Physiological, Biochemical, and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal the Potential Role of ABA in Dufulin-Induced Tomato Resistance to Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. Virus Inoculation and Dufulin Application

2.3. Protective Activity of Dufulin on ToBRFV

2.4. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and PCR Detection

2.5. Membrane Lipid Peroxidation Assays

2.6. Determination of Defense Enzyme Activity

2.7. Measurement of Photosynthetic Pigment Content

2.8. Quantification of Phytohormones

2.9. Transcriptomic Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

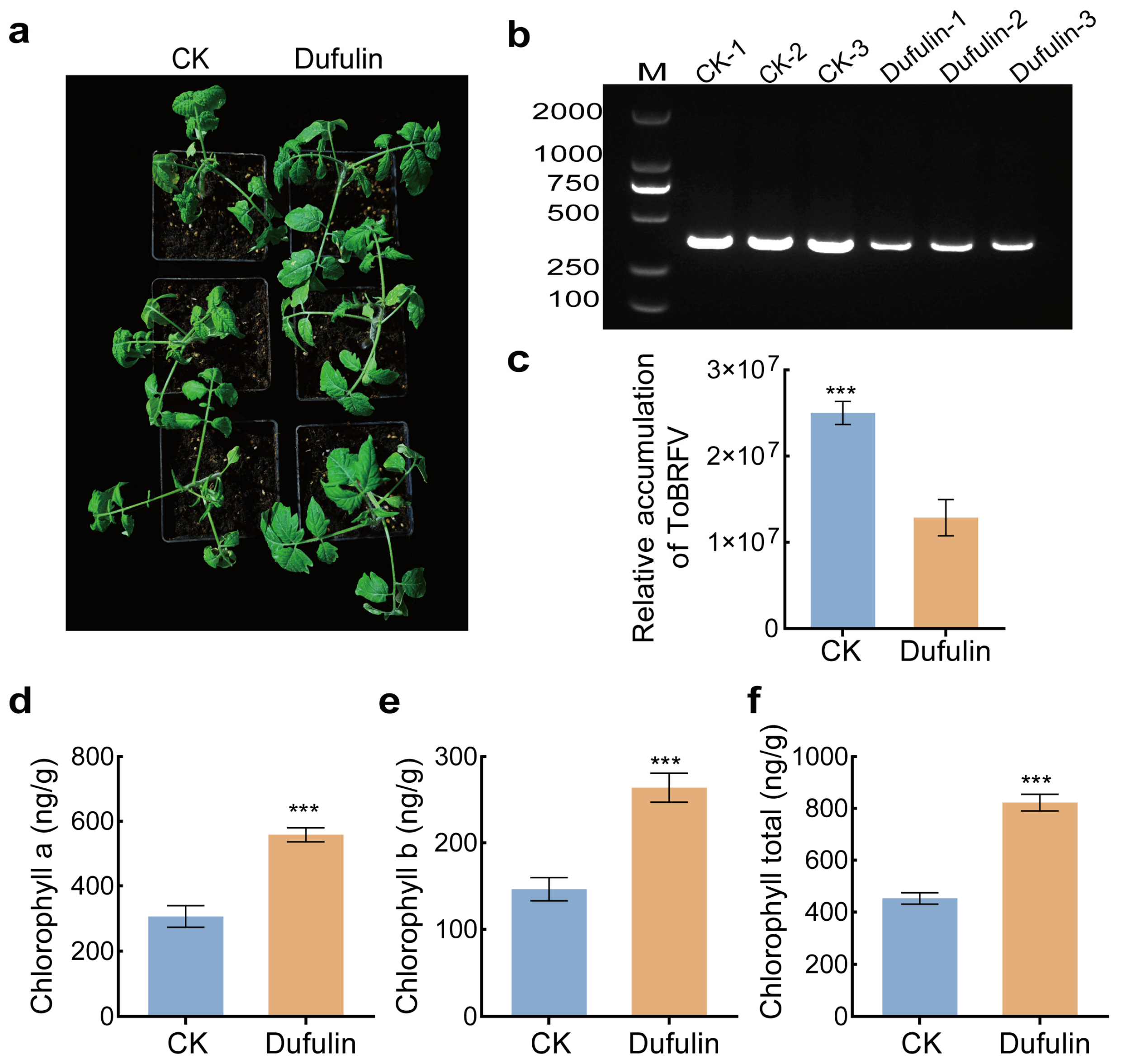

3.1. Effects of Dufulin Treatment on the Growth of Tomato Seedlings

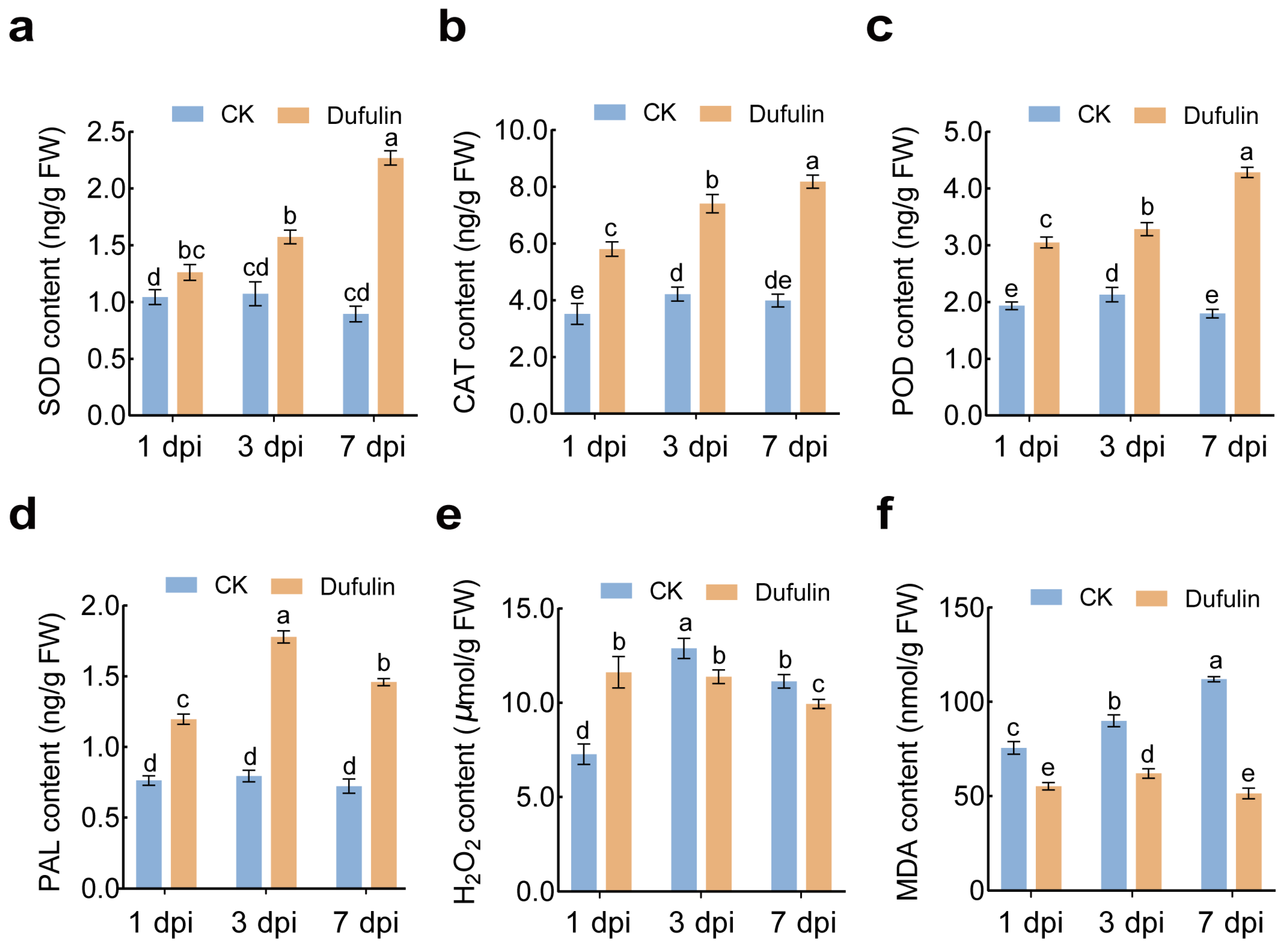

3.2. Physiological Changes in Tomato

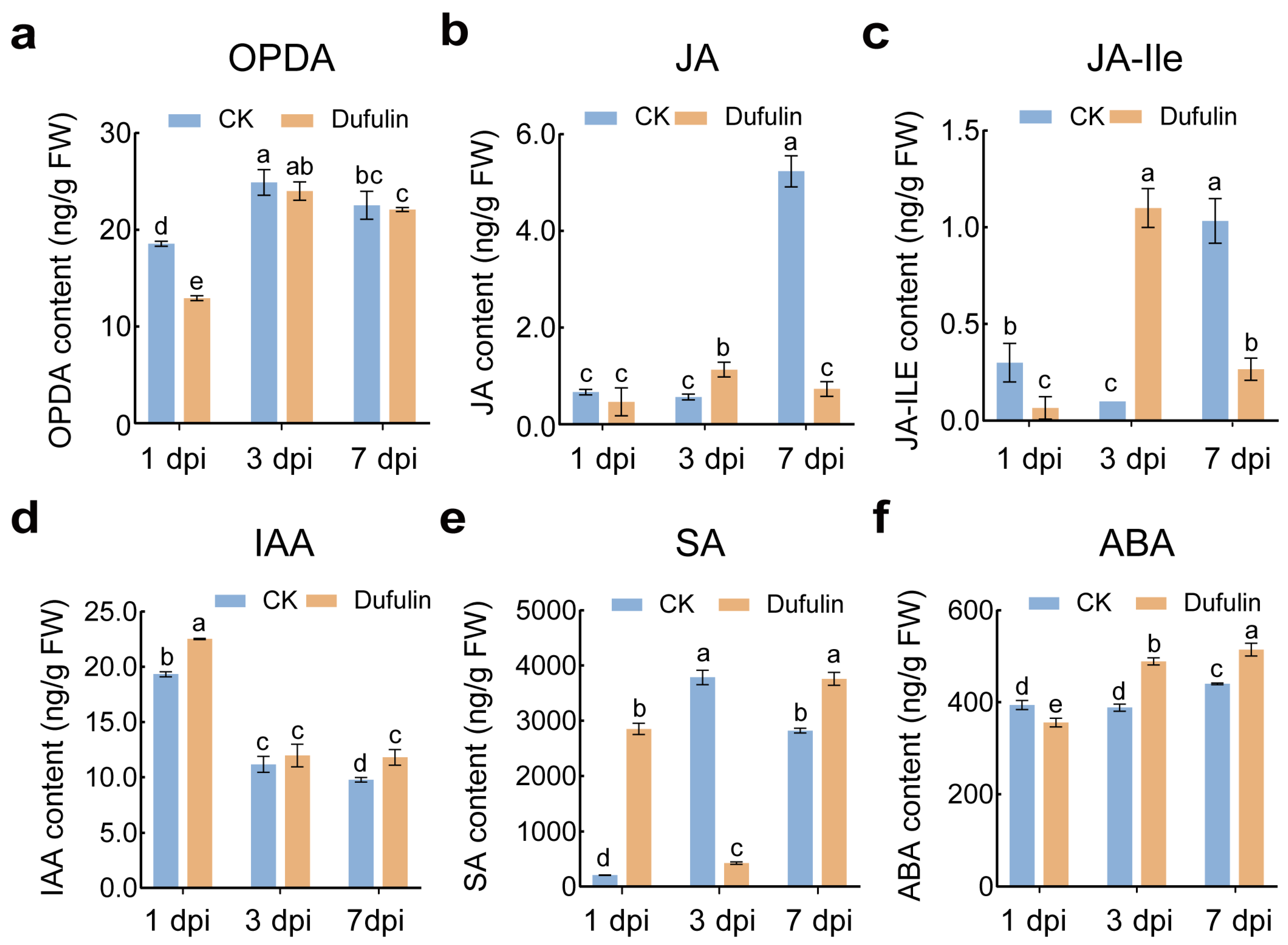

3.3. Changes in Phytohormones in Tomato Leaves

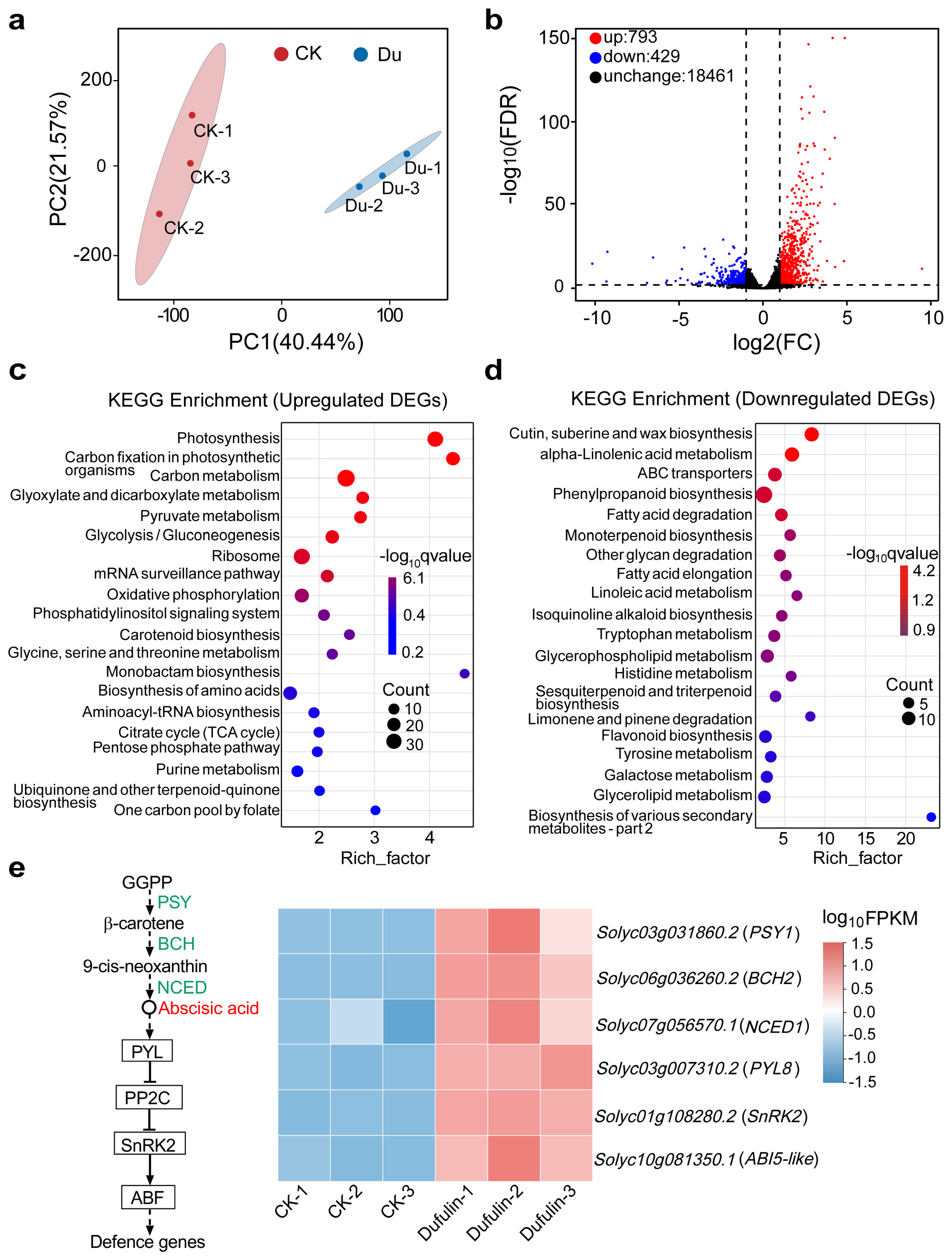

3.4. Transcript Diversity Analysis

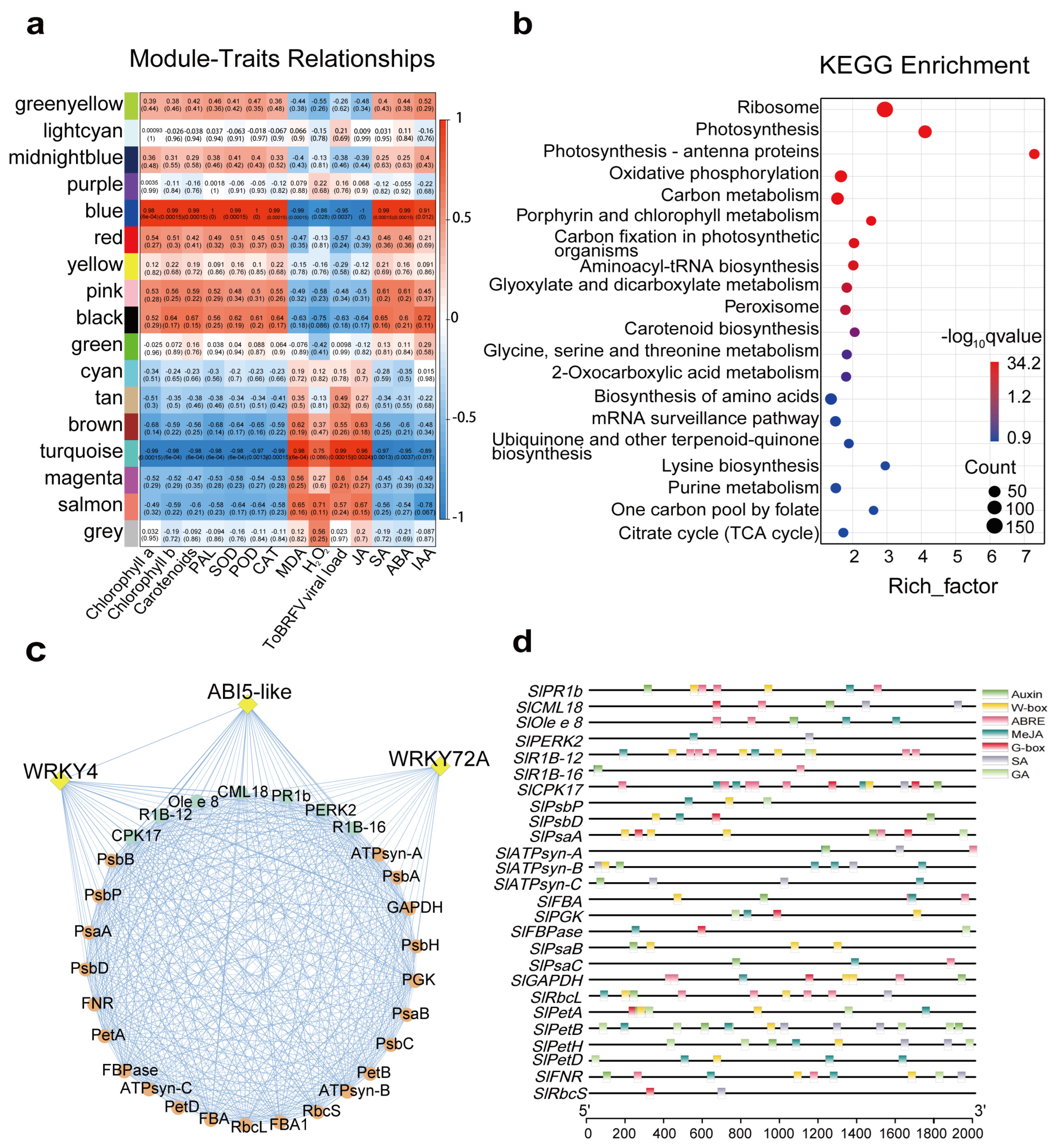

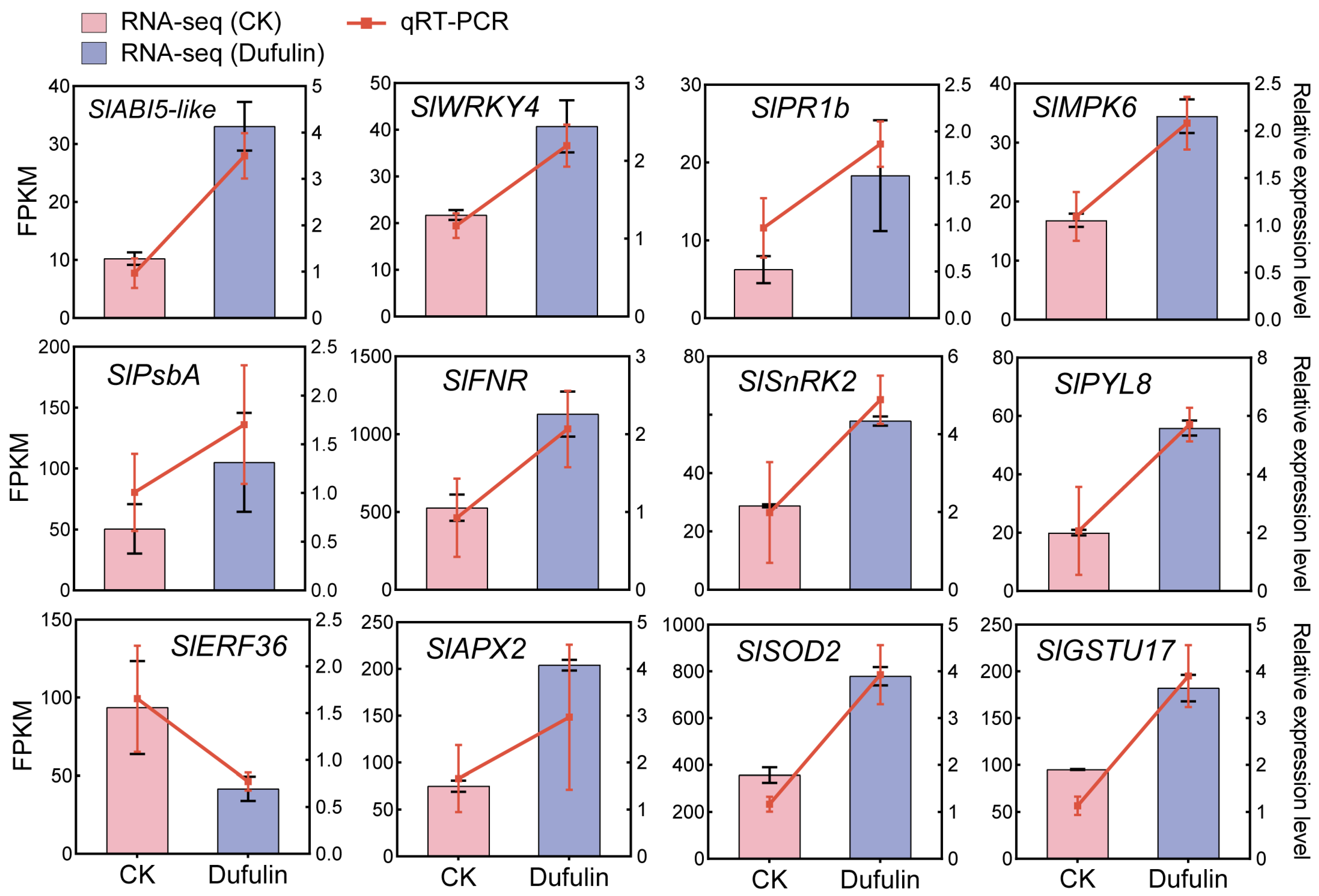

3.5. WGCNA Identified Candidate Genes Regulating Dufulin-Induced Resistance to ToBRFV

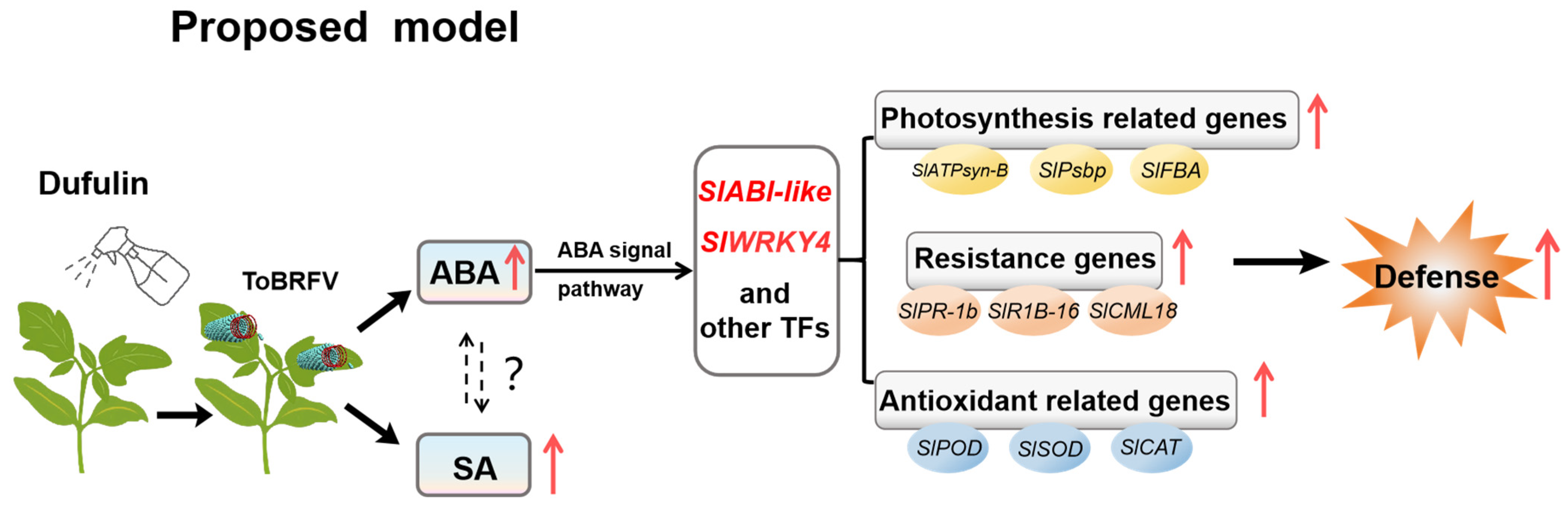

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caruso, A.G.; Bertacca, S.; Parrella, G.; Rizzo, R.; Davino, S.; Panno, S. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: A pathogen that is changing the tomato production worldwide. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2022, 181, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisi, Z.; Ghijselings, L.; Vogel, E.; Vos, C.; Matthijnssens, J. Single amino acid change in tomato brown rugose fruit virus breaks virus-specific resistance in new resistant tomato cultivar. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1382862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistical Database. 2025. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Topcu, Y.; Yildiz, K.; Kayikci, H.C.; Aydin, S.; Feng, Q.; Sapkota, M. Deciphering resistance to tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) using genome-wide association studies. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 341, 113968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fougere, G.; Xu, D.; Gaiero, J.; McCreary, C.; Marchand, G.; Despres, C.; Wang, A.; Fall, M.L.; Griffiths, J. Genomic diversity of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in Canadian greenhouse production systems. Viruses 2025, 17, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.M.; Abumuslem, M.; Turina, M.; Samarah, N.; Sulaiman, A.; Abu-Irmaileh, B.; Ata, Y. New weed hosts for tomato brown rugose fruit virus in wild mediterranean vegetation. Plants 2022, 11, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Santosa, A.I.; Çelik, A.; Koolivand, D. Revealing an Iranian isolate of tomato brown rugose fruit virus: Complete genome analysis and mechanical transmission. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, N.; Smith, E.; Reingold, V.; Bekelman, I.; Lapidot, M.; Levin, I.; Elad, N.; Tam, Y.; Sela, N.; Abu-Ras, A.; et al. A new Israeli Tobamovirus isolate infects tomato plants harboring Tm-22 resistance genes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davino, S.; Caruso, A.G.; Bertacca, S.; Barone, S.; Panno, S. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: Seed transmission rate and efficacy of different seed disinfection treatments. Plants 2020, 9, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, S.; Giovanni Caruso, A.; Barone, S.; Lo Bosco, G.; Rangel, E.A.; Davino, S. Spread of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in Sicily and evaluation of the spatiotemporal dispersion in experimental conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.; Nourinejhad Zarghani, S.; Liedtke, S.; Kroschewski, B.; Büttner, C.; Bandte, M. Analysis of the spatial dispersion of tomato brown rugose fruit virus on surfaces in a commercial tomato production site. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehle, N.; Bačnik, K.; Bajde, I.; Brodarič, J.; Fox, A.; Gutiérrez-Aguirre, I.; Kitek, M.; Kutnjak, D.; Loh, Y.L.; Maksimović Carvalho Ferreira, O.; et al. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in aqueous environments-survival and significance of water-mediated transmission. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1187920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladokun, J.O.; Halabi, M.H.; Barua, P.; Nath, P.D. Tomato brown rugose fruit disease: Current distribution, knowledge and future prospects. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pares, R.D.; Gunn, L.V.; Keskula, E.N. The role of infective plant debris, and its concentration in soil, in the ecology of tomato mosaic tobamovirus—A non-vectored plant virus. J. Phytopathol. 1996, 144, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitzky, N.; Smith, E.; Lachman, O.; Luria, N.; Mizrahi, Y.; Bakelman, H.; Sela, N.; Laskar, O.; Milrot, E.; Dombrovsky, A. The bumblebee Bombus terrestris carries a primary inoculum of tomato brown rugose fruit virus contributing to dsease spread in tomatoes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.; Sede, A.R.; Levanova, A.A.; Leibman-Markus, M.; Gupta, R.; Mishra, R.; Hak, H.; Bar, M.; Poranen, M.M.; Heinlein, M.; et al. Control of tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) in tomato plants using in vivo synthesized dsRNA. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 28, eraf293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yang, X.; Jia, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Guo, W. Natural product chelerythrine induces plant resistance through activating defensive reactions. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 7896–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, T.; Geng, R.; Cao, J.; Zhang, W.; Tan, X. Plant disease resistance-related signaling pathways: Recent progress and future prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Shi, F. Plant immunity inducer development and application. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2017, 30, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, X.; Ye, Q.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, S.; Yu, Z.; Wang, W. Nonenantioselective environmental behavior of a chiral antiviral pesticide dufulin in aerobic soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Ding, Y.; Wu, J.; Hu, D.; Song, B. Studies of binding interactions between Dufulin and southern rice black-streaked dwarf virus P9-1. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 3629–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xie, X.; Gao, D.; Chen, K.; Chen, Z.; Jin, L.; Li, X.; Song, B. Dufulin intervenes the viroplasmic proteins as the mechanism of action against southern rice black-streaked dwarf virus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11380–11387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zeng, M.; Song, B.; Hou, C.; Hu, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Fan, H.; Bi, L.; Liu, J.; et al. Dufulin activates HrBP1 to produce antiviral responses in tobacco. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Tang, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Du, J.; Yan, S.; Zhang, D.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, F. Dufulin impacts plant defense against tomato yellow leaf curl virus infecting tomato. Viruses 2024, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, N.; Chanda, B.; Gilliard, A.; Shi, A.; Ling, K.-S. Evaluation of tomato germplasm against tomato brown rugose fruit virus and identification of resistance in Solanum pimpinellifolium. Plants 2024, 13, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Kim, E.-D.; Chen, Z.J. Chlorophyll and starch assays. Protoc. Exch. 2009, 488, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Bian, J.; Xue, N.