Linking Grain Mineral Content to Pest and Disease Resistance, Agro-Morphological Traits, and Bioactive Compounds in Peruvian Coffee Germplasm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Site

2.2. Reagents

2.3. Agro-Morphological Characterization and Assessment of Pests and Diseases

2.4. Spectrophotometric Analysis of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity

2.4.1. Aqueous Extraction

2.4.2. Total Phenolics and Total Flavonoids

2.4.3. Antioxidant Activity Assays

2.5. HPLC Analysis of Secondary Metabolites

2.6. Ash Content and Mineral Composition

2.7. Multi-Trait Functional Selection Indices

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Mineral Content in Green Coffee and Incidence of Pests and Diseases

3.2. Association Between Mineral Content and Pest/Disease Incidence

3.3. Association Between Mineral Content and Agro-Morphological Parameters

3.4. Association Between Mineral Content and Bioactive Compounds

3.5. Hierarchical Clustering

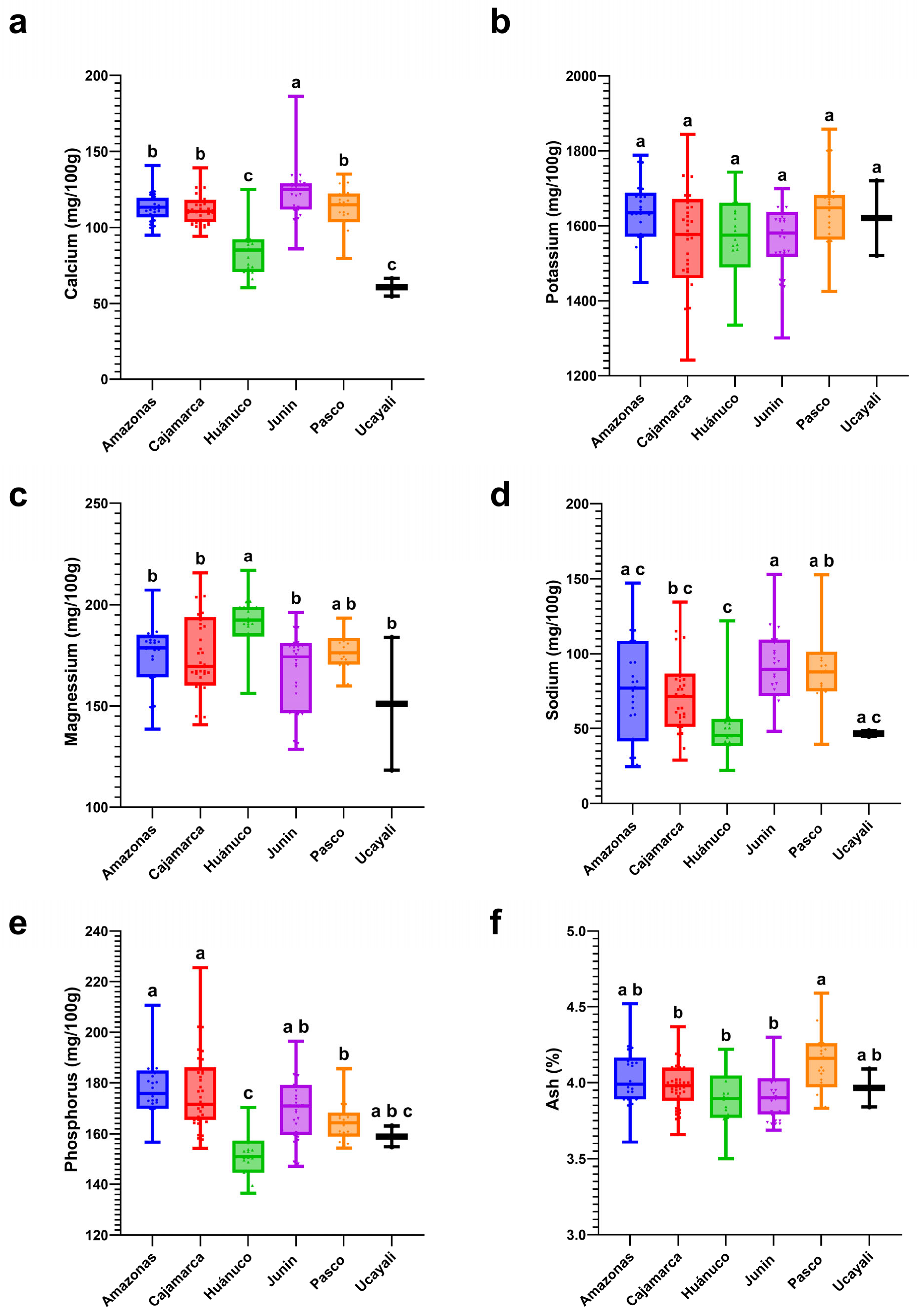

3.6. Regional Profiles of Macro- and Micronutrients

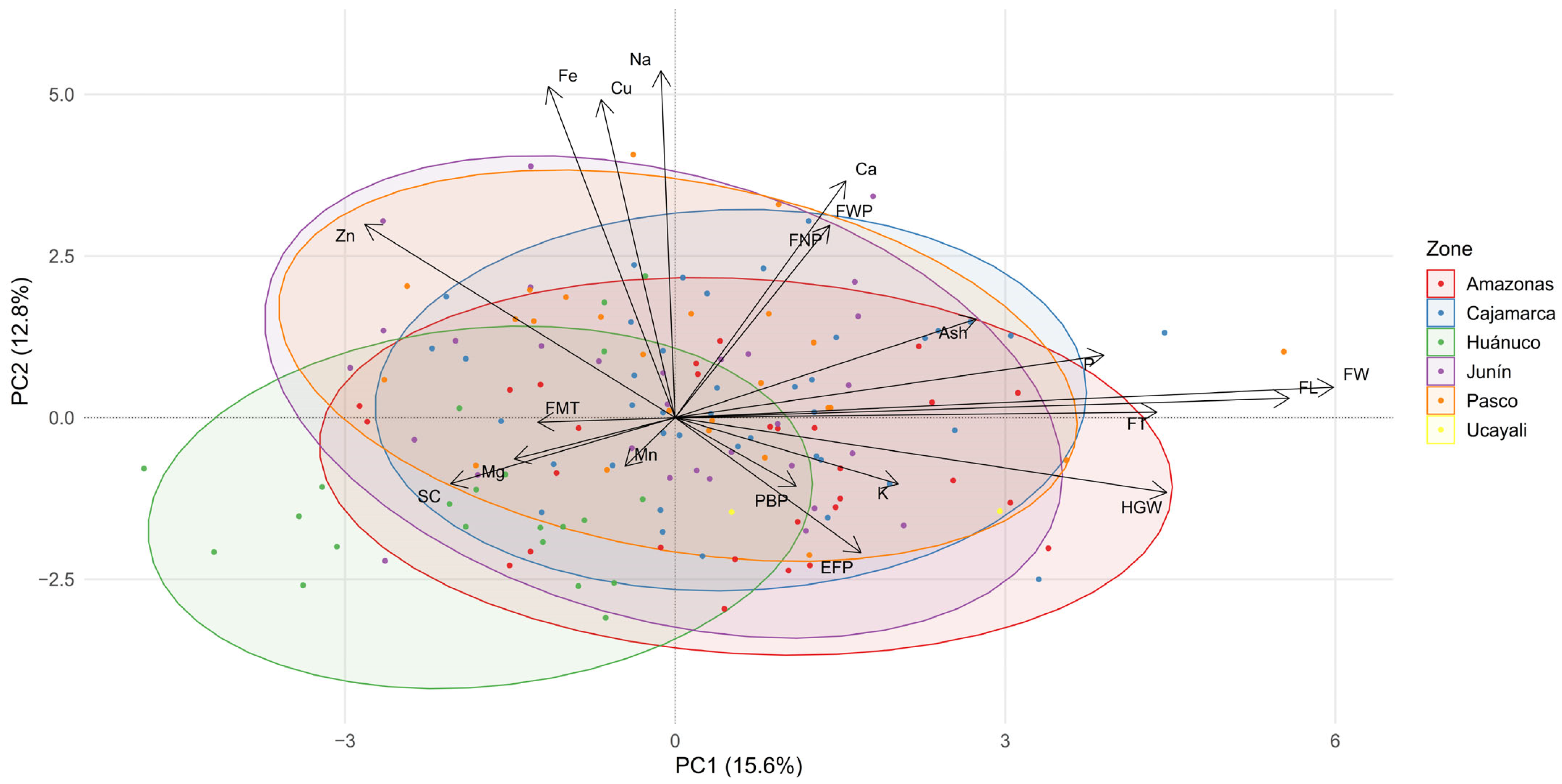

3.7. Multivariate Analysis of Resistance to Berry Borer and Leaf Rust

3.8. Promising Accessions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spiral, J.; Leroy, T.; Paillard, M.; Petiard, V. Transgenic Coffee (Coffea Species). In Transgenic Trees; Bajaj, Y.P.S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; Volume 44, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Legesse, A. Climate Change Effect on Coffee Yield and Quality: A Review. Int. J. For. Hortic. 2019, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deribe, H. Review on Factors Which Affect Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Quality in South Western, Ethiopia. Int. J. For. Hortic. 2019, 5, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Oancea, C.-N.; Neacșu, S.M.; Olteanu, G.; Cîrțu, A.-T.; Hîncu, L.; Gheonea, T.C.; Stanciu, T.I.; Rogoveanu, I.; Hashemi, F.; et al. Evaluation of Non-Alcoholic Beverages and the Risk Related to Consumer Health among the Romanian Population. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusni, Y.; Yusuf, H.; Murzalina, C. Coffee Drinking Patterns and Its Potential Impact on Body Weight and Body Mass Index among Young Adults. Med. J. Armed Forces India, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldemichael, G. Review on Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Genetic Diversity Studies Using Molecular Markers. J. Plant Sci. 2023, 11, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Monroy, S.; Castro Brindis, R.; Pérez Moreno, J.; Valdés Velarde, E. Diversidad Endomicorrícica En Plantas de Café (Coffea arabica L.) Infestadas Con Roya (Hemileia vastatrix). Nova Sci. 2019, 11, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón-Mera, A.M.; Corrales, D.C.; Peñuela Mesa, G.A. A Systematic Mapping Study of Coffee Quality throughout the Production-to-Consumer Chain. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 8019251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutouleas, A.; Collinge, D.B.; Ræbild, A. Alternative Plant Protection Strategies for Tomorrow’s Coffee. Plant Pathol. 2023, 72, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Castillo, N.E.; Aguilera Acosta, Y.; Parra-Arroyo, L.; Martínez-Prado, M.A.; Rivas-Galindo, V.M.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Bonaccorso, A.D.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Towards an Eco-Friendly Coffee Rust Control: Compilation of Natural Alternatives from a Nutritional and Antifungal Perspective. Plants 2022, 11, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Resende, M.L.; Pozza, E.A.; Reichel, T.; Botelho, D.M.S. Strategies for Coffee Leaf Rust Management in Organic Crop Systems. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ramirez, N.; Bianchi, F.J.J.A.; Manzano, M.R.; Dicke, M. Ecology and Management of the Coffee Berry Borer (Hypothenemus hampei): The Potential of Biological Control. BioControl 2024, 69, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizábal, L.F.; Johnson, M.A.; Mariño, Y.A.; Bayman, P.; Wright, M.G. Establishing an Integrated Pest Management Program for Coffee Berry Borer (Hypothenemus hampei) in Hawaii and Puerto Rico Coffee Agroecosystems: Achievements and Challenges. Insects 2023, 14, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, S.A.; Guedes, R.N.C.; dos Santos, M.P.; da Costa, D.R.; Moreira, A.A.; Matsumoto, S.N.; Lemos, O.L.; Castellani, M.A. Profile of Coffee Crops and Management of the Neotropical Coffee Leaf Miner, Leucoptera coffeella. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.F.; Franzin, M.L.; Perez, A.L.; Schmidt, J.M.; Venzon, M. Is Ceraeochrysa Cubana a Coffee Leaf Miner Predator? Biol. Control 2021, 160, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucho, R.L.; Marín-Ramírez, G.A.; Gaitan, A. Integrated Disease Management for the Sustainable Production of Colombian Coffee. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góngora, C.E.; Gil, Z.N.; Constantino, L.M.; Benavides, P. Sustainable Strategies for the Control of Pests in Coffee Crops. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, H.P.; Vieira, H.D.; Gontijo, I.; Marques, I.; Ramalho, J.C.; Partelli, F.L. Nutrient Dynamics in the Berry, Bean, and Husk of Six Coffea canephora Genotypes throughout Fruit Maturation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Suoza Barros, V.M.; Martins, L.D.; Rodrigues, W.N.; Ferreira, D.S.; Christo, B.F.; do Amaral, J.F.T.; Tomaz, M.A. Combined Doses of Nitrogen and Phosphorus in Conilon Coffee Plants: Changes in Absorption, Translocation and Use in Plant Compartments. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 45, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; da Silva, C.A.; Dubberstein, D.; Dias, J.R.M.; Vieira, H.D.; Partelli, F.L. Genetic Diversity Based on Nutrient Concentrations in Different Organs of Robusta Coffee. Agronomy 2022, 12, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.V.; Pilbeam, D.J. Handbook of Plant Nutrition, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Furtado, A.; Smyth, H.E.; Henry, R.J. Influence of Genotype and Environment on Coffee Quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 57, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, M.S.; Resende, L.S.; Pozza, E.A.; Netto, P.M.; de Cassia Roteli, K.; Guimarães, R.J. Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium Fertilization on the Incidence of Brown Eye Spot in Coffee Crop in Vegetative Stage. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2022, 47, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, L.S.; Vilela, M.S.; Pozza, E.A.; Castanheira, D.T.; Voltolini, G.B.; da Silva, L.C.; Botrel, É.P.; Diotto, A.V. Sustainable Coffee Leaf Rust Management: The Role of Soil Covering, Conditioners and Controlled-Release Fertilizers. Plant Pathol. 2025, 74, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Builes, V.H.; Küsters, J.; Thiele, E.; Lopez-Ruiz, J.C. Physiological and Agronomical Response of Coffee to Different Nitrogen Forms with and without Water Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgo, L.; Rabêlo, F.H.S.; Marchiori, P.E.R.; Guilherme, L.R.G.; Guerra-Guimarães, L.; Resende, M.L.V. de Impact of Drought, Heat, Excess Light, and Salinity on Coffee Production: Strategies for Mitigating Stress Through Plant Breeding and Nutrition. Agriculture 2024, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; He, G.; Yang, T.; Kong, C. Effects of Different Fertilization Treatments on Coffee Bean Quality and Rhizosphere Microorganisms. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2025, 71, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidan, I.R.; da Silva Ferreira, M.F.; Pereira do Couto, D.; Santos, J.G.; Silva, M.A.; Canal, G.B.; de Oliviera Bernardes, C.; Azevedo, C.F.; Ferreira, A. Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Traits Related to Development, Abiotic and Biotic Stress Resistance in Coffea canephora. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 341, 114004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, T.; de Resende, M.L.V.; Monteiro, A.C.A.; Freitas, N.C.; dos Santos Botelho, D.M. Constitutive Defense Strategy of Coffee Under Field Conditions: A Comparative Assessment of Resistant and Susceptible Cultivars to Rust. Mol. Biotechnol. 2022, 64, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, J.; Jeong, B.R. Drenched Silicon Suppresses Disease and Insect Pests in Coffee Plant Grown in Controlled Environment by Improving Physiology and Upregulating Defense Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozza, E.A.; Pozza, A.A.A. Coffee Plant Diseases Affected by Nutritional Balance. Coffee Sci. 2023, 18, e182086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Builes, V.H.; Küsters, J.; Thiele, E.; Leal-Varon, L.A. Boron Nutrition in Coffee Improves Drought Stress Resistance and, Together with Calcium, Improves Long-Term Productivity and Seed Composition. Agronomy 2024, 14, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Fedenia, L.N.; Sharifan, H.; Ma, X.; Lombardini, L. Effects of Foliar Application of Zinc Sulfate and Zinc Nanoparticles in Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, L.O.; Mattos, D., Jr.; Jacobassi, R.C.; Petená, G.; Quaggio, J.A.; Boaretto, R.M. Characterization and Use Efficiency of Sparingly Soluble Fertilizer of Boron and Zinc for Foliar Application in Coffee Plants. Bragantia 2021, 80, e3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Viana, G.; Brandão Santana, D.; de Almeida Pereira, L.; Tieghi, H.; Fortes da Silva, V.; Ernesto Bernardes Ayer, J.; Ferreira Dias, D.; Gomes Soares, M.; Aparecida Chagas-Paula, D.; Luiz Mincato, R.; et al. Association between Higher Coffee Quality, Bioactive Chemical Profile and Sustainable Practices. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1645329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, G.L.; Delgado, J.A.; Ippolito, J.A.; Johnson, J.J.; Kluth, D.L.; Stewart, C.E. Wheat Grain Micronutrients and Relationships with Yield and Protein in the U.S. Central Great Plains. Field Crops Res 2022, 279, 108453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konlan, S.; Dogbatse, J.A.; Aidoo, M.K.; Ntiamoah, D.D.; Adu-Yeboah, P.; Quaye, A.K.; Anyidoho, E.K.; Pobee, P.; Segbefia, M.A. Growth and Yield Response of Coppiced Robusta Coffee to Application of Different Combinations of Nitrogen and Potassium. Int. J. Agron. 2025, 2025, 6278184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Liu, X.; Sun, W.; Cui, N.; Guo, J.; Chen, H.; Huang, W. Fertilizer Optimization Combined with Coffee Husk Returning to Improve Soil Environmental Quality and Young Coffee Tree Growth. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 650–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.M.; Graham, R.D. The Role of Nutrition in Crop Resistance and Tolerance to Diseases. In Mineral Nutrition of Crops: Fundamental Mechanisms and Implications; Rengel, Z., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 169–204. ISBN 9781040291979. [Google Scholar]

