Biomass Production and Volatile Oil Accumulation of Ocimum Species Subjected to Drought Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

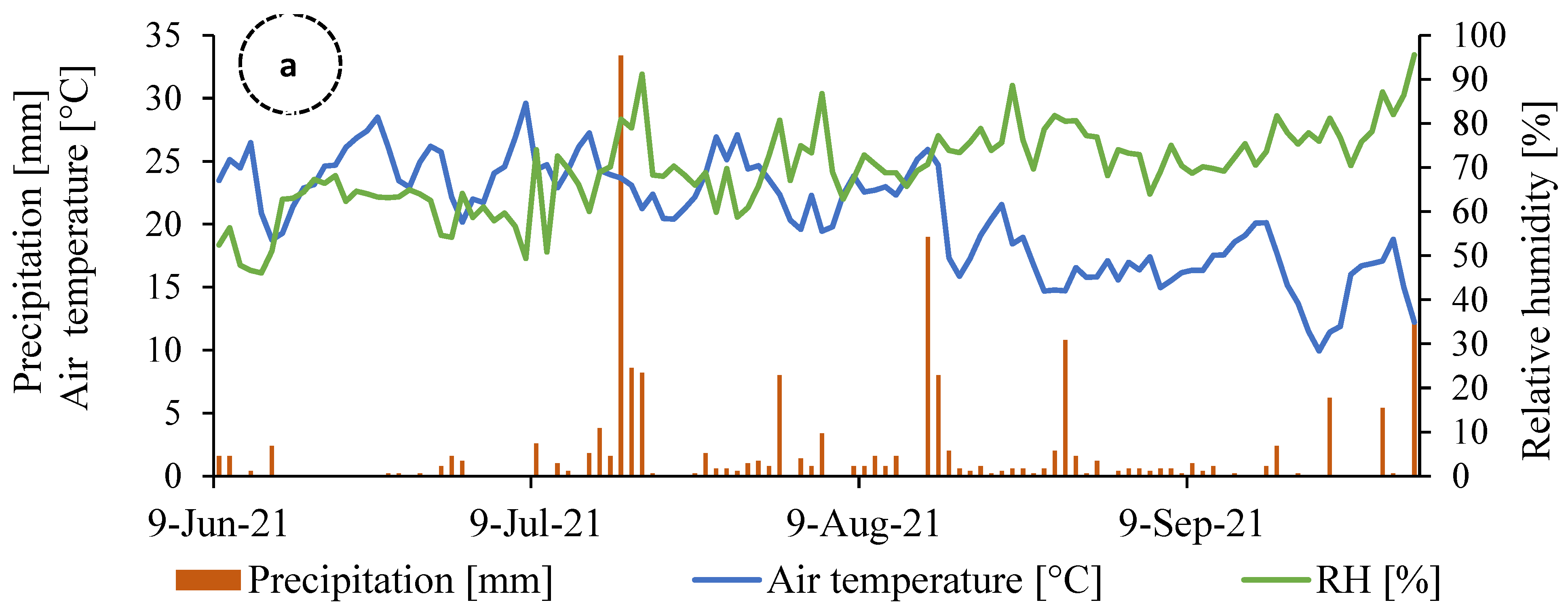

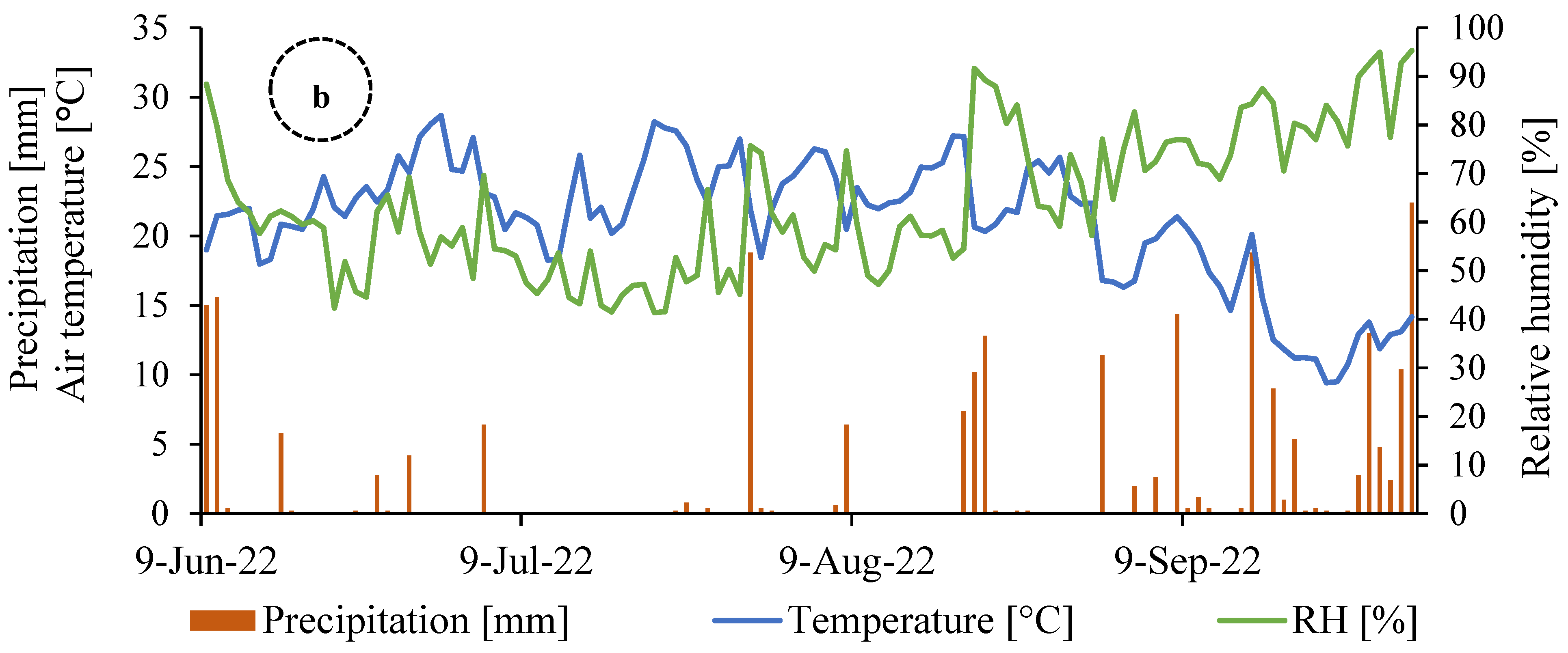

2.1. Experimental Site and Design

2.2. Measurement of Growth Parameters

2.3. Determination of Secondary Compounds

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Water Supply on Biomass Production

