Vine Water Status Modulates the Physiological Response to Different Apical Leaf Removal Treatments in Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.) Grapevines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Conditions

2.2. Irrigation Regimes and Leaf Removal Treatments

2.3. Canopy Measurement and Yield Estimation

2.4. Leaf Gas Exchange and Leaf Total Soluble Solids

2.5. Vine Water Status and Transpiration

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Climatic Conditions and Vine Phenology

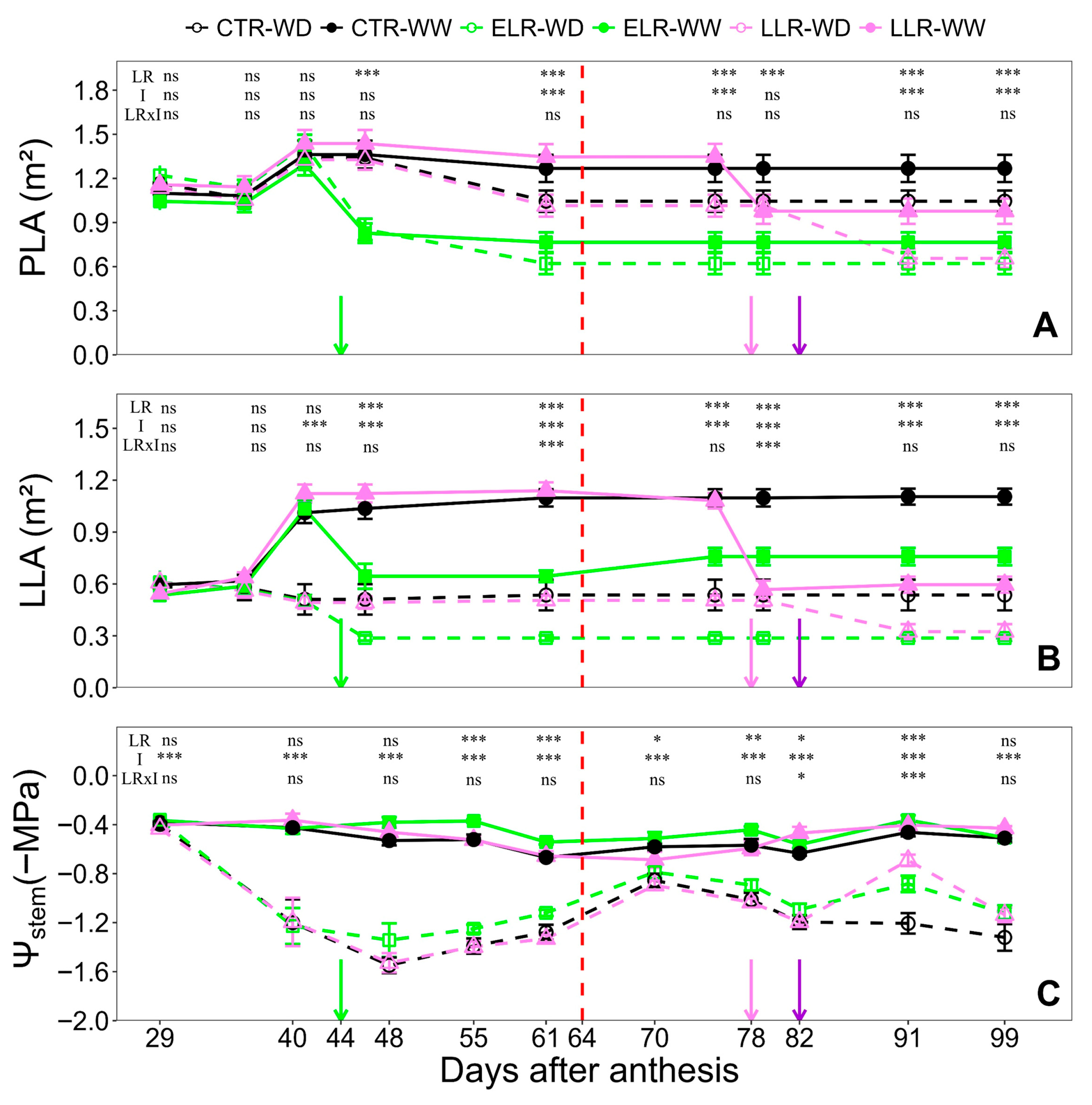

3.2. Vine Vegetative Characteristics and Yield Parameters

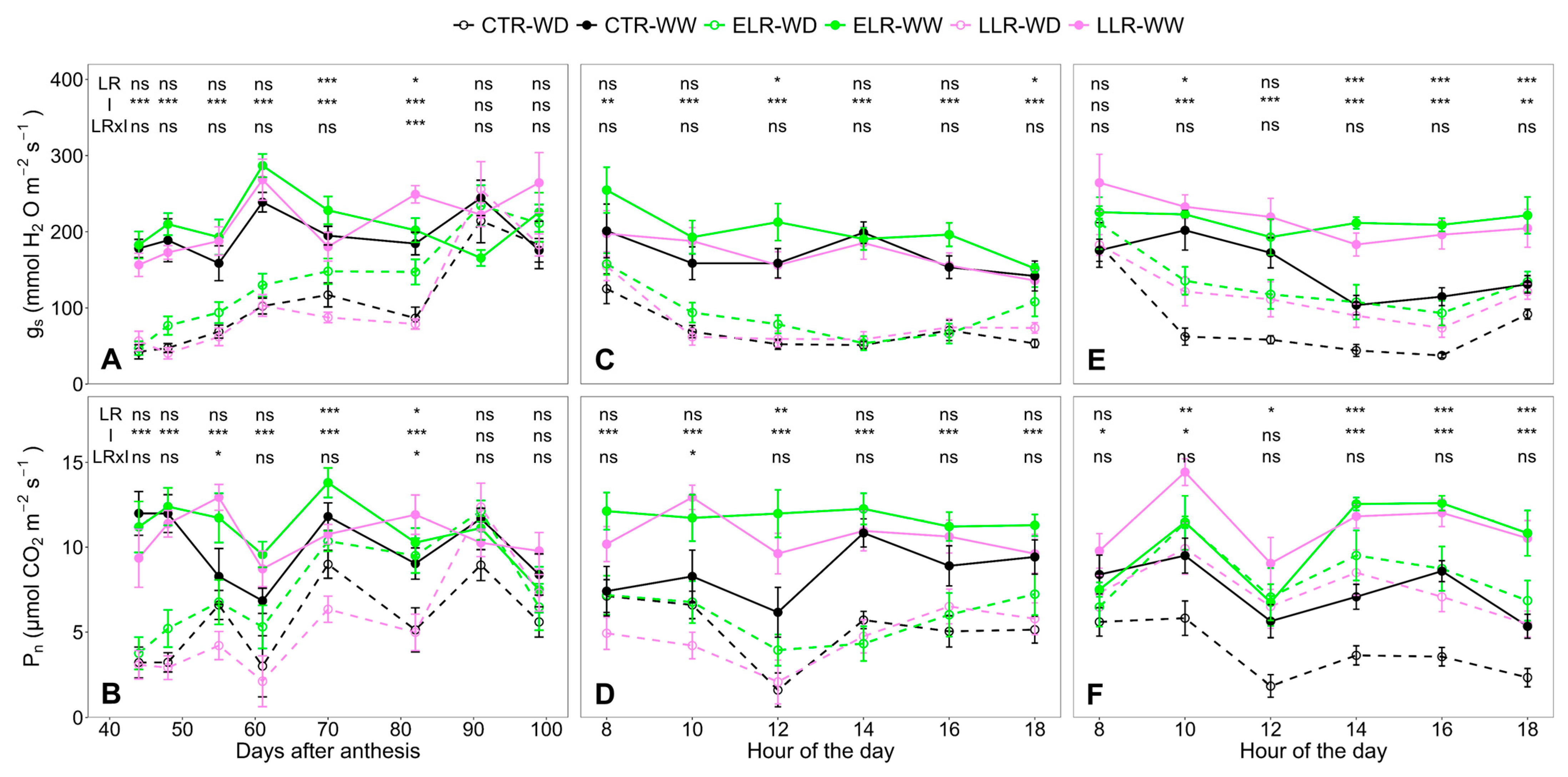

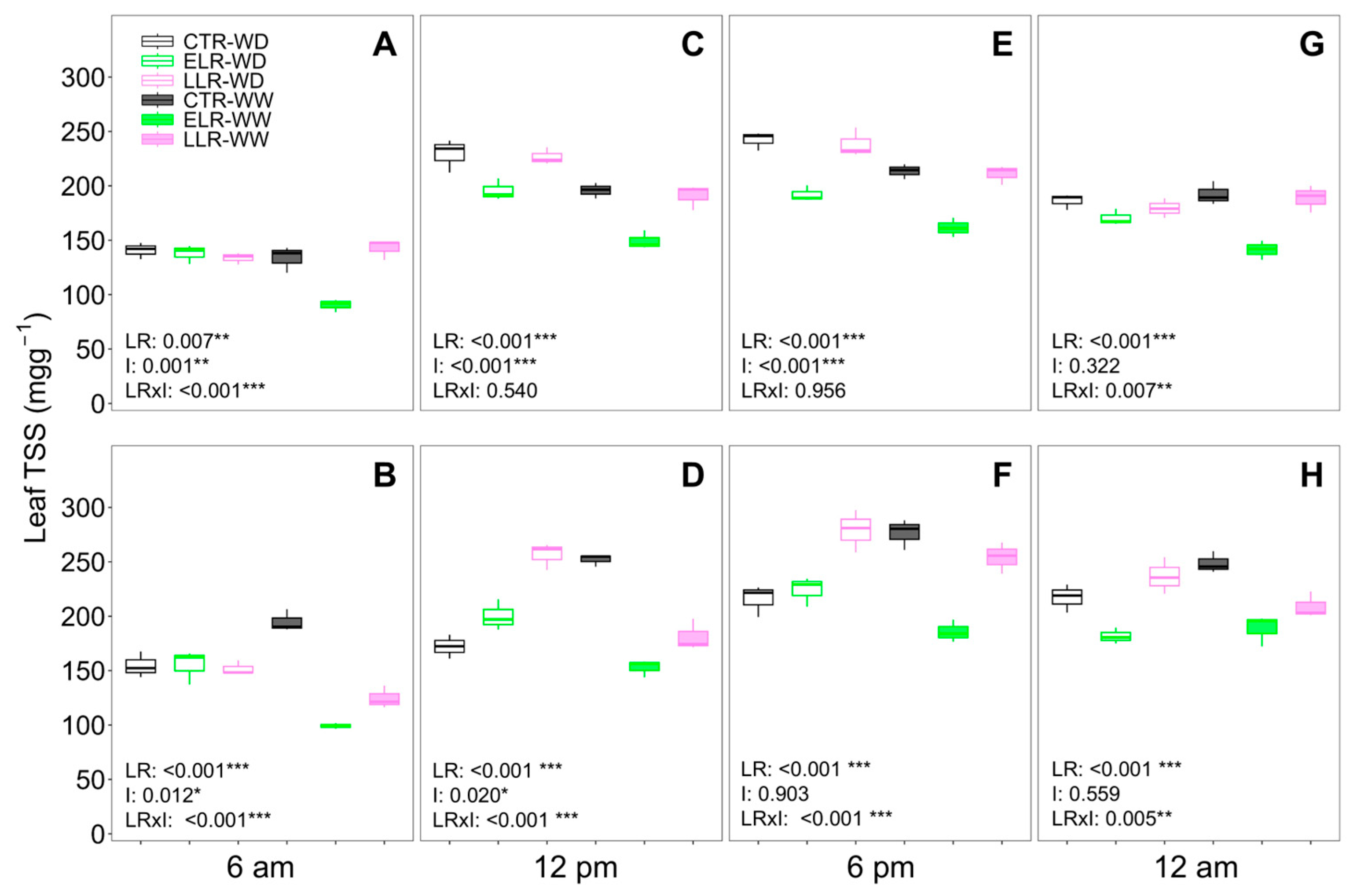

3.3. Leaf Gas Exchange and Daily Leaf TSS Evolution

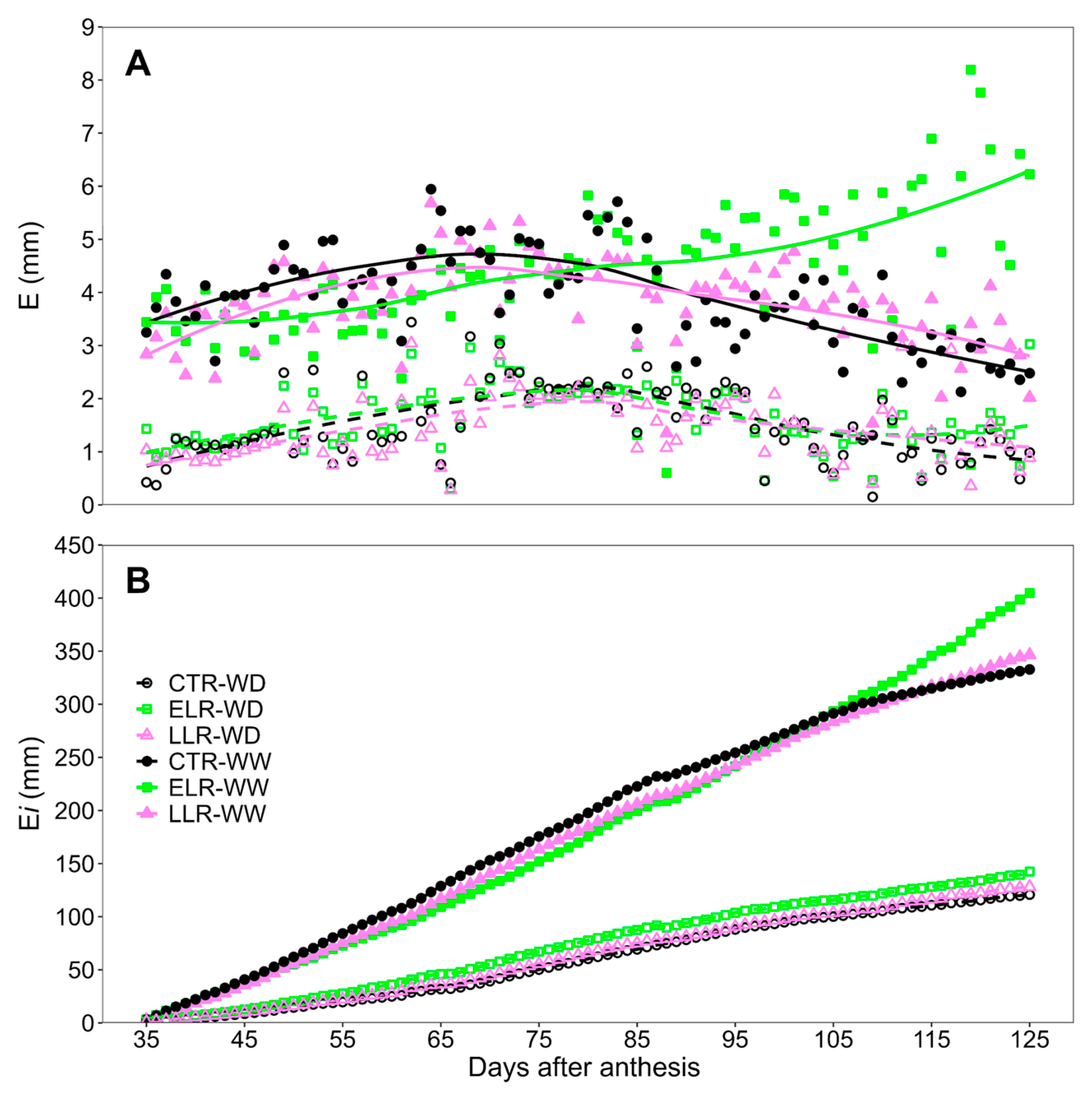

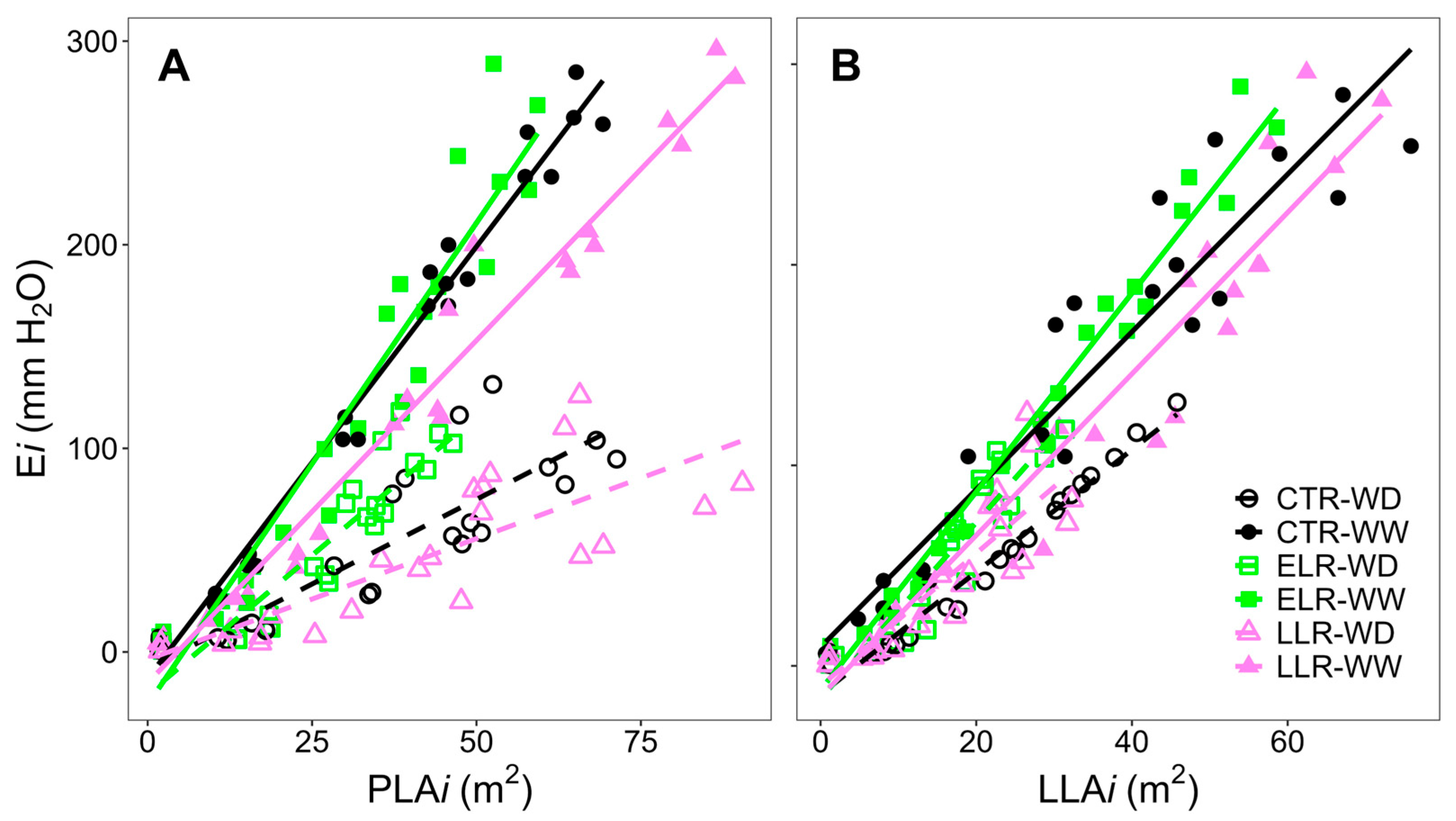

3.4. Vine Water Relations

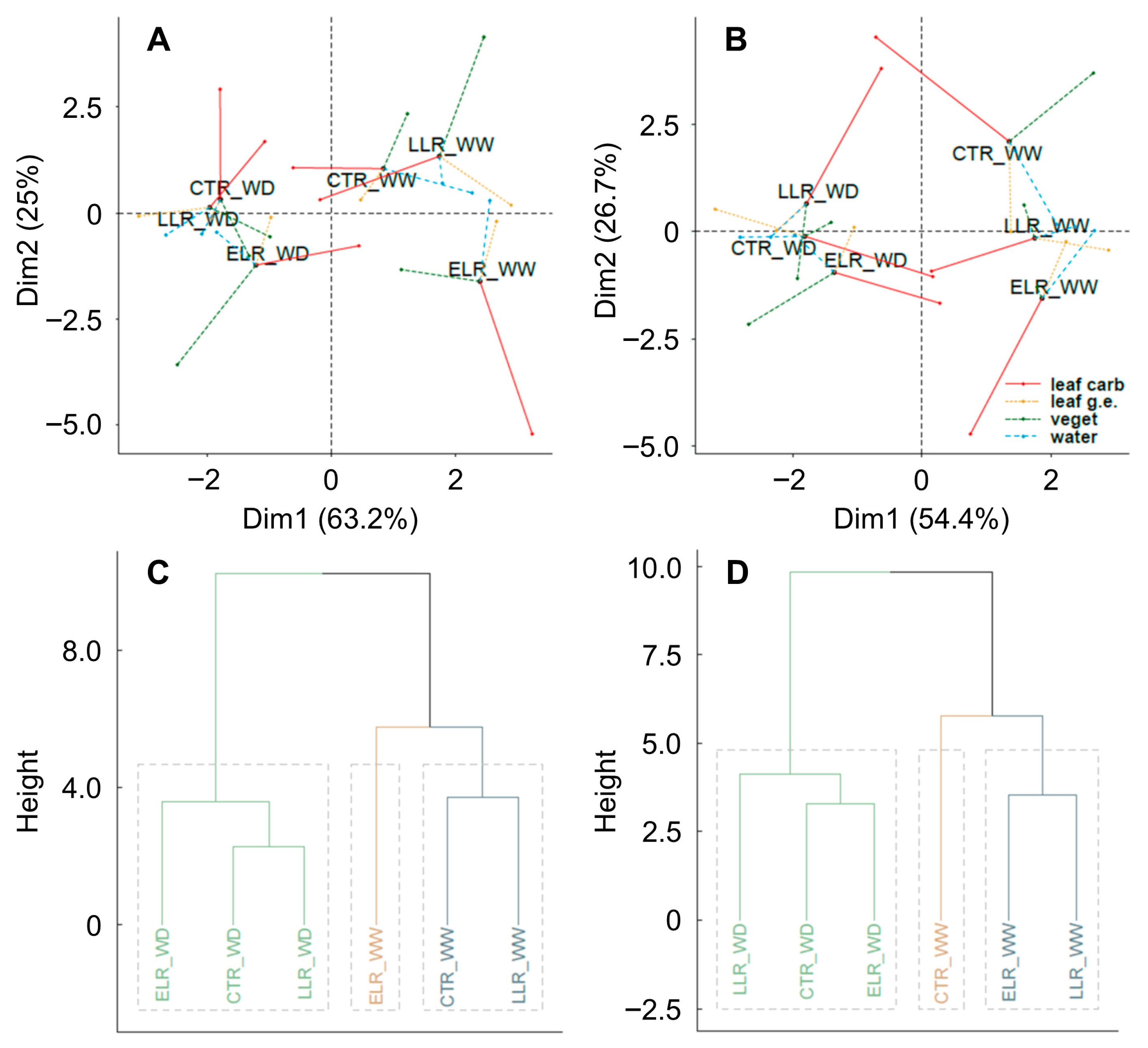

3.5. Multiple-Factor Analysis (MFA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keller, M. The Science of Grapevines, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Press: Burlington, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.W.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K.; Blanco, G.; et al. IPCC: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douville, H.; Raghavan, K.; Renwick, J.; Allan, R.P.; Arias, P.A.; Barlow, M.; Cerezo-Mota, R.; Cherchi, A.; Gan, T.; Gergis, J. Water Cycle Changes; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Chapter08.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Martínez-Lüscher, J.; Matus, J.T.; Gomès, E.; Pascual, I. Toward understanding grapevine responses to climate change: A multi-stress and holistic approach. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 76, 2949–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadras, V.O.; Monzon, J.P. Modelled wheat phenology captures rising temperature trends: Shortened time to flowering and maturity in Australia and Argentina. Field Crops Res. 2006, 99, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, L.; Whetton, P.; Bhend, J.; Darbyshire, R.; Briggs, P.R.; Barlow, E.W.R. Earlier wine-grape ripening driven by climatic warming and drying and management practices. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Duchêne, E.; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Barbeau, G.; de Rességuier, L.; Lacombe, T.; Parker, A.K.; Saurin, N.; van Leeuwen, C. Grapevine phenology in France: From past observations to future evolutions in the context of climate change. OENO One 2017, 51, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leolini, L.; Moriondo, M.; Fila, G.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; Ferrise, R.; Bindi, M. Late spring frost impacts on future grapevine distribution in Europe. Field Crops Res. 2018, 222, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faralli, M.; Mallucci, S.; Bignardi, A.; Varner, M.; Bertamini, M. Four decades in the vineyard: The impact of climate change on grapevine phenology and wine quality in northern Italy. OENO One 2024, 58, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Destrac-Irvine, A. Modified grape composition under climate change conditions requires adaptations in the vineyard. OENO One 2017, 51, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriedemann, P.E. Photosynthesis in vine leaves as a function of light intensity, temperature and leaf age. Vitis 1968, 7, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, D.H.; Weedon, M.M. Modelling photosynthetic responses to temperature of grapevine (Vitis vinifera cv. Semillon) leaves on vines grown in a hot climate. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, H.; Escalona, J.M.; Cifre, J.; Bota, J.; Flexas, J. A ten-year study on the physiology of two Spanish grapevine cultivars under field conditions: Effects of water availability from leaf photosynthesis to grape yield and quality. Funct. Plant Biol. 2003, 30, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, B.; Hao, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, Y. Effects of short-term heat stress on PSII and subsequent recovery for senescent leaves of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Red Globe. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 2683–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Escalona, J.M.; Medrano, H. Water stress induces different levels of photosynthesis and electron transport rate regulation in grapevines. Plant Cell Environ. 