Abstract

Epigenetic modifications are emerging as key regulators of plant stress responses. However, their role in eggplant (Solanum melongena)–western flower thrips (WFTs; Frankliniella occidentalis) interactions remains elusive. WFTs cause substantial economic losses in eggplant cultivation worldwide. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying eggplants’ defense is critical for developing resistant varieties. We investigated the function of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) in modulating the early transcriptional reprogramming of eggplants during WFT infestation. We performed ChIP-seq and RNA-seq on eggplant leaves at an early stage of WFT infestation to elucidate the epigenetic landscape and associated gene expression alterations. ChIP-seq analysis showed that genome-wide enrichment of H3K27me3 was mainly at the transcription start sites, with a notable decrease in WFT-infested plants. Concurrently, RNA-seq analysis identified 2822 genes that were upregulated following WFT infestation. Many of these genes associated with abscisic acid, jasmonic acid, and salicylic acid pathways were upregulated, underscoring their central role in early plant defense. Integrated analysis revealed six genes with decreased H3K27me3 levels and concurrent upregulation, potentially involved in ABA and JA signaling. Thus, removal of the repressive H3K27me3 mark may facilitate the transcriptional activation of early defense genes in eggplants that are crucial in their response to insect herbivory.

Keywords:

ChIP-seq; RNA-seq; H3K27me3; abscisic acid; jasmonic acid; eggplant; Frankliniella occidentalis 1. Introduction

The coevolution of plants and herbivorous insects has persisted for at least 385 million years [1]. Plants respond to insect attacks via complex and dynamic defense systems, activating immune responses. Plants recognize specific molecular patterns using receptors/sensors upon insect attack, triggering processes such as Ca2+ influxes, kinase cascades, reactive oxygen species production, phytohormone signaling pathway activation, upregulation of defense-related genes, and biosynthesis of defense-associated metabolites [2,3,4]. This inducible defense mechanism allows plants to conserve energy by synthesizing defense compounds only when necessary [3,5]. In eukaryotic cells, chromatin structure regulates gene expression, with histone post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, or ubiquitination at histone amino acid tails, altering the chromatin structure and accessibility. This aids plants in rapidly adapting to short-term environmental alterations [6,7,8,9]. Typically, methylation regulates transcriptional activation and repression, whereas histone acetylation is linked to transcriptional activation [10,11,12,13]. However, research on the role of histone modifications in plant responses to herbivorous insects is limited.

Increasing evidence suggests that trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3), a highly conserved repressive epigenetic mark, is prevalent in plant genomes. It plays a crucial role in repressing gene transcription [14,15,16,17], thereby influencing plant development and responses to environmental stress [18,19,20,21,22]. For example, under abiotic stress, reduced WD40-repeat proteins, Multicopy Suppressor of IRA1 (MSI1) expression or transcriptional regulator EMBRYONIC FLOWER 1 (EMF1) activity enhances salt tolerance by upregulating H3K27me3 targets, including ABA receptor genes and ABA-responsive genes [22,23,24]. The well-known phenomenon of vernalization further demonstrates the importance of this mark: low-temperature treatment promotes PcG-mediated H3K27me3 deposition, leading to epigenetic silencing of the major flowering repressor FLC and thereby facilitating flowering in Arabidopsis [25,26]. H3K27me3 is also involved in nutrient stress responses. To emphasize, under high nitrogen conditions, HIGH NITROGEN INSENSITIVE 9 (HNI9) suppresses the expression of the NO3− transporter, NRT2.1, in roots, with this suppression linked to H3K27me3 enrichment at the NRT2.1 locus [27]. Moreover, H3K27me3 participates extensively in biotic stress responses. Overexpression of rice JMJ705 reduces H3K27me2/3 levels, preferentially activating defense-related genes marked by H3K27me3 and improving resistance to the pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae [28]. Similarly, both H3K27me3 and H3K9me2 can suppress pathogen-induced programmed cell death, highlighting the key role of histone modifications in plant immunity [20]. In Arabidopsis mutants with reduced H3K27me3 levels, expression of the transcription factors ANAC019 and ANAC055, along with their target genes, is increased, thereby improving resistance to aphids, Myzus persicae [29]. Despite extensive studies on H3K27me3 abiotic and pathogen stress, its role in plant defense against herbivorous insects remains poorly understood.

Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.), a commercially significant crop in the Solanaceae family, is widely cultivated and consumed [30,31,32]. The western flower thrips (WFTs), Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), is a highly polyphagous agricultural pest characterized by its small size, short life cycle, high reproductive rate, and capacity to transmit plant viruses such as tomato spotted wilt virus. It causes substantial damage to fruits, vegetables, flowers, and other economically important crops across the globe [32,33,34]. In this study, we conducted a comparative analysis of histone modifications and transcriptional changes in eggplant leaves at the early stage of adult WFT infestation. By integrating ChIP-seq and RNA-seq analyses, we comprehensively characterized the dynamics of transcriptional regulation associated with H3K27me3 histone modifications in eggplant during early infestation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Cultivation

Eggplant (S. melongena L. cv. ‘Hangqie 1’) seeds were obtained from Hangzhou Sanjiang Seed Industry Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China), which were then surface-sterilized with 5% (v/v) NaClO for 15 min, followed by three rinses with distilled water. Subsequently, the sterilized seeds were pre-imbibed in darkness in distilled water for 48 h and transferred to a seed tray for a 10-day incubation period in a constant temperature incubator (24 °C for 14 h and 22 °C for 10 h). Upon germination, the seedlings were moved to a hydroponic tank for cultivation for 18 days, as described by Zheng et al. [32].

