Abstract

Verdejo sparkling wines from two consecutive vintages were elaborated following the “champenoise” method. The second fermentation was developed with the same free or immobilized Saccharomyces cerevisiae bayanus yeast strain, carrying out four batch replicates each year. The sparkling wines were analyzed after 9 months of aging, showing no significant differences among the two typologies in the enological parameters (pH, total acidity, volatile acidity, reducing sugars, and alcoholic strength), the effervescence, or the spectrophotometric measurements. The free amino nitrogen content was significantly higher in the sparkling wines obtained from immobilized yeasts, nevertheless, the levels of neutral polysaccharides and total proteins were lower. No significant differences in the volatile composition were found, except for only two volatile compounds (isobutyric acid and benzyl alcohol); however, these two substances were present at levels below their respective olfactory thresholds. The sensory analysis by consumers showed identical preferences for both types of sparkling wines, except for the color acceptability. The descriptive analysis by a tasting panel revealed that sensorial differences between both sparkling wines were only found for the smell of dough. Therefore, the use of immobilized yeasts for the second fermentation of sparkling wines can reduce and simplify some enological practices such as the procedure of riddling and disgorging, with no impact on the so-mentioned quality parameters.

1. Introduction

The “champenoise” method of sparkling wine production involves the second fermentation in a bottle of wine to which sugar and yeasts have been added. During this second fermentation, the yeast metabolism and autolysis participate in the typical effervescence, aroma, and flavor of the sparkling wine [1]. After the second fermentation and aging, the yeast sediment (lees) is settled on the stopper and “disgorged” in a process known as riddling. Traditionally, this phase takes place manually over the course of several weeks, twisting and inclining the bottle gradually until all the yeast cells settle down to the bottleneck. This process is both long and arduous and needs a significant percentage of the cellars to be devoted to it. One alternative is the use of an automatic machine called “gyropalette”, which greatly reduces the times of this process (at 4–5 days); however, a large investment is required [2].

To improve this process, over the last decades some alternatives have been studied [3], such as the use of chemical additives, flocculent yeast strains, or immobilized yeasts [2,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The employ of immobilized yeasts is an attractive strategy to reduce the time and the cost of manufacturing sparkling wine since they can be removed just in a few seconds instead of the long-lasting traditional process [1]. After the patent of Bidan et al. [10], most efforts have focused on the application of alginate as organic support for the immobilization of yeasts for the second fermentation of sparkling wines [4,7,8,11,12]. The use of calcium alginate gels is advantageous since they are easily prepared and allow the incorporation of yeasts under mild conditions, which almost completely rules out the death of the cells [13]. Moreover, calcium alginate has been approved by the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV) as a fining agent in the production of sparkling wine and as a matrix for yeast and bacteria encapsulation [14]. In certain cases, a release of yeasts from the matrix of alginate gel has been described [15,16]. However, this issue has not been addressed in many papers dealing with the use of alginate-encapsulated yeasts in sparkling wine production [4,7,8,11]. Some authors have proposed coating finished biocatalysts (prepared using calcium alginate) to solve this problem [13].

Currently, a commercial immobilized Saccharomyces cerevisiae bayanus yeast (Cremanti®, Erbslöh Cavis, Mainz, Germany) designed for the second fermentation of bottle-fermented sparkling wine is available for winemakers. In this commercial preparation, the yeasts are immobilized on double-layer beads made of calcium alginate in order to prevent the release of cells from the beads to the wine, thus avoiding turbidity. Then, the immobilized yeasts are dried in order to increase their shelf-life.

There is a lack of scientific information about the effect of the application of these immobilized yeasts (Cremanti®) on the chemical and sensorial characteristics of sparkling wines. Rather than small cellar experiments conducted by the yeast’s manufacturers, rigorous scientific studies under real winemaking conditions are required. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has addressed the use of Cremanti® encapsulated yeasts, researching the effect of inoculation format (free and encapsulated yeasts) on the amino acid content of sparkling wines [8]. However, other topics of interest such as their volatile composition and sensory characteristics have not been analyzed. In this context, the aim of our present study was to examine the potential application of these immobilized cells for the winemaking of sparkling wines during two consecutive vintages. The chemical and sensory properties of the sparkling wines elaborated with immobilized and free yeasts were compared.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Standards

All chemicals and reagents were analytical quality grade and purchased from Panreac (Madrid, Spain), except for the extraction solvent (dichloromethane) and internal standards (4-methyl-2-pentanol and 3-octanol) used for volatile compounds which were provided by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), including methanol, 1-butanol, isoamyl alcohols, benzyl alcohol, 2-phenyl-ethanol, 1-hexanol, ethyl butyrate, ethyl hexanoate, ethyl octanoate, phenylethyl acetate, and hexanoic, octanoic and decanoic acids. Isobutanol, 1-propanol, trans-3-hexenol, cis-3-hexenol, furfural, benzaldehyde, ethyl lactate, diethyl succinate, isoamyl acetate, and butyric, isobutyric and isovaleric acids were provided by Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). R-pantolactone, γ-butyrolactone, and 4-vinyl-guaiacol were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany).

