Abstract

The cultivation of Echinacea purpurea for commerce and obtaining high-quality plant material on a large scale remain a challenge for growers. Another challenge for the following decades is to create sustainable agriculture that meets society’s needs, has no environmental impact, and reduces the use of fertilizers and pesticides. The aims of this overview were: (1) to present the importance of the chemical compounds reported in E. purpurea; (1) to synthesize results about cultivation of the E. purpurea with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and associated microorganisms; (2) to exemplify similar research with plants from the Asteraceae family, due to the limited number of published Echinacea studies; (3) to collect recent findings about how the inoculation with AMF affects gene expressions in the host plants; (4) to propose perspective research directions in the cultivation of E. purpurea, in order to increase biomass and economic importance of secondary metabolite production in plants. The AMF inocula used in the Echinacea experiments was mainly Rhizophagus irregularis. The studies found in the selected period (2012–2022), reported the effects of 21 AMFs used as single inocula or as a mixture on growth and secondary metabolites of 17 plant taxa from the Asteraceae family. Secondary metabolite production and growth of the economic plants were affected by mutualistic, symbiotic or parasitic microorganisms via upregulation of the genes involved in hormonal synthesis, glandular hair formation, and in the mevalonate (MVA), methyl erythritol phosphate (MEP) and phenylpropanoid pathways. However, these studies have mostly been carried out under controlled conditions, in greenhouses or in vitro in sterile environments. Since the effect of AMF depends on the variety of field conditions, more research on the application of different AMF (single and in various combinations with bacteria) to plants growing in the field would be necessary. For the identification of the most effective synergistic combinations of AMF and related bacterial populations, transcriptomic and metabolomic investigations might also be useful.

1. Introduction

The purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench) from the Asteraceae (Compositae) family is a perennial ornamental and medicinal plant native to North America, known primarily for its role in the immune system.

In recent decades, it has received increasing attention in pharmaceutical studies due to the diverse bioactive constituents it contains. Chemical compounds reported from Echinacea purpurea include phenolic compounds (phenolic acids and flavonoids), alkamides, essential oil, polysaccharides, and glycoproteins [1,2,3,4]. Scientific research has suggested that alkamides, glycoproteins, polysaccharides, and caffeic acid derivatives (CADs) are responsible for Echinacea’s immunostimulatory activity [2,3,4,5].

E. purpurea is one of the most widely used herbs in traditional medicine for the treatment of respiratory diseases by stimulating the immune system [6,7,8]. Herbal end products are regulated by national pharmacopeial standards [9,10,11] and European Union regulations [12]. According to Munteanu et al. [13], E. purpurea is commonly used to prepare capsules, extracts and tinctures for herbal supplementation. The most common herbal parts in trade are leaves and above-ground parts, E. purpurea herba, but roots, E. purpurea radix, are also listed in the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy Monographs [12,14].

E. purpurea grows best in soils with a pH of 6 to 7. Drought cycles and plant stress are thought to raise levels of beneficial constituents [15]. In general, dry, low-nitrogen soils produce higher concentrations of essential oils. Wet, nitrogen-rich soils produce high levels of alkaloids [16]. Differences in soil type (sandy or loamy) and fertilization regime also have an impact on the presence and amount of phenolic compounds [17].

In its native habitat, E. purpurea is frost-resistant and is a hardy perennial, and it can tolerate temperatures of −25 °C to −40 °C if there is a snow layer. In Europe, Echinacea winters safely throughout southern and central Europe [15]. While E. angustifolia develops only basal leaves in the first year and develops flowers only in the second year, field-grown E. purpurea populations bloom in a proportion of 40–60% in the first year [13].

E. purpurea can be cultivated by sowing and transplanting. Despite the many advantages of transplanting over direct sowing, it is still neglected in practice because of its time-consuming requirements [13]. The low germination rate and the seed dormancy cause further difficulties in large-scale production [18,19]. Although micropropagation has great potential for producing plants with large amounts of plant material and enhanced secondary metabolites, acclimatization of plants is proving difficult [20,21]. Therefore, the cultivation of E. purpurea for economic purposes and obtaining high-quality plant material on a large scale remain a challenge for growers.

Another challenge for the following decades is to create sustainable agriculture that meets society’s needs, has no environmental impact, and reduces the use of fertilizers and pesticides. Beneficial soil micro-organisms, which play a key role in maintaining long-term soil fertility and health, reducing chemicals in agriculture, providing plant nutrition and producing safe and quality crop products, can provide a solution to achieving these objectives [22].

Endophytes are microbial species that colonize plants without causing disease and are associated with almost all terrestrial plants. Of the endophytes, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) have the most extensive plant symbiosis, being able to colonize the roots of more than 80% of terrestrial plants through hyphal networks. AMF’s hyphae penetrate the interior of the root cells, but they do not enter through the plasma membrane into the symplast. Arum-type mycorrhizae are present in the intercellular spaces as well, and form in the cells’ terminal arbuscules. Several species also have vesicles in addition to arbuscules, which are older hyphal structures. Paris-type mycorrhizae present an intracellular growth, forming coils of hyphae and intercalary arbuscules. The host plant absorbs from the arbuscules the accumulated minerals [22,23]. Approximately 320 AMF species have been classified in the phylum Glomeromycota, but relatively few species were studied in their interactions with various host plants [22,24,25]. In this mutualistic–symbiotic relationship, the fungus supports the nutrients uptake (especially phosphorus) of the roots through the mycelia by providing a large surface area, and in return receives carbohydrates (photosynthesized sugars), vitamins and amino acids from the plant as organic nutrients [22,26,27,28,29,30].

Recent studies have shown that AMF and their associated bacterial communities (the mycorrhizospheric bacteria) are able to change the quantity and quality of secondary metabolic products in the host plant. In addition, these studies also described changes in other properties of the plants, e.g., biomass increase, better nutrient uptake and water balance, increase in glandular hairs density, changes in the synthesis of plant hormones, and improved resistance to stress [22,30,31].

The aims of this overview were: (1) to present the importance of the chemical compounds reported in E. purpurea; (1) to synthesize results about cultivation of E. purpurea with AMF and associated microorganisms; (2) to exemplify similar research with plants from the Asteraceae family, due to the limited number of published Echinacea studies; (3) to collect recent findings about how the inoculation with AMF affects gene expressions in the host plants; (4) to propose perspective research directions in the cultivation of E. purpurea, in order to increase biomass and economic importance secondary metabolite production in plants.

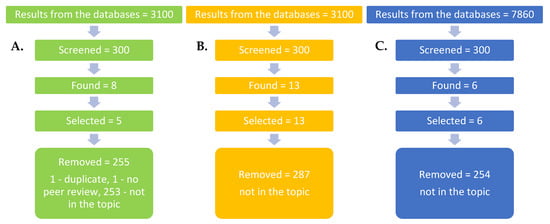

The specialty literature (24 articles) included in this overview was collected from the Science Direct, Springer Link and Google Academic platforms (Figure 1). Because of the small number of literature studies in the case of the genera Echinacea and the species Echinacea purpurea cultivated with the mutualistic or symbiotic microorganisms (five articles), all times works were used. The terms of search were the following: Echinacea, Echinacea purpurea, mycorrhyza, AMF, growth, chemical compounds, bioactive compounds, bioactive principles, and secondary metabolites. The search was extended also on the species from the Asteraceae family. In this case, the literature of the years 2012–2022 (13 articles) were included. In order to collect the recent findings about how the inoculation with AMF affects gene expressions in different host plants, the literature of the past 10 years was consulted, and six articles were selected. The search terms were the following: mycorrhiza, AMF, gene expression, and mechanism of action.

Figure 1.

Literature research and article collection: (A) Echinacea cultivated with arbuscular mycorrhiza for enhancing growth and secondary metabolite production. (B) Plants from Asteraceae family cultivated with arbuscular mycorrhiza for enhancing growth and secondary metabolite production. (C) Arbuscular mycorrhiza effect on gene expressions in different host plants.

2. Importance of Chemical Compounds Reported in Echinacea purpurea

Numerous phytochemicals have been detected in E. purpurea. The most relevant of these compounds are alkamides, caffeic acid derivatives (mainly chicoric acid, chlorogenic acid, caftaric acid, cynarin, and echinacoside) [32,33,34], essential oil (predominantly borneol, carvomenthene, β -caryophyllene, myrcene, limonene, germacrene D, α- and β-pinen) [1,35,36,37,38], glycoproteins and polysaccharides [1,39,40,41].