2.2. Insect Rearing and Treatment

WFTs were reared on broad beans (Vicia faba) at the Institute of Plant Protection, Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, under controlled conditions of 27 °C, a photoperiod of 14:10 (L:D) h, 65 ± 5% RH, and a light intensity of 4800 lx [32].

2.3. ChIP-Seq

After an 18-day culture period, plant leaves were exposed to female adults of WFTs for 3 h. Subsequently, the leaves were collected for co-immunoprecipitation [35] using H3K27me3 antibodies (Diagenode, Liege, Belgium), with a minimum of 15 plants per replicate. Initially, the leaves were fixed with 1% formaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), DNA was fragmented to a size of 100–400 bp, and 5% was extracted as input, whereas the remainder was used for immunoprecipitation. DNA was purified from input and immunoprecipitated DNA using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and processed for library construction with the NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). The concentration was measured using Qubit, whereas purity and library size were evaluated with Qseq400. Libraries were sequenced using Novaseq PE150 mode. Raw reads were filtered using Trimmomatic [36] to obtain clean data, which were subsequently aligned to the reference genome [37] using the BWA-MEM algorithm.

Peak calling was conducted using MACS2 with the narrow option and a filtering threshold of q value < 0.05 [38]. Following this, peak files from each sample were merged using DeepTools (3.4.3), and DESeq2 (1.16.0) was used to identify the differentially accessible peaks. Regions were classified as differentially accessible if the absolute log2 fold change was ≥0.58 with a p-value < 0.05. The tool bedtools [39] was used to assess the relationships and annotate the peak regions with different functional regions. Furthermore, peak-associated genes underwent Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis for functional annotation [40,41].

2.4. RNA-Seq

Eggplant leaves were exposed to female adults of WFTs for 3 h and were subsequently sampled for total RNA extraction using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Each group included three biological replicates, each comprising leaves pooled from six independently grown plants. The RNA concentration and purity were evaluated using a Nanodrop2000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), whereas RNA integrity was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The cDNA library was prepared using the NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and purified with the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, MA, USA). Sequencing was conducted on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform in the PE150 mode. Quality control of the raw reads was implemented, and GO and KEGG analyses were performed following the methodologies used in the ChIP-seq analysis.

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

RT-qPCR was conducted to validate the differential expression of the selected genes. Total RNA was extracted from the treated leaves using EastepTM Total RNA Extraction Kit (Progema, Shanghai, China). The TransStart® Uni All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (One-Step gDNA Removal) (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) was utilized to synthesize the cDNA from 1 µg of RNA for qPCR analysis with the Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) [32]. SmActin (accession number: GU984779.1) was utilized as an internal control to evaluate qPCR amplification [32,42]. Supplemental Table S4 lists the primers used. Real-time PCR reactions included 5 µL of 2 × Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix, 0.3 µL (10 µM) of each specific primer, 1 µL of cDNA, and RNase-free water to a final volume of 10 µL. Thermal cycling conditions comprised an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60–64 °C for 30 s. Three biological replicates of each treatment were assessed via RT-qPCR analyses, and the changes in gene expression were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method with normalization [43].

2.6. ChIP-qPCR

After conducting co-immunoprecipitation as described by Kaufmann et al. [35], input-DNA and IP-DNA were extracted, diluted, and subjected to RT-qPCR analysis to quantify DNA enrichment by H3K27me3 antibodies relative to the input DNA in the treatment (3 h) and control (0 h) groups. Supplementary Table S4 lists the primers used for ChIP-qPCR analysis.

2.7. Data Analysis

Statistical and analytical analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Mean differences in RT-qPCR and ChIP-qPCR were assessed using Student’s t-test and Tukey’s HSD test.

3. Results

3.1. H3K27me3 Modification Changed in Early WFT-Infested Eggplants

We conducted ChIP-Seq of H3K27me3 at 3 h after WFT infestation to investigate the changes in H3K27me3 modification in the early WFT-infested eggplants and its subsequent effects on gene expression. After the removal of short and low-quality sequences, we evaluated the quality using Q20 and Q30 metrics. The Q20 ratios ranged from 98.69% to 98.85%, whereas the Q30 ratios varied from 95.52% to 96.04%, indicating a high level of detection quality (Table S1). The mapped rate fluctuated between 99.41% and 99.91%, while the unique mapped rate ranged from 83.69% to 93.98%, thereby satisfying the criteria for further analyses (Table 1).

Table 1.

H3K27me3 ChIP-Seq sequencing clean reads alignment statistics in eggplant leaves under both uninfested and infested with western flower thrips (WFT).

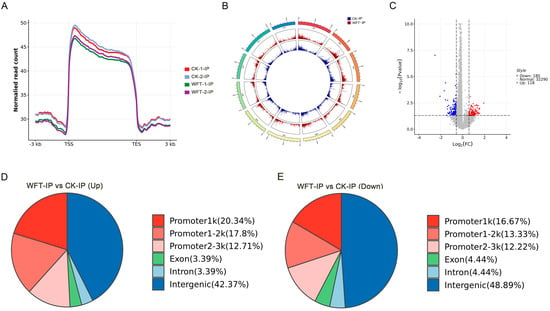

H3K27me3 enrichment near the transcription start site (TSS) regions in the CK_IP and WFT_IP groups was observed. Compared to CK_IP, the average signal value of H3K27me3 at WFT_IP sites reduced (Figure 1A). A Circos plot showed the changes in H3K27me3-binding peaks throughout the genome in CK_IP and WFT_IP of S. melongena (Figure 1B). In comparison to CK_IP, WFT_IP showed 118 upregulated and 180 downregulated peaks (Figure 1C). The identified peaks were classified into different regions, including promoter1k, promoter1-2k, promoter2-3k, exon, intron, and intergenic regions. Notably, the proportion of the promoter functional domains in the upregulated peaks following WFT feeding was higher than that in the downregulated peaks, whereas the proportion of exon, intron, and intergenic regions in the downregulated peaks following WFT feeding was greater than that in the upregulated peaks, especially in the intergenic regions, which demonstrated a 6.52% increase (Figure 1D,E).

