Selection of Promising Rhizobia for the Inoculation of Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC. (Fabaceae) in Chromic Eutric Cambisol Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Soil Chemical Analysis

2.3. Isolation and Characterization of Rhizobial Strain

2.4. Effect of Rhizobial Inoculation on Nodulation and Growth of C. ensiformis

2.4.1. Semi-Controlled Conditions

2.4.2. Field Conditions Between Coffee Rows

2.5. Molecular Identification of the Selected Strain

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Putative Rhizobia

3.2. Nodulation Capability

3.3. Effects of Rhizobia on Nodulation and Growth of C. ensiformis

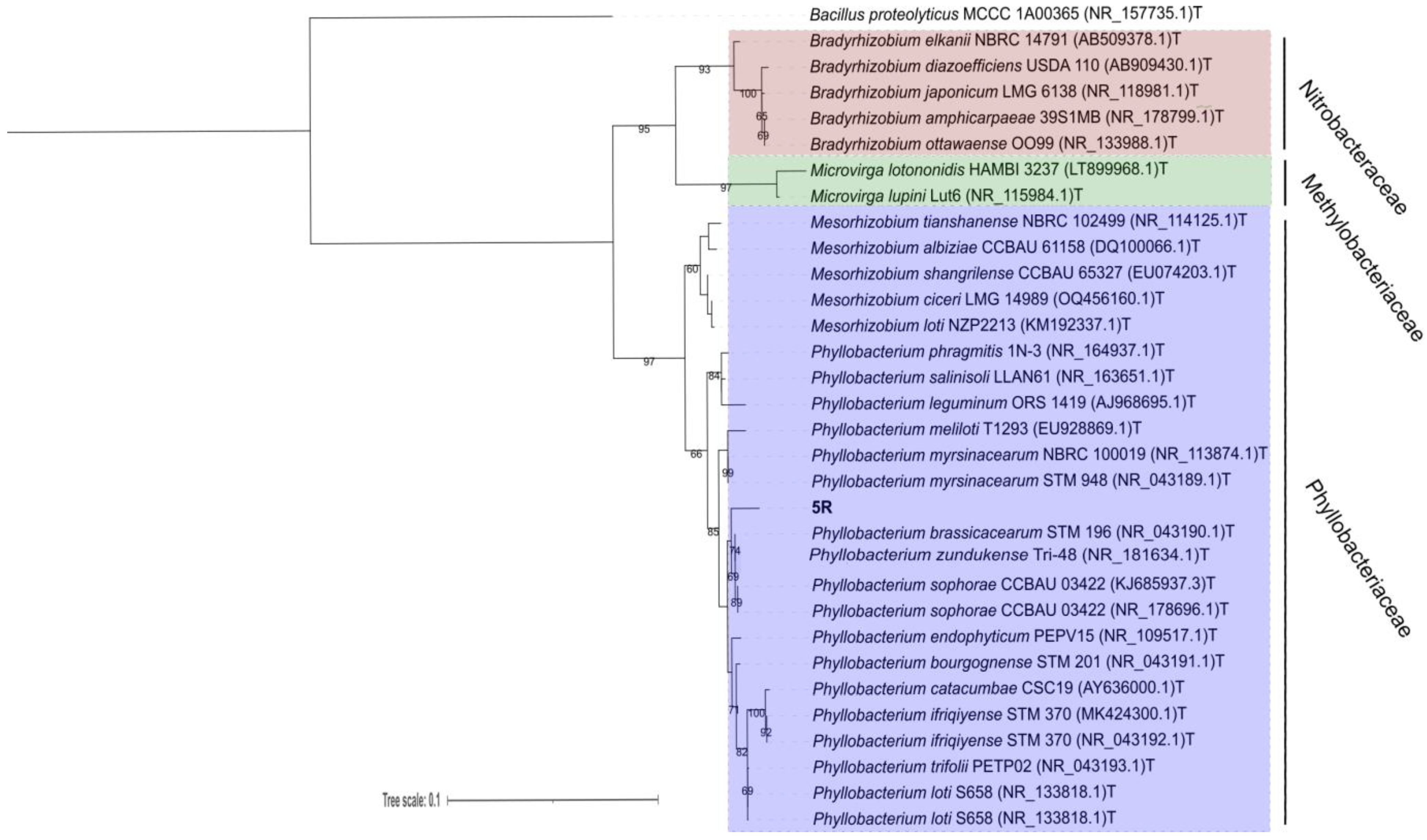

3.4. Identification of Promising Bacterium

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, J.; Si, L.; Zhang, X.; Cao, K.; Wang, J. Various green manure-fertilizer combinations affect the soil microbial community and function in immature red soil. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1255056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, A.; Shang, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, F.; Yin, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chai, Q. Research Progress on the Improvement of Farmland Soil Quality by Green Manure. Agriculture 2025, 15, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, P.A.P.; Del Castillo, L.F. Evaluación de Canavalia ensiformis y Vigna radiata como abonos verdes, sobre la dinámica microbiana del suelo de la finca El Plan de Burras, en el municipio de El Espino, Boyacá, Colombia. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Básicas 2021, 17, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Herridge, D.F.; Peoples, M.B.; Boddey, R.M. Global inputs of biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems. Plant Soil 2008, 311, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E. Nitrogen Fixation in Tropical Cropping Systems; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, Y.T.; Hidalgo, E.C.; Alonso, G.M.M.; Sánchez, C.A.; Martínez, G.M.S.; Hernández, L.R. Selección de cepas eficientes de Rhizobium y micorrizas en Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC. Rev. Mex. Agroecosistemas 2021, 8, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, M.; Pereira, A.; Cabanas, J.; Dias, L.; Pires, J.; Arrobas, M. Crops use-efficiency of nitrogen from manures permitted in organic farming. Eur. J. Agron. 2006, 25, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-González, C.A.; Ferrás-Negrín, Y.; Hernández-Forte, I.; Rivera-Espinosa, R. Benefits of the inoculated canavalia intercropped with mycorrhizal fungi and Rhizobium in Coffea canephora. Agron. Mesoam. 2022, 33, 46288. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, G.M.; Costa Rouws, J.R.; Urquiaga, S.; Rivera, R.A. Crop rotation of Canavalia ensiformis green manure of maize and arbuscular mycorrhize in an eutric rodic nitisol of Cuba. Agron. Trop. 2007, 57, 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vossen, H.; Bertrand, B.; Charrier, A. Next generation variety development for sustainable production of arabica coffee (Coffea arabica L.): A review. Euphytica 2015, 204, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Y.C. Estado actual de la conservación de recursos fitogenéticos de cafeto (Coffea spp.). Cultiv. Trop. 2022, 43, e15. [Google Scholar]

