In Vivo Screening of Rhizobacteria Against Phytophthora capsici and Bacillus subtilis Induced Defense Gene Expression in Chili Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbiological Material

2.2. Inoculum Preparation

2.3. Plant Growth Conditions and Inoculation

2.4. In Vivo Effect of Rhizobacteria on the Severity of P. capsici-Induced Disease

2.5. Accumulation of Defense Gene Transcripts in Chili Pepper Plants

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

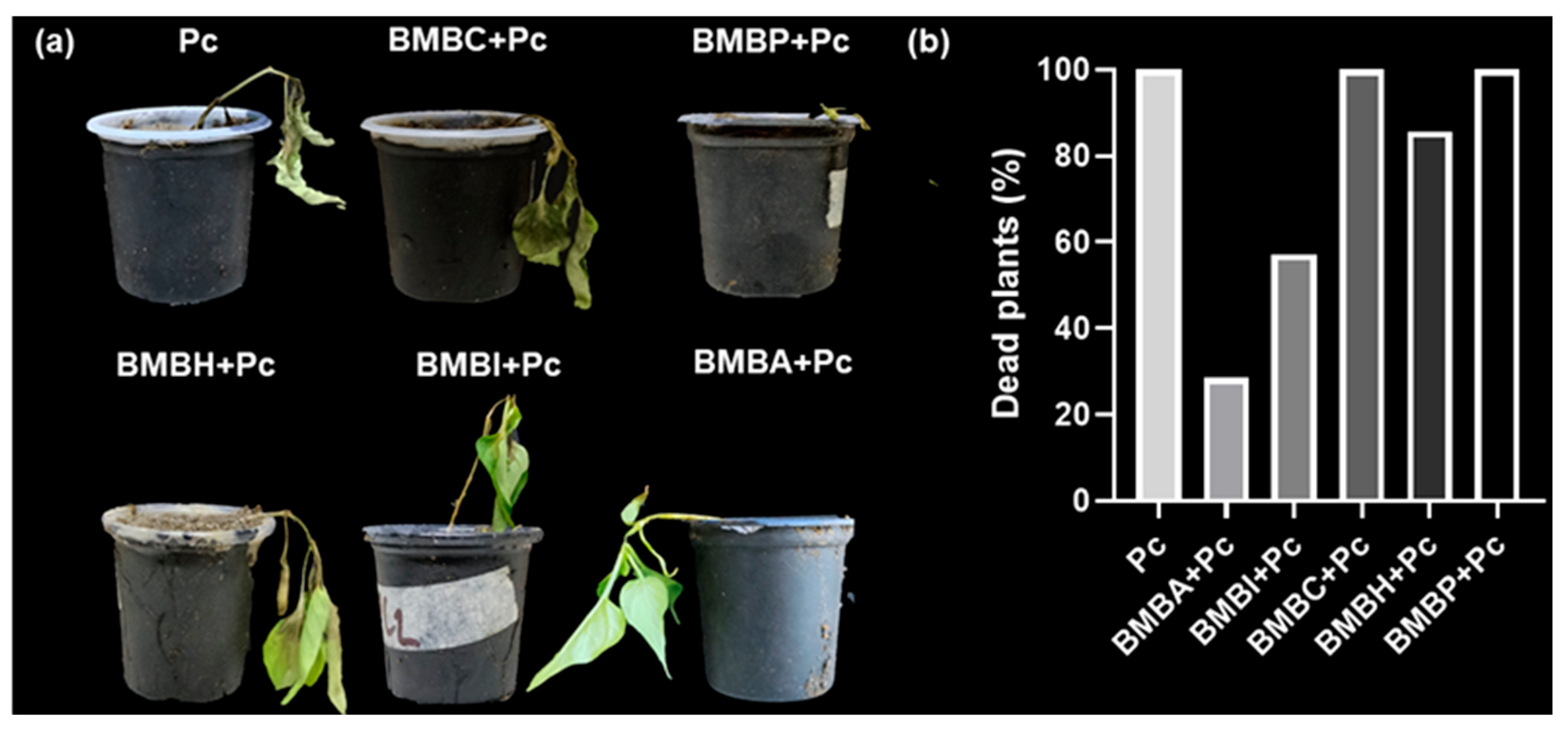

3.1. In Vivo Effect of Rhizobacteria on the Severity of P. capsici Induced Disease

3.2. Mortality Caused by P. capsici

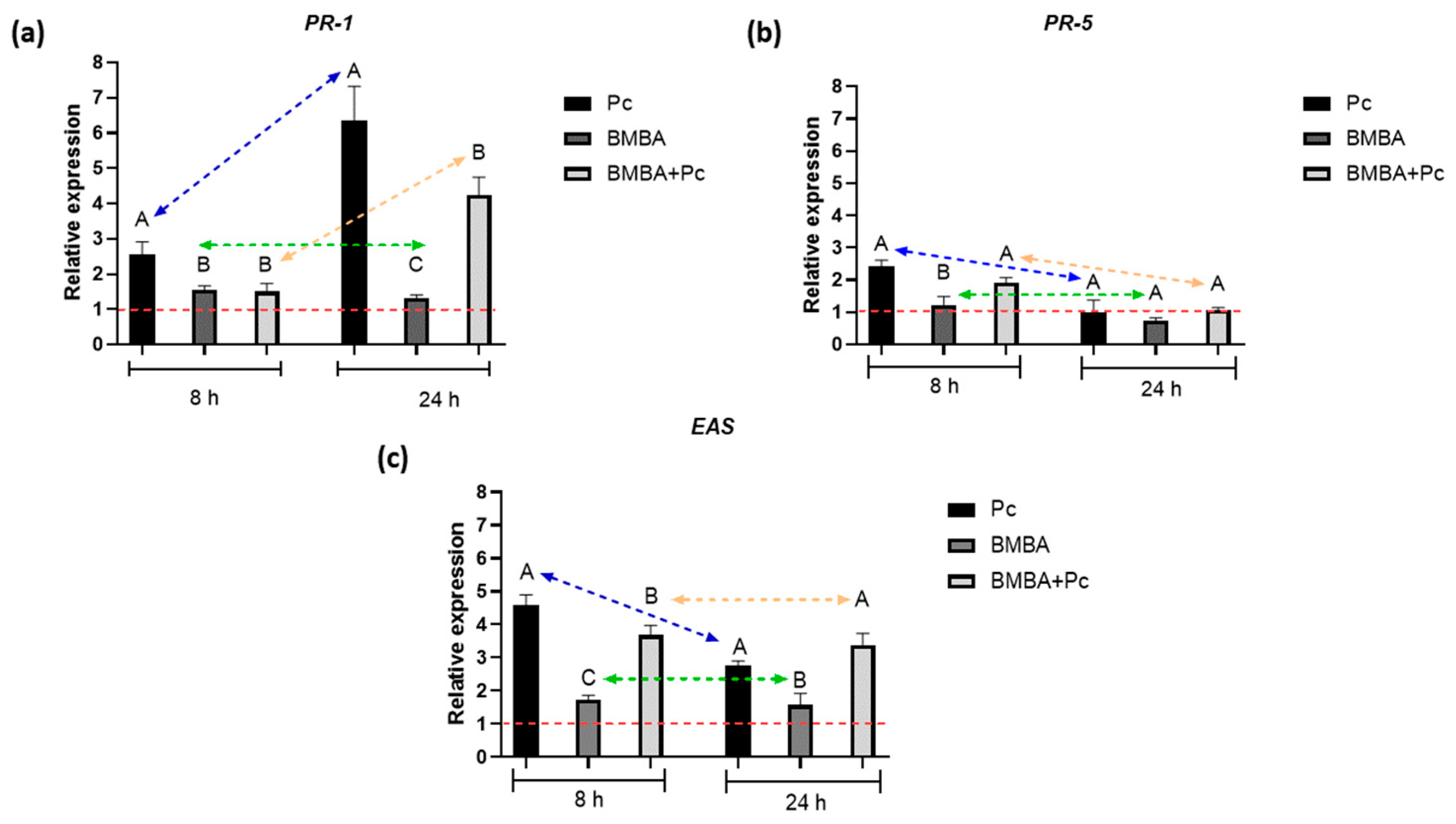

3.3. Accumulation of Defense Related Gene Transcripts in Chili Pepper Plants Bacterized and Challenged with Phytophthora capsici

