Abstract

This study investigates millerandage, a physiological disorder affecting grapes during their development. In the climate change context, millerandage can become a viticultural hazard problem causing yield drops and posing challenges regarding wine quality due to uneven ripening in grape clusters. Using the 2023 vintage data from the Research Station for Viticulture and Enology Blaj (SCDVV Blaj), Târnave wine region, Romania, we assessed the climate conditions of 2023, focusing on the adverse climatic conditions from the flowering phenophase and the observed millerandage grade that occurred as a consequence. A total of 26 grapevine cultivars were monitored, assessing millerandage grade by field observations carried out in two grapevine plantations (S1 and S2) in July (BBCH 79) and September (BBCH 87). The results show statistically significant differences, with cultivars like Ezerfurtu (Ez), Napoca (Na), and Rhin Riesling (RR) exhibiting a millerandage grade higher than 35%, while cultivars like Pinot noir (PN) and Pinot gris (PG) showed resilience, with millerandage grades below 1%. These findings highlight cultivar-specific vulnerabilities and provides insights into millerandage’s role as a climate change challenge in viticulture.

1. Introduction

Grapevine is considered a highly sensitive indicator plant for climate change due to its strong dependence on climatic conditions for growth, development, and fruit quality [1,2,3,4]. The impact of climate change on grapevines has been extensively studied in various wine regions around the world [1].

Temperature, precipitations, humidity, sunlight, and wind are the main climate factors playing a crucial role in determining the quality and quantity of grape production [2]. Long-term climate records show rising land and ocean temperatures together with shifting patterns in rainfall and extreme weather events [5]. Since 1850, Earth’s temperature has increased (on average) by 0.06 °C per decade. The rate of warming since 1982 is more than three times as fast: 0.20 °C per decade, with 2023 being the warmest year since global records began in 1850. It registered 1.18 °C more than the 20th century average (13.9 °C) and was 1.35 °C above the pre-industrial average (1850–1900). All that extra heat is driving regional and seasonal temperature extremes, reducing snow cover and sea ice, intensifying heavy rainfall, and changing habitat ranges for plants and animals, expanding some and shrinking others [6]. High temperatures can cause rapid water loss from grapes, leading to cracking, while cold temperatures can stress the vines, making them more vulnerable to diseases [7,8]. High levels of humidity can promote fungal diseases, while low humidity levels can lead to dehydration and cracking of the fruit [7,9].

Apart from long-term climate change, short-term climate variability is also influencing grapevine growth, development, yield, and grape quality [2,10]. Adverse weather events at key stages of the grapevine development can disrupt the process of grape development, resulting in altered berry and must composition, reduced desirable wine characteristics, and potential market value depreciation [11].

Various phenomena have been observed lately that are attributed to short-term climate variability in many regions of the world [1]. Millerandage, a peculiar condition that affects grape clusters during their development, is one such phenomenon, and it refers to the uneven size and ripening of the berries within a single cluster. While a small percentage of millerandage is considered normal, higher millerandage grades indicate the development of a physiological disorder. Under peculiar conditions, millerandage has the potential of becoming a viticultural hazard, causing serious yield drops and a negative impact on wine quality.

Bruni (1970) described four disorders related to the millerandage phenomenon, and he defines them as follows: (1) coulure = the fall of the flowers before fertilization or before fruit set, (2) millerandage = the arrest of achene development after fruit set so that the grapes remain extremely small and green (2–3 mm), (3) sweet millerandage = the unusually early maturation of very small seedless grapes, and (4) green millerandage = the occurrence of small grapes that remain green and immature even when the rest of the bunch has ripened [12]. Each of the four disorders have different causes and different effects on wines.

