Vacuum Infusion of High-Intensity Sweeteners Enhances Quality Attributes of Cherry Tomato

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

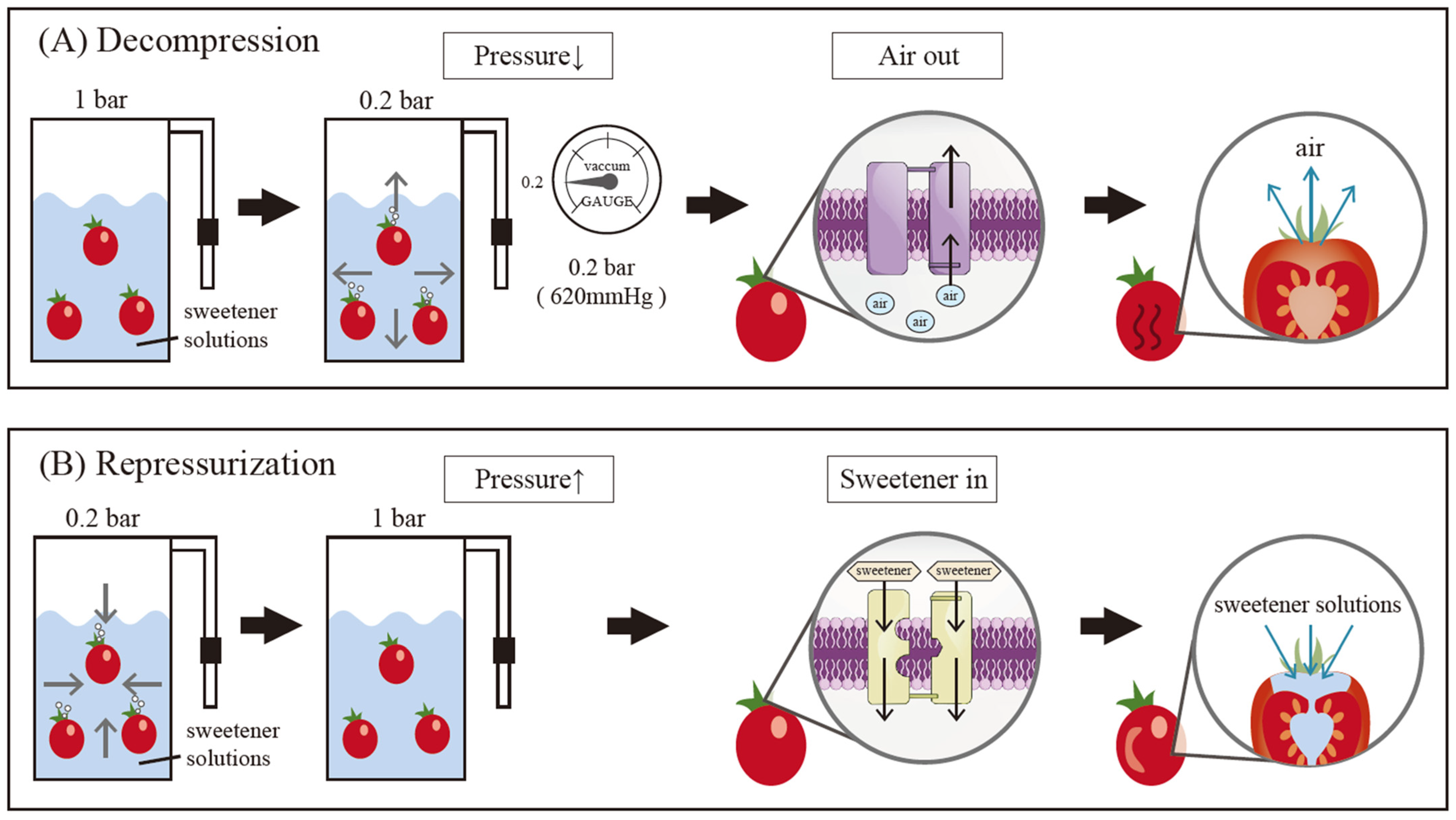

2.1. Plant Material and Vacuum-Infusion Treatment

2.2. Weight of Infused Sweetener Solutions into Cherry Tomatoes

2.3. Firmness and Microstructural Observation

2.4. Physiological Changes

2.5. Physicochemical and Sensory Qualities

2.6. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

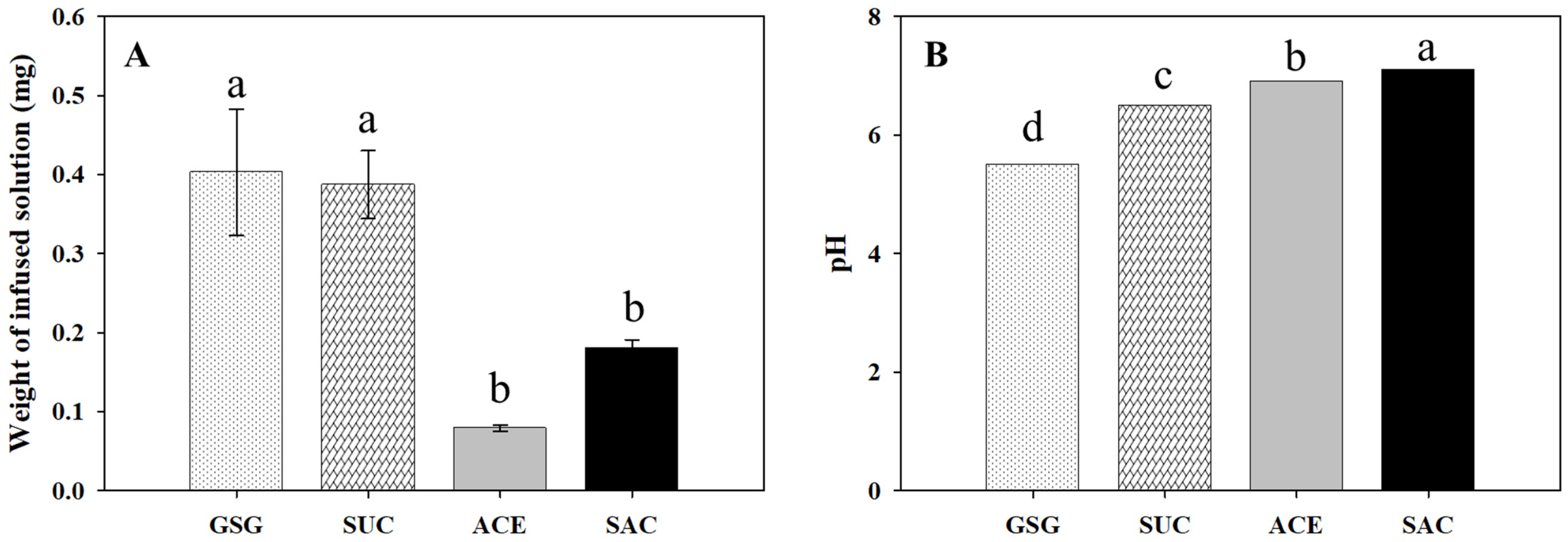

3.1. Weight Response of Cherry Tomatoes to Vacuum Infusion of the Sweetener Solutions

3.2. Texture and Physiological Changes of Sweeteners Infused Cherry Tomatoes During Storage

3.3. Storage-Related Microstructure of Sweeteners Infused Cherry Tomatoes

3.4. Color Changes of Sweeteners Infused Cherry Tomatoes During Storage

3.5. Physicochemical and Sensory Qualities of Sweeteners Infused Cherry Tomatoes During Storage

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bellisle, F.; Drewnowski, A. Intense Sweeteners, Energy Intake and the Control of Body Weight. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.Y.; Kim, T.H. The Effect of Food Consumption Value on Attitude towards Alternative Sweetened Foods and Purchase Intention: Focusing on the Moderating Effect of Subjective Body Image. Culi. Sci. Hos. Res. 2022, 28, 124–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, S.B.; Kim, S.J.; Park, S.W. Market and Trend of Alternative Sweeteners. FSI 2016, 49, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wiet, S.G.; Beyts, P.K. Sensory Characteristics of Sucralose and Other High Intensity Sweeteners. J. Food Sci. 1992, 57, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotz, V.L.; Munro, I.C. An Overview of the Safety of Sucralose. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 55, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Rymon Lipinski, G.W. The New Intense Sweetener Acesulfame K. Food Chem. 1985, 16, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, H.J.; Choi, S. Use of Sodium Saccharin and Sucralose in Foodstuffs and the Estimated Daily Intakes of Both Products in Korea. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 45, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ha, M.S.; Ha, S.D.; Choi, S.H.; Bae, D.H. Assessment of Korean Consumer Exposure to Sodium Saccharin, Aspartame and Stevioside. Food Addit. Contam. 2013, 30, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.W.; Lee, J.H.; Yeo, C.E.; Tae, S.H.; Chang, S.M.; Choi, H.R.; Park, D.S.; Tilahun, S.; Jeong, C.S. Antioxidant Profile, Amino Acids Composition, and Physicochemical Characteristics of Cherry Tomatoes Are Associated with Their Color. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Lv, Z.; Pan, Z.; Wei, Y.; Shu, C.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W. Analysis of Nutrients and Volatile Compounds in Cherry Tomatoes Stored at Different Temperatures. Foods 2023, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, S.; Choi, H.R.; Baek, M.W.; Cheol, L.H.; Kwak, K.W.; Park, D.S.; Solomon, T.; Jeong, C.S. Antioxidant Properties, γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Content, and Physicochemical Characteristics of Tomato Cultivars. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KREI. Korea Rural Economic Institute. Consumption Behavior of Major Fruits and Vegetables in Summer and Purchase Intentions for 2025; Technical Report; Korea Rural Economic Institute: Naju-si, Republic of Korea, 2025; pp. 1–28. (In Korean)