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J. Inter-species mRNA transfer among green peach aphids, dodder parasites, and cucumber host plants. Plant Divers. 2021, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yan, L.; Liu, Q.; Tian, R.; Wang, S.; Umer, M.F.; Jalil, M.J.; Lohani, M.N.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; et al. Integration of Transcriptomics, metabolomics, and hormone analysis revealed the formation of lesion spots inhibited by GA and CTK was related to cell death and disease resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Dufulin enhances salt resistance of rice. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 188, 105252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Guo, Z. WRKY transcription factors: Evolution, binding, and action. Phytopathol. Res. 2019, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Fujita, Y.; Sayama, H.; Kidokoro, S.; Maruyama, K.; Mizoi, J.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. AREB1, AREB2, and ABF3 are master transcription factors that cooperatively regulate ABRE-dependent ABA signaling involved in drought stress tolerance and require ABA for full activation. Plant J. 2010, 61, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Zhang, Z.; He, J.; Zhang, P.; Ou, X.; Li, T.; Niu, L.; Nan, Q.; Niu, Y.; He, W.; et al. Arabidopsis ADF5 promotes stomatal closure by regulating actin cytoskeleton remodeling in response to ABA and drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 70, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gómez, P. Special Issue: Advances in plant virus diseases and virus-induced resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.G.; Panno, S.; Ragona, A.; Peiró, R.; Vetrano, F.; Moncada, A.; Miceli, A.; La Marra, C.M.; Galipienso, L.; Rubio, L.; et al. Screening local Sicilian tomato ecotypes to evaluate the rsponse of tomato brown rugose fruit virus infection. Agronomy 2024, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D.; Chakraborty, S. Chloroplast: The Trojan horse in plant-virus Interaction. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 19, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Hong, Y.; Liu, Y. Chloroplast in plant-virus interaction. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Y.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Q.; Song, Z.; Zhou, C. Transcriptome analysis of Citrus limon infected with citrus yellow vein clearing virus. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Cong, Y.; Zhu, P.; Xing, J.; Cui, J.; Xu, W.; Shi, Q.; Diao, M.; Liu, H. Ascorbic acid-induced photosynthetic adaptability of processing tomatoes to salt stress probed by fast OJIP fluorescence rise. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 594400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwalya, J.; Alazem, M.; Kim, K. Photosynthesis-related genes induce resistance against soybean mosaic virus: Evidence for involvement of the RNA silencing pathway. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2021, 23, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; He, H.; Hu, D.; Song, B. Defense mechanism of Capsicum annuum L. Infected with pepper mild mottle virus induced by vanisulfane. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 3618–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohoursoleimani, R.; Aeini, M.; Parizipour, M.H.G. Effects of abiotic and biotic elicitors on tomato resistance to tomato brown rugose fruit virus. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yan, H.; Ren, X.; Tang, R.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J. Berberine induces resistance against tobacco mosaic virus in tobacco. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 76, 1804–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, S.; Zhang, W.; Gan, X. Novel 1-Indanone derivatives containing oxime and oxime ether moieties as immune activator to resist plant virus. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 2686–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Shi, J.; Yu, L.; Liu, D.; Gan, X.; Song, B.; Hu, D. Design, synthesis, antiviral bioactivity, and defense mechanisms of novel dithioacetal derivatives bearing a strobilurin moiety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 5335–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, M.; He, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Tang, Y.; Wang, R.; et al. Functional analysis of the pathogenesis-related protein 1 (CaPR1) gene in the pepper response to chilli veinal mottle virus (ChiVMV) infection. Viruses 2025, 17, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, J.K.; Rawat, S.; Luthra, S.K.; Zinta, R.; Sahu, S.; Varshney, S.; Kumar, V.; Dalamu, D.; Mandadi, N.; Kumar, M.; et al. Genome sequence analysis provides insights on genomic variation and late blight resistance genes in potato somatic hybrid (parents and progeny). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Peng, H.; Zhu, X.; Huang, J.; Ran, M.; Ma, L.; Sun, X. A chitosan-coated lentinan-loaded calcium alginate hydrogel induces broad-spectrum resistance to plant viruses by activating Nicotiana benthamiana calmodulin-like (CML) protein 3. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 3592–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yuan, R.; Zhao, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Lamlom, S.F.; Zhang, B.; et al. Comprehensively characterize the soybean CAM/CML gene family, as it provides resistance against both the soybean mosaic virus and Cercospora sojina pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1633325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Su, J.; Xue, H.; Sun, Y.; Lian, M.; Ma, J.; Lei, T.; He, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, S.