Zinelabidine et al. (2021) studied genetic factors associated with millerandage and linked certain gene expressions to fruit set inconsistencies, influencing berry development stages [13]. Barbagallo et al. (2018) highlighted environmental stressors as major contributors to millerandage and found that temperature fluctuations during flowering caused physiological irregularities in pollination and fertilization, leading to an increased millerandage in susceptible grape varieties [14]. Williams et al. (2005) noted that deficiency in specific nutrients (especially iron, boron, and molybdenum) could exacerbate millerandage, leading to a higher proportion of green, underdeveloped berries [15]. Ortoleva (2020) analyzed green millerandage in Grillo grapes, noting that excessive green berries negatively affected wine flavor profiles due to retained “green” compounds in underdeveloped berries [16]. Cahurel (1999) found that grapes affected by sweet millerandage had higher sugar and anthocyanin contents, similar pH, and slightly lower total acidity [17]. According to Spellman (1999), millerandage leads to reduced grape yields due to smaller berry size, producing less juice, which is economically disadvantageous for growers [18]. Jackson and Lombard (1993) highlight that smaller berries resulting from millerandage increase the skin-to-juice ratio, intensifying tannins, flavors, and color compounds in wine, which are often desirable in high-quality red wines [19]. The uneven ripening of berries within a single cluster due to millerandage complicates harvest timing, as growers must balance between overripe and underripe berries, affecting overall wine balance [16]. All of these studies collectively demonstrate that millerandage introduces complexities in grape and wine production, necessitating careful vineyard management for quality optimization.

Because it occurs only in peculiar certain conditions, millerandage is not sufficiently researched and documented. To our knowledge, to date, there are no scientific studies documenting this phenomenon in Romania. This communication reports the millerandage incidence at the Research Station for Viticulture and Enology Blaj (SCDVV Blaj), Târnave wine region, Romania, under 2023 climatic conditions and examines cultivar susceptibility considering their location and the date of observation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Cultivars

For this study, we assessed the frequency and intensity of millerandage by field observations carried out on two grapevine plantations (S1 and S2, Figure 1) belonging to SCDVV Blaj, located in Crăciunelu de Jos, Alba County, Romania, which are a part of the prestigious Târnave wine region.

Figure 1.

The location of the two studied grapevine plantations.

The training system used was the demi-high Guyot system with periodic replacement arms, and other details regarding the studied grapevine plantations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details regarding the studied grapevine plantations.

A total of 26 grapevine cultivars, Fetească regală (FR), Someșan (So), Pinot noir (PN), Blasius (Bs) Pinot gris (PG), Traminer roz (TR), Rhin Riesling (RR), Ezerfurtu (Ez), Iordana (Io), Argesis (Ar), Napoca (Na), Astra (As), Selena (Se), Fetească neagră (FN), Muscat Ottonel (MO), Italian Riesling (RI), Brumăriu (Br), Fetească albă (FA), Radames (Ra), Furmint (Fu), Neuburger (Nb), Transilvania (Tv), Timpuriu de Cluj (TiC), Regent (Rg), Amurg (Am), and Sauvignon blanc (SG), all belonging to Vitis vinifera sp., were monitored in July (BBCH 79) and also in September (BBCH 87).

2.2. Climate Monitorization

Weather data were recorded daily by an iMetos 3.3 weather station (Pessl Instruments GmbH; Weiz, Austria) located on the premises of the studied grapevine plantations at the following coordinates: 46.172785° N and 23.933833° E.

Monthly climatic parameters such as monthly average temperature, absolute maximum temperature, absolute minimum temperature, heat units during the vegetation period, precipitation amount, relative humidity levels, and sunlight hours were monitored. The climatic characterization of the year 2023 was assessed in comparison with the refence period of 1990–2022, and special attention was paid to the climatic characterization of the pre-flowering (BBCH 51-57) and flowering phenophases (BBCH 65-69).

2.3. Phenophase Monitoring

The BBCH scale was used for the monitorization of the grapevine developmental stages [20]. The main monitored stages/phenophases were the beginning of bud swelling (BBCH 01), bud development (BBCH 05-09), leaf development (BBCH 10-15), inflorescence emergence (BBCH 51-57), flowering (BBCH 65), fruit development (BBCH 71-77), veraison (BBCH 81-85), harvest (BBCH 89), and senescence (BBCH 91 and BBCH 93-97).

Special attention was paid to the meteorological conditions from BBCH 51 (visible inflorescences) throughout BBCH 69 (end of flowering), and the millerandage was assessed before and after veraison at BBCH 79 and BBCH 87.

