The Global Metabolome Profiles of Four Varieties of Lonicera caerulea, Established via Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Extraction

2.4. Liquid Chromatography

2.5. Mass Spectrometry

3. Results and Discussion

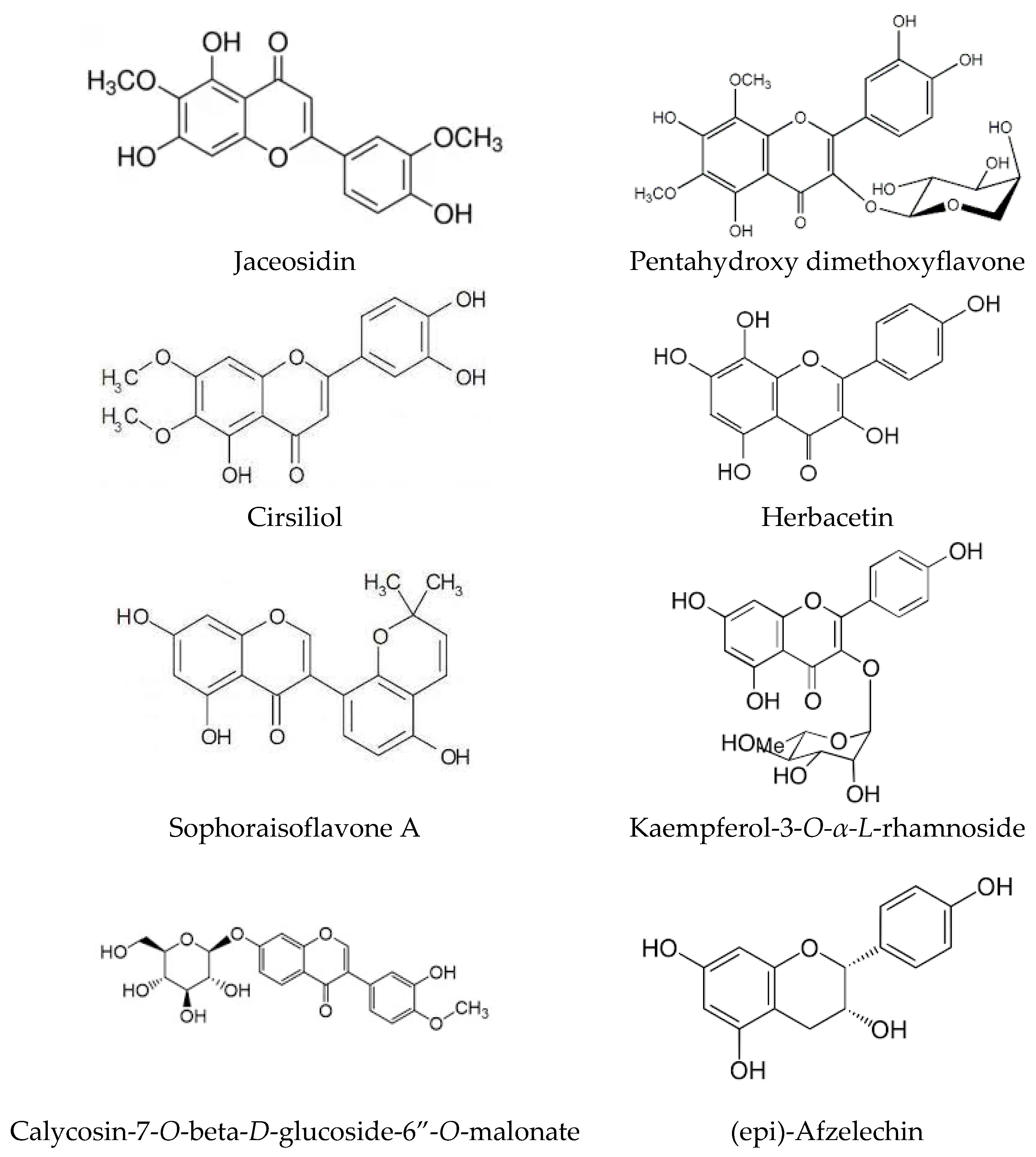

3.1. Flavones

3.1.1. 7-Hydroxy(iso)flavones

3.1.2. Dihydroxyflavones

3.1.3. Trihydroxyflavones

3.1.4. Tetrahydroxyflavones

3.1.5. Pentahydroxyflavones

3.2. Phenolic Acids

3.2.1. Hydroxycinnamic Acids and Cinnamate Esters

3.2.2. Hydroxybenzoic and Methylbenzoic Acids

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Class of Compounds | Identification | Amfora Far East | Amfora SPb | Tomichka Far East | Tomichka SPb | Goluboe Far East | Goluboe SPb | Volhova Far East | Volnova SPb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavone | Apigenin | ||||||||

| Flavone | Trihydroxy(iso)flavone | ||||||||

| Flavone | 5,6,4′-Trihydroxy-7,8-dimethoxyflavone | ||||||||

| Flavone | Jaceosidin | ||||||||

| Flavone | Cirsiliol | ||||||||

| Flavone | Sophoraisoflavone A | ||||||||

| Flavone | Pentahydroxy dimethoxyflavone | ||||||||

| Flavone | Dihydroxy-tetramethoxy(iso)flavone | ||||||||

| Flavone | Luteolin 7-O-glucoside | ||||||||

| Flavone | Chrysoeriol O-hexoside | ||||||||

| Flavone | Formononetin-7-O-glucoside-6″-O-malonate | ||||||||

| Flavone | Acacetin 8-C-glucoside malonylated | ||||||||

| Flavone | Calycosin-7-O-beta-D-glucoside-6″-O-malonate | ||||||||

| Flavone | Chrysin derivative | ||||||||

| Flavone | C-hexosyl-apigenin O-rhamnoside | ||||||||

| Flavone | Lonicerin | ||||||||

| Flavone | Luteolin 7-O-(6-O-arabinosyl-glucoside) | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Kaempferol | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Dihydrokaempferol | ||||||||

| Flavone | Rhamnocitrin | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Quercetin | ||||||||

| Flavone | Herbacetin | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Rhamnetin II | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Isorhamnetin | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Kaempferol-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Quercetin 3-O-glucoside | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Quercetin 3-O-pentosyl hexoside | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Rutin | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Isorhamnetin 3-O-(6″-O-rhamnosyl-hexoside) | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Dimethylquercetin-3-O-dehexoside | ||||||||

| Flavonol | Derivative of Quercetin rhamnosyl hexoside | ||||||||

| Flavan-3-ol | Epiafzelechin | ||||||||

| Flavan-3-ol | (Epi)-catechin | ||||||||

| Flavan-3-ol | Gallocatechin | ||||||||

| Flavan-3-ol | (Epi)-afzelechin derivative | ||||||||

| Flavan-3-ol | (Epi)-catechin derivative | ||||||||

| Flavan-3-ol | (−)-Epicatechin Gallate | ||||||||

| Flavanone | Naringenin | ||||||||

| Flavanone | Butin | ||||||||

| Anthocyanin | Anthocyanidin | ||||||||

| Anthocyanin | Petunidin | ||||||||

| Anthocyanin | Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside | ||||||||

| Anthocyanin | Delphinidin 3-O-glucoside | ||||||||

| Anthocyanin | Pelargonidin 3-O-(6-O-malonyl-β-D-glucoside) | ||||||||

| Anthocyanin | Delphinidin 3-O-β-D-sambubioside | ||||||||

| Anthocyanin | Delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside | ||||||||

| Anthocyanin | Petunidin-3-rutinoside | ||||||||

| Hydroxybenzoic acid (Phenolic acid) | Protocatechuic acid | ||||||||

| Hydroxycinnamic acid | Caffeic acid | ||||||||

| Methylbenzoic acid | Methylgallic acid | ||||||||

| Trans-cinnamic acid | Ferulic acid | ||||||||

| Phenolic acid | Hydroxy methoxy dimethylbenzoic acid | ||||||||

| Phenolic acid | 2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxybenzoic acid | ||||||||

| Hydroxycinnamic acid | Hydroxyferulic acid | ||||||||

| Hydroxycinnamic acid | Sinapic acid | ||||||||

| Phenolic acid | 2,4,6-Trihydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid | ||||||||

| Hydroxybenzoic acid (Phenolic acid) | Ellagic acid | ||||||||

| Phenolic acid | 6-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | ||||||||

| Hydroxycinnamic acid | Chlorogenic acid | ||||||||

| Hydroxycinnamic acid | 3-O-Hydroxydihydrocaffeoylquinic acid | ||||||||

| Phenolic acid | Caffeoylquinic acid derivative | ||||||||

| Flavonoid | p-Coumaroylhexose-4-O-hexoside | ||||||||

| Phenolic acid | 3,4-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid | ||||||||

| Phenolic acid | 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid | ||||||||

| Phenolic acid | p-Coumaroyl malonyldihexose | ||||||||

| Phenolic acid | Dicaffeoylferuoylquinic acid | ||||||||

| Stilbene | Pinosylvin | ||||||||

| Stilbene | Resveratrol | ||||||||

| Stilbene | Dihydroresveratrol | ||||||||

| Hydroxycoumarin | Umbelliferone | ||||||||

| Coumarin | Fraxetin | ||||||||

| Coumarin | 3,4/6,8-Dihydro-5,7-dihydroxy-2-oxo-2H-1-benzopyran-3-acetic acid | ||||||||

| Coumarin | Umbelliferone hexoside | ||||||||

| Coumarin | 7-(β-D-Glucopyranoside/galactopyranoside)-2-oxo-2H-1-benzopyran-4-acetic acid | ||||||||

| OTHERS | |||||||||

| Amino acid | L-Proline | ||||||||

| Non-proteinogenic L-alpha-amino acid | L-Pyroglutamic acid | ||||||||

| Amino acid | L-Histidine | ||||||||

| Amino acid | L-threanine | ||||||||

| Amino acid | L-Arginine | ||||||||

| Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | Shikimic acid | ||||||||

| Tricarboxylic acid | Citric acid | ||||||||

| Polyhydroxycarboxylic acid | Quinic acid | ||||||||

| Pentahydroxyhexanoic acid | Gluconic acid | ||||||||

| Benzofuran | Loliolide | ||||||||

| Alpha, omega dicarboxylic acid | Sebacic acid | ||||||||

| 4-Dihydroxy-3-methoxy-benzenepropanoic acid | |||||||||

| Sesquiterpenoid | Caryophyllene oxide | ||||||||

| Carboxylic acid | Myristoleic acid | ||||||||

| Pyrimidine nucleoside | Cytidine | ||||||||

| Glycosylated pyrimidine analog | Uridine | ||||||||

| Hydroxytetradecanoic acid | Hydroxy myristic acid | ||||||||

| Medium-chain fatty acid | Hydroxy dodecanoic acid | ||||||||

| Caffeic acid isoprenyl ester | |||||||||

| Sesquiterpene lactone | Artemisinin C | ||||||||

| Aporphine alkaloid | Anonaine | ||||||||

| Ribonucleoside composite of adenine (purine) | Adenosine | ||||||||

| 3,4,8,9,10-Penthahydroxydibenzo [b,d]pyran-6-one | |||||||||

| Omega-3-fatty acid | Stearidonic acid | ||||||||

| Omega-3-fatty acid | Linolenic acid | ||||||||

| Mixture of diastereomers | Fructose-leucine | ||||||||

| Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | Coumaroyl shiikimic acid | ||||||||

| Oxylipin | 13-Trihydroxy-Octadecenoic acid | ||||||||

| Alpha, omega-dicarboxylic acid | Eicosatetraenedioic acid | ||||||||

| Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | Caffeoyl shikimic acid | ||||||||