- Lamí, D.S.; Ricabal, P.M.S.; Cosío, E.C. El cultivo del café (Coffea arabica L) y su susceptibilidad a la roya (Hemileia vastatrix Berkeley & Broome) en la provincia Cienfuegos. Rev. Científica Agroecosistemas 2020, 8, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Arboláez, A.O.; Sotero, O.L.C.; Quesada, M.C.H.; Zayas, D.V.; González, L.R.; Ortega, U.C.P. Efecto combinado de cascarilla de arroz carbonizada con fertilizante de liberación controlada en el desarrollo de posturas de Coffea arábica L. Variedad” Isla 6_14”. Temas Agrar. 2023, 28, 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Ronchi, C.P.; Maestri, M.; Barros, R.S. Ecophysiology of coffee growth and production. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 19, 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, E.d.S.; Lima, P.C.d.; Guimarães, G.P.; Moura, W.d.M.; Andrade, F.V. Biological nitrogen fixation by legumes and N uptake by coffee plants. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2017, 41, e0160178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca-Jimenez, A.; Doane, T.A.; Horwath, W.R. Nitrogen use efficiency of coffee at the vegetative stage as influenced by fertilizer application method. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Reference Base for Soil Resources: International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps (WRB, 2022), 4th ed.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3794en/I3794en.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Soto, F.; Vantour, A.; Hernández, A.; Planas, A.; Figueroa, A.; Fuentes, P.; Tejeda, T.; Morales, M.; Vázquez, R.; Zamora, E. Agroecological zoning of Coffea arabica L. in Cuba. “Sagua-Nipe-Baracoa” mountains. Cultiv. Trop. 2001, 3, 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Guianeya, P.; Gómez, G.; Nápoles, M.C.; Morales, B. Aislamiento y caracterización de cepas de rizobios aisladas de diferentes leguminosas en la región de Cascajal, Villa Clara. Pastos Forrajes 2008, 31, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, G.M.; Reyes, R.; Ramírez, J.F. Coinoculation of Canavalia ensiformis with Rhizobium and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in two soils from Cuba. Cultiv. Trop. 2015, 36, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hungria, M.; Vargas, M.A. Environmental factors affecting N2 fixation in grain legumes in the tropics, with an emphasis on Brazil. Field Crops Res. 2000, 65, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thies, J.E.; Singleton, P.W.; Bohlool, B.B. Influence of the size of indigenous rhizobial populations on establishment and symbiotic performance of introduced rhizobia on field-grown legumes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávez, Y.L.P. Rhizobium y hongos formadores de micorrizas: Alternativa biotecnológica en cultivares de caraotas (Phaseolus vulgaris). Rev. Crítica Cienc. 2023, 1, 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Zahran, H.H. Rhizobium-legume symbiosis and nitrogen fixation under severe conditions and in an arid climate. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 968–989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Suárez, M.; Andersen, S.U.; Poole, P.S.; Sánchez-Cañizares, C. Competition, nodule occupancy, and persistence of inoculant strains: Key factors in the rhizobium-legume symbioses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 690567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzada-Rodríguez, L.; González-Fernández, C. Caracterización florística de una finca de la UBPC La Herradura. Café Cacao 2016, 15, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, I.; Estévez, S.L.; Peña, M.D.; Nápoles, M.C. Selection of promising rhizobia to inoculate herbaceous legumes in saline soils. Cuba. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 54, 435–450. [Google Scholar]

- González-Fernández, C.; Ferrás-Negrín, Y.; Meneses-Zamora, I.; Ortiz-Gómez, N. Efecto del humus de lombriz en sustratos para la producción de posturas de cafeto en suelo Ferralítico Lixiviado ácido. Café Cacao 2017, 16, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Howieson, J.; Dilworth, M. Working with Rhizobia; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Canberra: Forrest, Australia, 2016.