2.4. Millerandage Assessment

Taking into account the description provided by Bruni (1970) at SCDVV Blaj in 2023, the 2nd at the 4th forms of millerandage were manifested, and we treated both of them as one disorder—green millerandage, with the grapes remaining small, green, and immature even when the rest of the cluster had ripened.

For each sample, 10 grapes in 5 repetitions (n = 5) were observed visually, assessing the percentage of abnormal berries within the cluster. Based on the observed intensity (I) and frequency (F), the millerandage grade (MillGRD) was calculated as follows:

where

F = the frequency of the phenomenon = the relative value of the number of affected clusters compared to the total number of clusters observed [%];

I = the intensity of the phenomenon = estimated percentage of abnormal fruits per cluster [%].

The equation used to evaluate the millerandage grade was adapted from the EPPO (European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization) norms [21] and the Romanian guide for the diagnosis of plant diseases [22].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses (n = 5) were performed using an in-house program developed on the MATLAB platform 24.1.0.2628055 CWL (MathWorks Inc., Natick, Apple Hill Campus. 1 Apple Hill Drive Natick, Massachusetts,, USA). The three-factor data were subjected to univariate statistical analysis: three-way ANOVA (p = 0.05) and a post-hoc Fisher test (p = 0.05) for pairwise multiple comparisons of sample means. The single-factor data were subjected to a multivariate sequence with the aim of sample clustering. The multivariate sequence consisted of PCA (principal component analysis) and MANOVA (p = 0.05) (multivariate ANOVA). Due to the fact that the MANOVA test generated statistical significance p-values, the sample clustering was validated at the statistical significance threshold of p = 0.05, or 95% accuracy.

3. Results

3.1. Climatic Characterization of the Year 2023

At SCDVV Blaj, the year 2023 was a warm one. All of the average monthly temperatures were positive, even the winter ones. The registered average temperature for the whole year was 11.6 °C, higher than the one registered during the reference period (1990–2022) by 1.2 °C. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Climatic parameters registered in the studied grapevine plantations of SCDVV Blaj.

The absolute maximum temperature of 36.5 °C was registered in August 2023, and it was 5.1 °C lower than the maximum of 41.6 °C registered by the multiannual reference period (Table 2). The absolute minimum temperature of –14.8 °C was registered in February, and it was 9.9 °C higher than the multiannual reference minimum temperature (Table 2). In fact, along the studied year in every month, the maximum temperatures were lower and the minimum temperatures were higher than those in the reference period (Table 2).

During the vegetation period, higher levels of global, active, and useful heat units were accumulated in 2023 than during the average multiannual heat units registered in 1990–2022 (Table 2).

Regarding the precipitation regime, a deficit of 72.3 mm/m2 was registered in 2023, with the precipitation amount totaling 547.6 mm/m2, of which 385.2 mm/m2 were registered during the vegetation period (Table 2). The highest amount of precipitation was recorded in April and June, when most of the days were rainy days. Out of the 30 days of the month, in April, 19 days were rainy ones, with 4 of them registering heavy rains, and in June, 21 days were rainy days, with 5 days registering heavy rains (Table 2). The relative humidity levels were also lower in the studied year compared to the multiannual relative humidity levels. On average, 77.5% relative humidity was recorded in 2023, with lower levels being recorded in March and May (Table 2).

Along the year 2023, a total of 2155 sunlight hours were available for grapevines at SCDVV Blaj, with 1577.5 of them being recorded during the active vegetation period. Compared to the reference period of 1990–2022, we observed higher levels of sunlight exposure. Precisely 177 more hours of sunlight were recorded in 2023 than in the reference period (Table 2).

Iliescu et al. (2019) and Zaldea et al. (2022) report similar findings regarding climate change in the same area [23,24]. Most of these changes are reported in the literature worldwide and are described by different authors as long-term climate change [25,26,27].

3.2. Climatic Characterization of the Pre-Flowering and Flowering Phenophases

Under the above-described climatic conditions, the 2023 grapevine active vegetation period at SCDVV Blaj started on April 13th and ended on October 17th, totaling 187 days. The unfolding of the phenophases is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The grapevine phenophases at SCDVV Blaj in 2023.