| Alpha, omega-dicarboxylic acid | Trihydroxy eicosatetraenoic acid | ||||||||

| Dicarboxylic acid sugar | Caffeoyl gluconic acid | ||||||||

| Iridoid glucoside | Sweroside | ||||||||

| Cyclopentapyran | Loganin acid | ||||||||

| 7-(β-D-Galactopyranosyloxy)-6,8-dimethoxy-2H-1-benzopyran-2-one | |||||||||

| Iridoid | Monotropein | ||||||||

| Sterol | Beta-Sitostenone | ||||||||

| Anabolic steroid | Vebonol | ||||||||

| Phenylpropanoid glucoside | Grayanoside A | ||||||||

| Thromboxane receptor antagonist | Vapiprost | ||||||||

| Indole sesquiterpene alkaloid | Sespendole | ||||||||

| Iridoid glucoside | p-Coumaroyl monotropein | ||||||||

| Iridoid glucoside | p-coumaroyl-6,7-dihydromonotropein | ||||||||

| Carotenoid | Zeaxanthin | ||||||||

| Carotenoid | (all-E)-lutein 3-O-C(4:0) | ||||||||

| Iridoid | p-Coumaroyl monotropein hexoside | ||||||||

| Product of chlorophyll degradation | Pheophytin A |

References

- Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Oszmiański, J.; Piórecki, N.; Fecka, I. Iridoids, Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Edible Honeysuckle Berries (Lonicera caerulea var. kamtschatica Sevast.). Molecules 2017, 22, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Gong, X.; Bo, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Zang, E.; Zhang, C.; Li, M. Iriodoids: Research advances in their phytochemistry, biological activities, and pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2020, 25, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S.; Oprea, O.C.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Roncea, F.N.; Prelipcean, A.-M.; Craciunescu, O.; Iosageanu, A.; Artem, V.; Ranca, A.; Motelica, L.; et al. Health Benefits of Antioxidant Bioactive Compounds in the Fruits and Leaves of Lonicera caerulea L. and Aronia melanocarpa (Michx.) Elliot. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Streltsina, S.A.; Plekhanova, M.N.; Tikhonova, O.A.; Sabitov, A.S.H.; Arsenyeva, T.V.; Pupkova, N.A. Comparative evaluation of wild-growing species of berry crops in terms of composition and content of biologically active phenolic compounds. Proc. Appl. Bot. Genet. Breed. 2007, 161, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Perova, I.B.; Rylina, E.V.; Eller, K.I.; Akimov, M.Y. The study of the polyphenolic complex and iridoid glycosides in various cultivars of edible honeysuckle fruits Lonicera edulis Turcz. ex Freyn. Vopr. Pitan. 2019, 88, 88–99. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, N.V.; Imamkulova, Z.A.; Kulikov, I.M.; Medvedev, S.M. Sources of economically valuable characteristics of collection samples of honeysuckle blue (Lonicera caerulea L.). Hortic. Vitic. 2018, 16–23. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołba, M.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Kucharska, A.Z. Health Properties and Composition of Honeysuckle Berry Lonicera caerulea L. An Update on Recent Studies. Molecules 2020, 25, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perova, I.B.; Eller, K.I.; Gerasimov, M.A.; Baturina, V.A.; Akimov, M.Y.; Akimova, O.M.; Mironov, A.M.; Koltsov, V.A. A study of a complex of bioactive compounds in the fruits of promising blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.) cultivars. Proc. Appl. Bot. Genet. Breed. 2023, 184, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, C.Y. The influence of light and maturity on fruit quality and flavonoid content of red raspberries. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senica, M.; Bavec, M.; Stampar, F.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. Blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea subsp. edulis (Turcz. ex Herder) Hultén.) berries and changes in their ingredients across different locations. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3333–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, E.W. The Atom and the Ocean, Understanding the Atom Series; ERIC: Washington, DC, USA, 1968. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED042651.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Hossain, M.K.; Dayem, A.A.; Han, J.; Yin, Y.; Kim, K.; Saha, S.K.; Yang, G.-M.; Choi, H.Y.; Cho, S.-G. Molecular Mechanisms of the Anti-Obesity and Anti-Diabetic Properties of Flavonoids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Luo, Q.; Sun, M.; Corke, H. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 2157–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharmacopoeia of the Eurasian Economic Union, Approved by Decision of the Board of Eurasian Economic Commission No. 100 Dated August 11, 2020. Available online: https://eec.eaeunion.org/upload/medialibrary/37c/PHARMACOPOEIA-of-the-Eurasian-Economic-Union.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- Azmir, J.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Sharif, K.; Mohamed, A.; Sahena, F.; Jahurul, M.; Ghafoor, K.; Norulaini, N.; Omar, A. Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghakhani, F.; Kharazin, N.; Gooini, Z.L. Flavonoid Constituents of Phlomis (Lamiaceae) Species Using Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry. Phytochem. Anal. 2018, 29, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, M.; Macia, A.; Romero, M.-P.; Motilva, M.-J. Improved liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the determination of phenolic compounds in virgin olive oil. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1214, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, M.M.; Hussein, S.R.; Elkhateeb, A.; El-shabrawy, M.; Abdel-Hameed, E.-S.S.; Kawashty, S.A. Comparative study of Mentha species growing wild in Egypt: LC-ESI-MS analysis and chemosystematic significance. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 8, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, R.; Muller, H.; Muller, A.; Karar, M.G.E.; Kuhnert, N. Identification and characterization of chlorogenic acids, chlorogenic acid glycosides and flavonoids from Lonicera henryi L. (Caprifoliaceae) leaves by LC–MSn. Phytochemistry 2014, 108, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmehdi, O.; Bouyahya, A.; József, J.E.K.Ő.; Cziáky, Z.; Zengin, G.; Sotkó, G.; Elbaaboua, A.; Senhaji, N.S.; Abrini, J. Synergistic interaction between propolis extract, essential oils, and antibiotics against Staphylococcus epidermidis and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Second Metab. 2021, 8, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.L.; Xu, J.J.; Zhong, K.R.; Shang, Z.P.; Wang, F.; Wang, R.F.; Liu, B. Analysis of non-volatile chemical constituents of Menthae Haplocalycis herba by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography—High resolution mass spectrometry. Molecules 2017, 22, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.R.; El-Hawary, S.S.; Ibrahim, R.M.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; El-Halawany, A.M. Identification of Chemopreventive Components from Halophytes Belonging to Aizoaceae and Cactaceae Through LC/MS–Bioassay Guided Approach. J. Chrom. Sci. 2021, 59, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Kumar, B. HPLC–QTOF–MS/MS-based rapid screening of phenolics and triterpenic acids in leaf extracts of Ocimum species and their interspecies variation. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. 2016, 39, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Huang, S.; Chen, Q.; Hu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zheng, P.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J. Chemical characterisation and quantification of the major constituents in the Chinese herbal formula Jian-Pi-Yi-Shen pill by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS and HPLC-QQQ-MS/MS. Phytochem. Anal. 2020, 31, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeywickrama, G.; Debnath, S.C.; Ambigaipalan, P.; Shahidi, F. Phenolics of selected cranberry genotypes (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.) and their antioxidant efficacy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 9342–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Wang, C.; Zou, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Tan, M.; Mei, Y.; Wei, L. Comparison of Multiple Bioactive Constituents in the Flower and the Caulis of Lonicera japonica Based on UFLC-QTRAP-MS/MS Combined with Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Molecules 2019, 24, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojakowska, A.; Perkowski, J.; Góral, T.; Stobiecki, M. Structural characterization of flavonoid glycosides from leaves of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using LC/MS/MS profiling of the target compounds. J. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 48, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Li, R.; Ren, L.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ma, D.; Luo, Y. A comparative metabolomics study of flavonoids in sweet potato with different flesh colors (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam). Food Chem. 2018, 260, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, X.-J.; Xu, W.; Huang, J.; Zhu, D.; Qiu, X.-H. Rapid Characterization and Identification of Flavonoids in Radix Astragali by Ultra-High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Linear Ion Trap-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015, 53, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Song, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S. Studies on principal components and antioxidant activity of different Radix Astragali samples using high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization multiple-stage tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta 2009, 78, 1090–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojakowska, A.; Piasecka, A.; Garcia-Lopez, P.M.; Zamora-Natera, F.; Krajewski, P.; Marczak, L.; Kachlicki, P.; Stobiecki, M. Structural analysis and profiling of phenolic secondary metabolites of Mexican lupine species using LC–MS techniques. Phytochemistry 2013, 92, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, K.P.R.; Raghu, A.V. Tentative characterization of phenolic compounds in three species of the genus Embelia by liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry analysis. Spectrosc. Lett. 2019, 52, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, C.; Foglia, P.; Pastorini, E.; Samperi, R.; Laganà, A. Identification and mass spectrometric characterization of glycosylated flavonoids in Triticum durum plants by high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry: An International Journal Devoted to the Rapid Dissemination of Up-to-the-Minute Research in Mass Spectrometry. Wiley Anal. Sci. 2005, 19, 3143–3158. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Su, W.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, P.; Zhang, W.; Liang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Peng, W.; Yao, H. UFLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS-Based Screening and Identification of Flavonoids and Derived Metabolites in Human Urine after Oral Administration of Exocarpium Citri Grandis Extract. Molecules 2018, 23, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.L.; Zhou, G.S.; Zhou, S.X.; Jiang, Y.; Tu, P.F. Polygalins D–G, four new flavonol glycosides from the aerial parts of Polygala sibirica L. (Polygalaceae). Nat. Prod. Res. Former. Nat. Prod. Lett. 2013, 27, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Jamous, R.M.; Arraes-Roman, D.; Segura-Carretero, A. HPLC–DAD–ESI-MS/MS screening of bioactive components from Rhus coriaria L. (Sumac) fruits. Food Chem. 2015, 166, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lu, H.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Shen, H.; Xu, W.; Ge, J.; He, D. Rapid qualitative profiling and quantitative analysis of phenolics in Ribes meyeri leaves and their antioxidant and antidiabetic activities by HPLC-QTOF-MS/MS and UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44, 1404–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aita, S.E.; Capriotti, A.L.; Cavaliere, C.; Cerrato, A.; Giannelli Moneta, B.; Montone, C.M.; Piovesana, S.; Lagana, A. Andean blueberry of the Genus Disterigma: A High-Resolution Mass Spectrometric Approach for the Comprehensive Characterization of Phenolic Compounds. Separations 2021, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Jiang, X.; Fang, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, B.; Pan, C.; Wu, H. Identification of key metabolites based on non-targeted metabolomics and chemometrics analyses provides insights into bitterness in Kucha [Camellia kucha (Chang et Wang) Chang]. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanhineva, K.; Karenlampi, S.O.; Aharoni, A. Recent Advances in Strawberry Metabolomics. In Genomics, Transgenics, Molecular Breeding and Biotechnology of Strawberry; Husaini, A.M., Mercado, J.A., Eds.; Global Science Books, UK: Ikenobe, Japan, 2011; pp. 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tian, T. Phytochemical Characterization of Mentha spicata L. Under Differential Dried-Conditions and Associated Nephrotoxicity Screening of Main Compound with Organ-on-a-Chip. Front. Pharm. 2018, 9, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafsanjany, N.; Senker, J.; Brandt, S.; Dobrindt, U.; Hensel, A. In Vivo Consumption of Cranberry Exerts ex Vivo Antiadhesive Activity against FimH-Dominated Uropathogenic Escherichia coli: A Combined in Vivo, ex Vivo, and in Vitro Study of an Extract from Vaccinium macrocarpon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8804–8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapesochnaya, G.G.; Kurkin, V.A.; Shchavlinskii, A.N. Flavonoids of the above-ground part of Rhodiola rosea. II. Structure of novel glycosides of herbacetin and gossypetin. Chem. Nat. Connect. 1985, 4, 496–507. [Google Scholar]

- Engels, C.; Gräter, D.; Esquivel, P.; Jiménez, V.M.; Gänzle, M.G.; Schieber, A. Characterization of phenolic compounds in jocote (Spondias purpurea L.) peels by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.; Abdelaziz, S.; Yousef, H. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of the Aqueous Fraction of Parkinsonea aculeata L. Growing in Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobeh, M.; Mahmoud, M.F.; Abdelfattah, M.A.O.; Cheng, H.; El-Shazly, A.M.; Wink, M. A proanthocyanidin-rich extract from Cassia abbreviata exhibits antioxidant and hepatoprotective activities in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 213, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, L.; Wyzgovski, F.J.; Scheerens, J.C.; Chanon, A.M.; Reese, R.N.; Smiljanic, D.; Wesdemiotis, C.; Blakeslee, J.J.; Riedl, K.M.; Rinaldi, P.L. Nonanthocyanin Secondary Metabolites of Black Raspberry (Rubus occidentalis L.) Fruits: Identification by HPLC-DAD, NMR, HPLC-ESI-MS, and ESI-MS/MS Analyses. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2013, 61, 12032–12043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Vorsa, N.; Harrington, P.; Chen, P. Nontargeted Metabolomic Study on Variation of Phenolics in Different Cranberry Cultivars Using UPLC-IM–HRMS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 12206–12216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Lindstedt, A.; Markkinen, N.; Sinkkonen, J.; Suomela, J.; Yang, B. Characterization of Metabolite Profiles of Leaves of Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) and Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 12015–12026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinola, V.; Pinto, J.; Castilho, P.C. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds of selected fruits from Madeira Island by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn and screening for their antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujor, O.-C. Extraction, Identification and Antioxidant Activity of the Phenolic Secondary Metabolites Isolated from the Leaves, Stems and Fruits of Two Shrubs of the Ericaceae Family. Ph.D. Thesis, Université d’Avignon, Avignon, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Edwards, A.; Jimenez-Aspee, F.; Theoduloz, C.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G. Colonic fermentation of polyphenols from Chilean currants (Ribes spp.) and its effect on antioxidant capacity and metabolic syndrome-associated enzymes. Food Chem. 2018, 258, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosic, M.; Trifkovic, J.; Vovk, I.; Gasic, U.; Tesic, Z.; Sikoparija, B.; Milojkovic-Opsenica, D. Phenolic Composition Influences the Health-Promoting Potential of Bee-Pollen. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, R.; Acquavia, M.A.; Cataldi, T.R.I.; Onzo, A.; Coviello, D.; Bufo, S.A.; Scrano, L.; Ciriello, R.; Guerrieri, A.; Bianco, G. Profiling of quercetin glycosides and acyl glycosides in sun-dried peperoni di Senise peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) by a combination of LC-ESI(-)-MS/MS and polarity prediction in reversed-phase separations. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 3005–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgonova, M.P.; Tekutyeva, L.A.; Podvolotskaya, A.B.; Stepochkina, V.D.; Zakharenko, A.M.; Golokhvast, K.S. Zostera marina L. Supercritical CO2-Extraction and Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Chemical Constituents Recovered from Seagrass. Separations 2022, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kumar, S.; Rathi, B.; Bhrara, K.; Chhikara, B.S. Therapeutic analysis of Terminalia arjuna plant extracts in combinations with different metal nanoparticles. J. Mater. NanoSci. 2015, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, N.-W.; Wang, S.-X.; Jia, L.-D.; Zhu, M.-C.; Yang, J.; Zhou, B.-J.; Yin, J.-M.; Lu, K.; Wang, R.; Li, J.-N.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Major Constituents in Different-Colored Rapeseed Petals by UPLC−HESI-MS/MS. Agricult. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11053–11065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, R.B.; Hamed, A.I.; Mahalel, U.A.; Al-Ayed, A.S.; Kowalczyk, M.; Moldoch, J.; Oleszek, W.; Stochmal, A. Tentative Characterization of Polyphenolic Compounds in the Male Flowers of Phoenix dactylifera by Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Mass Spectrometry and DFT. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, L.P.; Pereira, E.; Pires, T.C.S.P.; Alves, M.J.; Pereira, O.R.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Rubus ulmifolius Schott fruits: A detailed study of its nutritional, chemical and bioactive properties. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gu, L.; Prior, R.L.; McKay, S. Characterization of Anthocyanins and Proanthocyanidins in Some Cultivars of Ribes, Aronia, and Sambucus and Their Antioxidant Capacity. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7846–7856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.C.; Saha, S. Anthocyanin profiling of Berberis lycium Royle berry and its bioactivity evaluation for its nutraceutical potential. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.; Hermosin-Gutierrez, I.; Vergara, C.; von Baer, D.; Zapata, M.; Hitschfild, A.; Obando, L.; Mardones, C. Anthocyanin profiles in south Patagonian wild berries by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.; Hermosin-Gutierrez, I.; Mardones, C.; Vergara, C.; Herlitz, E.; Vega, M.; Dorau, C.; Winterhalter, P.; von Baer, D. Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity of Calafate (Berberis microphylla) Fruits and Other Native Berries from Southern Chile. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 51, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diretto, G.; Jin, X.; Capell, T.; Zhu, C.; Gomez-Gomez, L. Differential accumulation of pelargonidin glycosides in petals at three different developmental stages of the orange-flowered gential (Gentiana lutea L. var. aurantiaca). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212062. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, M.; Chawla, M.; Chunduri, V.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, N.K.; Kaur, N.; Kumar, A.; Mundey, J.K.; Saini, M.K.; et al. Transfer of grain colors to elite wheat cultivars and their characterization. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 71, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.A.O.; Freire, C.S.R.; Domingues, M.R.M.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Neto, C.P. Characterization of Phenolic Components in Polar Extracts of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. Bark by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 9386–9393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ieri, F.; Martini, S.; Innocenti, M.; Mulinacci, N. Phenolic Distribution in Liquid Preparations of Vaccinium myrtillus L. and Vaccinium vitis idaea L. Phytochem. Anal. 2013, 24, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengin, G.; Mahomoodally, F.; Ibrahime, S.; Ak, G.; Etienne, O.; Jugreet, S.; Brunetti, L.; Leone, S.; Cristina, S.; Di Simone, S. Chemical composition and biological properties of two Jatropha species: Different parts and different extraction methods. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razgonova, M.P.; Bazhenova, B.A.; Zabalueva, Y.Y.; Burkhanova, A.G.; Zakharenko, A.M.; Kupriyanov, A.N.; Sabitov, A.S.; Ercisli, S.; Golokhvast, K.S. Rosa davurica Pall., Rosa rugosa Thumb., and Rosa acicularis Lindl. originating from Far Eastern Russia: Screening of 146 Chemical Constituents in Tree Species of the Genus Rosa. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, X.; Li, G.; He, X.; Yu, X.; Yu, X.; Xiao, Q.; Xiang, Z.; Wang, C. Chemical constituents of radix Actinidia chinensis planch by UPLC–QTOF–MS. Biomedical Chromatography. Wiley Anal. Sci. 2021, 35, e5103. [Google Scholar]