1999, 22, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovisolo, C.; Perrone, I.; Carra, A.; Ferrandino, A.; Flexas, J.; Medrano, H.; Schubert, A. Drought-induced changes in development and function of grapevine (Vitis spp.) organs and in their hydraulic and non-hydraulic interactions at the whole-plant level: A physiological and molecular update. Funct. Plant Biol. 2010, 37, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusig, D.; Tombesi, S. Abscisic Acid Mediates Drought and Salt Stress Responses in Vitis vinifera—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez del Campo, M.; Ruiz, C.; Lissarrague, J.R. Effect of Water Stress on Leaf Area Development, Photosynthesis, and Productivity in Chardonnay and Airén Grapevines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, H.; Andary, C.; Creaba, E.; Carbonneau, A.; Deloire, A. Influence of pre-and postveraison water deficit on synthesis and concentration of skin phenolic compounds during berry growth of Vitis vinifera var. Shiraz. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Buesa, I.; Pérez, D.; Castel, J.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Castel, J.R. Effect of deficit irrigation on vine performance and grape composition of Vitis vinífera L. cv. Muscat of Alexandria. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoi, S.; Wong, D.C.J.; Degu, A.; Herrera, J.C.; Bucchetti, B.; Peterlunger, E.; Fait, A.; Mattivi, F.; Castellarin, S.D. Multi-Omics and integrated network analyses reveal new insights into the systems relationships between metabolites, structural genes, and transcriptional regulators in developing grape berries (Vitis vinifera L.) exposed to water deficit. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palai, G.; Caruso, G.; Gucci, R.; D’Onofrio, C. Water deficit before veraison is crucial in regulating berry VOCs concentration in Sangiovese grapevines. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1117572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliotti, A.; Tombesi, S.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S. Changes in vineyard establishment and canopy management urged by earlier climate-related grape ripening: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 178, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Johnson, E.A.; Martin, Y.E. Optimization of leaf morphology in relation to leaf water status: A theory. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 1510–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devin, S.R.; Prudencio, Á.S.; Mahdavi, S.M.E.; Rubio, M.; Martínez-García, P.J.; Martínez-Gómez, P. Orchard Management and Incorporation of Biochemical and Molecular Strategies for Improving Drought Tolerance in Fruit Tree Crops. Plants 2023, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santesteban, L.G.; Miranda, C.; Urrestarazu, J.; Loidi, M.; Royo, J.B. Severe trimming and enhanced competition of laterals as a tool to delay ripening in Tempranillo vineyards under semiarid conditions. OENO One 2017, 51, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, S.; Bossuat, C.; Nicolas, S.; Rega, M.; Chaugny, A.; Noret, L.; Gavrilescu, C.; Santoni, A.; Mathieu, O.; Alexandre, H.; et al. Consequences of apical leaf removal on grapevine water status, heat damage, yield and grape ripening on Pinot n. and Chardonnay. In IVES Conference Series, Proceedings of the 22nd GiESCO International Meeting, Ithaca, NY, USA, 7 July 2023; GiESCO: Montpellier, France, 2023. Available online: https://ives-openscience.eu/34739/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Buesa, I.; Caccavello, G.; Basile, B.; Merli, M.C.; Poni, S.; Chirivella, C.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Delaying berry ripening of Bobal and Tempranillo grapevines by late leaf removal in a semi-arid and temperate-warm climate under different water regimes. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2019, 25, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotti, L.; Partida, G.; Laroche-Pinel, E.; Lanari, V.; Pedroza, M.; Brillante, L. Late-season source limitation practices to cope with climate change: Delaying ripening and improving colour of Cabernet-Sauvignon grapes and wine in a hot and arid climate. OENO One 2025, 59, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegher, M.; Niedrist, G.; Tagliavini, M.; Asensio, D.; Giuliani, N.; Andreotti, C. Impact of leaf removal on recovery of young grapevines under heatwave conditions: A study in an ecotron environment. OENO One 2025, 59, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.H.; Eichhorn, K.W.; Bleiholder, H.