2.2. Winemaking Process

The study was carried out using the Verdejo white grape variety cultivated in Castilla y León (Spain) from two consecutive vintages. Four different Verdejo base wines from different vineyards were elaborated on each vintage at the experimental wine cellar of the Agricultural Engineering College (University of Valladolid, Palencia, Spain).

Firstly, the white base wines were elaborated following the traditional white winemaking process, by standard technology for the production of white still wines [8]. Nearly 200 kg of Verdejo grapes were destemmed/crushed, pressed and the must was fermented in four stainless steel tanks (100 L). The sulfur dioxide concentrations of the musts were adjusted to 30 mg/L by addition of potassium metabisulphite. The musts were inoculated with Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Anchor VIN 13, Erbslöh Cavis, Germany, 20 g/hL). The density and temperature of the musts-wines were monitored during the fermentation letting them proceed at 16–18 °C for about 3 weeks until the sugar concentrations were reduced to less than 3 g/L. The clarifications were performed for 1 week at 4 °C by adding bentonite (70 g/hL, Superbenton DC, Dal Cin Gildo Spa, Milan, Italy) as fining agent, then the wines were racked and stored at 4 °C.

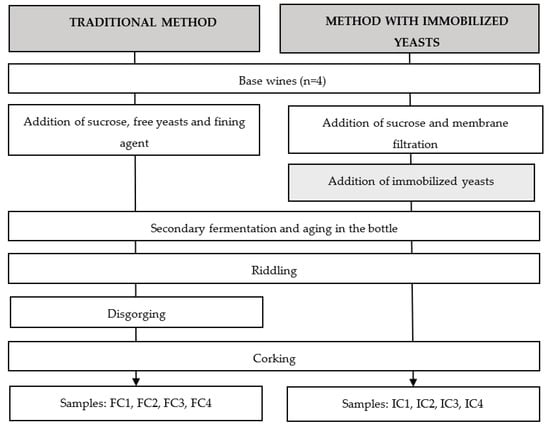

The sparkling wines were elaborated using the above-mentioned Verdejo base wines following the traditional method (second fermentation in bottles). A scheme of the experiments carried out is shown in Figure 1. The second fermentation was conducted by the same Saccharomyces cerevisiae bayanus yeast strain as (i) immobilized yeasts (Cremanti®, Erbslöh-Cavis, Germany) or (ii) free yeasts (Erbslöh-Cavis, Germany). Depending on the type of yeast, the protocol for the manufacturing of sparkling wines was different. For the batches with the free yeasts (labeled as FC wines), sucrose (to reach a final concentration of sugar of 24 g/L), yeasts (15 g/hL), and a fining agent (alginate and bentonite, Sekt-Klar plus, Erbslöh, Germany, 60 mL/hL) were added to the base wines. When the immobilized yeasts were employed (labeled as IC wines), the bottles were previously sterilized (dry heat at 100 °C, 24 h) and sucrose (to reach a final concentration of sugar of 24 g/L) was added to the wine. Then, the wine with sucrose was filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane (Opticap® XL10, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) under sterile conditions. A dose of 1.75 g of immobilized yeasts per 0.75-L bottle was employed. In all the experiments, the second fermentation and aging were carried out in 0.75-L bottles at a temperature of 14–15 °C for 9 months.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the experiments carried out using free and immobilized cells to produce sparkling wines.

2.3. Analytical Procedures

The methods described by the OIV [17] were employed for the determination of pH, total acidity, volatile acidity, reducing sugars, and alcoholic strength.

Total proteins were quantified by the colorimetric method described by Bradford [18]. The formol titration method was employed for the quantification of free amino nitrogen [19]. Neutral polysaccharides were evaluated using the method described by Segarra et al. [20].

Total polyphenols, total hydroxycinnamates, and total flavonols were quantified by measuring the absorbances at 280, 320, and 365 nm, respectively, in quartz cuvettes in a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Lan Optics 2000 UV, Labolan, Spain) [21]. Color intensity was determined at 420 nm. Turbidity of the wines was determined using a turbidimeter (Hanna HI-83749, Woonsocket, RI, USA).

