Genetic Dissection of Petal Abscission Rate in Strawberry Unveils QTLs and Hormonal Pathways for Gray Mold Avoidance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Populations

2.2. Phenotypic Assessment of Petal Abscission Rate

2.3. BSR-Seq

2.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.5. Candidate Gene Identification

2.6. KASP Marker Development and Genotyping

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Variation in Petal Abscission Rate Across a Diverse Strawberry Germplasm Collection

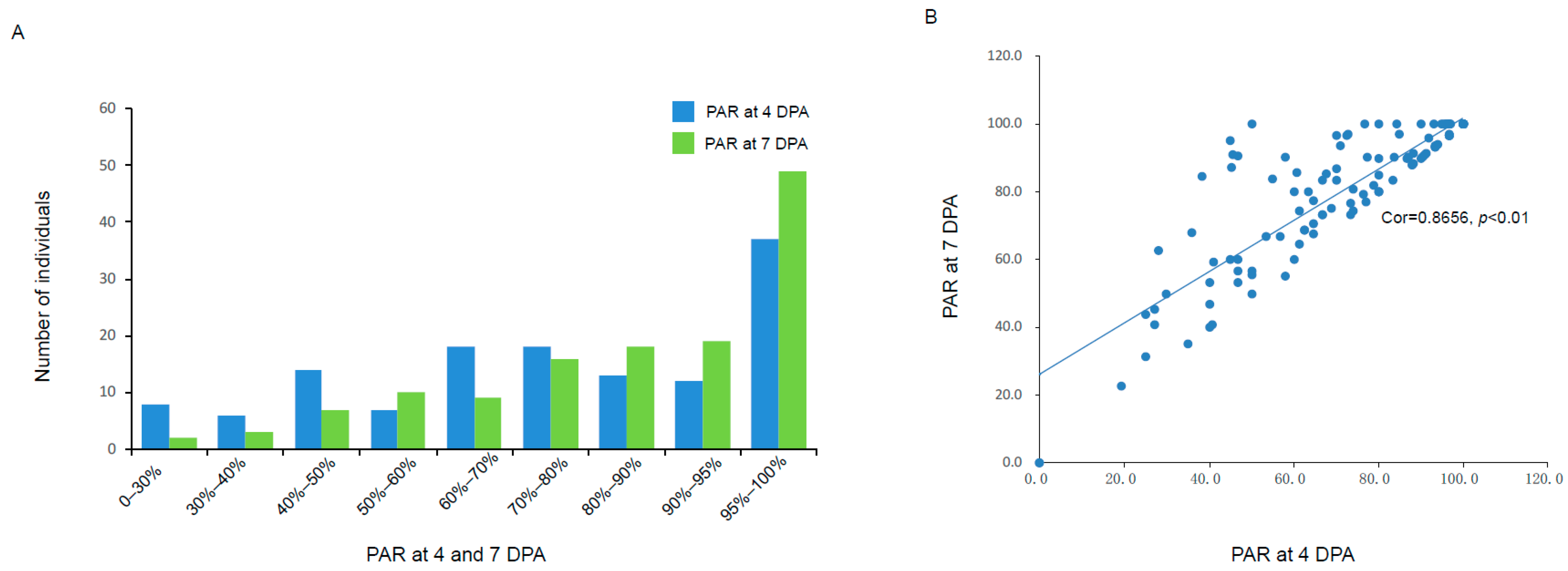

3.2. Population Construction and Petal Abscission Rates Identification

3.3. High-Quality Sequencing and SNP Discovery for BSA

3.4. BSR-Seq Analysis Integrating Euclidean Distance (ED) and ΔSNP-Index Methods

3.5. Combining Gene Expression to Identify Candidate Genes

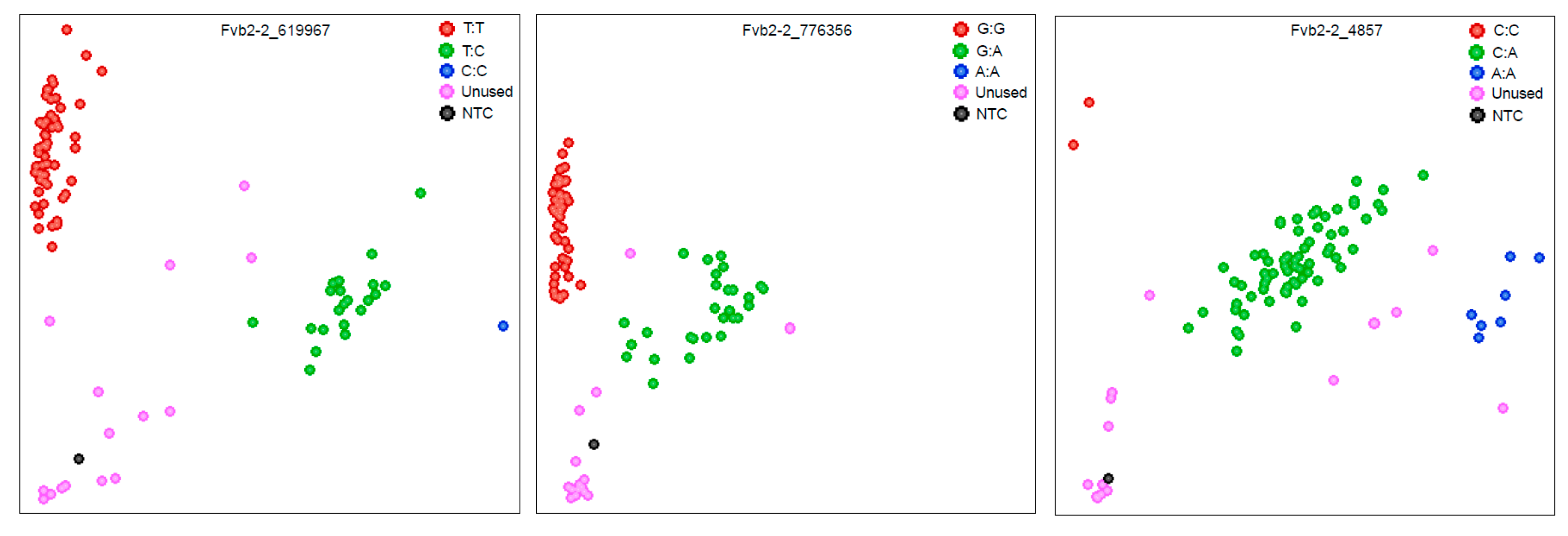

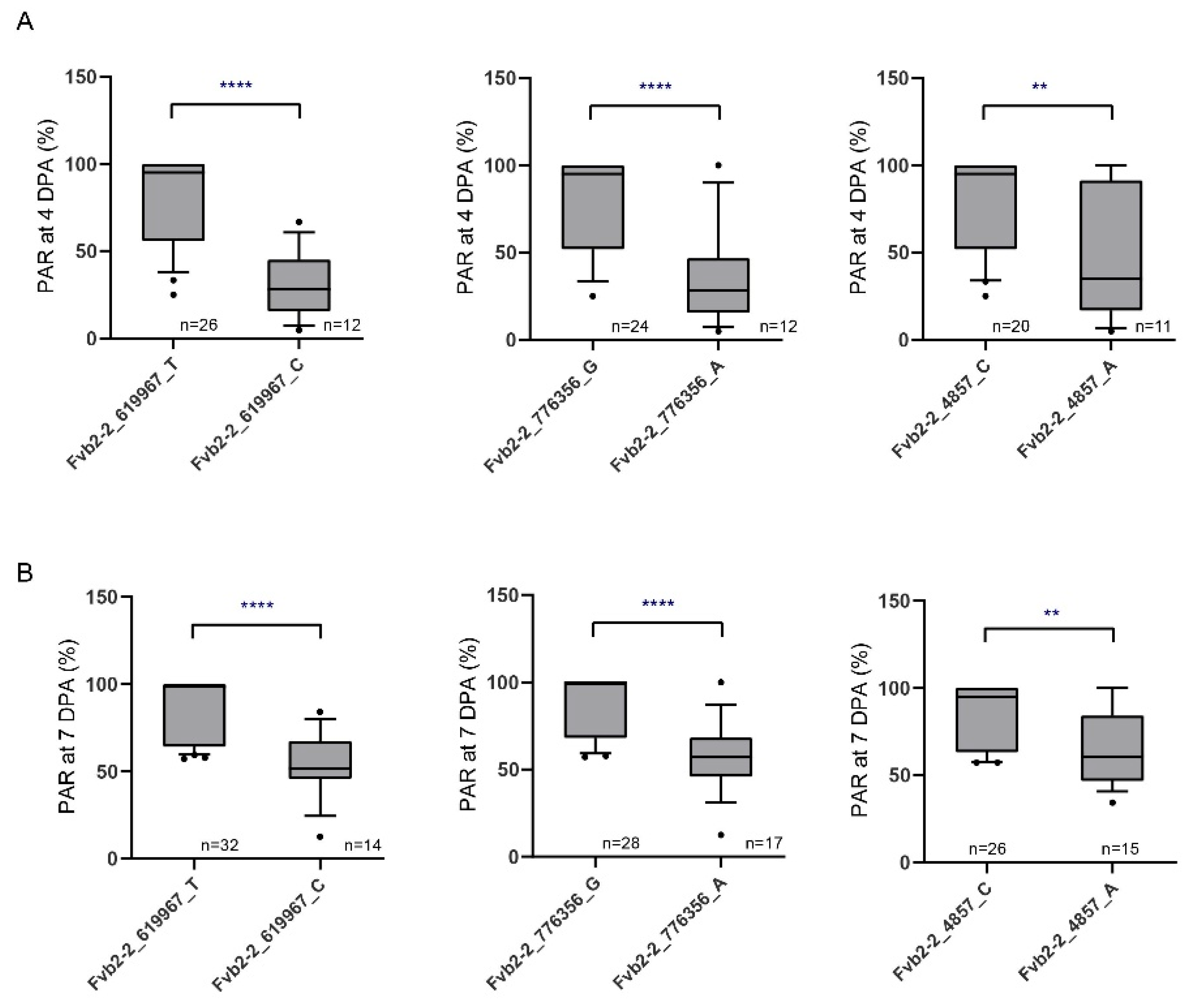

3.6. Development and Validation of KASP Markers

