Fabrication of Spindle-like ZnO@Fe3O4 Nanocarriers for Targeted Drug Delivery and Controlled Release

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs

2.2. Material Characterizations

2.3. In Vitro DOX Loading and Release

2.3.1. PH-Dependent Drug Release

2.3.2. NIR Triggered Drug Release

2.4. Cell Viability

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Material Characterization

3.2. Photothermal and Magnetic Properties Measurements

3.3. External Release Experiment of ZnO@Fe3O4-DOX Nanocomposites

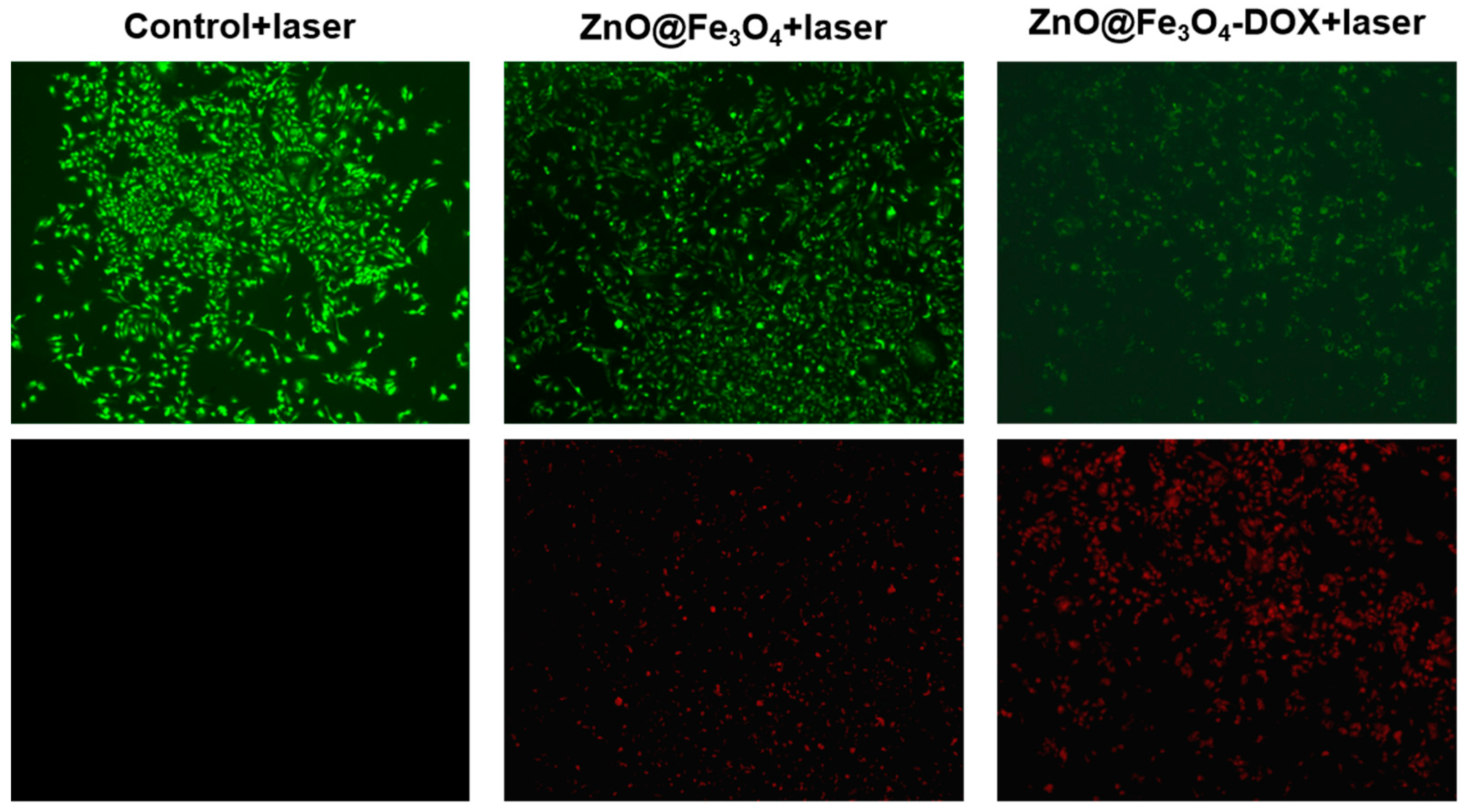

3.4. Cell Viability

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, S.; Zhao, R.; Shen, Y.; Lyu, B. Revolutionizing drug delivery: The power of stimulus-responsive nanoscale systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 154265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, L.F.; Ferreira, A.H.; Thipe, V.C. The state of the art of theranostic nanomaterials for lung, breast, and prostate cancers. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Devi, S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Yashavarddhan, M.; Bohra, D.; Ganguly, N. Exosomes as nature’s nano carriers: Promising drug delivery tools and targeted therapy for glioma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 182, 117754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Salazar, C.J.J.; Nurunnabi, M. Recent advances in bionanomaterials for liver cancer diagnosis and treatment. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 4821–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoneef, M.; Awad, M.; Aldosari, H.; Hendi, A.; Alshammari, S.; Aldehish, H.; Merghani, N.; Alsahli, A.; Almutairi, B.; Alharbi, R.; et al. Eco-friendly synthesis of magnetic ZnO/Fe3O4 nanocomposites: Structural, morphological, antimicrobial, and anticancer evaluation. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Dev. 2025, 10, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, A.; Jan, A.; Abbas, M.; Geetha, M.; Sadasivuni, K. Nanoparticles in cancer theragnostic and drug delivery: A comprehensive review. Life Sci. 2024, 352, 122899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.I.P.; Borges, J.P. Recent advances in magnetic electrospun nanofibers for cancer theranostics application. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2021, 31, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, D.; Ugolini, S.; Busti, F.; Marchi, G.; Castagna, A. Modern iron replacement therapy: Clinical and pathophysiological insights. Int. J. Hematol. 2018, 107, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, Z.; Chandrasekharan, P.; Chiu-Lam, A.; Hensley, D.; Dhavalikar, R.; Zhou, X.; Yu, E.; Goodwill, P.; Zheng, B.; Rinaldi, C.; et al. Magnetic particle imaging-guided heating in vivo using gradient fields for arbitrary localization of magnetic hyperthermia therapy. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 3699–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushwaha, P.; Chauhan, P. Facile synthesis of water-soluble Fe3O4 and Fe3O4@PVA nanoparticles for dual-contrast T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2023, 95, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Hung, C.; Lo, Y.; Li, C.; Ravula, V.; Wang, L. A biotin-selective molecular imprinted polymer containing Fe3O4 nanoparticles and CD44-selective aptamer for targeting cancer hyperthermia therapy. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Tec. 2025, 109, 106972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashaei-Asl, R.; Motaali, S.; Ebrahimie, E.; Mohammadi-Dehcheshmeh, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Pashaiasl, M. Delivery of doxorubicin by Fe3O4 nanoparticles, reduces multidrug resistance gene expression in ovarian cancer cells. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2024, 263, 155667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, Y.P.; Shameli, K.; Miyake, M.; Khairudin, N.B.B.A.; Mohamad, S.E.B.; Naiki, T.; Lee, K.X. Green biosynthesis of superparamagnetic magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles and biomedical applications in targeted anticancer drug delivery system: A review. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 2287–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B.; Nema, A.; Shetake, N.; Gupta, J.; Barick, K.; Lawande, M.; Pandey, B.; Priyadarsini, I.; Hassan, P. Glutamic acid-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles for tumor-targeted imaging and therapeutics. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 112, 110915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Prakash, A.; Jaiswal, M.; Agarrwal, A.; Bahadur, D. Superparamagnetic iron oxide-reduced graphene oxide nanohybrid-a vehicle for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia treatment of cancer. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 448, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Luong, H.; Pham, D.; Cao, L.; Nguyen, T.; Le, T. Drug-loaded Fe3O4/lignin nanoparticles to treat bacterial infections. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 289, 138868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Huang, J.; Zhao, W.; Guo, R.; Cui, S.; Li, Y.; Kadasala, N.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q. A multifunctional nanoplatform based on Fe3O4@Au NCs with magnetic targeting ability for single NIR light-triggered PTT/PDT synergistic therapy of cancer. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 944, 169206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, L.; Liu, F.; Qi, X.; Ge, Y.; Shen, S. Azo-functionalized Fe3O4 nanoparticles: A Near-infrared light triggered drug delivery system for combined therapy of cancer with low toxicity. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 3660–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.; Pham, Q.; Riviere, E.; Thanh, P.; Nam, P.; Hai, P.; Anh, N.; Phuc, L.; Hong, N. Optimizing fabrication parameters of Fe3O4 nanoparticles for enhancing magnetic hyperthermia efficiency. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 343, 130983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.M.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Kong, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Du, Y.P.; Jin, Y.; et al. Appropriate size of magnetic nanoparticles for various bioapplications in cancer diagnostics and therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 3092–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, L.; Cao, J.; Wang, K.; Ge, Y.; Ma, W.; Qi, X.; Shen, S. Effect of magnetic nanoparticles size on rheumatoid arthritis targeting and photothermal therapy. Colloid Surf. B 2018, 170, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Ahmad, M.; Shadab, G.; Siddique, H. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles based cancer theranostics: A double edge sword to fight against cancer. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 45, 117–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasthuri, K.; Kumar, J.; Rajkumar, P.; Ranchani, A.; Kaliyamurthy, J. Bio-inspired synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using Taraxacum officinale for antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 170, 113409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, L.; Qian, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Recent advances on nanomaterials for antibacterial treatment of oral diseases. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 20, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, E.; Stoian, G.; Cojocaru, B.; Parvulescu, V.; Coman, S. ZnO/CQDs nanocomposites for visible light photodegradation of organic pollutants. Catalysts 2022, 12, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Huang, Y.; Gurunathan, S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce apoptosis and autophagy in human ovarian cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 6521–6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Li, C.; Wu, K.; Hu, C.; Yang, N. Detection of tumor marker using ZnO@reduced graphene oxide decorated with alkaline phosphatase-labeled magnetic beads. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 7747–7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Tang, D.; Meng, L.; Cui, B. ZnO capped flower-like porous carbon-Fe3O4 composite as carrier for bi-triggered drug delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 107, 110256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astuti; Arief, S.; Muldarisnur, M.; Zulhadjri; Usna, S. Enhancement in photoluminescence performance of carbon-based Fe3O4@ZnO-C nanocomposites. Vacuum 2023, 211, 111935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, D.; Zheltova, V.; Meshina, K.; Vorontsov-Velyaminov, P.; Emelianova, M.; Bobrysheva, N.; Osmolowsky, M.; Voznesenskiy, M.; Osmolovskaya, O. Fe3O4@ZnO Core-shell nanoparticles–a novel facile fabricated magnetically separable photocatalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 672, 160873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Huang, W.; Ding, X.; He, J.; Huang, Q.; Tan, J.; Cheng, H.; Feng, J.; Li, L. Preparation and photocatalytic activity of Fe3O4@SiO2@ZnO:La. J. Rare Earth 2020, 38, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Tian, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, M. A dual-targeting Fe3O4@C/ZnO-DOX-FA nanoplatform with pH-responsive drug release and synergetic chemo-photothermal antitumor in vitro and in vivo. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 118, 111455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, S.; Jung, Y.; Lee, T.; Park, I.; Ahn, J. Fabrication of Fe3O4-ZnO core-shell nanoparticles by rotational atomic layer deposition and their multi-functional properties. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2016, 16, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Hu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, N.; Liang, C. Tunable zinc corrosion rate by laser surface modification for implants with controllable degradation direction. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 18263–18277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.Y.; Song, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.G.; Guo, Y.; Deng, M.; Gao, W.; Zhang, J. Facile Approach to Prepare rGO@Fe3O4 Microspheres for the Magnetically Targeted and NIR-responsive Chemo-photothermal Combination Therapy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchakeaw, A.; Nonthing, S.; Dulyasucharit, R.; Nanan, S. Improved photocatalytic activity of magnetically separable Fe3O4/ZnO photocatalyst for complete sunlight-active removal of tetracycline antibiotic. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2025, 862, 141868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Wu, L.; Chen, Y.; Qi, X.; Cao, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, W.; Ge, Y.; Shen, S. Ultra-small Fe3O4 nanoparticles for nuclei targeting drug delivery and photothermal therapy. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Tec. 2020, 58, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, A.; Abdouss, M.; Kalaee, M.; Homami, S.; Pourmadadi, M. Targeted delivery of quercetin using gelatin/starch/Fe3O4 nanocarrier to suppress the growth of liver cancer HepG2 cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Hassan, P.A.; Barick, K.C. Core-shell Fe3O4@ZnO nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia and bio-imaging applications. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 025207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, S.; Abdulnabi, W.; Abdul kader, H. Synthesis, characterization and environmental remediation applications of polyoxometalates-based magnetic zinc oxide nanocomposites (Fe3O4@ZnO/PMOs). Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2020, 13, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, V.M.; Huong, N.T.; Nam, D.T.; Dung, N.D.T.; Thu, L.V.; Nguyen-Le, M. Synthesis of Ternary Fe3O4/ZnO/Chitosan Magnetic Nanoparticles via an Ultrasound-Assisted Coprecipitation Process for Antibacterial Applications. J. Nanomater. 2020, 2020, 8875471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atla, S.B.; Lin, W.; Chien, T.; Tseng, M.; Shu, J.; Chen, C.; Chen, C. Fabrication of Fe3O4/ZnO magnetite core shell and its application in photocatalysis using sunlight. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 216, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Patel, N.; Ding, S.; Xiong, J.; Wu, P. Theranostics for hepatocellular carcinoma with Fe3O4@ZnO nanocomposites. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 4, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Cui, B.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Chang, Z.; Wang, Y. A multifunctional β-CD-modified Fe3O4@ZnO:Er3+,Yb3+ nanocarrier for antitumor drug delivery and microwave-triggered drug release. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 46, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Si, T. Fabrication of Spindle-like ZnO@Fe3O4 Nanocarriers for Targeted Drug Delivery and Controlled Release. Magnetochemistry 2026, 12, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010002

Guo Y, Yang M, Wang Y, Tian Z, Si T. Fabrication of Spindle-like ZnO@Fe3O4 Nanocarriers for Targeted Drug Delivery and Controlled Release. Magnetochemistry. 2026; 12(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Yongfei, Mao Yang, Yan Wang, Zhigang Tian, and Tongguo Si. 2026. "Fabrication of Spindle-like ZnO@Fe3O4 Nanocarriers for Targeted Drug Delivery and Controlled Release" Magnetochemistry 12, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010002

APA StyleGuo, Y., Yang, M., Wang, Y., Tian, Z., & Si, T. (2026). Fabrication of Spindle-like ZnO@Fe3O4 Nanocarriers for Targeted Drug Delivery and Controlled Release. Magnetochemistry, 12(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010002