A Novel Family of Triangular CoII2LnIII and CoII2YIII Clusters by the Employment of Di-2-Pyridyl Ketone †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

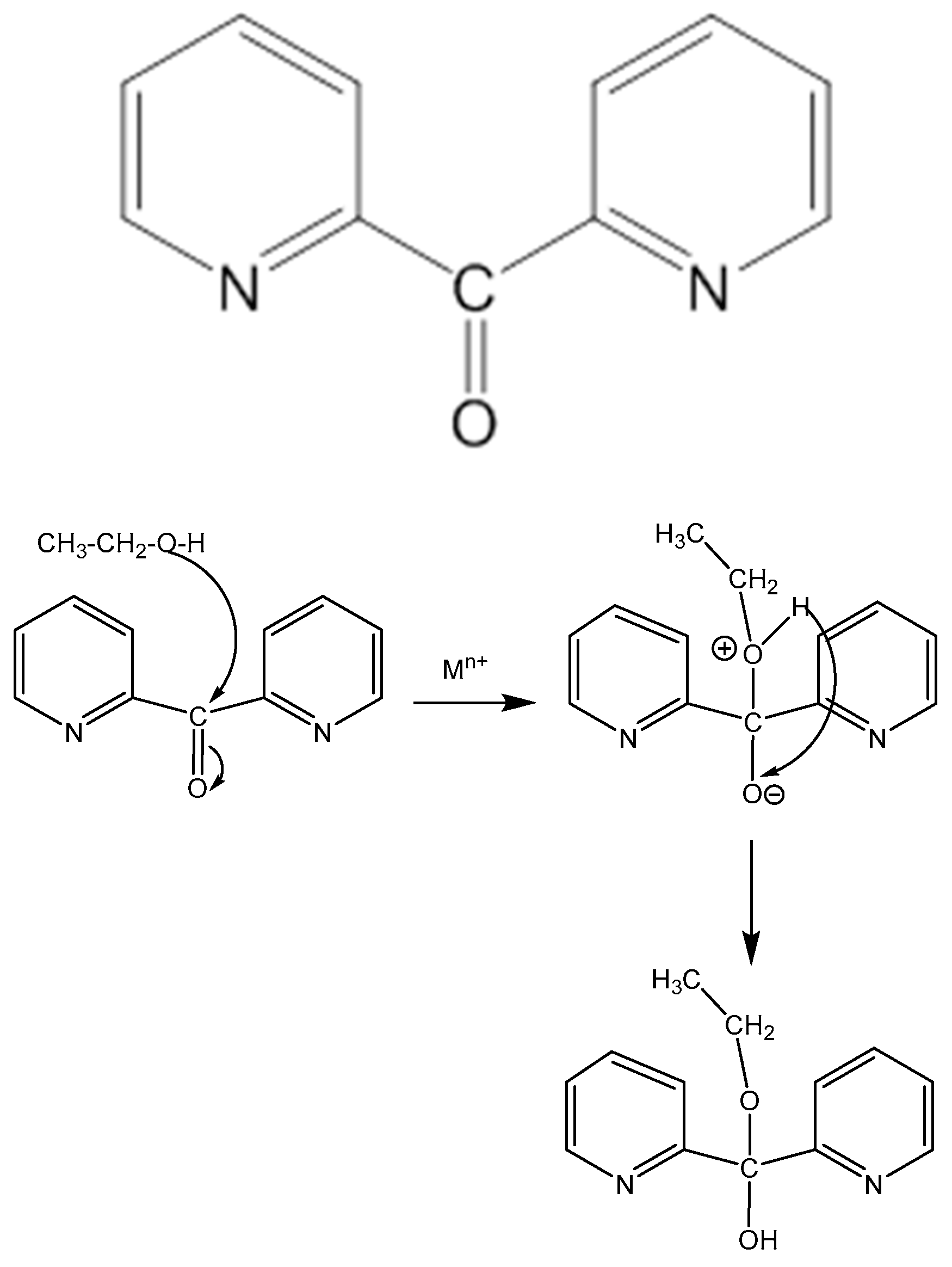

2.1. Synthetic Comments

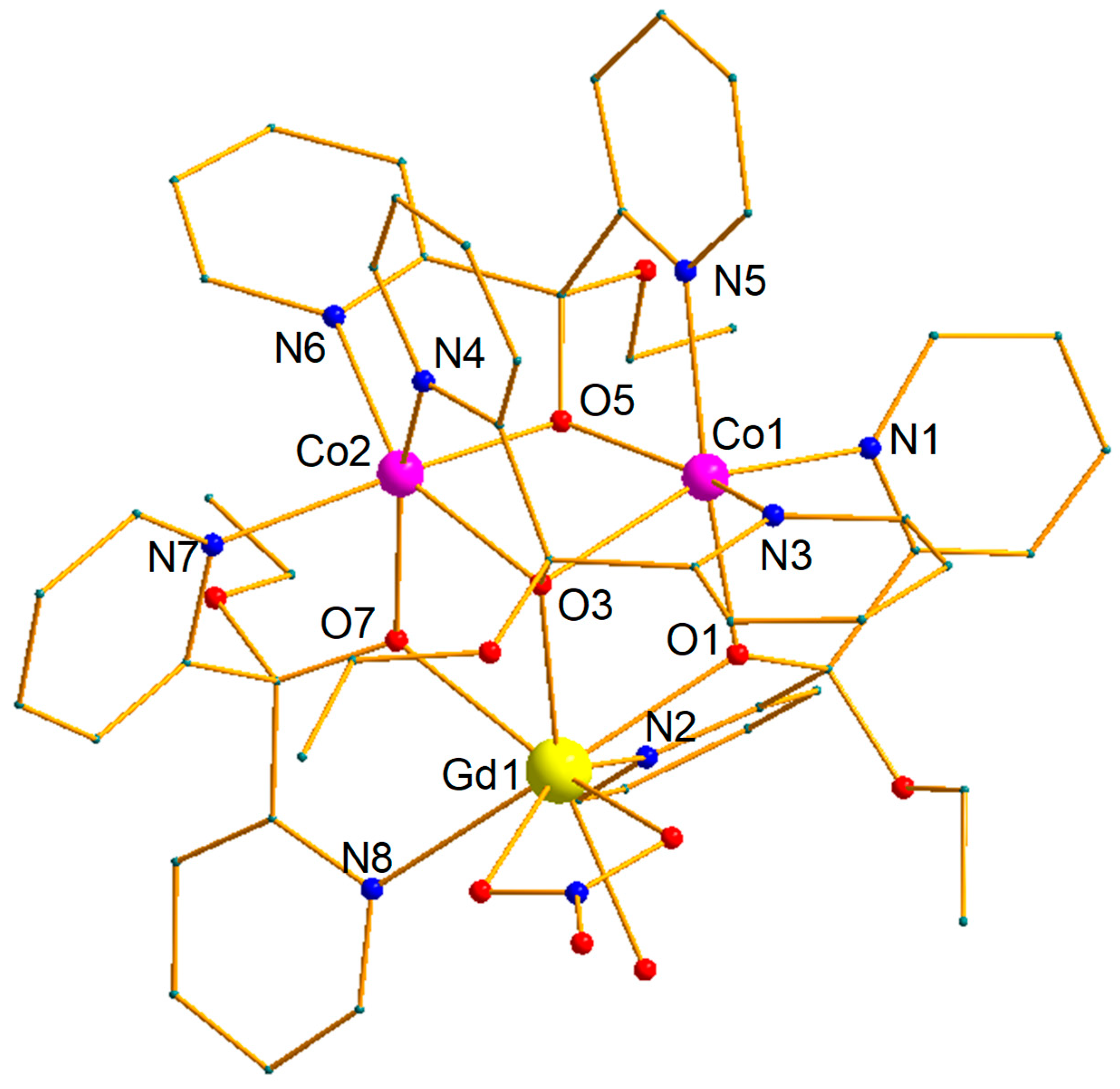

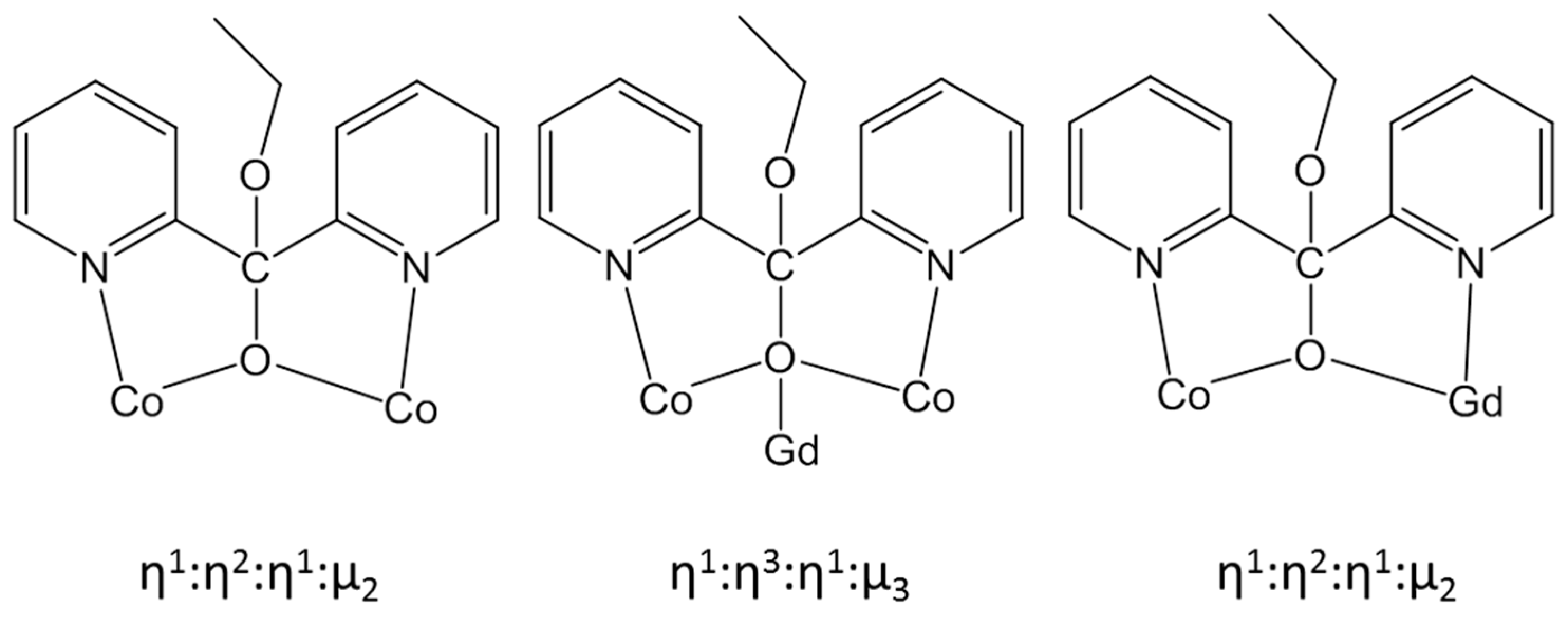

2.2. Description of Structures

2.3. Magnetism Studies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials, Physical and Spectroscopic Measurements

3.2. Synthesis of [Co2Gd{(py)2C(OEt)(O)}4(NO3)(H2O)]2[Gd(NO3)5](ClO4)2 (1)

3.3. Synthesis of [Co2Dy{(py)2C(OEt)(O)}4(NO3)(H2O)]2[Dy(NO3)5](ClO4)2 (2)

3.4. Synthesis of [Co2Tb{(py)2C(OEt)(O)}4(NO3)(H2O)]2[Tb(NO3)5](ClO4)2 (3)

3.5. Synthesis of [Co2Y{(py)2C(OEt)(O)}4(NO3)(H2O)]2[Y(NO3)5](ClO4)2 (4)

3.6. Single-Crystal X-ray Crystallography

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosado Piquer, L.; Sañudo, E.C. Heterometallic 3d–4f single-molecule magnets. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 8771–8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Shia, W.; Cheng, P. Toward heterometallic single-molecule magnets: Synthetic strategy, structures and properties of 3d–4f discrete complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 289–290, 74–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, J.W.; Collison, D. The coordination chemistry and magnetism of some 3d–4f and 4f amino-polyalcohol compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 260, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.P.; Liao, P.Q.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, X.-M.; Zheng, Y.Z. A Mixed-Ligand Approach for a Gigantic and Hollow Heterometallic Cage {Ni64RE96} for Gas Separation and Magnetic Cooling Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9375–9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.J.; Long, L.-S.; Huang, R.B.; Zheng, L.-S.; Harris, T.D.; Zheng, Z. A four-shell, 136-metal 3d-4f heterometallic cluster approximating a rectangular parallelepiped. Chem. Commun. 2009, 4354–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.J.; Ren, Y.P.; Chen, W.X.