The Effect of Incentives on Facilitating User Engagement with Succulent Retailers’ Social Media Pages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Definition of User Engagement

2.2. The Measurement of User Engagement

2.3. The Incentives That Motivate Individuals’ Behaviors

2.3.1. Economic Incentive

2.3.2. Social Incentive

2.3.3. Useful Information

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. The Construction of the Taxonomy of the Incentive Messages Posted by the Succulent Retailers

3.3. Analyzing the Effect of Incentives on Triggering User Engagement

4. Results

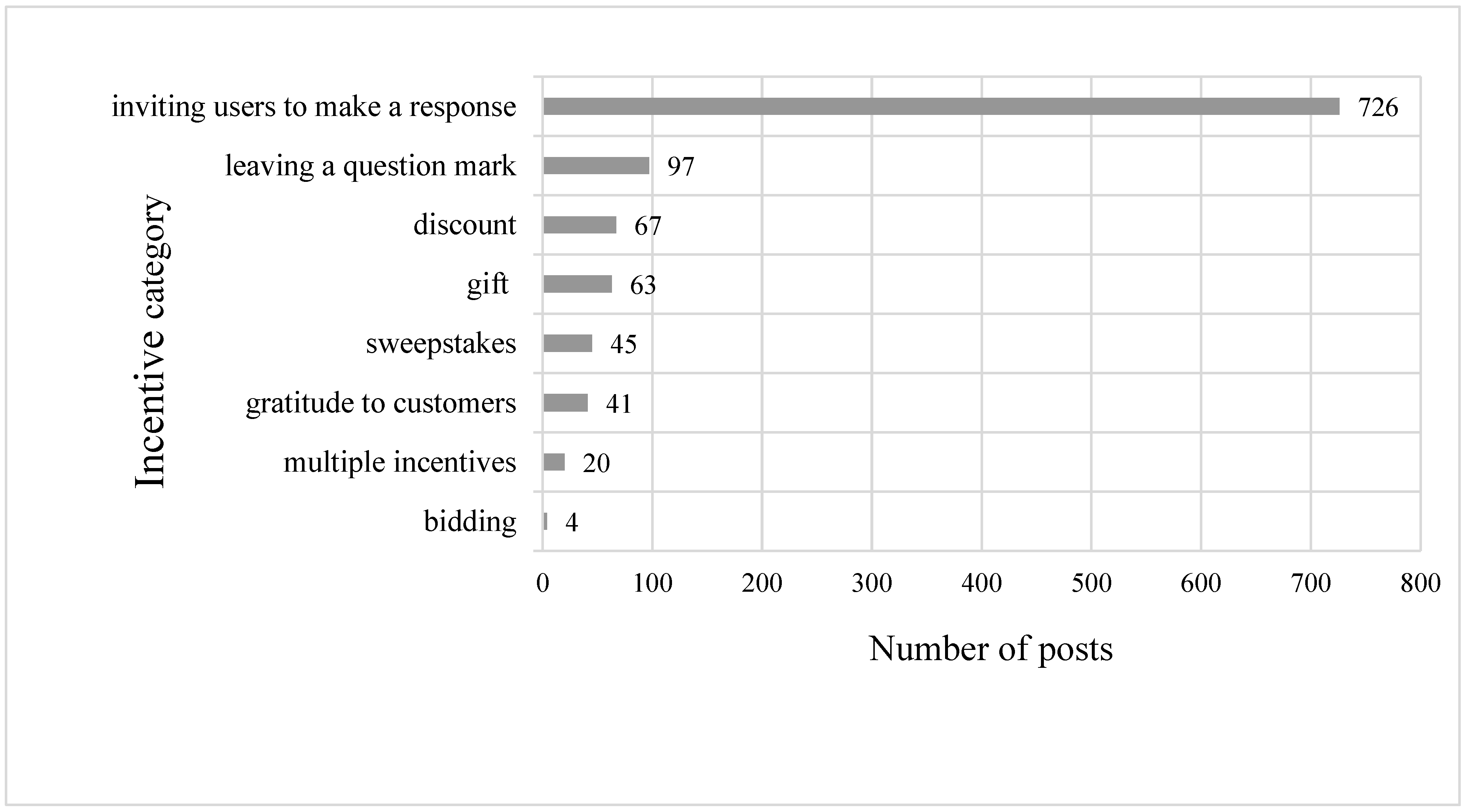

4.1. The Incentives Used by Succulent Retailers to Motivate User Engagement

4.1.1. Economic Incentives

- (1)