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Loci Controlling Plant Organ Abscission

4.2. Plant Organ Abscission Is Synchronized with Flowering

4.3. Hormonal Crosstalk in Regulating Petal Abscission

4.4. Emerging Roles of Calcium Signaling in Petal Abscission

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B. cinerea | Botrytis cinerea |

| PAR | Petal abscission rate |

| KASP | Kompetitive allele-specific PCR |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| CDPKs | Calcium-dependent protein kinases |

| QTLs | Quantitative trait loci |

| F PKM | Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| SB | Slow-abscission bulk |

| RB | Rapid-abscission bulk |

| DPA | Post-anthesis |

| IDA | Inflorescence deficient in abscission |

| HAE | HAESA |

| HSL2 | HAESA-LIKE2 |

| BOP1/2 | Blade-on-petiole1/2 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| GA | Gibberellins |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| BRs | Brassinosteroids |

| AZs | Abscission zones |

| ED | Euclidean distance |

| RIN | RNA integrity numbers |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

References

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; et al. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Tian, S. Botrytis cinerea . Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R460–R462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillinger, S.; Elad, Y. Botrytis–the Fungus, the Pathogen and Its Management in Agricultural Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Feliziani, E.; Romanazzi, G. Postharvest decay of strawberry fruit: Etiology, epidemiology, and disease management. J. Berry Res. 2016, 6, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad, Y.; Pertot, I.; Cotes Prado, A.M.; Stewart, A. Plant Hosts of Botrytis spp. In Botrytis–the Fungus, the Pathogen and Its Management in Agricultural Systems; Fillinger, S., Elad, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 413–486. [Google Scholar]

