Integrating Proximal Sensing Data for Assessing Wood Distillate Effects in Strawberry Growth and Fruit Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

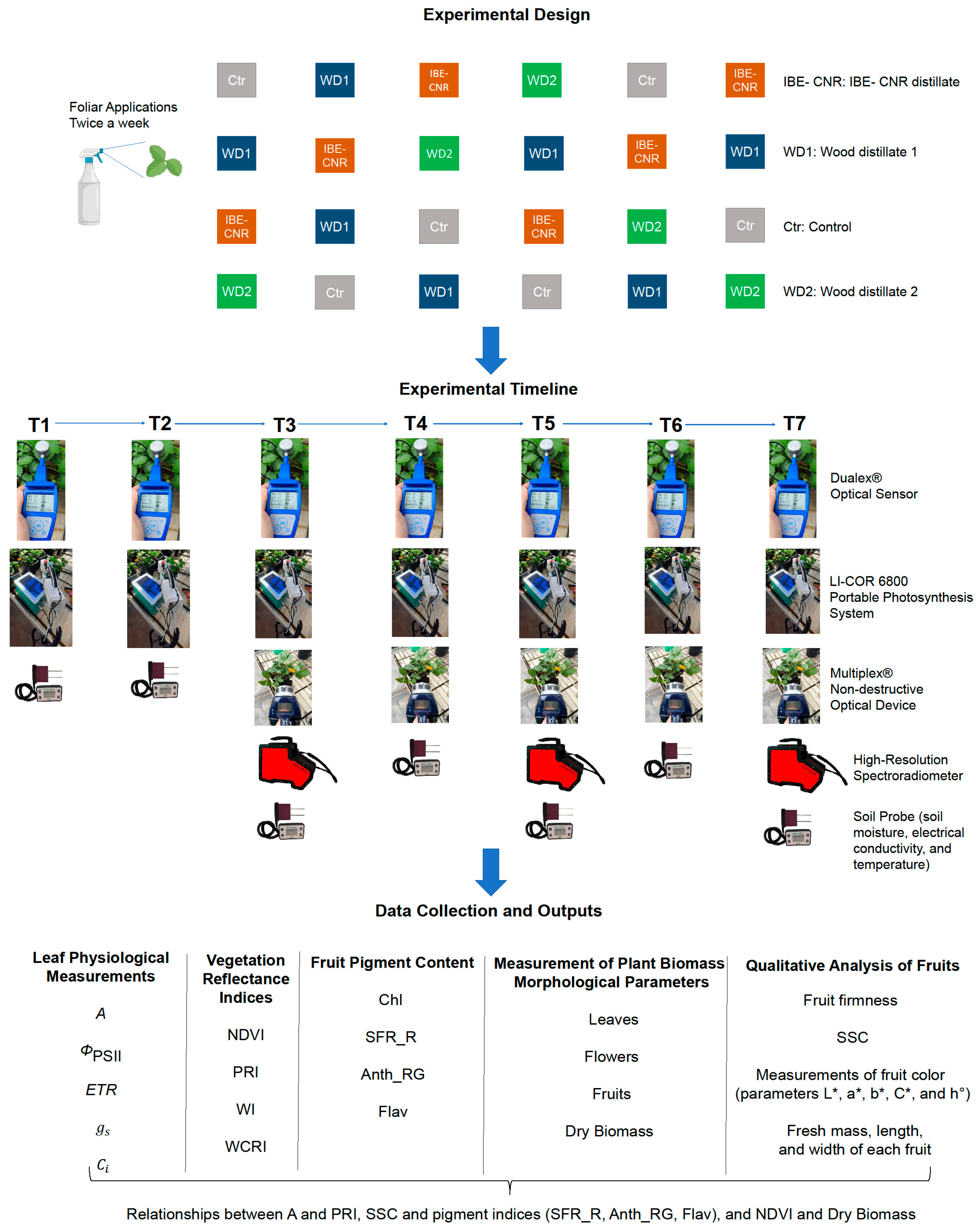

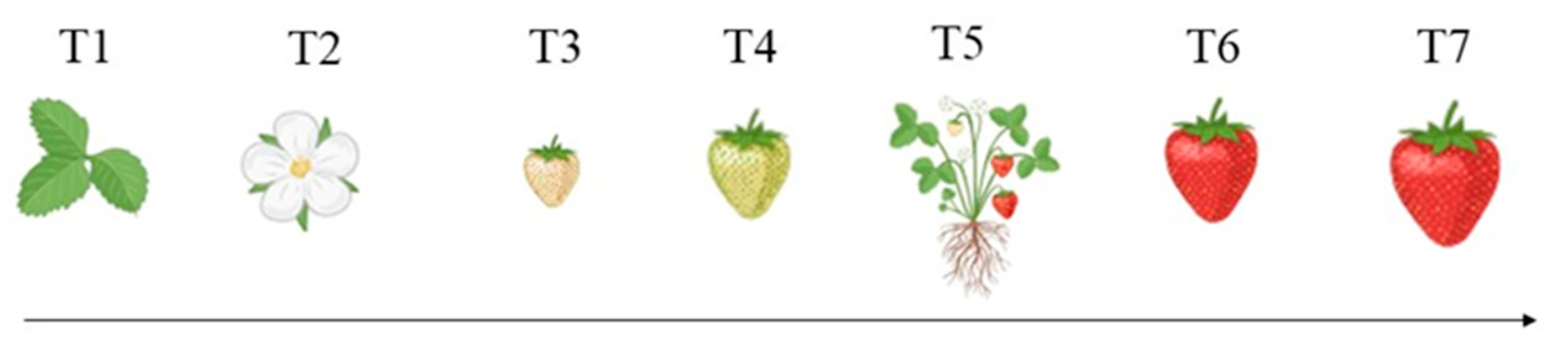

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phenols in Wood Distillates and Normalization of Experimental Dilutions

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Leaf Physiological Measurements

