The Influence of Solar Radiation Modulation Using Double-Roof Light Conversion Films on the Pre- and Post-Harvest Fruit Quality of Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Marimbella)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growing Conditions

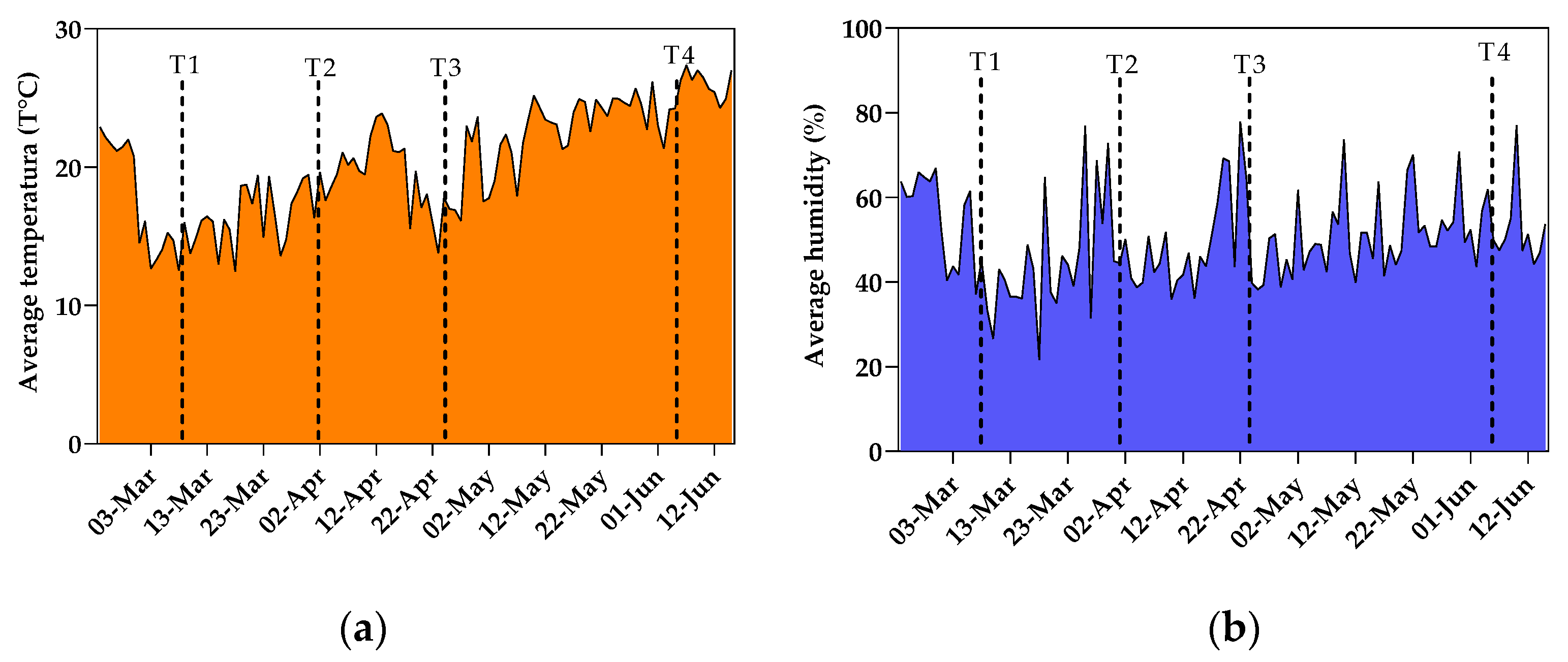

2.2. Greenhouse Parameters, Treatment Identification, and Fruit Biometric Measurements

2.3. Plant Physiological Parameters

2.4. Plant Biometric Parameters

2.5. Fruit Color, Soluble Solid Content and Titratable Acidity

2.6. Extraction for Spectrophotometric Assays: Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity

2.6.1. Total Phenolic Content

2.6.2. Antioxidant Activity Assays

2.7. Total Ascorbic Acid Content

2.8. Total Anthocyanin Content

2.9. Botrytis cinerea Inoculum Preparation and Fruit Inoculation

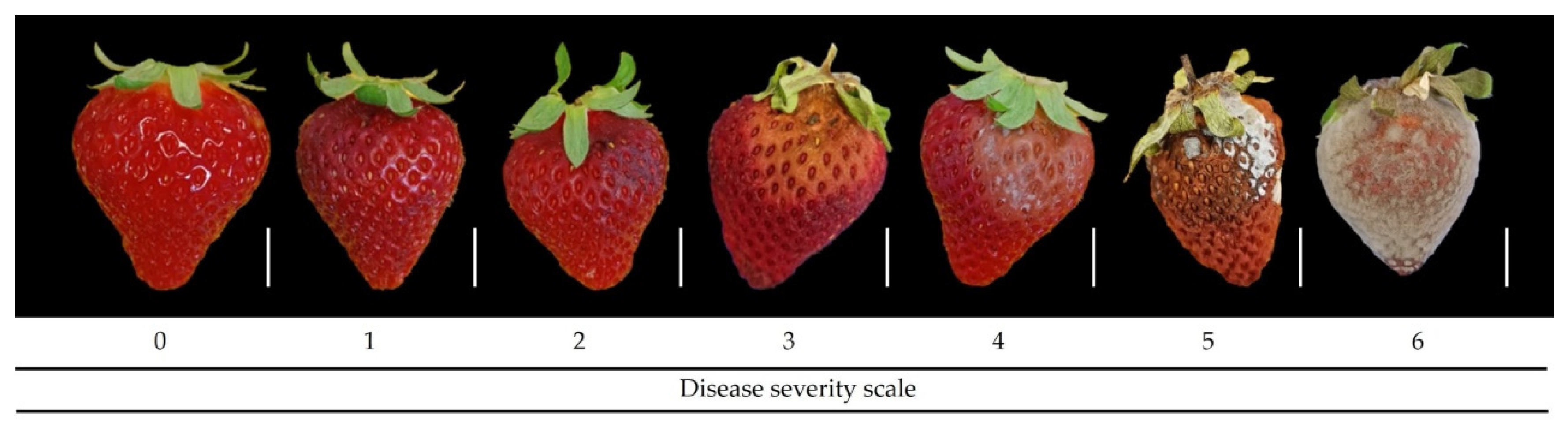

2.10. Post-Harvest Botrytis cinerea Development

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Light-Converting Properties of Polyethene Films