- Discounts: Incentives in this subcategory were mainly the discounts conveying monetary value to users under the name of special offers, early bird, clearance, free shipping, etc. [70]. Succulent retailers initiated this type of incentive, mostly for special occasions, such as the holidays of Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day, and Christmas, to inform users of the good time for purchasing succulent plants or related gifts.

- (2)

- Gifts: Incentives in this category mainly refer to material rewards in the form of free gifts. Usually, the gifts are the retailers’ products, such as potted plants, or items that were not produced for regular sales, such as postcards of special editions. Meanwhile, incentives in this category were usually initiated for specific occasions.

- (3)

- Sweepstakes: Incentives of this category refer to the lottery offered by succulent retailers to motivate user engagement. They can be monetary or non-monetary items; meanwhile, incentives in this category differ from those of discounts and gifts in the process of gaining the rewards that users need to spend more effort to participate in the campaign for gaining the rewards.

- (4)

- Bidding: Incentives in this subcategory were mainly an auction or bidding campaign held by succulent retailers to promote their products or brands. Messages regarding the product, timing, and starting price for the bidding were usually posted. Even though these incentives seem attractive to users since the posts carrying this kind of message gained more “likes” from users, an average of 130.5 likes per post, this type of post accounted for only 0.38% of the overall incentive posts.

4.1.2. Social Incentive

- (1)

- Gratitude to customers: Incentives in this category were mainly the succulent retailers’ thanks or congratulations to certain users for their purchases. By doing so, those users’ names or their enterprises were usually seen on the posts, which provided users the benefit of seeing their names or enterprises on the FB pages owned by the succulent retailers. The exposure of those users’ names or their companies’ brands can be increased as a result of succulent retailers’ actions. It is of value for the users, so it is considered a kind of incentive for facilitating users’ engagement behaviors. Those incentives usually happened in circumstances where users had bought succulent plants as a gift, and the succulent retailers posted their thanks and/or congratulations to either the giver or receiver. Even though Huang and Chen [69] found that these posts frequently appeared on florists’ FB pages, this kind of incentive seemed less likely to happen for succulent retailers. Posts carrying this type of incentive message accounted for 3.86% of the overall incentive posts.

- (2)

- Leaving a question mark (“?”): Previous studies in other industry domains have found that posts with question marks usually arouse user responses toward the posts [67,68,71]. It implies that leaving a question mark “?” can be used as an instrument to encourage user interactions with succulent retailers’ FB pages. The succulent retailers can interact with the users by leaving a question mark on their FB posts. Posts with this kind of message frame could lead users to think that the succulent retailers cared about their users and liked to know their users’ opinions or thoughts. The post associated with the question mark “?” mainly shared the experience and gardening knowledge of succulent plants with the users and then asked for users’ opinions, thoughts, or preferences on those posted issues.

- (3)

- Inviting users to make responses: Incentives of this kind refer to succulent retailers’ invitations for users to leave a comment, share posts, or express their feelings about what is posted by succulent retailers. Previous studies have found that this kind of invitation can arouse users to respond to the post [68,71], so it can be seen as a motivator for arousing users’ engagement behaviors. Among the nine incentive subcategories explored in this study, posts carrying this type of incentive were the most common on succulent retailers’ FB pages, sharing the greatest portion (68.30%) of the total posts initiated by the succulent retailers.

