Mitigation of Powdery Mildew Disease by Integrating Biocontrol Agents and Shikimic Acid with Modulation of Antioxidant Defense System, Anatomical Characterization, and Improvement of Squash Plant Productivity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Tested Compounds

2.2. Biocontrol Agents (BCAs) Preparation

2.3. Identification and Inoculation of P. xanthii

2.4. Seed Priming Preparation

2.5. Pot Experiments

2.6. Greenhouse Experiments

2.7. Data Recorded

2.7.1. Disease Assessment

2.7.2. Vegetative Growth

2.7.3. Yield and Its Components

2.7.4. Mineral Content in Squash Leaves

2.7.5. Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes, Salicylic Acid and Jasmonic Acid

2.7.6. GG/MS Analysis of T. asperellum Culture Filtrate

2.7.7. Anatomical Studies

- -

- Thickness of midvein (µm)

- -

- Thickness of upper periderm (µm)

- -

- Thickness of lower periderm (µm)

- -

- Thickness of lamina (µm)

- -

- Thickness of palisade tissue (µm)

- -

- Thickness of spongy tissue (µm)

- -

- Dimension of main midvein bundle (µm)

- -

- No of xylem rows in main midvein bundle

- -

- Mean diameter of vessels (µm)

- -

- Mean diameter of parenchyma cells in the ground tissue (µm)