- N’gaman-Kouassi, K.C.C.; Kabran, G.R.M.; Kadja, A.B.; Mamyrbékova-Békro, J.A.; Pirat, J.L.; Békro, Y.A. Phenolic phytoconstituents from Gmelina arborea leaves hydroacetonic crude extract: ULPC-MS/MS analysis. Der Chem. Sin. 2016, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y.; Shaari, K. LC–MS metabolomics analysis of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni leaves cultivated in Malaysia in relation to different developmental stages. Phytochem. Anal. 2021, 33, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ye, M.; Qiao, X.; Xu, M.; Wang, B.; Guo, D.-A. Characterization of phenolic compounds in the Chinese herbal drug Artemisia annua by liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2008, 47, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, F.; Legault, J.; Lavoie, S.; Mshvildadze, V.; Pichette, A. Isolation and Identification of Cytotoxic Compounds from the Wood of Pinus resinosa. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeberg, D.; Flate, P.-O.; Eikenes, M.; Fongen, M.; Naess-Andresen, C.F. Qualitative and quantitative determination of extractives in heartwood of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) by gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1109, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.-W.; Li, J.; Gao, X.-M.; Amponsem, E.; Kang, L.-Y.; Hu, L.-M.; Zhang, B.-L.; Chang, Y.-X. Simultaneous determination of stilbenes, phenolic acids, flavonoids and anthraquinones in Radix polygoni multiflori by LC–MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012, 62, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedoreyev, S.A.; Pokushalova, T.V.; Veselova, M.V.; Glebko, L.I.; Kulesh, N.I.; Muzarok, T.I.; Seletskaya, L.D.; Bulgakov, V.P.; Zhuravlev, Y.N. Isoflavonoid production by callus cultures of Maackia amurensis. Fitoterapia 2000, 71, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Oh, S.; Noh, H.B.; Ji, S.; Lee, S.H.; Koo, J.M.; Choi, C.W.; Jhun, H.P. In Vitro Antioxidant and Anti-Propionibacterium acnes Activities of Cold Water, Hot Water, and Methanol Extracts, and Their Respective Ethyl Acetate Fractions, from Sanguisorba officinalis L. Roots. Mol. 2018, 23, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perchuk, I.; Shelenga, T.; Gurkina, M.; Miroshnichenko, E.; Burlyaeva, M. Composition of Primary and Secondary Metabolite Compounds in Seeds and Pods of Asparagus Bean (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) from China. Molecules 2020, 25, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Guerra-Hernández, E.; Cerretani, L.; García-Villanova, B.; Verardo, V. Comprehensive metabolite profiling of Solanum tuberosum L.(potato) leaves by HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgonova, M.; Boiko, A.; Zinchenko, Y.; Tikhonova, N.G.; Sabitov, A.S.; Zakharenko, A.; Golokhvast, K.S. Actinidia deliciosa: A high-resolution mass spectrometric approach for the comprehensive characterization of bioactive compounds. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2023, 47, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, J.; He, Y.; Shi, M.; Han, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Wen, X. Metabolic Profiling of Pitaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus) during Fruit Development and Maturation. Molecules 2019, 24, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsoy-Toplan, G.; Goger, F.; Yildiz-Pekoz, A.; Gibbons, S.; Sariyar, G.; Mat, A. Chemical Constituents of the Different Parts of Colchicum micranthum and C. chalcedonicum and their Cytotoxic Activities. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 535–538. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez Montenegro, Z.J.; Alvarez-Rivera, G.; Mendiola, J.A.; Ibanez, E.; Cifuentes, A. Extraction and Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Terpenes Recovered from Olive Leaves Using a New Adsorbent-Assisted Supercritical CO2 Process. Foods 2021, 10, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgonova, M.P.; Cherevach, E.I.; Tekutyeva, L.A.; Fedoreev, S.A.; Mishchenko, N.P.; Tarbeeva, D.V.; Demidova, E.N.; Kirilenko, N.S.; Golokhvast, K.S. Maackia amurensis Rupr. et Maxim.: Supercritical CO2-extraction and Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Chemical Constituents. Molecules 2023, 28, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yang, B.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Miao, X.; Yang, W. The Chemical Composition of Brazilian Green Propolis and Its Protective Effects on Mouse Aortic Endothelial Cells against Inflammatory Injury. Molecules 2020, 25, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifan, A.; Zengin, G.; Sinan, K.I.; Sieniawska, E.; Sawicki, R.; Maciejewska-Turska, M.; Skalikca-Wozniak, K.; Luca, S.V. Unveiling the Phytochemical Profile and Biological Potential of Five Artemisia Species. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, K.; Tong, C.; Fu, Q.; Xu, J.; Shi, S.; Xiao, Y. Identification of minor lignans, alkaloids, and phenylpropanoid glycosides in Magnolia officinalis by HPLC-DAD-QTOF-MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 170, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wei, L.; Chen, D.; Chen, Q.; Jiao, M.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Gong, Z.; Kang, N.; et al. The Molecular Mechanism of Antioxidation of Huolisu Oral Liquid Based on Serum Analysis and Network Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 710976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.T.; Wu, X.; Rui, W.; Guo, J.; Feng, Y.F. UPLC/Q-TOF-MS Analysis for Identification of Hydrophilic Phenolics and Lipophilic Diterpenoids from Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae. Acta Chromatogr. 2015, 27, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Ha, J.S.; Kim, J.M.; Kang, J.Y.; Lee, D.S.; Guo, T.J.; Lee, U.; Kim, D.-O.; Heo, H.J. Antiamnesic Effect of Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) Leaves on Amyloid Beta (Aβ)1–42-Induced Learning and Memory Impairment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 3353–3361. [Google Scholar]

- Heffels, P.; Muller, L.; Schieber, A.; Weber, F. Profiling of iridoid glycosides in Vaccinium species by UHPLCMS. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, E.Y.A.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R.; Lampi, A.-M.; Kanninen, M.; Luukkanen, O.; Sipi, M.; Lehtonen, M.; Vuorela, H.; Fyhrquist, P. Terminalia laxiflora and Terminalia brownii contain a broad spectrum of antimycobacterial compounds including ellagitannins, ellagic acid derivatives, triterpenes, fatty acids and fatty alcohols. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 227, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Pelayo, R.; Hornero-Mendez, D. Identification and Quantitative Analysis of Carotenoids and Their Esters from Sarsaparilla (Smilax aspera L.) Berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8225–8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, M.; Giuffrida, D.; Salafia, F.; Giofre, S.V.; Mondello, L. Carotenoids and apocarotenoids determination in intact human blood samples by online supercritical fluid extraction-supercritical fluid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1032, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murador, D.C.; Salafia, F.; Zoccali, M.; Martins, P.L.G.; Ferreira, A.G.; Dugo, P.; Mondello, L.; de Rosso, V.V.; Giuffrida, D. Green Extraction Approaches for Carotenoids and Esters: Characterization of Native Composition from Orange Peel. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzbach, L.; Pfeiffer, A.; Weber, F.; Schieber, A. Characterization of carotenoid profiles in goldenberry (Physalis peruviana L.) fruits at various ripening stages and in different plant tissues by HPLC-DADAPCI-MSn. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penagos-Calvete, D.; Guauque-Medina, J.; Villegas-Torres, M.F.; Montoya, G. Analysis of triacylglycerides, carotenoids and capsaicinoids as disposable molecules from Capsicum agroindustry. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 60, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Duan, W.; Sun, J.; Zhao, C.; Cheng, Q.; Li, C.; Peng, G. Structural Identification and Conversion Analysis of Malonyl Isoflavonoid Glycosides in Astragali Radix by HPLC Coupled with ESI-Q TOF/MS. Molecules 2019, 24, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, S.; Sun, J.; Duan, W.; Li, C.; Peng, G.; Zheng, Y. RRLC-QTOF/MS-Based Metabolomics Reveal the Mechanism of Chemical Variations and Transformations of Astragali Radix as a Result of the Roasting Process. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 903168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, Q.; Qiao, C.; Song, J.; Cheng, C.L.; Xu, H. Chemical markers for the quality control of herbal medicines: An overview. Chin. Med. 2008, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class of Compounds | Identification | Formula | Retention Time | Observed Mass [M-H]- | Observed Mass [M+H]+ | MS/MS Stage 1 Fragmentation | MS/MS Stage 2 Fragmentation | MS/MS Stage 3 Fragmentation | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flavone | Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 20.2 | 271 | 225 | 179 | Phlomis (Lamiaceae) [16]; Olive oil [17]; Mentha [18]; L. henryl [19] | ||

| 2 | Flavone | Trihydroxy(iso)flavone | C15H10O5 | 25.6 | 271 | 197 | 129 | Propolis [20] | ||

