Concentration-Dependent Effects of Foliar ZnO Nanoparticles on Growth and Nutrient Use in Young Crabapple Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Treatment

2.2. Growth Index Determination

2.3. Relative Growth Rate (RGR)

2.4. Root Architecture Analysis

2.5. Biochemical Assays (MDA, H2O2, CAT, SOD, POD)

2.6. Total Nitrogen (N)

2.7. Phosphorus, Potassium, Calcium, Magnesium, and Trace Elements

2.8. Element Absorption Flux (Jupt)

2.9. Element Accumulation and Transfer

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

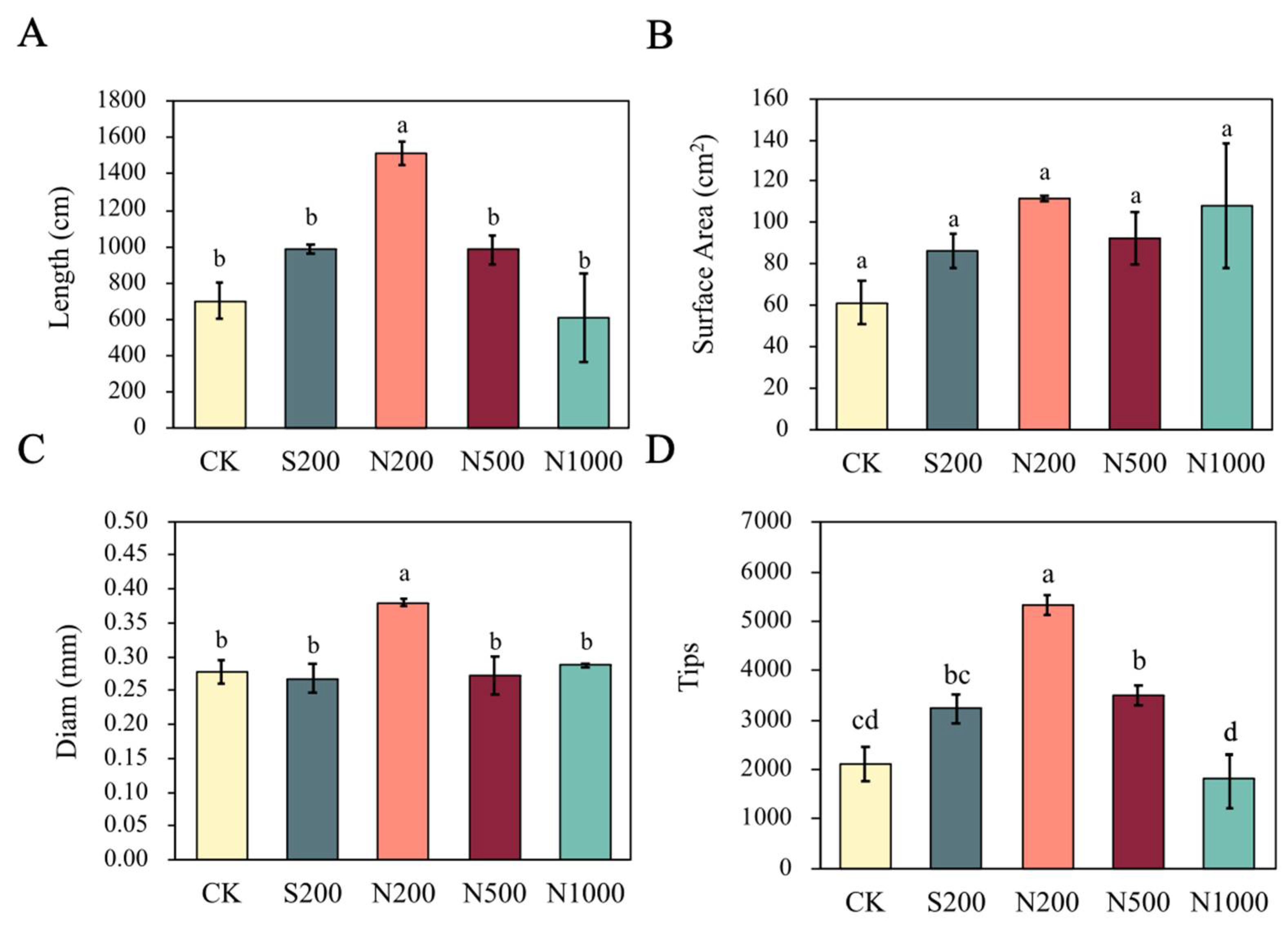

3.1. Plant Growth and Morphological Parameters

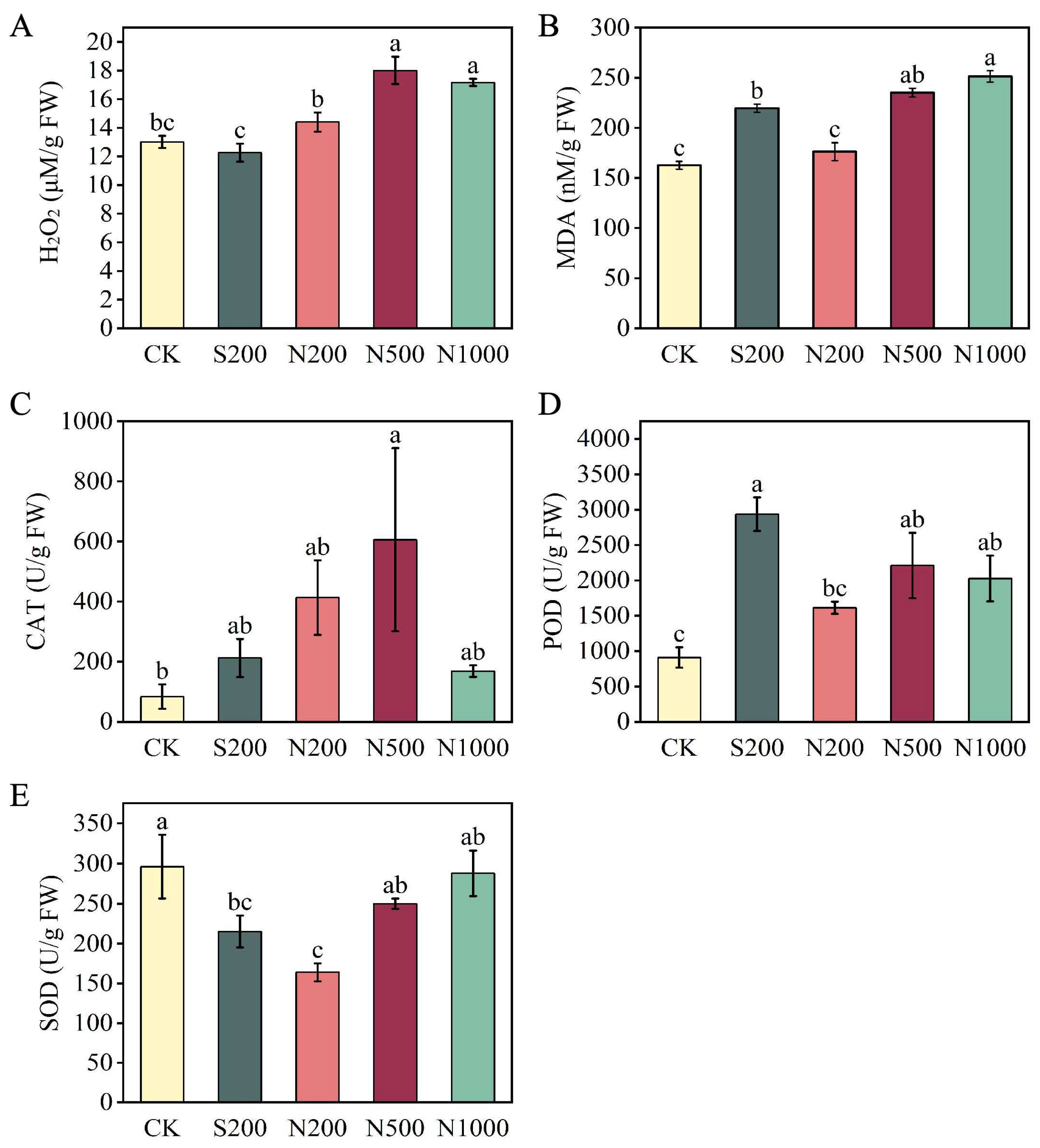

