Rootstocks and Root Systems in Citrus clementina (Hort ex Tan.) Plants: Ecophysiological, Morphological, and Histo-Anatomical Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup and Growth Environments

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Agronomic Management

2.5. Biometric Measurements and Morphological Analyses

2.6. Stomatal Conductance and Leaf Water Potential Measurements

2.7. Determination of Hydraulic Conductance Using High-Conductance Flow Meter (HCFM)

2.8. Anatomical and Histological Analyses of Xylem Conductive Structures

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Vegetative Growth

3.2. Biomass Accumulation and Dry Weight Distribution

3.3. Dry Matter Allocation in Rootstocks

3.4. Vascular Anatomy and Theoretical Flow

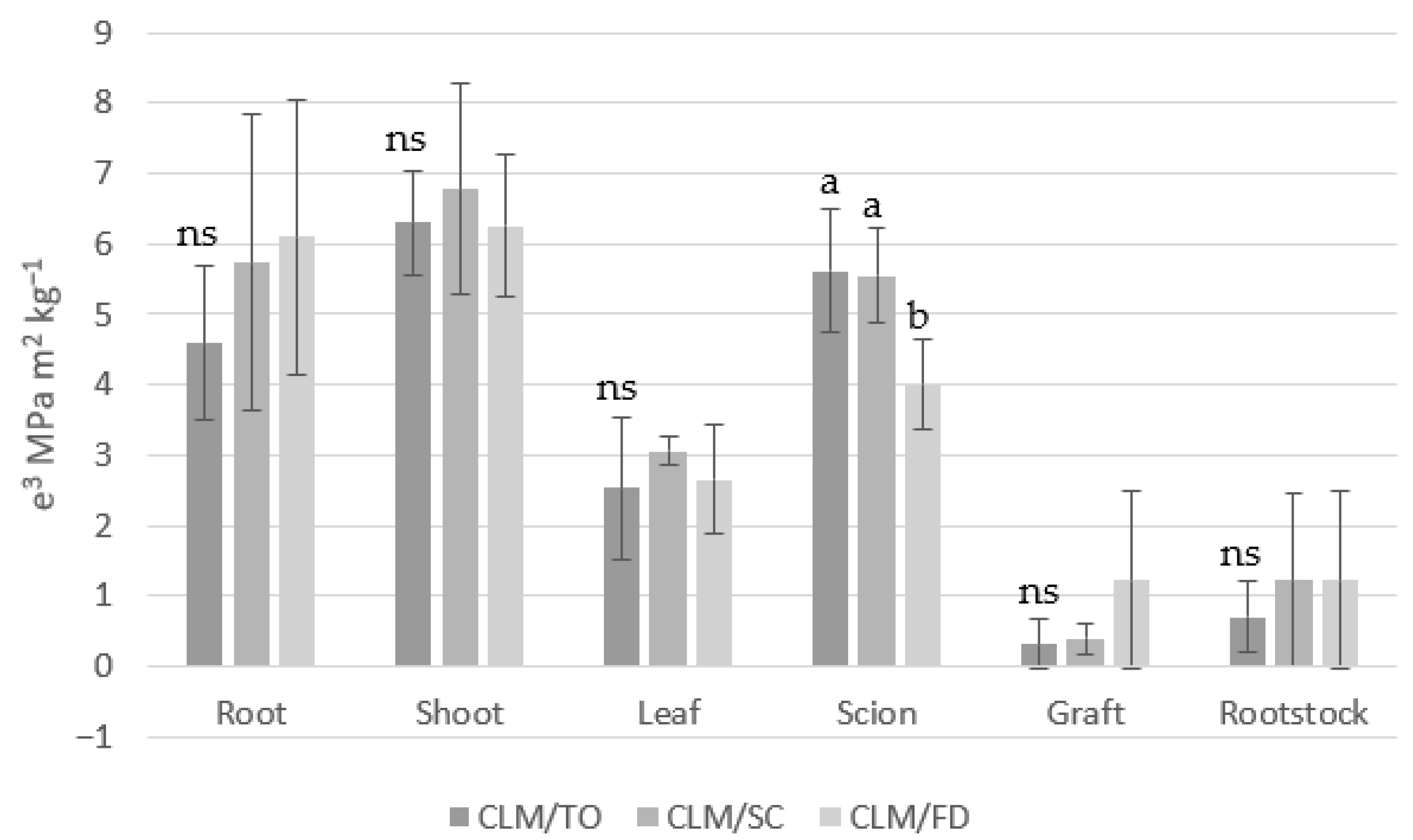

3.5. Hydraulic Resistance

3.6. Xylem Vessel Diameter Classes

3.7. Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Functional Balance and Biomass Allocation in Graft Combinations