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, R.-B.; Zheng, L.-S. A Four-Shell, Nesting Doll-like 3d–4f Cluster Containing 108 Metal Ions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2398–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.-D.; Liu, J.-L.; Tong, M.-L. Unique nanoscale {CuII36LnIII24} (Ln = Dy and Gd) metallo-rings. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 5286–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.-B.; Zhang, Q.-C.; Kong, X.-L.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Ren, Y.-P.; Long, L.-S.; Huang, R.-B.; Zheng, L.-S.; Zheng, Z. High-Nuclearity 3d−4f Clusters as Enhanced Magnetic Coolers and Molecular Magnets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3314–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.J.; Ren, Y.P.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, Z.; Nichol, G.; Huang, R.-B.; Zheng, L.-S. Dual Shell-like Magnetic Clusters Containing NiII and LnIII (Ln = La, Pr, and Nd) Ions. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 2728–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.J.; Ren, Y.P.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, R.-B.; Zheng, L.-S. A Keplerate Magnetic Cluster Featuring an Icosidodecahedron of Ni(II) Ions Encapsulating a Dodecahedron of La(III) Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 7016–7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagai, R.; Christou, G. The Drosophila of single-molecule magnetism: [Mn12O12(O2CR)16(H2O)4]. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, G.; Gatteschi, D.; Hendrickson, D.N.; Sessoli, R. Single-Molecule Magnets. MRS Bull. 2000, 25, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernsdorfer, W.; Bogani, L. Molecular spintronics using single-molecule magnets. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, S.; Edwards, R.S.; Aliaga-Alcalde, N.; Christou, G. Quantum Coherence in an Exchange-Coupled Dimer of Single-Molecule Magnets. Science 2003, 302, 1015–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiron, R.