3.2. Effect of Water Supply on Essential Oil Production

3.3. Influence of Water Supply on Essential Oil Composition

3.4. Effect of Water Supply on Total Phenol Content and Antioxidant Capacity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalita, M.; Devi, N. A taxonomic review of the genus Ocimum L. (Ocimeae, Lamiaceae). Plant Sci. Today 2023, 10, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, A.; Harley, M.R.; Harley, M.M. Ocimum: An Overview of Classification and Relationships; Harwood Academic Publisher: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, D.A.; Balkwill, K. A new species of Ocimum (Lamiaceae) from Swaziland. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2004, 145, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Flora Online. Ocimum L. 2024. Available online: https://wfoplantlist.org/taxon/wfo-4000026511-2023-12?page=1 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Maddi, R.; Amani, P.; Bhavitha, S.; Gayathri, T.; Lohitha, T. A review on Ocimum species: Ocimum americanum L., Ocimum basilicum L., Ocimum gratissimum L. and Ocimum tenuiflorum L. Intern. J. Res. Ayurv. Pharm. 2019, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mulugeta, S.M.; Gosztola, B.; Radácsi, P. Diversity in morphology and bioactive compounds among selected Ocimum species. Biochem. Syst. Eco. 2024, 114, 104826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Singh, P.; Tripathi, N.N. Chemistry and bioactivities of essential oils of some Ocimum species: An overview. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, T.P.; Dholakia, B.B.; Giri, A.P. A glance at the chemo diversity of Ocimum species: Trends, implications, and strategies for the quality and yield improvement of essential oil. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 879–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, S.M.; Pluhár, Z.; Radácsi, P. Phenotypic variations and bioactive constituents among selected Ocimum species. Plants 2024, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, E.M.; Niemeyer, E.D. Variations in phenolic composition and antioxidant properties among 15 basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) cultivars. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajomo, E.M.; Aing, M.S.; Ford, L.S.; Niemeyer, E.D. Chemotyping of commercially available basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) varieties: Cultivar and morphotype influence phenolic acid composition and antioxidant properties. NFS J. 2022, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharsono, H.D.A.; Putri, S.A.; Kurnia, D.; Dudi, D.; Satari, M.H. Ocimum species: A review on chemical constituents and antibacterial activity. Molecules 2022, 27, 6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeljković, S.; Komzáková, K.; Šišková, J.; Karalija, E.; Smékalová, K.; Tarkowski, P. Phytochemical variability of selected basil genotypes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 157, 112910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusmitha, K.M.; Aruna, M.; Job, J.T.; Narayanankutty, A.; PB, B.; Rajagopal, R.; Alfarhan, A.; Barcelo, D. Phytochemical analysis, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-genotoxic, and anticancer activities of different Ocimum plant extracts prepared by ultrasound-assisted method. Physio. Molec. Plant Path. 2022, 117, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, B.; Szabó, K.; Bernáth, J. Sources of variability in essential oil composition of Ocimum americanum and Ocimum tenuiflorum. Acta Aliment. 2015, 44, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Fu, Y.; Sussman, M.R.; Wu, H. The effect of developmental and environmental factors on secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Plant Physio. Biochem. 2020, 148, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radácsi, P.; Inotai, K.; Sárosi, S.; Hári, K.; Seidler-Łożykowska, K.; Musie, S.; Zámboriné, É.N. Effect of irrigation on the production and volatile compounds of Sweet basil cultivars (L.). Herba Polon. 2020, 66, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, S.M.; Radácsi, P. Influence of drought stress on growth and essential oil yield of Ocimum species. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.E.; Reiss-Bubenheim, D.; Joly, R.J.; Charles, D.J. Water stress-induced alterations in essential oil content and composition of sweet basil. J. Essen. Oil Res. 1992, 4, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, M.S.; Costa CA, S.; Gomes, F.P.; do Bomfim Costa, L.C.; de Oliveira, R.A.; da Costa Silva, D. Effects of water deficit on morpho-physiology, productivity, and chemical composition of Ocimum africanum Lour (Lamiaceae). Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 1924–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, D.; Fakheri, B. Effects of drought stress on quantitative and qualitative yield, physiological characteristics, and essential oil of Ocimum basilicum L. and Ocimum americanum L. Iran. J. Med. Arom. Plants 2016, 32, 900–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, C.M.; Coelho, K.P.; Silva Araújo Luz, T.R.; Brandão Silveira, D.P.; Coutinho, D.F.; de Moura, E.G. Effect of different water application rates and nitrogen fertilization on growth and essential oil of clove basil (Ocimum gratissimum L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 125, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Huqail, A.; El-Dakak, R.M.; Sanad, M.N.; Badr, R.H.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Soliman, D.; Khan, F. Effects of climate temperature and water stress on plant growth and accumulation of antioxidant compounds in sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) leafy vegetable. Scientifica 2020, 2020, 3808909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, Z.; Farsang, A. Evaluation of metal mobility and bioaccessibility in soils of urban vegetable gardens using sequential extraction. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2013, 224, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacopoeia Hugarica. Pharmacopoeia Hungarica, 7th ed.; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1986; Volume 1, pp. 395–398. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Dool, H.; Kratz, P. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1963, 11, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A., Jr. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phospho-tungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Analy. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osakabe, Y.; Osakabe, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Tran, L.-S.P. Response of plants to water stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selmar, D.; Kleinwächter, M. Influencing the product quality by deliberately applying drought stress during the cultivation of medicinal plants. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 42, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Hui, W.; Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Su, C.; Gong, W. Physiology of plant responses to water stress and related genes: A Review. Forests 2022, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamartzis, I.; Menexes, G.; Georgiou, P.; Dordas, C. Effect of water stress on the physiological characteristics of five basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) cultivars. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.A. Improving drought tolerance in sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) with salicylic acid. Sci. Horti. 2019, 246, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, S.M.; Radácsi, P.; Gosztola, B. Morphological and biochemical responses of selected Ocimum species under drought. Herba Polon. 2022, 68, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, K.A. Influence of water stress on growth, essential oil, and chemical composition of herbs (Ocimum sp.). Int. Agrophysics 2006, 20, 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Mulugeta, S.M.; Sárosi, S.; Radácsi, P. Physio-morphological trait and bioactive constituents of Ocimum species under drought stress. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 205, 117545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, É.Z.; Szabó, K.; Pluhár, Z.; Radácsi, P.; Inotai, K. Changes in biomass and essential oil profile of four Lamiaceae species due to different soil water levels. J. Essen. Oil Res. 2016, 28, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radácsi, P.; Inotai, K.; Sárosi, S.; Czövek, P.; Bernáth, J.; Németh, É. Effect of water supply on the physiological characteristic and production of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). Euro. J. Horti. Sci. 2010, 75, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tátrai, Z.A.; Sanoubar, R.; Pluhár, Z.; Mancarella, S.; Orsini, F.; Gianquinto, G. Morphological and physiological plant responses to drought stress in Thymus citriodorus. Int. J. Agron. 2016, 2016, 4165750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govahi, M.; Ghalavand, A.; Nadjafi, F.; Sorooshzadeh, A. Comparing different soil fertility systems in Sage (Salvia officinalis) under water deficiency. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 74, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, Z.; Hassani, A.; Abdollahi Mandoulakani, B.; Barin, M.; Maleki, R. Effect of drought stress and inoculation treatments on nutrient uptake, essential oil and expression of genes related to monoterpenes in sage (Salvia officinalis). Sci. Horti. 2023, 309, 111610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, H.A.; Valadabadi, S.A.; Daneshian, J.; Khalvati, M.A. Evaluation of essential oil of balm (Melissa officinalis L.) under water deficit stress conditions. J. Med. Plants Res. 2009, 3, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Khorasaninejad, S.; Mousavi, A.; Soltanloo, H.; Hemmati, K.; Khalighi, A. The effect of drought stress on growth parameters, essential oil yield and constituent of Peppermint (Mentha piperita L.). J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 5360–5365. [Google Scholar]