2.4. Leaf Chlorophyll Index and Vegetation Indices

2.5. Measurement of Plant Biomass and Morphological Parameters

2.6. Non-Destructive Assessment of Fruit Ripening

2.7. Qualitative Analysis of Fruits

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

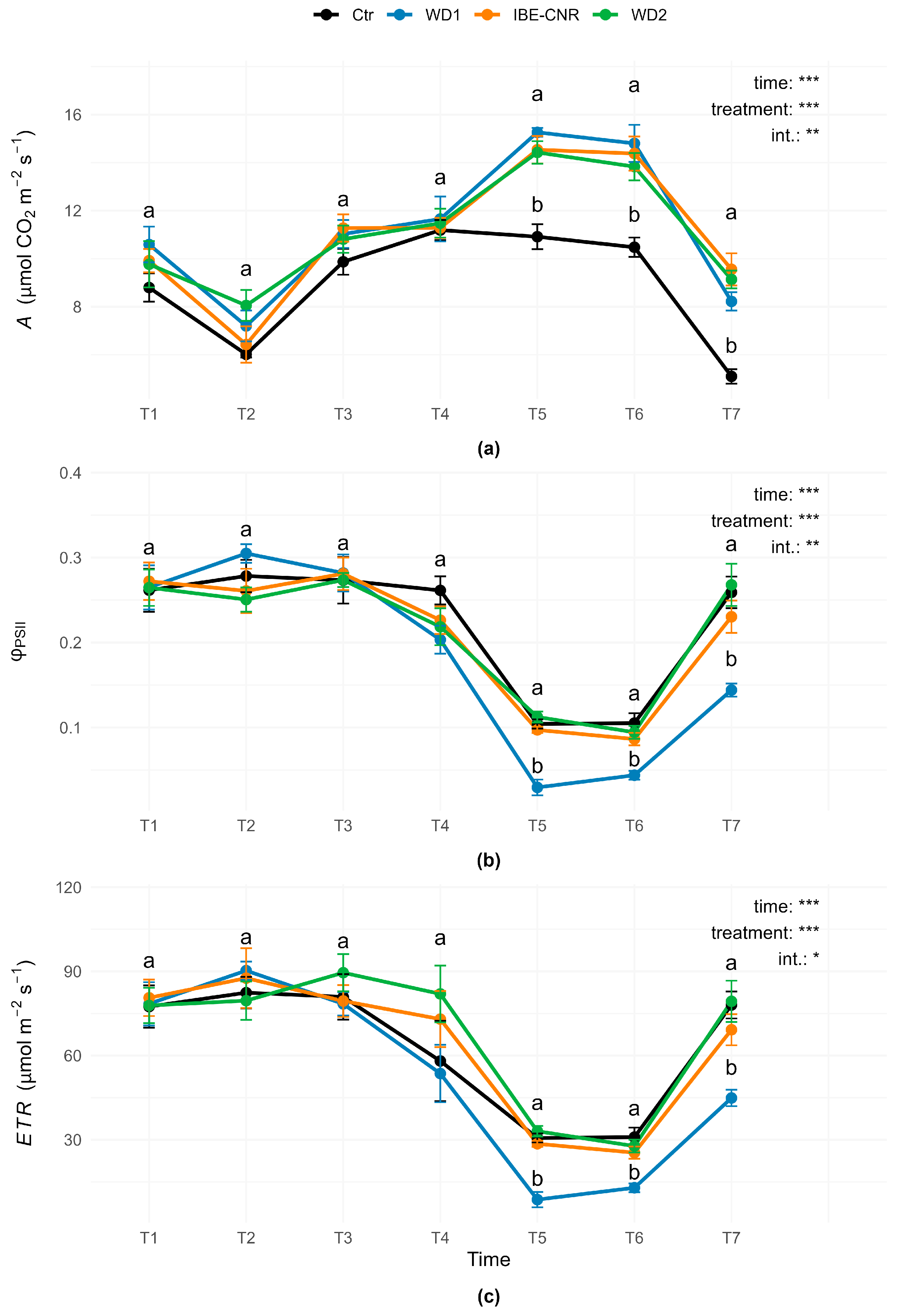

3.1. Leaf Physiological Measurements

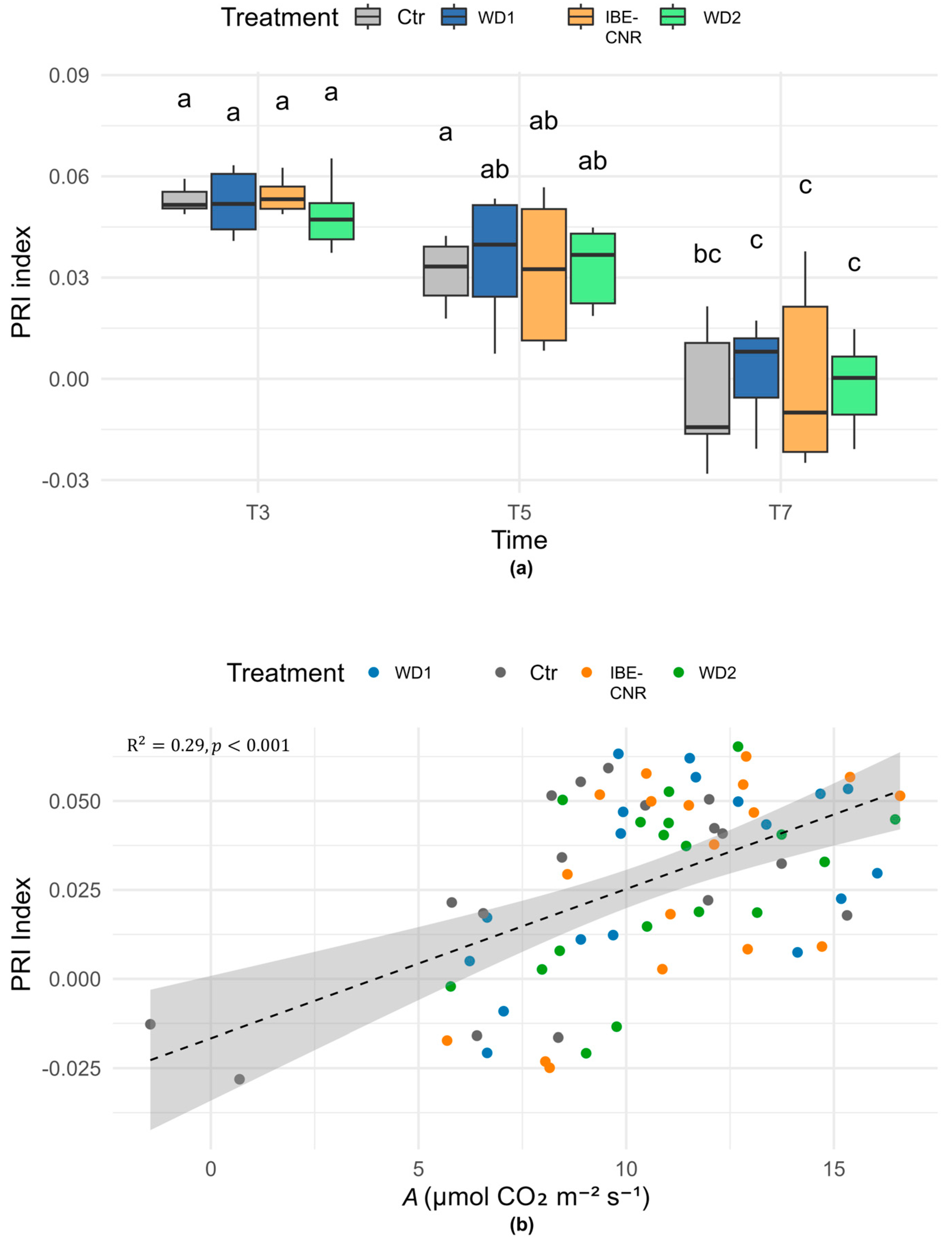

3.2. Vegetation Reflectance Indices and Leaf Chlorophyll Estimation

3.3. Plant Morphological Parameters and Biomass

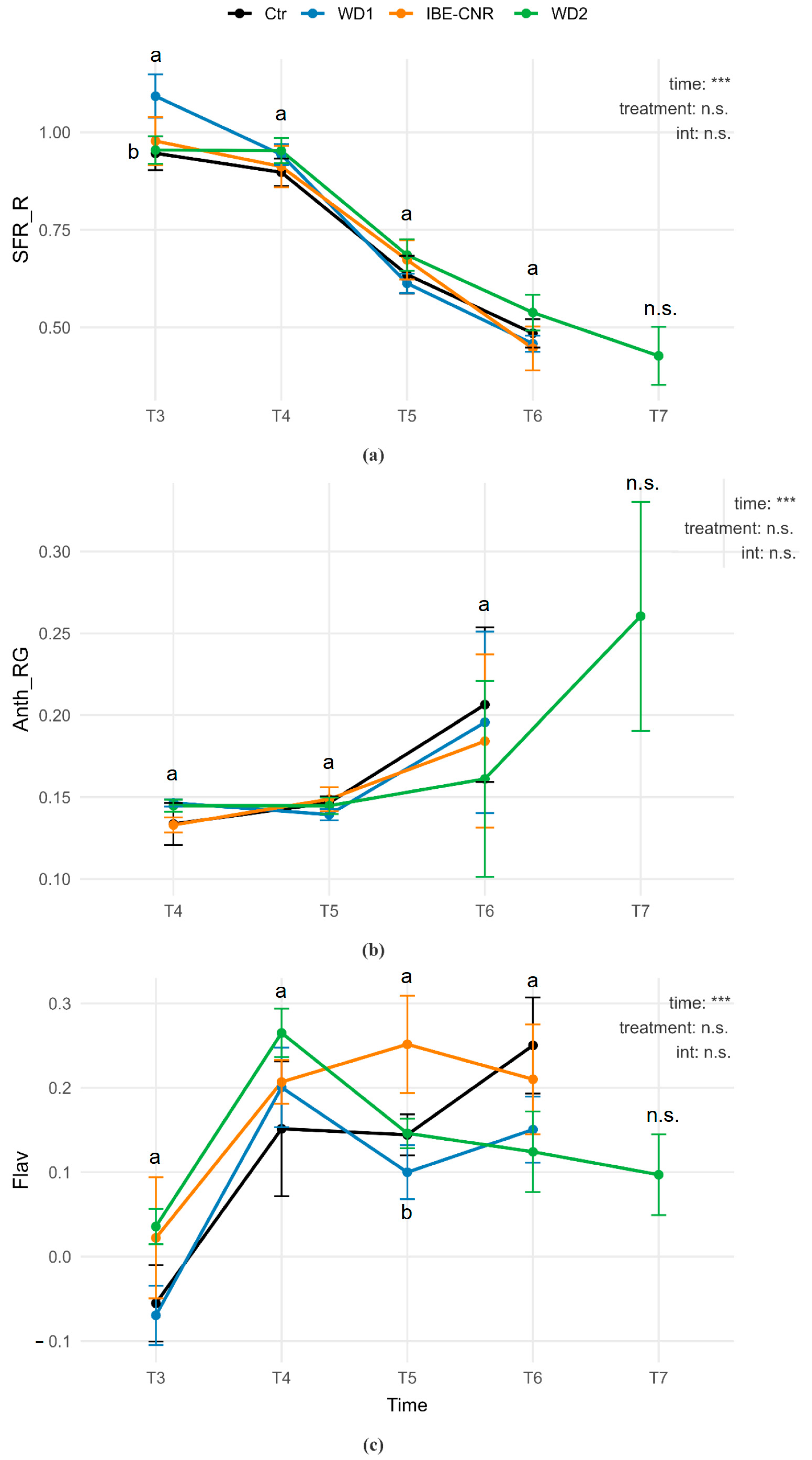

3.4. Strawberry Ripening Monitoring

