The Combined Effect of Late Pruning and Apical Defoliation After Veraison on Kékfrankos (Vitis vinifera L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Impacts of Climate Change

1.2. Viticultural Strategies Against Climate Change

1.3. Experimental Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Conditions

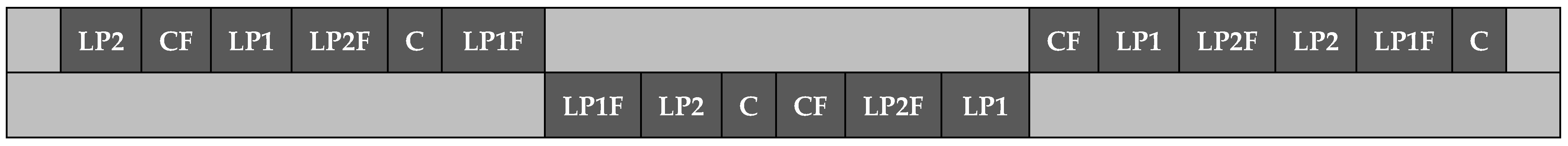

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Climatic Data

2.4. Vine Phenology

2.5. Standard Chemical Analysis

2.6. Yield Components

2.7. Xylem Sap Collection

2.8. Xylem Sap Analysis

2.9. Extraction of Grape Skins for Total Polyphenol (TPC) Assay

2.10. Total Polyphenol Content (TPC) Determination

2.11. Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

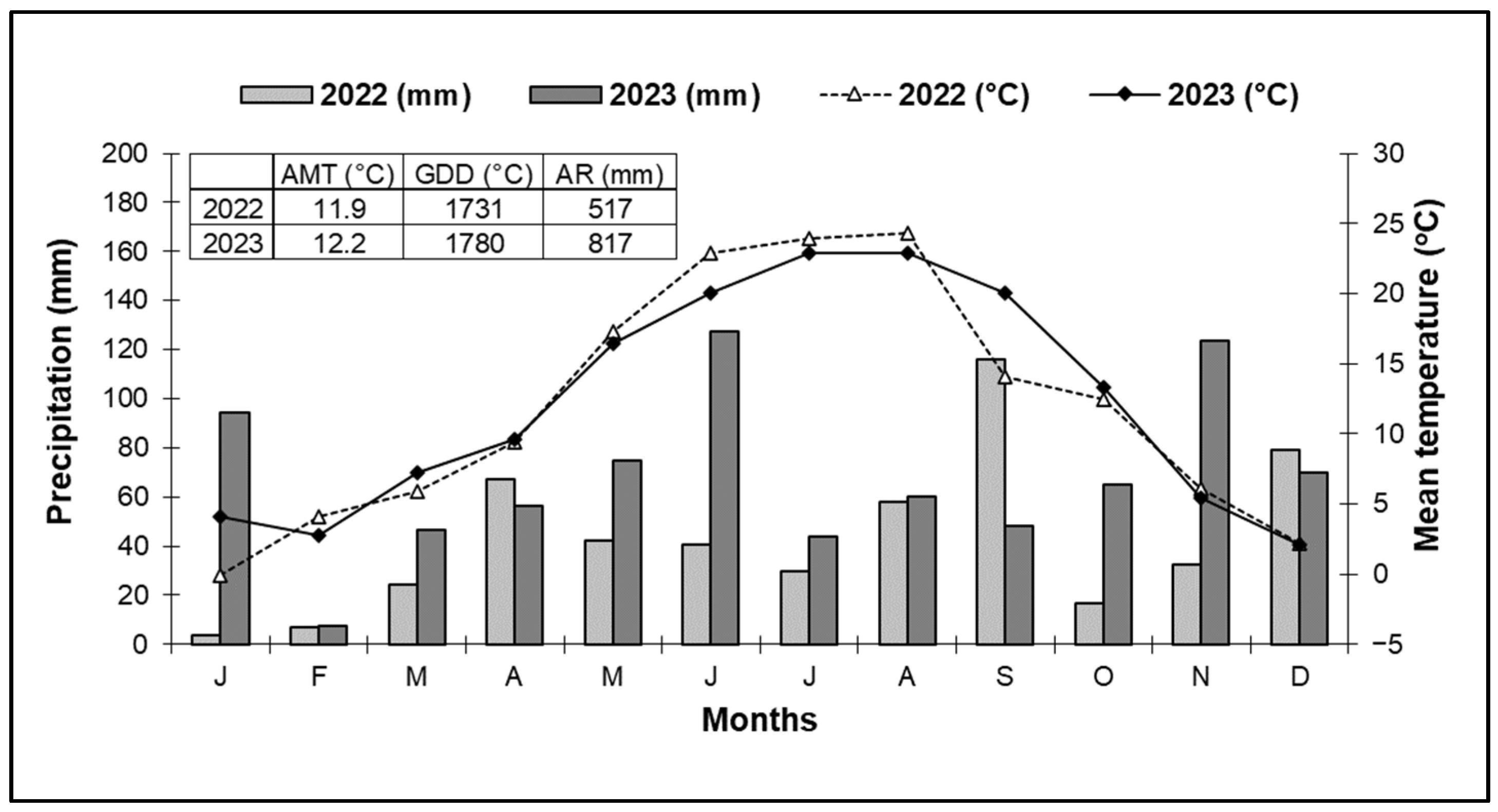

3.1. Vintage Analysis

3.2. Phenology

3.3. Grape Juice Analysis

3.4. Changes in Yield and Cane Parameters, and the Evolution of the Carbohydrate Content of the Xylem Sap

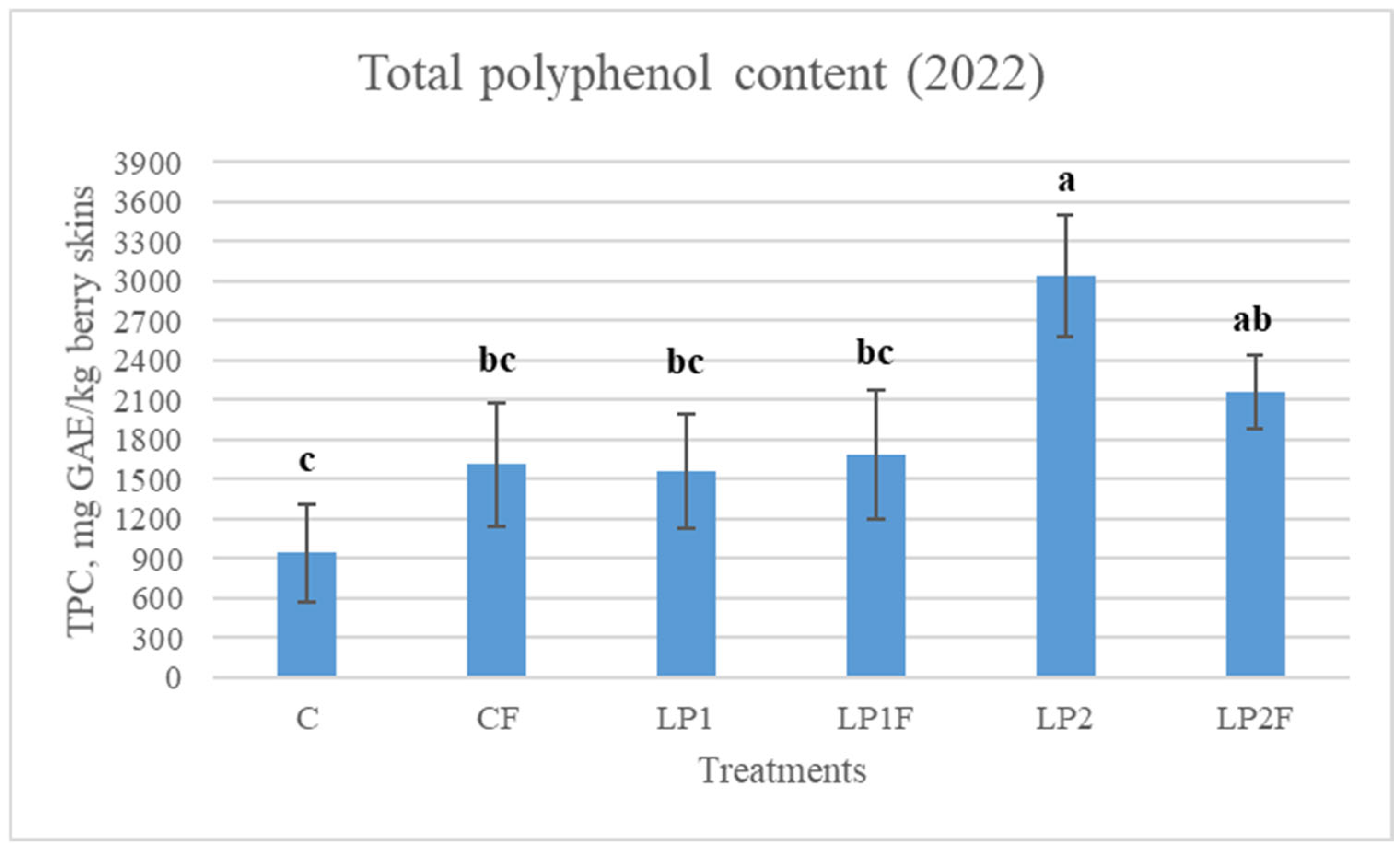

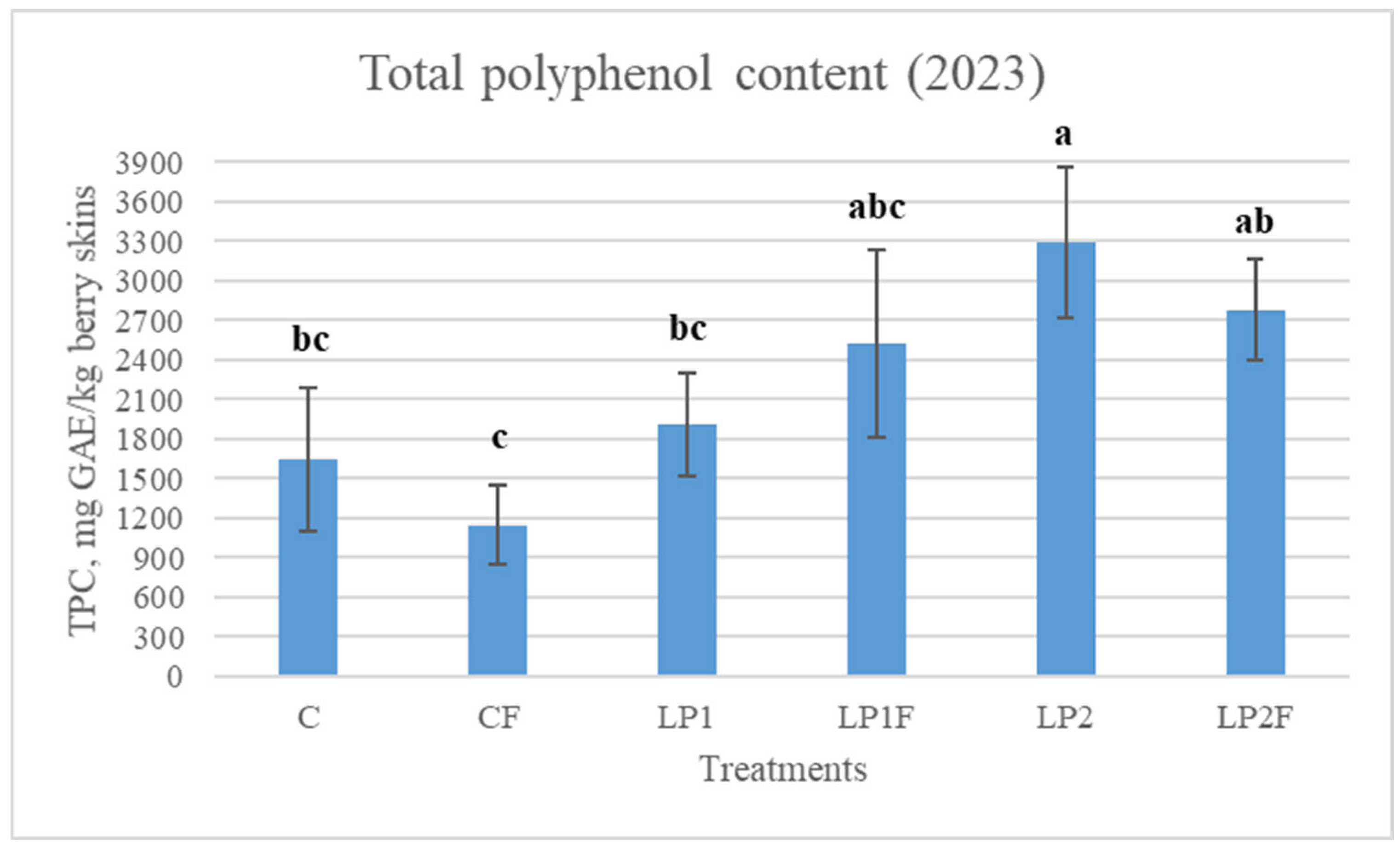

3.5. Grape Skin Total Phenolic Content

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Leeuwen, C.; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Dubernet, M.; Duchêne, E.; Gowdy, M.; Marguerit, E.; Pieri, P.; Parker, A.; de Rességuier, L.; Ollat, N. An update on the impact of climate change in viticulture and potential adaptations. Agronomy 2019, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.A.; Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Dinis, L.-T.; Correia, C.; Moriondo, M.; Leolini, L.; Dibari, C.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; et al. A review of the potential climate change impacts and adaptation options for European viticulture. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, D.L.E.; Cirrincione, M.A.; Deis, L.; Martínez, L.E. Impacts of climate change-induced temperature rise on phenology, physiology, and yield in three red grape cultivars: Malbec, Bonarda, and Syrah. Plants 2024, 13, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faralli, M.; Mallucci, S.; Bignardi, A.; Varner, M.; Bertamini, M. Four decades in the vineyard: The impact of climate change on grapevine phenology and wine quality in northern Italy. OENO One 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.; Vargas Soto, S.; Gambetta, G.; Schober, D.; Jeffers, E.; Coulson, T. Modelling the climate changing concentrations of key red wine grape quality molecules using a flexible modelling approach. OENO One 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegro, G.; Pastore, C.; Valentini, G.; Filippetti, I. Post-budburst hand finishing of winter spur pruning can delay technological ripening without altering phenolic maturity of Merlot berries. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2020, 26, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Sabbatini, P.; Palliotti, A. Facing spring frost damage in grapevine: Recent developments and the role of delayed winter pruning—A review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2022, 73, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Zheng, W.; Martínez de Toda, F. Current viticultural techniques to mitigate the effects of global warming on grape and wine quality: A