- Narvekar, A.S.; Tharayil, N. Nitrogen Fertilization Influences the Quantity, Composition, and Tissue Association of Foliar Phenolics in Strawberries. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 613839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Chaoqun, C.; Luo, L.; Asghar, M.A.; Li, L.; Shoaib, N.; Yin, C. Combined Application of Organic and Chemical Fertilizers Improved the Catechins and Flavonoids Biosynthesis Involved in Tea Quality. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvera-Pablo, C.; Julca, A.; Rivera-Ashqui, T.; Silva-Paz, R. Impact of Humic Acids and Biofertilizers on Yield and Sensory Quality of Organic Coffee Varieties in Peruvian Plantations. Int. J. Agric. Biosci. 2024, 13, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashwanth, B.S.; Biswal, V.L.; Suhas, R.; Chaudhari, S.R.; Naveen, J.; Murthy, P.S. Fortification of Coffee with Iron Compounds to Enhance Its Micronutrient Profile. Food Chem. 2025, 489, 144964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Malta, M.R.; Gonçalves, M.G.M.; Borém, F.M.; Pozza, A.A.A.; Martinez, H.E.P.; de Souza, T.L.; Chagas, W.F.T.; de Melo, M.E.A.; Oliveira, D.P.; et al. Chloride Applied via Fertilizer Affects Plant Nutrition and Coffee Quality. Plants 2023, 12, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Brinkley, S.; Smith, E.; Sela, A.; Theisen, M.; Thibodeau, C.; Warne, T.; Anderson, E.; Van Dusen, N.; Giuliano, P.; et al. Climate Change and Coffee Quality: Systematic Review on the Effects of Environmental and Management Variation on Secondary Metabolites and Sensory Attributes of Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 708013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, R.; Kambale, J.-L.; Tas, A.-S.; Katshela, B.N.; Tshimi, E.A.; Wyffels, F.; Vandelook, F.; Honnay, O.; Stoffelen, P. Agro-Morphological Characterization of Coffea canephora (Robusta) Genotypes from the INERA Yangambi Coffee Collection, Democratic Republic of the Congo 2024. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-5305587/v1 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Paredes-Espinosa, R.; Gutiérrez-Reynoso, D.L.; Atoche-Garay, D.; Mansilla-Córdova, P.J.; Abad-Romaní, Y.; Girón-Aguilar, C.; Flores-Torres, I.; Montañez-Artica, A.G.; Arbizu, C.I.; Guerra, C.A.A.; et al. Agro-morphological Characterization and Diversity Analysis of C Offea arabica Germplasm Collection from INIA, Peru. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 2877–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemira, H.; Medebesh, A.; Hassen Mehrez, K.; Hamadi, N. Effect of Fertilization on Yield and Quality of Arabica Coffee Grown on Mountain Terraces in Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 321, 112370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Espinelli, J.B., Jr.; Furlong, E.B.; Carapelli, R. Study on the Impact of Adopting Organic Practices on the Absorption and Extractability of Cu and Zn in Commercial Coffee Samples. Food Humanit. 2024, 3, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cheng, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, H.; Cui, N.; Zhao, L. Optimizing Drip Fertigation at Different Periods to Improve Yield, Volatile Compounds and Cup Quality of Arabica Coffee. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1148616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NTP 209.318; Café. Buenas Prácticas Agrícolas Para El Cultivo y Beneficio Del Café. Instituto Nacional de Calidad (INACAL): Lima, Peru, 2020.