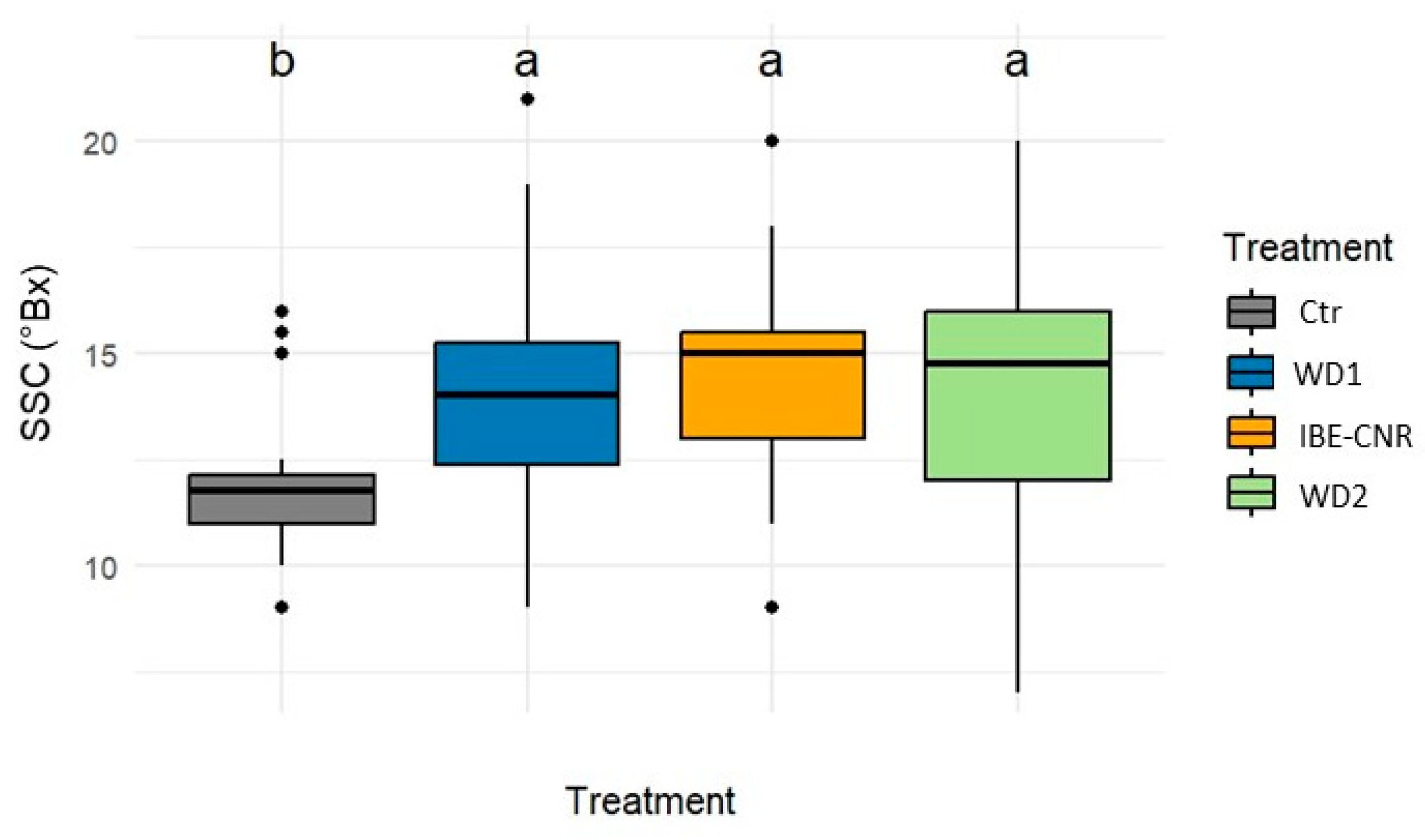

3.5. Yield and Fruit Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPLC-DAD | High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode array detector |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry |

| CRD | Completely randomized design |

| gs | Stomatal conductance |

| A | Net photosynthetic rate |

| Ci | Intercellular CO2 concentration |

| ΦPSII | Effective quantum yield of photosystem II |

| ETR | Electron transport rate |

| PPFD | Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density |

| ChI | Chlorophyll index |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| PRI | Photochemical Reflectance Index |

| WI | Water Index |

| WCRI | Water Content Reflectance Index |

| ChlF | Chlorophyll fluorescence |

| SFR_R | Ratio between the far-red ChlF and the red ChlF |

| Anth_RG | Anthocyanin index |

| Flav | Flavanol index |

| SSC | Soluble solids content |

| O.R. | Onset of ripening |

| A.R. | Advanced ripening stage |

| C.M. | Commercial maturity |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| GA3 | Gibberellic acid |