3.2. Plant Morphological Parameters

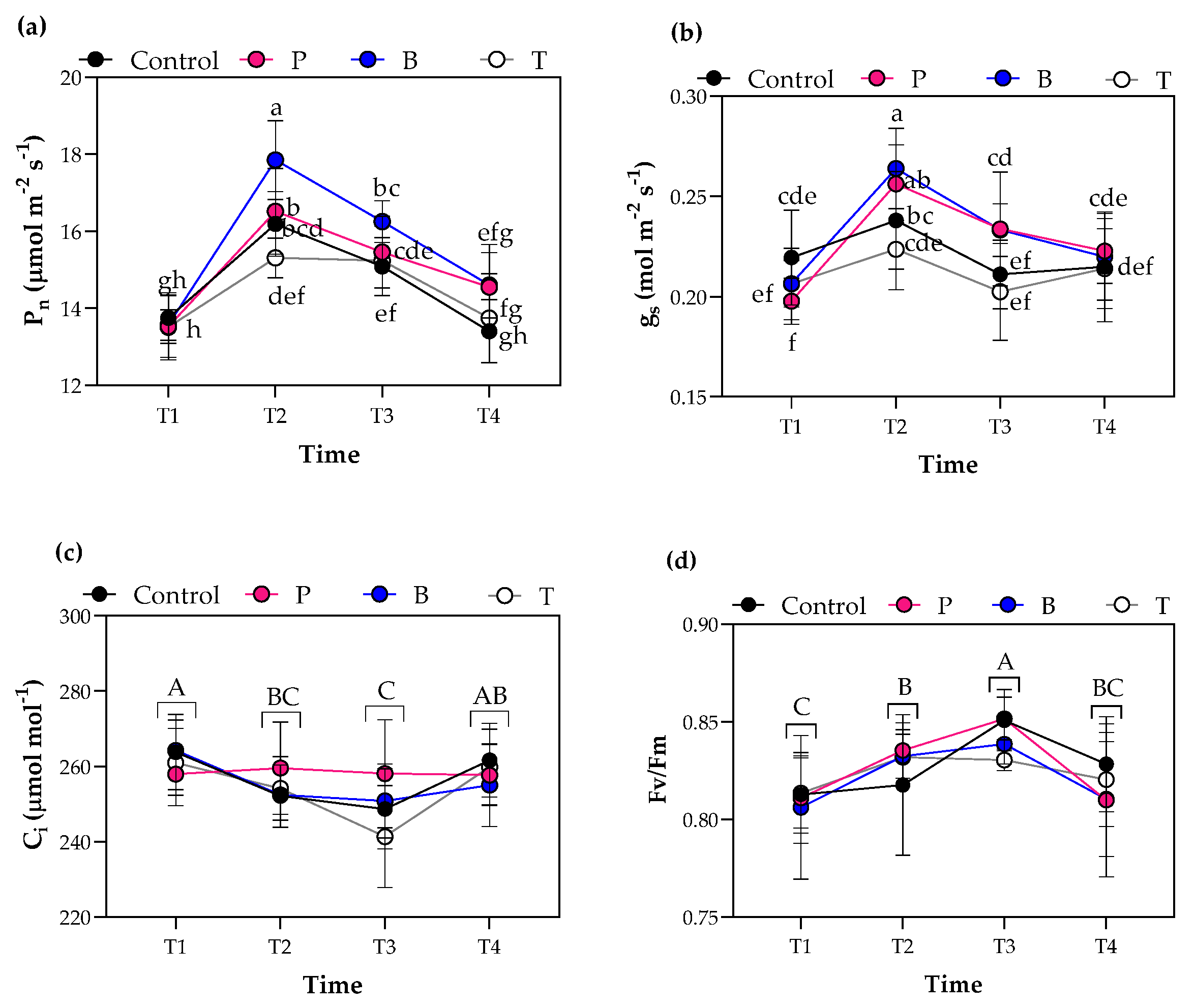

3.3. Plant Physiological Characteristics

3.4. Fruit Yield and Fruit Biometric Parameters

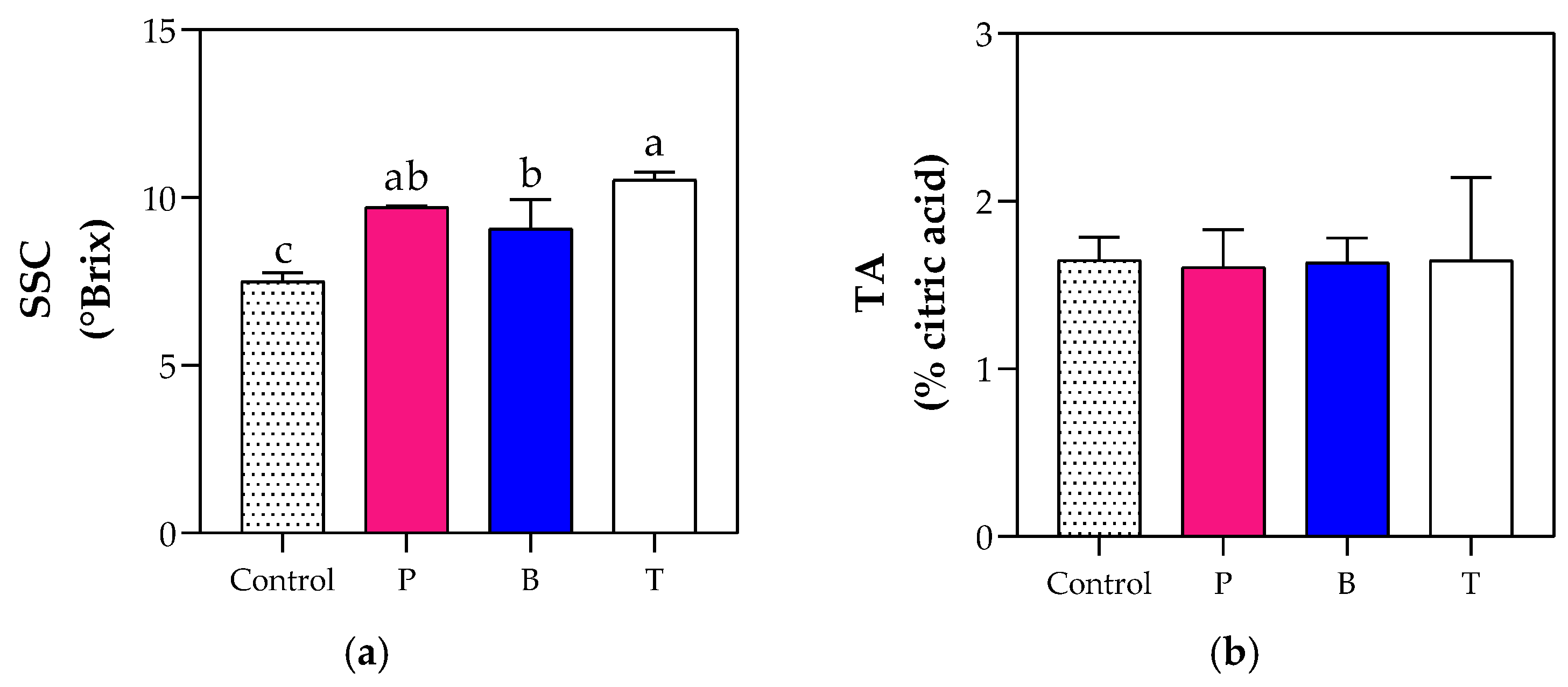

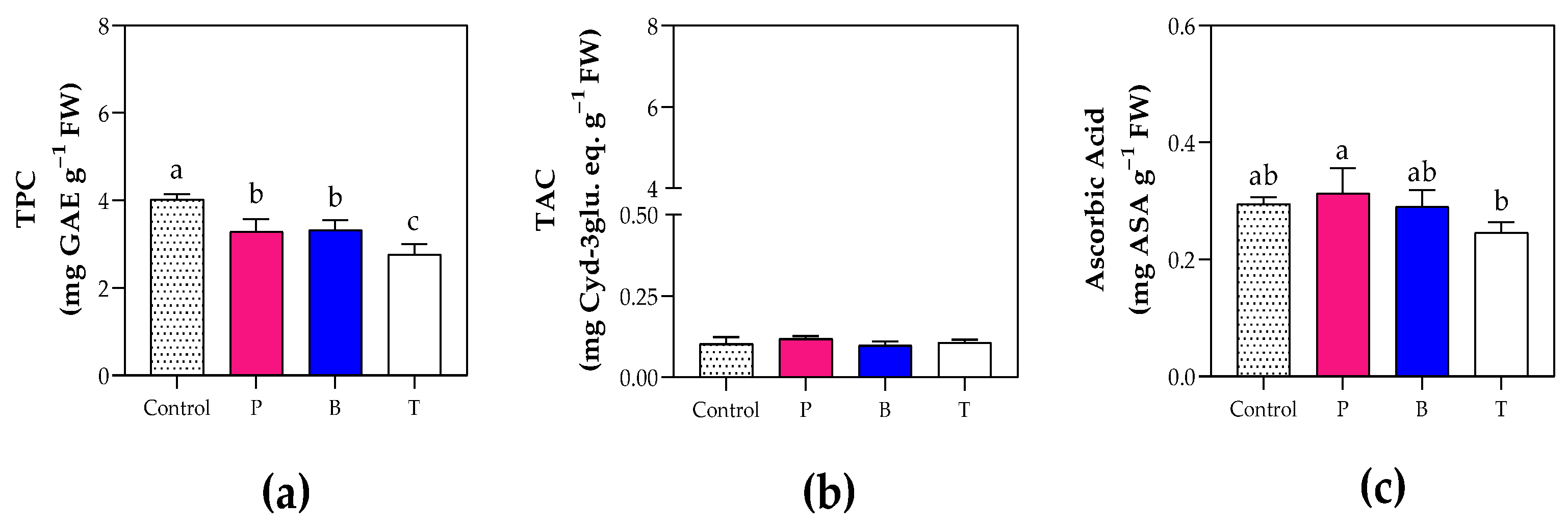

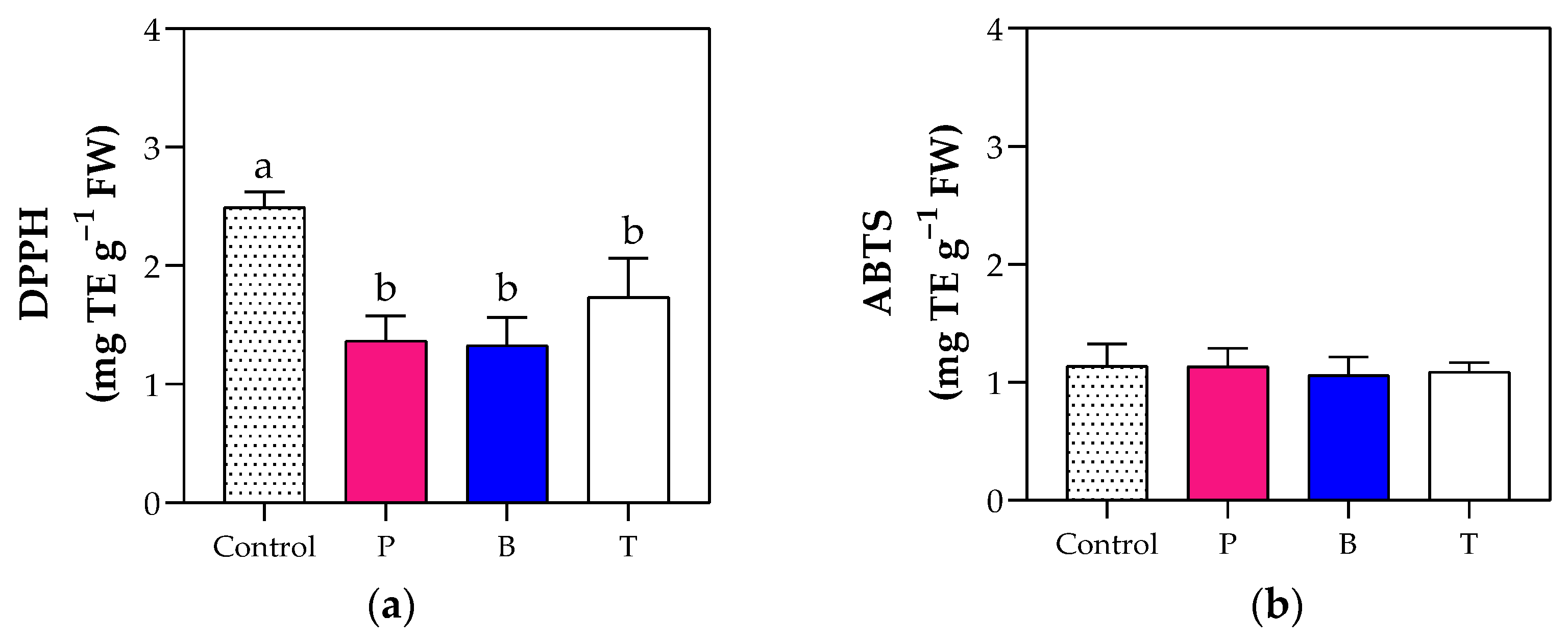

3.5. Fruit Organoleptic and Nutritional Quality

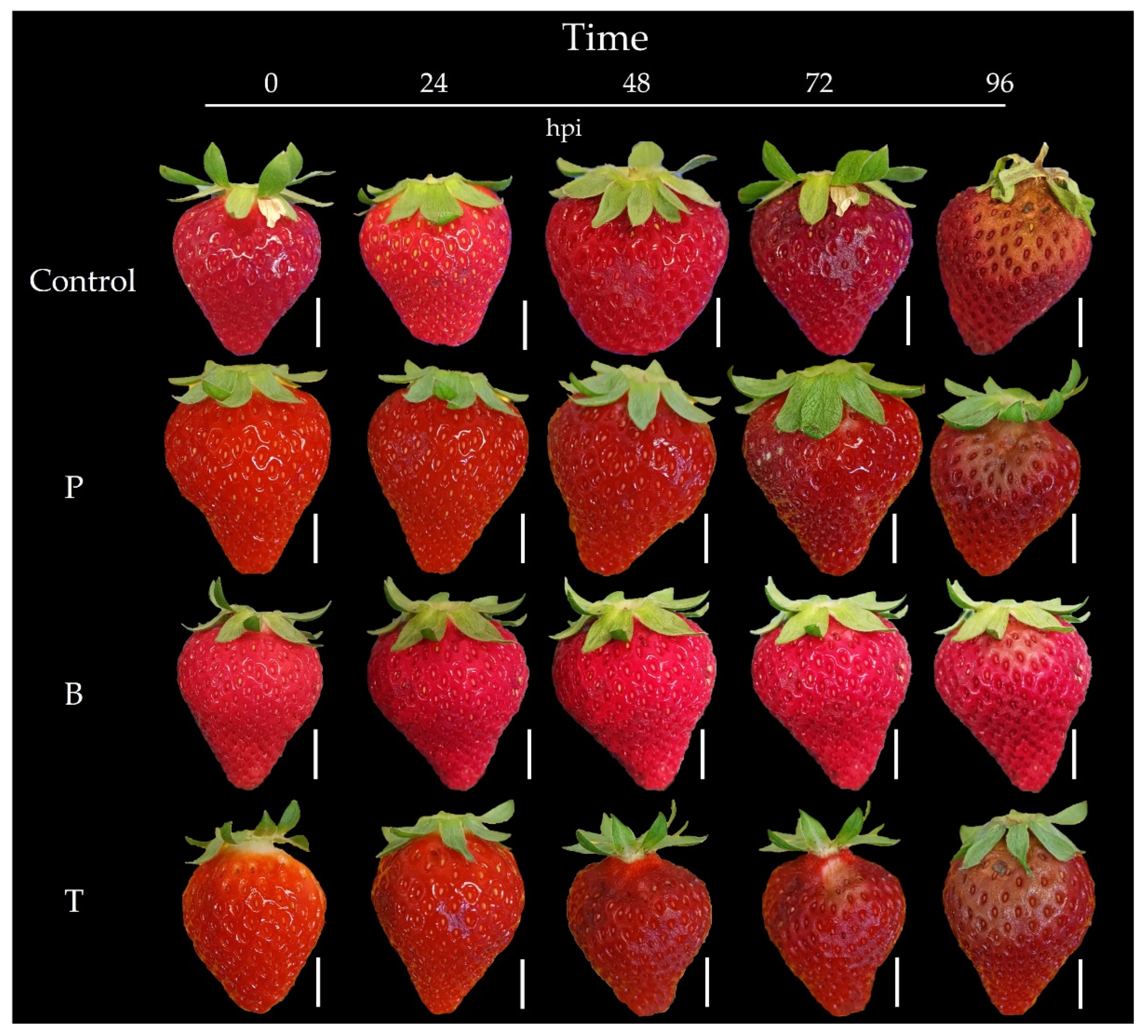

3.6. Botrytis cinerea Development

4. Discussion

4.1. Light-Conversion Technology Applied in Double-Roof System: Effect on Light Spectra

4.2. Blue Film Improved Leaf Gas Exchange, Leaf Number but Decreased Leaf Thickness, Similarly to the Pink Film

4.3. The Blue Film Enhanced Fruit Production and Fruit Organoleptic Quality

4.4. Effect of LC® Films on Botrytis cinerea Development

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Conti, S.; Di Mola, I.; Barták, M.; Cozzolino, E.; Melchionna, G.; Mormile, P.; Ottaiano, L.; Paradiso, R.; Rippa, M.; Testa, A.; et al. Crop Performance and Photochemical Processes Under a UV-to-Red Spectral Shifting Greenhouse: A Study on Aubergine and Strawberry. Agriculture 2025, 15, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.H.; Manzoor, M.A.