Frequencies of bubble formation using a stroboscope (PCE-OM 15, PCE-Ibérica, Albacete, Spain) were evaluated to determine the effervescence of the sparkling wines [22]. Briefly, 125 mL of sparkling wine was poured into a cylindrical classical crystal flute and three minutes after, the bubble trains were lit with the stroboscope. At a determined frequency of strobe lighting, a bubble train appears motionless, corresponding with its frequency of formation. Experiments were performed at room temperature (20 ± 2 °C) and using the same glass. This parameter was evaluated in five bubble trains using three bottles (3 × 5 measurements). The yeast cell concentration of the sparkling wines was determined by counting with a Neubauer camera.

All analyses were carried out in duplicate from three different bottles (3 × 2 measurements) and from each sample.

2.4. Volatile Compound Analysis

The volatile composition of the wines produced with immobilized and free cells from the first vintage was determined. Each sparkling wine sample was analyzed in triplicate. Methanol and higher alcohols were determined by direct injection (with 4-methyl-2-pentanol as internal standard, 1 g/L) into a Hewlett Packard 5890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) with flame ionization detector (FID) following the method described by Bertrand and Ribéreau-Gayon [23]. Some alcohols (alcohols with six carbon atoms, and others), aldehydes, esters, fatty acids, acetates, lactones, sulfur compounds, and volatile phenols were extracted as follows: a sample of 100 mL of wine and 2 mL of 3-octanol (10 mg/L), added as an internal standard, were extracted with 10, 5, and 5 mL of dichloromethane [24]. The organic extract was dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated to 0.5 mL with a low stream of nitrogen prior to analysis by gas chromatography (FID or mass spectrometric detection –GC-MS–).

A capillary column HP-Innowax (60 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness) was employed. Operating conditions were the following: injector and detector (FID) temperatures, 220 °C; column temperature, programmed from 45 (1 min) to 230 °C at 3 °C/min and final isotherm of 25 min; carrier gas pressure (Helium), 18 psi. An amount of 2 μL of wine sample or 1 μL of sample of the organic extract was injected in splitless mode (30 s).

A Hewlett-Packard model 5890 Series II hyphenated with an HP 5970 mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was also used. Three microliters of the organic extract were injected in splitless mode (purge time, 30 s; purge rate, 70) on a capillary column and the chromatographic conditions were the same as described above. The spectrometric conditions were electronic impact (ionization energy, 70 eV) and source temperature, 250 °C. The acquisition was made in scanning mode (mass range, 30–300 amu, 1.9 spectrum/s).

Identification of volatile compounds by GC-FID was performed through the retention times of the pure commercial standard compounds. Identification of volatile compounds by GC-MS was confirmed by comparing their mass spectra (MS Chemstation Wiley 7N library) and their retention times with those of the pure compounds. Volatile compounds were quantified using standard reference compounds. Stock standard solutions were prepared for all compounds (1 g/L for isoamyl alcohols and 100 mg/L for the rest of the volatile compounds) in 12% (v/v) aqueous ethanol and then diluted. Five known amounts of each analyte (in the intervals: 0–300 mg/L for isoamyl alcohols; 0–50 mg/L for methanol, 1-propanol, isobutanol, 2-phenyl-ethanol, and ethyl lactate; 0–20 mg/L for lactones; 0–10 mg/L for fatty acids and diethyl succinate; 0–5 mg/L for 1-butanol, benzyl alcohol, 1-hexanol, and 4-vinyl-guaiacol; 0–0.500 mg/L for acetates; 0–0.250 mg/L for trans- and cis-3-hexenol, furfural, benzaldehyde, and ethyl esters) were subjected to the same treatment (direct injection or previous liquid–liquid extraction) as that for the sparkling wines to obtain the calibration curves (relative peak areas with respect to the peak area of corresponding internal standard), and the quantification was carried out by interpolation. The correlation coefficients (R2 values) of the calibration curves were above 0.999 for all compounds and the concentrations of volatile compounds in sample wines were expressed as mg/L For the compounds for which pure substances were not available in our laboratory, the content was referred to as a function of the normalized area (%) with respect to the internal standard (3-octanol).

2.5. Sensory Analysis

2.5.1. Consumers’ Sensory Test

Hedonic sensory evaluation of sparkling wines from the first vintage was conducted with 140 consumer volunteers from 18 to 65 years old of various socioeconomic backgrounds.

Consumer tests were carried out in the Sensory Science Laboratory of the Agricultural Engineering College at the University of Valladolid, Palencia (Spain) in individual booths. The sparkling wines were evaluated on the basis of acceptance of their color, odor, flavor, hitch in mouth, persistence, and overall liking on a 9-point hedonic scale. The scale of values ranged from “like extremely” to “dislike extremely” corresponding to the highest and lowest scores of “9” and “1”, respectively.

