Abstract

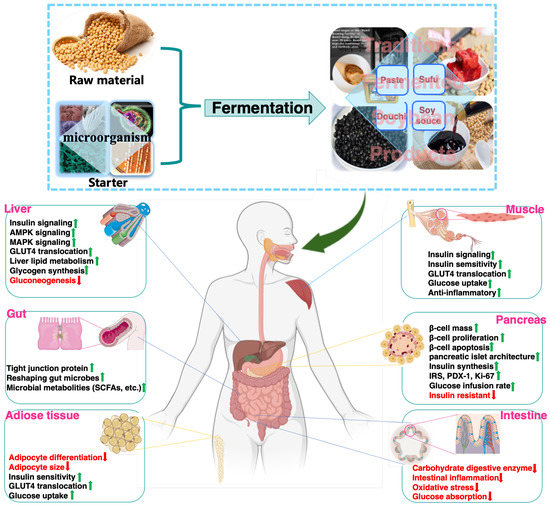

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disease, characterized by persistent hyperglycemia, the prevalence of which is on the rise worldwide. Fermented soybean products (FSP) are rich in diverse functional ingredients which have been shown to exhibit therapeutic properties in alleviating hyperglycemia. This review summarizes the hypoglycemic actions of FSP from the perspective of different target-related molecular signaling mechanisms in vitro, in vivo and clinical trials. FSP can ameliorate glucose metabolism disorder by functioning as carbohydrate digestive enzyme inhibitors, facilitating glucose transporter 4 translocation, accelerating muscular glucose utilization, inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis, ameliorating pancreatic dysfunction, relieving adipose tissue inflammation, and improving gut microbiota disorder. Sufficiently recognizing and exploiting the hypoglycemic activity of traditional fermented soybean foods could provide a new strategy in the development of the food fermentation industry.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a non-communicable, chronic metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia, defects in insulin secretion, and insulin action, which has become a major public health issue worldwide with significant economic and social implications [1]. Of the three major types of diabetes, type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is far more common (accounting for approximately 90% of DM cases) than either type 1 diabetes mellitus or gestational diabetes [2]. The global burden of T2DM has risen substantially in the last 20 years, affecting more than 463 million individuals globally [3]. T2DM is primarily caused by two interrelated factors: (1) cells in muscle, fat, and the liver become resistant to insulin; (2) defective insulin secretion by pancreatic beta-cells [4]. Drug therapies are available but are associated with various side effects such as several hypoglycemia, muscle pain, disturbed mitochondrial function, and bladder cancer [5]. Thus, developing food-derived alternatives to oral hypoglycemic drugs without side effects or toxicity is of practical importance [6]. Increasing evidence suggests that food-derived bioactive compounds have vast potential in the mitigation of T2DM [7].

Soybeans have long been an indispensable part of a healthy diet in many Asian countries mainly due to the high contents of proteins (38–42%), oil (20–30%), and some phytochemicals. Phytoestrogens and proteins in soybeans seem to have beneficial actions both on glucose metabolisms, and additional micronutrients such as saponins, phytosterols, trypsin inhibitors, as well as the amino acid and protein composition, may have additive or synergistic effects [8]. The high biological value of soy protein makes it nutritionally commensurable to animal proteins like casein, egg, and beef [9]. Many epidemiological studies have demonstrated the benefits of soybean products in lowering the risks of T2DM, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers such as breast, prostate, and colon cancers [10]. Soybean is consumed in both unfermented (roasted and fried soybeans, soybean powder, soybean butter, soy milk, tofu, soybean oil, etc.) and fermented (soy sauce, tempeh, natto, douchi, doenjang, etc.) forms [11,12]. However, it should be noted that the presence of anti-nutrients (e.g., agglutinins, phytochemicals, saponin, and protease inhibitors) in soybeans can interfere with the digestion, absorption, and metabolism of nutrients, thereby limiting the nutritional values of soybean foods [13]. Fermentation, however, can improve the physicochemical properties, sensory quality, and nutritive value of soy foods [14,15].

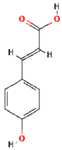

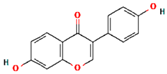

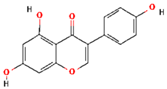

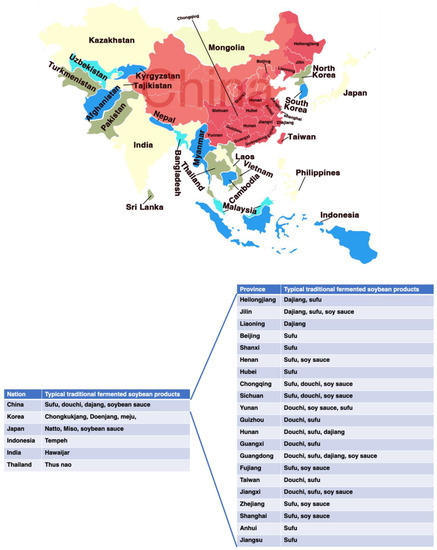

Fermented soybean foods are one of the most popular consumed foods in Asian countries, such as douchi, sufu, soy sauce, doubanjiang in China, meju, cheonggukjang, doenjang, kanjang in Korea, natto, miso, tofuyo, shoyu in Japan, tempeh in Indonesia, thua-nao in Thailand, kinema, hawaijar, tungrymbai in India (Figure 1) [12,16]. Soybean fermentation also results in the release of new bioactive components (e.g., peptides, isoflavonoids) by the action of proteolytic enzymes produced by the microorganisms involved during fermentation [17]. After fermentation, isoflavonoid glycones are changed into isoflavonoid aglycones, which seem to have greater activity than do isoflavonoid glycones [8]. Many of these components are believed the major contributors to the health benefits of fermented soybean products (FSP) [18]. Indeed, consumption of FSP, but not unfermented soybeans, has been reported to have therapeutic properties for T2DM [8,19,20,21]. This review aims to summarize the promising antidiabetic properties of FSP and to dissect how the FSP acts over a variety of molecular targets such as carbohydrate digestion and intracellular signaling pathways in multiple organs to maintain glucose homeostasis.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution and variety of traditional fermented soybean products in Asia countries.

2. Traditional Fermented Soybean Foods: Processing and Products

Traditional fermented soybean products have a long history and are very popular in many countries. According to records, China was the first country to produce FSP, with douchi, dajang, sufu, and soy sauce as the representative products. These FSPs were introduced to Japan, Korea, Philippines, Indonesia, and other southeast Asian countries and regions in the early stages, and have further evolved with local characteristics, such as the famous Japanese natto and miso, Korea doenjang and cheonggukjang, and Indonesian tempeh [22]. China, Japan, and Korea are the leading producers of FSP worldwide. Although FSP originated in Asia, these products are consumed, popularized, and produced worldwide as Asian food has prospered globally. Moreover, FSP are believed to have health-promoting effects such as anti-diabetes, anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, and anti-cancerous effects. Because of their healthy functions, these fermented foods have recently gained popularity [23].