comprehensive review. Food Res. Int. 2021, 139, 109946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Granco, G.; Groves, L.; Voong, J.; Van Zyl, S. Viticultural manipulation and new technologies to address environmental challenges caused by climate change. Climate 2023, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercesi, A.; Gabrielli, M.; Garavani, A.; Poni, S. Effects of apical, late-season leaf removal on vine performance and wine properties in Sangiovese grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.). Horticulturae 2024, 10, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotti, L.; Partida, G.; Laroche-Pinel, E.; Lanari, V.; Pedroza, M.; Brillante, L. Late-season source limitation practices to cope with climate change: Delaying ripening and improving colour of Cabernet-Sauvignon grapes and wine in a hot and arid climate. OENO One 2025, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; Pirez, F.J.; Chiari, G.; Tombesi, S.; Palliotti, A.; Merli, M.C.; Poni, S. Phenology, canopy aging and seasonal carbon balance as related to delayed winter pruning of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Sangiovese grapevines. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliotti, A.; Frioni, T.; Tombesi, S.; Sabbatini, P.; Cruz-Castillo, J.G.; Lanari, V.; Silvestroni, O.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S. Double-pruning grapevines as a management tool to delay berry ripening and control yield. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2017, 68, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, P.R.; Brooke, S.J.; Moran, M.A.; Sadras, V.O. Pruning after budburst to delay and spread grape maturity. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; Pirez, F.J.; Frioni, T.; Squeri, C.; Poni, S. Calibrated, delayed-cane winter pruning controls yield and significantly postpones berry ripening parameters in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Pinot Noir. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2018, 24, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiglieno, I.; Facciano, L.; Valenti, L.; Amari, F.; Cola, G. Evaluation of the impact of vine pruning periods on grape production and composition: An integrated approach considering different years and cultivars. OENO One 2025, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reta, K.; Netzer, Y.; Lazarovitch, N.; Fait, A. Canopy management practices in warm environment vineyards to improve grape yield and quality in a changing climate. A review A vademecum to vine canopy management under the challenge of global warming. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 341, 113998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Frioni, T.; Gatti, M. Summer pruning in Mediterranean vineyards: Is climate change affecting its perception, modalities, and effects? Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1227628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palliotti, A.; Panara, F.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Sabbatini, P.; Howell, G.S.