- Giannakourou, M.C.; Lazou, A.E.; Dermesonlouoglou, E.K. Optimization of Osmotic Dehydration of Tomatoes in Solutions of Non-Conventional Sweeteners by Response Surface Methodology and Desirability Approach. Foods 2020, 9, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulistyawati, I.; Dekker, M.; Verkerk, R.; Shen, Y. Effect of Vacuum Impregnation and High Pressure in Osmotic Dehydration and Air Drying on Physicochemical Properties of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Cubes-Maturity Stage 1; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017; p. 9203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Xie, J. Practical Applications of Vacuum Impregnation in Fruit and Vegetable Processing. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 434–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, A.; Guillon, F.; Degraeve, P.; Rondeau, C.; Devaux, M.-F.; Huber, F.; Badel, E.; Saurel, R.; Lahaye, M. Firming of Fruit Tissues by Vacuum-Infusion of Pectin Methylesterase: Visualisation of Enzyme Action. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- FDA U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Tikekar, R.V. Air Microbubble Assisted Washing of Fresh Produce: Effect on Microbial Detachment and Inactivation. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 181, 111687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.T.N.; Thuy, N.M. Optimization of Vacuum Infiltration before Blanching of Black Cherry Tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum Cv. Og) Using Response Surface Methodology. Food Res. 2020, 4, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinod, B.R.; Asrey, R.; Sethi, S.; Menaka, M.; Meena, N.K.; Shivaswamy, G. Recent Advances in Vacuum Impregnation of Fruits and Vegetables Processing: A Concise Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbury, D.E.; Ritchie, N.W.M. Performing Elemental Microanalysis with High Accuracy and High Precision by Scanning Electron Microscopy/Silicon Drift Detector Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectrometry (SEM/SDD-EDS). J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 50, 493–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, L.; Strausborger, S.; Lewin-Smith, M. Automated Particle Analysis Using Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) to Characterize Inhaled Particulate Matter (PM) in Biopsied Lung Tissue. Microsc. Microanal. 2023, 29, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legland, D.; Arganda-Carreras, I. MorphoLibJ User Manual; Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique: Nantes, France, 2016; pp. 1–93.