Figure 1.

Genome-wide distribution of H3K27me3 in S. melongena. Peak signal distribution plots (A), Circos plot across the genome (B), volcano plot (C), and peak annotated abundance (D,E) for H3K27me3 in eggplant leaves under both uninfested and infested with western flower thrips (WFT). Note: The x-axis represents normalized gene coordinates, with the transcription start site (TSS) and transcription end site (TES) labeled. The interval from −3.0 to 3.0 corresponds to 3 kb upstream of the TSS and 3 kb downstream of the TES, respectively. The y-axis shows the average normalized signal intensity at each position. (A) Promoter regions (1 kb, 1–2 kb, and 2–3 kb) are defined as the intervals upstream of the TSS and downstream of the TES. Exon and Intron denote the respective gene regions, while Intergenic regions are defined as all other areas. The pie chart displays the proportion of peaks annotated to each functional category, with different colors representing different functional regions (D,E). CK-IP: ChIP-seq group uninfested by WFT; WFT-IP: ChIP-seq group infested by WFTs for 3 h.

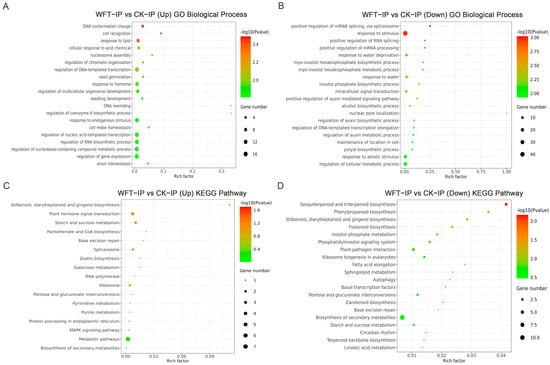

GO annotation analysis revealed that genes situated near the H3K27me3 peaks showed substantial upregulation after WFT feeding, mainly linked to DNA conformation change, cell recognition, response to lipid, and cellular response to acid chemical. Conversely, genes near the downregulated peaks were primarily involved in the positive regulation of mRNA/RNA splicing, response to stimulus, positive regulation of mRNA processing, and response to water deprivation (Figure 2A,B). KEGG pathway analysis indicated that genes near the upregulated peaks after WFT feeding were enriched in plant hormone signal transduction and starch and sucrose metabolism as well as in pathways, such as stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid, and gingerol biosynthesis. Contrastingly, genes near the downregulated peaks were predominantly associated with pathways, including sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid, and gingerol biosynthesis, and flavonoid biosynthesis (Figure 2C,D).

Figure 2.

GO (A,B) and KEGG (C,D) enrichment analyses of genes associated with H3K27me3 peaks in eggplant leaves under uninfested and WFT-infested conditions. CK-IP: ChIP-seq group uninfested by WFT; WFT-IP: ChIP-seq group infested by WFTs for 3 h.

3.2. Altered Hormone Signaling in Eggplants Responding to Early WFT Infestation

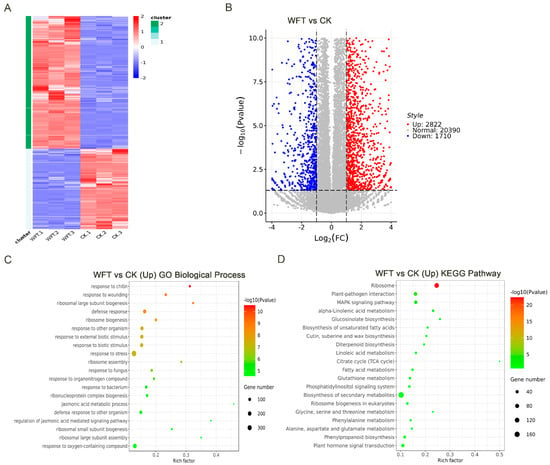

Transcriptome sequencing was conducted 3 h after WFT infestation to investigate the relationship between the changes in H3K27me3 modification in early WFT-infested eggplants and gene expression. The quality of the sequencing data was evaluated using Q20 and Q30 metrics, with Q20 ratios approximately at 98% and Q30 ratios approximately at 95%, indicating high detection quality (Table S2). The unique mapped rate ranged from 94.11% to 95.52%, which met the criteria for further analyses (Table S3). Differential gene expression levels and quantities among multiple samples were elucidated through heatmap clustering analysis and volcano plot visualization (q-value < 0.05, fold change > 2). The number of genes upregulated following WFT feeding was 1.65-fold higher than that of downregulated genes, indicating that the majority of genes are upregulated during the early stages of infestation (Figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

Transcriptome profiling of eggplant leaves infested by WFT. A heatmap (A) and volcano plot (B), illustrate differences in gene expression between WFT and CK groups. GO (C) and KEGG (D) enrichment analyses show functional categories of up-regulated genes in WFT compared with CK. CK, the transcriptome group uninfested by WFT; WFT, the transcriptome group infested by WFTs for 3 h.