- Hazzoumi, Z.; Moustakime, Y.; Hassan Elharchli, E.; Joutei, K.A. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and water stress on growth, phenolic compounds, glandular hairs, and yield of essential oil in basil (Ocimum gratissimum L.). Chem. Biologic. Techno. Agri. 2015, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaie, H.R.; Nadjafi, F.; Bannayan, M. Effect of irrigation frequency and planting density on herbage biomass and oil production of thyme (Thymus vulgaris) and hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis). Ind. Crops Prod. 2008, 27, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carović-Stanko, K.; Šalinović, A.; Grdiša, M.; Liber, Z.; Kolak, I.; Satovic, Z. Efficiency of morphological trait descriptors in discrimination of Ocimum basilicum L. accessions. Plant Biosys. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Bio. 2011, 145, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, A.P.; Gupta, V. Chemotypic characterization of diversity in essential oil composition of Ocimum species and varieties from India. J. Essen. Oil Res. 2018, 30, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigaye, M.H.; Lulie, B.; Yakob, A.; Nigussei, A.; Mekuria, R.; Kebede, K. Fresh herbage and essential oil yield of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) as affected by mineral fertilizers. Med. Aromat. Plants 2021, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jnanesha, A.C.; Ashish, K.; Vijaya, K.M. Effect of seasonal variation on growth and oil yield in Ocimum africanum Lour. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

| pH H2O | Humus % | KA | NO3-N mg kg−1 | P2O5 mg kg−1 | K2O mg kg−1 | Na mg kg−1 | Mg mg kg−1 | Mn mg kg−1 | Zn mg kg−1 | Cu mg kg−1 | SO4 mg kg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | |||||||||||

| 7.99 | 1.75 | 26 | 11.97 | 473.86 | 377.31 | 45.76 | 146.91 | 22.14 | 2.13 | 1.88 | 24.77 |

| 2022 | |||||||||||

| 7.58 | 1.7 | <25 | 11.36 | 544.43 | 177.36 | 30.11 | 377.93 | 58.48 | 4.90 | 2.46 | 71.58 |

| Species | TRT | Plant Height (cm) | Canopy Diameter (cm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| O. basilicum ‘Ohře’ | I | 43.8 ± 2.5 Aab | 50.3 ± 3.8 Aa | 39.3 ± 2.5 Ab | 50.2 ± 4.4 a |

| NI | 40.3 ± 4.2 Ba | 41.7 ± 4.0 Ba | 34.4 ± 4.4 Ba | 42.0 ± 3.8 a | |

| O. basilicum ‘Genovese’ | I | 47.3 ± 4.9 Aa | 53.3 ± 4.0 a | 38.7 ± 4.7 Ab | 47.7 ± 3.7 ab |