The consumers tasted 8 samples of the sparkling wines (FC1–4, IC1–4) from the first vintage sequentially and monadically served. Samples were presented on plastic glasses coded with 3-digit random numbers and served in a randomized order. Water was available for rinsing.

2.5.2. Descriptive Sensory Analysis

A panel of ten volunteer panelists participated in the study. All panelists had previously participated in sparkling wine descriptive sensory analysis studies, and their performance had been assessed. The descriptive sensory analysis was carried out in the Sensory Science Laboratory of the Agricultural Engineering College at the University of Valladolid, Palencia (Spain).

The sensory evaluation of the sparkling wines (FC1–4, IC1–4) from the second vintage was performed using a questionnaire composed of 14 descriptors grouped into visual descriptors (color intensity), olfactory descriptors (odor intensity, fruity, floral, yeast, and dough) and flavor descriptors (flavor intensity, bitter, acid, sweet, volume, astringency, carbonic, and amount of carbonic). All attributes were evaluated on a 10 cm unstructured line scale from 0 to 10.

The sparkling wines were evaluated in duplicate by each assessor using a randomized complete block design. The samples were assessed in individual booths in coded wine-tasting glasses.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Analytical data were treated by applying variance analysis (ANOVA). The LSD (least significant difference) test determines statistically significant differences between the means. Confidence intervals of 95% or significant level of α = 0.05 were used.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed in order to establish a relationship between the different sensory and chemical data and the studied sparkling wines from the two vintages. The PCA was performed only with those variables (chemical and sensory) in which statistically significant differences were found after performing a one-way ANOVA test.

These analyses were performed with the computer program Statgraphics® Plus for Windows 4.0 (Statistical Graphics Corp., Rockville, MD, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Comparison of Sparkling Wines Elaborated with Free and Immobilized Yeasts

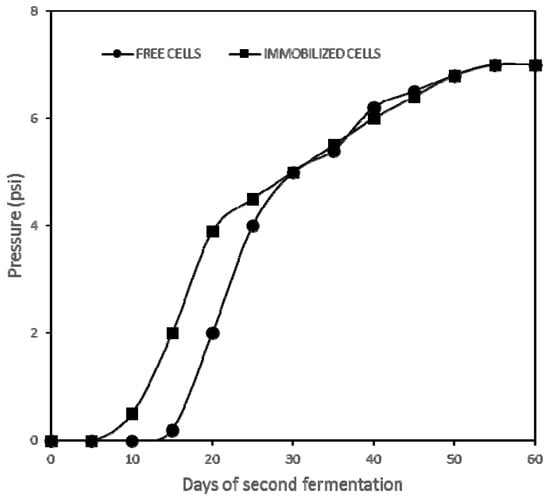

As an example, Figure 2 shows the kinetics of sparkling wine fermentations carried out with free and immobilized cells from the first vintage. Both the free and immobilized yeasts displayed similar carbonic acid production kinetics; however, the second fermentation of the immobilized cells started five days earlier, and so did free and immobilized cells in the second vintage. Similar behavior was observed at the second fermentation with immobilized yeast strains in alginate beads [25] and chitosan–calcium–alginate double-layer microcapsules [4]. Some authors reported an increased ethanol tolerance of immobilized yeast cells, facilitating the start of the second fermentation. Moreover, they suggested that this phenomenon can be attributed to cell encapsulation by a protective layer of gel material or modified fatty acid concentration in cell membranes due to oxygen diffusion limitations caused by the matrix of immobilization [12].

Figure 2.

Evolution of the carbon dioxide pressure in the bottle during the second fermentation using free and immobilized yeasts in first vintage.

The main enological parameters of the sparkling wines elaborated with free and immobilized yeasts from the two vintages are shown in Table 1. The results showed that there were no significant differences in pH, total and volatile acidities, reducing sugar, and alcoholic strength between both inoculation formats (free and immobilized yeasts). Some authors have also reported that the use of immobilized yeasts did not affect the enological parameters of the sparkling wines [4,9,13,26]. Moreover, it has been reported that the Ca–alginate entrapment technique did not cause notable changes in the main analytical composition of bottle-fermented sparkling wines [27,28,29]. Contrarily, all the parameters, except for the volatile acidity, were dependent on the vintage year. The sparkling wines from the second vintage were more acidic, less alcoholic, and a little sweeter than those from the first vintage.

Table 1.

Enological parameters of the sparkling wines elaborated with free and immobilized cells from the two vintages.