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Weber, E. Phenological growth stages of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. vinifera)—Codes and descriptions according to the extended BBCH scale. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1995, 1, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompeiano, A.; Vita, F.; Alpi, A.; Guglielminetti, L. Arundo donax L. response to low oxygen stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 111, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersony, J.T.; Hochberg, U.; Rockwell, F.E.; Park, M.; Gauthier, P.P.G.; Holbrook, N.M. Leaf Carbon Export and Nonstructural Carbohydrates in Relation to Diurnal Water Dynamics in Mature Oak Trees. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackel, K. A plant-based approach to deficit irrigation in trees and vines. HortScience 2011, 46, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaníčková, L.; Pompeiano, A.; Maděra, P.; Massad, T.J.; Vahalík, P. Terpenoid profiles of resin in the genus Dracaena are species specific. Phytochemistry 2020, 170, 112197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palliotti, A.; Panara, F.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Sabbatini, P.; Howell, G.S.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S. Influence of mechanical postveraison leaf removal apical to the cluster zone on delay of fruit ripening in Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.) grapevines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2013, 19, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.; Bucchetti, B.; Sabbatini, P.; Comuzzo, P.; Zulini, L.; Vecchione, A.; Peterlunger, E.; Castellarin, S.D. Effect of water deficit and severe shoot trimming on the composition of Vitis vinifera L. Merlot grapes and wines: Water deficit and severe trimming effect on Merlot. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2015, 21, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-del-Campo, M.; Ruiz, C.; Sotés, V.; Lissarrague, J.R. Water consumption in grapevines: Influence of leaf area and irrigation. Acta Hortic. 