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Aliaga-Alcalde, N.; Christou, G. Quantum tunneling in a three-dimensional network of exchange-coupled single-molecule magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 140407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.N.; Lan, Y.; AlDamen, M.A.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Anson, C.E.; Powell, A.K. Effect of ligand substitution on the SMM properties of three isostructural families of double-cubane Mn4Ln2 coordination clusters. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 3485–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Abboud, K.A.; Christou, G. Mn21Dy Cluster with a Record Magnetization Reversal Barrier for a Mixed 3d/4f Single-Molecule Magnet. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holynska, M.; Premuzic, D.; Jeon, I.-R.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Clérac, R.; Dehnen, S. [MnIII6O3Ln2] Single-Molecule Magnets: Increasing the Energy Barrier Above 100 K. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 9605–9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatatos, T.C.; Teat, S.J.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Christou, G. Enhancing the Quantum Properties of Manganese-Lanthanide Single-Molecule Magnets: Observation of Quantum Tunneling Steps in the Hysteresis Loops of a {Mn12Gd} Cluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereacre, V.; Ako, A.M.; Clerac, R.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Filoti, G.; Bartolome, J.; Anson, C.E.; Powell, A.K. A Bell-Shaped Mn11Gd2 Single-Molecule Magnet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 9248–9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereacre, V.; Ako, A.M.; Clerac, R.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Hewitt, I.J.; Anson, C.E.; Powell, A.K. Heterometallic [Mn5-Ln4] Single-Molecule Magnets with High Anisotropy Barriers. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3577–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.-X.; Shi, W.