Fermented Pulses for the Future: Microbial Strategies Enhancing Nutritional Quality, Functionality, and Health Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

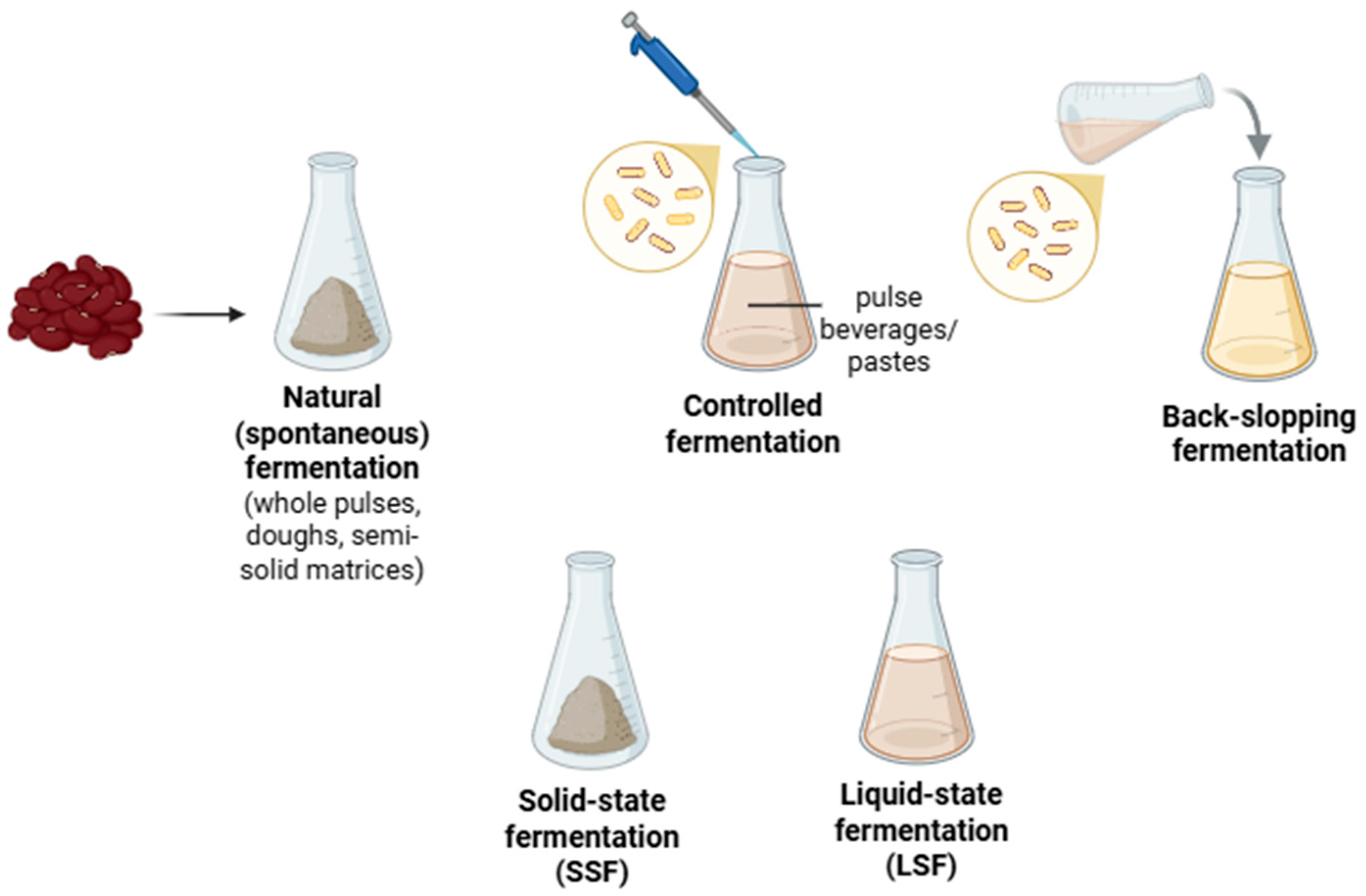

2. Microbial Fermentation of Legumes

| Fermented Matrix | Microorganism(s) | Type of Fermentation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chickpea flour | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CRL2211 and/or Weissella paramesenteroides CRL2182 | LSF, 37 °C for 24 h. | [35] |

| Lentil-based yogurt alternatives | Leuconostoc citreum TR116, Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides MP070, and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei FST 6.1 | LSF, 30 °C for 12 h. | [36] |

| Fava bean beverage | Indigenous LAB strains (Enterococcus, Pediococcus, and Bacillus) isolated from Swedish legumes | LSF, 37 °C for 48 h. | [37] |

| Fava bean flour + oat product | Selected LAB strains isolated from cereals and pulses | LSF, 30 –37 °C for 72 h | [38] |

| Chickpea–quinoa beverage | L. acidophilus LA-5 | LSF, 38 °C for 10 h | [39] |

| Whole lentils | L. plantarum TK9 and Bacillus subtilis natto | Co-fermentation, SSF, and LSF | [42] |

| Chickpea flour | LAB and yeasts | SLF 72 h at room temperature for yeasts and 48 h at 30° C for LAB and S. cerevisiae. | [45] |

| Chickpea sourdoughs | Yeast isolated from natural chickpea fermentation: Saccharomyces cerevisiae (most abundant) | Yeast fermentation in chickpea sourdoughs | [46] |

| Lentil protein isolate (production of bioactive peptides) | Yeast strains: Hanseniaspora uvarum SY1 and Kazachstania unispora KFBY1 LAB strains: Fructilactibacillus sanfranciscensis E10, L. plantarum LM1.3, L.hamnosus ATCC53103 | SLF, 30 °C for 8 days | [47] |

| Craft beer fortified with hydrolyzed red lentils | Lachancea thermotolerans and Kazachstania unispora | Beer fermentation | [48] |

| Grass Pea with the addition of flaxseed oil cake tempeh | Individual mold strains of Rhizopus oryzae, R.oligosporus, and Mucor indicus, or cofermentation with L. plantarum | SSF, 30 °C for 30 to 40 h. | [49] |

| Chickpeas, pigeon peas | R. oligosporus | SSF, 34 °C for 52 h. | [50] |

| Fava bean flour | Aspergillus oryzae, R. oligosporus | SSF, 28 or 30 °C for 48 or 72 h. | [51] |

| Fava bean tempeh-like product | R. microsporus | SSF, 30 °C for 40 h | [30] |

| Faba beans | Pleurotus ostreatus | SSF, 30 °C for 96 h | [52] |

| Kidney bean flour | A. awamori | SSF, 30 °C for 96 h. | [53] |

| Green kernel black beans | Eurotium cristatum | SSF, 22–39 °C, 24–72 h | [54] |

| Faba bean, yellow lentil, and yellow field pea | L. plantarum + A. oryzae | LSF, | [55] |

| Grass peas and flaxseed oil cake tempeh | R. oligosporus and L. plantarum | Co-fermentation (tempeh/SSF) at 30 °C for 27 h. | [56] |

| Pigeon pea okara (application in vegetable pasta) | R. oligosporus and Yarrowia lipolytica | SSF, 39 °C for 48 h | [57] |

| Black beans, black eyed peas, green split peas, red lentils, and pinto beans | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 299v | LSF, 37 °C for 24 h | [29] |

| Chickpeas and green or Red lentil-derived beverages | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 299v | LSF, 37 °C for 72 h | [59] |

| Chickpeas | Natural fermentation, isolation of 19 yeasts | LSF, 37 °C for 22 h. | [60] |

| Bean flour | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CRL 2211 and/or Weissella paramesenteroides CRL 2182 | LSF, 37 °C for 24 h | [40] |