- Wang, E.; Martínez Romero, J.; López Lara, I. Rhizobium y su destacada simbiosis con plantas. In Microbiology; Romero, E.M., Romero, J.C.M., Eds.; Centro de Investigaciones sobre Fijación de Nitrógeno, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire, B.; Dlodlo, O.; Chimphango, S.; Stirton, C.; Schrire, B.; Boatwright, S.; Honnay, O.; Smets, E.; Sprent, J.; James, E. Symbiotic diversity, specificity and distribution of rhizobia in native legumes of the Core Cape Subregion (South Africa). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ezura, H.; Nukui, N.; Yuhashi, K.-I.; Minamisawa, K. In vitro plant regeneration in Macroptilium atropurpureum, a legume with a broad symbiont range for nodulation. Plant Sci. 2000, 159, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiiti, E.N. Ecological studies on Macroptilium atropurpureum Urb. in Rwenzori National Park, Uganda. I. Effects of pre-treating seeds with concentrated sulphuric acid, scarification, boiling and burning on germination. Afr. J. Ecol. 1983, 21, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, D.O.; Date, R.A. Legume bacteriology. In Tropical Pasture Research: Principles and Methods; Williams, R.J., Ed.; Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux: Wallingford, UK, 1976; pp. 134–174. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, R.F.; Harter, B.L. Nitrate effects on nodule oxygen permeability and leghemoglobin (nodule oximetry and computer modeling). Plant Physiol. 1995, 107, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Gao, Z.; Li, X.; Liao, H. Excess nitrate induces nodule greening and reduces transcript and protein expression levels of soybean leghaemoglobins. Ann. Bot. 2020, 126, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareque, C.; Taulé, C.; Beracochea, M.; Battistoni, F. Isolation, characterization and plant growth promotion effects of putative bacterial endophytes associated with sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L) Moench). Ann. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Chan, J.; Comeau, D.C.; Connor, R.; DiCuccio, M.; Farrell, C.M.; Feldgarden, M. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D33–D43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alla, M.H.; Nafady, N.A.; Hassan, A.A.; Bashandy, S.R. Isolation and characterization of non-rhizobial bacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi from legumes. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.; Gu, P.; Li, L.; Huang, R. Bacteria from nodules of Abrus mollis Hance: Genetic diversity and screening of highly efficient growth-promoting strains. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1345000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hnini, M.; Aurag, J. Prevalence, diversity and applications potential of nodules endophytic bacteria: A systematic review. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1386742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musiyiwa, K.; Mpepereki, S.; Giller, K. Symbiotic effectiveness and host ranges of indigenous rhizobia nodulating promiscuous soyabean varieties in Zimbabwean soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.A.; Willems, A.; Nesme, X.; De Lajudie, P.; Lindström, K. Revised phylogeny of Rhizobiaceae: Proposal of the delineation of Pararhizobium gen. nov., and 13 new species combinations. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 38, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peix, A.; Ramírez-Bahena, M.H.; Velázquez, E.; Bedmar, E.J. Bacterial associations with legumes. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2015, 34, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.N.; Ardley, J.K. Review of the genus Methylobacterium and closely related organisms: A proposal that some Methylobacterium species be reclassified into a new genus, Methylorubrum gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 2727–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, E.; Wagner, M. Oxidation of inorganic nitrogen compounds as an energy source. In The Prokaryotes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jourand, P.; Giraud, E.; Bena, G.; Sy, A.; Willems, A.; Gillis, M.; Dreyfus, B.; de Lajudie, P. Methylobacterium nodulans sp. nov., for a group of aerobic, facultatively methylotrophic, legume root-nodule-forming and nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 2269–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.S.; Yan, H.; Ji, Z.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Sui, X.H.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, E.T.; Chen, W.X.; Chen, W.F. Phyllobacterium sophorae sp. nov., a symbiotic bacterium isolated from root nodules of Sophora flavescens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngwenya, Z.D.; Dakora, F.D. Symbiotic Functioning and Photosynthetic Rates Induced by Rhizobia Associated with Jack Bean (Canavalia ensiformis L.) Nodulation in Eswatini. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Hinojosa, A.; Mora, C.; Strauss, S.L. Native Rhizobia improve plant growth, fix N2, and reduce greenhouse emissions of sunnhemp more than commercial Rhizobia inoculants in Florida citrus orchards. Plants 2022, 11, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbera-Gorotiza, J.; Nápoles-García, M.C. Evaluación del efecto de rizobios y de un HMA en soya (Glycine max (L.) Merrill). Cultiv. Trop. 2023, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- García, M.O.; Rocafull, Y.R.; Molina, L.Z.; Aguilera, J.L.; Garibay, R.A.; García, M.C.N. Identificación de rizobios promotores del crecimiento vegetal asociados a garbanzo (Cicer arietinum L.). Agron. Mesoam. 2023, 34, 50929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Guo, Y. An integrated method for quantifying root architecture of field-grown maize. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, M.O.; Roiloa, S.; Yu, F.-H. Potential roles of soil microorganisms in regulating the effect of soil nutrient heterogeneity on plant performance. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, H.; Hu, H.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, S. The indirect effect of nitrate on the soybean nodule growth and nitrogen fixation activity in relation to carbon supply. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnalakshmi, K.; Yadav, V.; Tyagi, D.; Dhar, D.W.; Kannepalli, A.; Kumar, S. Significance of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in grain legumes: Growth promotion and crop production. Plants 2020, 9, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentón, G.; Rivera, R.; Martín, G.; Oropeza, K.; Alonso, F. Manejo de Canavalia ensiformis coinoculada con HMA y Rhizobium intercalada en plantaciones de morera (Morus alba L.). Rev. Fac. Agron. (LUZ) 2014, 31, 377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Sunaryo, Y.; Prasetyowati, S.E. Seed nutrient and leaf mineral content of Jack Bean (Canavalia ensiformis L.) cultivated with organic and bio-fertilizers in Grumusol soil. Curr. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2023, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allito, B.B.; Ewusi-Mensah, N.; Logah, V.; Hunegnaw, D.K. Legume-rhizobium specificity effect on nodulation, biomass production and partitioning of faba bean (Vicia faba L.). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.K.; Mattoo, A.K.; Schmidt, M.A. Rhizobial–host interactions and symbiotic nitrogen fixation in legume crops toward agriculture sustainability. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 669404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.K.; Habtewold, J.Z. Evaluation of legume–rhizobial symbiotic interactions beyond nitrogen fixation that help the host survival and diversification in hostile environments. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, D.; Frugoli, J. The regulation of nodule number in legumes is a balance of three signal transduction pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.K.; Dakora, F.D. Maximizing Photosynthesis and Plant Growth in African Legumes Through Rhizobial Partnerships: The Road Behind and Ahead. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesse-Smith, C.E.; Wang, Y.; Long, S.P. Increasing Rubisco as a simple means to enhance photosynthesis and productivity now without lowering nitrogen use efficiency. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakora, F.D. A functional relationship between leghaemoglobin and nitrogenase based on novel measurements of the two proteins in legume root nodules. Ann. Bot. 1995, 75, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, T.; van Dongen, J.T.; Gu, C.; Krusell, L.; Desbrosses, G.; Vigeolas, H.; Bock, V.; Czechowski, T.; Geigenberger, P.; Udvardi, M.K. Symbiotic leghemoglobins are crucial for nitrogen fixation in legume root nodules but not for general plant growth and development. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, N.K.; Singh, R.P.; Manchanda, G.; Dubey, R.C.; Maheshwari, D.K. Sunn hemp (Crotalaria juncea) nodulating bacteria capable for high antagonistic potential and plant growth promotion attributes: Sun hemp nodulating rhizobia. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2020, 10, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeron, A.; Maheshwari, D.K.; Dheeman, S.; Agarwal, M.; Dubey, R.C.; Bajpai, V.K. Plant growth promotion and suppression of charcoal-rot fungus (Macrophomina phaseolina) in velvet bean (Mucuna pruriens L.) by root nodule bacteria. J. Phytopathol. 2017, 165, 463–478. [Google Scholar]