- Tilahun, S.; Park, D.S.; Taye, A.M.; Jeong, C.S. Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.R.; Tilahun, S.; Park, D.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Choi, J.H.; Baek, M.W.; Jeong, C.S. Harvest Time Affects Quality and Storability of Kiwifruit (Actinidia Spp.): Cultivars during Long-Term Cool Storage. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera-Chiner, L.; Vilhena, N.Q.; Larrea, V.; Moraga, G.; Salvador, A. Influence of Temperature on ‘Rojo Brillante’ Persimmon Drying. Quality Characteristics and Drying Kinetics. LWT 2024, 197, 115902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichchukit, S.; O’Mahony, M. The 9-point hedonic scale and hedonic ranking in food science: Some reappraisals and alternatives. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2167–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.P.F.; Huber, D.J. Apoplastic PH and Inorganic Ion Levels in Tomato Fruit: A Potential Means for Regulation of Cell Wall Metabolism during Ripening. Physiol. Plant 1999, 105, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, J.; Cosgrove, D.J. The Expansin Superfamily. Genome Biol. 2005, 6, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chun, J.-P.; Huber, D.J. Polygalacturonase-Mediated Solubilization and Depolymerization of Pectic Polymers in Tomato Fruit Cell Walls: Regulation by PH and Ionic Conditions. Plant Physiol. 1998, 117, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gawkowska, D.; Cybulska, J.; Zdunek, A. Structure-Related Gelling of Pectins and Linking with Other Natural Compounds: A Review. Polymers 2018, 10, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.R.; Powell, D.A.; Giiiley, M.J.; Rees, A. Conformations and interactions of pectins: I. Polymorphism between gel and solid states of calcium polygalacturonate. J. Mol. Biol. 1982, 155, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocking, B.; Tyerman, S.D.; Burton, R.A.; Gilliham, M. Fruit Calcium: Transport and Physiology. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hosni, A.; Joyce, D.C.; Hunter, M.; Perkins, M.; Al Yahyai, R. Altered Calcium and Potassium Distribution Maps in Tomato Tissues Cultivated under Salinity: Studies Using X-Ray Fluorescence (XFM) Microscopy. Irrig. Sci. 2025, 43, 613–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, Y.; Zohar, R.; Malis-Arad, S. Effect of sodium chloride on fruit ripening of the nonripening tomato mutants nor and rin. Plant Physiol. 1982, 69, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, S.C.F.; Almeida, D.P.F. Modulation of Tomato Pericarp Firmness through PH and Calcium: Implications for the Texture of Fresh-Cut Fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2008, 47, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragel, P.; Raddatz, N.; Leidi, E.O.; Quintero, F.J.; Pardo, J.M. Regulation of K + Nutrition in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.R.; Kumar, N.; Kavino, M. Role of potassium in fruit crops-a review. Agric. Rev. 2016, 27, 284–291. [Google Scholar]

- Thu, A.M.; Alam, S.M.; Khan, M.A.; Han, H.; Liu, D.H.; Tahir, R.; Ateeq, M.; Liu, Y.Z. Foliar Spraying of Potassium Sulfate during Fruit Development Comprehensively Improves the Quality of Citrus Fruits. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, E.A.; Nisperos-Carriedo, M.O.; Baker, R.A. Edible Coatings for Lightly Processed Fruits and Vegetables. HortScience 1995, 30, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.S.; Giovannoni, J.J. Ethylene and Fruit Ripening. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2007, 26, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Asgher, M.; Iqbal, N.; Rasheed, F.; Sehar, Z.; Sofo, A.; Khan, N.A. Ethylene Signaling under Stressful Environments: Analyzing Collaborative Knowledge. Plants 2022, 11, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Rao, Y.R.; Kaula, B.C.; Siddiqui, Z.H.; Al Messelmani, M.; Sahoo, R.K.; Ansari, M.W.; Pongiya, U.; Rakwal, R.; Tuteja, N.; et al. Ethylene Inhibitors Improve Crop Productivity by Modulating Gene Expression, Antioxidant Defense Machinery and Photosynthetic Efficiency of Solanum lycopersicum L. Cv. Pusa Ruby Grown in Controlled Salinity Stress Conditions. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 161, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.; Grierson, D. Ethylene Biosynthesis and Action in Tomato: A Model for Climacteric Fruit Ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 2039–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhang, B.; Grierson, D.; Chen, K.; Xu, C. Effect of Ethylene on Cell Wall and Lipid Metabolism during Alleviation of Postharvest Chilling Injury in Peach. Cells 2019, 8, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Hu, N.; Xiao, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Mao, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Guo, H. A Molecular Framework of Ethylene-Mediated Fruit Growth and Ripening Processes in Tomato. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3280–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Ulate, B.; Vincenti, E.; Cantu, D.; Powell, A.L.T. Ripening of Tomato Fruit and Susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea. In Botrytis–the Fungus, the Pathogen and Its Management in Agricultural Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 387–412. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zeng, S.; Dai, R.; Chen, K. Slow and Steady Wins the Race: The Negative Regulators of Ethylene Biosynthesis in Horticultural Plants. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, R.E. Effect of temperature and relative humidity on fresh commodity quality. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1999, 15, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth-Mezőfi, Z.; Baranyai, L.; Nguyen, L.L.P.; Dam, M.S.; Ha, N.T.T.; Göb, M.; Sasvár, Z.; Csurka, T.; Zsom, T.; Hitka, G. Evaluation of Color and Pigment Changes in Tomato after 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) Treatment. Sensors 2024, 24, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athmaselvi, K.A.; Sumitha, P.; Revathy, B. Development of Aloe Vera Based Edible Coating for Tomato. Int. Agrophys. 2013, 27, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker, F.R.; Redgwell, R.J.; Hallett, I.C.; Murray, S.H.; Carter, G. Texture of Fresh Fruit. In Horticultural Reviews; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 121–224. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, P.D.; Truesdale, M.R.; Bird, C.R.; Schuch, W.; Bramley, P.M. Carotenoid Biosynthesis during Tomato Fruit Development (Evidence for Tissue-Specific Gene Expression). Plant Physiol. 1994, 105, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Diretto, G.; Purgatto, E.; Danoun, S.; Zouine, M.; Li, Z.; Roustan, J.P.; Bouzayen, M.; Giuliano, G.; Chervin, C. Carotenoid Accumulation during Tomato Fruit Ripening Is Modulated by the Auxin-Ethylene Balance. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’evoli, L.; Lombardi-Boccia, G.; Lucarini, M. Influence of Heat Treatments on Carotenoid Content of Cherry Tomatoes. Foods 2013, 2, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.H.; Chen, B.H. Stability of Carotenoids in Tomato Juice during Processing. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2005, 221, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, R.; McGlasson, B.; Graham, D.; Joyce, D. Postharvest-An Introduction to the Physiology and Handling of Fruit, Vegetables and Ornamentals. Cabi Publ. 2007, 44, 1–252. [Google Scholar]