GO annotation analysis indicated that the majority of genes were associated with stress responses, with notable enrichments in chitin, wounding, and defense responses, as well as ribosomal large subunit biogenesis (Figure 3C). KEGG pathway analysis showed that the ribosome pathway exhibited the most significant enrichment, followed by pathways associated with plant–pathogen interactions, MAPK signaling, and alpha-linolenic acid metabolism, among others (Figure 3D).

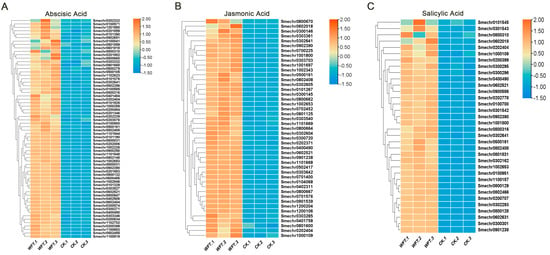

During insect infestations, hormone pathways play a critical role. Analysis of hormone-related pathways using GO biological process (p < 0.05) showed a significant upregulation of genes linked to abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), and salicylic acid (SA) pathways in the early WFT infestation stage. In particular, 64 genes that responded to ABA, 45 to JA, and 34 to SA were upregulated (Figure 4A–C). This suggests that ABA, JA, and SA signaling are likely crucial for eggplants in their defense against early WFT infestation.

Figure 4.

A heatmap was used to examine the variations in expression levels of ABA (A), JA (B), and SA (C) hormone pathway up-regulated genes between WFT and CK. CK, the transcriptome group uninfested by WFT; WFT, the transcriptome group infected by WFTs for 3 h.

3.3. Integrative Analysis of ChIP-Seq and RNA-Seq to Identify the Metabolic Pathway of Early WFT-Infested Eggplants

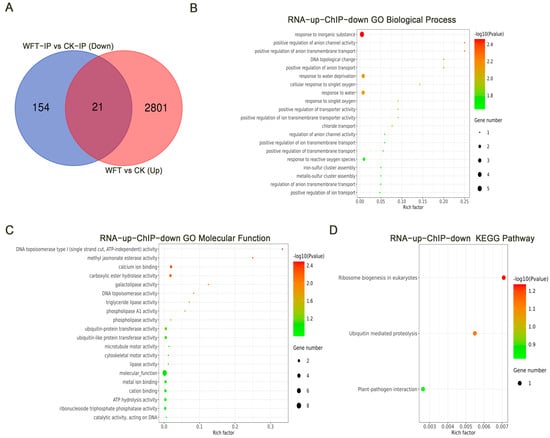

A Venn diagram was utilized to compare the 2822 upregulated genes identified via RNA-Seq after WFT infestation (Figure 3B) with 175 genes identified by H3K27me3 modification peak-down, showing 21 overlapping genes (Figure 5A). The shared genes underwent GO and KEGG analyses. GO biological process analysis indicated primary involvement in response to inorganic substances, positive regulation of anion channel activity, positive regulation of anion transmembrane transport, DNA topological changes, positive regulation of anion transport, and response to water deprivation (Figure 5B). GO molecular function analysis showed major participation in DNA topoisomerase type I (single-strand cut, ATP-independent) activity, methyl jasmonate esterase activity, calcium ion binding, carboxylic ester hydrolase activity, and galactolipase activity (Figure 5C). KEGG pathway analysis revealed enrichment in ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, and plant–pathogen interaction (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

The Venn diagram (A), GO biological process (B), GO molecular function (C), and KEGG pathway (D) illustrate the joint analysis of genes upregulated in the post-WFT infestation transcriptome and genes exhibiting H3K27me3 modification peaks-down in ChIP-seq following WFT infestation. CK-IP, the ChIP-seq group uninfested by WFT; WFT-IP, the ChIP-seq group infested by WFTs for 3 h. CK, the transcriptome group uninfested by WFT; WFT, the transcriptome group infested by WFTs for 3 h.