2.7.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pot Experiments

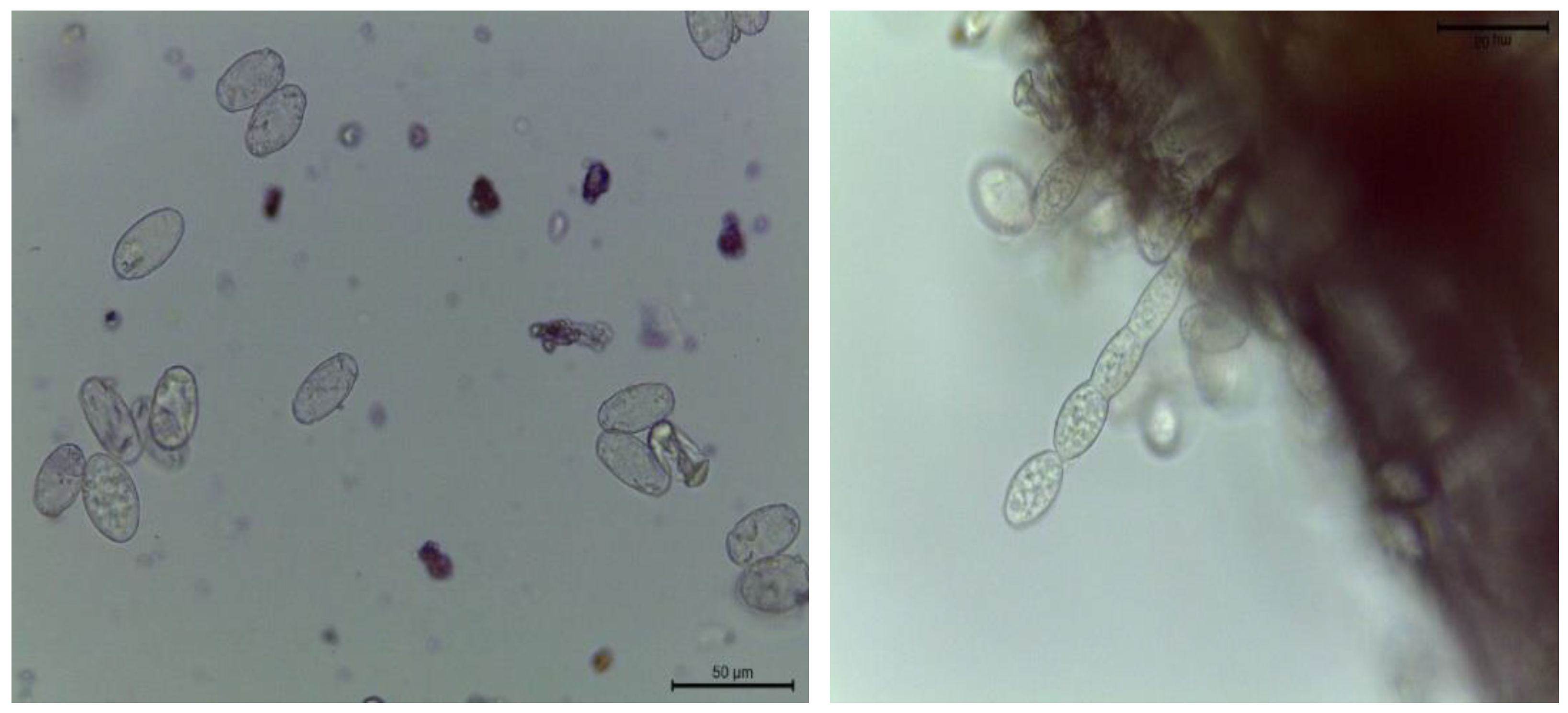

3.1.1. Morphology of P. xanthii

3.1.2. Disease Assessment

3.1.3. Plant Growth Parameters of Squash Plants

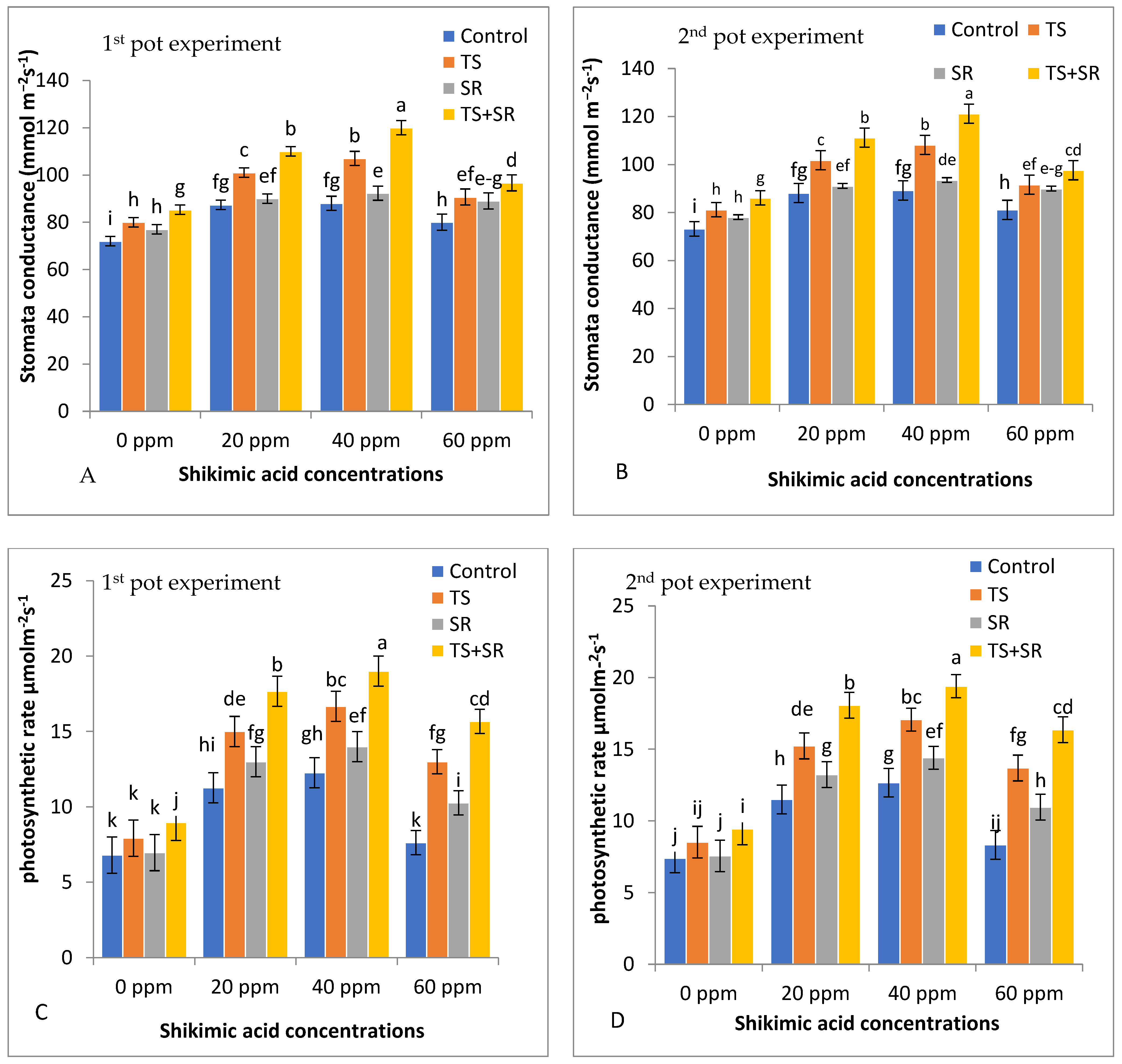

3.1.4. Physiological Traits of Squash Plants

3.2. Greenhouse Experiments

3.2.1. Disease Assessment

3.2.2. Plant Growth

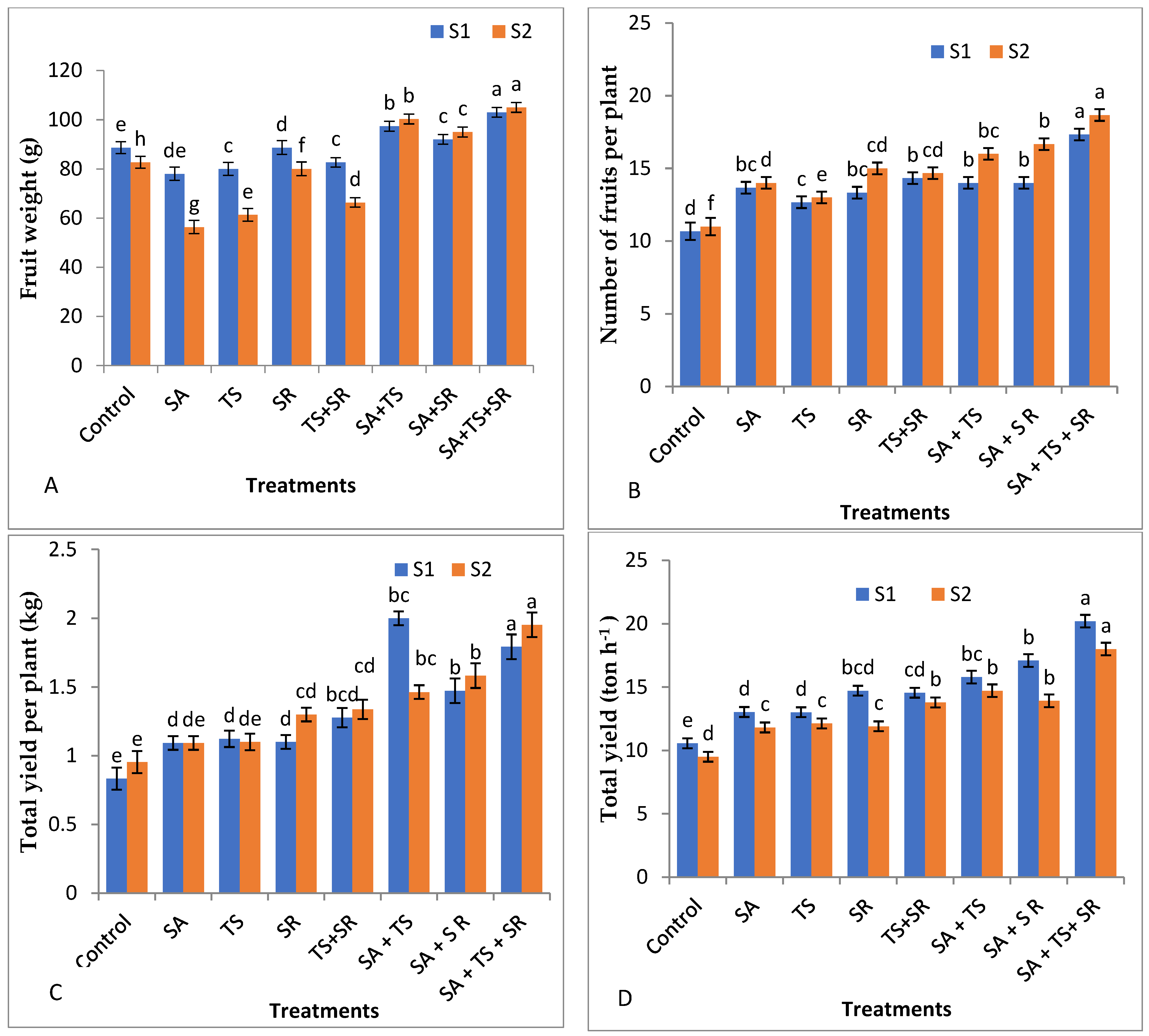

3.2.3. Yield and Its Components

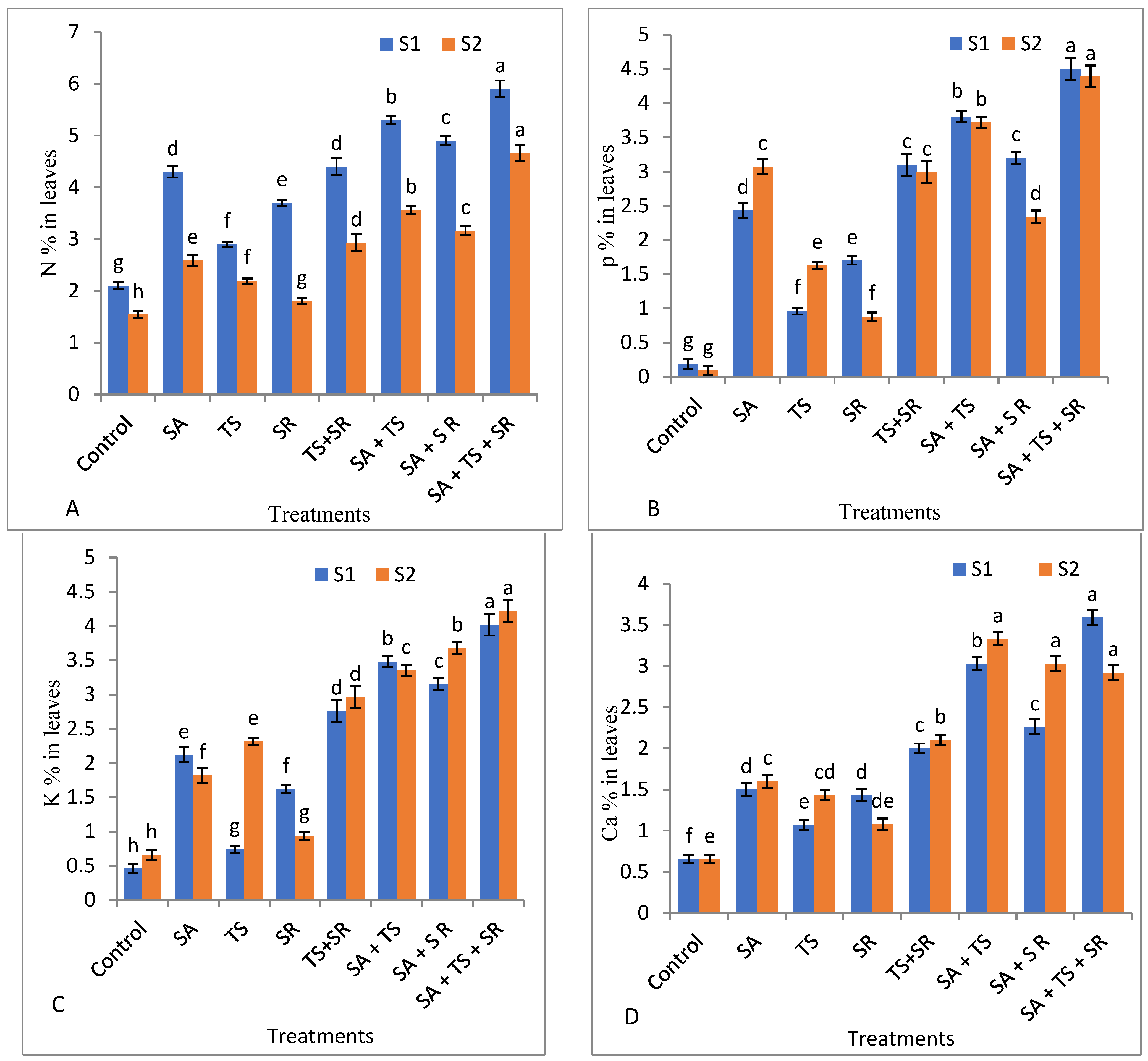

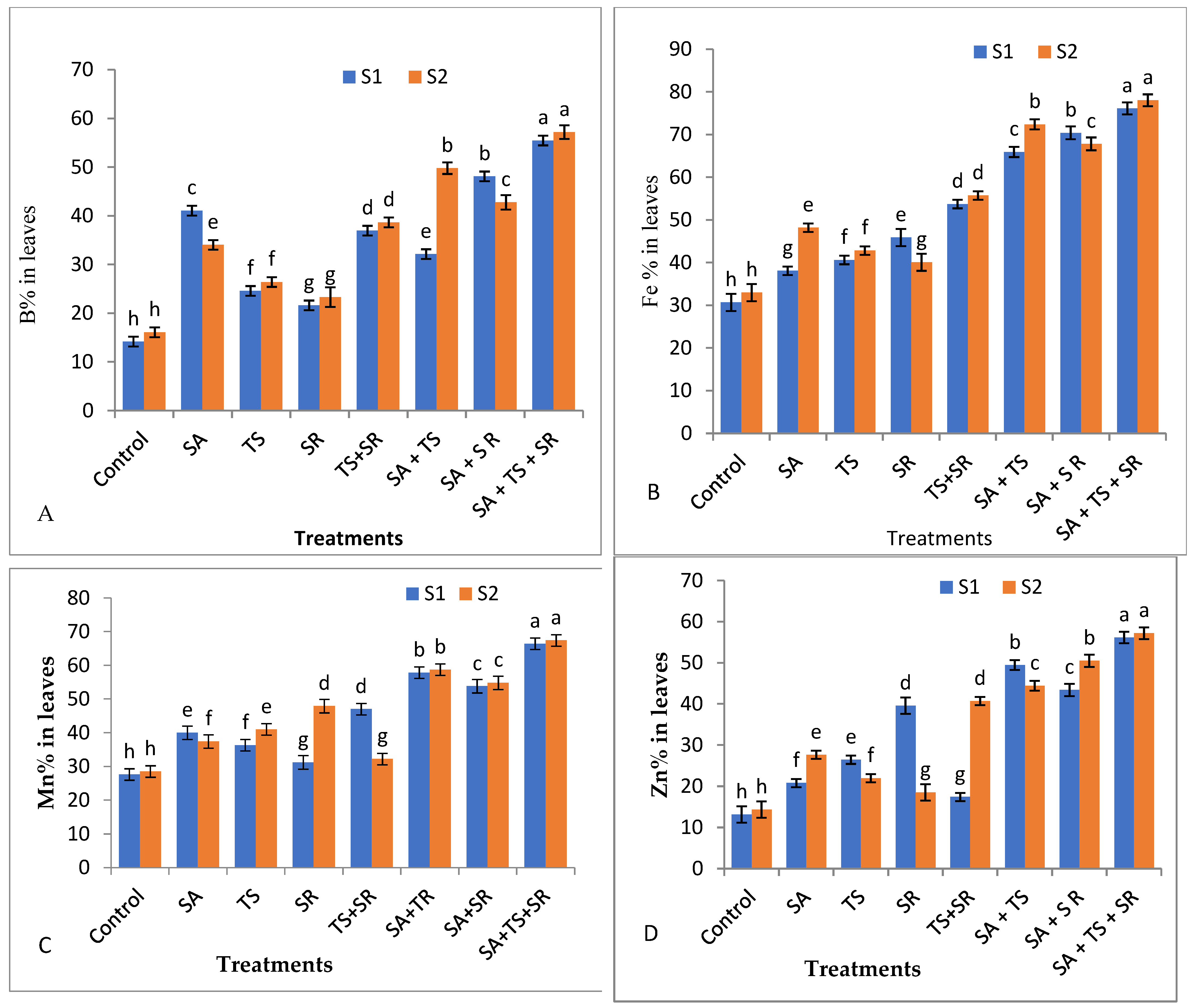

3.2.4. Mineral Content in Squash Leaves

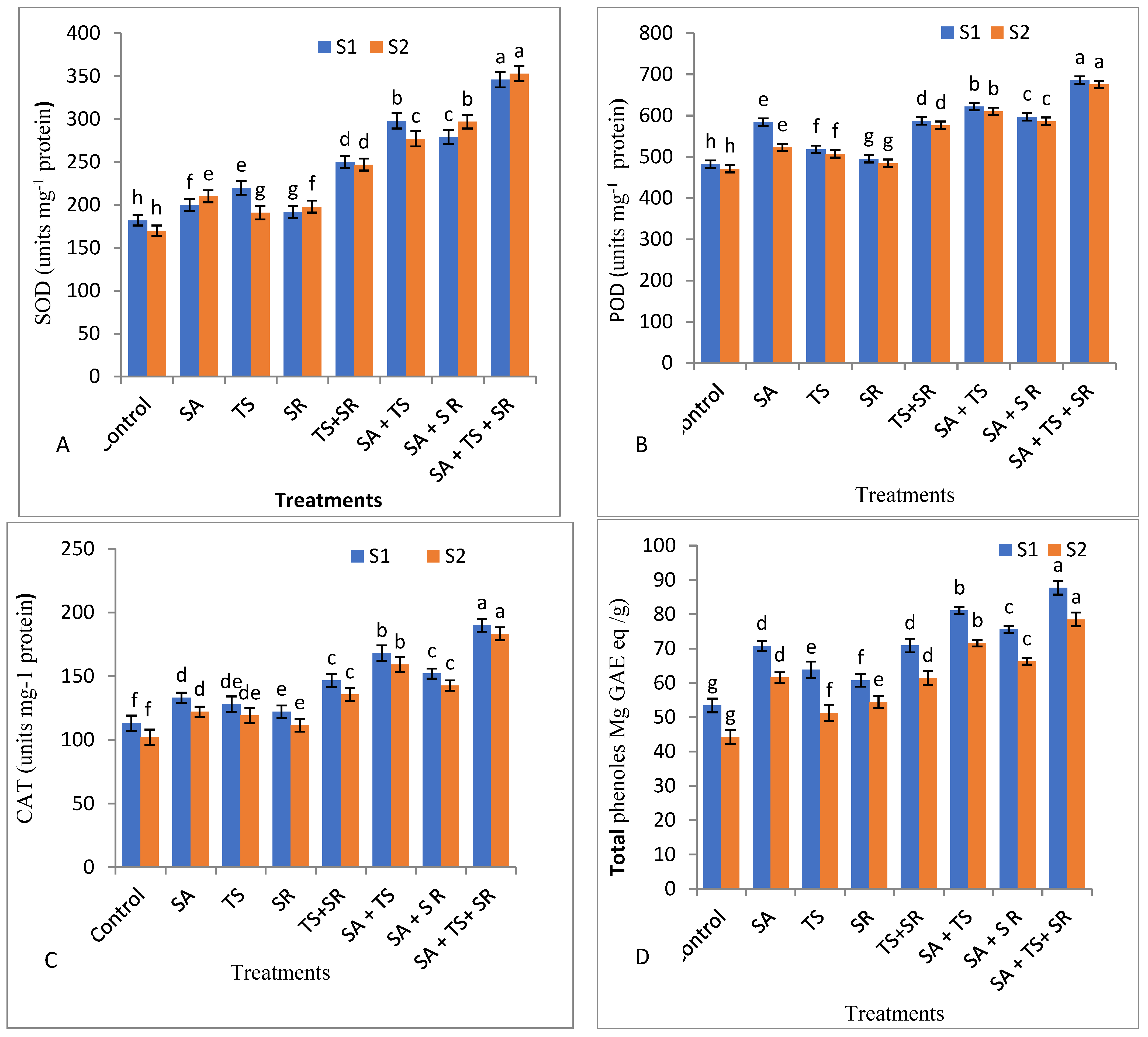

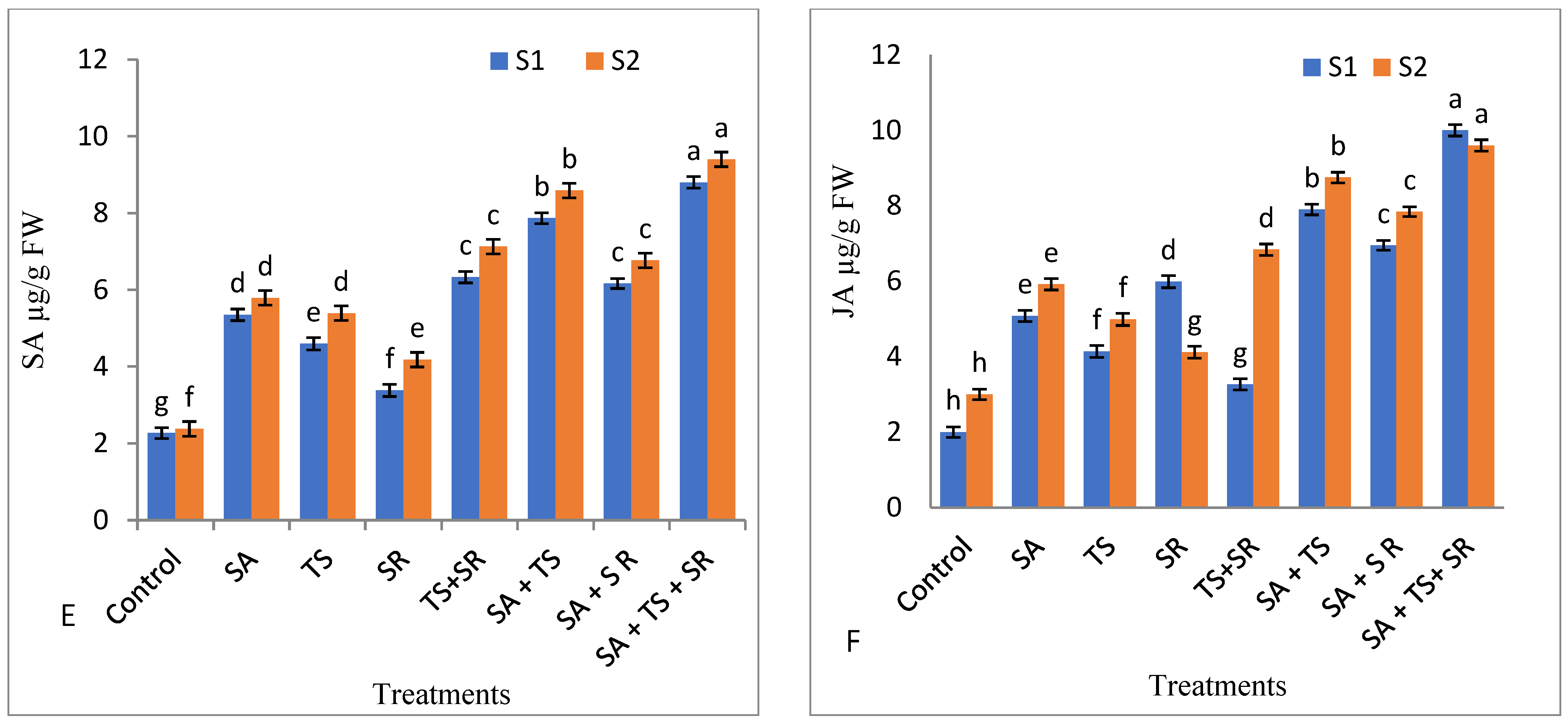

3.2.5. Antioxidant Enzymes, Total Phenols, and Plant Hormones in Squash Leaves

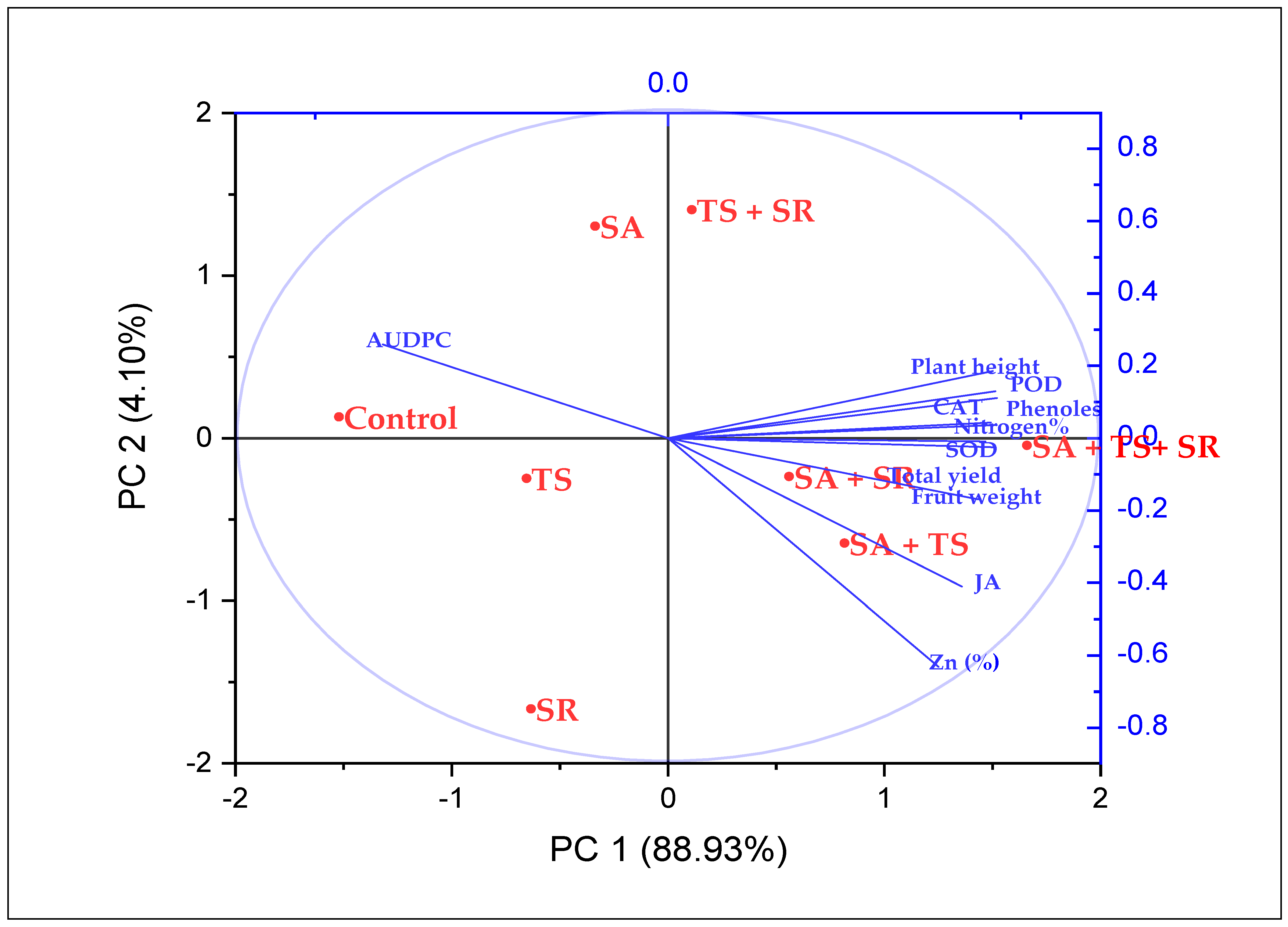

3.3. Clustering Analysis

3.4. Trait Interrelationships

3.5. GG/MS Analysis of T. asperellum Culture Filtrate

3.6. Leaf Anatomy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abd El-All, H.M.; Ali, S.M.; Shahin, S.M. Improvement growth, yield and quality of squash (Cucurbita pepo L.) plant under salinity conditions by magnetized water, amino acids and selenium. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2013, 9, 937–944. [Google Scholar]

- El-Naggar, M.; El-Deeb, H.; Ragab, S. Applied approach for controlling powdery mildew disease of cucumber under plastic houses. Pak. J. Agric. 2012, 28, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, Y.M.; Bayoumi, Y.A.; Pap, Z.; Kappel, N. Role of hydrogen peroxide and Pharmaplant-turbo against cucumber powdery mildew fungus under organic and inorganic production. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. 2008, 14, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Monaim, M.; Abdel-Gaid, M.; Armanious, H. Effect of chemical inducers on root rot and wilt diseases, yield and quality of tomato. Int. J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 7, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Deore, P.B.; Sawant, D.M. Management of guar powdery mildew by Trichoderma spp. culture filtrates. J. Maharashtra Agric. Univ. 2001, 25, 253–254. [Google Scholar]