- Romero, J.M.; Camilo, J. Manual de Produccion Sostenible de Cafe En La Republica Dominicana; Instituto Interamericano de Cooperacion para la Agricultura (IICA): San Jose, Costa Rica, 2019; ISBN 9789292488734. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Innovacion Agraria. Manual Del Cultivo de Cafe En El VRAEM; INIA: Lima, Peru, 2022; ISBN 978-9972-44-085-4. [Google Scholar]

- International Plant Genetic Resources Institute. Descriptores Del Café (Coffea Spp. y Psilanthus Spp.); IPGRI: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agraria. Guía Para El Cumplimiento de La Meta 36: Implementación de Acciones En El Manejo Integrado de Plagas de Cultivos Priorizados. 2017. Available online: https://www.senasa.gob.pe/senasa/descargasarchivos/2017/05/GUIA-META-36.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Total Phenolic Content in Extracts (AOAC 2017.13); Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abdeltaif, S.A.; SirElkhatim, K.A.; Hassan, A.B. Estimation of Phenolic and Flavonoid Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Spent Coffee and Black Tea (Processing) Waste for Potential Recovery and Reuse in Sudan. Recycling 2018, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, M.; Kang, W.H. Antioxidant Activity, Total Polyphenol, Flavonoid and Tannin Contents of Fermented Green Coffee Beans with Selected Yeasts. Fermentation 2019, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressani, A.P.P.; Batista, N.N.; Ferreira, G.; Martinez, S.J.; Simão, J.B.P.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Characterization of Bioactive, Chemical, and Sensory Compounds from Fermented Coffees with Different Yeasts Species. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sualeh, A.; Tolessa, K.; Mohammed, A. Biochemical Composition of Green and Roasted Coffee Beans and Their Association with Coffee Quality from Different Districts of Southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, A.R.; Park, K.W.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Han, J. Influence of Roasting Conditions on the Antioxidant Characteristics of Colombian Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Beans. J. Food Biochem. 2014, 38, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, M.G.S.; Cruz, L.T.; Bertges, F.S.; Húngaro, H.M.; Batista, L.R.; da Silva, S.S.; Fonseca, M.J.V.; Rodarte, M.P.; Vilela, F.M.P.; Amaral, M. da P.H. do Enhancement of Antioxidant Properties from Green Coffee as Promising Ingredient for Food and Cosmetic Industries. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Ash of Roasted Coffee. In Official Methods of Analysis, 20th ed.; AOAC 920.93-1920; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Metals in Plants. Atomic Absortion Spectrophotometric Method. In Official Methods of Analysis, 20th ed.; AOAC 975.03; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Phosphorous in Animal Feed. In Official Methods of Analysis, 20th ed.; AOAC 965.17; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas Arellano, J.; Escamilla Prado, E.; Ruiz Rosado, O. Relationship of Soil Nutrients to Physical and Sensorial Characteristics of Organic Coffee. Rev. Terra Latinoam. 2008, 26, 375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, H.E.P.; Clemente, J.M.; De Lacerda, J.S.; Neves, Y.P.; Pedrosa, A.W. Nutrição Mineral Do Cafeeiro e Qualidade Da Bebida. Rev. Ceres 2014, 61, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.C.S.; Burgos, E.R.; Bautista, E.H.D. Efecto de Las Condiciones de Cultivo, Las Características Químicas Del Suelo y El Manejo de Grano En Los Atributos Sensoriales de Café (Coffea arabica L.) En Taza. Acta Agron. 2015, 64, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Merino, F.C. Concentracion de Macronutrimentos y Micronutrimentos En Granos de Café (Coffea Sp.) de Diferentes Origenes. Agro Product. 2018, 11, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harelimana, A.; Rukazambuga, D.; Hance, T. Pests and Diseases Regulation in Coffee Agroecosystems by Management Systems and Resistance in Changing Climate Conditions: A Review. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 129, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Q.; Du, X.; Chen, T.; Taha, M.F. Impact of Nitrogen on Downy Mildew Infection and Its Effects on Growth and Physiological Traits in Early Growth Stages of Cucumber. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, J.M.; Martinez, H.E.P.; Pedrosa, A.W.; Poltronieri Neves, Y.; Cecon, P.R.; Jifon, J.L. Boron, Copper, and Zinc Affect the Productivity, Cup Quality, and Chemical Compounds in Coffee Beans. J. Food Qual. 2018, 2018, 7960231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, R.A.N.; Guimarães, R.J.; de Carvalho, J.G. Crescimento e Teor Foliar de Nutrientes Em Cafeeiro Decorrente Da Omissao Isolada e Simultanea de Ca, B, Cu e Zn. Coffee Sci. 2008, 3, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Carmo, D.D.; Nannetti, D.C.; Lacerda, T.M.; Nannetti, A.N.; Santo, D.D.E. Micronutrients in Soil and Leaf of Coffee Plants under an Agroforest System in the South of Minas Gerais. Coffee Sci. 2012, 7, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Negesa, H.; Gidisa, G.; Wubshet, Z.; Alemayehu, D.; Belachew, K.; Merga, W.; Beksisa, L.; Merga, D.; Zakir, M. Evaluating Lowland Coffee Genotypes against Leaf Rust and Wilt Diseases in Southwestern Ethiopia. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1560091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, C.D.P.; Pozza, E.A.; Pozza, A.A.A.; Elmer, W.H.; Pereira, A.B.; da Silva Gomes Guimarães, D.; Monteiro, A.C.A.; de Rezende, M.L.V. Boron, Zinc and Manganese Suppress Rust on Coffee Plants Grown in a Nutrient Solution. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 156, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, E.R.; Oliveira, J.A.; Reis, L.V.; Ferreira, T.F. Mn Foliar Sobre a Qualidade Sanitária e Lignina de Sementes de Soja Convencional e Resistente Ao Glifosato. Rev. Ciência Agronômica 2015, 46, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadley, M.; Brown, P.; Cakmak, I.; Rengel, Z.; Zhao, F. Function of Nutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 191–248. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, S.; Ali Wani, O.; Lone, J.K.; Manhas, S.; Kour, N.; Alam, P.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, P. Reactive Oxygen Species in Plants: From Source to Sink. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, S.; Höller, S.; Meier, B.; Peiter, E. Manganese in Plants: From Acquisition to Subcellular Allocation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 517877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujicic, J.; Allen, A.R. Manganese Superoxide Dismutase: Structure, Function, and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Hause, B. Jasmonates: Biosynthesis, Perception, Signal Transduction and Action in Plant Stress Response, Growth and Development. An Update to the 2007 Review in Annals of Botany. Ann. Bot. 2013, 111, 1021–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, S.T.V.; Fernandes, F.L.; Demuner, A.J.; Picanço, M.C.; Guedes, R.N.C. Leaf Alkaloids, Phenolics, and Coffee Resistance to the Leaf Miner Leucoptera coffeella (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2010, 103, 1438–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, S.T.V.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Demuner, A.J.; Lima, E.R. Effect of Coffee Alkaloids and Phenolics on Egg-Laying by the Coffee Leaf Miner Leucoptera coffeella. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2008, 98, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, J.; Motta, I.O.; Vidal, L.A.; Nascimento, E.F.M.B.; Bilio, J.; Pupe, J.M.; Veiga, A.; Carvalho, C.; Lopes, R.B.; Rocha, T.L.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of the Coffee Leaf Miner Leucoptera coffeella (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae)—A Major Pest for the Coffee Crop in Brazil and Others Neotropical Countries. Insects 2021, 12, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushmitha, S.; Ravi, G.; Banerjee, S.; Pramanik, A. Biochemical Profiling of Plant Defense Mechanisms against Spodoptera Frugiperda (J.E. Smith) Infestation in Selected Host Species. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.P.; Londe, V.; Bueno, A.P.; Barbosa, J.S.; Corrêa, T.L.; Soeltl, T.; Maia, M.; Pinto, V.D.; de França Dueli, G.; de Sousa, H.C.; et al. Plant Defense against Leaf Herbivory Based on Metal Accumulation: Examples from a Tropical High Altitude Ecosystem. Plant Species Biol. 2017, 32, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War, A.R.; Paulraj, M.G.; Ahmad, T.; Buhroo, A.A.; Hussain, B.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Sharma, H.C. Mechanisms of Plant Defense against Insect Herbivores. Plant Signal Behav. 2012, 7, 1306–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Huang, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhou, H.; Adeleye, A.S.; Keller, A.A. 1H NMR and GC-MS Based Metabolomics Reveal Defense and Detoxification Mechanism of Cucumber Plant under Nano-Cu Stress. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2000–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Jaramillo, Y.A.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Sandoval-Rangel, A.; Cabrera-De la Fuente, M.; González-Morales, S.; Narro, A.; Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, U. Complejo PVA-Quitosán-NCu Mejora El Rendimiento y La Respuesta de Defensa En Tomate. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2021, 12, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, X. Recent Advances in Polyphenol Oxidase-Mediated Plant Stress Responses. Phytochemistry 2021, 181, 112588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabot, C.; Martos, S.; Llugany, M.; Gallego, B.; Tolrà, R.; Poschenrieder, C. A Role for Zinc in Plant Defense Against Pathogens and Herbivores. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 448458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, M.A.; De Barros, N.F.; De, M.M.; Gomes, M. Eucalypt Dieback and Nutritional Management of Plantation Forest: Physiological Aspects. Bosque 1995, 16, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, M.; Bocchini, M.; Orfei, B.; D’Amato, R.; Famiani, F.; Moretti, C.; Buonaurio, R. Zinc Phosphate Protects Tomato Plants against Pseudomonas Syringae Pv. Tomato. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2021, 128, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Marschner, P., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-12-384905-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, S.R. Zinc in Crop Production and Interaction with Phosphorus. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Wu, M.; Su, R.; Zhang, Z.; Chang, C.; Peng, Q.; Dong, Z.; Pang, J.; Lambers, H. Strong Phosphorus (P)-Zinc (Zn) Interactions in a Calcareous Soil-Alfalfa System Suggest That Rational P Fertilization Should Be Considered for Zn Biofortification on Zn-Deficient Soils and Phytoremediation of Zn-Contaminated Soils. Plant Soil 2021, 461, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, J.H.; Debona, D.; Zambolim, L.; Rodrigues, F.Á. Factors Influencing the Performance of Phosphites on the Control of Coffee Leaf Rust. Bragantia 2021, 80, e0221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, L.M.; Caixeta, E.T.; Barka, G.D.; Borém, A.; Zambolim, L.; Nascimento, M.; Cruz, C.D.; de Oliveira, A.C.B.; Pereira, A.A. Marker-Assisted Recurrent Selection for Pyramiding Leaf Rust and Coffee Berry Disease Resistance Alleles in Coffea arabica L. Genes 2023, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, M.A.G.; da Fonseca, A.F.A.; Volpi, P.S.; de Souza, L.C.; Comério, M.; Filho, A.C.V.; Riva-Souza, E.M.; Munoz, P.R.; Ferrão, R.G.; Ferrão, L.F.V. Genomic-Assisted Breeding for Climate-Smart Coffee. Plant Genome 2024, 17, e20321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góngora, C.E.; Tapias, J.; Jaramillo, J.; Medina, R.; González, S.; Restrepo, T.; Casanova, H.; Benavides, P. A Novel Caffeine Oleate Formulation as an Insecticide to Control Coffee Berry Borer, Hypothenemus hampei, and Other Coffee Pests. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.E.; Emche, S.; Shao, J.; Simpkins, A.; Summers, R.M.; Mock, M.B.; Ebert, D.; Infante, F.; Aoki, S.; Maul, J.E. Cultivation and Genome Sequencing of Bacteria Isolated from the Coffee Berry Borer (Hypothenemus hampei), With Emphasis on the Role of Caffeine Degradation. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 644768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.D.; Mezzomo, H.C. Phenotypic Parameters of Macromineral and Phenolic Compound Concentrations and Selection of Andean Bean Lines with Nutritional and Functional Properties. Ciência Agrotecnol. 2020, 44, e000320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, T.H.P.; Guimarães, P.T.G.; Neto, A.E.F.; Guerra, A.F.; Curi, N. Soil Phosphorus Dynamics and Availability and Irrigated Coffee Yield. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2011, 35, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, K.G.D.L.; Neto, A.E.F.; Guimarães, P.T.G.; Reis, T.H.P.; de Oliveira, C.H.C. Coffee yield and phosphate nutrition provided to plants by various phosphorus sources and levels. Ciência Agrotecnol. 2015, 39, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, T.H.P.; Neto, A.E.F.; Guimarães, P.T.G.; Guerra, A.F.; De Oliveira, C.H.C. Estado Nutricional e Frações Foliares de P No Cafeeiro Em Função Da Adubação Fosfatada. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2013, 48, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inthasan, J.; Dechjiraratthanasiri, C.; Taksa-Udom, N. Influence of Zinc and Boron on Nutrient Concentration in Coffee Leaf and on Coffee Yield in Northern Thailand. Maejo Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 15, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hasheminasab, K.S.; Shahbazi, K.; Marzi, M.; Zare, A.; Yeganeh, M.; Bazargan, K.; Kharazmi, R. A Study on Wheat Grain Zinc, Iron, Copper, and Manganese Concentrations and Their Relationship with Grain Yield in Major Wheat Production Areas of Iran. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Wilson, G.T.; Connolly, E.L. The Diverse Roles of FRO Family Metalloreductases in Iron and Copper Homeostasis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 82570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, H.; Tank, R.V.; Bennurmath, P.; Doni, S. Role of Zinc, Copper and Boron in Fruit Crops: A Review. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2018, 6, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, B.N.; Gacanja, W. A Study of the Shape and Size of Wet Parchment Coffee Beans. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1970, 15, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garuma, H.; Berecha, G.; Abedeta, C. Influence of Coffee Production Systems on the Occurrence of Coffee Beans Abnormality: Implication on Coffee Quality. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2015, 14, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wormer, T.M. Normal and Abnormal Development of Coffee Berries. Kenya Coffee 1964, 29, 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Alloway, B.J. Zinc in Soils and Crop Nutrition; International Fertilizer Industry Association: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S.B.; Husted, S. The Biochemical Properties of Manganese in Plants. Plants 2019, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aispuro-Pérez, A.; Pedraza-Leyva, F.J.; Ochoa-Acosta, A.; Arias-Gastélum, M.; Cárdenas-Torres, F.I.; Amezquita-López, B.A.; Terán, E.; Aispuro-Hernández, E.; Martínez-Téllez, M.Á.; Avena-Bustillos, R.J.; et al. A Functional Beverage from Coffee and Olive Pomace: Polyphenol-Flavonoid Content, Antioxidant, Antihyperglycemic Properties, and Mouse Behavior. Foods 2025, 14, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, L.; Maddaloni, L.; Prencipe, S.A.; Vinci, G. Bioactive Compounds in Different Coffee Beverages for Quality and Sustainability Assessment. Beverages 2023, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, M.N.; Ramirez-Martinez, J.R. Phenols and Caffeine in Wet-Processed Coffee Beans and Coffee Pulp. Food Chem. 1991, 40, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzafera, P. Mineral Nutrition and Caffeine Content in Coffee Leaves. Bragantia 1999, 58, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.L. Beyond Brown: Polyphenol Oxidases as Enzymes of Plant Specialized Metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A. Laccase: New Functions for an Old Enzyme. Phytochemistry 2002, 60, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, C.; Cherono, S.; Ntini, C.; Wang, L.; Han, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of Quality Characteristics in Main Commercial Coffee Varieties and Wild Arabica in Kenya. Food Chem. X 2022, 14, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.J.; Broadley, M.R. Biofortification of Crops with Seven Mineral Elements Often Lacking in Human Diets—Iron, Zinc, Copper, Calcium, Magnesium, Selenium and Iodine. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouis, H.E.; Saltzman, A. Improving Nutrition through Biofortification: A Review of Evidence from HarvestPlus, 2003 through 2016. Glob. Food Sec. 2017, 12, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito Mateus, M.P.; Tavanti, R.F.R.; Tavanti, T.R.; Santos, E.F.; Jalal, A.; Reis, A.R. dos Selenium Biofortification Enhances ROS Scavenge System Increasing Yield of Coffee Plants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.J.; Pablos, F.; González, A.G. Characterization of Green Coffee Varieties According to Their Metal Content. Anal. Chim. Acta 1998, 358, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chen, G.; Ma, F.; Yang, N.; de Melo Virginio Filho, E.; Fisk, I.D. Effects of Agro-Forestry Systems on the Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Green Coffee Beans. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1198802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes García, M.; Gómez Sánchez Prieto, I.; Espinoza Barrientos, C. Tablas Peruanas de Composición de Alimentos; Instituto Nacional de Salud: Lima, Peru, 2017; pp. 1–146. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Unit | Mean | SD | CV | Min | Max | P25 | Median | P75 | Skewness | Kurtosis | Shapiro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | mg/100 g | 1591.00 | 116.30 | 7.31% | 1242.00 | 1858.00 | 1526.00 | 1612.00 | 1670.00 | −0.45 | 0.21 | 0.0560 |