4.1.3. Multiple Incentives

4.2. The Effect of Incentives on Triggering User Engagement

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beentje, H.J. The Kew Plant Glossary: An Illustrated Dictionary of Plant Terms 2010; Royal Botanic Gardens: Richmond, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sayuti, A.; Ahmed-Kristensen, S. Understanding emotional responses and perception within new creative practices of biological materials. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Design Creativity, Oulu, Finland, 26–28 August 2020; pp. 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Census of Horticultural Specialties. 2022. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Surveys/Guide_to_NASS_Surveys/Census_of_Horticultural_Specialties/index.php (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Taiwan Today. Goods for the Mind. 2014. Available online: https://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?unit=8&post=14195 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Knuth, M.J.; Behe, B.K.; Huddleston, P.T.; Hall, C.R.; Fernandez, R.T.; Khachatryan, H. Water Conserving Message Influences Purchasing Decision of Consumers. Water 2020, 12, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Z.; Ahmad, N.; Bakar, A.R.A. Reflections of entrepreneurs of small and medium-sized enterprises concerning the adoption of social media and its impact on performance outcomes: Evidence from the UAE. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainin, S.; Parveen, F.; Moghavvemi, S.; Jaafar, N.I.; Shuib, N.L.M. Factors influencing the use of social media by SMEs and its performance outcomes. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 570–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, M.; Kinelski, G.; Stefańska, M.; Grzesiak, M.; Budka, B. Social media engagement in shaping green energy business models. Energies 2022, 15, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Tinervia, S.; Tulone, A.; Crescimanno, M. Drivers affecting the adoption and effectiveness of social media investments: The Italian wine industry case. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimonis, G.; Dimitriadis, S. Brand strategies in social media. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Habibi, M.R.; Richard, M.O.; Sankaranarayanan, R. The effects of social media based brand communities on brand community markers, value creation practices, brand trust and brand loyalty. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1755–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Cao, Y.M.; Park, C. The relationships among community experience, community commitment, brand attitude, and purchase intention in social media. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Rahman, M.; Voola, R.; De Vries, N. Customer engagement behaviours in social media: Capturing innovation opportunities. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yang, S.; Ma, M.; Huang, J. Value co-creation on social media: Examining the relationship between brand engagement and display advertising effectiveness for Chinese hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2153–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; den Ambtman, A.; Bloemer, J.; Horváth, C.; Ramaseshan, B.; van de Klundert, J.; Kandampully, J. Managing brands and customer engagement in online brand communities. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattberg, R.C.; Neslin, S.A. Sales promotion: The long and the short of it. Mark. Lett. 1989, 1, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.C.; Jackaria, N. The efficacy of sales promotions in UK supermarkets: A consumer view. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 30, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg, P.A. Employee incentive programs: Recipient behaviors in points, cash, and gift card programs. Perform. Improv. Q. 2017, 29, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.J.; Luthans, F. The impact of financial and nonfinancial incentives on business-unit outcomes over time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, C.M.; Susanti, I.W. How do budget level and type of incentives influence performance? J. Ilm. Akunt. Dan Bisnis 2019, 14, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. Differential effects of incentive motivators on work performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Social Media—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/1164/social-networks/#topicOverview (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Gómez, M.; Lopez, C.; Molina, A. An integrated model of social media brand engagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Roderick, J.B. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luarn, P.; Lin, Y.F.; Chiu, Y.P. Influence of Facebook brand-page posts on online engagement. Online Inf. Rev. 2015, 39, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabate, F.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; Cañabate, A.; Lebherz, P.R. Factors influencing popularity of branded content in Facebook fan pages. Eur. Mgt. J. 2014, 32, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.D. Proposing to your fans: Which brand post characteristics drive consumer engagement activities on social media brand pages? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2017, 26, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W. Content strategies and audience response on Facebook brand pages. Mktg. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 927–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, S.; Jenkins, S. Why Facebook Reactions are good news for evaluating social media campaigns. J. Direct Data Digit. Mark. Pract. 2016, 17, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, I.; Paltsoglou, S.; Patoulidis, V. Post popularity and reactions in retail brand pages on Facebook. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2019, 47, 957–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreda, A.A.; Bilgihan, A.; Nusair, K.; Okumus, F. Generating brand awareness in online social networks. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Olfman, L.; Ko, I.; Koh, J.; Kim, K. The influence of on-line brand community characteristics on community commitment and brand loyalty. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2008, 12, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S. Applying uses and gratifications theory to understand customer participation in social media brand communities: Perspective of media technology. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, A.Y.K.; Banerjee, S. How businesses draw attention on Facebook through incentives, vividness and interactivity. Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2015, 42, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Chen, Y.; Parkes, D.C. Designing incentives for online question-and-answer forums. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce, Stanford, CA, USA, 6–10 July 2009; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Gharibi, R.; Malekzadeh, M. Gamified Incentives: A Badge Recommendation Model to Improve User Engagement in Social Networking Websites. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rafaeli, S.; Raban, D.R.; Ravid, G. Social and economic incentives in Google Answers. In Proceedings of the ACM Workshop Sustaining Community: The Role and Design of Incentive Mechanisms in Online Systems 2005, Sanibel Island, FL, USA, 6–8 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rafaeli, S.; Raban, D.R.; Ravid, G. How social motivation enhances economic activity and incentives in the Google Answers knowledge sharing market. Int. J. Knowl. Learn. 2007, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nov, O. What motivates wikipedians? Commun. ACM 2007, 50, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of personality. In Handbook of Personality, 2nd ed.; Pervin, L., John, O., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefeld, I.; Iseke, A.; Krebs, A. Explicit incentives in online communities: Boon or bane? Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 17, 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condly, S.J.; Clark, R.E.; Stolovitch, H.D. The effects of incentives on workplace performance: A meta-analytic review of research studies 1. Perform. Improv. Q. 2003, 16, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gieter, S.; Hofmans, J. How reward satisfaction affects employees’ turnover intentions and performance: An individual differences approach. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2015, 25, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, S.A.; Adomdza, G.K. Incentive salience and improved performance. Hum. Perform. 2011, 24, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, S.A.; Shaffer, V. The motivational properties of tangible incentives. Compens. Benefits Rev. 2007, 39, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presslee, A.; Vance, T.W.; Webb, R.A. The effects of reward type on employee goal setting, goal commitment, and performance. Account. Rev. 2013, 88, 1805–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehnen, L.M.; Bartsch, S.; Kull, M.; Meyer, A. Exploring the impact of rewarded social media engagement in loyalty programs. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.S.; Suh, K.S.; Lee, M.B. Exploring the factors enhancing member participation in virtual communities. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2002, 10, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, L.; Bansal, R.; Pruthi, N.; Khaskheli, M.B. Impact of Social Media Influencers on Customer Engagement and Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.F. A study on service quality of virtual community websites. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2003, 14, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Chen, Y.; Chow, W.S. Key values driving continued interaction on brand pages in social media: An examination across genders. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.L. Survey of Flower Purchase Frequency of Taiwan. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Yue, C.; Meyer, M.H.; Hall, C.R. Factors affecting US consumer expenditures of fresh flowers and potted plants. HortTechnology 2016, 26, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanpage Karma. Terms of Service. Available online: https://www.fanpagekarma.com/terms (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Fanpage Karma. Great Features for Great Users. Available online: https://www.fanpagekarma.com/features (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Downe-Wamboldt, B. Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Intl. 1992, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, B.F.; Miller, W.L. (Eds.) A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In Doing Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.Y.; Lee, E.H. Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassarjian, H.H. Content analysis in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1977, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffler, R.E. Maximum Z scores and outliers. Am. Stat. 1988, 42, 79–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hand, D.J.; Taylor, C.C. Multivariate Analysis of Variance and Repeated Measures: A Practical Approach for Behavioural Scientists; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Annamalai, B.; De, S.K. Evaluating marketer generated content popularity on brand fan pages—A multilevel modelling approach. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 44, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Conduit, J.; Frethey-Bentham, C.; Fahy, J.; Goodman, S. Social media engagement behavior: A framework for engaging customers through social media content. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2213–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.C.; Chen, L.C. Message strategies and media formats of florists’ Facebook posts and their effects on users’ engagement behaviors. HortScience 2018, 53, 1647–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandon, P.; Wansink, B.; Laurent, G. A benefit congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Spiller, L.; Hettche, M. Analyzing media types and content orientations in Facebook for global brands. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacre, M.; Leys, C.; Mora, Y.L.; Lakens, D. Taking parametric assumptions seriously: Arguments for the use of Welch’s F-test instead of the classical F-test in one-way ANOVA. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.L. On choosing a test statistic in multivariate analysis of variance. Psychol. Bull. 1976, 83, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.L. On the comparison of several mean values: An alternative approach. Biometrika 1951, 38, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Games, P.A.; Howell, J.F. Pairwise multiple comparison procedures with unequal n’s and/or variances: A Monte Carlo study. J. Educ. Stat. 1976, 1, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Tafesse, W.; Wien, A. Using message strategy to drive consumer behavioral engagement on social media. J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentina, I.; Guilloux, V.; Micu, A.C. Exploring social media engagement behaviors in the context of luxury brands. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.R. Courting the Consumer: Consumer Preferences and Engagement with Social-Media Marketing and Horticultural Businesses. Master’s Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| ID of the Succulent Retailers | Locations | Date the Store Founded | Date the Brand Page Initiated | Size of Fan Base | Amount of Total Posts | Amount of Incentive Posts (%) z | Website of the Brand Pages y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Taipei | 31 July 2015 | 27 June 2015 | 59,523 | 703 | 176 | (25.04) | https://www.facebook.com/succuland.com.tw |

