Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Juvenile Achachairu Trees (Garcinia humilis (Vahl) C.D. Adams) to Elevated Soil Salinity Induced by Saline Irrigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growing Conditions

2.2. Experimental Design and Salinity Treatments

2.3. Physiological Measurements

2.3.1. Gas Exchange

2.3.2. Chlorophyll Fluorescence

2.3.3. Leaf Chlorophyll Index

2.3.4. Leaf and Root Nutrient Analyses

2.3.5. Antioxidants, Reactive Oxygen Species, and Lipid Peroxidation

2.4. Morphological Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

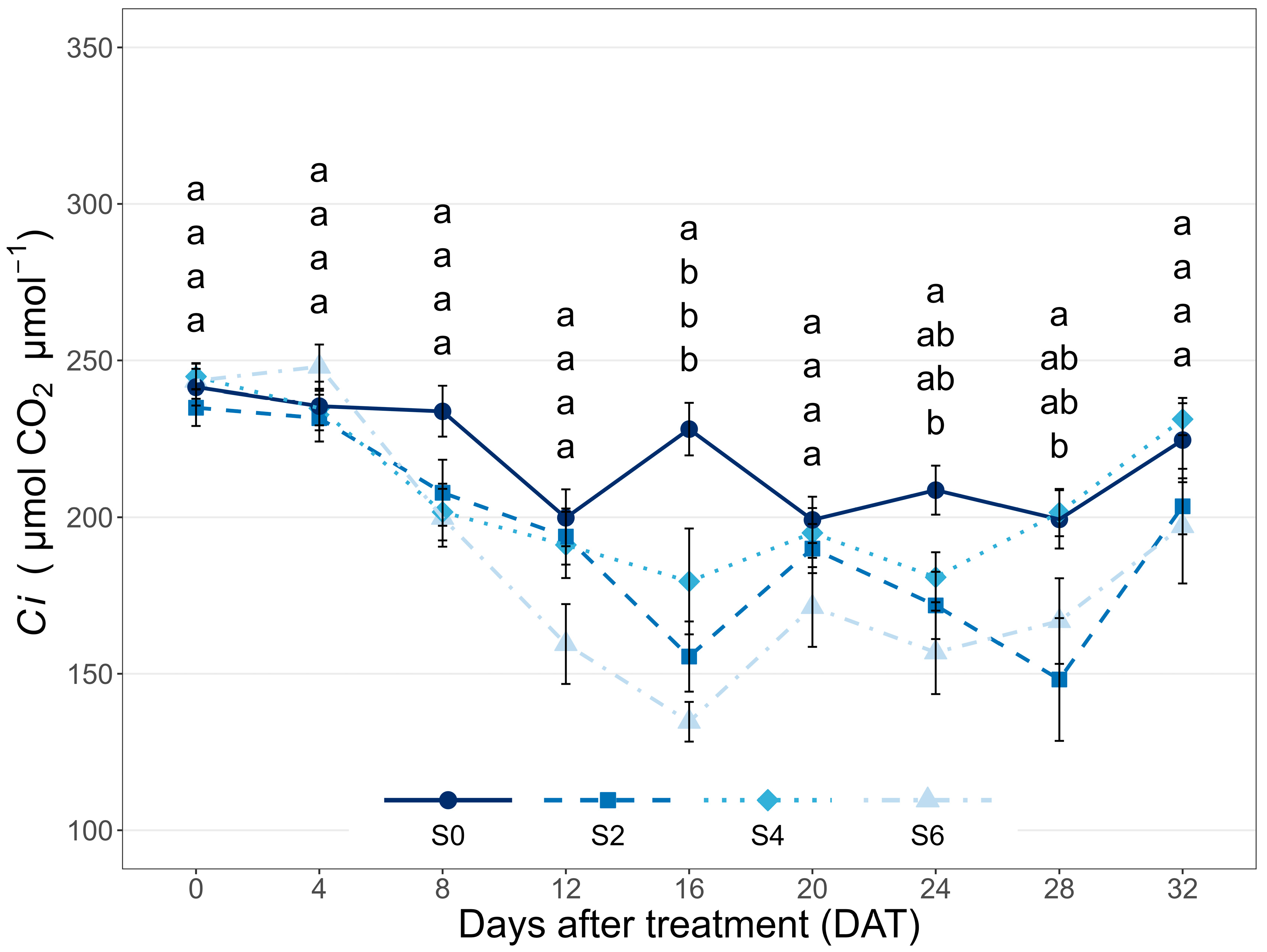

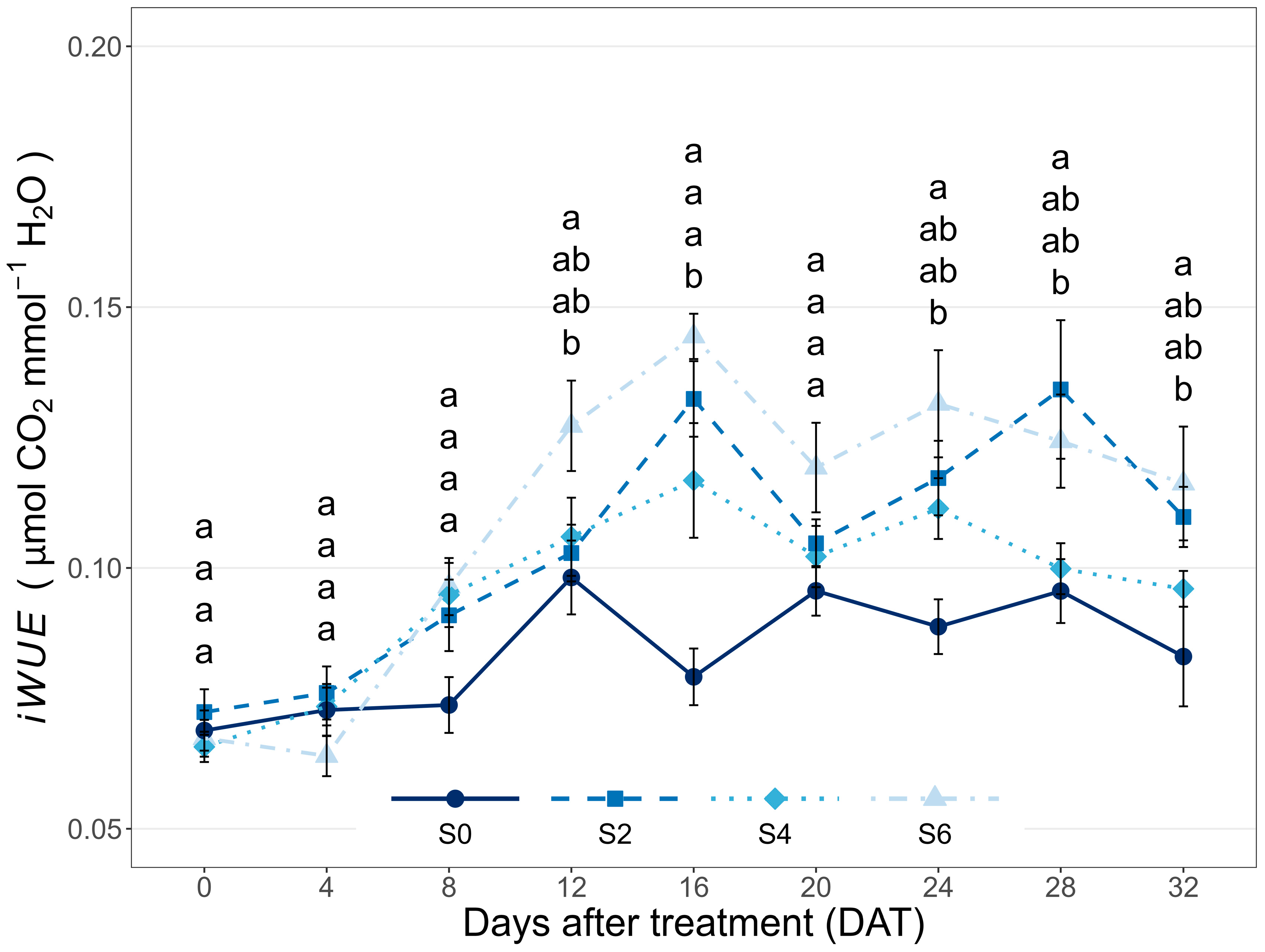

3.1. Leaf Gas Exchange

3.2. Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Chlorophyll Index

3.3. Leaf and Root Nutrient Analyses

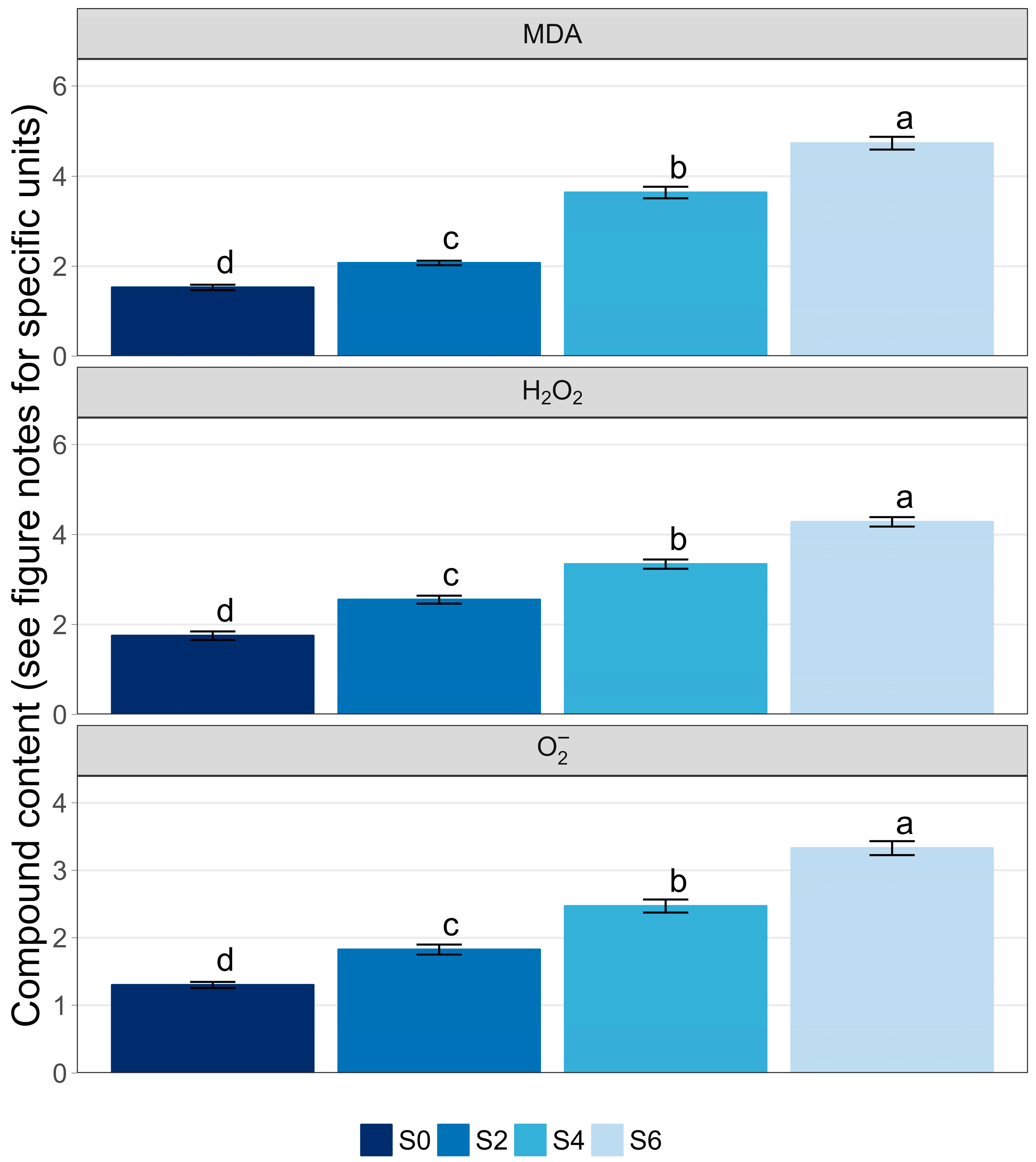

3.4. Antioxidants, Reactive Oxygen Species, and Lipid Peroxidation

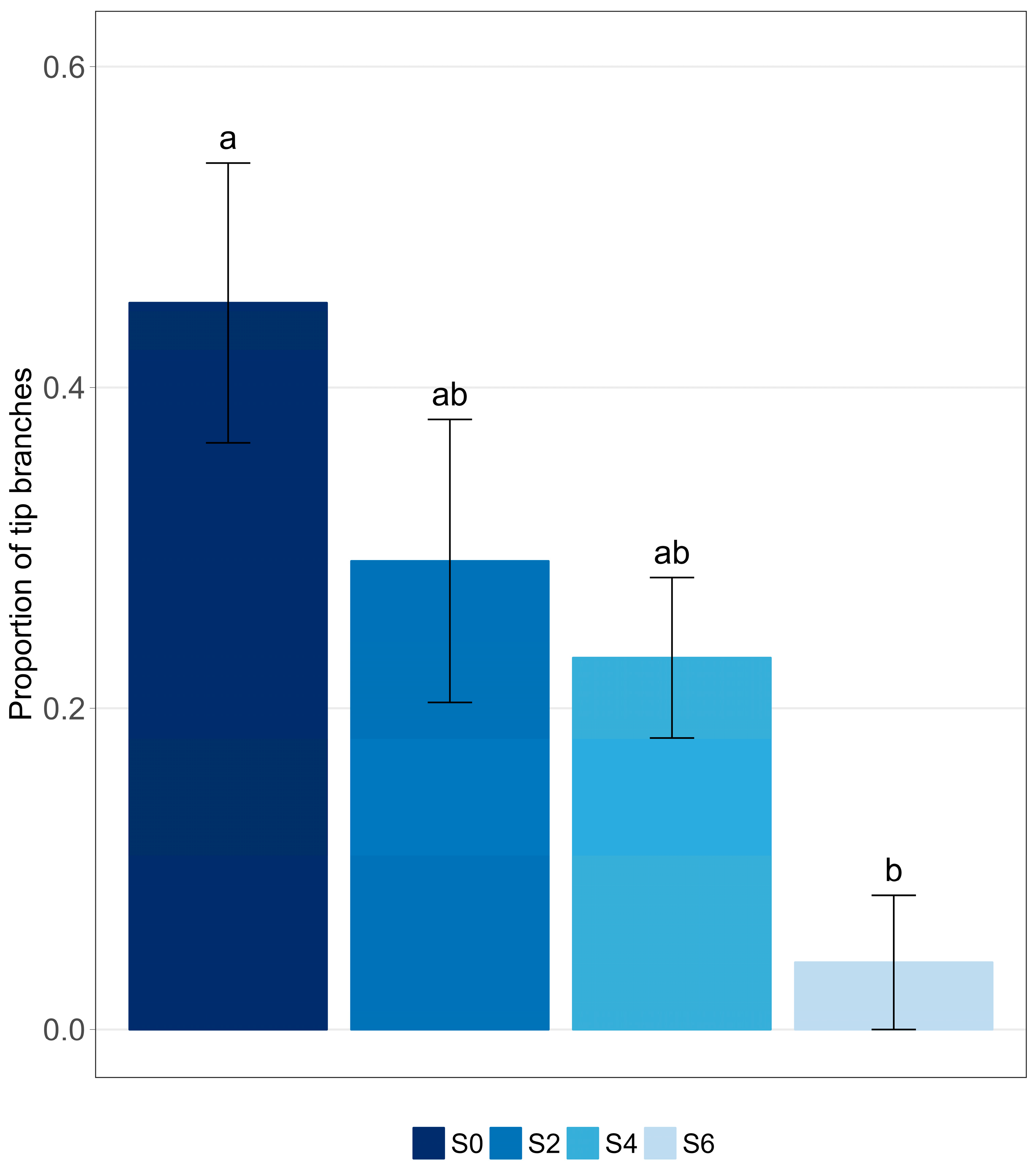

3.5. Morphological Changes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| An | net CO2 assimilation |

| APX | ascorbate peroxidase |

| ASA | ascorbic acid |

| Ca | calcium |

| CAT | catalase |

| Ci | internal CO2 concentration |

| Cl | chloride |

| Cu | copper |

| D | day |

| DHAR | dehydroascorbate reductase |

| EC | electrical conductivity |

| Fe | iron |

| Fv/Fm | ratio of variable to maximum chlorophyll fluorescence |

| FW | fresh weight |

| GPX | guaiacol peroxidase |

| gs | stomatal conductance of water vapor |

| GSH | glutathione |

| GTR | glutathione reductase |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| iWUE | intrinsic water-use efficiency (An/gs) |

| K | Potassium |

| LCI | leaf chlorophyll index |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MDAR | monodehydroascorbate reductase |

| Mg | magnesium |

| Mn | manganese |

| N | nitrogen |

| Na | sodium |

| NCC | nitrogen-containing compounds |

| O2− | superoxide radical |

| P | phosphorous |

| PAR | photosynthetically active radiation |

| PSII | photosystem II |

| POD | peroxidase |

| PPFD | photosynthetic photon flux density |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| S | sulfur |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| Zn | zinc |