3.4. Identifying Upregulated Differentially Expressed Genes with Reduced H3K27me3 in Early WFT-Infested Eggplants

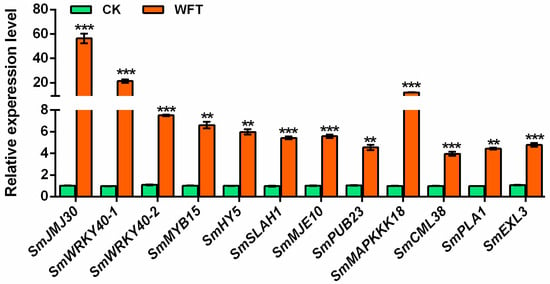

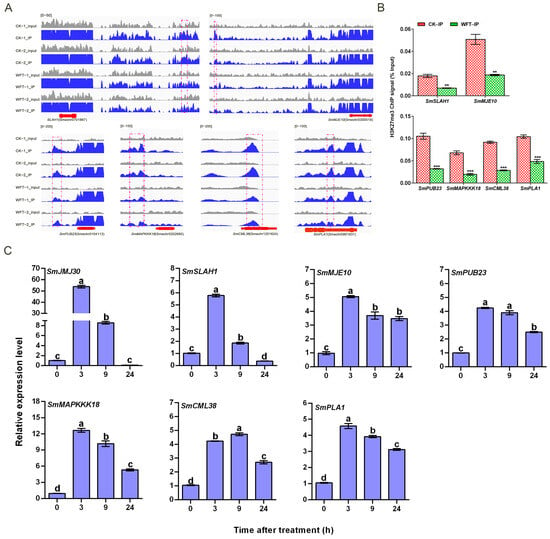

Twelve upregulated genes identified via RNA-Seq post WFT infestation (Figure 3B) were selected for RT-qPCR validation, confirming their expression trends consistent with the transcriptome data. Notably, histone demethylase SmJMJ30 showed the highest expression level, 55.47-fold higher than the control, followed by SmWRKY40-1 and SmMAPKKK18, with expression levels of other genes at least four times higher than the control (Figure 6). Six genes with reduced H3K27me3 were selected: SmSLAH1, SmMJE10, SmPUB23, SmMAPKKK18, SmCML38, and SmPLA1. Among these, SLAH1 is associated with ABA and MeJA [44]. Additionally, PLA and MJE are associated with JA synthesis and its active forms [45,46,47], whereas PUB23 and MAPKKK18 are linked to ABA signaling [48,49]. CML38 is broadly involved in different stress responses [50,51]. The differential peak distributions of these genes differed, with SmSLAH1, SmMJE10 and SmPUB23 situated upstream of the TSS, and SmMAPKKK18, SmCML38, and SmPLA1 located downstream of the TSS (Figure 7A). Meanwhile, H3K27me3 enrichment in the central regions of the differential peaks of these six genes was validated through ChIP-qPCR experiments, confirming a reduction in H3K27me3 enrichment levels following WFT feeding (Figure 7B). Furthermore, except for SmCML38, the expression levels of six genes peaked at 3 h after WFT feeding, especially for SmJMJ30 (Figure 7C). These findings indicate a negative correlation between the H3K27me3 enrichment level and gene expression levels potentially involved in ABA and JA signaling pathways in eggplants subjected to WFT infestation.

Figure 6.

qPCR was used to verify the expression levels of twelve genes in the transcriptome of the leaves of eggplants inoculated with the WFT. CK, the group uninfested by WFT; WFT, the group infested by WFTs for 3 h., Values are the mean ± SE (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test: ** p < 0.01, or *** p < 0.001.

Figure 7.

Six gene profiles of H3K27me3 modification and seven gene dynamic expressions. (A) IGV visualization of peaks of SmSLAH1, SmMJE10, SmPUB23, SmMAPKKK18, SmCML38, and SmPLA1 by H3K27me3, (B) ChIP-qPCR assay was conducted to analyze the alterations in H3K27me3 levels of SmSLAH1, SmMJE10, SmPUB23, SmMAPKKK18, SmCML38, and SmPLA1 with WFT infestation for 3 h (n = 3). (C) Analysis of dynamic expressions of seven genes. CK-IP, the ChIP-seq group uninfested by WFT; WFT-IP, the ChIP-seq group infested by WFTs for 3 h. Values are the mean ± SE (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test: ** p < 0.01, or *** p < 0.001. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences, as determined by one-way ANOVA by Tukey HSD test (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Our study provides the first genome-wide analysis of H3K27me3 dynamics in eggplants during their early defense response to the WFT. We observed a decline in the genome-wide distribution of H3K27me3 in eggplants following early infestation by WFTs by globally analyzing histone modifications and transcriptome. An inverse relationship with gene transcription was noted. The several genes identified were part of intricate regulatory networks, connecting their expression to the fluctuations in H3K27me3 levels in eggplants infested by WFT.

The role of H3K27me3 as a key mark of facultative heterochromatin and gene silencing is well-established across eukaryotes, from plants to animals [14,16,17,52]. Our findings are consistent with this paradigm, revealing that in unchallenged eggplants, several defense-related genes have H3K27me3 and are maintained in a transcriptionally repressed state, with H3K27me3 enrichment near the TSS regions (Figure 1). This “poised” or silenced state is likely an adaptive strategy to conserve energy and resources in the absence of biotic threats [53,54]. Upon perception of WFT feeding, the targeted removal of this repressive mark enables rapid induction of critical early defense genes. The genes we identified as being regulated by this mechanism are involved in canonical plant defense pathways, such as sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis, and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, and others (Figure 2). This is similar to the primary pathway of histone modification alterations reported in recent publications on insect pest stress [9].

Changes in hormone-related pathways have been shown to occur in rice plants infested by different pests, including Spodoptera frugiperda [9], Chilo suppressalis [53], and Nilaparvata lugens [55]. Moreover, our previous research has highlighted the criticality of hormone pathways, particularly the JA and SA pathways, in the interaction between eggplants and WFTs [32]. Notably, during the early stages of pest infestation, ABA can promote JA accumulation [56,57,58]. Additionally, ABA can collaborate with SA to mitigate microbial invasion [59]. Our RNA-Seq findings are consistent with these studies, revealing that genes associated with the ABA, JA, and SA pathways were altered in eggplants after being fed on by WFTs for 3 h (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Meanwhile, the integrated analysis of RNA-seq and ChIP-seq showed that the GO pathways enriched by RNA-up and ChIP-down genes primarily involved response to inorganic substances, anion channels, water deprivation, methyl jasmonate esterase activity, calcium ion binding, and carboxylic ester hydrolase activity (Figure 5B,C). The KEGG pathways were mainly linked to ribosome biogenesis, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, and plant-pathogen interaction (Figure 5D). Additionally, these pathways were associated with hormone signaling, as evidenced by the identification of the genes SmSLAH1, SmMJE10, SmPUB23, SmMAPKKK18, SmCML38, and SmPLA1 (Figure 6 and Figure 7). SLAH1 belongs to the S-type anion channel protein. Anion channels act as master switches of stress responses and are stimulated in the guard cells by ABA and MeJA, which results in stomatal closure and decreases transpirational water loss, thereby resisting stress [44,60,61]. Meanwhile, anion channels may also play a role in achieving basal resistance or innate immunity. When plasma membrane receptors recognize microbe-associated molecular patterns, they induce innate immune responses. Following the receptor complex activation, defense gene expression is induced via the MAP kinase cascade [44,62]. The activation process of the S-type anion channels in these processes depends on hormones, MAP kinases, OST1/SnRK2.6/SnRK2 protein kinases, and CPK protein kinases [44,63]. Phospholipase A1, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of phospholipids [64], is also an acyl hydrolase, serving as the initial enzyme in JA synthesis [45,65]. AtPLAI in Arabidopsis is involved in JA production and resistance to B. cinerea [66]. Methyl jasmonate (MeJA)-specific methyl esterase enhances the expression of JA-responsive genes by converting MeJA to JA [47,67]. In summary, these genes appear to be associated, through the reduction in H3K27me3 modification, with early pest response for rapid adaptation to biotic stress.