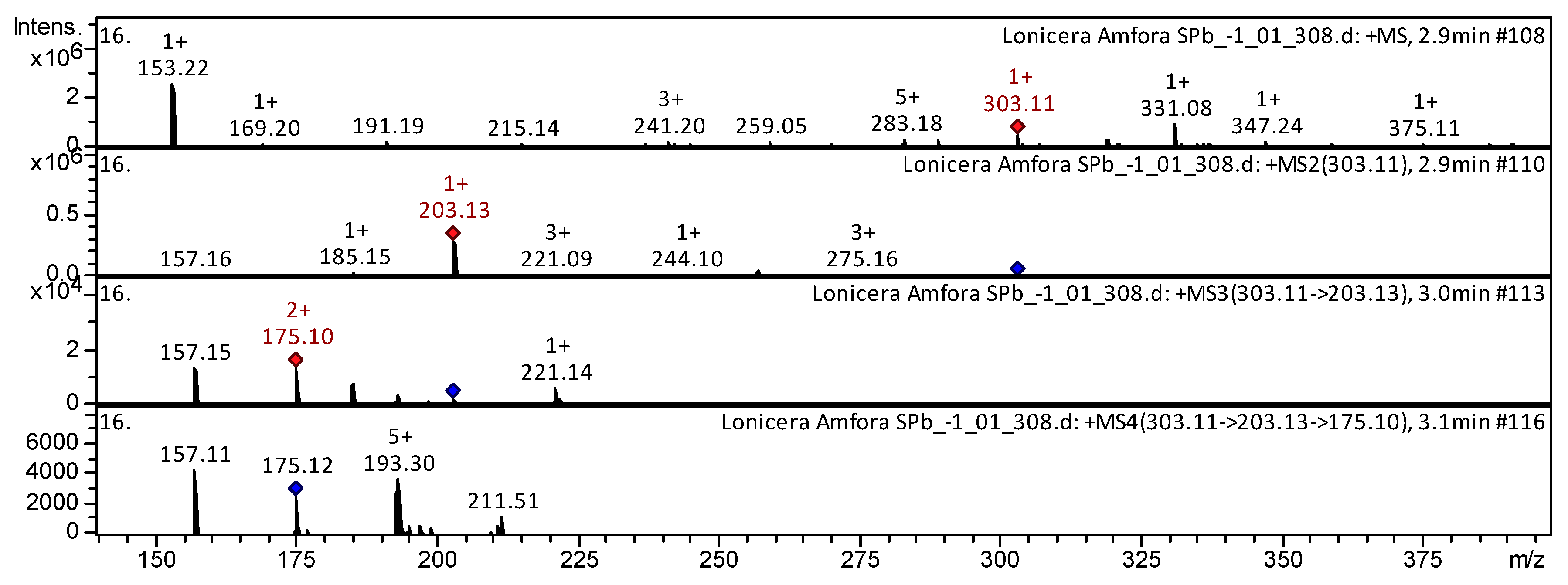

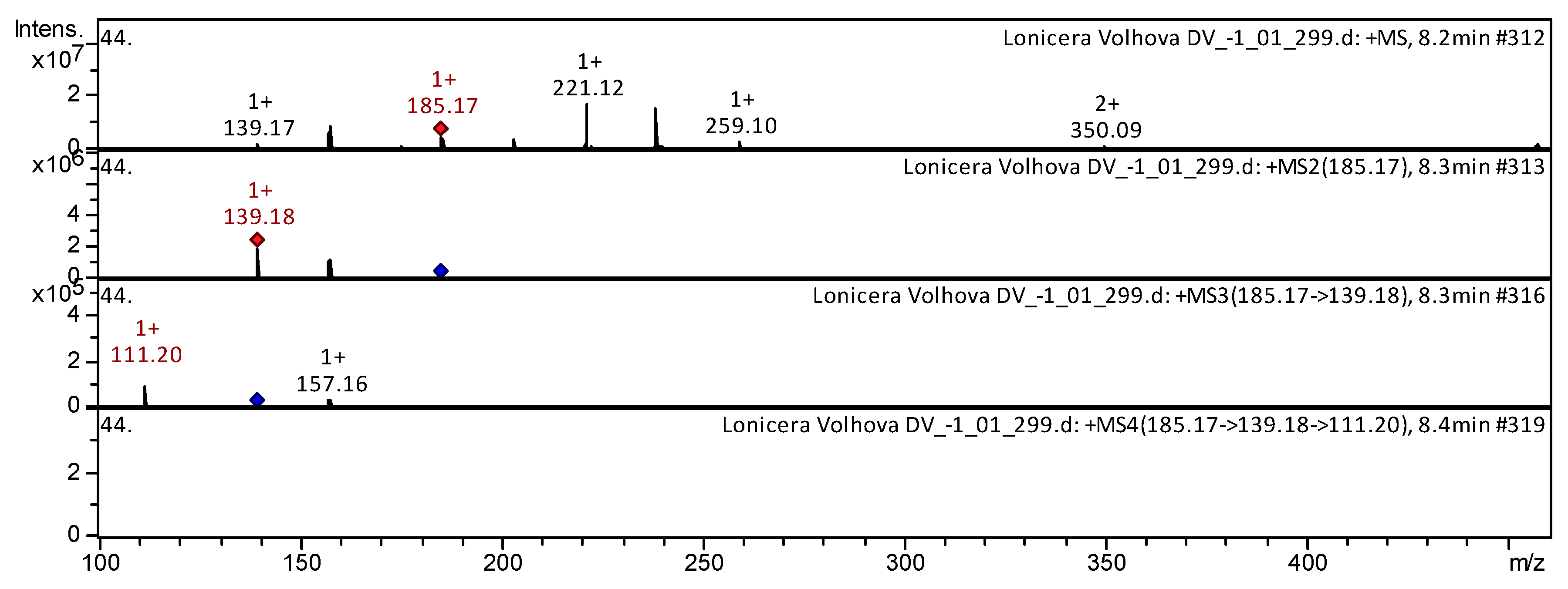

| 3 | Flavone | 5,6,4′-Trihydroxy-7,8-dimethoxyflavone | C17H14O7 | 24.4 | 331 | 303; 185 | 203 | 157 | Mentha [21]; F. glaucescens; F. herrerae [22] | |

| 4 | Flavone | Jaceosidin [5,7,4′-trihydroxy-6′,5′-dimetoxyflavone] * | C17H14O7 | 33.2 | 331 | 303; 203 | 203; 157 | 175 | Mentha [18,21] | |

| 5 | Flavone | Cirsiliol * | C17H14O7 | 34.0 | 329 | 229; 311 | 211 | 211 | Ocimum [23] | |

| 6 | Flavone | Sophoraisoflavone A * | C20H16O6 | 33.7 | 353 | 335; 294; 235; 195 | 317; 277; 229 | Chinese herbal formula Jian-Pi-Yi-Shen pill [24] | ||

| 7 | Flavone | Pentahydroxy dimethoxyflavone * | C17H14O9 | 35.6 | 363 | 344; 300; 256 | 238; 146 | G. linguiforme [22] | ||

| 8 | Flavone | Dihydroxy-tetramethoxy(iso)flavone * | C19H18O8 | 27.5 | 375 | 345 | 245 | 175; 227 | Propolis [20] | |

| 9 | Flavone | Luteolin 7-O-glucoside [Cynaroside] | C21H20O11 | 27.1 | 449 | 297 | 269 | 241 | L. henryi [19]; V. macrocarpon [25]; L. japonica [26] | |

| 10 | Flavone | Chrysoeriol O-hexoside * | C22H22O11 | 7.3 | 463 | 445; 243 | T. aestivum L. [27]; Ipomoea batatas [28] | |||

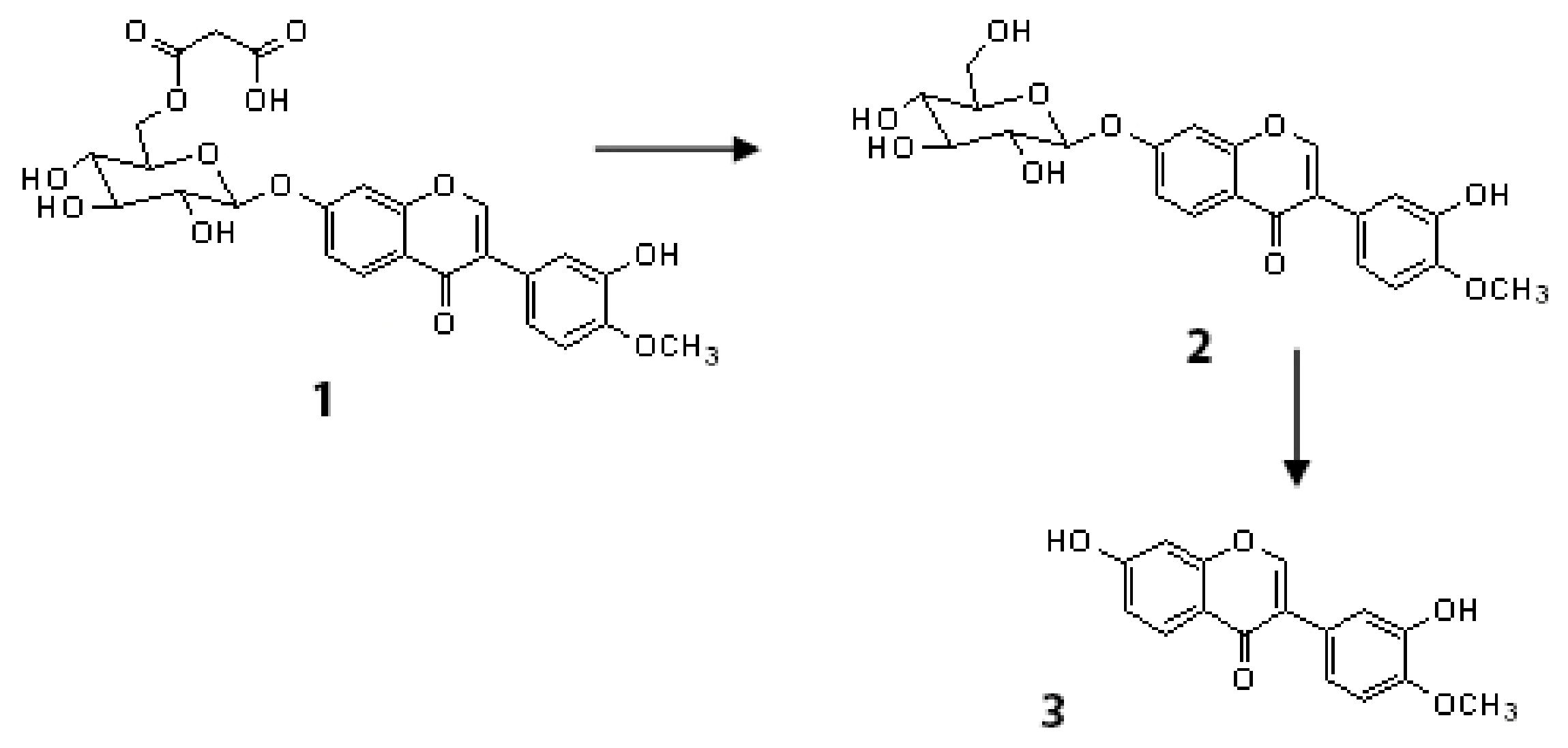

| 11 | Flavone | Formononetin-7-O-glucoside-6″-O-malonate * | C25H24O12 | 18.7 | 517 | 271 | 243 | Astragali radix [29,30] | ||

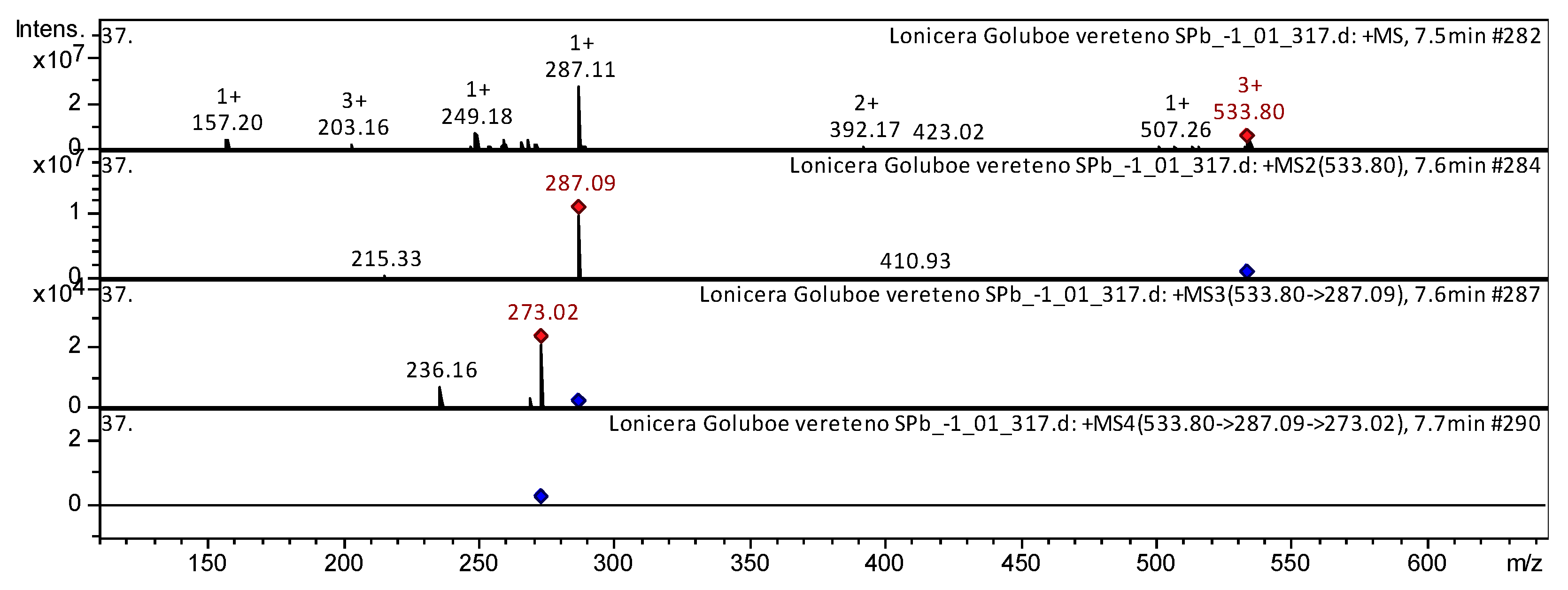

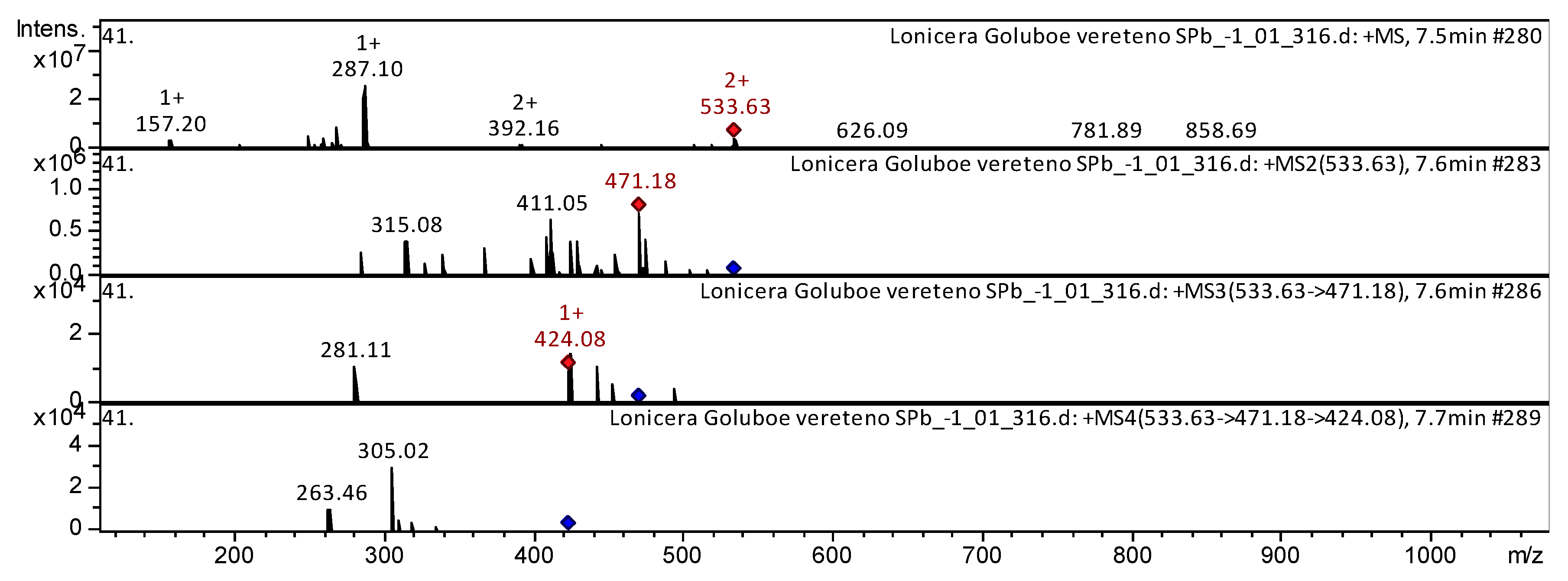

| 12 | Flavone | Acacetin 8-C-glucoside malonylated * | C25H24O13 | 44.6 | 533 | 471; 411; 315 | 424; 281 | 305; 263 | Mexican lupine species [31] | |

| 13 | Flavone | Calycosin-7-O-β-D-glucoside-6″-O-malonate * | C25H24O13 | 7.5 | 533 | 287 | 273; 236 | Radix astragali [29,30] | ||

| 14 | Flavone | Chrysin derivative | C26H24O14 | 44.8 | 559 | 277 | 233; 177 | Embelia [32] | ||

| 15 | Flavone | C-hexosyl-apigenin O-rhamnoside * | C27H30O14 | 36.2 | 579 | 561; 337; 317 | 319; 262 | 161 | T. aestivum [33] | |