2.1. Alkamides

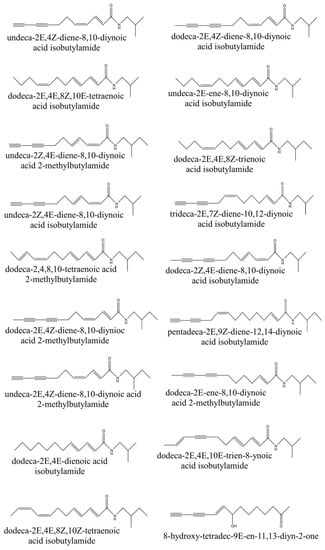

The alkamides found in E. purpurea [42,43] are presented in Figure 2. Fatty acid amides possess numerous biological activities [44], and are involved in signaling pathways relevant to inflammation, pain, cancer and cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, Cruz et al. [45] suggested that alkamides may play a role in disrupting the fungal cell wall/membrane complex. A study conducted by Chicca et al. [46] reported that N-alkylamides exert modulatory effects on the endocannabinoid system by simultaneously targeting endocannabinoid transport and degradation as well as the human cannabinoid receptor type-2 (hCB2). There has also been research into its use in crop protection. Clifford et al. [47] reported on the insecticidal activity of alkamides found in the roots of E. purpurea. These alkamides exerted a mosquitocidal effect on the larvae of Aedes aegypti, such that at 100 and 10 μg/mL, 100% mortality was reported.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of alkamides found in Echinacea purpurea (original).

2.2. Caffeic Acid Derivates

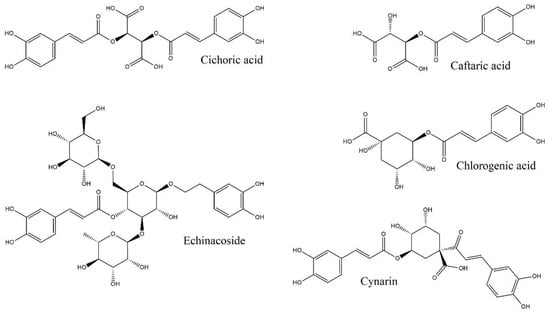

It was shown in the case of E. purpurea that cichoric acid was the main caffeic acid derivative (CAD) along with caftaric acid, while chlorogenic acid, echinacoside (found in the flowers, leaves and stem), and cynarin were present only in small amounts [31,48,49]. The CADs reported in E. purpurea are included in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of caffeic acid derivatives (CADs) present in Echinacea purpurea (original).

In contrast to alkamides, which were found in rhizomes and roots of E. purpurea, CADs were more abundant in above-ground parts, such as flowers [1,50].

Phenolic compounds are thought to be responsible for antioxidant and antiviral activity [6,19,49,51,52,53,54]. Tsai et al. [55] reported that Echinacea extracts rich in cichoric acid induced apoptosis and reduced telomerase activity in intestinal cancer cells at concentrations of 200–500 μg/mL under in vitro conditions. In addition, Jeong et al. [56] have pointed out that cichoric acid in purple coneflower has antihyaluronidase activity and inhibits HIV-1 integrase and replication.

2.3. Glycoproteins and Polysaccharides

Various polysaccharides have been described in E. purpurea. These components were first isolated by Wagner and Proksch [57], who detected two neutral fucogalactoxyloglucans (PS I, PS II) from the aerial parts, in which the main components of the fractions were arabinose, xylose, and galactose (PS I), and rhamnose, arabinose, xylose, and galactose (PS II), respectively [2]. Moreover, in a later research project [39,40] an acidic arabinogalactan, 4-O-methyl-glucuronoarabinoxylan, was identified from the hemicellulose fraction of E. purpurea. Another arabinogalactan protein was isolated from a suspension culture of E. purpurea containing a large amount of polysaccharide, the major monosaccharides being galactose and arabinose, a small protein fraction, and some glucuronic acid [41].

Polysaccharides and glycoproteins have been found in the aerial parts [58,59] of E. purpurea, such as in the leaves, stems and flowering tops, but also in the belove-ground parts [60,61,62], such as in the rhizomes and roots, but in general, research has tended to focus on the root parts.

Polysaccharides and glycoproteins are thought to be key components of the immunostimulatory properties of E. purpurea [8,31,63,64]. In addition to their immunostimulating effect, the antioxidant activity of polysaccharides has also been described [65].

Several studies have confirmed its positive effects under in vitro and in vivo immunological test systems. Wagner et al. [40] reported that fucogalactoxyglucan enhanced phagocytosis, as compared to arabinogalactan, which specifically stimulated macrophages to secrete tumor necrosis factor (TNF). The results of Burger et al. [66] supported this research and showed that the polysaccharide constituent of Echinacea increased the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) by macrophages in vitro. Luettig et al. [67] have shown that E. purpurea-derived polysaccharides stimulated T-cell activity more effectively than highly potent T-cell stimulators.

Barrett [68] has noted that polysaccharides from E. purpurea increased macrophage activity in mouse, rat and human experiments. Moreover, subsequent in vivo studies found that the purified polysaccharides provided protection against Listeria monocytogenes and Candida albicans infections by enhancing the activity of phagocytes [21,60,69,70].

Vimalanathan et al. [71] conducted a study that reported significant activity of polysaccharide-rich Echinacea extract against herpes simplex (HSV) and influenza virus (FV), which was also supported in a recent study by Liu et al. [72].

2.4. Volatiles

Volatile compounds can be detected in aerial parts and roots, with variable yields and chemical compositions [35,64,73,74]. The essential oil distilled from the roots of Echinacea species yields between 0.3 and 2.4% (v/w), although the aerial parts of the plants were observed to possess a smaller level of volatiles, yielding between 0.1 and 1.8% (v/w) [49,59,61,75].

According to Stănescu et al. [38], the volatile oil isolated from the aerial parts of E. purpurea contains mainly borneol, bornyl-acetate, caryophyllene, caryophyllene-epoxide, and germacrene D.

Schulthess et al. [35] conducted a thorough study of volatile compounds in ethanolic extracts of E. purpurea and essential oils from the achenes of three pharmaceutically approved species. The main components of E. purpurea were found to be α-pinene, β-farnesene, myrcene, limonene, carvomenthene, caryophyllene and germacrene D; however, it was highlighted that germacrene D, carvo-menthene and caryophyllene were characteristic of the achenes of E. purpurea.

Holla et al. [37] investigated the volatile oil content of E. purpurea flower heads grown in Slovakia. Seventy-two components were discovered, which consisted mainly of palmitic acid, germacrene D, α- and β-pinen.

Antimicrobial [76,77], antifungal [47,78], antioxidant [79] and antibacterial [80] properties of E. purpurea essential oil have been proven in numerous studies. According to Nyalambisa et al. [81], the essential oil from the roots of South African E. purpurea had strong anti-inflammatory and analgesic actions on rodents. Another study found that essential oil isolated from the flowers of E. purpurea had anti-inflammatory effects, as it greatly reduced the development of ear edema in rats [82].

Noorolahi et al. [83] found that E. purpurea essential oil extract had a strong antimicrobial effect on Escherichia coli, Enterobacteriaceae, and Bacillus cereus.

In a recent study, Teke and Mutlu [84] found that Echinacea oil, composed principally of β-cubebene and caryophyllene, caused 99.59% mortality of Sitophilus granarius 72 h after application, finally concluding that Echinacea oil has potential for use in the control of storage grain pests.

3. Echinacea purpurea Cultivation with Mutualistic–Symbiotic Microorganisms

In a current review, various Echinacea production biotechnologies were analyzed. Production of Echinacea in bioreactors and genetic engineering of plants can considerably increase, in a short time, the biomass and the content of active principles in plants, but these techniques are still too expensive, and large-scale production often decreases the yield. Polyploidy results in dwarf phenotypes in the case of Echinacea plants. The production of polyploid organisms is an unfeasible method due to the lower biomass of the plants, which results, on a larger scale, in lower yield of secondary metabolites and plant material [31].

The cultivation of entire plants appears to be the most profitable approach for the production of herbal products. In this context, the use of natural elicitors (e.g., growth regulators, natural stress response molecules) or mutualistic–symbiotic microorganisms in semi-open field and open field cultures could be a cost-effective and environmentally friendly method to increase biomass and active principles in plants.

Most of the studies with E. purpurea that used elicitor induction were made in vitro (under controlled conditions), in bioreactors using the technology of wounded plants infected by Agrobacterium rhizogenes. The elicitors increased, besides biomass, the contents of cichoric acid, caftaric acid, alkylamides, anthocyanins, phenolics, flavanoids, and polysaccharides [6,31,85].