- Guigón López, C.; Muñoz Castellanos, L.N.; Flores Ortiz, N.A.; Judith Adriana, G.G. Control of powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica) using Trichoderma asperellum and Metarhizium anisopliae in different pepper types. BioControl 2019, 64, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oszako, T.; Voitka, D.; Stocki, M.; Stocka, N.; Nowakowska, J.; Linkiewicz, A.; Hsiang, T.; Belbahri, L.; Daria Berezovska, D.; Malewski, T. Trichoderma asperellum efficiently protects Quercus robur leaves against Erysiphe alphitoides. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 159, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyskiewicz, R.; Nowak, A.; Ozimek, E.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J. Trichoderma: The Current Status of Its Application in Agriculture for the Biocontrol of Fungal Phytopathogens and Stimulation of Plant Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacios-Michelena, S.; Aguilar González, C.N.; Alvarez-Perez, O.B.; Rodriguez-Herrera, R.; Chávez-González, M.; Arredondo Valdés, R.; Ascacio Valdés, J.A.; Govea Salas, M.; Ilyina, A. Application of Streptomyces Antimicrobial Compounds for the Control of Phytopathogens. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 696518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, F.; Mailänder, S.; Bönn, M.; Feldhahn, L.; Herrmann, S.; Große, I.; Buscot, F.; Schrey, S.D.; Tarkka, M.T. Streptomyces-induced resistance against oak powdery mildew involves host plant responses in defense, photosynthesis, and secondary metabolism pathways. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2014, 27, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Wei, Q.; Shi, L.; Wei, Z.; Lv, Z.; Asim, N.; Zhang, K.; Ge, B. Wuyiencin produced by Streptomyces albulus CK-15 displays biocontrol activities against cucumber powdery mildew. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 2957–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrandt, T.M.; Nunes Nesi, A.; Araujo, W.L.; Braun, H.P. Amino Acid Catabolism in Plants. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1563–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, E.G.; Mahmoud, A.W.M.; Abdel-Wahab, A.; Elbahbohy, R.M. Rootstock Priming with Shikimic Acid and Streptomyces griseus for Growth, Productivity, Physio-Biochemical, and Anatomical Characterisation of Tomato Grown under Cold Stress. Plants 2022, 11, 2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangl, J.; Jones, J. Plant pathogens and integrated defense responses to infection. Nature 2001, 411, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, B.; Zhou, J. Differential Responses of Cucurbita pepo to Podosphaera xanthii Reveal the Mechanism of Powdery Mildew Disease Resistance in Pumpkin. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 633221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, L.; Wang, L.N.; Wu, X.L.; Gao, W.; Zhang, J.X.; Huang, C.Y. Expression patterns of two Pal genes of Pleurotus ostreatus across developmental stages and under heat stress. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Li, J.; Jin, P.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Y. The effect of temperature on phenolic content in wounded carrots. Food Chem. 2017, 215, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.H.; Cao, Y.; Lin, X.G.; Leng, Q.Y.; Chen, Y.M.; Yin, J.M. Field and laboratory screening of anthurium cultivars for resistance to foliar bacterial blight and the induced activities of defense-related enzymes. Folia Hortic. 2018, 30, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Van der Does, D.; Zamioudis, C.; Leon-Reyes, A.; Van Wees, S.C.M. Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012, 28, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Abd EL-Kader, A.E.S.; Ghoneemi, K.H.M. Two Trichoderma species and Bacillus subtilis as biocontrol agents against Rhizoctonia disease and their influenceon potato productivity. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 95, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gebily, D.A.S.; Ghanem, G.A.M.; Ragab, M.M.; Ali, A.M.; Soliman, N.E.K.; Abd El-Moity, T.H. Characterization and potential antifungal activities of three Streptomyces spp. As biocontrol agents against Sclerotinia sclerotium (Lib.) de Bary infecting green bean. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2021, 31, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.D. Erysiphaceae of Korea; National Institute of Agricultural Science and Technology: Suwon, Korea, 2000; pp. 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Margaritopoulou, T.; Toufexi, E.; Kizis, D. Reynoutria sachalinensis extract elicits SA-dependent defense responses in courgette genotypes against powdery mildew caused by Podosphaera xanthii. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, M.; Sugiyama, K.; Saito, T.; Sakata, Y. Powdery mildew resistance in cucumber. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 2003, 37, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.N.; Menon, T.C.M.; Rao, M.V. Asimple formula for calculating area under disease progress curve. Rachis 1989, 8, 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Helrich, K. Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Agricultural Chemist: Arlington, VA, USA, 1990; Volume 1, p. 673. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.L. Soil Chemical Analysis; Text Book; Printice-Hall of India: New Delhi, India; Privat Limited: New Delhi, India, 1973; pp. 144–197, 381. [Google Scholar]