- Choquer, M.; Fournier, E.; Kunz, C.; Levis, C.; Pradier, J.M.; Simon, A.; Viaud, M. Botrytis cinerea virulence factors: New insights into a necrotrophic and polyphageous pathogen. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 277, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, K.; Liang, Y.; Mengiste, T.; Sharon, A. Killing softly: A roadmap of Botrytis cinerea pathogenicity. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, K.; Schwander, F.; Kassemeyer, H.H.; Bieler, E.; Dürrenberger, M.; Trapp, O.; Töpfer, R. Towards sensor-based phenotyping of physical barriers of grapes to improve resilience to Botrytis bunch rot. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 808365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, P.R.; McNicol, R.J.; Williamson, B. Infection of strawberry flowers by Botrytis cinerea and its relevance to grey mould development. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1986, 109, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, W.R. The infection of strawberry and raspberry fruits by Botrytis cinerea Fr. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1962, 50, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertely, J.C.; Chandler, C.K.; Xiao, C.L.; Legard, D.E. Resistance of strawberry cultivars to botrytis fruit rot. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 2002, 115, 158–161. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Li, F. Correlation between petal abscission rate and grey mould incidence in strawberry. J. Phytopathol. 2015, 163, 670–673. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Trigo, S.; Gray, J.E.; Smith, A.G. A multifaceted kinase axis regulates plant organ abscission through conserved signaling mechanisms. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, 3020–3030.E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Dotson, B.; Rey, C.; Lindsey, J.; Bleecker, A.B.; Patterson, S.E.; Binder, B.M. Transcriptional regulation of abscission zones. Plants 2019, 8, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Ma, L. Involvement of IDA-HAE Module in natural development of tomato flower abscission. Plants 2023, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meir, S.; Philosoph-Hadas, S.; Riov, J.; Kochanek, B.; Salim, S.; Shtein, I. Re-evaluation of the ethylene-dependent and -independent pathways in the regulation of floral and organ abscission. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhou, J.; Tang, J.; Li, B.; de Oliveira, M.V.V.; Chai, J.; He, P.; Shan, L. Ligand-induced receptor-like kinase complex regulates floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Ito, Y. Molecular mechanisms controlling plant organ abscission. Plant Biotechnol. 2013, 30, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patharkar, O.R.; Walker, J.C. Advances in understanding the mechanism of plant organ abscission. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, J.; Brandt, B.; Wildhagen, M.; Hohmann, U.; Hothorn, L.A.; Butenko, M.A.; Hothorn, M. Mechanistic insight into a peptide hormone signaling complex mediating floral organ abscission. ELife 2016, 5, e15075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Stenvik, G.E.; Vie, A.K.; Bones, A.M.; Pautot, V.; Butenko, M.A. Control of Organ Abscission and Other Cell Separation Processes by Evolutionary Conserved Peptide Signaling. Plants 2019, 8, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, I.W.; Li, R.; Breda, A.S.; Li, M.; Mittermeier, V.M.; Drapek, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Yu, L.Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Arabidopsis uses a molecular grounding mechanism and a biophysical circuit breaker to limit floral abscission signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2401583121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranbarger, T.J.; Tadeo, F.R.; Drakakaki, G.; Caceres, M.E.I.; Pinedo, I.T.; Lers, A.L.; Latche, A.; Pech, J.C. The PIP Peptide of INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION enhances populus leaf and Elaeis guineensis fruit abscission. Plants 2019, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Ma, L. The HD-Zip transcription factor SlHB15A regulates abscission by modulating jasmonoyl-isoleucine biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 906–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, S.; Piepho, H.P.; Stintzi, A.; Schaller, A. Peptide signaling for drought-induced tomato flower drop. Science 2020, 367, 1482–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, M.; Aït Barka, E.; Clément, C.; Vaillant-Gaveau, N.; Jacquard, C. Cross-talk between environmental stresses and plant metabolism during reproductive organ abscission. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.Z.; Zhang, X.M.; Li, W.C.; Zhang, J.B.; Li, K.T.; Liu, X.J. Molecular regulatory events of flower and fruit abscission in horticultural plants. Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estornell, L.H.; Agustí, J.; Merelo, P.; Talón, M.; Tadeo, F.R. Elucidating mechanisms underlying organ abscission. Plant Sci. 2013, 199–200, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Trigo, S.; Perez Amador, M.A.; Smith, A.G. Dissection of the IDA promoter identifies WRKY transcription factors as abscission regulators in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2934–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patharkar, O.R.; Walker, J.C. Advances in abscission signaling. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edger, P.P.; Poorten, T.J.; VanBuren, R.; Hardigan, M.A.; Colle, M.; McKain, M.R.; Smith, R.D.; Teresi, S.J.; Nelson, A.D.L.; Wai, C.M.; et al. Origin and evolution of the octoploid strawberry genome. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.J.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.T.; Demarest, B.L.; Bisgrove, B.W.; Gorsi, B.; Su, Y.C.; Yost, H.J. MMAPPR: Mutation mapping analysis pipeline for pooled RNA-seq. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, A.; Kosugi, S.; Yoshida, K.; Natsume, S.; Takagi, H.; Kanzaki, H.; Matsumura, H.; Yoshida, K.; Mitsuoka, C.; Tamiru, M.; et al. Genome sequencing reveals agronomically important loci in rice using MutMap. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, H.; Abe, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kosugi, S.; Natsume, S.; Mitsuoka, C.; Uemura, A.; Utsushi, H.; Tamiru, M.; Takuno, S.; et al. QTL-seq: Rapid mapping of quantitative trait loci in rice by whole genome resequencing of DNA from two bulked populations. Plant J. 2013, 74, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangyang, D.; Jianqi, L.; Songfeng, W.; Yunping, Z.; Fuchu, H. Integrated nr database in protein annotation system and its localization. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2006, 32, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Butenko, M.A.; Patterson, S.E.; Grini, P.E.; Stenvik, G.E.; Amundsen, S.S.; Mandal, A.; Aalen, R.B. INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION controls floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis and identifies a novel family of putative ligands in plants. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 2296–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.K.; Larue, C.T.; Chevalier, D.; Wang, H.; Jinn, T.L.; Zhang, S.; Walker, J.C. Regulation of floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 15629–15634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, J.; Tameshige, T.; Breda, A.S.; Prát, T.; Ragni, L. Floral organ abscission role of BOP1/2-TALE boundary genes. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 5182–5196. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.; Lashbrook, C.C. Stamen abscission zone transcriptome profiling reveals new candidates for abscission control: Enhanced retention of floral organs in transgenic plants overexpressing Arabidopsis ZINC FINGER PROTEIN2. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1305–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Dotson, B.; Rey, C.; Lindsey, J.; Bleecker, A.B.; Patterson, S.E.; Binder, B.M. New clothes for the jasmonic acid receptor COI1: Delayed abscission, meristem arrest and apical dominance. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Li, S. The single RRM domain-containing protein SARP1 is required for establishment of the separation zone in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1969–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.G. MSD2-mediated ROS metabolism fine-tunes the timing of floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 2209–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, K.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, T. High-density genetic map construction and identification of QTLs controlling leaf abscission trait in Poncirus trifoliata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poncet, V.; Lamy, F.; Devos, K.M.; Gale, M.D.; Sarr, A.; Robert, T. Genetic control of domestication traits in pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L., Poaceae). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 100, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazińska, P.; Wojciechowski, W.; Wilmowicz, E.; Zienkiewicz, A.; Frankowski, K.; Kopcewicz, J. De novo transcriptome profiling of flowers, flower pedicels and pods of Lupinus luteus (yellow lupine) reveals complex expression changes during organ abscission. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merelo, P.; Agustí, J.; Arbona, V.; Costa, M.L.; Estornell, L.H.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Coimbra, S.; Gómez, M.D.; Pérez-Amador, M.A.; Domingo, C.; et al. Cell wall remodeling in abscission zone cells during ethylene-promoted fruit abscission in Citrus. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Bueno, G.; De Los Reyes, P.; Chini, A.; Ferreras-Garrucho, G.; De Medina-Hernández, V.; Boter, M.; Solano, R.; Valverde, F. Regulation of floral senescence in Arabidopsis by coordinated action of CONSTANS and jasmonate signaling. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1467–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C.; Nagpal, P.; Young, J.; Hagen, G.; Guilfoyle, T.; Reed, J. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR1 and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 regulate senescence and floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 2005, 132, 4563–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xue, Y.; Sarwar, R.; Wei, S.; Geng, R.; Zhang, Y.; Mu, J.; Tan, X. The BnaBPs gene regulates flowering time and leaf angle in Brassica napus. Plant Direct. 2024, 8, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardon, K.; Hohl, M.; Graff, L.; Pfannstiel, J.; Schulze, W.; Stintzi, A.; Schaller, A. Precursor processing for plant peptide hormone maturation by subtilisin-like serine proteinases. Science 2016, 354, 1594–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventimilla, D.; Velázquez, K.; Ruiz-Ruiz, S.; Terol, J.; Perez-Amador, M.; Vives, M.; Guerri, J.; Talón, M.; Tadeo, F. IDA (INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION)-like peptides and HAE (HAESA)-like receptors regulate corolla abscission in Nicotiana benthamiana flowers. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chersicola, M.; Kladnik, A.; Hrženjak, A.; Kocjan, D.; Fellner, M. 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase induction in tomato flower pedicel phloem and abscission related processes are differentially sensitive to ethylene. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.M. Ethylene and Abscission. Physiol. Plant. 1997, 100, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Lu, J.; Jiang, C.; Fei, Z.; Jiang, C.-Z.; Ma, C.; Gao, J. Rosa hybrida RhERF1 and RhERF4 mediate ethylene- and auxin-regulated petal abscission by influencing pectin degradation. Plant J. 2019, 99, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, M.; Mukherjee, A.; Datta, S.; Datta, S. Role of EIN2-mediated ethylene signaling in regulating petal senescence, abscission, reproductive development, and hormonal crosstalk in tobacco. Plant Sci. 2023, 336, 111847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; He, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lalun, V.O.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Huang, Y.; et al. The transcriptional control of LcIDL1-LcHSL2 complex by LcARF5 integrates auxin and ethylene signaling for litchi fruitlet abscission. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butenko, M.A.; Stenvik, G.E.; Alm, V.; Saether, B.; Patterson, S.E.; Aalen, R.B. Ethylene-dependent and -independent pathways controlling floral abscission are revealed to converge using promoter::reporter gene constructs in the IDA abscission mutant. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 4187–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, M.M.; González-Carranza, Z.H.; Azam-Ali, S.; Tang, S.; Shahid, A.A.; Roberts, J.A. The manipulation of auxin in the abscission zone cells of Arabidopsis flowers reveals that indoleacetic acid signaling is a prerequisite for organ shedding. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Qin, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M. Deciphering the auxin-ethylene crosstalk in petal abscission through auxin influx carrier IpAUX1 of Itoh peony ‘Bartzella’. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 216, 112980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, W.; Ma, Z.; Cui, M.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Li, S. Auxin efflux carrier PsPIN4 identified through genome-wide analysis as vital factor of petal abscission. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1427826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y. A KNOTTED1-LIKE HOMEOBOX PROTEIN1–interacting transcription factor SlGATA6 maintains the auxin-response gradient to inhibit abscission. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Ma, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y. SlBEL11 regulates flavonoid biosynthesis, thus fine-tuning auxin efflux to prevent premature fruit drop in tomato. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1571–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Lu, J.; Aiwaili, P.; Fei, Z.; Jiang, C.-Z.; Ma, C.; Gao, J. Auxin regulates sucrose transport to repress petal abscission in Rose (Rosa hybrida). Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3485–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yuan, Y.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; He, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, M. Brassinosteroids suppress ethylene-induced fruitlet abscission through LcBZR1/2-mediated transcriptional repression of LcACS1/4 and LcACO2/3 in litchi. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmowicz, E.; Frankowski, K.; Kucko, A.; Kesy, J.; Kopcewicz, J. The influence of abscisic acid on the ethylene biosynthesis pathway in the functioning of the flower abscission zone in Lupinus luteus. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 204, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kućko, A.; Wilmowicz, E.; Alché, J.D.D.; de Dios, A.; Kesy, J.; Kopcewicz, J. Abscisic acid- and ethylene-induced abscission of yellow lupine flowers is mediated by jasmonates. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 290, 154119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, R.; Rock, C. Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis and Response. Arab. Book 2002, 1, e0058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulfishan, M.; Jahan, A.; Bhat, T.A.; Sahab, D. Plant Senescence and Organ Abscission. In Senescence Signalling and Control in Plants; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Cádenas, A.; Mehouachi, J.; Tadeo, F.R.; Primo-Millo, E.; Talon, M. Hormonal regulation of fruitlet abscission induced by carbohydrate shortage in Citrus. Planta 2000, 210, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushiro, T.; Okamoto, M.; Nakabayashi, K.; Yamagishi, K.; Kitamura, S.; Asami, T.; Hirai, N.; Koshiba, T.; Kamiya, Y.; Nambara, E. The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 CYP707A encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylases: Key enzymes in ABA catabolism. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Kuwahara, A.; Seo, M.; Kushiro, T.; Asami, T.; Hirai, N.; Kamiya, Y.; Koshiba, T.; Nambara, E. CYP707A1 and CYP707A2, which encode abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylases, are indispensable for proper control of seed dormancy and germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalun, V.O.; Breiden, M.; Stenvik, G.-E.; Butenko, M.A.; Aalen, R.B. A dual function of the ida peptide in regulating cell separation and modulating plant immunity at the molecular level. Elife 2019, 8, e44589. [Google Scholar]