On the other hand, an important point for the industrial application of immobilized yeasts is the study of the cell retention capacity of the matrix employed for yeast immobilization. For that, the turbidity and the number of yeasts were evaluated in the sparkling wines after 9 months of aging (Table 1). The immobilized yeast samples displayed lower turbidity values than the free yeasts ones and no cells were detected in the sparkling wines elaborated with immobilized yeasts. Our results evidence a satisfactory behavior of the matrix employed in the immobilization process. The degree of effervescence of the sparkling wines was also studied by analyzing the values of the frequency of bubble formation (Table 1). This parameter indicates that the wines with more effervescence have higher frequencies of bubble formation. Puig-Pujol et al. [9] indicated that secondary fermentation conducted with immobilized yeast cells resulted in better foam quality than fermentation with traditional free cells. In our study, no significant differences were found in the values of the frequency of bubble formation between the sparkling wines elaborated with free and immobilized cells.

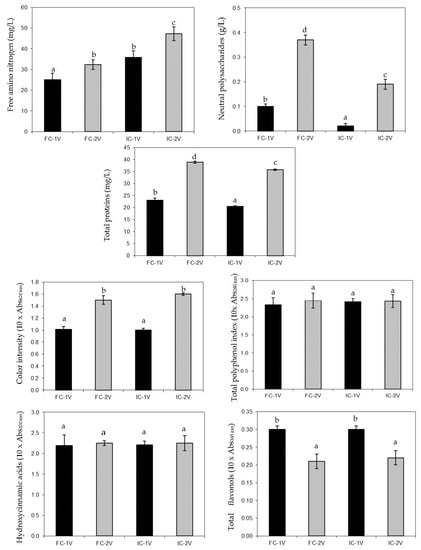

The amino acid concentration, which is influenced by both its consumption by yeasts and its release during the autolysis of yeasts, is considered one of the most important factors affecting the organoleptic quality of sparkling wines [4,30]. For this reason, the concentration of free amino nitrogen in different sparkling wines was analyzed. As was found by López et al. [7], the content of free amino nitrogen in the sparkling wines produced with free yeasts was lower than that found with immobilized yeasts (Figure 3) for both vintages. These data are also in accordance with Bozdogan and Canbas [31] who described slightly higher free amino acid values of the sparkling wines elaborated with Sacharomyces bayanus EC 1118 immobilized in alginate gels than that obtained from free yeasts. Prokes et al. [8] also reported higher levels of free amino acids in sparkling wines elaborated with alginate encapsulated cells. This fact can be associated with a physiological response to the process of immobilization, which could cause an increase in the autolysis process and/or a reduction in the consumption of free amino acids by yeasts along the aging period, finally increasing their levels in the sparkling wines [3]. Some authors reported a more rapid decay of immobilized yeasts than their free counterparts. Free cells died completely in 9–12 months, whereas live immobilized cells were not detected after 6 months or earlier. Early decay determined the more rapid autolysis of immobilized yeasts [26]. Moreover, an increase in the content of amino acids in the sparkling wines elaborated with immobilized yeasts was observed. This is an indication of earlier onset and higher intensity of autolysis in immobilized cells, in agreement with their more rapid decay [13].

Figure 3.

Concentration of free amino nitrogen, neutral polysaccharides, and total proteins, and color intensity, total polyphenol index, and levels of hydroxycinnamic acids and total flavonols of the sparkling wines elaborated with free (FC) and immobilized cells (IC) from the two vintages (1V and 2V). Different letters indicate statistically significant difference (p < 0.05).

On the other hand, the study of the level of neutral polysaccharides in sparkling wines was also used to evaluate the degree of autolysis, for it quantifies mainly glucans and mannoproteins from the yeast cell walls [3,32]. The statistical analysis showed that the neutral polysaccharides were lower in the wines elaborated with immobilized yeasts than those with free yeasts (Figure 3) for both vintages. An increase in the yeast autolysis due to the immobilization process, previously postulated, should increase the content of neutral polysaccharides in the sparkling wines elaborated with immobilized yeasts [27]. However, this effect was not observed in this study. This may be due to the limited transfer of the polysaccharides (released during yeast autolysis) from the inside of the matrix of immobilization to the sparkling wine. Moreover, this effect could be more intense in immobilized yeasts prepared with a protective coat which decreases the mass exchange [13].

The protein composition of sparkling wines changes during aging due to the process of yeast autolysis [33]. Figure 3 shows the concentration of total proteins in the sparkling wines after nine months of aging. There were statistically significant differences between treatments (free and immobilized yeasts) for this parameter. For both vintages, the concentration of total proteins of sparkling wines elaborated with free yeasts was higher than that observed for immobilized yeasts. These results are in agreement with those found for neutral polysaccharides. Probably, the porosity of the matrix of immobilization did not allow a free transfer of the yeast proteins to the wine.

