Strawberry Fruit Softening Driven by Cell Wall Metabolism, Gene Expression, Enzyme Activity, and Phytohormone Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Firmness and SSC Measurement

2.3. Histochemical Staining and Electron Microscopy Observation of Cell Wall Ultrastructure

2.4. Extraction and Measurement of Cell Wall Materials

2.5. Analysis of Cell Wall Metabolizing Enzyme Activity

2.6. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Fluorescence PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Determination of Phytohormones

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

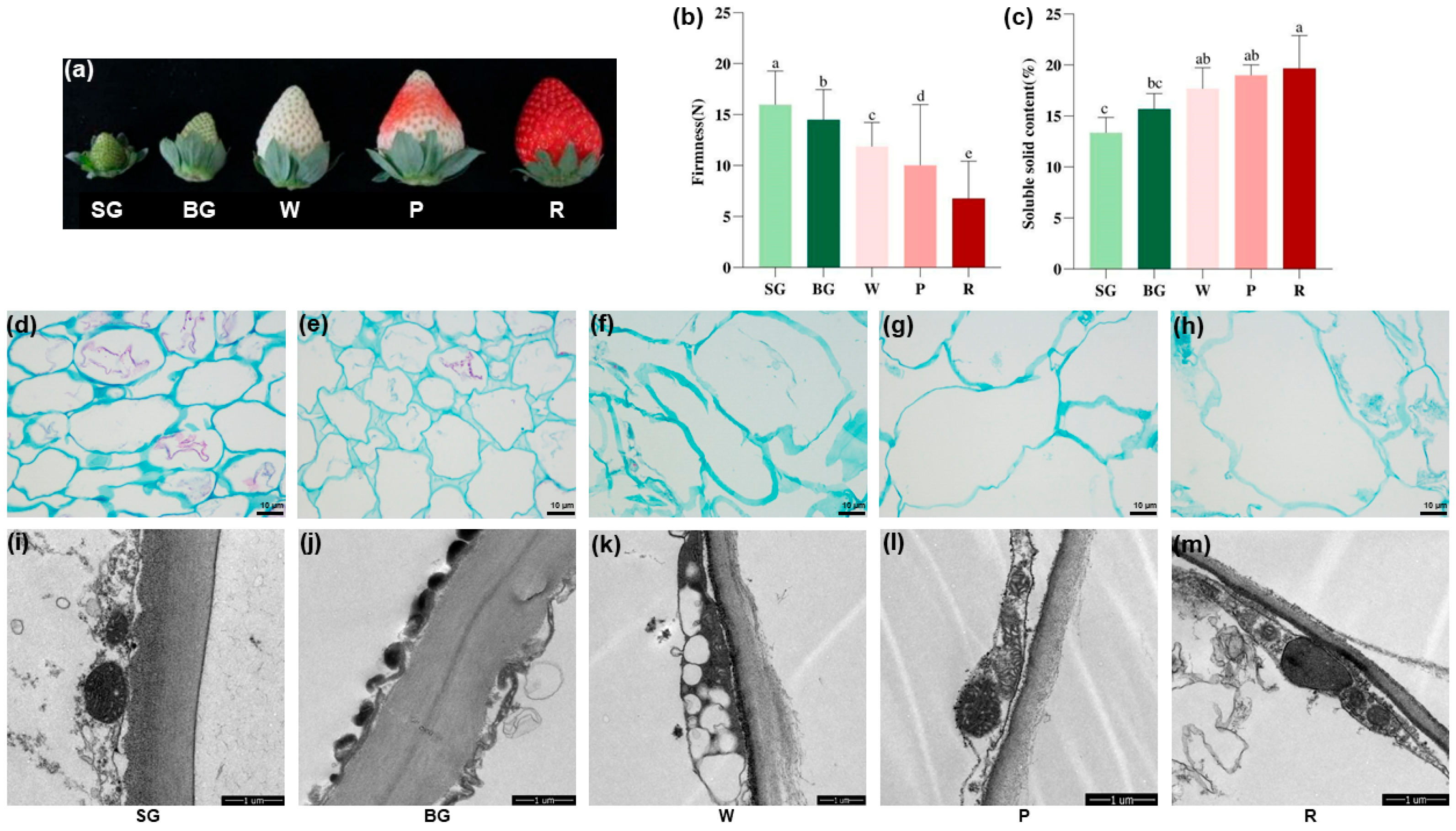

3.1. Changes in Firmness, SSC, and Cell Microstructure During Strawberry Ripening

3.2. Changes in Cell Wall Material During Strawberry Ripening

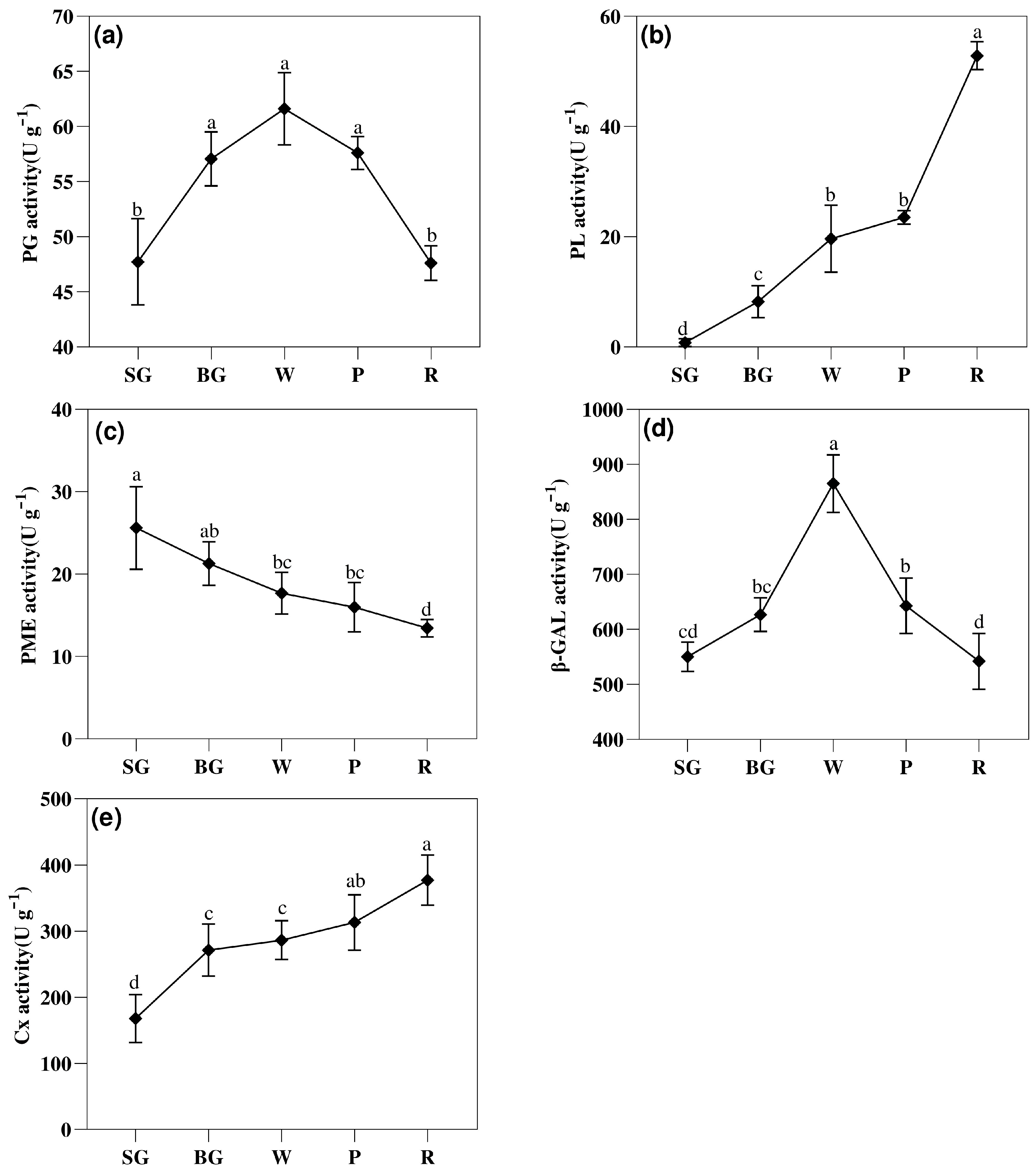

3.3. Changes in the Activities of Cell Wall Metabolizing Enzymes During Strawberry Ripening

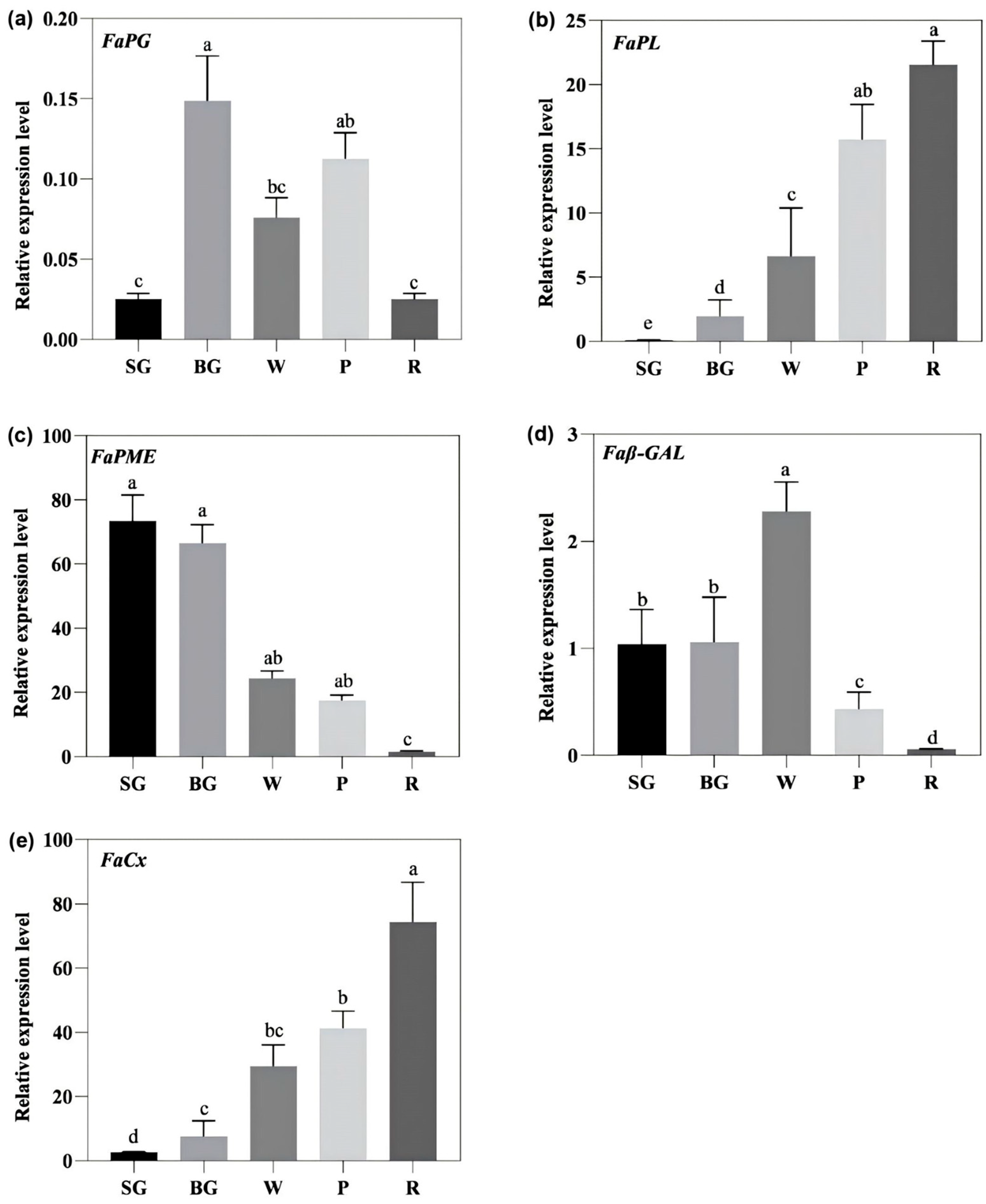

3.4. Changes in the Expression of Cell Wall Metabolism-Related Genes During Strawberry Ripening

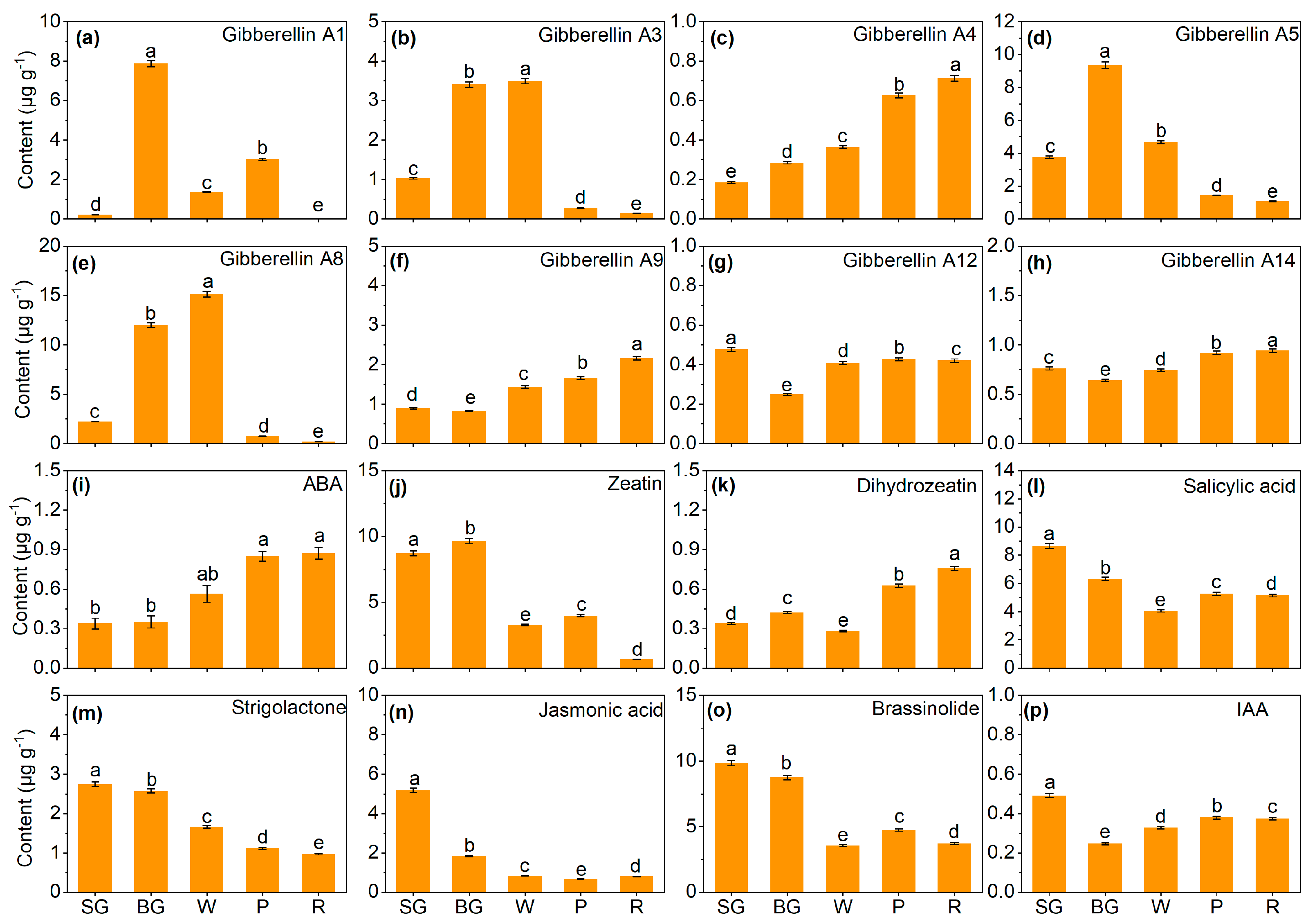

3.5. Changes in Endogenous Phytohormones Contents During Strawberry Ripening

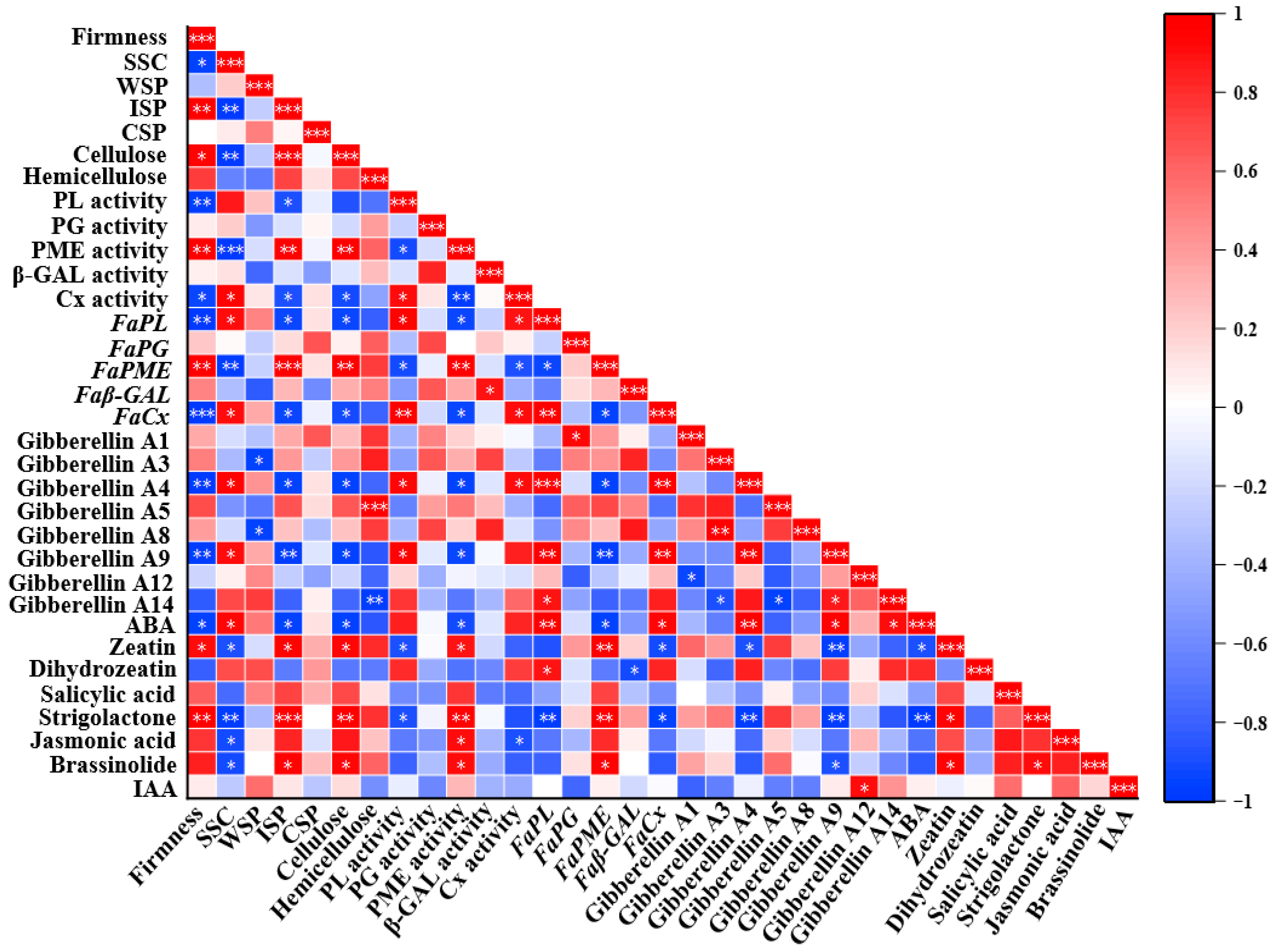

3.6. Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, B.C.; Gao, Y.H.; Zhang, L.J.; Zhou, Y.H. The plant cell wall: Biosynthesis, construction, and functions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 63, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husnayain, N.; Adi, P.; Mulyani, R.; Tsai, S.Y.; Chang, C.K.; Punthi, F.; Yudhistira, B.; Cheng, K.C.; Hsieh, C.W. Active packaging of chitosan-casein phosphopeptide modified plasma–treated LDPE for CO2 regulation to delay texture softening and maintain quality of fresh-cut slice persimmon during storage. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 5532–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.N.; Li, B.J.; Grierson, D.; Chen, K.S. Insights into cell wall changes during fruit softening from transgenic and naturally occurring mutants. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1671–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.; Gomez-Jimenez, M.C. Spatio–temporal immunolocalization of extensin protein and hemicellulose polysaccharides during olive fruit abscission. Planta 2020, 252, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.J.; Xia, X.Z.; Li, L.L.; Song, L.L.; Ye, Y.P.; Jiang, Y.M.; Liu, H. Elucidation of pineapple softening based on cell wall polysaccharides degradation during storage. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1492575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya León, M.A.; Mattus Araya, E.; Herrera, R. Molecular events occurring during softening of strawberry fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.D.; Yeats, T.H.; Uluisik, S.; Rose, J.K.C.; Seymour, G.B. Fruit softening: Revisiting the role of pectin. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Wu, L.M.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; He, L.G.; Wang, Z.J.; Ma, X.F.; Bai, F.X.; Feng, G.Z.; Liu, J.H.; et al. Characterization of pectin methylesterase gene family and its possible role in juice sac granulation in navel orange (Citrus sinensis Osbeck). BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.J.; Yang, H.Y.; Jiao, J.Y.; Wang, F.; Lu, Y.Y.; Deng, J. Effects of graft copolymer of chitosan and salicylic acid on reducing rot of postharvest fruit and retarding cell wall degradation in grapefruit during storage. Food Chem. 2018, 283, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Brummell, D.A.; Lin, Q.; Duan, Y.Q. Abscisic acid treatment prolongs the postharvest life of strawberry fruit by regulating sucrose and cell wall metabolism. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 104054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.I.; González Feliu, A.; Muñoz Vera, M.; Valenzuela Riffo, F.; Parra Palma, C.; Morales Quintana, L. Effect of exogenous auxin treatment on cell wall polymers of strawberry fruit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Chen, C.; Yan, Z.M.