-S.; Cheng, P. A {Tb2Fe3} Pyramid Single-Molecule Magnet with Ferromagnetic Tb-Fe Interaction. Chin. J. Chem. 2019, 37, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniodeh, A.; Liang, Y.; Anson, C.E.; Magnani, N.; Powell, A.K.; Unterreiner, A.N.; Seyfferle, S.; Slota, M.; Dressel, M.; Bogani, L.; et al. Unraveling the Influence of Lanthanide Ions on Intra- and Inter-Molecular Electronic Processes in Fe10Ln10 Nano-Toruses. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 6280–6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia-Romano, L.; Bartolomé, F.; Bartolomé, J.; Luzón, J.; Prodius, D.; Turta, C.; Mereacre, V.; Wilhelm, F.; Rogalev, A. Field-induced internal Fe and Ln spin reorientation in butterfly {Fe3LnO2} (Ln = Dy and Gd) single-molecule magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 184403:1–184403:11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Prodius, D.; Mereacre, V.; Kostakis, G.E.; Powell, A.K. Unprecedented chemical transformation: Crystallographic evidence for 1,1,2,2-tetrahydroxyethane captured within an Fe6Dy3 single molecule magnet. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1696–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, C.G.; Stamatatos, T.C.; Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Tasiopoulos, A.J.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Perlepes, S.P.; Christou, G. Nickel/Lanthanide Single-Molecule Magnets: {Ni3Ln} “Stars” with a Ligand Derived from the Metal-Promoted Reduction of Di-2-pyridyl Ketone under Solvothermal Conditions. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 9737–9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Xiang, S.; Sheng, T.; Yuan, D.; Shen, C.; Tan, C.; Hua, S.; Wu, X. A series of goblet-like heterometallic pentanuclear [LnIIICuII4] clusters featuring ferromagnetic coupling and single-molecule magnet behavior. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 10736–10738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ida, Y.; Ishida, T.; Ghosh, A. Linker Stoichiometry-Controlled Stepwise Supramolecular Growth of a Flexible Cu2Tb Single Molecule Magnet from Monomer to Dimer to One-Dimensional Chain. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 2588–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose Heras Ojea, M.; Milway, V.A.; Velmurugan, G.A.; Thomas, L.H.; Coles, S.J.; Wilson, C.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Rajaraman, G.; Murrie, M. Enhancement of TbIII–CuII Single-Molecule Magnet Performance through Structural Modification. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 12839–12848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskar, V.; Gopal, K.; Helliwell, M.; Tuna, F.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Winpenny, R.E.P. 3d–4f Clusters with large spin ground states and SMM behavior. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 4747–4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-L.; Min, F.-Y.; Wang, C.; Lin, S.-Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J. Utilizing 3d-4f magnetic interaction to slow the magnetic relaxation of heterometallic complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 4337–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, V.; Pandian, B.M.; Azhakar, R.; Vittal, J.J.; Clérac, R. Linear Trinuclear Mixed-Metal CoII−GdIII−CoII Single-Molecule Magnet: [L2Co2Gd][NO3]2CHCl3(LH3 = (S)P[N(Me)N=CH−C6H3-2-OH-3-OMe]3). Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 5140–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funes, A.V.; Carrella, L.; Rentschler, E.; Alborés, P. {CoIII2DyIII2} single molecule magnet with two resolved thermal activated magnetization relaxation pathways at zero field. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 2361–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatatos, T.C.; Efthymiou, C.G.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Perlepes, S.P. Adventures in the Coordination Chemistry of Di-2-pyridyl Ketone and Related Ligands: From High-Spin Molecules and Single-Molecule Magnets to Coordination Polymers, and from Structural Aesthetics to an Exciting New Reactivity Chemistry of Coordinated Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 2009, 3361–3391. [Google Scholar]