3.2. Oxidative Stress Indicators and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

3.3. Mineral Nutrient Concentrations

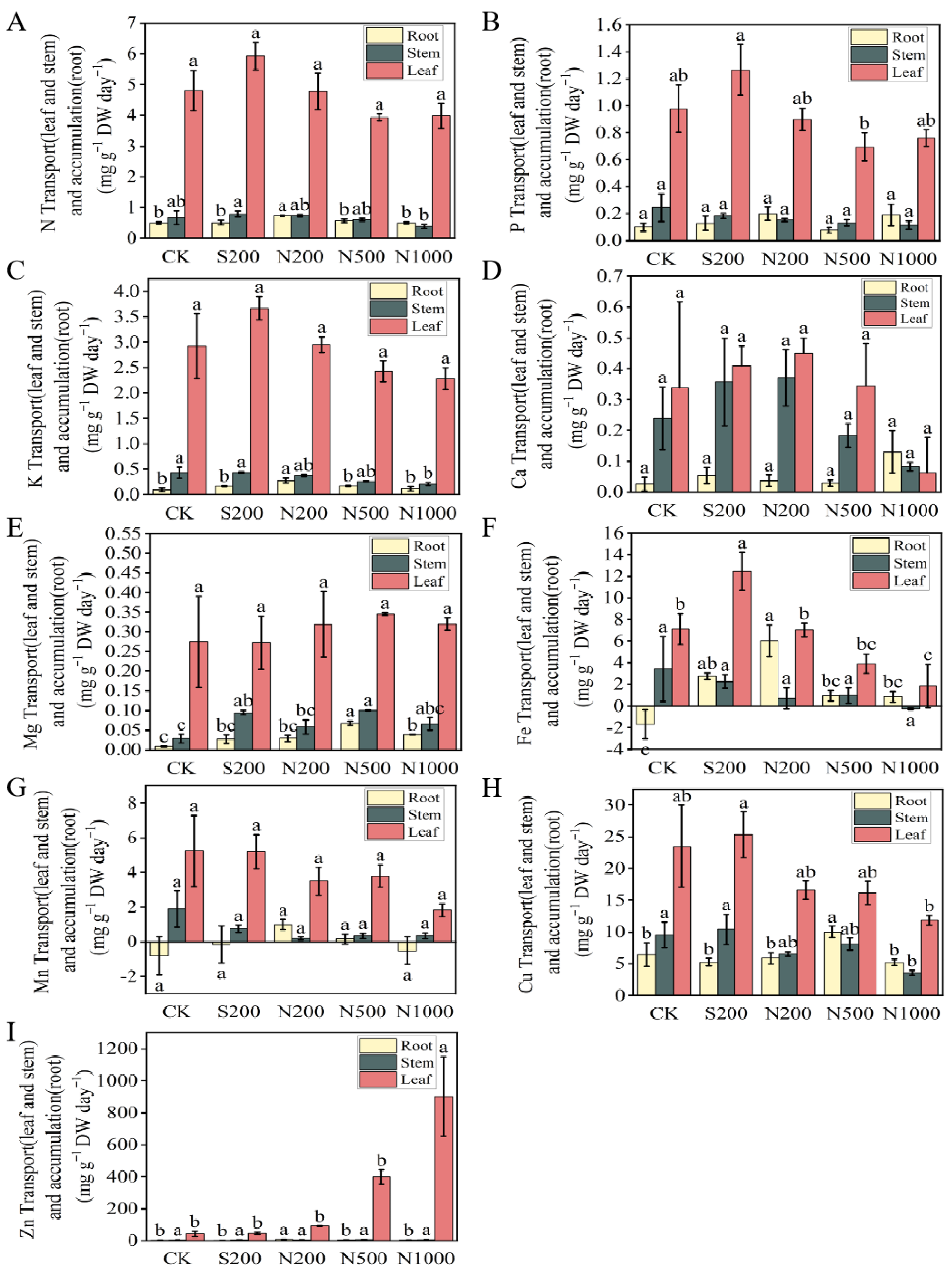

3.4. Nutrient Uptake and Allocation Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Concentration-Dependent Effects of ZnO NPs on Plant Growth Promotion