3. Impact of Fermentation on Carbohydrates and Lipids

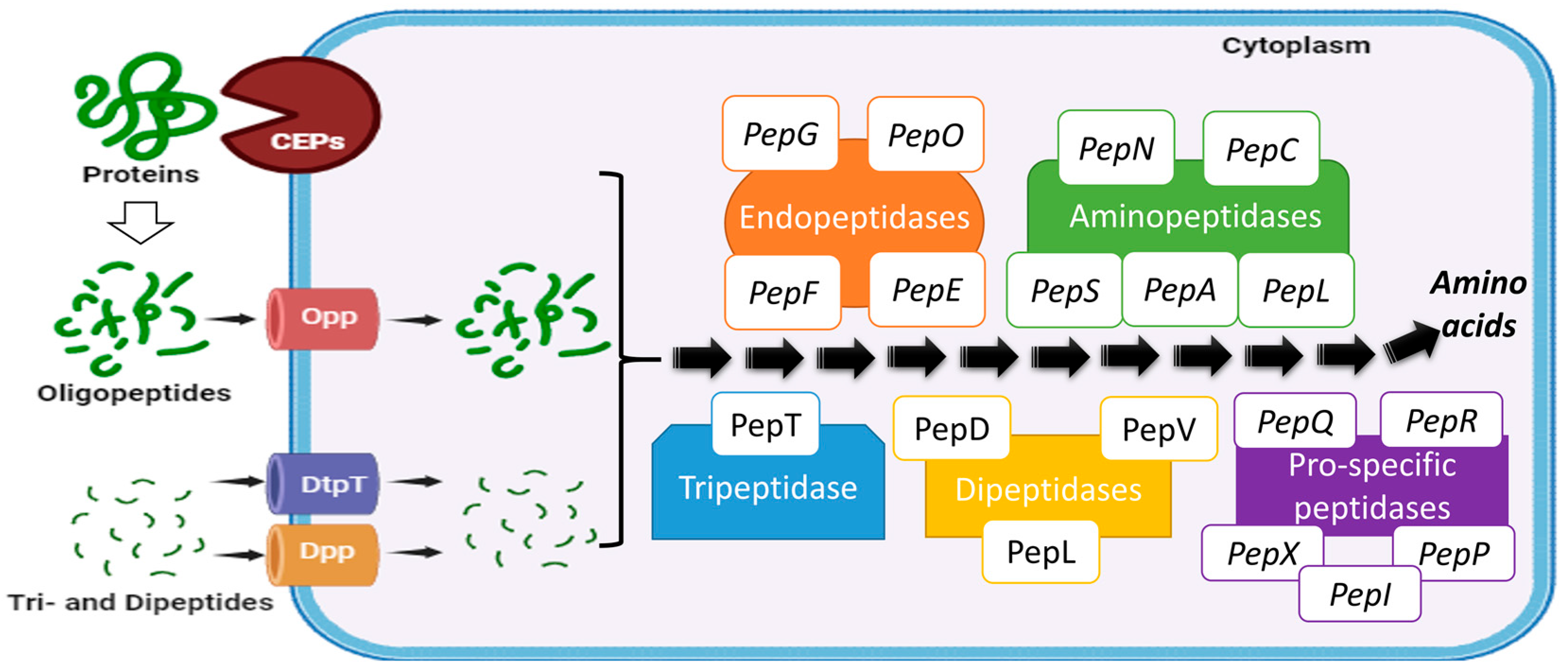

4. Impact of Fermentation on Protein Quality and Bioactive Peptide Production

Production of Bioactive Peptides Through the Fermentation of Pulse-Derived Proteins

| Protein Source | Strains | Bioactivity | Peptide Sequence | Molecular Weight (Da) * | Peptide Hydrophobicity * | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bitter beans | Limosilactobacillus fermentum ATCC9338 | Antioxidant | PVNNNAWAYATNFVPGK | 1861.9 | 11.85 | [103] |

| EAKPSFYLK | 1081.6 | 14.56 | ||||

| Bitter beans | Limosilactobacillus fermentum ATCC9338 | Antibacterial activity | AIGIFVKPDTAV | 1229.7 | 12.01 | [116] |

| Lentils | Hanseniaspora uvarum | ACE I inhibitory activity and antioxidant | ALEPDHR | 836.4 | 18.70 | [47] |

| AVV | 287.2 | 7.48 | ||||

| FFI | 425.2 | 3.36 | ||||

| FGG | 279.1 | 8.49 | ||||

| KVI | 358.3 | 9.12 | ||||

| LVL | 343.2 | 4.94 | ||||

| LVR | 386.3 | 8.00 | ||||

| VVR | 372.2 | 8.79 |

5. Reduction in Antinutritional Factors

| Mechanism | Microbial Enzyme/Process | Target ANF | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic hydrolysis of phosphate groups | Phytase | Phytates | Sequential dephosphorylation of inositol hexakisphosphate; release of bound minerals (Fe2+, Zn2+, Ca2+); up to 90% reduction | [118,119] |

| Acidification and solubilization of phytic complexes | Organic acid production (lactic, citric, gluconic acids). | Phytates | Increased solubility and accessibility of phytic acid; enhancement of endogenous phytase activity under acidic pH | [120] |

| Hydrolysis and oxidation of polyphenols | Tannase, polyphenol oxidase | Tannins | Cleavage of ester bonds; conversion of hydrolysable tannins into gallic acid; precipitation of insoluble complexes; 30–80% reduction | [121,122] |

| Proteolytic degradation of enzyme inhibitors | Acid proteases | Trypsin inhibitors | Hydrolysis of protease-inhibiting activity; up to 90% reduction | [40,123] |

| Denaturation of lectin structure | Protease secretion and acidification | Lectins | Disruption of quaternary structure; loss of hemagglutinating activity; up to 70% reduction | [124] |

| Biotransformation of glycosides | β-Glucosidase | Saponins | Hydrolysis into sapogenins and less bitter derivatives; decreased foaming and surface activity | [62,124] |

| Hydrolysis of α-galactosides | α-Galactosidase | Raffinose, stachyose, verbascose | Removal of α-1,6-linked galactose units; reduced flatulence potential; up to 80% degradation | [62,125] |