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olatunji, T.L.; Afolayan, A.J. The suitability of chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) for alleviating human micronutrient dietary deficiencies: A Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Morrillo, A.A.; Monteros-Altamirano, Á.; Reis, A.; Garcés-Fiallos, F.R. Phytophthora capsici on Capsicum Plants: A destructive pathogen in chili and pepper crops. In Capsicum–Current Trends and Perspectives; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.D.; McGovern, R.J.; Kucharek, T.A.; Mitchell, D.J. Vegetable Diseases Caused by Phytophthora capsici in Florida 1; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Axol, J.R.; Miranda-Solares, A.K.; Zúñiga-Aguilar, J.J.; Solano-Báez, A.R.; Llarena-Hernández, R.C.; Rojas-Avelizapa, L.I.; Núñez-Pastrana, R. Chitosan mitigates Phytophthora blight in chayote (Sechium edule) by direct pathogen inhibition and systemic resistance induction. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltos, L.A.; Monteros-Altamirano, Á.; Reis, A.; Garcés-Fiallos, F.R. Phytophthora capsici: The diseases it causes and management strategies to produce healthier vegetable crops. Hortic. Bras. 2022, 40, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavelu, R.; Gopi, M. Field suppression of Fusarium wilt disease in banana by the combined application of native endophytic and rhizospheric bacterial isolates possessing multiple functions. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2015, 54, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M.U.; Awan, M.F.; Fatima, K.; Tahir, M.S.; Ali, Q.; Rashid, B.; Rao, A.Q.; Nasir, I.A.; Husnain, T. Genetinė ir biologinė Phytophthora capsici kontrolė aitriosios paprikos (Capsicum annuum L.) augalams: Apžvalga. Zemdirbyste 2016, 103, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchenger, D.W.; Lamour, K.H.; Bosland, P.W. Challenges and strategies for breeding resistance in Capsicum annuum to the multifarious pathogen, Phytophthora capsici. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandana, V.V.; Suseela Bhai, R.; Ramakrishnan Nair, R.; Azeez, S. Role of cell wall and cell membrane integrity in imparting defense response against Phytophthora capsici in black pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 154, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, T.; Wu, T.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Du, H.; Xu, X.; Xie, D.; Xu, X.M. The dynamic transcriptome of pepper (Capsicum annuum) whole roots reveals an important role for the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway in root resistance to Phytophthora capsici. Gene 2020, 728, 144288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadbagheri, L.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.; Abdossi, V.; Naderi, D. Genetic diversity and biochemical analysis of Capsicum annuum (bell pepper) in response to root and basal rot disease, Phytophthora capsici. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Zhou, K.H.; Chen, X.J.; Huang, Y.Q.; Yuan, X.J.; Li, G.G.; Xie, Y.Y.; Fang, R. Transcriptome and metabolome analyses revealed the response mechanism of pepper roots to Phytophthora capsici Infection. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávez-Moctezuma, M.P.; Lozoya-Gloria, E. Plant cell reports biosynthesis of the sesquiterpenic phytoalexin capsidiol in elicited root cultures of chili pepper (Capsicum annuum). Plant Cell Rep. 1996, 15, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zou, C. Unveiling molecular mechanisms of pepper resistance to Phytophthora capsici through grafting using ITRAQ-based proteomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Luna, E.; Rojas-Martínez, R.I.; Reyes-Trejo, B.; Gómez-Rodríguez, O.; Zavaleta-Mejía, E. Mevalonate pathway genes expressed in chilli CM334 inoculated with Phytophthora capsici and infected by Nacobbus aberrans and Meloidogyne enterolobii. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 148, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, S.-I.; Baek, H.-K.; Oh, S.-K.; Kang, W.-H.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.M.; Seo, E.; Rose, J.K.C.; Kim, B.-D.; Choi, D. Use of a secretion trap screen in pepper following Phytophthora capsici infection reveals novel functions of secreted plant proteins in modulating cell death. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boava, L.P.; Cristofani-Yaly, M.; Stuart, R.M.; Machado, M.A. Expression of defense-related genes in response to mechanical wounding and Phytophthora parasitica infection in Poncirus trifoliata and Citrus sunki. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 76, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejano-Ramírez, V.; Valencia-Cantero, E. Cross-talk between iron deficiency response and defense establishment in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosier, A.; Medeiros, F.H.V.; Bais, H.P. Defining plant growth promoting rhizobacteria molecular and biochemical networks in beneficial plant-microbe interactions. Plant Soil. 2018, 428, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Galyamova, M.R.; Sedykh, S.E. Plant growth-promoting soil bacteria: Nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, and other biological activities. Plants 2023, 12, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F.X.; Hernandez, A.G.; Glick, B.R.; Rossi, M.J. The extreme plant-growth-promoting properties of pantoea phytobeneficialis MSR2 revealed by functional and genomic analysis. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 1341–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.K.; Singh, S.; Gupta, A.; Singh, U.B.; Brahmaprakash, G.P.; Saxena, A.K. Antagonistic potential of bacterial endophytes and induction of systemic resistance against collar rot pathogen Sclerotium rolfsii in tomato. Biol. Control 2019, 137, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Kim, B.S. Evaluation of Paenibacillus polymyxa strain SC09-21 for biocontrol of Phytophthora blight and growth stimulation in pepper plants. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2016, 41, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Exploring elicitors of the beneficial rhizobacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 to induce plant systemic resistance and their interactions with plant signaling pathways. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2018, 31, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkhalek, A.; Aseel, D.G.; Király, L.; Künstler, A.; Moawad, H.; Al-Askar, A.A. Induction of systemic resistance to tobacco mosaic virus in tomato through foliar application of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain TBorg1 culture filtrate. Viruses 2022, 14, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanogo, S. Response of chile pepper to Phytophthora capsici in relation to soil salinity. Plant Dis. 2004, 88, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Saavedra, D.L.; García-Neria, M.A.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Benzothiadiazole (BTH) induces resistance to pepper golden mosaic virus (PepGMV) in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Biol. Res. 2013, 46, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Neria, M.A.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Characterization of geminivirus resistance in an accession of Capsicum chinense Jacq. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.K.; Ma, L.; Yang, Z.X.; Bao, L.F.; Mo, M.H. Rhizosphere-associated microbiota strengthen the pathogenicity of Meloidogyne incognita on Arabidopsis thaliana. Agronomy 2024, 14, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Avilés, M.N.; García-Álvarez, M.; Ávila-Oviedo, J.L.; Hernández-Hernández, I.; Bautista-Ortega, P.I.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.I. Volatile organic compounds produced by Trichoderma asperellum with antifungal properties against Colletotrichum acutatum. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Oviedo, J.L.; Chávez-Avilés, M.N. Efecto de los extractos hexánicos obtenidos del cultivo individual y co-cultivo de Trichoderma sp. y Bacillus subtilis sobre el crecimiento de Colletotrichum acutatum in vitro. Mex. J. Biotechnol. 2025, 10, 15–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejano-Ramírez, V.; Ávila-Oviedo, J.L.; Campos-Mendoza, F.J.; Valencia-Cantero, E. Microbial volatile organic compounds: Insights into plant defense. Plants 2024, 13, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, K.; Das, S.N.; Podile, A.R. Induced defense in plants: A short overview. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 84, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Oviedo, J.L.; Méndez-Inocencio, C.; Rodríguez-Torres, M.D.; Angoa-Pérez, M.V.; Chávez-Avilés, M.N.; Martínez-Mendoza, E.K.; Oregel-Zamudio, E.; Villar-Luna, E. Antagonistic effects and volatile organic compound profiles of rhizobacteria in the biocontrol of Phytophthora capsici. Plants 2024, 13, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya-Hernández, A.I.; López-Carmona, D.; Jaramillo-López, P.; Fernández-Pavía, S.P.; Carreón-Abud, Y.; Fraire-Velázquez, S.; Larsen, J. Well known microbial plant growth promoters provoke plant growth suppression and increase chili pepper wilt caused by the root pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 167, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beskrovnaya, P.; Melnyk, R.A.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Higgins, M.A.; Song, Y.; Ryan, K.S.; Haney, C.H. Comparative genomics identified a genetic locus in plant associated Pseudomonas spp. that is necessary for induced systemic susceptibility. mBio 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ongena, M.; Duby, F.; Jourdan, E.; Beaudry, T.; Jadin, V.; Dommes, J.; Thonart, P. Bacillus subtilis M4 decreases plant susceptibility towards fungal pathogens by increasing host resistance associated with differential gene expression. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 67, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarate, S.I.; Kempema, L.A.; Walling, L.L. Silverleaf whitefly induces salicylic acid defenses and suppresses effectual jasmonic acid defenses. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Bonilla, L.D.; Betancourt-Jiménez, M.; Lozoya-Gloria, E. Local and systemic gene expression of sesquiterpene phytoalexin biosynthetic enzymes in plant leaves. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2008, 121, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhu, J.; Qian, N.; Guo, J.; Yan, C. Bacillus subtilis SL18r induces tomato resistance against Botrytis cinerea, involving activation of long non-coding RNA, MSTRG18363, to decoy MiR1918. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 634819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D.K.; Johri, B.N. Interactions of Bacillus spp. and plants—With special reference to induced systemic resistance (ISR). Microbiol. Res. 2009, 164, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaras, A.; Roumeliotis, E.; Ntasiou, P.; Karaoglanidis, G. Bacillus subtilis Mbi600 promotes growth of tomato plants and induces systemic resistance contributing to the control of soilborne pathogens. Plants 2021, 10, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvar, C.; Merino, F.; Díaz, J. Differential activation of defense-related genes in susceptible and resistant pepper cultivars infected with Phytophthora capsici. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajamanickam, S.; Nakkeeran, S. Flagellin of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens works as a resistance inducer against groundnut bud necrosis virus in chilli (Capsicum annuum L.). Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 1585–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egea, C.; Pérez, M.D.G.; Candela, M.E. Capsidiol accumulation in Capsicum annuum stems during the hypersensitive reaction to Phytophthora capsici. J. Plant Physiol. 1996, 149, 762–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.K.; Kim, Y.J. Capsidiol production in pepper plants associated with age-related resistance to Phytophthora capsici. Plant Pathol. J. 1990, 6, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez-Díaz, I.F. Expresión de Respuesta de Defensa en Chile Jalapeño Inoculado con Agentes de Control Biológico de Phytophthora capsici Leo. Ph.D. Thesis, Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Gene | Accession Number † | Sequences (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| PR-1 | XM_016683907 | FW: CCCAAAATTACGCCAATCAAAG RV: ACATCTTCACGGCACCAG |