- Mattheis, J.P.; Fellman, J.K. Preharvest Factors Influencing Flavor of Fresh Fruit and Vegetables. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1999, 15, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, A.; Génard, M.; Lobit, P.; Mbeguié-A-Mbéguié, D.; Bugaud, C. What Controls Fleshy Fruit Acidity? A Review of Malate and Citrate Accumulation in Fruit Cells. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1451–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista-Silva, W.; Nascimento, V.L.; Medeiros, D.B.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Ribeiro, D.M.; Zsögön, A.; Araújo, W.L. Modifications in Organic Acid Profiles during Fruit Development and Ripening: Correlation or Causation? Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Treatments | Storage Period (Days) | Significance Levels (p) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Day | 2 Day | 4 Day | Day (A) | Treatment (B) | A × B | ||

| K (%) | GSG | 91.45 ± 1.24 b | 94.50 ± 0.53 a | 94.72 ± 0.52 a | ** | ns | *** |

| SUC | 90.81 ± 1.13 b | 93.61 ± 0.97 a | 94.31 ± 0.70 a | ||||

| ACE | 94.76 ± 0.65 a | 94.05 ± 1.43 a | 94.49 ± 0.31 a | ||||

| SAC | 89.95 ± 2.71 b | 95.27 ± 0.97 a | 94.81 ± 1.03 a | ||||

| Ca (%) | GSG | 6.96 ± 1.33 a | 3.11 ± 0.61 b | 2.55 ± 0.39 b | * | * | *** |

| SUC | 6.35 ± 0.99 a | 3.96 ± 0.80 b | 3.24 ± 0.74 b | ||||

| ACE | 3.88 ± 0.91 b | 3.68 ± 1.14 b | 3.18 ± 0.37 b | ||||

| SAC | 6.90 ± 2.12 a | 3.12 ± 0.54 b | 3.64 ± 0.63 b | ||||

| Mg (%) | GSG | 1.59 ± 0.13 c | 2.40 ± 0.10 b | 2.73 ± 0.19 ab | ** | *** | *** |

| SUC | 2.83 ± 0.22 ab | 2.43 ± 0.25 b | 2.44 ± 0.05 b | ||||

| ACE | 1.36 ± 0.27 c | 2.27 ± 0.29 b | 2.34 ± 0.05 b | ||||

| SAC | 3.15 ± 0.65 a | 1.61 ± 0.44 c | 1.55 ± 0.64 c | ||||

| Parameters | Treatments | Storage Period (Days) | Significance Levels (p) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Day | 1 Day | 2 Day | 3 Day | 4 Day | Days (A) | Treatments (B) | A × B | ||

| TSS (%) | GSG | 6.83 ± 0.19 bA | 6.50 ± 0.15 aAB | 6.47 ± 0.18 aAB | 6.50 ± 0.06 aAB | 6.13 ± 0.09 aB | *** | *** | ns |