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Hameed, M.K.; Rehaman, A.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, Q.; Chang, L. Comprehensive Review: Effects of Climate Change and Greenhouse Gases Emission Relevance to Environmental Stress on Horticultural Crops and Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivellini, A.; Toscano, S.; Romano, D.; Ferrante, A. The Role of Blue and Red Light in the Orchestration of Secondary Metabolites, Nutrient Transport and Plant Quality. Plants 2023, 12, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somkuwar, R.G.; Dhole, A.M. Understanding the Photosynthesis in Relation to Climate Change in Grapevines. Theory Biosci. 2025, 144, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, S.; Khan, N.; Perveen, S.; Qu, M.; Jiang, J.; Govindjee; Zhu, X. Changes in the Photosynthesis Properties and Photoprotection Capacity in Rice (Oryza sativa) Grown under Red, Blue, or White Light. Photosynth. Res. 2019, 139, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Horri, H.; Vitiello, M.; Ceccanti, C.; Lo Piccolo, E.; Lauria, G.; De Leo, M.; Braca, A.; Incrocci, L.; Guidi, L.; Massai, R.; et al. Ultraviolet-to-Blue Light Conversion Film Affects Both Leaf Photosynthetic Traits and Fruit Bioactive Compound Accumulation in Fragaria × ananassa. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huché-Thélier, L.; Crespel, L.; Gourrierec, J.L.; Morel, P.; Sakr, S.; Leduc, N. Light Signaling and Plant Responses to Blue and UV Radiations—Perspectives for Applications in Horticulture. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 121, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, G.; Lo Piccolo, E.; Ceccanti, C.; Guidi, L.; Bernardi, R.; Araniti, F.; Cotrozzi, L.; Pellegrini, E.; Moriconi, M.; Giordani, T.; et al. Supplemental Red LED Light Promotes Plant Productivity, “Photomodulates” Fruit Quality and Increases Botrytis cinerea Tolerance in Strawberry. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 198, 112253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kook, H.-S.; Jang, Y.-J.; Lee, W.-H.; Kamala-Kannan, S.; Chae, J.-C.; Lee, K.-J. The Effect of Blue-Light-Emitting Diodes on Antioxidant Properties and Resistance to Botrytis cinerea in Tomato. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Sang, Y.; Mei, S.; Xu, C.; Yu, X.; Pan, T.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. The Effects of Storage Temperature, Light Illumination, and Low-Temperature Plasma on Fruit Rot and Change in Quality of Postharvest Gannan Navel Oranges. Foods 2022, 11, 3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Van Iersel, M.W. Photosynthetic Physiology of Blue, Green, and Red Light: Light Intensity Effects and Underlying Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 619987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Rivard, C.; Wang, W.; Pliakoni, E.; Gude, K.; Rajashekar, C.B. Spectral Blocking of Solar Radiation in High Tunnels by Poly Covers: Its Impact on Nutritional Quality Regarding Essential Nutrients and Health-Promoting Phytochemicals in Lettuce and Tomato. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávalos-Sánchez, E.; López-Martínez, A.A.; Molina-Aiz, F.D.; Lemarié, S.; Proost, K.; Peilleron, F.; Moreno-Teruel, M.A.; Valera, D.L. Effect of Photoconversion Films Used as Greenhouse Double Roof on the Development of Cucumber Fungal Diseases in Spain. In Proceedings of the Eurpean Conference on Agricultural Engineering AgEng2021, Évora, Portugal, 4–8 July 2021; Barbosa, J.C., Silva, L.L., Lourenço, P., Sousa, A., Silva, J.R., Cruz, V.F., Baptista, F., Eds.; Universidade de Évora: Évora, Portugal, 2021; pp. 831–838. [Google Scholar]