Although a large number of beneficial plants have been studied to observe the effects of mycorrhization, and despite the promising bioactive profile of E. purpurea, relatively few studies (a total of 5 studies) have been published with this species. The experiments about E. purpurea cultivation with mutualistic or symbiotic microorganisms are included in Table 1. In all cases, inoculation was made with Rhizophagus irregularis (except for one experiment when, besides R. irregularis, Beauveria bassiana and Gigaspora margarita were used) as single inocula or in combination with growth-promoting bacteria. Positive results were obtained both in greenhouse experiments [86,87,88] and in open-field cultivation [89,90]. Araim et al. [86] investigated the effect of AMF on the roots and shoots growth, but also on mineral, protein, alkamide, and phenolic acid contents of the concerned organs. Gualandi et al. [87,88] evaluated the pigment, sesquiterpene, and alkamide content of the leaves in addition to the plant growth characteristics.

In open-field conditions, results were reported on plant growth, nutrient content of the leaves and roots, and essential oil content of the roots [89,90].

The AMF and their associated microbiota increased not only plant biomass, but also the content of the following active principles: cichoric, caftaric, and chlorogenic acids, cynarin, alkilamides, essential oil and its compounds (beta-carophyllene, alpha-humulene, and germacrene-D).

Table 1.

Echinacea purpurea cultivation with mutualistic microorganisms.

Table 1.

Echinacea purpurea cultivation with mutualistic microorganisms.

| Microorganisms | Experimental Setup | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glomus intraradices | - plants grown in a greenhouse, in pots filled with autoclaved sand/soil mixture (1:1, v/v) for 13 weeks | - increase in total mass, height, and leaves number - increase in P and Cu content in the shoot - increase in different phenolic acids content (cichoric, caftaric, and chlorogenic acids, and cynarin) in root - increase in total phenolic acids content in shoot | [86] |

| Glomus intraradices, Gigaspora margarita, Beauveria bassiana | - plants grown in a greenhouse, in pots with calcined montmorillonite clay for 12 weeks | - increase in biomass and positive influence on plants development in severe nutrient deficiency stress, in the case of G. intraradices - increase in cichoric and caftaric acids content in leaves in the case of G. intraradices, and in the whole plant (root + shoot) in the case of G. intraradices, and those treated with mycorrhiza in combination with Beauveria bassiana - increase in relative concentration of two alkamides in roots in the case of plants treated only with Beauveria bassiana, high phosphorus and B. bassiana, and mycorrhyza in combination with B. bassiana - increase in beta-carophyllene, alpha-humulene, and germacrene- D in leaves in the case of G. intraradices, high phosphorus and B. bassiana, and mycorrhyza in combination with B. bassiana | [87,88] |

| Azospirillum lipoferum, Azotobacter chroococcum, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Glomus intraradices | - seedlings with 4–6 leaves transplanted and grown in open field conditions, on clay-loam soil, harvested after 6 months (October) in the first year, and in August in the second year | - combination of the three bacteria species with mycorrhiza resulted in significantly higher root and shoot mass, shoot length, larger number of branches, flower buds, and inflorescences, the results being similar with those obtained by NPK treatment - treatments with mycorrhiza or with the mixture of the three bacteria increased the essential oil content of roots in the first year | [89] |

| Rhizophagus irregularis, Pseudomonas fluorescens | - 90-day-old seedlings transplanted in open field conditions, harvested after 6 months (November) in the first year, and in September in the second year | - increase in N, Cu, Fe and P contents in the case of mycorrhizal plants and those treated with Pseudomonas fluorescens - increase in relative water content, plant height, leaf number, and leaf area index in the case of mycorrhizal plants - increase in Zn content and plant height in the case of plants treated with P. fluorescens - increase in the biological yield (g plant/m2) in the case of mycorrhizal plants and those treated with P. fluorescens in the second year | [90] |

4. Plants from the Asteraceae Family Cultivated with Mutualistic–Symbiotic Microorganisms

Due to the limited number of published Echinacea studies with AMF species, this overview aims to exemplify similar research with plants from the Asteraceae family. One of the largest plant families is Asteraceae with more than 23,600 currently recognized species [91]. Plants from the Asteraceae family have several biochemical particularities, e.g., the presence of essential oils, glycosides, alkaloids, pyrethrins (sesquiterpene lactones), coumarins, latex with rubber resins, different bitter principles, inulin (polysaccharides) etc. [92].

A total of 13 articles were found in the selected period (2012–2022), reporting the results on growth and secondary metabolites of 17 plant taxa cultivated with AMFs.

4.1. Greenhouse Experiments

According to the collected articles, most of the experiments were conducted in greenhouse conditions, in plastic pots or root trainers. One of the research studies was conducted in a climatic chamber [93]. The substrates were sterilized using autoclave or steam, except for in Kheyri et al. [94] and Majewska et al. [95], who tried to partially simulate open-field conditions by using non-autoclaved soil. In the recently published articles, usually a larger number of AMF species were selected to investigate the effects of inoculations on different cultivars or micropropagated plants, in order to compare changes in growth and chemical compounds.

Kheyri et al. [94], in an experiment with Calendula officinalis, used as a single inocula, the following AMF species: Glomus mosseae, G. intraradices, G. fasciculatum, G. caledonium, G. claroideum, G. versiform, G. geosporum, G. etanicatum, and G. gigaspora. Plants were collected at 90 days after transplanting. The AMFs with the highest colonization rates were G. mosseae, G. etanicatum, and G. geosporum. These species had a significant positive effect on all measured parameters: plant growth and biomass, relative water content, photosynthesis pigments, soluble sugars, soluble protein and antioxidant enzyme activities, antioxidant activity, mineral nutrient concentrations, total phenol content, and total flavonoid content. In another study with Tagetes erecta [96], application of Rhizophagus irregularis, Claroideoglomus claroideum, Glomus hoi, Claroideoglomus etunicatum, and Acaulospora delicata was made singly. Measurements were assessed at three months after inoculation. In comparison to the control, plant growth, metabolite production, and mineral nutrient concentrations all increased. Inoculation with R. irregularis produced the best results.

In several studies, micropropagated plants were cultivated to eliminate genotype differences, but also to obtain plants free of mycorrhiza. The secondary metabolite production depends greatly on the genotypes. Consequently, another tendency in studies was the comparison of several cultivars. In the case of two micropropagated cultivars of Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus, the effects of the following AMFs were compared: Funneliformis mosseae, Rhizoglomus irregulare, Claroideoglomus claroideum, and an undescribed Glomus sp. [97]. Plants were grown from March until September. The measured parameters were total phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, chlorophyll content, and mineral content. Among the studied AMFs, Claroideoglomus claroideum significantly increased the total phenolic content and the chlorogenic acid content of both cultivars. Antioxidant activity was enhanced by C. claroideum and Funneliformis mosseae. In another study, Mikania glomerata and M. laevigata plants propagated vegetatively using stem cuttings were cultivated for 8 weeks [98], after inoculation with Rhizophagus irregularis. Besides the positive effects of the fungi (significant increase in foliar biomass and diterpene kaurenoic acid content in M. laevigata, mineral content in leaves of both species), it was observed that AMFs significantly reduced the tricaffeoylquinic acid contents in leaves of M. glomerata.

Avio et al. [99] investigated the effect of Rhizophagus irregularis and Funneliformis mosseae on two cultivars of Lactuca sativa var. crispa. Changes in total phenolics and antioxidant activities differed by AMFs and cultivars. R. irregularis significantly increased total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of both cultivars, while anthocyanins content was enhanced by both AMF species only in the red leaf cultivars.

In addition, experiments with a mixture of AMF species were conducted. Although there were more flowers in the case of Calendula officinalis ’Calypso Orange with Black Eye’ cultivar due to the AMF colonization (mixture of Claroideoglomus etunicatum, C. claroideum, and Rhizophagus irregularis), these flowers were smaller. Hence, the flower production was not significantly different from control plants. The AMF mixture increased the concentration of two of the eight phenolic compounds identified in the flowers of Marigold plants, but the major phenolic constituents were not increased [100].