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analyses of ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) genes in Citrus sinensis reveal CsABI5-5 confers dual resistance to Huanglongbing and citrus canker. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Ling, L.; Han, D.; Huang, L.; Gao, C.; Yang, C.; Lai, J. ABA INSENSITIVE 5 confers geminivirus resistance via suppression of the viral promoter activity in plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 275, 153742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Xing, S.; Li, T.; Zhao, P.; Guo, J.-W.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S. Physiological, Biochemical, and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal the Potential Role of ABA in Dufulin-Induced Tomato Resistance to Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV). Horticulturae 2026, 12, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010060

Wang J, Xing S, Li T, Zhao P, Guo J-W, Xia Y, Liu Y, Wu S. Physiological, Biochemical, and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal the Potential Role of ABA in Dufulin-Induced Tomato Resistance to Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV). Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jinfeng, Shijun Xing, Tao Li, Peiyan Zhao, Jian-Wei Guo, Yuqi Xia, Yating Liu, and Shibo Wu. 2026. "Physiological, Biochemical, and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal the Potential Role of ABA in Dufulin-Induced Tomato Resistance to Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV)" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010060

APA StyleWang, J., Xing, S., Li, T., Zhao, P., Guo, J.-W., Xia, Y., Liu, Y., & Wu, S. (2026). Physiological, Biochemical, and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal the Potential Role of ABA in Dufulin-Induced Tomato Resistance to Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV). Horticulturae, 12(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010060