H3K27me3 deposition is catalyzed by the polycomb repressive complex 2, whose core components are highly conserved in plants [68]. The mark is subsequently recognized by reader proteins like HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN 1, which helps maintain the repressive state [69]. Conversely, Jumonji C (JmjC) domain-containing histone demethylases remove H3K27me3 [28]. Although our study did not directly assay JmjC enzyme activity, our RNA-seq data and qRT-PCR showed differential expression of JmjC demethylases JMJ 30 upon thrips feeding (Figure 3, Figure 6 and Figure 7C). This suggests that the regulation of the epigenetic modifiers is a central component of the defense response.

This study has some limitations. Our analyses provide a strong correlation between H3K27me3 removal and gene activation. However, they do not establish direct causality. The data represent a snapshot of the early defense response at a specific time point; the epigenetic landscape is likely to continue evolving at later infestation and recovery stages [9]. The interaction between H3K27me3 and other epigenetic modifications, such as H3K27ac, often shows a reciprocal association, wherein the existence of one is inversely associated with the presence of the other [70]. This study opens up multiple exciting avenues for future research. Functionally validating the role of the identified epigenetic regulators should be prioritized. Using methods, such as virus-induced gene silencing or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing, to knock down or knock out JMJ30 in eggplants would facilitate direct testing of their impact on H3K27me3 levels and, consequently, on resistance to WFT.

In conclusion, our study established H3K27me3 as a crucial and dynamic regulator of early defense gene expression in eggplants against WFT. We provide a foundational genome-wide map of these epigenetic alterations, linking the removal of a repressive histone mark to the activation of a coordinated immune response. These results advance our knowledge of plant-insect interactions, underscoring the sophisticated epigenetic strategies plants use to defend themselves.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11101269/s1, Table S1: H3K27me3 ChIP-Seq sequencing quality control statistics in eggplant leaves under both uninfested and infested with western flower thrips (WFT); Table S2: Transcriptomes sequencing quality control statistics in eggplant leaves under both uninfested and infested with WFT; Table S3: Statistical of the alignment of transcriptomes clean reads in eggplant leaves under both uninfested and infested with WFT; Table S4: RT-qPCR and ChIP-qPCR primers for differentially expressed genes following 3 h WFT infestation in eggplant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and Y.Z.; data curation, L.H. and Y.Z.; resources, L.H. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. and H.W.; investigation, L.H. and H.T.; Methodology, Y.Z., L.H. and H.T.; software, Y.Z. and L.H.; validation, L.H. and Q.L.; visualization, Y.Z.; writing—original draft, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and H.W.; project administration, Y.Z. and H.W.; supervision, H.W. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the Basic Research Special Foundation of Public Research Institutes of Fujian Province, China (grant number 2022R1024009); the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (grant number 2025J01413); the Basic Research Projects of Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China (grant numbers ZYTS202412); and the Fujian Provincial Science and Technology Project (grant number 2023L3021).

Data Availability Statement

All data are within the article and Supplementary Materials. The ChIP-seq and RNA-seq raw data has been submitted to the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA1335614.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WFT | western flower thrips |