The effects of Rhizophagus irregularis, Funneliformis mosseae, and Claroideoglomus claroideum in different soil types were evaluated in the case of two invasive species: Rudbeckia laciniata and Solidago gigantea [95]. Soils were collected from two characteristic habitats. The growth of the plants, concentration of phosphorus, and photosynthetic performance were measured after 3 months. C. claroideum showed no effect on R. laciniata. Both R. irregularis and F. mosseae increased the biomass of Rudbeckia plants. However, the results varied according to the type of soil. Although the variations were more apparent in the fallow soil, Solidago gigantea responded favorably to all applied AMF species, with R. irregularis being the most successful in enhancing biomass. Photosynthetic performance of both plants was influenced only by the soil type, while P concentration in shoots and roots was dependent on AMFs and soil types. The best results in P enhancement were obtained with R. irregularis.

AMFs were used to enhance growth and flower quality of two ornamental species: Chrysanthemum morifolium and Tagetes erecta [101]. The experiment was conducted in a shade net, on pots filled with sterile soil. Inoculation was made with pure cultures of Acaulospora laevis, A. scrobiculata, Glomus coremioides, G. intraradices G. fasciculatum, G. mannihotis, and Gigaspora albida. All AMF treatments significantly enhanced the early flowering and the number of flowers in the case of C. morifolium. Dry weights of both plant species were significantly higher due to the treatments (except for T. erecta plants treated with A. laevis). G. intraradices proved to be more efficient for the increase in flower number in the case of T. erecta. Root length, plant height and moisture-retaining ability of flowers were also enhanced by the different AMF species depending of the host plants.

Not all research studies reported positive results. Duc et al. [93] in an experiment with salinity stress, besides others, examined how several single AMF species—including Funneliformis mosseae, Septoglomus deserticola, and Acaulospora lacunosa—as well as a combination of six AMF species (Claroideoglomus etunicatum, C. claroideum, Rhizoglomus microaggregatum, Rhizophagus intraradices, Funneliformis mosseae, and F. geosporum) affected the growth and the physio-biochemical traits of the E. prostrata plant under non-saline environments. S. deserticola significantly decreased fresh shoot weight after 4 and 8 weeks of plant growth. At 4 weeks, F. mosseae, S. deserticola, and A. lacunosa significantly decreased plant height in comparison to the control plants. After 8 weeks, S. deserticola significantly reduced the total phenolic concentration in comparison to control plants and other single AM treatments. When compared to control plants, AMFs did not increase proline content under non-stressful situations.

4.2. Semi-Open Field and Open Field Experiments

Only a few studies were published with AMF application in semi-open field (plants grown outside in pots) and open field conditions. Besides the frequently used species (Rhizophagus irregularis and Funneliformis mosseae), inoculations with other AMFs (Septoglomus viscosum, Acaulospora laevis, A. scrobiculata, Glomus coremioides, G. fasciculatum, G. mannihotis, and Gigaspora albida) and AMF mixtures were also attempted.

In an experiment with Stevia rebaudiana [102], three micropropagated chemotypes were cultivated on loamy soil (in southern Italy) for three vegetation periods. The measured parameters were: diterpene glycosides content, dry leaf and stem yield. Septoglomus viscosum only improved leaf yield, especially in the case of two chemotypes.

Artemisia annua plants grown outside (in Romania), in pots filled with sterile peat, inoculated with R. irregularis, showed an increase of 30% in fresh and dry biomass compared to control plants [103]. Compared to untreated plants, those colonized with AMF had significantly higher artemisinin content, with an average of 17%. The glandular hairs were shown to be significantly correlated with artemisinin concentration. Similar experiments were conducted in pots with three characteristic soil types from the region (endostagnic argic Luvisol, stagnic colluvic Gleysol, and stagnic gleyic Anthrosol) and sterile peat [104]. Plants were grown outside. R. irregularis significantly improved the artemisinin and essential oil content of the potted plants grown in all of the studied substrates. Biomass was increased considerably by AMFs only on sterile peat. In the same experimental year, inoculated plants were also grown in open field, on stagnic vertic Luvisol. Inoculation caused a significant decrease in stem biomass compared to the control. While no differences were observable in the case of artemisinin content, the essential oil content was increased. When comparing the essential oil yield of AMF-treated plants grown in pots to those grown in open field soil, no significant differences were detected. Differences in chemical compound abundance were registered (higher concentrations of beta-farnesene and germacrene D in AMF plants).

Bączek et al. [105] used an AMF mixture from Rhizophagus intraradices (BEG140), Funneliformis mosseae, Claroideoglomus claroideum (BEG 210), Funneliformis geosporum, Rhizophagus intraradices (SAMP7), and Claroideoglomus claroideum (E10) for the cultivation of Matricaria recutita on alluvial soil (in Poland). Plant growth parameters (fresh mass of the root and herb, number of flowering shoots) and phenolic compound content of pharmaceutical importance (chlorogenic, caffeic, ferulic, and rosmarinic acids as well as apigenin-7-O-glucoside, isorhamnetin, and luteolin-4′-glucoside) were enhanced in the inoculated plants. The essential oil yield and composition were not affected by the inoculation.

Based on the above studies with E. purpurea relatives and their interactions with AMFs, several research directions have been outlined in order to improve the growth and production of secondary metabolites in E. purpurea. Considering the biodiversity of the AMF species, comparative experiments are recommended for evaluation of their effects on the host plant. In addition, inoculation with AMF mixtures should be attempted to assess the influence of synergistic activities on plant development. It would be important to test various E. purpurea cultivars because variations in genotype have a significant impact on secondary metabolites. The positive effects of mutualistic–symbiotic microorganisms on host plants were described in the case of several medicinal and crop plants. The most utilized AMF fungi were Rhizophagus irregularis and Funneliformis mosseae [22]. Since the effect of AMF depends on the variety of field conditions, more research on the application of different AMF (singly and in various combinations with mycorrhiza helper/plant growth promoter bacteria) to Echinacea plants growing in the field would be necessary.

5. Mycorrhiza’s Mechanism of Action in Secondary Metabolite Production

In the case of plant elicitors, the proposed mechanisms for increase in CADs, phenolics, and flavonoids is through the phenylpropanoid pathway, activated by the defense response of the plants and up-regulation of the genes involved in these processes [31,106].

Kapoor et al. [107] and Kumar et al. [30] in their comprehensive reviews have synthesized the possible mechanisms of AMF in enhancing the production of chemical compounds in host plants. The following interconnected mechanisms were proposed: biomass increase in different organs (root, shoot, leaves etc.), enhancement of phosphorus, nitrogen and micronutrients (Mn, Mg, Fe, Cu, Zn) uptake, alteration of the phytohormones synthesis, increase in the glandular hairs number, activation of different biosynthesis pathways, and changes in gene expressions.

The mycorrhizal relationship can result in changes in the concentration of jasmonic acid (JA), gibberellic acid (GA3), abscisic acid (ABA), and cytokinins (CKs). These plant hormones play an important role in the formation and development of glandular hairs [107]. According to Maes et al. [108], JA increased the size and number of glandular hairs, stimulated the biosynthesis of artemisinin precursors (artemisinic acid, dihydroartemisinic acid), and elevated the expression of the genes responsible for the biosynthesis of artemisinin. It was also shown that the production of JA in Artemisia annua increased due to the inoculation with Rhizophagus irregularis [109].

Schweiger and Müller [110] suggest that plants’ metabolic responses can be nutrient-mediated (higher P or N uptake from nutrient-rich environment with or without symbiosis) or from direct AMF effects (independent of nutrient supply) relying on symbiosis.

Molecular understanding of the mechanism of action of AMF and associated bacteria has been the subject of recent studies. Several experiments have been carried out to investigate the effects of mycorrhiza on gene expression in different plant species of global importance [30,107,111,112,113]. According to these results, secondary metabolite production and growth of the economic plants can be affected by mutualistic, symbiotic or parasitic microorganisms via upregulation of the genes involved in phytohormonal synthesis, glandular hair formation, and in different biosynthesis pathways, e.g., the mevalonate (MVA), methyl erythritol phosphate (MEP), and phenylpropanoid pathways (Table 2).

The synthesis of steviol-glycosides in Stevia rebaudiana starts via the MEP pathway, such as the synthesis of artemisinin and different terpenes in A. annua [114]. In the case of A. annua, the two precursors of farnesyl diphosphate (FDP)—isopentenyl diphosphate (IDP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMADP)—are synthesized in plastids via the MEP pathway and in the cytosol via the MAV pathway [115]. AMFs act on the bioactive metabolic products of A. annua through the MEP pathway (and not through the MVA pathway), while JA has an important role in the mechanism of artemisinin synthesis [109]. The transcript level of MEP pathway genes significantly increased in AMF-treated S. rebaudiana plants compared to the control during the synthesis of steviol-glycosides [109,116]. Both experiments were conducted in semi-open field conditions, in pots filled with autoclaved sandy loam soil.