The color intensity, the total polyphenol index, and the levels of hydroxycinnamic acids and flavonols analysis were carried out in order to know the possibility of the matrix of alginate to absorb color and/or phenolic compounds in its surface during the aging time. No significant differences were found for these parameters between the sparkling wines elaborated with free or immobilized cells (Figure 3). Puig-Pujol et al. [9] did not detect significant differences in color intensity among the sparkling wines made with free and immobilized yeast cells.

The aromatic composition constitutes an important factor in the production of high-quality sparkling wines. Alcohols, ethyl esters, acetates, lactones, sulfur, or volatile phenol compounds were determined in the Verdejo sparkling wines from the first vintage (Table 2).

Table 2.

Volatile compounds (mg/L) of the sparkling wines elaborated with free and immobilized cells from first vintage.

In general, the aromatic composition of the wines did not vary significantly according to the yeast-inoculating format. These results are according to other authors [6,9,29]. No statistically significant differences were found between both types of wines, with the exception of only two volatile compounds (isobutyric acid and benzyl alcohol). A higher level of isobutyric acid was observed in the sparkling wines produced by immobilized cells, while a higher concentration of benzyl alcohol was found in samples elaborated with free cells. However, these two substances were present at levels below their respective odor thresholds, 2.3 mg/L [34] and 10 mg/L [35], respectively, and can therefore not be considered as odor actives; although these compounds could add a synergy effect to wine aroma with rancid or buttery and fruity notes, respectively. Unlike our data, Benucci et al. [4] and Costa et al. [11] found significant differences in wine aromatic composition related to yeast-inoculating format. The first study reported lower concentrations of total aldehydes, phenols, and ketones, and higher concentrations of acids in sparkling wines inoculated with chitosan–alginate encapsulated yeasts, while the second study observed lower levels of fatty acids in sparkling wines produced with alginate encapsulated yeasts compared to the free ones. However, López et al. [7] noted that the yeast strain inoculated to base wine had a higher impact on the volatile composition of sparkling wines than the type of inoculum (free or immobilized) used.

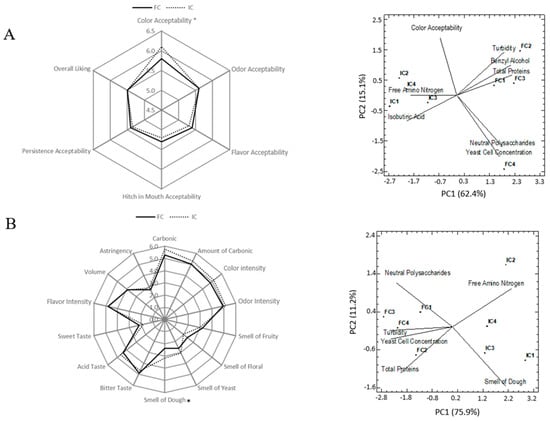

3.2. Sensory and Chemical Characteristics of the Sparkling Wines from the Two Vintages

In the first vintage a consumer study was carried out, but due to the good results obtained, in the second vintage a sensory characterization of the sparkling wines was carried out using a panel of trained tasters. No statistically significant differences were found in the sensory characteristics between the sparkling wines treated with immobilized and free yeasts (Figure 4). Only the sparkling wines elaborated with immobilized yeasts presented higher color acceptability (first vintage) and smell of dough (second vintage) than the sparkling wines elaborated with free yeasts.

Figure 4.

Sensory diagrams and principal component analysis of samples of sparkling wines elaborated with free (FC) and immobilized yeasts (IC) from (A) first and (B) second vintages by using chemical and sensorial variables. The asterisk indicates statistically significant differences for p = 0.05.

Figure 4 also shows the dispersion diagram of the samples of wine from first and second vintage after 9 months of aging, and the chemical and sensory characteristics in the first two main components. For the first vintage (Figure 4A) the two main components can explain 77.5% of the total variance. The first principal component (PC1) explains 62.4% of the variability data and the second component (PC2) explains 15.1% of the variance. In Figure 4B the sparkling wines from the second vintage were located in the vectorial dimension defined by the two principal components, which explained 87.1% of the total variance. In both vintages the defined space of the two principal components clearly differentiates the sparkling wines elaborated using free (FC1, FC2, FC3, FC4) and immobilized yeasts (IC1, IC2, IC3, IC4).