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S. Influence of mechanical postveraison leaf removal apical to the cluster zone on delay of fruit ripening in Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.) grapevines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2013, 19, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccavello, G.; Giaccone, M.; Scognamiglio, P.; Forlani, M.; Basile, B. Influence of intensity of post-veraison defoliation or shoot trimming on vine physiology, yield components, berry and wine composition in Aglianico grapevines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, X.; Needs, S.; Liu, D.; Fuentes, S.; Howell, K. The influence of apical and basal defoliation on the canopy structure and biochemical composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Shiraz grapes and wine. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Council of the Wine Communities. 2025. Available online: https://djrowwfyvvz5i.cloudfront.net/production/documents/magyarorszag---borszolovel-beultetett-terulet-20250731.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Frioni, T.; Romanini, E.; Pagani, S.; Del Zozzo, F.; Lambri, M.; Vercesi, A.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S.; Gabrielli, M. Reintroducing autochthonous minor grapevine varieties to improve wine quality and viticulture sustainability in a climate change scenario. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2023, 2023, 1482548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltazar, M.; Castro, I.; Gonçalves, B. Adaptation to climate change in viticulture: The role of varietal selection—A review. Plants 2025, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.A.; Sadras, V.O.; Petrie, P.R. Late pruning and carry-over effects on phenology, yield components and berry traits in Shiraz. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villangó, S.; Szekeres, A.; Végvári, G.; Ficzek, G.; Simon, G.; Zsófi, Z. First experience of late pruning on Kékfrankos grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) in Eger wine region (Hungary). Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.H.; Eichhorn, K.W.; Bleiholder, H.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Weber, E. Growth stages of the grapevine: Phenological growth stages of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. vinifera)—Codes and descriptions according to the extended BBCH scale†. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1995, 1, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV. Compendium of International Methods of Wine and Must Analysis International Organisation of Vine and Wine. 2023. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/standards/compendium-of-international-methods-of-wine-and-must-analysis (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Zheng, T.; Haider, M.S.; Zhang, K.; Jia, H.; Fang, J. Biological and functional properties of xylem sap extracted from grapevine (cv. Rosario Bianco). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoudakis, N.; Esteruelas, M.; Fort, F.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F. Comparison of methods for estimating phenolic maturity in grapes: Correlation between predicted and obtained parameters. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 660, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patonay, K.; Szalontai, H.; Csugány, J.; Szabó-Hudák, O.; Kónya, E.P.; Németh, É.Z. Comparison of extraction methods for the assessment of total polyphenol content and in vitro antioxidant capacity of horsemint (Mentha longifolia (L.) L.). J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2019, 15, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persico, M.J.; Smith, D.E.; Centinari, M. Delaying budbreak to reduce freeze damage: Seasonal vine performance and wine composition in two Vitis vinifera cultivars. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2021, 72, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos Morgani, M.; Fanzone, M.; Perez Peña, J.E.; Sari, S.; Gallo, A.E.; Gómez Tournier, M.; Prieto, J.A. Late pruning modifies leaf to fruit ratio and shifts maturity period, affecting berry and wine composition in Vitis vinífera L. cv. ‘Malbec’ in Mendoza, Argentina. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 313, 111861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Gatti, M.; Bernizzoni, F.; Civardi, S.; Bobeica, N.; Magnanini, E.; Palliotti, A. Late leaf removal aimed at delaying ripening in cv. Sangiovese: Physiological assessment and vine performance. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2013, 19, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-C.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, C.-F.; Chen, W.; Li, S.-D.; He, F.; Duan, C.-Q.; Wang, J. Distal leaf removal made balanced source-sink vines, delayed ripening, and increased flavonol composition in Cabernet Sauvignon grapes and wines in the semi-arid Xinjiang. Food Chem. 2022, 366, 130582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, G.; Szőke, B.Á.; Steckl, S.; Szövényi, Á.P.; Knolmajerné Szigeti, G.; Németh, C.; Jenei, B.G.; Nyitrainé Sárdy, D.Á. Delay in the ripening of wine grapes: Effects of specific phytotechnical methods on harvest parameters. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessarin, P.; Parpinello, G.P.; Rombolà, A.D. Physiological and enological implications of postveraison trimming in an organically-managed Sangiovese vineyard. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2018, 69, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, M.K.; Creasy, G.L.; Hofmann, R.W.; Parker, A.K. Changes in total soluble solids concentration, fruit acidity, and yeast assimilable nitrogen in response to altered leaf area to fruit weight ratio in Pinot noir. OENO One 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; Garavani, A.; Krajecz, K.; Ughini, V.; Parisi, M.G.; Frioni, T.; Poni, S. Mechanical mid-shoot leaf removal on Ortrugo (Vitis vinifera L.) at pre- or mid-veraison alters fruit growth and maturation. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2019, 70, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lüscher, J.; Kurtural, S.K. Same season and carry-over effects of source-sink adjustments on grapevine yields and non-structural carbohydrates. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 695319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertamini, M.; Faralli, M. Late pruning and forced vine regrowth in Chardonnay and Pinot Noir: Benefits and drawbacks in the Trento DOC Basin (Italy). Agronomy 2023, 13, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelini, S.; Tomada, S.; Kadison, A.E.; Pichler, F.; Hinz, F.; Zejfart, M.; Iannone, F.; Lazazzara, V.; Sanoll, C.; Robatscher, P.; et al. Modeling malic acid dynamics to ensure quality, aroma and freshness of Pinot blanc wines in South Tyrol (Italy). OENO One 2021, 55, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volschenk, H.; van Vuuren, H.J.J.; Viljoen-Bloom, M. Malic acid in wine: Origin, function and metabolism during vinification. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 27, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; Baran, Y.; Navascués, E.; Santos, A.; Calderón, F.; Marquina, D.; Rauhut, D.; Benito, S. Biological management of acidity in wine industry: A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 375, 109726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni, T.; Tombesi, S.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Bellincontro, A.; Sabbatini, P.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S.; Palliotti, A. Postbudburst spur pruning reduces yield and delays fruit sugar accumulation in Sangiovese in central Italy. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 67, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Lattanzi, T.; Palliotti, A. Delaying winter pruning, after pre-pruning, alters budburst, leaf area, photosynthesis, yield and berry composition in Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.). Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2018, 24, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; García, J.; Balda, P.; Martínez de Toda, F. Effects of late winter pruning at different phenological stages on vine yield components and berry composition in La Rioja, North-central Spain. OENO One 2017, 51, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.A.; Bastian, S.E.; Petrie, P.R.; Sadras, V.O. Late pruning impacts on chemical and sensory attributes of Shiraz wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2018, 24, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesa, I.; Yeves, A.; Sanz, F.; Chirivella, C.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Effect of delaying winter pruning of Bobal and Tempranillo grapevines on vine performance, grape and wine composition. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2021, 27, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T.; Jeong, S.T.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Koshita, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Effects of temperature on anthocyanin biosynthesis in grape berry skins. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienth, M.; Torregrosa, L.; Sarah, G.; Ardisson, M.; Brillouet, J.-M.; Romieu, C. Temperature desynchronizes sugar and organic acid metabolism in ripening grapevine fruits and remodels their transcriptome. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, M.K.; Creasy, G.L.; Hofmann, R.W.; Parker, A.K. Asynchronous accumulation of sugar and phenolics in grapevines following post-veraison leaf removal. OENO One 2025, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Abbreviation | Treatment Description | Treatment | Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late Pruning 1 | Late Pruning 2 | Late Apical Defoliation | |||