Adolfsson et al. [111] investigated gene expression in Medicago truncatula mycorrhized with Rhizophagus irregularis, where the results were compared with those obtained for phosphorus-treated (non-AMF-inoculated plants) and control plants. The experiment was conducted in a growth chamber. Plants were cultivated in pots with Agsorb substrate. The expressions of genes involved in phenylpropanoid, flavonoid, terpenoid, lipid, JA, ABA, CK biosynthesis, and the MYC2 gene (the main regulator of JA-dependent responses) were increased during mycorrhizal treatment. CK levels were increased in both treatments (mycorrhizal and phosphorus), while ABA levels were increased only in mycorrhizal plants. In addition, it was reported that control plants foliar-treated with either ABA or JA induced MYC2 expression, while the expressions of flavonoid and terpenoid biosynthetic genes were induced only by JA. Shoot development was explained by CK action. ABA signaling pathways had a probable role in the defense strategies under biotic and abiotic stresses.

Xie et al. [112] inoculated Glycyrrhiza uralensis with Rhizophagus irregularis and hypothesized that the treatment would increase the amount of the two important bioactive compounds, glycyrrhizin and liquiritin, but also the expression of genes involved in the synthesis of the compounds. In this experiment, plants were cultivated in a growth chamber, in pots containing autoclaved sand and soil (1:2, v:v). The synthesis of glycyrrhizin is manly initiated by the MVA pathway. AMF significantly increased the expression of all studied genes involved in glycyrrhizin and liquiritin biosynthesis compared to controls, when an adequate amount of water was administrated to the plants. A significant increase in gene expression was also obtained when plants were exposed to moderate drought stress, except for the HMGR gene.

Table 2.

Studies reporting mutualistic, symbiotic or parasitic microorganisms that affect gene transcriptions in plants.

Table 2.

Studies reporting mutualistic, symbiotic or parasitic microorganisms that affect gene transcriptions in plants.

| Host Plant | Inocula | Upregulated Genes | Role of the Genes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemisia annua | Rhizophagus irregularis | TTG1 | synthesis of a transcription factor involved in the formation of glandular hairs | [114] |

| DXS1 | formation of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5- phosphate (DXP) in the MEP pathway | |||

| DXR | formation of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) | |||

| ADS, CYP71AV1, DBR2, ALDH1 | biosynthesis of artemisinin | |||

| Stevia rebaudiana | Rhizophagus irregularis | MDS | synthesis of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (MDS), a key enzyme in the MEP pathway | [109] |

| the first stage of the synthesis of steviol glycosides: | ||||

| DXS1 | formation of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5- phosphate (DXP) in the MEP pathway | |||

| DXR | formation of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) | |||

| the second stage of the synthesis of steviol-glycosides | ||||

| GGDPS | synthesis of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGDPS) | |||

| CPPS, KS, KO, KAH | formation of steviol | |||

| the third stage of the synthesis of steviol glycosides: | ||||

| UGT85C2, UGT74G1, UGT76G1 | glycosylation of steviol | |||

| Stevia rebaudiana | Piriformospora indica | DXR, GGDPS, KS, KO UGT85C2, UGT74G1, UGT76G1 | same roles as above | [116] |

| Medicago truncatula | Rhizophagus irregularis | 3′GT, DFR, CHMT, 4CL, LDOX, ANTHOCYANIN 5-AROMATIC ACYLTRANSFERASE, ANTHOCYANIDIN 3-O-GLUCOSYL-TRANSFERASE, ISOFLAVONOID GLYCOSYL-TRANSFERASE, ISOFLAVONOID MALONYL TRANSFERASE, CAFFEATE 3-O-METHYL-TRANSFERASE | synthesis of phenylpropanoids, flavonoids and anthocyanins | [111] |

| TERPENE SYNTHASE1, HMG-CoA REDUCTASE, SQE3,UGT73K1, CYP76A61, CYP93E2, CYP72a67v2 | terpenoid biosynthesis | |||

| TRIACYLGLYCEROL LIPASE, DGAT | lipid biosynthesis | |||

| 9-LOX, 13-LOX, AOS, AOC, MYC2, JAZ | jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis | |||

| HOMEOBOX-LEU ZIPPER ATHB-7, ZEAXANTHIN EPOXIDASE | abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis | |||

| CYTOKININ-O-GLUCOSYL- TRANSFERASE | cytokinin (CK) biosynthesis | |||

| Glycyrrhiza uralensis | Rhizophagus irregularis | HMGR | synthesis of mevalonic acid (MVA) in the mevalonate pathway | [112] |

| SQS1, β-AS, LUP | formation of squalene, β-amyrin and lupeol | |||

| CYP88D6, CYP72A154 | formation of glycyrrhetinic acid, the precursor of glycyrrhizin | |||

| CHS | formation of liquiricin | |||

| Helianthus annuus | Rhizophagus irregularis and Rhizoctonia solani parasitic fungi | PAL1, C4H | phenylpropanoid synthesis | [113] |

| CHS, CHI2, F3H, FLS1, DFR, F30H | synthesis of flavonoids | |||

| AN1, AN2 | conversion of anthocyanidin to anthocyanin | |||

| HCT, HQT, C3H | synthesis of chlorogenic acid |

Rashad et al. [113] investigated the effect of a symbiotic fungus (Rhizophagus irregularis) and a parasitic fungus (Rhizoctonia solani) on the temporal changes in the expression of major genes involved in phenylpropanoid, flavonoid and chlorogenic acid biosynthetic pathways in Helianthus annuus. The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse, in pots filled with clay–sand soil (1:2). In total, the expressions of 13 genes (known to play important roles in phenylpropanoid, flavonoid and chlorogenic acid synthesis) were studied. In their experiment, three types of treatments were used in addition to the control: plants infected with R. solani, plants colonized with R. irregularis and plants treated with both fungal species. Their results showed that all three treatments induced the transcriptional expression of the targeted genes, but the double treatment showed a better induction effect compared to the single treatments.

6. Conclusions

Studies have shown in several plant species that the mutualistic–symbiotic relationship between AMF and/or growth-promoting bacteria and host plants can increase the accumulation of primary and secondary metabolites and improve plant morphological parameters. In the case of E. purpurea, only few studies were published on this topic. The AMF inocula used in the experiments were mainly Rhizophagus irregularis. The studies found in the selected period (2012–2022) reported the effects of 21 AMFs used as single inocula or as a mixture on growth and secondary metabolites of 17 plant taxa from the Asteraceae family.

However, these studies, with E. purpurea inclusive, have mostly been carried out under controlled conditions, in greenhouses, or in vitro in sterile environments, but it should be taken into consideration that the efficiency of the mutualistic–symbiotic relationship can be greatly influenced by environmental factors and the soil microbiome of the cultivation area.

In this context, future research to explore the potential of mycorrhizal and associated microorganisms in the cultivation of E. purpurea or other economic plants could be directed toward its application in field crop production. In order to use different AMF species and other microorganisms as a biofertilizer for targeted inoculation of growing substrates in agriculture, experiments are needed to assess the ability of selected species to compete with native microorganisms.