| CTK | Cytokinin’s |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

References

- Zhou, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Z.; Bao, L.; Xia, Y. Wood fiber biomass pyrolysis solution as a potential tool for plant disease management: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V. Renewable fuels and chemicals by thermal processing of biomass. Chem. Eng. J. 2003, 91, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, A.; Abbey, L.; Gunupuru, L.R. Production, prospects and potential application of pyroligneous acid in agriculture. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 135, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.B.; Sillero, L.; Gatto, D.A.; Labidi, J. Bioactive molecules in wood extractives: Methods of extraction and separation—A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 186, 115231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, G.P.; Meghana, A.; Shetty, M.G.; Balakrishna, S.M.; Niranjan, H.G. Wood vinegar: A promising agricultural input. A review. Int. J. Agric. Ext. Soc. Dev. 2025, 8, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Yu, J. Wood vinegar resulting from the pyrolysis of apple tree branches for annual bluegrass control. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 174, 114193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yao, J.; Zhang, C.; Hao, R.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, W. Quantitative analysis of multi-components by single-marker: An effective method for the chemical characterization of wood vinegar. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 182, 114862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-F.; Yang, C.-H.; Liang, M.-T.; Gao, Z.-J.; Wu, Y.-W.; Chuang, L.-Y. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of wood vinegar from Litchi chinensis. Molecules 2016, 21, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, S.P.; Ku, C.S. Pyrolysis GC-MS analysis of tars formed during the aging of wood and bamboo crude vinegars. J. Wood Sci. 2010, 56, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusic, J.; Giannoni, T.; Zikeli, F.; Tamantini, S.; Pierpaoli, V.; Barbanera, M.; Grilc, M.; Tofani, G.; Romagnoli, M. Chemical and thermogravimetric characterization of chestnut tree biomass waste: Towards sustainable resource utilization in the tannin industry. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2025, 83, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.S.; Kashyap, A.S.; Tripathi, R.; Gupta, S.; Dutta, P.; Harish; Singh, R.; Swapnil, P. Unravelling the multifarious role of wood vinegar made from waste biomass in plant growth promotion, biotic stress tolerance, and sustainable agriculture. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2025, 185, 106851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Geng, K.; Li, B.; Li, S.; Gustave, W.; Wang, J.; Jeyakumar, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Enhancement of nutrient use efficiency with biochar and wood vinegar: A promising strategy for improving soil productivity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosti, A.; Nazeer, S.; Del Vecchio, L.; Leto, L.; Di Fazio, A.; Hadj-Saadoun, J.; Levante, A.; Rinaldi, M.; Dhenge, R.; Lazzi, C.; et al. Effect of biochar and wood distillate on vegeto-productive performances of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants, var. Solarino, grown in soilless conditions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Liu, J.; Luo, T.; Zhang, K.; Khan, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, T.; Yuan, B.; Peng, X.; Hu, L. Wood Vinegar Impact on the Growth and Low-Temperature Tolerance of Rapeseed Seedlings. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carril, P.; Bianchi, E.; Cicchi, C.; Coppi, A.; Dainelli, M.; Gonnelli, C.; Loppi, S.; Pazzagli, L.; Colzi, I. Effects of wood distillate (pyroligneous acid) on the yield parameters and mineral composition of three leguminous crops. Environments 2023, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Azarnejad, N.; Carril, P.; Celletti, S.; Loppi, S. Boosting the resilience to drought of crop plants using wood distillate: A pilot study with lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, G.; Ashraf, M.; Nadeem, M.Y.; Rehman, R.S.; Thwin, H.M.; Shakoor, K.; Seleiman, M.F.; Alotaibi, M.; Yuan, B.Z. Exogenous application of wood vinegar improves rice yield and quality by elevating photosynthetic efficiency and enhancing the accumulation of total soluble sugars. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 218, 109306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Song, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Ge, Y. Root proteomics reveals the effects of wood vinegar on wheat growth and subsequent tolerance to drought stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Gu, S.; Liu, J.; Luo, T.; Khan, Z.; Zhang, K.; Hu, L. Wood vinegar as a complex growth regulator promotes the growth, yield, and quality of rapeseed. Agronomy 2021, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungkunkamchao, T.; Kesmala, T.; Pimratch, S.; Toomsan, B.; Jothityangkoon, D. Wood vinegar and fermented bioextracts: Natural products to enhance growth and yield of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Sci. Hortic. 