The sparkling wines from both vintages elaborated using immobilized yeasts are characterized by a higher content of free amino nitrogen and smaller values of neutral polysaccharides and total proteins. Regarding the aromatic compounds, the sparkling wines produced with free yeasts (first vintage) showed higher values of benzyl alcohol and lower isobutyric acid. However, from a sensory viewpoint, the consumers did not observe these chemical differences. As pointed out above, there was only a significant difference in the color acceptability of the wines, being higher this attribute for the sparkling wines with immobilized yeasts. The lower turbidity observed in these sparkling wines could be related to the highest acceptability in the color attribute.

In an attempt to test if the chemical differences detected in these wines (according to the type of inoculation) had a real influence on their organoleptic characteristics, a descriptive sensory analysis was carried out with the sparkling wines from the second vintage. As noted previously, the sparkling wines elaborated with immobilized yeasts showed only a higher smell of dough than the wines with free yeasts (Figure 4B). In accordance with our results, Benucci et al. [4] and López et al. [7] observed similar sensory profiles between sparkling wines elaborated with free and encapsulated yeasts. Probably, the higher smell of dough found in wines obtained with immobilized yeast-inoculating format is due to a higher degree of autolysis, as it was discussed above. Finally, the higher levels of neutral polysaccharides and proteins found in the sparkling wines elaborated with free yeasts were probably not enough to detect by the judges’ differences in volume between both types of sparkling wines.

4. Conclusions

The use of immobilized yeasts in the champenoise winemaking method makes it possible to reduce and simplify the procedure of riddling and disgorging since rapid sediment of encapsulated cells takes place during the remuage phase. The matrix of immobilization was stable during the nine months of aging and no release of yeasts to wine was observed. Moreover, the kinetic behavior of the immobilized yeasts was excellent. On the other hand, the use of immobilized yeasts did not have either effect on the main enological parameters or on the effervescence of the sparkling wines. The data show that the immobilized cells give differences just in a few analytical results. The wines elaborated with immobilized yeasts presented a higher level of free amino nitrogen, and a lower number of neutral polysaccharides and total proteins. The volatile composition of both types of sparkling wines was also very similar, with the exception of the content of isobutyric acid and benzyl alcohol. Finally, the organoleptic characteristics of sparkling wines do not reveal important disparities. The consumers only found differences in color acceptability and the judges in the smell of dough of both fermentation systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N. and J.V.-C.; methodology, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N., J.V.-C. and E.F.-L.; validation, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N. and J.V.-C.; formal analysis, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N. and J.V.-C.; investigation, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N. and J.V.-C.; resources, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N. and J.V.-C.; data curation, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N., J.V.-C. and E.F.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N. and J.V.-C.; writing—review and editing, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N., J.V.-C. and E.F.-L.; visualization, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N. and J.V.-C.; supervision, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N., J.V.-C. and E.F.-L.; project administration, E.F.-F., J.M.R.-N. and J.V.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jesús Yuste Bombín and ITACyL (Instituto Tecnológico y Agrario de Castilla y León) for the grapes used in this study, and Mónica Martínez Pérez, María Montserrat Marcos and Alberto de la Iglesia for the analytical work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexandre, H.; Guilloux-Benatier, M. Yeast autolysis in sparkling wine—A review. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2006, 12, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresi, S.; Frangipane, M.T.; Anelli, G. Biotechnologies in sparkling wine production. Interesting approaches for quality improvement: A review. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozo-Bayón, M.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.; Pueyo, E.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Chemical and biochemical features involved in sparkling wine production: From a traditional to an improved winemaking technology. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benucci, I.; Cerreti, M.; Maresca, D.; Mauriello, G.; Esti, M. Yeast cells in double layer calcium alginate-chitosan microcapsules for sparkling wine production. Food Chem. 2019, 300, 125174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coloretti, F.; Zambonelli, C.; Tini, V. Characterization of flocculent Saccharomyces interspecific hybrids for the production of sparkling wines. Food Microbiol. 2006, 23, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divies, C.; Cachon, R.; Cavin, J.F.; Prevost, H. Theme 4—Immobilized cell technology in wine production. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 1994, 14, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, N.; Peinado, R.A.; Puig-Pujol, A.; Mauricio, J.C.; Moreno, J.; García-Martínez, T. Influence of two yeast strains in free, bioimmobilized or immobilized with alginate forms on the aromatic profile of long aged sparkling wines. Food Chem. 2018, 250, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokes, K.; Baron, M.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Adamkova, A.; Ercisli, S.; Sochor, J. The influence of traditional and immobilized yeast on the amino-acid content of sparkling wine. Fermentation 2022, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Pujol, A.; Bertrán, E.; García-Martínez, T.; Capdevila, F.; Mínguez, S.; Mauricio, J.C. Application of a new organic yeast immobilization method for sparkling wine production. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2013, 64, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidan, P.; Divies, C.; Dupuy, P. Procédé Perfectionné de Préparation de Vins Mousseux. French Patent FR2432045A1, 26 July 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, G.P.; Nicolli, K.P.; Welke, J.E.; Manfroi, V.; Zini, C.A. Volatile profile of sparkling wines produced with the addition of mannoproteins or lees before second fermentation performed with free and immobilized yeasts. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2018, 29, 1866–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourkoutas, Y.; Bekatorou, A.; Banat, I.M.; Marchant, R.; Koutinas, A.A. Immobilization technologies and support materials suitable in alcohol beverages production: A review. Food Microbiol. 2004, 21, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynenko, N.; Gracheva, I. Physiological and biochemical characteristics of immobilized champagne yeasts and their participation in champagnizing processes: A review. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2003, 39, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Oenological Codex. Chapter I. Products Used in Oenology; (Oeno 33/2000, Oeno 410/2010); Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV): Paris, France, 2013.