6. Effect of Fermentation on Phenolic Compounds

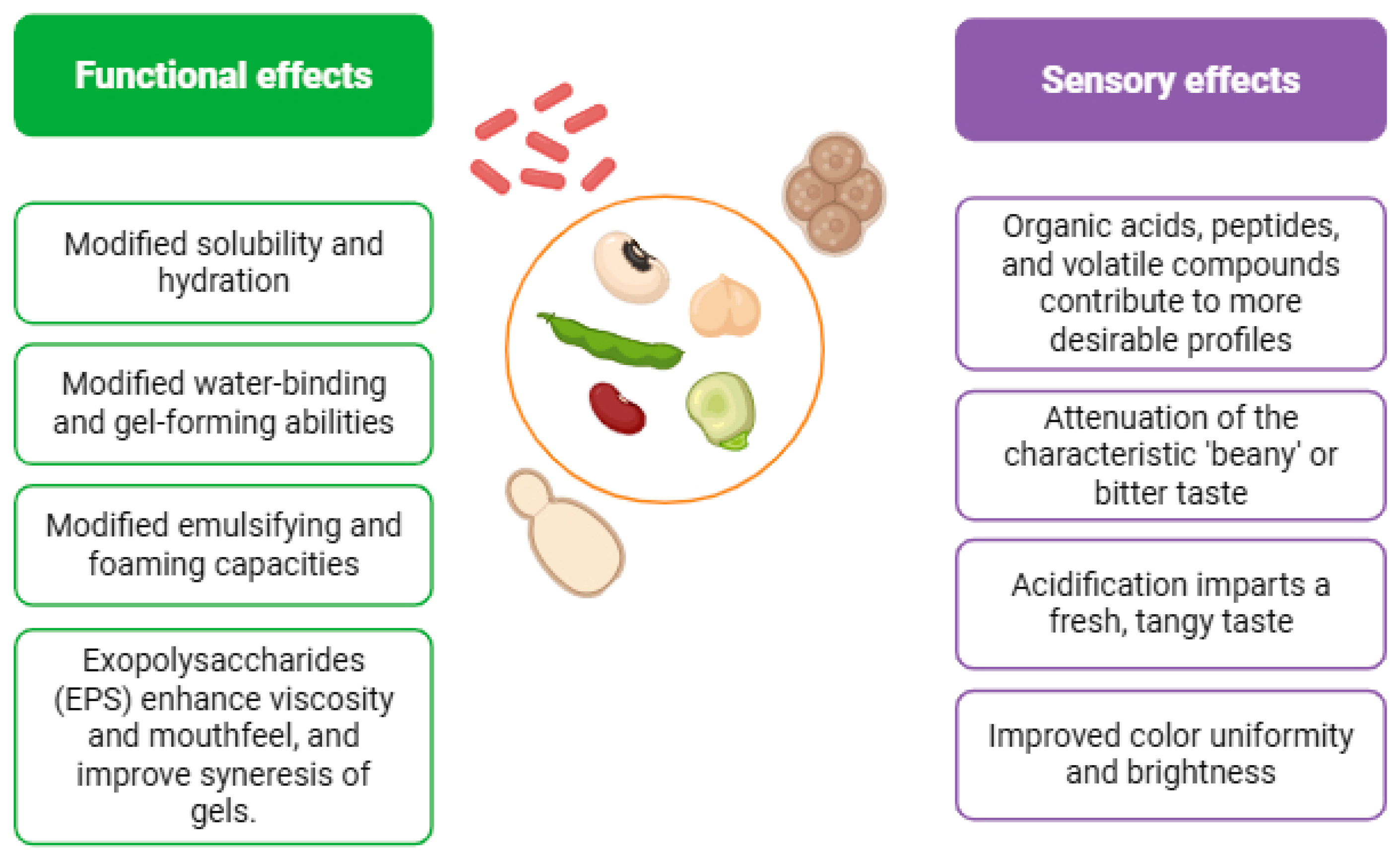

7. Functional Properties and Sensory Improvements

8. Conclusions, Challenges, and Future Trends

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANF(s) | Antinutritional Factor(s) |

| FB | Fava Bean |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| GRAS | Generally Recognized as Safe |

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| LSF | Liquid-State Fermentation/Submerged Fermentation |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated Fatty Acids |

| PDCAAS | Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| QPS | Qualified Presumption of Safety |