| C | Control | Pruning was performed at dormancy (BBCH-00) No apical defoliation was applied | |||

| CF | Late apical defoliation | ✓ | Late apical defoliation was carried out when the berries reached about 16 °Brix in both years | ||

| LP1 | Late pruning 1 | ✓ | Late pruning 1 was performed when the control vines reached BBCH-14: four leaves folded | ||

| LP1F | Late pruning 1 + Late apical defoliation | ✓ | ✓ | Combination of LP1 and CF | |

| LP2 | Late pruning 2 | ✓ | Late pruning 2 was carried out when the control vines reached BBCH-18: eight leaves folded | ||

| LP2F | Late pruning 2 + Late apical defoliation | ✓ | ✓ | Combination of LP2 and CF | |

| 2022 | DOY | Principal Growth Stages (BBCH-Code) for Each Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | LP1 | LP2 | ||

| 8 April | 98 | 1 (Beginning of bud swelling) | 0 | 0 |

| 13 April | 103 | 3 (End of bud swelling) | 0 | 0 |

| 29 April | 119 | 11 (First leaf unfolded) | 3 | 3 |

| 5 May (Late pruning 1) | 125 | 14 (Four leaves unfolded) | 5 | 5 |

| 12 May (Late pruning 2) | 132 | 18 (Eight leaves unfolded) | 9 | 5 |

| 19 May | 139 | 55 (Inflorescence swelling) | 16 | 11 |

| 26 May | 146 | 57 (Inflorescences fully developed) | 18 | 14 |

| 02 June | 153 | 60 (First flowerhoods detached from the receptacle) | 53 | 18 |