4.2. Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms Mitigating ZnO NP-Induced Oxidative Stress

4.3. Altered Mineral Nutrient Dynamics Under Foliar-Applied ZnO NPs

4.4. Mechanisms of Nutrient Uptake and Allocation Responses to ZnO NP Treatments

4.5. Integrative Adaptive Strategies of Young Crabapple Plants Responses to ZnO NPs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baligar, V.C.; Fageria, N.K.; He, Z.L. Nutrient use efficiency in plants. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2001, 32, 921–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Xian, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. Nano-zinc oxide can enhance the tolerance of apple rootstock M9-T337 seedlings to saline alkali stress by initiating a variety of physiological and biochemical pathways. Plants 2025, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, A.; Sharma, I.; Singh, R.; Rana, M. Nanotechnology for sustainability of agriculture and environment: Green synthesis and application of nanoparticles—A review. Res. Crops 2024, 25, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourgialas, N.; Karatzas, G.; Koubouris, G. A GIS policy approach for assessing the effect of fertilizers on the quality of drinking and irrigation water and wellhead protection zones (Crete, Greece). J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 189, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Díaz, A.; Ortega-Ortíz, H.; Juárez-Maldonado, A.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; González-Morales, S.; Benavides-Mendoza, A. Application of nanoelements in plant nutrition and its impact in ecosystems. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raliya, R.; Saharan, V.; Dimkpa, C.; Biswas, P. Nanofertilizer for precision and sustainable agriculture: Current state and future perspectives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6487–6503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davarpanah, S.; Tehranifar, A.; Davarynejad, G.; Abadía, J.; Khorasani, R. Effects of foliar applications of zinc and boron nano-fertilizers on pomegranate (Punica granatum cv. Ardestani) fruit yield and quality. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 210, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, M.; Kookana, R.; Gogos, A.; Bucheli, T. A critical evaluation of nanopesticides and nanofertilizers against their conventional analogues. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichert, T.; Kurtz, A.; Steiner, U.; Goldbach, H.E. Size exclusion limits and lateral heterogeneity of the stomatal foliar uptake pathway for aqueous solutes and water-suspended nanoparticles. Physiol. Plant 2008, 134, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Green, A. Zinc in crops and human health. In Biofortification Ofood Crops; Singh, U., Praharaj, C., Singh, S., Singh, N., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2016; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbar, S.; Rahemi, M.; Ramezanian, A. Comparison of nano-calcium and calcium chloride spray on postharvest quality and cell wall enzymes activity in apple cv. Red Delicious. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheery, N.; Helaly, M.; El-Hoseiny, H.; Alam-Eldein, S. Zinc oxide and silicone nanoparticles to improve the resistance mechanism and annual productivity of salt-stressed mango trees. Agronomy 2020, 10, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genaidy, E.; Abd-Alhamid, N.; Hassan, H.; Hassan, A.; Hagagg, L. Effect of foliar application of boron trioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles on leaves chemical composition, yield and fruit quality of Olea europaea L. cv. Picual. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, J.; Niño-Medina, G.; Olivares-Sáenz, E.; Lira-Saldivar, R.; Barriga-Castro, E.; Vázquez-Alvarado, R.; Rodríguez-Salinas, P.; Zavala-García, F. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles and zinc sulfate boosts the content of bioactive compounds in habanero peppers. Plants 2019, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Vargas, E.; Ortega-Ortíz, H.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; De Alba Romenus, K.; Cabrera de la Fuente, M.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Foliar application of copper nanoparticles increases the fruit quality and the content of bioactive compounds in tomatoes. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Kalia, A. Nano-enabled technological interventions for sustainable production, protection, and storage of fruit crops. In Nanoscience for Sustainable Agriculture; Pudake, R., Chauhan, N., Kole, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 299–322. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, R.; Chettri, N.; Kumar, R.; Roshan, R.; Kumari, P.; Sonkar, S.; Kumari, S.; Rongpi, A. Nanotechnology interventions in fruit production: Enhancing production and quality. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2024, 36, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.; Korolev, K.; Ahmad, R. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: Abiotic stress tolerance in fruit crops focusing on sustainable production. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 94, 1401–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, T.; Safdar, A.; Qureshi, H.; Siddiqi, E.H.; Ullah, N.; Naseem, M.T.; Soufan, W. Synergistic effects of Vachellia nilotica-derived zinc oxide nanoparticles and melatonin on drought tolerance in Fragaria × ananassa. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, G.; Wijesekara, T.; Kumawat, K.; Adhikari, P.; Joshi, K.; Singh, S.; Farda, B.; Djebaili, R.; Sabbi, E.; Ramila, F.; et al. Nanomaterials–plants–microbes interaction: Plant growth promotion and stress mitigation. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1516794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Bashir, S.; Bashir, S.; Aslam, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Younas, T.; Asghar, R.M.A.; Alkahtani, J.; Dwiningsih, Y.; Elshikh, M.S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles improved chlorophyll contents, physical parameters, and wheat yield under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 932861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarin, K.; Usatov, A.; Minkina, T.; Plotnikov, A.; Kasyanova, A.; Fedorenko, A.; Duplii, N.; Vechkanov, E.; Rajput, V.D.; Mandzhieva, S.; et al. Effects of ZnO nanoparticles and its bulk form on growth, antioxidant defense system and expression of oxidative stress related genes in Hordeum vulgare L. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, H. Effect of ZnO and CuO nanoparticles on the growth, nutrient absorption, and potential health risk of the seasonal vegetable Medicago polymorpha L. Peer J. 2022, 10, e14038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, R.; Ju, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J. Comparative physiological and transcriptomic analyses reveal the toxic effects of ZnO nanoparticles on plant growth. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4235–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Garg, T.; Joshi, A.; Awasthi, A.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A. Potential effects of metal oxide nanoparticles on leguminous plants: Practical implications and future perspectives. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 331, 113146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Kumari, N.; Sharma, V. Zinc oxide nanoparticles improve photosynthesis by modulating antioxidant system and psb a gene expression under arsenic stress in different cultivars of Vigna radiata. Bionanoscience 2025, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkhosh, S.; Kahrizi, D.; Darvishi, E.; Tourang, M.; Haghighi-Mood, S.; Vahedi, P.; Ercisli, S. Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) on seed germination characteristics in two brassicaceae family species: Camelina sativa and Brassica napus L. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 1892759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, A.; Ganjewala, D.; Singhal, R.; Rajput, V.; Minkina, T.; Voloshina, M.; Srivastava, S.; Shrivastava, M. Effect of ZnO nanoparticles on growth and biochemical responses of wheat and maize. Plants 2021, 10, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y. Morphology, photosynthesis, and internal structure alterations in field apple leaves under hidden and acute zinc deficiency. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 193, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthakrishnan, S.; Sharma, J.C.; Sharma, N.; Ranjha, R.; Vishnu Shankar, S. Comparative efficiency of nano, chelated, and sulfate zinc foliar applications in high-density apple orchards. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 1646–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, J.; Liu, G.; Yao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Liu, N.; He, Y.; Il, D.; Tusupovich, J.; Jiang, Z. ZnO NPs impair the viability and function of porcine granulosa cells through autophagy regulated by ROS production. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Gao, T.; Zhao, Q.; Ma, C.; Chen, Q.; Wei, Z.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Ma, F. Effects of exogenous dopamine on the uptake, transport, and resorption of apple ionome under moderate drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Su, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, R.; Ma, L.; Chen, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, L. Integrated efficacy evaluation of mist and drip irrigation on vegetative performance of young apple trees. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 346, 114182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddasi, S.; Fotovat, A.; Khoshgoftarmanesh, A.; Karimzadeh, F.; Khazaei, H.; Khorassani, R. Bioavailability of coated and uncoated ZnO nanoparticles to cucumber in soil with or without organic matter. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 144, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Kumar, A. Impact of irrigation using water containing CuO and ZnO nanoparticles on spinach oleracea grown in soil media. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 97, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Liu, X.; Shi, Z.; Tong, R.; Adams, C.; Shi, X. Arbuscular mycorrhizae alleviate negative effects of zinc oxide nanoparticle and zinc accumulation in maize plants—A soil microcosm experiment. Chemosphere 2016, 147, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.; Hansen, T.; Stewart, J.; McLean, J.; Britt, D.; Anderson, A. ZnO nanoparticles and root colonization by a beneficial pseudomonad influence essential metal responses in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Nanotoxicology 2015, 9, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Plascencia-Villa, G.; Mukherjee, A.; Rico, C.M.; José-Yacamán, M.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Comparative phytotoxicity of ZnO NPs, bulk ZnO, and ionic zinc onto the alfalfa plants symbiotically associated with Sinorhizobium meliloti in soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 515–516, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Salvador, P.; Uscola, M.; Jacobs, D. The role of stored carbohydrates and nitrogen in the growth and stress tolerance of planted forest trees. New For. 2015, 46, 813–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Ali, B.; Adrees, M.; Arshad, M.; Hussain, A.; Zia ur Rehman, M.; Waris, A. Zinc and iron oxide nanoparticles improved the plant growth and reduced the oxidative stress and cadmium concentration in wheat. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Ram, H.; Kumar, B. Mechanism of Zinc absorption in plants: Uptake, transport, translocation and accumulation. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2016, 15, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, T.; Maharajan, T.; Ceasar, S. The role of membrane transporters in the biofortification of zinc and iron in plants. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Shen, Y.; Liu, S.; Zeng, N.; Zhan, X.; White, J.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.; Xing, B. Mechanism of zinc oxide nanoparticle entry into wheat seedling leaves. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 3901–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, J.; Singh, A.; Tiwari, M.; Prasad, P.; Jagadish, S. Effective use of water in crop plants in dryland agriculture: Implications of reactive oxygen species and antioxidative system. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 778270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larocca, G.; Baldi, E.; Toselli, M. Understanding the role of calcium in kiwifruit: Ion transport, signaling, and fruit quality. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Liu, C.; Qin, H.; Zhang, X.; Tian, G.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Magnesium alleviates aluminum-induced growth inhibition by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity and carbon–nitrogen metabolism in apple seedlings. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; He, Y.; Gao, Y.; Chen, S.; Gu, T.; Peng, J. NnMTP10 from Nelumbo nucifera acts as a transporter mediating manganese and iron efflux. Plant Mol. Biol. 2025, 115, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Hong, J.; Lei, L.; Weia, S. Uptake and translocation of ZnO nanoparticles in rice tissues studied by single particle-ICP-MS. At. Spectrosc. 2023, 44, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, E.; Michlewska, S.; Pietrzak, M.; Wolf, W. Additive interactions of nanoparticulate ZnO with copper, manganese and iron in Pisum sativum L., a hydroponic study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Guo, J. Responses of physiological, morphological and anatomical traits to abiotic stress in woody plants. Forests 2023, 14, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, J.; Marcati, C.; Olson, M.; Lagunes, X.; Vergilio, P.; Jiménez-Vera, C.; Campo, J. Inner bark vs sapwood is the main driver of nitrogen and phosphorus allocation in stems and roots across three tropical woody plant communities. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 1665–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tissue | Treatment | N (mg g−1) | P (mg g−1) | K (mg g−1) | Ca (mg g−1) | Mg (mg g−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | % | Value | % | Value | % | Value | % | Value | % | ||