| NI | 40.8 ± 3.6 Ba | 43.7 ± 2.5 a | 34.6 ± 4.5 Ba | 39.3 ± 5.4 a | |

| O. × africanum | I | 44.5 ± 2.2 Aab | 50.2 ± 1.9 a | 45.7 ± 4.2 Aa | 43.3 ± 4.0 b |

| NI | 39.7 ± 5.6 Ba | 41.2 ± 1.8 a | 39.9 ± 5.6 Ba | 34.2 ± 3.7 b | |

| O. americanum | I | 35.7 ± 1.4 Ac | 38.8 ± 2.1 c | 47.1 ± 4.2 Aa | 50.1 ± 2.7 a |

| NI | 30.2 ± 4.2 Bb | 35.4 ± 2.9 b | 36.7 ± 7.2 Ba | 41.4 ± 5.1 a | |

| O. sanctum | I | 42.0 ± 1.9 Ab | 44.5 ± 2.6 b | 30.9 ± 4.8 Ac | 33.3 ± 2.6 c |

| NI | 39.3 ± 4.9 Aa | 35.8 ± 2.9 b | 25.7 ± 5.1 A | 24.2 ± 3.2 c | |

| Species | TRT | Fresh Herb Yield (g plant−1) | Dry Herb Yield (g plant−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| O. basilicum ‘Ohře’ | I | 180.1 ± 28.4 A | 379.7 ± 97.7 Aa | 38.4 ± 6.5 A | 74.4 ± 16.7 Aa |

| NI | 142.4 ± 43.9 B | 221.2 ± 6.0 Ba | 32.1 ± 7.2 B | 39.1 ± 10.5 Ba | |

| O. basilicum ‘Genovese’ | I | 157.8 ± 31.9 Aa | 273.8 ± 53.0 Aab | 34.7 ± 6.4 A | 51.0 ± 10.2 Ab |

| NI | 118.0 ± 26.1 B | 192.2 ± 64.5 Bb | 26.9 ± 5.2 B | 32.9 ± 9.8 Bab | |

| O. × africanum | I | 142.7 ± 57.5 Aa | 269.0 ± 37.4 Ab | 42.2 ± 19.0 A | 67.7 ± 7.5 Aa |

| NI | 108.1 ± 79.2 B | 164.0 ± 47.8 Babc | 32.2 ± 17.4 B | 38.0 ± 10.8 Ba | |

| O. americanum | I | 146.9 ± 30.1 Aa | 214.8 ± 51.7 Ab | 45.9 ± 8.5 A | 43.3 ± 9.9 Abc |

| NI | 97.7 ± 65.8 B | 152.7 ± 33.9 Bbc | 30.7 ± 16.5 B | 35.4 ± 5.8 Bab | |

| O. sanctum | I | 85.0 ± 30.3 Ab | 134.8 ± 11.6 Ac | 32.4 ± 11.3 A | 32.0 ± 2.9 Ac |

| NI | 82.9 ± 28.8 A | 111.2 ± 14.7 Bc | 30.6 ± 9.9 A | 24.3 ± 5.7 Bb | |

| Species | TRT | Essential Oil Content (mL 100 g−1) | Essential Oil Yield (mL plant−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| O. basilicum ‘Ohře’ | I | 1.3 ± 0.2 Ab | 1.2 ± 0.1 Ab | 0.5 ± 0.1 Ab | 0.9 ± 0.0 Ab |

| NI | 1.3 ± 0.3 Ab | 1.2 ± 0.3 Ab | 0.4 ± 0.1 Ab | 0.5 ± 0.1 Bb | |

| O. basilicum ‘Genovese’ | I | 0.8 ± 0.1 Ac | 0.5 ± 0.2 Bc | 0.3 ± 0.0 Ab | 0.3 ± 0.1 Ac |

| NI | 0.9 ± 0.2 Ab | 0.7 ± 0.0 Abc | 0.3 ± 0.1 Ab | 0.2 ± 0.1 Abc | |

| O.× africanum | I | 3.2 ± 0.5 Ba | 2.8 ± 0.0 Ba | 1.9 ± 0.8 Aa | 2.0 ± 0.1 Aa |

| NI | 3.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 2.9 ± 0.2 Aa | 1.6 ± 0.3 Aa | 1.1 ± 0.1 Ba | |

| O. americanum | I | 0.7 ± 0.1 Ac | 0.7 ± 0.1 Ac | 0.3 ± 0.0 Ab | 0.3 ± 0.1 Ac |