- Proietti, S.; Moscatello, S.; Riccio, F.; Downey, P.; Battistelli, A. Continuous Lighting Promotes Plant Growth, Light Conversion Efficiency, and Nutritional Quality of Eruca vesicaria (L.) cav. in Controlled Environment with Minor Effects Due to Light Quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 730119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Qiao, X.; Li, B.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Z.; Hao, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Shen, L.; et al. The Research Progress of Rare Earth Agricultural Light Conversion Film. Heliyon 2024, 10, 36967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemarié, S.; Guérin, V.; Jouault, A.; Proost, K.; Cordier, S.; Guignard, G.; Demotes-Mainard, S.; Bertheloot, J.; Sakr, S.; Peilleron, F. Melon and Potato Crops Productivity under a New Generation of Optically Active Greenhouse Films. Acta Hortic. 2020, 1296, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Horri, H.; Vitiello, M.; Braca, A.; De Leo, M.; Guidi, L.; Landi, M.; Lauria, G.; Lo Piccolo, E.; Massai, R.; Remorini, D.; et al. Blue and Red Light Downconversion Film Application Enhances Plant Photosynthetic Performance and Fruit Productivity of Rubus fruticosus L. var. Loch Ness. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Van Labeke, M.-C. Long-Term Effects of Red- and Blue-Light Emitting Diodes on Leaf Anatomy and Photosynthetic Efficiency of Three Ornamental Pot Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Saini, R.; Shukla, P.K.; Tiwari, K.N. Role of Secondary Metabolites in Plant Defense Mechanisms: A Molecular and Biotechnological Insights. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 953–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadomura-Ishikawa, Y.; Miyawaki, K.; Noji, S.; Takahashi, A. Phototropin 2 Is Involved in Blue Light-Induced Anthocyanin Accumulation in Fragaria × ananassa Fruits. J. Plant Res. 2013, 126, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, M.; Zivcak, M.; Sytar, O.; Brestic, M.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Plasticity of Photosynthetic Processes and the Accumulation of Secondary Metabolites in Plants in Response to Monochromatic Light Environments: A Review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Bioenerg. 2020, 1861, 148131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.-H.; Domijan, M.; Klose, C.; Biswas, S.; Ezer, D.; Gao, M.; Khattak, A.K.; Box, M.S.; Charoensawan, V.; Cortijo, S.; et al. Phytochromes Function as Thermosensors in Arabidopsis. Science 2016, 354, 886–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Lu, Y.; Yang, T.; Trouth, F.; Lewers, K.S.; Daughtry, C.S.T.; Cheng, Z.-M. Effect of Genotype and Plastic Film Type on Strawberry Fruit Quality and Post-Harvest Shelf Life. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, 750–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Luo, Z.; Yang, M.; Liang, Z.; Qi, M.; Dong, Y.; Xu, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, L. The Action of RED Light: Specific Elevation of Pelargonidin-Based Anthocyanin through ABA-Related Pathway in Strawberry. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 186, 111835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewanto, V.; Wu, X.; Adom, K.K.; Liu, R.H. Thermal Processing Enhances the Nutritional Value of Tomatoes by Increasing Total Antioxidant Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3010–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampfenkel, K.; Vanmontagu, M.; Inze, D. Extraction and Determination of Ascorbate and Dehydroascorbate from Plant Tissue. Anal. Biochem. 1995, 225, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E. Characterization and Measurement of Anthocyanins by UV-Visible Spectroscopy. In Current Protocols in Food Analytical Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. F1.2.1–F1.2.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesti, M.; Marchica, A.; Pisuttu, C.; Risoli, S.; Pellegrini, E.; Bellincontro, A.; Mencarelli, F.; Tonutti, P.; Nali, C. Ozone-Induced Biochemical and Molecular Changes in Vitis vinifera Leaves and Responses to Botrytis cinerea Infections. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simko, I.; Piepho, H.