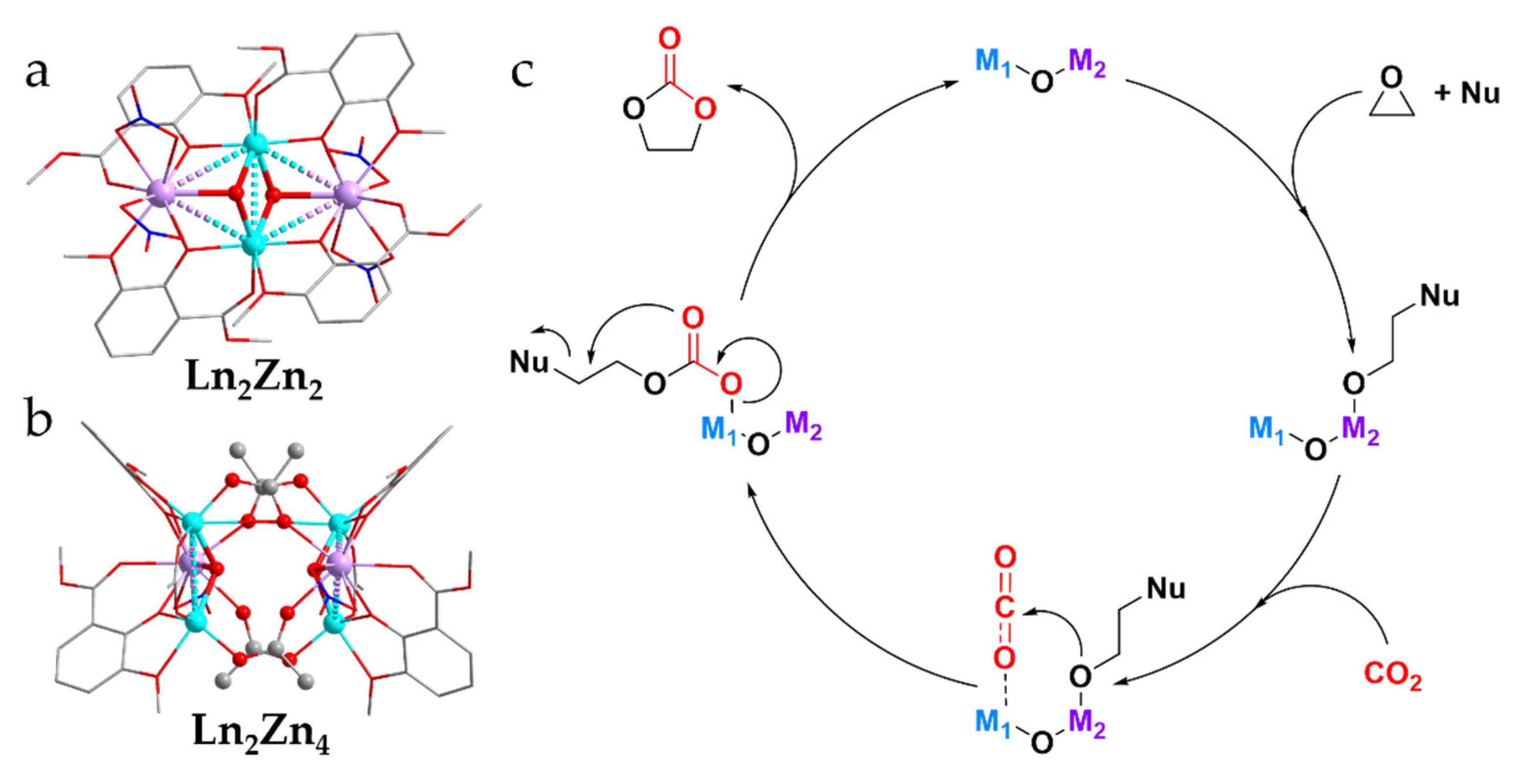

3.1. Catalytic Cycloaddition of CO2 and Epoxides

3.2. Catalytic Reduction of CO2

4. LOCs as Electrochemical Catalysts for Water Splitting

4.1. LOCs as Homogeneous Catalysts for Water Oxidation

4.2. LOCs as Heterogeneous Catalysts for Water Oxidation

4.3. LOCs as Catalysts for Hydrogen Production

5. LOCs as Catalysts for Hydroboration Reaction

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, Y.-Z.; Zhou, G.-J.; Zheng, Z.; Winpenny, R.E.P. Molecule-based magnetic coolers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Jiang, D.; Liu, J.; Ma, Y.; Schipper, D.; Jones, R.A. Large Ln42 coordination nanorings: NIR luminescence sensing of metal ions and nitro explosives. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 13116–13119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.T.; Roesky, P.W. Rare-Earth Metal Oxo/Hydroxo Clusters—Synthesis, Structures, and Applications. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakatouras, J.C.; Baxter, I.; Hursthouse, M.B.; Malik, K.M.A.; McAleese, J.; Drake, S.R. Synthesis and structural characterisation of two novel Gdβ-diketonates [Gd4(µ3-OH)4(µ2-H2O)2(H2O)4(hfpd)8]·2C6H6·H2O 1 and [Gd(hfpd)3(Me2CO)(H2O)] 2(hfpd–H = 1,1,1,5,5,5-hexafluoropentane-2,4-dione). J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994, 1994, 2455–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zheng, Z.; Jin, T.; Staples, R.J. Coordination Chemistry of Lanthanides at “High” pH: Synthesis and Structure of the Pentadecanuclear Complex of Europium(III) with Tyrosine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1813–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-J.; Sheng, T.-L.; Xia, S.-Q.; Leibeling, G.; Meyer, F.; Hu, S.-M.; Fu, R.-B.; Xiang, S.-C.; Wu, X.-T. Syntheses and Characterizations of a Series of Novel Ln6Cu24 Clusters with Amino Acids as Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 5472–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.-J.; Ren, Y.-P.; Chen, W.-X.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, R.-B.; Zheng, L.-S. A Four-Shell, Nesting Doll-like 3d–4f Cluster Containing 108 Metal Ions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2398–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.-Y.; Kong, X.-J.; Zheng, Z.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. High-Nuclearity Lanthanide-Containing Clusters as Potential Molecular Magnetic Coolers. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Guo, F.-S.; Tong, M.-L. Recent advances in the design of magnetic molecules for use as cryogenic magnetic coolants. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 281, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.-M.; Hu, Z.-B.; Lin, Q.-F.; Cheng, W.; Cao, J.-P.; Cui, C.-H.; Mei, H.; Song, Y.; Xu, Y. Exploring the Performance Improvement of Magnetocaloric Effect Based Gd-Exclusive Cluster Gd60. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11219–11222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Zhou, G.-J.; Yu, Y.-Z.; Nojiri, H.; Schröder, C.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Zheng, Y.