- Mur, L.; Kenton, P.; Atzorn, R.; Miersch, O.; Wasternack, C. The Outcomes of Concentration-Specific Interactions between Salicylate and Jasmonate Signaling Include Synergy, Antagonism, and Oxidative Stress Leading to Cell Death. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmeyer, H.U. Methods of Enzymatic Analysis, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Kareem, M.S.M.; Rabbih, M.A.; Selim, E.T.M.; Elsherbiny, A.E.; El-Khateeb, A.Y. Application of GC/EIMS in combination with semi-empirical calculations for identification and investigation of some volatile components in basil essential oil. Int. J. Anal. Mass Spectrom. Chromatogr. 2016, 4, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, I.A.; Guma, A.N. Anatomical diversity among certain genera of Family Cucurbitaceae. Int. J. Res. Stud. Biosci. 2015, 3, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker, B. MSTATC: A Micro Computer Program from the Design Management and Analysis of Agronomic Research Experiments; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor, G.W.; Cochran, W.G. Statistical Methods, 7th ed.; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1980; p. 507. [Google Scholar]

- Marra, R.; Lombardi, N.; d’Errico, G.; Troisi, J.; Scala, G.; Vinale, F. Application of Trichoderma strains and metabolites enhances soybean productivity and nutrient content. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinale, F.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Ghisalberti, E.L.; Woo, S.L.; Nigro, M.; Marra, R.; Lombardi, N.; Pascale, A.; Ruocco, M.; Lanzuise, S.; et al. Trichoderma secondary metabolites active on plants and fungal pathogens. Open Mycol. J. 2014, 8 (Suppl. 1), 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carná, M.; Repka, V.; Skůpa, P.; Šturdík, E. Auxins in defense strategies. Biologia 2014, 69, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everse, J.; Hsia, N. The toxicities of native and modified hemoglobins. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1997, 22, 1075–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogovin, V.V.; Piruzyan, L.A.; Murav’ev, R.A. Peroksidazosomy (Peroxysomes); Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem, G.A.M.; Gebily, D.A.S.; Ragab, M.M.; Ali, A.M.; Soliman, N.E.K.; Abd El-Moity, T.H. Efficacy of antifungal substances of three Streptomyces spp. against different plant pathogenic fungi. Journal of Biological Pest Control. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2022, 32, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avis, T.J.; Bélanger, R.R. Mechanisms and means of detection of biocontrol activity of Pseudozyma yeasts against plant-pathogenic fungi. FEMS Yeast Res. 2002, 2, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astiko, W.; Muthahanas, I. Biological Control Techniques for Chili Plant Diseaseby Using Streptomyces sp. and Trichoderma sp. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2019, 4, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Aldesuquy, H.S.; Ibrahim, H.A. The role of shikimic acid in regulation of growth, transpiration, pigmentation, photosynthetic activity and productivity of Vigna sinensis plants. Phyton 2000, 40, 277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.R.; Rizvi, T.F. Effect of elevated levels of CO2 on powdery mildew development in five cucurbit species. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, G.C.; Fraser, G.A. The influence of powdery mildew infection on photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence, leaf chlorophyll and carotenoid content of three woody plant species. Arboric. J. 2002, 26, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, D. Effects of Rising Atmospheric Concentrations of Carbon Dioxide on Plants. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2010, 3, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Amaresh, C.; Bhatt, R.K. Biochemical and physiological response to salicylic acid in reaction to systemic acquired resistance. Photosynthetica 1998, 35, 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Yedidia, I.; Srivastva, A.K.; Kapulnik, Y.; Chet, I. Effect of Trichoderma harzianum on microelement concentrations and increased growth of cucumber plants. Plant Soil 2001, 235, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.N.; Abdelgawad, K.F. Potassium Silicate and Amino Acids Improve Growth, Flowering and Productivity of Summer Squash under High Temperature Condition. Am. Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2019, 19, 74–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, J.A.J.; Olivares, F.L. Plant growth promotion by streptomycetes: Ecophysiology, mechanisms and applications. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2016, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saja, D.; Janeczko, A.; Barna, B.; Skoczowski, A.; Dziurka, M.; Kornaś, A.; Gullner, G. Powdery Mildew-Induced Hormonal and Photosynthetic Changes in Barley Near Isogenic Lines Carrying Various Resistant Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratyusha, S. Phenolic Compounds in the Plant Development and Defense: An Overview. In Plant Stress Physiology—Perspectives in Agriculture; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsisi, A.A. Evaluation of biological control agents for managing squash powdery mildew under greenhouse conditions. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2019, 29, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, H.; Lin, Y.; Shi, J.; Xue, S.; Hung, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H. Effects of biocontrol bacteria Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LY-1 culture broth on qualityattributes and storability of harvested litchi fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 132, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, L.; Deng, J. Biocontrol ability and action mechanism of Bacillus halotolerans against Botrytis cinerea causing grey mould in postharvest strawberry fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 174, 111456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Salh, P.K.; Singh, B. Role of defense enzymes and phenolics in resistance of wheat crop (Triticum aestivum L.) towards aphid complex. J. Plant Interact. 2017, 12, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.-J.; Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of Catalase in Oxidative Stress- and Age-Associated Degenerative Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9613090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, Y.M.; El-Nagar, A.S.; Elzaawely, A.A.; Kamel, S.; Maswada, H.F. Biological control of Podosphaeraxanthii the causal agent of squash powdery mildew disease by upregulation of defense-related enzymes. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2018, 28, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.T.; Larkin, R.P. Efficacy of several potential biocontrol organisms against Rhizoctonia solani on potato. Crop Prot. 2005, 24, 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezziyyani, M.; Requena, M.E.; Gilabert, C.E.; Candela, M.E. Biological control of phytophthora root rot of pepper using Trichoderma harzianum and Streptomyces rochei in combination. J. Phytopathol. 2007, 155, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Shikimic Acid Concentrations | Bioagents Treatments | 1st Experiment | 2nd Experiment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Severity % | Reduction % | Disease Severity % | Reduction % | ||