References

- Bayabil, H.K.; Li, Y.; Crane, J.; Schaffer, B.; Smyth, A.; Zhang, S.; Evans, E.A.; Blare, T. Saltwater Intrusion and Flooding: Risks to South Florida’s Agriculture and Potential Management Practices: AE572/AE572, 5/2022. EDIS 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, A.K.; Das, A.B. Salt Tolerance and Salinity Effects on Plants: A Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2005, 60, 324–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parihar, P.; Singh, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Effect of Salinity Stress on Plants and Its Tolerance Strategies: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 4056–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, P.M.; Reichard, E.G. Saltwater Intrusion in Coastal Regions of North America. Hydrogeol. J. 2010, 18, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shi, Z.; Biswas, A.; Yang, S.; Ding, J. Multi-Algorithm Comparison for Predicting Soil Salinity. Geoderma 2020, 365, 114211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil Salinity: A Serious Environmental Issue and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria as One of the Tools for Its Alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, J.D.; Kandiah, A.; Mashali, A.M.; Rhoades, J.D. The Use of Saline Waters for Crop Production; FAO irrigation and drainage paper; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1992; ISBN 978-92-5-103237-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, A.; Azapagic, A.; Shokri, N. Global Predictions of Primary Soil Salinization under Changing Climate in the 21st Century. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Khare, T.; Zhang, X.; Rahman, M.M.; Hussain, M.; Gill, S.S.; Chen, Z.-H.; Zhou, M.; Hu, Z.; Varshney, R.K. Novel Strategies for Designing Climate-Smart Crops to Ensure Sustainable Agriculture and Future Food Security. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2025, 4, e70048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Plant Salt Tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2001, 6, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, T.E. Ionomic Responses of Papaya and Sapodilla Plants to Two Forms of Root-Zone Salinity. In Proceedings of the 2018 ASHS Annual Conference. ASHS. 2018. Available online: https://journals.ashs.org/view/journals/hortsci/53/9S/article-pS1.xml (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Shabala, S.; Cuin, T.A. Potassium Transport and Plant Salt Tolerance. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 133, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. Plant Water Relations, Plant Stress and Plant Production. In Plant Breeding for Water-Limited Environments; Blum, A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 11–52. ISBN 978-1-4419-7491-4. [Google Scholar]