| RFO(s) | Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides |

| SFA | Saturated Fatty Acids |

| SSF | Solid-State Fermentation |

| TIA | Trypsin Inhibitor Activity |

| TAG | Triacylglycerol. |

| IUIS | Union of Immunological Societies |

References

- Huebbe, P.; Rimbach, G. Historical Reflection of Food Processing and the Role of Legumes as Part of a Healthy Balanced Diet. Foods 2020, 9, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarino, C.B.J.; Alikpala, H.M.A.; Begonia, A.F.; Cruz, J.D.; Dolot, L.A.D.; Mayo, D.R.; Rigor, T.M.T.; Tan, E.S. Quality and Health Dimensions of Pulse-Based Dairy Alternatives with Chickpeas, Lupins and Mung Beans. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 2375–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Definition and Classification of Commodities; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Adebiyi, J.A.; Gbashi, S.; Phoku, J.Z.; Kayitesi, E. Fermented Pulse-Based Food Products in Developing Nations as Functional Foods and Ingredients. In Functional Food—Improve Health through Adequate Food; InTech: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Pulses Development (DPD), G. of India. (2023). G. (APY) 2022–23. Crop-Wise Pulses Global Scenario: 2022. Directorate of Pulses Development. Available online: https://www.dpd.gov.in/ (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Why We Celebrate World Pulses Day. Available online: https://www.fao.org/plant-production-protection/news-and-events/news/news-detail/why-we-celebrate-world-pulses-day/en?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, A.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, L.; El-Seedi, H.; Zhang, G.; Sui, X. Legumes as an Alternative Protein Source in Plant-Based Foods: Applications, Challenges, and Strategies. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanni, A.E.; Iakovidi, S.; Vasilikopoulou, E.; Karathanos, V.T. Legumes: A Vehicle for Transition to Sustainability. Nutrients 2024, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Boateng, I.D.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y. Proteins from Legumes, Cereals, and Pseudo-Cereals: Composition, Modification, Bioactivities, and Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirmala Prasadi, V.P.; Joye, I.J. Dietary Fibre from Whole Grains and Their Benefits on Metabolic Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, V.; Skylas, D.J.; Roberts, T.H.; Valtchev, P.; Whiteway, C.; Li, Z.; Hopf, A.; Dehghani, F.; Quail, K.J.; Kaiser, B.N. Pulse Proteins: Processing, Nutrition, and Functionality in Foods. Foods 2025, 14, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.; Peñas, E.; Martinez-Villaluenga, C. Fermented Pulses in Nutrition and Health Promotion. In Fermented Foods in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 385–416. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.S.; Hur, S.J.; Lee, S.K. A Comparison of Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Sword Beans and Soybeans Fermented with Bacillus subtilis. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 2736–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolás-García, M.; Perucini-Avendaño, M.; Jiménez-Martínez, C.; Perea-Flores, M.d.J.; Gómez-Patiño, M.B.; Arrieta-Báez, D.; Dávila-Ortiz, G. Bean Phenolic Compound Changes during Processing: Chemical Interactions and Identification. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreman, L.; Nommensen, P.; Pennings, B.; Laus, M.C. Comprehensive Overview of the Quality of Plant- And Animal-Sourced Proteins Based on the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 5379–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisciani, S.; Marconi, S.; Le Donne, C.; Camilli, E.; Aguzzi, A.; Gabrielli, P.; Gambelli, L.; Kunert, K.; Marais, D.; Vorster, B.J.; et al. Legumes and Common Beans in Sustainable Diets: Nutritional Quality, Environmental Benefits, Spread and Use in Food Preparations. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1385232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelsang-O’Dwyer, M.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Production of Pulse Protein Ingredients and Their Application in Plant-Based Milk Alternatives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Langrish, T.A.G. A Review of the Treatments to Reduce Anti-Nutritional Factors and Fluidized Bed Drying of Pulses. Foods 2025, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya, P.S.; Singh, R. Pulses: Nutritional or Anti-Nutritional? A Review on Bioactive Components and Digestibility. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Basu, S.; Goswami, D.; Devi, M.; Shivhare, U.S.; Vishwakarma, R.K. Anti-Nutritional Compounds in Pulses: Implications and Alleviation Methods. Legume Sci. 2022, 4, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emkani, M.; Oliete, B.; Saurel, R. Effect of Lactic Acid Fermentation on Legume Protein Properties, a Review. Fermentation 2022, 8, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, C.; Ohemeng-Boahen, G.; Power, K.A.; Tosh, S.M. The Effect of Processing on Bioactive Compounds and Nutritional Qualities of Pulses in Meeting the Sustainable Development Goal 2. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 681662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, S.W.; Gastl, M.I.; Becker, T.M. The Modification of Volatile and Nonvolatile Compounds in Lupines and Faba Beans by Substrate Modulation and Lactic Acid Fermentation to Facilitate Their Use for Legume-Based Beverages—A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4018–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, J.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Gbashi, S.; Oyedeji, A.B.; Ogundele, O.M.; Oyeyinka, S.A.; Adebo, O.A. Fermentation of Cereals and Legumes: Impact on Nutritional Constituents and Nutrient Bioavailability. Fermentation 2022, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limón, R.I.; Peñas, E.; Torino, M.I.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Dueñas, M.; Frias, J. Fermentation Enhances the Content of Bioactive Compounds in Kidney Bean Extracts. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, H.O.; Önning, G.; Holmgren, K.; Strandler, H.S.; Hultberg, M. Fermentation of Cauliflower and White Beans with Lactobacillus plantarum—Impact on Levels of Riboflavin, Folate, Vitamin B12, and Amino Acid Composition. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatti-Kaul, R.; Chen, L.; Dishisha, T.; Enshasy, H. El Lactic Acid Bacteria: From Starter Cultures to Producers of Chemicals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, fny213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, J.A.C.; Rossetti Rogerio, M.F.; Bassinello, P.Z.; Oomah, B.D. The Use of Fermentation in the Valorization of Pulses By-Products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 159, 104957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Alvarado, A.J.; Castañeda-Reyes, E.D.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Optimized Fermentation Conditions of Pulses Increase Scavenging Capacity and Markers of Anti-Diabetic Properties. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Castaneda, L.A.; Auer, J.; Leong, S.L.L.; Newson, W.R.; Passoth, V.; Langton, M.; Zamaratskaia, G. Optimizing Soaking and Boiling Time in the Development of Tempeh-like Products from Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.). Fermentation 2024, 10, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.K.; Shi, D.; Liu, E.; Jafarian, Z.; Xu, C.; Bhagwat, A.; Lu, Y.; Akhov, L.; Gerein, J.; Han, X.; et al. Effect of Solid-State Fermentation on the Functionality, Digestibility, and Volatile Profiles of Pulse Protein Isolates. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munch-Andersen, C.B.; Porcellato, D.; Devold, T.G.; Østlie, H.M. Isolation, Identification, and Stability of Sourdough Microbiota from Spontaneously Fermented Norwegian Legumes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 410, 110505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayivi, R.D.; Gyawali, R.; Krastanov, A.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Worku, M.; Tahergorabi, R.; Da Silva, R.C.; Ibrahim, S.A. Lactic Acid Bacteria: Food Safety and Human Health Applications. Dairy 2020, 1, 202–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichońska, P.; Ziarno, M. Legumes and Legume-Based Beverages Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria as a Potential Carrier of Probiotics and Prebiotics. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez, G.D.; Sabater, C.; Fara, A.; Zárate, G. Fermentation of Chickpea Flour with Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria for Improving Its Nutritional and Functional Properties. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeck, T.; Ispiryan, L.; Hoehnel, A.; Sahin, A.W.; Coffey, A.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Lentil-Based Yogurt Alternatives Fermented with Multifunctional Strains of Lactic Acid Bacteria—Techno-Functional, Microbiological, and Sensory Characteristics. Foods 2022, 11, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labba, I.C.M.; Andlid, T.; Lindgren, Å.; Sandberg, A.S.; Sjöberg, F. Isolation, Identification, and Selection of Strains as Candidate Probiotics and Starters for Fermentation of Swedish Legumes. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 64, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahala, M.; Ikonen, I.; Blasco, L.; Bragge, R.; Pihlava, J.M.; Nurmi, M.; Pihlanto, A. Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria on the Level of Antinutrients in Pulses: A Case Study of a Fermented Faba Bean–Oat Product. Foods 2023, 12, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-Murillo, J.; Franco, W.; Contardo, I. Impact of Homolactic Fermentation Using Lactobacillus acidophilus on Plant-Based Protein Hydrolysis in Quinoa and Chickpea Flour Blended Beverages. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabater, C.; Sáez, G.D.; Suárez, N.; Garro, M.S.; Margolles, A.; Zárate, G. Fermentation with Lactic Acid Bacteria for Bean Flour Improvement: Experimental Study and Molecular Modeling as Complementary Tools. Foods 2024, 13, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, K.; Yokoyama, S. Trends in the Application of Bacillus in Fermented Foods. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Gao, C.; Han, X.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Lu, F. Co-Fermentation of Lentils Using Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bacillus subtilis Natto Increases Functional and Antioxidant Components. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, J.P.; Watanabe, K.; Holzapfel, W.H. Review: Diversity of Microorganisms in Global Fermented Foods and Beverages. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, T.C.; Savitri. Yeasts and Traditional Fermented Foods and Beverages. In Yeast Diversity in Human Welfare; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 53–82. [Google Scholar]