| 2 | Online | - | 21 December 2012 | 25,834 | 3 | 0 | (---) | https://www.facebook.com/R.Lin888/ |

| 3 | Kaohsiung | September 2015 | 22 December 2015 | 24,122 | 524 | 491 | (93.7) | https://www.facebook.com/mcsucculents |

| 4 | Taichung | 20 May 2015 | 27 March 2015 | 18,435 | 43 | 3 | (6.98) | https://www.facebook.com/saturdays.succulents |

| 5 | Taichung | 19 July 1982 | 21 November 2014 | 17,247 | 42 | 17 | (40.48) | https://www.facebook.com/smilesucculent |

| 6 | Hsinchu | 26 January 2014 | 26 January 2014 | 15,983 | 116 | 17 | (14.66) | https://www.facebook.com/littleredsucculent |

| 7 | Online | - | 4 July 2016 | 11,832 | 43 | 36 | (83.72) | https://www.facebook.com/ohcarmo |

| 8 | Taipei | 8 February 2014 | 8 February 2014 | 7204 | 146 | 49 | (33.56) | https://www.facebook.com/livingjardin |

| 9 | Tainan | - | 7 February 2017 | 5011 | 66 | 4 | (6.06) | https://www.facebook.com/1265441943493208 |

| 10 | Tainan | 1 October 2014 | 29 May 2012 | 4323 | 209 | 24 | (11.48) | https://www.facebook.com/loveiplant |

| 11 | Online | - | 17 June 2014 | 3654 | 4 | 0 | (---) | https://www.facebook.com/succulentsshop |

| 12 | Changhua | - | 24 March 2014 | 2745 | 241 | 177 | (73.44) | https://www.facebook.com/colorfulsucculents |

| 13 | Online | 23 January 2013 | 23 December 2013 | 2162 | 29 | 4 | (13.79) | https://www.facebook.com/succulentsc |

| 14 | Taoyuan | 15 September 2016 | 29 September 2016 | 1699 | 142 | 20 | (14.08) | https://www.facebook.com/magicsucculentshouse |

| 15 | Changhua | - | 28 April 2015 | 1380 | 5 | 0 | (---) | https://www.facebook.com/kittenplants/ |

| 16 | Taichung | - | 20 March 2017 | 1197 | 12 | 5 | (41.67) | https://www.facebook.com/390589311319283 |

| 17 | Online | - | 1 April 2015 | 968 | 41 | 14 | (34.15) | https://www.facebook.com/mhleesucculent |

| 18 | Taipei | - | 6 December 2015 | 933 | 43 | 19 | (44.19) | https://www.facebook.com/succulentsgo |

| 19 | Online | - | 5 August 2018 | 694 | 143 | 5 | (3.5) | https://www.facebook.com/yuyusucculents |

| 20 | Yunlin | - | 5 April 2019 | 171 | 4 | 0 | (---) | https://www.facebook.com/662752180811630 |

| 21 | Online | - | 26 August 2017 | 118 | 43 | 2 | (4.65) | https://www.facebook.com/709485199246339 |