- Mantelin, S.; Saux, M.F.-L.; Zakhia, F.; Béna, G.; Bonneau, S.; Jeder, H.; De Lajudie, P.; Cleyet-Marel, J.-C. Emended description of the genus Phyllobacterium and description of four novel species associated with plant roots: Phyllobacterium bourgognense sp. nov., Phyllobacterium ifriqiyense sp. nov., Phyllobacterium leguminum sp. nov. and Phyllobacterium brassicacearum sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safronova, V.; Belimov, A.; Sazanova, A.; Kuznetsova, I.; Popova, J.; Andronov, E.; Verkhozina, A.; Tikhonovich, I. Does the Miocene-Pliocene relict legume Oxytropis triphylla form nitrogen-fixing nodules with a combination of bacterial strains? Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 74, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andam, C.P.; Parker, M.A. Novel alphaproteobacterial root nodule symbiont associated with Lupinus texensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5687–5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins da Costa, E.; Almeida Ribeiro, P.R.; Soares de Carvalho, T.; Pereira Vicentin, R.; Balsanelli, E.; Maltempi de Souza, E.; Lebbe, L.; Willems, A.; de Souza Moreira, F.M. Efficient nitrogen-fixing bacteria isolated from soybean nodules in the semi-arid region of Northeast Brazil are classified as Bradyrhizobium brasilense (Symbiovar Sojae). Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 1746–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjei, J.A.; Aserse, A.A.; Yli-Halla, M.; Ahiabor, B.D.; Abaidoo, R.C.; Lindstrom, K. Phylogenetically diverse Bradyrhizobium genospecies nodulate Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc) and soybean (Glycine max L. Merril) in the northern savanna zones of Ghana. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2022, 98, fiac043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamisawa, K.; Onodera, S.; Tanimura, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Yuhashi, K.-I.; Kubota, M. Preferential nodulation of Glycine max, Glycine soja and Macroptilium atropurpureum by two Bradyrhizobium species japonicum and elkanii. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1997, 24, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaq, S.; Moin, A.; Pandit, B.; Tiwary, B.K.; Alam, M. Phyllobacteriaceae: A family of ecologically and metabolically diverse bacteria with the potential for different applications. Folia Microbiol. 2024, 69, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msaddak, A.; Durán, D.; Rejili, M.; Mars, M.; Ruiz-Argüeso, T.; Imperial, J.; Palacios, J.; Rey, L. Diverse bacteria affiliated with the genera Microvirga, Phyllobacterium, and Bradyrhizobium nodulate Lupinus micranthus growing in soils of Northern Tunisia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e02820-02816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| pH (KCl) | OM (%) | P2O5 | K2O | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg 100 g−1 soil | ||||