| PR-5 | NM_001324896 | FW: TGGTGGAGTCTTGCAGTGC RV: CGTGCAATGGATCGCGTG |

| EAS | AJ005588 | FW: GCTCAAGAAATTGAACCGCCGAAG RV: TCTTCATTATAGACATCGCCCTCG |

| GAPDH | AJ246011 | FW: GGCCTTATGACTACAGTTCACTCC RV: GATCAACCACAGAGACATCCACAG |

| Treatment | Severity (0–6) † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 7 | 11 | 14 | |

| Pc | 1.0 ± 0.68 a | 1.5 ± 0.76 bc | 3.66 ± 0.55 ab | 6.0 ± 0.0 a |

| BMBA+Pc | 1.0 ± 0.33 a | 1.0 ± 0.68 b | 2.5 ± 0.71 c | 5.0 ± 0.44 b |

| BMBI+Pc | 0.33 ± 0.33 a | 0.83 ± 0.40 b | 4.16 ± 0.70 bc | 5.66 ± 0.21 a |

| BMBC+Pc | 1.0 ± 0.44 a | 3.0 ± 0.63 ab | 5.66 ± 0.21 a | 6.0 ± 0.0 a |

| BMBH+Pc | 0.33±0.33 a | 4.0 ± 0.63 a | 5.33 ± 0.21 ab | 5.83 ± 0.16 a |

| BMBP+Pc | 2.0 ± 1.0 a | 2.5 ± 0.5 abc | 5.83 ± 0.16 a | 6.0 ± 0.0 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ávila-Oviedo, J.L.; Méndez-Inocencio, C.; Rodríguez-Torres, M.D.; Angoa-Pérez, M.V.; Martínez-Mendoza, E.K.; Villar-Luna, E. In Vivo Screening of Rhizobacteria Against Phytophthora capsici and Bacillus subtilis Induced Defense Gene Expression in Chili Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Horticulturae 2026, 12, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010059

Ávila-Oviedo JL, Méndez-Inocencio C, Rodríguez-Torres MD, Angoa-Pérez MV, Martínez-Mendoza EK, Villar-Luna E. In Vivo Screening of Rhizobacteria Against Phytophthora capsici and Bacillus subtilis Induced Defense Gene Expression in Chili Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleÁvila-Oviedo, José Luis, Carlos Méndez-Inocencio, María Dolores Rodríguez-Torres, María Valentina Angoa-Pérez, Erika Karina Martínez-Mendoza, and Edgar Villar-Luna. 2026. "In Vivo Screening of Rhizobacteria Against Phytophthora capsici and Bacillus subtilis Induced Defense Gene Expression in Chili Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.)" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010059

APA StyleÁvila-Oviedo, J. L., Méndez-Inocencio, C., Rodríguez-Torres, M. D., Angoa-Pérez, M. V., Martínez-Mendoza, E. K., & Villar-Luna, E. (2026). In Vivo Screening of Rhizobacteria Against Phytophthora capsici and Bacillus subtilis Induced Defense Gene Expression in Chili Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Horticulturae, 12(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010059