For the identification of the most effective synergistic combinations of AMF and related bacterial populations, transcriptomic and metabolomic investigations might also be useful.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.; investigation, M.I. and E.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.; writing—review and editing, K.B., K.M., E.K., E.B. and F.V.D.; supervision, F.V.D.; funding acquisition, F.V.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, CNCS-UEFISCDI, project number PN-III-P4-PCE-2021-0750, within PNCDI III.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bruni, R.; Brighenti, V.; Caesar, L.K.; Bertelli, D.; Cech, N.B.; Pellati, F. Analytical Methods for the Study of Bioactive Compounds from Medicinally Used Echinacea Species. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 160, 443–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Kindscher, K. The Medicinal Chemistry of Echinacea Species. In Echinacea: Herbal Medicine with a Wild History; Kindscher, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 127–145. ISBN 978-3-319-18156-1. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, J.; Barros, L.; Dias, M.I.; Finimundy, T.C.; Amaral, J.S.; Alves, M.J.; Calhelha, R.C.; Santos, P.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench: Chemical Characterization and Bioactivity of Its Extracts and Fractions. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senica, M.; Mlinsek, G.; Veberic, R.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. Which Plant Part of Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench) Should Be Used for Tea and Which for Tincture? J. Med. Food 2019, 22, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarland, R.C.; Bañuelos-Hernández, A.E.; Fragoso-Serrano, M.; Sierra-Palacios, E.D.C.; Díaz de León-Sánchez, F.; Pérez-Flores, L.J.; Rivera-Cabrera, F.; Mendoza-Espinoza, J.A. Studies on Phytochemical, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Hypoglycaemic and Antiproliferative Activities of Echinacea Purpurea and Echinacea Angustifolia Extracts. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, B.H.; Stiles, A.R.; Saxena, P.K.; Liu, C.-Z. Gibberellic Acid Increases Secondary Metabolite Production in Echinacea Purpurea Hairy Roots. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 168, 2057–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, M.; Lindstrom, A.; Ooyen, C.; Lynch, M.E. Herb Supplement Sales Increase 4.5% in 2011. HerbalGram 2012, 95, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Šutovská, M.; Capek, P.; Kazimierová, I.; Pappová, L.; Jošková, M.; Matulová, M.; Fraňová, S.; Pawlaczyk, I.; Gancarz, R. Echinacea Complex—Chemical View and Anti-Asthmatic Profile. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 175, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Pharmacopoeia Commission. British Pharmacopoeia; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 2020; Volume IV. [Google Scholar]

- Comisia Farmacopeei Romane. Farmacopeea Română; X.; Editura Medicala: Bucharest, Romania, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacopea Hungarica VIII. Pharmacopea Hungarica VIII. (VIII. Magyar Gyógyszerkönyv); VIII.; Medicina Könyvkiadó Rt.: Budapest, Hungary, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ESCOP E/S/C/O/P Monographs. The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products; II.; Thieme: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu, L.S.; Tămaș, M.; Muntean, S.; Muntean, L.; Duda, M.M.; Vârban, D.I.; Mureșan, S. Tratat de Plante Medicinale Cultivate Și Spontane, 3rd ed.; Risoprint: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2016; pp. 609–622. [Google Scholar]

- ESCOP E/S/C/O/P Monographs. The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products-Supplement; II Edition, Supplement; Thieme: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Galambosi, B. Cultivation in Europe. In Echinacea; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 45–68. ISBN 0-429-21569-X. [Google Scholar]

- Kindscher, K.; Riggs, M. Cultivation of Echinacea Angustifolia and Echinacea Purpurea. In Echinacea: Herbal Medicine with a Wild History; Kindscher, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–33. ISBN 978-3-319-18156-1. [Google Scholar]

- Berbec, S.; Krol, B.; Wolski, T. The Effect of Soil and Fertilization on the Biomass and Phenolic Acids Content in Coneflower (Echinacea Purpurea Moench.). Herba Pol. 1998, 4, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Wu, H.; Geng, S.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Yang, Y.; Shultz, L.M.; Tang, T.; Zhang, N. Germination and Dormancy of Seeds in Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench (Asteraceae). Seed Sci. Technol. 2007, 35, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, M.R.; Aboul-Enein, A.M.; Ibrahim, M.M. Active Compounds and Biological Activity of in Vitro Cultures of Some Echinacea Purpurea Varieties. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2018, 42, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, H.; Andrade, Z.D.; Schaneberg, B.; Bedir, E.; Khan, I.; Moraes, R. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Inoculation Enhances Survival Rates and Growth of Micropropagated Plantlets of Echinacea Pallida. Planta Med. 2003, 69, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lema-Rumińska, J.; Kulus, D.; Tymoszuk, A.; Varejão, J.M.T.B.; Bahcevandziev, K. Profile of Secondary Metabolites and Genetic Stability Analysis in New Lines of Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench Micropropagated via Somatic Embryogenesis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 142, 111851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, L.; Palla, M.; Agnolucci, M.; Avio, L.; Sbrana, C.; Turrini, A.; Giovannetti, M. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Associated Microbiota as Plant Biostimulants: Research Strategies for the Selection of the Best Performing Inocula. Agronomy 2020, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crang, R.; Lyons-Sobaski, S.; Wise, R. Plant Anatomy: A Concept-Based Approach to the Structure of Seed Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 3-319-77315-1. [Google Scholar]

- Koide, R.T.; Mosse, B. A History of Research on Arbuscular Mycorrhiza. Mycorrhiza 2004, 14, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Arbuscular Mycorrhizas. In Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 11–149. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, A.E.; Lutzoni, F. Diversity and Host Range of Foliar Fungal Endophytes: Are Tropical Leaves Biodiversity Hotspots? Ecology 2007, 88, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, A.H.; Debbab, A.; Proksch, P. Fungal Endophytes: Unique Plant Inhabitants with Great Promises. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 1829–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Jakobsen, I.; Grønlund, M.; Smith, F.A. Roles of Arbuscular Mycorrhizas in Plant Phosphorus Nutrition: Interactions between Pathways of Phosphorus Uptake in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Roots Have Important Implications for Understanding and Manipulating Plant Phosphorus Acquisition. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doidy, J.; van Tuinen, D.; Lamotte, O.; Corneillat, M.; Alcaraz, G.; Wipf, D. The Medicago Truncatula Sucrose Transporter Family: Characterization and Implication of Key Members in Carbon Partitioning towards Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Arora, N.; Upadhyay, H. Chapter 11—Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: Source of Secondary Metabolite Production in Medicinal Plants. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Singh, J., Gehlot, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 155–164. ISBN 978-0-12-821005-5. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, J.L.; Liu, R.; Smith, M.L.; Harris, C.S. Echinacea Fruit: Phytochemical Localization and Germination in Four Species of Echinacea. Botany 2018, 96, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvizheh, H.; Zahedi, M.; Abaszadeh, B.; Razmjoo, J. Effects of Irrigation Regime and Foliar Application of Salicylic Acid and Spermine on the Contents of Essential Oil and Caffeic Acid Derivatives in Echinacea purpurea L. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 37, 1267–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attarzadeh, M.; Balouchi, H.; Rajaie, M.; Dehnavi, M.M.; Salehi, A. Improving Growth and Phenolic Compounds of Echinacea Purpurea Root by Integrating Biological and Chemical Resources of Phosphorus under Water Deficit Stress. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 154, 112763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlou-Nagy, C.; Bănică, F.; Jurca, T.; Vicaș, L.G.; Marian, E.; Muresan, M.E.; Bácskay, I.; Kiss, R.; Fehér, P.; Pallag, A. Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench: Biological and Pharmacological Properties. A Review. Plants 2022, 11, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulthess, B.H.; Giger, E.; Baumann, T.W. Echinacea: Anatomy, Phytochemical Pattern, and Germination of the Achene. Planta Med. 1991, 57, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thappa, R.; Bakshi, S.; Dhar, P.; Agarwal, S.; Kitchlu, S.; Kaul, M.; Suri, K. Significance of Changed Climatic Factors on Essential Oil Composition of Echinacea Purpurea under Subtropical Conditions. Flavour Fragr. J. 2004, 19, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holla, M.; Vaverkova, S.; Farkas, P.; Tekel, J. Content of Essential Oil Obtained from Flower Heads of Echinacea purpurea L. and Identification of Selected Components. Herba Pol. 2005, 51, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Stănescu, U.; Oana, C.; Clara, A.A.; Anca, M. Plante Medicinale de la A la Z.; Hăncianu, M., Ed.; III.; Elefant Online: Bucuresti, Romania, 2018; ISBN 978-973-46-4942-6. [Google Scholar]