| PTMs | post-translational modifications |

| H3K27me3 | histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation |

References

- Labandeira, C.C. A paleobiologic perspective on plant-insect interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013, 16, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatehouse, J.A. Plant resistance towards insect herbivores: A dynamic interaction. New Phytol. 2002, 156, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Baldwin, I.T. New insights into plant responses to the attack from insect herbivores. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2010, 44, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Lou, Y.R.; Tzin, V.; Jander, G. Alteration of plant primary metabolism in response to insect herbivory. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.; Song, Y.; Long, J.; Wang, R.; Baerson, S.R.; Pan, Z.; Zhu-Salzman, K.; Xie, J.; Cai, K.; Luo, S.; et al. Priming of jasmonate-mediated antiherbivore defense responses in rice by silicon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E3631–E3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzarides, T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 2007, 128, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.; Daujat, S.; Schneider, R. Lateral thinking: How histone modifications regulate gene expression. Trends Genet. 2016, 32, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilker, M.; Schmülling, T. Stress priming, memory, and signalling in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Guo, R.; Li, Q.; Lin, T.; Wu, Z.; Gao, N.; Wu, F.; Tong, L.; Zeng, R.; Song, Y.; et al. Rice responds to Spodoptera frugiperda infestation via epigenetic regulation of H3K9ac in the jasmonic acid signaling and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathways. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allfrey, V.G.; Faulkner, R.; Mirsky, A.E. Acetylation and methylation of histones and their possible role in the regulation of RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1964, 51, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazian, M.D.; Grunstein, M. Functions of site-specific histone acetylation and deacetylation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, F.; Cui, X.; Cao, X. Histone methylation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, M.; Seki, M. Histone modifications form epigenetic regulatory networks to regulate abiotic stress response. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Clarenz, O.; Cokus, S.; Bernatavichute, Y.V.; Pellegrini, M.; Goodrich, J.; Jacobsen, S.E. Whole-genome analysis of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.A.; Tanizawa, Y.; Galik, B.; Wang, N.; Ito, T.; Mochizuki, T.; Akimcheva, S.; Bowman, J.L.; Cognat, V.; Maréchal-Drouard, L.; et al. Chromatin organization in early land plants reveals an ancestral association between H3K27me3, transposons, and constitutive heterochromatin. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 573–588.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Cao, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X.; Deng, X.W.; He, H.; Qian, W. Conserved H3K27me3-associated chromatin looping mediates physical interactions of gene clusters in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1966–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hure, V.; Piron-Prunier, F.; Yehouessi, T.; Vitte, C.; Kornienko, A.E.; Adam, G.; Nordborg, M.; Déléris, A. Alternative silencing states of transposable elements in Arabidopsis associated with H3K27me3. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, E.S.; Xu, Y.; Ito, T. Dynamics of H3K27me3 methylation and demethylation in plant development. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e1027851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, M.; Jacob, Y.; Susaki, D.; LeBlanc, C.; Buendía, D.; Axelsson, E.; Kawashima, T.; Voigt, P.; Boavida, L.; Becker, J.; et al. Targeted reprogramming of H3K27me3 resets epigenetic memory in plant paternal chromatin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvořák Tomaštíková, E.; Hafrén, A.; Trejo-Arellano, M.S.; Rasmussen, S.R.; Sato, H.; Santos-González, J.; Köhler, C.; Hennig, L.; Hofius, D. Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 and KRYPTONITE regulate pathogen-induced programmed cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 2003–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, J.; Cook, D.E. Histone modification dynamics at H3K27 are associated with altered transcription of in planta induced genes in Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, G. Dynamics of H3K27me3 modification on plant adaptation to environmental cues. Plants 2021, 10, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, L.; Liu, M.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Chen, L.F.; Fletcher, J.C.; Sung, Z.R. EMBRYONIC FLOWER1 and ULTRAPETALA1 act antagonistically on Arabidopsis development and stress response. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 812–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, S.; Derkacheva, M.; Ramström, M.; Kralemann, L.; Bergquist, J.; Hennig, L. The WD40 domain protein MSI1 functions in a histone deacetylase complex to fine-tune abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Dean, C. Storing memories: The distinct phases of Polycomb-mediated silencing of Arabidopsis FLC. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019, 47, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, G.; Schulten, A.; Dean, C.; Howard, M. Digital paradigm for Polycomb epigenetic switching and memory. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 61, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widiez, T.; El Kafafi, S.; Girin, T.; Berr, A.; Ruffel, S.; Krouk, G.; Vayssières, A.; Shen, W.H.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Gojon, A.; et al. High nitrogen insensitive 9 (HNI9)-mediated systemic repression of root NO3- uptake is associated with changes in histone methylation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13329–13334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, X.; Zhong, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, S.; Zhou, D.X. Jumonji C domain protein JMJ705-mediated removal of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation is involved in defense-related gene activation in rice. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4725–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Prado, J.S.; Latrasse, D.; Rodriguez-Granados, N.Y.; Huang, Y.; Manza-Mianza, D.; Brik-Chaouche, R.; Jaouannet, M.; Citerne, S.; Bendahmane, A.; Hirt, H.; et al. The Polycomb protein LHP1 regulates Arabidopsis thaliana stress responses through the repression of the MYC2-dependent branch of immunity. Plant J. 2019, 100, 1118–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalloo, G. Eggplant: Solanum Melongena L. In Genetic Improvement of Vegetable Crops; Kallo, G., Bergh, B.O., Eds.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 587–604. [Google Scholar]