- Marler, T.E.; Zozor, Y. Salinity Influences Photosynthetic Characteristics, Water Relations, and Foliar Mineral Composition of Annona squamosa L. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1996, 121, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of Salinity Tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, W.; Akhiyarova, G.; Veselov, D.; Kudoyarova, G. Rapid and Tissue-specific Changes in ABA and in Growth Rate in Response to Salinity in Barley Leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deinlein, U.; Stephan, A.B.; Horie, T.; Luo, W.; Xu, G.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant Salt-Tolerance Mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zelm, E.; Zhang, Y.; Testerink, C. Salt Tolerance Mechanisms of Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 403–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgadir, E.M.; Oka, M.; Fujiyama, H. Characteristics of Nitrate Uptake by Plants under Salinity. J. Plant Nutr. 2005, 28, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, M.A.; Franco-Navarro, J.D.; Peinado-Torrubia, P.; Díaz-Rueda, P.; Álvarez, R.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M. Chloride Improves Nitrate Utilization and NUE in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, A.; Raimondi, G.; Martino, A.; De Pascale, S. Salt Stress Response in Tomato beyond the Salinity Tolerance Threshold. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 59, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.M.F. Nitrogen Containing Compounds and Adaptation of Plants to Salinity Stress. Biol. Plant. 2000, 43, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive Oxygen Species Signalling in Plant Stress Responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, F.K.; Rivero, R.M.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Reactive Oxygen Species, Abiotic Stress and Stress Combination. Plant J. 2017, 90, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnocka, W.; Karpiński, S. Friend or Foe? Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Scavenging and Signaling in Plant Response to Environmental Stresses. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 122, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Abiotic Stress: Revisiting the Crucial Role of a Universal Defense Regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xiao, M.; Huang, R.; Wang, J. The Regulation of ROS and Phytohormones in Balancing Crop Yield and Salt Tolerance. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Machinery in Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Stress-Triggered Redox Signalling: What’s in pROSpect? Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Ma, X.; Wan, P.; Liu, L. Plant Salt-Tolerance Mechanism: A Review. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Yamani, M.; Cordovilla, M.d.P. Tolerance Mechanisms of Olive Tree (Olea europaea) under Saline Conditions. Plants 2024, 13, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Nath, J.; Singh, A.K.; Pareek, A.; Joshi, R. Ion Transporters and Their Regulatory Signal Transduction Mechanisms for Salinity Tolerance in Plants. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subba, A.; Tomar, S.; Pareek, A.; Singla-Pareek, S.L. The Chloride Channels: Silently Serving the Plants. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 171, 688–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teakle, N.L.; Tyerman, S.D. Mechanisms of Cl− Transport Contributing to Salt Tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 566–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Z. The Importance of Cl− Exclusion and Vacuolar Cl− Sequestration: Revisiting the Role of Cl− Transport in Plant Salt Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveh, E. Methods to Assess Potential Chloride Stress in Citrus: Analysis of Leaves, Fruit, Stem-Xylem Sap, and Roots. HortTechnology 2005, 15, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Harris, P.J.C. Potential Biochemical Indicators of Salinity Tolerance in Plants. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, I.S.; Gilliham, M.; Jha, D.; Mayo, G.M.; Roy, S.J.; Coates, J.C.; Haseloff, J.; Tester, M. Shoot Na+ Exclusion and Increased Salinity Tolerance Engineered by Cell Type–Specific Alteration of Na+ Transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2163–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.A.; Sarkhosh, A.; Khan, N.; Balal, R.M.; Ali, S.; Rossi, L.; Gómez, C.; Mattson, N.; Nasim, W.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Insights into the Physiological and Biochemical Impacts of Salt Stress on Plant Growth and Development. Agronomy 2020, 10, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourado, P.R.M.; de Souza, E.R.; dos Santos, M.A.; Lins, C.M.T.; Monteiro, D.R.; Paulino, M.K.S.S.; Schaffer, B. Stomatal Regulation and Osmotic Adjustment in Sorghum in Response to Salinity. Agriculture 2022, 12, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wungrampha, S.; Joshi, R.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A. Photosynthesis and Salinity: Are These Mutually Exclusive? Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvertsen, J.P.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Multiple Abiotic Stresses Occurring with Salinity Stress in Citrus. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 103, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, Z. Plant Responses and Adaptations to Salt Stress: A Review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Motos, J.R.; Ortuño, M.F.; Bernal-Vicente, A.; Diaz-Vivancos, P.; Sanchez-Blanco, M.J.; Hernandez, J.A. Plant Responses to Salt Stress: Adaptive Mechanisms. Agronomy 2017, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomelli, C.; Celis, V.; Lombardi, G.; Mártiz, J. Salt Stress Effects on Avocado (Persea Americana Mill.) Plants with and without Seaweed Extract (Ascophyllum nodosum) Application. Agronomy 2018, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, F.W.; Crane, J.H.; Bayabil, H.; Sarkhosh, A.; Shahid, M.A.; Schaffer, B. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of the Achachairu Tree (Garcinia humilis) to Prolonged Flooding. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, F.W.; Crane, J.H.; Bayabil, H.K.; Sarkhosh, A.; Shahid, M.A.; Schaffer, B. Achachairu (Garcinia humilis) Fruit Trees: Botany and Commercial Cultivation in South Florida. EDIS 2024, 2024. Available online: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/HS1480 (accessed on 20 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Bingman, C. Elemental Composition of Commercial Seasalts. J. Aquaric. Aquat. Sci. 1997, 8, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, T.; Schaffer, B.; Shahid, M.A.; Chaparro, J.X.; Sarkhosh, A. Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism in Peach Trees on Different Prunus Rootstocks in Response to Flooding. Plant Soil 2022, 475, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrão, S.; Schmöckel, S.M.; Tester, M. Evaluating Physiological Responses of Plants to Salinity Stress. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.-J.; Yang, H.-Y.; Bai, J.-P.; Liang, X.-Y.; Lou, Y.; Zhang, J.-L.; Wang, D.; ZHANG, J.-L.; Niu, S.-Q.; Chen, Y. Ultrastructural and Physiological Responses of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Plantlets to Gradient Saline Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, B.; Huang, B. Mechanism of Salinity Tolerance in Plants: Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Characterization. Int. J. Genom. 2014, 2014, e701596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, J.R.; Critchley, C. Effects of Salt Stress on the Growth, Ion Content, Stomatal Behaviour and Photosynthetic Capacity of a Salt-Sensitive Species, Phaseolus vulgaris L. Planta 1985, 164, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziska, L.H.; Seemann, J.R.; DeJong, T.M. Salinity iInduced Limitations on Photosynthesis in Prunus salicina, a Deciduous Tree Species. Plant Physiol. 1990, 93, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Z.; Rasheed, F.; Delagrange, S.; Abdullah, M.; Ruffner, C. Acclimatization of Terminalia arjuna Saplings to Salt Stress: Characterization of Growth, Biomass and Photosynthetic Parameters. J. Sustain. For. 2020, 39, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, S.; Deng, L.; Fritz, E.; Hüttermann, A.; Polle, A. Leaf Photosynthesis, Fluorescence Response to Salinity and the Relevance to Chloroplast Salt Compartmentation and Anti-Oxidative Stress in Two Poplars. Trees 2007, 21, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Chong, P.; Zhao, M. Effect of Salt Stress on the Photosynthetic Characteristics and Endogenous Hormones, and: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Salt Tolerance in Reaumuria soongorica Seedlings. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, 2031782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwa, N.; Pandey, V.; Gupta, O.P.; Yadav, A.; Meena, M.R.; Ram, S.; Singh, G. Unravelling Wheat Genotypic Responses: Insights into Salinity Stress Tolerance in Relation to Oxidative Stress, Antioxidant Mechanisms, Osmolyte Accumulation and Grain Quality Parameters. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurkman, W.J.; Fornari, C.S.; Tanaka, C.K. A Comparison of the Effect of Salt on Polypeptides and Translatable mRNAs in Roots of a Salt-Tolerant and a Salt-Sensitive Cultivar of Barley. Plant Physiol. 1989, 90, 1444–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rare, E. Stress Physiology: The Functional Significance of the Accumulation of Nitrogen-Containing Compounds. J. Hortic. Sci. 1990, 65, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Sohail, Y.; Shakeel, N.; Javed, M.; Bano, H.; Gul, H.S.; Zafar, Z.U.; Frahat Zaky Hassan, I.; Ghaffar, A.; Athar, H.-R.; et al. Role of Mineral Nutrients, Antioxidants, Osmotic Adjustment and PSII Stability in Salt Tolerance of Contrasting Wheat Genotypes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sedas, A.; Turner, B.L.; Winter, K.; Lopez, O.R. Salinity Responses of Inland and Coastal Neotropical Trees Species. Plant Ecol. 2020, 221, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.; Diaz-Espejo, A.; Romero-Jimenez, D.; Peinado-Torrubia, P.; Delgado-Vaquero, A.; Álvarez, R.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Rosales, M.A. Chloride Reduces Plant Nitrate Requirement and Alleviates Low Nitrogen Stress Symptoms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 212, 108717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergine, M.; Palm, E.R.; Salzano, A.M.; Negro, C.; Nissim, W.G.; Sabbatini, L.; Balestrini, R.; de Pinto, M.C.; Dipierro, N.; Gohari, G.; et al. Water and Nutrient Availability Modulate the Salinity Stress Response in Olea europaea Cv. Arbequina. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapazoglou, A.; Tani, E.; Papasotiropoulos, V.; Letsiou, S.; Gerakari, M.; Abraham, E.; Bebeli, P.J. Enhancing Abiotic Stress Resilience in Mediterranean Woody Perennial Fruit Crops: Genetic, Epigenetic, and Microbial Molecular Perspectives in the Face of Climate Change. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaha, D.V.M.; Ueda, A.; Saneoka, H.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Yaish, M.W. The Role of Na+ and K+ Transporters in Salt Stress Adaptation in Glycophytes. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Maggiora, L.; Francini, A.; Giovannelli, A.; Sebastiani, L. Assessment of the Salinity Tolerance, Response Mechanisms and Nutritional Imbalance to Heterogeneous Salt Supply in Populus Alba L. Clone ‘Marte’ Using a Split-Root System. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 101, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, U.K.; Islam, M.N.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Khan, M.A.R. Understanding the Roles of Osmolytes for Acclimatizing Plants to Changing Environment: A Review of Potential Mechanism. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1913306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, M.; Akhtar, J.; Qureshi, R.H. Na+ Exclusion and Salt Resistance of Wheat (Triticum aestivum) in Saline-Waterlogged Conditions Are Improved by the Development of Adventitious Nodal Roots and Cortical Root Aerenchyma. Plant Sci. 2005, 169, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengel, Z. The Role of Calcium in Salt Toxicity. Plant Cell Environ. 1992, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañero, F.J.; Martínez-Ballesta, M.C.; Teruel, J.A.; Carvajal, M. New Evidence About the Relationship Between Water Channel Activity and Calcium in Salinity-Stressed Pepper Plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006, 47, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazare, S.; Cohen, Y.; Goldshtein, E.; Yermiyahu, U.; Ben-Gal, A.; Dag, A. Rootstock-Dependent Response of Hass Avocado to Salt Stress. Plants 2021, 10, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casierra-Posada, F.E.; Rodríguez, S.Y. Tolerancia de Plantas de Feijoa (Acca sellowiana [Berg] Burret) a La Salinidad Por NaCl. Agron. Colomb. 2006, 24, 258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Munns, R.; James, R.A.; Xu, B.; Athman, A.; Conn, S.J.; Jordans, C.; Byrt, C.S.; Hare, R.A.; Tyerman, S.D.; Tester, M.; et al. Wheat Grain Yield on Saline Soils Is Improved by an Ancestral Na+ Transporter Gene. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, B.; Wang, T.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, S. Mechanisms of Plant Salt Response: Insights from Proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhir, P.; Murthy, S.D.S. Effects of Salt Stress on Basic Processes of Photosynthesis. Photosynthetica 2004, 42, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, F.W.; Crane, J.H.; Bayabil, H.K.; Sarkhosh, A.; Shahid, M.A.; Schaffer, B. Brassinosteroid Priming Mitigates Negative Physiological Responses of Garcina Humilis to Flooding and Salinity. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.; Johnson, G.N. Chlorophyll Fluorescence—A Practical Guide. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Medrano, H. Drought-inhibition of Photosynthesis in C3 Plants: Stomatal and Non-stomatal Limitations Revisited. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabala, S.; Wu, H.; Bose, J. Salt Stress Sensing and Early Signalling Events in Plant Roots: Current Knowledge and Hypothesis. Plant Sci. 2015, 241, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, F.W.; Crane, J.H.; Bayabil, H.K.; Sarkhosh, A.; Shahid, M.A.; Schaffer, B. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of the Achachairu Tree (Garcinia humilis) to the Combined Effects of Salinity and Flooding. Plant Soil 2025, 512, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sanchez, F.W.; Crane, J.H.; Bayabil, H.K.; Sarkhosh, A.; Shahid, M.A.; Schaffer, B. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Juvenile Achachairu Trees (Garcinia humilis (Vahl) C.D. Adams) to Elevated Soil Salinity Induced by Saline Irrigation. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010020

Sanchez FW, Crane JH, Bayabil HK, Sarkhosh A, Shahid MA, Schaffer B. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Juvenile Achachairu Trees (Garcinia humilis (Vahl) C.D. Adams) to Elevated Soil Salinity Induced by Saline Irrigation. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanchez, Federico W., Jonathan H. Crane, Haimanote K. Bayabil, Ali Sarkhosh, Muhammad A. Shahid, and Bruce Schaffer. 2026. "Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Juvenile Achachairu Trees (Garcinia humilis (Vahl) C.D. Adams) to Elevated Soil Salinity Induced by Saline Irrigation" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010020

APA StyleSanchez, F. W., Crane, J. H., Bayabil, H. K., Sarkhosh, A., Shahid, M. A., & Schaffer, B. (2026). Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Juvenile Achachairu Trees (Garcinia humilis (Vahl) C.D. Adams) to Elevated Soil Salinity Induced by Saline Irrigation. Horticulturae, 12(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010020