- Aldon, D.; Mbengue, M.; Mazars, C.; Galaud, J.-P. Calcium signalling in plant biotic interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.-J.; Wei, F.-J.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.-J.; Ratnasekera, D.; Liu, W.-X.; Wu, W.-H. Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK10 functions in Abscisic Acid- and Ca2+-mediated stomatal regulation in response to drought stress. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1232–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishka, M.R.; Brown, E.; Rosenberg, A.; Romanowsky, S.M.; Davis, J.A.; Choi, W.G.; Harper, J.F. Arabidopsis Ca2+-ATPases 1, 2, and 7 in the endoplasmic reticulum contribute to growth and pollen fitness. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 1856–1872. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, R.F.; Doherty, M.L.; López-Marqués, R.L.; Weimar, T.; Dupree, P.; Palmgren, M.G.; Pittman, J.K.; Williams, L.E. ECA3, a Golgi-localized P2A-type ATPase, plays a crucial role in manganese nutrition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chanroj, S.; Wu, Z.; Romanowsky, S.M.; Harper, J.F.; Sze, H. A distinct endosomal Ca2+/Mn2+ pump affects root growth through the secretory process. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1675–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Total Reads | Clean Reads | Clean Bases (Gb) | Q30 (%) | GC (%) | Mapped Reads | Uniq Mapped Reads | SNPs Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benihoppe | 46,435,352 | 23,217,676 | 6.91 | 94.51 | 46.58 | 38,693,949 | 29,996,254 | 489,835 |