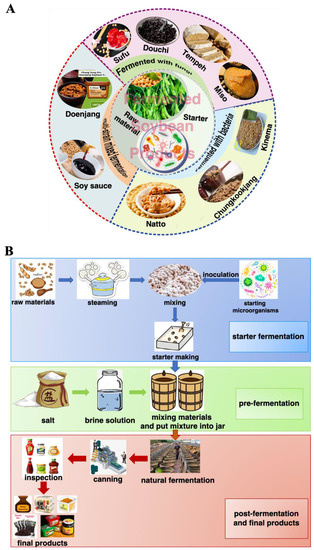

Fermentation of soybean gives rise to different products based on many criteria, but mainly due to the microorganism used in the process as they affect the aroma, texture, therapeutical, and nutraceutical values. Bacillus spp., lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and fungi (i.e., Aspergillus oryzae, Mucor spp. Rhizopus spp., and Fusarium spp.) are reported to be the key players in FSP [12,24]. Some of the FSP are fermented only with bacteria (natto, chungkookjang, kinema); some are fermented solely with fungi (douchi, tempeh, sufu, miso, tofu) and in some cases, both microorganisms are used (doenjang) (Figure 2A) [12]. Records of production methods were found in Qimin Yaoshu (Essential Techniques for the Peasantry), a magnum opus of historically significant Chinese manuscript dating back to 533–544 AD, and others in the Korean manuscript Samkuksaki, dating from the 1392s, pointing to the consumption of fermented soybeans since the 12th century [24]. FSP are usually made from soybeans and wheat. Generally, an open process of single-strain or multi-strain mixed fermentation is adopted, which mainly includes two steps of koji making and post-fermentation [22,25]. Figure 2B depicted the common production process of FSP. Firstly, the raw materials are pretreated (sorting and soaking). Then, they are heated at high temperatures, where starch is thoroughly gelatinized, and protein is moderately denatured. After that, starter cultures (for example, Aspergillus oryzae, Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, Lactobacillus plantarum, Bacillus subtilis, Rhizopus spp., and Mucor spp., etc.) are inoculated naturally or artificially for ventilated koji making and takes 3–15 days. In the post-fermentation, where the addition of salt or brine and other spices is carried out and then fermented naturally [22,26]. Under the action of microorganisms, macromolecular substances in raw materials are hydrolyzed into small molecules of peptides, amino acids, sugars, and a variety of volatile flavor substances and functional nutrients (flavonoids, phenolic acids, and saponins) are produced at the same time [12,15,27,28]. Understanding the complex fermentation process of FSP, revealing the diversity of microorganisms, and analyzing the relationship between the core functional microorganisms and the related metabolites by combining molecular biology techniques and bioinformatics analysis tools in the fermentation process are conducive to regulate directionally the traditional fermentation process to enrich the formation of FSP-derived bioactive compounds.

Figure 2.

Fermented soybean products (A) and their production process (B).

3. T2DM and Its Pathogenesis

A widely acknowledged concept for T2DM is a heterogeneous and polygenic disorder resulting from genetic susceptibility, characterized by damaged insulin signaling, or insulin resistance, and a relative insulin deficiency of non-autoimmune etiology, and environmental elements involving overeating, obesity, stress, lack of exercise, and aging [29]. T2DM places considerable socioeconomic pressures on the individual and overwhelming costs to global health economies, estimated at US $825 billion [30].

Epidemiology of T2DM is affected by genetic and environmental factors. Genetic factors exert their effect following exposure to an obesogenic environment characterized by sedentary behavior and excessive sugar and fat consumption [31]. Under normal physiological circumstances, insulin controls blood glucose homeostasis within a narrow range via stimulation of glucose uptake into peripheral tissues mainly skeletal muscle as well as fat tissue through inhibiting the release of stored lipids from adipose tissue by liver. In T2DM, this mechanism is halted when insulin secretion is impaired via a dysfunction of the pancreatic β-cell, and compromised insulin action because of insulin resistance, therefore resulting in multiple metabolic abnormalities [32]. Obesity and physical inactivity lead to insulin resistance, which together with a genetic predisposition, places stress on β-cells, leading to a failure of β-cell function and a progressive decline in insulin secretion [2]. It is well known that insulin resistance, a malfunctioning status when the insulin cannot play its biological effects but should be functional under the normal case, is the major contributor to the pathogenesis of T2DM. Muscle and liver, the two tissues responsible for the majority of glucose disposal following carbohydrate ingestion, are common tissues in which insulin resistance occurs; it also occurs in adipose, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, vasculature, and brain tissues, and pancreatic β-cells [2,29]. The intransigency of insulin action leads to impaired glycogen synthesis and glucose uptake in peripheral tissues [33].

Therefore, the most effective therapeutic strategies for patients with T2DM should target both aspects of the complex interaction between the target organs or tissues and the signaling pathways, thereby improving the glucose metabolism disorder.

4. Major Targets and Related Signaling Pathways of Glucose Metabolism and Homeostasis

Disrupted tissue glucose metabolism and systemic glucose homeostasis are important clinical features of T2DM [34]. Effective T2DM management requires a comprehensive approach to reduce blood glucose, normalize β-cell functions, and improve insulin sensitivity through weight management, diet, or medication [35]. This is not a simple task, given the complexity of the physiology of glucose homeostasis and the multifactorial nature of the metabolic syndrome. Organ systems involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism include the following: (1) The gastrointestinal tract, which processes dietary carbohydrates via α-amylase and α-glucosidase into glucose, and then delivers glucose to the systemic circulation and secretes incretin hormones that help regulate glucose disposal. (2) The endocrine pancreatic system, which regulates the expression of key glucoregulatory hormones such as insulin, glucagon, and amylin. (3) The hepatic system, where glucose production is initiated in the fasting state and glucose uptake is facilitated in the fed state. (4) Musculoskeletal and adipose tissue, where glucose is metabolized during energy expenditure or stored for future need [36]. The importance of the role of the gut in regulating glucose homeostasis has now also been highlighted, possibly by via alteration of the intestinal microbiota [37].

Within this complex network, nutrition plays a pivotal role on maintaining glucose homeostasis. Increasing evidence suggests that FSP can alleviate glucose metabolism disorders via the synergistic effect among the above-mentioned glucoregulatory organs [8,38,39,40,41]. The purpose of this review is to briefly summarize available data linking FSP to glucose metabolism disorders and to provide insights into their potential mechanisms of action via different glucoregulatory organs, which are highlighted in the sections below.

4.1. Effect of FSP on Carbohydrate Digestive Enzymes

One effective strategy to control postprandial hyperglycemia is to slow down the digestion of glucose through the inhibition of principal digestive enzymes such as α-amylase and α-glucosidase, which hydrolyze carbohydrates into absorbable monosaccharides [42]. Dietary carbohydrates are digested by α-amylase to smaller oligosaccharides, which are then further digested by α-glucosidase to glucose to be absorbed across the intestinal barrier aided by glucose transporters [43]. Inhibitors of α-amylase and α-glucosidase, which slow the final stages of carbohydrate digestion and consequently prevent the entry of glucose into the circulation, are considered a viable prophylactic treatment of hyperglycemia [44]. However, most classic drugs of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors (e.g., acarbose, voglibose and miglitol) have certain adverse effects such as flatulence, diarrhea, and abdominal pain [45]. Natural glucosidase inhibitors are identified from FSP (such as douchi in China, doenjang in Korea, miso in Japan, and tempeh in Indonesia, etc.) (Table 1). A previous study found that diabetic rats supplemented with 10% fermented soybean for 14 days could reduce the α-amylase and intestinal α-glucosidase activities, which was due to the presence of phenolic phytochemicals [46].

Table 1.

FSP inhibit carbohydrates digestive enzymes.

Douchi is a popular fermented soybean product with a history of use for over 2000 years. Many historical medical books have described douchi being able to prevent T2DM [22]. Douchi has attracted much attention as a functional food ingredient in recent years. Production of douchi is generally achieved by two processes: pre-fermentation (also called koji-making) and post-fermentation. Pre-fermentation could endow douchi with nutritional properties via the actions of different microbes. Post-fermentation is the key production process for developing the special nutrients and flavor of douchi and is carried out by adding salt and other spices to the koji, mixing, and leaving the mixture in a container [55]. Depending on the microbes that are present during the koji-making progress, douchi is usually classified into one of four categories: Aspergillus-type (i.e., Liuyang douchi), Mucor-type (i.e., Yongchuan douchi), Rhizopus-type (i.e., Indian tempeh), and Bacterial-type (i.e., Japanese natto).