| root | CK | 19.57 ± 0.65 a | 5.46 ± 1.54 a | 7.61 ± 0.23 a | 4.18 ± 0.46 bc | 0.76 ± 0.15 c | |||||

| S200 | 17.11 ± 0.77 a | −12.57 | 6.91 ± 1.17 a | 26.56 | 8.06 ± 0.41 a | 5.91 | 4.68 ± 0.50 b | 11.96 | 1.27 ± 0.29 bc | 67.11 | |

| N200 | 18.71 ± 0.97 a | −4.39 | 6.65 ± 0.85 a | 21.79 | 8.52 ± 0.85 a | 11.96 | 2.58 ± 0.27 c | −38.28 | 1.00 ± 0.18 c | 31.58 | |

| N500 | 17.39 ± 1.10 a | −11.14 | 4.99 ± 0.60 a | −8.61 | 7.38 ± 0.39 a | −3.02 | 3.55 ± 0.32 bc | −15.07 | 2.16 ± 0.07 a | 184.21 | |

| N1000 | 17.60 ± 0.82 a | −10.07 | 8.77 ± 1.24 a | 60.62 | 7.16 ± 0.22 a | −5.91 | 6.88 ± 1.03 a | 64.59 | 1.65 ± 0.19 ab | 117.11 | |

| stem | CK | 10.94 ± 0.21 a | 3.59 ± 1.62 a | 7.20 ± 1.48 a | 4.42 ± 0.15 a | 0.61 ± 0.12 c | |||||

| S200 | 11.35 ± 1.44 a | 3.75 | 2.50 ± 0.54 a | −30.36 | 6.27 ± 0.58 a | −12.92 | 5.34 ± 1.38 a | 20.81 | 1.02 ± 0.50 bc | 67.21 | |

| N200 | 11.16 ± 1.50 a | 2.01 | 2.19 ± 0.30 a | −39.00 | 5.63 ± 0.22 a | −21.81 | 5.57 ± 0.75 a | 26.02 | 0.96 ± 0.37 bc | 57.38 | |

| N500 | 12.93 ± 0.99 a | 18.19 | 2.57 ± 0.44 a | −28.41 | 5.83 ± 0.22 a | −19.03 | 4.67 ± 0.78 a | 5.66 | 2.01 ± 0.03 a | 229.51 | |

| N1000 | 12.09 ± 0.61 a | 10.51 | 2.94 ± 0.52 a | −18.11 | 6.50 ± 0.44 a | −9.72 | 4.01 ± 0.22 a | −9.28 | 1.82 ± 0.21 ab | 198.36 | |

| leaf | CK | 27.35 ± 0.33 a | 4.97 ± 0.20 a | 16.07 ± 0.78 a | 2.33 ± 0.71 a | 1.55 ± 0.10 ab | |||||

| S200 | 28.17 ± 0.43 a | 3.00 | 5.62 ± 1.18 a | 13.08 | 16.85 ± 0.89 a | 4.85 | 2.46 ± 0.12 a | 5.58 | 1.44 ± 0.39 b | −7.10 | |

| N200 | 28.16 ± 1.73 a | 2.96 | 4.88 ± 0.05 a | −1.81 | 16.80 ± 0.46 a | 4.54 | 3.02 ± 0.07 a | 29.61 | 1.84 ± 0.32 ab | 18.71 | |

| N500 | 27.84 ± 0.30 a | 1.79 | 4.48 ± 0.63 a | −9.86 | 16.28 ± 0.69 a | 1.31 | 2.96 ± 0.65 a | 27.04 | 2.26 ± 0.07 a | 45.81 | |

| N1000 | 28.53 ± 0.89 a | 4.31 | 4.85 ± 0.37 a | −2.41 | 15.78 ± 0.47 a | −1.80 | 1.69 ± 0.54 a | −27.47 | 2.15 ± 0.04 ab | 38.71 | |

| Tissue | Treatment | Fe (μg g−1) | Mn (μg g−1) | Cu (μg g−1) | Zn (μg g−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | % | Value | % | Value | % | Value | % | ||

| root | CK | 83.51 ± 39.50 b | 62.43 ± 25.49 a | 223.34 ± 46.77 ab | 166.55 ± 60.08 ab | ||||