-P. The Area under the Disease Progress Stairs: Calculation, Advantage, and Application. Phytopathology 2012, 102, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, A.; Cheng, Z.-M. (Max) Effects of Light Emitting Diode Lights on Plant Growth, Development and Traits a Meta-Analysis. Hortic. Plant J. 2021, 7, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, R.; Wu, B.-S.; MacPherson, S.; Lefsrud, M. A Review of Strawberry Photobiology and Fruit Flavonoids in Controlled Environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 611893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doupis, G.; Bosabalidis, A.M.; Patakas, A. Comparative Effects of Water Deficit and Enhanced UV-B Radiation on Photosynthetic Capacity and Leaf Anatomy Traits of Two Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Cultivars. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2016, 28, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiamba, H.D.S.S.; Zhang, X.; Sierka, E.; Lin, K.; Ali, M.M.; Ali, W.M.; Lamlom, S.F.; Kalaji, H.M.; Telesiński, A.; Yousef, A.F.; et al. Enhancement of Photosynthesis Efficiency and Yield of Strawberry (Fragaria ananassa Duch.) Plants via LED Systems. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 918038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Wu, Q.; Shen, Z.; Xia, K.; Cui, J. Effects of Light Quality on the Chloroplastic Ultrastructure and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Cucumber Seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 73, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, G.; Piccolo, E.L.; Davini, A.; Castiglione, M.R.; Pieracci, Y.; Flamini, G.; Martens, S.; Angeli, A.; Ceccanti, C.; Guidi, L.; et al. Modulation of VOC Fingerprint and Alteration of Physiological Responses after Supplemental LED Light in Green- and Red-Leafed Sweet Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). Sci. Hortic. 2023, 315, 111970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadalini, S.; Zucchi, P.; Andreotti, C. Effects of Blue and Red LED Lights on Soilless Cultivated Strawberry Growth Performances and Fruit Quality. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2017, 82, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.Y.; Kadowaki, M.; Che, J.; Horiuchi, N.; Ogiwara, I. Plant Morphological Characteristics for Year-Round Production and Its Fruit Quality in Response to Different Light Wavelengths in Blueberry. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1206, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Ni, B.; Zuo, Z. Effects of Different Colored Light-Quality Selective Plastic Films on Growth, Photosynthetic Abilities, and Fruit Qualities of Strawberry. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2020, 38, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanwoua, J.; Vercambre, G.; Buck-Sorlin, G.; Dieleman, J.A.; De Visser, P.; Génard, M. Supplemental LED Lighting Affects the Dynamics of Tomato Fruit Growth and Composition. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xin, G.; Wei, M.; Shi, Q.; Yang, F.; Wang, X. Carbohydrate Accumulation and Sucrose Metabolism Responses in Tomato Seedling Leaves When Subjected to Different Light Qualities. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.G.; Moon, B.Y.; Kang, N.J. Effects of LED Light on the Production of Strawberry during Cultivation in a Plastic Greenhouse and in a Growth Chamber. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 189, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Mestdagh, H.; Ameye, M.; Audenaert, K.; Höfte, M.; Van Labeke, M.-C. Phenotypic Variation of Botrytis cinerea Isolates Is Influenced by Spectral Light Quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Yuan, M.; Li, H.; Guo, S.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Hawara, E.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; et al. The Blue-Light Receptor CRY1 Serves as a Switch to Balance Photosynthesis and Plant Defense. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerón-Bustamante, M.; Balducci, E.; Beccari, G.; Nicholson, P.; Covarelli, L.; Benincasa, P. Effect of Light Spectra on Cereal Fungal Pathogens, a Review. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2023, 43, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| λ | Treatment | Average Percentage of Transmitted Light Spectrum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T | ||