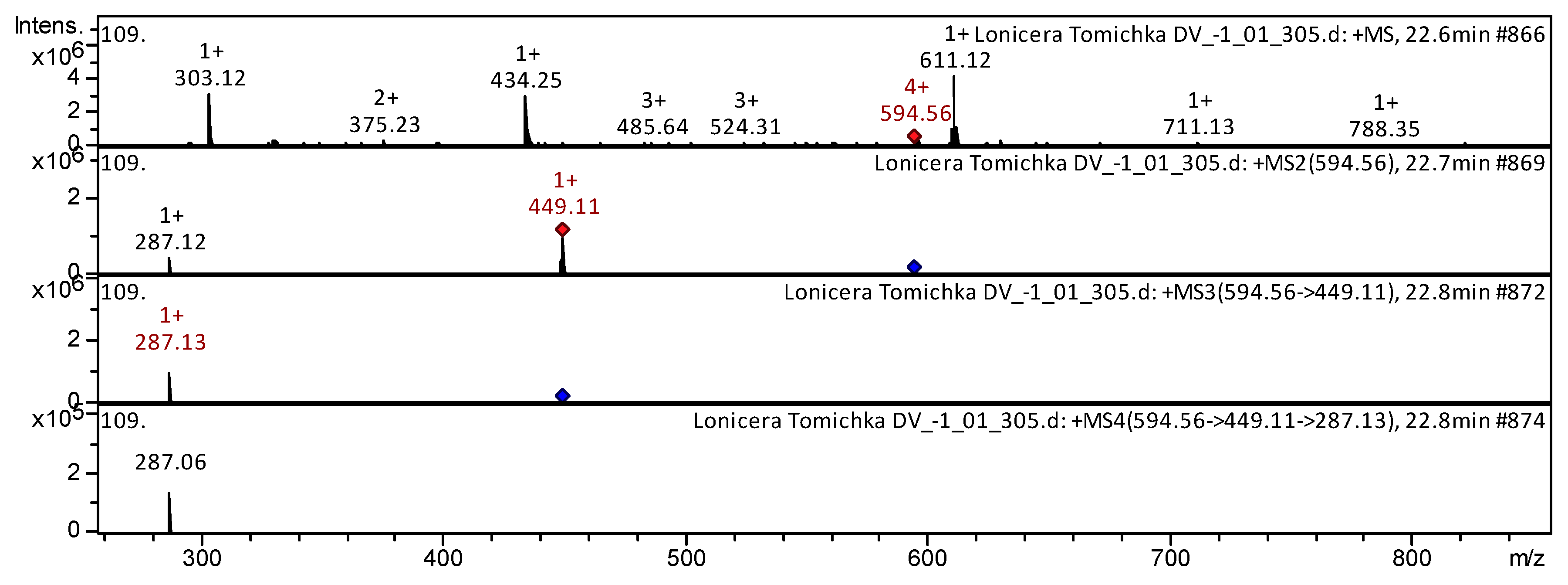

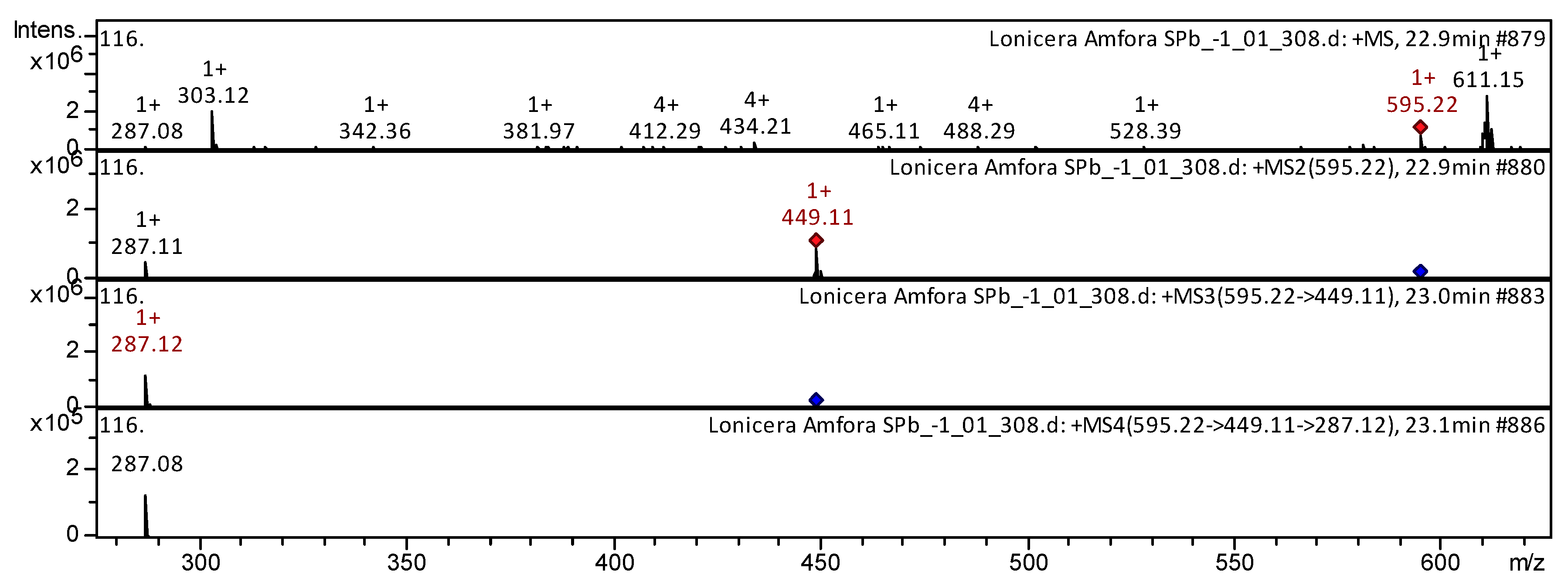

| 16 | Flavone | Lonicerin [Luteolin-7-O-Rhamnoside; Veronicastroside; Scolymoside; Luteolin-7-Rhamnoglucoside] | C27H30O15 | 22.8 | 595 | 449; 287 | 287 | 287; 153 | L. japonica [26]; Exocarpium Citri Grandis [34] | |

| 17 | Flavone | Luteolin 7-O-(6-O-arabinosyl-glucoside) | C26H28O15 | 22.9 | 581 | 287 | 153; 241; 287 | L. henryi [19] | ||

| 18 | Flavonol | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | 23.0 | 287 | 269; 149 | 239; 181 | L. japonica [26]; P. sibirica [35]; Rhus coriaria [36]; R. meyeri [37]; Andean blueberry [38] | ||

| 19 | Flavonol | Dihydrokaempferol | C15H12O6 | 25.4 | 287 | 259 | 215 | 173 | Andean blueberry [38]; Camellia kucha [39]; Strawberry [40] | |

| 20 | Flavonol | Rhamnocitrin * | C16H12O6 | 27.5 | 301 | 273 | 245 | 217; 177; 131 | Astragali radix [29]; Mentha [41] | |

| 21 | Flavonol | Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 31.3 | 303 | 257; 146 | 229 | 201; 145 | Propolis [20]; Ocimum [23]; V. macrocarpon [25,42]; Rhus coriaria [36]; R. meyeri [37] | |

| 22 | Flavonol | Herbacetin [3,5,7,8-Tetrahydroxy-2-(4-hydro- xyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one] * | C15H10O7 | 26.6 | 303 | 203 | 175 | Rhodiola rosea [43] | ||

| 23 | Flavonol | Rhamnetin II * | C16H12O7 | 32.9 | 317 | 302 | 274; 153; 121 | 229; 153; 121 | P. sibirica [35]; Rhus coriaria L. (Sumac) [36]; Spondias purpurea [44] | |

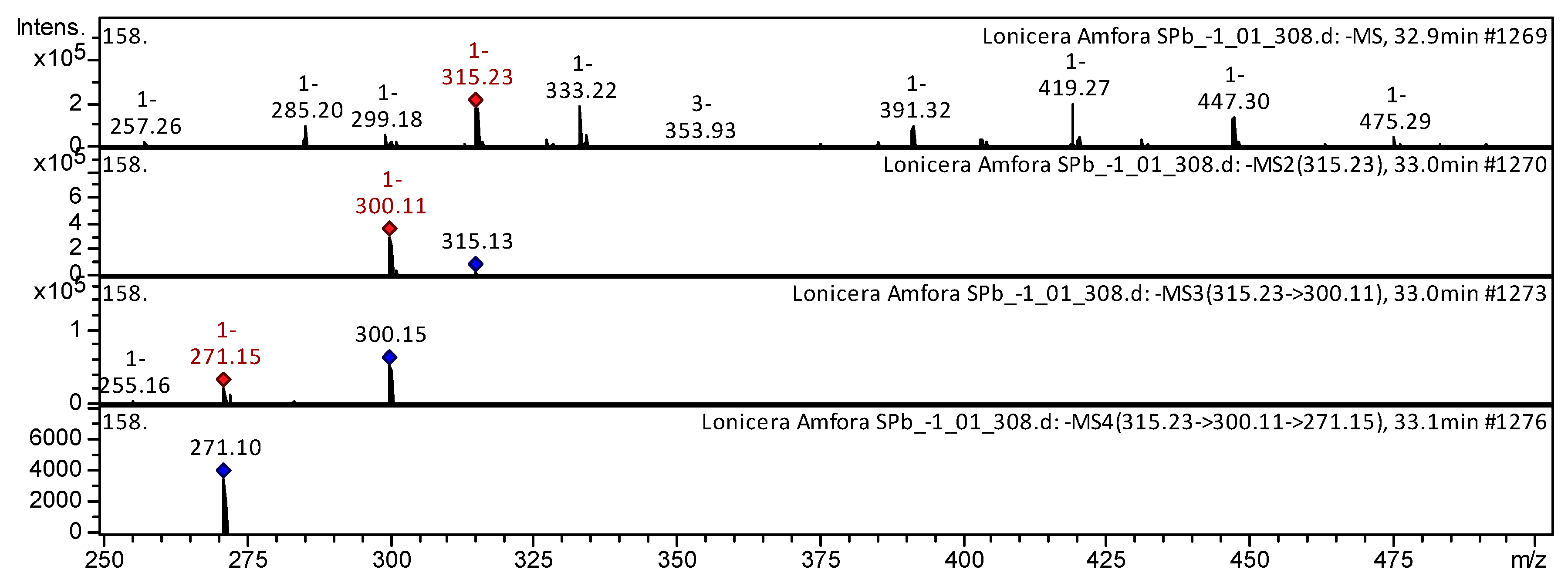

| 24 | Flavonol | Isorhamnetin [Isorhamnetol; Quercetin 3′-Methyl ether; 3-Methylquercetin] | C16H12O7 | 24.4 | 315 | 283 | 255; 211 | 227 | Andean blueberry [38]; V. macrocarpon [42]; Spondias purpurea [44] | |

| 25 | Flavonol | Kaempferol-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside * | C21H20O10 | 22.9 | 433 | 287 | 187 | C.edulis; F. glaucescens [22]; Rhus coriaria [36]; P. aculeata [45]; Cassia abbreviata [46] | ||

| 26 | Flavonol | Quercetin 3-O- glucoside [Isoquercitrin; Hirsutrin; Quercetin-3-O-Glucopyranoside; 3-Glucosylquercetin] | C21H20O12 | 23.4 | 465 | 303 | 229; 165 | 201; 161 | L. henryi [19]; L. japonica [26]; Ribes meyeri [37]; Andean blueberry [38]; Spondias purpurea [44]; R. occidentalis [47]; Cranberry [48]; V. myrtillus [49] | |

| 27 | Flavonol | Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside | C27H30O15 | 22.6 | 595 | 449; 287 | 287 | 287 | L. japonica [26]; R. meyeri [37]; Spondias purpurea [44]; Strawberry [50] | |

| 28 | Flavonol | Quercetin 3-O-pentosyl hexoside | C26H28O16 | 21.9 | 597 | 303; 257; 211 | 257; 195; 165 | 229 | F. pottsii [22]; Spondias purpurea [44]; V. myrtillus [51] | |

| 29 | Flavonol | Rutin (Quercetin 3-O-rutinoside) | C27H30O16 | 22.1 | 611 | 303 | 257; 165 | 229 | L. henryi [19]; L. japonica [26]; Ribes meyeri [37]; Spondias purpurea [44]; R. occidentalis [47]; R. magellanicum [52] | |

| 30 | Flavonol | Isorhamnetin 3-O-(6″-O-rhamnosyl-hexoside) | C28H32O16 | 24.3 | 625 | 317 | 302 | L. henryi [19]; Bee-pollen [53] | ||

| 31 | Flavonol | Dimethylquercetin-3-O-dehexoside * | C29H34O17 | 38.4 | 653 | 507; 353; 311 | 329 | 287; 190 | Capsicum annuum [54] | |

| 32 | Flavonol | Derivative of Quercetin rhamnosyl hexoside | C36H46O22 | 8.5 | 829 | 609 | 301 | 300 | Pubchem | |

| 33 | Flavan-3-ol | Epiafzelechin [(epi)Afzelechin] * | C15H14O5 | 19.4 | 275 | 245; 219; 175 | 215; 193; 175; 157; 127 | 175; 157; 145 | A. cordifolia; F. glaucescens; F. herrerae [22]; Cassia abbreviata [46] | |

| 34 | Flavan-3-ol | (Epi)-catechin | C15H14O6 | 22.6 | 291 | 273; 137 | V. macrocarpon [25]; Andean blueberry [38]; Rubus occidentalis [47]; Cranberry [48]; V. myrtillus [49,51] | |||