| S200 | 146.95 ± 36.00 ab | 75.97 | 62.71 ± 20.62 a | 0.45 | 167.52 ± 7.13 b | −24.99 | 120.91 ± 5.90 b | −27.40 | |

| N200 | 197.71 ± 25.08 a | 136.75 | 65.34 ± 2.94 a | 4.66 | 150.88 ± 25.23 b | −32.44 | 255.47 ± 41.35 a | 53.39 | |

| N500 | 113.31 ± 20.59 ab | 35.68 | 63.43 ± 11.67 a | 1.60 | 273.93 ± 19.10 a | 22.65 | 194.10 ± 29.94 ab | 16.54 | |

| N1000 | 87.73 ± 35.80 b | 5.05 | 58.09 ± 11.49 a | −6.95 | 173.08 ± 4.73 b | −22.50 | 208.26 ± 11.11 ab | 25.04 | |

| stem | CK | 111.99 ± 45.15 a | 29.70 ± 17.37 a | 147.35 ± 12.81 ab | 97.31 ± 7.08 b | ||||

| S200 | 34.79 ± 12.50 b | −68.93 | 11.91 ± 4.15 a | −59.90 | 134.77 ± 14.67 abc | −8.54 | 96.87 ± 14.64 b | −0.45 | |

| N200 | 22.84 ± 22.09 b | −79.61 | 4.11 ± 1.51 a | −86.16 | 96.25 ± 6.73 c | −34.68 | 92.77 ± 17.59 b | −4.67 | |

| N500 | 35.46 ± 6.62 b | −68.34 | 8.47 ± 3.12 a | −71.48 | 160.05 ± 19.11 a | 8.62 | 172.64 ± 26.80 a | 77.41 | |

| N1000 | 4.56 ± 1.82 b | −95.93 | 11.30 ± 2.36 a | −61.95 | 106.02 ± 3.32 bc | −28.05 | 214.93 ± 34.08 a | 120.87 | |

| leaf | CK | 40.47 ± 3.19 ab | 26.70 ± 1.72 a | 126.87 ± 6.82 a | 209.08 ± 95.86 c | ||||

| S200 | 55.45 ± 9.49 a | 37.02 | 23.56 ± 2.14 ab | −11.76 | 116.28 ± 7.55 ab | −8.35 | 184.35 ± 18.19 c | −11.83 | |

| N200 | 40.48 ± 4.09 ab | 0.02 | 20.89 ± 3.69 ab | −21.76 | 98.49 ± 0.70 bc | −22.37 | 458.34 ± 42.55 c | 119.22 | |

| N500 | 29.59 ± 5.27 b | −26.88 | 25.55 ± 3.81 a | −4.31 | 111.83 ± 11.54 abc | −11.85 | 2132.70 ± 281.07 b | 920.04 | |

| N1000 | 30.11 ± 2.36 b | −25.60 | 15.32 ± 1.39 b | −42.62 | 90.38 ± 2.01 c | −28.76 | 4639.48 ± 1105.42 a | 2119.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Q.; Qin, M.; Lang, S.; Qin, M.; Liu, L.; Li, Q.; Zhang, D.; Li, L. Concentration-Dependent Effects of Foliar ZnO Nanoparticles on Growth and Nutrient Use in Young Crabapple Plants. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121535

Zhao Q, Qin M, Lang S, Qin M, Liu L, Li Q, Zhang D, Li L. Concentration-Dependent Effects of Foliar ZnO Nanoparticles on Growth and Nutrient Use in Young Crabapple Plants. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121535

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Qi, Meimei Qin, Suixia Lang, Mengyao Qin, Lizhi Liu, Qian Li, Dehui Zhang, and Lei Li. 2025. "Concentration-Dependent Effects of Foliar ZnO Nanoparticles on Growth and Nutrient Use in Young Crabapple Plants" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121535

APA StyleZhao, Q., Qin, M., Lang, S., Qin, M., Liu, L., Li, Q., Zhang, D., & Li, L. (2025). Concentration-Dependent Effects of Foliar ZnO Nanoparticles on Growth and Nutrient Use in Young Crabapple Plants. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121535