-Z. Topological Self-Assembly of Highly Symmetric Lanthanide Clusters: A Magnetic Study of Exchange-Coupling “Fingerprints” in Giant Gadolinium(III) Cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 16405–16411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arnold, P.L.; McMullon, M.W.; Rieb, J.; Kühn, F.E. C—H Bond Activation by f-Block Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Díaz, L.M.; Snejko, N.; Iglesias, M.; Sánchez, F.; Gutiérrez-Puebla, E.; Monge, M.Á. Efficient Rare-Earth-Based Coordination Polymers as Green Photocatalysts for the Synthesis of Imines at Room Temperature. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 6883–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzamly, A.; Bakiro, M.; Hussein Ahmed, S.; Alnaqbi, M.A.; Nguyen, H.L. Rare-earth metal–organic frameworks as advanced catalytic platforms for organic synthesis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 425, 213543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Xu, Y.; Luo, F.; Du, Y. Rare earth double perovskites: A fertile soil in the field of perovskite oxides. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovarelli, A. Catalytic properties of ceria and CeO2-containing materials. Catal. Rev. 1996, 38, 439–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Schelter, E.J. Lanthanide Photocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2926–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Marks, T.J. Organolanthanide-Catalyzed Intramolecular Hydroamination/Cyclization of Aminoalkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 9295–9306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z. Ligand-controlled self-assembly of polynuclear lanthanide–oxo/hydroxo complexes: From synthetic serendipity to rational supramolecular design. Chem. Commun. 2001, 2001, 2521–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Selby, H.D.; Liu, H.; Carducci, M.D.; Jin, T.; Zheng, Z.; Anthis, J.W.; Staples, R.J. Halide-Templated Assembly of Polynuclear Lanthanide-Hydroxo Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Rotsch, D.A.; Messerle, L.; Zheng, Z. A systematic study of halide-template effects in the assembly of lanthanide hydroxide cluster complexes with histidine. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.-J.; Chen, W.-P.; Yu, Y.; Qin, L.; Han, T.; Zheng, Y.-Z. Filling the Missing Links of M3n Prototype 3d-4f and 4f Cyclic Coordination Cages: Syntheses, Structures, and Magnetic Properties of the Ni10Ln5 and the Er3n Wheels. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 12821–12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.-H.; Zheng, X.-Y.; Kong, X.-J.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. Synthetic Protocol for Assembling Giant Heterometallic Hydroxide Clusters from Building Blocks: Rational Design and Efficient Synthesis. Matter 2020, 3, 1334–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Xu, S.-H.; Zheng, X.-Y.; Yan, Z.-H.; Kong, X.-J.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. Four 3d–4f heterometallic Ln45M7 clusters protected by mixed ligands. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 2120–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.-Y.; Peng, J.-B.; Kong, X.-J.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. Mixed-anion templated cage-like lanthanide clusters: Gd27 and Dy27. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