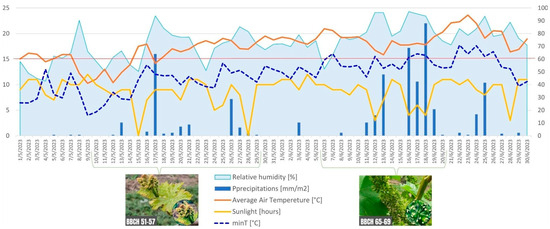

The pre-flowering phenophase, BBCH 51-57, was recorded at the end of May, while the flowering phenophase, BBCH 65-69, was recorded in June. The meteorological peculiarities from the two months of May and June, corresponding to the flower development phenophases, are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the climatic conditions from the grapevine pre-flowering (BBCH 51-57) and flowering phenophases (BBCH 65-69) at SCDVV Blaj in 2023.

Minimum temperatures below the inferior threshold required for flowering can be observed (under 15–17 °C), and average temperatures were between 15 °C and 20 °C, which are under the optimum of 20–25 °C [28]. A significant amount of precipitation was recorded during this time, with heavy rains being registered towards the end of flowering from 16 to 19 June (55 mm). Higher levels of relative humidity (>80%) and lower levels of sunlight can also be observed: 157 h of sunlight were recorded during the pre-flowering period (BBCH 51-57), and 121 h of sunlight were registered during the flowering phenophase (BBCH 65-69).

The study by González-Fernández et al. (2020) states that the ideal meteorological conditions for pollination are temperatures of around 20 °C with dry weather and a slight wind [29]. Temperatures of 15 °C or lower with rain lead to a decrease in fertilization efficacy [30]. Low temperatures and rainfall events during flowering drastically reduce the atmospheric pollen concentration due to atmospheric washes, having a detrimental effect on fruit set [29].

3.3. Millerandage Grade

The abnormal development of the berries was visible in the fruit development phenophase, after BBCH 75, when significant differences in the size of the berries were observed. Aspects regarding the field observations are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Millerandage observed in the grapevine plantations of SCDVV Blaj.

All of the studied cultivars presented millerandage. Strong significant differences were observed regarding the intensity and frequency of the phenomenon and also on the calculated millerandage grade (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results regarding the millerandage observed at SCDVV Blaj in 2023.

According to the multivariate statistical analysis, the cultivars can be grouped into three major clusters, generated by the 10.000 value of the dissimilarity distance, which can be dived into eight subclusters, generated by the 2.500 value of the dissimilarity distance (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) The sample clustering with the help of the MANOVA (p = 0.05) p-value matrix. The false coloring has a legend attached as the last column. (b) The dendrogram generated from the MANOVA (p = 0.05). Horizontal red and green lines represent the dissimilarity distance thresholds for sample clustering.

Cluster 1 is characterized by the highest millerandage grades based on increased intensity and frequency of the phenomenon. In this cluster, Ez, Na, and RR were the most affected cultivars, all registering a millerandage grade higher than 35% at 100% frequency, meaning that all of the observed grape clusters presented millerandage and, on average, more than 35% of the berries were abnormally developed (small and green). Ar, So, and FR, the second subcluster of cluster 1, registered millerandage grades greater than 25% (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Cluster 2 is characterized by lower millerandage grades based on decreased intensity levels (<20%) with a higher frequency (>60%) of the phenomenon. Within cluster 2, subcluster 3—As, Io, Bs, and Rg cultivars—registered around a 10% millerandage grade based on the low intensity of the phenomenon at more than 90% frequency, while subcluster 4—Se, FA TiC, and FN cultivars—registered around 15% millerandage grade based on the slightly higher intensity levels (14–17%), with frequencies between 80 and90%. Subcluster 5—Am, Fu, and TR cultivars—is characterized by a low millerandage grade (<5%) based on decreased intensity levels (2.5–5%) at a 65–70% frequency. Subcluster 6—SG and RI cultivars—registered 5–10% millerandage grades based on the 7–13% intensity levels and slightly decreased frequency (62–68%) (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Cluster 3 includes the least affected cultivars, and it is characterized by the lowest millerandage grades (<5%) based on weak intensity levels and frequencies of under 50%. Within cluster 3, subcluster 8—PG and PN cultivars—registered a millerandage grade of under 1% (Table 4 and Figure 4).