| 0 ppm | Control | 37.04 a | - | 36.30 a | - |

| T. asperellum | 30.37 cd | 18.01 | 30.37 bc | 16.34 | |

| S. rochei | 31.85 bc | 14.01 | 32.59 ab | 10.22 | |

| T. asperellum +S. rochei | 28.89 c–e | 22.00 | 25.9 c–e | 28.57 | |

| 20 ppm | Control | 28.15 c–e | 24.00 | 24.44 d–f | 32.67 |

| T. asperellum | 23.70 fg | 36.02 | 22.22 e–g | 38.75 | |

| S. rochei | 26.67 d–f | 28.00 | 22.96 e–g | 36.75 | |

| T. asperellum +S. rochei | 20.74 g | 44.01 | 19.26 gh | 46.94 | |

| 40 ppm | Control | 28.15 c–e | 24.00 | 24.44 d–f | 32.67 |

| T. asperellum | 22.96 fg | 38.01 | 19.26 gh | 46.94 | |

| S. rochei | 23.70 fg | 36.02 | 21.48 e–g | 40.83 | |

| T. asperellum +S. rochei | 20.00 g | 46.00 | 16.30 h | 55.10 | |

| 60 ppm | Control | 34.82 ab | 05.99 | 30.37 bc | 16.34 |

| T. asperellum | 25.93 ef | 29.99 | 22.22 e–g | 38.79 | |

| S. rochei | 29.63 c–e | 20.01 | 28.15 b–d | 22.45 | |

| T. asperellum +S. rochei | 22.96 fg | 38.01 | 20.74 f–h | 42.87 | |

| LSD value at 0.05: | 4.17 | - | 4.47 | - | |

| Shikimic Acid Concentrations | Bioagents Treatments | Plant Height (cm) | Leaves Numbe per Plant | Chlorophyll (SPAD) Reading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ppm | Control | 22.73 j | 9.433 i | 21.73 g |

| T. asperellum | 47.73 d–g | 12.77 f–h | 25.10 ef | |

| S. rochei | 38.40 hi | 11.43 h | 25.23 ef | |

| T. asperellum +S. rochei | 51.07 cde | 13.50 fg | 35.60 c | |

| 20 ppm | Control | 44.33 f–h | 11.20 h | 27.00 e |

| T. asperellum | 54.33 b–d | 13.87 f | 35.03 c | |

| S. rochei | 47.00 e–g | 11.87 gh | 35.57 c | |

| T. asperellum +S. rochei | 61.0 b | 16.87 de | 46.00 b | |

| 40 ppm | Control | 50.33 c–f | 16.87 de | 30.73 d |

| T. asperellum | 59.33 b | 20.20 b | 46.23 b | |

| S. rochei | 50.00 c–f | 17.87 cd | 45.23 b | |

| T. asperellum +S. rochei | 69.00 a | 23.20 a | 57.10 a | |

| 60 ppm | Control | 35.60 i | 13.87 f | 23.73 fg |

| T. asperellum | 49.00 d–f | 17.87 cd | 27.10 e | |

| S. rochei | 42.00 g–i | 16.20 e | 25.90 ef | |

| T. asperellum +S. rochei | 56.33 bc | 18.53 c | 36.23 c | |

| LSD value at 0.05: | 6.7 | 1.646 | 2.6 | |

| Shikimic Acid Concentrations | Bioagents Treatments | Plant Height (cm) | Leaves Number per Plant | Chlorophyll (SPAD) Reading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ppm | Control | 27.33 h | 9.33 i | 21.4 i |

| T. asperellum | 35.33 fg | 12.67 gh | 24.43 gh | |

| S. rochei | 31.33 gh | 11.33 h | 26.23 fg | |

| T.asperellum+S. rochei | 46.00 cde | 14.00 fg | 35.87 d | |

| 20 ppm | Control | 43.0 de | 14.67 f | 27.40 ef |

| T. asperellum | 51.67 c | 18.67 cd | 34.90 d | |

| S. rochei | 46.0 cde | 17.00 e | 37.23 d | |

| T.asperellum+S. rochei | 60.0 b | 19.33 c | 47.43 b | |

| 40 ppm | Control | 49.00 cd | 17.67 de | 29.07 e |

| T. asperellum | 58.0 b | 21.00 b | 44.23 c | |

| S. rochei | 48.67 cd | 18.67 cd | 43.23 c | |

| T.asperellum+S. rochei | 67.67 a | 24.00 a | 55.10 a | |

| 60 ppm | Control | 30.67 gh | 12.00 h | 22.07 hi |

| T. asperellum | 45.67 cde | 14.67 f | 25.43 fg | |

| S. rochei | 40.00 ef | 12.67 gh | 27.23 ef | |

| T.asperellum+S. rochei | 59.0 b | 17.67 de | 36.10 d | |

| LSD value at 0.05: | 6.0 | 1.6 | 2.58 | |

| Treatment | FDL % | Reduction % | AUDPC | Reduction % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First season | ||||

| control | 59.44 a | - | 871.11 a | - |

| SA | 49.44 b | 16.82 | 672.78 b | 22.77 |

| SR | 47.78 bc | 19.62 | 614.44 bc | 29.46 |

| SA + SR | 46.11 b–d | 22.43 | 523.06 cd | 39.95 |

| TS | 43.89 c–e | 26.16 | 507.50 de | 41.74 |

| SA + TS | 43.33 de | 27.10 | 484.17 de | 44.42 |

| SR + TS | 41.11 ef | 30.84 | 455.00 de | 47.77 |

| SA + SR + TS | 37.22 f | 37.38 | 421.94 e | 51.56 |

| LSD.05 | 4.23 | - | 92.85 | - |

| Second season | ||||

| control | 77.78 a | - | 1165.28 a | - |

| SA | 71.67 b | 7.86 | 1071.94 ab | 8.00 |

| SR | 67.78 bc | 12.86 | 974.72 bc | 16.35 |

| SA + SR | 63.33 cd | 18.58 | 869.72 cd | 25.36 |

| TS | 61.11 de | 21.43 | 801.67 de | 31.20 |

| SA + TS | 59.44 de | 23.58 | 718.06 ef | 38.37 |

| SR + TS | 57.78 e | 25.71 | 688.89 f | 40.88 |

| SA + SR + TS | 52.78 f | 32.14 | 632.50 f | 45.72 |

| LSD.05 | 4.92 | - | 106.58 | - |

| Treatment | Plant Hight (cm) | Leaves Number/ Plant | Plant Fresh Weight (gm) | Plant Dry Weight (gm) | Chlorophyll (SPAD) Reading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 season | |||||