- Amadei, S.; Gandolfi, I.; Gottardi, D.; Cevoli, C.; D’Alessandro, M.; Siroli, L.; Lanciotti, R.; Patrignani, F. Selection of Yeasts and Lactic Acid Bacteria to Improve the Nutritional Quality, Volatile Profile, and Biofunctional Properties of Chickpea Flour. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 11, 101204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyaci Gunduz, C.P.; Erten, H. Yeast Biodiversity in Chickpea Sourdoughs and Comparison of the Microbiological and Chemical Characteristics of the Spontaneous Chickpea Fermentations. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonini, S.; Tlais, A.Z.A.; Galli, B.D.; Helal, A.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Filannino, P.; Zannini, E.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R. Lentils Protein Isolate as a Fermenting Substrate for the Production of Bioactive Peptides by Lactic Acid Bacteria and Neglected Yeast Species. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, L.; Agarbati, A.; Zannini, E.; Ciani, M.; Comitini, F. Lentil Fortification and Non-Conventional Yeasts as Strategy to Enhance Functionality and Aroma Profile of Craft Beer. Foods 2022, 11, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stodolak, B.; Grabacka, M.; Starzyńska-Janiszewska, A.; Duliński, R. Effect of Fungal and Fungal-Bacterial Tempe-Type Fermentation on the Bioactive Potential of Grass Pea Seeds and Flaxseed Oil Cake Mix. Int. J. Food Sci. 2024, 2024, 5596798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toor, B.S.; Kaur, A.; Kaur, J. Fermentation of Legumes with Rhizopus oligosporus: Effect on Physicochemical, Functional and Microstructural Properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 1763–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautheron, O.; Nyhan, L.; Torreiro, M.G.; Tlais, A.Z.A.; Cappello, C.; Gobbetti, M.; Hammer, A.K.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K.; Sahin, A.W. Exploring the Impact of Solid-State Fermentation on Fava Bean Flour: A Comparative Study of Aspergillus oryzae and Rhizopus oligosporus. Foods 2024, 13, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Pina, S.; Khvostenko, K.; García-Hernández, J.; Heredia, A.; Andrés, A. In Vitro Digestibility and Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Activity of Solid-State Fermented Fava Beans (Vicia faba L.). Food Chem. 2024, 455, 139867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.D.; Bains, A.; Goksen, G.; Ali, N.; Dhull, S.B.; Khan, M.R.; Chawla, P. Effect of Solid-State Fermentation on Kidney Bean Flour: Functional Properties, Mineral Bioavailability, and Product Formulation. Food Chem. X 2025, 27, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, B.; Li, Q.; Yang, C.; Yu, P.; Yang, X.; Li, T. Dynamic Changes on Sensory Property, Nutritional Quality and Metabolic Profiles of Green Kernel Black Beans during Eurotium Cristatum-Based Solid-State Fermentation. Food Chem. 2024, 455, 139846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryachko, Y.; Arasaratnam, L.; House, J.D.; Ai, Y.; Nickerson, M.T.; Korber, D.R.; Tanaka, T. Microbial Protein Production during Fermentation of Starch-Rich Legume Flours Using Aspergillus oryzae and Lactobacillus plantarum Starter Cultures. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2025, 139, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodolak, B.; Starzyńska-Janiszewska, A.; Mika, M.; Wikiera, A. Rhizopus oligosporus and Lactobacillus plantarum Co-Fermentation as a Tool for Increasing the Antioxidant Potential of Grass Pea and Flaxseed Oil-Cake Tempe. Molecules 2020, 25, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.R.; Chen, C.J.; Chen, B.Y. Response Surface Methodology-Optimized Co-Fermentation of Pigeon Pea Okara by Rhizopus oligosporus and Yarrowia lipolytica and Its Application for Vegetable Paste. JSFA Rep. 2022, 2, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Das Emon, D.; Toma, M.A.; Nupur, A.H.; Karmoker, P.; Iqbal, A.; Aziz, M.G.; Alim, M.A. Recent Advances in Probiotication of Fruit and Vegetable Juices. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2023, 10, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczak, K.; Teterycz, D.; Gustaw, W.; Domagała, D.; Mielczarek, P.; Kasprzyk-Pochopień, J. The Possibility of Using Lactobacillus plantarum 299v to Reinforce the Bioactive Properties of Legume-Derived Beverages. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devecioglu, D.; Kuscu, A.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F. Isolation and Functional Characterization of Yeasts from Fermented Plant Based Products. Fermentation 2025, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio-Grau, A.; Calvo-Lerma, J.; Heredia, A.; Andrés, A. Enhancing the Nutritional Profile and Digestibility of Lentil Flour by Solid State Fermentation with: Pleurotus ostreatus. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 7905–7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, I.; Pontonio, E.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Nutritional and Functional Effects of the Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation on Gelatinized Legume Flours. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 316, 108426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Song, S.; Liu, C.; Huang, W.; Bi, Y.; Yu, L. Fermentation Reduced the In Vitro Glycemic Index Values of Probiotic-Rich Bean Powders. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 3038–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byanju, B.; Hojilla-Evangelista, M.P.; Lamsal, B.P. Fermentation Performance and Nutritional Assessment of Physically Processed Lentil and Green Pea Flour. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 5792–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noori, S.M.A.; Hojjati, M.; Sorourian, R. Enhancing Nutritional Quality and Functionality of Legumes: Application of Solid-State Fermentation with Pleurotus ostreatus. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitum, V.C.; Kinyanjui, P.K.; Mathara, J.M.; Sila, D.N. Oligosaccharide and Antinutrient Content of Whole Red Haricot Bean Fermented in Salt–Sugar and Salt-Only Solutions. Legume Sci. 2022, 4, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, D.; Torley, P.J.; Chandrapala, J.; Terefe, N.S. Microbial Fermentation for Improving the Sensory, Nutritional and Functional Attributes of Legumes. Fermentation 2023, 9, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Chekdid, A.; Kahn, C.J.F.; Lemois, B.; Linder, M. Impact of a Starch Hydrolysate on the Production of Exopolysaccharides in a Fermented Plant-Based Dessert Formulation. Foods 2023, 12, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, M.O.; Oni, O.K.; Zubair, A.B.; Femi, F.A.; Audu, Y.; Etim, B.; Adeyeye, S.A.O. Influence of Fermentation Period on the Chemical and Functional Properties, Antinutritional Factors, and in Vitro Digestibility of White Lima Beans Flour. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 9047–9059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouadio Patrick, N.; Kouassi Martial-Didier, A.; Kouadio Florent, N.; Kouadio Constant, A.; Kablan, T. Effect of Spontaneous Fermentation Time on Physicochemical, Nutrient, Anti-Nutrient and Microbiological Composition of Lima Bean (Phaseolus lunatus) Flour. J. Appl. Biosci. 2021, 162, 16707–16725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, F.; McClements, D.J.; Hadidi, M. Strategies to Overcome Nutritional and Technological Limitations of Pulse Proteins. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. Pulses: An Overview. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Ha, S.M.L.; Peng, J.; Landman, J.; Sagis, L.M.C. Role of Pulse Globulins and Albumins in Air-Water Interface and Foam Stabilization. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 160, 110792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevkani, K.; Singh, N.; Chen, Y.; Kaur, A.; Yu, L. Pulse Proteins: Secondary Structure, Functionality and Applications. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 2787–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, F.; Ververis, E.; Precup, G.; Julio-Gonzalez, L.C.; Noriega Fernández, E. Proteins from Pulses: Food Processing and Applications. In Sustainable Food Science—A Comprehensive Approach; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 1–4, pp. 192–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Sharma, V.; Thakur, A. An Overview of Anti-Nutritional Factors in Food. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2019, 7, 2472–2479. [Google Scholar]

- Salim, R.; Nehvi, I.B.; Mir, R.A.; Tyagi, A.; Ali, S.; Bhat, O.M. A Review on Anti-Nutritional Factors: Unraveling the Natural Gateways to Human Health. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1215873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banti, M.; Bajo, W. Review on Nutritional Importance and Anti-Nutritional Factors of Legumes. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, J.; Malalgoda, M.; Storsley, J.; Malunga, L.; Netticadan, T.; Thandapilly, S.J. Health Benefits of Cereal Grain-and Pulse-Derived Proteins. Molecules 2022, 27, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertzler, S.R.; Lieblein-Boff, J.C.; Weiler, M.; Allgeier, C. Plant Proteins: Assessing Their Nutritional Quality and Effects on Health and Physical Function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsame, A.O.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Tosi, P. Seed Storage Proteins of Faba Bean (Vicia faba L): Current Status and Prospects for Genetic Improvement. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 12617–12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, P.; Twilt, F.; Nazir, R.; Peng, J.; Landman, J.; Sagis, L.M.C. Role of Globulins and Albumins in Oil-Water Interface and Emulsion Stabilization Properties of Pulse Proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 167, 111463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günal-Köroğlu, D.; Karabulut, G.; Ozkan, G.; Yılmaz, H.; Gültekin-Subaşı, B.; Capanoglu, E. Allergenicity of Alternative Proteins: Reduction Mechanisms and Processing Strategies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 7522–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mecherfi, K.E.; Todorov, S.D.; De Albuquerque, M.A.C.; Denery-Papini, S.; Lupi, R.; Haertlé, T.; De Melo Franco, B.D.G.; Larre, C. Allergenicity of Fermented Foods: Emphasis on Seeds Protein-Based Products. Foods 2020, 9, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, N.; Shokrollahi Yancheshmeh, B.; Gernaey, K.V. The Potential of Fermentation-Based Processing on Protein Modification: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Arteaga, V.; Leffler, S.; Muranyi, I.; Eisner, P.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U. Sensory Profile, Functional Properties and Molecular Weight Distribution of Fermented Pea Protein Isolate. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Marin, S.; Ayala-Larrea, D.; Cardador-Martínez, A.; Tellez-Perez, C.; Resendiz-Vazquez, J.A.; Alonzo-Macias, M. Non-Thermal Food Processing for Plant Protein Allergenicity Reduction: A Systematic Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70430. [Google Scholar]