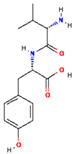

Chen et al. [47] analyzed the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of 31 douchi samples collected from various parts of China. Among them, samples from Hunan, Sichuan and Jiangxi province, respectively, showed a significantly higher anti-α-glucosidase activities than other samples (p < 0.05). The anti-α-glucosidase activity in douchi was associated with numerous factors, such as microorganisms, raw materials, additives, and fermentation parameters [16]. The anti-α-glucosidase activity of douchi qu fermented with A. oryzae was higher than those of A. elegans and R. arrhizus, which indicated that A. oryzae could utilize soybean to generate certain α-glucosidase inhibitor more effectively than A. elegans and R. arrhizus during the douchi fermentation [47], suggesting that the microbial species had different inhibitory activities on carbohydrate digestive enzymes during douchi fermentation. Furthermore, Fujita et al. [48] identified components in douchi with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity and found that douchi extract exhibited anti-glycemic activity via α-glucosidase inhibition action (IC50 = 0.34 g/L) in rats and humans. In their clinical trial of evaluating α-glucosidase inhibitory, the intake of douchi extract (0.3 g/meal, 3 times a day) for 6 months resulted in decreased blood glucose levels in 14 T2DM subjects (77.8%). Coincidentally, our group also found that the Mucor-type douchi extract could block the uptake of postprandial glucose by preventing the digestion of carbohydrates via α-glucosidase inhibition action (IC50 = 0.35 mg mL−1) in L6 cells [41]. Moreover, we found that douchi extract-derived peptides Val-Tyr (VY) and Ser-Phe-Leu-Leu-Arg (SFLLR) with hypoglycemic activity in L6 cells [41].

Doenjang is a traditional food product through the fermentation of soybeans by naturally occurring bacteria (Bacillus species, in the early stage) and fungi (mainly Aspergillus oryzae and Aspergillus niger, in the later fermentation stage) and has been consumed for centuries as a rich protein source and flavoring ingredient in Korea [56]. Scientific reports reported that doenjang is a potent source of α-glucosidase inhibitor and could suppress postprandial hyperglycemia, making doenjang useful for treating diabetic and/or obese patients [49]. A study from Shukla et al. [49] found that doenjang samples demonstrated considerable α-glucosidase inhibitory effect in vitro and thus may hold the potential to reduce blood glucose responses to carbohydrate challenges. The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the starter culture of doenjang samples increases in a concentration-dependent manner and is also affected by the types and ratios of strains. Chun et al. [50] reported that the doenjang sample fermented with A. oryzae, M. racemosus 42, and B. subtilis TKSP 24 in a ratio of 1:1.5:0.5 showed the highest α-glucosidase inhibitory activity (67.14% ± 1.14%), indicating the potential applications of doenjang for treatment of T2DM. These findings confirm that the starter culture in doenjang has a significant effect on the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. As reported previously, methanol extract of traditional doenjang from Jeju (Korea) displayed α-glucosidase inhibitory activities in the range of 33.5–44.3% [57]. Further, Yang et al. used metabolomic analysis to find that doenjang component responsible for inhibiting the α-glucosidase activities is betaine (a zwitterionic quaternary ammonium compound that is also known as trimethylglycine, glycine betaine, lycine, and oxyneurine), which suppressed carbohydrase activity by 72% by 10 mg/mL [51]. Interestingly, Shukla et al. [49] found that the content of polyphenols in doenjang also has a positive effect on the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity.

Miso is one of the fundamental seasonings used in Japanese cuisine made by the fermentation of soybean paste, which is said to have originated in ancient China or perhaps in Japan thousands of years ago. The use of miso spread among Japanese people during the Edo Period (1603–1868), and miso constitutes one of the hallmarks of the country’s salted and fermented soybean seasoning along with soy sauce [58]. Miso is primarily made from soybeans, which are combined, fermented, and matured with soybeans and/or grains cultured with koji mold and salt [59]. This fermented product not only has a distinct mouthfeel and flavor but it is also demonstrated several health benefits, including anti-diabetes properties, improved digestion, and anti-hypertension [15]. Momose et al. [52] found that dietary intake of various kinds of miso could control postprandial blood sugar in a human intervention trial. Meanwhile, they found that all kinds of miso inhibited the activities of various digestive enzymes (α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and trypsin) to varied extents, which indicated miso may be a food that can be used to prevent diabetes in the future [52]. In another study, Jiang et al. [53] analyzed the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of rice miso at different fermentation periods (3, 6, 24, 36 months). The results showed that α-glucosidase inhibitory activity in rice miso was increased at prolonged periods of fermentation. Furthermore, they concluded that melanoidins were the main α-glucosidase inhibitory activity component in rice miso [53].

Tempeh, a fermented soybean by Rhizopus spp. mold originally from Indonesia, is an excellent protein source with high nutritional quality [60]. Tempeh has higher nutritional values compared to soybeans because the fermentation process degrades carbohydrates, fat, and protein and improved their bioavailability. Astawan et al. reported that tempeh had a high α-amylase (IC50 = 74.8 mg/mL) and α-glucosidase inhibition values (IC50 = 85.3 mg/mL) [54]. Tempeh contains a higher content of isoflavones (daidzein, genistein, and total isoflavone) due to the action of microorganisms during the fermentation [54], and further study is needed to investigate the relationship between isoflavones and the activity of carbohydrate-cleaving enzymes.

4.2. Effect of FSP on Glucose Transporter-4 (GLUT4) Translocation and Glucose Utilization

Glucose homeostasis is maintained by a complicated and intertwined hormonal system that manipulates short-and long-term blood glucose regulation [61]. Insulin is crucial for maintaining plasma glucose homeostasis, via promoting glucose uptake from the circulation into the insulin-sensitive storage sites of muscle and adipose tissues by GLUT4 [62]. GLUT4 activation, i.e., translocation from intracellular storage sites to the cell membrane surface, is driven mainly through the activation of the insulin signaling cascade in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, which facilitates glucose uptake [63]. Glucose can also be up-taken via GLUT2 in an insulin-independent manner in hepatocytes [64]. Studies have shown that in patients with T2DM, insulin resistance triggers lower expression and translocation of GLUT4. Therefore, increasing the levels and translocation of GLUT4 is a crucial factor in regulating glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity to prevent the development of hyperglycemia [65].