4.2. Hydraulic Architecture and Anatomical Determinants of Vigor

4.3. Integrated Responses and Implications for Rootstock Selection

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, P.; Liu, F.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Jin, L. Physiological and Molecular Insights into Citrus Rootstock–Scion Interactions: Compatibility, Signaling, and Impact on Growth, Fruit Quality and Stress Responses. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, G.; Arcidiacono, F.; Puglisi, I.; Baglieri, A.; La Malfa, S.; Gentile, A.; Arbona, V.; Continella, A. Response to Water Stress of Eight Novel and Widely Spread Citrus Rootstocks. Plants 2025, 14, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Vieira, D.D.S.; Freschi, L.; Almeida, L.A.d.H.; Moraes, D.H.S.; Neves, D.M.; dos Santos, L.M.; Bertolde, F.Z.; Soares Filho, W.d.S.; Coelho Filho, M.A.; Gesteira, A.d.S. Survival strategies of citrus rootstocks subjected to drought. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, P. Citrus Tristeza Virus: A Pathogen That Changed the Course of the Citrus Industry. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 9, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.F.; Keremane, M.L. Mild Strain Cross Protection of Tristeza: A Review of Research to Protect Against Decline on Sour Orange Rootstock. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Alfaro, J. Effect of Rootstock on Citrus Fruit Quality: A Review. J. Hortic. Sci. 2023, 39, 2835–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvertsen, J.P. Hydraulic Conductivity of Four Commercial Citrus Rootstocks. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1981, 106, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Peris, V.; López-Climent, M.F.; Moliner-Sabater, M.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Pérez-Clemente, R.M. Morphological, Physiological, and Molecular Scion Traits Are Determinant for Salt-Stress Tolerance of Grafted Citrus Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1145625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Ashraf, E.; Albaayit, S.F.A.; Shafqat, W.; Shareef, N.; Ud Din, S.; Sadaf, S.; Rashid, S.; Tasneem, S. Rootstock Influence on Performance of Different Citrus Scion Cultivars: A Review. J. Glob. Innov. Agric. Sci. 2023, 11, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloni, B.; Cohen, R.; Karni, L.; Aktas, H.; Edelstein, M. Hormonal signaling in rootstock–scion interactions. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 127, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnon, D.I. The Water-Culture Method for Growing Plants Without Soil; (Circular 347); University of California, College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem, M.E.; Albacete, A.; Smigocki, A.C.; Frebort, I.; Pospíšilová, H.; Martínez-Andújar, C.; Acosta, M.; Sanchez-Bravo, J.; Lutts, S.; Dodd, I.C.; et al. Root-synthesized cytokinins improve shoot growth and fruit yield in salinized tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.J.; Chapin, F.S., III; Mooney, H.A. Resource limitation in plants—An economic analogy. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1985, 16, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Nagel, O. The role of biomass allocation in the growth response of plants to different levels of light, CO2, nutrients and water: A quantitative review. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 2000, 27, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Sack, L. Pitfalls and possibilities in the analysis of biomass allocation patterns in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucconi, F. Root/Shoot Relationships in Grafted Plants: A Cyclical Correlation Model; Atti del Convegno Sospensione e Attività Vegetative; Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei: Roma, Italy, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hacke, U.G.; Sperry, J.S.; Wheeler, J.K.; Castro, L. Scaling of angiosperm xylem structure with safety and efficiency. Tree Physiol. 2006, 26, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, C.J.; Else, M.A.; Taylor, L.; Dover, C.J. Root and stem hydraulic conductivity as determinants of growth potential in grafted trees of apple (Malus pumila Mill.). J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.D. Vigour mechanisms in dwarfing rootstocks for temperate fruit trees. In International Symposium on Rootstocks for Deciduous Fruit Tree Species; Moreno Sánchez, M.A., Webster, A.D., Eds.; Acta Horticulturae 658; International Society for Horticultural Science: Leuven, Belgium, 2004; pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucconi, F. Control of development in woody plants: An introduction to the physiology of pruning. Riv. Frutticoltura 1992, 12, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tyree, M.T.; Zimmermann, M.H. Hydraulic architecture of whole plants and plant performance. In Xylem Structure and the Ascent of Sap; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 175–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombesi, S.; Johnson, R.S.; Day, K.R.; DeJong, T.M. Interactions between rootstock, inter stem and scion xylem vessel characteristics of peach trees growing on rootstocks with contrasting size-controlling characteristics. AoB Plants 2010, 2010, plq013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clearwater, M.J.; Lowe, R.G.; Hofstee, B.J.; Barclay, C.; Mandemaker, A.J.; Blattmann, P. Hydraulic conductance and rootstock effects in grafted vines of kiwifruit. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Niklas, K.J.; Peñuelas, J.; Hu, D.; Zhong, Q.; Cheng, D. Universal trade-off between vessel size and number and its implications for plant hydraulic function. Oecologia 2025, 207, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Ediger, D. Rootstocks with different vigor influenced scion–water relations and stress responses in Ambrosia™ apple trees (Malus domestica var. Ambrosia). Plants 2021, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Graft Combination | Height cm | Leaf Area m2 | Rootstock Base Diameter mm | Absorbent Root Length m | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| CLM/TO | 78.00 ± 6.25 a | 147.67 ± 10.89 a | 0.29 ± 0.06 a | 0.39 ± 0.06 a | 22.47 ± 1.09 ns | 26.74 ± 1.03 ns | 29.54 ± 3.05 a | 40.14 ± 4.06 a |