| UV (300–380 nm) | B | −48.0% | −30.8% |

| P | −59.6% | −44.7% | |

| BLUE (450–495 nm) | B | −6.1% | +17.2% |

| P | −19.8% | +1.1% | |

| GREEN (510–575 nm) | B | −8.5% | +20.0% |

| P | −24.0% | −6.9% | |

| RED (620–700 nm) | B | −8.6% | +13.9% |

| P | −12.8% | +8.3% | |

| Variable | Control | P | B | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf Area (cm2) | 73.8 ± 3.01 | 73.1 ± 7.95 | 64.8 ± 2.77 | 72.8 ± 4.60 |

| Leaf thickness (mm) | 0.5 ± 0.01 a | 0.4 ± 0.03 b | 0.4 ± 0.01 b | 0.5 ± 0.02 a |

| Leaf number (n° plant−1) | 24.3 ± 8.50 b | 33.3 ± 2.00 ab | 45.0 ± 8.70 a | 31.6 ± 9.40 ab |

| Leaf dry matter (%) | 28.2 ± 0.60 ab | 26.7 ± 0.70 c | 28.9 ± 0.64 a | 27.2 ± 0.60 bc |

| Total plant biomass (g plant−1) | 152.0 ± 59.60 | 169.0 ± 48.10 | 194.0 ± 78.70 | 153.0 ± 58.00 |

| Stem biomass (g plant−1) | 103.0 ± 34.30 | 125.0 ± 42.20 | 113.0 ± 35.80 | 118.0 ± 43.50 |

| Root biomass (g plant−1) | 49.0 ± 29.00 b | 44.0 ± 13.80 b | 81.0 ± 44.50 a | 35.0 ± 15.80 b |

| Control | P | B | T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single fruit weight (g) | 28.0 ± 0.81 a | 27.5 ± 0.50 a | 20.2 ± 0.82 c | 23.4 ± 0.63 b |

| Fruit width (mm) | 37.1 ± 0.71 a | 34.5 ± 1.20 b | 32.4 ± 0.85 c | 34.8 ± 1.11 b |

| Fruit height (mm) | 47.6 ± 0.56 a | 43.4 ± 0.10 bc | 42.5 ± 0.42 c | 44.3 ± 1.05 b |

| Fruit yield (g plant−1) | 202.1 ± 59.38 b | 232.9 ± 73.41 ab | 270.3 ± 59.67 a | 188.3 ± 55.79 b |

| Control | P | B | T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | 33.67 ± 1.30 ab | 34.88 ± 2.64 ab | 32.21 ± 3.78 b | 35.64 ± 1.43° |

| a* | 34.51 ± 1.53 b | 38.41 ± 1.66 a | 34.54 ± 1.70 b | 38.44 ± 1.94° |

| b* | 19.78 ± 3.13 b | 24.03 ± 2.71 a | 20.99 ± 3.69 ab | 23.45 ± 1.17 ab |

| Post Inoculation Time (h) | 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 16 ± 4 ghi | 32 ± 5.29 efg | 45 ± 1.73 b–e | 54 ± 6 abc |

| P | 14 ± 4 hi | 24 ± 0 fgh | 38 ± 2 c–f | 58 ± 2 ab |

| B | 14 ± 5.29 hi | 24 ± 3.46 fgh | 34 ± 4 def | 50 ± 5.29 bcd |

| T | 12 ± 0 hi | 32 ± 2 efg | 54 ± 3.46 abc | 70 ± 2 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El Horri, H.; Bianchi, G.; Florio, M.; Malfanti, A.; Ceccanti, C.; Lo Piccolo, E.; Risoli, S.; Nali, C.; Landi, M.; Guidi, L. The Influence of Solar Radiation Modulation Using Double-Roof Light Conversion Films on the Pre- and Post-Harvest Fruit Quality of Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Marimbella). Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11091121

El Horri H, Bianchi G, Florio M, Malfanti A, Ceccanti C, Lo Piccolo E, Risoli S, Nali C, Landi M, Guidi L. The Influence of Solar Radiation Modulation Using Double-Roof Light Conversion Films on the Pre- and Post-Harvest Fruit Quality of Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Marimbella). Horticulturae. 2025; 11(9):1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11091121

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Horri, Hafsa, Gemma Bianchi, Marta Florio, Alessio Malfanti, Costanza Ceccanti, Ermes Lo Piccolo, Samuele Risoli, Cristina Nali, Marco Landi, and Lucia Guidi. 2025. "The Influence of Solar Radiation Modulation Using Double-Roof Light Conversion Films on the Pre- and Post-Harvest Fruit Quality of Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Marimbella)" Horticulturae 11, no. 9: 1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11091121

APA StyleEl Horri, H., Bianchi, G., Florio, M., Malfanti, A., Ceccanti, C., Lo Piccolo, E., Risoli, S., Nali, C., Landi, M., & Guidi, L. (2025). The Influence of Solar Radiation Modulation Using Double-Roof Light Conversion Films on the Pre- and Post-Harvest Fruit Quality of Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Marimbella). Horticulturae, 11(9), 1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11091121