| 35 | Flavan-3-ol | Gallocatechin [+(−)Gallocatechin] | C15H14O7 | 55.3 | 307 | 261; 243; 163; 137 | 187; 159 | 131 | G. linguiforme [22]; Embelia [32]; R. meyeri [37]; V. myrtillus [51] | |

| 36 | Flavan-3-ol | (Epi)-afzelechin derivative | C18H16O10 | 19.1 | 393 | 275; 245; 215 | 245; 175 | 175; 127 | Zostera marina [55] | |

| 37 | Flavan-3-ol | (Epi)-catechin derivative | C18H16O11 | 19.4 | 409 | 291; 275 | 261; 242; 208; 173 | 244; 214; 191; 173; 160; 124 | Pubchem | |

| 38 | Flavan-3-ol | (−)-Epicatechin Gallate [(−)-Epicatechin-3-O-Gallate; L-Epicatechin Gallate] * | C22H18O10 | 23.3 | 441 | 330; 139 | 150 | Chinese herbal formula Jian-Pi-Yi-Shen pill [24]; R. meyeri [37]; Camellia kucha [39]; Cassia abbreviates [46]; Terminalia arjuna [56] | ||

| 39 | Flavanone | Naringenin [Naringetol; Naringenine] * | C15H12O5 | 31.3 | 273 | 153; 189 | 111 | G. linguiforme [22]; Mexican lupine species [31]; Exocarpium Citri Grandis [33]; Andean blueberry [38]; Rapeseed petals [57] | ||

| 40 | Flavanone | Butin [7,3′,4′-Trihydroxyflavanone] * | C15H12O5 | 31.7 | 273 | 153 | 171 | 153 | Ribes meyeri [38] | |

| 41 | Anthocyanin | Anthocyanidin [cyanidin chloride; Cyanidin] | C15H11O6+ | 7.9 | 287 | 286; 270; 247; 205 | 221 | F. herrerae [22]; Andean blueberry [38]; Phoenix dactylifera [58] | ||

| 42 | Anthocyanin | Petunidin | C16H13O7+ | 35.6 | 318 | 256 | 238; 113 | 238 | A. cordifolia; C. edulis [22] | |

| 43 | Anthocyanin | Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside (callistephin) | C21H21O10 | 25.9 | 431 | 257; 331 | 227 | 215 | R. ulmifolius [59]; Black currant, Elderberry [60] | |

| 44 | Anthocyanin | Delphinidin 3-O-glucoside | C21H21O12+ | 23.3 | 465 | 303 | 257; 165 | 229; 201 | R. magellanicum [52]; Black currant [60]; B. lycium [61]; B. ilicifolia; B.s empetrifolia; R. maellanicum; R. cucullatum; M. nummalaria [62]; B. microphylla [63] | |

| 45 | Anthocyanin | Pelargonidin 3-O-(6-O-malonyl-β-D-glucoside) | C24H23O13 | 11.8 | 519 | 271 | 243 | 197 | Gentiana lutea [64]; T. aestivum [65] | |

| 46 | Anthocyanin | Delphinidin 3-O-β-D-sambubioside | C26H29O16 | 21.6 | 597 | 303; 465; 229 | 229; 165 | 201; 172 | Red currant [60]; B. microphylla [63]; T. aestivum [65] | |

| 47 | Anthocyanin | Delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside [Tulipanin; Delphinidin 3-Rhamnosyl-Glucoside] | C27H31O16 | 22.4 | 611 | 303 | 257; 165 | 229 | Black currant [60]; B. ilicifolia; B. empetrifolia; R. maellanicum; R. cucullatum [62]; B. microphylla [63] | |

| 48 | Anthocyanin | Petunidin-3-rutinoside | C28H33O16 | 24.2 | 625 | 317; 479 | 302; 139 | 274; 229; 153 | Black currant [60]; B. ilicifolia; B. empetrifolia [62]; B. microphylla [63] | |

| 49 | Hydroxybenzoic acid (Phenolic acid) | Protocatechuic acid | C7H6O4 | 29.8 | 155 | 127 | V. macrocarpon [25]; L. japonica [26]; R. meyeri [37] | |||

| 50 | Hydroxycinnamic acid | Caffeic acid [(2E)-3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)acrylic acid] | C9H8O4 | 13.3 | 181 | 135 | 119 | V. macrocarpon [25]; L. japonica [26]; R. meyeri [37]; Strawberry [40]; R. occidentalis [47]; V. myrtillus [49] | ||

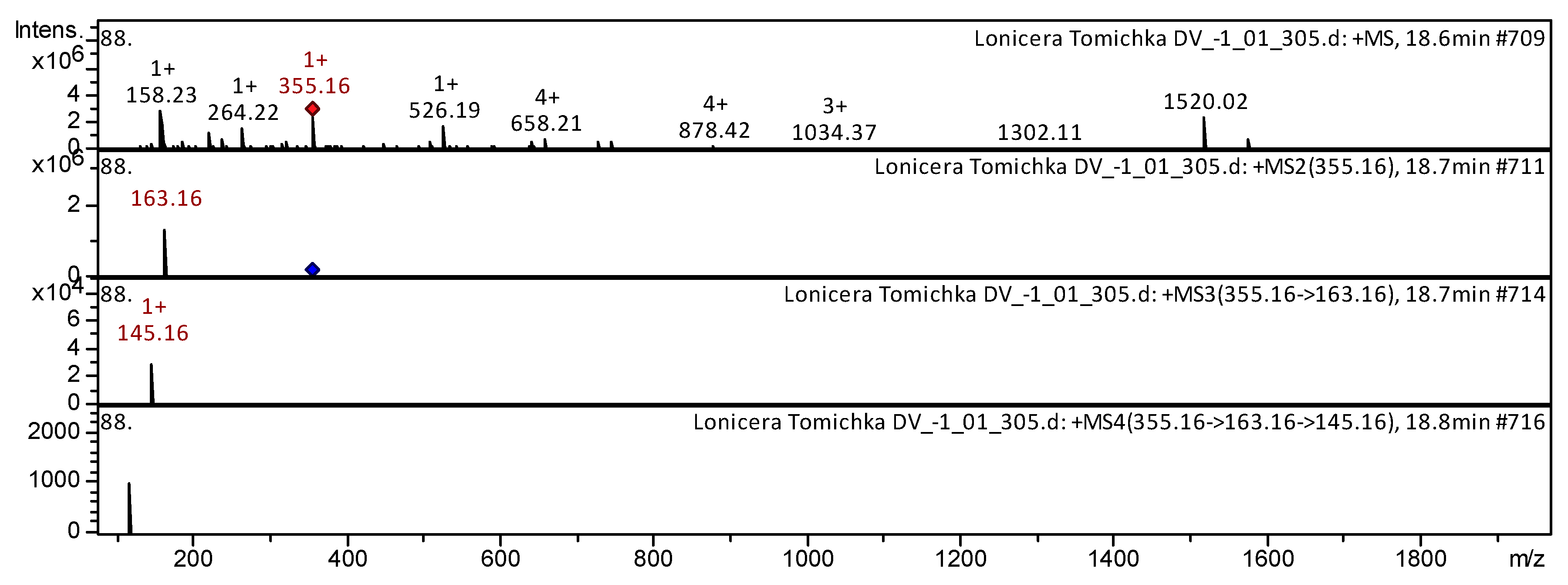

| 51 | Methylbenzoic acid | Methylgallic acid [Methyl gallate] * | C8H8O5 | 15.3 | 185 | 139 | 111 | Rhus coriaria [36]; Papaya [50]; Eucalyptus [66] | ||

| 52 | Trans-cinnamic acid | Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 7.3 | 193 | 176 | 132 | V. macrocarpon [25]; L. japonica [26]; Andean blueberry [38]; R. nigrum [67]; | ||

| 53 | Phenolic acid | Hydroxy methoxy dimethylbenzoic acid * | C10H12O4 | 20.4 | 197 | 188 | 179 | F. herrerae; F. glaucescens [22] | ||

| 54 | Phenolic acid | 2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxybenzoic acid * | C7H6O7 | 8.6 | 203 | 156 | 129 | Jatropha [68] | ||

| 55 | Hydroxycinnamic acid | Hydroxyferulic acid * | C10H10O5 | 8.1 | 211 | 193 | 75; 147 | 157; 129 | Andean blueberry [38]; Strawberry [40]; Rosa davurica [69] | |

| 56 | Hydroxycinnamic acid | Sinapic acid [trans-Sinapic acid] | C11H12O5 | 29.2 | 225 | 207; 179 | 151; 123 | 123 | V. macrocarpon [25]; Cranberry [48]; Andean blueberry [38] | |

| 57 | Phenolic acid | 2,4,6-Trihydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid * | C9H10O7 | 35.6 | 230 | 212 | 195 | Actinidia [70] | ||

| 58 | Hydroxybenzoic acid (Phenolic acid) | Ellagic acid [Benzoaric acid; Elagostasine; Lagistase; Eleagic acid] | C14H6O8 | 21.7 | 301 | 257 | 229 | 201 | Rubus occidentalis [47]; Eucalyptus [66] | |

| 59 | Phenolic acid | 6-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside * | C14H20O10 | 8.4 | 347 | 301; 165 | 165; 137 | Actinidia [70] | ||

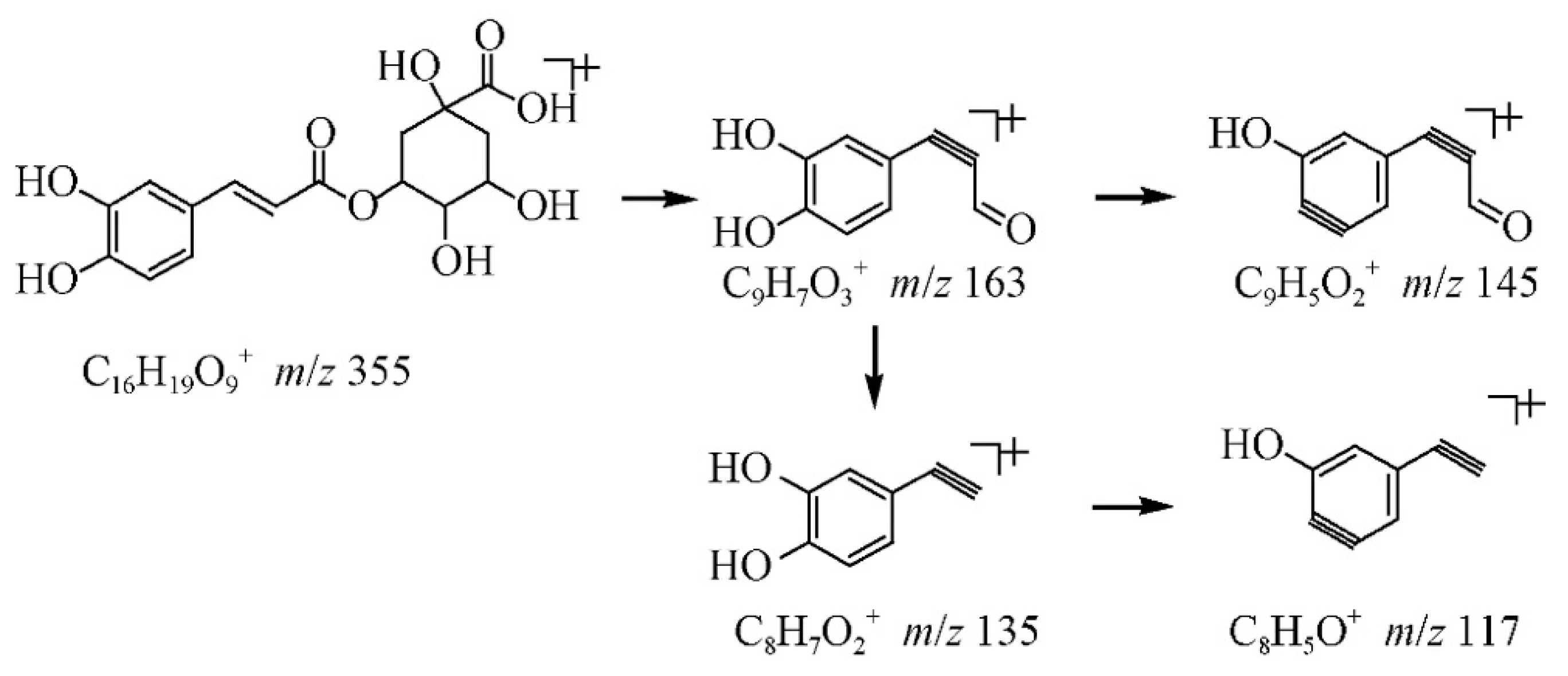

| 60 | Phenylpropanoid (cinnamic acid derivative glycoside); Hydroxycinnamic acid; | Chlorogenic acid [3-O-Caffeoylquinic acid] | C16H18O9 | 18.5 | 353 | 191 | 127 | L. henryi [19]; L. japonica [26]; V. macrocarpon [25,42]; Andean blueberry [38]; Strawberry [40]; Spondias purpurea [44]; Cranberry [48]; V. myrtillus [49]; R. magellanicum [52] | ||

| 61 | Hydroxycinnamic acid; | 3-O-Hydroxydihydrocaffeoylquinic acid | C16H20O10 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 191 | 173; 127 | L. henryi [19] | ||

| 62 | Phenolic acid | Caffeoylquinic acid derivative | 25.5 | 381 | 179; 135 | 135 | V. myrtillus [51] | |||

| 63 | Flavonoid | p-Coumaroylhexose-4-O-hexoside * | C25H28O10 | 23.3 | 489 | 327 | 299; 253 | 253; 225 | Strawberry [40]; Gmelina arborea [71] | |

| 64 | Phenolic acid | 3,4-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid [Isochlorogenic acid B] | C25H24O12 | 23.7 | 515 | 353 | 191 | 173 | L. henryi [19]; L. japonica [26]; Stevia rebaudiana [72] | |

| 65 | Phenolic acid | 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid [Isochlorogenic acid C] | C25H24O12 | 24.7 | 515 | 353 | 191 | 171 | L. henryi [19]; L. japonica [26]; Lemon [50] | |

| 66 | Phenolic acid | p-Coumaroyl malonyldihexose | 23.8 | 575 | 413; 335; 188 | 395; 340; 226; 188 | 346; 290; 211 | V. myrtillus [51] | ||