Growing evidence has revealed that FSP can improve glucose utilization via GLUT4 activation (Table 2) [8,15,34,66]. Das et al. [67] examined the antidiabetic activity of popular fermented soybean foods in Northeast India. Results showed that among different traditional fermented soybean foods (Akhuni, Bekang, Kinema, Hawaijar, Peruyaan, and Tungrymbai) of Manipur, Hawaijar supplementation led to significant translocation of GLUT4 from the perinuclear region to the membrane in L6 myotubes in a dose-dependent manner from 1 to 5 mg/mL, resulting in increased glucose uptake. In another study, Huang et al. found that black soybean koji (a fermented black soybean product) treatment also increased the GLUT4 expression in a dose-dependent manner from 20 to 200 μg/mL in the insulin-resistant 3T3-L1 preadipocytes, thus promoting the glucose uptake [68]. Studies have found that Hawaijar extract could decrease fasting blood glucose, upregulate GLUT4 expression and glucose tolerance in the skeletal muscle tissues through phosphoinositide-3-kinase/protein kinase B/AMP-activated protein kinase (PI3K/AKT/AMPK) activation with dose-dependent manner (50, 100, or 200 mg/kg BW/day for 16 weeks) after administration in HFD-fed rats [67]. A similar study also found that an extract from Bacillus subtilis MORI (BTD-1) fermented soybean could suppress adipocyte differentiation by inhibiting protein expression of the adipogenic gene, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α (C/EBPα), but at the same time, it may also act as an agonistic ligand of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ, thereby increasing the GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane along with significantly increased glucose uptake into the adipocytes through improving insulin sensitivity [69]. However, there is a need to characterize the compounds that are responsible for promoting GLUT4 translocation. Huang et al. analyzed the content of isoflavone in the black bean koji but not for other flavonoids, such as anthocyanin, which are responsible for increasing GLUT4 expression [70]. The results revealed that fermentation caused the increase in the amount of isoflavone aglycones (daidzein and genistein) and a decrease in isoflavone glucosides (malonylgenistin and malonyldaidzin), indicating isoflavone-rich black bean koji may also have the similar functions against hyperglycemia [68]. Similarly, Kwon et al. [71] also found an increase in isoflavonoid aglycones (daidzein) and smaller peptides in chungkookjang extracts (a traditional Korean fermented soybean products with Bacillus subtilis) during fermentation, thereby enhancing glucose uptake resulted from stimulating translocation of the GLUT4 into the plasma membrane via activating insulin signaling and stimulates PPAR-γ activity in adipocytes. It’s interesting to note that douchi-derived peptides (VY and SFLLR) could also increase GLUT4 translocation via the activation of AMPK and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in L6 cells, leading to increased glucose uptake [41]. In another study, Das et al. found that a ~24 kDa single protein isolated (ISP) from HPI (Hawaijar protein isolate) could improve glucose utilization and insulin resistance, which was associated with GLUT4 translocation properties in the skeletal muscle tissues of high-fructose high-fat diet-fed rats [72]. ISP also showed insulin-sensitizing effects by facilitating insulin-dependent glucose uptake via GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane by inducing the PI3K/AKT cascade in C2C12 myoblast cells [72]. These results indicate that different compounds, responsible for GLUT4 translocation, are produced due to different microorganisms, raw materials, additives, and fermentation parameters in different fermented soybean products.

Table 2.

Studies associated with hypoglycemia of FSP to prove GLUT4 expression and GLUT4 translocation.

4.3. Effect of FSP on Muscle Glucose Homeostasis

Skeletal muscles represent the major site in maintaining normal glucose homeostasis and in regulating whole-body glucose metabolism [73]. The beneficial effect of FSP supplementation has been clearly implicated in the amelioration of impaired muscle glucose metabolism. Some studies demonstrated that FSP, such as douchi [41], Hawaijar [67,72], chungkukjang (a traditional Korean soybean paste fermented for only a few days) [74], and fermented soybean paste [75], could mimic the effect of insulin on glucose transport and glycogen synthesis through insulin-dependent and -independent signaling pathways in muscle tissues in vitro or in vivo. Therefore, FSP may have a direct role in affecting insulin sensitivity, glucose uptake, and utilization, and glycogen synthesis in muscle (Table 3).

Table 3.

The mechanisms of modulating the effect of FSP on glucose homeostasis in muscle tissues.

Compared to unfermented soybeans, chungkukjang supplementation increased whole-body glucose disposal rates and glucose uptake into skeletal muscles of high-fat diet-induced pancreatectomized diabetic rats via enhancing insulin signaling [74]. This indicated that fermented soybeans mainly with Bacillus subtilis improved glucose utilization, in comparison to unfermented soybeans in diabetic rats. In a high-fructose high-fat diet-fed rat model of type 2 diabetes, both Hawaijar [72] and fermented soybean paste [75] stimulated glucose uptake into skeletal muscle via enhanced PI3K/AKT and AMPK activation. In another study, Malardé et al. found that three weeks of consumption of fermented soy permeate stimulated the conversion of intramuscular glucose into glycogen, leading to an accumulation of glucose in the muscle of STZ-diabetic mice [76]. In KK-Ay/TaJc1 mice (genetically obese type 2 diabetes), Morinda citrifolia (aka Noni) fermented by cheonggukjang (fast-fermented soybean paste, FMC) supplementation reduced blood glucose and improved insulin resistance. Furthermore, FMC extract supplementation stimulated glucose uptake via the stimulation of PPAR-γ and AMPK in C2C12 myotubes [77]. Further, studies found that the intake of FSP offers protection against glucose metabolism disorders in muscle, which is an effect of the fermentation resulting in elevated contents of active ingredients (i.e., isoflavones aglycones and peptides) and higher diversity and richness of microbes [41,71,74,75].

4.4. Effect of FSP on Hepatic Glucose Homeostasis

Liver is the major organ of glucose metabolism including the synthesis, storage, and redistribution of carbohydrates and is an important target organ for the action of insulin [78]. However, T2DM impairs liver function resulting in the loss of the direct effect of insulin to suppress hepatic glucose production and glycogenolysis in the liver, thus causing an increase in hepatic glucose production [79]. A plethora of literature investigated the prophylactic role of FSP against diabetes-induced impairment of hepatic glucose metabolism via various molecular mechanisms (Table 4) [8,38,40,50,74,80,81,82,83].

Table 4.

The mechanisms of modulating the effect of FSP on glucose homeostasis in liver tissue.

Several animal studies and a few human studies have evaluated the effects of fermented soybeans on glucose metabolism as reviewed previously [8,38,74,83]. Previous studies found that both meju (unsalted soybean fermented with Bacillus subtilis and Aspergilus oryzae) and chungkukjang supplementation not only improved glucose uptake but also inhibited hepatic glucose output via potentiating insulinotropic actions and alleviating hepatic insulin resistance in 90% pancreatectomized (Px) diabetic rats, a moderate and non-obese type 2 diabetic animal model [74,80]. Similarly, a study performed by Kwon et al. confirmed that kochujang (a Korean fermented red pepper plus meju and soybean paste) supplementation lowered hepatic glucose output and triglyceride levels and increased glycogen storage via the activation of AMPK signaling, leading to glucose homeostasis in 90% pancreatectomized diabetic rats [39]. In another study, Kim et al. [81] found that chungkukjang supplementation increased hepatic glycogen content and improved insulin tolerance via reducing glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) activity in C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. Therefore, chungkukjang improved diabetic symptoms in type 2 diabetic rats more than non-fermented soybeans, and this was related to increased isoflavonoid aglycones such as daidzein and genistein and small peptides [82]. It’s worth noting that hepatic function also has a significant effect on hepatic glucose homeostasis. Studies showed that supplementation with 4% of douchi extract (DE) for 60 days and 0.3 g of DE for 3 months in KKAy diabetic animals and mild type 2 diabetic patients, respectively, decreased fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels via reduced indexes of hepatic functional disorders such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) [40,83].

On the other hand, chronic hyperglycemia is strongly associated with hepatocellular oxidative stress leading to hepatic damage [34]. A recent study has shown that dietary supplementation of fermented paste made from soybean, brown rice, or brown rice in combination with rice bran or red ginseng marc improved hyperglycemia and oxidative stress via regulation of the oxidative stress and hepatic antioxidant enzymes activities in mice fed with high-fat diet [50]. In 2022, Hariyanto et al. found that supplementation of soybean residue fermented with Rhizopus oligosporus and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum in STZ-induced hyperglycemic mice, can improve the glucose homeostasis via increasing antioxidative capacity and reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) level, which was mainly attributed to the augmented contents of isoflavone aglycones and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [84].