| SUC | 6.93 ± 0.09 abA | 6.57 ± 0.22 aAB | 6.73 ± 0.12 aAB | 6.70 ± 0.15 aAB | 6.43 ± 0.18 aB | ||||

| ACE | 7.00 ± 0.06 abA | 6.83 ± 0.26 aA | 6.80 ± 0.15 aA | 6.70 ± 0.06 aA | 6.67 ± 0.09 aA | ||||

| SAC | 7.20 ± 0.06 aA | 7.00 ± 0.15 aA | 6.97 ± 0.09 aA | 6.87 ± 0.07 aA | 6.23 ± 0.09 aB | ||||

| TA (mg 100 g−1) | GSG | 0.85 ± 0.03 aA | 0.75 ± 0.02 bAB | 0.74 ± 0.03 aAB | 0.72 ± 0.07 aAB | 0.66 ± 0.02 aB | ** | *** | ns |

| SUC | 0.80 ± 0.02 aA | 0.77 ± 0.06 bA | 0.72 ± 0.01 aA | 0.75 ± 0.03 aA | 0.75 ± 0.01 aA | ||||

| ACE | 0.87 ± 0.05 aA | 0.89 ± 0.01 aAB | 0.80 ± 0.04 aBC | 0.82 ± 0.04 aC | 0.78 ± 0.04 aC | ||||

| SAC | 0.75 ± 0.02 aA | 0.72 ± 0.01 bAB | 0.72 ± 0.03 aAB | 0.73 ± 0.01 aAB | 0.70 ± 0.01 aB | ||||

| TSS/TA | GSG | 8.05 ± 0.34 aA | 8.65 ± 0.39 abA | 8.78 ± 0.25 abA | 9.26 ± 0.94 aA | 9.24 ± 0.26 aA | ns | ** | ns |

| SUC | 8.65 ± 0.34 abA | 8.64 ± 0.88 abA | 9.38 ± 0.31 abA | 9.01 ± 0.58 aA | 8.55 ± 0.34 aA | ||||

| ACE | 8.13 ± 0.49 bA | 7.70 ± 0.33 bAB | 8.52 ± 0.23 bABC | 8.70 ± 0.51 aBC | 8.17 ± 0.45 aC | ||||

| SAC | 9.67 ± 0.27 aA | 9.77 ± 0.10 aA | 9.77 ± 0.48 aA | 9.38 ± 0.16 aAB | 8.97 ± 0.14 aB | ||||

| pH | GSG | 4.31 ± 0.01 ab | 4.38 ± 0.04 ab | 4.41 ± 0.05 a | 4.50 ± 0.03 a | 4.64 ± 0.05 a | *** | *** | * |

| SUC | 4.33 ± 0.03 ab | 4.37 ± 0.02 ab | 4.39 ± 0.06 a | 4.44 ± 0.02 ab | 4.44 ± 0.01 ab | ||||

| ACE | 4.30 ± 0.04 b | 4.33 ± 0.01 b | 4.39 ± 0.03 a | 4.39 ± 0.02 ab | 4.39 ± 0.03 b | ||||

| SAC | 4.41 ± 0.02 a | 4.43 ± 0.02 a | 4.41 ± 0.02 a | 4.43 ± 0.03 b | 4.52 ± 0.05 ab | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, M.W.; Chang, S.M.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Ko, A.Y.; Choi, J.I.; Kim, M.J.; Tilahun, S.; Jeong, C.S. Vacuum Infusion of High-Intensity Sweeteners Enhances Quality Attributes of Cherry Tomato. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121503

Baek MW, Chang SM, Lee JH, Lee JH, Ko AY, Choi JI, Kim MJ, Tilahun S, Jeong CS. Vacuum Infusion of High-Intensity Sweeteners Enhances Quality Attributes of Cherry Tomato. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121503

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Min Woo, Se Min Chang, Ju Hyeon Lee, Jin Hee Lee, A Yeong Ko, Ji In Choi, Min Joon Kim, Shimeles Tilahun, and Cheon Soon Jeong. 2025. "Vacuum Infusion of High-Intensity Sweeteners Enhances Quality Attributes of Cherry Tomato" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121503

APA StyleBaek, M. W., Chang, S. M., Lee, J. H., Lee, J. H., Ko, A. Y., Choi, J. I., Kim, M. J., Tilahun, S., & Jeong, C. S. (2025). Vacuum Infusion of High-Intensity Sweeteners Enhances Quality Attributes of Cherry Tomato. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121503