| Mg | mg/100 g | 175.90 | 18.87 | 10.73% | 118.30 | 217.00 | 164.30 | 178.40 | 189.30 | −0.47 | 0.02 | 0.0420 |

| P | mg/100 g | 169.60 | 15.00 | 8.84% | 136.60 | 225.50 | 159.30 | 168.40 | 179.30 | 0.60 | 0.88 | 0.0230 |

| Ca | mg/100 g | 110.10 | 18.78 | 17.05% | 54.73 | 186.30 | 101.90 | 111.50 | 121.80 | −0.26 | 1.98 | <0.0001 |

| Na | mg/100 g | 77.26 | 31.09 | 40.24% | 22.06 | 153.10 | 51.54 | 76.27 | 98.49 | 0.32 | −0.51 | 0.0150 |

| Mn | mg/100 g | 6.29 | 2.51 | 39.86% | 2.14 | 17.06 | 4.32 | 5.85 | 7.80 | 1.05 | 1.89 | <0.0001 |

| Fe | mg/100 g | 5.89 | 1.27 | 21.50% | 3.82 | 10.22 | 5.08 | 5.66 | 6.45 | 1.09 | 1.55 | <0.0001 |

| Cu | mg/100 g | 1.30 | 0.29 | 22.44% | 0.67 | 2.03 | 1.08 | 1.27 | 1.49 | 0.31 | −0.34 | 0.0960 |

| Zn | mg/100 g | 0.37 | 0.15 | 40.24% | 0.14 | 1.41 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 3.11 | 17.41 | <0.0001 |

| Ash | % | 3.99 | 0.20 | 4.93% | 3.50 | 4.59 | 3.84 | 3.97 | 4.12 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.2990 |

| CBB | % | 6.51 | 7.99 | 122.62 | 0.00 | 51.00 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 8.00 | 2.99 | 11.55 | <0.0001 |

| CLM | % | 25.83 | 15.31 | 59.30 | 0.00 | 84.00 | 14.00 | 24.00 | 34.00 | 0.87 | 1.23 | 0.0001 |

| CLR | % | 46.39 | 30.42 | 65.58 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 16.50 | 50.00 | 74.00 | −0.07 | −1.28 | <0.0001 |

| Rank | Zn + Fe | Ca + K + Mg + P + Zn + Fe | Pest Resistance | Agro-Morphologic | Bioactive | Combined | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PER1002279 | J | PER1002312 | P | PER1002229 | A | PER1002199 | C | PER1002290 | P | PER1002287 | J |

| 2 | PER1002285 | J | PER1002287 | J | PER1002261 | J | PER1002180 | C | PER1002289 | P | PER1002216 | C |

| 3 | PER1002287 | J | PER1002216 | C | PER1002301 | P | PER1002211 | C | PER1002292 | P | PER1002207 | C |

| 4 | PER1002291 | P | PER1002317 | H | PER1002318 | U | PER1002216 | C | PER1002184 | C | PER1002197 | C |

| 5 | PER1002309 | P | PER1002214 | C | PER1002239 | A | PER1002248 | A | PER1002193 | C | PER1002292 | P |

| 6 | PER1002310 | P | PER1002275 | J | PER1002303 | P | PER1002273 | J | PER1002197 | C | PER1002314 | H |

| 7 | PER1002312 | P | PER1002285 | J | PER1002325 | H | PER1002177 | C | PER1002205 | C | PER1002275 | J |

| 8 | PER1002317 | H | PER1002297 | P | PER1002336 | H | PER1002197 | C | PER1002222 | C | PER1002317 | H |

| 9 | PER1002182 | C | PER1002310 | P | PER1002273 | J | PER1002207 | C | PER1002276 | J | PER1002240 | A |

| 10 | PER1002215 | C | PER1002207 | C | PER1002277 | J | PER1002212 | C | PER1002287 | J | PER1002299 | P |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Choque-Incaluque, E.; Cueva-Carhuatanta, C.; Carrera-Rojo, R.P.; Maravi Loyola, J.; Hermoza-Gutiérrez, M.; Cántaro-Segura, H.; Fernández-Huaytalla, E.; Gutiérrez-Reynoso, D.L.; Quispe-Jacobo, F.; Ccapa-Ramirez, K. Linking Grain Mineral Content to Pest and Disease Resistance, Agro-Morphological Traits, and Bioactive Compounds in Peruvian Coffee Germplasm. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010015

Choque-Incaluque E, Cueva-Carhuatanta C, Carrera-Rojo RP, Maravi Loyola J, Hermoza-Gutiérrez M, Cántaro-Segura H, Fernández-Huaytalla E, Gutiérrez-Reynoso DL, Quispe-Jacobo F, Ccapa-Ramirez K. Linking Grain Mineral Content to Pest and Disease Resistance, Agro-Morphological Traits, and Bioactive Compounds in Peruvian Coffee Germplasm. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoque-Incaluque, Ester, César Cueva-Carhuatanta, Ronald Pio Carrera-Rojo, Jazmín Maravi Loyola, Marián Hermoza-Gutiérrez, Hector Cántaro-Segura, Elizabeth Fernández-Huaytalla, Dina L. Gutiérrez-Reynoso, Fredy Quispe-Jacobo, and Karina Ccapa-Ramirez. 2026. "Linking Grain Mineral Content to Pest and Disease Resistance, Agro-Morphological Traits, and Bioactive Compounds in Peruvian Coffee Germplasm" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010015

APA StyleChoque-Incaluque, E., Cueva-Carhuatanta, C., Carrera-Rojo, R. P., Maravi Loyola, J., Hermoza-Gutiérrez, M., Cántaro-Segura, H., Fernández-Huaytalla, E., Gutiérrez-Reynoso, D. L., Quispe-Jacobo, F., & Ccapa-Ramirez, K. (2026). Linking Grain Mineral Content to Pest and Disease Resistance, Agro-Morphological Traits, and Bioactive Compounds in Peruvian Coffee Germplasm. Horticulturae, 12(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010015