| Sweet Charlie | 51,735,390 | 25,867,695 | 7.70 | 94.09 | 46.79 | 43,689,709 | 34,029,307 | 497,255 |

| RB | 86,388,970 | 43,194,485 | 12.89 | 94.68 | 46.64 | 72,298,800 | 56,113,460 | 560,969 |

| SB | 94,267,396 | 47,133,698 | 14.03 | 94.60 | 46.80 | 79,015,592 | 60,926,844 | 570,278 |

| Chromosome | Start | End | Size (Mb) | Gene Number | Hormone-Related Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fvb2-2 | 0 | 2,010,000 | 2.01 | 386 | ABF2, PYL2, CYCD3-3, HAB1, GID2.1, GID2.2 |

| Fvb4-4 | 140,000 | 640,000 | 0.5 | 83 | |

| Fvb6-3 | 39,160,000 | 40,220,000 | 1.06 | 191 | EIN4, ERF1B |

| Fvb6-3 | 40,360,000 | 40,400,000 | 0.04 | 6 | |

| Fvb6-3 | 40,660,000 | 40,680,000 | 0.02 | 6 | |

| Total | - | - | - | 672 |

| Location | Gene | Pathway | Codon Change | Effect of Mutation | Correlation with PAR at 4 DPA | R2 for PAR at 4 DPA | Correlation with PAR at 7 DPA | R2 for PAR at 7 DPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fvb2-2_4857 | CYP707A7 | ABA | Tgt/Ggt | Non Synonymous | −0.484 * | 0.271 | −0.398 * | 0.154 |

| Fvb2-2_67062 | ABF2 | ABA | Aaa/Gaa | Non Synonymous | 0.221 | 0.225 | ||

| Fvb2-2_619967 | ACA1 | Calcium Signaling | aGt/aAt | Non Synonymous | −0.703 ** | 0.517 | −0.649 ** | 0.429 |

| Fvb2-2_776356 | ECA3 | Calcium Signaling | cAg/cGg | Non Synonymous | −0.599 ** | 0.386 | −0.609 ** | 0.392 |

| Fvb2-2_892961 | ANT | Ethylene | Gtt/Ctt | Non Synonymous | - | - | ||

| Fvb2-2_1068552 | ELF3 | Flowering | cCt/cTt | Non Synonymous | - | - | ||

| Fvb2-2_1208392 | NDL2 | Auxin | Cgt/Tgt | Non Synonymous | −0.169 | −0.047 | ||

| Fvb2-2_1263512 | RTE1 | Ethylene | Aaa/Gaa | Non Synonymous | 0.264 | 0.327 | ||

| Fvb2-2_1428328 | LOG8 | Cytokinin | taT/taC | Synonymous | 0.09 | 0.128 | ||

| Fvb2-2_1725514 | CKX7 | Cytokinin | Tcc/Acc | Non Synonymous | −0.05 | 0.002 | ||

| Fvb2-2_1835395 | FPF1 | Auxin | Gaa/Aaa | Non Synonymous | - | - | ||

| Fvb4-4_400296 | HUA2 | Flowering | cAc/cGc | Non Synonymous | −0.123 | −0.22 | ||

| Fvb6-3_39197804 | AGL62 | Flowering | gAt/gigot | Non Synonymous | - | - | ||

| Fvb6-3_39578228 | AMT1-2.2 | Ammonium transporter | gAc/gCc | Non Synonymous | −0.168 | −0.181 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, G.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, D.; Han, Y. Genetic Dissection of Petal Abscission Rate in Strawberry Unveils QTLs and Hormonal Pathways for Gray Mold Avoidance. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121525

Xiao G, Zeng X, Zhang D, Han Y. Genetic Dissection of Petal Abscission Rate in Strawberry Unveils QTLs and Hormonal Pathways for Gray Mold Avoidance. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121525

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Guilin, Xiangguo Zeng, Dongmei Zhang, and Yongchao Han. 2025. "Genetic Dissection of Petal Abscission Rate in Strawberry Unveils QTLs and Hormonal Pathways for Gray Mold Avoidance" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121525

APA StyleXiao, G., Zeng, X., Zhang, D., & Han, Y. (2025). Genetic Dissection of Petal Abscission Rate in Strawberry Unveils QTLs and Hormonal Pathways for Gray Mold Avoidance. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121525