| CLM/SC | 79.67 ± 6.00 a | 147.14 ± 11.91 a | 0.29 ± 0.06 a | 0.38 ± 0.04 a | 21.75 ± 1.14 | 30.53 ± 1.22 | 29.44 ± 3.16 a | 40.21 ± 3.17 a |

| CLM/FD | 55.67 ± 5.13 b | 108.15 ± 4.50 b | 0.16 ± 0.04 b | 0.22 ± 0.01 b | 21.44 ± 1.08 | 26.83 ± 0.44 | 19.10 ± 2.78 b | 30.60 ± 1.14 b |

| Year | * | * | * | * | ||||

| Year | Graft Combination (T) | Rootstock | Scion | Total Dry Weight Plant g | S/R Scion/Rootstock | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine Root g | Structural Root g | Rootstock Stem g | Total dry Weight g | Leaves g | Stem, Shoots, and Branches g | Total Dry Weight Scion g | ||||

| 2023 | CLM/TO | 21.98 ± 2.2 a | 23.84 ± 3.2 a | 73.87 ± 6.8 b | 119.69 ± 9.55 b | 25.93 ± 2.0 a | 32.22 ± 3.2 a | 58.15 ± 5.01 a | 177.84 ± 14.24 b | 0.48 ± 0.08 a |

| CLM/SC | 18.07 ± 1.9 a | 24.72 ± 2.0 a | 92.96 ± 9.1a | 135.75 ± 3.83 a | 28.34 ± 2.8 a | 31.00 ± 2.5 a | 59.34 ± 2.38 a | 195.09 ± 15.92 a | 0.43 ± 0.02 a | |

| CLM/FD | 10.12 ± 1.1 b | 13.75 ± 2.1 b | 62.01 ± 4.2 c | 85.88 ± 5.23 c | 16.85 ± 1.8 b | 16.15 ± 2.1 b | 33.00 ± 4.73 b | 128.88 ± 11.39 c | 0.34 ± 0.04 b | |

| 2024 | CLM/TO | 18.37 ± 2.73 a | 20.19 ± 1.90 a | 79.3 ±4.48 a | 117.85 ± 11.88 b | 44.53 ± 3.06 a | 54.95 ± 4.65 a | 99.48 ± 5.73 a | 231.33 ± 16.03 a | 0.75 ± 0.09 a |

| CLM/SC | 19.58 ± 2.29 a | 21.29 ± 2.26 a | 84.11 ± 6.11 a | 124.98 ± 12.15 b | 50.56 ± 6.13 a | 54.49 ± 3.91 a | 105.0 ± 7.12 a | 251.03 ± 14.13 a | 0.72 ± 0.04 a | |

| CLM/FD | 16.11 ± 1.72 b | 14.49 ± 1.86 b | 69.04 ± 4.06 b | 99.63 ± 6.63 a | 25.93 ± 3.14 b | 24.63 ± 2.65 b | 58.56 ± 9.48 b | 152.19 ± 10.54 b | 0.49 ± 0.04 b | |

| Y | * | ns | ns | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Y × T | * | ns | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Graft Combination | Structural Roots | Absorbing Roots | Rootstock Stem | Structural Roots | Absorbing Roots | Rootstock Stem |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 2024 | |||||