- Proksch, A.; Wagner, H. Structural Analysis of a 4-O-Methyl-Glucuronoarabinoxylan with Immuno-Stimulating Activity from Echinacea Purpurea. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 1989–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Stuppner, H.; Schäfer, W.; Zenk, M. Immunologically Active Polysaccharides of Echinacea Purpurea Cell Cultures. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, B. Characterization of an Arabinogalactan-Protein from Suspension Culture of Echinacea Purpurea. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2007, 88, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudge, E.; Lopes-Lutz, D.; Brown, P.; Schieber, A. Analysis of Alkylamides in Echinacea Plant Materials and Dietary Supplements by Ultrafast Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array and Mass Spectrometric Detection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 8086–8094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaushintsena, A.; Milentyeva, I.; Babich, O.; Noskova, S.; Kiseleva, T.; Popova, D.; Bakin, I.; Lukin, A. Quantitative and Qualitative Profile of Biologically Active Substances Extracted from Purple Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea L.) Growing in the Kemerovo Region: Functional Foods Application. Foods Raw Mater. 2019, 7, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazami, Y.; Gulledge, T.V.; Laster, S.M.; Pierce, J.G. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of a Series of Fatty Acid Amides from Echinacea. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 3091–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, I.; Cheetham, J.J.; Arnason, J.T.; Yack, J.E.; Smith, M.L. Alkamides from Echinacea Disrupt the Fungal Cell Wall-Membrane Complex. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chicca, A.; Raduner, S.; Pellati, F.; Strompen, T.; Altmann, K.-H.; Schoop, R.; Gertsch, J. Synergistic Immunomopharmacological Effects of N-Alkylamides in Echinacea Purpurea Herbal Extracts. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, L.J.; Nair, M.G.; Rana, J.; Dewitt, D.L. Bioactivity of Alkamides Isolated from Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench. Phytomedicine 2002, 9, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, H.N.; Kim, Y.-S.; Park, S.-Y.; Paek, K.-Y. Biotechnological Production of Caffeic Acid Derivatives from Cell and Organ Cultures of Echinacea Species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 7707–7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisavljević, I.; Stojičević, S.; Veličković, D.; Veljković, V.; Lazić, M. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea L.) Extracts Obtained by Classical and Ultrasound Extraction. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2009, 17, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-D.; Sung, J.-M.; Chen, C.-L. Effect of Drying and Storage Conditions on Caffeic Acid Derivatives and Total Phenolics of Echinacea Purpurea Grown in Taiwan. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choffe, K.L.; Victor, J.M.R.; Murch, S.J.; Saxena, P.K. In Vitro Regeneration of Echinacea purpurea L.: Direct Somatic Embryogenesis and Indirect Shoot Organogenesis in Petiole Culture. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2000, 36, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Neamati, N.; Zhao, H.; Kiryu, Y.; Turpin, J.A.; Aberham, C.; Strebel, K.; Kohn, K.; Witvrouw, M.; Pannecouque, C.; et al. Chicoric Acid Analogues as HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 1401–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, C.; Martins, N.; Carvalho, A.M.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phytopharmacologic Preparations as Predictors of Plant Bioactivity: A Particular Approach to Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench Antioxidant Properties. Nutrition 2016, 32, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facino, R.M.; Carini, M.; Aldini, G.; Saibene, L.; Pietta, P.; Mauri, P. Echinacoside and Caffeoyl Conjugates Protect Collagen from Free Radical-Induced Degradation: A Potential Use of Echinacea Extracts in the Prevention of Skin Photodamage. Planta Med. 1995, 61, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.-L.; Chiu, C.-C.; Yi-Fu Chen, J.; Chan, K.-C.; Lin, S.-D. Cytotoxic Effects of Echinacea Purpurea Flower Extracts and Cichoric Acid on Human Colon Cancer Cells through Induction of Apoptosis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-A.; Wu, C.-H.; Murthy, H.N.; Hahn, E.-J.; Paek, K.-Y. Application of an Airlift Bioreactor System for the Production of Adventitious Root Biomass and Caffeic Acid Derivatives of Echinacea Purpurea. Biotechnol. Bioproc. E 2009, 14, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Proksch, A. An Immunostimulating Active Principle from Echinacea Purpurea. Z Angew. Phytother. 1981, 2, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kaarlas, M.; Yu, H. Popularity, Diversity, and Quality of Echinacea. In Echinacea; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 143–166. ISBN 0-429-21569-X. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, T.K. Echinacea Purpurea. In Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 7, Flowers; Lim, T.K., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 340–371. ISBN 978-94-007-7395-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino, R.; Malvagna, P.; Spina, E.; Giori, A.; Fuzzati, N.; Anelli, A.; Garozzo, D.; Impallomeni, G. Structural Analysis of the Polysaccharides from Echinacea Angustifolia Radix. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 65, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B.; Williams, C.A. Phytochemistry of the Genus Echinacea. In Echinacea; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 71–88. ISBN 0-429-21569-X. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.C. Echinacea: A Miracle Herb against Aging and Cancer? Evidence In Vivo in Mice. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2005, 2, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.C.; Yu, H. Echinacea: The Genus Echinacea; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-203-02269-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Sharif, K.O.; Tufekci, E.F.; Ustaoglu, B.; Altunoglu, Y.C.; Zengin, G.; Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; Guney, K.; Baloglu, M.C. Anticancer and Biological Properties of Leaf and Flower Extracts of Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench. Food Biosci. 2021, 41, 101005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Xu, T.; Li, Q.; Yang, F.; Wang, C.; Huang, T.; Hao, Z. Polysaccharide from Echinacea Purpurea Reduce the Oxidant Stress in Vitro and in Vivo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, R.A.; Torres, A.R.; Warren, R.P.; Caldwell, V.D.; Hughes, B.G. Echinacea-Induced Cytokine Production by Human Macrophages. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1997, 19, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luettig, B.; Steinmüller, C.; Gifford, G.E.; Wagner, H.; Lohmann-Matthes, M.-L. Macrophage Activation by the Polysaccharide Arabinogalactan Isolated From Plant Cell Cultures of Echinacea Purpurea. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1989, 81, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, B. Medicinal Properties of Echinacea: A Critical Review. Phytomedicine 2003, 10, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, K.I.; Mead, M.N. Immune System Effects of Echinacea, Ginseng, and Astragalus: A Review. Integr. Cancer 2003, 2, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raso, G.M.; Pacilio, M.; Di Carlo, G.; Esposito, E.; Pinto, L.; Meli, R. In-Vivo and in-Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Echinacea Purpurea and Hypericum Perforatum. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2002, 54, 1379–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalanathan, S.; Kang, L.; Amiguet, V.T.; Livesey, J.; Arnason, J.T.; Hudson, J. Echinacea Purpurea. Aerial Parts Contain Multiple Antiviral Compounds. Pharm. Biol. 2005, 43, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Niu, F.; Xie, Y.; Xie, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wan, X. A Review: Natural Polysaccharides from Medicinal Plants and Microorganisms and Their Anti-Herpetic Mechanism. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellati, F.; Epifano, F.; Contaldo, N.; Orlandini, G.; Cavicchi, L.; Genovese, S.; Bertelli, D.; Benvenuti, S.; Curini, M.; Bertaccini, A.; et al. Chromatographic Methods for Metabolite Profiling of Virus- and Phytoplasma-Infected Plants of Echinacea Purpurea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 10425–10434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaverková, S.; Mikulásová, M.; Habán, M.; Tekel’, J.; Hollá, M.; Otepka, P. Variability of the Essential Oil from Three Sorts of Echinacea MOENCH Genus during Ontogenesis. Ceska Slov. Farm. 2007, 56, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R.; Remiger, P.; Wagner, H. Alkamides from the Roots of Echinacea Purpurea. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 2339–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balciunaite, G.; Haimi, P.-J.; Mikniene, Z.; Savickas, G.; Ragazinskiene, O.; Juodziukyniene, N.; Baniulis, D.; Pangonyte, D. Identification of Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench Root LysM Lectin with Nephrotoxic Properties. Toxins 2020, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coss, E.; Kealey, C.; Brady, D.; Walsh, P. A Laboratory Investigation of the Antimicrobial Activity of a Selection of Western Phytomedicinal Tinctures. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 19, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Samadi, A.; Sepehr, E.; Rahimi, A.; Shabala, S. Optimizing Hydroponic Culture Media and NO3−/NH4+ Ratio for Improving Essential Oil Compositions of Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea L.). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Mnayer, D.; Morais-Braga, M.F.B.; Carneiro, J.N.P.; Bezerra, C.F.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Salehi, B.; Martorell, M.; del Mar Contreras, M.; Soltani-Nejad, A.; et al. Echinacea Plants as Antioxidant and Antibacterial Agents: From Traditional Medicine to Biotechnological Applications. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indras, D.M.; Marek, C.B.; Penteado, A.J.; Ferreira, F.S.; Silva, F.C.; Itinose, A.M. Evaluation of the Toxic Effects of the Bottled Medicine (Garrafada) Containing the Echinacea Purpurea, Annona Muricata, Tabebuia Avellanedae, Pterodon Emarginatus and Uncaria Tomentosa in Rats. JMPR 2020, 14, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyalambisa, M.; Oyemitan, I.A.; Matewu, R.; Oyedeji, O.O.; Oluwafemi, O.S.; Songca, S.P.; Nkeh-Chungag, B.N.; Oyedeji, A.O. Volatile Constituents and Biological Activities of the Leaf and Root of Echinacea Species from South Africa. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deqiang, Y.; Yi, Y.; Ling, J.; Yuling, T.; Xiumei, Y.; Fang, H.; Zhongwen, X. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Essential Oil in Echinacea purpurea L. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 26, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Noorolahi, Z.; Sahari, M.A.; Barzegar, M.; Doraki, N.; Naghdi Badi, H. Evaluation Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Effects of Cinnamon Essential Oil and Echinacea Extract in Kolompe. J. Med. Plants 2013, 12, 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Teke, M.A.; Mutlu, Ç. Insecticidal and Behavioral Effects of Some Plant Essential Oils against Sitophilus granarius L. and Tribolium Castaneum (Herbst). J. Plant. Dis. Prot. 2021, 128, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Wu, C.-H.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Chang, G.-N.; Chang, X.-J.; Lian, M.-L. Methyl Jasmonate Elicits Enhancement of Bioactive Compound Synthesis in Adventitious Root Co-Culture of Echinacea Purpurea and Echinacea Pallida. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2022, 58, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araim, G.; Saleem, A.; Arnason, J.T.; Charest, C. Root Colonization by an Arbuscular Mycorrhizal (AM) Fungus Increases Growth and Secondary Metabolism of Purple Coneflower, Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 2255–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualandi, R. Fungal Endophytes Enhance Growth and Production of Natural Products in Echinacea Purpurea (Moench.). Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gualandi, R.J.; Augé, R.M.; Kopsell, D.A.; Ownley, B.H.; Chen, F.; Toler, H.D.; Dee, M.M.; Gwinn, K.D. Fungal Mutualists Enhance Growth and Phytochemical Content in Echinacea Purpurea. Symbiosis 2014, 63, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajagha, R.I.; Kirici, S.; Tabrizi, L.; Asgharzadeh, A.; Hamidi, A. Evaluation of Growth and Yield of Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea L.) in Response to Biological and Chemical Fertilizers. JAS 2017, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attarzadeh, M.; Balouchi, H.; Rajaie, M.; Movahhedi Dehnavi, M.; Salehi, A. Growth and Nutrient Content of Echinacea Purpurea as Affected by the Combination of Phosphorus with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus and Pseudomonas Florescent Bacterium under Different Irrigation Regimes. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamokou, J.; Mbaveng, A.; Kuete, V. Antimicrobial Activities of African Medicinal Spices and Vegetables. In Medicinal Spices and Vegetables from Africa; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 207–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cristea, V. Plante Vasculare: Diversitate, Sistematica, Ecologie Si Importanta; Presa Universitara Clujeana: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2014; ISBN 978-973-595-648-6. [Google Scholar]