- Nosworthy, M.G.; Yu, B.; Zaharia, L.I.; Medina, G.; Patterson, N. Pulse Protein Quality and Derived Bioactive Peptides. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1429225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderinola, T.A.; Duodu, K.G. Production, Health-Promoting Properties and Characterization of Bioactive Peptides from Cereal and Legume Grains. BioFactors 2022, 48, 972–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres Fabbri, L.; Cavallero, A.; Vidotto, F.; Gabriele, M. Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Foods: Production Approaches, Sources, and Potential Health Benefits. Foods 2024, 13, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martoccia, M.; Disca, V.; Jaouhari, Y.; Bordiga, M.; Coïsson, J.D. Recent Approaches for Bioactive Peptides Production from Pulses and Pseudocereals. Molecules 2025, 30, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.W.; Chung, Y.; Kim, K.T.; Hong, W.S.; Chang, H.J.; Paik, H.D. Probiotic Characteristics of Lactobacillus brevis B13-2 Isolated from Kimchi and Investigation of Antioxidant and Immune-Modulating Abilities of Its Heat-Killed Cells. LWT 2020, 128, 109452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Casas, D.E.; Aguilar, C.N.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Microbial Fermentation: The Most Favorable Biotechnological Methods for the Release of Bioactive Peptides. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Xiao, M.; Sudo, N.; Liu, Q. Bioactive Peptides of Marine Organisms: Roles in the Reduction and Control of Cardiovascular Diseases. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 5271–5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cian, R.E.; Drago, S.R. Microbial Bioactive Peptides from Bacteria, Yeasts, and Molds. In Handbook of Food Bioactive Ingredients: Properties and Applications; Jafari, S.M., Rashidinejad, A., Simal-Gandara, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-3-030-81404-5. [Google Scholar]

- Maleki, S.; Razavi, S.H. Pulses’ Germination and Fermentation: Two Bioprocessing against Hypertension by Releasing ACE Inhibitory Peptides. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 61, 2876–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveschot, C.; Cudennec, B.; Coutte, F.; Flahaut, C.; Fremont, M.; Drider, D.; Dhulster, P. Production of Bioactive Peptides by Lactobacillus Species: From Gene to Application. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, T.; Wang, D. Review on Plant-Derived Bioactive Peptides: Biological Activities, Mechanism of Action and Utilizations in Food Development. J. Future Foods 2022, 2, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apud, G.R.; Kristof, I.; Ledesma, S.C.; Stivala, M.G.; Aredes Fernandez, P.A. Health-Promoting Peptides in Fermented Beverages. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2024, 56, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.B.; He, T.P.; Li, H.B.; Tang, H.W.; Xia, E.Q. The Structure-Activity Relationship of the Antioxidant Peptides from Natural Proteins. Molecules 2016, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiacchio, M.F.; Tagliamonte, S.; Pazzanese, A.; Vitaglione, P.; Blaiotta, G. Lactic Acid Fermentation Improves Nutritional and Functional Properties of Chickpea Flours. Food Res. Int. 2025, 203, 115899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, M.; Johnson, S.K.; Liu, S.Q.; Mesmari, N.; Dahmani, S.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Kizhakkayil, J. In Vitro Investigation of Bioactivities of Solid-State Fermented Lupin, Quinoa and Wheat Using Lactobacillus spp. Food Chem. 2019, 275, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Chen, P.; Chen, X. Bioactive Peptides Derived from Fermented Foods: Preparation and Biological Activities. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 101, 105422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daliri, E.B.M.; Lee, B.H.; Oh, D.H. Current Trends and Perspectives of Bioactive Peptides. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Kok, J. Editing of the Proteolytic System of Lactococcus lactis Increases Its Bioactive Potential. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01319-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, S. Investigating Structure, Biological Activity, Peptide Composition and Emulsifying Properties of Pea Protein Hydrolysates Obtained by Cell Envelope Proteinase from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 245, 125375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Shavandi, A.; Mirdamadi, S.; Soleymanzadeh, N.; Motahari, P.; Mirdamadi, N.; Moser, M.; Subra, G.; Alimoradi, H.; Goriely, S. Bioactive Peptides from Yeast: A Comparative Review on Production Methods, Bioactivity, Structure-Function Relationship, and Stability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Liu, J.L.; Jiang, T.M.; Li, L.; Fang, G.Z.; Liu, Y.P.; Chen, L.J. Influence of Kluyveromyces marxianus on Proteins, Peptides, and Amino Acids in Lactobacillus-Fermented Milk. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Yin, Z.; An, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Research Progress on Fermentation-Produced Plant-Derived Bioactive Peptides. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1438947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrolonardo, F.; Tonini, S.; Granehäll, L.; Polo, A.; Zannini, E.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Nikoloudaki, O. Influence of Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Red Lentil Protein Isolate on Gut Microbiota: A Dynamic in Vitro Investigation. Future Foods 2025, 12, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Miao, J.; Rui, X.; Dong, M. Effects of Cordyceps militaris (L.) Fr. Fermentation on the Nutritional, Physicochemical, Functional Properties and Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Red Bean (Phaseolus angularis [Willd.] W.F. Wight.) Flour. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 1244–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, K.A.A.; David, S.M.; Murugesh, E.; Thandeeswaran, M.; Kiran, K.G.; Mahendran, R.; Palaniswamy, M.; Angayarkanni, J. Identification and in Silico Characterization of a Novel Peptide Inhibitor of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme from Pigeon Pea (Cajanus cajan). Phytomedicine 2017, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, X.; He, Y. Microbial Interactions in Food Fermentation: Interactions, Analysis Strategies, and Quality Enhancement. Foods 2025, 14, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canon, F.; Briard-Bion, V.; Jardin, J.; Thierry, A.; Gagnaire, V. Positive Interactions Between Lactic Acid Bacteria Could Be Mediated by Peptides Containing Branched-Chain Amino Acids. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 793136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarova, O.; Gabrielli, N.; Sévin, D.C.; Mülleder, M.; Zirngibl, K.; Bulyha, K.; Andrejev, S.; Kafkia, E.; Typas, A.; Sauer, U.; et al. Yeast Creates a Niche for Symbiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria through Nitrogen Overflow. Cell Syst. 2017, 5, 345–357.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhialdin, B.J.; Abdul Rani, N.F.; Meor Hussin, A.S. Identification of Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities for the Bioactive Peptides Generated from Bitter Beans (Parkia speciosa) via Boiling and Fermentation Processes. LWT 2020, 131, 109776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, I.; Ascione, A.; Muthanna, F.M.S.; Feraco, A.; Camajani, E.; Gorini, S.; Armani, A.; Caprio, M.; Lombardo, M. Sustainable Strategies for Increasing Legume Consumption: Culinary and Educational Approaches. Foods 2023, 12, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhad, N.G.; Rahman, R.N.Z.R.A.; Normi, Y.M.; Oslan, S.N.; Shariff, F.M.; Leow, T.C. Isolation, Screening and Molecular Characterization of Phytase-Producing Microorganisms to Discover the Novel Phytase. Biologia 2023, 78, 2527–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Pragya; Tiwari, S.K.; Singh, D.; Kumar, S.; Malik, V. Production of Fungal Phytases in Solid State Fermentation and Potential Biotechnological Applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhata, S.G.; Ayua, E.; Kamau, E.H.; Shingiro, J.B. Fermentation and Germination Improve Nutritional Value of Cereals and Legumes through Activation of Endogenous Enzymes. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 2446–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, H.S. Valorization of Faba Bean Peels for Fungal Tannase Production and Its Application in Coffee Tannin Removal. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.; Singh, D.; Aseri, G.K.; Sohal, J.S.; Vij, S.; Sharma, D. Role of Lacto-Fermentations in Reduction of Antinutrients in Plant-Based Foods. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulesen, L.; Duque-Estrada, P.; Zhang, L.; Martin, M.S.; Aaslyng, M.D.; Petersen, I.L. Faba Bean Tempeh: The Effects of Fermentation and Cooking on Protein Nutritional Quality and Sensory Quality. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 6, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaemene, D.; Fadupin, G. Anti-Nutrient Reduction and Nutrient Retention Capacity of Fermentation, Germination and Combined Germination-Fermentation in Legume Processing. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, V.; Venturi, M.; Pini, N.; Guerrini, S.; Granchi, L. Exploitation of Sourdough Lactic Acid Bacteria to Reduce Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides (RFOs) Content in Breads Enriched with Chickpea Flour. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 2353–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkhel, S.; Roy, A. Phytic Acid and Its Reduction in Pulse Matrix: Structure–Function Relationship Owing to Bioavailability Enhancement of Micronutrients. J. Food Process. Eng. 2022, 45, e14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, R.; Konietzny, U. Phytase for Food Application. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2006, 44, 25–140. [Google Scholar]