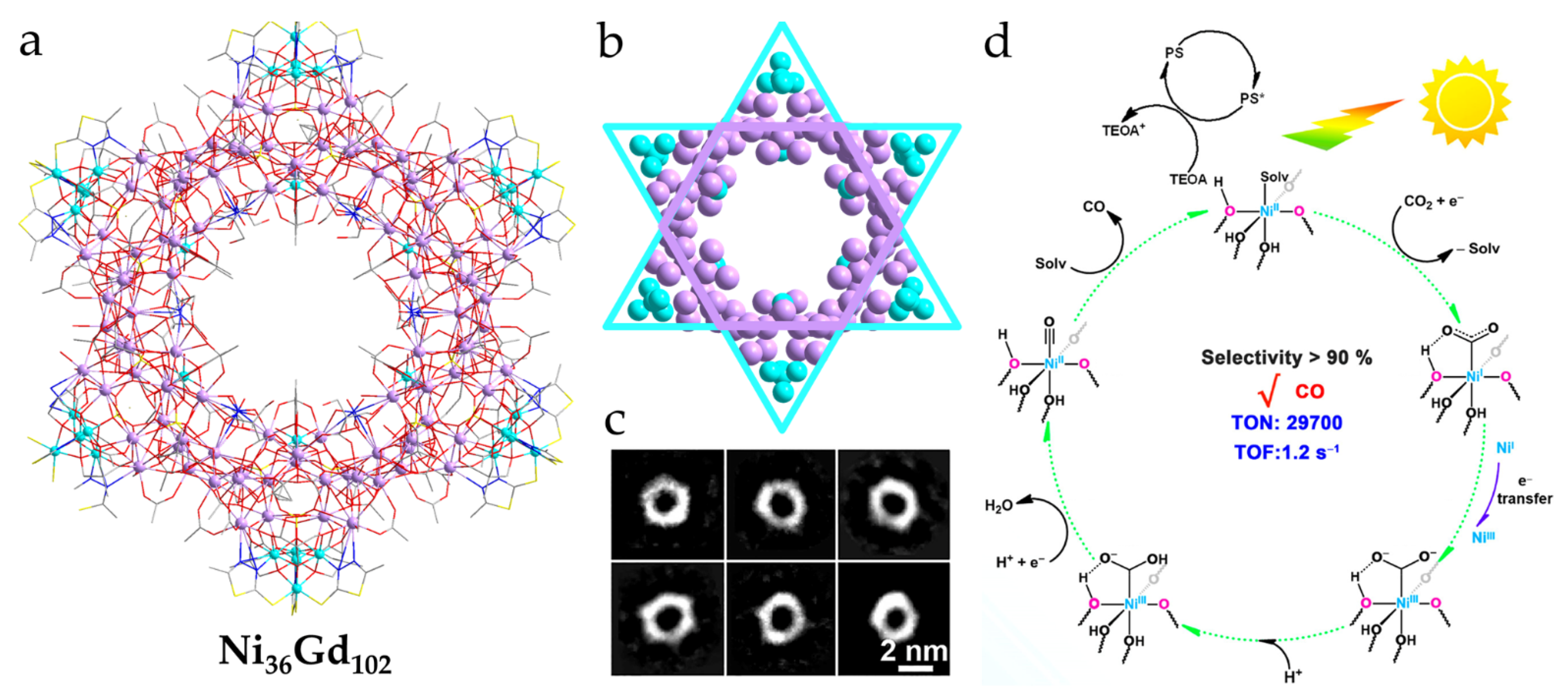

- Chen, W.-P.; Liao, P.-Q.; Jin, P.-B.; Zhang, L.; Ling, B.-K.; Wang, S.-C.; Chan, Y.-T.; Chen, X.-M.; Zheng, Y.-Z. The Gigantic Ni36Gd102 Hexagon: A Sulfate-Templated “Star-of-David” for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction and Magnetic Cooling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4663–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-H.; Zhuang, G.-L.; Liu, D.-P.; Liao, H.-G.; Kong, X.-J.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. A Gigantic Molecular Wheel of Gd140: A New Member of the Molecular Wheel Family. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18178–18181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pescarmona, P.P.; Taherimehr, M. Challenges in the catalytic synthesis of cyclic and polymeric carbonates from epoxides and CO2. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 2169–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakura, T.; Choi, J.-C.; Yasuda, H. Transformation of Carbon Dioxide. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2365–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Cui, P.; Shi, P.-F.; Cheng, P.; Zhao, B. Ultrastrong Alkali-Resisting Lanthanide-Zeolites Assembled by [Ln60] Nanocages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15988–15991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinchow, M.; Semakul, N.; Konno, T.; Rujiwatra, A. Lanthanide Coordination Polymers through Design for Exceptional Catalytic Performances in CO2 Cycloaddition Reactions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 8581–8591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, N.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Han, Z.-B.; Yuan, D.-Q. Pentanuclear Yb(III) cluster-based metal-organic frameworks as heterogeneous catalysts for CO2 conversion. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2017, 219, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, L.; Xu, C.; Yang, H.; Chen, W.; Gao, G.; Liu, W. Anion-induced 3d–4f luminescent coordination clusters: Structural characteristics and chemical fixation of CO2 under mild conditions. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 7159–7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Xu, C.; Han, Q.; Tang, X.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, R.; Gao, G.; Xu, B.; Qin, W.; Liu, W. Ambient chemical fixation of CO2 using a highly efficient heterometallic helicate catalyst system. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2212–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, D.; Yao, Y. Cooperative rare earth metal–zinc based heterometallic catalysts for copolymerization of CO2 and cyclohexene oxide. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4270–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuzumi, S.; Lee, Y.-M.; Ahn, H.S.; Nam, W. Mechanisms of catalytic reduction of CO2 with heme and nonheme metal complexes. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 6017–6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, J.; Huang, Y.; Ye, W.; Li, Y. CO2 Reduction: From the Electrochemical to Photochemical Approach. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1700194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, T. Photocatalytic Carbon Dioxide Reduction Using Nickel Complexes as Catalysts. ChemPhotoChem 2021, 5, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, T.; Huang, H.-H.; Wang, J.-W.; Zhong, D.-C.; Lu, T.-B. A Dinuclear Cobalt Cryptate as a Homogeneous Photocatalyst for Highly Selective and Efficient Visible-Light Driven CO2 Reduction to CO in CH3CN/H2O Solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.; Kawanishi, T.; Tsukakoshi, Y.; Kotani, H.; Ishizuka, T.; Kojima, T. Efficient Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction by a Ni(II) Complex Having Pyridine Pendants through Capturing a Mg2+ Ion as a Lewis-Acid Cocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 20309–20317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.-H.; Mathew, S.; Hessels, J.; Reek, J.N.H.; Yu, F. Homogeneous Catalysts Based on First-Row Transition-Metals for Electrochemical Water Oxidation. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Wang, L.; Li, F.; Li, F.; Sun, L. Highly Efficient Bioinspired Molecular Ru Water Oxidation Catalysts with Negatively Charged Backbone Ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2084–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhao, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Wei, P.; Huang, H.; Liu, Q.; Li, T.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Recent Advances in the Development of Water Oxidation Electrocatalysts at Mild pH. Small 2019, 15, 1805103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