- Duc, N.H.; Vo, A.T.; Haddidi, I.; Daood, H.; Posta, K. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Improve Tolerance of the Medicinal Plant Eclipta prostrata (L.) and Induce Major Changes in Polyphenol Profiles under Salt Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 612299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheyri, Z.; Moghaddam, M.; Farhadi, N. Inoculation Efficiency of Different Mycorrhizal Species on Growth, Nutrient Uptake, and Antioxidant Capacity of Calendula officinalis L.: A Comparative Study. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 1160–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, M.L.; Rola, K.; Zubek, S. The Growth and Phosphorus Acquisition of Invasive Plants Rudbeckia Laciniata and Solidago Gigantea Are Enhanced by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Mycorrhiza 2017, 27, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johny, L.; Cahill, D.M.; Adholeya, A. AMF Enhance Secondary Metabolite Production in Ashwagandha, Licorice, and Marigold in a Fungi-Host Specific Manner. Rhizosphere 2021, 17, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avio, L.; Maggini, R.; Ujvári, G.; Incrocci, L.; Giovannetti, M.; Turrini, A. Phenolics Content and Antioxidant Activity in the Leaves of Two Artichoke Cultivars Are Differentially Affected by Six Mycorrhizal Symbionts. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 264, 109153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lazzari Almeida, C.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F.; de Andrade, S.A.L. Mycorrhizal Influence on the Growth and Bioactive Compounds Composition of Two Medicinal Plants: Mikania Glomerata Spreng. and Mikania Laevigata Sch. Bip. Ex Baker (Asteraceae). Braz. J. Bot. 2018, 41, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avio, L.; Sbrana, C.; Giovannetti, M.; Frassinetti, S. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Affect Total Phenolics Content and Antioxidant Activity in Leaves of Oak Leaf Lettuce Varieties. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 224, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, R.; Szabo, K.; Abranko, L.; Rendes, K.; Füzy, A.; Takács, T. Effect of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on the Growth and Polyphenol Profile of Marjoram, Lemon Balm, and Marigold. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 3733–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaingankar, J.; Rodrigues, B. Screening for Efficient AM (Arbuscular Mycorrhizal) Fungal Bioinoculants for Two Commercially Important Ornamental Flowering Plant Species of Asteraceae. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2012, 28, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedone, L.; Ruta, C.; De Cillis, F.; De Mastro, G. Effects of Septoglomus Viscosum Inoculation on Biomass Yield and Steviol Glycoside Concentration of Some Stevia Rebaudiana Chemotypes. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 262, 109026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domokos, E.; Jakab-Farkas, L.; Darkó, B.; Bíró-Janka, B.; Mara, G.; Albert, C.; Balog, A. Increase in Artemisia Annua Plant Biomass Artemisinin Content and Guaiacol Peroxidase Activity Using the Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Rhizophagus Irregularis. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domokos, E.; Bíró-Janka, B.; Bálint, J.; Molnár, K.; Fazakas, C.; Jakab-Farkas, L.; Domokos, J.; Albert, C.; Mara, G.; Balog, A. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Rhizophagus Irregularis Influences Artemisia Annua Plant Parameters and Artemisinin Content under Different Soil Types and Cultivation Methods. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bączek, K.B.; Wiśniewska, M.; Przybył, J.L.; Kosakowska, O.; Węglarz, Z. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) Organic Cultivation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabar, R.S.; Moieni, A.; Monfared, S.R. Improving Biomass and Chicoric Acid Content in Hairy Roots of Echinacea purpurea L. Biologia 2019, 74, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Anand, G.; Gupta, P.; Mandal, S. Insight into the Mechanisms of Enhanced Production of Valuable Terpenoids by Arbuscular Mycorrhiza. Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, L.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.C.W.; Zhang, Y.; Reed, D.W.; Pollier, J.; Vande Casteele, S.R.F.; Inzé, D.; Covello, P.S.; Deforce, D.L.D.; Goossens, A. Dissection of the Phytohormonal Regulation of Trichome Formation and Biosynthesis of the Antimalarial Compound Artemisinin in Artemisia Annua Plants. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, V.P.; Kapoor, R. Enhanced Production of Steviol Glycosides in Mycorrhizal Plants: A Concerted Effect of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis on Transcription of Biosynthetic Genes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 89, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweiger, R.; Müller, C. Leaf Metabolome in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 26, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolfsson, L.; Nziengui, H.; Abreu, I.N.; Šimura, J.; Beebo, A.; Herdean, A.; Aboalizadeh, J.; Široká, J.; Moritz, T.; Novák, O.; et al. Enhanced Secondary- and Hormone Metabolism in Leaves of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Medicago Truncatula. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Hao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, X.; Xu, L.; Wu, S.; Zhao, A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, B. Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Facilitates the Accumulation of Glycyrrhizin and Liquiritin in Glycyrrhiza Uralensis under Drought Stress. Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashad, Y.; Aseel, D.; Hammad, S.; Elkelish, A. Rhizophagus Irregularis and Rhizoctonia Solani Differentially Elicit Systemic Transcriptional Expression of Polyphenol Biosynthetic Pathways Genes in Sunflower. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Upadhyay, S.; Wajid, S.; Ram, M.; Jain, D.C.; Singh, V.P.; Abdin, M.Z.; Kapoor, R. Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Increase Artemisinin Accumulation in Artemisia Annua by Higher Expression of Key Biosynthesis Genes via Enhanced Jasmonic Acid Levels. Mycorrhiza 2015, 25, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Karimzadeh, G.; Naghavi, M.R.; Naghdi Badi, H.; Rashidi Monfared, S. Expression of Key Genes Affecting Artemisinin Content in Five Artemisia Species. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilam, D.; Saifi, M.; Abdin, M.Z.; Agnihotri, A.; Varma, A. Endophytic Root Fungus Piriformospora Indica Affects Transcription of Steviol Biosynthesis Genes and Enhances Production of Steviol Glycosides in Stevia Rebaudiana. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 97, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).