1999, 493, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.E.; Ayars, J.E. Grapevine water use and the crop coefficient are linear functions of the shaded area measured beneath the canopy. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2005, 132, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Romero, P.; Gohil, H.; Smithyman, R.P.; Riley, W.R.; Casassa, L.F.; Harbertson, J.F. Deficit irrigation alters grapevine growth, physiology, and fruit microclimate. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 67, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, T.N. How do stomata respond to water status? New Phytol. 2019, 224, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Zarrouk, O.; Francisco, R.; Costa, J.M.; Santos, T.; Regalado, A.P.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Lopes, C.M. Grapevine under deficit irrigation: Hints from physiological and molecular data. Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palai, G.; Gucci, R.; Caruso, G.; D’Onofrio, C. Physiological changes induced by either pre- or post-veraison deficit irrigation in ‘Merlot’ vines grafted on two different rootstocks. Vitis 2021, 60, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, I.; Pagliarani, C.; Lovisolo, C.; Chitarra, W.; Roman, F.; Schubert, A. Recovery from water stress affects grape leaf petiole transcriptome. Planta 2012, 235, 1383–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtai, W.; Asensio, D.; Kadison, A.E.; Schwarz, M.; Raifer, B.; Andreotti, C.; Hammerle, A.; Zanotelli, D.; Haas, F.; Niedrist, G.; et al. Soil water availability modulates the response of grapevine leaf gas exchange and PSII traits to a simulated heat wave. Plant Soil 2024, 501, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, P.R.; Trought, M.C.T.; Howell, G.S.; Buchan, G.D. The effect of leaf removal and canopy height on whole-vine gas exchange and fruit development of Vitis vinifera L. Sauvignon Blanc. Funct. Plant Biol. 2003, 30, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Gatti, M.; Bernizzoni, F.; Civardi, S.; Bobeica, N.; Magnanini, E.; Palliotti, A. Late leaf removal aimed at delaying ripening in cv. Sangiovese: Physiological assessment and vine performance. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2013, 19, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Correia, C.; Gonçalves, B.; Bacelar, E.A.; Torres-Pereira, J.M. Leaf Gas Exchange and Water Relations of Grapevines Grown in Three Different Conditions. Photosynthetica 2004, 42, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Lakso, A.N. Effects of light interception and canopy orientation on grapevine water status and canopy gas exchange. Acta Hortic. 2011, 889, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.; Sperling, O.; Rachmilevitch, S.; Hochberg, U. Carbon Dynamics Under Drought and Recovery in Grapevine’s Leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 3379–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shrestha, P.M.; Biondi, M.; Bondada, B.R. Sugar demand of ripening grape berries leads to recycling of surplus phloem water via the xylem. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Pérez, D.; Risco, D.; Yeves, A.; Castel, J.R. Yield components and grape composition responses to seasonal water deficits in Tempranillo grapevines. Irrig. Sci. 2012, 30, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Muñoz, R.G.; Fernández-Fernández, J.I.; del Amor, F.M.; Martínez-Cutillas, A.; García-García, J. Improvement of yield and grape and wine composition in field-grown Monastrell grapevines by partial root zone irrigation, in comparison with regulated deficit irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 149, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Intrigliolo Molina, D.S.; Vivaldi, G.A.; García-Esparza, M.J.; Lizama, V.; Álvarez, I. Effects of the irrigation regimes on grapevine cv. Bobal in a Mediterranean climate: I. Water relations, vine performance and grape composition. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 248, 106772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palai, G.; Caruso, G.; Gucci, R.; D’Onofrio, C. Deficit irrigation differently affects aroma composition in berries of Vitis vinifera L. (cvs Sangiovese and Merlot) grafted on two rootstocks. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2022, 28, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Budbreak (BBCH 09) | Flowering (BBCH 65) | Veraison (BBCH 81) | Harvest (BBCH 89) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTR-WD | 87 | 143 | 217 | 255 |