| 10 June | 161 | 68 (80% of flowerhoods fallen) | 57 | 53 |

| 20 June | 171 | 73 (Groat-sized berries) | 69 | 63 |

| 30 June | 181 | 75 (Pea-sized berries) | 71 | 69 |

| 11 July | 192 | 77 (Beginning of berry touch) | 75 | 73 |

| 22 July | 203 | 79 (Berry touch complete) | 77 | 75 |

| 4 August | 216 | 81 (Beginning of ripening) | 81 | 81 |

| 12 August | 224 | 85 (Softening of berries) | 83 | 83 |

| 19 August | 231 | 85 (Softening of berries) | 85 | 85 |

| 2023 | DOY | Principal Growth Stages (BBCH-Code) for Each Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | LP1 | LP2 | ||

| 4 April | 94 | 1 (Beginning of bud swelling) | 0 | 0 |

| 11 April | 101 | 3 (End of bud swelling) | 0 | 0 |

| 17 April | 107 | 7 (Beginning of bud burst) | 0 | 0 |

| 28 April | 118 | 8 (Bud burst) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 May (Late pruning 1) | 122 | 14 (Four leaves unfolded) | 3 | 3 |

| 9 May (Late pruning 2) | 129 | 18 (Eight leaves unfolded) | 7 | 3 |

| 18 May | 138 | 53 (Inflorescences clearly visible) | 12 | 9 |

| 26 May | 146 | 55 (Inflorescences swelling) | 14 | 12 |

| 1 June | 152 | 57 (Inflorescences fully developed) | 18 | 14 |

| 9 June | 160 | 61 (Beginning of flowering: 10% of flowerhoods fallen) | 57 | 53 |

| 14 June | 165 | 65 (Full flowering: 50% of flowerhoods fallen) | 61 | 57 |

| 19 June | 170 | 68 (80% of flowerhoods fallen) | 63 | 60 |

| 23 June | 174 | 71 (Fruit set) | 68 | 63 |

| 3 July | 184 | 75 (Berries pea-sized) | 73 | 71 |

| 10 July | 191 | 77 (Berries beginning to touch) | 75 | 73 |

| 20 July | 201 | 79 (Majority of berries touching) | 77 | 75 |

| 2 August | 214 | 79 (Majority of berries touching) | 79 | 77 |

| 8 August | 220 | 81 (Beginning of ripening) | 79 | 79 |

| 14 August | 226 | 83 (Berries developing colour) | 81 | 81 |

| 21 August | 233 | 85 (Softening of berries) | 83 | 83 |

| 30 August | 242 | 85 (Softening of berries) | 85 | 85 |

| Parameter | Vintage | Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | CF | LP1 | LP1F | LP2 | LP2F | ||

| °Brix | 2022 | 22.4 ± 0.8 a | 21.9 ± 0.4 a | 22.6 ± 0.4 a | 22.2 ± 1.6 a | 22.7 ± 0.4 a | 23.1 ± 0.7 a |

| 2023 | 23.0 ± 0.9 a | 20.7 ± 0.3 b | 22.2 ± 0.4 ab | 22.3 ± 0.4 a | 22.5 ± 0.7 a | 22.2 ± 0.5 ab | |

| Titratable acidity (g/L) | 2022 | 4.6 ± 0.3 a | 4.2 ± 0.3 a | 4.5 ± 0.3 a | 4.8 ± 0.5 a | 4.7 ± 0.3 a | 4.8 ± 0.3 a |

| 2023 | 6.8 ± 0.5 a | 6.8 ± 0.5 a | 7.3 ± 0.9 a | 6.9 ± 1.2 a | 8.2 ± 0.6 a | 8.5 ± 0.8 a | |

| pH | 2022 | 3.22 ± 0.04 a | 3.25 ± 0.08 a | 3.30 ± 0.05 a | 3.19 ± 0.05 a | 3.25 ± 0.05 a | 3.28 ± 0.08 a |

| 2023 | 3.19 ± 0.09 a | 3.26 ± 0.06 a | 3.17 ± 0.08 a | 3.17 ± 0.12 a | 3.09 ± 0.01 a | 3.07 ± 0.07 a | |

| Malic acid (g/L) | 2022 | 1.0 ± 0.2 c | 1.5 ± 0.1 ab | 1.1 ± 0.3 bc | 1.1 ± 0.2 bc | 2.0 ± 0.1 a | 2.0 ± 0.2 a |

| 2023 | 2.5 ± 0.2 c | 2.7 ± 0.1 bc | 2.8 ± 0.2 bc | 2.6 ± 0.2 c | 3.3 ± 0.5 ab | 3.7 ± 0.2 a | |

| Parameter | Vintage | Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | CF | LP1 | LP1F | LP2 | LP2F | ||