- Bozdogan, A.; Canbas, A. Influence of yeast strain, immobilisation and ageing time on the changes of free amino acids and amino acids in peptides in bottle-fermented sparkling wines obtained from Vitis vinifera cv. Emir. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godia, F.; Casas, C.; Sola, C. Application of immobilized yeast-cells to sparkling wine fermentation. Biotechnol. Prog. 1991, 7, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compendium of International Methods of Analysis of Wines and Musts; Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV): Paris, France, 2013.

- Bradford, M.M. Rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shively, C.E.; Henick-Kling, T. Comparison of two procedures for assay of free amino nitrogen. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2001, 52, 400–401. [Google Scholar]

- Segarra, I.; Lao, C.; López-Tamames, E.; De La Torre-Boronat, M.C. Spectrophotometric methods for the analysis of polysaccharide levels in winemaking products. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1995, 46, 564–570. [Google Scholar]

- Andrés Lacueva, C.; Lamuela Raventós, R.M.; Buxaderas, S.; de la Torre Boronat, M.D.C. Influence of variety and aging on foaming properties of cava (sparkling wine). 2. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 2520–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liger-Belair, G.; Marchal, R.; Robillard, B.; Vignes-Adler, M.; Maujean, A.; Jeandet, P. Study of effervescence in a glass of champagne: Frequencies of bubble formation, growth rates, and velocities of rising bubbles. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1999, 50, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, A.; Ribéreau-Gayon, P. Determination of volatile components of wine by gas-phase chromatography. Ann. Falsif. Expert Chim. Toxicol. 1970, 63, 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Armada, L.; Falqué, E. Repercussion of the clarification treatment agents before the alcoholic fermentation on volatile composition of white wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2007, 225, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, G.H. Wine yeasts for the future. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efremenko, E.N.; Stepanov, N.; Martinenko, N.N.; Gracheva, I.M. Cultivation conditions preferable for yeast cells to be immobilized into poly (vinyl alcohol) and used in bottled sparkling wine production. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Quart. 2006, 12, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busova, K.; Magyar, I.; Janky, F. Effect of immobilized yeasts on the quality of bottle-fermented sparkling wine. Acta Aliment. 1994, 23, 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fumi, M.D.; Trioli, G.; Colagrande, O. Preliminary assessment on the use of immobilized yeast-cells in sodium alginate for sparkling wine processes. Biotechnol. Lett. 1987, 9, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokotsuka, K.; Yajima, M.; Matsudo, T. Production of bottle-fermented sparkling wine using yeast immobilized in double-layer gel beads or strands. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1997, 48, 471–481. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, A.J.; Polo, M.C. Effect of the addition of bentonite to the tirage solution on the nitrogen composition and sensory quality of sparkling wines. Food Chem. 2003, 81, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdogan, A.; Canbas, A. The effect of yeast strain, immobilisation, and ageing time on the amount of free amino acids and amino acids in peptides of sparkling wines obtained from cv. Dimrit grapes. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2012, 33, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lapuente, L.; Guadalupe, Z.; Ayestarán, B.; Ortega-Heras, M.; Pérez-Magarino, S. Changes in polysaccharide composition during sparkling wine making and aging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12362–12373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; López, R.; Cacho, J.F. Quantitative determination of the odorants of young red wines from different grape varieties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.B.; Picarra-Pereira, M.A.; Monteiro, S.; Loureiro, V.B.; Teixeira, A.R. The wine proteins. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 12, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarse, H. Volatile Compounds in Foods and Beverages, 1st ed.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).