| CTR-WW | 87 | 143 | 207 | 255 |

| ELR-WD | 87 | 143 | 222 | 268 |

| ELR-WW | 87 | 143 | 213 | 260 |

| LLR-WD | 87 | 143 | 217 | 260 |

| LLR-WW | 87 | 143 | 207 | 268 |

| Treatment | Shoots (n) | Clusters (n) | Real Fertility | Fruit Yield (kg/vine) | Average Cluster Weight (g) | Average Berry Weight (g) | Pruning Weight (g/vine) | Ravaz Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTR-WD | 8.4 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 b | 236 ± 14 b | 1.83 ± 0.07 b | 294 ± 14 b | 7.0 ± 0.7 |

| CTR-WW | 8.4 ± 0.4 | 8.3 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.3 a | 366 ± 33 a | 2.21 ± 0.08 a | 468 ± 33 a | 6.8 ± 0.9 |

| ELR-WD | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 8.7± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 b | 264 ± 18 b | 1.81 ± 0.06 b | 299 ± 38 b | 9.0 ± 1.8 |

| ELR-WW | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.4 a | 333 ± 36 a | 2.31 ± 0.07 a | 385 ± 50 a | 8.9 ± 1.3 |

| LLR-WD | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 b | 376 ± 26 b | 1.86 ± 0.05 b | 338 ± 23 b | 6.7 ± 0.5 |

| LLR-WW | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.4 a | 292 ± 33 a | 2.21 ± 0.04 a | 416 ± 55 a | 9.2 ± 1.3 |

| LR | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| I | ns | ns | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ns |

| LRxI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Factor | DF | Sum of Squares | F Ratio | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAi | 1 | 769,236.68 | 2033.297 | <0.001 |

| TypeLAi | 1 | 52,126.35 | 137.7838 | <0.001 |

| Treatment | 5 | 147,039.04 | 77.7326 | <0.001 |

| TypeLAi*LAi | 1 | 14,667.23 | 38.7694 | <0.001 |

| Treatment*TypeLAi | 5 | 12,302.42 | 6.5037 | <0.001 |

| Treatment*LAi | 5 | 62,423.79 | 33.0005 | <0.001 |

| TypeLAi*LAi* Treatment | 5 | 13,423.56 | 7.0964 | <0.001 |

| TypeLAi | Treatment | Slope | SE | t.ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLAi | CTR-WD | 3.05 | 0.302 | 10.078 | <0.001 |

| PLAi | CTR-WD | 1.66 | 0.185 | 8.98 | <0.001 |

| LLAi | CTR-WW | 3.93 | 0.173 | 22.739 | <0.001 |

| PLAi | CTR-WW | 4.24 | 0.18 | 23.519 | <0.001 |

| LLAi | ELR-WD | 4.39 | 0.482 | 9.118 | <0.001 |

| PLAi | ELR-WD | 2.73 | 0.302 | 9.033 | <0.001 |

| LLAi | ELR-WW | 4.95 | 0.221 | 22.373 | <0.001 |

| PLAi | ELR-WW | 4.73 | 0.218 | 21.691 | <0.001 |

| LLAi | LLR-WD | 3.31 | 0.409 | 8.109 | <0.001 |

| PLAi | LLR-WD | 1.19 | 0.156 | 7.601 | <0.001 |

| LLAi | LLR-WW | 4.02 | 0.174 | 23.147 | <0.001 |

| PLAi | LLR-WW | 3.36 | 0.143 | 23.607 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tosi, V.; Palai, G.; Verosimile, C.M.; Pompeiano, A.; D’Onofrio, C. Vine Water Status Modulates the Physiological Response to Different Apical Leaf Removal Treatments in Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.) Grapevines. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121524

Tosi V, Palai G, Verosimile CM, Pompeiano A, D’Onofrio C. Vine Water Status Modulates the Physiological Response to Different Apical Leaf Removal Treatments in Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.) Grapevines. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121524

Chicago/Turabian StyleTosi, Vincenzo, Giacomo Palai, Carmine Mattia Verosimile, Antonio Pompeiano, and Claudio D’Onofrio. 2025. "Vine Water Status Modulates the Physiological Response to Different Apical Leaf Removal Treatments in Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.) Grapevines" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121524

APA StyleTosi, V., Palai, G., Verosimile, C. M., Pompeiano, A., & D’Onofrio, C. (2025). Vine Water Status Modulates the Physiological Response to Different Apical Leaf Removal Treatments in Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.) Grapevines. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121524