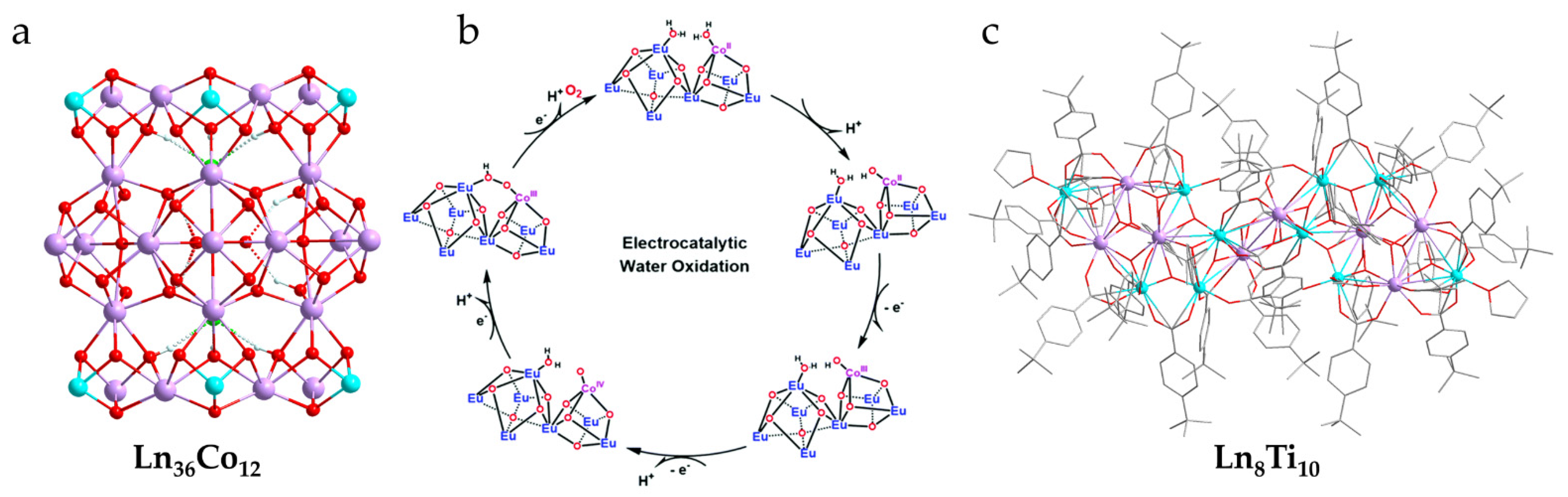

- Chen, R.; Chen, C.-L.; Du, M.-H.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Long, L.-S.; Kong, X.-J.; Zheng, L.-S. Soluble lanthanide-transition-metal clusters Ln36Co12 as effective molecular electrocatalysts for water oxidation. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 3611–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.-F.; Kong, X.-J.; Lu, T.-B.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. Heterometallic Lanthanide–Titanium Oxo Clusters: A New Family of Water Oxidation Catalysts. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Li, Z. Robust Ti- and Zr-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks for Photocatalysis. Chin. J. Chem. 2017, 35, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, R.; Li, N.; Wang, M.; Ren, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, C. Realizing high performance solar water oxidation for Ti-doped hematite nanoarrays by synergistic decoration with ultrathin cobalt-iron phosphate nanolayers. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 355, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J. TiO2 photocatalyst for water treatment applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, A.; Nishioka, S.; Maeda, K. Water Splitting on Rutile TiO2-Based Photocatalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 18204–18219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-J.; Chen, D.; Yu, Z.-T.; Zou, Z.-G. Cadmium sulfide-based nanomaterials for photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 11606–11630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Ren, D.; Ding, Y.; Guan, Y.; Ng, Y.H.; Zhang, P.; Li, X. Nanostructured CdS for efficient photocatalytic H2 evolution: A review. Sci. China Mater. 2020, 63, 2153–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X. Lanthanide-doped semiconductor nanocrystals: Electronic structures and optical properties. Sci. China Mater. 2015, 58, 819–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, R.; Yan, Z.-H.; Kong, X.-J.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. Integration of Lanthanide–Transition-Metal Clusters onto CdS Surfaces for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16796–16800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Eisen, M.S. Organo-f-Complexes for Efficient and Selective Hydroborations. Synthesis 2020, 52, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