- Papaefstathiou, G.S.; Perlepes, S.P. Families of Polynuclear Manganese, Cobalt, Nickel and Copper Complexes Stabilized by Various Forms of Di-2-pyridyl Ketone. Comments Inorg. Chem. 2002, 23, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, C.G.; Georgopoulou, A.N.; Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Terzis, A.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Escuer, A.; Perlepes, S.P. Initial employment of di-2-pyridyl ketone as a route to nickel(II)/lanthanide(III) clusters: Triangular Ni2Ln complexes. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 8603–8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, A.N.; Efthymiou, C.G.; Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Psycharis, V.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Manos, M.; Tasiopoulos, A.; Escuer, A.; Perlepes, S.P. Triangular NiII2LnIII and NiII2YIII complexes derived from di-2-pyridyl ketone: Synthesis, structures and magnetic properties. Polyhedron 2011, 30, 2978–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Stamatatos, T.C.; Efthymiou, C.G.; Cunha-Silva, L.; Almeida Paz, F.; Perlepes, S.P.; Christou, G. A High-Nuclearity 3d/4f Metal Oxime Cluster: An Unusual Ni8Dy8 “Core-Shell” Complex from the Use of 2-Pyridinealdoxime. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 9743–9745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzou, C.D.; Efthymiou, C.G.; Escuer, A.; Cunha-Silva, L.; Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Perlepes, S.P. In search of 3d/4f-metal single-molecule magnets: Nickel(II)/lanthanide(III) coordination clusters. Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Estrader, M.; Efthymiou, C.G.; Dermitzaki, D.; Gkotsis, K.; Terzis, A.; Diaz, C.; Perlepes, S.P. In search for mixed transition metal/lanthanide single-molecule magnets: Synthetic routes to NiII/TbIII and NiII/DyIII clusters featuring a 2-pyridyl oximate ligand. Polyhedron 2009, 28, 1652–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, M.; Skordi, K.; Fournet, A.D.; Thuijs, A.E.; Christou, G.; Perlepes, S.P.; Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Tasiopoulos, A.J. Heterometallic MnIII4Ln2 (Ln = Dy, Gd, Tb) Cross-Shaped Clusters and Their Homometallic MnIII4MnII2 Analogues. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 5657–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Thorp, H.H. Bond Valence Sum Analysis of Metal-Ligand Bond Lengths in Metalloenzymes and Model Complexes. 2. Refined Distances and Other Enzymes. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 4102–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Martinez, A.; Casanova, D.; Alvarez, S. Polyhedral Structures with an Odd Number of Vertices: Nine-Coordinate Metal Compounds. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llunell, M.; Casanova, D.; Girera, J.; Alemany, P.; Alvarez, S. SHAPE, version 2.0; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulou, A.N.; Adam, R.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Psycharis, V.; Ballesteros, R.; Abarca, B.; Boudalis, A.K. Expanding the 3d-4f heterometallic chemistry of the (py)2CO and pyCOpyCOpy ligands: Structural, magnetic and Mössbauer spectroscopic studies of two FeII–GdIII complexes. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 8199–8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandropoulos, D.I.; Cunha-Silva, L.; Tang, J.; Stamatatos, T.C. Heterometallic Cu/Ln cluster chemistry: Ferromagnetically-coupled {Cu4Ln2} complexes exhibiting single-molecule magnetism and magnetocaloric properties. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 11934–11941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, P. Lanthanide Single Molecule Magnets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lloret, F.; Julve, M.; Cano, J.; Ruiz-García, R.; Pardo, E. Magnetic properties of six-coordinated high-spin cobalt(II) complexes: Theoretical background and its application. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2008, 361, 3432–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Luo, F.; Zheng, J.-M. Syntheses, Structures, and Magnetic Properties of a Series of Heterotri-, Tetra- and Pentanuclear LnIII–CoII Compounds. Polymers 2019, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé, J.; Filoti, G.; Kuncser, V.; Schinteie, G.; Mereacre, V.; Anson, C.E.; Powell, A.K.; Prodius, D.; Turta, C. Magnetostructural correlations in the tetranuclear series of {Fe3LnO2} butterfly core clusters:Magnetic and Mössbauer spectroscopic study. Phys. Rev. B. 2009, 80, 014430:1–014430:16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Diffraction. CrysAlis CCD and CrysAlis RED, version 1.171.32.15; Oxford Diffraction Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Altomare, A.; Cascarano, G.; Giaconazzo, C.; Guagliardi, A.; Burla, M.C.; Polidori, G.; Camalli, M. SIR92: A program for automatic solution of crystal structures by direct methods. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1994, 27, 435–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXL97; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXL-2014/7; Program for Refinement of Crystal Structures, University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX suite for small-molecule single-crystal crystallography. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1999, 32, 837–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K. DIAMOND; Version 3.1d; Crystal Impact GbR: Bonn, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Macrae, C.F.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Shields, G.P.; Taylor, R.; Towler, M.; Van de Streek, J. Mercury: Visualization and analysis of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006, 39, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Sluis, P.; Spek, A.L. BYPASS: An Effective Method for the Refinement of Crystal Structures Containing Disordered Solvent Regions. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found Crystallogr. 1990, A46, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gd(1)-O(1) | 2.252(15) | Co(1)-N(5) | 2.220(20) |