- Mauceri, A.; Bassolino, L.; Lupini, A.; Badeck, F.; Rizza, F.; Schiavi, M.; Toppino, L.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Rotino, G.L.; Sunseri, F. Genetic variation in eggplant for nitrogen use efficiency under contrasting NO3− supply. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shi, S.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Y.; Lin, S.; Tian, H.; Huang, L.; Wei, H. Nitrogen deficiency enhances eggplant defense against western flower thrips via the induction of the jasmonate pathway. Plants 2024, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, S.R.; Gao, Y.; Kirk, W.D.J.; Hoddle, M.S.; Leiss, K.A.; Funderburk, J.E. Invasion biology, ecology, and management of western flower thrips. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xing, Z.; Ma, T.; Xu, D.; Li, Y.; Lei, Z.; Gao, Y. Competitive interaction between Frankliniella occidentalis and locally present thrips species: A global review. J. Pest. Sci. 2021, 94, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, K.; Muiño, J.M.; Østerås, M.; Farinelli, L.; Krajewski, P.; Angenent, G.C. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) of plant transcription factors followed by sequencing (ChIP-SEQ) or hybridization to whole genome arrays (ChIP-CHIP). Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Hu, T.; Hu, H.; Bao, C. A high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly reveals genetics for important traits in eggplant. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.M. Improved peak-calling with MACS2. BioRxiv 2018. Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draghici, S.; Khatri, P.; Tarca, A.L.; Amin, K.; Done, A.; Voichita, C.; Georgescu, C.; Romero, R. A systems biology approach for pathway level analysis. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Ren, L.; Lian, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. Novel insight into the mechanism underlying light-controlled anthocyanin accumulation in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Plant Sci. 2016, 249, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelfsema, M.R.; Hedrich, R.; Geiger, D. Anion channels: Master switches of stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, S.; Kawai-Oda, A.; Ueda, J.; Nishida, I.; Okada, K. The DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCIENCE gene encodes a novel phospholipase A1 catalyzing the initial step of jasmonic acid biosynthesis, which synchronizes pollen maturation, anther dehiscence, and flower opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Baldwin, I.T. Methyl jasmonate-elicited herbivore resistance: Does MeJA function as a signal without being hydrolyzed to JA? Planta 2008, 227, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Lin, H.; Lan, S.; Jia, Q.; Chen, X.; Guo, H.; Chen, F. VvMJE1 of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera) VvMES methylesterase family encodes for methyl jasmonate esterase and has a role in stress response. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 102, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, M.; Zafar, S.A.; Fang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, X. Arabidopsis E3 ubiquitin ligases PUB22 and PUB23 negatively regulate drought tolerance by targeting ABA receptor PYL9 for degradation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajdel-Zielińska, M.; Janicki, M.; Marczak, M.; Ludwików, A. Arabidopsis HECT and RING-type E3 ligases promote MAPKKK18 degradation to regulate abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell Physiol. 2024, 65, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokdarshi, A.; Conner, W.C.; McClintock, C.; Li, T.; Roberts, D.M. Arabidopsis CML38, a calcium sensor that localizes to ribonucleoprotein complexes under hypoxia stress. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 1046–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Zhang, C.; Jin, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S. Calcium disrupts CML38/WRKY46-NAC187-CCR cascade to inhibit the formation of lignin-related physiological disorders in pear fruit. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 3478–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Shen, L.; Cheng, A.S.; Ahmed, S.; Boumber, Y.; Charo, C.; Yamochi, T.; Urano, T.; Furukawa, K.; Kwabi-Addo, B.; et al. Gene silencing in cancer by histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation independent of promoter DNA methylation. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Qin, N.; Xu, K.; Zeng, R.; Liu, J.; Song, Y. Nitrogen supply alters rice defense against the striped stem borer Chilo suppressalis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 691292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, Z.; Cui, F.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Niu, Y.; et al. Epigenetic modifications regulate cultivar-specific root development and metabolic adaptation to nitrogen availability in wheat. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Kang, H.; Sun, Z.; Pan, G.; Wang, Q.; Hu, J.; et al. A gene cluster encoding lectin receptor kinases confers broad-spectrum and durable insect resistance in rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, S.T.; Baldwin, I.T.; Galis, I. The HERBIVORE ELICITOR-REGULATED1 gene enhances abscisic acid levels and defenses against herbivores in Nicotiana attenuata plants. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 2106–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, I.A.; Verhage, A.; Schuurink, R.C.; Watt, L.G.; Pieterse, C.M.; Van Wees, S.C. Onset of herbivore-induced resistance in systemic tissue primed for jasmonate-dependent defenses is activated by abscisic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanchi, P.; Marimuthu, M.; Venkatasamy, B.; Krish, K.K.; Sankarasubramanian, H.; Mannu, J. Phytohormonal signaling network and immune priming pertinence in plants to defend against insect herbivory. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.S.; Lakshmanan, V.; Caplan, J.L.; Powell, D.; Czymmek, K.J.; Levia, D.F.; Bais, H.P. Rhizobacteria Bacillus subtilis restricts foliar pathogen entry through stomata. Plant J. 2012, 72, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munemasa, S.; Oda, K.; Watanabe-Sugimoto, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Shimoishi, Y.; Murata, Y. The coronatine-insensitive 1 mutation reveals the hormonal signaling interaction between abscisic acid and methyl jasmonate in Arabidopsis guard cells. Specific impairment of ion channel activation and second messenger production. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1398–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, P.; Gahir, S.; Raghavendra, A.S. Abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure: An important component of plant defense against abiotic and biotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 615114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, T.; Tena, G.; Plotnikova, J.; Willmann, M.R.; Chiu, W.L.; Gomez-Gomez, L.; Boller, T.; Ausubel, F.M.; Sheen, J. MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 2002, 415, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantoja, O. Recent Advances in the Physiology of Ion Channels in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 463–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yao, Z.; Ruan, M.; Wang, R.; Ye, Q.; Wan, H.; Zhou, G.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, S.; Liu, C.; et al. The PLA Gene Family in Tomato: Identification, Phylogeny, and Functional Characterization. Genes 2025, 16, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtsclaw, R.E.; Mahmud, S.; Koo, A.J. Identification and characterization of GLYCEROLIPASE A1 for wound-triggered JA biosynthesis in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Plant Mol. Biol. 2024, 114, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Devaiah, S.P.; Pan, X.; Isaac, G.; Welti, R.; Wang, X. AtPLAI is an acyl hydrolase involved in basal jasmonic acid production and Arabidopsis resistance to Botrytis cinerea. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 18116–18128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.J.; Yoon, E.S.; Seo, J.S.; Kim, J.K.; Choi, Y.D. Characterization of a methyl jasmonate specific esterase in Arabidopsis. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2013, 56, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, D.; Primavesi, L.; Bishopp, A.; Roberts, G.; Doonan, J.; Jenuwein, T.; Goodrich, J. Silencing by plant Polycomb-group genes requires dispersed trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 4638–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turck, F.; Roudier, F.; Farrona, S.; Martin-Magniette, M.L.; Guillaume, E.; Buisine, N.; Gagnot, S.; Martienssen, R.A.; Coupland, G.; Colot, V. Arabidopsis TFL2/LHP1 specifically associates with genes marked by trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wei, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, T.; Guo, M.; Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Wang, M.; et al. Schlank orchestrates insect developmental transition by switching H3K27 acetylation to trimethylation in the prothoracic gland. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2401861121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).