| NI | 0.9 ± 0.3 Ab | 0.6 ± 0.1 Ac | 0.3 ± 0.1 Ab | 0.2 ± 0.0 Abc | |

| O. sanctum | I | 1.0 ± 0.1 Abc | 0.6 ± 0.0 Ac | 0.4 ± 0.5 Ab | 0.2 ± 0.0 Ac |

| NI | 1.0 ± 0.0 Ab | 0.7 ± 0.0 Abc | 0.3 ± 0.0 Bb | 0.2 ± 0.0 Ac | |

| Components | RT | LRI | O. basilicum ‘Ohře’ | O. basilicum ‘Genovese’ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | |||||||

| I | NI | I | NI | I | NI | I | NI | |||

| limonene | 8.19 | 1028 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 1,8-cineole | 8.38 | 1034 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 10.9 |

| linalool | 10.76 | 1097 | 43.2 | 40.7 | 57.5 | 40.9 | 40.8 | 41.0 | 47.2 | 50.2 |

| camphor | 12.68 | 1144 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| α-terpineol | 14.55 | 1189 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| nerol | 16.15 | 1227 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||||

| geraniol | 17.29 | 1252 | 16.6 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 12.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| iso-bornyl acetate | 18.52 | 1284 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| eugenol | 21.44 | 1361 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| ß-elemene | 22.55 | 1391 | 4.8 | 5.4 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| methyl eugenol | 23.31 | 1411 | 13.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||||

| (E)-ß-caryophyllene | 23.68 | 1419 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| trans-α-bergamotene | 24.36 | 1437 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 5.4 | 6.8 |

| α-humulene | 25.07 | 1454 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| germacrene D | 26.18 | 1482 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.1 |

| α-bulnesene | 27.23 | 1508 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| cis-γ-cadinene | 27.80 | 1515 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| caryophyllene oxide | 30.20 | 1590 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 1,10-di-epi-cubenole | 31.67 | 1621 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| tau-cadinol | 32.26 | 1644 | 9.7 | 11.2 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 8.8 | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| Others (< 1%) | 6.2 | 7.9 | 4.1 | 5.6 | 9.7 | 10.8 | 19.1 | 8.3 | ||

| Total identified (%) | 97.0 | 97.2 | 98.8 | 97.6 | 95.9 | 96.2 | 97.6 | 99.4 | ||

| Monoterpenes | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.1 | ||

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 65.3 | 59.6 | 75.0 | 60.4 | 53.2 | 58.2 | 61.3 | 66.4 | ||

| Sesquiterpenes | 17.5 | 20.5 | 12.9 | 16.6 | 25.5 | 20.8 | 18.0 | 18.1 | ||

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 12.3 | 13.9 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 13.3 | 11.9 | 10.0 | 10.4 | ||

| Phenylpropanes | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 14.3 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 13.2 | 2.4 | ||

| Components | RT | LRI | O. americanum | O. × africanum Lour. | O. sanctum | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | |||||||||

| I | NI | I | NI | I | NI | I | NI | I | NI | I | NI | |||

| ß-pinene | 6.73 | 981 | 0.1 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 4.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| limonene | 8.19 | 1028 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 16.2 | 16.1 | 16.1 | 14.1 | 0.2 | |||

| 1,8-cineole | 8.38 | 1034 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 35.4 | 32.1 | 38.0 | 36.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| linalool | 10.76 | 1097 | 12.5 | 22.6 | 22.1 | 9.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| camphor | 12.68 | 1144 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 14.3 | 9.9 | 8.0 | 24.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||

| α-terpineol | 14.55 | 1189 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 2.8 | ||||

| nerol | 16.15 | 1227 | 11.6 | 9.3 | 10.1 | 10.6 | ||||||||

| neral | 16.58 | 1238 | 15.2 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 16.4 | ||||||||

| geraniol | 17.20 | 1252 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.3 | ||||||||

| geranial | 17.86 | 1268 | 20.3 | 15.3 | 16.8 | 21.7 | ||||||||

| eugenol | 21.44 | 1361 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 49.3 | 50.3 | 36.4 | 43.1 | ||||||

| ß-elemene | 22.55 | 1391 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 4.4 |

| methyl eugenol | 23.31 | 1411 | 7.2 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 6.0 | ||||||||

| (E)-ß-caryophyllene | 23.68 | 1419 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 26.4 | 30.6 | 38.5 | 31.0 |

| trans-α-bergamotene | 24.36 | 1437 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||||