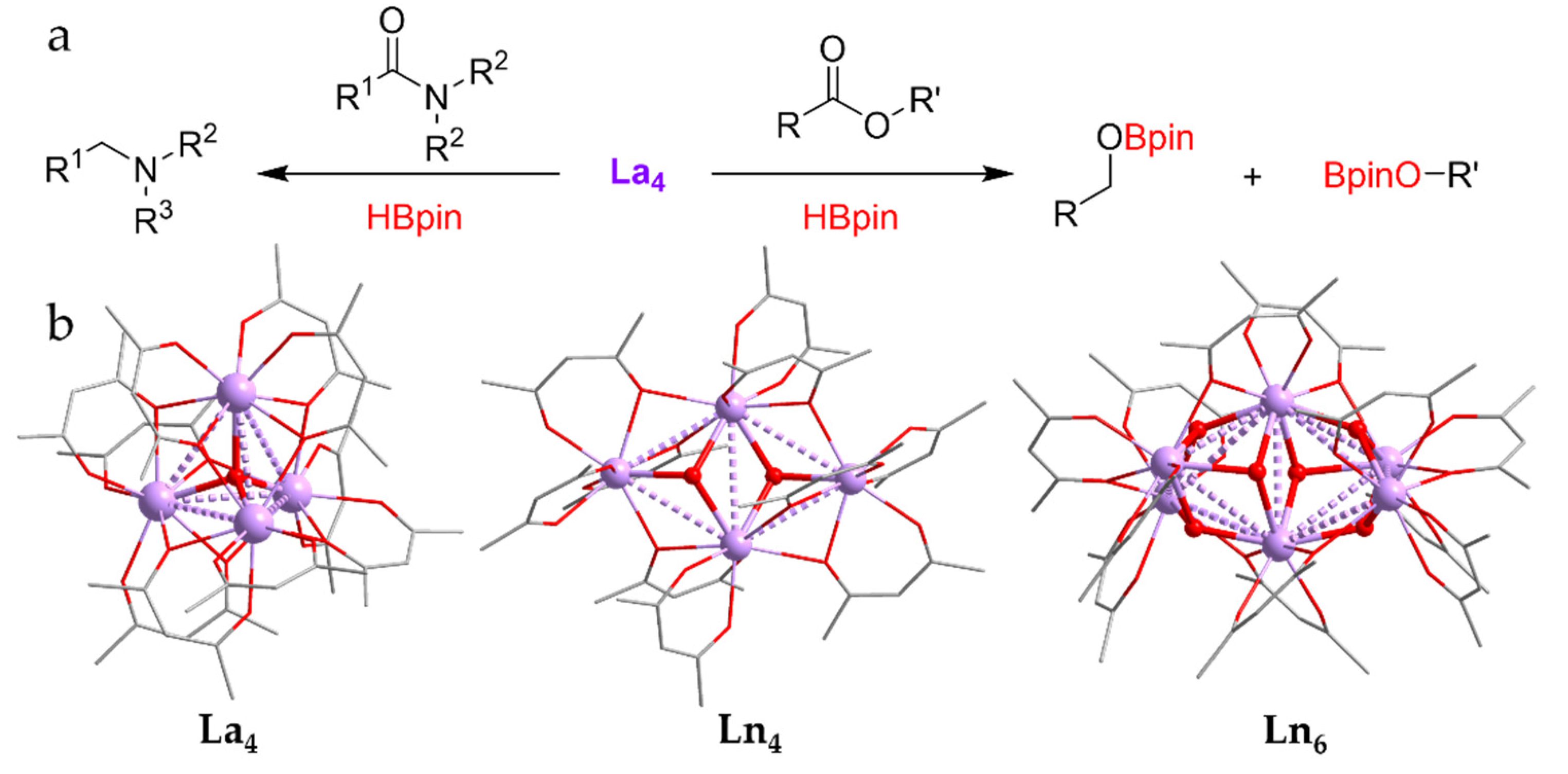

- Tamang, S.R.; Singh, A.; Bedi, D.; Bazkiaei, A.R.; Warner, A.A.; Glogau, K.; McDonald, C.; Unruh, D.K.; Findlater, M. Polynuclear lanthanide–diketonato clusters for the catalytic hydroboration of carboxamides and esters. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, W.; Liu, Q.; Chen, W.; Feng, M.; Zheng, Z. Recent Advances in the Catalytic Applications of Lanthanide-Oxo Clusters. Magnetochemistry 2021, 7, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry7120161

Huang W, Liu Q, Chen W, Feng M, Zheng Z. Recent Advances in the Catalytic Applications of Lanthanide-Oxo Clusters. Magnetochemistry. 2021; 7(12):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry7120161

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Weiming, Qingxin Liu, Wanmin Chen, Min Feng, and Zhiping Zheng. 2021. "Recent Advances in the Catalytic Applications of Lanthanide-Oxo Clusters" Magnetochemistry 7, no. 12: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry7120161

APA StyleHuang, W., Liu, Q., Chen, W., Feng, M., & Zheng, Z. (2021). Recent Advances in the Catalytic Applications of Lanthanide-Oxo Clusters. Magnetochemistry, 7(12), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry7120161