| Bunch/vine | 2022 | 13.2 ± 3.3 a | 14.9 ± 3.5 a | 12.6 ± 5.1 a | |||

| 2023 | 9.3 ± 3.0 a | 7.9 ± 1.7 a | 5.5 ± 1.4 b | ||||

| Bunch weight (g) | 2022 | 188 ± 88 ab | 218 ± 58 a | 106 ± 30 c | 147 ± 33 abc | 117 ± 34 bc | 118 ± 59 bc |

| 2023 | 298 ± 102 a | 248 ± 83 ab | 189 ± 100 bc | 126 ± 43 cd | 81 ± 38 d | 102 ± 54 d | |

| Weight of 100 berries (g) | 2022 | 1.61 ± 0.30 bc | 1.30 ± 0.28 d | 1.53 ± 0.29 c | 1.50 ± 0.26 c | 1.69 ± 0.29 ab | 1.77 ± 0.29 a |

| 2023 | 1.90 ± 0.40 a | 1.92 ± 0.32 a | 2.03 ± 0.30 a | 1.71 ± 0.37 b | 1.52 ± 0.41 c | 1.51 ± 0.36 c | |

| Cane diameter (mm) | 2022 | 8.24 ± 0.93 a | 7.62 ± 1.05 ab | 7.03 ± 1.25 b | 6.98 ± 0.98 b | 6.81 ± 1.18 b | 6.58 ± 1.17 b |

| 2023 | 7.56 ± 1.28 a | 7.60 ± 0.95 a | 6.64 ± 0.78 ab | 6.92 ± 1.08 ab | 6.09 ± 0.65 b | 6.02 ± 0.88 b | |

| Cane weight/vine (kg) | 2022 | 0.41 ± 0.08 a | 0.36 ± 0.06 abc | 0.29 ± 0.07 bc | 0.37 ± 0.05 ab | 0.31 ± 0.07 abc | 0.24 ± 0.02 c |

| 2023 | 0.37 ± 0.05 a | 0.34 ± 0.05 a | 0.24 ± 0.03 bc | 0.29 ± 0.06 ab | 0.19 ± 0.01 c | 0.23 ± 0.04 bc | |

| Parameter | Vintage | Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | CF | LP1 | LP1F | LP2 | LP2F | ||

| Glucose (mg/L) | 2022 | 256.6 ± 32.9 | 293.1 ± 50.5 | 222.3 ± 57.9 | 226.8 ± 38.0 | 206.1 ± 126.9 | 244.9 ± 6.1 |

| 2023 | 181.0 ± 66.7 | 244.4 ± 86.3 | 198.0 ± 74.1 | 204.8 ± 139.3 | 214.7 ± 63.3 | 260.6 ± 10.1 | |

| Fructose (mg/L) | 2022 | 38.0 ± 5.3 | 45.4 ± 6.9 | 33.8 ± 10.8 | 43.4 ± 23.7 | 37.8 ± 6.2 | 43.5 ± 10.1 |

| 2023 | 31.0 ± 1.9 | 39.3 ± 21.8 | 37.0 ± 5.2 | 53.4 ± 13.3 | 37.8 ± 11.2 | 50.9 ± 10.1 | |

| Myo-inositol (mg/L) | 2022 | 47.7 ± 8.3 | 56.4 ± 10.7 | 59.2 ± 16.5 | 35.2 ± 8.9 | 41.4 ± 28.1 | 36.8 ± 10.1 |

| 2023 | 19.7 ± 5.5 | 26.6 ± 14.4 | 22.5 ± 9.1 | 23.4 ± 2.3 | 21.1 ± 3.4 | 30.4 ± 10.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villangó, S.; Patonay, K.; Korózs, M.; Zsófi, Z. The Combined Effect of Late Pruning and Apical Defoliation After Veraison on Kékfrankos (Vitis vinifera L.). Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121450

Villangó S, Patonay K, Korózs M, Zsófi Z. The Combined Effect of Late Pruning and Apical Defoliation After Veraison on Kékfrankos (Vitis vinifera L.). Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121450

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillangó, Szabolcs, Katalin Patonay, Marietta Korózs, and Zsolt Zsófi. 2025. "The Combined Effect of Late Pruning and Apical Defoliation After Veraison on Kékfrankos (Vitis vinifera L.)" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121450

APA StyleVillangó, S., Patonay, K., Korózs, M., & Zsófi, Z. (2025). The Combined Effect of Late Pruning and Apical Defoliation After Veraison on Kékfrankos (Vitis vinifera L.). Horticulturae, 11(12), 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121450