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.H. The methyl jasmonate accelerates the strawberry fruits ripening process. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 249, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gačnik, S.; Veberič, R.; Hudina, M.; Koron, D.; Mikulič Petkovšek, M. Salicylate treatment affects fruit quality and also alters the composition of metabolites in strawberries. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, X.Y.; Hou, G.Y.; Jiang, Y.Y.; She, M.S.; He, C.X.; Peng, Y.T.; Lin, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.T.; et al. Pre-harvest application of strigolactone (GR24) accelerates strawberry ripening and improves fruit auality. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, M.; Roussel, B.; Chavez, D.J.; Malladi, A. Synthesis of active cytokinins mediated by LONELY GUY is associated with cell production during early fruit growth in peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch]. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1155755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furio, R.N.; Salazar, S.M.; Mariotti Martínez, J.A.; Martínez Zamora, G.M.; Coll, Y.; Díaz Ricci, J.C. Brassinosteroid applications enhance the tolerance to abiotic stresses, production and quality of strawberry fruits. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.X.; Sharmin, N.; Wu, T.; Pang, C.H. An investigation on plant cell walls during biomass pyrolysis: A histochemical perspective on engineering applications. Appl. Energy 2023, 343, 121055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, J.; Yu, Y.; Aisikaer, G.; Ying, T. Postharvest UV-C irradiation inhibits the production of ethylene and the activity of cell wall-degrading enzymes during softening of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 86, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.T.; Zhu, X.; Hou, Y.Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Li, X.H. Effects of nitric oxide fumigation treatment on retarding cell wall degradation and delaying softening of winter jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill. cv. Dongzao) fruit during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 156, 110954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.P.; Zhang, L.B.; Zhang, L.H.; Ge, Z.Z.; Li, G.; Wang, L.; Zong, W. Combination of intense pulsed light and modified atmosphere packaging delays the texture softening of apricot fruit by inhibiting the degradation of pectin components. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 340, 113918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Ding, J.; Liu, C.Y.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, C.L.; Lin, Y.Z.; Sameen, D.E.; Hossen, M.A.; Chen, M.R.; Yan, J.; et al. Konjac glucomannan/low-acyl gellan gum edible coating containing thymol microcapsule regulates cell wall polysaccharides disassembly and delays postharvest softening of blueberries. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 204, 112449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.Y.; Li, L.; Xu, Y.Q.; Li, D.; Li, G.F.; Yan, Y.Q.; Wu, Q.; Luo, Z.S. FaLEC2 repressing FaLOX2 promoter involved in the metabolism of LOX-derived volatiles during strawberry ripening. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 303, 111188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, M.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Arbona, V. Rapid and reproducible determination of active gibberellins in citrus tissues by UPLC/ESI-MS/MS. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 94, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkova, K.; Veberic, R.; Hudina, M.; Grohar, M.C.; Pelacci, M.; Smrke, T.; Ivancic, T.; Cvelbar Weber, N.; Jakopic, J. Non-destructive and destructive physical measurements as indicators of sugar and organic acid contents in strawberry fruit during ripening. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 327, 112843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.R.; Kang, S.Z.; Chen, J.L. SUGAR model-assisted analysis of carbon allocation and transformation in tomato fruit under different water along with potassium conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Han, S.K.; Ban, Q.Y.; He, Y.H.; Jin, M.J.; Rao, J.P. Overexpression of persimmon DkXTH1 enhanced tolerance to abiotic stress and delayed fruit softening in transgenic plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.W.; Zhao, S.Q.; Zhang, L.C.; Xing, Y.; Jia, W.S. Changes in the cell wall during fruit development and ripening in Fragaria vesca. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 154, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Hung, Y.C.; Chen, M.Y.; Lin, H.T. Effects of acidic electrolyzed oxidizing water on retarding cell wall degradation and delaying softening of blueberries during postharvest storage. LWT 2017, 84, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; He, H.; Hou, Y.Y.; Kelimu, A.; Wu, F.; Zhao, Y.T.; Shi, L.; Zhu, X. Salicylic acid treatment delays apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) fruit softening by inhibiting ethylene biosynthesis and cell wall degradation. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 300, 111061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Q.; Zhao, M.L.; Ma, X.S.; Wen, Z.X.; Ying, P.Y.; Peng, M.J.; Ning, X.P.; Xia, R.; Wu, H.; Li, J.G. The HD-Zip transcription factor LcHB2 regulates litchi fruit abscission through the activation of two cellulase genes. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 5189–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, C.; Guan, S.C.; Chen, J.Q.; Wen, C.J.; Cai, J.F.; Chen, X. Genome wide identification and functional characterization of strawberry pectin methylesterases related to fruit softening. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.X.; He, H.; Wen, Y.L.; Cao, S.P.; Wang, Z.S.; Sun, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.T.; Wang, Y.; He, W.; Li, M.Y.