| α-humulene | 25.07 | 1454 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 5.7 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| germacrene D | 26.18 | 1482 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.1 | |||

| α-bulnesene | 27.23 | 1508 | 0.3 | 1.1 | ||||||||||

| caryophyllene oxide | 30.20 | 1590 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 4.7 | 7.0 | ||||

| tau-cadinol | 32.26 | 1644 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||||||||

| Others (<1%) | 9.7 | 15.4 | 11.5 | 10.8 | 14.4 | 17.9 | 15.6 | 14.7 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 1.0 | ||

| Total identified (%) | 94.4 | 95.8 | 94.2 | 93.1 | 99.0 | 98.2 | 98.5 | 98.9 | 98.9 | 99.0 | 99.1 | 95.1 | ||

| Monoterpenes | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 26.0 | 25.7 | 24.5 | 27.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||

| Oxygenated Monoterpenes | 69.9 | 65.9 | 70.0 | 65.7 | 59.9 | 54.4 | 63.8 | 67.2 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | ||

| Sesquiterpenes | 16.9 | 20.2 | 12.5 | 16.3 | 13.1 | 18.0 | 14.3 | 11.6 | 36.9 | 41.8 | 49.9 | 41.3 | ||

| Oxygenated Sesquiterpenes | 5.7 | 7.7 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 6.2 | 9.0 | |||

| Phenylpropanes | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 56.6 | 54.2 | 42.0 | 44 | ||||||

| Species | TRT | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE g−1 DM) | Antioxidant Capacity (mg AAE g−1 DM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| O. basilicum ‘Ohře’ | I | 217.8 ± 21.8 Abc | 299.5 ± 80.6 Aa | 73.3 ± 10.7 Ab | 79.9 ± 6.3 Aa |

| NI | 200.5 ± 43.4 Bb | 247.8 ± 21.3 Aa | 70.0 ± 13.2 Ab | 76.7 ± 5.0 Aa | |

| O. basilicum ‘Genovese’ | I | 252.6 ± 24.7 Ab | 241.8 ± 54.1 Aab | 83.9 ± 9.70 Aab | 80.2 ± 12.6 Aa |

| NI | 232.4 ± 21.8 Bb | 200.0 ± 20.7 Bbc | 110.9 ± 66.1 Aab | 72.1 ± 6.9 Ba | |

| O. × africanum | I | 208.0 ± 30.9 Ac | 189.1 ± 39.9 Bbc | 66.2 ± 16.7 Ab | 83.3 ± 7.2 Aa |

| NI | 187.9 ± 20.7 Ab | 217.6 ± 36.5 Aab | 79.1 ± 12.9 Aab | 62.6 ± 8.6 Bb | |

| O. americanum | I | 211.5 ± 35.8 Abc | 166.0 ± 5.0 Ac | 70.8 ± 7.9 Ab | 53.2 ± 6.3 Ab |

| NI | 189.6 ± 40.5 Ab | 157.3 ± 8.7 Ad | 72.4 ± 23.7 Aab | 48.4 ± 2.2 Bc | |

| O. sanctum | I | 295.8 ± 45.4 Aa | 143.3 ± 28.6 Bc | 100.7 ± 27.7 Aa | 45.0 ± 9.1 Ab |

| NI | 341.4 ± 84.1 Aa | 170.4 ± 18.8 Acd | 122.9 ± 12.6 Aa | 49.6 ± 8.3 Ac | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mulugeta, S.M.; Hunegnaw, A.T.; Hári, K.; Radácsi, P. Biomass Production and Volatile Oil Accumulation of Ocimum Species Subjected to Drought Stress. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11101266

Mulugeta SM, Hunegnaw AT, Hári K, Radácsi P. Biomass Production and Volatile Oil Accumulation of Ocimum Species Subjected to Drought Stress. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(10):1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11101266

Chicago/Turabian StyleMulugeta, Sintayehu Musie, Amare Tesfaw Hunegnaw, Katalin Hári, and Péter Radácsi. 2025. "Biomass Production and Volatile Oil Accumulation of Ocimum Species Subjected to Drought Stress" Horticulturae 11, no. 10: 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11101266

APA StyleMulugeta, S. M., Hunegnaw, A. T., Hári, K., & Radácsi, P. (2025). Biomass Production and Volatile Oil Accumulation of Ocimum Species Subjected to Drought Stress. Horticulturae, 11(10), 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11101266