| CLM/TO | 18.36 a | 19.91 a | 61.71 b | 15.58 b | 17.13 a | 67.28 b |

| CLM/SC | 13.31 b | 18.21 ab | 68.47 ab | 15.66 b | 17.03 a | 67.29 b |

| CLM/FD | 11.78 c | 16.01 c | 72.20 a | 16.16 a | 14.54 b | 69.28 a |

| Graft Combination | Leaf Area (cm2) | Total Leaf Area (m2) | Vascular Density—Rootstock (n°/mm2) | Vascular Density—Scion (n°/mm2) | Xylem Area—Rootstock (mm2) | Xylem Area—Scion (mm2) | Theoretical Flow—Rootstock ∑πr4 | Theoretical Flow—Scion ∑πr4 | ∑πr4/Aleaf (e−12 mm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLM/TO | 15.71 ± 2.2 a | 0.35 ± 0.08 a | 70 ± 10 ns | 57 ± 11 ns | 345.65 ± 28 b | 227 ± 32 a | 18.77 ± 1.2 a | 20.99 ± 1.9 a | 53.12 ± 6.2 ns |

| CLM/SC | 14.17 ± 2 a | 0.34 ± 0.05 a | 90.5 ± 4 | 71.5 ± 12 | 442 ± 26 a | 237 ± 30 a | 20.04 ± 2.1 a | 21.83 ± 2.1 a | 57.63 ± 5.5 |

| CLM/FD | 9.36 ± 2.1 b | 0.18 ± 0.03 b | 80.5 ± 6 | 73.5 ± 12 | 295 ± 26 b | 111 ± 25 b | 10.41 ± 1.7 b | 10.79 ± 1.4 b | 57.31 ± 4.4 |

| Graft Combination | gs mmol m−2 s−1 | Ψleaf Bar |

|---|---|---|

| CLM/TO | 25.14 ± 2.21 ns | −10.52 ± 0.31 a |

| CLM/SC | 24.00 ± 0.58 | −12.83 ± 0.33 b |

| CLM/FD | 32.33 ± 5.36 | −11.21 ± 0.32 a |

| T | ns | * |

| Y | ns | ns |

| T × Y | ns | ns |

| Variable | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|

| Height | 0.9816 | 0.0184 |

| Leaf area | 0.9691 | 0.0309 |

| Steam base diameter | 0.3444 | 0.6556 |

| Length absorbent roots | 0.9861 | 0.0139 |

| DW fine root | 0.9497 | 0.0503 |

| DW coarse root | 0.9993 | 0.0007 |

| DW rootstock trunk | 0.9631 | 0.0369 |

| Total dry weight rootstock | 0.9771 | 0.0229 |

| DW leaves | 0.9873 | 0.0127 |

| DW shoots and branches | 0.9812 | 0.0188 |

| DW epigeal system | 0.9998 | 0.0002 |

| DW plant | 0.9958 | 0.0042 |

| Scion/rootstock | 0.9480 | 0.0520 |

| Total leaf area | 0.9691 | 0.0309 |

| Vascular density—rootstock | 0.0121 | 0.9879 |

| Vascular density—scion | 0.2388 | 0.7612 |

| Xylem area—rootstock (mm2) | 0.7026 | 0.2974 |

| Xylem area—scion (mm2) | 0.9972 | 0.0028 |

| Theoretical flow—rootstock | 1.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Theoretical flow—scion | 0.9969 | 0.0031 |

| ∑πr4/ALeaf | 0.1085 | 0.8915 |

| RRoot | 0.3533 | 0.6467 |

| RShoot | 0.4333 | 0.5667 |

| RLeaf | 0.1740 | 0.8260 |

| RScion | 0.9755 | 0.0245 |

| RGraft | 0.9613 | 0.0387 |

| RRootstock | 0.1511 | 0.8489 |

| gs | 1.0000 | 0.0000 |

| ψleaf | 0.1193 | 0.8807 |

| Rootstock | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|

| TO | 0.3290 | 0.6710 |

| SC | 0.6121 | 0.3879 |

| FD | 0.9944 | 0.0056 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dattola, A.; Gullo, G. Rootstocks and Root Systems in Citrus clementina (Hort ex Tan.) Plants: Ecophysiological, Morphological, and Histo-Anatomical Factors. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010021

Dattola A, Gullo G. Rootstocks and Root Systems in Citrus clementina (Hort ex Tan.) Plants: Ecophysiological, Morphological, and Histo-Anatomical Factors. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleDattola, Antonio, and Gregorio Gullo. 2026. "Rootstocks and Root Systems in Citrus clementina (Hort ex Tan.) Plants: Ecophysiological, Morphological, and Histo-Anatomical Factors" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010021

APA StyleDattola, A., & Gullo, G. (2026). Rootstocks and Root Systems in Citrus clementina (Hort ex Tan.) Plants: Ecophysiological, Morphological, and Histo-Anatomical Factors. Horticulturae, 12(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010021