| 67 | Phenolic acid | Dicaffeoylferuoylquinic acid * | 42.5 | 693 | 353; 261 | 335; 261; 135 | 243; 149 | Artemisia annua [73] | ||

| 68 | Stilbene | Pinosylvin [3,5-Stilbenediol; Trans-3,5-Dihydroxystilbene] * | C14H12O2 | 32.7 | 213 | 167; 139 | 139 | P. resinosa [74]; P. sylvestris [75] | ||

| 69 | Stilbene | Resveratrol [trans-Resveratrol; 3,4′,5-Trihydroxystilbene; Stilbentriol] * | C14H12O3 | 20.3 | 229 | 211 | 183; 127 | 138 | A. cordifolia; F. glaucescens; F. herrerae [22]; Embelia [32]; Radix polygoni multiflori [76] | |

| 70 | Stilbene | Dihydroresveratrol [Alpha, Beta-Dihydroresveratrol] * | C14H14O3 | 19.4 | 231 | 214; 158 | 196; 168 | Maackia amurense [77] | ||

| 71 | Hydroxycoumarin | Umbelliferone [Skimmetin; Hydragin] * | C9H6O3 | 16.5 | 163 | 145 | 117 | F. glaucescens [22]; Actinidia [70]; Zostera marina [55]; S. officinalis [78] | ||

| 72 | Coumarin | Fraxetin * | C10H8O5 | 23.7 | 209 | 191 | 117 | Embelia [32]; Actinidia [70]; Jatropha [68] | ||

| 73 | Coumarin | 3,4/6,8-Dihydro-5,7-dihydroxy-2-oxo-2H-1-benzopyran-3-acetic acid | C11H10O6 | 7.3 | 239 | 221 | 203 | 185 | Actinidia [70] | |

| 74 | Coumarin | Umbelliferone hexoside * | C15H16O8 | 52.8 | 325 | 289; 127 | 271; 127 | 253; 146 | G. linguiforme [22] | |

| 75 | Coumarin | 7-(β-D-Glucopyranoside/galactopyranoside)-2-oxo-2H-1-benzopyran-4-acetic acid | C17H18O10 | 6.7 | 383 | 163; 365 | 145 | Actinidia [70] | ||

| OTHERS | ||||||||||

| 76 | Amino acid | L-Proline [(2-Pyrrolidinecarboxylic acid] | C5H9NO2 | 16.3 | 116 | 70 | L. japonica [26]; V. unguiculata [79] | |||

| 77 | Non-proteinogenic L-alpha-amino acid | L-Pyroglutamic acid [Pidolic acid; 5-Oxo-L-Proline] * | C5H7NO3 | 7.8 | 130 | 111 | Potato leaves [80] | |||

| 78 | Amino acid | L-Histidine | C6H9N3O2 | 26.2 | 156 | 129 | 110 | L. japonica [26]; Camellia kucha [39]; Actinidia deliciosa [81] | ||

| 79 | Amino acid | L-threanine | C7H14N2O3 | 7.6 | 175 | 157; 129 | 129; 115 | Camellia kucha [39] | ||

| 80 | Amino acid | L-Arginine | C6H14N4O2 | 9.9 | 175 | 130 | 111 | L. japonica [26]; Hylocereus polyrhizus [82] | ||

| 81 | Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | Shikimic acid [L-Schikimic acid] * | C7H10O5 | 8.1 | 175 | 157 | 129 | 111 | A. cordifolia [22]; R. meyeri [37]; Camellia kucha [39] | |

| 82 | Tricarboxylic acid | Citric acid [Anhydrous; Citrate] | C6H8O7 | 6.7 | 191 | 111; 173 | Mentha [18]; Strawberry, Lemon, Cherimoya, Papaya, Passion fruit [50]; V. unguiculata [79]; Potato leaves [80] | |||

| 83 | Polyhydroxycarboxylic acid | Quinic acid | C7H12O6 | 7.9 | 191 | 111; 173 | 111 | L. japonica [26]; R. meyeri [37]; Andean blueberry [38]; Potato leaves [80] | ||

| 84 | Pentahydroxy hexanoic acid | Gluconic acid [Dextronic acid; Maltonic acid; Glycogenic acid; Pentahydroxy hexanoic acid] * | C6H12O7 | 19.1 | 197 | 188; 179; 156; 119 | 156; 148 | R. meyeri [37]; Colchicum micranthum [83] | ||

| 85 | Benzofuran | Loliolide * | C11H16O3 | 20.7 | 197 | 179; 127 | 111 | Jatropha [68] | ||

| 86 | Alpha, omega dicarboxylic acid | Sebacic acid [Decanedioic acid] * | C10H18O4 | 17.6 | 203 | 185 | 139 | 111; 157 | Jatropha [68] | |

| 87 | 4-Dihydroxy-3-methoxy-benzenepropanoic acid * | C10H12O5 | 25.7 | 213 | 193; 167; 139; 119 | Actinidia [70] | ||||

| 88 | Sesquiterpenoid | Caryophyllene oxide [Caryophyllene-alpha-oxide] * | C15H24O | 16.4 | 219 | 173; 111 | 111 | R. davurica [69]; Olive leaves [84] | ||

| 89 | Carboxylic acid | Myristoleic acid [Cis-9-Tetradecanoic acid] * | C14H26O2 | 20.2 | 227 | 209; 165 | 121 | F. glaucescens [22]; Maackia amurensis [85] | ||

| 90 | Pyrimidine nucleoside | Cytidine | C9H13N3O5 | 29.2 | 244 | 225; 179 | 179 | 151 | L. japonica [26] | |

| 91 | Glycosylated pyrimidine analog | Uridine | C9H12N2O6 | 28.3 | 245 | 145 | 117 | L. japonica [26]; Potato leaves [80] | ||

| 92 | Hydroxy tetradecanoic acid | Hydroxy myristic acid [2S-Hydroxytetradecanoic acid; Alpha-Hydroxy Myristic acid] * | C14H28O3 | 30.8 | 245 | 228 | 183 | F. pottsii [22] | ||

| 93 | Medium-chain fatty acid | Hydroxy dodecanoic acid * | C12H22O5 | 27.5 | 247 | 229; 201 | 187 | 159; 145 | F. glaucescens [22] | |

| 94 | Caffeic acid isoprenyl ester | C14H16O4 | 25.4 | 249 | 203 | 157 | 129 | Eucalyptus [66]; Brazilian propolis [86] | ||

| 95 | Sesquiterpene lactone | Artemisinin C * | C15H20O3 | 25.7 | 249 | 202; 157; 125 | 157; 185 | 129 | Artemisia annua [87] | |

| 96 | Aporphine alkaloid | Anonaine * | C17H15NO2 | 25.8 | 266 | 249 | 203 | 157 | R. rugosa [69]; Magnolia [88] | |

| 97 | Ribonucleoside composite of adenine (purine) | Adenosine | C10H13N5O4 | 20.2 | 268 | 250 | 204; 158 | 157 | L. japonica [26]; R. acicularis [69]; Huolisu Oral Liquid [89] | |

| 98 | 3,4,8,9,10-Penthahydroxydibenzo [b,d]pyran-6-one * | C13H8O7 | 33.3 | 277 | 203 | 157 | 129 | Terminalia arjuna [56] | ||

| 99 | Omega-3-fatty acid | Stearidonic acid [6,9,12,15-Octadecatetraenoic acid; Moroctic acid] * | C18H28O2 | 40.0 | 277 | 261 | 215; 115 | 129 | G. linguiforme [22]; Rhus coriaria [36]; Jatropha [68]; Salviae Miltiorrhizae [90] | |

| 100 | Omega-3-fatty acid | Linolenic acid (Alpha-Linolenic acid; Linolenate) * | C18H30O2 | 42.2 | 279 | 261 | 219 | 163 | Jatropha [68]; P. sylvestris [75]; Maackia amurensis [85]; Salviae Miltiorrhizae [90] | |

| 101 | Mixture of diastereomers | Fructose-leucine | C12H23NO7 | 7.8 | 294 | 276 | 258 | 210 | Potato leaves [80] | |

| 102 | Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | Coumaroyl shiikimic acid | C16H16O7 | 19.4 | 321 | 219; 173 | 201; 173 | 155 | Andean blueberry [38] | |

| 103 | Oxylipin | 13- Trihydroxy-Octadecenoic acid [THODE] * | C18H34O5 | 32.6 | 329 | 229; 171 | 210 | 209; 183 | Phoenix dactylifera [58]; Jatropha [68]; Broccoli [91] | |

| 104 | Alpha, omega-dicarboxylic acid | Eicosatetraenedioic acid * | C20H30O4 | 32.1 | 333 | 287; 197; 151 | 151 | G. linguiforme [22] | ||

| 105 | Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | Caffeoyl shikimic acid | C16H16O8 | 38.0 | 337 | 273; 173 | 128 | R. meyeri [37] | ||

| 106 | Alpha, omega-dicarboxylic acid | Trihydroxy eicosatetraenoic acid * | C20H32O5 | 45.6 | 353 | 261 | 243 | 159 | F. glaucescens [22] | |

| 107 | Dicarboxylic acid sugar | Caffeoyl gluconic acid | C15H18O10 | 21.6 | 359 | 340; 312; 284; 228; 196 | R. meyeri [37] | |||

| 108 | Iridoid glucoside | Sweroside | C16H22O9 | 21.6 | 359 | 197; 127 | 179 | 111 | L. japonica [26] | |

| 109 | Cyclopentapyran | Loganin acid | C16H24O10 | 18.9 | 377 | 158; 359 | 130 | L. japonica [26] | ||

| 110 | 7-(β-D-Galactopyranosyloxy)-6,8-dimethoxy-2H-1-benzopyran-2-one | C17H20O10 | 6.7 | 383 | 191 | 172; 127 | 171 | Actinidia [70] | ||

| 111 | Iridoid | Monotropein * | C16H22O11 | 31.2 | 391 | 373; 329; 251; 187 | 311; 202 | 203 | V. myrtillus [51,92] | |

| 112 | Sterol | Beta-Sitostenone [Stigmast-4-En-3-One; Sitostenone] * | C29H48O | 2.1 | 413 | 301; 171 | 189 | F. herrerae [22]; Terminalia laxiflora [93] | ||

| 113 | Anabolic steroid | Vebonol * | C30H44O3 | 24.9 | 453 | 435; 210 | 226; 336 | 210 | Rhus coriaria [36]; Hylosereus polyrhizus [82] | |

| 114 | Phenylpropanoid glucoside | Grayanoside A [Hydroxyphenylethyl feruloyl glucopyranoside] * | C24H28O10 | 23.4 | 475 | 375; 275 | 347; 275; 175 | 247; 175 | Strawberry [40] | |

| 115 | Thromboxane receptor antagonist | Vapiprost * | C30H39NO4 | 44.7 | 478 | 337 | 263; 121 | 119 | Rhus coriaria [36]; Hylosereus polyrhizus [82] | |

| 116 | Indole sesquiterpene alkaloid | Sespendole * | C33H45NO4 | 45.7 | 520 | 184 | 125 | Rhus coriaria [36] | ||

| 117 | Iridoid glucoside | p-Coumaroyl monotropein * | C25H28O13 | 44.6 | 537 | 375; 256; 185 | Cranberry [52]; V. myrtillus [49,51] | |||

| 118 | Iridoid glucoside | p-Coumaroyl-6,7-dihydromonotropein * | C25H30O13 | 20.2 | 540 | 373; 229; 179 | 179 | Cranberry [48]; V. myrtillus [51] | ||

| 119 | Carotenoid | Zeaxanthin [All-Trans-Zeaxanthin; Anchovyxanthin] | C40H56O2 | 28.4 | 570 | 552; 412; 184 | 534; 317; 184 | 487; 404; 321; 149 | Sarsaparilla [94]; Carotenoids [95] | |

| 120 | Carotenoid | (all-E)-lutein 3-O-C(4:0) | 41.8 | 638 | 620; 554 | 536; 335; 220 | 414; 276; 241 | Carotenoids [96] | ||

| 121 | Iridoid | p-Coumaroyl monotropein hexoside * | 42.5 | 699 | 537; 347; 259 | 375; 259; 185 | V. myrtillus [51] | |||

| 122 | Product of chlorophyll degradation | Pheophytin A | C55H74N4O5 | 0.6 | 872 | 593 | 533 | 461 | Physalis peruviana [97]; Capsicum [98] |