| Gd(1)-O(3) | 2.387(15) | Co(2)-O(3) | 2.142(13) |

| Gd(1)-O(7) | 2.304(13) | Co(2)-O(5) | 2.048(14) |

| Gd(1)-N(2) | 2.582(17) | Co(2)-O(7) | 2.046(14) |

| Gd(1)-N(8) | 2.578(19) | Co(2)-N(4) | 2.070(16) |

| Co(1)-O(1) | 2.021(15) | Co(2)-N(6) | 2.08(2) |

| Co(1)-O(3) | 2.265(15) | Co(2)-N(7) | 2.176(19) |

| Co(1)-O(5) | 1.984(16) | Gd(1)-Co(1) | 3.471(3) |

| Co(1)-N(1) | 2.083(18) | Gd(1)-Co(2) | 3.546(3) |

| Co(1)-N(3) | 2.093(19) | Co(1)-Co(2) | 3.192(4) |

| Co(1)-O(1)-Gd(1) | 108.5(6) | Co(2)-O(7)-Gd(1) | 109.1(5) |

| Co(1)-O(3)-Gd(1) | 96.5(5) | Co(1)-O(3)-Co(2) | 92.8(5) |

| Co(2)-O(3)-Gd(1) | 102.9(6) | Co(1)-O(5)-Co(2) | 104.6(7) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Efthymiou, C.G.; Ní Fhuaráin, Á.; Mayans, J.; Tasiopoulos, A.; Perlepes, S.P.; Papatriantafyllopoulou, C. A Novel Family of Triangular CoII2LnIII and CoII2YIII Clusters by the Employment of Di-2-Pyridyl Ketone. Magnetochemistry 2019, 5, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry5020035

Efthymiou CG, Ní Fhuaráin Á, Mayans J, Tasiopoulos A, Perlepes SP, Papatriantafyllopoulou C. A Novel Family of Triangular CoII2LnIII and CoII2YIII Clusters by the Employment of Di-2-Pyridyl Ketone. Magnetochemistry. 2019; 5(2):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry5020035

Chicago/Turabian StyleEfthymiou, Constantinos G., Áine Ní Fhuaráin, Júlia Mayans, Anastasios Tasiopoulos, Spyros P. Perlepes, and Constantina Papatriantafyllopoulou. 2019. "A Novel Family of Triangular CoII2LnIII and CoII2YIII Clusters by the Employment of Di-2-Pyridyl Ketone" Magnetochemistry 5, no. 2: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry5020035

APA StyleEfthymiou, C. G., Ní Fhuaráin, Á., Mayans, J., Tasiopoulos, A., Perlepes, S. P., & Papatriantafyllopoulou, C. (2019). A Novel Family of Triangular CoII2LnIII and CoII2YIII Clusters by the Employment of Di-2-Pyridyl Ketone. Magnetochemistry, 5(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry5020035