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of the pectate lyase gene family and the role of FaPL1 in strawberry softening. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.L.; Fang, S.Q.; Jia, R.J.; Wang, Z.D.; Fu, J.H.; Guo, J.H.; Yang, H.J.; Zhao, Z.Y. Comparison of cell wall changes of two different types of apple cultivars during fruit development and ripening. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 2705–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.F.; Lin, Y.Z.; Lin, Y.X.; Lin, M.X.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, H.; Lin, H.T. A novel chitosan alleviates pulp breakdown of harvested longan fruit by suppressing disassembly of cell wall polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 217, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.Q.; Charles, M.T.; Luo, Z.S.; Mimee, B.; Tong, Z.C.; Véronneau, P.Y.; Roussel, D.; Rolland, D. Ultraviolet-C priming of strawberry leaves against subsequent Mycosphaerella fragariae infection involves the action of reactive oxygen species, plant hormones, and terpenes. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csukasi, F.; Osorio, S.; Gutierrez, J.R.; Kitamura, J.; Giavalisco, P.; Nakajima, M.; Fernie, A.R.; Rathjen, J.P.; Botella, M.A.; Valpuesta, V.; et al. Gibberellin biosynthesis and signalling during development of the strawberry receptacle. New Phytol. 2011, 191, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.D.; Mou, W.S.; Xia, R.; Li, L.; Zawora, C.; Ying, T.J.; Mao, L.C.; Liu, Z.C.; Luo, Z.S. Integrated analysis of high-throughput sequencing data shows abscisic acid-responsive genes and miRNAs in strawberry receptacle fruit ripening. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.I.; Gonzalez-Feliu, A.; Valenzuela-Riffo, F.; Parra-Palma, C.; Morales-Quintana, L. Changes in the cell wall components produced by exogenous abscisic acid treatment in strawberry fruit. Cellulose 2021, 28, 1555–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, F.; Ji, S.; Dai, H.; Zhou, X.; Wei, B.; Cheng, S.; Wang, A. Abscisic acid accelerates postharvest blueberry fruit softening by promoting cell wall metabolism. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 288, 110325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mao, L.; Lu, W.; Ying, T.; Luo, Z. Transcriptome profiling of postharvest strawberry fruit in response to exogenous auxin and abscisic acid. Planta 2016, 243, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Peng, X.; Feng, C.; Zhang, X.; Du, B.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; et al. Abscisic acid-responsive transcription factors PavDof2/6/15 mediate fruit softening in sweet cherry. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 2501–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.B.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, Y.H.; Choi, Y.W.; Son, B.G.; Kang, N.J.; Je, B.I.; Kang, J.S. Phytohormone profiles of ‘Seolhyang’ and ‘Maehyang’ strawberry fruits during ripening. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, H.H.; Chen, H.; Qi, Q.; Ding, Q.Q.; Xue, J.; Ding, J.; Jiang, X.N.; Hou, X.L.; Li, Y. Identification and expression analysis of strigolactone biosynthetic and signaling genes reveal strigolactones are involved in fruit development of the woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Li, M.S.; Liu, B.; Yan, M.L.; Yu, X.M.; Zi, H.L.; Liu, R.Y.; Yamamuro, C. Interlinked regulatory loops of ABA catabolism and biosynthesis coordinate fruit growth and ripening in woodland strawberry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11542–11550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, L.J.; Chai, P.; Chen, S.W.; Flaishman, M.A.; Ma, H.Q. Transcriptome analysis unravels spatiotemporal modulation of phytohormone-pathway expression underlying gibberellin-induced parthenocarpic fruit set in San Pedro-type fig (Ficus carica L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.N.; Xu, X.L.; Wu, J.R.; Fang, Y.L.; Ju, Y.L. Effects