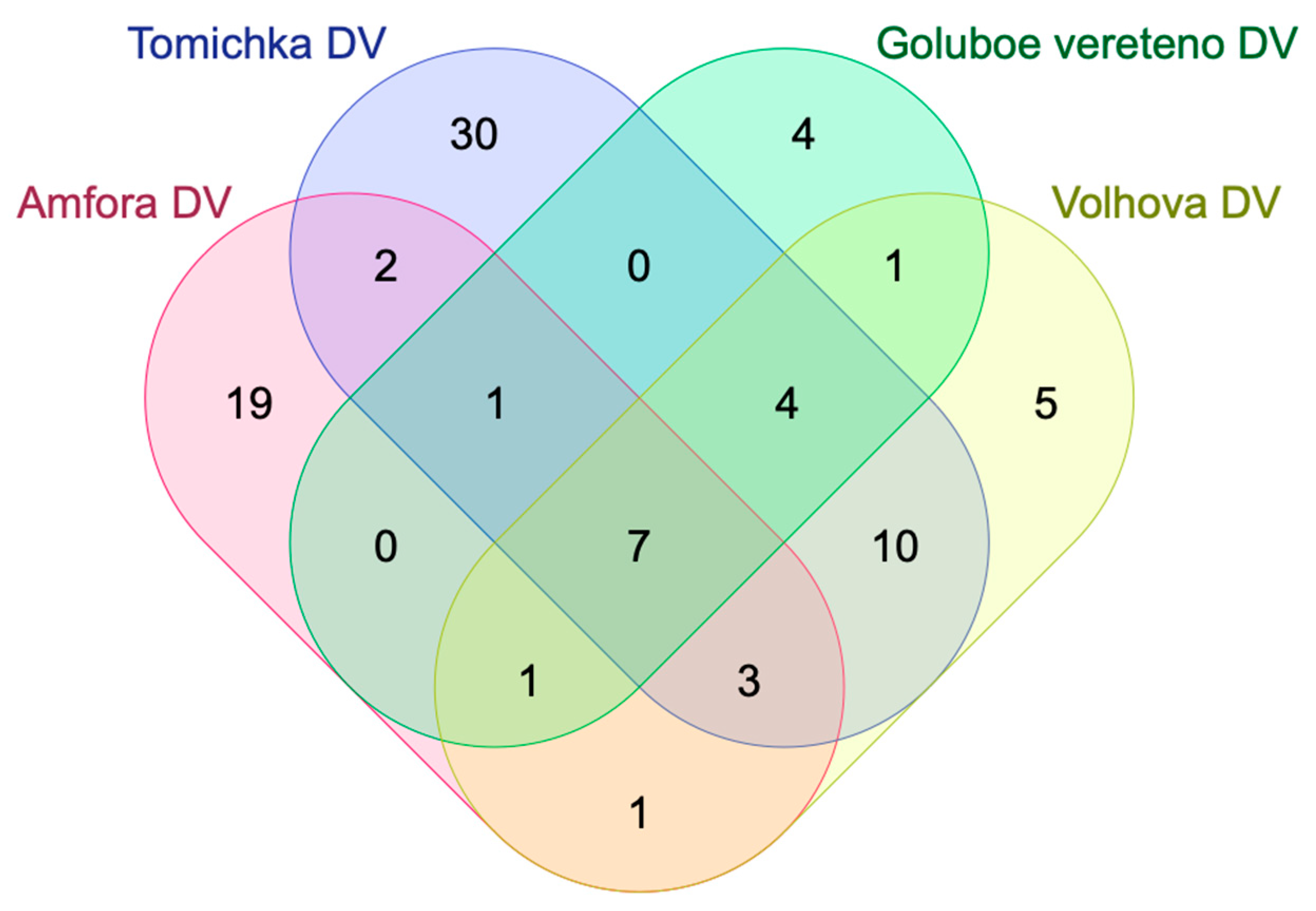

| Names | Total | Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Amfora; Goluboe vereteno; Tomichka; Volhova | 7 | kaempferol; herbacetin; 2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxybenzoic acid; caffeic acid isoprenyl ester; L-histidine; anonaine; 8,9,10-penthahydroxydibenzo [bd]pyran-6-one |

| Amfora; Goluboe vereteno; Tomichka | 1 | hydroxyferulic acid |

| Amfora; Tomichka; Volhova | 3 | quercetin; hydroxy dodecanoic acid; rhamnocitrin |

| Amfora; Goluboe vereteno; Volhova | 1 | jaceosidin |

| Goluboe vereteno; Tomichka; Volhova | 4 | pheophytin A; sebacic acid; fructose-leucine; myristoleic acid |

| Amfora; Tomichka | 2 | sespendole; fraxetin |

| Amfora; Volhova | 1 | stearidonic acid |

| Tomichka; Volhova | 10 | p-coumaroyl shiikimic acid; isorhamnetin 3-O-(6″-O-rhamnosyl-hexoside); p-coumaroyl malonyldihexose; isorhamnetin; ellagic acid; resveratrol; methylgallic acid; delphinidin 3-O-glucoside; hydroxy methoxy dimethylbenzoic acid; quinic acid |

| Goluboe vereteno; Volhova | 1 | (epi)-afzelechin derivative |

| Amfora | 19 | 4/6,8-dihydro-5,7-dihydroxy-2-oxo-2H-1-benzopyran-3-acetic acid; trihydroxyisoflavone; dimethylquercetin-3-O-dehexoside; chrysoeriol O-hexoside; 6-hydroxy-3-methoxy-4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside; formononetin-7-O-glucoside-6″-O-malonate; 13- trihydroxy-Octadecenoic acid; linolenic acid; cirsiliol; adenosine; pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside; citric acid; apigenin; gallocatechin; grayanoside A; pelargonidin 3-O-(6-O-malonyl-β-D-glucoside); C-hexosyl-apigenin O-rhamnoside; artemisinin C; vapiprost |

| Tomichka | 30 | rutin; 7-(β-D-glucopyranoside/galactopyranoside)-2-oxo-2H-1-benzopyran-4-acetic acid; umbelliferone; sinapic acid; vebonol; umbelliferone hexoside; lonicerin; (−)-epicatechin gallate; caffeic acid; L-arginine; quercetin 3-O-glucoside; ferulic acid; L-threanine; quercetin 3-O-pentosyl hexoside; p-coumaroyl-6,7-dihydromonotropein; p-coumaroylhexose-4-O-hexoside; 5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid; eicosatetraenedioic acid; uridine; delphinidin 3-O-β-D-sambubioside; chlorogenic acid; delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside; caffeoyl gluconic acid; caffeoylquinic acid derivative; cytidine; naringenin; petunidin-3-rutinoside; dicaffeoylferuoylquinic acid; kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside; zeaxanthin; pentahydroxy dimethoxyflavone |

| Goluboe vereteno | 4 | caffeoyl shikimic acid; calycosin-7-O-β-D-glucoside-6″-O-malonate; pinosylvin; dihydroxy-tetramethoxy(iso)flavone |

| Volhova | 5 | trihydroxy eicosatetraenoic acid; 4-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid; derivative of quercetin rhamnosyl hexoside; monotropein; butin |

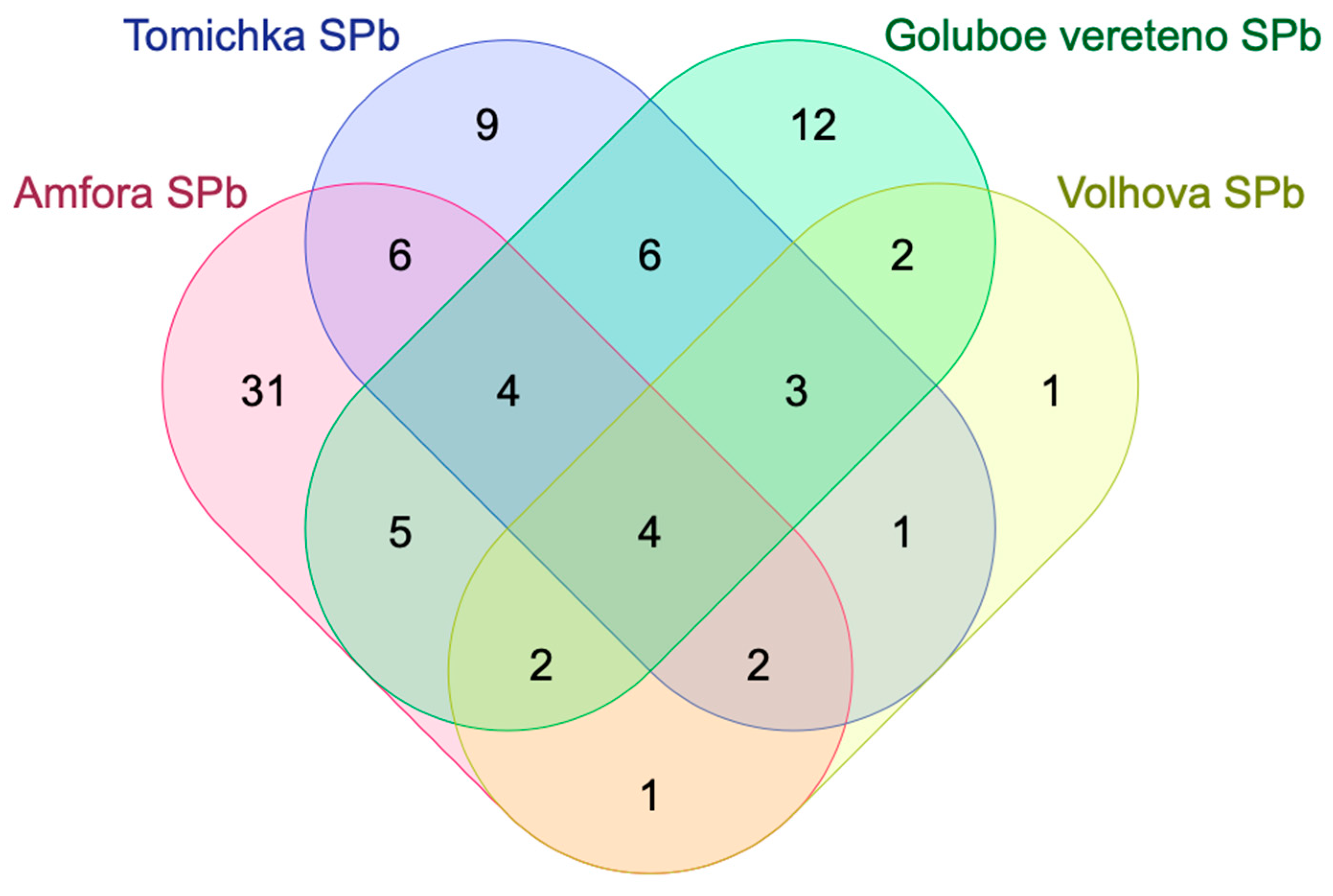

| Names | Total | Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Amfora SPb Goluboe vereteno SPb Tomichka SPb Volhova SPb | 4 | (epi)-afzelechin derivative; L-histidine; anonaine; myristoleic acid |

| Amfora SPb Goluboe vereteno SPb Tomichka SPb | 4 | petunidin; sebacic acid; apigenin; pentahydroxy dimethoxyflavone |

| Amfora SPb Tomichka SPb Volhova SPb | 2 | isorhamnetin; ellagic acid |

| Amfora SPb Goluboe vereteno SPb Volhova SPb | 2 | caffeic acid isoprenyl ester; quercetin |

| Goluboe vereteno SPb Tomichka SPb Volhova SPb | 3 | herbacetin; (epi)-afzelechin; (epi)-catechin |

| Amfora SPb Tomichka SPb | 6 | 7-(β-D-glucopyranoside/galactopyranoside)-2-oxo-2H-1-benzopyran-4-acetic acid; shikimic acid; cirsiliol; methylgallic acid; hydroxy dodecanoic acid; dihydroxy-tetramethoxy(iso)flavone |

| Amfora SPb Goluboe vereteno SPb | 5 | p-coumaroyl monotropein hexoside; resveratrol; fructose-leucine; quinic acid; artemisinin C |

| Amfora SPb Volhova SPb | 1 | 5,6,4′-trihydroxy-7,8-dimethoxyflavone |

| Goluboe vereteno SPb Tomichka SPb | 6 | 2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxybenzoic acid; sespendole; linolenic acid; gallocatechin; 6-trihydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid; 4-dihydroxy-3-methoxy-benzenepropanoic acid |

| Tomichka SPb Volhova SPb | 1 | 8,9,10-penthahydroxydibenzo [b d]pyran-6-one |

| Goluboe vereteno SPb Volhova SPb | 2 | citric acid; hydroxy methoxy dimethylbenzoic acid |

| Amfora SPb | 31 | coumaroyl shiikimic acid; loganin acid; isorhamnetin 3-O-(6″-O-rhamnosyl-hexoside); 2,4,6-trihydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid; lonicerin; p-coumaroyl malonyldihexose; caryophyllene oxide; L-pyroglutamic acid; 3,8,9,10-penthahydroxydibenzo [bd]pyran-6-one; hydroxyferulic acid; caffeic acid; L-arginine; 3-O-hydroxydihydrocaffeoylquinic acid; quercetin 3-O-glucoside; pheophytin A; L-proline; eicosatetraenedioic acid; rhamnetin II; rhamnocitrin; loliolide; 7-(β-D-galactopyranosyloxy)-6,8-dimethoxy-2H-1-benzopyran-2-one; p-coumaroyl-6,7-dihydromonotropein; delphinidin 3-O-β-D-sambubioside; chlorogenic acid; delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside; kaempferol-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside; caffeoyl gluconic acid; pinosylvin; caffeoylquinic acid derivative; dihydroresveratrol; sweroside; luteolin 7-O-(6-O-arabinosyl-glucoside) |

| Tomichka SPb | 9 | trihydroxy eicosatetraenoic acid; dimethylquercetin-3-O-dehexoside; sophoraisoflavone A; (all-E)-lutein 3-O-C(4:0); dihydrokaempferol; hydroxy myristic acid; jaceosidin; luteolin 7-O-glucoside; naringenin |

| Goluboe vereteno SPb | 12 | acacetin 8-C-glucoside malonylated; gluconic acid; kaempferol; stearidonic acid; β-Sitostenone; p-coumaroyl monotropein; anthocyanidin; adenosine; (epi)-catechin derivative; protocatechuic acid; calycosin-7-O-β-D-glucoside-6″-O-malonate; chrysin derivative |

| Volhova SPb | 1 | 2,3,4,6-pentahydroxybenzoic acid |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Razgonova, M.P.; Navaz, M.A.; Sabitov, A.S.; Zinchenko, Y.N.; Rusakova, E.A.; Petrusha, E.N.; Golokhvast, K.S.; Tikhonova, N.G. The Global Metabolome Profiles of Four Varieties of Lonicera caerulea, Established via Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9111188

Razgonova MP, Navaz MA, Sabitov AS, Zinchenko YN, Rusakova EA, Petrusha EN, Golokhvast KS, Tikhonova NG. The Global Metabolome Profiles of Four Varieties of Lonicera caerulea, Established via Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Horticulturae. 2023; 9(11):1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9111188

Chicago/Turabian StyleRazgonova, Mayya P., Muhammad Amjad Navaz, Andrey S. Sabitov, Yulia N. Zinchenko, Elena A. Rusakova, Elena N. Petrusha, Kirill S. Golokhvast, and Nadezhda G. Tikhonova. 2023. "The Global Metabolome Profiles of Four Varieties of Lonicera caerulea, Established via Tandem Mass Spectrometry" Horticulturae 9, no. 11: 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9111188

APA StyleRazgonova, M. P., Navaz, M. A., Sabitov, A. S., Zinchenko, Y. N., Rusakova, E. A., Petrusha, E. N., Golokhvast, K. S., & Tikhonova, N. G. (2023). The Global Metabolome Profiles of Four Varieties of Lonicera caerulea, Established via Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Horticulturae, 9(11), 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9111188