In France, Cahurel (1999) reported 34% affected berries on Gamay noir clone 358, and highlighted a partial crop failure resulting in the production of small berries [17]. In Tunisia, Slimane-Harbi et al. (2004) found that in the case of Razzégui millerandage, the pollination was inhibited by the fact that the surface of the mature pollen grain was devoid of pores and germinative furrows [31].

A more recent study regarding some Sicilian cultivars showed a high percentage of flower abscissions and shot because of a low percentage of pollen germination and no adherence of ovules to the ovary wall [14]. In 2020, Ibáñez et. al. conducted a study aimed at characterizing the reproductive performance of 120 cultivars, in which they took into account a millerandage index and found great diversity for most variables. Large differences between cultivars were observed in terms of both values and stability among seasons [32].

The main-effects statistical analysis was conducted on the FA, FN, FR, Nb, and PG cultivars that were observed on both dates and at both locations. The results show that cultivar had the most important impact on millerandage, with substantial influences from date and location (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Graphical representations of the main effects of the cultivar, date, and location factors on millerandage grade (Blue dots represent the mean values for the millerandage grade; black dashed lines shows the trend across factors and red dashed line indicates the overall mean as a reference point).

Significantly higher millerandage grades were observed in July than in September, which means that the compensatory growth of normal berries concealed the abnormal berries within the cluster. This may have a negative impact on the wine quality due to the presence of “green flavors” arising from potentially underripe grapes concealed within the cluster. Jaquinet et. al. observed this as well in the Chasselas cultivar in the La Cote region of the Vaud canton, France, in 1980 [33].

The work of Spellman (1999) explores how microclimate factors influenced by topography and location impact vineyard health, including issues like millerandage [18]. In our study, increased millerandage grades were recorded on the grapevine plantation located on a 6% slope with a southwestern exposure and a clayey sand soil (S2) than on the one located at lower altitude on a flat field with a southern exposure and an alluvial soil (S1).

Fetească cultivars (FR, FN, and FA) were found to be more vulnerable than Nb and PG, with Fetească Regală registering a millerandage grade of more than 20% (Figure 5).

4. Conclusions

Climate change is increasing weather variability, affecting grapevine phenology and fruit set. At SCDVV Blaj vineyards, shifting temperatures and unpredictable rainfall patterns in 2023 led to the occurrences of millerandage, posing new challenges for grape production and quality.

The climatic changes revealed at SCDVV Blaj when comparing the climatic conditions of 2023 to the ones from the reference period (1990–2022) were the following: increase in the annual average temperature, disappearance of negative monthly average temperatures, decrease in the amplitude of minimum and maximum temperatures, higher levels of heat units during the active vegetation period, lower amount of precipitation, lower levels of relative humidity, and more sunlight hours.

Even if the mean values of the main climatic elements recorded at SCDVV Blaj in 2023 were generally favorable for most of the grapevine cultivars, the adverse climatic conditions that occurred during the flowering phenophase (BBCH 65-69) led to the manifestation of millerandage. The climatic peculiarities that we think disrupted pollination, leading to incomplete fertilization of grape flowers and poor fruit set, were minimum temperatures under 15°C, average temperatures under 20 °C, heavy rains totaling 55 mm in the last few days of the flowering phenophase, more than 80% relative humidity, and many cloudy days with low levels of sunlight (121 h of sunlight from 6 to 20 June).