of strigolactone and abscisic acid on the quality and antioxidant activity of grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) and wines. Food Chem. X 2022, 16, 100496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.Y.; Sun, P.P.; Wang, X.Z.; Zhu, Z.Y. Degradation of cell wall polysaccharides and change of related enzyme activities with fruit softening in Annona squamosa during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 166, 111203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teribia, N.; Tijero, V.; Munné Bosch, S. Linking hormonal profiles with variations in sugar and anthocyanin contents during the natural development and ripening of sweet cherries. New Biotechnol. 2016, 33, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.P.; Zhao, L.; Cao, Y.P.; Ai, D.; Li, M.Y.; You, C.X.; Han, Y.P. The SMXL8-AGL9 module mediates crosstalk between strigolactone and gibberellin to regulate strigolactone-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in apple. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 4404–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, H.; Yu, Q.; Li, M. Strawberry Fruit Softening Driven by Cell Wall Metabolism, Gene Expression, Enzyme Activity, and Phytohormone Dynamics. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121533

Lu H, Yu Q, Li M. Strawberry Fruit Softening Driven by Cell Wall Metabolism, Gene Expression, Enzyme Activity, and Phytohormone Dynamics. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121533

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Hongyan, Qiling Yu, and Mengyan Li. 2025. "Strawberry Fruit Softening Driven by Cell Wall Metabolism, Gene Expression, Enzyme Activity, and Phytohormone Dynamics" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121533

APA StyleLu, H., Yu, Q., & Li, M. (2025). Strawberry Fruit Softening Driven by Cell Wall Metabolism, Gene Expression, Enzyme Activity, and Phytohormone Dynamics. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121533