4.5. Effect of FSP on Adipose Tissue Glucose Homeostasis

Adipose tissue is an organ with active endocrine function involved in the regulation of energy balance and glucose homeostasis via multiple metabolic signaling pathways targeting the brain, liver, skeletal muscle, pancreas, and other organs [85]. Chronic excess calorie intake and the inability to generate new fat cells (adipocytes) may cause ectopic fat deposition, resulting in peripheral insulin resistance, particularly in skeletal muscle [86]. It is reported that insulin action as well as the expression of various adipokines in adipose tissue are disrupted by diabetes-induced metabolic complications [34]. However, FSP supplementation has been shown to influence the function of adipose tissue in subjects with diabetes [8,87,88]. And FSP can elicit insulin-sensitizing action via inducing adipocyte differentiation (Table 5) [69,71]. Two key transcription factors in this process are the PPAR-γ and C/EBPα. PPAR-γ activates genes involved in adipocyte differentiation and fatty acid sequestration [89]. A previous study found that after fermentation, chungkookjang enhances glucose utilization via activating the IRS1-PI3K-Akt-GLUT4 signaling pathway and stimulates PPAR-γ activity in adipocytes [71].

Table 5.

The mechanisms of modulating the effect of FSP on glucose homeostasis in adipose tissue.

Besides in vitro evidence, studies in vivo also supported the stimulatory effect of FSP on adipocyte differentiation. For instance, high-fat diet-fed obese mice supplemented with fermented soybean pastes for a period of 14 weeks showed significant increase in adiponectin levels in mesenteric adipose tissue concomitantly with the improvement of hyperglycemic parameters including plasma insulin level [75]. Despite the well-documented beneficial effects of enhanced PPAR-γ expression and adipocyte differentiation on insulin sensitivity, inhibition of adipocyte differentiation has also shown beneficial outcomes in some studies [91]. When 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with kochujang extract, the lipid accumulation was decreased by inhibiting adipogenesis through down-regulation of SREBP-1c and PPAR-γ [90]. On the other hand, doenjang has also been reported to elicit similar action in mice fed a high-fat diet [92]. In 2015, Hwang et al. demonstrated that the administration of an extract from fermented soybean (by Bacillus subtilis MORI) significantly suppressed adipocyte differentiation by inhibiting the C/EBPα protein expression in 3T3-L1 murine preadipocytes. These events were concomitant with the upregulation of GLUT4 translocation followed by increased glucose uptake [69]. However, it should be noted that inhibition of adipocyte differentiation per se without affecting whole-body energy balance is not beneficial for adipose tissue health and function. Inhibition of adipocyte differentiation could possibly result in the generation of hypertrophied adipocytes with less buffering capacity for circulating fats, and hence redistribution of body fat into non-adipose peripheral tissues in physiological conditions [93]. This would eventually lead to the development of insulin resistance in these tissues.

4.6. Effect of FSP on Pancreatic Morphology and Function

Insulin and glucagon, synthesized by β- and α-cells, respectively, are key regulators of glucose homeostasis. The pathophysiology of T2DM is associated with pancreatic tissue damage and compromised islets function [94]. Therefore, repairing of pancreatic tissue/cells is considered as a useful strategy to combat insulin deficiency and impaired glucose homeostasis. Multiple studies postulated that FSP can potentially ameliorate the pancreatic damage and promote insulin secretion to minimize the hyperglycemic condition (Table 6).

Table 6.

The mechanisms of modulating the effect of FSP on glucose homeostasis in pancreatic tissue.

For instance, administration of chungkukjang in C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice was shown to improve β-cell exhaustion and insulin deficiency, thus leading to improve insulin resistance in peripheral tissue [81]. Kwon et al. also supported that supplementation with chungkukjang in 90% pancreatectomized diabetic rats exhibited the ameliorative potential of insulin secretion by increasing the number of β-cells. This effect did not observe in unfermented soybeans [95]. Similarity, after 8-week feeding of a soybean extract from fermented soybean by Bacillus subtilis MORI in db/db mice, the pancreatic islet architecture was preserved and the immunofluorescent intensities of insulin [96]. In these studies, it was showed that the strain Bacillus subtilis has an important role in the antidiabetic effects of the product due to its ability to produce hydrolyzing enzymes [88]. Consistent with these findings, the administration of tempeh could also prevent pancreatic β-cell damage in STZ-induced diabetic rat model. However, it was proven by insulitis degree on Langerhans islet of diabetic rats fed by tempeh was lower compared to Langerhans islet of diabetic rats fed by soybeans [97]. This indicates that soybean through its fermentation process was more protective on pancreatic diabetes than un-fermented soybean.

4.7. Effect of FSP on Glucose Homeostasis through Gut Microbiota

Hippocrates, credited with the famous lines “All disease begins in the gut” and “Let food be thy medicine,” appeared to have a very progressive view of how the gastrointestinal (GI) tract could play a mediating role between food and human health [98]. Dietary habits have been associated with the rising prevalence of health conditions resultant from gut microbiota dysbiosis [99]. Western dietary habits are characterized by high in saturated fats, refined carbohydrates and salt. Evidence suggests that this diet shift the composition of gut microbiota from fewer beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus, Bacteroidetes) to more of the harmful bacteria (e.g., Firmicutes, Clostridium) [100,101]. This dysbiosis is a key factor in the onset and development of glucose metabolism disorder and other metabolic diseases. Overall, the evidence suggests that microbial profiles could be regulated by dietary changes.

Fermented soybean foods are reported to improve gut microbiome via their own microbiome or through their constituents in the matrix [102]. Soka et al. observed that tempeh treatment significantly increased the abundance of Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium leptum, and decreased the abundance of Firmicutes in healthy SD rats [103]. Jeong et al. observed that the relative abundance of Bacillales, Lactobacillales, and Verrucomicrobiales (Akkermensia muciniphila) was increased, while the relative abundance of Enterobacteriales was decreased in type 2 diabetic rats supplement with chungkookjang [104]. They also found that chungkookjang treatment improved mucin contents by increasing beneficial bacteria, including Akkermensia, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus, and decreasing harmful bacteria, Enterobacteriales, and promoting intestinal villi and goblet cells in partially pancreatectomized non-obese diabetic rats [21]. Their results suggested that chungkookjang could modulate glucose homeostasis by stimulating mucin secretion to promote Akkermensia and Lactobacillus growth and inhibit Enterobacteriales growth to regulate the gut microbial composition. Huang et al. found that tempeh intake significantly increased the relative abundance of Lactobacillus but decreased Bacteroides at the genus level in STZ-induced T2DM rats. Further study demonstrated that the therapeutic effect of tempeh on modulating glucose homeostasis was closely associated with the modulation of gut microbiota and increased intestinal short-chain fatty acids release [105]. While animal study supports a key role of FSP consumption on gut microbiota (Table 7), human studies are warranted to determine whether FSP can modify composition and metabolic activity of the human intestinal microbiota.

Table 7.

The mechanisms of modulating effect of FSP on glucose homeostasis through gut microbiota.

5. Conclusions and Future Remarks

In addition to improving sensory and nutritional attributes, mounting evidence supports that FSP are beneficial for decreasing the risk of onset and progression of glucose metabolism disorder, insulin resistance and T2DM. This review summarizes research progress on the glucoregulatory properties of FSP and their underlying mechanisms of action. In addition, the responsible components of FSP and their acting on cellular targets, signaling pathways, and tissues for regulating glucose homeostasis are discussed. Thus, effect of FSP (raw materials, fermentation processing) on glucoregulatory activity, possible target tissues and related signaling pathways were presented (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Glucoregulatory mechanisms of FSP on major organs.