Statistical analysis revealed that cultivar is the factor with the greatest influence on millerandage, followed by the factors of “date” and “location.” Significant differences were found in both the intensity and the frequency of millerandage across the 26 grape cultivars monitored. Some cultivars, like Ezerfurtu (Ez), Napoca (Na), and Rhin Riesling (RR), were more affected than others, like Pinot gris (PG) and Pinot noir (PN). Higher millerandage grades were observed in July than in September, and increased millerandage grades were recorded on the grapevine plantation located on a 6% slope with a southwestern exposure than on the one located at a lower altitude on a flat field with a southern exposure. Millerandage is a complex phenomenon influenced by microclimate factors. The impact of climate change on millerandage can lead to challenges for grape growers and winemakers, affecting grape quality, yield, and ultimately wine production. By understanding the interplay between millerandage and climate change, stakeholders in the grape and wine industry can proactively address these challenges to maintain grape quality and ensure sustainable wine production in the face of a changing climate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.M.; methodology, M.D.M. and M.C.; software, A.C.T. and M.D.M.; validation, V.S.C., M.C. and L.L.T.; resources, H.S.R., M.C., I.S.G. and A.D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.M.; writing—review and editing, V.S.C., M.D.M. and I.S.G.; visualization, A.D.S. and A.C.T.; supervision, M.C. and L.L.T.; project administration, M.C. and M.D.M.; funding acquisition, M.D.M., M.C. and V.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was carried out with the support of the Romanian Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and was financed by Project ADER 6.3.13/2023 and Project ADER 6.3.14/2023.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bernáth, S.; Paulen, O.; Šiška, B.; Kusá, Z.; Tóth, F. Influence of Climate Warming on Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Phenology in Conditions of Central Europe (Slovakia). Plants 2021, 10, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucur, G.M.; Cojocaru, G.A.; Antoce, A.O. The Climate Change Influences and Trends on the Grapevine Growing in Southern Romania: A Long-Term Study. BIO Web Conf. EDP Sci. 2019, 15, 01008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaster, D.; Tomczyk, A.M.; Hildebrandt-Radke, I.; Matulewski, P. Agroclimatic Indicators for Grapevines in the Zielona Góra Wine Region (Poland) in the Era of Advancing Global Warming. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.K.; de Cortázar-Atauri, I.G.; Trought, M.C.T.; Destrac, A.; Agnew, R.; Sturman, A.; van Leeuwen, C. Adaptation to Climate Change by Determining Grapevine Cultivar Differences Using Temperature-Based Phenology Models: This Article Is Published in Cooperation with the XIIIth International Terroir Congress November 17–18 2020, Adelaide, Australia. Guest Editors: Cassandra Collins and Roberta De Bei. OENO One 2020, 54, 955–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, I.; Polychroni, I.; Droulia, F.; Nastos, P.T. The Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Growing Degree Days (GDD) Agroclimatic Index for the Viticulture over the Northern Mediterranean Basin. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. NOAA’s 2023 Annual Climate Report; National Centers for Environmental Information: Asheville, NC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Khadivi-Khub, A. Physiological and Genetic Factors Influencing Fruit Cracking. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2015, 37, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.V.; Davis, R.E. Climate Influences on Grapevine Phenology, Grape Composition, and Wine Production and Quality for Bordeaux, France. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2000, 51, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortiñas-Rodríguez, J.A.; Fernández-González, E.; Fernández-González, M.; Vázquez-Ruiz, R.A.; Aira, M.J. Fungal Diseases in Two North-West Spain Vineyards: Relationship with Meteorological Conditions and Predictive Aerobiological Model. Agronomy 2020, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naulleau, A.; Hossard, L.; Prévot, L.; Gary, C. Grapevine Yield Estimation in a Context of Climate Change: The GraY Model. In Proceedings of the 14th International Terroir congress and the 2nd ClimWine symposium, Bordeaux, France, 3–8 July 2022; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Rogiers, S.Y.; Greer, D.H.; Liu, Y.; Baby, T.; Xiao, Z. Impact of Climate Change on Grape Berry Ripening: An Assessment of Adaptation Strategies for the Australian Vineyard. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1094633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, B. Coulure, Millerandage and Sweet and Green Millerandage in Grape Bunches. Inf. Di Ortoflorofruttic. 1970, 11, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zinelabidine, L.H.; Torres-Pérez, R.; Grimplet, J.; Baroja, E.; Ibáñez, S.; Carbonell-Bejerano, P.; Martínez-Zapater, J.M.; Ibáñez, J.; Tello, J. Genetic Variation and Association Analyses Identify Genes Linked to Fruit Set-Related Traits in Grapevine. Plant Sci. 2021, 306, 110875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagallo, M.G.; Domina, G.; Scafidi, F.; Pisciotta, A. Millerandage and Flower Abscission in ‘Grillo’, ‘Frappato’ and ‘Nero d’Avola’ Grapevines: Some Probable Causes. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1229, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.M.J.; Maier, N.A.; Bartlett, L. Effect of Molybdenum Foliar Sprays on Yield, Berry Size, Seed Formation, and Petiolar Nutrient Composition of “Merlot” Grapevines. J. Plant Nutr. 2005, 27, 1891–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortoleva, S. Effect of Shoot Tipping and Boron Treatment on Vegetative and Productive Behavior of Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Grillo. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cahurel, J.Y. Effect of “Millerandage” on Grape Quality. The Case of Gamay Noir à Jus Blanc. Progrès Agric. et Vitic. 1999, 116, 161–162. [Google Scholar]