2013, 154, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedeli, R.; Dichiara, M.; Carullo, G.; Tudino, V.; Gemma, S.; Butini, S.; Campiani, G.; Loppi, S. Unlocking the potential of biostimulants in sustainable agriculture: Effect of wood distillate on the nutritional profiling of apples. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, G.S.P.; Pimenta, A.S.; Feijó, F.M.C.; Aires, C.A.M.; de Melo, R.R.; dos Santos, C.S.; de Medeiros, L.C.D.; da Costa Monteiro, T.V.; Fasciotti, M.; de Medeiros, P.L.; et al. Antimicrobial impact of wood vinegar produced through co-pyrolysis of eucalyptus wood and aromatic herbs. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossel, R.V.; Behrens, T. Using data mining to model and interpret soil diffuse reflectance spectra. Geoderma 2010, 158, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallottino, F.; Antonucci, F.; Costa, C.; Bisaglia, C.; Figorilli, S.; Menesatti, P. Optoelectronic proximal sensing vehicle-mounted technologies in precision agriculture: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, U.; Mumtaz, R.; García-Nieto, J.; Hassan, S.A.; Zaidi, S.A.R.; Iqbal, N. Precision agriculture techniques and practices: From considerations to applications. Sensors 2019, 19, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinelli, P.; Romani, A.; Fierini, E.; Remorini, D.; Agati, G. Characterisation of the Polyphenol Content in the Kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) Exocarp for the Calibration of a Fruit-Sorting Optical Sensor. Phytochem. Anal. 2013, 24, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betemps, D.L.; Fachinello, J.C.; Galarça, S.P.; Portela, N.M.; Remorini, D.; Massai, R.; Agati, G. Non-Destructive Evaluation of Ripening and Quality Traits in Apples Using a Multiparametric Fluorescence Sensor. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS; Third ERTS Symposium; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Gamon, J.; Serrano, L.; Surfus, J.S. The photochemical reflectance index: An optical indicator of photosynthetic radiation use efficiency across species, functional types, and nutrient levels. Oecologia 1997, 112, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuelas, J.; Pinol, J.; Ogaya, R.; Filella, I. Estimation of plant water concentration by the reflectance water index WI (R900/R970). Int. J. Remote Sens. 1997, 18, 2869–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Grignetti, A.; Liu, S.; Casacchia, R.; Salvatori, R.; Pietrini, F.; Centritto, M. Associated changes in physiological parameters and spectral reflectance indices in olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves in response to different levels of water stress. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 29, 1725–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ghozlen, N.; Cerovic, Z.G.; Germain, C.; Toutain, S.; Latouche, G. Non-destructive optical monitoring of grape maturation by proximal sensing. Sensors 2010, 10, 10040–10068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Viña, A.; Ciganda, V.; Rundquist, D.C.; Arkebauer, T.J. Remote Estimation of Canopy Chlorophyll Content in Crops. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L08403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savi, S.; Poni, S.; Moncalvo, A.; Frioni, T.; Rodschinka, I.; Arata, L.; Gatti, M. Destructive and optical non-destructive grape ripening assessment: Agronomic comparison and cost-benefit analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, R.G. Reporting of objective color measurements. HortScience 1992, 27, 1254–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, S.; Leisso, R.; Giordani, L.; Kalcsits, L.; Musacchi, S. Crop load influences fruit quality, nutritional balance, and return bloom in ‘Honeycrisp’ apple. HortScience 2016, 51, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruccelli, R.; Bonetti, A.; Ciaccheri, L.; Ieri, F.; Ganino, T.; Faraloni, C. Evaluation of the fruit quality and phytochemical compounds in peach and nectarine cultivars. Plants 2023, 12, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soppelsa, S.; Kelderer, M.; Casera, C.; Bassi, M.; Robatscher, P.; Matteazzi, A.; Andreotti, C. Foliar applications of bi-ostimulants promote growth, yield and fruit quality of strawberry plants grown under nutrient limitation. Agronomy 2019, 9, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltaniband, V.; Brégard, A.; Gaudreau, L.; Dorais, M. Biostimulants Promote Plant Development, Crop Productivity, and Fruit Quality of Protected Strawberries. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussos, P.A.; Denaxa, N.-K.; Damvakaris, T. Strawberry fruit quality attributes after application of plant growth stimulating compounds. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 119, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, A.; Conde, A.; Serôdio, J.; De Vos, R.C.H.; Cunha, A. Fruit Photosynthesis: More to Know about Where, How and Why. Plants 2023, 12, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Walsh, É.; Dieli, C.; O’HAlloran, O.; Awan, Z.A.; Gargan, A.; Landeta-Manzano, B.; Priyadarshini, A.; Foley, L.; Gaffney, M.T.; et al. Impact of biostimulant use in agricultural crops (strawberries, leafy greens and mushrooms) under different horticultural cropping systems: A systematic review. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2025, 187, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardarelli, M.; El Chami, A.; Rouphael, Y.; Ciriello, M.; Bonini, P.; Erice, G.; Cirino, V.; Basile, B.; Corrado, G.; Choi, S.; et al. Plant biostimulants as natural alternatives to synthetic auxins in strawberry production: Physiological and metabolic insights. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1337926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, S.E.; Smillie, R.M.; Davies, W.J. Photosynthetic activities of vegetative and fruiting tissues of tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, V.; Kirichenko, E.; Logvinov, A.; Azarov, A.; Rajput, V.D.; Chokheli, V.; Chalenko, E.; Yadronova, O.; Varduny, T.; Krasnov, V.; et al. Ultrastructure, CO2 Assimilation and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Kinetics in Photosynthesizing Glycine max Callus and Leaf Mesophyll Tissues. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbulsky, M.F.; Peñuelas, J.; Gamon, J.A.; Inoue, Y.; Filella, I. The photochemical reflectance index (PRI) and the remote sensing of leaf, canopy and ecosystem radiation use efficiencies: A review and meta-analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H.; Hakala, M.; Pelkkikangas, A.M.; Lapveteläinen, A. Sugars and acids of strawberry varieties. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2000, 212, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Plotto, A.; Bai, J.; Whitaker, V. Volatiles influencing sensory attributes and Bayesian modeling of the soluble solids-sweetness relationship in strawberry. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 640704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunter, B.; Unal, O.B.; Keskin, S.; Hatterman-Valenti, H.; Kaya, O. Comparison of the sugar and organic acid components of seventeen table grape varieties produced in Ankara (Türkiye): A study over two consecutive seasons. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1321210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomada, S.; Agati, G.; Serni, E.; Michelini, S.; Lazazzara, V.; Pedri, U.; Sanoll, C.; Matteazzi, A.; Robatscher, P.; Haas, F. Non-destructive Fluorescence Sensing for Assessing Microclimate, Site and Defoliation Effects on Flavonol Dynamics and Sugar Prediction in Pinot blanc Grapes. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-da-Silva, F.; de Pascual-Teresa, S.; Rivas-Gonzalo, J.C.; Santos-Buelga, C. Identification of anthocyanin pigments in strawberry (cv. Camarosa) by LC–DAD–ESI/MS. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2002, 214, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesser, M.; Hoffmann, T.; Bellido, M.L.; Rosati, C.; Fink, B.; Kurtzer, R.; Aharoni, A.; Munoz-Blanco, J.; Schwab, W. Redirection of Flavonoid Biosynthesis through the Down-Regulation of Anthocyanidin Reductase in Ripening Strawberry Fruit. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1528–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, H.; Takada, M.; Yoshida, Y. Pelargonidin 3-O-(6-O-Malonyl-β-D-glucoside) in Fragaria × ananassa Duch. cv. Nyoho. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1995, 59, 1157–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; D’Onofrio, C.; Ducci, E.; Cuzzola, A.; Remorini, D.; Tuccio, L.; Lazzini, F.; Mattii, G. Potential of a multiparametric optical sensor for determining in situ the maturity components of red and white Vitis vinifera wine grapes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12211–12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H.; Ougham, H. The stay-green trait. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 3889–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Guo, Z.; Li, H.; Mu, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; Yang, T.; Cai, H.; Wang, Q.; Lü, P.; et al. Integrated Metabolic, Transcriptomic and Chromatin Accessibility Analyses Provide Novel Insights into the Competition for Anthocyanins and Flavonols Biosynthesis During Fruit Ripening in Red Apple. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 975356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tang, L.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; et al. A Novel R2R3–MYB Transcription Factor FaMYB10-like Promotes Light-Induced Anthocyanin Accumulation in Cultivated Strawberry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangena, P.; Molatudi, N. Biostimulants: Emerging Role in Sustainable Agriculture for Crop Adaptation and Mitigation Against Abiotic Stress and Food Security. In Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedeli, R.; Vannini, A.; Celletti, S.; Maresca, V.; Munzi, S.; Cruz, C.; Loppi, S. Foliar application of wood distillate boosts plant yield and nutritional parameters of chickpea. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2023, 182, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Giordano, M.; Cardarelli, M.; Cozzolino, E.; Mori, M.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Bonini, P.; Colla, G. Plant- and seaweed-based extracts increase yield but differentially modulate nutritional quality of greenhouse spinach through biostimulant action. Agronomy 2018, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Yield (g) | Fruit Weight (g) | Length (mm) | Diameter (mm) | Number of Fruits per Plant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 174.9 ± 1.9 c | 11.3 ±0.5 a | 27.4 ±5.7 a | 34.2 ± 7.4 a | 13.3 ± 0.9 b |