A wide range of food bioactivity compounds, such as isoflavones, peptides, polyphenols, melanoidins, has been characterized as the responsible molecules for the glucoregulatory activity (Table 8). It should be noted that FSP such as douchi, natto, tempeh, doenjang, are whole foods that are also rich sources of dietary fiber; dietary fiber, including both soluble dietary and insoluble dietary fiber, is well established for their beneficial roles in improving glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity [106,107]. However, the role of dietary fiber in FSP on glucose metabolism has not been studied. FSP contains numerous components, some presented naturally and some formed during fermentation, the effect of interactions of various components in FSP should not be overlooked. Animal studies in literature tend to use extracts from FSP, but not FSP, thus a possible synergistic effect with other food components might be compromised. Therefore, tremendous efforts are needed to reveal the synergistic effect of various components in FSP glucoregulatory activity [108].

Table 8.

The responsible molecules for the glucoregulatory activity in FSP.

Even though we have reviewed mechanisms of FSP action on glucoregulatory properties, given the complexity of the pathophysiology of glucose metabolism and the possible synergistic effect of various components in FSP, the nature of glucoregulatory mechanisms of FSP is far from understanding. Epidemiologic evidence supports the hypoglycemic role of FSP. However, clinical evidence on the hypoglycemic role of FSP is lacking, highlighting a critical need of translating research for bedside application.

Depending on the efficacy of dose, it is not known whether high-dose FSP intake might cause any adverse effects. Further, most of FSP generally contain high levels of NaCl. It’s worth noting that high dietary salt is an important contributor to increased blood pressure and T2DM [109,110]. Salt reduction has been identified as one of the most cost-effective interventions for reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease and T2DM with the potential for saving millions of lives each year [111]. The sodium content should be reduced on the premise of ensuring the safety, quality, and functionality of FSP. Some strategies to reduce salt content in FSP include the application of non-thermal processing techniques such as high-pressure technology and ultrasound, the use of sodium salt alternatives, flavor enhancers, and/or quality improvers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y., S.L. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y., J.L. and R.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.Y., W.W., S.L., D.L. and J.W.; supervision, W.W., D.L. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was found by the Ningxia Key Research and Development Program (2022BFH02009).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Milardi, D.; Gazit, E.; Radford, S.E.; Xu, Y.; Gallardo, R.U.; Caflisch, A.; Westermark, G.T.; Westermark, P.; Rosa, C.L.; Ramamoorthy, A. Proteostasis of islet amyloid polypeptide: A molecular perspective of risk factors and protective strategies for type II diabetes. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1845–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Ferrannini, E.; Groop, L.; Henry, R.R.; Herman, W.H.; Holst, J.J.; Hu, F.B.; Kahn, C.R.; Raz, I.; Shulman, G.I. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschner, P.; Karuranga, S.; James, S.; Simmons, D.; Basit, A.; Shaw, J.E.; Wild, S.H.; Ogurtsova, K.; Saeedi, P. The International Diabetes Federation’s guide for diabetes epidemiological studies. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 172, 108630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, C.; Dzuvor, C.K.O.; Tosh, S.; Agyei, D. Anti-diabetic effects of bioactive peptides: Recent advances and clinical implications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2022, 62, 2158–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadge, A.A.; Kuvalekar, A.A. Controversy of oral hypoglycemic agents in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Novel move towards combination therapies. Diabetes Metab. Synd. 2017, 11, S5–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.; Jia, X.; Wang, N.; Kang, J.; Hu, X.; Goff, H.D.; Cui, S.W.; Ding, H.H.; Guo, Q. Therapeutic potential of non-starch polysaccharides on type 2 diabetes: From hypoglycemic mechanism to clinical trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2022, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Tzvetkov, N.T.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Souto, E.B.; Santini, A.; Gan, R.Y.; Jozwik, A.; Grzybek, W.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; et al. Natural products in diabetes research: Quantitative literature analysis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 5813–5827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasi, M.; Kumar, S.; Hasan, M.; Garcia-Gutierrez, E.; Kumari, S.; Prakash, O.; Nain, L.; Sachdev, A.; Dahuja, A. Current trends in the development of soy-based foods containing probiotics and paving the path for soy-synbiotics. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Chen, J. Consumption of soybean, soy foods, soy isoflavones and breast cancer incidence: Differences between Chinese women and women in Western countries and possible mechanisms. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 2013, 2, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, B.F.; Zougman, A.; Masse, R.; Mulligan, C. Production and characterization of bioactive peptides from soy hydrolysate and soy-fermented food. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjukta, S.; Rai, A.K. Production of bioactive peptides during soybean fermentation and their potential health benefits. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Sarkar, S.; Borsingh Wann, S.; Kalita, J.; Manna, P. Current perspectives on the anti-inflammatory potential of fermented soy foods. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinkraus, K.H. Fermented foods, feeds, and beverages. Biotechnol. Adv. 1986, 4, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, M.; Xu, B. An insight into the health benefits of fermented soy products. Food Chem. 2019, 271, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y.; Feng, Z. Fermented soybean foods: A review of their functional components, mechanism of action and factors influencing their health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2022, 158, 111575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; De Mejia, E.G. A new frontier in soy bioactive peptides that may prevent age-related chronic diseases. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F 2005, 4, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.H.; Green-Johnson, J.M.; Buckley, N.D.; Lin, Q.L. Bioactivity of soy-based fermented foods: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.J.; Kwon, D.Y.; Moon, N.R.; Kim, M.J.; Kang, H.J.; Park, S. Soybean fermentation with Bacillus licheniformis increases insulin sensitizing and insulinotropic activity. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.Y.; Daily, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S. Antidiabetic effects of fermented soybean products on type 2 diabetes. Nutr. Res. 2010, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.Y.; Hong, S.M.; Ahn, I.S.; Kim, M.J.; Yang, H.J.; Park, S. Isoflavonoids and peptides from meju, long-term fermented soybeans, increase insulin sensitivity and exert insulinotropic effects in vitro. Nutrition 2011, 27, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.Y.; Daily, J.W.; Lee, G.H.; Ryu, M.S.; Yang, H.; Jeong, S.Y.; Qiu, J.Y.; Zhang, T.; Park, S. Short-term fermented soybeans with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens potentiated insulin secretion capacity and improved gut microbiome diversity and intestinal integrity to alleviate Asian type 2 diabetic symptoms. J. Agri. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13168–13178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Hao, L.; Zhang, G.; Jin, Z.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Rao, J.; Chen, B. Traditional fermented soybean products: Processing, flavor formation, nutritional and biological activities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2022, 62, 1971–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, J. Fermented soybean foods: Significance of biogenic amines. Austin J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 3, 1058. [Google Scholar]