- Spellman, G. Wine, Weather and Climate. Weather 1999, 54, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.I.; Lombard, P.B. Environmental and Management Practices Affecting Grape Composition and Wine Quality—A Review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1993, 44, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.; Eichhorn, K.; Bleiholder, H.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Weber, E. Growth Stages of the Grapevine: Phenological Growth Stages of the Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. vinifera)—Codes and Descriptions According to the Extended BBCH Scale. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1995, 1, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization. Guidelines for the Efficacy Evaluation of Plant Protection Products. EPPO Bull. 2001, 31, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severin, V.; Cornea, P.C. Ghid Pentru Diagnoza Bolilor Plantelor (Guidelines for Diagnosis of Plant Diseases), 1st ed.; Ceres: București, Romania, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Iliescu, M.; Tomoiaga, L.; Chedea, V.S.; Sirbu, A. Evaluation of Climate Changes on the Vine Agrosystem in Târnave Vineyard. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2019, 20, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Zaldea, G.; Doina, D.; Liliana, P.; Maria, I.; Viorica, E.; Anamaria, T.; Ionica, B.; Andreea, G. The Evolution of Climatic Conditions between 1989 and 2021 in Representative Vine Areas of Romania. Lucr. Ştiinţifice Ser. Hortic. 2022, 65, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Neethling, E.; Petitjean, T.; Quénol, H.; Barbeau, G. Assessing Local Climate Vulnerability and Winegrowers’ Adaptive Processes in the Context of Climate Change. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2017, 22, 777–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.A.; Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Dinis, L.T.; Correia, C.; Moriondo, M.; Leolini, L.; Dibari, C.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; et al. A Review of the Potential Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Options for European Viticulture. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droulia, F.; Charalampopoulos, I. A Review on the Observed Climate Change in Europe and Its Impacts on Viticulture. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țârdea, C.; Dejeu, L. Viticultură, 1st ed.; Editura Didactică și Pedagogică, R.A.-București: București, Romania, 1995; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- González-Fernández, E.; Piña-Rey, A.; Fernández-González, M.; Aira, M.J.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J. Prediction of Grapevine Yield Based on Reproductive Variables and the Influence of Meteorological Conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebon, G.; Duchêne, E.; Brun, O.; Clément, C. Phenology of Flowering and Starch Accumulation in Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.) Cuttings and Vines. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimane-Harbi, M.B.; Chabbouh, N.; Snoussi, H.; Bessis, R.; El-Gazzah, M. The Study of the Traditional Vine Germplasm of Tunisia. Details on the Origin of “Razzegui” Millerandage. Bull. de l’OIV 2004, 77, 487–501. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, J.; Baroja, E.; Grimplet, J.; Ibáñez, S. Cultivated Grapevine Displays a Great Diversity for Reproductive Performance Variables. Crop Breed. Genet. Genom. 2020, 2, e200003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jaquinet, A.; Domahidy, M.; Aerny, J. Millerandage in Chasselas Grapevine. Quantitative and Qualitative Development during Ripening. Rev. Suisse Vitic. D’arboriculture D’horticulture 1982, 14, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).