| Incentive Category | Definition | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic incentives | Discounts | The incentives with monetary value, including special offers, coupons, free shipping, etc. |

|

| Gifts | The non-monetary objects giving for free or with partial payment for motivating the users. |

| |

| Sweepstakes | The lottery promotion program is used to motivate users to participate in certain commercial activities. |

| |

| Bidding | The bidding program was initiated by succulent retailers for motivating users to engage in purchases. |

| |

| Social incentives | Gratitude to customers | Posts are initiated specifically to reveal shops’ feedback with gratitude or congratulations to their customers. |

|

| Leaving a question mark | The punctuation of the question marks associated with a request initiated by the succulent retailers for motivating the users to respond to that request. |

| |

| Inviting to make responses | The statements posted for inviting users to interact with the posts initiated by the succulent retailers by clicking on “like”, “comment” or “share” associated with the posts. |

| |

| Other incentives | Multiple incentives | The incentives containing two or more types of incentives are classified in this study. |

|

| Post Category | Sample Size | Percentage (%) | Mean | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Like | Comment | Share | Love | Haha | Wow | Sad | Angry | |||

| Inviting to make a response | 709 | 69.92 | 33.85 | 18.77 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 |

| Leaving a question mark | 87 | 8.58 | 74.40 | 2.92 | 1.07 | 2.20 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0 | 0 |

| Discounts | 64 | 6.31 | 52.34 | 5.17 | 0.84 | 1.09 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0 | 0 |

| Gifts | 58 | 5.72 | 59.59 | 1.60 | 1.74 | 1.41 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 |

| Gratitude to customers | 40 | 3.94 | 69.23 | 1.10 | 0.88 | 1.83 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0 | 0 |

| Sweepstakes | 35 | 3.45 | 81.14 | 17.83 | 7.14 | 1.94 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0 |

| Multiple incentives | 18 | 1.78 | 73.06 | 2.11 | 3.28 | 0.67 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0 |

| Bidding | 3 | 0.30 | 95.00 | 5.33 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 |

| MANOVA | Univariate Analyses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillai’s Trace | F (df1, df2) | p | Dependent Variables | Welch’s F (df1, df2) | p | Post Hoc Test |

| 0.26 | 18.80 (15, 2961) | 0.000 | Likes | 14.33 (5, 124.93) | 0.000 | sweepstakes > inviting to make a response leaving a question mark > inviting to make a response gifts > inviting to make a response |

| Comments | 99.48 (5, 160.11) | 0.000 | inviting to make a response > discount inviting to make a response > leaving a question mark inviting to make a response > gifts inviting to make a response > gratitude to customers leaving a question mark > gratitude to customers | |||

| Shares | 3.93 (5, 134.08) | 0.002 | gifts > inviting to make a response | |||

| MANOVA | Univariate Analyses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillai’s Trace | F (df1, df2) | p | Dependent Variable | Welch’s F (df1, df2) | p | Post Hoc Test |

| 0.24 | 12.61 (20, 3948) | 0.000 | Love | 18.50 (5, 119.36) | 0.000 | sweepstakes > inviting to make a response leaving a question mark > inviting to make a response gifts > inviting to make a response discount > inviting to make a response gratitude to customers > inviting to make a response leaving a question mark > discounts |

| Haha | 1.92 (5, 124.31) | 0.095 | - | |||

| Wow | 2.86 (5, 125.72) | 0.018 | - | |||

| Sad | - | - | - | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, L.-C. The Effect of Incentives on Facilitating User Engagement with Succulent Retailers’ Social Media Pages. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9080849

Huang L-C. The Effect of Incentives on Facilitating User Engagement with Succulent Retailers’ Social Media Pages. Horticulturae. 2023; 9(8):849. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9080849

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Li-Chun. 2023. "The Effect of Incentives on Facilitating User Engagement with Succulent Retailers’ Social Media Pages" Horticulturae 9, no. 8: 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9080849

APA StyleHuang, L.-C. (2023). The Effect of Incentives on Facilitating User Engagement with Succulent Retailers’ Social Media Pages. Horticulturae, 9(8), 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9080849