- do Prado, F.; Pagnoncelli, M.; de Melo Pereira, G.; Karp, S.; Soccol, C. Fermented soy products and their potential health benefits: A review. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y. Effects of Tetragenococcus halophilus and Candida versatilis on the production of aroma-active and umami-taste compounds during soy sauce fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2020, 100, 2782–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Que, Z.; Jin, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, R.; Wu, C.D. Flavor compounds of traditional fermented bean condiments: Classes, synthesis, and factors involved in flavor formation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Pan, M.; El-Nezami, H.; Wan, J.; Wang, M.F.; Habimana, O.; Lee, J.; Louie, J.; Shah, N. Effects of lactic acid bacteria-fermented soymilk on isoflavone metabolites and short-chain fatty acids excretion and their modulating effects on gut microbiota. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 1854–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Lee, J.; Yun, H.; Ahn, B.; Kim, H.; Seo, W. Changes of phytochemical constituents (isoflavones, flavanols, and phenolic acids) during cheonggukjang soybeans fermentation using potential probiotics Bacillus subtilis CS90. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.; Yuan, B.; Gothai, S.; Arulselvan, P.; Song, X.; Chen, L. Dietary triterpenes in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: To date. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 72, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, T.; Archangelidi, O.; Suhrcke, M. The economic costs of type 2 diabetes: A global systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2017, 389, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 943162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xirouchaki, C.; Mangiafico, S.; Bate, K.; Ruan, Z.; Huang, A.; Tedjosiswoyo, B.; Lamont, B.; Pong, W.; Favaloro, J.; Blair, A. Impaired glucose metabolism and exercise capacity with muscle-specific glycogen synthase 1 (gys1) deletion in adult mice. Mol. Metab. 2016, 5, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Kabir, M.E.; Sarkar, S.; Wann, S.B.; Kalita, J.; Manna, P. Antidiabetic potential of soy protein/peptide: A therapeutic insight. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gaal, L.; Scheen, A. Weight management in type 2 diabetes: Current and emerging approaches to treatment. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith Campbell, R. Fate of the beta-cell in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2009, 49, S10–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithieux, G. The new functions of the gut in the control of glucose homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2005, 8, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, A.; Yamanaka-Okumura, H.; Nishida, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Taketani, Y.; Takeda, E. Natto and viscous vegetables in a Japanese style meal suppress postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17, 663–668. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, D.Y.; Hong, S.M.; Ahn, I.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Shin, D.W.; Park, S. Kochujang, a Korean fermented red pepper plus soybean paste, improves glucose homeostasis in 90% pancreatectomized diabetic rats. Nutrition 2009, 25, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, H.; Yamagami, T. Fermented soybean-derived Touchi-extract with anti-diabetic effect via α-glucosidase inhibitory action in a long-term administration study with KKAy mice. Life Sci. 2001, 70, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, L.; Bu, T.; Zheng, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Liu, D. Purification and characterization of hypoglycemic peptides from traditional Chinese soy-fermented douchi. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 3343–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, H.; Chen, L. α-Glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitors from seed oil: A review of liposoluble substance to treat diabetes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2017, 57, 3438–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, C.; Ribeiro, D.; Freitas, M.; Fernandes, E. Flavonoids as potential agents in the management of type 2 diabetes through the modulation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2022, 62, 3137–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Feng, D.; Wang, T.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Inhibitors of α-amylase and α-glucosidase: Potential linkage for whole cereal foods on prevention of hyperglycemia. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 6320–6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Si, X.; Wang, Y.; Gong, E.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Shu, C. Bioactive flavonoids from Rubus corchorifolius inhibit α-glucosidase and α-amylase to improve postprandial hyperglycemia. Food Chem. 2021, 341, 128149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademiluyi, A.O.; Oboh, G.; Boligon, A.A.; Athayde, M.L. Effect of fermented soybean condiment supplemented diet on α-amylase and α-glucosidase activities in Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, R.; Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Kan, J. Effect of different starter cultures on the control of biogenic amines and quality change of douchi by rapid fermentation. LWT 2019, 109, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cheng, Y.; Yamaki, K.; Li, L. Anti-α-glucosidase activity of Chinese traditionally fermented soybean (douchi). Food Chem. 2007, 103, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Yamagami, T.; Ohshima, K. Fermented soybean derived touchi extract with anti-glycaemic effect via α-glucosidase inhibitory action in rats and humans. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1211–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Park, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, M. Reduction of biogenic amines and aflatoxins in Doenjang samples fermented with various Meju as starter cultures. Food Control 2014, 42, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Park, J.A.; Kim, D.; Hong, S.M.; Lee, J.; Kim, M.A. Total phenolic content, antioxidant, tyrosinase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of water soluble extracts of noble starter culture Doenjang, a Korean fermented soybean sauce variety. Food Control 2016, 59, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.T.; Rico, C.W.; Kang, M. Comparative study on the hypoglycemic and antioxidative Effects of fermented paste (Doenjang) prepared from soybean and brown rice mixed with rice bran or red ginseng marc in mice fed with high fat diet. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4610–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Oh, Y.; Lim, J.; Park, J.; Kim, M.; Yoon, H.; Lim, S. Physiological properties of Jeju traditional Doenjang. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 38, 1656–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Kim, M.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.; Hong, S. In vitro antidiabetic and antiobesity activities of traditional Kochujang and Doenjang and their components. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 24, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumoto, K.; Yamagata, Y.; Tazawa, R.; Kitagawa, M.; Kato, T.; Isobe, K.; Kashiwagi, Y. Japanese traditional Miso and Koji making. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allwood, J.G.; Wakeling, L.T.; Bean, D.C. Fermentation and the microbial community of Japanese koji and miso: A review. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2194–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momose, A.; Goto, N.; Hayase, H.; Gomyo, T.; Miura, M. Effects of miso (soybean paste) on postprandial blood sugar levels. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. 2010, 57, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Ci, Z.; Kojima, M. α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity in rice miso supplementary with black soybean. Am. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 7, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astawan, M.; Nurwitri, C.; Rochim, D.; Wresdiyati, T.; Widowati, S.; Bintari, S.; Ichsani, N.; Dingin, S.; Berbeda, W.; In, D. Application of vacuum packaging to extend the shelf life of fresh-seasoned tempe. Int. Food Res. J. 2016, 23, 2571–2580. [Google Scholar]