| Sampling site | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 19.4 ± 0.3 |

| Semi-controlled | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 12.7 ± 0.7 |

| Field conditions | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 15.4 ± 3.5 | 18.5 ± 2.4 |

| Isolate | Morphotype | Characterization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural a | Morphological | Growth (Days) | Acid or Base Production b | Nodule Formation c | Putative Identification d | ||

| 1R | I | 2–4 mm, semitranslucent, mucous | coccobacilli, Gram negative, not sporulated | 2 | base | − | Not determined |

| 9R | acid | − | |||||

| 13R | II | bacilli, Gram negative, sporulated | base | Not determined | |||

| 4R | III | 1–2 mm, pale orange non-mucous | bacilli, Gram negative, not sporulated | 3–5 | base | + | Phyllobacteriaceae or Methylobacteriaceae |

| 5R | 1–2 mm, light pink, non-mucous | 3–5 | base | + | |||

| 6R | 3 | base | + | ||||

| 7R | coccobacilli, Gram negative, not sporulated | 3 | base | + | |||

| IIB | IV | <1 mm, semitranslucent, non-mucous | bacilli, Gram negative, not sporulated | 7–10 | base | + | Nitrobacteraceae |

| IVB | 7–10 | base | − | Not determined | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferrás-Negrín, Y.; Bustamante-González, C.A.; Cid-Maldonado, J.; Villarroel-Contreras, M.J.; Hernández-Forte, I.; Herrera, H. Selection of Promising Rhizobia for the Inoculation of Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC. (Fabaceae) in Chromic Eutric Cambisol Soils. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121534

Ferrás-Negrín Y, Bustamante-González CA, Cid-Maldonado J, Villarroel-Contreras MJ, Hernández-Forte I, Herrera H. Selection of Promising Rhizobia for the Inoculation of Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC. (Fabaceae) in Chromic Eutric Cambisol Soils. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121534

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerrás-Negrín, Yusdel, Carlos Alberto Bustamante-González, Javiera Cid-Maldonado, María José Villarroel-Contreras, Ionel Hernández-Forte, and Hector Herrera. 2025. "Selection of Promising Rhizobia for the Inoculation of Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC. (Fabaceae) in Chromic Eutric Cambisol Soils" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121534

APA StyleFerrás-Negrín, Y., Bustamante-González, C. A., Cid-Maldonado, J., Villarroel-Contreras, M. J., Hernández-Forte, I., & Herrera, H. (2025). Selection of Promising Rhizobia for the Inoculation of Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC. (Fabaceae) in Chromic Eutric Cambisol Soils. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121534