| WD1 | 171.5 ± 1.9 c | 11.5 ± 0.5 a | 28.2 ± 4.6 a | 34.3 ± 6.3 a | 15.0 ± 0.5 ab |

| WD2 | 196.1 ± 1.8 a | 11.5 ± 0.6 a | 26.9 ± 6.0 a | 34.8 ± 8.3 a | 19.0 ± 1.6 a |

| IBE-CNR | 183.8 ± 2.2 b | 11.4 ± 0.4 a | 28.4 ± 4.7 a | 34.0 ± 5.1 a | 15.7 ± 0.8 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Palchetti, V.; Beltrami, S.; Alderotti, F.; Grieco, M.; Marino, G.; Agati, G.; Lo Piccolo, E.; Centritto, M.; Ferrini, F.; Gori, A.; et al. Integrating Proximal Sensing Data for Assessing Wood Distillate Effects in Strawberry Growth and Fruit Development. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010017

Palchetti V, Beltrami S, Alderotti F, Grieco M, Marino G, Agati G, Lo Piccolo E, Centritto M, Ferrini F, Gori A, et al. Integrating Proximal Sensing Data for Assessing Wood Distillate Effects in Strawberry Growth and Fruit Development. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010017

Chicago/Turabian StylePalchetti, Valeria, Sara Beltrami, Francesca Alderotti, Maddalena Grieco, Giovanni Marino, Giovanni Agati, Ermes Lo Piccolo, Mauro Centritto, Francesco Ferrini, Antonella Gori, and et al. 2026. "Integrating Proximal Sensing Data for Assessing Wood Distillate Effects in Strawberry Growth and Fruit Development" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010017

APA StylePalchetti, V., Beltrami, S., Alderotti, F., Grieco, M., Marino, G., Agati, G., Lo Piccolo, E., Centritto, M., Ferrini, F., Gori, A., Montesano, V., & Brunetti, C. (2026). Integrating Proximal Sensing Data for Assessing Wood Distillate Effects in Strawberry Growth and Fruit Development. Horticulturae, 12(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010017