- Astawan, M.; Rahmawati, I.; Cahyani, A.; Wresdiyati, T.; Putri, S.; Fukusaki, E. Comparison between the potential of tempe flour made from germinated and nongerminated soybeans in preventing Diabetes mellitus. HAYATI J. Biosci. 2020, 27, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yang, B.; Tan, J.; Jiang, J.; Li, D. Associations of dietary intakes of anthocyanins and berry fruits with risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayem, A.; Arya, A.; Karimian, H.; Krishnasamy, N.; Ashok Hasamnis, A.; Hossain, C. Action of phytochemicals on insulin signaling pathways accelerating glucose transporter (GLUT4) protein translocation. Molecules 2018, 23, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, J.; Bryant, N.; Gould, G.; Welburn, C. Posttranslational modifications of GLUT4 affect its subcellular localization and translocation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9963–9978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorens, B. GLUT2, glucose sensing and glucose homeostasis. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brereton, M.; Rohm, M.; Shimomura, K.; Holland, C.; Tornovsky-Babeay, S.; Dadon, D.; Iberl, M.; Chibalina, M.; Lee, S.; Glaser, B. Hyperglycaemia induces metabolic dysfunction and glycogen accumulation in pancreatic β-cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.L.; Taylor, C.G.; Zahradka, P. Rebelling against the (Insulin) Resistance: A review of the proposed insulin-sensitizing actions of soybeans, chickpeas, and their bioactive compounds. Nutrients 2018, 10, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Sarkar, S.; Dihingia, A.; Afzal, N.; Wann, S.; Kalita, J.; Dewanjee, S.; Manna, P. A popular fermented soybean food of Northeast India exerted promising antihyperglycemic potential via stimulating PI3K/AKT/AMPK/GLUT4 signaling pathways and regulating muscle glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Huang, W.; Hou, C.; Chi, Y.; Huang, H. Effect of black soybean koji extract on glucose utilization and adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 8280–8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Do, H.; Kim, O.; Chung, J.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Hwang, K.; Seong, S.; Shin, M. Fermented soy bean extract suppresses differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and facilitates its glucose utilization. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 15, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamutdinova, I.; Jin, Y.; Chung, J.; Shin, S.; Lee, S.; Seo, H.; Lee, J.; Chang, K.; Kim, H. The anti-diabetic effect of anthocyanins in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats through glucose transporter 4 regulation and prevention of insulin resistance and pancreatic apoptosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Jang, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.; Shin, D.; Park, S. The isoflavonoid aglycone-rich fractions of Chungkookjang, fermented unsalted soybeans, enhance insulin signaling and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activity in vitro. BioFactors 2006, 26, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Afzal, N.; Wann, S.; Kalita, J.; Manna, P. A ~24 kDa protein isolated from protein isolates of Hawaijar, popular fermented soy food of North-East India exhibited promising antidiabetic potential via stimulating PI3K/AKT/GLUT4 signaling pathway of muscle glucose metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinacore, D.R.; Gulve, E.A. The role of skeletal muscle in glucose transport, glucose homeostasis, and insulin resistance: Implications for physical therapy. Phys. Ther. 1993, 73, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.; Hong, S.; Lee, J.; Sung, S.; Park, S. Long-term consumption of fermented soybean-derived Chungkookjang attenuates hepatic insulin resistance in 90% pancreatectomized diabetic rats. Horm. Metab. Res. 2007, 39, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Park, H.; Ji, Y.; Holzapfel, W.; Kim, D.; Hyun, C. Long-term fermented soybean paste improves metabolic parameters associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 1744–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malardé, L.; Vincent, S.; Lefeuvre-Orfila, L.; Efstathiou, T.; Groussard, C.; Gratas-Delamarche, A. A fermented soy permeate improves the skeletal muscle glucose level without restoring the glycogen content in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Med. Food 2013, 16, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, S.; Hwang, J.; Yi, S.; Nam, Y.; Lim, S. Antidiabetic effect of Morinda citrifolia (Noni) fermented by Cheonggukjang in KK-Ay diabetic mice. Evid-Based Compl. Alt. 2012, 2012, 163280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokashi, P.; Khanna, A.; Pandita, N. Flavonoids from Enicostema littorale blume enhances glucose uptake of cells in insulin resistant human liver cancer (HepG2) cell line via IRS-1/PI3K/Akt pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 90, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Mehta, D.; Kapoor, S.; Yadav, S. Liver function in type-2 diabetes mellitus patients. Int. J. Sci. Study 2016, 3, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Kwon, D.; Kim, M.; Kang, S.; Park, S. Meju, unsalted soybeans fermented with Bacillus subtilis and Aspergilus oryzae, potentiates insulinotropic actions and improves hepatic insulin sensitivity in diabetic rats. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jeong, Y.; Kwon, J.; Moon, K.; Kim, H.; Jeon, S.; Lee, M.; Park, Y.; Choi, M. Beneficial effect of chungkukjang on regulating blood glucose and pancreatic β-cell functions in C75BL/KsJ-db/db mice. J. Med. Food 2008, 11, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Park, S.; Pak, V.; Chung, K.; Kwon, D. Fermented soybean products and their bioactive compounds. In Soybean and Health; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Yamagami, T.; Ohshima, K. Long-term ingestion of a fermented soybean-derived Touchi-extract with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity is safe and effective in humans with borderline and mild type-2 diabetes. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 2105–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyanto, I.; Hsieh, C.; Hsu, Y.; Chen, L.; Chu, C.; Weng, B. In vitro and in vivo assessments of anti-hyperglycemic properties of soybean residue fermented with Rhizopus oligosporus and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Life 2022, 12, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Cho, H.; Kim, Y. The role of estrogen in adipose tissue metabolism: Insights into glucose homeostasis regulation. Endocr. J. 2014, 61, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, A.; Virbasius, J.; Puri, V.; Czech, M. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman-Gruen, D.; Kritz-Silverstein, D. Usual dietary isoflavone intake is associated with cardiovascular disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.; Razavi, S. Therapeutic effects of polyphenols in fermented soybean and black soybean products. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 81, 104467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.; Suh, J.; Hah, N.; Liddle, C.; Atkins, A.; Downes, M.; Evans, R. PPARγ signaling and metabolism: The good, the bad and the future. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahandideh, F.; Bourque, S.; Wu, J. A comprehensive review on the glucoregulatory properties of food-derived bioactive peptides. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, I.; Do, M.; Kim, S.; Jung, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Park, K. Antiobesity effect of Kochujang (Korean fermented red pepper paste) extract in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Med. Food 2006, 9, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Chung, Y.; Kwak, C.; Kwon, Y. Doenjang, a Korean traditional fermented soybean paste, ameliorates neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Park, Y. Food components with anti-obesity effect. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 2, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, D.; Korc, M.; Petersen, G.; Eibl, G.; Li, D.; Rickels, M.; Chari, S.; Abbruzzese, J. Diabetes, pancreatogenic piabetes, and pancreatic cancer. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Jang, J.; Hong, S.; Lee, J.; Sung, S.; Park, H.; Park, S. Long-term consumption of fermented soybean-derived Chungkookjang enhances insulinotropic action unlike soybeans in 90% pancreatectomized diabetic rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2007, 46, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, H.; Jung, H.; Karuppasamy, S.; Park, Y.; Cho, Y.; Lee, J.; Seong, S.; Suh, J. Anti-diabetic effect of the soybean extract fermented by Bacillus subtilis MORI in db/db mice. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 21, 1669–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masdar, H.; Satriyasumatri, T.; Hakiki, M.; Rafisyahputra, M.; Juananda, D. Histological apperarance of diabetes-rat pancreas administrated by soybean compared to tempeh. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2019; p. 020012. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, L. ‘All disease begins in the gut’: Was Hippocrates right? Brain 2018, 141, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chang, H.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; Abrouk, M.; Farahnik, B.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, T.; et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Lyu, W.; Xie, M.; Yuan, Q.; Ye, H.; Hu, B.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, X. Effects of α-galactooligosaccharides from chickpeas on high-fat-diet-induced metabolic syndrome in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3160–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitkunat, K.; Stuhlmann, C.; Postel, A.; Rumberger, S.; Fankhänel, M.; Woting, A.; Petzke, K.; Gohlke, S.; Schulz, T.; Blaut, M. Short-chain fatty acids and inulin, but not guar gum, prevent diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance through differential mechanisms in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F.; Pasolli, E.; Ercolini, D. The food-gut axis: Lactic acid bacteria and their link to food, the gut microbiome and human health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 454–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soka, S.; Suwanto, A.; Sajuthi, D.; Rusmana, I. Impact of tempeh supplementation on gut microbiota composition in Sprague-Dawley rats. Res. J. Microbiol. 2014, 9, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, D.; Ryu, M.; Yang, H.; Park, S. γ-PGA-rich Chungkookjang, short-term fermented soybeans: Prevents memory impairment by modulating brain insulin sensitivity, neuro-inflammation, and the gut–microbiome–brain axis. Foods 2021, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, B.; Chu, Y.; Chang, W.; Wu, M. Effects of tempeh fermentation with Lactobacillus plantarum and Rhizopus oligosporus on streptozotocin-induced type II diabetes mellitus in rats. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylönen, K.; Saloranta, C.; Kronberg-Kippilä, C.; Groop, L.; Aro, A.; Virtanen, S. Associations of dietary fiber with glucose metabolism in nondiabetic relatives of subjects with type 2 diabetes: The botnia dietary study. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 1979–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weickert, M.; Pfeiffer, A. Impact of dietary fiber consumption on insulin resistance and the prevention of type 2 diabetes. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W. Demystification of fermented foods by omics technologies. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 46, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Campbell, N. Salt and high blood pressure. Clin. Sci. 2009, 117, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Jousilahti, P.; Peltonen, M.; Lindström, J.; Tuomilehto, J. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective study in Finland. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.; Kenny, S.; Kerry, J.; Leenhardt, F.; Arendt, E. ‘Low-salt’ bread as an important component of a pragmatic reduced-salt diet for lowering blood pressure in adults with elevated blood pressure. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).