- De Pasquale, I.; Verni, M.; Verardo, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Rizzello, C.G. Nutritional and Functional Advantages of the Use of Fermented Black Chickpea Flour for Semolina-Pasta Fortification. Foods 2021, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-García, J.; Muñoz-Pina, S.; García-Hernández, J.; Tárrega, A.; Heredia, A.; Andrés, A. In Vitro Digestion Assessment (Standard vs. Older Adult Model) on Antioxidant Properties and Mineral Bioaccessibility of Fermented Dried Lentils and Quinoa. Molecules 2023, 28, 7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, M.; Platel, K. Impact of Soaking, Germination, Fermentation, and Thermal Processing on the Bioaccessibility of Trace Minerals from Food Grains. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Wu, M.; Wang, Q.; Peng, X.; Wen, H.; McKinstry, W.J.; Chen, Q. Crystal Structure of Tannase from Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 2737–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, T.; Viknander, S.; Kirk, A.M.; Sandberg, D.; Caron, E.; Zelezniak, A.; Krenske, E.; Larsbrink, J. Structure-Based Clustering and Mutagenesis of Bacterial Tannases Reveals the Importance and Diversity of Active Site-Capping Domains. Protein Sci. 2024, 33, e5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwal, K.K.; Selwal, M.K. Purification and Characterization of Extracellular Tannase from Aspergillus fumigatus MA Using Syzigium cumini Leaves under Solid State Fermentation. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 54, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; Alsaadi, B.H.; Althubyani, M.M.; Awari, Z.I.; Hussein, H.G.A.; Aljohani, A.A.; Albasri, J.F.; Faraj, S.A.; Mohamed, G.A. Secondary Metabolites, Biological Activities, and Industrial and Biotechnological Importance of Aspergillus sydowii. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranthaman, R.; Vidyalakshmi, R.; Alagusundaram, K. Production on Tannin Acyl Hydrolase from Pulse Milling By-Products Using Solid State Fermentation. Acad. J. Plant Sci. 2009, 2, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, H.S. Potato Peels for Tannase Production from Penicillium Commune HS2, a High Tannin-Tolerant Strain, and Its Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2023, 13, 16765–16778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Wang, X.C.; Feng, Z.Q.; Guo, Y.F.; Meng, G.Q.; Wang, H.Y. Biotransformation of Gallate Esters by a PH-Stable Tannase of Mangrove-Derived Yeast Debaryomyces Hansenii. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1211621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavelu, N.; Jeyabalan, J.; Veluchamy, A.; Belur, P.D. Production of Tannase from a Newly Isolated Yeast, Geotrichum Cucujoidarum Using Agro-Residues. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 54, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayed, A.; Abdelkareem, S.; Talaat, N.; Dayem, D.A.; Farag, M.A. Tannin in Foods: Classification, Dietary Sources, and Processing Strategies to Minimize Anti-Nutrient Effects. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 9221–9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, J.A.; Coda, R.; Centomani, I.; Summo, C.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Exploitation of the Nutritional and Functional Characteristics of Traditional Italian Legumes: The Potential of Sourdough Fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 196, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Chaparro, S.; Borrás, L.M.; Rache, L.Y.; Brijaldo, M.H.; Martínez, J.J. Solid-State Fermentation as a Biotechnological Tool to Reduce Antinutrients and Increase Nutritional Content in Legumes and Cereals for Animal Feed. Fermentation 2025, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, F.; Aires, A.; Pinto, T.; Oliveira, I.; Vilela, A.; Gonçalves, B. A Comprehensive Review of Bioactive Tannins in Foods and Beverages: Functional Properties, Health Benefits, and Sensory Qualities. Molecules 2025, 30, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorsandi, A.; Shi, D.; Stone, A.K.; Bhagwat, A.; Lu, Y.; Xu, C.; Das, P.P.; Polley, B.; Akhov, L.; Gerein, J.; et al. Effect of Solid-State Fermentation on the Protein Quality and Volatile Profile of Pea and Navy Bean Protein Isolates. Cereal Chem. 2024, 101, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Hajos, G.; Burbano, C.; Pedrosa, M.M.; Ayet, G.; Muzquiz, M.; Pusztai, A.; Gelencser, E. Effect of Natural Fermentation on the Lectin of Lentils Measured by Immunological Methods. Food Agric. Immunol. 2002, 14, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Stone, A.K.; Jafarian, Z.; Liu, E.; Xu, C.; Bhagwat, A.; Lu, Y.; Gao, P.; Polley, B.; Bhowmik, P.; et al. Submerged Fermentation of Lentil Protein Isolate and Its Impact on Protein Functionality, Nutrition, and Volatile Profiles. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 3412–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katrolia, P.; Rajashekhara, E.; Yan, Q.; Jiang, Z. Biotechnological Potential of Microbial α-Galactosidases. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2014, 34, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, M.; Kitamura, M.; Hondoh, H.; Kang, M.S.; Mori, H.; Kimura, A.; Tanaka, I.; Yao, M. Catalytic Mechanism of Retaining α-Galactosidase Belonging to Glycoside Hydrolase Family 97. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 392, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, R.Y.; Li, H.B.; Gunaratne, A.; Sui, Z.Q.; Corke, H. Effects of Fermented Edible Seeds and Their Products on Human Health: Bioactive Components and Bioactivities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 489–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannerchelvan, S.; Rios-Solis, L.; Faizal Wong, F.W.; Zaidan, U.H.; Wasoh, H.; Mohamed, M.S.; Tan, J.S.; Mohamad, R.; Halim, M. Strategies for Improvement of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Biosynthesis via Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Fermentation. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 3929–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ruiz, R.G.; Olivares-Ochoa, X.C.; Salinas-Varela, Y.; Guajardo-Espinoza, D.; Roldán-Flores, L.G.; Rivera-Leon, E.A.; López-Quintero, A. Phenolic Compounds and Anthocyanins in Legumes and Their Impact on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Metabolism: Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolás-García, M.; Jiménez-Martínez, C.; Perucini-Avendaño, M.; Hildeliza Camacho-Díaz, B.; Ruperto Jiménez-Aparicio, A.; Dávila-Ortiz, G. Phenolic Compounds in Legumes: Composition, Processing and Gut Health. In Legumes Research—Volume 2; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz Patto, M.C.; Amarowicz, R.; Aryee, A.N.A.; Boye, J.I.; Chung, H.-J.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.A.; Domoney, C. Achievements and Challenges in Improving the Nutritional Quality of Food Legumes. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2015, 34, 105–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Tabashsum, Z.; Anderson, M.; Truong, A.; Houser, A.K.; Padilla, J.; Akmel, A.; Bhatti, J.; Rahaman, S.O.; Biswas, D. Effectiveness of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Prebiotic-like Components in Common Functional Foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 1908–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.; Verardo, V.; Rizzello, C.G. How Fermentation Affects the Antioxidant Properties of Cereals and Legumes. Foods 2019, 8, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobiuc, A.; Pavăl, N.E.; Mangalagiu, I.I.; Gheorghiță, R.; Teliban, G.C.; Amăriucăi-Mantu, D.; Stoleru, V. Future Antimicrobials: Natural and Functionalized Phenolics. Molecules 2023, 28, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michlmayr, H.; Kneifel, W. β-Glucosidase Activities of Lactic Acid Bacteria: Mechanisms, Impact on Fermented Food and Human Health. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 352, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Galarraga, M.P.; Pirovani, M.E.; García-Cayuela, T.; Van de Velde, F. Fruit and Vegetable Beverages Fermented with Probiotic Strains: Impact on the Content, Bioaccessibility, and Bioavailability of Phenolic Compounds and the Antioxidant Capacity. Curr. Food Sci. Technol. Rep. 2025, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Galarraga, M.P.; Pirovani, M.É.; Vinderola, G.; Van de Velde, F. Bioaccessibility of Phenolic Compounds in Fermented Strawberry-Orange-Apple-Banana Smoothies with Lactobacilli. Food Biosci. 2025, 65, 106074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toor, B.S.; Kaur, A.; Sahota, P.P.; Kaur, J. Antioxidant Potential, Antinutrients, Mineral Composition and FTIR Spectra of Legumes Fermented with Rhizopus oligosporus. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 59, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanowska, K.; Grygier, A.; Kuligowski, M.; Rudzińska, M.; Nowak, J. Effect of Tempe Fermentation by Three Different Strains of Rhizopus oligosporus on Nutritional Characteristics of Faba Beans. LWT 2020, 122, 109024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y.; Sun, J.; Niu, G.; Zuo, F.; Zheng, X. Effects of in Vitro Digestion on Protein Degradation, Phenolic Compound Release, and Bioactivity of Black Bean Tempeh. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1017765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Jiang, B.; Xiong, Y.L.; Zhou, L.; Zhong, F.; Zhang, R.; Bin Tahir, A.; Xiao, Z. Beany Flavor in Pea Protein: Recent Advances in Formation Mechanism, Analytical Techniques and Microbial Fermentation Mitigation Strategies. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, A.; Zhang, H.; Duan, J.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, J.; Zhong, T.; Yu, X. Mechanism and Application of Fermentation to Remove Beany Flavor from Plant-Based Meat Analogs: A Mini Review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1070773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontonio, E.; Raho, S.; Dingeo, C.; Centrone, D.; Carofiglio, V.E.; Rizzello, C.G. Nutritional, Functional, and Technological Characterization of a Novel Gluten- and Lactose-Free Yogurt-Style Snack Produced with Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria and Leguminosae Flours. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.A.N.; Adade, S.Y.S.S.; Ekumah, J.N.; Li, Y.; Betchem, G.; Issaka, E.; Ma, Y. Efficacy of Ultrasound-Assisted Lactic Acid Fermentation and Its Effect on the Nutritional and Sensory Quality of Novel Chickpea-Based Beverage. Fermentation 2023, 9, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Cao, R.; Ren, Y.; Zhao, X. Fermentation of Pea Protein Isolate by Enterococcus Faecalis 07: A Strategy to Enhance Flavor and Functionality. Foods 2025, 14, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, T.; Xu, L.; Yuan, J.; Li, Z.; Yi, C. The Physicochemical Properties and Structure of Mung Bean Starch Fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum. Foods 2024, 13, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia-Olmos, C.; Sánchez-García, J.; Laguna, L.; Zúñiga, E.; Mónika Haros, C.; Maria Andrés, A.; Tarrega, A. Flours from Fermented Lentil and Quinoa Grains as Ingredients with New Techno-Functional Properties. Food Res. Int. 2024, 177, 113915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, M.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S.; Reshetnik, E.I.; Gribanova, S.L.; Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Liu, L.; Zhao, L. Physicochemical Properties and Volatile Components of Pea Flour Fermented by Lactobacillus rhamnosus L08. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorsandi, A.; Stone, A.K.; Shi, D.; Xu, C.; Das, P.P.; Lu, Y.; Rajagopalan, N.; Tanaka, T.; Korber, D.R.; Nickerson, M.T. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Fermented Pea and Navy Bean Protein Isolates. Cereal Chem. 2024, 101, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Omedi, J.O.; Zheng, J.; Huang, W.; Jia, C.; Zhou, L.; Zou, Q.; Li, N.; Gao, T. Exopolysaccharides in Sourdough Fermented by Weissella confusa QS813 Protected Protein Matrix and Quality of Frozen Gluten-Red Bean Dough during Freeze-Thaw Cycles. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Li, Y.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y.; Quan, K. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum Fermentation on the Volatile Flavors of Mung Beans. LWT 2021, 146, 111434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, N.; Henriksen, M.G.; Crocoll, C.; Li, Q.; Lametsch, R.; Poojary, M.M.; Krych, L.; Petersen, M.A.; Jespersen, L. Enhancing the Sensory and Nutritional Properties of Faba Bean Protein through 2 Fermentation with Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bacillus spp. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 446, 111549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Van de Velde, F.; Cian, R.E.; Garzón, A.G.; Albarracín, M.; Drago, S.R. Fermented Pulses for the Future: Microbial Strategies Enhancing Nutritional Quality, Functionality, and Health Potential. Fermentation 2026, 12, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010018

Van de Velde F, Cian RE, Garzón AG, Albarracín M, Drago SR. Fermented Pulses for the Future: Microbial Strategies Enhancing Nutritional Quality, Functionality, and Health Potential. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan de Velde, Franco, Raúl E. Cian, Antonela G. Garzón, Micaela Albarracín, and Silvina R. Drago. 2026. "Fermented Pulses for the Future: Microbial Strategies Enhancing Nutritional Quality, Functionality, and Health Potential" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010018

APA StyleVan de Velde, F., Cian, R. E., Garzón, A. G., Albarracín, M., & Drago, S. R. (2026). Fermented Pulses for the Future: Microbial Strategies Enhancing Nutritional Quality, Functionality, and Health Potential. Fermentation, 12(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010018