| Control | 44.0 g | 12.0 f | 155.7 h | 41.0 f | 30.47 h |

| SA | 64.0 d | 21.0 c | 310.0 e | 85.0 d | 38.93 e |

| TS | 60.0 e | 18.3 d | 250.0 f | 72. 7 e | 36.33 f |

| SR | 50.0 f | 14.7 e | 204.7 g | 67.7 e | 33.73 g |

| TS + SR | 69.3 c | 22.0 c | 354.3 d | 101.3 c | 42.33 d |

| SA + TS | 77.3 b | 24.3 b | 445.0 b | 110.3 b | 48.0 b |

| SA + SR | 75.67 b | 21.7 c | 396.7 c | 106.3 bc | 44.7 c |

| SA + TS + SR | 86.33 a | 30.0 a | 543.0 a | 146.3 a | 52.63 a |

| LSD.05 | 3.34 | 2.2 | 38.24 | 5.69 | 1.20 |

| 2021 season | |||||

| Control | 40.3 h | 13.0 e | 157.0 g | 42.0 f | 31.57 h |

| SA | 60.3 e | 22.7 c | 313.3 d | 85.3 d | 40.0 e |

| TS | 53.9 f | 19.0 d | 256.7 e | 73.3 e | 37.4 e |

| SR | 45.9 g | 15.3 e | 207.3 f | 68.3 e | 34.6 e |

| TS + SR | 71.3 d | 22.7 c | 352.7 d | 102.7 c | 43.1 d |

| SA + TS | 86.0 b | 25.3 b | 446.7 b | 111.7 b | 48.8 b |

| SA + SR | 79.0 c | 22.3 c | 399.3 c | 107.3 bc | 45.5 c |

| SA + TS+ SR | 95.0 a | 31.7 a | 546.7 a | 149.0 a | 53.9 a |

| LSD.05 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 39.68 | 6.857 | 1.2 |

| No. | RT | Compounds | Area % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.44 | 1-methoxy-2-acetoxypropa NE | 4.97 |

| 2 | 4.27 | Cyclohexane, (ethoxymethoxy)- | 1.40 |

| 3 | 4.35 | Tetracarbonyl) [1-(t-buty l)-2,4-bis{[2′,4′,6′-tris(t-butyl) phenyl] imino}-1-aza-2,4-dip hospha-3-molybdacyclobutane | 0.96 |

| 4 | 4.59 | Z)-6-deoxy-1,2-o-isopropyliDene-3,4-di-o-methyl-5-à-d-xYlo-hepteno-furannurononItrile | 0.96 |

| 5 | 5.49 | 2H-Pyran, 3,6-dihydro-4-methyl-2-(2-methyl-1-p ropenyl)- | 0.86 |

| 6 | 7.13 | 1-pentene, 3,4-dimethyl- | 1.28 |

| 7 | 8.14 | 1,5-pentanediamine | 1.18 |

| 8 | 9.91 | 6-benzyloxy-7-methoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline | 4.91 |

| 9 | 13.08 | 1,5-Hexadien-3-yne, 2-methyl- | 2.11 |

| 10 | 13.13 | Benzeneacetic acid | 1.02 |

| 11 | 13.20 | Cycloheptatrienylium, iodide | 2.50 |

| 12 | 13.46 | 1,5-Hexadien-3-yne, 2-methyl- | 0.47 |

| 13 | 14.21 | 1,6-Heptadien-3-yne | 0.78 |

| 14 | 15.29 | 3-Benzylsulfanyl-3-fluoro-2-trifluoro Methyl-acrylonitrile | 1.11 |

| 15 | 15.48 | 3-pyridinemethanol | 0.68 |

| 16 | 15.92 | Nà-Z-D-2,3-Diaminopropionic acid | 1.23 |

| 17 | 16.18 | Progesterone 3-biotin | 2.33 |

| 18 | 16.45 | Tetrahydro-1,3-oxazine-2-thione | 0.60 |

| 19 | 17.52 | [5-(4′-Formyl phenyl) -10,15,20-tris(4″-tolyl) porphyrinat o] zinc(ii) | 1.46 |

| 20 | 18.67 | 2)-n-cyclohexyl carbamoyl)-4-methoxy-4-methyl-6,6-diphe nyl-2,9,10-triazatricyclo [5. 2.2.0(1,5)] undeca-4,8,10-trien-3-one | 0.64 |

| 21 | 19.45 | Gln-pro-arg | 1.75 |

| 22 | 22.40 | 7-Oxabicyclo [4.1.0] heptan-2-one | 2.93 |

| 23 | 24.74 | 1-butanol, 2-nitro | 2.77 |

| 24 | 25.80 | Oxalic acid, cyclobutyl nonyl ester | 1.72 |

| 25 | 28.22 | 4-hydroxyhexenal | 3.48 |

| 26 | 35.84 | Norcollatone | 2.31 |

| 27 | 36.26 | 2,4,5-tris)Isopropyl)-1,1,3,3-tetrachlOro-2,4,5-triphospha-1,3-dig Ermolane | 4.06 |

| 28 | 36.58 | Hemin cation | 38.95 |

| Histological Aspects | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 40 ppm (SA) | (SR + TS) | 40 ppm SA and (SR + TS) | |

| Thickness of midvein | 2020.766 | 2404.648 | 2501.365 | 2812.411 |

| Thickness of upper epidermis | 12.132 | 12.418 | 13.459 | 15.422 |

| Thickness of lower epidermis | 6.987 | 7.196 | 8.633 | 8.951 |

| Thickness of lamina | 120.173 | 120.688 | 124.944 | 145.919 |

| Thickness of palisade tissue | 40.700 | 44.202 | 42.102 | 50.911 |

| Thickness of spongy tissue | 53.877 | 57.404 | 62.465 | 69.911 |

| No of vascular bundle | 4.000 | 4.000 | 5.000 | 6.000 |

| Dimentions of main midvein bundle | 454.521 | 469.419 | 490.742 | 559.504 |

| No of xylem rows in main midvein bundle | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.5 |

| Mean diameter of vessels | 30.614 | 30.699 | 30.888 | 30.921 |

| Mean diameter of paranchyma cells in ground tissues | 104.666 | 111.945 | 108.887 | 120.111 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reyad, N.E.-H.A.; Azoz, S.N.; Ali, A.M.; Sayed, E.G. Mitigation of Powdery Mildew Disease by Integrating Biocontrol Agents and Shikimic Acid with Modulation of Antioxidant Defense System, Anatomical Characterization, and Improvement of Squash Plant Productivity. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8121145

Reyad NE-HA, Azoz SN, Ali AM, Sayed EG. Mitigation of Powdery Mildew Disease by Integrating Biocontrol Agents and Shikimic Acid with Modulation of Antioxidant Defense System, Anatomical Characterization, and Improvement of Squash Plant Productivity. Horticulturae. 2022; 8(12):1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8121145

Chicago/Turabian StyleReyad, Nour El-Houda A., Samah N. Azoz, Ayat M. Ali, and Eman G. Sayed. 2022. "Mitigation of Powdery Mildew Disease by Integrating Biocontrol Agents and Shikimic Acid with Modulation of Antioxidant Defense System, Anatomical Characterization, and Improvement of Squash Plant Productivity" Horticulturae 8, no. 12: 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8121145

APA StyleReyad, N. E.-H. A., Azoz, S. N., Ali, A. M., & Sayed, E. G. (2022). Mitigation of Powdery Mildew Disease by Integrating Biocontrol Agents and Shikimic Acid with Modulation of Antioxidant Defense System, Anatomical Characterization, and Improvement of Squash Plant Productivity. Horticulturae, 8(12), 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8121145